1. Introduction

It is well known that climate change is expected to have a profound impact on the species’ distribution. Such as the temperature since the Late Miocene experienced continuously decline [

1], which led to dramatic biodiversity changes [

2,

3]. The temperature changes resulted in the expansion and/or contraction of plants and the fragmented distribution pattern of certain species [

4,

5]. The evergreen broad-leaved forests (EBLFs) largely occurs in East Asia under a monsoon climate with obvious seasonality, which comprise the main portion of the global subtropical biodiversity [

6,

7]. The East Asian EBLFs harbor numerous relicts or endemic species [

6,

8], and these forests are widely regarded as biodiversity museums or refugia [

9]. Understanding climate change and species distribution range is of great significance the preservation of threatened and endemic species in this biome.

Sinojackia Hu (Styracaceae) contains five species, i.e.,

S. xylocarpa Hu,

S. sarcocarpa L.Q. Luo,

S. rehderiana Hu,

S. heneyi (Dummer) Merrill,

S. dolichocarpa C.J. Qi [

10]. Recently, there are three new species (

S. huangmeiensis J.W. Ge & X.H. Yao,

S. microcarpa C.T. Chen & G.Y. Li,

S. oblongicarpa C.T. Chen & T.R. Cao) and one new subspecies (

S. xylocarpa var.

leshanensis L.Q. Luo) have been established [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Totally, there are eight species and one subspecies recorded in

Sinojackia. This genus is endemic distributed in Central, Southern and Southwest China [

10,

15]. All

Sinojackia species have been listed in National Key Protected Wild Plants of China as Grade II (2021) owing to their small population sizes and poor recruitment within populations. Especially,

S.

xylocarpa is assessed as Vulnerable (VU) in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (

www.iucnredlist.org/species/32374/9701730). Furthermore,

Sinojackia species have high gardening plants values, because they have white fragrant flowers and unique weighing hammer-like fruits [

16]. Therefore, assessing the distribution status of

Sinojackia has important significance for the conservation of

Sinojackia, especially considering in the future climate scenarios.

Until now, there are many researches about phylogeny and biogeography have been conducted, and all resulted supported that

Sinojackia was monophyletic with moderate to high supporting values [

17,

18,

19]. Such as Fritsch et al. [

17] reconstructed the phylogeny of the Styracaceae based on three DNA markers (

trnL-

L-

F,

rbcL, ITS) and 47 morphological characters, and showed that

Changiostyrax dolichocarpa (previously

S. dolichocarpa) did not cluster with

Sinojackia. Yao et al. [

18] combined ITS,

psbA–

trnH and microsatellite data to infer a phylogeny of

Sinojackia, and supported

S. dolichocarpa as a member of

Changiostyrax . However, the results of the two studies have not obtain strong supporting values for the monophyly of

Sinojackia. Recently, Jian et al. [

19] well supported the genus

Sinojackia was a monophyletic group and divided it into two clades . They also showed that

Sinojackia originated in Central-Southeast China during the early Miocene and glacial-interglacial interactions with the monsoon climate may provide favorable expansion conditions for

Sinojackia. However, there is few studies for predicting the impact of future climate change on

Sinojackia species’ distributions.

Ecological niche modeling is widely used to predict the potential distribution area of species under current and future climate scenarios. For instance, Xiao et al. [

20] identified the pivotal role of precipitation for affecting the distribution of

Tsuga, and highlighted the conservation of natural

Tsuga distributions in East Asia and North America. Qiu et al. [

21] revealed that the geographical distribution of the three

Bergenia (Saxifragaceae) species was primarily influenced by precipitation and elevation. By 2090, the three

Bergenia species were expected to show contrasting range changes, and they were projected to shift their ranges to higher elevations in response to temperature increases. Consequently, these studies provide valuable information for biodiversity conservation and management.

In this study, we applied the MaxEnt model to predict the potential distribution of Sinojackia under current and future climate change scenarios. Specifically, the objectives are as follows: (1) to explore the niche evolution of Sinojackia and the critical environmental factors; (2) to assess the effects of climate change and human footprint on the geographic range changes of Sinojackia from LGM and the future; and (3) to propose the conservation strategy of Sinojackia. This study will provide valuable insights for conservation of the endemic plants under climate changes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Taxon Sampling

A total of 14 individuals represented six Sinojackia species were sampled, including three individuals of S. oblongicarpa, three individuals of S. xylocarpa, three individuals of S. sarcocarpa and three individuals of S. microcarpa. There are seven species of Styraxaceae were selected as outgroups, included Changiostyrax dolichocarpus, Halesia diptera, Melliodendron xylocarpum, Perkinsiodendron macgregorii, Pterostyrax hispidus, Rehderodendron macrocarpum and Styrax wuyuanensis. All plastomes sequences were downloaded from GenBank.

2.2. Phylogeny Reconstruction

Sequence alignments were performed using MAFFT v7 and manually adjusted in BioEdit v7.0 [

22,

23]. The phylogenetic relationships were inferred based on whole plastomes by maximum likelihood (ML). The best nucleotide substitution model was chosen using jModelTest2 under the Akaike information criterion (AIC) [

24]. ML analyses were conducted in RAxML v8.2.12 with a rapid bootstrap analysis (BS; 1000 replicates) and searching for the best-scoring tree simultaneously [

25].

2.3. Divergence Time Estimation

Divergence times were estimated under relaxed lognormal clock model in BEAST v2.6.0 based on the whole plastome matrix [

26]. Two fossils were applied: (1) the fossil

Styrax elegans (56 - 47.8 Ma) was set as the root age with uniform distribution [

27], and (2) the fossil

Halesia reticulata (37.2 - 33.9 Ma) were set to the stem age of

Halesia with uniform distribution [

28]. We ran MCMC searches for 100 million generations and sampled every 5000 generations. After assessing the convergence using Tracer v.1.7 [

29], the maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree was calculated by TreeAnnotator v.2.6.0 [

30].

2.4. Occurrence Data Collection and Niche Evolution Analyses

The occurrence records of

Sinojackia were collected from Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF,

https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.pws456, assessed at 2024-5-20), the Chinese Virtual Herbarium (CVH,

http://www.cvh.ac.cn/) and the published species records [

11,

12,

13,

14]. R package “CoordinateCleaner” were used to remove coordinates with uncertainty >10 km, with equal longitude and latitude values, and those near biodiversity institutions and within seas [

31]. Totally, there are 22 cleaned coordinates obtained (

Table S1).

Twenty-one environmental factors were compiled for each record. Nineteen bioclimatic variables and elevation layers were downloaded from WorldClim database v.2.1 (

https://www.worldclim.org/). The potential evapotranspiration (PET) was extracted from the CGIAR-CSI website (

https://www.cgiarcsi.org). The 21 environmental variables were analyzed using phylogenetic principal component analysis (PPCA) implemented in R package “phytools” [

32]. Based on the first axis of the PPCA results, a run of 10 million generations for the 21 environmental variables was performed in BAMM and visualized in R package “BAMMtools” [

33].

2.5. Potential Distribution Areas Prediction

On the clean occurrence records of

Sinojackia, we furtherly only reserved one occurrence record within 5 km to reduce the spatial autocorrelation. Finally, 15 eligible occurrences were used in species distribution models (SDM) analyses (

Table S2). Nineteen bioclimatic variables of future climate (2090: average of 2081-2100) were download from WorldClim database v.2.1 (

https://www.worldclim.org/). We chose the three climate scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5 and SSP4-8.5) for subsequent niche modeling. Only bioclimatic variables with Pearson’s |r| < 0.8 in each period were considered in the following analyses, and the relative importances of them were assessed using the jackknife method in MaxEnt v3.4.1 (

https://biodiversityinformatics.amnh.org/open_source/maxent/). We calculated the potential distribution areas across the future after model building, and classified the results of SDM to four ranks (i.e., high suitable, medium suitable, low suitable, and unsuitable) using the “Reclassify tool” in MaxEnt. Finally, we calculated the area changes in the past and future compared with current potential distribution area using SDM toolbox v2.4 [

34].

3. Results and Discussions

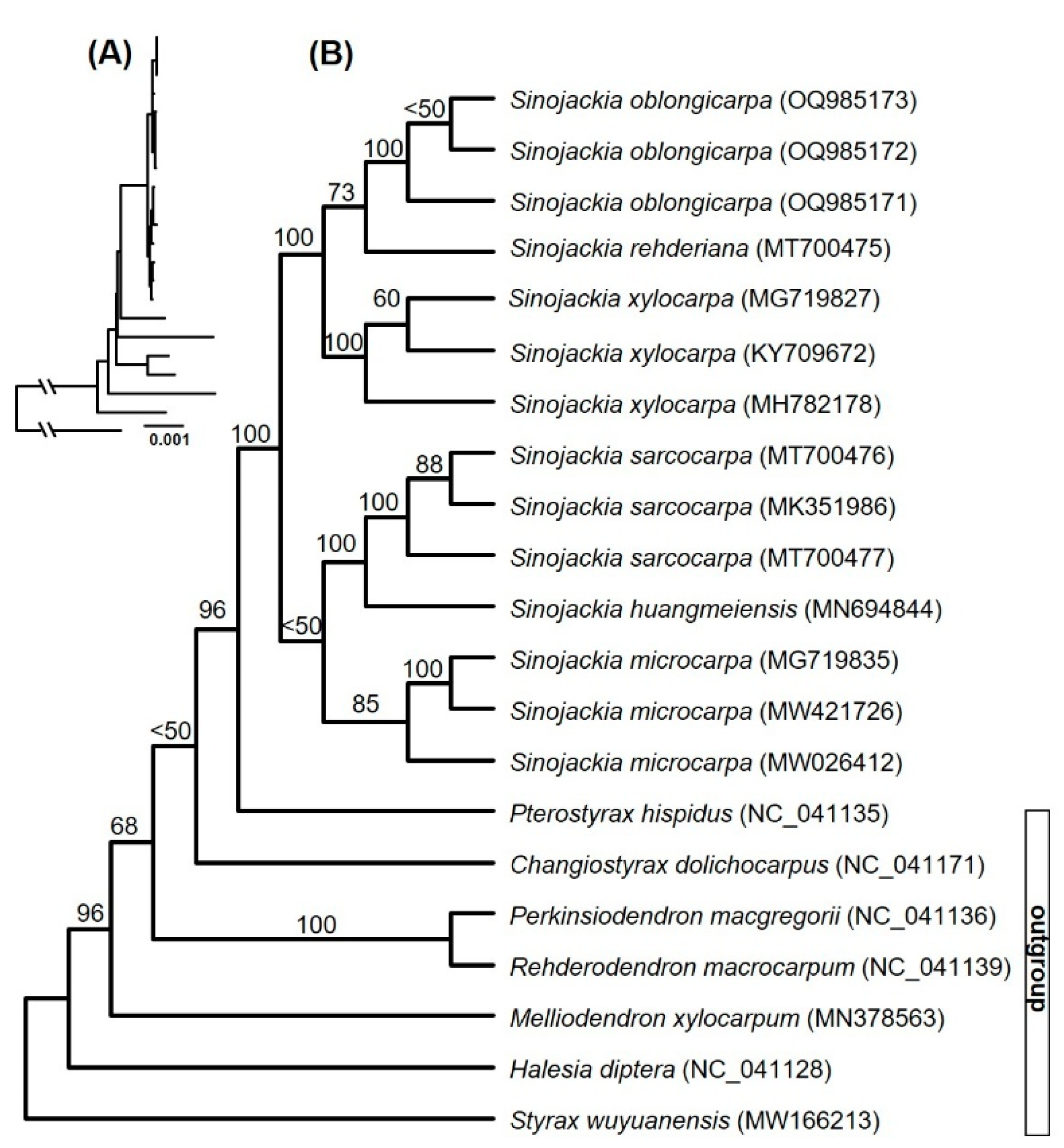

3.1. Phylogeny of Sinojackia

The maximum likelihood phylogeny based on the whole plastome data has supported the

Sinojackia is a monophyly with highest supporting values (ML-BS = 100%,

Figure 1). All species of

Sinojackia was supported as a monophyletic with moderate to highest supporting values and the

Sinojackia was divided into two subclades (

Figure 1). One subclade contained

S. microcarpa,

S. sarocarpa, and

S. huangmeiensis with low supporting values (ML-BS < 50%), and the latter two species grouped together with highest supporting values (ML-BS = 100%). Another subclade also contained three species,

S. oblongicarpa,

S. rehderiana and

S. xylocarpa with highest supporting values (ML-BS = 100%), and the former two species clustered together with moderate supporting values (ML-BS = 73%). Furthermore, our results supported the previous studies that

Changiostyrax dolichocarpus was not a member of

Sinojackia [

17,

18,

19].

Previous studies based on several DNA markers did not resolve the phylogenetic relationships within the genus

Sinojackia [

17,

18]. Our phylogenetic results have almost clarified the relationships of

Sinojackia, which were similar with that of Jian et al. [

19], with the different in the supporting values of a few nodes. However, the genus

Sinojackia may experience rapid radiation during its evolutionary history, which implied that it needs more nuclear data to fully resolve their close phylogenetic relationships.

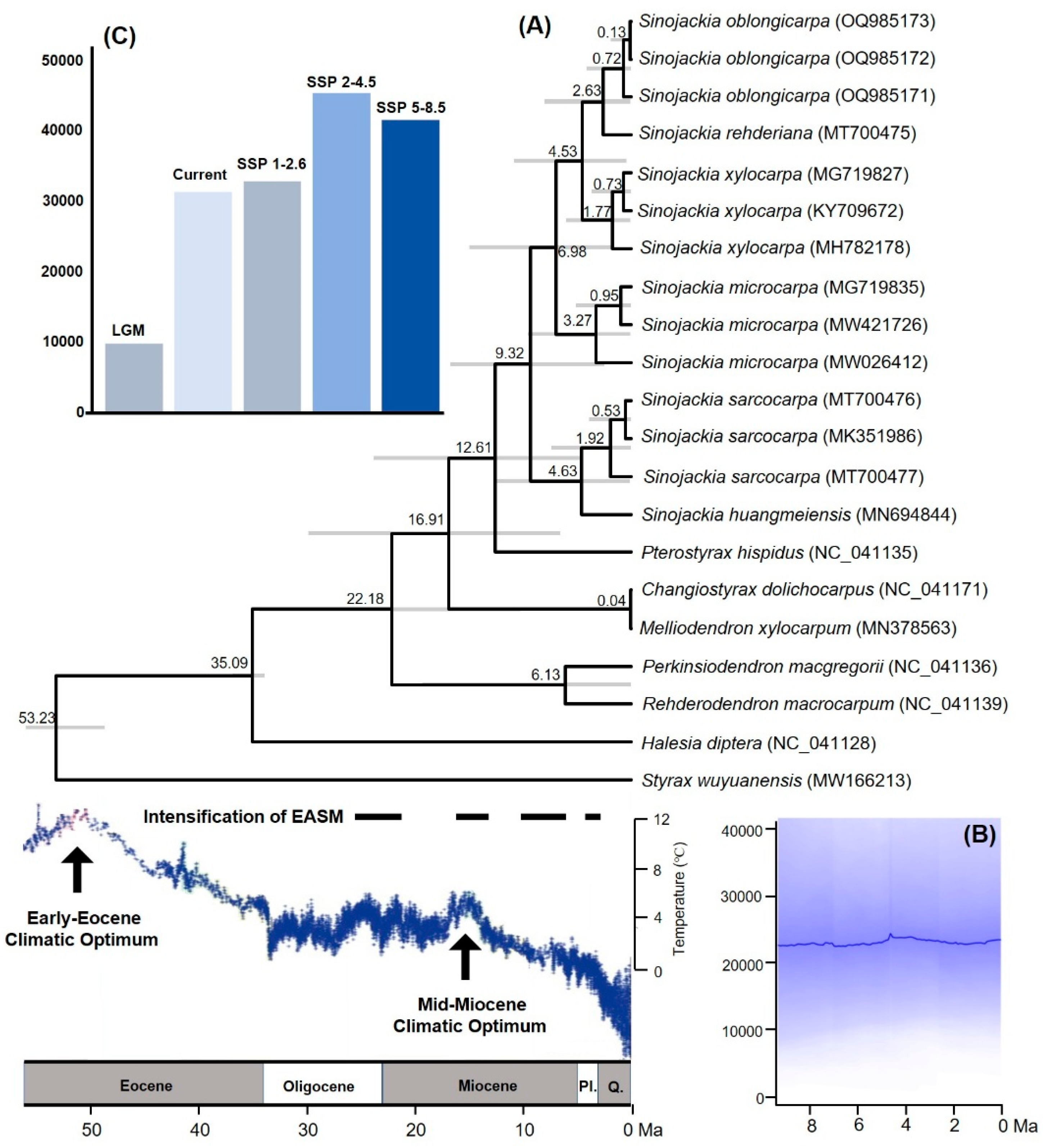

3.2. Divergence Time and Niche Evolution of Sinojackia

Our dated-phylogeny results showed that the genus

Sinojackia originated at 12.61 Ma (95% HPD: 4.43-23.82), and diversified at 9.32 Ma (95% HPD: 2.51-18.68) (

Figure 2A). These results were slight latter than the result of Jian et al. [

19], and this difference maybe contributed to different calibration strategies. Furthermore, the six species diverged since the late Miocene (

Figure 2A), which is consistent with Jian et al. (4.69-9.44 Ma) [

19].

For the genus

Sinojackia, the niche PPCA result showed that PC1 had a higher contribution from Aridity index (AI), temperature seasonality (Bio4), Minimum temperature of coldest month (Bio6), and elevation (

Table 1). The rate of niche evolution remained stable since the origin of this genus, and it experienced a slow increase toward the present (

Figure 2B). The genus

Sinojackia inhabited in the Asian subtropical EBLFs [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Our ecological niche modeling analyses indicated that AI is the most important climatic variable for the niche evolution of

Sinojackia (

Table 1). The intensification of the Asian monsoon climate at Late Miocene and Pliocene brought enough precipitation, which provide a suitable and stable environment for the divergence of

Sinojackia. From 6 Ma onward, largescale ice sheets in the Northern Hemisphere and the Icehouse state occurred [

35], which has seriously affected the geographical distribution of plant lineages in the Asian EBLFs Hai et al. [

36]. It is undoubtably that frost is the key constraint for evergreen broad-leaved plants, as shown by our results, which indicate that the temperature seasonality and minimum temperature of coldest month is an important influential climatic variable for the

Sinojackia species (

Table 1). Meanwhile, a decrease in precipitation occurred in East Asia since the Pliocene [

37]. Though low temperature and decreased precipitation might have progressively deteriorated East Asian subtropical EBLFs since 6 Ma, the

Sinojackia is shrubs or trees and is not the dominant species in EBLFs. We therefore suggested that the dominant trees in Asian subtropical EBLFs might provide a suitable niche for the development of

Sinojackia.

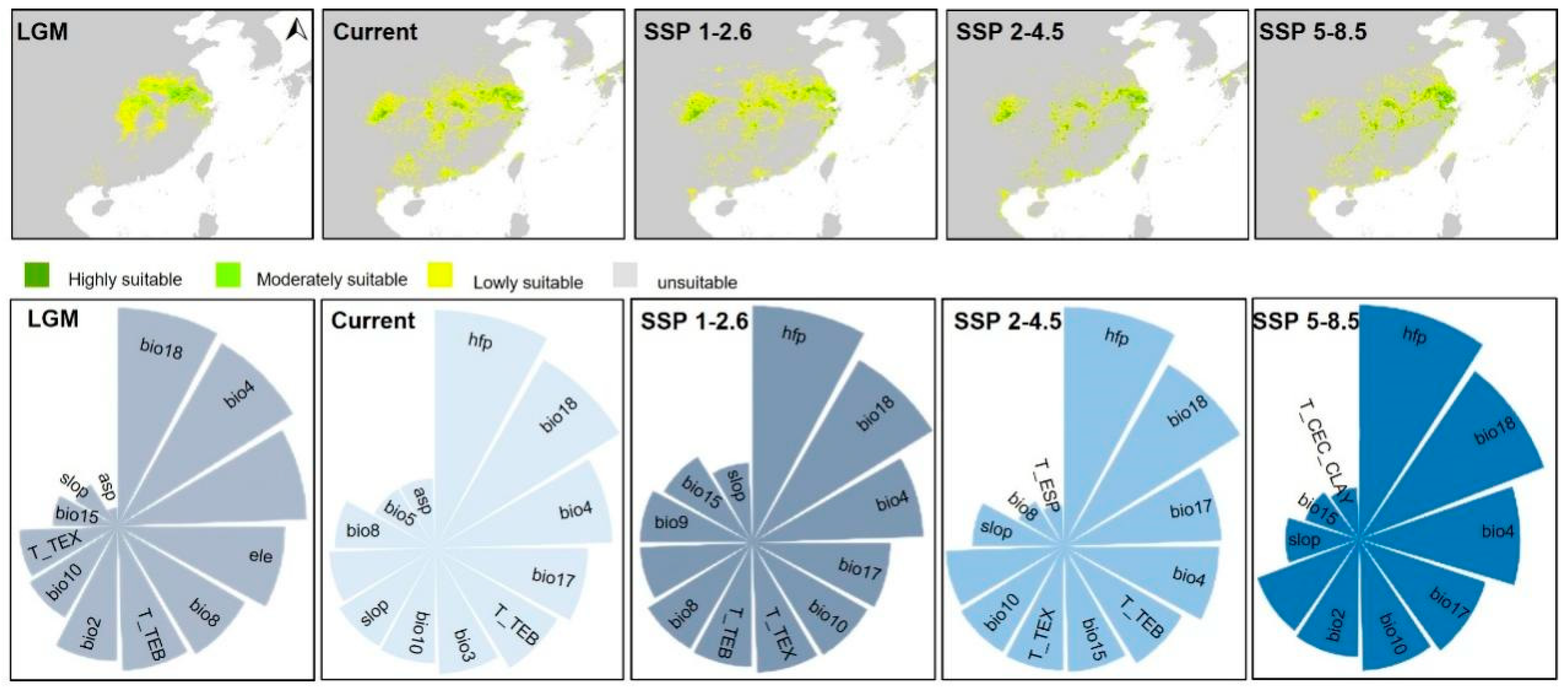

3.3. Potential Distribution and Its Conservation

The AUC value for

Sinojackia in the MaxEnt model was 0.999, indicating high predictive performance. Besides, the highly suitable of the predicted near-current distributions were generally good representations of the observed distributions of

Sinojackia (

Figure 3). Our result of MaxEnt model showed that the distribution of

Sinojackia species is mainly impacted by precipitation of warmest quarter (Bio18) and temperature seasonality (Bio4) during the LGM (

Figure 3). The ancestral suitable geographical ranges of

Sinojackia have changed since LGM under the MaxEnt model. Compared the near-current distribution areas, the suitable distribution range of

Sinojackia during LGM was constraint in eastern Asia. It is widely acknowledged that the precipitation and temperature also had been declined dramatically during LGM [

38,

39]. In Asia, the uplift of Himalayas and Hengduan Mountains, the Chinese flora has not been influenced extremely [

40]. Lu et al. [

10] investigated the spatio-temporal divergence patterns of the Chinese flora and indicated that 66% of the angiosperm genera in China did not originate until early in the Miocene epoch, and proposed that eastern China has served as both a museum and a cradle for woody genera. Therefore, we deemed that

Sinojackia have been relict in eastern Asia during LGM after it originated at middle Miocene.

Compared to the distribution range during LGM, the current distribution areas of

Sinojackia have expanded with the relative higher temperature and more precipitation. Under the three climate scenarios in the future (2081-2100), the distribution range of

Sinojackia became more fragments (

Figure 3), but the areas of highly suitable range were expanded (

Figure 2C), with the highest suitable range under SSP 2-4.5. In the current periods and the three future climate scenarios (SSP 1-2.6, SSP 2-4.5 and SSP 5-8.5), human footprint (Hfp) is the most variable that influencing the distribution, and bio18 is also a main variable climatic factor (

Figure 3). Previous study indicated that some narrow-ranging species may be positively influenced by Hfp [

41], although species with small ranges are regarded as more vulnerable to extinction [

42,

43].

The human footprint implies human population pressure, land use and so on [

44]. There are two conflicting aspects related to the roles of the human footprint in the species’ suitable habitat. Most of studies showed that the negative relation between species conservation and human footprint, because the human activities such as land logging and livestock grazing could threaten the species’ suitable habitats [

45,

46,

47]. However, Liu et al. [

48] showed a positive relationship between human population density and the density of scattered trees in China , which supported that the species conservation may benefit from human activities [

46,

48,

49]. Our results also showed that under the human activities in 2081-2100, the highly suitable distribution of

Sinojackia would expand. Therefore, we deemed that the positive human footprint on the habitat suitability of

Sinojackia may be due to the ecosystem conservation and protection management. Besides, all

Sinojackia species are listed as protected wild species in China due to its narrow distribution and high gardening values. Until now, more than 12 botanical gardens in the world transplant the

Sinojackia species as

ex situ conservation, and we emphasize that it is necessary to conduct more comprehensive field surveys of

Sinojackia species for

in situ conservation.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we reconstructed the phylogeny, estimated the divergence time, conducted niche evolution and predicted the potential habitat area of Sinojackia, a Chinese endemic genus, and the main results showed that: (1) The monophyly of Sinojackia was well supported based on the whole plastomes, and the interspecific relationships among the genus have been nearly resolved. (2) Sinojackia originated at middle Miocene and diverged at the late Miocene. (3) Aridity index had a highest contribution for the niche of Sinojackia, and the niche evolution rate experienced a slow increase toward the present. (4) The main environmental variables affecting the distribution of Sinojackia is precipitation of warmest quarter in LGM, while human footprint is main variables in current and 2081-2100. (5) Compared to the highly suitable distribution area in LGM, the genus Sinojackia would expand during near-current and the 2081-2100, and human activities are positive related to this species conservation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

M.F.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, original draft preparation; J.-S.Z.: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, funding acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Funding of Liaoning Key Laboratory of Development [LZ202301], and Science Funding of Anshan Normal University [No.18kyxm007].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests.

References

- Zachos, J.C.; Dickens, G.R.; Zeebe, R.E. An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature 2008, 451, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.B. Quaternary history of deciduous forests of eastern North America and Europe. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1983, 70, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, G. The genetic legacy of the Quaternary ice ages. Nature 2000, 405, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandel, B.; Arge, L.; Dalsgaard, B.; Davies, R.G.; Gaston, K.J.; Sutherland, W.J.; Svenning, J.C. The influence of Late Quaternary climate-change velocity on species endemism. Science 2011, 334, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.L.; Bae, C.J.; Zhang, Z.S. Cenozoic climate change in eastern Asia: Part I. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 510, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.C.; Da, L.J. Evergreen broad-leaved forest of East Asia. In: Box EO, ed. Vegetation structure and function at multiple spatial, temporal and conceptual scales. Berlin, Germany, 2016, pp. 101–128.

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.C.; Liu, B.; Lu, L.M.; Sauquet, H.; Li, D.Z.; Chen, Z.D. Meta-analysis provides insights into the origin and evolution of East Asian evergreen broad-leaved forests. New Phytologist 2024, 242, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Q. Evergreen broad-leaved forests. In: Tang, C.Q. ed. The subtropical vegetation of southwestern China: plant distribution, diversity and ecology. Utrecht: Springer. 2015, pp. 60–105.

- Lu, L.M.; Mao, L.F.; Yang, T.; Ye, J.F.; Liu, B.; et al. Evolutionary history of the angiosperm flora of China. Nature 2018, 554, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.M.; Grimes, J. Sinojackia. In: Wu, C.Y., Raven, P., Eds. Flora of China (Volume 15); Science Press/Missouri Botanical Garden Press: Beijing, China/St. Louis, 1996, pp. 267–269.

- Chen, T.; Li, G. A new species of Sinojackia Hu (Styracaceae) from Zhejiang, East China. Novon 1997, 7, 350. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Cao, T. A new species of Sinojackia Hu (Styracaceae) from Hunan, South Central China. Edinburgh J. Bot. 1998, 55, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L. Sinojackia xylocarpa var. leshanensis (Styracaceae), a new variety from Sichuan, China. Bull. Bot. Res. 2005, 25, 260–261. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.H.; Ye, Q.G.; Ge, J.W.; Kang, M.; Huang, H.W. A new species of Sinojackia (Styracaceae) from Hubei, Central China. Novon 2007, 17, 138–140. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.H.; Ye, Q.G.; Kang, M.; Huang, H.W. Geographic distribution and current status of the endangered genera Sinojackia and Changiostyrax. Biodivers. Sci. 2005, 13, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Tang, R.; Chen, C. Cultivation technology and application of Sinojackia. Contemp. Hortic. 2015, 294, 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, P.W.; Morton, C.M.; Chen, T.; Meldrum, C. Phylogeny and biogeography of the Styraceae. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2001, 162(6 Suppl.), S95–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Ye, Q.; Fritsch, P.W.; Cruz, B.C.; Huang, H. Phylogeny of Sinojackia (Styracaceae) based on DNA sequence and microsatellite data: implications for taxonomy and conservation. Ann. Bot. 2008, 101, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, Q. , Miao, Y.M. Plastid phylogenetics, biogeography, and character evolution of the Chinese endemic genus Sinojackia Hu. Diversity 2024, 165, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.M.; Li, S.F.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.J.; Wu, M.X.; Karim, R.; Deng, W.Y.; Su, T. Influence of climate factors on the global dynamic distribution of Tsuga (Pinaceae). Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Fu, Q.L.; Jacquemyn, H.; Burgess, K.S.; Cheng, J.J.; Mo, Z.Q.; Tang, X.D.; Yang, B.Y.; Tan, S.L. Contrasting range changes of Bergenia (Saxifragaceae) species under future climate change in the Himalaya and Hengduan Mountains Region. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 1927–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acid Symp. Series 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods. 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouckaert, R.; Heled, J.; Kühnert, D.; Vaughan, T.; Wu, C.H.; Xie, D.; Suchard, M.A.; Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, M.E.J. The Lower Tertiary floras of Southern England. II. Flora of the Pipe-Clay Series of Dorset (Lower Bagshot); British Museum (Natural History): London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- MacGinitie, H.D. Fossil plants of the Florissant Beds, Colorado; Carnegie Institution of Washington: Washington, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, A.; Silvestro, D.; Andermann, T.; Azevedo, J.; Ritter, C.D.; Edler, D.; Farooq, H.; Herdean, A.; Ariza, M.; Scharn, R.; Svantesson, S.; Wengström, N.; Zizka, V.; Antonelli, A. CoordinateCleaner: standardized cleaning of occurrence records from biological collection databases. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, L.J. Phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabosky, D.L.; Grundler, M.; Anderson, C.; Title, P.; Shi, J.J.; Brown, J.W.; Huang, H.; Larson, J.G. BAMMtools: an R package for the analysis of evolutionary dynamics on phylogenetic trees. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L. SDM toolbox: a python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhold, T.; Marwan, N.; Drury, A.J.; Liebrand, D.; Agnini, C.; Anagnostou, E.; Barnet, J.S.K.; Bohaty, S.M.; Vleeschouwer, D.D.; Florindo, F. An astronomically dated record of Earth’s climate and its predictability over the last 66 million years. Science 2020, 369, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, L.; Li, X.Q.; Zhang, J.B.; Xiang, X.G.; Li, R.Q.; Jabbour, F.; Ortiz, R.d.C.; Lu, A.M.; Chen, Z.D.; Wang, W. Assembly dynamics of East Asian subtropical evergreen broadleaved forests: new insights from the dominant Fagaceae trees. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, A.; Lunt, D.J.; Robinson, S.A.; Valdes, P.J.; Roberts, W.H.G.; Clift, P.D.; Markwick, P.; Su, T.; Wrobel, N.; Bragg, F. Past East Asian monsoon evolution controlled by paleogeography, not CO2. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mix, A. C.; Bard, E.; Schneider, R. Environmental processes of the ice age: land, oceans, glaciers (EPILOG). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2001, 20, 627–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachos, J.C.; Dickens, G.R.; Zeebe, R.E. An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature 2008, 451, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.S.; Deng, T.; Zhuo, Z.; Sun, H. Is the East Asian flora ancient or not? Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.Y.; Wang, T.J.; Groenb, T.A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Yang, X.F.; Ma, K.P.; Wu, Z.F. Climate and land use changes will degrade the distribution of Rhododendrons in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.J.; Purvis, A.; Gittleman, J.L. Quaternary climate change and the geographic ranges of mammals. Am. Nat. 2009, 174, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.A.; Rosauer, D.; McCallum, H.; Skerratt, L.F. Integrating species traits with extrinsic threats: closing the gap between predicting and preventing species declines. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 278, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagoll, K.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Knight, E.; Fischer, J.; Manning, A.D. Large trees are keystone structures in urban parks. Conserv. Lett. 2012, 5, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolmer, G.; Trombulak, S.C.; Ray, J.C.; Doran, P.J.; Anderson, M.G.; Baldwin, R.F.; Morgan, A; Sanderson, E. W. Rescaling the human footprint: a tool for conservation planning at an ecoregional scale. Landscape Urban Plan 2008, 87, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Blanchard, W.; Blair, D.; McBurney, L.; Banks, S.C. Environmental and human drivers influencing large old tree abundance in Australian wet forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2016, 372, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.Z.; Li, Q.F.; Wei, G.L.; Yin, G.J.; Wei, D.X.; Song, Z.M.; Wang, C.J. The effects of the human footprint and soil properties on the habitat suitability of large old trees in alpine urban and periurban areas. Urban For Urban Gree. 2020, 47, 126520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Yang, W.; Ren, Y.; Campbell, M.J.; Wu, C.; Luo, Y.; Zhong, L.; Yu, M. Diversity and density patterns of large old trees in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blicharska, M.; Mikusiński, G. Incorporating social and cultural significance of large old trees in conservation policy. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1558–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).