1. Introduction

Most modern quantum computers are built on superconducting (SC) transmon qubits incorporating Josephson junctions (JJs) made of aluminum oxide between two aluminum (Al) electrodes [

1,

2,

3]. Niobium (Nb) is widely used for RF resonators due to its high critical temperature and well-established lithographic patterning, which enables the control, readout, and coupling of multiple qubits in superconducting quantum circuits [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. To achieve scalable multi-qubit systems, qubit states require long relaxation times (

) and dephasing times (

), typically greater than 100

s [

10,

11,

12]. Significant efforts have been made to study pair-breaking and loss mechanisms to extend

and

[

1,

13]. Microwave dielectric losses at metal-dielectric interfaces, such as at Nb-substrate boundaries, have been one of the limiting factors for qubit lifetimes. Intrinsic losses in bulk materials should theoretically permit lifetimes exceeding 1 ms. Despite being a type II superconductor with high critical temperature

= 9.3 K, Nb used in microwave circuits for transmon qubits has been identified as a potential source of decoherence. Therefore, understanding the decoherence and loss mechanisms in Nb superconducting state is crucial for improving qubit performance. Shorter-than-expected

and

times are often attributed to two-level system (TLS) losses below 1 K and non-equilibrium quasiparticle (QP) generation above 1 K, stemming from factors such as nonuniform surface morphology, defects, native Nb oxide, and ionizing radiation [

15,

16,

17,

18].

The ultrafast pump-probe technique using femtosecond (fs) laser pulses is a powerful and versatile method for investigating non-equilibrium Cooper pair breaking and quasiparticle dynamics in superconductors. Transient signals measured after ultrafast excitation provide exclusive insight into the out-of-equilibrium processes arising from the conversion between the superconducting condensate and quasiparticles (QPs). In our fs-resolved transient reflectivity scheme, weak 1.2 eV laser pulses break only a small fraction of Cooper pairs in the Nb samples. This non-thermal depletion of the superconducting condensate induces a noticeable change in reflectivity at the probe frequency, as illustrated schematically in

Figure 1a. This scheme allows us to measure the transient changes in reflectivity as a function of time delay, temperature, and magnetic field in Nb superconducting states. According to the well-established Rothwarf-Taylor (R-T) model [

19],

directly corresponds to the thermal quasiparticle density

in the weak perturbation regime, where the depletion of superfluid density

[

20].

To differentiate the quasiparticle (QP) recombination process from electron and phonon temperature changes driven by laser heating, experiments are conducted at two temperature ranges: above and below

. The superconducting response is obtained by isolating the low-temperature signal from the high-temperature one [

21]. For instance, in optical pump-probe experiments on Pb [

22], femtosecond laser pulses rapidly raise the electron temperature, followed by a fast decay ( 1 ps) as energy transfers to QPs and high-frequency phonons (HFPs). HFPs, which have energies exceeding the superconducting gap, break Cooper pairs until all energy dissipates through electron-phonon interactions or thermal diffusion. In this weak perturbation regime, the photoinduced QP density is much smaller than the thermal equilibrium QP density. To maintain weak perturbation, the laser fluence should be kept low (about 1

) [

21,

22,

23] to avoid breaking a large number of Cooper pairs. Initially, photo-excited hot electrons decay rapidly, followed by a slower decay of HFPs. After the photoinduced QPs reach maximum population within a few picoseconds, a slower decay process follows, governed by HFP decay and QP recombination (the phonon bottleneck region). Moreover, it is expected that a magnetic field would significantly affect non-equilibrium QP generation and decay processes, providing a means to evaluate the robustness of superconducting coherence. However, ultrafast pump-probe experiments exploring the magnetic field dependence of non-equilibrium superconducting dynamics have not yet been conducted on Nb superconductors.

Despite several pump-probe studies on QP dynamics in unconventional superconductors such as cuprates [

20,

25,

26] and pnictides [

27,

28,

29], fs studies of equilibrium QP dynamics on conventional BCS type SCs are relatively rare. The photoincluded dynamic pair breaking and recombination process is non-thermal equilibrium phenomena driven by ultrafast laser. In this nonequilibrium state, Rothwarf and Taylor suggested that the QP pair recombination coupled with high frequency phonon (HFP) and Cooper pairs [

19,

20,

30,

31]. Furthermore, to distinguish QP recombination process from electron and phonon temperature driven by laser heating, experiments are performed at two temperature ranges (above and below

). The superconducting response can be obtained by isolating the difference between low temperature signal from high temperature one [

21]. For example, in an optical pump-probe experiment on Pb [

22], fs laser pulses can rapidly heat electron temperature followed by fast decay ∼1ps and transfer energy to QPs and HFPs. HFPs have larger energy than SC gap and break Cooper pairs until all of their energy dissipates via electron phonon interaction or thermal diffusion. In this weak perturbation regime, photoinduced QP density is much smaller than thermal equilibrium QP one. To achieve this weak perturbation condition, the laser flunce should be low (on the order of 1

) [

21,

22] to avoid breaking large density of Cooper pairs. Initial photo-excited hot electrons decay relatively fast followed by relatively slow decaying HFPs. After photoinduced QP reached the maximum population in a few ps, then it follows slow decay process by HFP decay and QP recombination (phonon bottleneck region). In addition, one expect that magnetic field will significantly influence non-equilibrium QP generation and decay processes which can be used to benchmark the robortness of the superconduting coherence. However, ultrafast pump-probe experiments exploring magnetic field dependence of non-equilibrium superconducting dynamics have never been conducted on Nb superconductors until now.

In this study, we conducted an in-depth investigation into QP generation and relaxation dynamics in superconducting Nb sourced from radio-frequency cavities, as well as various Nb resonator films fabricated using deposition techniques such as DC sputtering and high-power impulse magnetron sputtering (HiPIMS). We obtained QP densities from pump-probe signals under different temperature and magnetic field conditions. Our results reveal both shared characteristics and distinct differences in the temperature- and magnetic field-dependent behavior of the Nb samples. Significantly, fs-resolved QP relaxation under an applied magnetic field demonstrated a clear correlation between QP density and the quality factor of resonators. These findings provide valuable insights into QP generation and non-equilibrium dynamics in Nb resonators and lay the groundwork for systematic measurements that could guide strategies to develop highly coherent qubit devices.

2. Materials and Methods

Nb thin films of different growth methods and bulk Nb from superconducting radio frequency (SRF) cavity are used in the experiments and summarized in

Table 1. Sputter coated Nb thin film samples of thickness t=175 nm are grown by HiPIMS, DC high power, and DC low to high (DC LH) power sputtering on intrinsic Si (001) wafer at Rigetti Computing. The deposition rate for HiPIMS is ∼5.1 nm/min and DC high power deposition rate is ∼25 nm/min. For DC LH sample, the low power deposition rate is 5.3 nm/min to 30 nm thickness followed by 145 nm deposition with high power. Average grain sizes of sputtered samples are 44n m for HiPIMS, 69 nm for DC high and 65 nm for DC LH respectively. Thick t=2 mm SRF sample is SRF cavity cutout from Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. The poly crystalline SRF sample has large average grain size about 50

compared to 44-69 nm in sputter coated samples. Detailed sample information and growth methods are described in elsewhere [

32,

33]. The SRF cavity cutout sample is mechanically polished for optical measurement. To avoid oxidation, the sample was polished with oil-based diamond powders and rinsed with isopropyl alcohol then dried with nitrogen gas. Sputter coated thin film samples are cut to 10×10 mm

2 with diamond pen from 3 inch wafer. All samples are kept in dry box before mounting in vacuum cryostat to avoid contamination and moisture absorption. Thermal conductivity of Nb itself is ∼100 kW/m·K much higher than Si ∼ 80 W/m·K near

.

Ultrafast pump-probe measurements were performed using a femtosecond pulsed laser with a 7 Tesla dry cryostat. The experimental setup employed a normal reflection geometry for pump-probe spectroscopy [

34]. A 1250 nm laser output was split into two amplified arms via optical fibers, generating 20 fs light pulses at 1500 nm. One arm served as the pump beam, while the other functioned as the probe beam at 750 nm, generated through second harmonic generation. The pump and probe beams were overlapped using a dichroic beam combiner and focused with a 100 mm focal length lens in a collinear geometry. Samples were mounted facing the top window in the cryostat, with the magnetic field applied perpendicular to the sample surface.

A silicon balanced detector paired with a lock-in amplifier was used to detect reflectivity changes, with a 40 kHz mechanical chopper placed in the pump beam path. The temporal overlap of the pump and probe beams was controlled via a motorized linear delay stage in the pump path. The reflected probe signal was directed to the balanced detector, with a reference beam of equal optical path length focused onto the detector’s reference channel to cancel out noise. A 900 nm short-pass filter was used to block the 1500 nm pump beam entirely. The laser’s focal point diameter was approximately 100

m, with pump fluences ranging from 1 to 7

for fluence dependence, and the probe fluence kept at around ∼0.3

to ensure minimal disturbance. A common pump fluence of 3

was used for most measurements to achieve both a high signal-to-noise ratio and operation within the weak perturbation regime.The optical skin depth of Nb, calculated as

, was found to be 19 nm at 750 nm and 15 nm at 1.5

m, based on optical constants [

35] as shown in Appendix

Figure A1. The analysis of QP dynamics under varying magnetic fields, along with a comprehensive comparison of the ultrafast superconducting behavior across different Nb samples, will be discussed in detail in the following sections. Additionally, the thin film sample’s residual resistivity ratio (RRR = R(290K)/R(10K)) and the power-dependent quality factor

were measured using fabricated Nb resonators at the qubit operating frequency of 5 GHz.

3. Results and Discussions

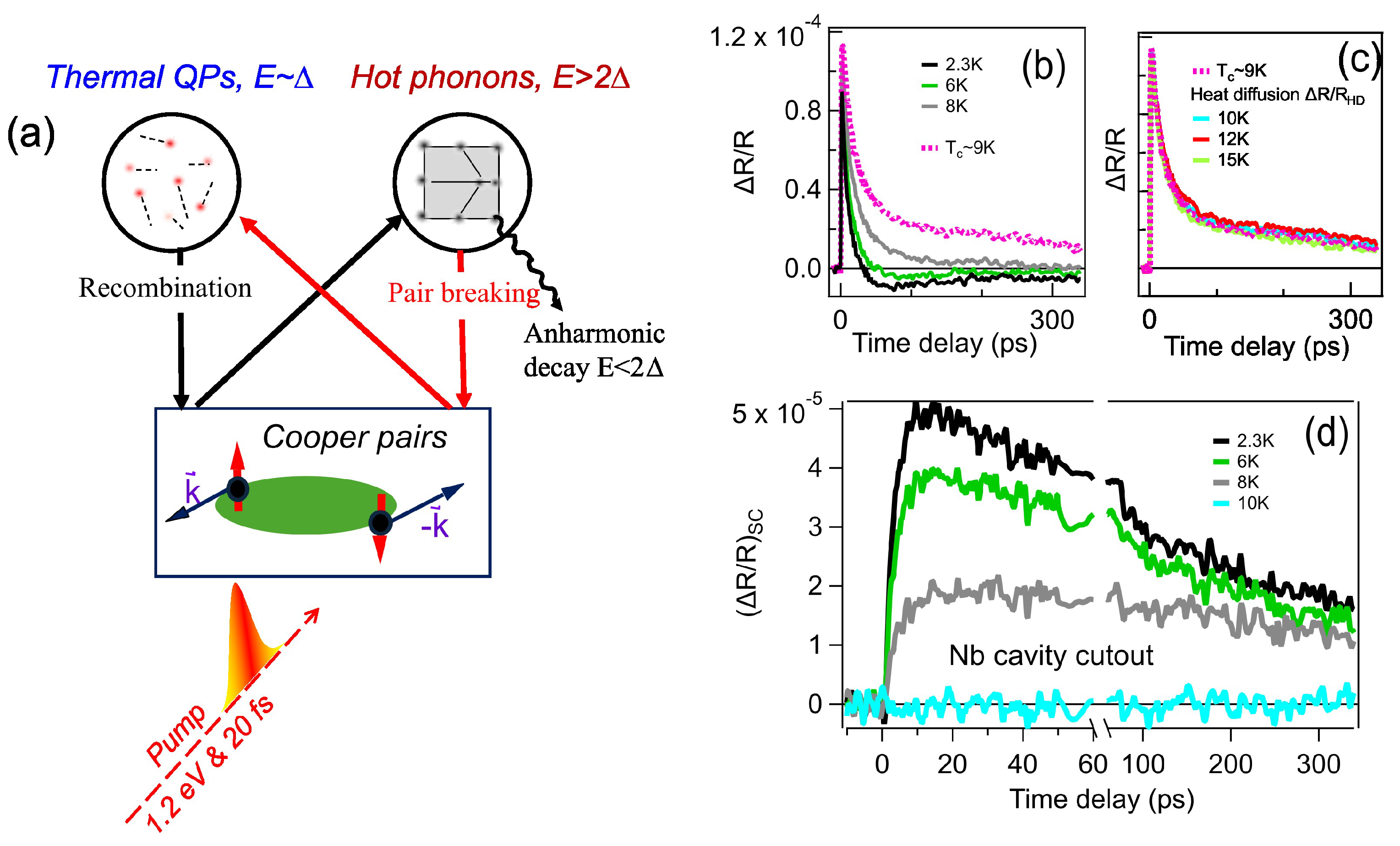

Figure 1(b,c) presents the representative pump-probe responses of the photoinduced reflectivity change,

, at 2.3 K, 6 K, and 8 K in the superconducting (SC) state, as well as in the normal state above the

of the Nb cavity cutout sample. Both

signals exhibit a sharp rise time of approximately 3 ps, followed by a slower decay lasting over 300 ps. The rapid increase is attributed to QP generation from initial pair-breaking by the laser pulse, followed by electron-phonon scattering, while the slower decay is mainly due to high-frequency phonon relaxation and thermal diffusion. Thermal diffusion primarily occurs vertically rather than laterally, as the laser focal spot, measuring tens of micrometers, is significantly larger than the optical skin depth (∼15 nm). In Fig.

Figure 1(b),

signal includes both the photoinduced QP decay process and the phonon-mediated thermalization process. The latter components of

shown in Fig.

Figure 1(c) exhibit minimal temperature dependence for small temperature changes (≤ 10K). Subtracting the

of the normal state from the average

isolates the photoinduced QP dynamics in the SC state

, as shown in

Figure 1(d). This

component, absent above the critical temperature, shows both a slower rise time of ∼5 ps and a slower decay compared to the dynamics observed prior to subtraction. Our data clearly demonstrate the capability to independently measure the dynamics of quasiparticle generation/relaxation and hot phonon thermal diffusion processes. This methodology will be extended to investigate other Nb samples fabricated using various methods.

Theoretical QP dynamic model was developed for non-equilibrium states from laser excitation [

19,

20,

30,

31]. Rothwarf and Taylor (R-T) proposed two coupled equations to relate the QP recombination and non-negligible high frequency phonons (HFPs) created by initial energetic QP during laser heating. The coupled photoinduced HFP pair breaking and QP recombination process governs the long QP decay dynamics [

19].In the R-T model, phonons generated from quasiparticle (QP) recombination have a high likelihood of being absorbed in a subsequent pair-breaking process. This high-frequency phonon (HFP) can then break a Cooper pair, creating two additional QPs, as illustrated in

Figure 1(a). The recovery of superconductivity results from the decay of photoinduced thermal QPs. This hot-phonon-mediated pair-breaking and recombination process has a longer lifetime than the intrinsic hot-electron decay. QP dynamics also require a detailed balance between phonon generation, decay, and the phonon-driven pair-breaking process [

30]. Since the laser is focused on small area of the sample, hot phonon diffusion should also be considered to analyze the

component for non-equilibrium QP dynamics in SC states.

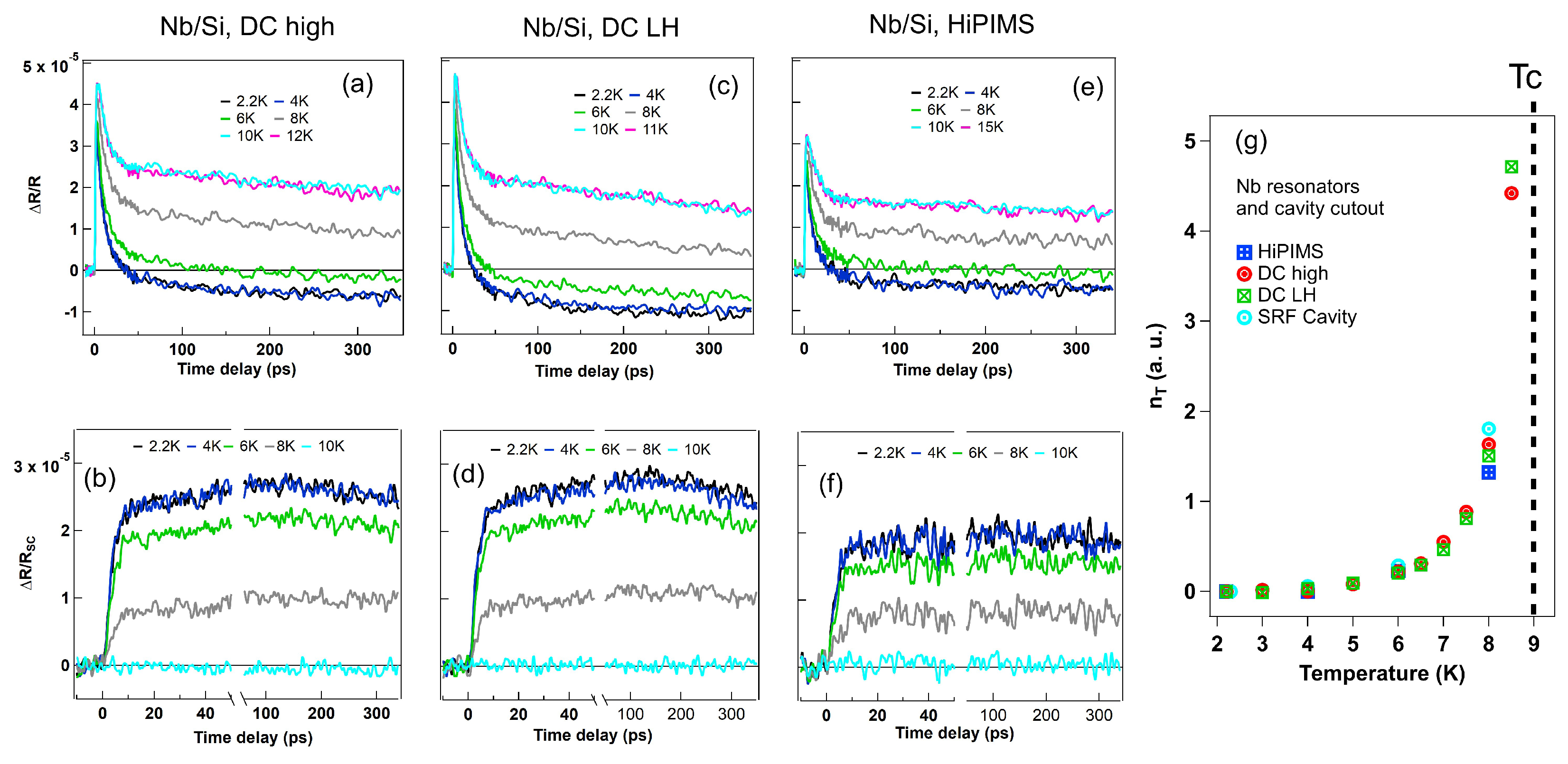

Figure 2 top graphs show temperature dependent

and bottom ones show subtracted, superconducting components

from normal state average traces of DC high power, DC LH power, HiPIMS Nb samples. We emphasize two key points. First, the SRF cavity sample exhibits significantly better thermal diffusion compared to the thin-film samples which accounts for the faster QP decay times (

Figure 1d) observed in the Nb cavity cutout sample compared to Nb thin films. The SRF cavity sample is polycrystalline with an average grain size of 50

, whereas the HiPIMS Nb thin film has a grain size of ∼10s of nm. Smaller grains lead to increased grain boundaries and defects, which act as QP pinning centers that slow recombination. Moreover, HFP diffusion within the optical depth is significantly more efficient in the SRF cavity sample due to its larger grain size, (Figs. 2b-2f). Second, the photoinduced superconducting

signals in

Figure 2(b, d, f) approach to zero as the temperature near

. The signal amplitude directly correlates with QP generation, while the time dependence reflects the QP relaxation dynamics. The temperature dependent thermal equilibrium QP density

is estimated from

, where

is a peak intensity in

in

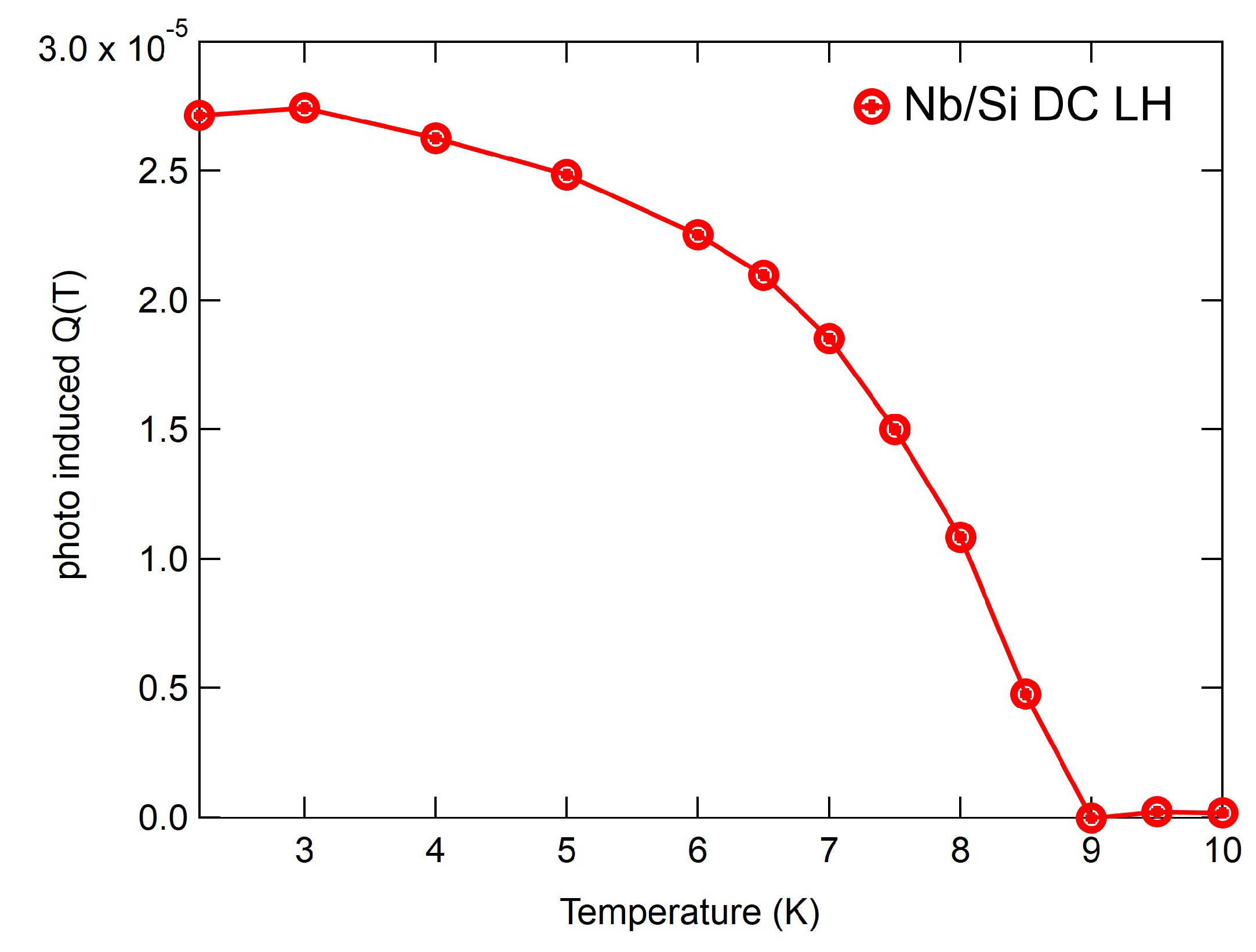

Figure 2(b, d, f).

is obtained from the lowest temperature value at 2.2K. Thermal equilibrium QP density

measured

in

Figure 2(g) agrees well with eq. (1) [

20],

where,

is electronic density of states in unit cell and

is SC gap. And phonon density

at thermal equilibrium is as eq. (2) [

20].

where

is Debye energy and

is number of atoms in unit cell. Initial photoinduced QP density

and excited phonon density

are small compared to

and

in weak perturbation limit, i.e.,

.

Because the incident photon energy ∼ 1 eV is much larger than SC gap

3 meV, initial energetic QP after laser excitation on the sample generates HFP. After energetic QP dissipation in few ps, QP generation and recombination is driven by balanced states between HFP pair breaking and QP recombination as shown in

Figure 1(a) schematic i.e. strong phonon bottleneck region. Thermal-equilibrium QP densities,

, derived from measurements, exhibit an exponential increase with temperature, as shown in

Figure 2(g). Additionally, in the SC state, high-frequency phonon density dissipates heat through electron-phonon interactions and diffusion. The pump-probe signal,

, in SC states includes non-QP contributions, such as rapid electron thermalization followed by slower decay processes from acoustic phonons, carrier diffusion, and phonon diffusion [

28]. The SC contribution,

, is isolated by subtracting the normal-state signal measured above

, which is proportional to

. As shown in Appendix

Figure A2, this quantity diminishes as the temperature approaches

.

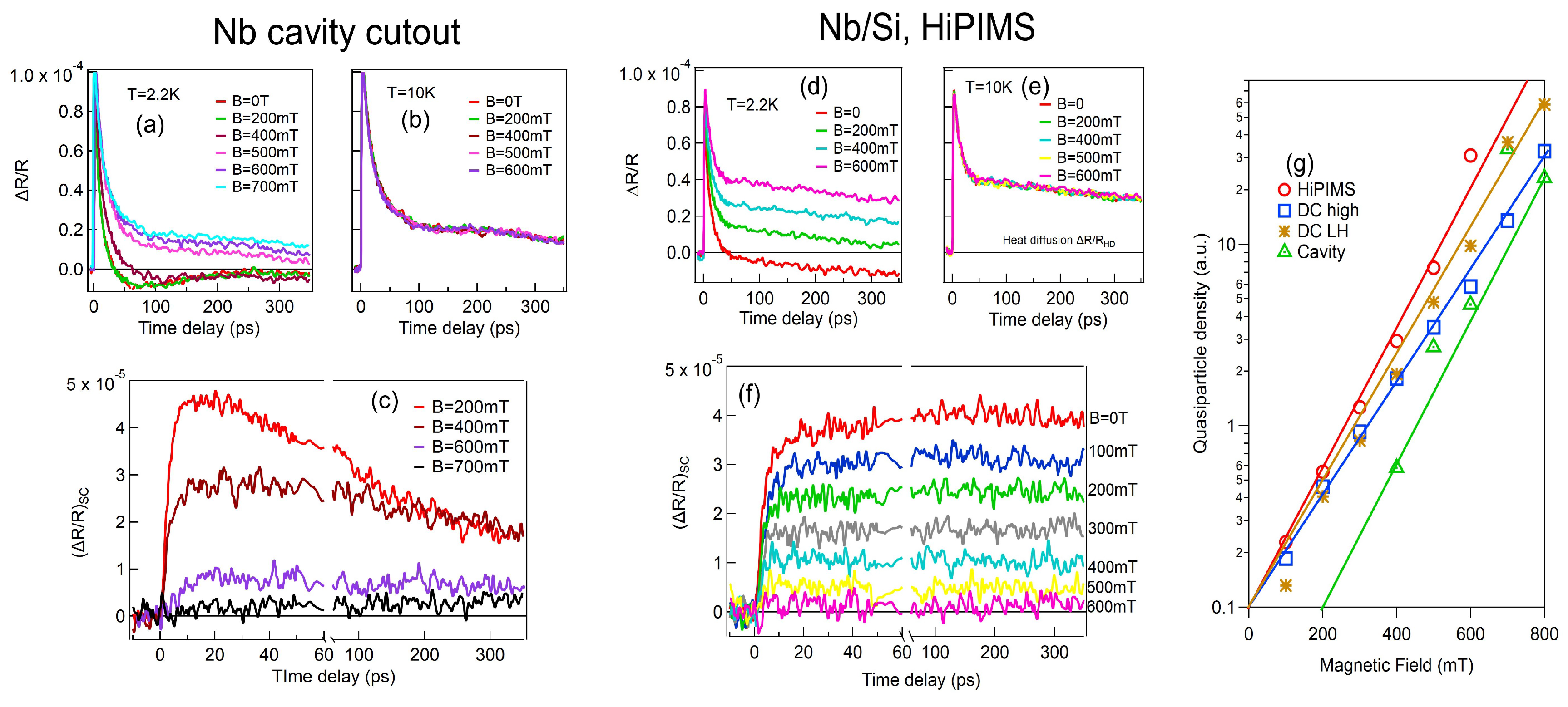

Figure 3(a, b) shows the magnetic field dependence of

on the Nb SRF cavity at 2.2 K and 10 K. The results demonstrate a strong magnetic field dependence of

at 2.2 K, while no clear field dependence is observed at 10 K. The extracted SC component

of the SRF cavity reveals a distinct magnetic field dependence in QP generation, with the majority of Cooper pairs breaking at B>700 mT, as shown in

Figure 3(c). The

behavior of the HiPIMS sample, as shown in Fig.

Figure 3(d, e), resembles that of the SRF cavity samples. The subtracted superconducting component,

, of the HiPIMS sample also displays magnetic field-dependent QP dynamics, though all Cooper pairs break at a lower magnetic field of B∼600 mT, as shown in Fig.

Figure 3(c). Most intriguingly, there is a clear difference in

components under the external magnetic field between the two samples. First, HiPIMS has much longer relaxation time and also requires less magnetic field to break all Cooper pairs as shown in

Figure 3(f) compared to the cavity cutout sample in

Figure 3(c). Other DC sputter samples show similar trends as HiPIMS. Second, the thermalized QP densities

s extracted from photoinduced

signals are plotted together for HIPIMS, DC high, DC LH, SRF cavity as shown in

Figure 3(g) with guided lines. The SRF cavity sample clearly demonstrates the lowest quasiparticle population and the most robust superconducting properties, with a distinct threshold magnetic field required to generate a significant quasiparticle population.The quasiparticle density generation behavior in the SRF cavity sample is succeeded in resilience by the DC High, DC LH, and HiPIMS samples, exhibiting progressively higher densities in that order. Moreover, the QP signals of these thin film samples decrease steadily from 0 to 400 mT without a threshold, whereas the SRF cavity sample shows an uneven reduction in QP signal, generating QPs only at sufficiently high fields. Among the thin-film samples, the magnetic field-induced quasiparticle density exhibits an increasingly steep slope in the order of DC High, DC LH, and HiPIMS. These findings underscore the SRF cavity sample’s superior superconducting properties and high tolerance to pair-breaking perturbations, followed by the DC High, DC LH, and HiPIMS samples, making them progressively suitable for applications requiring highly coherent quantum devices.

We can attribute these differences to the grain heterogeneity and magnetic field penetration into sample. SRF cavity requires stronger magnetic field to break SC states due to the large grains that are more robust in external magnetic field penetration. Low QP density in

indicates that strong magnetic field is needed to penetrate inside the sample. In addition, DC samples tend to produce films with larger grain sizes compared to HiPIMS ones. This difference arises due to the distinct deposition processes and energy distributions in the two techniques [

32]. In general, larger grain size has less grain boundary as flux pinning centers. It is expected that magnetic field can penetrate easily in HiPIMS sample. Therefore, among sputter coated samples, the DC high sample is robust in magnetic field penetration. Assuming thermal diffusion in sputter samples is not much different due to similar overall thickness of Nb and interface layers, one expects that the magnetic field can easily penetrate and break more QP in small grain thin films.

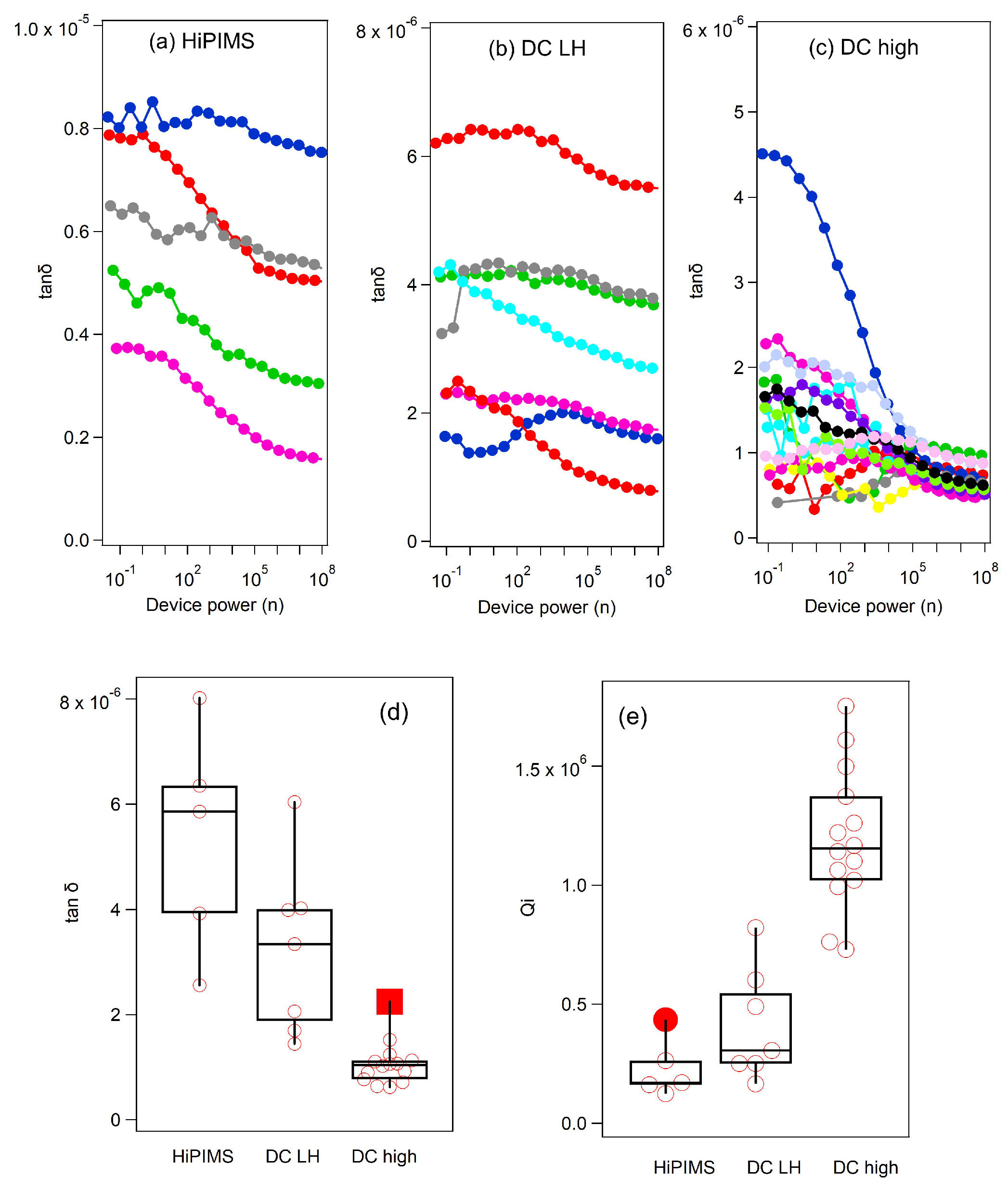

Finally, fs

dynamics under an applied magnetic field shown in

Figure 3g reveals a clear correlation between non-equilibrium QPs and the quality factor of resonators fabricated by using different deposition methods. Thin films Nb RRR=R(290K)/R(10K) and Nb resonator quality factor

are measured and presented in

Figure 4. The Nb thin film RRR values are 4.55 for HiPIMS, 6.66 for DC LH, 6.53 for DC high. The low RRR value of HiPIMS is consistent with smaller grain size compared to DC samples. Also loss tangent

are obtained with

from measured

.

Figure 4 shows loss tangent

and

of RF resonators with different deposition methods. In

Figure 4(a, b, c), different color represents different device power scans on same samples. The power dependent scans show high loss tangent at low power in general. The box plots in

Figure 4(d, f) show median values for different scans. From loss tangent box plot, HiPIMS has highest loss followed by DC LH and DC high. The median values of

are 0.1712

for HiPIMS, 0.3064

for DC LH, 1.141

for DC high. Because the

were measured with resonator only, estimated upper limit

s for qubit device are 13.86

for HiPIMS, 26.15

for DC LH, 55.80

for DC high from

with f=5 GHz qubit operating frequency. These values align with the

results in

Figure 3g, indicating that a smaller QP population and greater resistance to magnetic fields correlate with a higher

for Nb film samples. The Nb cavity cutout sample shows a significantly higher SRF cavity

Q factor, consistent with this conclusion.

4. Conclusions

We measured femtosecond-resolved transient reflectivity in Nb thin film and SRF cavity cutout samples, examining QP dynamics in the superconducting states across various temperatures and magnetic fields. The thermalized QP density and QP decay dynamics below the critical temperature display notably different behaviors based on the sample growth methods. Distinct differences in QP lifetime, density, and thermal diffusion among Nb samples are attributed to grain boundaries and defects.

The thermal diffusion contrasts significantly between thin films and bulk polycrystalline SRF cavities, with the SRF cavity exhibiting more efficient heat conduction. Magnetic field-dependent measurements reveal clear behavioral distinctions between the two sample types, with SRF samples showing stronger superconductivity and faster QP relaxation, characteristics that are highly favorable for applications requiring coherent quantum devices.

Within the thin film samples, the DC high sample shows the lowest loss tangent in RF resonators, followed by DC LH, while HiPIMS has the highest loss tangent, which we attribute to grain boundary effects and grain size variations from different deposition methods. Magnetic-field-dependent thermal equilibrium QP density measurements are consistent with this trend.

Our study further suggests that, in addition to larger grain size and fewer defects to reduce TLS losses and QP pinning, Nb thin film resonators fabricated on high-conductivity substrates such as sapphire could enhance transmon qubit performance. These findings emphasize the critical impact of fabrication techniques on the coherence and performance of Nb-based quantum devices, essential for applications in superconducting qubits and high-energy superconducting radio frequency systems.