1. Introduction

Ukraine has well-developed centralized and decentralized heat supply systems, primarily based on heating boilers and combined heat and power plants (CHPs). One of the significant directions for the development of heat supply systems is their decentralization, along with the implementation of technologies and measures aimed at enhancing community energy independence and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and pollutants.

A promising area for the development of heat supply systems (HSS) is the implementation of heat pumps (HPs) for heating, cooling, and hot water supply. Heat pumps enable efficient use of energy carriers to meet consumer needs.

Heat pumps represent a technology that efficiently utilizes renewable energy from the environment for heating and cooling applications. The difference between the useful energy produced by a heat pump and the energy consumed to power the unit is considered renewable energy [

1]. In Europe, heat pumps play a crucial role in plans to achieve greater energy independence and decarbonization. At least 60% of heat pumps sold in Europe are also manufactured there, and this share continues to grow. In 2023, 3.02 million heat pumps were sold across 21 European countries, reaching a total of approximately 24 million units. Their operation produced 231.3 TWh of renewable energy.

The heat pumps operating in Europe by 2023 saved 292.4 TWh of final energy and 129.2 TWh of primary energy. The units sold in 2023 alone helped avoid 7.28 million tons of CO₂ emissions. The total installed heat pumps prevented 59.13 million tons of CO₂ emissions, which accounts for approximately 7.3% of the EU's overall absolute GHG reduction target for 2022 [

2].

Europe hosts more than 250 production sites for heat pumps, with the sector representing €7 billion in investments during 2022–2025. Approximately 168,000 people are directly employed in the heat pump industry, with the workforce having more than tripled over the past seven years [

1,

2].

Numerous studies worldwide are dedicated to investigating the efficiency and integration of heat pumps into existing heat supply systems, as well as their role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Heat pumps have emerged as a pivotal technology in this transition, offering efficient and sustainable heating solutions by harnessing renewable energy sources [

3]. The Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) is a critical metric for evaluating the economic viability of heat pump systems over their lifetime, making comparative analyses essential for informed decision-making [

4].

Heat pumps operate by transferring thermal energy from low-temperature sources to high-temperature sinks, utilizing various renewable sources such as ambient air, ground, water, and waste heat [

5]. Their environmental benefits are substantial; for instance, Liu et al. [

6] demonstrated that a direct-expansion photovoltaic-thermal (PV/T) heat pump system in China had a life cycle environmental impact of only 3–5% compared to electric boilers. Similarly, Naumann et al. [

7] found that residential heat pump systems, especially when integrated with photovoltaic (PV) systems, exhibited the lowest environmental impacts among various heating options.

Integration with renewable energy sources enhances the sustainability of heat pumps. Solar-assisted heat pumps, for example, utilize solar energy to improve performance and reduce reliance on conventional energy sources. Abbas et al. [

8] evaluated a novel series-coupled PV/T and solar thermal collector with a solar direct expansion heat pump system, achieving a payback period of 5.20 years and significant energy savings. Chinnasamy et al. [

9] conducted a techno-economic analysis of a heat pump with a modified solar-air source evaporator for water heating, showcasing improved performance and feasibility. Moreover, hybrid systems combining heat pumps with other renewable technologies have shown promise; Obalanlege et al. [

10] analyzed a hybrid PV/T solar-assisted heat pump system for domestic hot water and power generation, achieving a discounted payback period of 14 years and significant CO₂ emission reductions.

Geothermal and sewage source heat pumps offer alternative renewable integration. Cavagnoli et al. [

11] investigated the revitalization of historical heritage buildings using an innovative geothermal system, demonstrating consistent performance and economic benefits. Ma et al. [

12] assessed building heating by a sewage source heat pump coupled with a heat storage system, highlighting thermophysical benefits and reduced payback periods. Zhang et al. [

13] performed a carbon-neutral and techno-economic analysis for sewage treatment plants, demonstrating the environmental and economic benefits of sewage source heat pumps. Additionally, Jeßberger et al. [

14] maximized the potential of deep geothermal energy by increasing thermal output using large-scale heat pumps, enhancing the sustainability of heating systems.

Techno-economic evaluations are essential for determining the feasibility of heat pump installations. Metrics such as LCOH, Net Present Value (NPV), and payback period are commonly used. Gudmundsson et al. [

15] compared fourth and fifth-generation district heating systems, emphasizing that while both improve energy efficiency, LCOH is critical for decision-making. Saini et al. [

16] conducted a techno-economic comparative analysis of solar thermal collectors and high-temperature heat pumps for industrial steam generation, finding that optimal system design could achieve cost parity. Similarly, Masiukiewicz et al. [

17] presented a methodology for sizing air-water heat pumps based on climate data, aiding in optimal selection and economic assessment.

Heat pumps play a crucial role in modernizing district heating networks (DHNs) by improving efficiency and enabling the utilization of low-temperature heat sources. Topal and Arabkoohsar [

18] proposed an ultra-low temperature DHN with neighborhood-scale heat pumps and triple-pipe distribution, resulting in a lower LCOH and improved performance. Sifnaios et al. [

19] demonstrated that integrating pit thermal energy storage in DHNs could decrease LCOH by 14% with a payback period of one year. Moreover, Javanshir and Syri [

20] analyzed a highly renewable and electrified DHN operating in balancing markets, emphasizing the role of heat pumps in providing flexibility and integrating renewable energy. Fambri et al. [

21] investigated power-to-heat plants in DHNs, concluding that flexible operation of heat pumps could absorb renewable over-generation, leading to economic benefits.

In industrial applications, high-temperature heat pumps are gaining attention for their ability to supply process heat up to 200 °C, thus enabling efficient electrification and reducing reliance on fossil fuels. Vieren et al. [

22] explored vapor compression heat pumps supplying process heat in the chemical industry, highlighting opportunities for decarbonization. Soo Kim et al. [

23] studied carbon emissions and economics of a high-temperature heat pump system for industrial processes, demonstrating that coupling with renewable energy sources could reduce emissions economically. Additionally, Sazon and Nikpey [

24] modeled a solar-assisted ground-coupled CO₂ heat pump for space and water heating, investigating performance under various conditions.

Economic evaluations and market considerations are critical for the adoption of heat pump technologies. Barberis et al. [

25] analyzed the integration of a heat pump in a poly-generative energy district, demonstrating reductions in gas consumption and a payback period of less than five years. Im and Youn [

26] studied the impact of electricity pricing on cogeneration models, highlighting the need for operational strategies to maximize economic benefits. Javanshir et al. [

27] emphasized that fluctuations in electricity and fuel prices significantly affect the profitability of DHNs with power-to-heat coupling.

Environmental and life cycle assessments further underscore the benefits of heat pumps. Yang et al. [

28] assessed sustainable heat technologies in Harbin, China, indicating that the environmental benefits of heat pumps depend on the cleanliness of the electricity grid. McTigue et al. [

29] conducted a techno-economic analysis of recuperated Joule-Brayton pumped thermal energy storage, highlighting the competitiveness of thermal storage technologies coupled with heat pumps. Additionally, Hai et al. [

30] performed exergo-economic and exergo-environmental evaluations of a novel multi-generation plant powered by geothermal energy, demonstrating the potential for integrated systems.

In Ukraine, the adoption of heat pumps is gaining attention due to the country's commitment to energy efficiency and reducing reliance on fossil fuels [

31]. Implementing heat pumps aligns with Ukraine's goals for energy independence and environmental sustainability. Understanding the techno-economic and environmental aspects of heat pump systems is vital for their successful implementation. Comparative analyses of LCOH in different heat supply systems are particularly relevant for informing investment decisions and policy formulations in Ukraine. Masiukiewicz et al. [

17] emphasized the importance of climate-based sizing and economic assessment of heat pumps for residential heating, which is directly applicable to Ukrainian conditions.

Increasing the production of thermal energy using heat pumps will contribute to enhancing the country’s energy independence. When combined with electricity generated from renewable energy sources, including wind and solar power plants, this will further reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [

32].

In [

33], projections suggest that the production of thermal energy by heat pumps and electric boilers, integrated into district heating systems, could increase 4.8 times under a pessimistic scenario, from 1.37 to 16.6 million Gcal per year, and up to 16.6 million Gcal per year in an optimistic scenario. The study in [

34] estimated the annual energy potential for thermal energy production by heat pumps within Ukraine’s centralized heating systems at 62.6 million Gcal per year as of 2020. Of this potential, 22.2% is derived from natural low-temperature sources—air (2.2%), river water (16.9%), and soil or groundwater (3.1%)—while 77.8% comes from anthropogenic sources, including ventilation emissions, wastewater, exhaust gases, and cooling water.

Unfortunately, there are no official statistical data on the sales or thermal energy production volumes of heat pumps in Ukraine. The market is dominated by imported heat pumps, with 99% of air-to-water heat pumps being imports as of 2024. Some sellers rebrand Chinese air-to-water heat pumps as their own products, and certain manufacturers assemble heat pumps using imported components and materials. In 2024, the Ukrainian company Hajster began serial production of air-to-water heat pumps, but production volumes remain small (up to 150 units in 2024). Domestic manufacturers, including AіK, BeeGreen, Hajster, GeoSun, and others, account for 4–5% of the geothermal heat pump market. Among Ukrainian producers, only Hajster is a member of the European Heat Pump Association [

35,

36].

Market studies of heat pumps in Ukraine for 2021, based on customs data, focus solely on imported equipment. These studies show the total number of imported units rather than the number of heat pumps actually installed. In 2020, 1,433 heat pumps were imported, and in 2021, this number increased to 3,019. By 2023–2024, the estimated annual installation of heat pumps of all types and capacities in Ukraine ranged from 1,300 to 1,500 units. The ratio between air-source and geothermal heat pumps in Ukraine mirrors European trends, standing at approximately 85% to 15%. Most sales are air-to-water heat pumps with capacities of 10–15 kW.

The Ukrainian heat pump market is 90% focused on new construction, with only about 10% installed during building renovations. In Europe, the situation is vastly different, with 75–80% of installations occurring in the renovation market. In Ukraine, up to 90% of heat pumps are installed in private residential buildings, with the remainder in commercial or industrial facilities [

35,

36,

37].

According to estimates by the National Association of Heat Pumps of Ukraine, in 2017, 2,884 GWh of thermal energy was produced using heat pumps: reversible air conditioners and air-to-air heat pumps 1,384 GWh, ground-to-water heat pumps 898 GWh, water-to-water heat pumps 540 GWh, air-to-water heat pumps 61 GWh, air-to-air heat pumps, 22 GWh.

These estimates are based on recommended (typical) operational characteristics of heat pump installations and reflect potential rather than actual production values [

38].

Implemented Heat Pump Systems in Ukraine.

Residential Sector. Heat pumps are actively installed in private households across Ukraine. In the construction of new private houses, up to 80% of homeowners who desire integrated systems for heating, cooling, and hot water supply choose to install heat pumps. In recent years, heat pumps of various types and capacities, ranging from 7 to 45 kW, have been installed [

39,

40,

41].

Public Buildings. The reconstruction of medical facilities destroyed by Russian missile strikes often involves the use of renewable energy sources (RES). For example, in a clinic in Horenka, Kyiv region, a geothermal heat pump with a capacity of 20 kW was installed for heating and hot water supply [

42]. In the Kostopil Multidisciplinary Hospital in the Rivne region, a heat pump with a capacity of 16 kWh is being installed, which not only reduces heating costs but also ensures energy independence from city networks [

43]. In previous years, various projects utilizing heat pumps have been implemented, including systems operating on external air heat (small social infrastructure facilities [

44,

45,

46]), wastewater (sanatoriums in Truskavets [

47] and Morshyn [

48]), and other sources (infrastructure facilities [

49,

50]).

Industrial Sector. Heat pump systems are also being implemented in the industrial sector. For instance, an administrative-production building of a fruit storage complex in the Chernivtsi region uses a cascade air-to-water heat pump by Waterkotte with a capacity of 76 kW as a source of heat and cooling [

51].

At present, economic efficiency indicators are the primary criteria for evaluating the feasibility of implementing new equipment. For heat supply systems, one of the key indicators demonstrating the viability of technology or equipment in the near term is the cost of heat energy. In [

31], the Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) was evaluated for small-scale heat supply projects (e.g., private houses, sports centers) based on open-source data, primarily from promotional materials by companies specializing in the design and installation of heat pump systems. The results indicated the economic attractiveness of such systems only under specific conditions.

The review above underscores the importance of heat pumps as sustainable energy solutions and highlights the critical role of comparative LCOH analyses in evaluating their economic viability. So, this article aims to explore these aspects further within the Ukrainian context. By focusing on the LCOH and integrating findings from various studies, the article informs policymakers, stakeholders, and investors about the potential benefits and considerations of adopting heat pump technologies in Ukraine.

The aim of this article is to compare the calculated LCOH for projects and for already operating heat supply systems of the same type under Ukrainian conditions. Assessing actual economic indicators will allow for more accurate forecasting of the development of heat supply systems and the volumes of fuel and energy resource consumption.

Two hypotheses were set up.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The prices listed on the websites of specialized companies engaged in the design, sale and installation of heat supply systems with heat pumps are underestimated.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). For two heat supply systems with the same heat pump, their technical and economic indicators may differ significantly.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Levelized Cost of Heat

The Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) is a metric used to assess the cost of heat energy production over the lifecycle of a system. It accounts for both capital and operational expenditures, enabling the comparison of different energy conversion technologies based on their costs. LCOH is defined as the constant cost of generating a unit of heat, equivalent to the discounted costs incurred throughout the lifecycle of the investment [

52,

53]. The fundamental formula for calculating LCOH is as follows:

where I

t is the initial investment costs in

tth year, UAH (USD); M

t is the operations and maintenance costs of the heat supply system in

t-th year, UAH (USD); F

t is the fuel costs in

t-th year, UAH (USD); H

t is the heat generation in

t-th year, Gkal (GJ, MW‧h); r is the discount rate; N is the lifetime of the project, years.

2.2. General Input Data

The LCOH was calculated for "ground-to-water" and "air-to-water" heat pump (HP) systems. The analysis included operational facilities (implemented projects featuring heat pumps from Waterkotte (Germany) and Hajster (Ukraine)) and projects presented on the websites of companies specializing in the design and installation of such systems or calculated based on those projects (calculated projects).

Calculations were based on the following prices, tariffs, and conditions:

Exchange rate: The average commercial exchange rate of the Ukrainian hryvnia to the euro as of August 1, 2024, was 44.4 UAH/€.

Discount rates: 0% and 10%. The choice of a 10% discount rate for social projects in developing countries was justified in [

54].

Operational lifespan: 30 years for "ground-to-water" HP systems, 20 years for "air-to-water" HP systems.

Depreciation: Not considered.

Personnel costs: Not included, as private houses were the primary focus.

Maintenance costs: 3,000 UAH/year for private houses, 10,000 UAH/year for commercial facilities with HP systems up to 50 kW, and 24,000 UAH/year for those over 150 kW.

Repair costs: 0.1% annually of the system's value. Thus, the operations and maintenance costs were limited to the expenses for maintenance and repair

2.3. Electricity Tariffs

As of June 1, 2024, the electricity tariff for individual and collective residential consumers in houses and apartments with electric heating during the period from October 1 to April 30 was set at 2.64 UAH/kWh for consumption up to 2,000 kWh/month and 4.32 UAH/kWh for other cases. Owners of two-zone meters paid half the price for electricity consumed between 23:00 and 07:00 [

55].

For public institutions in July–August 2024, electricity prices in public procurement announcements on the Prozorro platform [

56] ranged from 7.30 to over 10 UAH/kWh. The weighted average price on the day-ahead market for July 2024 was 5,967.11 UAH/MWh, excluding VAT [

57]. Since private enterprises lack a fixed electricity price and price data for energy resources and raw materials is often confidential, an average electricity cost of 8.50 UAH/kWh was assumed for small commercial facilities. It was further assumed that all projects used a two-zone electricity tariff, applying a 50% discount for night hours (23:00–07:00) [

58]

2.4. Heat Energy Production During Night Hours

In Ukraine, consumers utilizing a two-zone tariff pay 50% less for electricity consumed during the night (23:00–07:00) [

55]. In the absence of specific hourly consumption data, night-time electricity consumption was estimated as follows: it was assumed that all heat energy for domestic hot water (DHW) and one-third of the heat energy for space heating is produced at night, amounting to an average of 50% of total electricity consumption.

The calculations did not account for the tariff increase to 4.32 UAH/kWh for residential consumers with electric heating who exceed 2,000 kWh/month during October–April, as monthly consumption data was unavailable. Based on the average monthly electricity consumption of heat pump systems Nos. 1–9, it was determined that winter electricity consumption is less than 2,000 kWh/month for 18 kW heat pumps.

2.5. Characteristics of Heat Pump-Based Heat Supply Systems

An approximate cost estimate for a heat supply system with a Softenerqi SE 4.5 HP (Ukraine, 4.7 kW) is provided in [

59]. For a system with a Smart Classic 004 BW HP (Germany, 4.05 kW) [

60], the investment cost structure was similar to the previous project [

59].

A heat supply system project with a VDE 310 HP (331 kW capacity, cost: €51,000) [

61] was evaluated based on specific costs per kW for the geothermal field and heating system, with other components calculated proportionally [

59].

The cost of a heat supply system with two "air-to-water" Mitsubishi Electric Zubadan PUHZ-SHW230YKA HPs, designed to provide year-round heating, DHW, and cooling for a fitness center, is detailed in [

62]. The total system cost, including fan coils, was

$51,823, with the heat pumps accounting for

$33,700.

Annual heat energy production for projects Nos. 11–14 was calculated using a typical heat load schedule for Kyiv and Kyiv region, constructed analogously to [

63]. Heat supply was assumed to be entirely provided by the heat pumps.

Detailed descriptions of the calculated projects are provided in [

31]. The main characteristics of the heat supply systems selected for analysis are summarized in

Table 1.

Projects Nos. 1–11 are located in Kyiv, Lviv, and Ivano-Frankivsk regions. All systems are equipped with backup electric boilers, which did not operate during the study year, as the heat pumps met all heat energy needs. The absence of backup source operation during the heating period was attributed to relatively mild winter temperatures.

Projects Nos. 12–15 were calculated for conditions in Kyiv region, with detailed characteristics described in [

31].

3. Results

One of the most important technical indicators of heat supply systems with heat pumps is COP (Coefficient of Performance) and SCOP (Seasonal Coefficient of Performance). The efficiency and competitiveness of HSS using HPs are ultimately influenced by SCOP, defined as the ratio of the annual heat energy produced to the electricity consumed. The COP and SCOP values for the systems under investigation are presented in

Table 1.

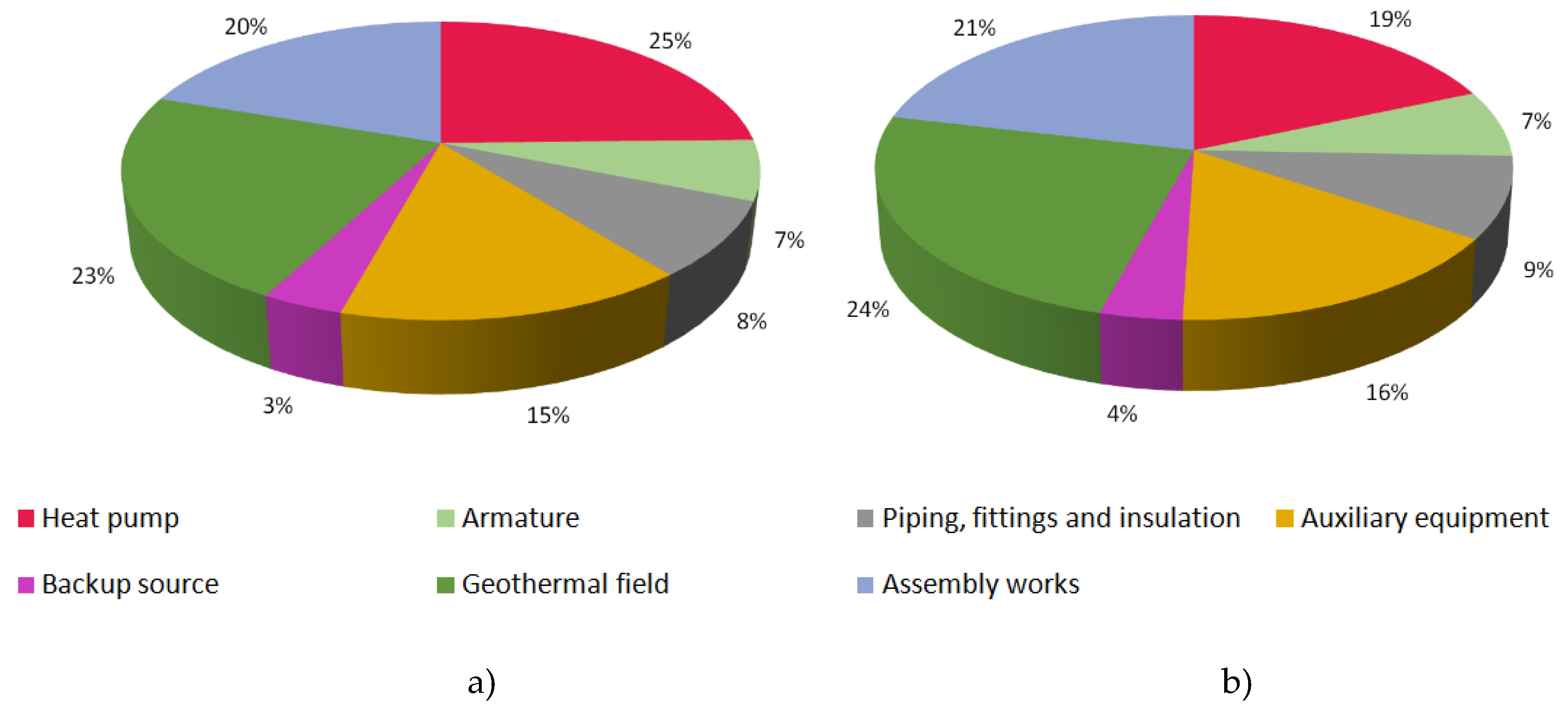

An analysis of financial costs for creating an HSS for a private house with a geothermal heat pump and a backup source (electric boiler) was performed for systems with the German Waterkotte EcoTouch DS 5045.5T and Ukrainian Hajster Grunt 30IST3R32 heat pumps (Figure 3). The cost of the German HP was comparable to the cost of arranging a geothermal field or installation work. Installing a domestic HP reduced the total system cost by 8%, with the most expensive components being the geothermal field (24%) and installation (21%). The cost of the HP itself was less than 20%.

Adhering to technological requirements is crucial when setting up a geothermal field. Proper equipment and materials with suitable technical characteristics must be used to ensure their performance over a service life of more than 50 years. Failure to meet these standards could result in the failure of the geothermal field, rendering the entire system inoperative. Restoration of a damaged geothermal field is nearly impossible.

Cost reduction measures include introducing modern drilling technologies and localizing the production of components such as ground probes, heat pumps, and sealing compounds

Figure 1.

Cost structure of heating systems for private houses with a German HP (a) and a Ukrainian HP (b) [

35,

36].

Figure 1.

Cost structure of heating systems for private houses with a German HP (a) and a Ukrainian HP (b) [

35,

36].

The cost of ground-water HPs with German systems accounted for 25-35% of the total system cost (projects 1-5), while Ukrainian HPs represented 21-26% (projects 6-9), with higher percentages corresponding to lower power capacities in both cases. In Project 10, for a house up to 50 m², the German HP accounted for 46% of the total cost. Ukrainian HPs are approximately 30% cheaper. The cost of an air-water HP from Ukraine in Project 11 reached 62% of the total system cost.

In calculated projects (12-13), the share of HPs in the total cost was significantly higher than in implemented projects, indicating underestimated overall project costs. Comparison of project costs further reveals discrepancies in other components.

The operational analysis of HS with ground-source HPs shows a significant dependence on specific user conditions. For instance, a system with a 23.5 kW HP produced 2% more heat annually than a system with a 34.5 kW HP, while consuming 28% more electricity.

The type of heating system—high-temperature (e.g., radiators, convectors) or low-temperature (e.g., underfloor heating)—also significantly affects electricity consumption. Lower heat carrier temperatures improve HP efficiency; for every 1°C reduction in temperature, the COP increases by 2.5%. Conversely, a 1°C increase in source temperature (geothermal field) boosts the COP by 2.7% [

64].

Analysis of the heating systems in Projects 1–10 (

Table 1) indicates that 60–80% of the generated heat is allocated to heating purposes. The annual heat production ranged from 1,670–2,900 kWh/kW of installed capacity for Projects 1–10 and approximately 2,400 kWh/kW for Project 11.

Throughout the year, none of the HS (Projects 1–11) required activation of their backup heat sources.

It is essential to calculate the average annual COP based on actual operational data. For example, during the summer, air-source HPs operating for DHW achieve a COP of 4.17–4.63 (partial load conditions, A15/W45, A20/W45). In freezing winter days, their COP drops to approximately 2.0 (e.g., COP of 2.2 in mode A-15/W35 and COP of 1.8 in mode A-15/W45). The SCOP for Projects 1–10 ranged from 2.8–4.1, while for Project 11, it was 3.0.

The LCOH calculations for implemented and calculated projects were performed under various electricity tariff schemes and discount rates (0% and 10%). The results are summarized in

Table 2.

The analysis of input data shows that in promotional offers, the estimated cost of HS with ground-source HPs for private homes is often understated or outdated, leading to significant underestimation of heat energy costs. While the cost of a geothermal field may equal the cost of an HP, there are additional components, such as other equipment and installation work, which can be as costly as the HP itself.

The cost structure analysis for implemented projects reveals that the share of the HP in total system costs does not exceed 40% for imported HPs and 30% for domestic HPs. For air-source HPs, the HP's cost constitutes 60–70% of the total system cost.

The actual cost of Ukrainian HPs is approximately 30% lower, and the total investment costs are 6.5%-10% lower, leading to a reduction in LCOH by 4%-7% at a 0% discount rate and by 6%-9% at a 10% discount rate. In the case of calculated projects, the cost of Ukrainian HPs was 240% lower than that of German HPs, resulting in an LCOH difference of 26%-80%.

Since the cost of HSS with HPs is relatively high, the discount rate significantly influences LCOH. An increase in the discount rate from 0% to 10% raises LCOH for ground-source HPs by 2.1–2.6 times in implemented projects, while the increase in calculated projects is slightly lower, at 1.4–2 times. For air-source HPs, the increase is 1.3–1.6 times and 1.2–1.5 times, respectively, for implemented and calculated projects, with lower values corresponding to higher electricity tariffs in all cases.

The investment component of LCOH in implemented projects with ground-source HPs accounts for 46%-80% of LCOH (German HPs) and 44%-79% (Ukrainian HPs) at a 0% discount rate. In calculated projects, it constitutes 41%-63% (German HPs) and 19%-46% (Ukrainian HPs). At a 10% discount rate, the corresponding shares are 73%-93%, 71%-92%, 69%-84%, and 43%-73%. In projects with air-source HPs, the investment component at a 0% discount rate makes up 23%-47% of LCOH in implemented projects and 17%-37% in calculated projects, while at a 10% discount rate, it accounts for 41%-68% and 32%-58%, respectively. Lower values are observed for higher electricity tariffs in all cases.

Operations and maintenance costs (fixed operating costs) in implemented projects account for 2%-6% of LCOH at a 0% discount rate, while in calculated projects, they range from 2%-4% for higher-capacity HPs to 8%-16% for lower-capacity HPs. At a 10% discount rate, these costs are 1%-2% in implemented projects and up to 8% in calculated projects.

Fuel costs (variable operating costs) indicate that the "electric heating" tariff for private households reduces LCOH in HSS with ground-source HPs by 11%-13% (0% discount rate) and by 5% (10% discount rate) in implemented projects, and by 20%-26% and 11%-16%, respectively, in calculated projects. For air-source HPs, the reduction is 23% and 26% for implemented and calculated projects, respectively, at a 0% discount rate, and 16% and 19% at a 10% discount rate.

The use of a time-of-use electricity tariff reduces LCOH in HSS with ground-source HPs by 9%-10% (0% discount rate) and 4% (10% discount rate) in implemented projects, and by 10%-18% (0% discount rate) and 5%-12% (10% discount rate) in calculated projects.

The LCOH for an implemented project with an air-source HP does not differ significantly from the LCOH for a calculated project, possibly due to the availability of realistic data on the manufacturer's website.

Attention should be given to implemented projects No. 3 and No. 4, which use identical HPs but have significant differences in COP for heating (4.3 in Project No. 3 versus 5.3 in Project No. 4), COP for domestic hot water (3.6 versus 1.4), and SCOP (4.1 versus 3.1). The annual heat energy production differs by 40%, leading to an LCOH that is 40% lower in Project No. 3.

In Projects No. 1 and No. 2, the annual heat production is nearly identical; however, due to significantly lower COP in Project No. 1, its electricity consumption is 28% higher. Despite this, its LCOH is 20%-27% lower (0% discount rate).

During the 2023–2024 heating season, the heating tariff for households in Kyiv was set at 2,586.60 UAH/Gcal. However, under martial law, a reduced tariff of 1,654.41 UAH/Gcal was applied, while the tariffs for budgetary institutions, religious organizations, and other consumers ranged from 3,833.54 to 4,781.21 UAH/Gcal [

65]. In Kharkiv, the tariff was 1,747.57 UAH/Gcal for households and 3,703.93–4,000.99 UAH/Gcal for budgetary and other consumers [

66].

The results (Projects No. 1–10 from

Table 2) indicate that HSS with HPs can be competitive with centralized heating systems for households, provided certain conditions are met. These include using time-of-use electricity tariffs, the "electric heating" tariff, and minimal or no interest rates on loans for HSS construction.

For small private enterprises (e.g., fitness centers or private wellness facilities), HSS with air-source HPs can be competitive under minimal loan interest rates or with time-of-use electricity tariffs similar to those for households.

4. Discussion

LCOH serves as a crucial metric for assessing the feasibility of implementing specific technologies under conditions of seasonal variations in heat demand and primary energy source costs. It can be used for modeling and evaluating heat energy production costs, taking into account seasonal changes in production volumes and fluctuations in COP throughout the year. Future research aims to integrate LCOH as a primary economic indicator into a mathematical and simulation model designed to assess the techno-economic efficiency of introducing and using energy conversion technologies across different seasons. This model will be employed to evaluate the prospects and feasibility of implementing technologies or equipment for heat supply, enabling comparisons of various technologies and evaluation of multiple project indicators.

The proposed model includes the following components: an input data block, an economic evaluation block (calculation of costs, payback periods, etc.), a technical assessment block (determination of technical parameters such as heat carrier temperature, pressure, and system efficiency), an energy evaluation block (calculation of energy efficiency indicators like energy intensity and EROEI), an environmental assessment block (evaluation of emissions, solid waste, and environmental fees), an output data block (calculation results), and a results analysis block.

The mathematical component of the model comprises equations and formulas used for calculations. The simulation component is applied to model the dynamic behavior of the system in real time or under various future scenarios, allowing for consideration of complex interactions between system components that are challenging to describe analytically.

For HSS with HPs, the mathematical model has unique features. Since such systems use both renewable energy sources (ambient energy) and traditional energy carriers (electricity), the economic indicators must be designed to allow comparisons with traditional heat supply systems.

One of the primary technical indicators for these systems is the Coefficient of Performance (COP), which indicates the ratio of generated heat to consumed electricity, and the Seasonal Coefficient of Performance (SCOP), which reflects the average annual efficiency of the HP. SCOP is calculated as the ratio of the total annual heat energy produced to the total annual electricity consumed. These indicators significantly impact the economic efficiency of HSS with HPs.

The efficiency and cost-effectiveness of HSS with HPs are highly dependent on the season. The COP of heat pumps for DHW production varies significantly with the season, as it depends on external ambient temperatures and the characteristics of the heat pump itself. On average, COP for HPs ranges as follows: for "air-to-water" HPs, 2-3 in winter, 3-4 in spring and autumn, and 3.5-4.5 in summer; for "ground-to-water" HPs, 3-4.5 in winter and 4-5 in spring, autumn, and summer [

64].

In the environmental assessment block, the primary indicator is the reduction of CO2 emissions and pollutants compared to systems using fossil fuels, as well as a reduction in environmental taxes or other fees. Emissions may occur only if a fossil fuel-based peak source is used. Since the analyzed period in this study did not involve the operation of such peak sources, the environmental impact of the studied HSS was negligible. If a gas boiler had operated as a peak source, the environmental impact would have been calculated as the total annual emissions of CO2 and NOx, adjusted for current environmental tax regulations and other fees, using approaches similar to those described in regulatory interaction modeling [

67].

In the energy assessment block, the key metric proposed is the efficiency coefficient of the technology or installation, which measures the extent to which the energy produced by the system exceeds the energy required for its creation, operation, and decommissioning [

68]. This metric is analogous to EROEI [

69] or the total energy intensity indicator [

70]. Energy evaluations of HSS projects using "water-to-water" HPs, which are comparable in energy consumption to HSS with "ground-to-water" HPs but more energy-intensive than HSS with "air-to-water" HPs, indicate higher energy efficiency than gas boilers of similar capacity [

63].

When analyzing risks, primary attention is given to fluctuations in electricity prices, bank interest rates or discount rates, currency exchange rates (as most HPs are either fully imported or manufactured with imported components), and seasonal effects (due to the significant impact of external temperature on COP), as these factors critically influence the economic efficiency of the system.

5. Conclusions

The use of heat pump technology for heat supply is widespread in European countries, with the number of installations increasing annually. In Ukraine, more than 90% of installed heat pumps are imported, with up to 3,000 units imported yearly. However, there is no precise data available on the heat energy production or the operational capacities of existing heat pumps. Approximately 85% of installed heat pumps in Ukraine are air-to-water systems, with 90% deployed in new buildings.

This study conducted an analysis of the Levelized Cost of Heat (LCOH) for both implemented and calculated projects based on open-source data. The projects analyzed included German and Ukrainian ground-to-water and air-to-water heat pumps used in heat supply systems for private houses and small commercial facilities. The LCOH was assessed under varying electricity tariffs and discount rates of 0% and 10%.

The findings indicate that the reported costs of heat supply systems with heat pumps on the websites of specialized companies are often understated or outdated. One possible reason is the fluctuating annual costs of equipment and materials in the country.

The analysis of implemented projects revealed that the investment component constitutes 60–65% of the LCOH for systems with air-to-water heat pumps and 20–40% for systems with ground-to-water heat pumps. In systems with Ukrainian ground-to-water heat pumps, the cost of the heat pump itself was even lower than that of the geothermal field or other components of the heat supply system.

The type and capacity of the heat pump significantly affect the LCOH. The lowest heat energy cost is achieved with air-to-water heat pumps installed in large facilities, while the highest is associated with ground-to-water heat pumps used in small private houses. For systems with low-capacity heat pumps, the discount rate has a greater influence on the LCOH than electricity prices.

An analysis of real project data shows that specific features of a heat supply system (e.g., the presence of a swimming pool) or consumer behavior (e.g., prolonged absence, overly economical or excessive hot water usage, higher indoor temperature settings) lead to variations in technical (Coefficient of Performance, COP), energy (electricity consumption), and economic (heat energy cost) performance indicators compared to other systems with identical heat pumps.

Heat supply systems with heat pumps can be economically competitive under certain conditions, such as subsidies, reduced loan rates, and preferential electricity tariffs. The use of special electricity tariffs for "electric heating" and "residential" consumers, combined with two-zone electricity metering, can significantly lower the LCOH for heat pumps, enhancing their attractiveness for widespread adoption in Ukraine.

For comprehensive and accurate evaluations of heat supply projects, it is advisable to employ mathematical and simulation models to determine the techno-economic efficiency of implementing and utilizing technologies for converting primary energy carriers into derived forms of fuel and energy. For systems with heat pumps, these models have specific features: the Seasonal Coefficient of Performance (SCOP) is proposed as the primary technical indicator, while the LCOH is recommended as the key economic indicator over the lifecycle of the system..

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S., and V.A.; methodology, V.S., V.H., S.D., and I.G.; software, A.Z., O.M., and I.G.; validation, V.S., V.H., S.K., and O.M.; formal analysis, V.S., V.H., and S.K.; investigation, V.H., and S.D.; resources, V.H., S.D., and I.G.; data curation, V.H., S.D., and I.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S., A.Z., S.K. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, V.S., A.Z., S.K. and A.V.; visualization, V.S.; supervision, A.Z., SK, and V.A.; project administration, A.Z., SK, and V.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the next projects: «Formation of technological structures of decentralized energy systems in the post-war reconstruction of the infrastructure of territorial communities in the context of combating climate change”(grant №94/0129, 2023-2024) which is financed by National Research Foundation of Ukraine; “Comprehensive analysis of robust preventive and adaptive measures of food, energy, water and social management in the context of systemic risks and consequences of COVID-19” (0122U000552, 2022-2026), “Increasing the efficiency and safety of the functioning of the unified energy system through the electrification of heat supply in Ukraine” (0123U100983, 2023-2024), and other projects, which are financed by National Academy of Science of Ukraine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- White Paper: Heat Pumps - Integrating Technologies to Decarbonise Heating and Cooling. Available online: https://www.ehpa.org/fileadmin/red/03._Media/Publications/ehpa-white-paper-111018.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- European Heat Pump Market and Statistics Report 2024. 102 p.

- Gradziuk, P.; Siudek, A.; Klepacka, A.M.; Florkowski, W.J.; Trocewicz, A.; Skorokhod, I. Heat Pump Installation in Public Buildings: Savings and Environmental Benefits in Underserved Rural Areas. Energies 2022, 15, 7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, R.; Kinoshita, Y.; Yamada, T. Green Procurement Decisions with Carbon Leakage by Global Suppliers and Order Quantities under Different Carbon Tax. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Amiri, L.; Poncet, S.; Sasmito, A.P.; Ghoreishi-Madiseh, S.A. Renewable heating solutions for buildings; a techno-economic comparative study of sewage heat recovery and Solar Borehole Thermal Energy Storage System. Energy and Buildings 2022, 259, 111892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, W.; Yao, J.; Jia, T.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, Y. Life cycle energy, economic, and environmental analysis for the direct-expansion photovoltaic-thermal heat pump system in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 434, 139730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, G.; Schropp, E.; Gaderer, M. Environmental, economic, and eco-efficiency assessment of residential heating systems for low-rise buildings. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 98, 111074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Zhou, J.; Hassan, A.; Yuan, Y.; Yousuf, S.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, C. Economic evaluation and annual performance analysis of a novel series-coupled PV/T and solar TC with solar direct expansion heat pump system: An experimental and numerical study. Renewable Energy 2023, 204, 400–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnasamy, S.; Prakash, K.B.; Divyabharathi, R.; Kalidasan, B.; Rajamony, R.K.; Pandey, A.K.; Fouad, Y.; Soudagar, M.E.M. Performance and feasibility study of a heat pump with modified solar-air source evaporator: Techno-economic analysis for water heating. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer 2024, 157, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obalanlege, M.A.; Xu, J.; Markides, C.N.; Mahmoudi, Y. Techno-economic analysis of a hybrid photovoltaic-thermal solar-assisted heat pump system for domestic hot water and power generation. Renewable Energy 2022, 196, 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnoli, S.; Bonanno, A.; Fabiani, C.; Palomba, V.; Frazzica, A.; Carminati, M.; Herrmann, R.; Pisello, A.L. Holistic investigation for historical heritage revitalization through an innovative geothermal system. Applied Energy 2024, 372, 123761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Wei, P. Thermo-economic assessments on building heating by a sewage source heat pump coupled with heat storage system. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2024, 53, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, G. Carbon neutral and techno-economic analysis for sewage treatment plants. Environmental Technology and Innovation 2022, 26, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeßberger, J.; Heberle, F.; Brüggemann, D. Maximising the potential of deep geothermal energy: Thermal output increase by large-scale heat pumps. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 257, 124240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, O.; Schmidt, R.-R.; Dyrelund, A.; Thorsen, J.E. Economic comparison of 4GDH and 5GDH systems – Using a case study. Energy 2022, 238, 121613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, P.; Ghasemi, M.; Arpagaus, C.; Bless, F.; Bertsch, S.; Zhang, X. Techno-economic comparative analysis of solar thermal collectors and high-temperature heat pumps for industrial steam generation. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 277, 116623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiukiewicz, M.; Tańczuk, M.; Anweiler, S.; Streckienė, G.; Boldyryev, S. Long-term climate-based sizing and economic assessment of air-water heat pumps for residential heating. Applied Thermal Engineering 2025, 258, 124627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topal, H.I.; Arabkoohsar, A. Enhancing ultra low temperature district heating systems with neighborhood-scale heat pump and triple-pipe distribution: A techno-economic analysis. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 95, 110316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifnaios, I.; Fan, J.; Jensen, A.R. An economic assessment of integrating a pit thermal energy storage in a district heating system. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 103, 114266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanshir, N.; Syri, S. Techno-Economic Analysis of a Highly Renewable and Electrified District Heating Network Operating in the Balancing Markets. Energies 2023, 16, 8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fambri, G.; Mazza, A.; Guelpa, E.; Verda, V.; Badami, M. Power-to-Heat plants in district heating and electricity distribution systems: A techno-economic analysis. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 276, 116543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieren, E.; Demeester, T.; Beyne, W.; Magni, C.; Abedini, H.; Arpagaus, C.; Bertsch, S.; Arteconi, A.; De Paepe, M.; Lecompte, S. The Potential of Vapor Compression Heat Pumps Supplying Process Heat between 100 and 200 °C in the Chemical Industry. Energies 2023, 16, 6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo Kim, H.; Seo, J.; Moon, S.; Ho Kim, D.; Jung, Y.; Chung, Y.; Hoon Lee, K.; Ho Song, C. Numerical study on carbon emissions and economics of a high temperature heat pump system for an industrial process. Energy Conversion and Management 2024, 322, 119150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazon, T.A.; Nikpey, H. Modeling and investigation of the performance of a solar-assisted ground-coupled CO₂ heat pump for space and water heating. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 236, 121546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, S.; Rivarolo, M.; Bellotti, D.; Magistri, L. Heat pump integration in a real poly-generative energy district: A techno-economic analysis. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2022, 15, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y.H.; Youn, Y.J. Techno-economic analysis for the effects of electricity pricing system on the market competitiveness of cogeneration model. Energy Strategy Reviews 2023, 45, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanshir, N.; Syri, S.; Tervo, S.; Rosin, A. Operation of district heat network in electricity and balancing markets with the power-to-heat sector coupling. Energy 2023, 266, 126423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Liu, W.; Kramer, G.J. Integrated assessment on the implementation of sustainable heat technologies in the built environment in Harbin, China. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 279, 116764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTigue, J.D.; Farres-Antunez, P.; J, K.S.; Markides, C.N.; White, A.J. Techno-economic analysis of recuperated Joule-Brayton pumped thermal energy storage. Energy Conversion and Management 2022, 252, 115016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, T.; Radman, S.; Abed, A.M.; Shawabkeh, A.; Abbas, S.Z.; Deifalla, A.; Ghaebi, H. Exergo-economic and exergo-environmental evaluations and multi-objective optimization of a novel multi-generation plant powered by geothermal energy. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2023, 172, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanytsina, V.V. Artemchuk, V.O. Prospects for the Implementation of Certain Types of Heat Pumps in Ukraine. Electronic Modeling 2022, 44, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babak, V. , Kulyk, M. Increasing the Efficiency and Security of Integrated Power System Operation Through Heat Supply Electrification in Ukraine. Science and Innovation. 2023, 19, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derii, V.O. , Nechaieva, T.P., Leshchenko, I.C. Assessment of the effect of structural changes in Ukraine’s district heating on the greenhouse gas emissions. Science and Innovation. 2023, 19, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derii, V. , Teslenko, O., & Sokolovska, I. Methodical approach to estimating the potential of thermal energy production by heat pump plants in case of their implementation in regional district heating systems. Energy Technologies & Resource Saving. 2023, 75, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heating, Cooling and Hot Water with Minimal Costs and Environmental Impact. Available online: https://hajster.com/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Articles by “Sahara” LTD. Available online: http://www.sahara.com.ua/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Market research: Heat Pumps 2021, Ukraine.

- Basok, B.I.; Dubovskyi, S.V. Coarse Assessment of Thermal Capacity and Volumes of Renewable Energy Production by Heat Pumps in Ukraine. Heat Pumps in Ukraine 2019, 1, 2–6. Available online: http://www.unhpa.com.ua/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/%D0%B6%D1%83%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BB-%D1%82%D0%BD2019.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Heat Pump Installations. Sahara LTD. Available online: https://caxapa.ua/informaciya-obyekti-teplovi-nasosi (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Examples of Heat Pump Installations. STO Tepla. Available online: https://www.stotepla.com.ua/ustanovka-teplovogo-nasosa/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Examples of Heat Pump Installations. Elementum. Available online: https://elementum.com.ua/uk/наші-oбєкти/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Rebuilding Better: How a Green Recovery Project Restored a Clinic in Gorentsi. Rubryka 2023. Available online: https://rubryka.com/article/vidnovlennya-ambulatoriyi-v-gorentsi/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- A Medical Facility in Rivne Oblast Installs a Heat Pump for Continuous Hot Water Supply. Eco.Rayon 2024. Available online: https://eco.rayon.in.ua/news/731394-medzaklad-na-rivnenshchini-vstanovlyue-teploviy-nasos-dlya-bezperervnogo-garyachogo-vodopostachannya (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Heating in Horishni Plavni Powered by Wastewater. Status Quo, Poltava 2017. Available online: https://poltava.sq.com.ua/rus/news/novosti/20.02.2017/poltavskiy_detsad_otaplivayut_teplom_iz_kanalizatsii/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- A New Kindergarten in Masany Saves on Heating Thanks to Heat Pumps. Chernihiv City Council 2020. Available online: https://chernigiv-rada.gov.ua/news/id-41091/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- How the Residents of Veselye Save on Energy Resources. Nakipelo 2019. Available online: https://nakipelo.ua/uk/kak-zhiteli-sela-veseloe-ekonomyat-na-energoresursa-2/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Heat Pump at the Karpaty Sanatorium (Truskavets): An Interesting Technical Solution, Maximum Efficiency. Sustainable Energy 2018. Available online: https://stala-energia.ub.ua/analitic/29118-teploviy-nasos-u-sanatoriyi-karpati-truskavec--cikave-tehnichne-rishennya-maksimalna-efektivnist.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- A Sanatorium in Morshyn Saves 39,000 m³ of Gas Annually Using Solar and Wastewater Heat. ECOTOWN 2014. Available online: https://ecotown.com.ua/news/Sanatoriy-u-Morshyni-shchoroku-ekonomyt-39-tys-m3-hazu-zavdyaky-vykorystannyu-tepla-sontsya-i-tepla-/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Horishni Plavni Uses Sewage Heat to Heat the Premises of Vodokanal. Ukraine Today 2017. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tQgE1dobJI4 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Horishni Plavni Uses Wastewater Heat for Heating. Budportal 2017. Available online: http://budport.com.ua/news/4733-u-gorishnih-plavnyah-vikoristovuyut-teplo-stichnih-vod-dlya-opalennya (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Administrative and Industrial Building, Chernivtsi Region. Sahara LTD. Available online: https://caxapa.ua/nashi-proekty-teplovi-nasosy-administratyvno-vyrobnycha-budivlia-kompleksu-fruktoskhovyshch-chernivetska-oblast (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Gerssen-Gondelach, S.J.; Saygin, D.; Wicke, B.; Patel, M.K.; Faaij, A.P.C. Competing Uses of Biomass: Assessment and Comparison of the Performance of Bio-Based Heat, Power, Fuels and Materials. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 40, 964–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffino, E.; Piga, B.; Casasso, A.; Sethi, R. Heat Pumps, Wood Biomass and Fossil Fuel Solutions in the Renovation of Buildings: A Techno-Economic Analysis Applied to Piedmont Region (NW Italy). Energies 2022, 15, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanytsina, V.; Artemchuk, V.; Bogoslavska, O.; Zaporozhets, A.; Kalinichenko, A.; Stebila, J.; Havrysh, V.; Suszanowicz, D. Fossil Fuel and Biofuel Boilers in Ukraine: Trends of Changes in Levelized Cost of Heat. Energies 2022, 15, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electricity Tariffs for Household Consumers from 01.06.2024. Available online: https://yasno.com.ua/news/all_news/electricity-tariffs-for-household-consumers-from-01-06-2024 (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Prozorro Public Procurement System. Available online: https://prozorro.gov.ua/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- July Index: Electricity BASE Price on Day-Ahead Market at 5567.20 UAH/MWh. Operator Rynku. Available online: https://www.oree.com.ua/index.php/newsctr/n/24329 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Switching to "Night" Tariff. Lvivoblenergo. Available online: https://loe.lviv.ua/page/zony_oblik (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Heat Pumps Softenerqi (Ukraine). Renevita. Available online: http://renevita.com.ua/теплoвые-насoсы/теплoвые-насoсы-softenergi-украина.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Heat Pumps. Kontaktor. Available online: https://kontaktor.com.ua/energy-saving/teplovy-e-nasosy/ (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Heat Pump VDE ТН-310 (331.6 kW). ESTAR. Available online: https://energostar.kiev.ua/ua/p141429470-teplovoj-nasos-vde.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Heat Pump "Air-Water" Mitsubishi Electric 2x23 kW (Case for a House of 500 m²). Available online: https://nse.com.ua/ru/oбъекты/теплoвые-насoсы/puhz-shw230yka_fitness.html (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Bilodid, V.D.; Stanytsina, V.V. Evaluation of the Efficiency of Heat Energy Generation by Heat Pump Stations Based on Low-Temperature Groundwater Heat. Problems of General Energy 2020, 3, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heat Pump Performance Analysis. Available online: https://caxapa.ua/kompaniya-statti-teplovij-nasos-stav-najbilsh-zatrebuvanim-opaljuvalnim-obladnannjam-v-jevropi-v-2018-rotsi (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Kyiv City Military Administration Order of 29 September 2023, No. 760. Available online: https://kyivcity.gov.ua/npa/pro_vstanovlennya_tarifiv_na_teplovu_energiyu_virobnitstvo_teplovo_energi_transportuvannya_teplovo_energi_postachannya_teplovo_energi_poslugi_z_postachannya_teplovo_energi_i_postachannya_garyacho_vodi_komunalnomu_pidpriyemstvu_vikonavchogo_organu_k/ (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Tariffs. KP "Kharkiv Heating Systems". Available online: https://www.hts.com.ua/%d0%be%d1%81%d0%be%d0%b1%d0%be%d0%b2%d0%b8%d0%b9-%d0%ba%d0%b0%d0%b1%d1%96%d0%bd%d0%b5%d1%82/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Maevsky, O.; Kovalchuk, M.; Brodsky, Yu.; Stanytsina, V.; Artemchuk, V. Game-Theoretic Modeling in Regulating Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilodid, V.D. Total Energy Expenditures on Electricity Produced by Energy Facilities. Problems of General Energy 2017, 3, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, R. The Solarevolution: Much More with Way Less, Right Now—The Disruptive Shift to Renewables. Energies 2016, 9, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliarenko, O.; Horskyi, V.; Stanytsina, V.; Bogoslavska, O.; Kuts, H. An Improved Approach to Evaluation of the Efficiency of Energy Saving Measures Based on the Indicator of Products Total Energy Intensity. In: Babak, V.; Isaienko, V.; Zaporozhets, A. (eds) Systems, Decision and Control in Energy I. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control 2020, 298. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).