Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

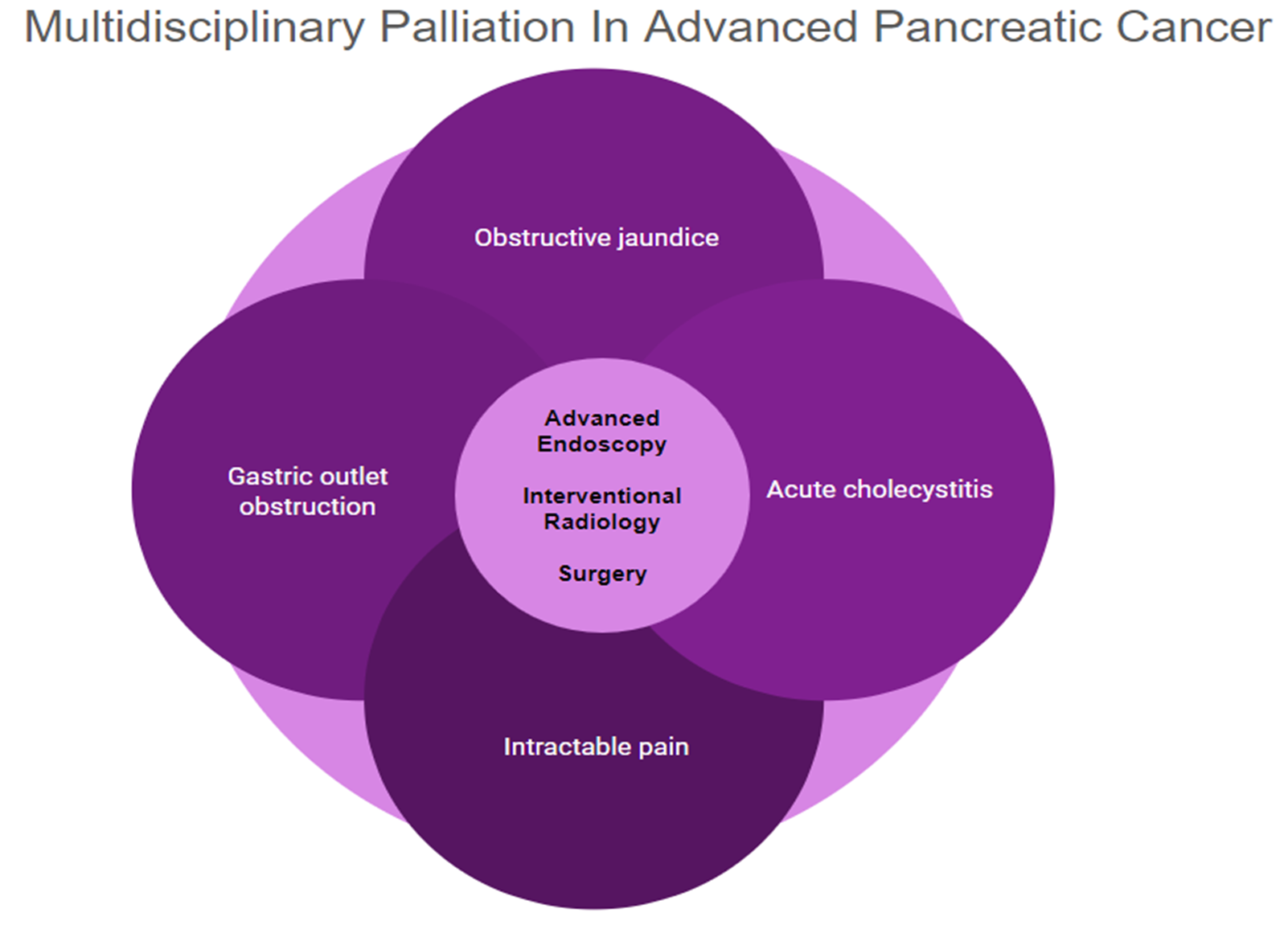

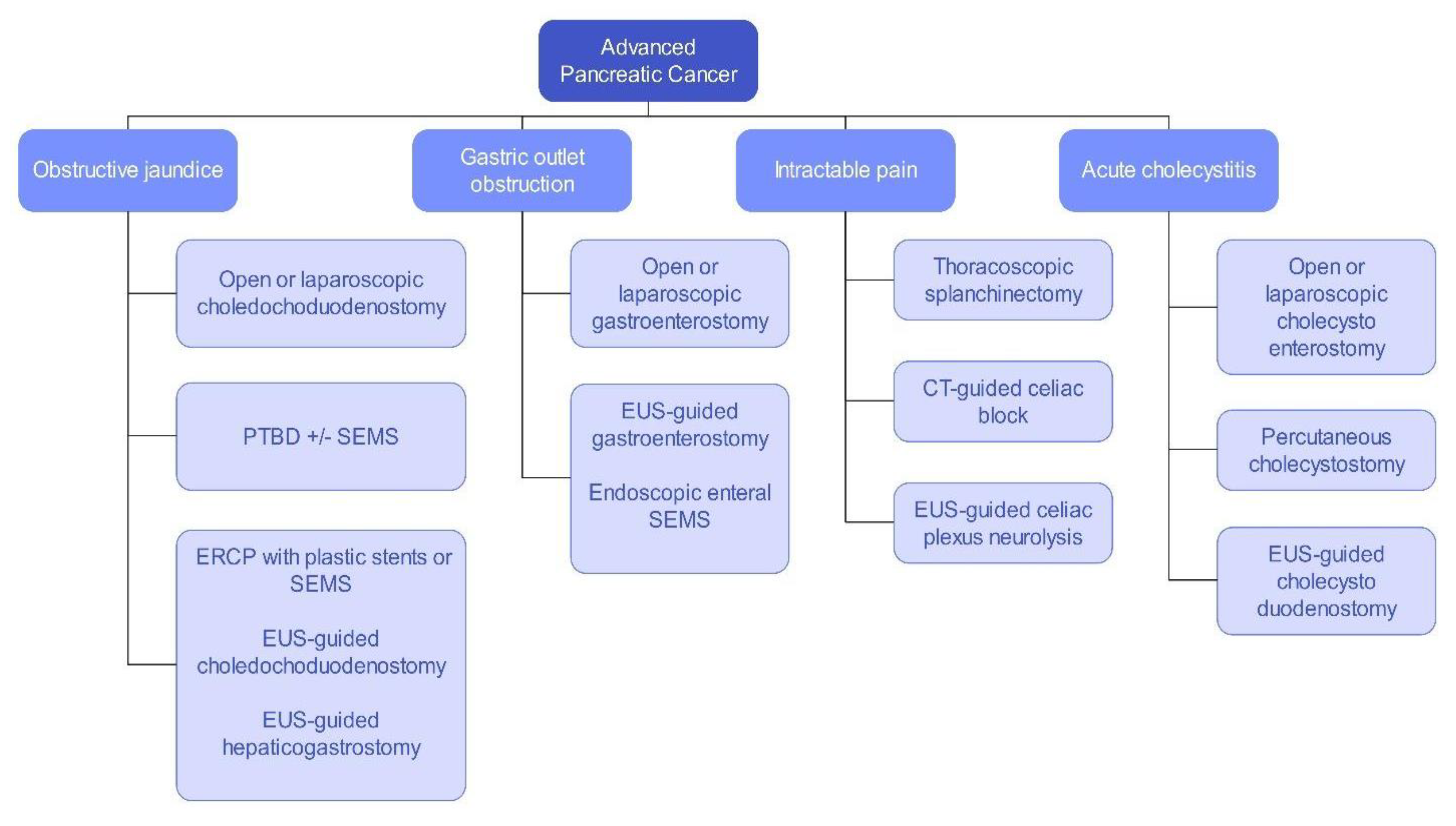

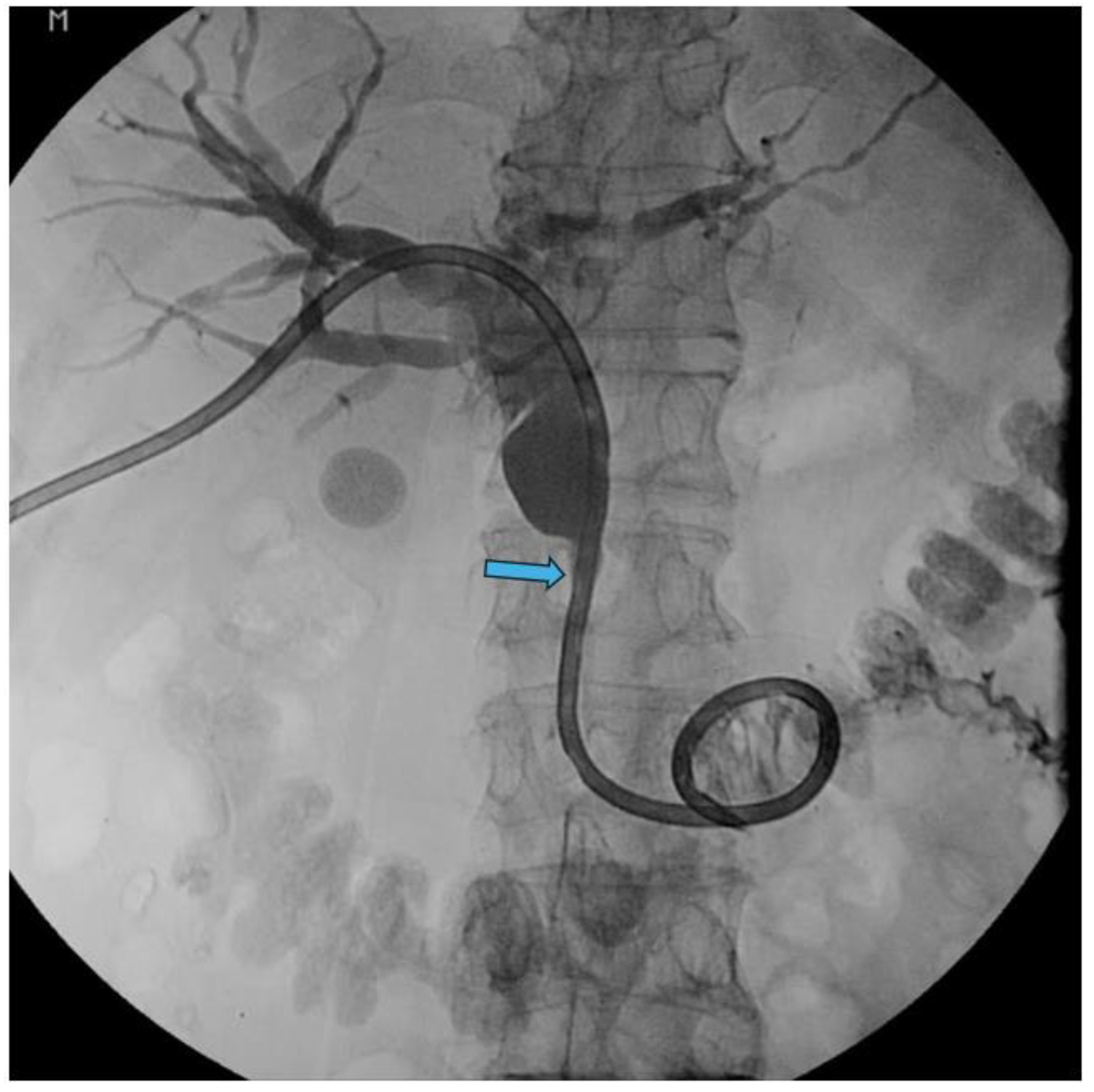

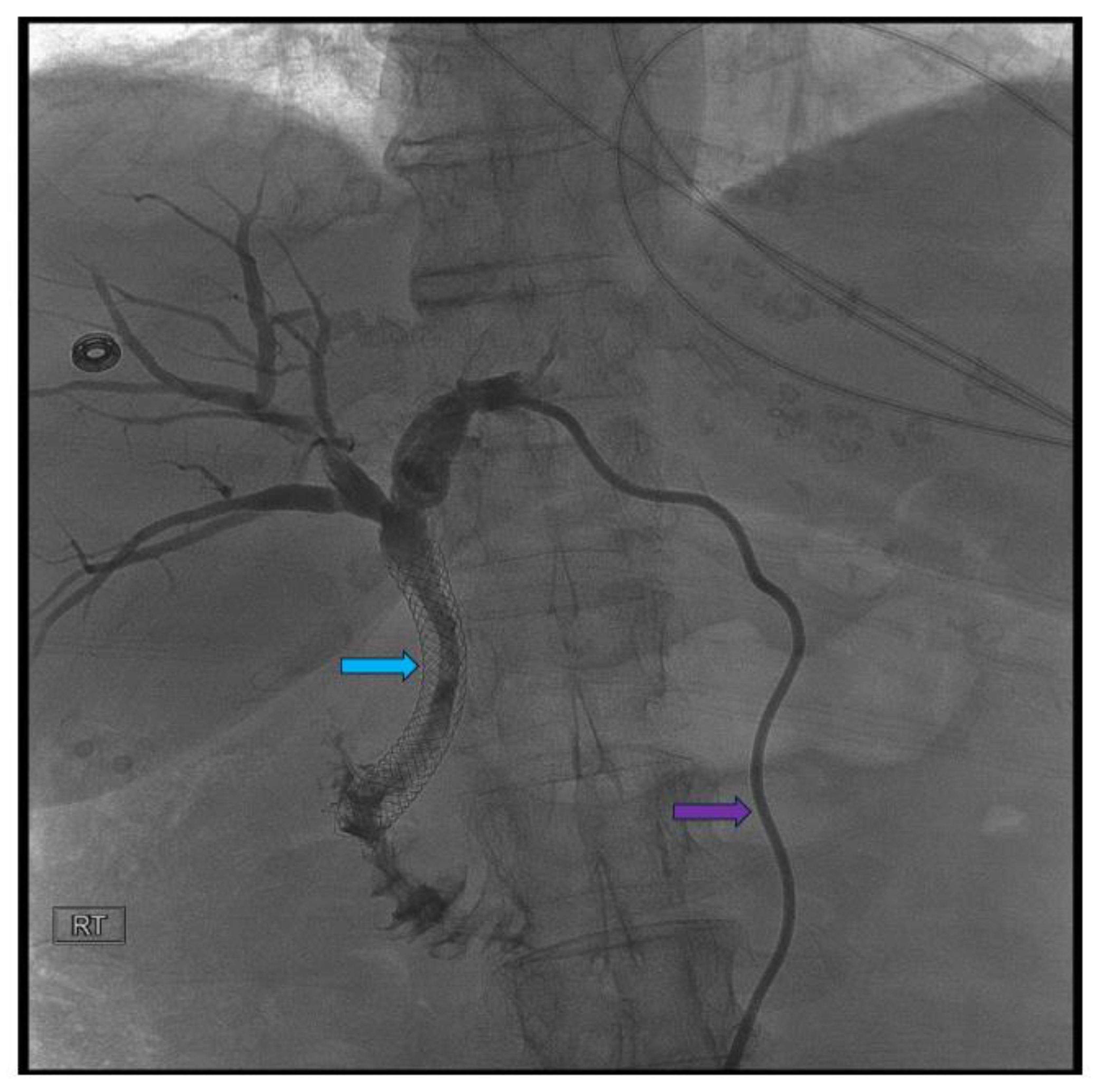

Pancreatic cancer is an aggressive malignancy, and the current 5-year survival rate in the United States, according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data, approximates 12%. Although the current standard for resectable pancreatic cancer most commonly includes neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to a curative resection, surgery in the majority of patients has historically been palliative. The latter interventions include open or laparoscopic bypass of the bile duct or stomach in cases of obstructive jaundice or gastric outlet obstruction, respectively. Non-surgical interventional therapies started with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), both as a palliative maneuver in unresectable patients with obstructive jaundice and to improve liver functions in patients in whom surgery was delayed. Likewise, interventional radiologic techniques included placement of plastic and ultimately self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) through PTBD tracts in patients unresectable for cure as well as percutaneous cholecystostomy in patients who developed cholecystitis in the context of malignant obstructive jaundice. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and stent placement (plastic/SEMS) was subsequently used both preoperatively and palliatively, and this was followed by, or undertaken in conjunction with, endoscopic gastro-duodenal SEMS placement for gastric outlet obstruction. Although endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was initially used to cytologically diagnose and stage pancreatic cancer, early palliation included celiac block or ablation for intractable pain. However, it took the development of lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) to facilitate a myriad of palliative procedures: Cholecystoduodenal, choledochoduodenal, gastrohepatic and gastroenteric anastomoses for cholecystitis, obstructive jaundice, and gastric outlet obstruction, respectively. In this review, we synopse these procedures which have variably supplanted surgery for the palliation of pancreatic cancer in this rapidly evolving field.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Surgical Palliation

Interventional Radiology Palliation

Advanced Endoscopy Palliation

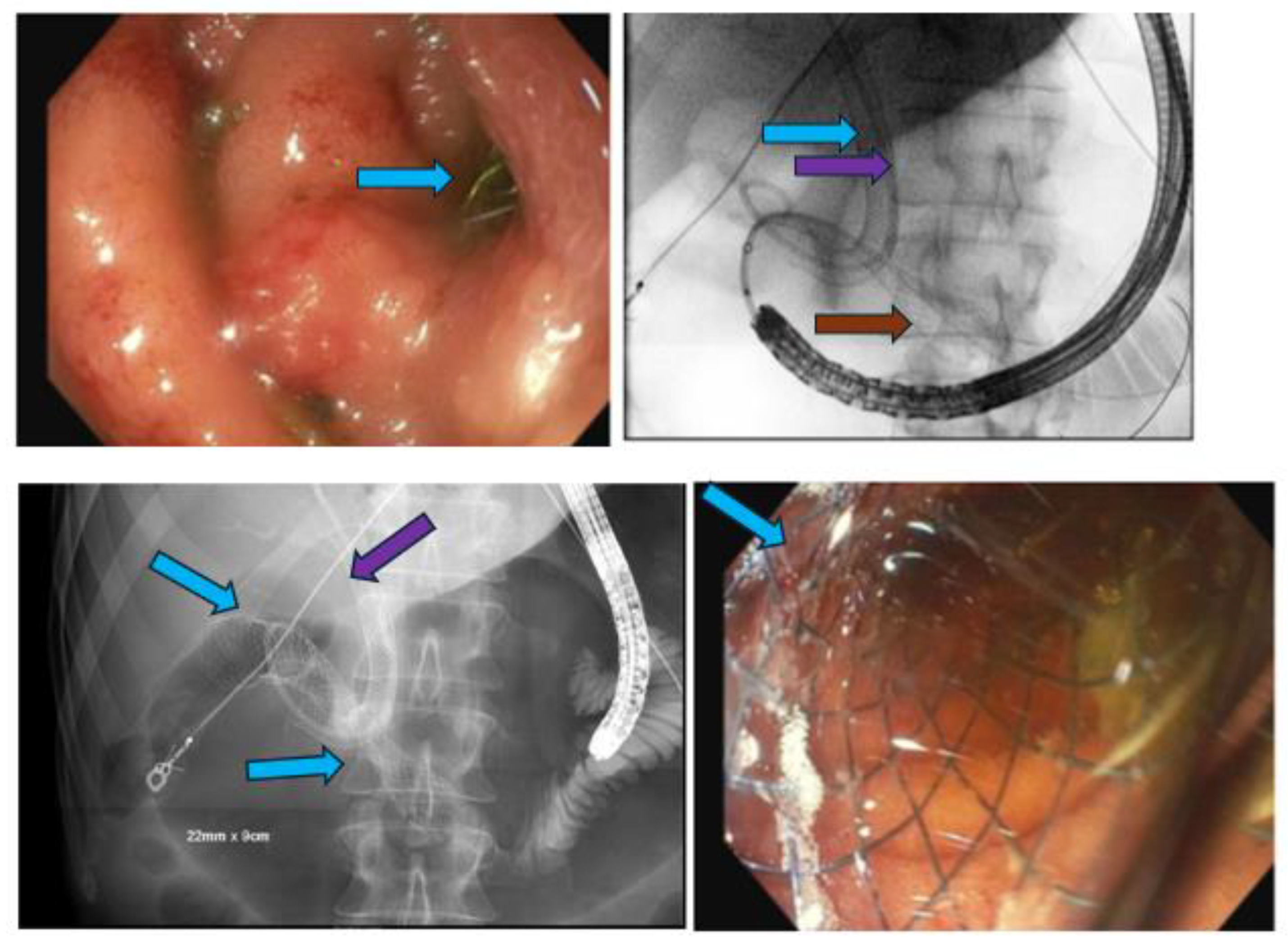

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

Enteral Self-Expandable Metal Stents

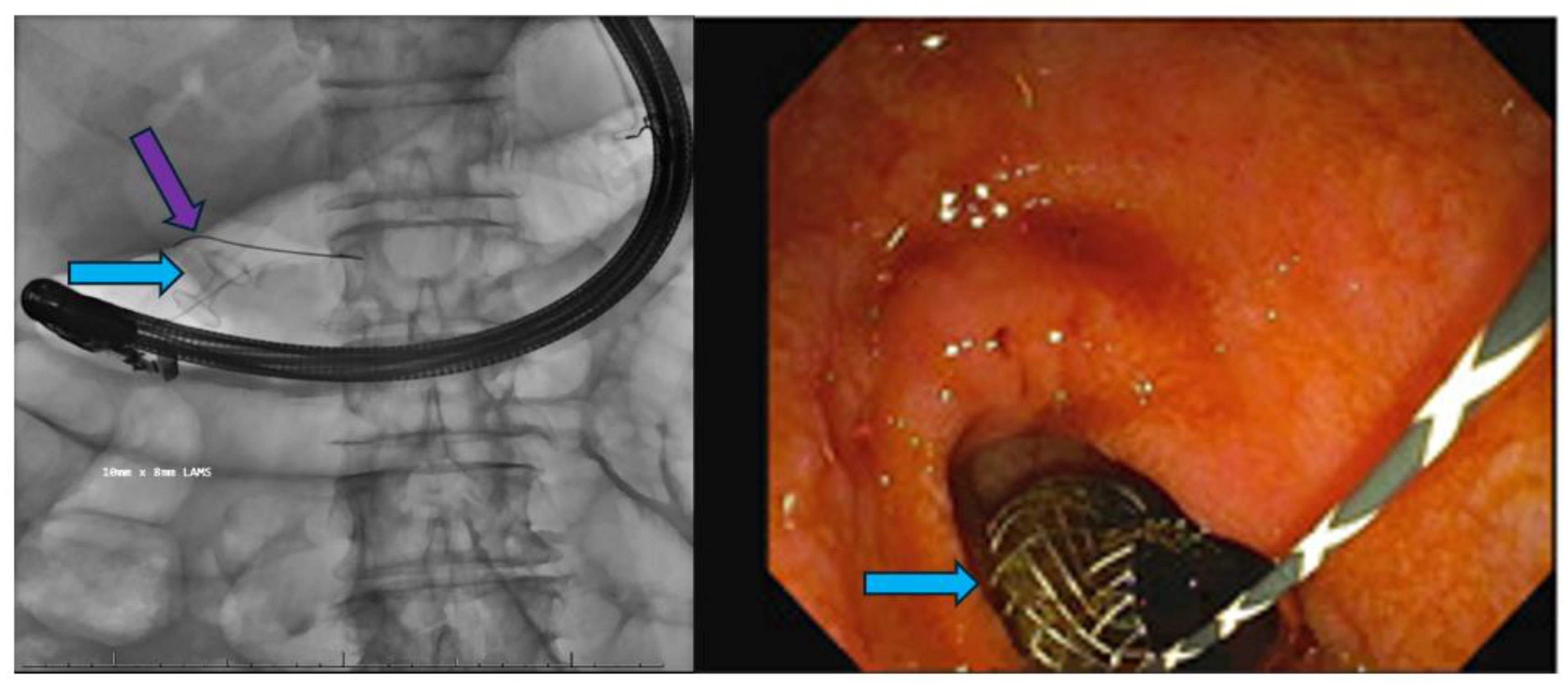

Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Therapies

Lumen-Apposing Metal Stents

EUS-Guided Celiac Plexus Neurolysis

Novel Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Therapies

Conclusions

References

- Lambert A, Schwarz L, Ducreux M, Conroy T. Neoadjuvant Treatment Strategies in Resectable Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(18). [CrossRef]

- Su YY, Chao YJ, Wang CJ, Liao TK, Su PJ, Huang CJ, et al. The experience of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus upfront surgery in resectable pancreatic cancer: a cross sectional study. Int J Surg. 2023;109(9):2614-23. [CrossRef]

- Pencovich N, Orbach L, Lessing Y, Elazar A, Barnes S, Berman P, et al. Palliative bypass surgery for patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: experience from a tertiary center. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2020;18(1):63. [CrossRef]

- Espat NJ, Brennan MF, Conlon KC. Patients with laparoscopically staged unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma do not require subsequent surgical biliary or gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188(6):649-55; discussion 55-7. [CrossRef]

- Lyons JM, Karkar A, Correa-Gallego CC, D'Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, et al. Operative procedures for unresectable pancreatic cancer: does operative bypass decrease requirements for postoperative procedures and in-hospital days? HPB (Oxford). 2012;14(7):469-75.

- Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Hardacre JM, Sohn TA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, et al. Is Prophylactic Gastrojejunostomy Indicated for Unresectable Periampullary Cancer?: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Annals of Surgery. 1999;230(3):322.

- Van Heek NT, De Castro SMM, van Eijck CH, van Geenen RCI, Hesselink EJ, Breslau PJ, et al. The Need for a Prophylactic Gastrojejunostomy for Unresectable Periampullary Cancer: A Prospective Randomized Multicenter Trial With Special Focus on Assessment of Quality of Life. Annals of Surgery. 2003;238(6):894-905. [CrossRef]

- Navarra G, Musolino C, Venneri A, De Marco ML, Bartolotta M. Palliative antecolic isoperistaltic gastrojejunostomy: a randomized controlled trial comparing open and laparoscopic approaches. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(12):1831-4. [CrossRef]

- Guzman EA, Dagis A, Bening L, Pigazzi A. Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy in patients with obstruction of the gastric outlet secondary to advanced malignancies. Am Surg. 2009;75(2):129-32. [CrossRef]

- McGrath PC, McNeill PM, Neifeld JP, Bear HD, Parker GA, Turner MA, et al. Management of biliary obstruction in patients with unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 1989;209(3):284-8. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed O, Lee JH. Preoperative biliary drainage for pancreatic cancer. Int J Gastrointest Interv. 2018;7(2):67-73. [CrossRef]

- Zhang GY, Li WT, Peng WJ, Li GD, He XH, Xu LC. Clinical outcomes and prediction of survival following percutaneous biliary drainage for malignant obstructive jaundice. Oncol Lett. 2014;7(4):1185-90. [CrossRef]

- Rees J, Mytton J, Evison F, Mangat KS, Patel P, Trudgill N. The outcomes of biliary drainage by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography for the palliation of malignant biliary obstruction in England between 2001 and 2014: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e033576. [CrossRef]

- Tavakkoli A, Elmunzer BJ, Waljee AK, Murphy CC, Pruitt SL, Zhu H, et al. Survival analysis among unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients undergoing endoscopic or percutaneous interventions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(1):154-62.e5. [CrossRef]

- Aroori S, Mangan C, Reza L, Gafoor N. Percutaneous Cholecystostomy for Severe Acute Cholecystitis: A Useful Procedure in High-Risk Patients for Surgery. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2019;108(2):124-9. [CrossRef]

- Teoh WM, Cade RJ, Banting SW, Mackay S, Hassen AS. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in the management of acute cholecystitis. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(6):396-8. [CrossRef]

- David S, Celia Robinson L, Angela L, Heather G, Brian B. Use of non-operative treatment and interval cholecystectomy for cholecystitis in patients with cancer. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 2020;5(1):e000439.

- Jariwalla NR, Khan AH, Dua K, Christians KK, Clarke CN, Aldakkak M, et al. Management of Acute Cholecystitis during Neoadjuvant Therapy in Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(13):4515-21. [CrossRef]

- Soehendra N, Reynders-Frederix V. Palliative bile duct drainage - a new endoscopic method of introducing a transpapillary drain. Endoscopy. 1980;12(1):8-11. [CrossRef]

- Boulay BR, Gardner TB, Gordon SR. Occlusion rate and complications of plastic biliary stent placement in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for pancreatic cancer with malignant biliary obstruction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44(6):452-5. [CrossRef]

- Ballard DD, Rahman S, Ginnebaugh B, Khan A, Dua KS. Safety and efficacy of self-expanding metal stents for biliary drainage in patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6(6):E714-e21. [CrossRef]

- Jeong S. Basic Knowledge about Metal Stent Development. Clin Endosc. 2016;49(2):108-12. [CrossRef]

- Zorrón Pu L, de Moura EG, Bernardo WM, Baracat FI, Mendonça EQ, Kondo A, et al. Endoscopic stenting for inoperable malignant biliary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(47):13374-85.

- Walter D, van Boeckel PG, Groenen MJ, Weusten BL, Witteman BJ, Tan G, et al. Cost Efficacy of Metal Stents for Palliation of Extrahepatic Bile Duct Obstruction in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(1):130-8. [CrossRef]

- Seo DW, Sherman S, Dua KS, Slivka A, Roy A, Costamagna G, et al. Covered and uncovered biliary metal stents provide similar relief of biliary obstruction during neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(4):602-12.e4. [CrossRef]

- Tarar ZI, Farooq U, Gandhi M, Saleem S, Daglilar E. Safety of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in cirrhosis compared to non-cirrhosis and effect of Child-Pugh score on post-ERCP complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Endosc. 2023;56(5):578-89. [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan AP, Ekinci F, Yıldırım S, Özveren A, Göksel G. Palliative Biliary Drainage Has No Effect on Survival in Pancreatic Cancer: Medical Oncology Perspective. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(1):52-6. [CrossRef]

- Oh SY, Edwards A, Mandelson M, Ross A, Irani S, Larsen M, et al. Survival and clinical outcome after endoscopic duodenal stent placement for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: comparison of pancreatic cancer and nonpancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(3):460-8.e2. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki R, Sakai Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Nishikawa T, Fujimoto T, Mikami S, et al. Endoscopic management of unresectable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction with a nitinol uncovered metal stent: A prospective Japanese multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(14):3837-44. [CrossRef]

- Fiori E, Lamazza A, Volpino P, Burza A, Paparelli C, Cavallaro G, et al. Palliative management of malignant antro-pyloric strictures. Gastroenterostomy vs. endoscopic stenting. A randomized prospective trial. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(1):269-71.

- Gress FG, Hawes RH, Savides TJ, Ikenberry SO, Cummings O, Kopecky K, et al. Role of EUS in the preoperative staging of pancreatic cancer: a large single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50(6):786-91. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf MN, Chaudhary FS, Ehsan A, Suarez AL, Muniraj T, Jamidar P, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and the management of pancreatic cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Barbosa EC, Santo PAdE, Baraldo S, Nau AL, Meine GC. EUS- versus ERCP-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2024;100(3):395-405.e8. [CrossRef]

- Binmoeller KF, Shah JN. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy using novel tools designed for transluminal therapy: a porcine study. Endoscopy. 2012;44(5):499-503. [CrossRef]

- Anderloni A, Troncone E, Fugazza A, Cappello A, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Monteleone G, Repici A. Lumen-apposing metal stents for malignant biliary obstruction: Is this the ultimate horizon of our experience? World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(29):3857-69.

- Goldman I, Ji K, Scheinfeld MH, Hajifathalian K, Morgan M, Yang J. A stent of strength: use of lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) for biliary pathologies and other novel applications. Abdominal Radiology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rimbaș M, Lau KW, Tripodi G, Rizzatti G, Larghi A. The Role of Luminal Apposing Metal Stents on the Treatment of Malignant and Benign Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(21). [CrossRef]

- Peng ZX, Chen FF, Tang W, Zeng X, Du HJ, Pi RX, et al. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided biliary drainage with placement of electrocautery-enhanced lumen-apposing metal stent for palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: Updated meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;16(3):907-20. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y-I, Sahai A, Donatelli G, Lam E, Forbes N, Mosko J, et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Biliary Drainage of First Intent With a Lumen-Apposing Metal Stent vs Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Malignant Distal Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Study (ELEMENT Trial). Gastroenterology. 2023;165(5):1249-61.e5. [CrossRef]

- Lauri G, Archibugi L, Arcidiacono PG, Repici A, Hassan C, Capurso G, Facciorusso A. Primary drainage of distal malignant biliary obstruction: A comparative network meta-analysis. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fritscher-Ravens A, Mosse CA, Mills TN, Mukherjee D, Park PO, Swain P. A through-the-scope device for suturing and tissue approximation under EUS control. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(5):737-42.

- Fritscher-Ravens A, Mosse CA, Mukherjee D, Mills T, Park PO, Swain CP. Transluminal endosurgery: single lumen access anastomotic device for flexible endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(4):585-91.

- Iqbal U, Khara HS, Hu Y, Kumar V, Tufail K, Confer B, Diehl DL. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy for the management of gastric outlet obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9(1):16-23. [CrossRef]

- Teoh AYB, Lakhtakia S, Tarantino I, Perez-Miranda M, Kunda R, Maluf-Filho F, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gastroenterostomy versus uncovered duodenal metal stenting for unresectable malignant gastric outlet obstruction (DRA-GOO): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9(2):124-32. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthi R, Bomman S, Benias P, Kozarek RA, Peetermans JA, McMullen E, et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic duodenal stent versus endoscopic or surgical gastrojejunostomy to treat malignant gastric outlet obstruction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2022;10(6):E874-e97. [CrossRef]

- van der Merwe SW, van Wanrooij RLJ, Bronswijk M, Everett S, Lakhtakia S, Rimbas M, et al. Therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022;54(2):185-205. [CrossRef]

- Irani SS, Sharma NR, Storm AC, Shah RJ, Chahal P, Willingham FF, et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Transluminal Gallbladder Drainage in Patients With Acute Cholecystitis: A Prospective Multicenter Trial. Ann Surg. 2023;278(3):e556-e62.

- Chon HK, Lee YC, Kim TH, Lee SO, Kim S-H. Revolutionizing outcomes: endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage using innovative electrocautery enhanced-lumen apposing metal stents for high-risk surgical patients. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):12893. [CrossRef]

- Kozakai F, Kanno Y, Ito K, Koshita S, Ogawa T, Kusunose H, et al. Endoscopic Ultrasonography-Guided Gallbladder Drainage as a Treatment Option for Acute Cholecystitis after Metal Stent Placement in Malignant Biliary Strictures. Clin Endosc. 2019;52(3):262-8. [CrossRef]

- Binda C, Anderloni A, Forti E, Fusaroli P, Macchiarelli R, Manno M, et al. EUS-Guided Gallbladder Drainage Using a Lumen-Apposing Metal Stent for Acute Cholecystitis: Results of a Nationwide Study with Long-Term Follow-Up. Diagnostics. 2024;14(4):413. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Aguado G, de la Mata DM, Valenciano CM, Sainz IF. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided celiac plexus neurolysis in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: An update. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;13(10):460-72. [CrossRef]

- Thosani N, Cen P, Rowe J, Guha S, Bailey-Lundberg JM, Bhakta D, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation (EUS-RFA) for advanced pancreatic and periampullary adenocarcinoma. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):16516. [CrossRef]

- Gollapudi LA, Tyberg A. EUS-RFA of the pancreas: where are we and future directions. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:18.

- Karaisz FG, Elkelany OO, Davies B, Lozanski G, Krishna SG. A Review on Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Radiofrequency Ablation (EUS-RFA) of Pancreatic Lesions. Diagnostics. 2023;13(3):536. [CrossRef]

- Coronel E, Singh BS, Cazacu IM, Moningi S, Romero L, Taniguchi C, et al. EUS-guided placement of fiducial markers for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. VideoGIE. 2019;4(9):403-6. [CrossRef]

- Cazacu IM, Singh BS, Martin-Paulpeter RM, Beddar S, Chun S, Holliday EB, et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fiducial Placement for Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(22). [CrossRef]

- Carrara S, Rimbas M, Larghi A, Di Leo M, Comito T, Jaoude JA, et al. EUS-guided placement of fiducial markers for image-guided radiotherapy in gastrointestinal tumors: A critical appraisal. Endoscopic Ultrasound. 2021;10(6):414-23. [CrossRef]

- Kerdsirichairat T, Shin EJ. Endoscopic ultrasound guided interventions in the management of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;14(4):191-204. [CrossRef]

- Sun S, Xu H, Xin J, Liu J, Guo Q, Li S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided interstitial brachytherapy of unresectable pancreatic cancer: results of a pilot trial. Endoscopy. 2006;38(4):399-403. [CrossRef]

- Sun S, Ge N, Wang S, Liu X, Wang G, Guo J. Pilot trial of endoscopic ultrasound-guided interstitial chemoradiation of UICC-T4 pancreatic cancer. Endosc Ultrasound. 2012;1(1):41-7. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhang T, Cai F, Tang P, et al. The role of seed implantation in patients with unresectable pancreatic carcinoma after relief of obstructive jaundice using ERCP. Brachytherapy. 2020;19(1):97-103. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).