Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis

2.3. Sugars

2.4. Organic Acids

2.5. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

2.6. Individual Phenolic Compounds

2.7. Total Anthocyanin Content

2.8. Total and Individual Carotenoid Compounds

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Analysis

3.2. Sugars

3.3. Organic Acids

3.4. Total and Individual Phenolic Content

3.5. Total and Individual Carotenoid Compounds

3.6. Antioxidant Activity

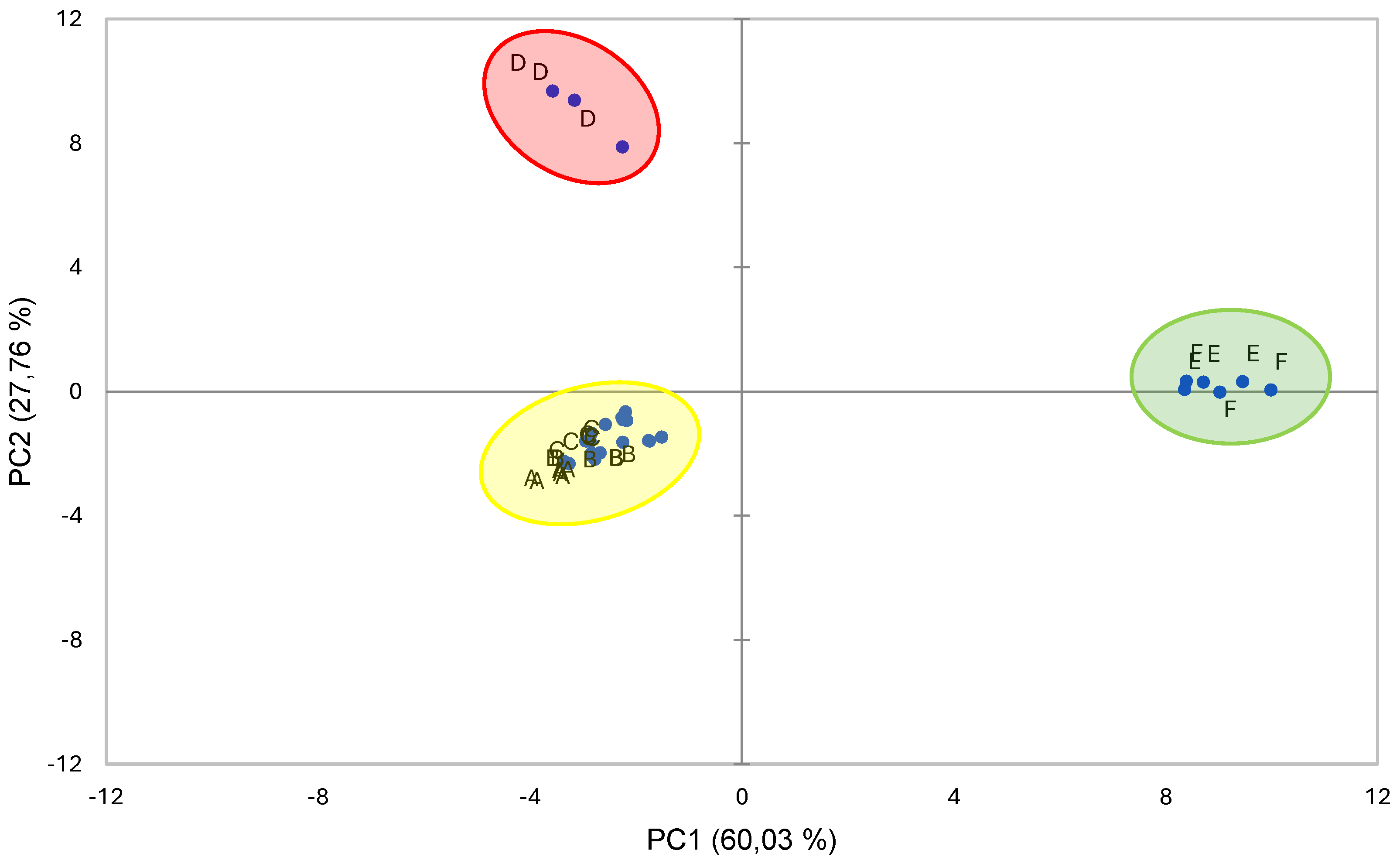

3.7. PCA Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badjakov, I.; Nikolova, M.; Gevrenova, R.; Kondakova, V.; Todorovska, E.; Atanassov, A. Bioactive compounds in small fruits and their influence on human health. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip 2008, 22, 1581–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrovankova, S.; Sumczynski, D.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in different types of berries. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 24673–24706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosme, F.; Pinto, T.; Aires, A.; Morais, M.C.; Bacelar, E.; Anjos, R.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, B. Red fruits composition and their health benefits – A review. Foods 2022, 11(5), 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, C. K.; Brush, S.; Costich, D. E.; Curry, H. A.; de Haan, S.; Engels, J. M. M.; Guarino, L.; Hoban, S.; Mercer, K. L.; Miller, A. J.; Nabhan, G. P.; Perales, H. R.; Richards, C.; Riggins, C.; Thormann, I. Crop genetic erosion: Understanding and responding to loss ofcrop diversity. New Phytologist 2021, 233, 84–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurcík, L.; Bajusová, Z.; Ladvenicová, J.; Palkovic, J.; Novotná, K. Cultivation and processing of modern superfood – Aronia melanocarpa (Black Chokeberry) in Slovak Republic. Agriculture 2023, 13(3), 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.; Vilela, A.; Pinto, A.; Nunes, F.M.; Cosme, F.; Anjos, R. Influence of cultivar and of conventional and organic agricultural practices on phenolic and sensory profile of blackberries (Rubus fruticosus). J Sci Food Agric 2018, 98, 4616–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, M.; Arikan, S. An investigation on the morphological, physiological, and biochemical reaction of the ‘Viking’ aronia cultivar to lime exposure. Sci Hortic 2024, 336, 113456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, R.; Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, C. Research on the extraction, purification and determination of chemical components, biological activities, and applications in diet of black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa). Chin J Anal Chem 2023, 51(10), 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Arumuggam, N.; Amararathna, M.; De Silva, A.B.K.H. The potential health benefits of haskap (Lonicera caerulea L.): Role of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside. J Funct Foods 2018, 44, 24-39. [CrossRef]

- Commission implementing regulation (EU) 2018/1991 of 13 December 2018.

- Chen, J.; Ren, B.; Bian, C.; Qin, D.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, A.; Huo, J.; Gang, H. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal molecular mechanisms associated with the natural abscission of blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) ripe fruits. Plant Physiol Biochem 2023, 199, 107740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kithma, A.B.; De Silva, H.; Vasantha Rupasinghe, H.P. Polyphenols composition and anti-diabetic properties in vitro of haskap (Lonicera caerulea L.) berries in relation to cultivar and harvesting date. J Food Compos Anal 2020, 88, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Feng, X.; Song, L.; Gao, H.; Cao, B. Fruit morphological and nutritional quality features of goji berry (Lycium barbarum L.) during fruit development. Sci Hortic 2023, 308, 111555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggioni, L.; Romi, M.; Guarnieri, M.; Cai, G.; Cantini, C. Nutraceutical profile of goji (Lycium barbarum L.) berries in relation to environmental conditions and harvesting period. Food Biosci 2022, 49, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mi, J.; Yu, L.; Zhang, F.; Lu, L.; Luo, Q.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Cao, Y. A comprehensive review of goji berry processing and utilization. Food sci nutr 2023, 11(12), 7445–7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Xu, J.; Sheng, L.; Song, K. Comprehensive utilization technology of Aronia melanocarpa. Molecules 2024, 29, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, T.; Su, S.; Wang, L.; Tang, Z.; Huo, J.; Song, H. Exploring bitter characteristics of blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) berries by sensory-guided analysis: Key bitter compounds and varietal differences. Food Chem 2024, 457, 140150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, R.; Ramos, M.; Nicolás, N.; Sánchez, F.M.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Calvo, P. Classification of goji Berry (Lycium barbarum L.) varieties according to physicochemical and bioactive signature. Eur Food Res Technol 2024, accepted 03/11/2024.

- Fatchurrahman, D.; Amodio, M.L.; Colelli, G. Quality of Goji Berry Fruit (Lycium barbarum L.) Stored at Different Temperatures. Foods 2022, 11, 3700. [CrossRef]

- Capotorto, I.; Amodio, M.L.; Diaz, M. T.B.; de Chiara, M.L.V.; Colelli, G. Effect of anti-browning solutions on quality of fresh-cut fennel during storage. Postharvest Biol Technol 2018, 137, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano Durán, R.; Fernández Sánchez, J.E.; Velardo-Micharet, B.; Rodríguez Gómez, M.J. Multivariate optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction for the determination of phenolic compounds in plums (Prunus salicina Lindl.) by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Instrum Sci Technol 2020, 48(2), 113–127. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstand, R.E. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacarías-García, J.; Guiselle, C.; Gil, J.V.; Navarro, J.L.; Zacarías, L.; Rodrigo, M.J. Juices and By-products of Red-Fleshed Sweet Oranges: Assessment of Bioactive and Nutritional Compounds. Foods 2023, 12(2), 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragovic-Uzelac, V.; Levaj, B.; Mrkic, V.; Bursac, D.; Boras, M. The content of polyphenols and carotenoids in three apricot cultivars depending on stage of maturity and geographical region. Food Chem 2007, 102(3), 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohoyo, G.; Domínguez, D.; García-Parra, J.J.; González-Gómez, D. UHPLC as a suitable methodology for the analysis of carotenoids in food matrix. Eur. Food Res Technol 2012, 235(6), 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, L.; Kongoli, R.; Baja, E. Evaluation of physico-chemical parameters of berry fruits marketed in Albania. In III. International Agricultural, Biological & Life Science Conference, Edirne, Turkey, 1-3 September 2021.

- Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zou, B.; Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, F.; Chen, S.; Chen, Q. Changes in quality properties and volatile compounds of different cultivars of green plum (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc.) during ripening. Eur Food Res Technol 2023, 249, 1199-1211. [CrossRef]

- Valero, D.; Serrano, M. Fruit ripening in Postharvest Biology and Technology for Preserving Fruit Quality, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla, USA, 2010. pp. 4–47. [CrossRef]

- Crisosto, C.H.; Crisosto, G.M.; Metheney, P. Consumer acceptance of ‘Brooks’ and ‘Bing’ cherries is mainly dependent on fruit SSC and visual skin color. Postharvest Biol Technol 2003, 28(1), 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołba, M.; Sokół-Ł˛etowska, A.; Kucharska, A.Z. Health Properties and Composition of Honeysuckle Berry Lonicera caerulea L. An Update on Recent Studies. Molecules 2020, 25, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horszwald, A.; Julien, H.; Andlauer, W. Characterisation of Aronia powders obtained by different drying processes. Food Chem 2013, 141, 2858–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhang, F.; Yang, H.; Qian, D-w.; Shang, E-x.; Wang, H-q.; Duan, J-a. Nutritional components characterization of goji berries from different regions in China. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2021, 195, 113859. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hoshino, Y. Elucidating the impact of ploidy level on biochemical content accumulation in haskap (Lonicera caerulea L. subsp. Edulis (Turcz. Ex Herder) Hultén) fruits: A comprehensive approach for fruit assessment. Sci Hortic 2024, 327, 112831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denev, P.; Kratchanova, M.; Petrova; I., Klisurova, D.; Georgiev, Y.; Ognyanov, M.; Yanakieva, I. Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.) Elliot) Fruits and Functional Drinks Differ Significantly in Their Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity. J Chem 2018, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, N. , Padwal, R., Field, C., Marks, S., Jacobs, R., Tonelli, M. A systematic review on the effect of sweeteners on glycemic response and clinically relevant outcomes. Metabolism, diet and disease 2011, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzanneau, N.; Weber, P.; Kosi´nska-Cagnazzo, A.; Andlauer,W. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Lonicera caerulea Berries: Comparison of Seven Cultivars over Three Harvesting Years. J Food Compos Anal 2018, 66, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimov, G.A.; Perova, I.B.; Eller, K.I.; Akimov, M.Y.; Sukhanova, A.M.; Rodionova, G.M.; Ramenskaya, G.V. Investigation of polyphenolic compounds in different varieties of black chokeberry Aronia melanocarpa. Molecules 2023, 28, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdylo, A.; Nowicka, P.; Babelewski, P. Phenolic and carotenoid profile of new goji cultivars and their anti-hyperglycemic, anti-aging and antioxidant properties. J Funct Foods 2018, 48, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, G.B.; Ghanem, A.; Brooks, M.S.L. Haskap berries (Lonicera caerulea L.) – a critical review of antioxidant capacity and health-related studies for potential value-added products. Food Bioprocess Tech 2014, 7, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.; Boehm, M.; Sekhon-Loodu, S.; Parmar, I.; Bors, B.; Jamieson, A. Anti-inflammatory activity of haskap cultivars is polyphenols-dependent. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1079–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for vitamin C. EFSA (2013) J. 11. [CrossRef]

- Zurek, N.; Pluta, S.; Seliga, L.; Lachowicz-Wisniewska, S.; Kapusta, I.T. Comparative evaluation of the phytochemical composition of fruits of ten haskap berry (Lonicera caerulea var. kamtschatica sevast.) cultivars grown in Poland. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczynski, B.; Gramza-Michalowska, A. Goji Berry (Lycium barbarum): Composition and health effects – A review. Pol J Food Nutr Sci 2016, 66, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, J.; Crozier, A.; Duthie, G.G. Potential health benefits of berries. Curr Nutr Food Sci 2005, 1(1), 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. Black chokeberry Aronia melanocarpa L.—A qualitative composition, phenolic profile and antioxidant potential. Molecules 2019, 24(20), 3710. [CrossRef]

- Ochmian, I.; Grajkowski, J.; Smolik, M. Comparison of some morphological features, quality and chemical content of four cultivars of Chokeberry fruits (Aronia melanocarpa). Not Bot Horti Agrobo 2012, 40(1), 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, E.R.; Ozden, T.Y.; Toplan, G.G.; Mat, A. Phenolic content and biological activities of Lycium barbarum L. (Solanaceae) fruits (Goji berries) cultivated in Konya, Turkey. Trop J pharmaceutical research 2018, 17(10), 2047-2053. [CrossRef]

- Vulic, J.J.; Canadanovic, J.M.; Cetkovic, G.S.; Djilas, S.M.; Saponjac, V.T.; Stajcic, S.S. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant properties of Goji fruits (Lycium barbarum L.) cultivated in Servia. J Am Coll Nutr 2016, 692-698. [CrossRef]

- Khattab, R.; Brooks, M. S-L.; Ghanem, A. Phenolic analyses of haskap berries (Lonicera caerulea L.): Spectrophotometry versus high performance liquid chromatography. Int J Food Prop 2016, 19, 1708–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Yu, X.; Badwal, T.S.; Xu, B. Comparative studies on phenolic profiles, antioxidant capacities and carotenoid contents of red goji berry (Lycium barbarum) and black goji berry (Lycium ruthenicum). Chem Cent J 2017, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Rocha, M.A.A.; Santos, L.M.N.B.F.; Brás, J.; Oliveira, J.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Blackberry anthocyanins: β-cyclodextrin fortification for thermal and gastrointestinal stabilization. Food Chem 2018, 245, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sip, S.; Sip, A.; Szulc, P.; Selwet, M.; Zarowski, M.; Czerny, B.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Exploring beneficial properties of Haskap Berry leaf compounds for gut health enhancement. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J.; Rop, O.; Micek, J.; Balla, S.; Szekeres, L.; … Kizek, R. Evaluation of polyphenolic profile and nutritional value of non-traditional fruit species in the Czech Republic – A comparative study. Molecules 2012, 17(12), 8968–8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senica, M.; Stampar, F.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. Blue honeysuckle (Lonicera cearulea L. Subs. Edulis) berry; a rich source of check for some nutrients and their differences among four different cultivars. Sci Hortic 2018, 238, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negreanu-Pirjol, B-S.; Oprea, O.C.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Roncea, F.N.; Prelipcean, A-M.; Craciunescu, O.; Isosageanu, A.; Artem, V.; Ranca, A.; Motelica, L.; Lepadatu, A-C.; Cosma, M.; Popoviciu, D.R. Health benefits of antioxidant bioactive compounds in the fruits and leaves of Lonicera caerulea L. and Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.) Elliot. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 951.

- Xiao, M.L.; Chen, G.D.; Zeng, F.F.; Qiu, R.; Shi, W.Q.; Lin, J.S.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.B.; Ling, W.H.; Chen, Y.M. Higher serum carotenoids associated with improvement of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: A prospective study. Eur J Nutr 2019, 58, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, R.; Jin, S.; Matoba, K.; Hoshino, Y. Novel production of β-cryptoxanthin in haskap (Lonicera caerulea subsp. edulis) hybrids: Improvement of carotenoid biosynthesis by interspecific hybridization. Sci Hortic 2023, 308, 111547.

- Craciunescu, O.; Seciu-Grama, A.M.; Mihai, E.; Utoiu, E.; Negreanu-Pirjol, T.; Lupu, C.E.; Artem, V.; Ranca, A.; Negreanu-Pirjol, B-S. The chemical profile, antioxidant, and anti-lipid droplet activity of fluid extracts from Romanian cultivars of haskap berries, bitter berries, and red grape pomace for the management of liver steatosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 16849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, J.; Hua, M.Z.; Singh, K.; Lu, X. Determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of harkap berries (Lonicera caerulea L.) by attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transformed-infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem 2025, 463, 141283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Moisture(%) | TSS (ºBrix) | pH | TA (%) | MI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aronia | ‘Nero’ | 77.71 ± 1.19bc | 17.65 ± 0.50c | 3.83 ± 0.04abc | 0.85 ± 0.07abc | 20.92 ± 1.43b |

| ‘Viking’ | 78.55 ± 0.36abc | 17.33 ± 0.37c | 3.80 ±0.02abc | 0.84 ± 0.04abc | 20.58 ± 0.93b | |

| ‘Galicjanka’ | 80.65 ± 0.81ab | 15.25 ± 0.30d | 3.77 ± 0.01bc | 0.96 ± 0.20ab | 16.31 ± 2.69b | |

| Haskap | ‘Blue Velvet’ | 86.45 ± 0.19a | 13.00 ± 0.35e | 3.23 ± 0.01c | 3.19 ± 0.07a | 4.07 ± 0.18c |

| Goji | ‘Turgidus’ | 75.71 ± 1.06c | 23.00 ± 0.96a | 5.56 ± 0.03a | 0.34 ± 0.02c | 68.31 ± 2.83a |

| ‘New Big’ | 77.98 ± 2.62abc | 21.30 ± 0.53b | 5.33 ± 0.01ab | 0.41 ± 0.02bc | 52.50 ± 1.17a |

| Aronia | Haskap | Goji | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivar | ‘Nero’ | ‘Viking’ | ‘Galicjanka’ | ‘Blue Velvet’ | ‘Turgidus’ | ‘New Big’ |

| Sugars (g 100g-1 fw) | ||||||

| Fructose | 2.62 ± 0.71b | 2.43 ± 0.57b | 2.91 ± 0.36b | 3.01 ± 0.46b | 6.18 ± 0.18a | 5.02 ± 0.53a |

| Glucose | 2.63 ± 0.38b | 1.96 ± 0.60b | 2.40 ± 0.18b | 2.44 ± 0.38b | 6.07 ± 0.18a | 5.34 ± 0.57a |

| Sorbitol | 6.37 ± 0.15b | 7.91 ± 0.79a | 6.08 ± 0.52b | 0.48 ± 0.12c | n.d. | 0.42 ± 0.06c |

| Total | 11.62 ± 0.96a | 12.30 ± 0.99a | 11.39 ± 1.02a | 5.93 ± 0.79b | 12.24 ± 0.37a | 10.79 ± 1.13a |

| Organic Acids (mg g—1 fw) | ||||||

| Oxalic | 2.15 ± 0.25a | 2.13 ± 0.34a | 2.22 ± 0.51a | 0.12 ± 0.01a | 0.09 ± 0.01a | 0.18 ± 0.01a |

| Citric | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 3.09 ± 0.27b | 11.8 ± 1.17a |

| Tartaric | 0.70 ± 0.05ab | 0.60 ± 0.02b | 0.60 ± 0.04b | 11.55 ± 0.34a | 3.19 ± 0.24ab | 3.82 ± 0.42ab |

| Malic | 11.84 ± 0.36ab | 10.55 ± 0.31ab | 10.91 ± 0.83ab | 17.38 ± 0.92a | 2.22 ± 0.12b | 1.47 ± 0.07b |

| Quinic | 5.43 ± 0.23b | 4.51 ± 0.28b | 4.58 ± 0.33b | 10.80 ± 0.81a | n.d. | n.d. |

| Ascorbic | 0.34 ± 0.02cd | 0.31 ± 0.02d | 0.29 ± 0.04d | 0.88 ± 0.05bc | 1.29 ± 0.09a | 1.01 ± 0.10ab |

| Succinic | 24.32 ± 0.65a | 19.93 ± 0.47a | 21.40 ± 1.07a | 1.80 ± 0.12b | 3.15 ± 0.18b | 3.37 ±0.31b |

| Fumaric | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.011 ± 0.002a | 0.003 ± 0.002b |

| Total | 44.78 ± 1.33a | 38.03 ± 0.85ab | 40.00 ± 2.80ab | 42.53 ± 2.18ab | 13.03 ± 0.88b | 21.64 ± 2.08ab |

| Species | Aronia | Haskap | Goji | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivars | ‘Nero’ | ‘Viking’ | ‘Galicjanka’ | ‘Blue Velvet’ | ‘Turgidus’ | ‘New Big’ |

| Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC) (mg GAE g-1 fw) | 13.94 ± 1.04a | 11.75 ± 2.56ab | 13.82 ± 2.09ab | 6.94 ± 0.20ab | 3.59 ± 0.82b | 4.59 ± 1.61ab |

| Individual Phenolic Compounds(mg g-1 fw) | ||||||

| Chlorogenic acid (AClo) | 0.294 ± 0.019b | 0.260 ± 0.024b | 0.198 ± 0.003c | n.d. | 0.165 ± 0.007c | 0.371 ± 0.020a |

| p-coumaroylquinic acid (ApC) | 0.053 ± 0.025a | 0.014 ± 0.003ab | 0.012 ± 0.001ab | n.d. | 0.003 ± 0.001b | 0.007 ± 0.001ab |

| p-coumaric acid (ApCou) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.0021 ±0.0003a | 0.0021±0.0002a |

| t-ferulic acid (t-Fer) | 0.0032 ± 0.007a | 0.0030 ±0.0006a | 0.0043 ±0.0005a | 0.0099 ±0.0021a | 0.0030 ±0.0001a | 0.0056 ±0.004a |

| Cyanidin-3-glucoside (C3G) | 1.808 ± 0.067a | 1.799 ± 0.228a | 1.647 ± 0.158a | 0.004 ± 0.001b | n.d. | n.d. |

| Cyanidin-3-rutinoside (C3R) | 1.16 ± 0.06b | 1.28 ± 0.16b | 1.30 ± 0.13b | 4.22 ± 0.75a | n.d. | n.d. |

| Peonidin-3-rutinoside (P3R) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.27 ± 0.12 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Catechin (Cat) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.030 ± 0.009a | 0.037 ± 0.005a | 0.066 ± 0.002a |

| Epicatechin (Ecat) | 0.044 ± 0.002ab | 0.037 ± 0.008ab | 0.029 ± 0.003b | 0.074 ± 0.13a | n.d. | n.d. |

| Procyanidin B1 (PB1) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.021 ± 0.005 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Procyanidin B2 (PB2) | 0.019 ± 0.002a | 0.015 ± 0.004a | 0.014 ± 0.003a | 0.020 ± 0.003a | n.d. | n.d. |

| Isoharmentin-3-rutenoside (I3R) | 0.006 ± 0.001a | 0.004 ± 0.001a | 0.004 ± 0.001a | 0.004 ± 0.001a | n.d. | 0.004 ± 0.001a |

| Kaempferol-3-rutinoside (K3R) | 0.008 ± 0.001a | 0.006 ± 0.001a | 0.007 ± 0.001a | 0.003 ± 0.001a | n.d. | n.d. |

| Quercetin-3-glucoside (Q3G) | 0.062 ± 0.001a | 0.051 ± 0.005a | 0.054 ± 0.004a | 0.069 ± 0.014a | n.d. | n.d. |

| Quercetin-3-rutinoside (Q3R) | 0.088 ± 0.005ab | 0.072 ± 0.010ab | 0.087 ± 0.006ab | 0.160 ± 0.039a | 0.028 ± 0.003ab | 0.017 ± 0.002b |

| Total anthocyanins (TA)(A g-1 fw) | 111.96 ± 12.21b | 120.60 ± 26.12b | 123.13 ± 30.46b | 196.58 ± 17.96a | n.d. | n.d. |

| Total carotenoid contents (TCC) (mg Zea g-1 fw) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.27±0.03a | 0.37±0.05a |

| Individual carotenoids(μg g-1 fw) | ||||||

| Capsanthin (Cap) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.45 ± 0.12a | 2.53 ± 0.70a |

| Zeaxanthin (Zea) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 39.34 ± 14.84a | 85.70 ± 31.90a |

| Cryptoxanthin (Crp) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.84 ± 0.23a | 1.06 ± 0.27a |

| α-carotene ( -Car) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.40 ± 0.10a | 0.37 ± 0.09a |

| β-carotene ( -Car) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.12 ± 0.38a | 1.79 ± 0.52a |

| Antioxidant activity (AAT) (g Trolox kg-1 fw) | 15.93 ± 1.23a | 12.00 ± 2.45ab | 13.33 ± 1.03ab | 6.70 ± 0.47ab | 5.33 ± 0.24b | 5.69 ± 0.17ab |

| AAT | TPC | TA | TCC | Cap | Zea | Crp | -Car | -Car | AClo | ApC | ApCou | t-Fer | C3G | C3R | P3R | Cat | Ecat | PB1 | PB2 | I3R | K3R | Q3G | Q3R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAT | 1* | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| TPC | 0,96* | 1* | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| TA | 0,47* | 0,58* | 1* | |||||||||||||||||||||

| TCC | -0,71* | -0,77* | -0,86* | 1* | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cap | -0,67* | -0,72* | -0,82* | 0,98* | 1* | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zea | -0,62* | -0,65* | -0,76* | 0,92* | 0,96* | 1* | ||||||||||||||||||

| Crp | -0,69* | -0,74* | -0,84* | 0,95* | 0,94* | 0,95* | 1* | |||||||||||||||||

| -Car | -0,70* | -0,76* | -0,85* | 0,93* | 0,89* | 0,89* | 0,98* | 1* | ||||||||||||||||

| -Car | -0,67* | -0,71* | -0,81* | 0,94* | 0,94* | 0,97* | 0,99* | 0,95* | 1* | |||||||||||||||

| AClo | 0,29 | 0,18 | -0,49* | 0,29 | 0,33 | 0,36 | 0,27 | 0,19 | 0,32 | 1* | ||||||||||||||

| ApC | 0,68* | 0,52* | 0,13 | -0,32 | -0,30 | -0,28 | -0,32 | -0,33 | -0,30 | 0,47* | 1* | |||||||||||||

| ApCou | -0,72* | -0,79* | -0,87* | 0,97* | 0,92* | 0,86* | 0,96* | 0,98* | 0,92* | 0,22 | -0,34 | 1* | ||||||||||||

| t-Fer | -0,43* | -0,32 | 0,33 | 0,02 | 0,05 | 0,09 | 0,01 | -0,03 | 0,05 | -0,62* | -0,39* | -0,03 | 1* | |||||||||||

| C3G | 0,91* | 0,89* | 0,41* | -0,73* | -0,69* | -0,65* | -0,72* | -0,73* | -0,69* | 0,35 | 0,53* | -0,74* | -0,55* | 1* | ||||||||||

| C3R | 0,01 | 0,12 | 0,80* | -0,58* | -0,55* | -0,52* | -0,57* | -0,58* | -0,55* | -0,74* | -0,12 | -0,59* | 0,76* | -0,06 | 1* | |||||||||

| P3R | -0,38 | -0,29 | 0,53* | -0,18 | -0,18 | -0,16 | -0,18 | -0,18 | -0,17 | -0,79* | -0,31 | -0,19 | 0,89* | -0,49* | 0,89* | 1* | ||||||||

| Cat | -0,83* | -0,84* | -0,61* | 0,89* | 0,89* | 0,87* | 0,88* | 0,83* | 0,88* | 0,02 | -0,43* | 0,85* | 0,43* | -0,90* | -0,18 | 0,23 | 1* | |||||||

| Ecat | 0,37 | 0,42* | 0,87* | -0,78* | -0,74* | -0,69* | -0,77* | -0,77* | -0,74* | -0,51* | 0,23 | -0,79* | 0,49* | 0,29 | 0,91* | 0,67* | -0,46* | 1* | ||||||

| PB1 | -0,38 | -0,28 | 0,51* | -0,18 | -0,17 | -0,16 | -0,18 | -0,18 | -0,17 | -0,78* | -0,31 | -0,19 | 0,91* | -0,48* | 0,89* | 0,99* | 0,24 | 0,68* | 1* | |||||

| PB2 | 0,68* | 0,71* | 0,82* | -0,90* | -0,86* | -0,80* | -0,88* | -0,89* | -0,86* | -0,26 | 0,43* | -0,91* | 0,16 | 0,63* | 0,68* | 0,32 | -0,72* | 0,91* | 0,33 | 1* | ||||

| I3R | 0,66* | 0,61* | 0,48* | -0,56* | -0,47* | -0,39* | -0,57* | -0,66* | -0,49* | 0,33 | 0,67* | -0,65* | 0,04 | 0,59* | 0,31 | 0,01 | -0,44* | 0,58* | 0,04 | 0,71* | 1* | |||

| K3R | 0,88* | 0,89* | 0,56* | -0,86* | -0,82* | -0,76* | -0,84* | -0,85* | -0,81* | 0,14 | 0,53* | -0,87* | -0,35 | 0,92* | 0,21 | -0,22 | -0,91* | 0,53* | -0,22 | 0,81* | 0,70* | 1* | ||

| Q3G | 0,66* | 0,71* | 0,88* | -0,94* | -0,89* | -0,84* | -0,92* | -0,93* | -0,89* | -0,30 | 0,38 | -0,95* | 0,21 | 0,63* | 0,72* | 0,35 | -0,75* | 0,90* | 0,36 | 0,97* | 0,71* | 0,80* | 1* | |

| Q3R | 0,27 | 0,35 | 0,84* | -0,73* | -0,71* | -0,66* | -0,71* | -0,71* | -0,67* | -0,66* | 0,07 | -0,73* | 0,63* | 0,18 | 0,95* | 0,74* | -0,39* | 0,95* | 0,76* | 0,82* | 0,46* | 0,42* | 0,86* | 1* |

| Component | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||

| Positive | ApCou | 0.988 | Tartaric Acid | 0,977 |

| TCC | 0.977 | P3R | 0.968 | |

| -Car | 0.975 | PB1 | 0.963 | |

| Crp | 0.969 | t-Fer | 0.914 | |

| pH | 0.967 | |||

| Glucose | 0.954 | |||

| Cap | 0.938 | |||

| β-Car | 0.938 | |||

| Fructose | 0.921 | |||

| Negative | Q3R | 0.975 | AClo | 0.799 |

| PB2 | 0.947 | Succinic Acid | 0.703 | |

| Malic Acid | 0.915 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).