Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Total CO2 uptake, assessed through measurements of carbonation capacity, carbonation degree achieved, and resulting efficiency.

- Kinetic behavior, evaluated by measuring the CO2 absorption rate.

- Leachability of heavy metals (HMs), determined by analyzing HMs concentrations in the carbonated wastewater and assessing the stability of the carbonated product.

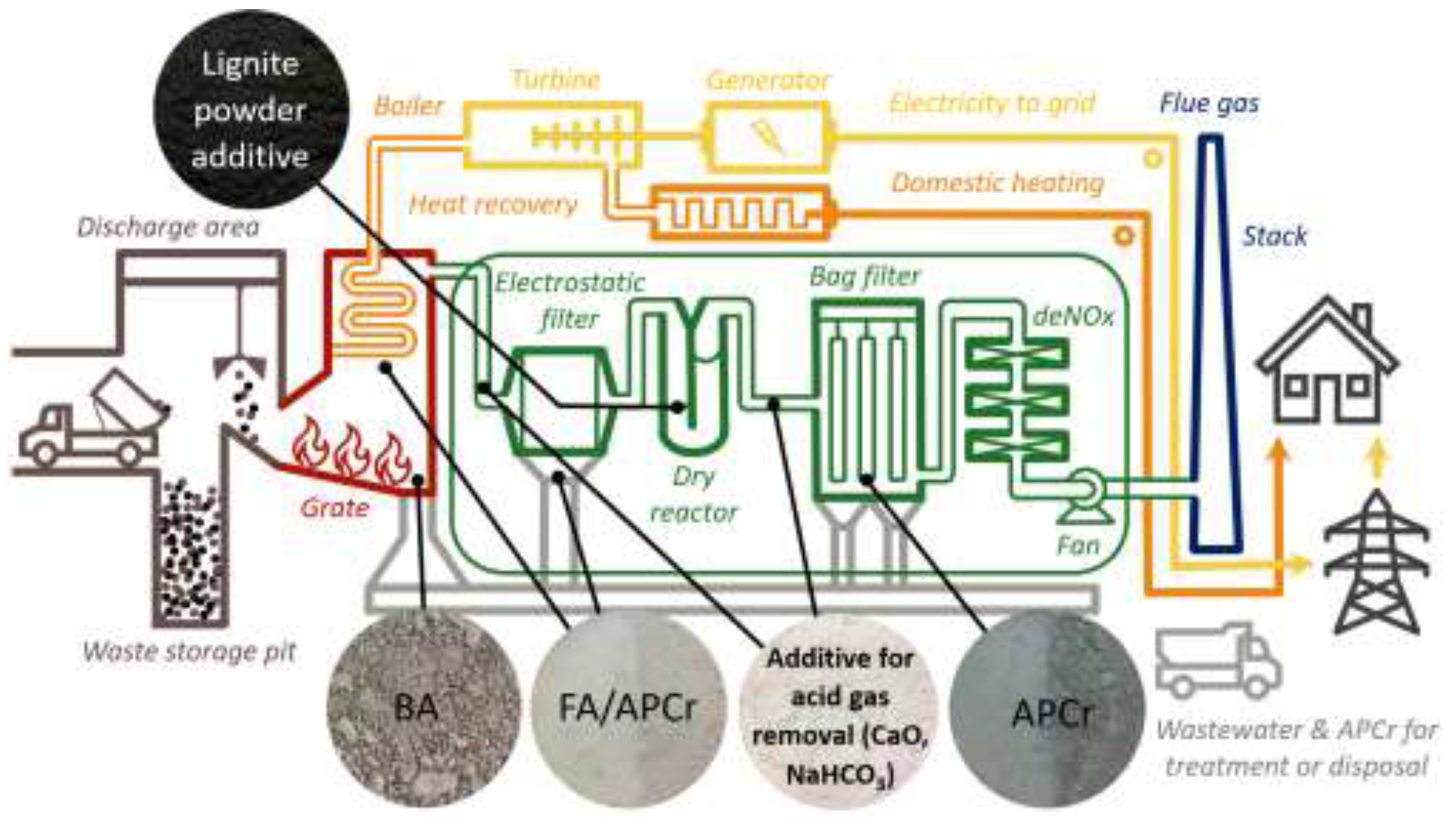

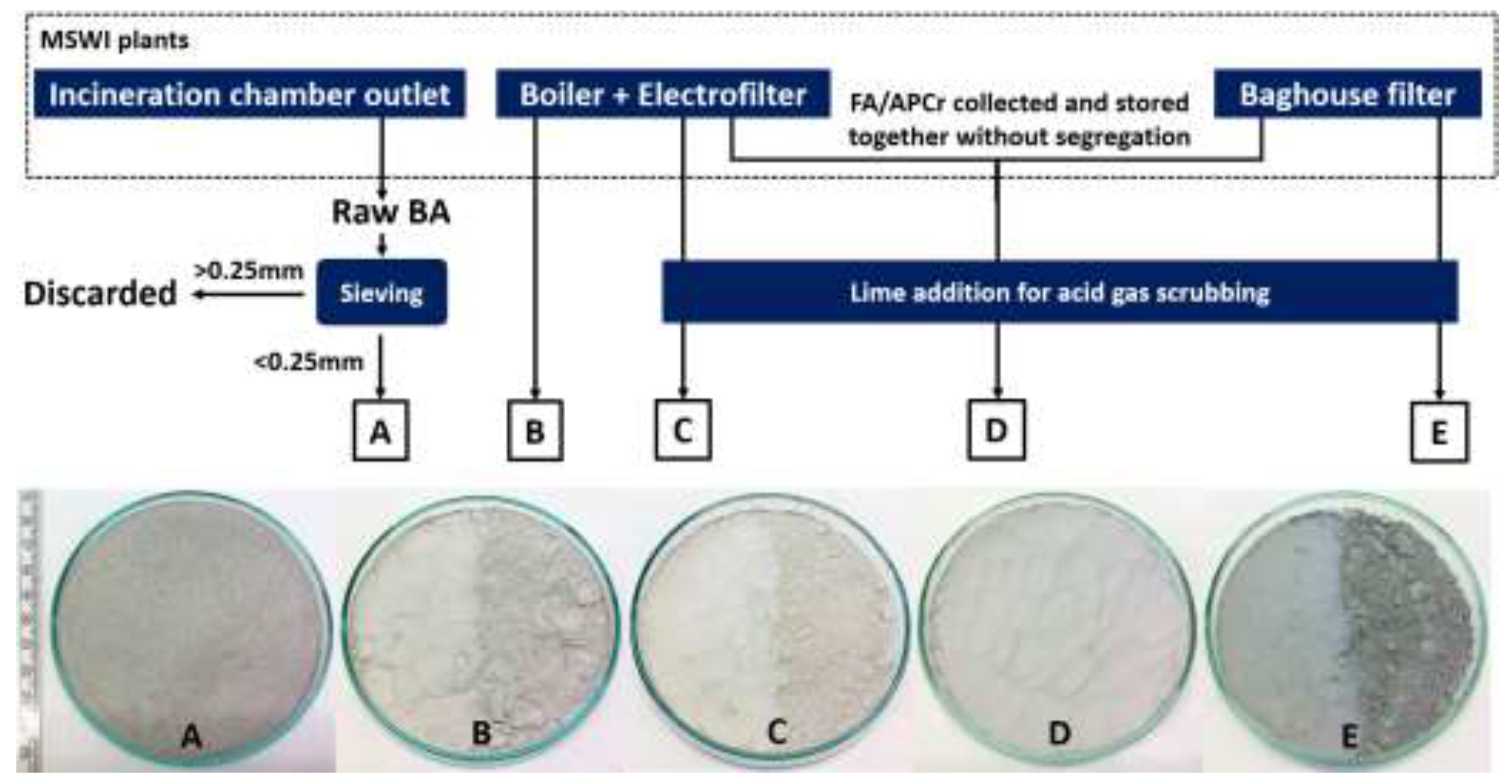

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. MSWIr Physicochemical Characterization

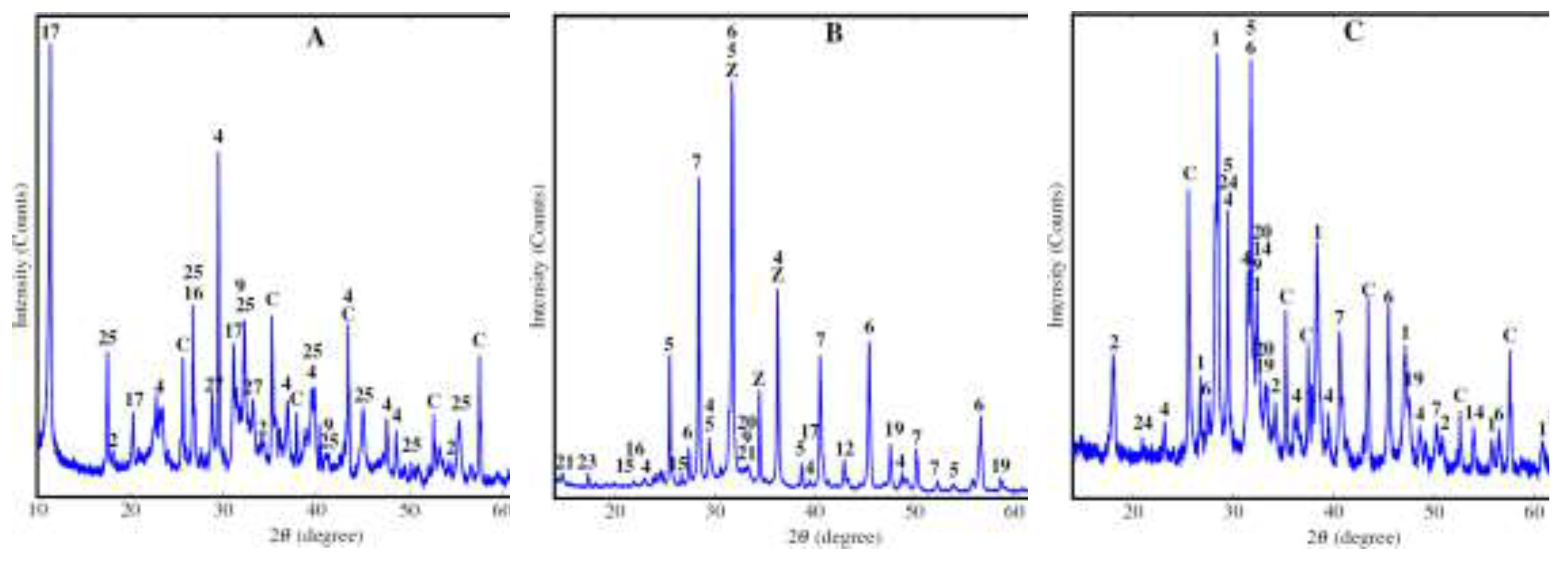

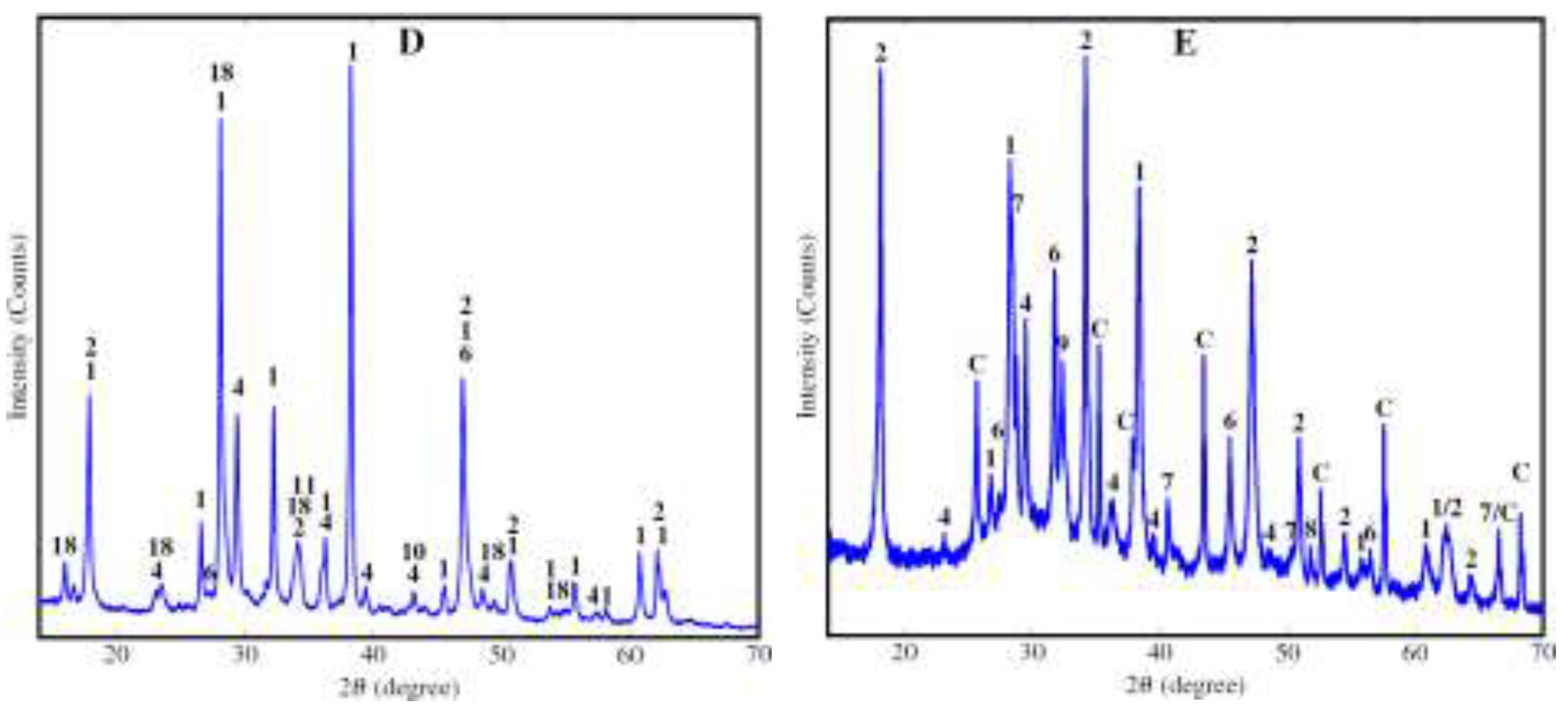

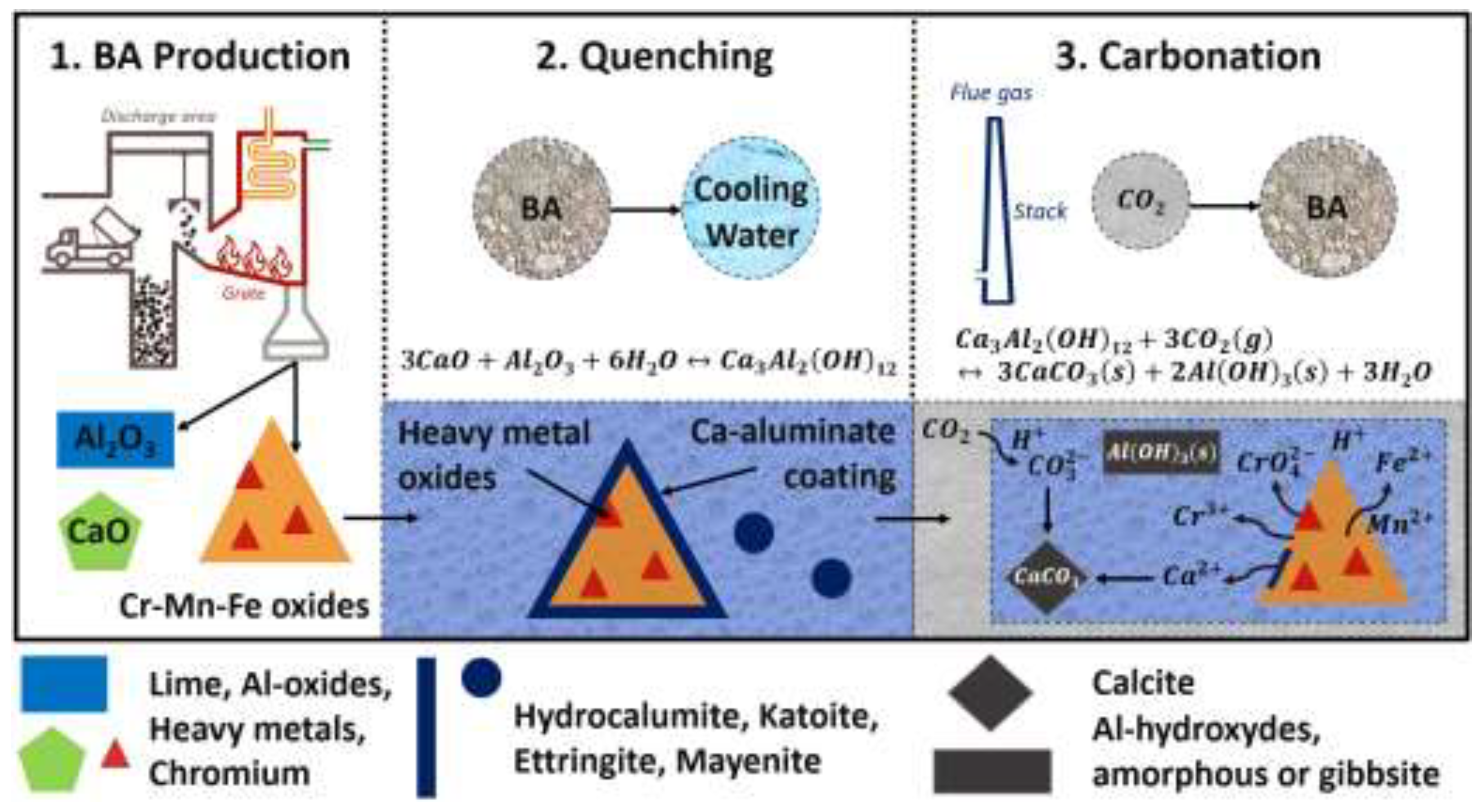

3.1.1. Mineralogy and Chemistry

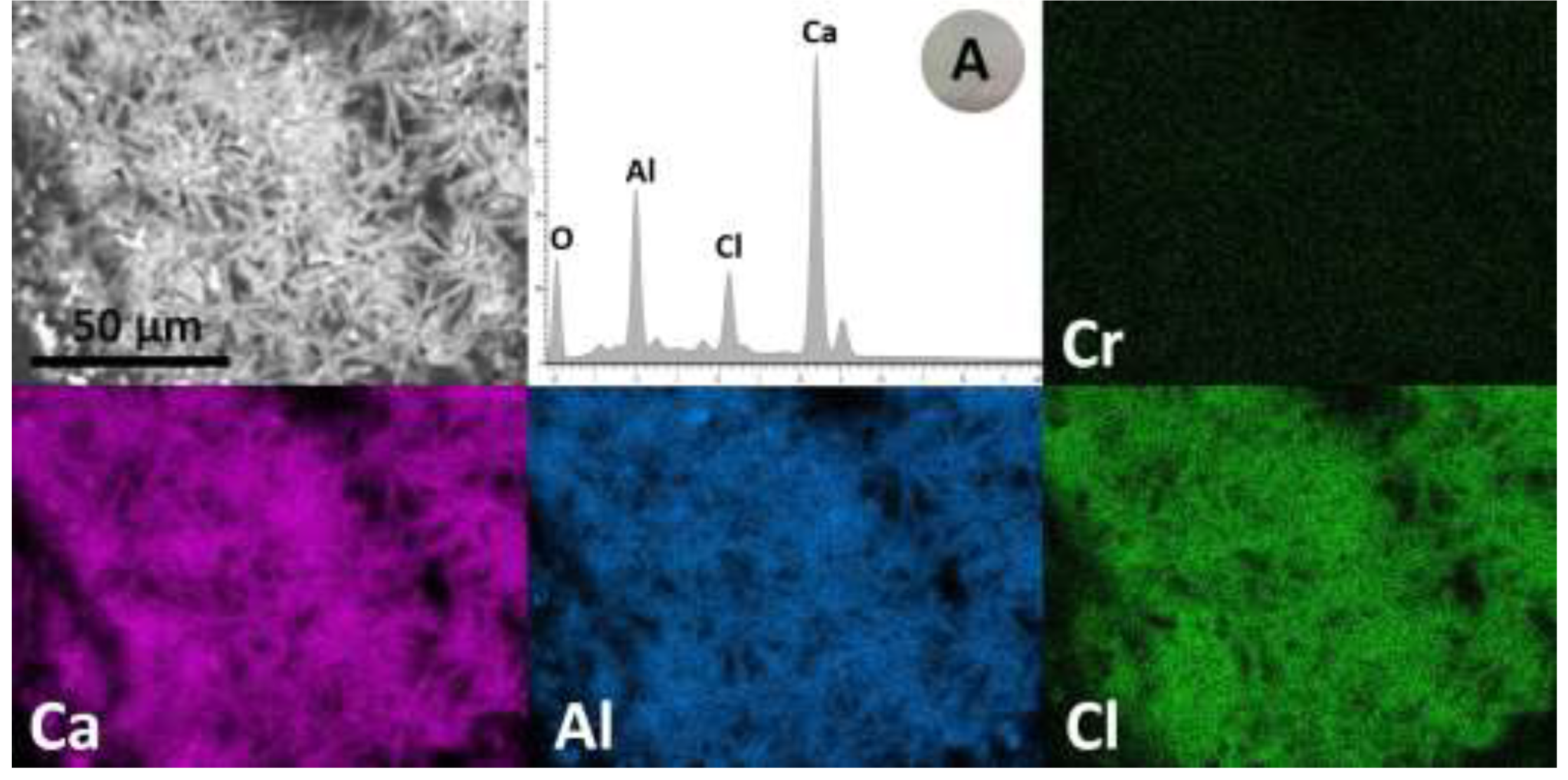

3.1.2. Microstucture

3.2. MSWIr Reactivity to Aqueous Carbonation

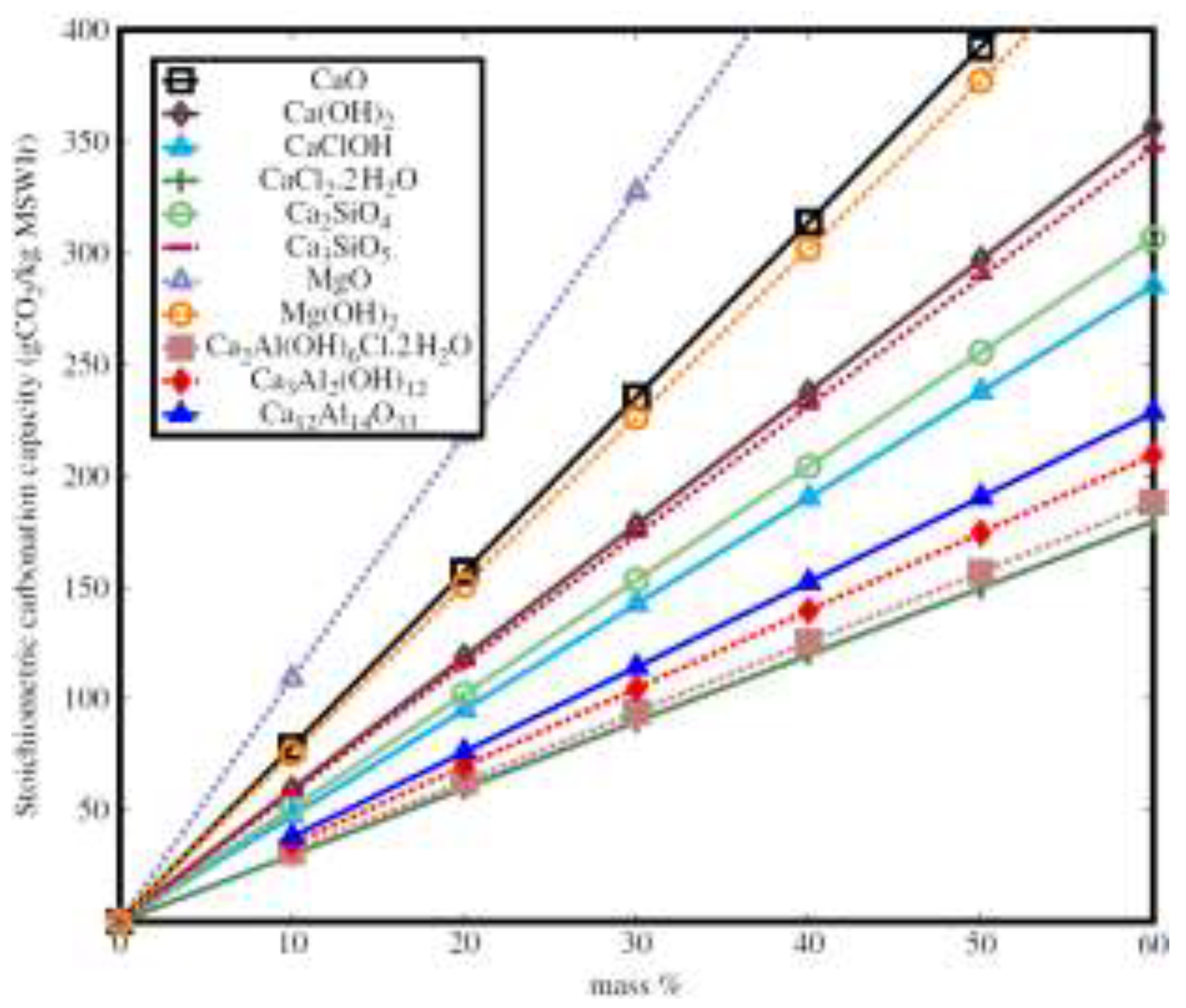

3.2.1. Theoretical Background

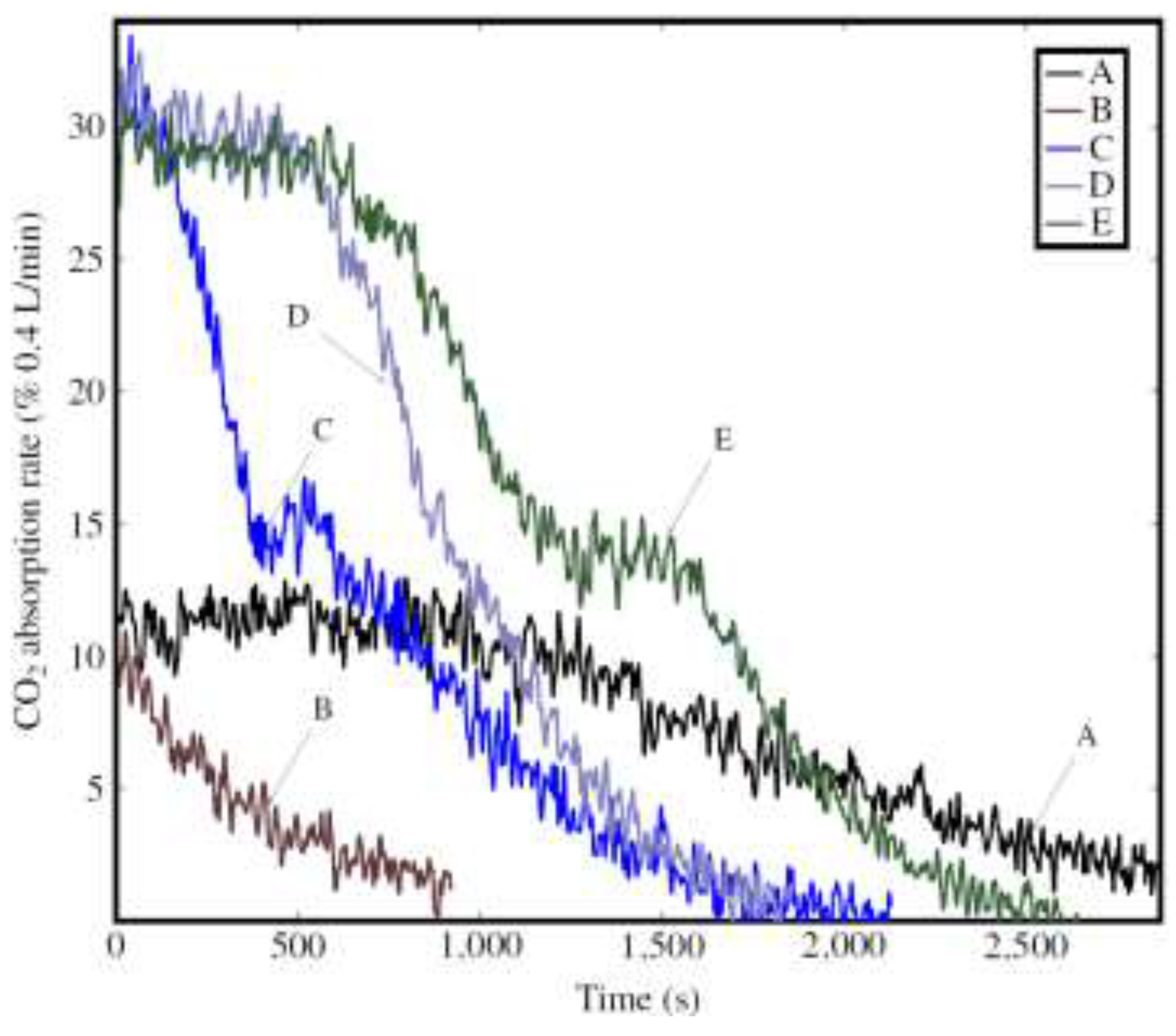

3.2.2. CO2 Absorption Rate and Total Uptake

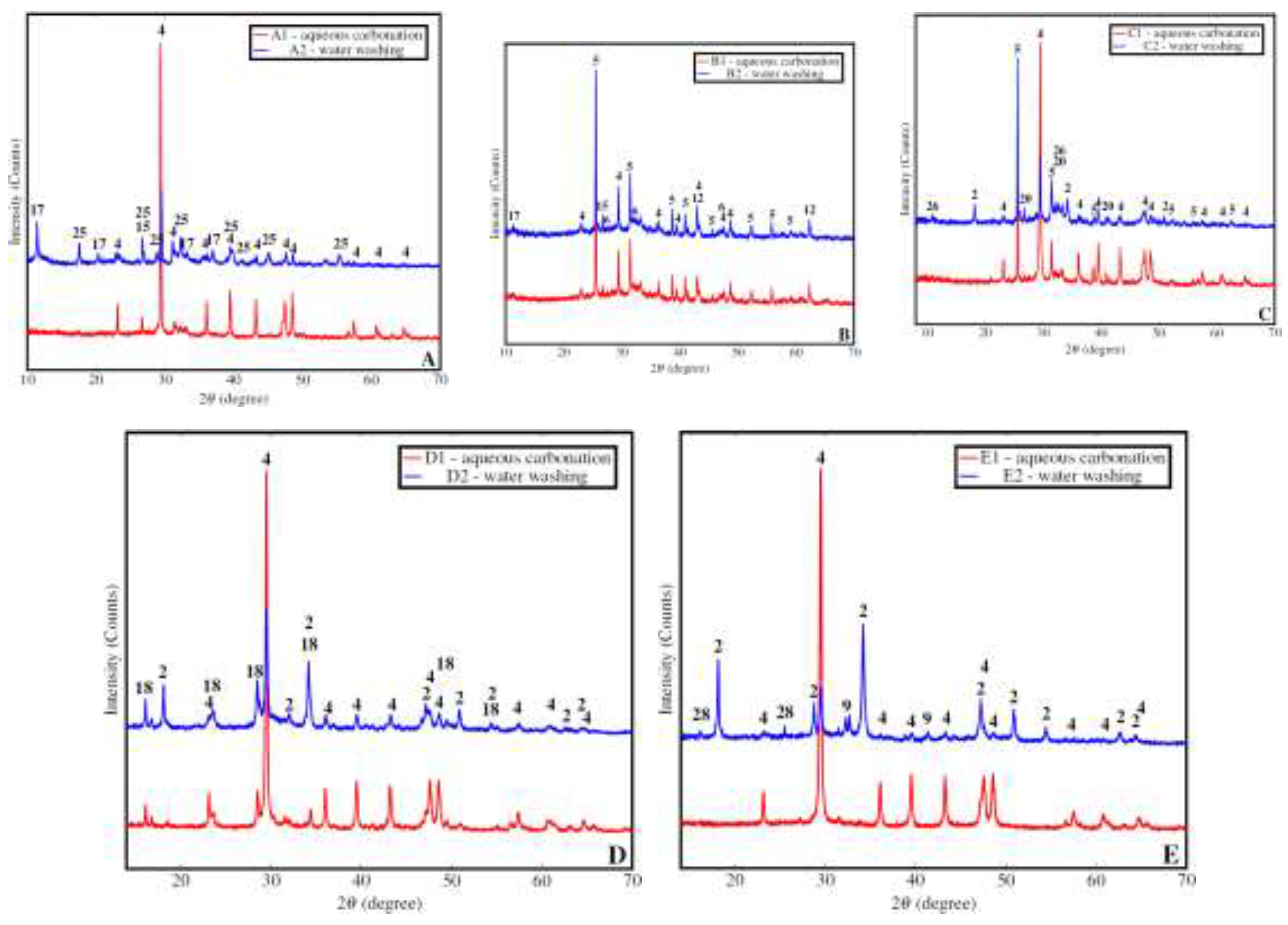

3.2.3. Mineralogy Changes in Carbonated And Washed Samples

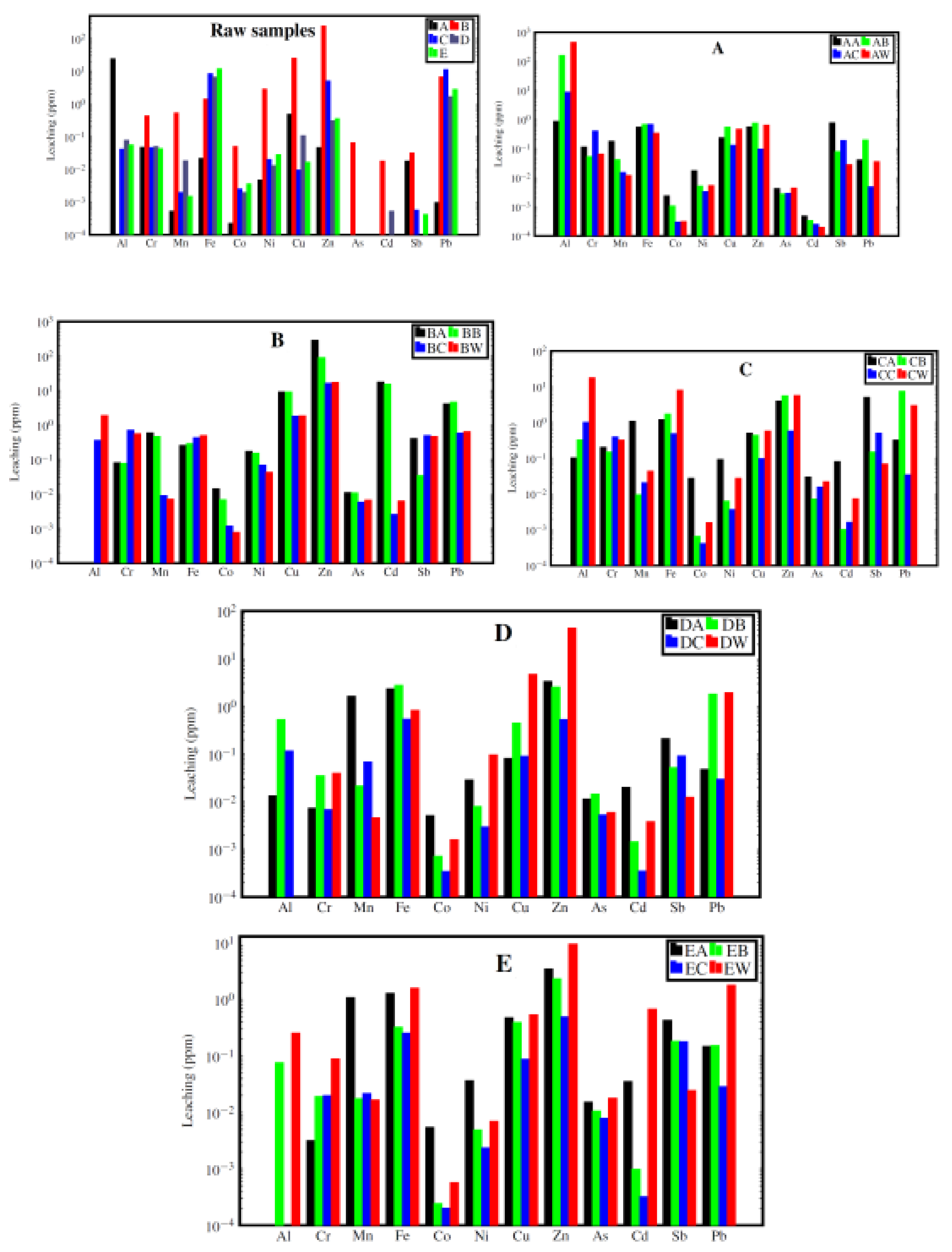

3.2.4. HMs Leaching During and After Carbonation

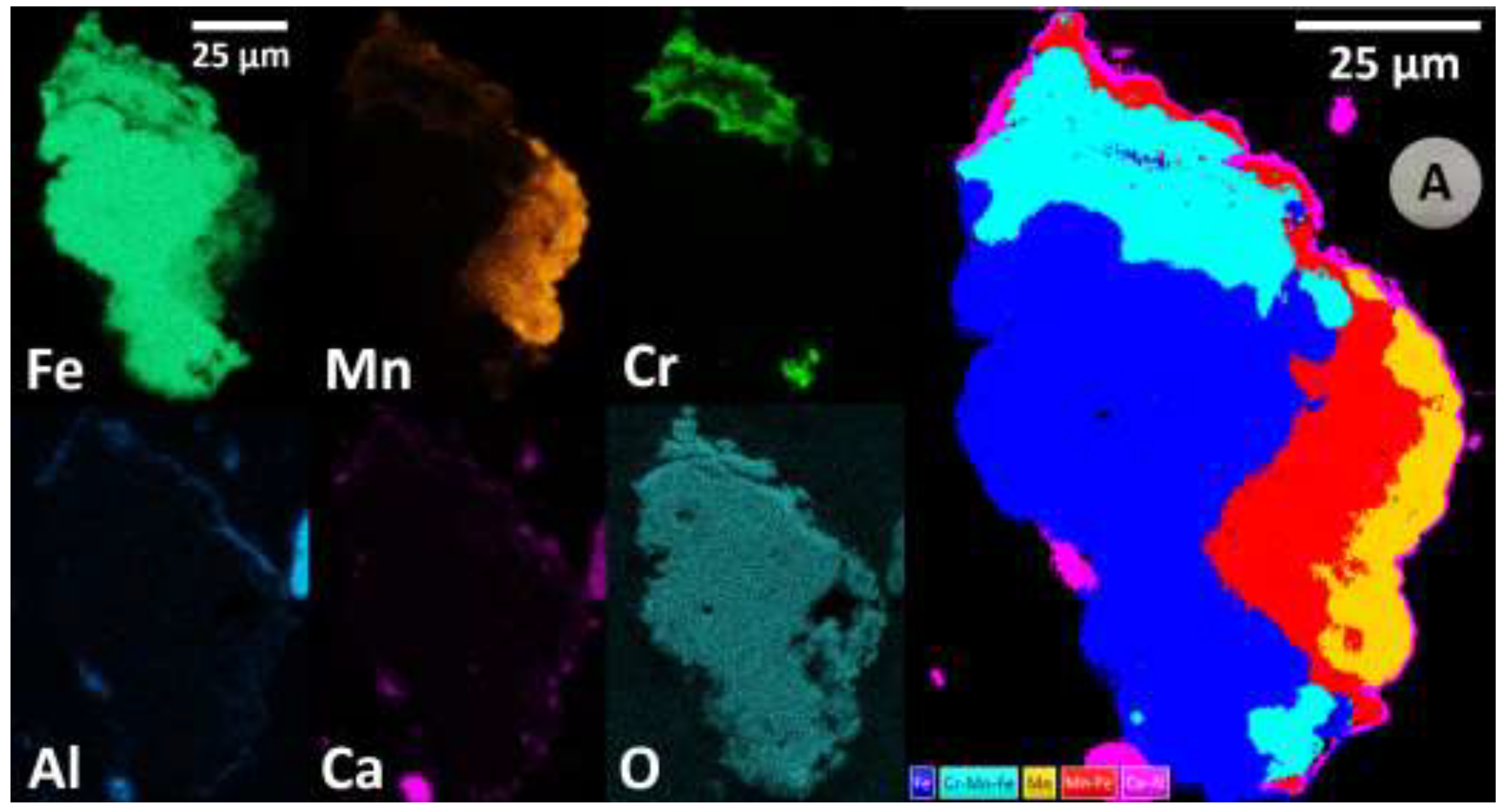

3.2.5. Mechanism of Chromium Leaching in BA Carbonation: A Novel Perspective

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bodor, M.; Santos, R. M.; Van Gerven, T.; Vlad, M. Recent developments and perspectives on the treatment of industrial wastes by mineral carbonation—a review. Cent. Eur. J. Eng. 2013, 3, 566-584. [CrossRef]

- Hills, C. D.; Tripathi, N.; Carey, P. J. Mineralization technology for carbon capture, utilization, and storage. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 142. [CrossRef]

- Baciocchi, R.; Costa, G. CO2 utilization and long-term storage in useful mineral products by carbonation of alkaline feedstocks. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 592600. [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Zhao, M.; Xu, M.; Mo, L. Maximising the benefits of calcium carbonate in sustainable cements: opportunities and challenges associated with alkaline waste carbonation. npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Gunning, P. J., Hills, C. D.; Carey, P. J. Accelerated carbonation treatment of industrial wastes. Waste Manag. 2010, 30(6), 1081-1090. [CrossRef]

- Di Maria, A.; Snellings, R.; Alaerts, L.; Quaghebeur, M.; Van Acker, K. Environmental assessment of CO2 mineralisation for sustainable construction materials. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 2020, 93, 102882. [CrossRef]

- Tiefenthaler, J.; Braune, L.; Bauer, C.; Sacchi, R.; Mazzotti, M. Technological demonstration and life cycle assessment of a negative emission value chain in the Swiss concrete sector. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 729259. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chai, Y. E.; Santos, R. M.; Šiller, L. Advances in process development of aqueous CO2 mineralisation towards scalability. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8(6), 104453. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Shimaoka, T.; Saffarzadeh, A.; Takahashi, F. Mineralogical characterization of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash with an emphasis on heavy metal-bearing phases. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 187(1-3), 534-543. [CrossRef]

- Nam, S. Y. Accelerated carbonation of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash for CO2 sequestration. Geosyst. Eng. 2012, 15(4), 305-311. [CrossRef]

- Baciocchi, R.; Costa, G.; Di Bartolomeo, E.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R. The effects of accelerated carbonation on CO2 uptake and metal release from incineration APC residues. Waste Manage. 2009, 29(12), 2994-3003. [CrossRef]

- Rocca, S.; van Zomeren, A.; Costa, G.; Dijkstra, J. J.; Comans, R. N.; Lombardi, F. Characterisation of major component leaching and buffering capacity of RDF incineration and gasification bottom ash in relation to reuse or disposal scenarios. Waste Manage. 2012, 32(4), 759-768. doi:j.wasman.2011.11.018.

- Di Gianfilippo, M.; Costa, G.; Pantini, S.; Allegrini, E.; Lombardi, F.; Astrup, T. F. LCA of management strategies for RDF incineration and gasification bottom ash based on experimental leaching data. Waste Manage. 2016, 47, 285-298. [CrossRef]

- Jagodzińska, K.; Mroczek, K.; Nowińska, K.; Gołombek, K.; Kalisz, S. The impact of additives on the retention of heavy metals in the bottom ash during RDF incineration. Energy 2019, 183, 854-868. [CrossRef]

- Mlonka-Mędrala, A.; Dziok, T.; Magdziarz, A.; Nowak, W. Composition and properties of fly ash collected from a multifuel fluidized bed boiler co-firing refuse derived fuel (RDF) and hard coal. Energy 2021, 234, 121229. 10.1016/j.energy.2021.121229.

- Shehata, N.; Obaideen, K.; Sayed, E. T.; Abdelkareem, M. A.; Mahmoud, M. S.; El-Salamony, A. H. R.; Mahmoud, M.H.; Olabi, A. G. Role of refuse-derived fuel in circular economy and sustainable development goals. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2022, 163, 558-573. [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Gu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Haixiang, Y.; Xu, S. Mechanistic insights into temperature-driven retention and speciation changes of heavy metals (HMs) in ash residues from Co-combustion of refuse-derived fuel (RDF) and red mud. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 368, 121967. [CrossRef]

- Nikravan, M.; Ramezanianpour, A. A.; Maknoon, R. Study on physiochemical properties and leaching behavior of residual ash fractions from a municipal solid waste incinerator (MSWI) plant. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 260, 110042. [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, D.; Caviglia, C.; Destefanis, E.; Agostino, A. Boero, R.; Marinoni, N.; Pavese, A. Influence of speciation distribution and particle size on heavy metal leaching from MSWI fly ash. Waste Manage. 2022, 138, 318-327. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Tian, S.; Zhang, C. Influence of SO2 in incineration flue gas on the sequestration of CO2 by municipal solid waste incinerator fly ash. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25(4), 735-740. [CrossRef]

- Viet, D. B.; Chan, W. P.; Phua, Z. H.; Ebrahimi, A.; Abbas, A.; Lisak, G. The use of fly ashes from waste-to-energy processes as mineral CO2 sequesters and supplementary cementitious materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 122906. [CrossRef]

- Bandarra, B. S.; Silva, S.; Pereira, J. L.; Martins, R. C.; Quina, M. J. A Study on the Classification of a Mirror Entry in the European List of Waste: Incineration Bottom Ash from Municipal Solid Waste. Sustainability 2022, 14(16), 10352. [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, C.; Mantovani, L.; Tribaudino, M.; Bernasconi, A.; Destefanis, E.; Caviglia, C.; Funari, V. Sequential extraction procedure of municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) bottom ash targeting grain size and the amorphous fraction. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1254205. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, R. J.; Sng, A.; Wang, C.; Tao, L.; Zhu, Q.; Bu, J. Strategies for heavy metals immobilization in municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash: a critical review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2024, 23(2), 503-568. [CrossRef]

- Chandler, A. J.; Eighmy, T. T.; Hjelmar, O.; Kosson, D. S.; Sawell, S. E.; Vehlow, J.; Hartlén, J. Municipal solid waste incinerator residues 1997. Elsevier. From https://www.elsevier.com/books/municipalsolid-waste-incinerator-residues/chandler/978-0-444-82563-6.

- De Boom, A.; Degrez, M. Belgian MSWI fly ashes and APC residues: a characterisation study. Waste Manage. 2012, 32(6), 1163-1170. [CrossRef]

- Raclavska, H.; Matysek, D.; Raclavsky, K.; Juchelkova, D. Geochemistry of fly ash from desulphurisation process performed by sodium bicarbonate. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91(2), 150-157. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Ji, Y.; Buekens, A.; Ma, Z.; Jin, Y.; Li, X.; Yan, J. Activated carbon treatment of municipal solid waste incineration flue gas. Waste Manage. Res. 2013, 31(2), 169-177. [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Gu, Q.; Jin, B. Density functional theory study on the formation mechanism of CaClOH in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30(48), 106514-106532. [CrossRef]

- Meima, J. A.; van der Weijden, R. D.; Eighmy, T. T.; Comans, R. N. Carbonation processes in municipal solid waste incinerator bottom ash and their effect on the leaching of copper and molybdenum. Appl. Geochem. 2002, 17(12), 1503-1513. [CrossRef]

- Baciocchi, R.; Costa, G.; Lategano, E.; Marini, C.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; Rocca, S. Accelerated carbonation of different size fractions of bottom ash from RDF incineration. Waste Manage. 2010, 30(7), 1310-1317. [CrossRef]

- Brück, F.; Schnabel, K.; Mansfeldt, T.; Weigand, H. Accelerated carbonation of waste incinerator bottom ash in a rotating drum batch reactor. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6(4), 5259-5268. [CrossRef]

- Campo, F. P.; Tua, C.; Biganzoli, L.; Pantini, S.; Grosso, M. Natural and enhanced carbonation of lime in its different applications: a review. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2021, 10(1), 224-237. [CrossRef]

- Jozewicz, W.; Gullett, B. K. Reaction mechanisms of dry Ca-based sorbents with gaseous HCl. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1995, 34(2), 607-612. [CrossRef]

- Chyang, C. S.; Han, Y. L.; Zhong, Z. C. Study of HCl absorption by CaO at high temperature. Energy Fuels 2009, 23(8), 3948-3953. [CrossRef]

- Jaschik, J.; Jaschik, M.; Warmuziński, K. The utilisation of fly ash in CO2 mineral carbonation. Chem. Process Eng. 2016, 37(1), 29-39. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Wang, T.; Wu, W.; Wang, D.; Jin, B. Influence of pretreatments on accelerated dry carbonation of MSWI fly ash under medium temperatures. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 414, 128756. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fu, C.; Mao, T.; Shen, Y.; Li, M.; Lin, X.; Yan, J. Study on the accelerated carbonation of MSWI fly ash under ultrasonic excitation: CO2 capture, heavy metals solidification, mechanism and geochemical modelling. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138418. [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, G. P.; Guimarães, R.; Valentim, B.; Bontempi, E. The Influence of Liquid/Solid Ratio and Pressure on the Natural and Accelerated Carbonation of Alkaline Wastes. Minerals 2023, 13(8), 1080. [CrossRef]

- Brück, F.; Mansfeldt, T.; Weigand, H. Flow-through carbonation of waste incinerator bottom ash in a rotating drum batch reactor: Role of specific CO2 supply, mixing tools and fill level. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7(2), 102975. [CrossRef]

- Brück, F.; Ufer, K.; Mansfeldt, T.; Weigand, H. Continuous-feed carbonation of waste incinerator bottom ash in a rotating drum reactor. Waste Manage. 2019, 99, 135-145. [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, K.; Brück, F.; Mansfeldt, T.; Weigand, H. Full-scale accelerated carbonation of waste incinerator bottom ash under continuous-feed conditions. Waste Manage. 2021, 125, 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.; Han, G. C.; Ahn, J. W.; You, K. S. Environmental remediation and conversion of carbon dioxide (CO2) into useful green products by accelerated carbonation technology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2010, 7(1), 203-228. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. W.; Han, C.; Whan, A. J. CO2 sequestration of real flue gases from landfill municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) -Pilot scale demonstration. Int. J. Phys. Appl. Sci. 2015, 2(9), 54-63.

- Um, N.; Ahn, J. W. Effects of two different accelerated carbonation processes on MSWI bottom ash. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 111, 560-568. [CrossRef]

- Gunning, P. J.; Hills, C. D.; Carey, P. J. Production of lightweight aggregate from industrial waste and carbon dioxide. Waste Manage. 2009, 29(10), 2722-2728. [CrossRef]

- Quina, M. J.; Garcia, R.; Simões, A. S.; Quinta-Ferreira, R. M. Life cycle assessment of lightweight aggregates produced with ashes from municipal solid waste incineration. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 2020, 22, 1922-1931. [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, D.; Viani, A.; Zárybnická, L.; Mácová, P.; Bordignon, S.; Caviglia, C.; Pavese, A. Phosphate-based geopolymer: Influence of municipal solid waste fly ash introduction on structure and compressive strength. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49(13), 22149-22159. [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, D.; Viani, A.; Zárybnická, L.; Mácová, P.; Bordignon, S.; Das, G.; Pavese, A. Reactivity of MSWI-fly ash in Mg-K-phosphate cement. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 409, 134082. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; He, H.; He, C.; Li, B.; Luo, W.; Ren, P. Low-carbon blended cement containing wet carbonated municipal solid waste incineration fly ash and mechanically activated coal fly ash. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03671. [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Ge, W.; Xia, Y.; Sun, C.; Lin, X.; Tsang, D. C.; Yan, J. Upcycling MSWI fly ash into green binders via flue gas-enhanced wet carbonation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 141013. [CrossRef]

- Quina, M. J.; Bontempi, E.; Bogush, A.; Schlumberger, S.; Weibel, G.; Braga, R.; Lederer, J. Technologies for the management of MSW incineration ashes from gas cleaning: New perspectives on recovery of secondary raw materials and circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 526-542. [CrossRef]

- Langer, M. Use of solution-mined caverns in salt for oil and gas storage and toxic waste disposal in Germany. Eng. Geol. 1993, 35(3-4), 183-190. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Ni, W. The effects and solidification characteristics of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash-slag-tailing based backfill blocks in underground mine condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 420, 135508. [CrossRef]

- Kashefi, K.; Pardakhti, A.; Shafiepour, M.; Hemmati, A. Process optimization for integrated mineralization of carbon dioxide and metal recovery of red mud. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8(2), 103638. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Moon, S.; Sim, G.; Park, Y. Metal recovery from iron slag via pH swing-assisted carbon mineralization with various organic ligands. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 69, 102418. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D. An integrated process of CO2 mineralization and selective nickel and cobalt recovery from olivine and laterites. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 139002. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D. Enhanced CO2 mineralization and selective critical metal extraction from olivine and laterites. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 321, 124268. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D.; Xiao, Y. Accelerated CO2 mineralization and utilization for selective battery metals recovery from olivine and laterites. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 393, 136345. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Chung, W. J.; Khan, M. A.; Son, M.; Park, Y. K.; Lee, S. S.; Jeon, B. H. Breakthrough innovations in carbon dioxide mineralization for a sustainable future. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol 2024, 23(3), 739-799. [CrossRef]

- Caviglia, C.; Destefanis, E.; Pastero, L.; Bernasconi, D.; Bonadiman, C.; Pavese, A. MSWI fly ash multiple washing: Kinetics of dissolution in water, as function of time, temperature and dilution. Minerals 2022, 12(6), 742. [CrossRef]

- Brück, F.; Fröhlich, C.; Mansfeldt, T.; Weigand, H. A fast and simple method to monitor carbonation of MSWI bottom ash under static and dynamic conditions. Waste Manage. 2018, 78, 588-594. [CrossRef]

- Wehrung, Q.; Pastero, L.; Bernasconi, D.; Cotellucci, A.; Bruno, M.; Cavagna, S.; Pavese, A. Impact of Operational Parameters on the CO2 Absorption Rate in Ca(OH)2 Aqueous Carbonation─Implications for Process Efficiency. Energy Fuels 2024, 38(17), 16678-16691. [CrossRef]

- Wehrung, Q.; Bernasconi, D.; Destefanis, E.; Caviglia, C.; Curetti, N.; Bicchi, E.; Pavese, A. ; Pastero, L. Carbonation washing of waste incinerator air pollution control residues under wastewater reuse conditions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, submitted.

- Caviglia, C.; Confalonieri, G.; Corazzari, I.; Destefanis, E.; Mandrone, G.; Pastero, L.; Pavese, A. Effects of particle size on properties and thermal inertization of bottom ashes (MSW of Turin’s incinerator). Waste Manage. 2019, 84, 340-354. [CrossRef]

- Wolffers, M.; Eggenberger, U.; Schlumberger, S.; Churakov, S. V. Characterization of MSWI fly ashes along the flue gas cooling path and implications on heavy metal recovery through acid leaching. Waste Manage. 2021, 134, 231-240. [CrossRef]

- Deuster, E. V.; Mensing, A.; Jiang, M. X.; Majdeski, H. Cleaning of flue gas from solid waste incinerator plants by wet/semi-dry process. Environ. Prog. 1994, 13(2), 149-153. [CrossRef]

- Gevers, B. R.; Labuschagné, F. J. Green synthesis of hydrocalumite (CaAl-OH-LDH) from Ca(OH)2 and Al(OH)3 and the parameters that influence its formation and speciation. Crystals 2020, 10(8), 672. [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, A.; Kutus, B.; Kónya, Z.; Kukovecz, Á.; Pálinkó, I.; Sipos, P. Estimation of the solubility product of hydrocalumite–hydroxide, a layered double hydroxide with the formula of [Ca2Al(OH)6]OH·nH2O. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2016, 98, 167-173. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Rives, V.; Vicente, M. A. Thermal study of the hydrocalumite–katoite–calcite system. Thermochim. Acta. 2022, 713, 179242. [CrossRef]

- Polettini, A.; Pomi, R. The leaching behavior of incinerator bottom ash as affected by accelerated ageing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 113(1-3), 209-215. [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Ren, F.; Nguyen, M. Q.; Ahamed, A.; Yin, K.; Chan, W. P.; Chang, V. W. C. Review of MSWI bottom ash utilization from perspectives of collective characterization, treatment and existing application. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 24-38. [CrossRef]

- Alam, Q.; Schollbach, K.; Rijnders, M.; van Hoek, C.; van der Laan, S.; Brouwers, H. J. H. The immobilization of potentially toxic elements due to incineration and weathering of bottom ash fines. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 379, 120798. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Ji, F.; Sun, Z. Transformation and environmental chemical characteristics of hazardous trace elements in an 800 t/d waste incineration thermal power plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170693. [CrossRef]

- Moon, D. H.; Wazne, M. Impact of brownmillerite hydration on Cr (VI) sequestration in chromite ore processing residue. Geosci. J. 2011, 15, 287-296. [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, G. P.; Zanoletti, A.; Ducoli, S.; Zacco, A.; Iora, P.; Invernizzi, C. M.; Bontempi, E. Accelerated and natural carbonation of a municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) fly ash mixture: Basic strategies for higher carbon dioxide sequestration and reliable mass quantification. Environ. Res. 2023, 217, 114805. [CrossRef]

- Goni, S.; Guerrero, A. Accelerated carbonation of Friedel's salt in calcium aluminate cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33(1), 21-26. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, K; Chen, L; Yuan, Q. Review on accelerated carbonation of calcium-bearing minerals: Carbonation behaviors, reaction kinetics, and carbonation efficiency improvement. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 108826. [CrossRef]

- Renforth, P. The negative emission potential of alkaline materials. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10(1), 1401. [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, K.; Brück, F.; Pohl, S.; Mansfeldt, T.; Weigand, H. Technically exploitable mineral carbonation potential of four alkaline waste materials and effects on contaminant mobility. Greenhouse Gases Sci. Technol. 2021, 11(3), 506-519. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mao, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, W. Highly efficient carbonation and dechlorination using flue gas micro-nano bubble for municipal solid waste incineration fly ash pretreatment and its applicability to sulfoaluminate cementitious materials. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 353, 120163. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Kawai, T.; Kamijima, Y.; Shinohara, S.; Tanaka, M. Application of ultrafine bubbles for enhanced carbonation of municipal solid waste incineration ash during direct aqueous carbonation. Next Sustain. 2024, 3. [CrossRef]

- Doka, G. Life cycle inventories of municipal waste incineration with residual landfill & FLUWA filter ash treatment. 2015 Doka Life Cycle Assessments, Zurich, Switzerland.

- Van Gerven, T.; Van Keer, E.; Arickx, S.; Jaspers, M.; Wauters, G.; Vandecasteele, C. Carbonation of MSWI-bottom ash to decrease heavy metal leaching, in view of recycling. Waste Manage. 2005, 25(3), 291-300. [CrossRef]

- Rendek, E.; Ducom, G.; Germain, P. Carbon dioxide sequestration in municipal solid waste incinerator (MSWI) bottom ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 128(1), 73-79. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, L.; Tribaudino, M.; Matteis, C. D.; Funari, V. Particle size and potential toxic element speciation in municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) bottom ash. Sustainability 2021, 13(4), 1911. [CrossRef]

- Loginova, E.; Volkov, D. S.; Van De Wouw, P. M.; Florea, M. V.; Brouwers, H. J. Detailed characterization of particle size fractions of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 866-874. [CrossRef]

- Destefanis, E.; Caviglia, C.; Bernasconi, D.; Bicchi, E.; Boero, R.; Bonadiman, C.; Confalonieri, G.; Corazzari, I.; Mandrone, G.; Pastero, L.; Pavese, A.; Wehrung, Q. Valorization of MSWI bottom ash as a function of particle size distribution, using steam washing. Sustainability 2020, 12(22), 9461. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y. W.; Ghyselbrecht, K.; Santos, R. M.; Meesschaert, B.; Martens, J. A. Synthesis of zeolitic-type adsorbent material from municipal solid waste incinerator bottom ash and its application in heavy metal adsorption. Catal. Today 2012, 190(1), 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Um, N. Effect of Cl removal in MSWI bottom ash via carbonation with CO2 and decomposition kinetics of Friedel’s salt. Mater. Trans. 2019, 60(5), 837-844. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xu, B.; Yi, Y. Effects of accelerated carbonation on fine incineration bottom ash: CO2 uptake, strength improvement, densification, and heavy metal immobilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 143714. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cetin, B.; Likos, W. J.; Edil, T. B. Impacts of pH on leaching potential of elements from MSW incineration fly ash. Fuel 2016, 184, 815-825. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. D.; Song, Y.; Shakya, S.; Lim, C.; Ahn, J. W. In situ carbonation mediated immobilization of arsenic oxyanions. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 383, 121911. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. J.; Lee, S. S.; Fenter, P.; Myneni, S. C.; Nikitin, V.; Peters, C. A. Carbonate coprecipitation for Cd and Zn treatment and evaluation of heavy metal stability under acidic conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57(8), 3104-3113. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, Y.; Fang, M. Carbonation of municipal solid waste gasification fly ash: effects of pre-washing and treatment period on carbon capture and heavy metal immobilization. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119662. [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Baciocchi, R.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; Hills, C. D.; Carey, P. J. Current status and perspectives of accelerated carbonation processes on municipal waste combustion residues. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2007, 135, 55-75. [CrossRef]

- Jianguo, J.; Maozhe, C.; Yan, Z.; Xin, X. Pb stabilization in fresh fly ash from municipal solid waste incinerator using accelerated carbonation technology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161(2-3), 1046-1051. [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Xiong, Z.; Tian, C.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C. Influence of carbonation under oxy-fuel combustion flue gas on the leachability of heavy metals in MSWI fly ash. Waste Manage. 2017, 67, 171-180. [CrossRef]

- Bogush, A. A.; Stegemann, J. A.; Roy, A. Changes in composition and lead speciation due to water washing of air pollution control residue from municipal waste incineration. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 361, 187-199. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Molinari, S.; Dalconi, M. C.; Valentini, L.; Bellotto, M. P.; Ferrari, G.; Artioli, G. Mechanistic insights into Pb and sulfates retention in ordinary Portland cement and aluminous cement: Assessing the contributions from binders and solid waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131849. [CrossRef]

- Baciocchi, R.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; Prigiobbe, V.; Von Zedwitz, V. N.; Steinfeld, A. CO2 sequestration by direct gas− solid carbonation of air pollution control (APC) residues. Energy Fuels 2006, 20(5), 1933-1940. [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, G.; Van Gerven, T.; Vandecasteele, C. Antimony leaching from MSWI bottom ash: modelling of the effect of pH and carbonation. Waste Manage. 2012, 32(2), 278-286. [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, G.; Van Gerven, T.; Snellings, R.; Verbinnen, B.; Elsen, J.; Vandecasteele, C. Stability of pyrochlores in alkaline matrices: solubility of calcium antimonate. Appl. Geochem. 2011, 26(5), 809-817. [CrossRef]

- Verbinnen, B.; Van Caneghem, J.; Billen, P.; Vandecasteele, C. Long term leaching behavior of antimony from MSWI bottom ash: influence of mineral additives and of organic acids. Waste Biomass Valor. 2017, 8, 2545-2552. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.; Scholz, P.; Kalbe, U.; Caliebe, W.; Tayal, A.; Vasala, S. J.; Simon, F. G. Speciation of antimony and vanadium in municipal solid waste incineration ashes analyzed by XANES spectroscopy. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 2024, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Baciocchi, R.; Costa, G.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; Prigiobbe, V. Comparison of different reaction routes for carbonation of APC residues. Energy Proced. 2009, 1(1), 4851-4858. [CrossRef]

- Costa, G. P. Enhanced Separation of Incinerator Bottom Ash: Composition and Environmental Behaviour of Separated Mineral and Weakly Magnetic Fractions. Waste Biomass Valor. 2020, 11, 7079-7095. [CrossRef]

- Santos, R. M.; Mertens, G.; Salman, M.; Cizer, Ö.; Van Gerven, T. Comparative study of ageing, heat treatment and accelerated carbonation for stabilization of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash in view of reducing regulated heavy metal/metalloid leaching. J. Environ. Manage. 2013, 128, 807-821. [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Chan, W. P.; Dou, X.; Lisak, G.; Chang, V. W. C. Kinetics and modeling of trace metal leaching from bottom ashes dominated by diffusion or advection. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 719, 137203. doi:j.scitotenv.2020.137203.

- Mantovani, L.; De Matteis, C.; Tribaudino, M.; Boschetti, T.; Funari, V.; Dinelli, E.; Pelagatti, P. Grain size and mineralogical constraints on leaching in the bottom ashes from municipal solid waste incineration: a comparison of five plants in northern Italy. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1179272. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. H.; Ambreen, K.; Fatima, G.; Kumar, S. Assessment of health risks with reference to oxidative stress and DNA damage in chromium exposed population. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 430, 68-74. [CrossRef]

- Naz, A.; Mishra, B. K.; Gupta, S. K. Human health risk assessment of chromium in drinking water: a case study of Sukinda chromite mine, Odisha, India . Expos. Health 2016, 8, 253-264. [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, C.; Pollastri, S.; Mantovani, L.; Tribaudino, M. Potentially toxic elements speciation in bottom ashes from a municipal solid waste incinerator: A combined SEM-EDS, µ-XRF and µ-XANES study. Environ. Adv. 2024, 15, 100453. [CrossRef]

- Um, N.; Nam, S. Y.; Ahn, J. W. Effect of accelerated carbonation on the leaching behavior of Cr in municipal solid waste incinerator bottom ash and the carbonation kinetics. Mater. Trans. 2013, 54(8), 1510-1516. [CrossRef]

- Luther, S.; Brogfeld, N.; Kim, J.; Parsons, J. G. Study of the thermodynamics of chromium (III) and chromium (VI) binding to iron (II/III) oxide or magnetite or ferrite and manganese (II) iron (III) oxide or jacobsite or manganese ferrite nanoparticles. . Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 400, 97-103. [CrossRef]

- Hai, J.; Liu, L.; Tan, W.; Hao, R.; Qiu, G. Catalytic oxidation and adsorption of Cr(III) on iron-manganese nodules under oxic conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 122166. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ju, T.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; Yang, C.; Lv, H.; Fan, Y. The preparation of a novel iron/manganese binary oxide for the efficient removal of hexavalent chromium [Cr (vi)] from aqueous solutions. RSC Adv. 2020, 10(18). [CrossRef]

- Ouma, L.; Pholosi, A.; Onani, M. Optimizing Cr (VI) adsorption parameters on magnetite (Fe3O4) and manganese doped magnetite (MnxFe(3-x)O4) nanoparticles. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023, 8(11), 3885-3895. [CrossRef]

- Allegrini, E.; Maresca, A.; Olsson, M. E.; Holtze, M. S.; Boldrin, A.; Astrup, T. F. Quantification of the resource recovery potential of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ashes. Waste Manage. 2014, 34(9), 1627-1636. [CrossRef]

- Pienkoß, F.; Abis, M.; Bruno, M.; Grönholm, R.; Hoppe, M.; Kuchta, K.; Simon, F. G. Heavy metal recovery from the fine fraction of solid waste incineration bottom ash by wet density separation. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 2022, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Sierra, H. M.; Šyc, M.; Korotenko, E. Wet shaking table operating parameters optimization for maximizing metal recovery from incineration bottom ash fine fraction. Waste Manage. 2024, 174, 539-548. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Abis, M.; Kuchta, K.; Simon, F. G.; Grönholm, R.; Hoppe, M.; Fiore, S. Material flow, economic and environmental assessment of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash recycling potential in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128511. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Kong, Q.; Zhu, H.; Long, Y.; Shen, D. Content and fractionation of Cu, Zn and Cd in size fractionated municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 94, 131-137. [CrossRef]

- Beikmohammadi, M.; Yaghmaeian, K.; Nabizadeh, R.; Mahvi, A. H. Analysis of heavy metal, rare, precious, and metallic element content in bottom ash from municipal solid waste incineration in Tehran based on particle size. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13(1), 16044. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; He, P.; Shao, L.; Zhang, H. Metal distribution characteristic of MSWI bottom ash in view of metal recovery. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 52, 178-189. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xu, B.; Yi, Y. Effects of accelerated carbonation on fine incineration bottom ash: CO2 uptake, strength improvement, densification, and heavy metal immobilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143714. [CrossRef]

- Weiksnar, K. D.; Marks, E. J.; Deaderick, M. J.; Meija-Ruiz, I.; Ferraro, C. C.; Townsend, T. G. Impacts of advanced metals recovery on municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash: Aggregate characteristics and performance in Portland limestone cement concrete. Waste Manage. 2024, 187, 70-78. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Water mass | kg | 1 |

| Solid sample mass | g | 25 |

| Liquid-to-solid ratio | - | 40 |

| Pressure | bar | 1.2 |

| Temperature | K | 333 |

| CO2 volumetric flow rate | L/min | 0.4 |

| CO2 concentration | vol.% | 100 |

| Stirrer speed | rpm | 300 |

| Cylinder height x diameter | cm | 16.8 x 10 |

| Sample | Experimental identifier | Duration | Liquid sample names | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous carbonation |

Water washing |

(min) | Aqueous carbonation | Water washing | |||

| WW1 | TCLP2 | WW | TCLP | ||||

| A | A1 | A2 | 50 | AA | AC | AB | AW |

| B | B1 | B2 | 15 | BA | BC | BB | BW |

| C | C1 | C2 | 40 | CA | CC | CB | CW |

| D | D1 | D2 | 30 | DA | DC | DB | DW |

| E | E1 | E2 | 45 | EA | EC | EB | EW |

| A | B | C | D | E | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSA | (m2/g) | 4.182 | 3.125 | 3.955 | 13.487 | 26.844 |

| LOI | wt.% | 21.8 | 23.3 | 12.5 | 20.5 | 38.6 |

| Phase name | Formula | |||||

| CaClOH | CaClOH | - | - | 14.3 | 44.3 | 20.8 |

| Portlandite | Ca(OH)2 | 0.8 | - | 2.1 | 7.2 | 9.8 |

| Lime | CaO | - | - | 1.7 | - | - |

| Sinjarite | 2H2O | - | - | - | 0.9 | - |

| CaCl2·4H2O | 4H2O | - | - | - | 0.6 | - |

| Periclase | MgO | - | 1.4 | 0.8 | - | - |

| Larnite | Ca2SiO4 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 6.7 | - | 1.5 |

| Hatrurite | Ca3SiO5 | - | - | - | - | 1.8 |

| Akermanite | Ca2MgSi2O7 | 1.5 | - | - | - | - |

| Melilite | Ca2(Al,Mg)(Al,Si)2O7 | - | 1.3 | - | - | - |

| Gehlenite | Ca2Al2SiO7 | - | - | 3 | - | - |

| Merwinite | Ca3Mg(SiO4)2 | - | 0.8 | 2.4 | - | - |

| Magnesite | MgCO3 | - | - | - | - | 0.3 |

| Calcite | CaCO3 | 5.5 | 1.9 | - | 15.1 | 3.7 |

| Quartz | SiO2 | 1.6 | 0.6 | - | - | - |

| Cristobalite | SiO2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | - | - | - |

| Halite | NaCl | - | 25.1 | 6.4 | 0.7 | 4.1 |

| Hydrocalumite | Ca2Al(OH)6(Cl,OH)·2H2O | 14.2 | 0.5 | - | - | - |

| Katoite | Ca3Al2(OH)12 | 12.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Calcium Alum. Nitrate | Ca₃Al₂(NO₃)₁₂ | 2.8 | - | - | - | - |

| Hydroxiapatite | Ca5(PO4)3OH | 4.0 | - | - | - | - |

| Archerite | KHPO4 | 0.1 | -- | - | - | - |

| Anhydrite | CaSO4 | - | 11.3 | 4.9 | - | 1.2 |

| Bassanite | 0.5H2O | - | 4.5 | 1.8 | - | - |

| Hannebachite | 0.5H2O | - | - | - | 19.1 | - |

| Sylvite | KCl | - | 12.1 | 4.9 | - | 1.3 |

| Ilmenite/Perovskite | (Fe,Ca)TiO3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 | - | - |

| K-tetrachlorozincate | K2ZnCl4 | - | 0.5 | - | - | - |

| Amorphous | 51.7 | 38.2 | 41.8 | 12.0 | 55.5 | |

| Oxide | ||||||

| Na2O | 1.28 | 14.72 | 5.36 | 0.1 | 4.35 | |

| MgO | 2.45 | 1.79 | 0.81 | 0.56 | 0.54 | |

| Al2O3 | 18.67 | 1.23 | 1.83 | 0.18 | 0.39 | |

| SiO2 | 12.08 | 5.05 | 3.89 | 0.49 | 1.86 | |

| P2O5 | 2.81 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.08 | |

| SO3 | 2.53 | 12.33 | 7.41 | 15.08 | 8.04 | |

| Cl | 2.40 | 24.21 | 15.14 | 5.28 | 19.49 | |

| K2O | 0.75 | 14.09 | 4.99 | 0.46 | 2.49 | |

| CaO | 50.21 | 15.10 | 54.80 | 76.70 | 61.40 | |

| TiO2 | 1.78 | 0.58 | 1.25 | - | - | |

| Cr2O3 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | - | - | |

| MnO | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| Fe2O3 | 3.17 | 1.05 | 1.23 | 0.63 | 0.54 | |

| NiO | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | - | - | |

| CuO | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.11 | - | 0.03 | |

| ZnO | 0.85 | 6.38 | 1.32 | 0.16 | 0.45 | |

| SrO | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.04 | |

| ZrO2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | - | - | |

| Ag2O | 0.16 | - | - | - | - | |

| Sb2O3 | - | 0.31 | 0.13 | - | - | |

| BaO | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.12 | - | - | |

| PbO | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.02 | - |

| Mineral | Equation of carbonation |

|---|---|

| Quicklime | |

| Portlandite | |

| Calcium chlorohydroxide | |

| Calcium chloride hydrate | |

| Hatrurite | |

| Larnite | |

| Periclase | |

| Brucite | |

| Hydrocalumite | |

| Katoite | |

| Mayenite | |

| Ettringite |

| Exp. identifiers | A1 | B1 | C1 | D1 | E1 | A2 | B2 | C2 | D2 | E2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (%) | 2.6 | 52.2 | 25.8 | 34.2 | 13.8 | 5.4 | 51.4 | 21.8 | 28.4 | 27.8 |

| Unit | A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. identifier | A1 | B1 | C1 | D1 | E1 | |

| % | 10.8 | 0 | 19.9 | 24.7 | 22.3 | |

| σ | % | 3.7 | 0 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 7.7 |

| Duration | s | 1455 | 0 | 725 | 1050 | 1672 |

| L | 1.05 | 0 | 0.96 | 1.73 | 2.42 | |

| gCO2/kg | 101.1 | 0 | 93 | 167 | 244.5 | |

| gCO2/kg | 365.3 | 56 | 392.9 | 458.2 | 425.3 | |

| % | 27.7 | 0 | 23.7 | 36.5 | 57.5 |

| Aqueous carbonation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AC | BA | BC | CA | CC | DA | DC | EA | EC | ||

| pH | - | 7.72 | 8.02 | 7.37 | 8.12 | 7.39 | 8.52 | 7.5 | 7.94 | 7.24 | 7.85 |

| EC | mS/cm | 2.77 | 0.696 | 21.5 | 3.75 | 13.67 | 2.03 | 13.76 | 2.61 | 12.65 | 7.86 |

| Water washing | |||||||||||

| AB | AW | BB | BW | CB | CW | DB | DW | EB | EW | ||

| pH | - | 11.44 | 11.45 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 12.06 | 12.1 | 11.96 | 12.01 | 12.12 | 11.45 |

| EC | mS/cm | 2.5 | 1.634 | 20.8 | 3.76 | 18.08 | 8.82 | 17.12 | 10.04 | 15.84 | 1.634 |

| Wastewaters | Leachates from TCLP | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample names | A | B | C | D | E | A | B | C | D | E | |

| Experiments | AA/AB | AC/AW | BA/BB | BC/BW | CA/CB | CC/CW | DA/DB | DC/DW | EA/EB | EC/EW | |

| Al | % | -99.5 | n.d. | -69.1 | -97.5 | -100.0 | -98.1 | -80.9 | -94.3 | n.d. | -100.0 |

| Cr | % | +53.6 | +3.4 | +26.5 | -79.4 | -83.6 | +83.7 | +21.1 | +18.7 | -82.6 | -77.9 |

| Mn | % | +76.5 | +22.4 | +99.1 | +98.7 | +98.4 | +21.6 | +20.4 | -52.7 | +93.3 | +22.6 |

| Fe | % | -19.7 | -12.0 | -29.7 | -15.4 | +74.8 | +49.9 | -11.7 | -94.0 | -35.2 | -84.2 |

| Co | % | +55.4 | +52.2 | +97.6 | +86.0 | +95.5 | -4.5 | +33.2 | -74.2 | -78.6 | -64.5 |

| Ni | % | +70.6 | +12.6 | +93.2 | +72.0 | +86.7 | -37.8 | +37.3 | -86.5 | -96.9 | -66.3 |

| Cu | % | -55.9 | +1.3 | +13.6 | -82.0 | +17.4 | -72.3 | -2.4 | -83.1 | -98.1 | -83.7 |

| Zn | % | -26.3 | +68.3 | -29.2 | +24.1 | +33.4 | -84.7 | -6.4 | -90.0 | -98.8 | -94.9 |

| As | % | +34.8 | +1.9 | +76.0 | -20.6 | +29.5 | -33.2 | -12.9 | -29.6 | -11.0 | -55.6 |

| Cd | % | +30.0 | +13.2 | +98.7 | +92.8 | +97.2 | +21.7 | -59.2 | -78.2 | -90.9 | -100.0 |

| Sb | % | +89.7 | +91.6 | +97.1 | +75.2 | +57.9 | +85.0 | +6.1 | +86.4 | +86.3 | +86.3 |

| Pb | % | -79.6 | -11.3 | -95.7 | -97.4 | -4.2 | -86.4 | -9.4 | -98.8 | -98.5 | -98.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).