1. Introduction

The

Circoviridae family consists of small icosahedral viruses without an envelope protein, and they feature a circular single-stranded DNA genome of 1600–2200 nucleotides in length. The

Circoviridae family consists of two genera, namely

Circovirus and

Cyclovirus (Virus Taxonomy: 2023 Release;

https://ictv.global/taxonomy, accessed on 13 November 2024). Several viruses in the

Circoviridae family cause disease in mammals and birds, and in particular, porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) has significantly impacted the livestock industry. PCV2 causes several conditions collectively termed porcine circovirus-associated diseases (PCVADs), including postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome, porcine respiratory disease complex, and porcine dermatitis nephropathy syndrome [

1,

2,

3,

4]. By contrast, porcine circovirus type 1 (PCV1), discovered in the porcine kidney-derived PK-15 cell line approximately 50 years ago, is considered nonpathogenic [

1]. PCV3 was also identified in the US in 2015 in a case of porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome (PDNS) [

5,

6], followed by the detection of PCV4 in pigs with signs of PDNS in China in 2019 [

7]. Thus, porcine circoviruses are of high economic importance to the livestock industry.

Beak and feather disease virus (BFDV) is an important pathogen in parrots with psittacine beak and feather disease, and it has been present in Australia for at least 10 million years [

8]. This virus significantly hampers conservation efforts for endangered parrots, causing feather damage, abnormal beak formation, and immunodeficiency [

9]. Canine circovirus (CanineCV) causes severe symptoms in the presence of other pathogens, such as co-infection of CanineCV and canine parvovirus type 2 in puppies [

10]. In addition, columbid circovirus (pigeon circovirus: PiCV) poses the greatest health and economic damage in young racing pigeons, inducing young pigeon disease syndrome with a secondary infection attributable to immunosuppression [

11]. Therefore, immunosuppression is a common pathogenic feature of circovirus infections.

However, the molecular mechanism of immunosuppression following circovirus infection is largely unknown. Previous studies indicated that the PCV2 capsid protein inhibits type I interferon (IFN) signaling [

12]. Specifically, it suppresses IFN-β promoter activity driven by stimulator of interferon genes, TANK-binding kinase 1, and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) [

13], and it reduces phosphorylated IRF3 protein levels in the nucleus [

14,

15,

16]. Supporting the mechanism of action, PCV2 capsid protein localizes in the nucleus [

17,

18]. However, whether these phenotypes are PCV2-specific remains unclear.

In this study, we investigated whether these functions are conserved across Circoviridae family capsid proteins. Our results demonstrated that although nuclear localization of the capsid protein is conserved among the Circoviridae family, the effect on IFN-β signaling differs among the virus species. These findings highlight the complex and divergent effects of Circoviridae family capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmids

The IFN-Beta_pGL3 plasmid was a gift from Nicolas Manel (plasmid #102597;

http://n2t.net/addgene:102597; accessed on 13 November 2024; RRID: Addgene_102597, Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA). pCAGGS–humanTRIF–Myc [

19] and pCAGGS–pigTRIF–Myc [

20], in which the pCAGGS vector (Addgene) encoded Myc–tagged human TRIF or pig TRIF, respectively, and the pRL–TK vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA, Cat# E2241) were used to evaluate IFN-β signaling. The coding sequence of the

Circoviridae capsid plasmids was synthesized according to the amino acid sequences deposited in GenBank with codon optimization to human cells (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA, USA). The synthesized DNA sequence is summarized in

Table S1. Synthesized DNA was cloned into the pCAGGS–DsRed–monomer plasmid [

21], which was prelinearized with

AgeI–HF (New England Biolabs (NEB), Ipswich, MA, USA, Cat# R3552L) and

NheI–HF (NEB, Cat# R3131L) using an In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan, Cat# Z9633N). The plasmids were amplified using NEB 5–alpha F’

Iq competent

Escherichia coli (NEB, Cat# C2992H) and extracted using the PureYield Plasmid Miniprep System (Promega, Cat# A1222). The sequences of all plasmids were verified using the SupreDye v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (M&S TechnoSystems, Osaka, Japan, Cat# 063001) with the Spectrum Compact CE System (Promega).

To generate pCAGGS–DsRed–monomer plasmids expressing capsid proteins with deletions or chimeric capsid proteins between PCV2 and BFDV capsid proteins, each fragment was generated with PrimeSTAR® GXL DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa, Cat# R050A). The primers used for PCR amplification and the amino acid sequences are listed in

Table S2 and

Table S3, respectively. The amplified fragments were cloned into the pCAGGS–DsRed–monomer plasmid and the sequences of all plasmids were verified as previously described.

2.2. Cell Culture

Lenti-X 293T cells (TaKaRa, Cat# Z2180N) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan, Cat# 08458-16) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA, Cat# SH30396) and 1× penicillin–streptomycin (Nacalai Tesque, Cat# 09367-34) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

2.3. Nuclear Localization of Circoviridae Capsid Proteins

Lenti-X 293T cells were seeded into a 24-well plate (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan, Cat# 630-28441) at 1.25 × 105 cells/well, cultured overnight, and transfected with 500 ng of pCAGGS–DsRed–monomer Circoviridae capsid plasmids using TransIT-293 Transfection Reagent (TaKaRa, Cat# V2700) in Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat# 31985062). NucBlue Live ReadyProbes Reagent (Hoechst 33342, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# R37605) was used to probe the nucleus. The localization of Circoviridae capsid proteins was evaluated 48 h after transfection using the EVOS M7000 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.4. IFN-β Luciferase Reporter Assay

Lenti-X 293T cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Cat# 63528511) at 3 × 104 cells/well, cultured overnight, and co-transfected with 50 ng of pCAGGS–DsRed–monomer Circoviridae capsid plasmids, 2.5 ng of IFN-Beta_pGL3 plasmid, 45 ng of pRL–TK plasmid, and 2.5 ng of pCAGGS–humanTRIF–Myc or pCAGGS–pigTRIF–Myc plasmid using TransIT-293 Transfection Reagent. Two days after transfection, the luciferase activity was measured using a Dual-Glo Luciferase assay (Promega, Cat# E2920) and a GloMax Explorer Multimode Microplate Reader to investigate the effect of Circoviridae capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling. Firefly luciferase activities were normalized according to Renilla luciferase activities. The percentage relative activities were calculated by comparing the normalized luciferase data of Circoviridae capsid protein plasmid-transfected cells and empty plasmid-transfected cells. The assays were repeated at least three times. The data are presented as the mean ± SD of one representative experiment.

2.5. Western Blotting

The cellular pellets of Lenti-X 293T cells were lysed with 2× Bolt LDS sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# B0008) containing 2% β-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA, Cat# 1610710) and incubated at 70°C for 10 min. The expression of

Circoviridae capsid proteins was assessed using SimpleWestern Abby (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA) with mouse monoclonal anti–DsRed–monomer antibody (clone OTI4c8, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# TA180084) and Anti–Mouse Detection Module (ProteinSimple, Cat# DM-002). The amount of input protein was measured using the Total Protein Detection Module (ProteinSimple, Cat# DM-TP01). The predicted sizes of the DsRed–monomer

Circoviridae capsid proteins were calculated according to the Protein Molecular Weight website (

https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms/prot_mw.html, accessed on 13 November 2024).

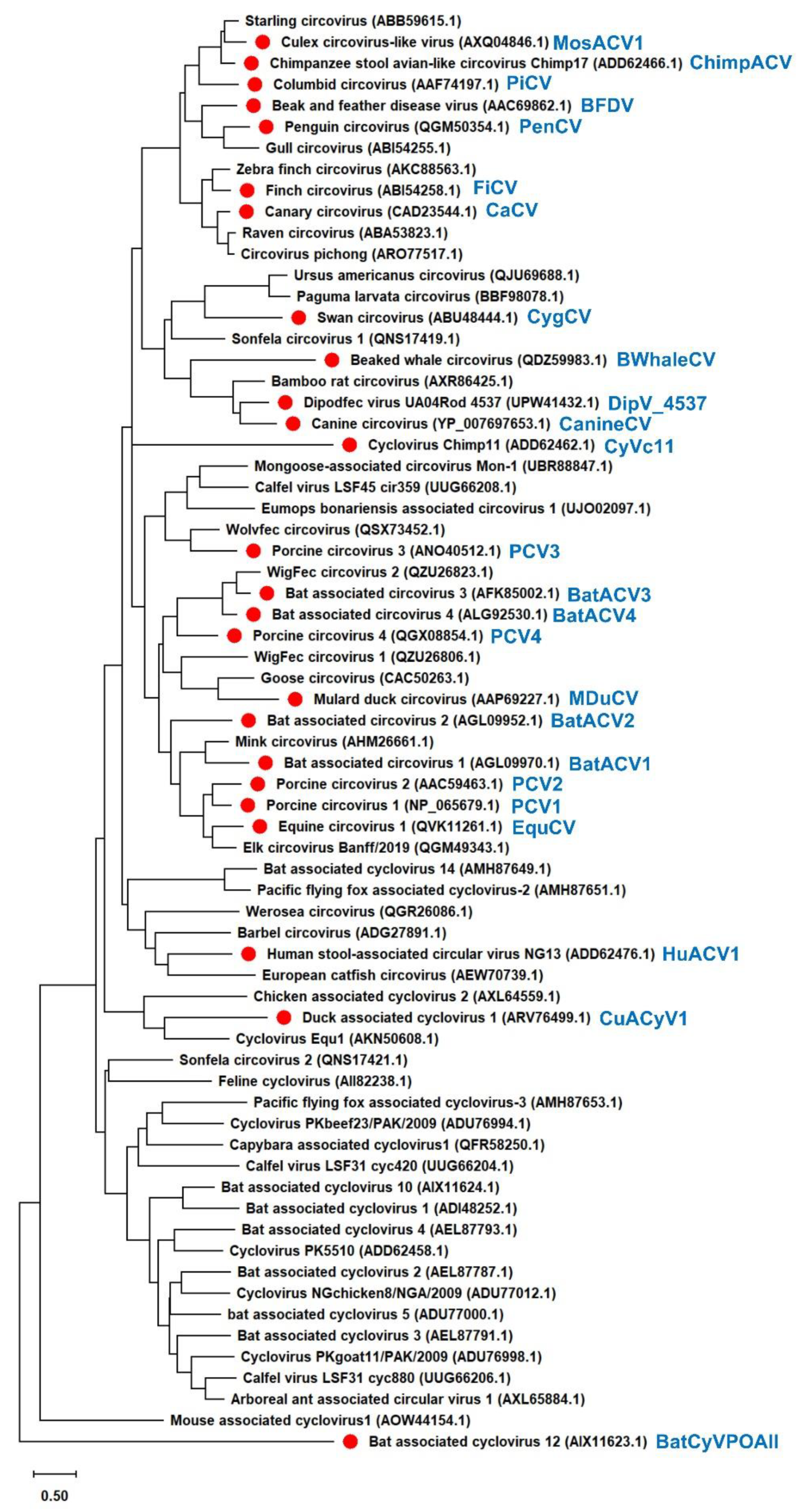

2.6. Phylogenic Analysis of Circoviridae Capsid Proteins

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using 68

Circoviridae capsid protein sequences obtained from GenBank. The tree was created using the MUSCLE algorithm within MEGA X software [

22]. We subsequently constructed a phylogenetic tree from the aligned amino acid sequences obtained from public databases. Evolutionary analysis was performed using the maximum likelihood and neighbor-joining methods and employing the Jones–Taylor–Thornton matrix-based model.

2.7. Calculation of Capsid Identity in the Circoviridae Family among Animal Species

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Unless stated otherwise, the data are presented as the mean ± SD of six measurements from a single assay, reflecting the results from at least three independent experiments. Variations in the relative values between the circovirus capsid proteins and the plasmid encoding only DsRed–monomer were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A statistically significant difference was indicated by p ≤0.05.

4. Discussion

Immunosuppression, a prevalent pathology in Circoviridae infections, was the focus of our study. We investigated the conservation of several functions of Circoviridae capsid proteins. Our findings revealed significant divergence in their effects of different virus species on IFN signaling. This discovery sheds new light on the complex interactions within the Circoviridae family.

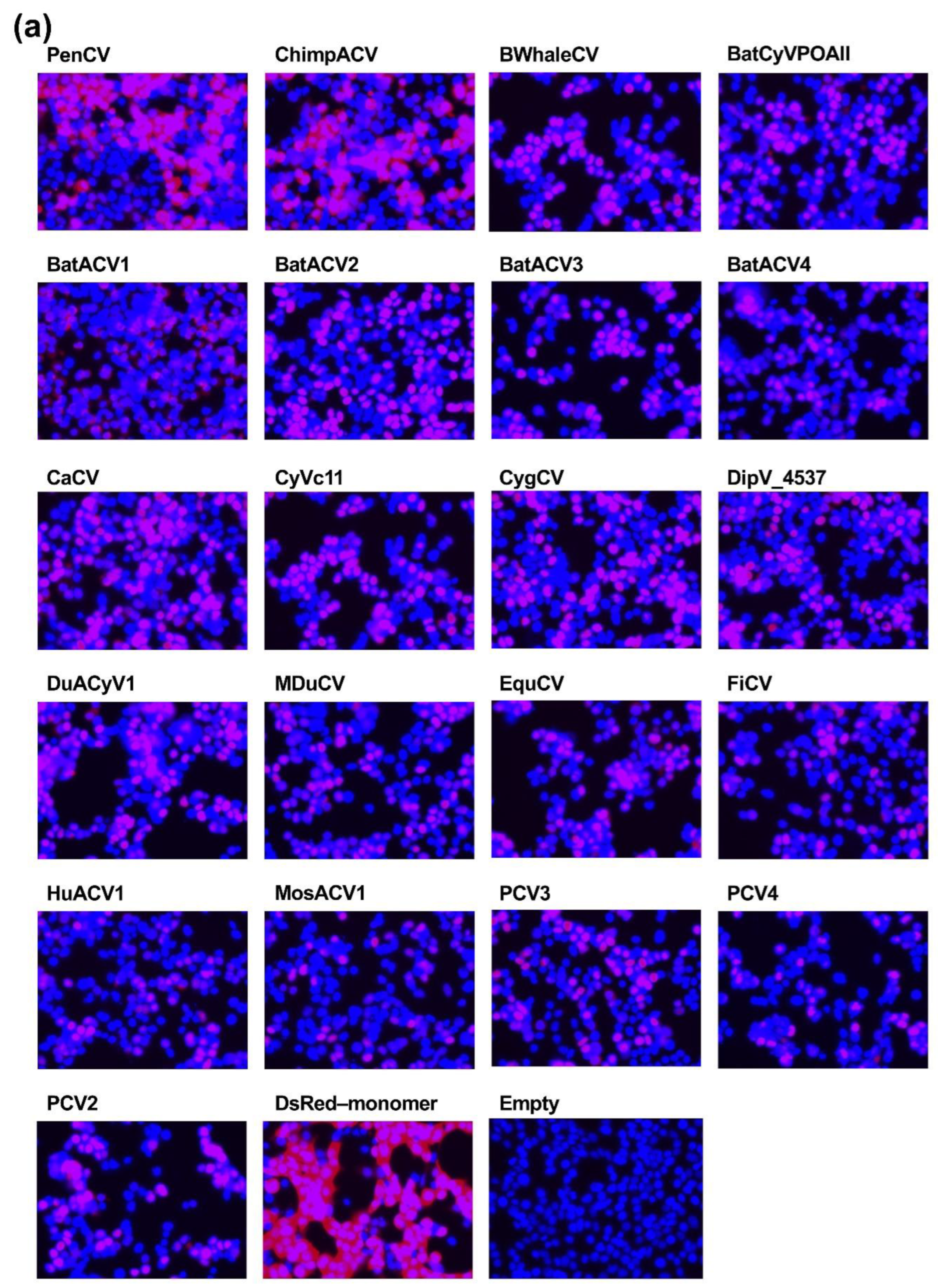

Our research began with a comprehensive examination of the intracellular localization of five

Circoviridae capsid proteins derived from PCV1, PCV2, CanineCV, PiCV, and BFDV. We found that all capsid proteins consistently localized to the nucleus (

Figure 1b). This thorough analysis was expanded using capsid proteins from genetically distant viruses within the

Circoviridae family (

Figure 3). The results illustrated that all 31

Circoviridae capsid proteins localized to the nucleus (

Figure 4a), further confirming the conserved nuclear localization of the capsid proteins.

The results using deletion mutants of the PCV2 capsid protein illustrated that nuclear localization was slightly weakened when the N-terminal 50 amino acids were deleted (

Figure 2d). This result is consistent with a previous study revealing that the N-terminal 41 amino acids of the PCV2 capsid protein are associated with nuclear localization [

17]. Contrarily, the BFDV(del191–) protein exhibited weaker nuclear localization (

Figure 2d), suggesting that the C-terminal region is responsible for nuclear localization of the BFDV capsid protein. However, because the impact of the deletion in these regions was partial (

Figure 2d), it is possible that other domains and/or motifs of the capsid proteins were also involved in their nuclear localization. Thus, it will be intriguing to test the impact of these regions on the localization of other

Circoviridae capsid proteins. Further studies can address these points.

Next, we examined the effects of

the Circoviridae capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling, specifically examining five

Circoviridae capsid proteins derived from PCV1, PCV2, CanineCV, PiCV, and BFDV (

Figure 1c). PCV1 and PCV2 capsid proteins suppressed IFN-β signaling. Although the phenotype of the PCV2 capsid protein was consistent with previous findings [

16], the BFDV capsid protein enhanced IFN-β signaling.

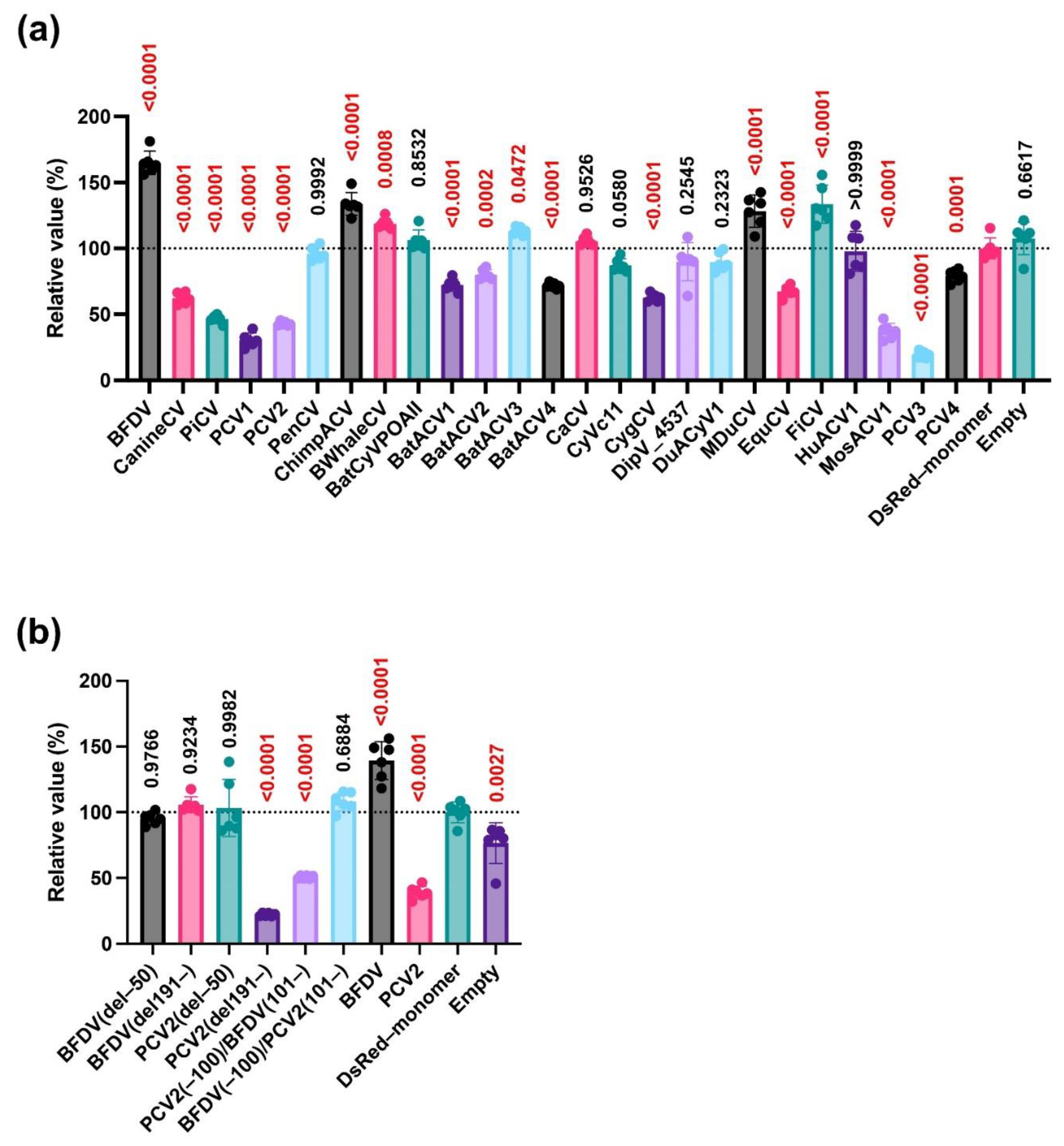

Our analysis using deletion mutants of capsid proteins suggested that both the N- and C-termini of the BFDV capsid protein are required for its enhancing effect (

Figure 2e). In the case of the PCV2 capsid protein, the C-terminus appeared dispensable for its inhibitory effects (

Figure 2f). Further analysis using a chimeric protein between PCV2 and BFDV capsid proteins demonstrated that the BFDV(–100)/PCV2(101–) protein had an enhancing effect, albeit weaker than that of the BFDV(WT) protein (

Figure 2g). This suggests that the effect of the BFDV capsid protein was dominant over that of the PCV2 capsid protein. Furthermore, these results suggest that whereas the PCV2 capsid protein does not require the C-terminal region to suppress IFN-β signaling, both the N- and C-termini are involved in the IFN-β signaling-stimulating effect of the BFDV capsid protein, and the C-terminal region of the PCV2 capsid protein can complement the activity of its C-terminal region.

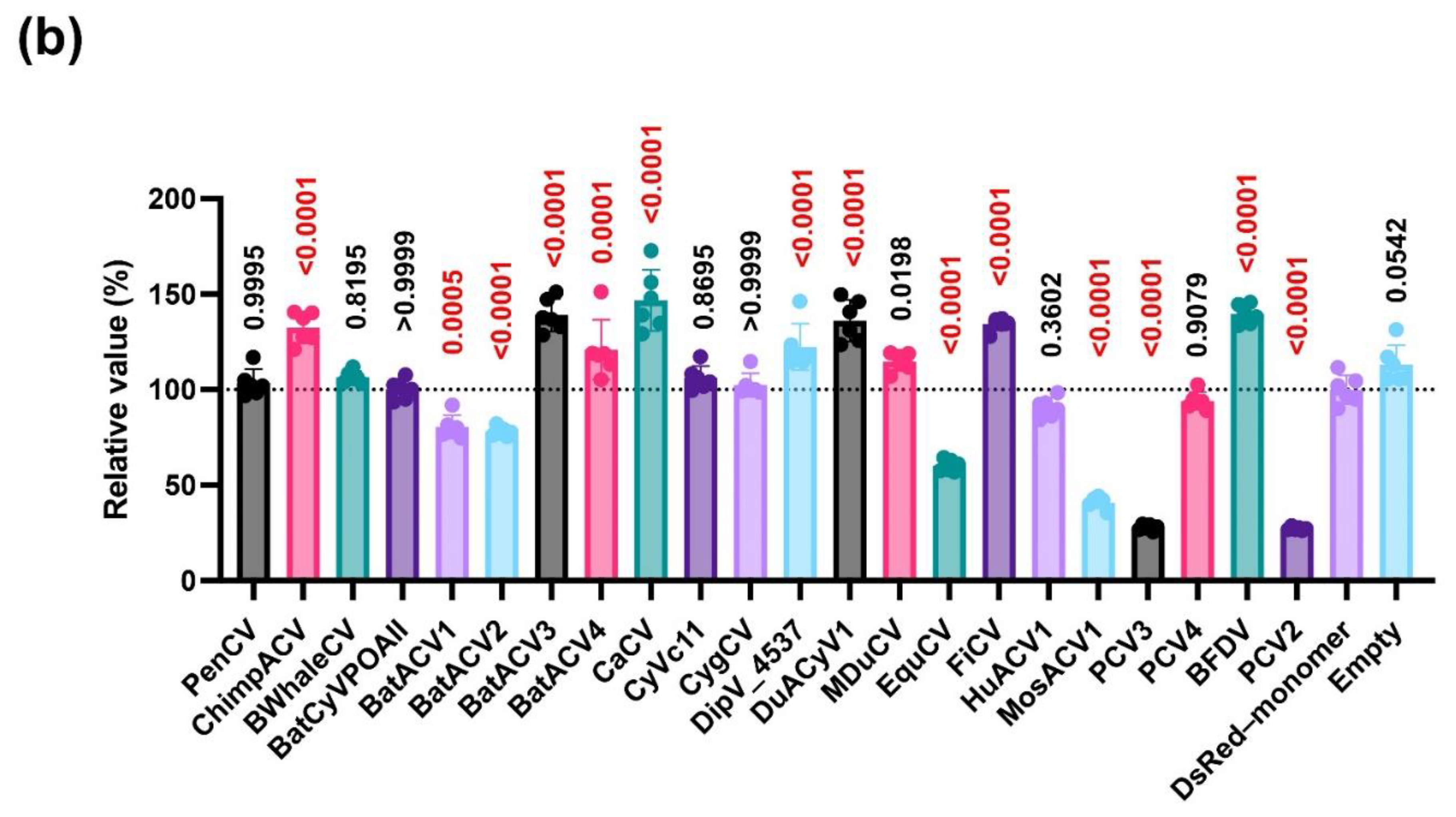

Our experiment using 25

Circoviridae capsid proteins revealed that the effects of these proteins on IFN-β signaling varied greatly among the virus species (

Figure 4b). Similarly as the PCV2 capsid protein (

Figure 1c), several

Circoviridae capsid proteins such as BatACV2, equine circovirus,

Culex circovirus, and PCV3 capsid proteins suppressed IFN-β signaling (

Figure 1c and Figure 4b). Contrarily, capsid proteins from chimpanzee circovirus, BatACV3, canary circovirus, dipodfec virus, and FiCV, especially the BFDV capsid protein, markedly enhanced IFN-β signaling (

Figure 1c and Figure 4b).

Among PCV1, PCV2, PCV3, and PCV4, only the PCV4 capsid protein failed to suppress IFN-β signaling (

Figure 4b). Given that the PCV3 capsid protein was more distinct from the PCV2 capsid protein than the PCV4 capsid protein in the phylogenetic tree (

Figure 3), this result suggests that the function of IFN-β signaling is independent of the genetic similarity of

Circoviridae capsid proteins. Similarly, in the case of the bat-derived circovirus capsid protein, whereas BatACV1 and BatACV2 capsid proteins suppressed IFN-β signaling (

Figure 4b), an enhancing effect was observed for the BatACV3 capsid protein, and no effect was observed for the BatACV4 capsid protein. This finding supports our hypothesis that the effects of

Circoviridae capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling are independent of genetic similarity.

When we focused on the

Circoviridae capsid proteins that enhanced IFN-β signaling (

Figure 4b), the chimpanzee circovirus, canary circovirus, BFDV, and FiCV capsid proteins were found to be genetically similar (

Figure 3). However, PiCV, which is genetically similar to BFDV, oppositely suppressed IFN-β signaling (

Figure 4b). These findings suggest that the effect of capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling is not associated with the genetic distance.

This study had several limitations. First, we were unable to identify the region(s) responsible for the divergent effects of

Circoviridae capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling. Second, we did not elucidate the correlation between the suppressing effect of capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling and clinical severity. Because both PCV2 and BFDV infections induce immunosuppression, other viral proteins of BFDV might be responsible for its immunosuppressive effect. These points should be investigated in future studies. Third, we used a luciferase-based reporter system in human-derived Lenti-X 293-T cells to test the effect on IFN-β signaling. Although similar results were obtained using both human- and pig-derived TRIF proteins (

Figure 4b and Figure 5a), we must use cell lines derived from other animals, including pigs and parrots, to clarify the significance of PCV2 and BFDV capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling.

In summary, our study revealed the diverse effects of Circoviridae capsid proteins on IFN-β signaling, finding that these effects were virus species-specific. This highlights the intricate pathophysiology induced by viruses in the Circoviridae family. These findings both deepen our understanding of these viruses and provide a foundation for future research to develop effective treatments for animals infected by Circoviridae viruses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.K., and A.S.; methodology, A.H.K., A.C., R.S.R., and A.S.; formal analysis, A.H.K., C.-Y.H., Z.-Y.L., H.-Z.H., A.C., R.S.R., K.-P.C., and A.S.; investigation, A.H.K., C.-Y.H., Z.-Y.L., H.-Z.H., A.C., and R.S.R.; writing – original draft, A.H.K.; writing – review & editing C.-Y.H., Z.-Y.L., H.-Z.H., A.C., R.S.R., K.-P.C., and A.S.; supervision, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.