Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. S1133 Inoculum Preparation and Dose Determination

2.3. Virus Inoculation

2.4. Quantitative PCR for Viral Load

2.5. RNA Sequencing

2.6. Read Alignment, Principal Component and Differential Expression Analyses

2.7. Pathway Annotation and Comparison

2.8. Protein-protein Interaction (PPI) Analysis

2.9. Isoform Switch Analysis

3. Results

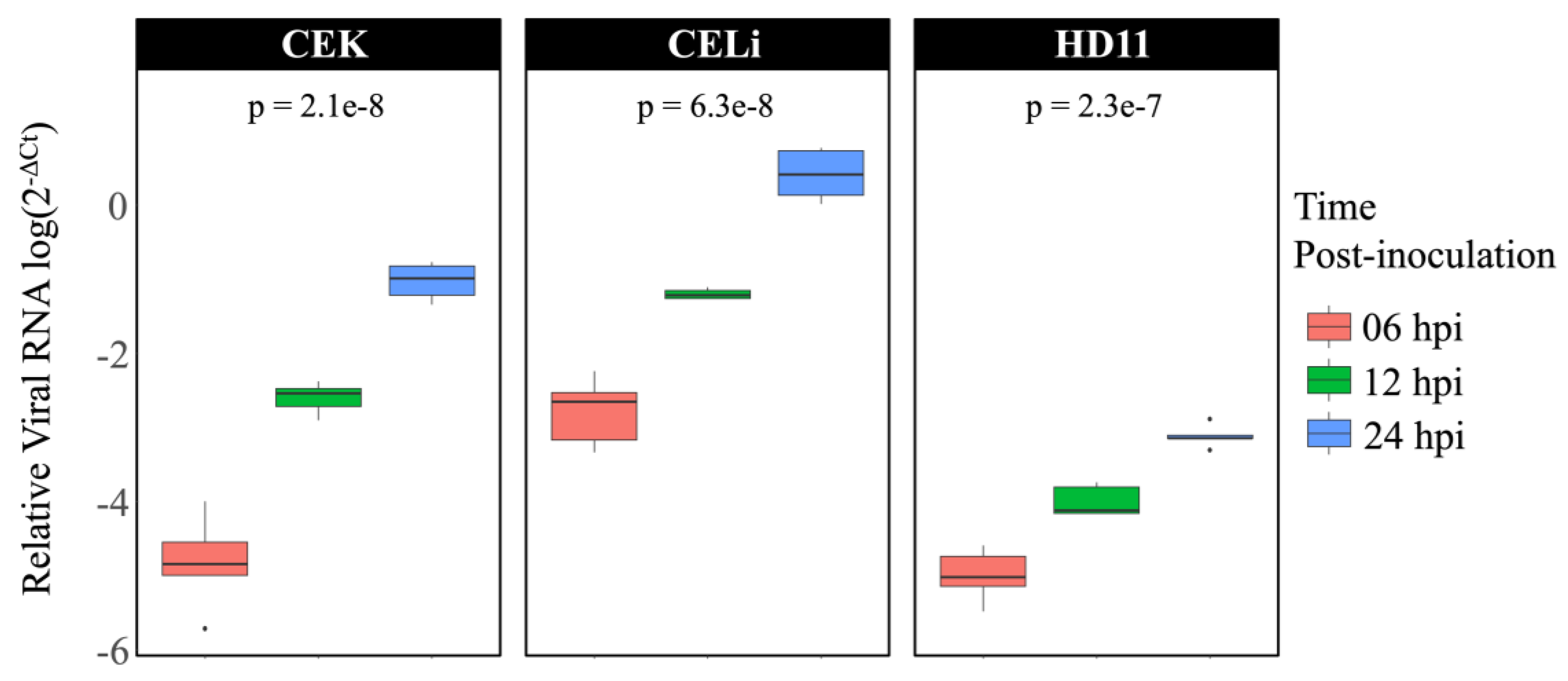

3.1. Avian Reovirus Replication in Different Cell Types

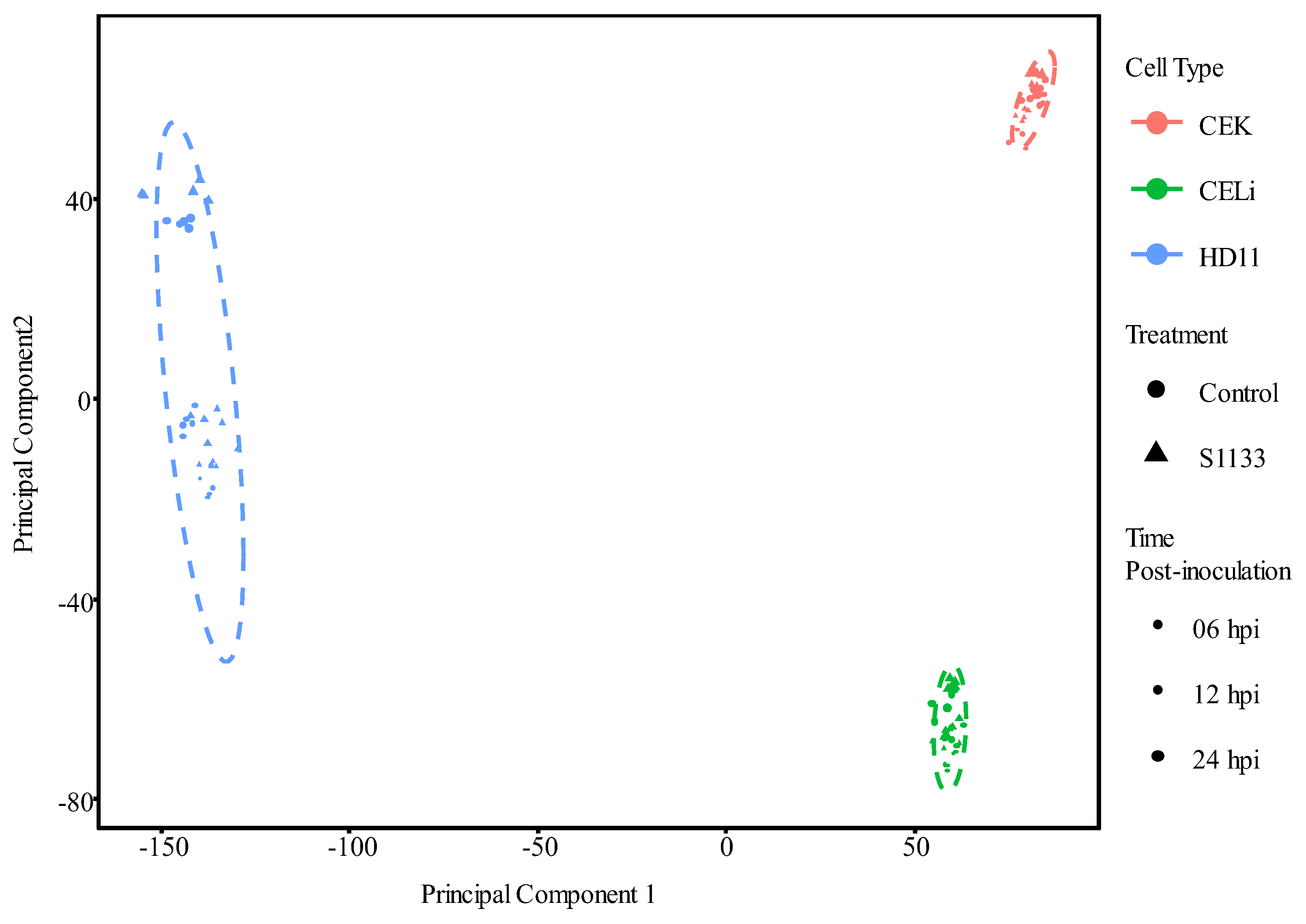

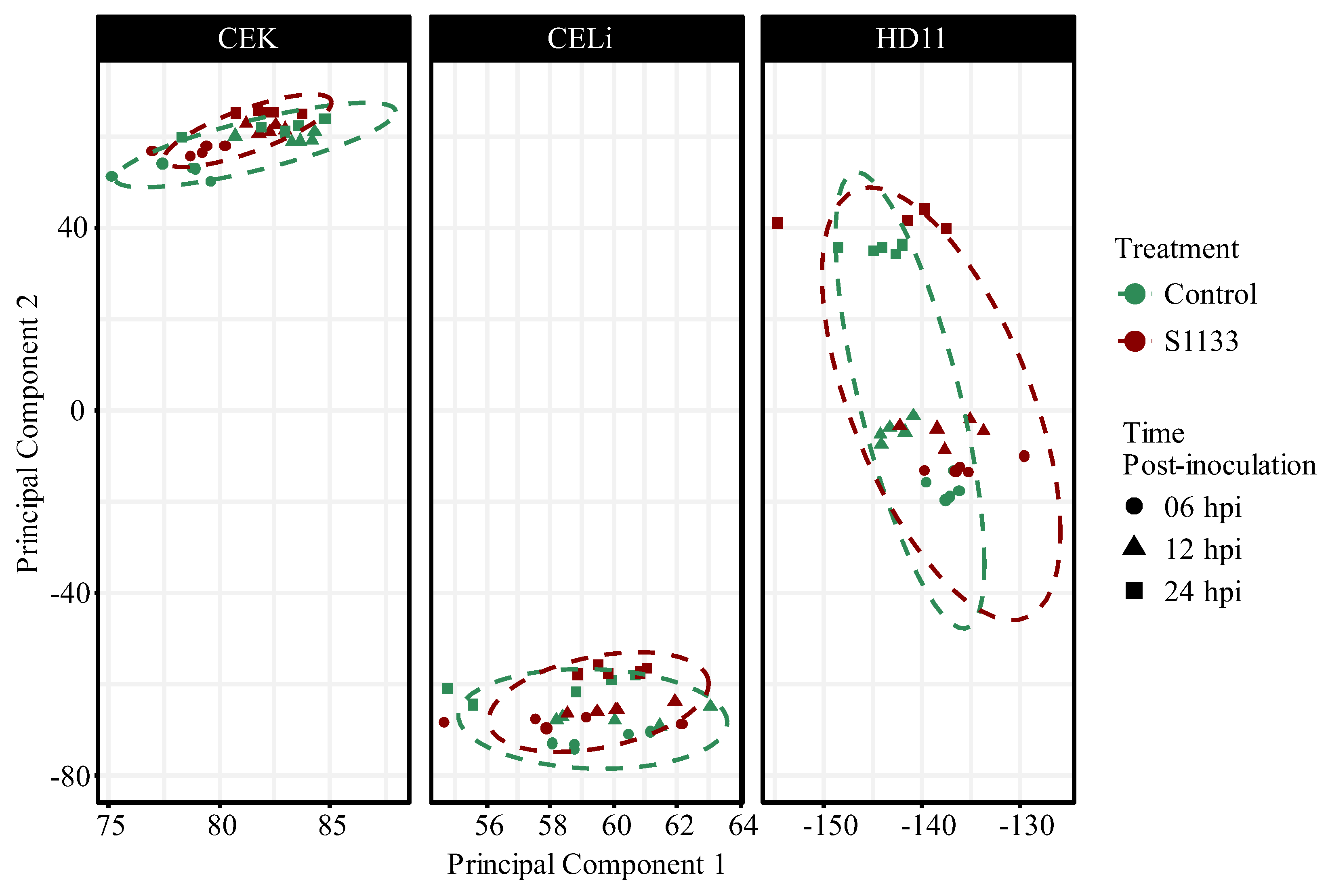

3.2. Principal Component Analysis of Gene Expression

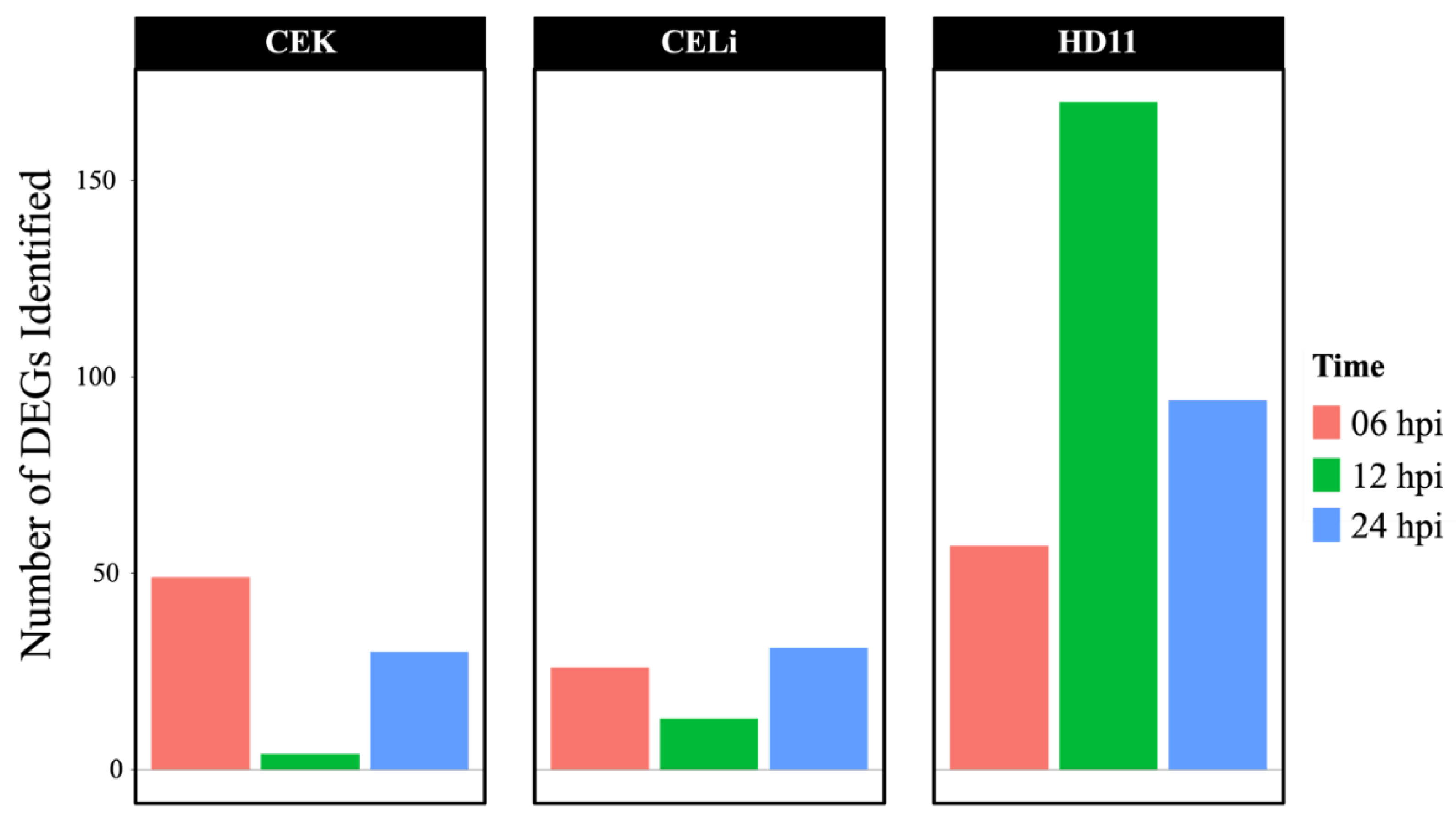

3.3. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

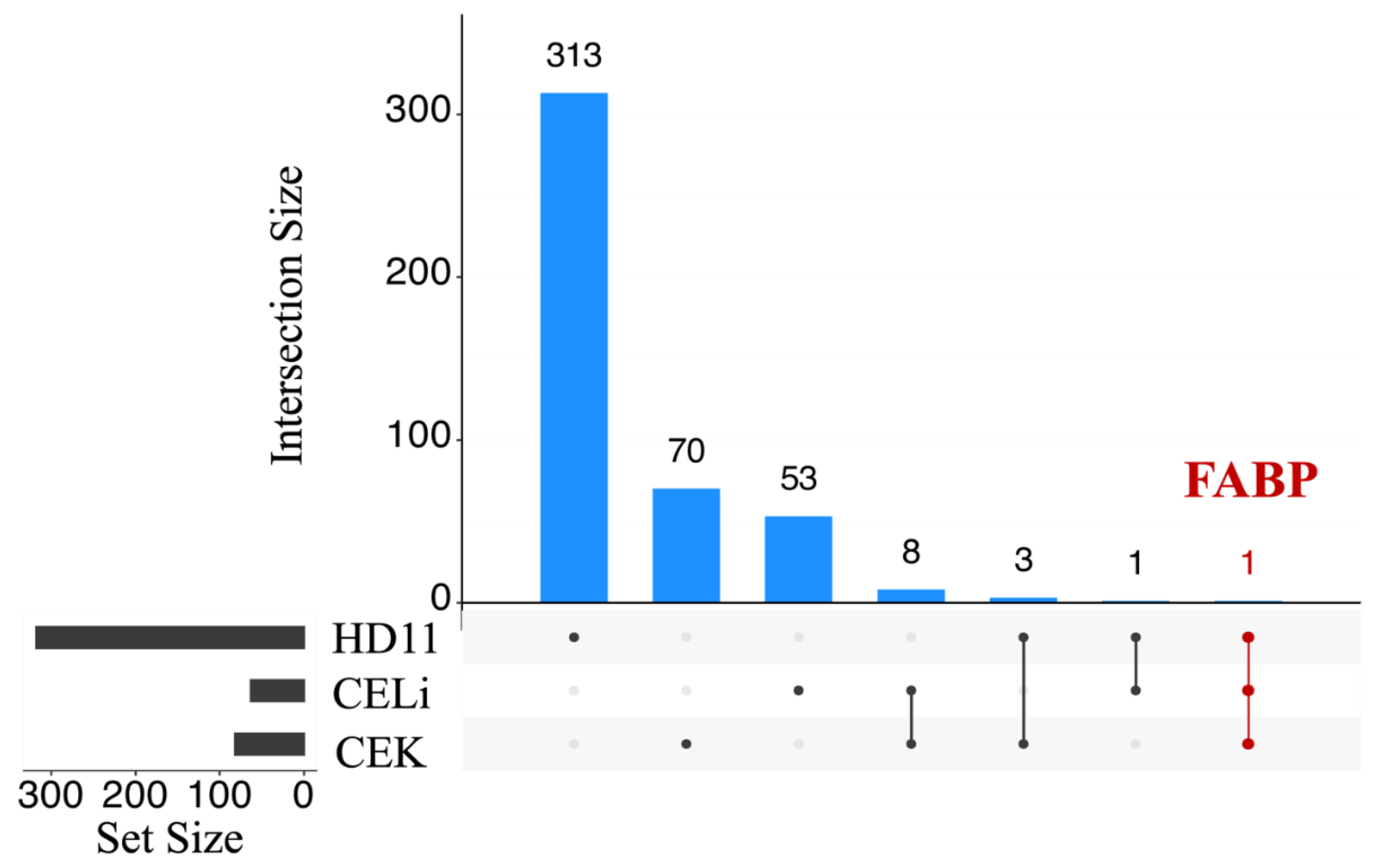

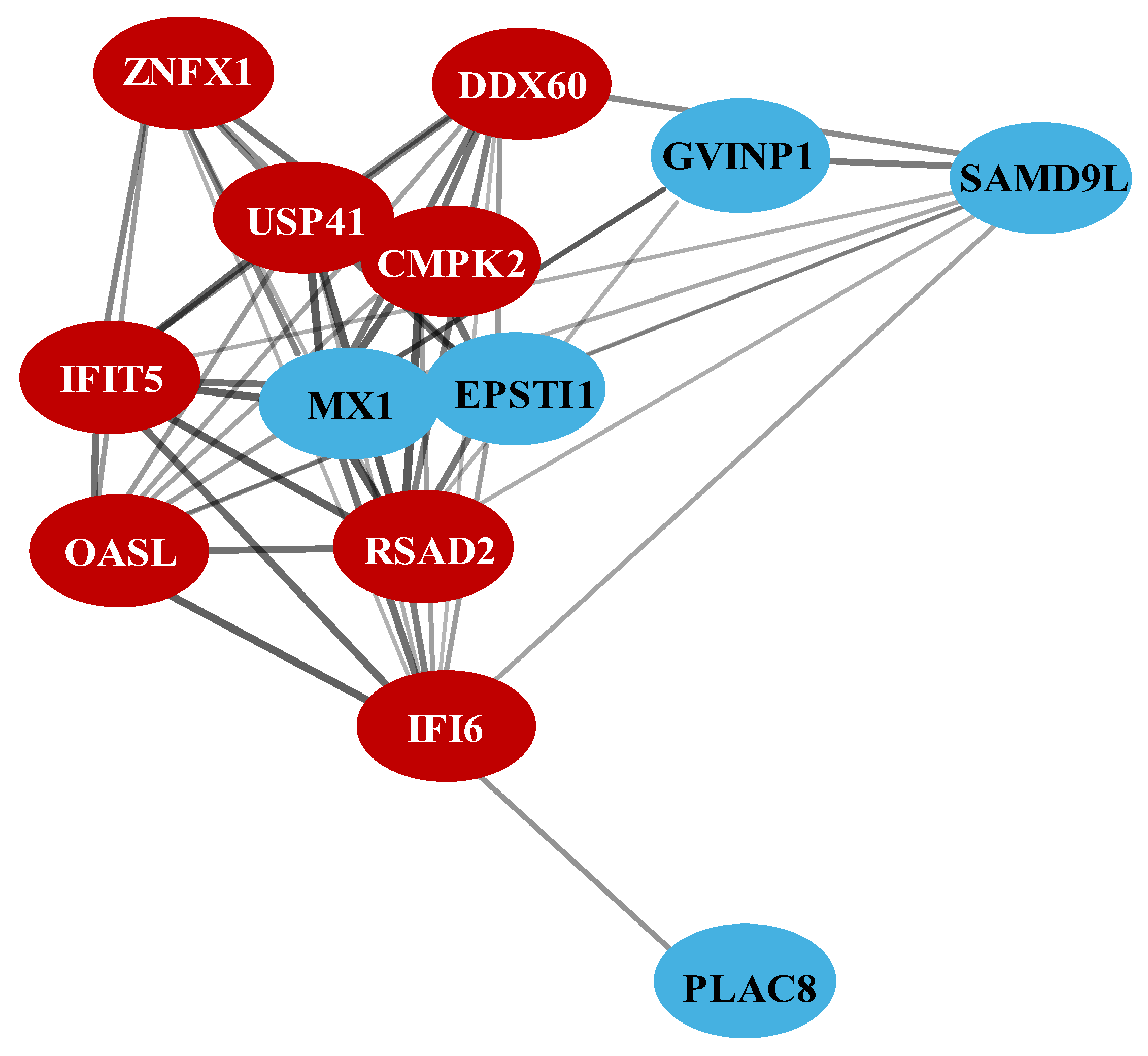

3.4. Protein-Protein Interaction Network

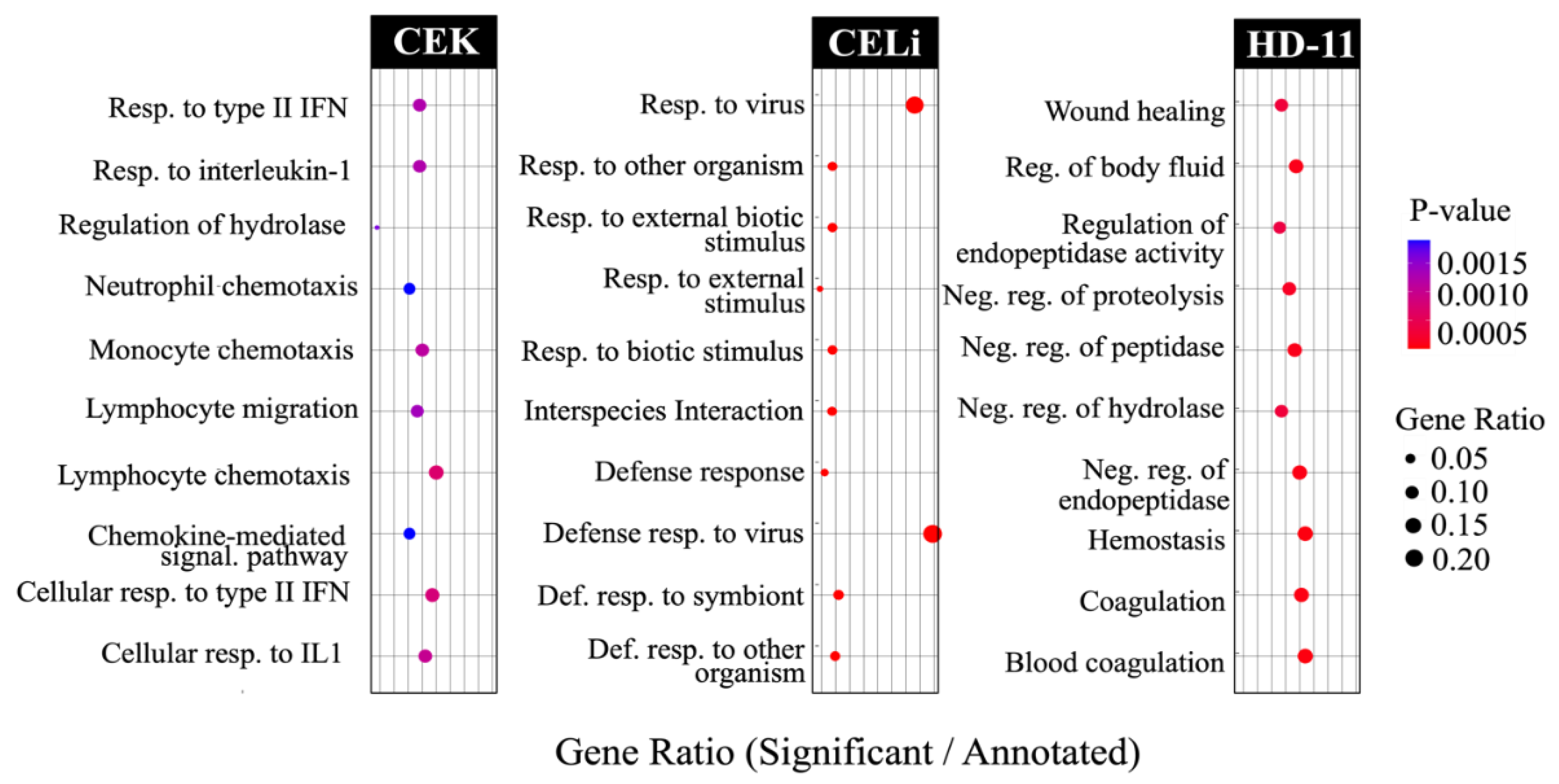

3.5. Pathway Enrichment: Gene Ontology Analysis

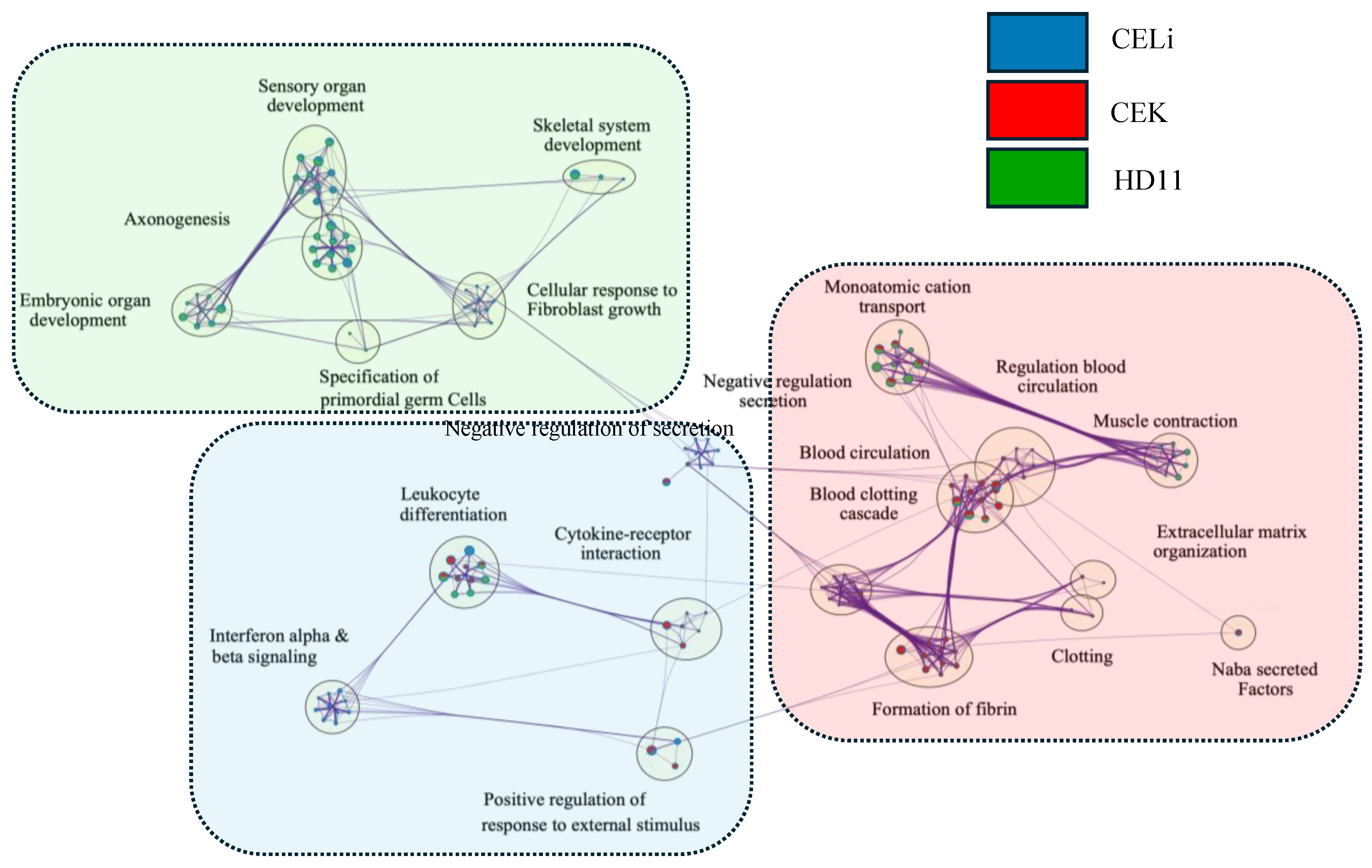

3.6. Network Analysis of Pathways

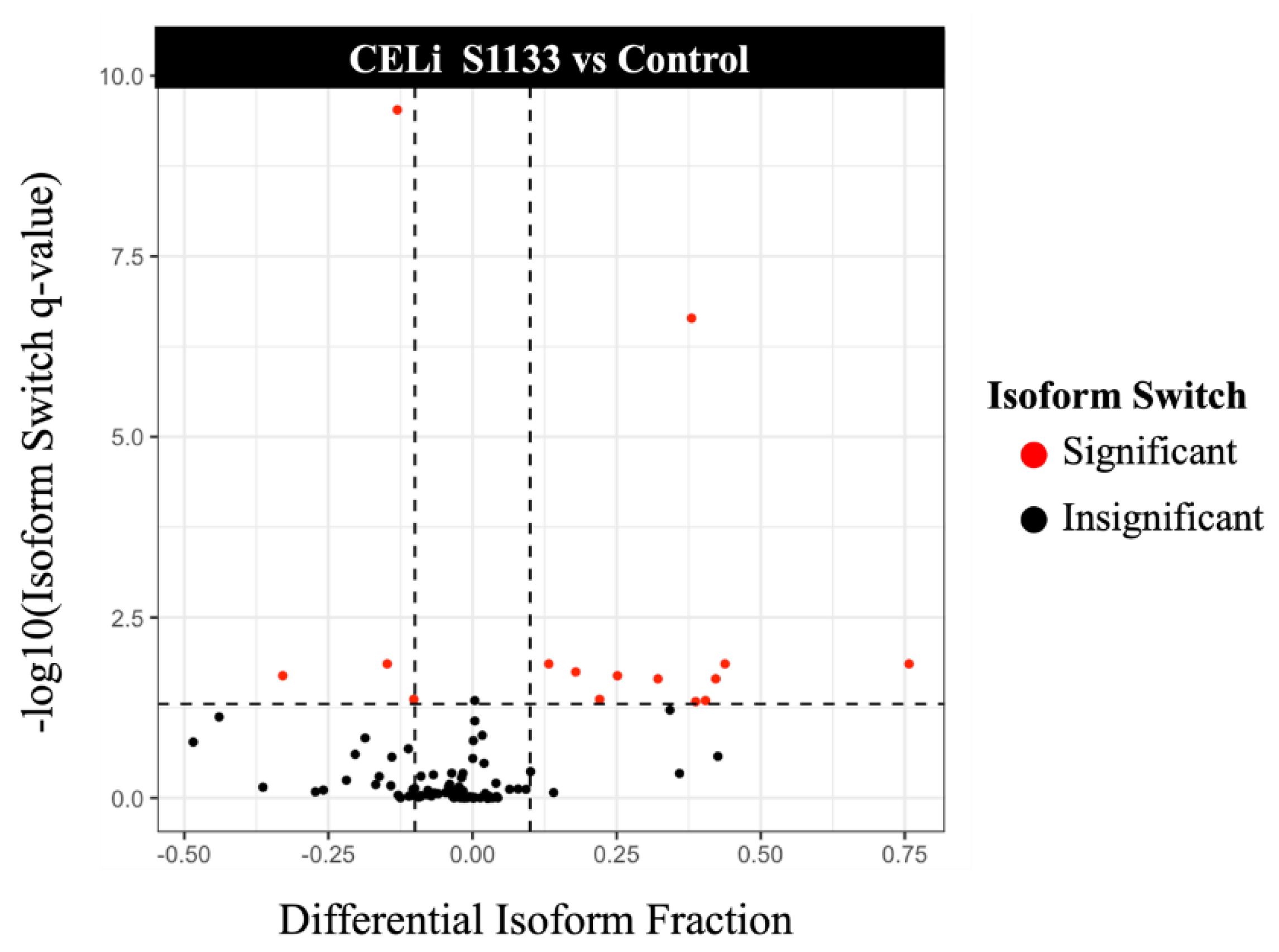

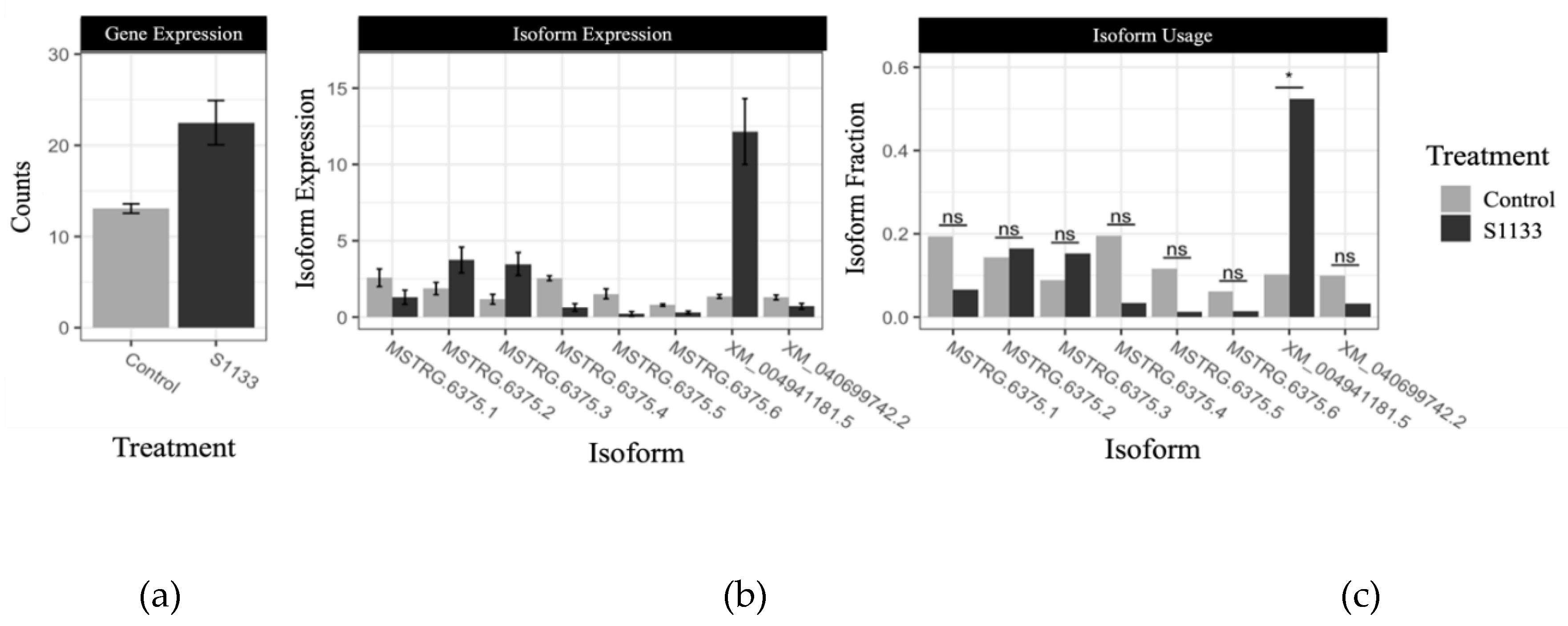

3.7. Isoform Switching Analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovács, E.; Varga-Kugler, R.; Mató, T.; Homonnay, Z.; Tatár-Kis, T.; Farkas, S.; Kiss, I.; Bányai, K.; Palya, V. Identification of the main genetic clusters of avian reoviruses from a global strain collection. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 9, 1094761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, K.N.; Glisson, J.R. Economic impact of a documented case of reovirus infection in broiler breeders. Avian Dis. 1992, 36, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, D. Incidence and economic impact of reovirus in the poultry industries in the United States. Avian Dis. 2022, 66, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N.O.; Kerr, K.M. Some characteristics of an avian arthritis viral agent. Avian Dis. 1966, 10, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N.O.; Solomon, D.P. A natural outbreak of synovitis caused by the viral arthritis agent. Avian Dis. 1968, 12, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, J.K.; Sterner, F.J.; Botts, S.; Lee, K.P.; Margolin, A. In vitro and in vivo characterization of avian reoviruses. I. pathogenicity and antigenic relatedness of several avian reovirus isolates. Avian Dis. 1989, 33, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibenge, F.S.B.; Wilcox, G.E. Tenosynovitis in chickens. 1983, 53, 431–444.

- Mandelli, G.; Rampin, T.; Finazzi, M. Experimental reovirus hepatitis in newborn chicks. Vet. Pathol. 1978, 15, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-R.; Kim, S.-W.; Shang, K.; Park, J.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Jang, H.-K.; Wei, B.; Cha, S.-Y.; Kang, M. Avian reoviruses from wild birds exhibit pathogenicity to specific pathogen free chickens by footpad route. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 844903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.F.; Kulkarni, A.; Fletcher, O. Reovirus infections in young broiler chickens. Avian Dis. 2013, 57, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.F.; Kulkarni, A.; Fletcher, O. Myocarditis in 9- and 11-day-old broiler breeder chicks associated with a reovirus infection. Avian Dis. 2012, 56, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.C. Reoviruses from chickens with hydropericardium. Vet. Rec. 1976, 99, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spradbrow, P.B.; Bains, B.S. Reoviruses from chickens with hydropericardium. Aust. Vet. J. 1974, 50, 179–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, R.D.; Boyle, C.R.; Maslin, W.R.; Magee, D.L. Attempts to reproduce a runting/stunting-type syndrome using infectious agents isolated from affected mississippi broilers. Avian Dis. 1997, 41, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelima, S.; Ram, G.C.; Kataria, J.M.; Goswami, T.K. Avian reovirus induces an inhibitory effect on lymphoproliferation in chickens. Vet. Res. Commun. 2003, 27, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cui, Z.; Sun, A.; Sun, S.H. Influence of avian reovirus infection on the bursa and immune-reactions in chickens. Wei sheng wu xue bao. 2007, 47 3, 492–497. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.C.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Hu, X.M.; Wei, L.; Zhang, X.R.; Wu, Y.T. IFI16 plays a critical role in avian reovirus induced cellular immunosuppression and suppresses virus replication. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103 4, 103506. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, S.S.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, X.R.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Z.Z.; Hu, M.Z.; Yang, R.; Sun, C.L.; Wu, Y.T. Avian reovirus triggers autophagy in primary chicken fibroblast cells and vero cells to promote virus production. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrada, L.; Bodelón, G.; Viñuela, J.; Benavente, J. Avian reoviruses cause apoptosis in cultured cells: Viral uncoating, but not viral gene expression, is required for apoptosis induction. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 7932–7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.S.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.R.; Wu, Y.T. Transcriptome analysis of avian reovirus-mediated changes in gene expression of normal chicken fibroblast DF-1 cells. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, R.; Luo, D.; Li, K.; Qi, X.L.; Liu, C.J.; Zhang, Y.P.; Cui, H.Y.; Wang, S.Y.; Gao, Y.L.; et al. Avian reovirus σA protein inhibits type I interferon production by abrogating interferon regulatory factor 7 activation. J. Virol. 2022, 97, e01785–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Costas, J.; González-López, C.; Vakharia, V.N.; Benavente, J. Possible involvement of the double-stranded RNA-binding core protein σa in the resistance of avian reovirus to interferon. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lostalé-Seijo, I.; Martínez-Costas, J.; Benavente, J. Interferon induction by avian reovirus. Virology 2016, 487, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xie, L.J.; Xie, Z.X.; Wan, L.J.; Huang, J.L.; Deng, X.W.; Xie, Z. qin; Luo, S.S.; Zeng, T.T.; Zhang, Y.F.; et al. Dynamic changes in the expression of interferon-stimulated genes in joints of spf chickens infected with avian reovirus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 618124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Huang, T.D.; Wan, L.J.; Ren, H.Y.; Wu, T.; Xie, L.J.; Luo, S.S.; Li, M.; Xie, Z.Q.; Fan, Q.; et al. Transcriptomic and translatomic analyses reveal insights into the signaling pathways of the innate immune response in the spleens of SPF chickens infected with avian reovirus. Viruses 2023, 15, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.N.; Eidson, C.S.; Fletcher, O.J.; Kleven, S.H. Viral tissue tropisms and interferon production in White Leghorn chickens infected with two avian reovirus strains. Avian Dis. 1983, 644–651. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, M.N.; Eidson, C.S.; Brown, J.; Kleven, S.H. Studies on interferon induction and interferon sensitivity of avian reoviruses. Avian Dis. 1983, 27, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, Z.; Alvarez-Narvaez, S.; Harrell, T.L.; Chowdhury, E.U.; Conrad, S.J.; Hauck, R. Retention of viral heterogeneity in an avian reovirus isolate despite plaque purification. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Lu, H.G. Whole genome alignment based one-step real-time RT-PCR for universal detection of avian orthoreoviruses of chicken, pheasant and turkey origins. Infect., Genet. Evol. 2016, 39, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.R.; Gu, J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one fastq preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. FeatureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. EdgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc., B (Methodol.) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Lex, A.; Gehlenborg, N.; Strobelt, H.; Vuillemot, R.; Pfister, H. UpSet: Visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graphics 2014, 20, 1983–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.R.; Lex, A.; Gehlenborg, N. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2938–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team RStudio: Integrated development environment for R 2024.

- R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing 2023.

- Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.D.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucera, M.; Isserlin, R.; Arkhangorodsky, A.; Bader, G.D. AutoAnnotate: A cytoscape app for summarizing networks with semantic annotations 2016.

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The string database in 2023: Protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.-C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazee, A.C.; Pertea, G.; Jaffe, A.E.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L.; Leek, J.T. Ballgown bridges the gap between transcriptome assembly and expression analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitting-Seerup, K.; Sandelin, A. IsoformSwitchAnalyzeR: Analysis of changes in genome-wide patterns of alternative splicing and its functional consequences. Bioinform. (Oxf. Engl.) 2019, 35, 4469–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Z. Tissue-specific transcriptomic responses to avian reovirus inoculation in ovo. 2025.

- Buckley, I.K.; Walton, J.R. A simple method for culturing chick embryo liver and kidney parenchymal cells for microscopic studies. Tissue Cell 1974, 6, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhu, P.H.; Shi, L.; Liu, Y.L.; Yang, X.J.; Yang, X. Single-nucleus transcriptome reveals cell dynamic response of liver during the late chick embryonic development. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Shen, P.C.; Su, B.S.; Liu, T.C.; Lin, C.C.; Lee, L.H. Avian reovirus replication in mononuclear phagocytes in chicken footpad and spleen after footpad inoculation. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2015, 79, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J.N. Interactions between avian phagocytic leukocytes and microbiological agents associated with avian tenosynovitis, Murdoch University, 1990.

- Mills, J.N.; Wilcox, G.E. Replication of four antigenic types of avian reovirus in subpopulations of chicken leukocytes. Avian Pathol. 1993, 22, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertile, T.L.; Sharma, J.M.; Walser, M.M. Reovirus infection in chickens primes splenic adherent macrophages to produce nitric oxide in response to T cell-produced factors. Cell. Immunol. 1995, 164, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertile, T.L.; Karaca, K.; Walser, M.M.; Sharma, J.M. Suppressor macrophages mediate depressed lymphoproliferation in chickens infected with avian reovirus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1996, 53, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guneratne, J.R.M.; Jones, R.C.; Georgiou, K. Some observations on the isolation and cultivation of avian reoviruses. Avian Pathol. 1982, 11, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.W.; Kemp, M.C. A comparative study of avian reovirus pathogenicity: Virus spread and replication and induction of lesions. Avian Dis. 1995, 39, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukert, P.D. Comparative sensitivities of embryonating chicken’s eggs and primary chicken embryo kidney and liver cell cultures to infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Dis. 1965, 9, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffer, K. In vitro and in vivo studies with an avian reovirus derived from a temperature-sensitive mutant clone. Avian Dis. 1984, 28, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bülow, V.; Klasen, A. Effects of avian viruses on cultured chicken bone-marrow-derived macrophages. Avian Pathol. 1983, 12, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, G.J.; Meyers, J.; Huang, D.D. Restricted growth of avirulent avian reovirus strain 2177 in macrophage derived HD11 cells. Virus Res. 2001, 81, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.X.; Li, S.; Li, S.-H.; Yu, S.X.; Wang, Q.H.; Zhang, K.H.; Qu, L.; Sun, Y.; Bi, Y.H.; Tang, F.C.; et al. Transcriptome profiling in swine macrophages infected with african swine fever virus at single-cell resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, e2201288119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Q.; Wang, Z.; Shao, C.H.; Yu, J.; Liu, H.Y.; Chen, H.J.; Li, L.; Wang, X.R.; Ren, Y.D.; Huang, X.D.; et al. Analysis of chicken macrophage functions and gene expressions following infectious bronchitis virus M41 infection. Vet. Res. 2021, 52, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.P.; He, M.H.; He, H.; Kilby, K.; Antueno, R. de; Castle, E.; McMullen, N.; Qian, Z.Y.; Zeev-Ben-Mordehai, T.; Duncan, R.; et al. Nonenveloped avian reoviruses released with small extracellular vesicles are highly infectious. Viruses 2023, 15, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Huang, W.-R.; Liao, T.L.; Nielsen, B.L.; Liu, H.J. Oncolytic avian reovirus p17-modulated inhibition of mTORC1 by enhancement of endogenous mTORC1 inhibitors binding to mTORC1 to disrupt its assembly and accumulation on lysosomes. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e00836–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Schmechel, S.C.; Williams, B.R.G.; Silverman, R.H.; Schiff, L.A. Involvement of the interferon-regulated antiviral proteins PKR and RNase l in reovirus-induced shutoff of cellular translation. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 2240–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wan, L.J.; Ren, H.Y.; Xie, Z.X.; Xie, L.J.; Huang, J.L.; Deng, X.W.; Xie, Z.Q.; Luo, S.S.; Li, M.; et al. Screening of interferon-stimulated genes against avian reovirus infection and mechanistic exploration of the antiviral activity of IFIT5. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 998505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.R.W.; Aldridge, J.R.; Fleming-Canepa, X.; Wang, Y.-D.; Webster, R.G.; Magor, K.E. Identification of avian RIG-1 responsive genes during influenza infection. Mol. Immunol. 2013, 54, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulwich, K.L.; Giotis, E.S.; Gray, A.; Nair, V.; Skinner, M.A.; Broadbent, A.J. Differential gene expression in chicken primary B cells infected ex vivo with attenuated and very virulent strains of infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV). J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2918–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, Z.Z.; Jiang, H.; Sun, J.; Diao, Y.X.; Tang, Y.; Hu, J.D. Transcriptional analysis of host responses related to immunity in chicken spleen tissues infected with reticuloendotheliosis virus strain SNV. Infect., Genet. Evol. 2019, 74, 103932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.S.B.; Nankemann, J.; Breedlove, C.; Pietruska, A.; Espejo, R.; Cuadrado, C.; Hauck, R. Changes in the transcriptome profile in young chickens after infection with LaSota Newcastle disease virus. Vaccines 2024, 12, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, K.; Isham, I.M.; Vatandour, S.; Boulianne, M.; Dozois, C.M.; Gagnon, C.A.; Barjesteh, N.; Abdul-Careem, M.F. Host immune response modulation in avian coronavirus infection: Tracheal transcriptome profiling in vitro and in vivo. Viruses 2024, 16, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajewicz-Krukowska, J.; Jastrzębski, J.P.; Grzybek, M.; Domańska-Blicharz, K.; Tarasiuk, K.; Marzec-Kotarska, B. Transcriptome sequencing of the spleen reveals antiviral response genes in chickens infected with CAstV. Viruses 2021, 13, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Lv, Y.; Li, X.N.; Zhao, D.; Yi, D.; Wang, L.; Li, P.; Chen, H.B.; Hou, Y.Q.; Gong, J. Establishment of a recombinant Escherichia coli-induced piglet diarrhea model. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 1517–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, K.M. Chemotactic activities of avian lymphocytes. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 1999, 23, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, F.; Liu, X.L.; Han, Z.X.; Shao, Y.H.; Kong, X.G.; Liu, W. Transcriptome analysis of chicken kidney tissues following coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus infection. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasekera, J.P.; Moseman, E.A.; Carroll, M.C. Natural antibody and complement mediate neutralization of influenza virus in the absence of prior immunity. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3487–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasa-Chapman, M.M.I.; Holuigue, S.; Aubin, K.; Wong, M.; Jones, N.A.; Cornforth, D.; Pellegrino, P.; Newton, P.; Williams, I.; Borrow, P.; et al. Detection of antibody-dependent complement-mediated inactivation of both autologous and heterologous virus in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 2823–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, R.L.; Griffin, D.E.; Winkelstein, J.A. The effect of complement depletion on the course of Sindbis virus infection in mice. J. Immunol. 1978, 121, 1276–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avirutnan, P.; Malasit, P.; Seliger, B.; Bhakdi, S.; Husmann, M. Dengue virus infection of human endothelial cells leads to chemokine production, complement activation, and apoptosis. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 6338–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, D.H.; Deussing, J.; Peters, C.; Dermody, T.S. Cathepsin l and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 24609–24617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, J.W.; Bahe, J.A.; Lucas, W.T.; Nibert, M.L.; Schiff, L.A. Cathepsin S supports acid-independent infection by some reoviruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 8547–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branski, D.; Lebenthal, E.; Faden, H.S.; Hatch, T.F.; Krasner, J. Reovirus type 3 infection in a suckling mouse: The effects on pancreatic structure and enzyme content. Pediatr. Res. 1980, 14, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, M.I.; Kermani, N.Z.; Neerincx, A.H.; Vijverberg, S.J.H.; Guo, Y.K.; Howarth, P.; Dahlen, S.-E.; Djukanovic, R.; Sterk, P.J.; Kraneveld, A.D.; et al. Association of endopeptidases, involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection, with microbial aggravation in sputum of severe asthma. Allergy 2021, 76, 1917–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.F.; Li, T.; Chiu, K.Y.; Wen, C.Y.; Xu, A.M.; Yan, C.H. FABP4 as a biomarker for knee osteoarthritis. Biomarkers Med. 2018, 12, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.B.; Lee, A.Y.W.; Kot, C.H.; Yung, P.S.H.; Chen, S.; Lui, P.P.Y. Upregulation of FABP4 induced inflammation in the pathogenesis of chronic tendinopathy. J. Orthop. Transl. 2024, 47, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baazim, H.; Koyuncu, E.; Tuncman, G.; Burak, M.F.; Merkel, L.; Bahour, N.; Karabulut, E.S.; Lee, G.Y.; Hanifehnezhad, A.; Karagoz, Z.F.; et al. FABP4 as a therapeutic host target controlling SARS-CoV2 infection 2024.

- Gharpure, K.M.; Pradeep, S.; Sans, M.; Rupaimoole, R.; Ivan, C.; Wu, S.Y.; Bayraktar, E.; Nagaraja, A.S.; Mangala, L.S.; Zhang, X.N.; et al. FABP4 as a key determinant of metastatic potential of ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.L.; Gupta, K.; Quintero, J.R.; Cernadas, M.; Kobzik, L.; Christou, H.; Pier, G.B.; Owen, C.A.; Çataltepe, S. Macrophage FABP4 is required for neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 3562–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, C.; Xie, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, P.; Du, J.; Tian, J. FABP4 contributes toward regulating inflammatory gene expression and oxidative stress in Ctenopharyngodon idella. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2022, 259, 110715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreault, S.; Martenon-Brodeur, C.; Caron, M.; Garant, J.-M.; Tremblay, M.-P.; Armero, V.E.S.; Durand, M.; Lapointe, E.; Thibault, P.; Tremblay-Létourneau, M.; et al. Global profiling of the cellular alternative RNA splicing landscape during virus-host interactions. PLOS One 2016, 11, e0161914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.F.; Meistermann, H.; Tzouros, M.; Baker, A.; Golling, S.; Polster, J.S.; Ledwith, M.P.; Gitter, A.; Augustin, A.; Javanbakht, H.; et al. Alternative splicing liberates a cryptic cytoplasmic isoform of mitochondrial MECR that antagonizes influenza virus. PLOS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.G.; Dittmar, M.; Mallory, M.J.; Bhat, P.; Ferretti, M.B.; Fontoura, B.M.; Cherry, S.; Lynch, K.W. Viral-induced alternative splicing of host genes promotes influenza replication. eLife 2020, 9, e55500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Qi, W.B.; Chang, Q.; Chen, R.H.; Zhen, D.L.; Liao, M.; Wen, J.K.; Deng, Y.Q. Influenza A virus protein PA-X suppresses host Ankrd17-mediated immune responses. Microbiol. Immunol. 2021, 65, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Tong, X.M.; Li, G.; Li, J.H.; Deng, M.; Ye, X. Ankrd17 positively regulates RIG-I-like receptor (RLR)-mediated immune signaling. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 1304–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menning, M.; Kufer, T.A. A role for the Ankyrin repeat containing protein Ankrd17 in Nod1- and Nod2-mediated inflammatory responses. FEBS Letters 2013, 587, 2137–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.M.; Meng, G.Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.Y.; Diao, Y.X.; Zhao, S.P.; Feng, Q.; Tang, Y. The oncolytic efficacy and safety of avian reovirus and its dynamic distribution in infected mice. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Huang, J.W.; Huang, W.R.; Chen, I.C.; Chen, M.S.; Liao, T.L.; Chang, Y.-K.; Munir, M.; Liu, H.-J. Oncolytic avian reovirus σa-modulated upregulation of the hif-1α/c-myc/glut1 pathway to produce more energy in different cancer cell lines benefiting virus replication. Viruses 2023, 15, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, R.A.; Hattin, L.; Biondi, M.J.; Corredor, J.C.; Walsh, S.; Xue-Zhong, M.; Manuel, J.; McGilvray, I.D.; Morgenstern, J.; Lusty, E.; et al. Replication and oncolytic activity of an avian orthoreovirus in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Viruses 2017, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, M.D.; Andres, D.A.; Der, C.J.; Repasky, G.A. Characterization of RERG: An estrogen-regulated tumor suppressor gene. In Methods in Enzymology; Regulators and Effectors of Small GTPases: Ras Family; Academic Press, 2006; Vol. 407, pp. 513–527.

- Zhao, R.J.; Chen, S.L.; Cui, W.H.; Xie, C.Y.; Zhang, A.P.; Yang, L.; Dong, H.M. PTPN1 is a prognostic biomarker related to cancer immunity and drug sensitivity: From pan-cancer analysis to validation in breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, S.; Ohmuraya, M.; Akagawa, H.; Horita, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Kaneko, N.; Sugawara, N.; Ishizuka, K.; Miura, K.; Harita, Y.T.K.; et al. Deletion in the cobalamin synthetase W domain–containing protein 1 gene is associated with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. : JASN 2020, 31, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartill, V.L.; van de Hoek, G.; Patel, M.P.; Little, R.; Watson, C.M.; Berry, I.R.; Shoemark, A.; Abdelmottaleb, D.; Parkes, E.; Bacchelli, C.; et al. DNAAF1 links heart laterality with the AAA+ ATPase RUVBL1 and ciliary intraflagellar transport. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, L.; Chen, B.; Liu, K.; Liu, B.Y.; He, X.Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.X.; He, M.D.; Zhu, L.; Liu, K.; et al. CircZDBF2 up-regulates RNF145 by ceRNA model and recruits CEBPB to accelerate oral squamous cell carcinoma progression via NFκB signaling pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y.; Zhang, W.D.; Li, S.Q.; Tao, X.B.; Xu, H.W.; Wu, Y.T.; Chen, Q.; Ning, A.H.; Tian, T.; Zhang, L.; et al. Integration of apaQTL and eQTL analysis reveals novel snps associated with occupational pulmonary fibrosis risk. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 2117–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, S.; Wilson, M.; Downs, J.; Williams, S.; Murgia, A.; Sartori, S.; Vecchi, M.; Ho, G.; Polli, R.; Psoni, S.; et al. The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Y.; Shang, L.; Shi, Z.Z.; Zhang, T.T.; Ma, S.; Lu, C.C.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, J.J.; Shi, C.; Shi, F.; et al. Microtubule-associated protein 4 is an important regulator of cell invasion/migration and a potential therapeutic target in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2016, 35, 4846–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).