This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Characterization

Infrared spectroscopy analysis (FTIR)

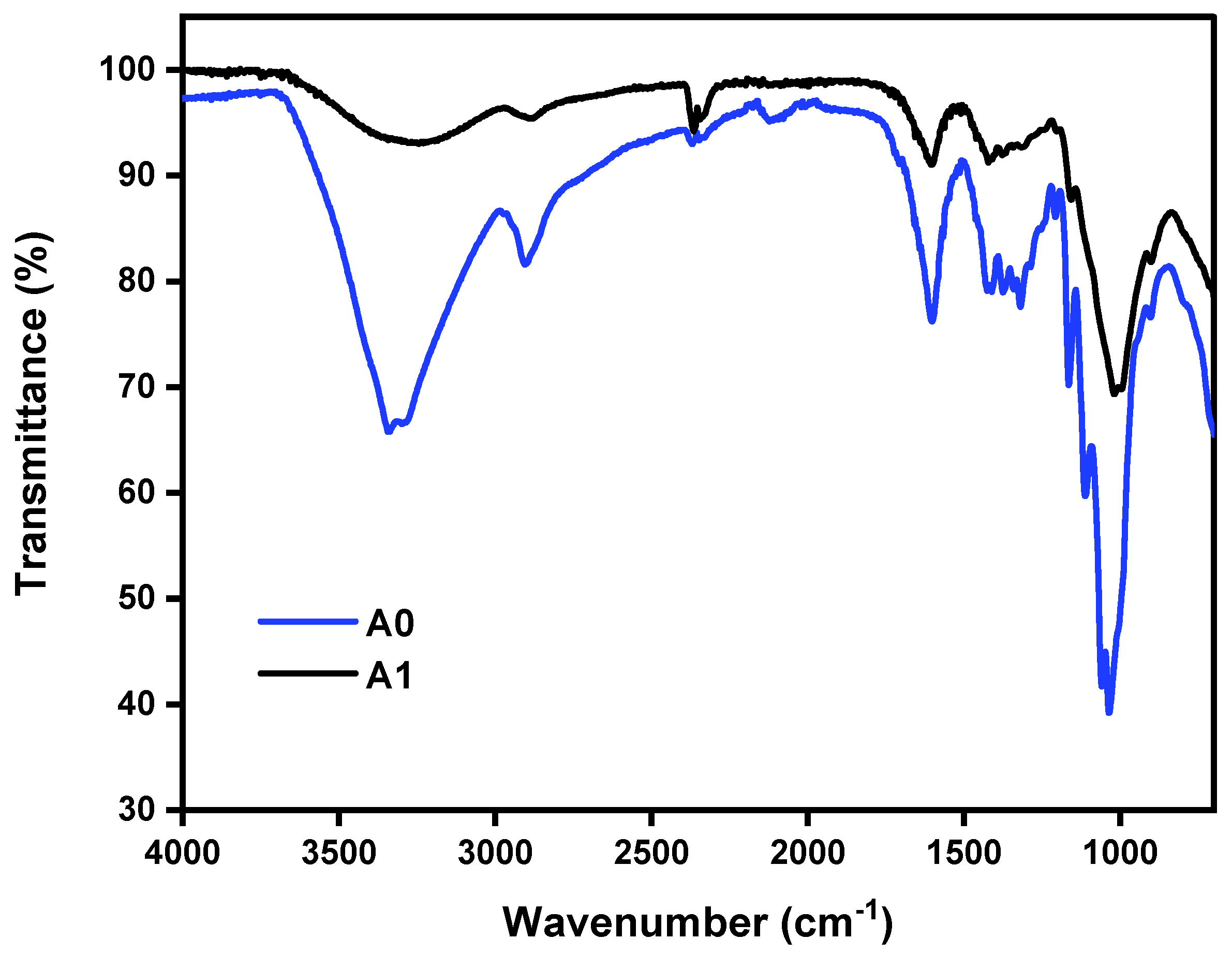

The FTIR spectra of both nanocellulose aerogel unmodified and modified with di-aminosilane are shown in

Figure 2. The spectrum of aerogel unmodified (A0) exhibited typical bands for cellulose, such as O-H stretching at 3200 cm

-1, C-H stretching at 2900 cm

-1, CH

2 symmetric bending at 1400 cm

-1, O-H and C-H bending as well as C—C and C—O stretching at 1380, 1310, and 1250 cm

-1 respectively.

The spectrum of aerogel modified (A1; spectrum identical to the sample A2 and A3, not presented) showed successful grafting of di-amino silane on nanocellulose. The band at 2900 cm

-1 was assigned to C-H stretching, the O-H stretching at 3200 cm

-1 was replaced for the band at 3300 cm

-1 assigned to N-H stretching. Also, the appearance of signals associated with vibrations from silicon-based linkages were observed at 1240 cm

-1, and between 1180 and 700 cm

-1 (Si—OH, Si—O—C) [

8,

9,

13,

14].

Nanocellulose aerogels Thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA)

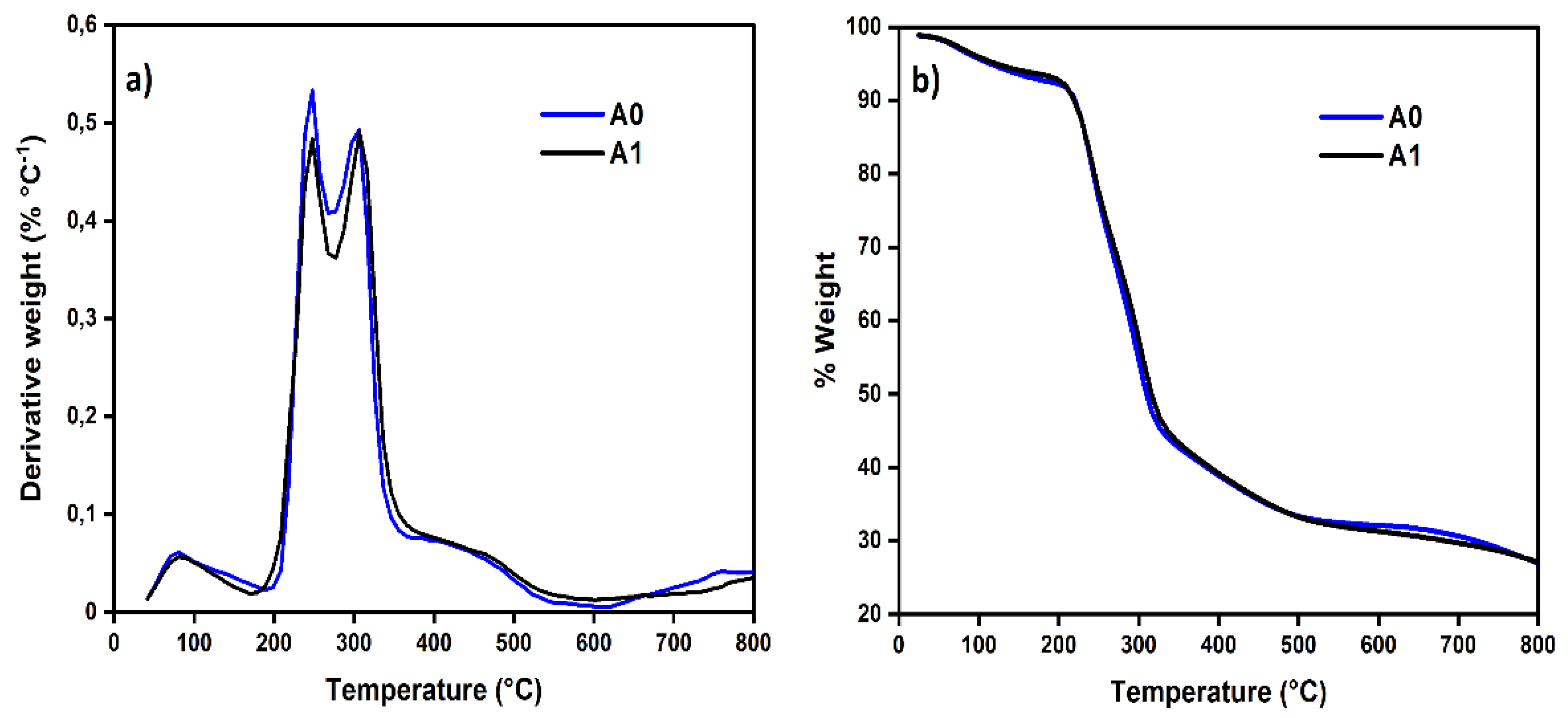

The functionalized aerogels (A1; thermogram identical to A2 and A3, not shown) were compared to unmodified (A0). Weight loss and derivative of weight loss versus temperature plots (

Figure 3) for A0 show multiple degradation events. The onset of thermal degradation is practically the same for A0 and A1 aerogels.

The samples A0 and A1 thermogram presents two weight loss events preceding the main decomposition step as clear from

Figure 3. The first degradation (between 90 and 100°C) may be attributed to loss of some bound volatile material, probably residual water. Similarly, the peak around 240 °C in all aerogel’s samples, correspond to hemicelluloses that were not removed during the pulping process. Finally, the peak around 320 ° in all samples corresponds to the degradation temperatures of the cellulose [

7,

8,

9,

14]. The developed nanomaterials (biodegradable materials) exhibited adequate thermal stability up to 240°C, which is one of the pre-requisitions of the CO

2 capture materials in the industrial scale.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (VP-SEM)

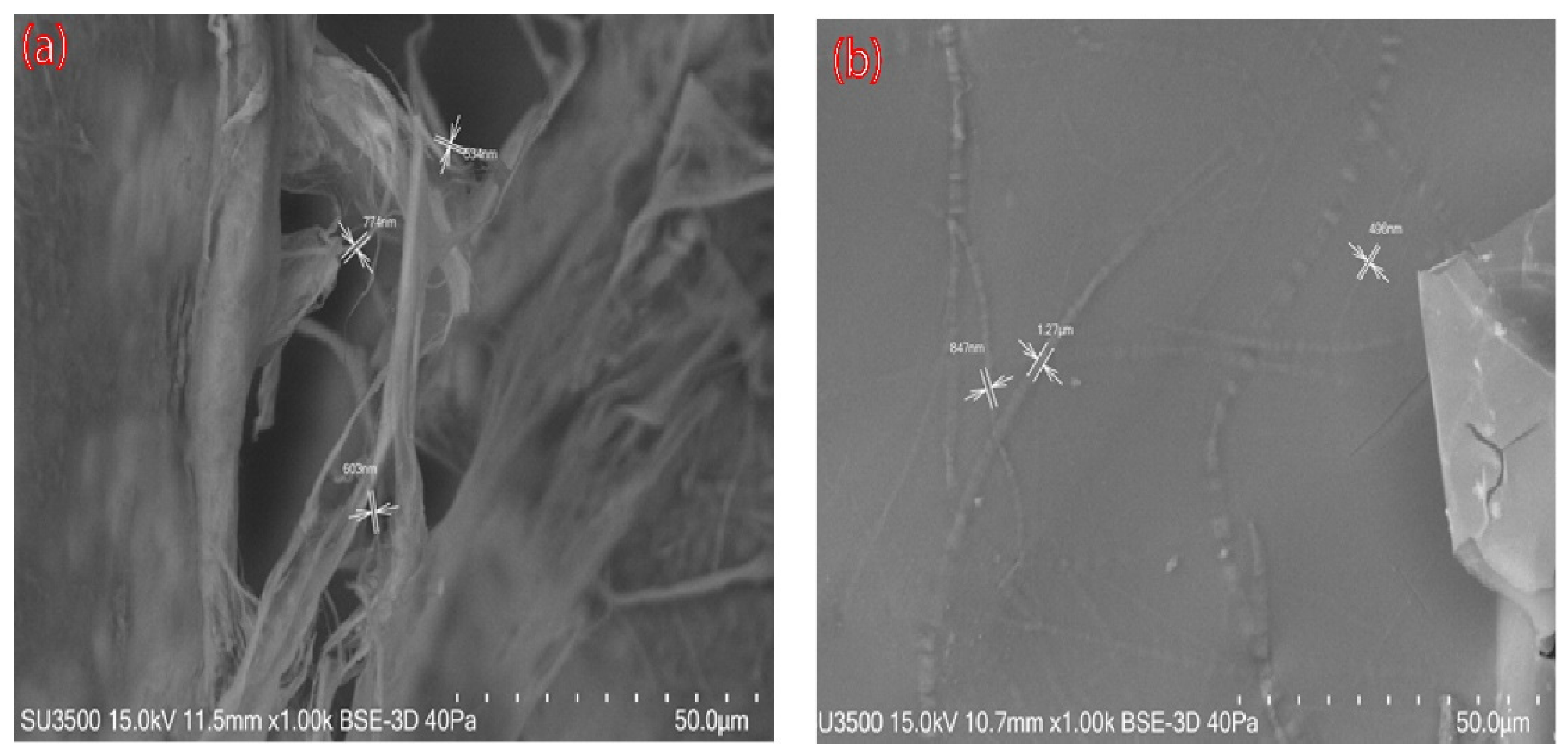

SEM images of nanocellulose aerogels modified with DAMO A0 and A1 (A1; like A2 and A3 images) are shown in

Figure 4. The unmodified aerogel exhibited a random pore structure and disorderly cross-linked CNFs were observed. After amino groups grafting, many planar structures with individual CNFs irregularly attached to the cellulose sheet were observed (

Figure 4b). These results are in accordance with the provisory reported studies in the literature [

9,

13].

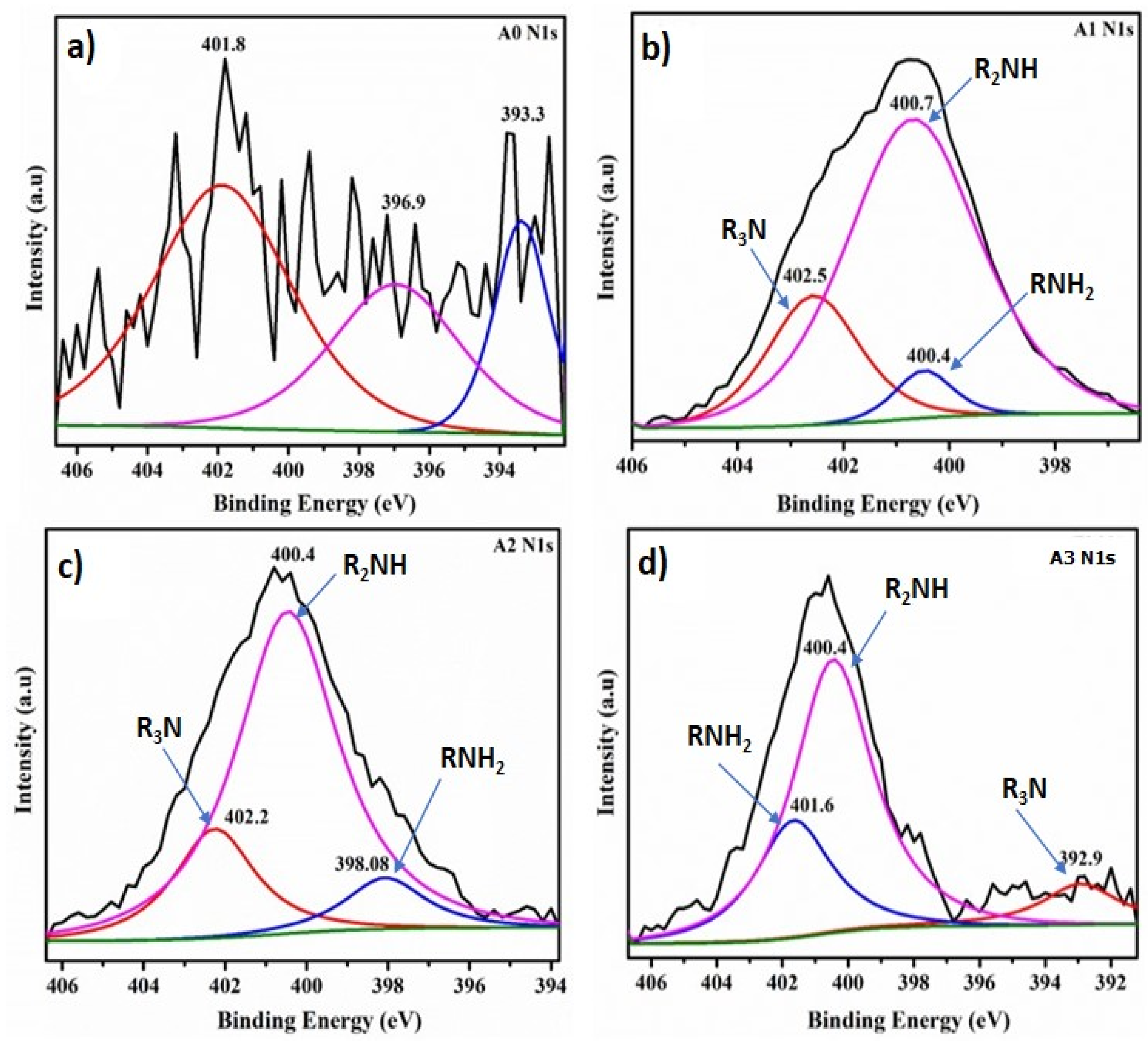

X- Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS measurements were next performed to further analyze the chemical composition and surface electronic state of the CNFs aerogel samples (

Figure 5). In

Figure 5a, the wide scan spectra of unmodified CNFs sample (A0) did not display any signals in the N1s region, but binding energy (BE) peaks from the N1s at 398–402 eV appeared in the A1, A2 and A3 samples. The N 1s spectrum of modified CNFs aerogels (

Figure 5b–d) can be fitted to three peaks with the BE at 400 (R

2NH and RNH

2) and 402.0(R

3N) eV, demonstrating that the DAMO anchored to the surface of CNFs aerogels [

7,

8,

13].

The N 1s deconvolution spectrum reveals that as the amino group loading in the aerogels increases (

Figure 5b–d), the signal intensity for the R

3N and R

2NH groups decreases, while the intensity of the RNH

2 group increases. Consequently, aerogel A3 exhibits the highest percentage of NH

2 groups grafted onto the nanocellulosic matrix, making them available for CO

2 capture.

CO2 adsorption isotherms at 273 K

CO2 adsorption isotherms were carried out at 273 K for all samples studied and were classified as type 1 isotherms in the BDDT classification, corresponding to microporous solids. To calculate the CO2 adsorption capacity, the experimental data were adjusted to Langmuir, BET, Freundlich and Temkin models.

Table 3 shows some parameters derived from the adsorption isotherms for nanocellulose aerogels at 273 K. The adsorption isotherms at 273 K are conducted at low temperatures to measure the amount of CO

2 that can be adsorbed by a material at different relative’s pressures. At this temperature, the adsorption is physical, allowing for the evaluation of the material’s maximum adsorption capacity without the effects of chemical reactions at higher temperatures. This technique is very useful for characterizing porous materials and comparing their adsorption capacity under controlled conditions. However, the results obtained at this temperature may not represent the materials behavior at temperatures more relevant to practical applications, such as CO

2 capture under environmental or industrial conditions.

For being physical adsorption in multilayers, the BET model was used to calculate the amount of CO

2 adsorbed. Nanocellulose aerogels modified with different amino-silane loads, i.e., 4.62, 9.24 and 13.87 mmol, showed CO

2 adsorption of 0.21, 0.25 and 0.22 mmol CO

2 g

-1. at 273 K, this adsorption was due to physisorption. No significant differences were observed in the adsorption of the 3 aerogels studied. Aerogel A2 showed slightly higher CO

2 adsorption, due to having a slightly larger surface area than the others as can be noticed from

Table 4.

Baraka et al., 2024, indicate that most cellulose nanofiber aerogels reported in the literature have a BET surface area reaching from 7.1 to 335 m

2 g

-1. Therefore, our results are in close agreement (154 m

2 g

-1) under the same drying method (Freeze-drying) and functionalization method (Liquid-phase) [

18].

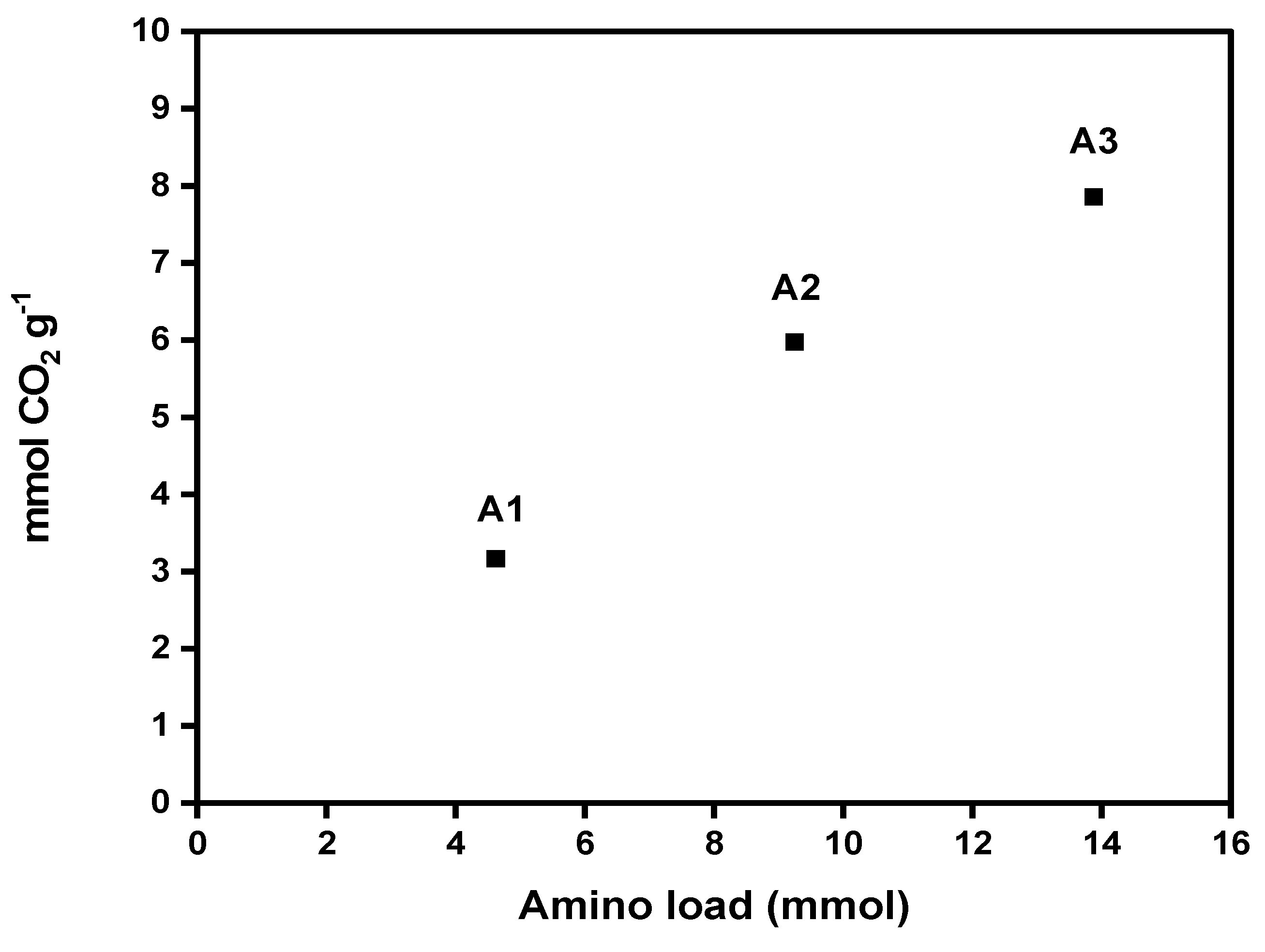

3.1.1. CO2 Adsorption Capacity Through Pressure-Decay Technique at 298 K and 4 bar

Figure 6 shows CO

2 adsorption capacities of each aerogel (A1, A2, A3). The values obtained for the DAMO-modified nanocellulose aerogels reached from 3.17 to 7.86 mmol CO

2 g

-1 at 25 °C, proving a significant increase in CO

2 adsorption with the increase in amino group content in the nanocellulose aerogel. These results are promising. The literature reports CO

2 adsorption capacities of amine-modified cellulose nanofiber aerogels (CNFs) ranging from 1.39 to 2.4 mmol g

-1. These values are lower than those achieved in the present work at the same adsorption temperature. Sepahvand et al., (2020) obtained 5.2 mmol g

-1 of CO

2 adsorption from CNFs modified with phthalimide (1.5% phthalimide content) under the same Freeze-drying and Liquid-phase functionalization method, though using a non-linear amine (phthalimide). However, this value is lower than the adsorption capacities achieved by the sample A2 and A3, attaining a CO

2 capture value of 5.98 and 7.86 mmol g

-1 respectively [

13].

Moreover, it is observed that the obtained results are higher than the adsorption capacities of other typical adsorbents used in CO

2 capture. For example, APTS-modified MCM-41, reached 1.33 mmol CO

2 g

-1 [

19]. Furthermore, MCM-41 exhibit higher BET surface area (1602 m

2 g

−1) than the nanocellulose aerogels studied in the present work.

The high adsorption values obtained are mainly explained by the chemisorption mechanisms between the amino groups and CO

2 molecules. The reaction of CO

2 with DAMO involves a direct reaction between the carbon atom of CO

2 and the nitrogen atom of the amine, forming a covalent bond [

20,

21]. Therefore, chemical modification of nanocellulose with amine moieties enhances the adsorption capacity by providing many active binding sites that promote interactions between the aerogel and CO

2 molecules [

20,

21]. The molar ratio of amine introduced could also significantly influence the CO

2 adsorption efficiency of modified nanocellulose aerogels. A high concentration of amine promotes a high adsorption capacity [

22].

This trend is consistent with the results obtained from the XPS analysis proving the higher %NH

2 where a linear tendency was observed. With a higher amino group loading, there was an increased nitrogen content (amino group according to the supported amine reaction mechanism, via carbamate ion) that was grafted onto the nanocellulosic matrix. Additionally, there was also greater CO

2 adsorption capacity measured at room temperature. Regarding our results, a significant increase in CO

2 adsorption is observed with a slight increase in DAMO loading (A1: 11.25wt %, A2: 11.30 wt %, and A3: 11.35 wt%). The Pressure Decay Technique can be used at different temperatures and pressures, allowing for a simulation closer to real operating conditions. It is useful for studying the kinetics of adsorption and desorption and the adsorption capacity [

18].

Unlike most studies reported in the literature, this research uses the Pressure Decay Technique to determine the amino-functionalized CNFs aerogel maximum reversible adsorption CO

2 capacity. This method allows for pressures above atmospheric levels, making it possible to evaluate how increased pressure affects the adsorbent capacity at room temperature. This approach more accurately simulates the higher-pressure conditions typical of industrial carbon capture and utilization processes. The high CO₂ adsorption capacity of sample A3 (with the biggest amino group load) compared to review literature studies, is largely attributed to raising the pressure from around 1 bar to 4 bar [

23]. The higher CO₂ pressure enhanced CO₂ density and its interaction with amino groups on the aerogel surface, promoting efficient carbamate ion formation and enabling greater CO₂ capture.

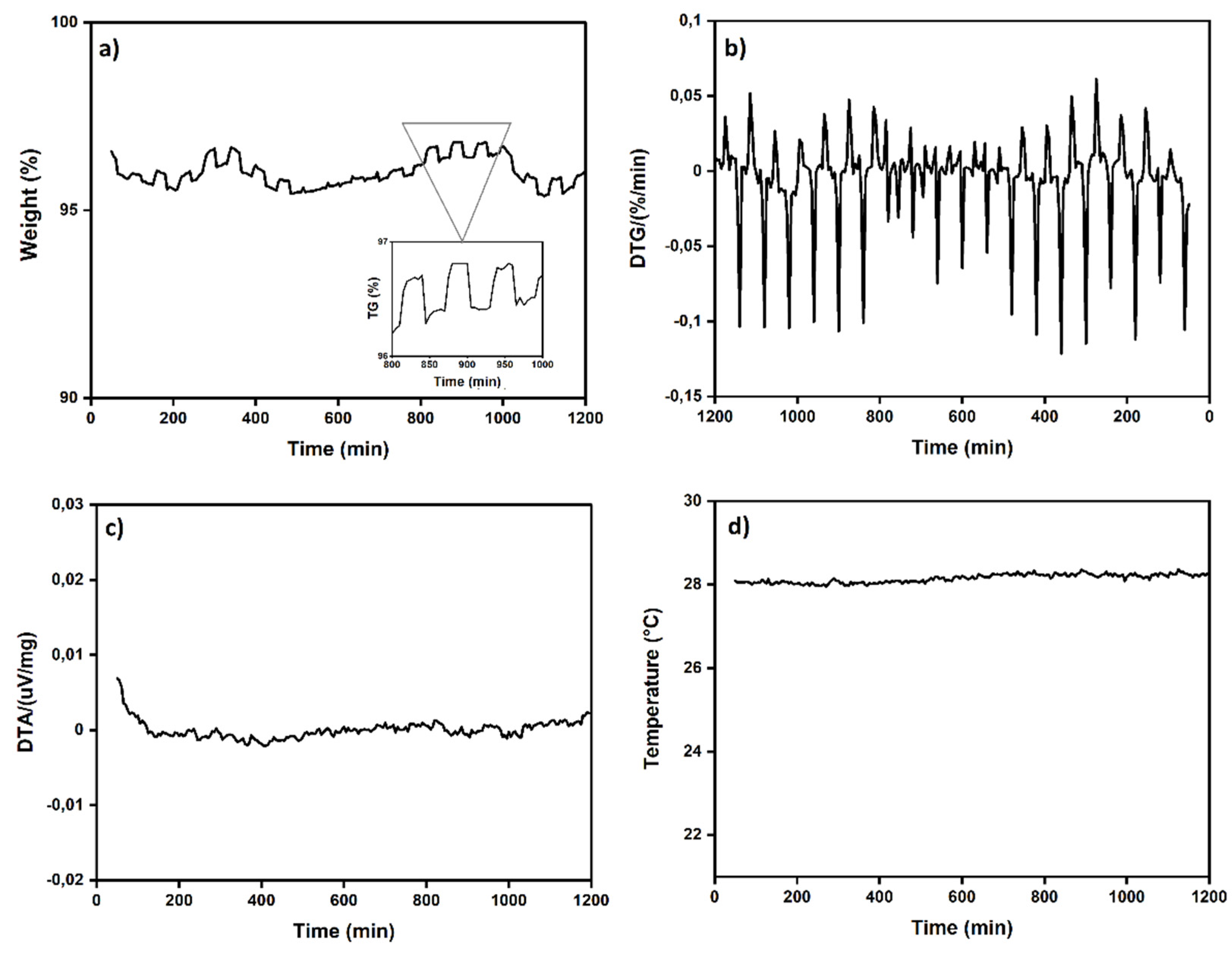

3.1.2. Nanocellulose Aerogels Lifespan

The study of CO

2 adsorption/desorption cycles was conducted using the aerogel that exhibited the highest CO

2 adsorption, specifically sample A3.

Figure 7 shows that the CO

2 desorption was fast and completed after 30 min. 95 wt %. of the absorbed CO

2 was desorbed during 20 adsorption/desorption cycles (reversible adsorption) measured at room temperature (298 K) in the thermobalance (TGA). It can be concluded that this number of cycles is likely higher since after 20 cycles, the aerogel continued to exhibit the same behavior as in the first cycle. Gebald et al.,2011 and Zhu et al.,2011, reported for a similar substrate, the CO

2 desorption was fast and completed after 30 min. More than 85% of the CO

2 was desorbed within 19 min at a packed bed temperature below 80°C [

7,

13,

14].

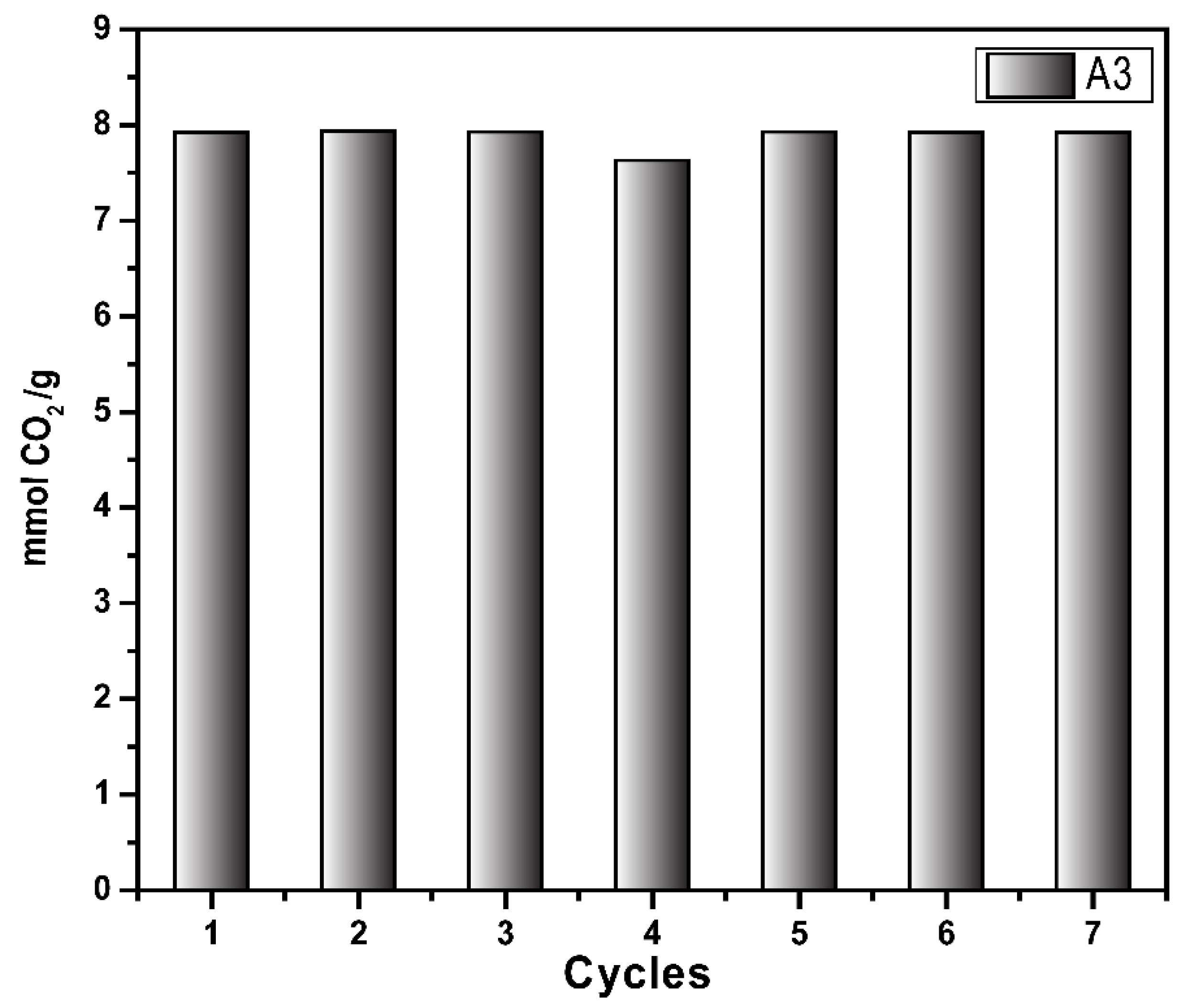

Figure 8 shows the sorption/desorption test (Pressure Decay Technique) using the same sample (A3) up to 7 cycles. The sample was regenerated by heating up to 70°C at the end of each sorption test. The results prove that the sample retains the CO

2 sorption capacity up to 7 cycles which can be likely higher as the sample retained to exhibit the same sorption capacity as the 1st cycle, demonstrating the recyclability of the synthesized material. These results agree with results obtained from the adsorption/desorption cycles determination at 298 K by thermogravimetric analysis. Both techniques showed the stability and reusability of the synthesized materials, which is one of the pre-requisitions of the CO

2 capture materials in the industrial scale.