Introduction

Heterocycles are organic compounds that consist of at least one atom other than C within a cyclic framework. Most commonly encountered heterocycles usually possess one heteroatom such as O, N, and S within five- or six-membered rings. The substitution of a heteroatom in lieu of C dramatically alters the physico-chemical properties of the heterocycle compared to it’s corresponding carbocyclic analog. Therefore, it is not surprising that heterocycle-based compounds play a pivotal role in biological processes [

1]. They are often implicated in regulating many biological functions in nature. For instance, many heterocycles are biosynthesized by plants and animals, including: chlorophylls, the green pigments found in plants and algae that capture light energy essential for photosynthesis; heme, the iron containing prosthetic group found at the center of hemoglobin that enables the protein to bind and transport oxygen in the blood; purines and pyrimidines, the nitrogenous bases that serve as building blocks for RNA and DNA, etc. Furthermore, several essential amino acids, which are crucial for the biosynthesis of proteins and enzymes, are also known to have heterocyclic cores (e.g., proline, histidine, and tryptophan) [

1]. Some microorganisms and plants biosynthesize heterocyclic framework based secondary metabolites as their defense chemicals [

2,

3]. Given the biological importance of heterocycles, these heterocyclic scaffolds are being increasingly used in the development biologically active molecules for their application as agrochemicals, pharmaceuticals and medicinal agents [

4].

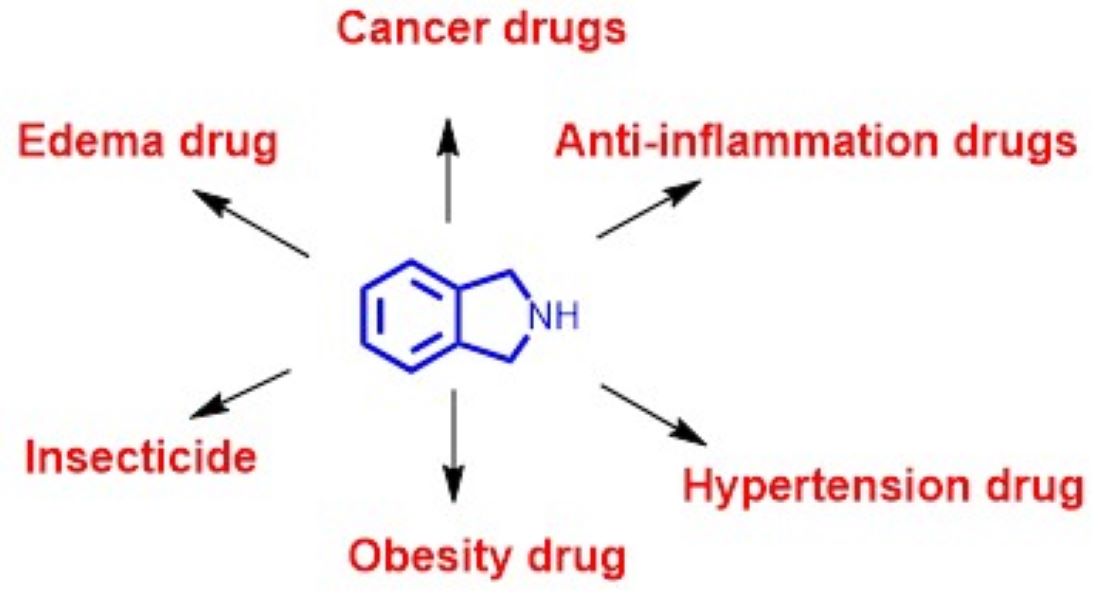

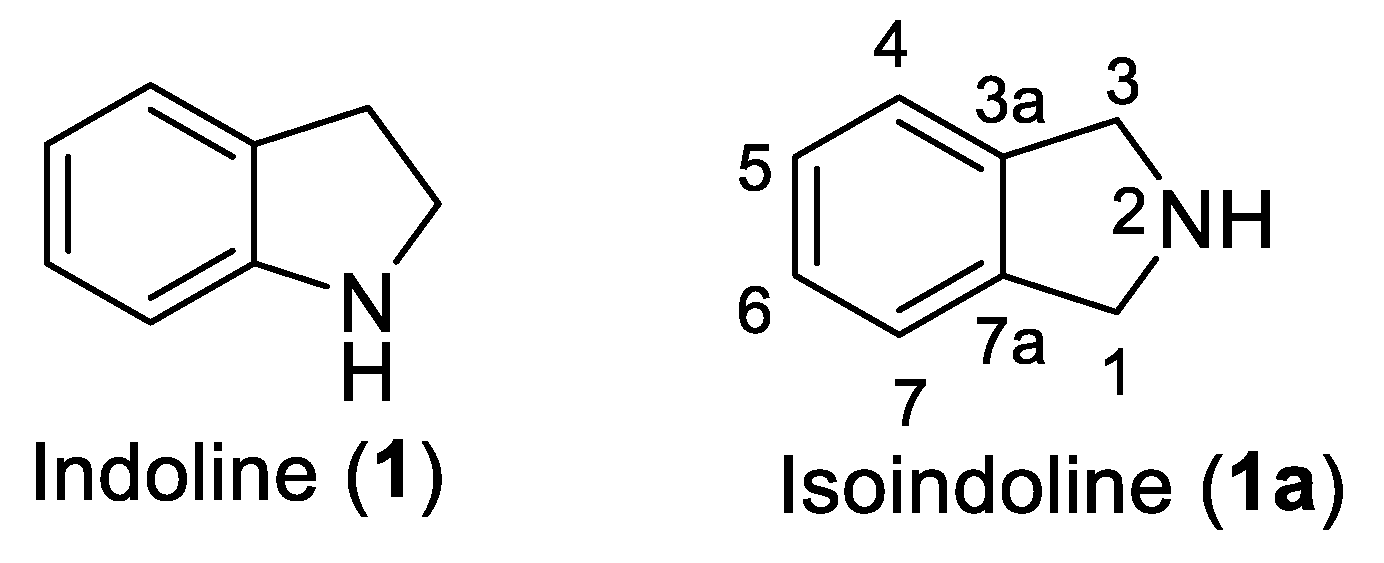

Among numerous heterocycles, indoline (

1) and its isomer isoindoline (

1a) are bicyclic frameworks in which a benzene ring is fused with a 5 membered nitrogenous pyrrolidine ring (

Figure 1). Both these rings are regarded as privileged structures because their derivatives display diverse medicinal and biological activities [

5,

6]. Out of the two heterocycles,

1a is the subject of focus in this review. Although, unsubstituted isolidoline (

1a) is rarely encountered, substituted isoindolines have garnered special attention from scientists because of their presence in numerous natural and pharmaceutical compounds [

7]. A remarkable range of biological activities including, selective serotonin uptake inhibition, antitumor, diuretic, cytotoxic, hypertensive, herbicidal, mental disorder treatment agents, bronchodilators,

N-methyl-D-aspartate agonists, multidrug resistance reversal agents, and fibrinogen receptor antagonists have been reported from isoindoline derivatives [

7,

8]. The most notable and probably most controversial member among these is infamous thalidomide of teratogenic fame [

9].

We have a long-standing interest in isoindoline-based heterocycles. Our group is actively working towards the development of efficient synthesis of novel molecules possessing isoindoline heterocyclic core

1a. We have recently reported synthesis of 5-arylisoindolo [2,1-

a]quinolin-11(6a

H)-ones [

10],

2-(2-substitued-aryl)-3-(2-(2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl)vinyl)isoindolin-1-ones [

11]

, 6,6a-dihydroisoindolo[2,1-

a]quinolin-11(5

H)-ones [

12], and substituted-(2-oxo)-2-arylisoindolin-1-ones [

13].

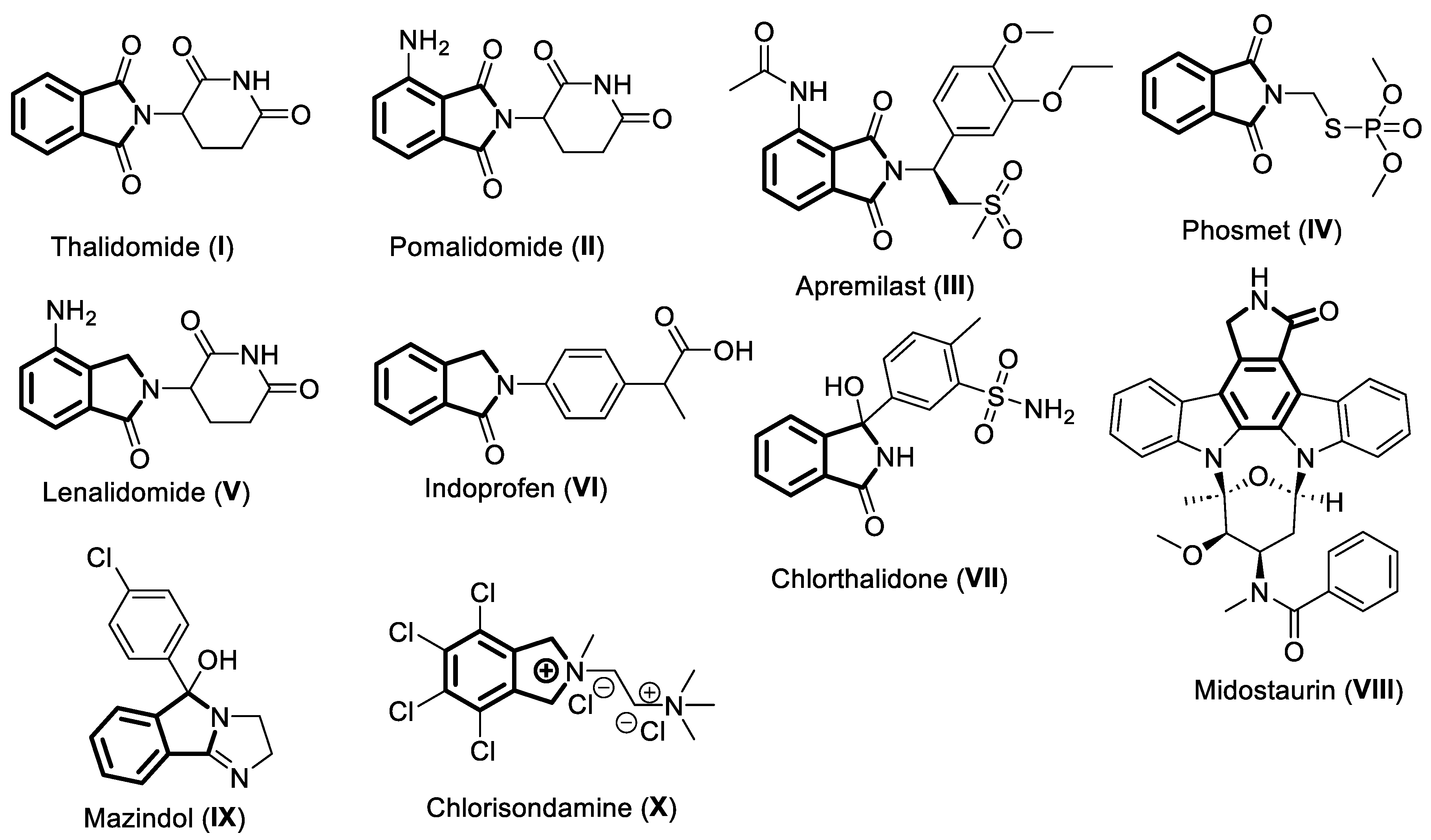

Currently, there are ten approved drugs that contain isoindoline heterocyclic core

1a in their chemical structure (

Figure 2),

viz. thalidomide (

I), pomalidomide (

II), apremilast (

III), phosmet (

IV), lenalidomide (

V), indoprofen (

VI), chlorthalidone (

VII), midostaurin (

VIII) mazindol, (

IX), and chlorisondamine (

X). This review focuses on highlighting the pharmacological properties of these isoindoline-based drugs and their mode of actions. The currently known chemical synthesis to access these valuable molecules is also presented here. This review is organized based of the oxygenation levels of the isoindoline core

1a. The drugs having di-oxygenated isoindoline heterocycle

I-IV are discussed first, followed by the mono-oxygenated

V-1X ones, and lastly the non-oxygenated molecule

X is described.

1. Thalidomide

Thalidomide (

I) is one of the earliest known drugs containing an isoindoline core

1a. The positions 1 and 3 of isoindoline ring

1a (

Figure 1) are oxidized. The resulting skeleton is referred to as isoindoline-1,3-dione or phthalimide ring. The N of the phthalimide ring is functionalized with a piperidine-dione moiety in

I (

Figure 2). This drug is indicated for the treatment of multiple myeloma and erythema nodosum leprosum.

Thalidomide (

I) drug was originally developed as a non-barbiturate sedative for the treatment of morning sickness in pregnant women in late 1950’s [

14]. It was prescribed widely in Europe, Australia, and Japan. Later, it was later found that thalidomide (

I) is a teratogen as it causes irreversible damage to the fetus. Thousands of children were born with severe congenital malformations [

9]. Following this tragedy, thalidomide (

I) was withdrawn from the market in the early 1960’s. Fortunately, the thalidomide tragedy was averted in the United States because of the hold on its approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Although, the teratogenic effects were yet to be attributed to thalidomide (

I), the decision of the FDA to put the approval on hold was based on concerns over peripheral neuropathy in the patients and the potential effects a biologically active drug could have after treatment of pregnant women. The lessons from thalidomide tragedy immensely contributed towards a paradigm shift in subsequent drug approval processes. It sharply underscored the importance of rigorous and relevant testing of the drug candidates prior to their introduction into the marketplace [

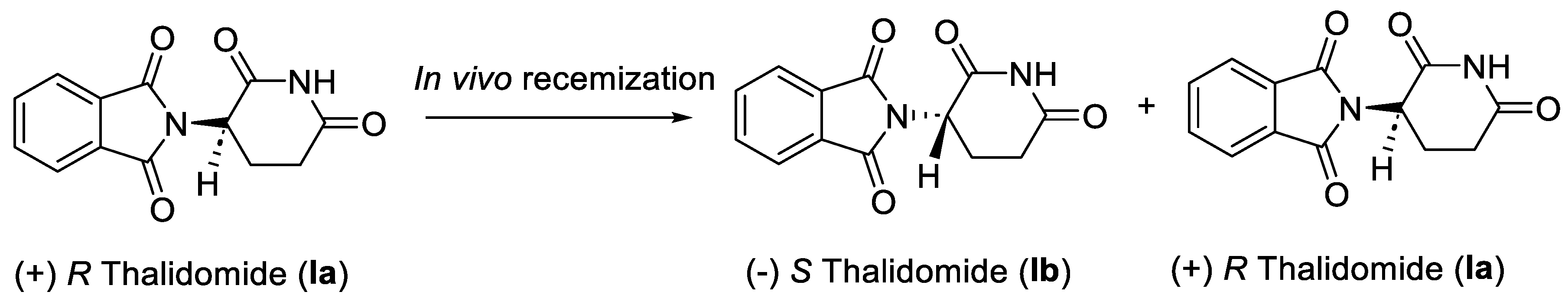

15]. Successive studies revealed that out of the two stereoisomers of racemic thalidomide (

I), only the (+)

R enantiomer

Ia is effective against morning sickness, and the (-)

S enantiomer

Ib is a teratogen. However, the two enantiomers interconvert into each other in vivo (

Scheme 1) [

16]. Therefore, administering enantiomerically pure (+)

R thalidomide

Ia was not a solution to circumvent its teratogenic effect in humans.

1.1. Pharmacology of Thalidomide

Sold under the brand name Thalomid

®, thalidomide (

I) is classified as imide drugs due to the presence of two imide groups in its chemical structure (

Figure 2). Despite the inherent teratogenic property leading to its withdrawal in 1961, thalidomide (

I) was later re-introduced in the market as a medication to treat certain types of cancers, such as multiple myeloma and erythema nodosum leprosum [

17,

18]. It is also being used for several inflammatory disorders [

19]. However, as per FDA regulations patients must enroll in the thalidomide Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program to ensure contraception adherence during the treatment [

14].

The mechanism of action of thalidomide (

I) is not completely understood. However, it is an immunomodulatory drug (iMiD) which has been demonstrated to display immunosuppressive and anti-angiogenic activity through modulating the release of inflammatory mediators like tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [

17,

18]. It binds to the receptor cereblon, to selectively degrade the transcription factors which are vital for the proliferation and survival of malignant myeloma cells [

18]. Therefore, it is sometimes referred to as cereblon modulator drug [

20]. Thalidomide (

I) also appears to inhibit protein (ca. myeloid differentiating factor 88) involved in TNF-α production signaling pathway, at the protein and RNA level. Thereby, exhibiting anti-inflammatory activity [

19].

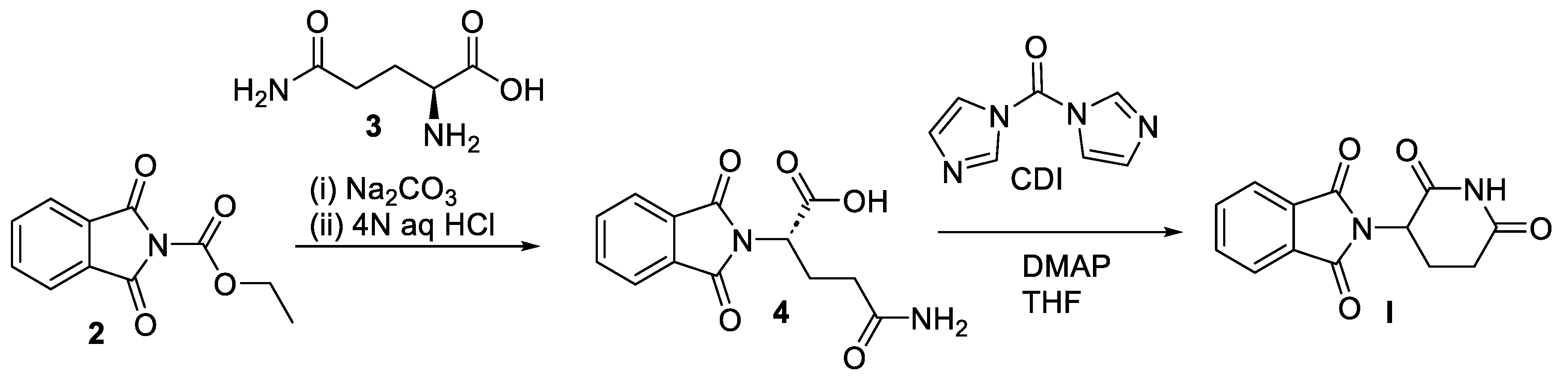

1.2. Chemical Synthesis of Thalidomide

The traditional synthesis of thalidomide (

I) involves a three-step sequence starting with L-glutamic acid and phthalic anhydride [

21]. However, the overall yield of

I achieved under these conditions was around 31%. This methodology also required cumbersome purification steps. Later, Muller and coworkers reported a modified two-step synthesis of

I with significant improvement in the overall yield (

Scheme 2) [

21]. In the initial step

N-carbethoxyphthalimide (

2) was treated with L-glutamine (

3) to produce

N-phthaloyl-L-glutamine (

4). The cyclization of

4 was then carried out in the presence of 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) and catalytic amount of

N,

N-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) in solvent tetrahydrofuran (THF) to yield

I in an overall yield of 61% having 99% purity. Following this report, a review article was published in 2007 by Shibata and co-workers summarizing various known syntheses of thalidomide [

22].

2. Pomalidomide

Pomalidomide (

II) in an analog of thalidomide (

I) having an amino substitution on the aromatic ring of isoindoline-1,3-dione moiety (

Figure 2). It is indicated for patients with multiple myeloma and Kaposi’s sarcoma.

2.1. Pharmacology of Pomalidomide

Pomalidomide (

II) is available in the market under the brand names Imnovid

® and Pomalyst

®. Being an analog of thalidomide (

I),

II is classified as a second generation iMiD antineoplastic agent, and it is 100 times more potent than

I [

23]. Pomalidomide (

II) is primarily used for treatment of patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. It is also prescribed for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma in AIDS patients as well as in HIV-negative patients [

24]. Analogous to the mechanism of action of

I, the primary target of pomalidomide (

II) is the protein cereblon [

20]. It enhances T cell and natural killer (NK) cell-mediated immunity and inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6). This leads to inhibition in proliferation and induction of apoptosis of various tumor cells [

18,

25]. Pomalidomide (

II) has also been shown to be a transcriptional inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme, thereby reducing prostaglandin levels and exerting anti-inflammatory effects like other iMiDs [

25].

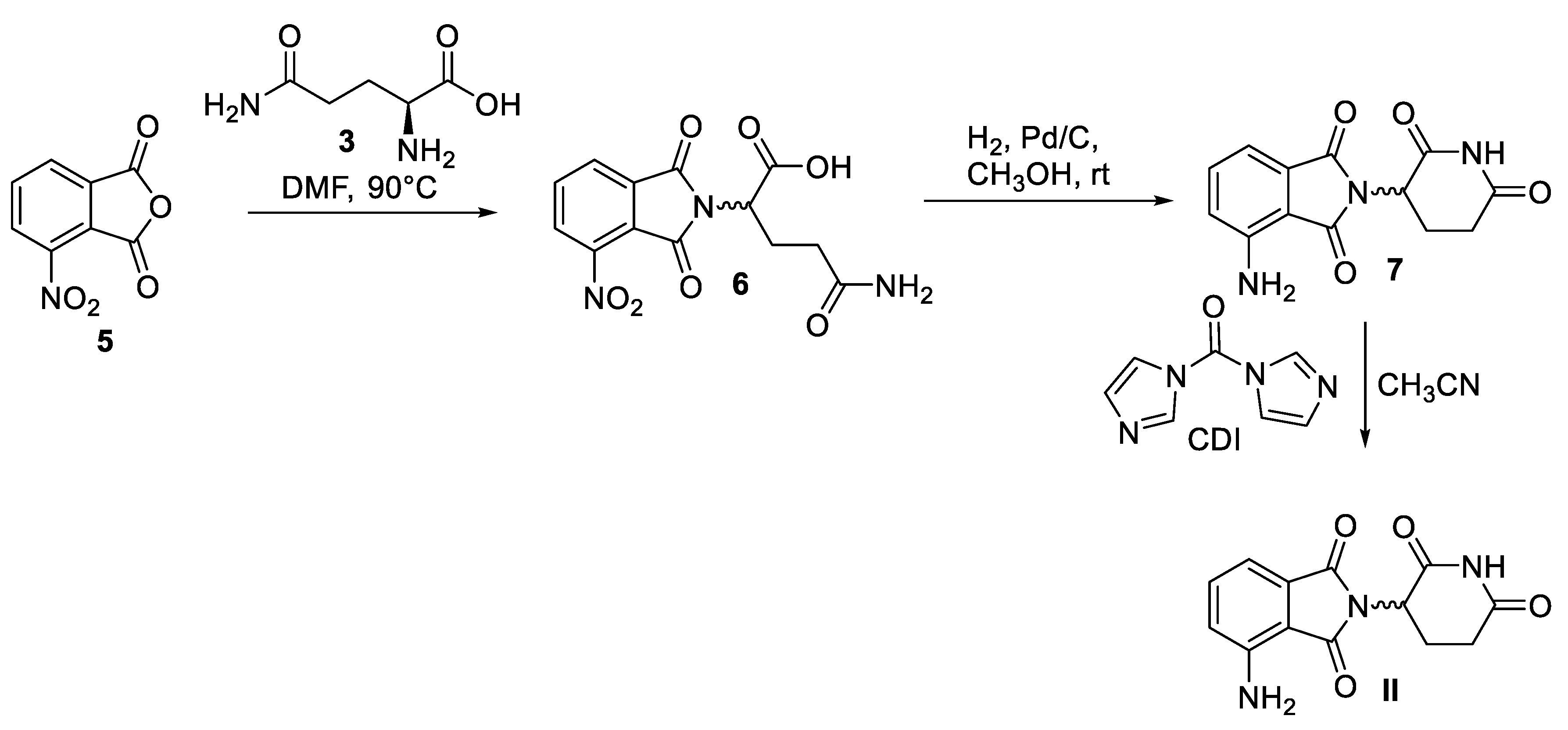

2.2. Chemical Synthesis of Pomalidomide

Like thalidomide (

I), pomalidomide (

II) rapidly undergoes interconversion between its

R- and

S- enantiomers in vivo. A scalable synthesis of racemic

II follows the reaction sequence outlined in

Scheme 3 [

26]. Condensation of commercially available 3-nitrophthalic anhydride (

5) and L-glutamine (

3) in

N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) furnishes nitrothalimide

7 in the first step. Interestingly, stereocenter derived from

3 undergoes racemization in this step under neutral conditions at elevated temperatures. A Pd/C-mediated hydrogenative reduction of the nitro functionality yields aminothalimide

7 in the subsequent step. Finally, treatment of 7 with CDI in refluxing acetonitrile results in formation of pomalidomide (

II) as the racemate in 87% overall yield.

3. Apremilast

Like phthalidomide (

II), the chemical structure of apremilast consists of oxidized isoindoline heterocyclic core in which N is tethered with an alkyl fragment having ether linkages and sulfone functionality. In addition, an

N-acetyl group is substituted on the aromatic ring of phthalimide moiety (

Figure 2). Apremilast is indicated for the treatment of inflammatory conditions in patients with psoriasis.

3.1. Pharmacology of Apremilast

Sold under the brand name Otezla

®, apremilast (

III) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used for the treatment of inflammatory autoimmune disease called psoriasis. Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition which causes rash, itchy and scaly patches on knees, elbows, trunk and scalp. This medication is also prescribed for psoriatic arthritis in people commonly affected with psoriasis [

27]. In fact, it is the first oral therapy to receive FDA approval for the treatment of adults with active psoriatic arthritis [

27]. Quite recently,

III was approved for the treatment of oral ulcers for another auto-immune condition called Behcet’s disease which is associated with recurrent skin, blood vessel and central nervous system inflammation [

28]. Apremilast (

III) administration induces a cascade of actions which decreases the levels of inflammatory mediators responsible for inflammatory symptoms [

29]. Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) enzyme is one of the most important modulators of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling cascade. More precisely,

III works by selectively inhibiting PDE4 enzyme responsible for the activity of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [

29]. This leads to increased intracellular cAMP levels to control anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and suppresses inflammation by decreasing the expression of TNF- α, IL, and other pro-inflammatory mediators [

30]. The use of

III also causes a decrease in pro-inflammatory nitric oxide synthase activity, which is responsible for the synthesis of nitric oxide. This prevents trafficking of microphages and myeloid dendritic cells to the dermis and epidermis in psoriatic skin, thereby exhibiting anti-inflammatory activity.

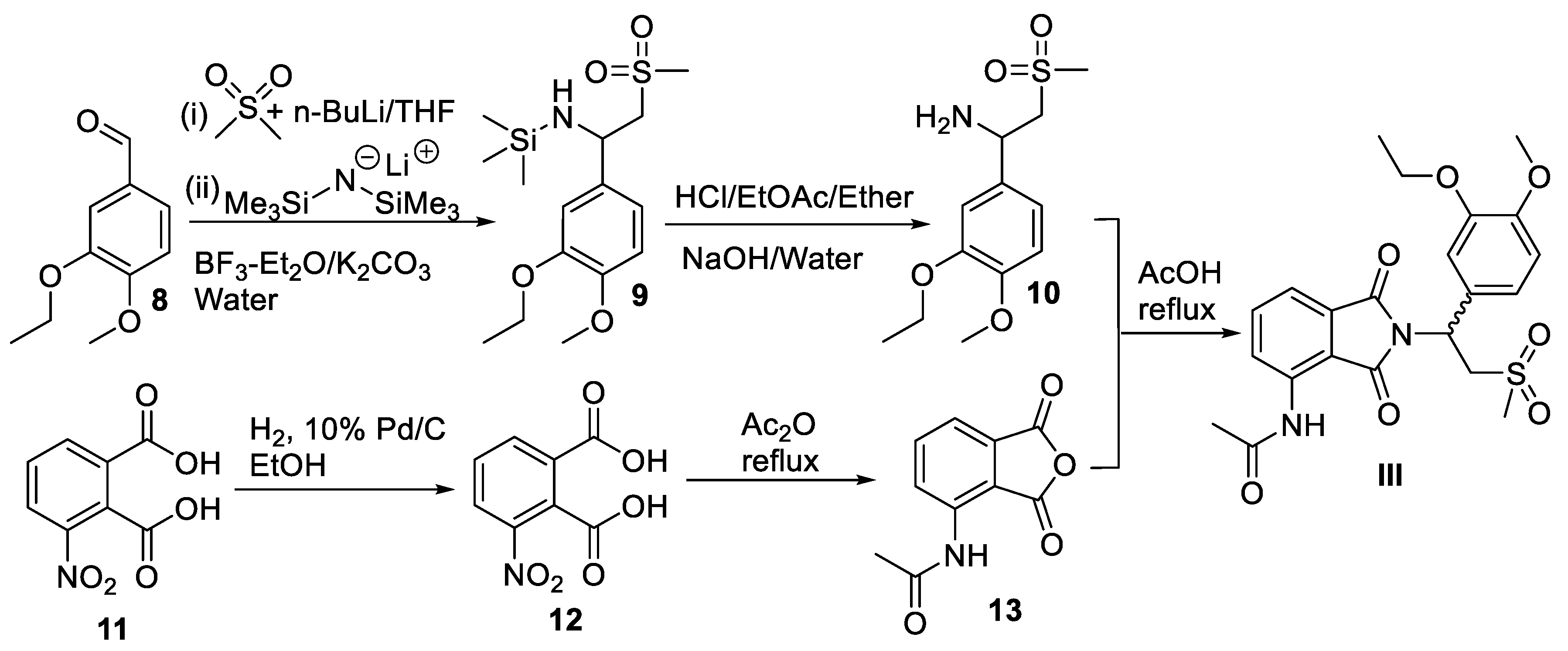

3.2. Chemical Synthesis of Apremilast

The chemical synthesis of this highly functionalized racemic phthalidomide molecule, apremilast (

III), was first reported by Celgene corporation via a convergent strategy (

Scheme 4) [

31]. In the first step 3-ethoxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (

8) was mixed with preformed lithium dimethyl sulfone, followed by the addition of lithium hexamethyldisilazide and boron trifluoride etherate to produce trimethylsilylated amine

9. Hydrolysis of

9 furnished 1-(3-thoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2-(methyl sulfonyl)ethan-1-amine (

10). Separately, 3-nitrophthalic acid (

11) was reduced under catalytic hydrogenation conditions to

12 followed by its concomitant acetylation and condensation in refluxing acetic anhydride to yield acetylated phthalic anhydride

13. Finally, amine

10 was condensed with phthalic anhydride

13 in acetic acid at 110 °C to afford apremilast (

III) as a racemate in 59% yield. Following this methodology, several strategies have been developed for the resolution of enantiomers of

III, as well as for the synthesis of

III in enantiomerically pure forms [

31].

4. Phosmet

Phosmet (

IV) also belongs to the thalidomide group of compounds containing isoindoline-1,3-dione heterocyclic core in which N is tethered with a thiophosphate group (

Figure 2). It is used as a pesticide used against coddling moths.

4.1. Pharmacology of Phosmet

Unlike the thalidomide derivatives discussed above, phosmet (

IV) is a non-systemic insecticide belonging to the organophosphate group of pesticides [

32]. It is primarily used to control coddling moths in the cultivation of apple trees. It is also effective against aphids, suckers, mites, and fruit flies on other fruit crops, ornamental plants and vines. The insecticidal property of phosmet (

IV) stems from its ability to inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity by irreversibly phosphorylating the enzyme. AChE normally hydrolyses acetylcholine neurotransmitter to acetic acid and choline. The inhibition results in an excess of acetylcholine at neuromuscular junction and at synapse of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. Thus, exerting neurotoxicity at both the central and peripheral nervous systems of the pests [

33].

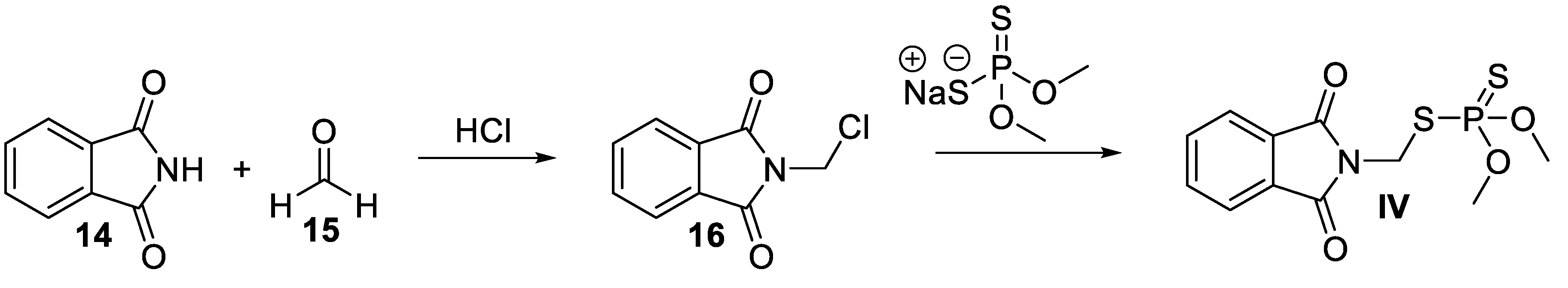

4.2. Chemical Synthesis of Phosmet

The chemical synthesis of phosmet (

IV) is outlined in

Scheme 5. First, commercially available phthalimide (

14) was

N-chloromethylated in situ using aqueous formaldehyde (

15) and hydrogen chloride gas to

N-chloromethylphthalimide (

16). Finally, nucleophilic substitution of chloride

16 with sodium dimethyldithiophosphorodithioate resulted in formation of phosmet (

IV) [

34].

5. Lenalidomide

Lenalidomide (

V) is a derivative of thalidomide (

I) in which the pyrrolidine ring of isoindoline skeleton is only mono oxidized. This partially oxidized heterocyclic core is referred as isoindolin-1-one. Like thalidomide (

I), the N atom is substituted with a piperidinedione moiety in lenalidomide (

V,

Figure 2). It is indicated for the treatment and maintenance therapy for adult patients with multiple myeloma.

5.1. Pharmacology of Lenalidomide

The drug lenalidomide (

V) is sold under the name of Revlimid

®. Similar to thalidomide (

I),

V is a cereblon modulator second generation iMiD imide drug with potent antineoplastic, anti-angiogenic, and anti-inflammatory properties [

35]. It is prescribed for the treatment of multiple myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes, mental cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and marginal zone lymphoma [

36]. It was envisaged that the replacement of the phthaloyl ring with isoindolinone ring will result in increased stability of the molecule and may lead to its increased bioavailability [

37]. Like thalidomide, lenalidomide also exists as a racemic mixture of

S (-) and

R (+) forms, however, it is much more potent and safer compared to thalidomide (

I) [

17,

38]. Nonetheless, the potential of teratogenic side effect still exists in lenalidomide (

V)[

39]. Patients must enroll in the lenalidomide REMS program to ensure contraception adherence during the treatment [

14].

Being an iMiD drug, lenalidomide (

V) works through various mechanisms of actions that promote malignant cell death and enhance host immunity [

40]. The direct cytotoxicity of lenalidomide (

V) is exerted by binding to the receptor cereblon, which in turn increases apoptosis and inhibits the proliferation of hematopoietic malignant cells. It also works to limit the invasion or metastasis of tumor cells and inhibits angiogenesis [

38,

40]. Lenalidomide (

V) exhibits indirect antitumour effects via its immunomodulatory actions by inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, regulating T cell co-stimulation and enhancing NK cells. It is estimated that lenalidomide (

V) is about 100-1000 times more potent in stimulating T cell proliferation than thalidomide (

I) [

38].

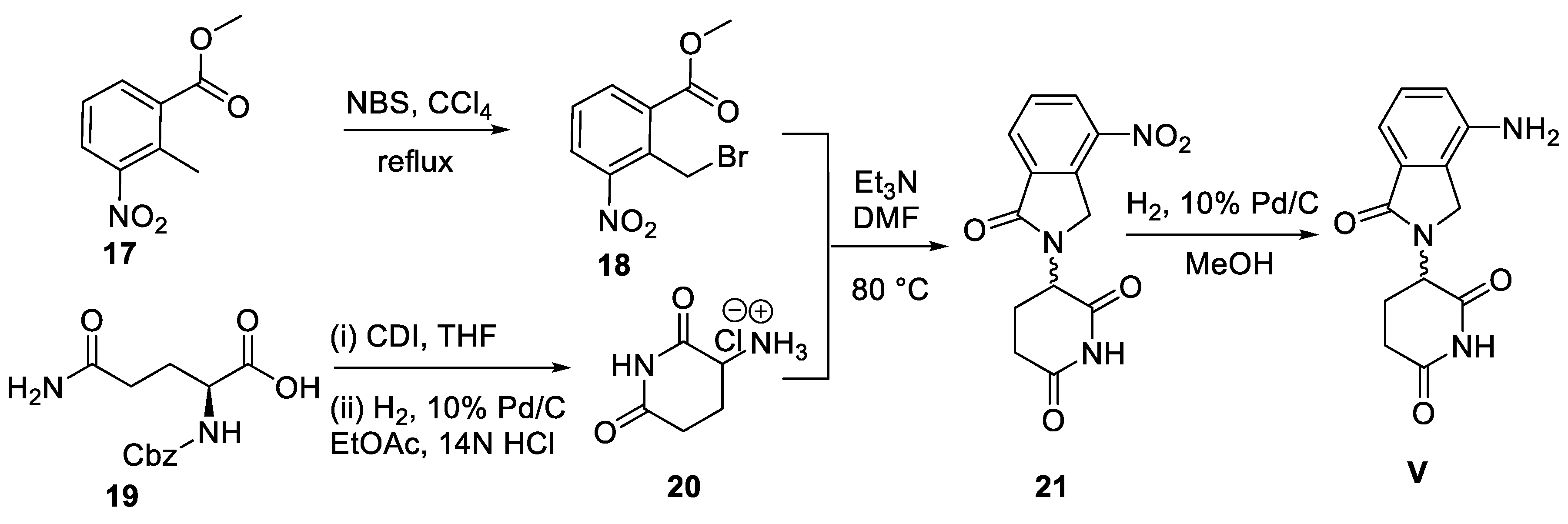

5.2. Chemical Synthesis of Lenalidomide

A concise synthesis of lenalidomide (

V) has been reported by Muller and co-workers (

Scheme 6) [

37]. The methodology involves treatment of methyl (2-methyl-3-nitro)benzoate (

17) with

N-bromosuccinamide to obtain methyl 2-(bromomethyl-3-nitro)benzoate (

18) first. Simultaneously, benzyloxycarbonyl (Cbz)-protected L-glutamine

19 was subjected to cyclization in the presence of CDI, followed by deprotection of the Cbz group by hydrogenolysis to produce 3-aminopiperidine-2,6-dione hydrochloride salt (

20). The condensation of compound

18 and

20 in DMF yielded the nitro analog

21 of

V. The nitro functionality of

21 was then reduced to an amino group by a Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenation step to furnish

V as a racemate.

7. Indoprofen

Like profens, the chemical structure of indoprofen (

VI) has a close resemblance with analgesic ibuprofen [

41]. It consists of the oxidized isoindoline heterocycle, isoindolin-1-one, in which the N atom is tethered with 2-phenylpropanoic acid at para position (

Figure 2). Indoprofen has been indicated for the treatment of inflammatory conditions in arthritis patients.

1.6. Pharmacology of Indoprofen

Indoprofen (

VI) is classified as an NSAID which has anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. It was used in rheumatoid arthritis, osteo-arthritis and postoperative pain management [

42]. Like any other NSAID, the mechanism of action for its anti-inflammatory effects involves inhibition of enzyme cyclooxygenases (COX) [

43]. In particular, indoprofen (

VI) inhibits both isoforms of COX (COX-1 and COX-2), which reduces the production of prostaglandins, the mediators of inflammation. This mechanism also helps in the reduction of pain perception, hence exhibiting analgesic and antipyretic (fever reducing effects) properties. However, following several post marketing reports of severe gastrointestinal bleeding, indoprofen (

VI) was withdrawn worldwide from market in 1980’s [

44]. Interestingly, there has been a renewed interest in indoprofen (

VI) as it is shown to be potentially beneficial for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy, a fetal pediatric genetic disease, and overall muscle weakness [

45].

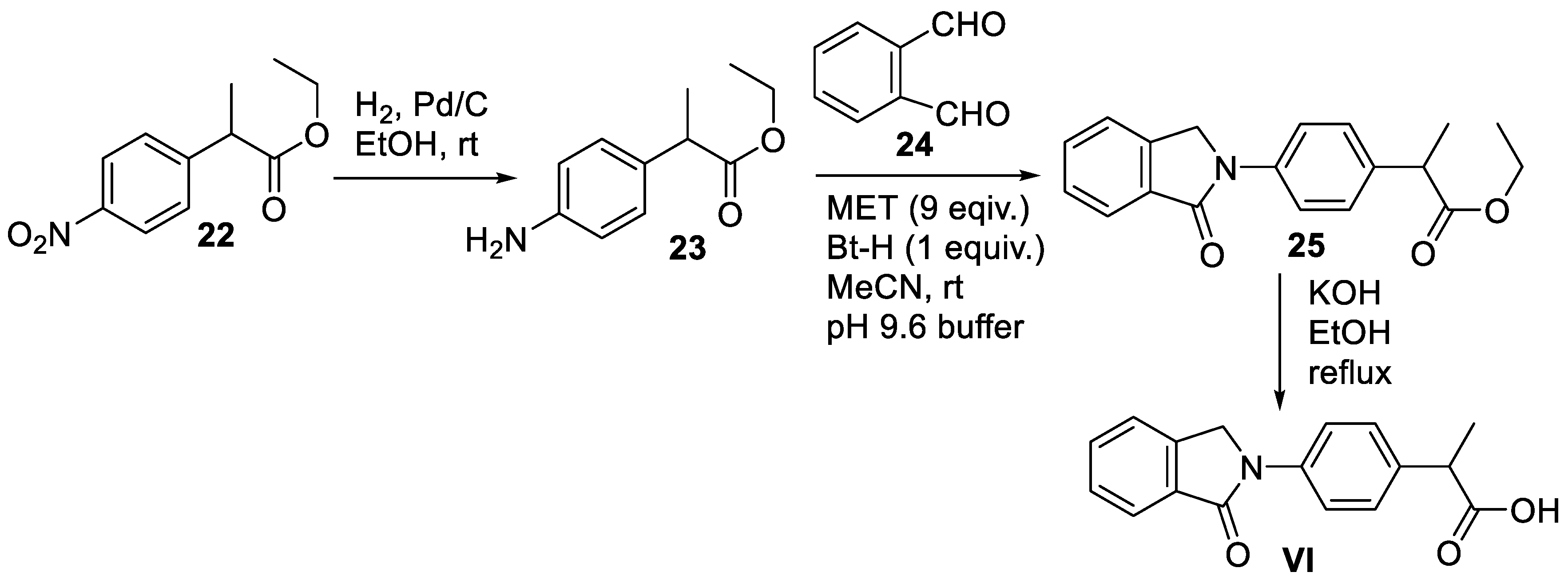

1.6.1. Chemical Synthesis of Indoprofen

The traditional synthesis of racemic indoprofen (

VI) has been described in four steps starting from 2-(4-nitrophenyl)propionate (

22) 1n 1973 [

46]. More recently, a shortened 3-step synthesis of

VI in 41% overall yield has been reported by Takahashi and co-workers in 2016, as depicted in

Scheme 7 [

47]. Compound

22 was initially subjected to 5% Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenation conditions in ethanol to produce an aniline derivative

23. A Mannich condensation between

23 and

o-phthalaldehyde (

24) in the presence of 1,2,3-1

H-benzotriazole (Bt-H) and excess of 2-mercaptoethanol (MET) in acetonitrile at room temperature then resulted in indoprofen ethyl ester

25. Next, base mediated hydrolysis of

25 furnished indoprofen (

VI).

7. Chlorthaidone

The chemical structure of chlorthiadone (

VII) possesses an oxidized isoindoline core, isoindolin-1-one, which has aryl and hydroxy substitutions at position 3. The aryl group is further substituted with chloro and sulfonamide functionalities (

Figure 2). This drug is indicated for the management of hypertension and edema.

7.1. Pharmacology of Chlorthalidone

Chlorthalidone (

VII) is sold in the market under the trade names Edarbyclor

®, Tenoretic

®, and Thlitone

®. It is classified as a diuretic used for the treatment of hypertension or high blood pressure. It is considered a first-line therapy for the management of uncomplicated hypertension, as it reduces the risk of stroke, myocardial infraction and heart failure [

48]. The drug

VII is also prescribed for the management of edema caused by conditions such as heart failure or renal impairment [

48]. The exact mechanism of action of chlorthalidone (

VII) is under debate. However, it appears

VII improves blood pressure and swelling by preventing water absorption from the kidneys through inhibition of the Na

+/Cl

- symporter membrane protein. This increased diuresis results in decreased plasma and extracellular fluid volumes, which ultimately leads to a reduction in blood pressure [

49]. Furthermore, chlorthalidone (

VII) has been shown to be effective in decreasing platelet aggregation, vascular permeability, and promoting angiogenesis. These pathways are presumed to be crucial in cardiovascular risk reduction effects displayed by chlorthalidone (

VII).

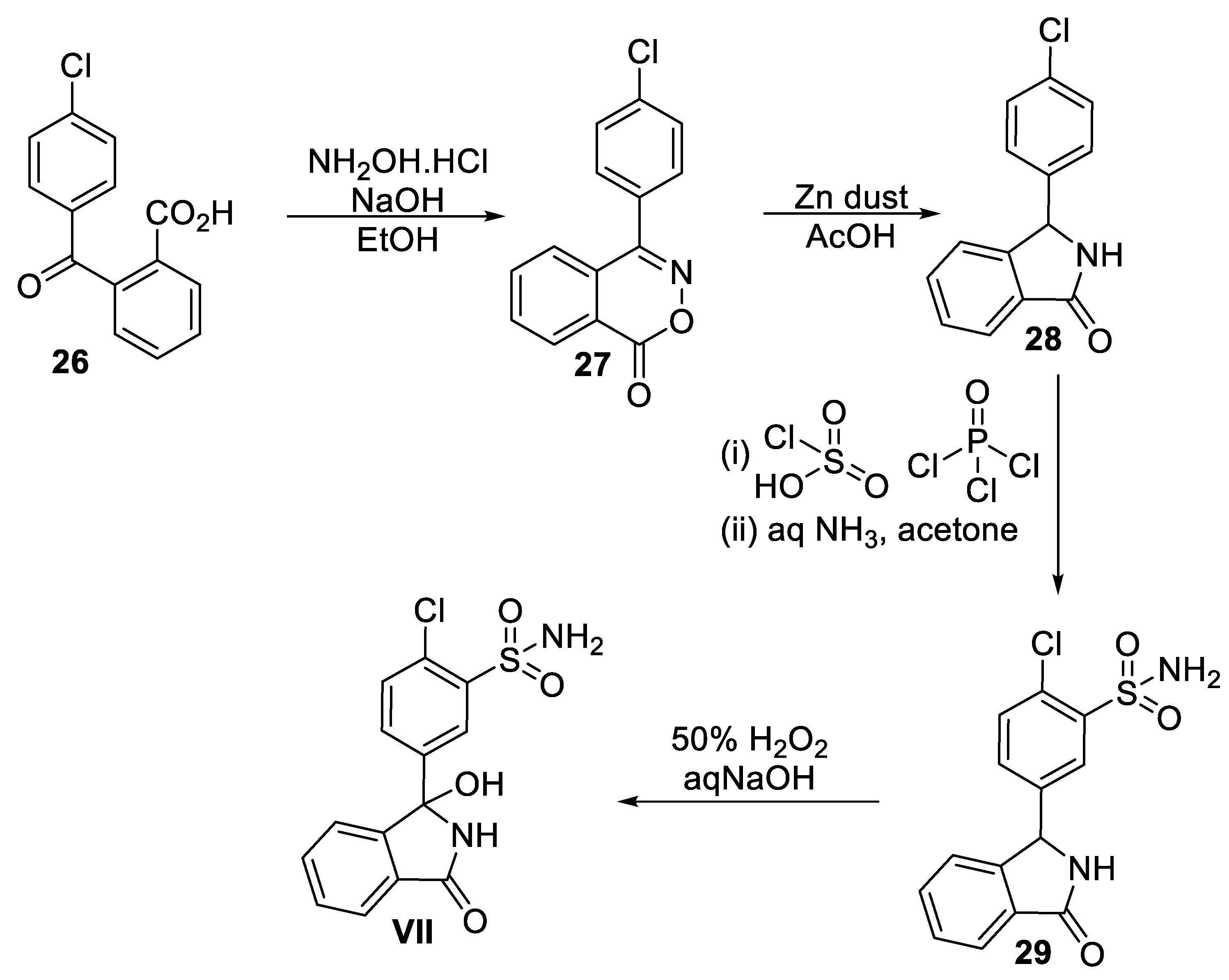

7.2. Chemical Synthesis of Chlorthalidone

The synthetic method for accessing chlorthalidone was first described by Graf and co-workers [

50]. A number of patents also describe the synthesis of

VI [

51]. A recently described scalable improved process of preparing chlorthalidone (

VI) with high purity is presented here (

Scheme 8) [

52]. Commercially available 2-(4-chlorobenzoyl)benzoic acid (

26) was first reacted with hydroxylamine hydrochloride in the presence of NaOH in ethanol to produce benzoxazine-1-one (

27). Treatment of compound

27 with zinc dust in acetic acid led to the formation of 3-(4’-chlorophenyl)phthalimidine (

28) upon ring contraction. Subsequently, the reaction of

28 with chlorosulfonic acid in the presence of a chlorinating agent, phosphorus oxychloride, furnished sulfonyl chloride intermediate, which was then subjected to aqueous ammonia in acetone to give the penultimate sulfonamide intermediate

29. Finally, a regioselective hydroxylation of isoindolin-1-one core at position 3 mediated by hydrogen peroxide and sodium hydroxide resulted in chlorthalidone (

VII) in 51% overall yield [

52].

8. Midostaurin

Midostaurin (

VIII) is an

N-benzoyl derivative of the natural product staurosporine (

30,

Scheme 9) isolated from

Streptomyces staurosporeus [

53]. It belongs to indolocarbazole class of compounds. The chemical structure of

VIII consists of an isoindolin-1-one core flanked with indole rings on both sides. The N atoms of the indole rings are attached to one sugar unit (

Figure 2). Midostaurin is indicated for the treatment of leukemia in adult patients.

8.1. Pharmacology of Midostaurin

Available under the brand name Rydapt

®, midostaurin (

VIII) is a multitarget kinase inhibitor antineoplastic agent used for the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with specific genetic mutation called FLT3 [

53]. It is also used for aggressive systemic mastocytosis, systemic mastocytosis with associated hematologic neoplasm, or mast cell leukemia. Midostaurin (

VIII) has been shown to increase the overall survival rate in patients with AML as an adjunct therapy along with chemotherapeutic agents [

53]. Several reports recognized FLT3 mutations were an important prognostic factor in AML. Midostaurin (

VIII) and its major active metabolites inhibit the activity of mutant FLT3 tyrosine kinases. Consequently, the inhibition of FLT3 receptor signaling cascades induces apoptosis of target leukemia cells expressing target receptors and mast cells, thus, exhibiting antiproliferative activity [

54].

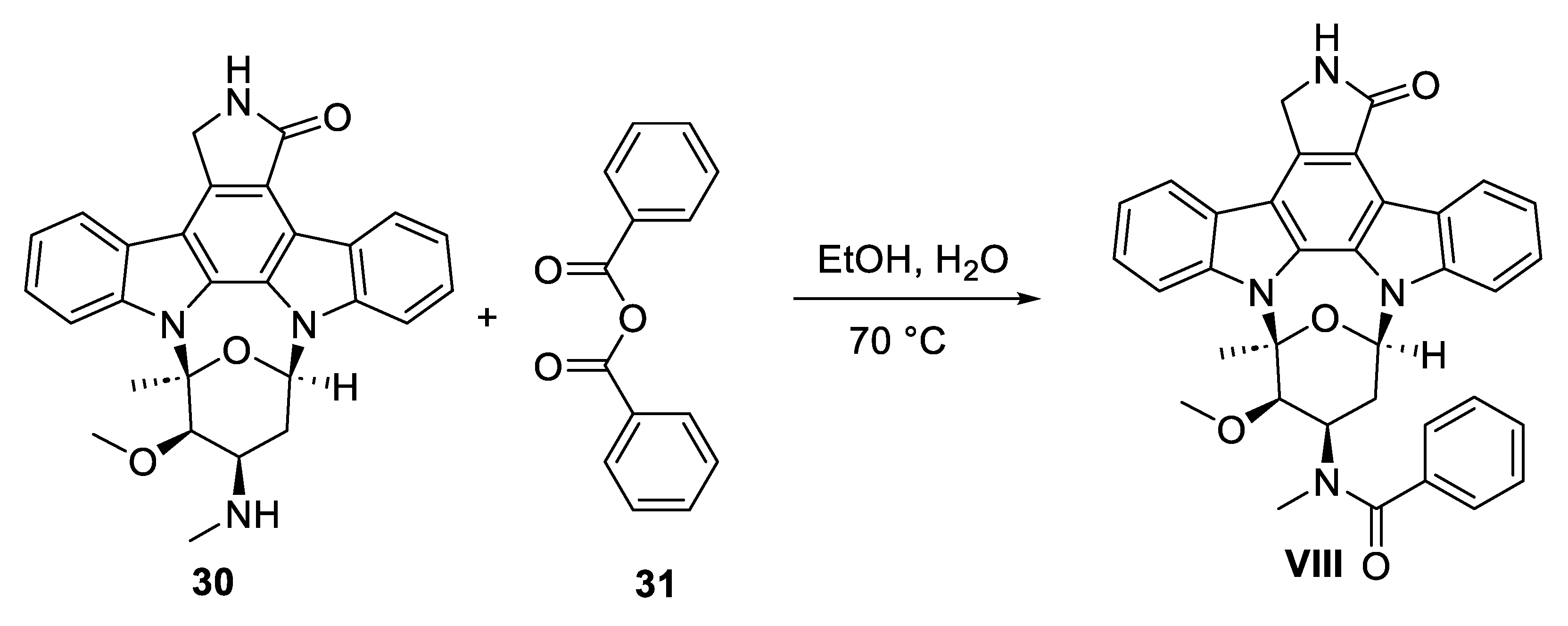

8.2. Chemical Synthesis of Midostaurin

Midostaurin (

VIII) has been synthesized semi-synthetically in one-step starting from staurosporine (

30) natural product, as depicted in

Scheme 9 [55a]. Compound

30 can be conveniently obtained the fermentation broth of the marine bacterium

Streptomyces staurosporeus culture [55b]. Treatment of

30 with benzoic anhydride (

31) in ethanol/water mixture at 70 °C resulted in midostaurin (

VIII) in 91.5% yield with high purity.

9. Mazindol

The chemical structure of mazindole (

IX) consists of isoindoline heterocycles fused with an additional five-membered N containing ring between positions 1 and 2. In addition, hydroxyl and 4-chlorophenyl groups are substituted at position 3 of the isoindoline skeleton (

Figure 2). It is used in short-term treatment of exogeneous obesity in patients having risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia.

9.1. Pharmacology of Mazindol

Sold under the trade name Sanorex

®, mazindol (

IX) is a tricyclic sympathomimetic agent [

56]. A sympathomimetic drug is a simulant which mimics the effects of endogenous agonists of the sympathetic nervous system such as catecholamines, norepinephrine and dopamine. It was first approved by the FDA in 1973 for the treatment of obesity in adults. However, due to low sales,

IX was voluntarily withdrawn from the market in the early 2000s. This drug is still approved in Mexico, Central America, Japan, and Argentina for short-term use for treatment of obesity in combination with lifestyle changes, such as caloric restrictions, exercise, and behavior modifications. Mazindol’s efficacy as an anti-obesity drug is due to its anorexigenic activity, that is, causing a loss of appetite. The suppression of appetite by

IX is caused because of the inhibition of feeding center of lateral hypothalamus [

57]. However, mazindol (

IX) is only approved for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in the United States, which is a genetic condition that causes muscle weakness and heart problems in children [

58]. Given the pharmacologic profile of

IX, it is currently being investigated for efficacy in treating ADHD, schizophrenia, reducing cravings for illicit drug cocaine, and neurobehavioral disorders [

59].

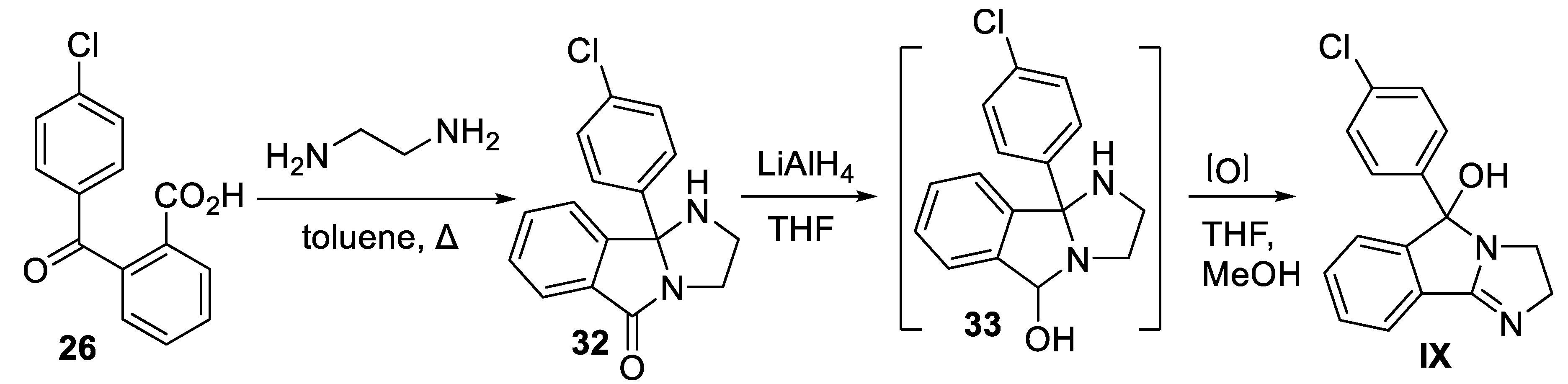

9.2. Chemical Synthesis of Mazindol

The chemical synthesis of racemic mazindol (

IX) has been reported by Aeberli and co-workers using a commercially available precursor, 2-(4-chlorobenzoyl)benzoic acid (

26) [

60]. First, condensation of benzoic acid

26 with ethylenediamine by azeotropic removal of water resulted in tricyclic product

32 in one-step. Subsequently, reduction of

32 with LiAlH

4 in solvent THF led to the formation of carbinolamine

33, which was directly subjected to aerial oxidation in THF/methanol without its isolation to yield mazindol

IX (

Scheme 10).

10. Chlorisondamine

The chemical structure of chlorisondamine (

X) consists of perchlorinated isoindoline core having bis-quaternary ammonium centers (

Figure 2). It has been used for the treatment of hypertension.

10.1. Pharmacology of Chlorisondamine

Classified as a nicotine receptor antagonist and ganglionic blocker, chlorisondamine (

X) was developed for the treatment of hypertension in 1950’s under the trade name of ‘Ecolid’ [

61]. The initial use of chlorisondamine (

X) not only showed promise in reducing blood pressure but also was instrumental in highlighting the importance of sympathetic activity in blood pressure. It was found to block ganglionic nicotinic receptors only temporarily while showing negligible effect on nicotinic receptors of the neuromuscular junction. Interestingly, chlorisondamine (

X) has the ability to block most of the centrally mediated behavioral effects of nicotine. However, because of polar bis-quaternary structure it does not cross the blood-brain barrier readily. Therefore, a persistent blockade of nicotinic receptors is only possible when

X is injected in a sufficiently high dose systemically. Chlorisondamine (

X) was later withdrawn as it was not well tolerated and caused undesirable side effects [

61]. Despite that, researchers have been routinely using chlorisondamine (

X) to assess autonomic function and vasomotor sympathetic tone in animal models of hypertension [

62].

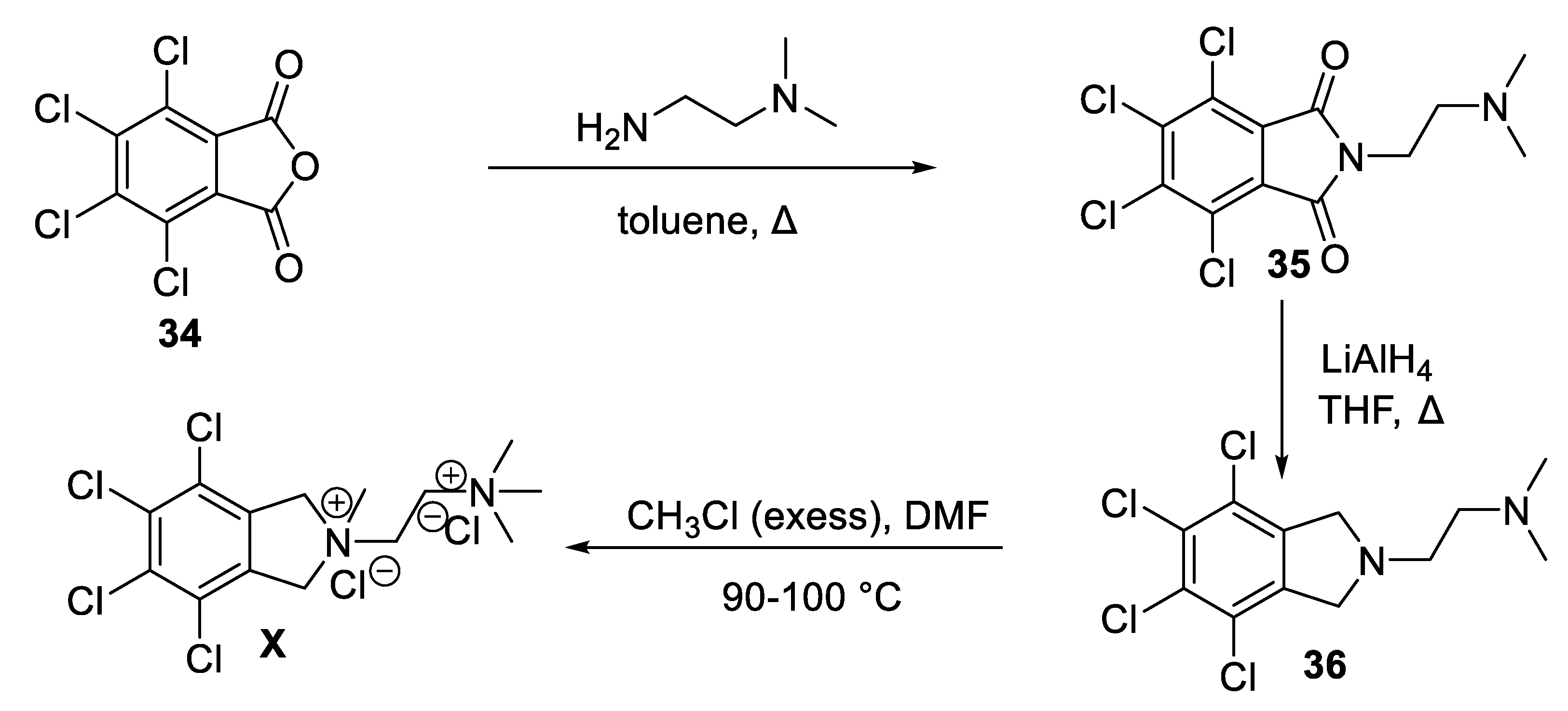

10.2. Chemical Synthesis of Chlorisondamine

Synthesis of chlorisondamine (

X) can be accomplished starting from commercially available tetrachlorophthalanhydride (

34) in three steps, as described in

Scheme 11 [

63]. First, condensation of

34 with

N,N-dimethylethylenediamine produced

N-alkylated phthalimide

35. A stepwise reduction of

35 with LiAlH

4 then led to the formation of isoindoline intermediate

36. Permethylation of

36 in the presence of excess of methyl chloride in DMF is a pressure bomb furnished

X in 36% overall yield [

63].

Conclusion

The isoindoline substructure is found in naturally occurring alkaloids and in synthetic drugs. Derivatives of isoindoline are known to exhibit diverse biological and pharmacological properties. Most importantly, several clinical drugs are known to possess isoindoline-core. We have summarized the biological profile, pharmacology and chemical syntheses of ten isoindoline-based approved or re-approved clinical drugs. Despite the withdrawal of some of these drugs from the marketplace, they are still a subject of intense research investigation in current literature. Overall, the remarkable biological and medicinal properties emanating from isoindoline-based molecules will continue to make them an attractive target for research and exploration.

Acknowledgements

The author (MJ) gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to conduct this research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- (a) Youssef, D.; Patel, R.; Mohapatra, P.; Jha, A. Pharmacology and synthesis of clinical drugs containing isoquinoline core. Trends Org. Chem. 2021, 21,1-17. (b) Kabir, E.; Uzzaman, M.A. A review on biological and medicinal impact of heterocyclic compounds. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100606.

- Ruiz, B.; Chávez, A.; Forero, A.; García-Huante, Y.; Romero, A.; Sánchez, M.; Rocha, D.; Sánchez, B.; Rodríguez-Sanoja, R.; Sánchez, S.; Langley, E. Production of microbial secondary metabolites: regulation by the carbon source. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 36, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Samota, M.K.; Choudhary, M.; Choudhary, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Sharma, A.; Thakur, J. How do plants defend themselves against pathogens-biochemical mechanisms and genetic interventions. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.T.; Jung, J. W.; Kim, N.J. recent advances in the synthesis of biologically active cinnoline, phthalazine and quinoxaline derivatives. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 1265–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, K.N.; Parvez, M.; Back, T.G. Preparation of 1-aryl-substituted isoindoline derivatives by sequential Morita–Baylis–Hillman and intramolecular Diels–Alder reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 1226–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.; Singh, A.; Kaur, N.; Ojha, R.; Nepali, K. Steering the antitumor drug discovery campaign towards structurally diverse indolines. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 94, 103436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starosotnikov, A.M.; Bastrakov, M.A. Cycloaddition reactions in the synthesis of isoindolines. Chem. Heterocl. Compd. 2017, 53, 1181–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, F.J.; Jarvo, E.R. Palladium-catalyzed cascade reaction for the synthesis of substituted isoindolines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4459–4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.P. Thalidomide and congenital abnormalities. Br. Med. J. 1962, 2, 646–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Weagle, R.; Corkum, D.; Kuanar, M.; Mohapatra, P.P.; Jha, A. Convenient access to 5-arylisoindolo [2,1-a]quinolin-11(6aH)-ones. Mol. Divers. 2017, 21, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Chou, T.; ALJaroudi, Z.; Ellis, B.D.; Cameron, T.S. Aza-Diels–Alder reaction between N-aryl-1-oxo-1H-isoindolium ions and tert-enamides: Steric effects on reaction outcome. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaroudi, Z.; Mohapatra, P.P.; Cameron, T.S.; Jha, A. Expedient and diastereoselective synthesis of substituted 6,6a-dihydroisoindolo [2,1-a]quinolin-11(5H)-ones. Synthesis 2016, 48, 4477–4488. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jaroudi, Z.; Mohapatra, P.P.; Jha, A. Facile synthesis of 3-substituted isoindolinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, N.A.; Bwire, R.; Freeman, J.; Houn, F.; Sheehan, P.; Zeldis, J.B. Effectiveness of risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) for lenalidomide and thalidomide: patient comprehension and knowledge retention. Drug Saf. 2017, 40, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Scialli, A.R. Thalidomide: the tragedy of birth defects and the effective treatment of disease. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 122, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Wani, W.A.; Saleem, K.; Haque, A. Thalidomide: a banned drug resurged into future anticancer drug. Curr. Drug Ther. 2012, 7, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.C. Lenalidomide and Thalidomide: Mechanisms of action - similarities and differences. Semin. Hematol. 2005, 42, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krönke, J.; Udeshi, N.D.; Narla, A.; Grauman, P.; Hurst, S.N.; McConkey, M.; Svinkina, T. Heckl, D.; Comer, E.; Li, X.Y.; Ciarlo, C.; Hartman, E.; Munshi, N.; Schenone, M.; Schreiber, S. L.; Carr, S.A.; Ebert, B.L. Lenalidomide causes selective degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in multiple myeloma cells. Science 2014, 343, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Sreedhara, R.C.; Banerjee, S.; Chatterjee, S. TNF-α signaling beholds thalidomide saga: a review of mechanistic role of TNF-α signaling under thalidomide. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, P.P.; Cathers, B.E. Cereblon Modulators: Low molecular weight inducers of protein degradation. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2019, 31, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, G.W.; Konnecke, W.E.; Smith, A.M.; Khetani, V.D. A concise two-step synthesis of thalidomide. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 1999, 3, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Toru, T. Synthesis of thalidomide. In Bioactive Heterocycles II.; Eguchi, S., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti, D.; Vacca, A. Chapter 3 - Anti-angiogenesis in multiple myeloma. In Anti-Angiogenesis Strategies in Cancer Therapeutics.; Mousa, S.A. and Davis, P.J., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, USA, 2017; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, H.K.; Davis, D.A.; Nair, A.; Shrestha, P.; Stream, A.; Yaparla, A.; Yarchoan, R. Mechanism and therapeutic implications of pomalidomide-induced immune surface marker upregulation in EBV-positive lymphomas. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanan-Khan, A.A.; Swaika, A.; Paulus, A.; Kumar, S.K.; Mikhael, J.R.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Dispenzieri, A.; Lacy, M.Q. Pomalidomide: the new immunomodulatory agent for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer. J. 2013, 3, e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.X.; Leverett, C.A.; Kyne, R.E.; Liu, K.K.-. .; Fink, S.J.; Flick, A.C.; O’Donnell, C.J. Synthetic approaches to the 2013 new drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 1895–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fala, L. Otezla (Apremilast), an Oral PDE-4 inhibitor, receives fda approval for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis and plaque psoriasis. Am. Health. Drug Benefits 2015, 8, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hatemi, G.; Mahr, A.; Takeno, M.; Kim, D.; Melikoğlu, M.; Cheng, S.; McCue, S.; Paris, M.; Chen, M.; Yazici, Y. impact of apremilast on quality of life in Behçet’s syndrome: analysis of the phase 3 RELIEF study. RMD Open 2022, 8, e002235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertig, B.A.; Baillie, G.S. PDE4-mediated cAMP signalling. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2018, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.N.; Liu, X.L.; Xiao, J.; Su, G.F. Immunopathogenesis of Behcet’s disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narode, H.; Gayke, M.; Eppa, G.; Yadav, J.S. A review on synthetic advances toward the synthesis of apremilast, an anti-inflammatory drug. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2021, 25, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohanish, R.P. P. Sittig’s Handbook of Pesticides and Agricultural Chemicals (Second Edition).; Pohanish, R.P., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, 2015; pp. 629–724. [Google Scholar]

- Mensching, D.; Volmer, P.A. CHAPTER 125 - Insecticides and Molluscicides. In Handbook of Small Animal Practice (Fifth Edition).; Morgan, R.V., Ed.; W.B. Saunders: Saint Louis, Missouri, USA, 2008, pp. 1197–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F.; Streibert, H.P.; Farooq, S. Acaricides. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry.; Woley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. Weinheim, Germany, 2009, pp 91-190.

- Qiao, S.K.; Guo, X.N.; Ren, J.H.; Ren, H.Y. Efficacy and safety of lenalidomide in the treatment of multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chin. Med. J. 2015, 128, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.; Gowda, S.; Tuscano, J. A comprehensive review of lenalidomide in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2016, 7, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, G.W.; Chen, R.; Huang, S.; Corral, L.G.; Wong, L.M.; Patterson, R.T.; Chen, Y.; Kaplan, G.; Stirling, D.I. Amino-substituted thalidomide analogs: Potent inhibitors of TNF-α production. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 1625–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotla, V.; Goel, S.; Nischal, S.; Heuck, C.; Vivek, K.; Das, B.; Verma, A. Mechanism of action of lenalidomide in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2009, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, J.Y.; Fuchs, A.; Kumar, G. Embryo-fetal exposure and developmental outcome of lenalidomide following oral administration to pregnant cynomolgus monkeys. Reprod. Toxicolo. 2022, 114, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galustian, C.; Dalgleish, A. Lenalidomide: A Novel Anticancer Drug with Multiple Modalities. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2009, 10, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J. Better drug discovery through better target identification. Biotechnol. Healthc. 2005, 2, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Love, A.J.; Ripley, S.H.; Brock-Utne, J.G.; Blake, G.T. Indoprofen, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic which does not depress respiration in normal man. A study comparing indoprofen with morphine. S. Afr. Med. J. 1985, 68, 801–802. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, J.N. The mechanisms of action of NSAIDs in analgesia. Drugs 1996, 52 Suppl 5, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Cho, S.C.; Jeong, H.; Lee, H.; Jeong, M.; Pyun, J.; Ryu, D.; Kim, M.; Lee, Y.; Kim, M.S.; Park, S.C.; Lee, Y.; Kang, J. Indoprofen prevents muscle wasting in aged mice through activation of PDK1/AKT pathway. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 1070–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, M.R.; Root, D.E.; Martino, A.M.; Flaherty, S.P.; Kelley, B.P.; Coovert, D.D.; Burghes, A.H.; Man, N.T.; Morris, G.E.; Zhou, J.H.; Androphy, E.J.; Sumner, C.J.; Stockwell, B.R. Indoprofen upregulates the survival motor neuron protein through a cyclooxygenase-independent mechanism. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (a) Carney, R.W.J.; de Stevens, G. Tertiary aminoacids. United States Patent 4316850, 1982. (b) Nannini, G.; Giraldi, P.N.; Molgora, G.; Biasoli, G.; Spinelli. F.; Logemann, W.; Dradi, E.; Zanni, G.; Buttinoni, A.; Tommasini, R. New analgesic-anti-inflammatory drugs. 1-Oxo-2-substituted isoindoline derivatives. Arzneimittelforschung 1973, 23, 1090–1100, (ChemInform Abstract 1973, 4, 288).

- Takahashi, I.; Kawakami, T.; Hirano, E.; Kimino, M.; Kamimura, S.; Miwa, T.; Tamura, T.; Tazaki, R.; Kitajima, H.; Hatanaka, M. ; Isa, K; Hosoi, S. Application of the mild-condition phthalimidine synthesis with use of 1,2,3-1H-benzotriazole and 2-mercaptoethanol as dual synthetic auxiliaries. effective synthesis of phthalimidines possessing a variety of substituents at 2-position. Heterocycles 2016, 93, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.M.; Lee, C.H.; Chambers, G.K. Systematic review of antihypertensive therapies: does the evidence assist in choosing a first-line drug? Can. Med. Assoc. J. CMAJ 1999, 161, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, M.H.; Johnson, J.A. Mechanisms and pharmacogenetic signals underlying thiazide diuretics blood pressure response. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016, 27, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, W.; Girod, E.; Schmid, E.; Stoll, W.G. Zur Konstitution von Benzophenon-2-carbonsäure-Derivaten. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1959, 42, 1085–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfried, G.; Erich, S.; Stoll, W.G. New isoindoline derivatives. United States Patent 3055904, 1962. Golec, F.A. Jr.; Auerbach, J. Intermediates for the synthesis of phthalimidines. United States Patent 4331600, 1982. Kumar, A.; Singh, D.; Jadhav, A.; Pandya, D.N. An efficient industrial process for 3-hydroxy-3(3’-sulfamyl-4’-chlorophenyl)phtalimidine. International Patent Application Publication WO2005065046, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gadakar, M,; Wagh, G.; Wakchaure, Y.; Thanasekaran, P.; Punde, D. Improved process for the preparation of chlorthalidone. International Patent Application Publication WO2018158777, 2018.

- Manley, P.W.; Weisberg, E.; Sattler, M.; Griffin, J.D. Midostaurin, a Natural Product-Derived Kinase Inhibitor Recently Approved for the Treatment of Hematological Malignancies. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.M.; Manley, P.W.; Larson, R.A.; Capdeville, R. Midostaurin: its odyssey from discovery to approval for treating acute myeloid leukemia and advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (a) Liang, X.; Yang, Q.; Wu, P.; He, C.; Yin, L.; Xu, F.; Yin, Z.; Yue, G.; Zou, Y.; Li, L.; Song, X.; Lv, C.; Zhang, W.; Jing, B. The synthesis review of the approved tyrosine kinase inhibitors for anticancer therapy in 2015-2020. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 113, 105011. (b) Li, G.; Wu, D.; Xu, Y.; He, W.; Wang, D.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L. Synthesis and Antitumor Activity of Staurosporine Derivatives. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2022, 17, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.L.; Scaini, G.; Rezin, G.T.; Jeremias, I.C.; Bez, G.D.; Daufenbach, J.F.; Gomes, L.M.; Ferreira, G.K.; Zugno, A.I.; Streck, E.L. Effects of acute administration of mazindol on brain energy metabolism in adult mice. Acta. Neuropsychiatr. 2014, 26, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S. Clinical Studies with Mazindol. Obes. Res. 1995, 3, 549S–552S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazindol. DrugBank Online, https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00579, accessed 11-03-2024.

- (a) Seibyl, J.P.; Krystal, J.H.; Charney, D.S. Dopamine and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors in treatment of schizophrenia. United States Patent 5447948, 1995. (b) Berger, S.P Dopamine uptake inhibitors in reducing substance abuse and/or craving. United States Patent 5217987, 1993. (d) Kovacs, B.; Pinegar, L. Use of isoindoles for the treatment of neurobehavioral disorders. International Patent Application Publication WO2009155139, 2009.

- Aeberli, P.; Eden, P.; Gogerty, J.H.; Houlihan, W.J.; Penberthy, C. 5-aryl-2,3-dihydro-5H-imidazo [2,1-a]isoindol-5-ols. novel class of anorectic agents. J. Med. Chem. 1975, 18, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bakke, J.L.; Darvill, F.T. ; Chlorisondamine (ecolid) chloride in medical treatment of severe hypertension. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1957, 163, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Souza, L.A.; Cooper, S.G.; Worker, C.J.; Thakore, P.; Feng Earley, Y. Use of chlorisondamine to assess the neurogenic contribution to blood pressure in mice: An evaluation of method. Physiol. Rep. 2021, 9, e14753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (a) Rosen, W.E.; Toohey, V.P.; Shabica, A.C. Tetrachloroisoindolines and related systems. alkylation reactions and inductive Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 3167–3174. (b) Zezula, J.; Wang, H.J.; Woods, A.S.; Wise, R.A.; Jacobson, A.E.; Rice, K.C. The high specific activity tritium labeling of the ganglion-blocking nicotinic antagonist chlorisondamine. J. Label Compd. Radiopharm. 2006, 49, 471–478.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).