Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Recovery of E. coli and enterococci from cloacal samples of pelicans in non-supplemented media

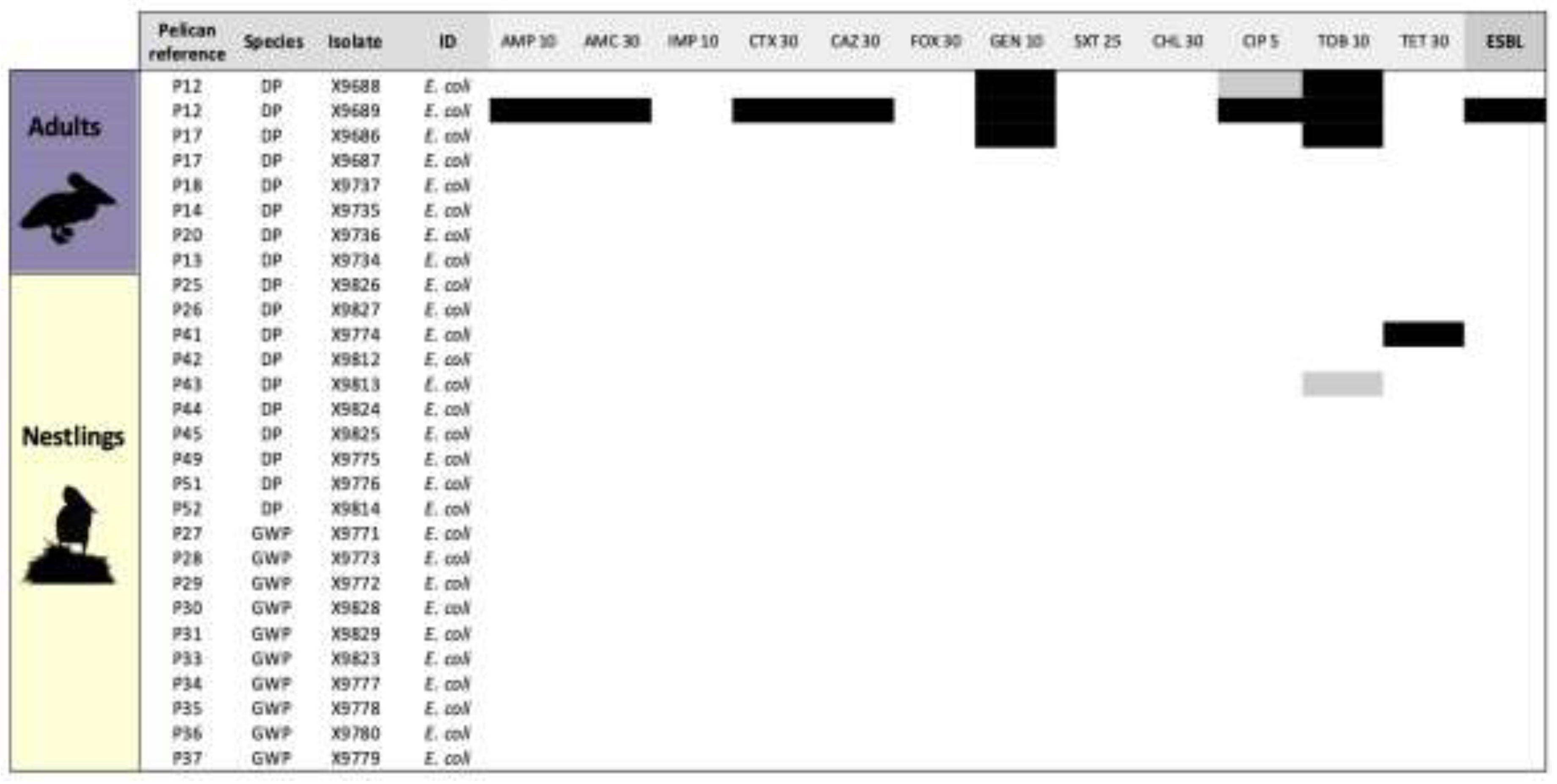

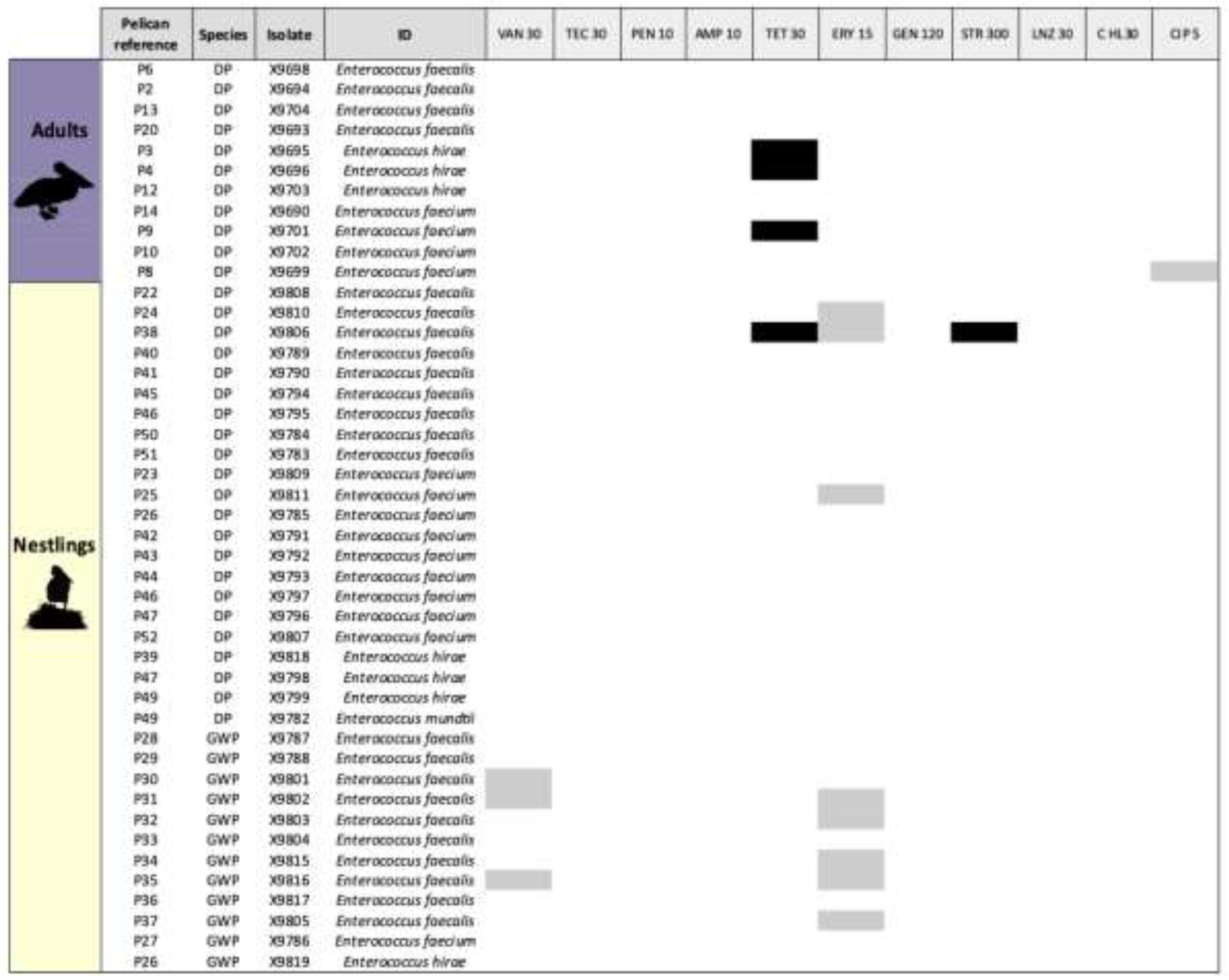

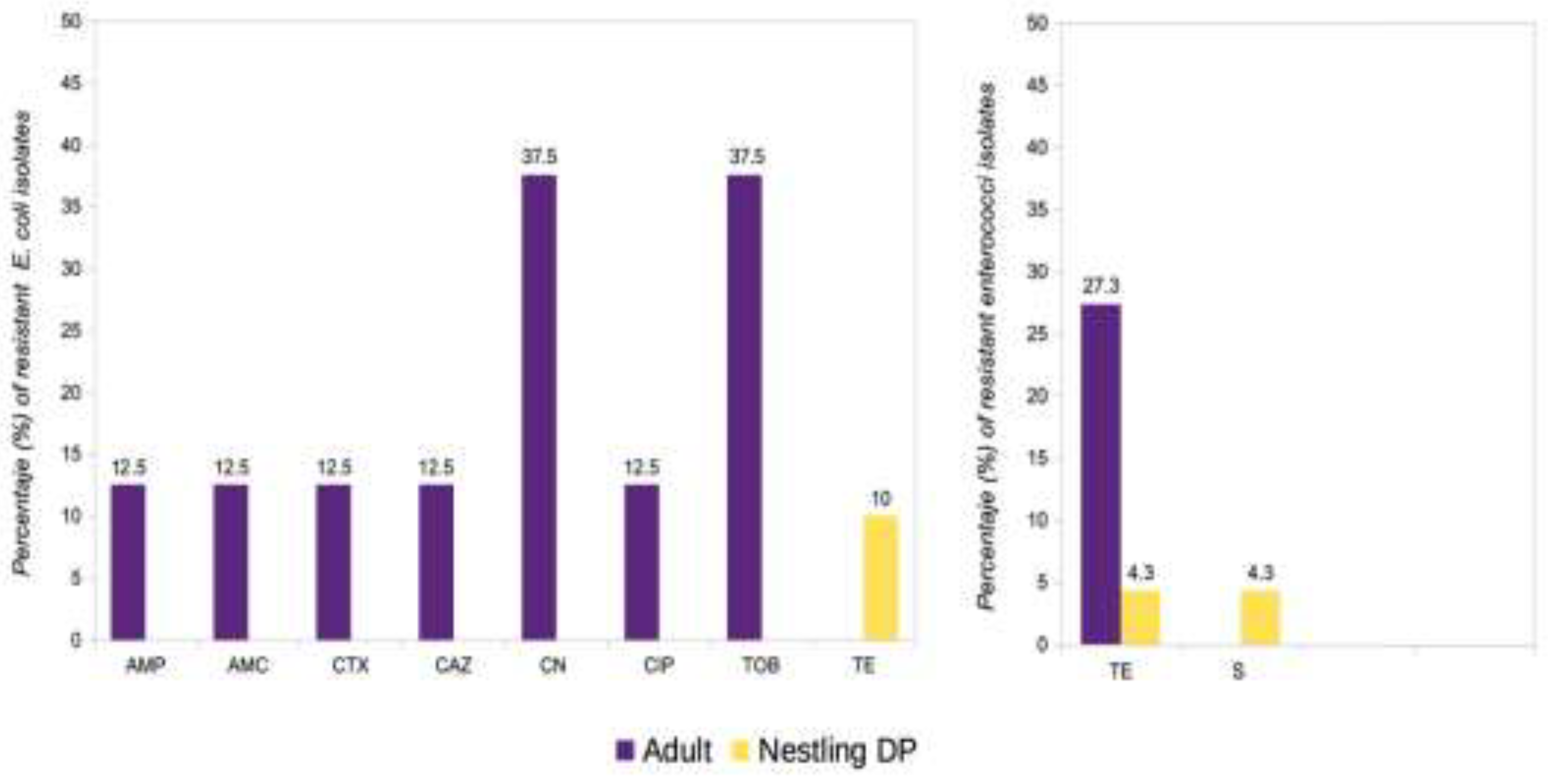

2.2. Phenotypes and genotypes Of Non-Repetitive E. coli and Enterococci Isolates Recovered In Non-Supplemented Media

2.3. Prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli (ESBL-Ec)

2.4. Sexing

2.5. Differences Between Sex, Age Groups and Species

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

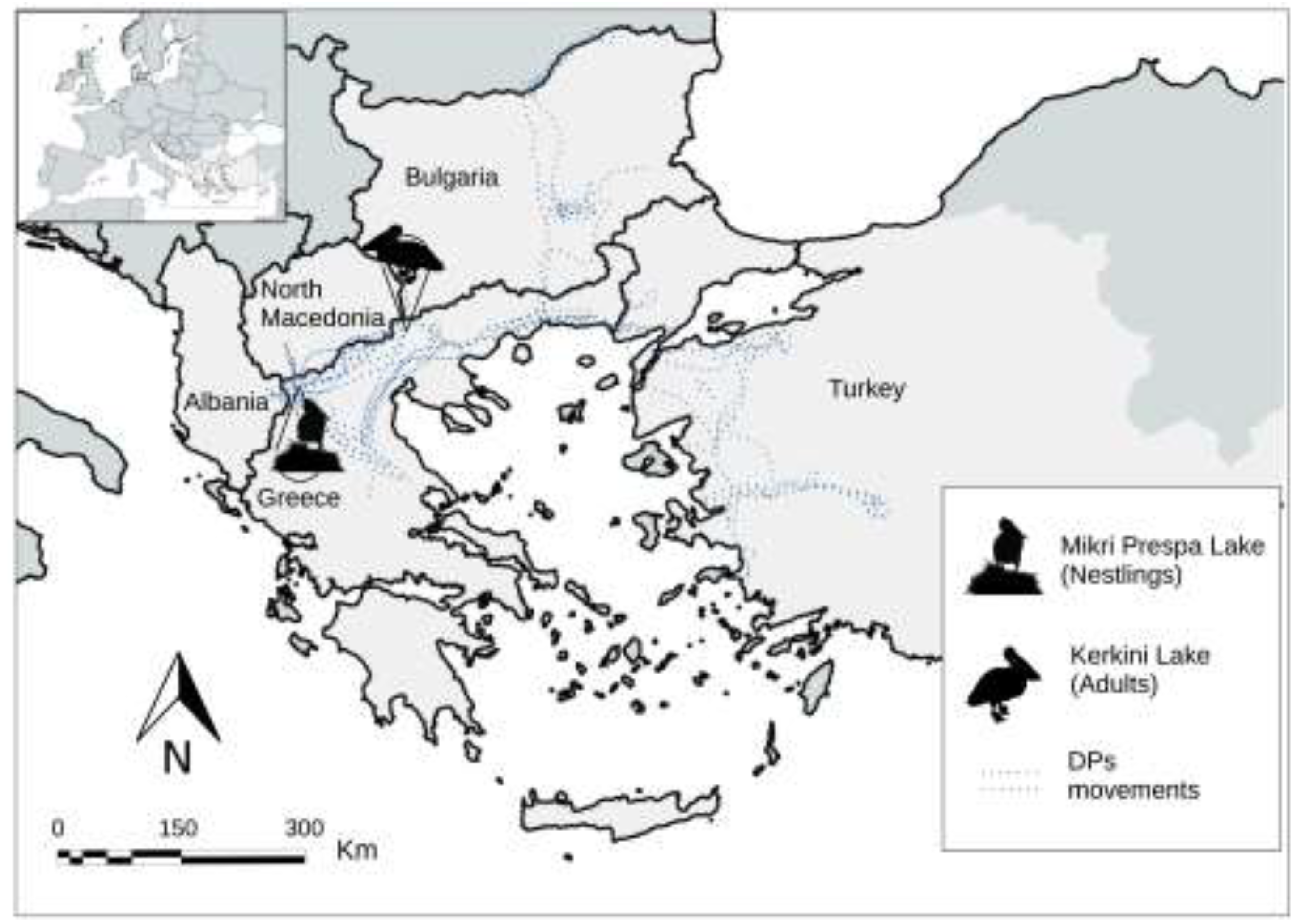

4.1. Study Sites

4.2. Sampling

4.3. Bacterial Isolation And Identification

4.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.5. E. coli and Enterococci DNA Extraction

4.6. Molecular Characterization Of Antibiotic-Resistant Genes

4.7. Sex Determination

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crivelli, A.J.; Vizi, O. The Dalmatian pelican Pelecanus crispus Bruch 1832, a recently world-endangered bird species. Biol. Conserv. 1981, 20, 297–310. [CrossRef]

- Catsadorakis, G.; Portolou, D. International single species action plan for the conservation of the Dalmatian Pelican (Pelecanus crispus). CMS Technical Series No. 39, AEWA Technical Series No. 69. EAAFP Technical Report No. 1. Bonn, Germany and Incheon, South Korea. 2018.

- Del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. Handbook of the Birds of the World; Lynx Editions: Barcelona, Spain, 1992; Volume 1, pp. 290-311.

- Catsadorakis, G.; Onmuş, O.; Bugariu, S.; Gül, O.; Hatzilacou, D.; Hatzofe, O.; Malakou, M.; Michev, T.; Naziridis, T.; Nikolaou, H.; Rudenko, A.; Saveljic, D.; Shumka, S.; Siki, M.; Crivelli, A.J. Current status of the Dalmatian pelican and the great white pelican populations of the Black Sea-Mediterranean flyway. Endanger Species Res. 2015, 27, 119–130. [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, E.; Alexandrou, O.; Manolopoulos, A.; Xirouchakis, S.; Catsadorakis, G. Home range of the Dalmatian pelican in south-east Europe. Eur J Wildl Res 2023, 69. [CrossRef]

- Crivelli, AJ.; Catsadorakis, G.; Hatzilacou, D.; Hulea, D.; Malakou, M.; Marinov, M.; Michev, T.; Nazirides, T.; Peja, N.; Sarigul, G.; Sıkı, M. Status and population development of Great white and Dalmatian pelicans, Pelecanus onocrotalus and P. crispus breeding in the Palearctic. 5th Medmaravis Pan-Mediterranean Seabird Symposium ‘Monitoring and conservation of birds, mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas’, Gozo, Malta, 2000; pp 38–45.

- Catsadorakis, G.; Crivelli, A.J. Nesting Habitat Characteristics and Breeding Performance of Dalmatian Pelicans in Lake Mikri Prespa, NW Greece. Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 2001, 24, 386-393. [CrossRef]

- Crivelli, A.J.; Hatzilacou, D.; Catsadorakis, G. The breeding biology of Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus. Ibis 1998, 140, 472-481. [CrossRef]

- BirdLife International. Pelecanus onocrotalus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T22697590A177120498. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22697590A177120498.en (Accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Crivelli, A.J.; Leshem, Y.; Mitchev, T.; Jerrentrup, H. Where do Palaearctic great white pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus) presently overwinter?. Revue d’Ecologie,Terre et Vie 1991, 46, 145-171. [CrossRef]

- Catsadorakis, G. An update of the two Pelecanus species in the Mediterranean–Black Sea region. In: Conservation of marine and coastal birds in the Mediterranean. Proc. UNEP-MAPRAC/SPA Symposium, Hamammet, Tunisia, 20 to 22 February 2015; Yésou, P.; Sultana, J.; Walmsley J.; Azafzaf, H. (Eds), 2016, pp. 47–52.

- Izhaki, I.; Shmueli, M.; Arad, Z.; Steinberg, Y.; Crivelli, A.J. Satellite tracking of migratory and ranging behaviour of inmature Great white pelicans. Waterbirds 2002, 25, 295-304. [CrossRef]

- Alexandrou, O.; Malakou, M.; Catsadorakis, G. The impact of avian influenza 2022 on Dalmatian pelicans was the worst ever wildlife disaster in Greece. Oryx 2022, 56, 813-813. [CrossRef]

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: bacterial pathogens of public health importance to guide research, development and strategies to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376776/9789240093461-eng.pdf (Accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Höfle, U.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J.; Camacho, M.C.; Solà-Ginés, M.; Moreno-Mingorance, A.; Manuel Hernández, J.; De La Puente, J.; Pineda-Pampliega, J.; Aguirre J.I.; Torres-Medina, F.; Ramis, A.; Majó, N.; Blas, J.; Migura-García, L. Foraging at Solid Urban Waste Disposal Sites as Risk Factor for Cephalosporin and Colistin Resistant Escherichia coli Carriage in White Storks (Ciconia ciconia). Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 1397. [CrossRef]

- Akhil Prakash, E.; Hromádková, T.; Jabir, T.; Vipindas, P.V.; Krishnan, K.P.; Mohamed Hatha, A.A.; Briedis, M. Dissemination of multidrug resistant bacteria to the polar environment - Role of the longest migratory bird Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea). Sci Total Environ 2022, 815, 152727. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvarez, S.; Châtre, P.; Cardona-Cabrera, T.; François, P.; Sánchez-Cano, A.; Höfle, U.; Zarazaga, M.; Madec, J-Y.; Haenni, M.; Torres, C. Detection and genetic characterization of blaESBL-carrying plasmids of cloacal Escherichia coli isolates from white stork nestlings (Ciconia ciconia) in Spain. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2023, 34, 186-194. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Yana, T.; Salgado-Caxito, M.; Hayer, J.; Rojas-Sereno, Z.E.; Pino-Hurtado, M.S.; Campaña-Burguet, A.; Caparrós, C.; Torres, C.; Benavides, J.A. ESBL-producing Escherichia coli prevalence and sharing across seabirds of central Chile. Sci Total Environ 2024, 951, 175475. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Castillo, D.; Farfán-López, M.; Esposito, F.; Moura, Q; Fernandes, M.R.; Lopes, R.; Cardoso, B.; Muñoz, M.E.; Cerdeira, L.; Najle, I.; Muñoz, P.M.; Catão-Dias, J.L.; González-Acuña, D.; Lincopan, N. Wild owls colonized by international clones of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (CTX-M)-producing Escherichia coli and Salmonella Infantis in the Southern Cone of America. Sci Total Environ 2019, 674, 554-562. [CrossRef]

- Athanasakopoulou, Z.; Diezel, C.; Braun, S.D.; Sofia, M.; Giannakopoulos, A.; Monecke, S.; Gary, D.; Krähmer, D.; Chatzopoulos, D.C.; Touloudi, A.; et al. Occurrence and Characteristics of ESBL- and Carbapenemase- Producing Escherichia coli from Wild and Feral Birds in Greece. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1217. [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, C.A.; van Toor, M.L.; Woksepp, H.; Chandler, J.C.; Reed, J.A.; Reeves, A.B.; Waldenström, J.; Franklin, A.B.; Douglas, D.C.; Bonnedahl, J.; Ramey, A.M. Evidence for continental-scale dispersal of antimicrobial resistant bacteria by landfill foraging gulls. Sci Total Environ 2021, 764, 144551. [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, C.A.; Woksepp, H.; Sandegren, L.; Mohsin, M.; Hasan, B.; Muzyka, D.; Hernandez, J.; Aguirre, F.; Tok, A.; Söderman, J.; Olsen, B.; Ramey, A.M.; Bonnedahl, J. Genomically diverse carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae from wild birds provide insight into global patterns of spatiotemporal dissemination. Sci Total Environ 2022, 824, 153632. [CrossRef]

- Jarma, D.; Sánchez, M.I.; Green, A.J.; Peralta-Sánchez, J.M.; Hortas, F.; Sánchez-Melsió, A.; Borrego, C.M. Faecal microbiota and antibiotic resistance genes in migratory waterbirds with contrasting habitat use. Sci Total Environ 2021, 783, 146872. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvarez, S.; Höfle, U.; Châtre, P.; Alonso, C. A.; Asencio-Egea, M. A.; François, P.; Cardona-Cabrera, T.; Zarazaga, M.; Madec, J.; Haenni, M.; Torres, C. One Health bottom-up analysis of the dissemination pathways concerning critical priority carbapenemase- and ESBL-producing Enterobacterales from storks and beyond. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Efrat, R.; Harel, R.; Alexandrou, O.; Catsadorakis, G.; Nathan, R. Seasonal differences in energy expenditure, flight characteristics and spatial utilization of Dalmatian pelicans Pelecanus crispus in Greece. Ibis 2018, 161, 415–427. [CrossRef]

- Peirano, G.; Pitout, J.D.D. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae: Update on Molecular Epidemiology and Treatment Options. Drugs 2019, 79, 1529–1541. [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak, K.M.; de Jonge, B.L.M.; Stone, G.G.; Sahm, D.F. Longitudinal analysis of ESBL and carbapenemase carriage among Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates collected in Europe as part of the International Network for Optimal Resistance Monitoring (INFORM) global surveillance programme, 2013-17. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020, 75, 1165–1173.

- Riley L.W. (2014). Pandemic lineages of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014, 20, 380–390. [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, B.; Gulyás, D.; Szabó, D. Emergence and Dissemination of Extraintestinal Pathogenic High-Risk International Clones of Escherichia coli. Life 2022, 12, 2077. [CrossRef]

- Day, M.J.; Rodríguez, I.; van Essen-Zandbergen, A.; Dierikx, C.; Kadlec, K.; Schink, A.K.; Wu, G.; Chattaway, M.A.; DoNascimento, V.; Wain, J.; Helmuth, R.; Guerra, B.; Schwarz, S.; Threlfall, J.; Woodward, M.J.; Coldham, N.; Mevius, D.; Woodford, N. Diversity of STs, plasmids and ESBL genes among Escherichia coli from humans, animals and food in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016, 71, 1178–1182. [CrossRef]

- Grönthal, T.; Österblad, M.; Eklund, M.; Jalava, J.; Nykäsenoja, S.; Pekkanen, K.; Rantala, M. Sharing more than friendship - transmission of NDM-5 ST167 and CTX-M-9 ST69 Escherichia coli between dogs and humans in a family, Finland, 2015. Euro Surveill 2018, 23, 1700497. [CrossRef]

- Jamborova, I.; Dolejska, M.; Vojtech, J.; Guenther, S.; Uricariu, R.; Drozdowska, J.; Papousek, I.; Pasekova, K.; Meissner, W.; Hordowski, J.; Cizek, A.; Literak, I. Plasmid-mediated resistance to cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones in various Escherichia coli sequence types isolated from rooks wintering in Europe. Appl Environ Microb 2015, 81, 648–657. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Antimicrobial consumption in the EU/EEA (ESAC-Net) - Annual Epidemiological Report 2022. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER-antimicrobial-consumption.pdf (Accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Kopsidas, I.; Theodosiadis, D.; Triantafyllou, C.; Koupidis, S.; Fanou, A.; Hatzianastasiou S. EVIPNet evidence brief for policy: preventing antimicrobial resistance and promoting appropriate antimicrobial use in inpatient health care in Greece. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/361842/WHO-EURO-2022-5837-45602-65411-eng.pdf (Accessed on 8 July 2024).

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control), 2024. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2021/2022. EFSA J 2024, 22, e8583. [CrossRef]

- Marti, E.; Variatza, E.; Balcazar, J.L. The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol 2014, 22, 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Nnadozie, C.F.; Odume, O.N. Freshwater environments as reservoirs of antibiotic resistant bacteria and their role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Environ Pollut 2019, 254(Pt B), 113067. [CrossRef]

- Samreen; Ahmad, I.; Malak, H.A.; Abulreesh, H.H. Environmental antimicrobial resistance and its drivers: a potential threat to public health. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2021, 27, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Pepi, M.; Focardi, S. Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Aquaculture and Climate Change: A Challenge for Health in the Mediterranean Area. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 5723. [CrossRef]

- Nikolakopoulou, T.L.; Giannoutsou, E.P.; Karabatsou, A.A.; Karagouni, A.D. Prevalence of tetracycline resistance genes in Greek seawater habitats. J Microbiol 2008, 46, 633–640. [CrossRef]

- Kalantzi, I.; Rico, A.; Mylona, K.; Pergantis, S.A.; Tsapakis, M. Fish farming, metals and antibiotics in the eastern Mediterranean Sea: Is there a threat to sediment wildlife?. Sci total environ 2021, 764, 142843. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, D. A.; Parlapani, F.F.; Natoudi, S.; Syropoulou, F.; Kyritsi, M.; Vergos, I.; Hadjichristodoulou, C.; Kagalou, I.; Boziaris, I.S. Bacterial Communities and Antibiotic Resistance of Potential Pathogens Involved in Food Safety and Public Health in Fish and Water of Lake Karla, Thessaly, Greece. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1473. [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2024. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 – Blue Transformation in action. Rome. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd0683en (Accessed on 10 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lulijwa, R.; Rupia, Emmanuel.; Alfaro, Andrea. Antibiotic use in aquaculture, policies and regulation, health and environmental risks: a review of the top 15 major producers. Rev Aquac 2019, 12, 10.1111/raq.12344. [CrossRef]

- Preena, P.G.; Swaminathan, T.R.; Kumar, V.J.R.; Singh, I.S.B. (2020) Antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: a crisis for concern. Biologia 2020,75, 1497–1517. [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H.; Younas, S.; Abosalif, K.O.A.; Junaid, K.; Alzahrani, B.; Alsrhani, A.; Abdalla, A.E.; Ullah, M.I.; Qamar, M.U.; Hamam, S.S.M. Molecular analysis of blaSHV, blaTEM, and blaCTX-M in extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae recovered from fecal specimens of animals. PloS One 2021, 16, e0245126. [CrossRef]

- Athanasakopoulou, Z.; Reinicke, M.; Diezel, C.; Sofia, M.; Chatzopoulos, D.C.; Braun, S.D.; Reissig, A.; Spyrou, V.; Monecke, S.; Ehricht, R.; Tsilipounidaki, K.; Giannakopoulos, A.; Petinaki, E.; Billinis, C. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates from Animals in Greece. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 389. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, Z. B.; Zeng, Z.L.; Yang, X.W.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.H. The role of wildlife (wild birds) in the global transmission of antimicrobial resistance genes. Zool Res 2017, 38, 55–80. [CrossRef]

- Bounas, A.; Catsadorakis, G.; Naziridis, T.; Bino, T.; Hatzilacou, D.; Malakou, M.; Onmus, O.; Siki, M.; Simeonov, P.; Crivelli, A. J. Site fidelity and determinants of wintering decisions in the Dalmatian pelican (Pelecanus crispus). Ethol Ecol Evol 2022, 35, 434–448. [CrossRef]

- Sandegren, L.; Stedt, J.; Lustig, U.; Bonnedahl, J.; Andersson, D.I.; Järhult, J.D. Long-term carriage and rapid transmission of extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing E. coli within a flock of Mallards in the absence of antibiotic selection. Environ Microbiol Rep 2018, 10, 576-582. [CrossRef]

- Veldman, K.; van Tulden, P.; Kant, A.; Testerink, J.; Mevius, D. Characteristics of Cefotaxime-Resistant Escherichia coli from Wild Birds in The Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79, 7556–7561. [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, L.; Alonso, C.A.; Simón, C.; González-Esteban, C.; Orós, J.; Rezusta, A.; Ortega, C.; Torres, C. Wild Birds, Frequent Carriers of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) Producing Escherichia coli of CTX-M and SHV-12 Types. Microb Ecol 2016, 72, 861-869. [CrossRef]

- Prandi, I.; Bellato, A.; Nebbia, P.; Stella, M.C.; Ala, U.; von Degerfeld, M.M.; Quaranta, G.; Robino, P. Antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli in wild birds hospitalised in a wildlife rescue centre. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2023, 93, 101945. [CrossRef]

- Aires-de-Sousa, M.; Fournier, C.; Lopes, E.; de Lencastre, H.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. High Colonization Rate and Heterogeneity of ESBL- and Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Gull Feces in Lisbon, Portugal. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1487. [CrossRef]

- Vergara, A.; Pitart, C.; Montalvo, T.; Roca, I.; Sabaté, S.; Hurtado, J.C.; Planell, R.; Marco, F.; Ramírez, B.; Peracho, V.; de Simón, M.; Vila, J. Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase- and/or Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli Isolated from Yellow-Legged Gulls from Barcelona, Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61, 10.1128/aac.02071-16. [CrossRef]

- Dotto, G.; Menandro, M.L.; Mondin, A.; Martini, M.; Tonellato, F.R.; Pasotto, D. Wild Birds as Carriers of Antimicrobial-Resistant and ESBL-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Infect Dis 2016, 53, 59. [CrossRef]

- Oteo, J.; Mencía, A.; Bautista, V.; Pastor, N.; Lara, N.; González-González, F.; García-Peña, F.J.; Campos, J. Colonization with Enterobacteriaceae-Producing ESBLs, AmpCs, and OXA-48 in Wild Avian Species, Spain 2015-2016. Microb Drug Resist 2018, 24, 932–938. [CrossRef]

- Jarma, D.; Sánchez, M.I.; Green, A.J.; Peralta-Sánchez, J.M.; Hortas, F.; Sánchez-Melsió, A.; Borrego, C.M. Faecal microbiota and antibiotic resistance genes in migratory waterbirds with contrasting habitat use. Sci Total Environ 2021, 783, 146872. [CrossRef]

- Catsadorakis, G.; Alexandrou, O.; Hatzilacou, D.; Kasvikis, I.; Katsikatsou, M.; Konstas, S.; Malakou, M.; Michalakis, D.; Naziridis, Th.; Nikolaou, H.; Noulas, N.; Portolou, D.; Roussopoulos, Y.; Vergos, I.; Crivelli, A.J. Breeding colonies, population growth and breeding success of the Dalmatian pelican (Pelecanus crispus) in Greece: a country-wide perspective, 1967-2021. Eur J Ecol 2024, 10, 63-86. [CrossRef]

- Handrinos, G.; Catsadorakis, G. The historical and current distribution of Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus and Great White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus in Greece and adjacent areas: 1830-2019. Avocetta 2020, 44, 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 32nd ed. CLSI Supplement M100-Ed32. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, USA, 2022.

- Fridolfsson, A.K.; Ellegren, H. A simple and universal method for molecular sexing of non-ratite birds. J Avian Biol 1999, 30, 116–121. [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L.; Dell’Amico, E.; Migliavacca, R.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Giacobone, E.; Amicosante, G.; Romero, E.; Rossolini, G.M. Multiple CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases innosocomial isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from a hospital in Northern Italy. J Clin Microbiol 2003, 41, 4264–4269. [CrossRef]

- Coque, T.M.; Oliver, A.; Pérez-Díaz, J.C.; Baquero, F.; Cantón, R. Genes encoding TEM-4, SHV-2, and CTX-M-10 extended-spectrum β-lactamases are carried by multiple Klebsiella pneumoniae clones in a single hospital (Madrid, 1989 to 2000). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002, 46, 500–510. [CrossRef]

- Pitout, J.D.D.; Thomson, K.S.; Hanson, N.D.; Ehrhardt, A.F.; Moland, E.S.; Sanders, C.C. β-lactamases responsible for resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporinsin Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis isolates recovered in South Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998, 42, 1350–1354. [CrossRef]

- Belaaouaj, A.; Lapoumeroulie, C.; Caniça, M.M.; Vedel, G.; Névot, P.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Paul, G. Nucleotide sequences of the genes coding for the TEM-like β-lactamases IRT-1 and IRT-2 (formerly called TRI-1 and TRI-2). FEMS Microbiol Lett 1994, 120, 75-80. [CrossRef]

- Steward, C.D.; Rasheed, J.K.; Hubert, S.K.; Biddle, J.W.; Raney, P.M.; Anderson, G.J.; Williams, P.P.; Brittain, K.L.; Oliver, A.; McGowan, J.E.Jr.; Tenover, F.C. Characterization of clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from 19 laboratories using the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards extended-spectrum beta-lactamase detection methods. J Clin Microbiol 2001, 39, 2864–2872. [CrossRef]

- Guardabassi, L.; Dijkshoorn, L.; Collard, J.M.; Olsen, J.E.; Dalsgaard, A. Distribution and in-vitro transfer of tetracycline resistance determinants in clinical and aquatic Acinetobacter strains. J Med Microbiol 2000, 49, 929–936. [CrossRef]

- Aarestrup, F.M.; AgersŁ, Y.; Ahrens, P.; JŁrgensen, J.C.; Madsen, M.; Jensen, L.B. Antimicrobial susceptibility and presence of resistance genes in staphylococci from poultry. Vet Microbiol 2000, 74, 353–364. [CrossRef]

- Schnellmann, C.; Gerber, V.; Rossano, A.; Jaquier, V.; Panchaud, Y.; Doherr, M.G.; Thomann, A.; Straub, R.; Perreten, V. Presence of new mecA and mph(C) variants conferring antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus spp. isolated from the skin of horses before and after clinic admission. J Clin Microbiol 2006,44, 4444–4454. [CrossRef]

- Tartof, S.Y.; Solberg, O.D.; Manges, A.R.; Riley, L.W. Analysis of a uropathogenic Escherichia coli clonal group by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 5860–5864. [CrossRef]

| Isolate | Number/Percentage of positive samples (n.º of non-repetitive isolates1) | |||

| Adults n=21 |

Nestlings n=31 |

Nestling DP n=20 |

Nestling GWP n=11 |

|

| Escherichia coli | 6/28.6 (8) | 20/64.5 (20) | 10/50 (10) | 10/90.9 (10)* |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 4/19 (4) | 19/61.3 (19)* | 9/45 (9) | 10/90.9 (10)* |

| Enterococcus faecium | 4/19 (4) | 10/32.2 (10) | 9/45 (9)* | 1/9.1 (1) |

| Enterococcus hirae | 3/14.3 (3) | 4/12.9 (4) | 4/20 (4) | - |

| Enterococcus mundtii | - | 1/ 3.2 (1) | 1/5 (1) | - |

| Total Enterococcus | 11/52.4 (11) | 30/96.8 (34) | 19/95 (23) | 11/100 (11) |

| Total non-repetitive isolates | 19 | 54 | 33 | 21 |

| Isolate | ID | Pelican reference | Age group |

Species | Resistance phenotype | Resistance genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X9689 | E. coli | P12 | A | DP | CTX-AMC-CAZ-GEN-AMP-CIP-TOB | blaCTX-M15 |

| X9688 | E. coli | P12 | A | DP | GEN-TOB | |

| X9686 | E. coli | P17 | A | DP | GEN-TOB | |

| X9774 | E. coli | P41 | N | DP | TET | tet(A) |

| X9695 | E. hirae | P3 | A | DP | TET | tet(M) |

| X9696 | E. hirae | P4 | A | DP | TET | tet(M), tet(L) |

| X9701 | E. faecium | P9 | A | DP | TET | tet(M), tet(L) |

| X9806 | E. faecalis | P38 | N | DP | STR-TET | tet(M) |

| E. coli isolate | Pelican reference | Resistance phenotype | ESBL resistance genes | ST |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X9682 | P11 | CTX-AMC-CAZ-GEN-AMP-CIP-TOB | CTX-M15 | 69 |

| X9684* | P12 | CTX-AMC-CAZ-GEN-AMP-CIP-TOB | CTX-M15 | 69 |

| X9706 | P15 | CTX-AMC-CAZ-GEN-AMP-SXT-CIP-TOB | CTX-M15 | 69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).