Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fabrication of Biomass-Derived Carbons

2.3. Characterization of Biomass-Derived Carbons

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

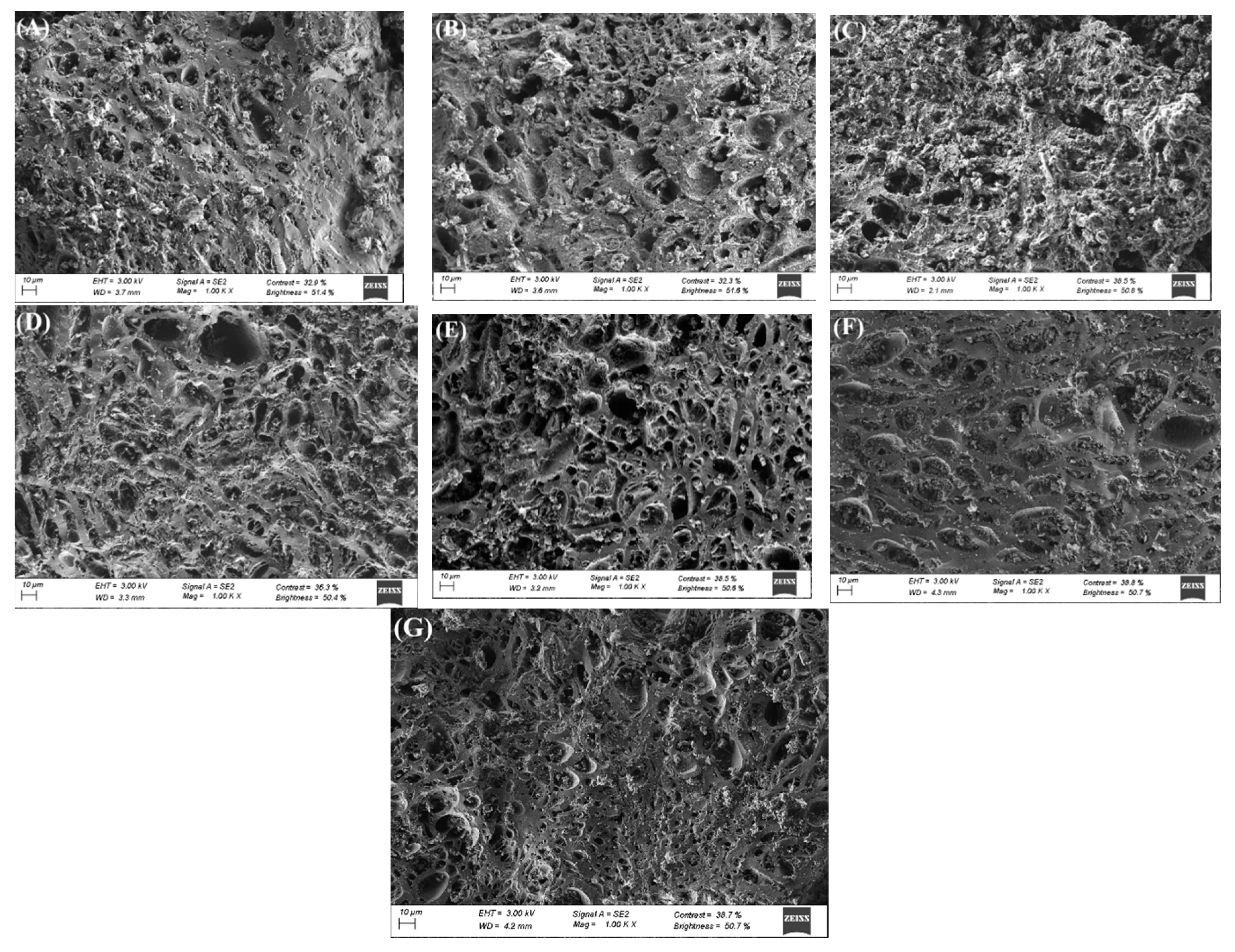

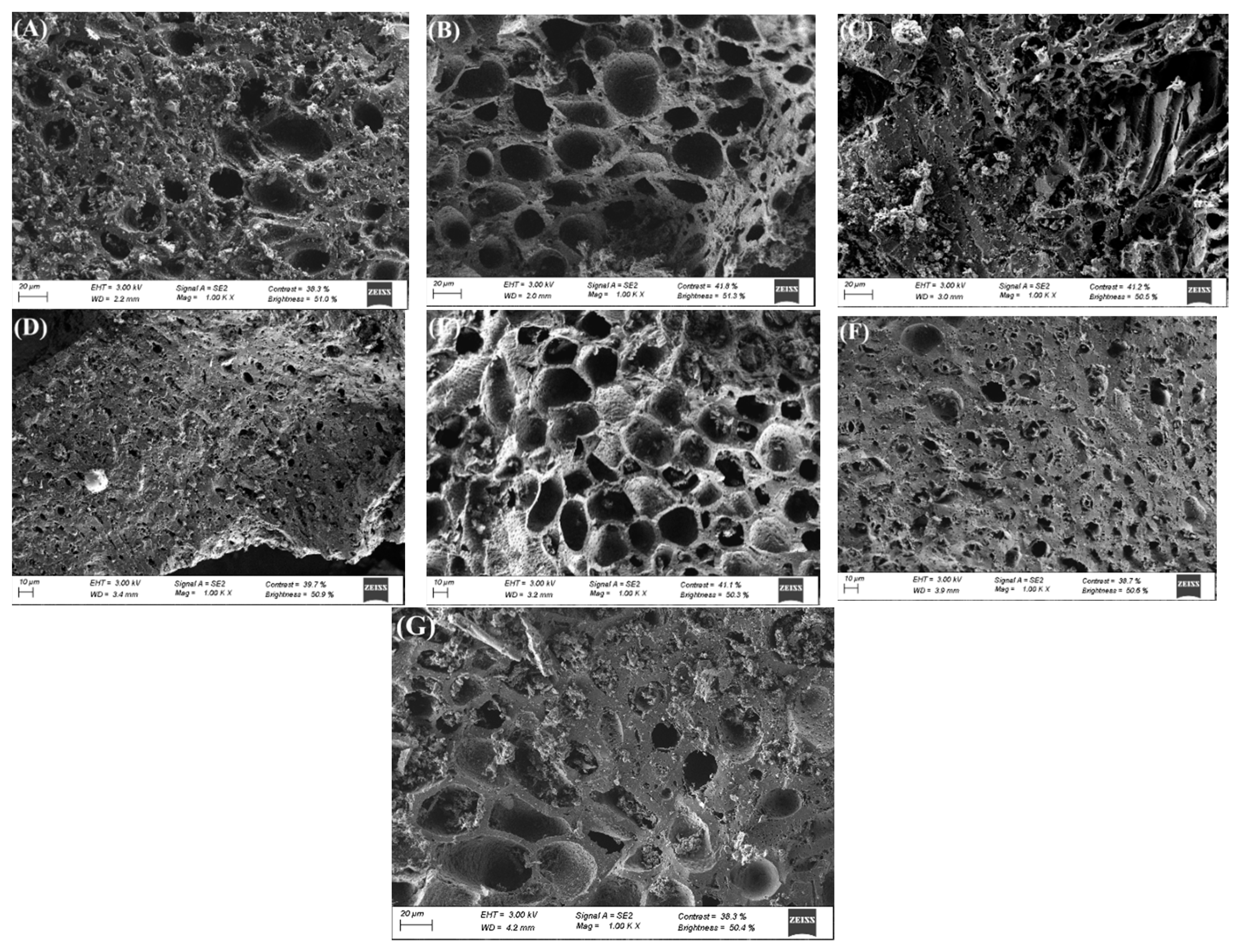

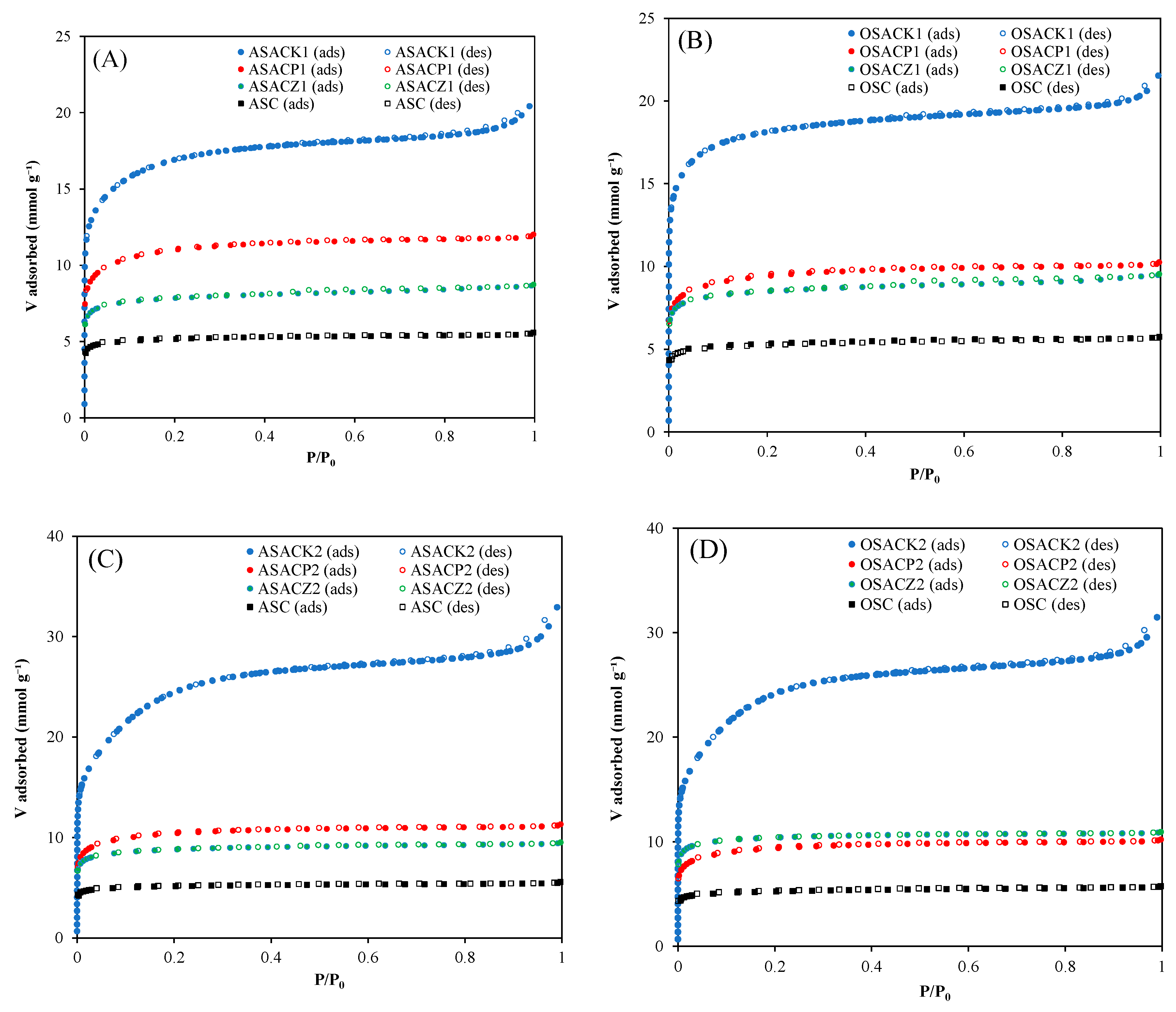

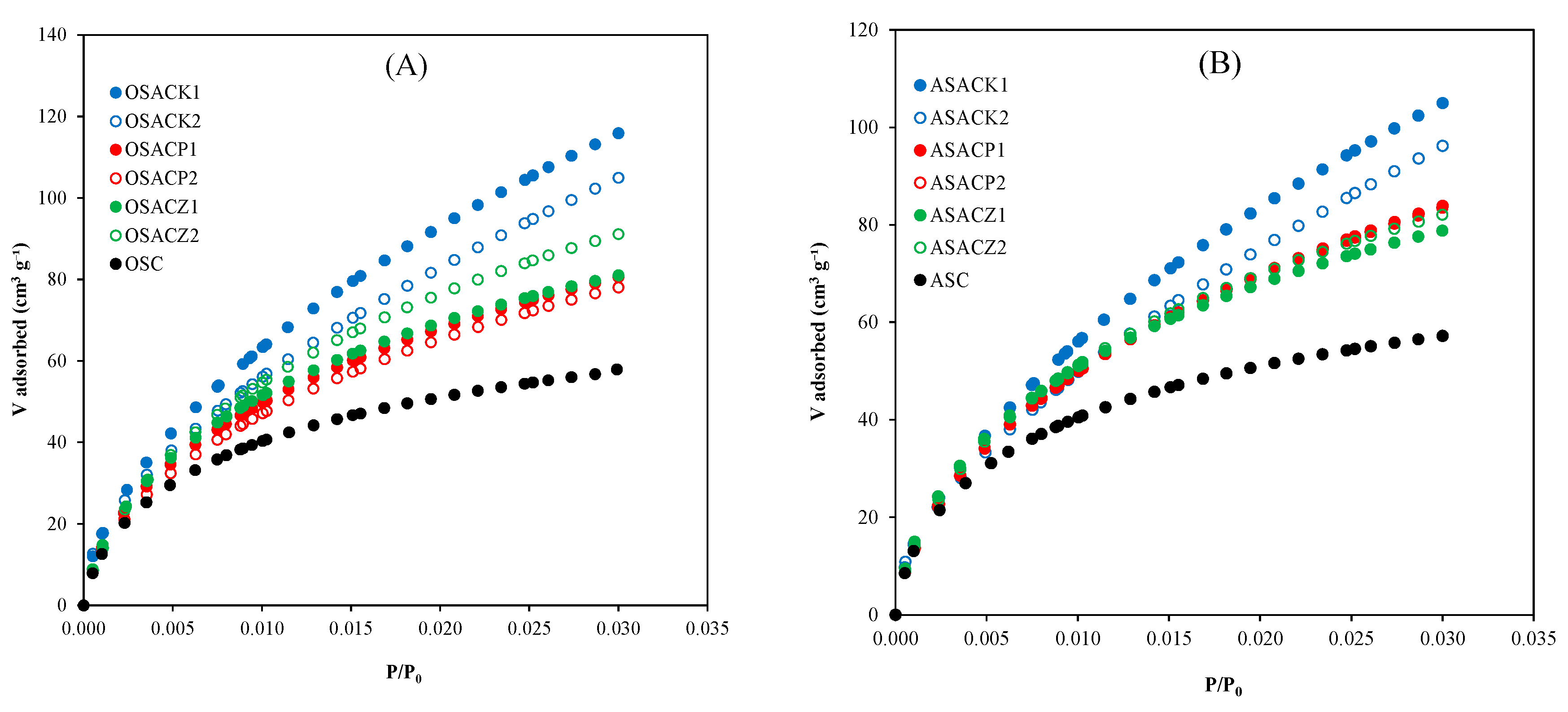

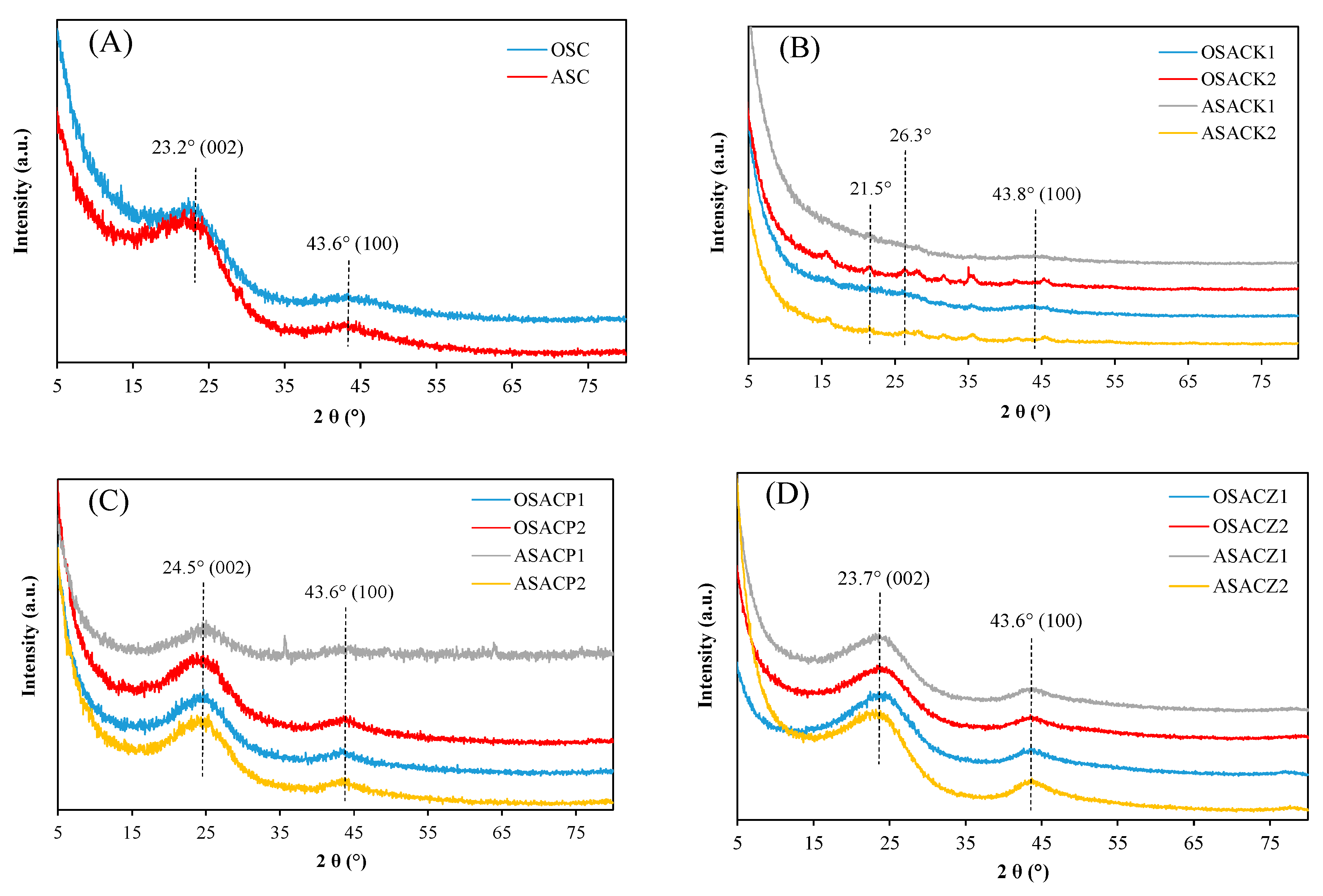

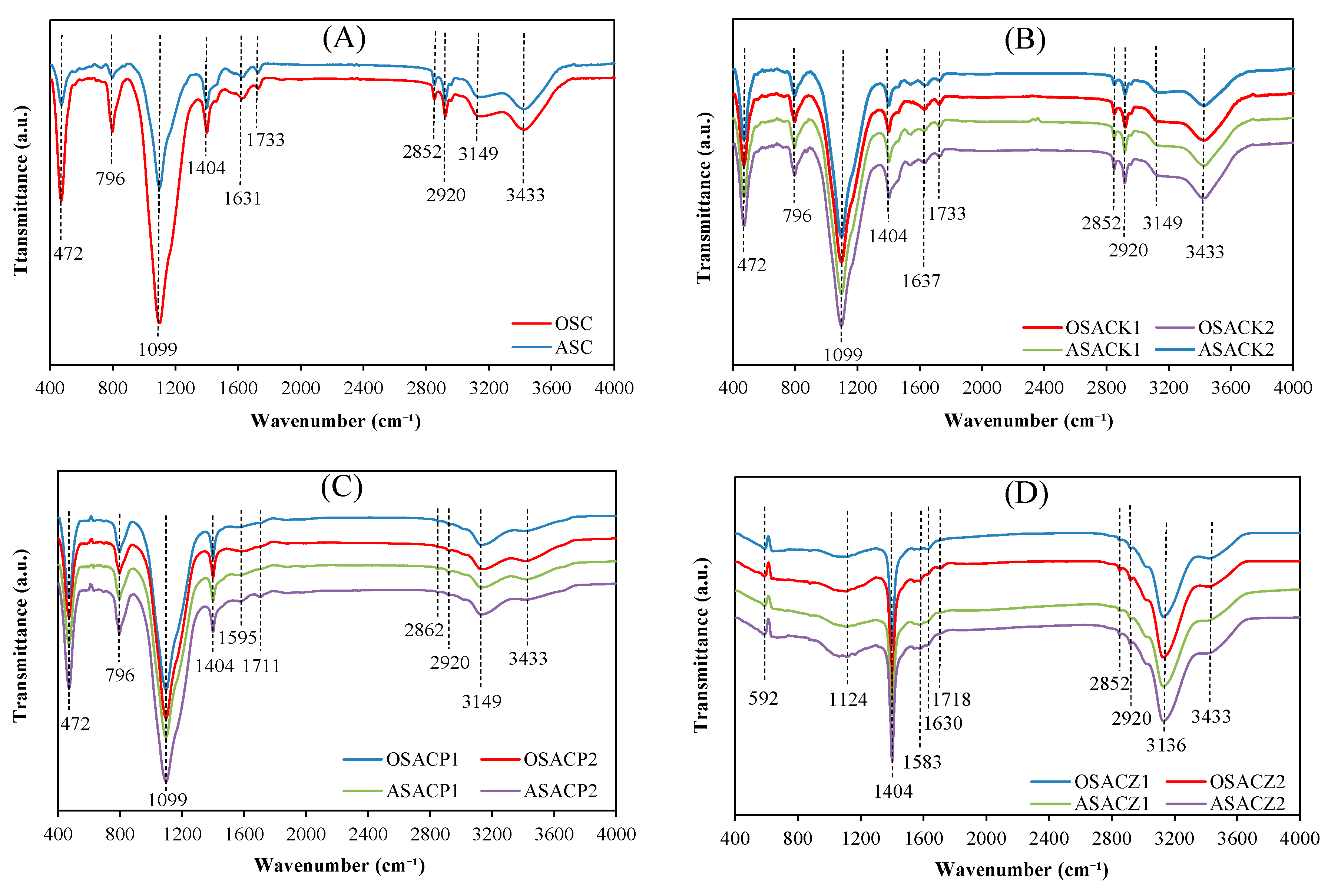

3.1. Carbon Characterization

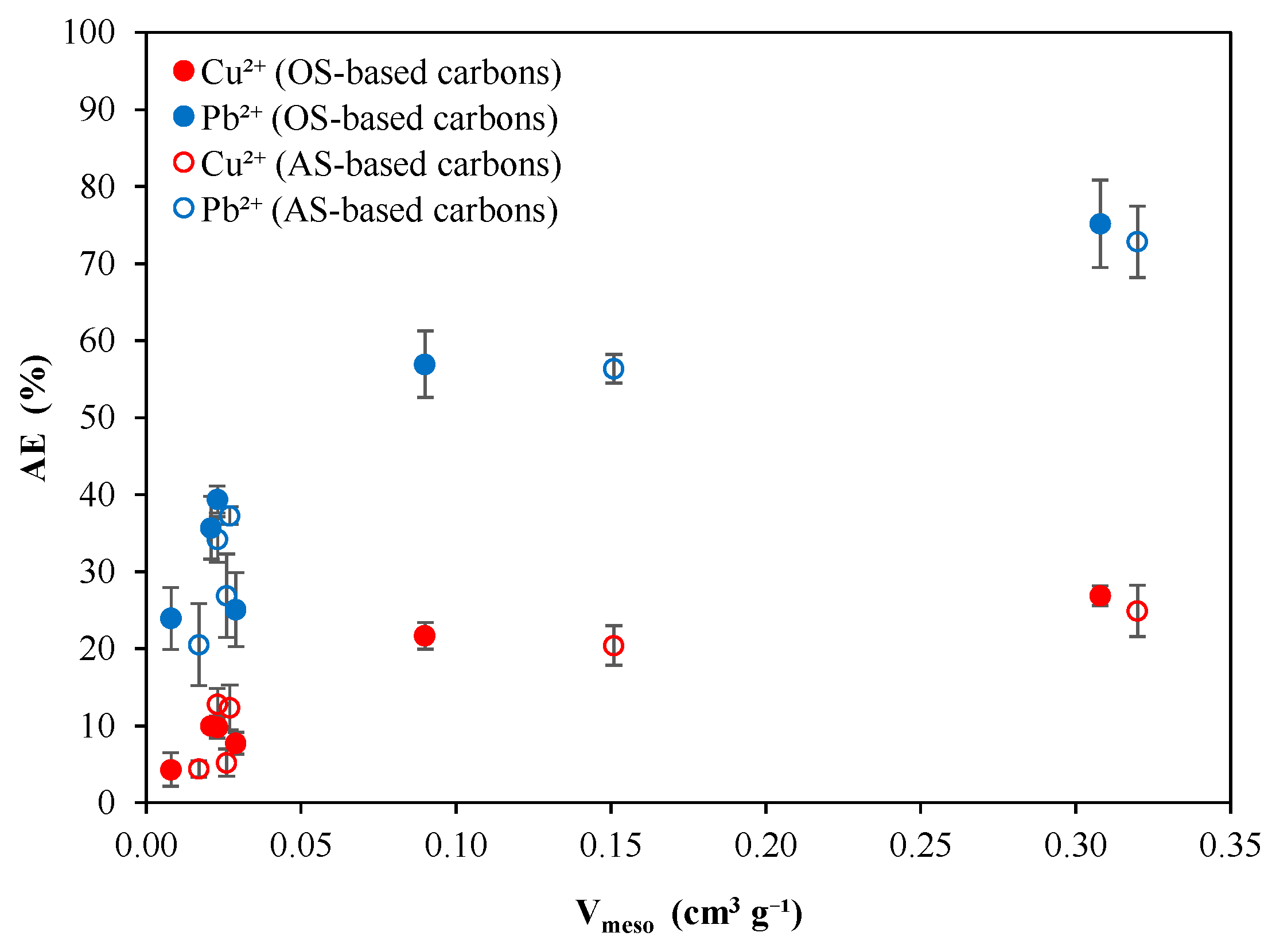

3.2. Cu2+ Adsorption Performance of Biomass-Derived Carbons

3.3. Pb2+ Adsorption Performance of Biomass-Derived Carbons

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gutwiński, P.; Cema, G.; Ziembińska-Buczyńska, A.; Wyszyńska, K.; Surmacz-Górska, J. Long-term effect of heavy metals Cr(III), Zn(II), Cd(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), Pb(II) on the anammox process performance. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 39, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, H.; Güngör, C. Adsorption of copper(II) from aqueous solutions on activated carbon prepared from grape bagasse. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisan, R.S.; Saady, N.M.C.; Bazan, C.; Zendehboudi, S.; Albayati, T.M. Adsorption of copper from water using TiO2-modified activated carbon derived from orange peels and date seeds: Response surface methodology optimization. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Beeregowda, K.N. et al., Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals, Interdiscip Toxicol. 2014, 7, 60–72. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, P.; Gao, P.; Barford, J.P.; Mckay, G. Novel application of the nonmetallic fraction of the recycled printed circuit boards as a toxic heavy metal adsorbent. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 252–253, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, B.; Pan, D.; Wu, Y.; Zuo, T. Recovery of waste printed circuit boards through pyrometallurgical processing: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Lin, C.S.K.; Hui, D.C.W.; McKay, G. Waste printed circuit board (PCB) recycling techniques. Top. Curr. Chem. 2017, 375, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, V.; Inzulza-Moraga, E.A.; Gómez-Díaz, D.; Freire, M.S.; González-Álvarez, J. Screening of variables affecting the selective leaching of valuable metals from waste motherboards’ PCBs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, R.; Nekouei, R.K.; Mansuri, I.; Sahajwalla, V. Sustainable recovery of Cu and Sn from problematic global waste: Exploring value from waste printed circuit boards. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.D.; Singh, K.K.; Morrison, C.A.; Love, J.B. Optimization of process parameters for the selective leaching of copper, nickel and isolation of gold from obsolete mobile phone PCBs. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Priya, A.K.; Kumar, P.S.; Hoang, T.K.A.; Sekar, K.; Chong, K.Y.; et al. A critical and recent developments on adsorption technique for removal of heavy metals from wastewater-A review. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yue, X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, F. Amino modification of rice straw-derived biochar for enhancing its cadmium (II) ions adsorption from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 379, 120783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Weiying, L.; Wanqi, Q.; Sheng, C.; Qiaowen, T.; Zhongqing, W.; et al. The comprehensive evaluation model and optimization selection of activated carbon in the O3-BAC treatment process. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 40, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawtali, S.; El-Harbawi, M.; El Blidi, L.; Alrashed, M.M.; Alzobidi, A.; Yin, C.-Y. Date Palm Leaflet-Derived Carbon Microspheres Activated Using Phosphoric Acid for Efficient Lead (II) Adsorption. C-J. Carbon Res. 2024, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, S.N.H.; Al-Balushi, M.; Al-Siyabi, F.; Al-Hinai, N.; Khurshid, S. Adsorptive removal of Pb(II) ions from groundwater samples in Oman using carbonized Phoenix dactylifera seed (Date stone). J. King. Saud. Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 2931–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, L.; Xu, Q.; Tian, W.; Li, Z.; Kobayashi, N. Adsorption kinetics and mechanisms of copper ions on activated carbons derived from pinewood sawdust by fast H3PO4 activation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 7907–7915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teğin, İ.; Öc, S.; Saka, C. Adsorption of copper (II) from aqueous solutions using adsorbent obtained with sodium hydroxide activation of biochar prepared by microwave pyrolysis. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Kumar, S.; Lichtfouse, E.; Cheng, C.K.; Varma, A.S.; Senthilkumar, N.; et al. Remediation of heavy metal polluted waters using activated carbon from lignocellulosic biomass: An update of recent trends. Chemosphere 2022, 302, 134825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Asim, M.; Khan, T.A. Low cost adsorbents for the removal of organic pollutants from wastewater. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 113, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, P.; Centeno, T.A.; Urones-Garrote, E.; Ávila-Brande, D.; Otero-Díaz, L.C. Microstructure and surface properties of lignocellulosic-based activated carbons. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 265, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariana, M.; Khalil, A.; Mistar, E.M.; Yahya, E.B.; Alfatah, T.; Danish, M.; Amayreh, M. Recent advances in activated carbon modification techniques for enhanced heavy metal adsorption. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 43, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Mayoral, E.; Matos, I.; Bernardo, M.; Fonseca, I.M. New and advanced porous carbon materials in fine chemical synthesis. Emerging precursors of porous carbons. Catalysts 2019, 9, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Jin, B.; Xiao, R.; Yang, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; et al. The comparison of two activation techniques to prepare activated carbon from corn cob. Catalysts 2013, 48, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, M.R.; Yusof, N.A.; Haron, M.J.; Ibrahim, N.; Mohammad, F.; Kamaruzaman, S.; et al. Iminodiacetic acid modified kenaf fiber for waste water treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Wang, Q.; Li, R.; Lucia, L.A. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from hydrochar by phosphoric acid activation and its adsorption performance in prehydrolysis liquor. Bioresources 2017, 12, 5928–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Ali, M.; Khoja, A.H.; Nawar, A.; Waqas, A.; Liaquat, R.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of biomass-derived surface-modified activated carbon for enhanced CO2 adsorption. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 46, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakout, S.M.; El-Deen, G.S. Characterization of activated carbon prepared by phosphoric acid activation of olive stones. Arab. J. Chem. 2016, 9, S1155–S1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomiak, K.; Gryglewicz, S.; Kierzek, K.; Machnikowski, J. Optimizing the properties of granular walnut-shell based KOH activated carbons for carbon dioxide adsorption. J CO2 Util. 2017, 21, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, P.; Kots, P.A.; Cohen, M.; Chen, Y.; Quinn, C.M.; et al. Tuning the reactivity of carbon surfaces with oxygen-containing functional groups. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Narkiewicz, U.; Morawski, A.W.; Wróbel, R.J.; Michalkiewicz, B. Highly microporous activated carbons from biomass for CO2 capture and effective micropores at different conditions. J. CO2. Util. 2017, 18, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Peng, W.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; et al. Preparation of biomass-derived porous carbons by a facile method and application to CO2 adsorption. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 116, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, C.; Liu, H.; Xue, Q.; et al. Potassium and zeolitic structure modified ultra-microporous adsorbent materials from a renewable feedstock with favorable surface chemistry for CO2 capture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 32, 26826–26839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, F.; Iqbal, S.Z.; Albazzaz, S.; Ali, U.; Mortari, D.A.; Rashid, T. Development of biomass derived highly porous fast adsorbents for post-combustion CO2 capture. Fuel 2020, 282, 118506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhao, N.; Lei, S.; Yan, R.; Tian, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Promising biomass-based activated carbons derived from willow catkins for high performance supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 166, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccirillo, C.; Moreira, I.S.; Novais, R.M.; Fernandes, A.J.S.; Pullar, R.C.; Castro, P.M.L. Biphasic apatite-carbon materials derived from pyrolysed fish bones for effective adsorption of persistent pollutants and heavy metals. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4884–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vol, S.; Ban, I.; Derofenik, M.; Buksek, H.; Gyergyek, S.; Petrinic, I.; et al. Microwave synthesis of poly(acrylic) acid-coated magnetic nanoparticles as draw solutes in forward osmosis. Materials 2023, 16, 4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, G.P.; Li, W.C.; Qian, D.; Lu, A.H. Rapid synthesis of nitrogen-doped porous carbon monolith for CO2 capture. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daffalla, S.B.; Mukhtar, H.; Shaharun, M.S. Properties of activated carbon prepared from rice husk with chemical activation. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2012, 12, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, T.H.; Wu, S.J. Characteristics of microporous/mesoporous carbons prepared from rice husk under base- and acid-treated conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 171, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhong, H.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Tang, P.; Li, D.; et al. Porous ZnCl2-activated carbon from shaddock peel: Methylene blue adsorption behavior. Materials 2022, 15, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xia, X.; Li, K.; Shen, Y.; Xue, Y. New insights into temperature-induced mechanisms of copper adsorption enhancement on hydroxyapatite-in situ self-doped fluffy bread-like biochar. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.G.; Habila, M.A.; ALOthman, Z.A.; Badjah-Hadj-Ahmed, A.Y. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticle anchored carbon as hybrid adsorbent materials for effective heavy metals uptake from wastewater. Crystals 2024, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-S.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lee, C.H. Modified activated carbon for copper ion removal from aqueous solution. Processes 2022, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Degs, Y.S.; El-Barghouthi, M.I.; El-Sheikh, A.H.; Walker, G.M. Effect of solution pH, ionic strength, and temperature on adsorption behavior of reactive dyes on activated carbon. Dyes Pigm. 2008, 77, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Qian, Q.; Machida, M.; Tatsumoto, H. Effect of ZnO loading to activated carbon on Pb (II) adsorption from aqueous solution. Carbon 2006, 44, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, V.; Ferreiro-Salgado, A.; Gómez-Díaz, D.; Freire, M.S.; González-Álvarez, J. Evaluating the performance of carbon-based adsorbents fabricated from renewable biomass precursors for post-combustion CO2 capture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 344, 127110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siipola, V.; Tamminen, T.; Källi, A.; Lahti, R.; Romar, H.; Rasa, K., et al. Effects of biomass type, carbonization process, and activation method on the properties of bio-based activated carbons. Biores 2018, 13, 5976–6002. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, G. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon fibers from liquefied wood by ZnCl2 activation. Biores 2016, 11, 3178–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Kim, I.Y.; Lakhi, K.S.; Srivastava, P.; Naidu, R.; Vinu, A. Single step synthesis of activated bio-carbons with a high surface area and their excellent CO2 adsorption capacity. Carbon 2017, 116, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukayat, O.O.; Usman, M.F.; Elizabeth, O.M.; Abosede, O.O.; Faith, I.U. Kinetic adsorption of heavy metal (copper) on rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) leaf powder. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 37, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darweesh, M.A.; Elgendy, M.Y.; Ayad, M.I.; Ahmed, A.M.; Elsayed, N.M.K.; Hammad, W.A. Adsorption isotherm, kinetic, and optimization studies for copper (II) removal from aqueous solutions by banana leaves and derived activated carbon. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 40, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, B.S.; Alaya, M.N.; Sherif, I.E.; Fathy, N.A. Development of porosity and copper (II) ion adsorption capacity by activated nano-carbon xerogels in relation to treatment schemes. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2011, 29, 943–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Long, A.; Chen, M.; Xiao, X.; et al. Adsorption-desorption of copper (II) by temperature-sensitive nano-biochar@PNIPAM/alginate double-network composite hydrogel: Enhanced mechanisms and application potentials. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlatshahi, S.; Torbati, A.R.H.; Loloei, M. Adsorption of copper, lead and cadmium from aqueous solutions by activated carbon prepared from saffron leaves. Environ. Health Eng. Manag. J. 2014, 1, 37–44, http://ehemj.com/article-1-43-en.html. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X-Y; Wu, Y-W.; Cai, Q.; Mi, T-G.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, L.; et al. Interaction mechanism between lead species and activated carbon in MSW incineration flue gas: Role of different functional groups. Chem. Eng J. 2022, 436, 135252. [CrossRef]

| Precursor | Carbon | Activating Agent | C/A Ratio (w/w) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olive Stones | OSC | Non-activated | - |

| OSACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | |

| OSACK2 | 1:4 | ||

| OSACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | |

| OSACP2 | 1:4 | ||

| OSACZ1 | ZnCl2 | 1:2 | |

| OSACZ2 | 1:4 | ||

| Almond Shells | ASC | Non-activated | - |

| ASACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | |

| ASACK2 | 1:4 | ||

| ASACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | |

| ASACP2 | 1:4 | ||

| ASACZ1 | ZnCl2 | 1:2 | |

| ASACZ2 | 1:4 |

| Carbon | % C | % O | % K | % Ca | % Al | % P | % Cl | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSC | 90.80 | 8.74 | 0.16 | 0.31 | - | - | - | - |

| OSACK1 | 66.67 | 26.44 | 2.96 | 0.47 | 3.47 | - | - | - |

| OSACK2 | 53.79 | 35.11 | 3.86 | 0.24 | 7.01 | - | - | - |

| OSACP1 | 84.29 | 14.51 | - | 0.08 | - | 1.12 | - | - |

| OSACP2 | 83.45 | 14.99 | - | 0.15 | - | 1.42 | - | - |

| OSACZ1 | 89.94 | 9.71 | - | - | 0.05 | - | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| OSACZ2 | 88.90 | 10.69 | - | - | 0.09 | - | 0.11 | 0.20 |

| ASC | 87.80 | 10.65 | 0.87 | 0.67 | - | - | - | - |

| ASACK1 | 72.03 | 23.52 | 1.60 | 0.40 | 2.36 | - | - | - |

| ASACK2 | 75.65 | 19.37 | 3.44 | 0.39 | 1.16 | - | - | - |

| ASACP1 | 82.80 | 16.73 | - | 0.15 | - | 0.32 | - | - |

| ASACP2 | 83.87 | 15.39 | - | 0.05 | - | 0.70 | - | - |

| ASACZ1 | 82.83 | 14.92 | - | 0.20 | 0.18 | - | 1.36 | 0.46 |

| ASACZ2 | 86.48 | 11.89 | - | 0.07 | 0.13 | - | 1.09 | 0.27 |

| P/P0 = 0.99 | DFT | 2DNLDFT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | SBET (N2) )m2 g-1) |

SBET (CO2) (m2 g-1) |

Vtotal (cm3 g-1) |

Dp (nm) |

Vtotal (cm3 g-1) |

Vmicro (cm3 g-1) |

Vmeso (cm3 g-1) |

micro Φ (%) |

| OSC | 427.5 | 294.8 | 0.197 | 1.84 | 0.183 | 0.171 | 0.012 | 93.4 |

| OSACK1 | 1443.5 | 760.8 | 0.747 | 5.34 | 0.676 | 0.575 | 0.090 | 85.1 |

| OSACK2 | 1955.3 | 672.8 | 1.091 | 4.72 | 1.024 | 0.695 | 0.308 | 67.9 |

| OSACP1 | 714.9 | 464.2 | 0.352 | 2.53 | 0.323 | 0.302 | 0.021 | 93.5 |

| OSACP2 | 711.8 | 458.0 | 0.351 | 2.53 | 0.322 | 0.299 | 0.023 | 92.9 |

| OSACZ1 | 712.0 | 459.2 | 0.328 | 2.87 | 0.304 | 0.275 | 0.029 | 90.5 |

| OSACZ2 | 849.5 | 546.0 | 0.377 | 2.31 | 0.348 | 0.340 | 0.008 | 97.7 |

| ASC | 405.3 | 298.2 | 0.190 | 2.73 | 0.177 | 0.170 | 0.007 | 96.0 |

| ASACK1 | 1350.1 | 713.6 | 0.733 | 5.04 | 0.729 | 0.578 | 0.151 | 79.3 |

| ASACK2 | 1979.4 | 662.4 | 1.142 | 4.59 | 1.033 | 0.686 | 0.320 | 66.4 |

| ASACP1 | 833.1 | 500.3 | 0.412 | 2.36 | 0.377 | 0.350 | 0.027 | 92.8 |

| ASACP2 | 791.2 | 496.5 | 0.388 | 2.48 | 0.355 | 0.332 | 0.023 | 93.5 |

| ASACZ1 | 635.5 | 441.1 | 0.300 | 2.80 | 0.278 | 0.252 | 0.026 | 90.6 |

| ASACZ2 | 719.6 | 473.0 | 0.327 | 2.25 | 0.302 | 0.285 | 0.017 | 94.4 |

| Carbon | pHpzc |

|---|---|

| OSC | 7.3 |

| OSACK1 | 8.1 |

| OSACK2 | 8.4 |

| OSACP1 | 3.5 |

| OSACP2 | 2.9 |

| OSACZ1 | 6.1 |

| OSACZ2 | 5.5 |

| ASC | 7.7 |

| ASACK1 | 8.0 |

| ASACK2 | 8.4 |

| ASACP1 | 3.4 |

| ASACP2 | 3.4 |

| ASACZ1 | 6.2 |

| ASACZ2 | 5.9 |

| Carbon | % C | % H | % N | % O* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSC | 83.36 | 2.00 | 0.24 | 14.40 |

| OSAC1 | 66.44 | 1.30 | 0.24 | 32.02 |

| OSAC2 | 55.02 | 1.16 | 0.18 | 43.64 |

| OSACP1 | 74.18 | 1.90 | 0.38 | 23.54 |

| OSACP2 | 70.66 | 1.79 | 0.35 | 27.20 |

| OSACZ1 | 80.70 | 1.20 | 0.69 | 17.41 |

| OSACZ2 | 81.70 | 1.67 | 0.22 | 16.41 |

| ASC | 83.14 | 2.02 | 0.30 | 14.54 |

| ASAC1 | 66.48 | 1.09 | 0.20 | 32.23 |

| ASAC2 | 56.72 | 1.42 | 0.11 | 41.75 |

| ASACP1 | 70.60 | 2.02 | 0.53 | 26.85 |

| ASACP2 | 73.38 | 2.08 | 0.43 | 24.11 |

| ASACZ1 | 82.12 | 1.40 | 0.91 | 15.57 |

| ASACZ2 | 80.65 | 1.72 | 0.60 | 17.03 |

| Ci=100 mg L-1 – AD=2 g L-1 | Ci=100 mg L-1 – AD=5 g L-1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | Activating Agent | C/A Ratio (w/w) | AE, % | qe, mg g-1 | AE, % | qe, mg g-1 | |||

| OSC | - | - | 29.92±1.15bc | 14.75±0.68bc | 33.44±2.16b | 7.21±0.33b | |||

| OSACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | 71.66±3.59e | 35.33±2.16e | 98.74±0.78f | 21.33±0.41f | |||

| OSACK2 | 1:4 | 86.29±2.73f | 42.52±1.42f | 99.86±0.13f | 21.58±0.60f | ||||

| OSACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | 36.29±2.15cd | 17.87±1.33cd | 44.27±0.73c | 9.14±0.26c | |||

| OSACP2 | 1:4 | 38.97±1.07cd | 19.17±0.44cd | 50.05±1.76cd | 10.33±0.15cd | ||||

| OSACZ1 | ZnCl2 | 1:2 | 23.70±2.07ab | 12.33±0.94ab | 29.29±2.87ab | 5.82±0.65ab | |||

| OSACZ2 | 1:4 | 22.56±2.56ab | 11.80±1.58ab | 32.35±2.02b | 6.41±0.36b | ||||

| ASC | - | - | 43.25±2.65d | 21.32±1.22d | 51.40±0.90d | 11.10±0.35de | |||

| ASACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | 66.22±2.47e | 32.64±1.47e | 96.55±1.58f | 20.85±0.44f | |||

| ASACK2 | 1:4 | 84.63±1.35f | 41.69±0.55f | 98.18±2.23f | 21.20±0.10f | ||||

| ASACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | 44.12±2.25d | 21.73±1.43d | 58.77±1.10e | 12.13±0.25e | |||

| ASACP2 | 1:4 | 42.15±3.08d | 20.70±0.86d | 54.95±0.82de | 11.34±0.31de | ||||

| ASACZ1 | ZcCl2 | 1:2 | 24.29±2.57ab | 12.49±0.86ab | 33.14±1.25b | 6.58±0.33b | |||

| ASACZ2 | 1:4 | 15.45±4.22a | 8.07±2.30a | 25.11±1.83a | 4.98±0.43a | ||||

| Ci=500 mg L-1 – AD=2 g L-1 | Ci=500 mg L-1 – AD=5 g L-1 | ||||||||

| Carbon | Activating Agent | C/A Ratio (w/w) | AE, % | qe, mg g-1 | AE, % | qe, mg g-1 | |||

| OSC | - | - | 12.81±0.44c | 32.01±1.78bcd | 8.80±1.98ab | 10.02±2.28ab | |||

| OSACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | 21.68±1.73d | 53.75±5.97e | 38.75±3.44fg | 39.34±3.20ef | |||

| OSACK2 | 1:4 | 26.88±1.3d | 66.62±5.40e | 48.65±3.56h | 49.40±2.82g | ||||

| OSACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | 10.01±0.68abc | 24.40±1.91abc | 19.43±3.73cd | 19.67±3.87bc | |||

| OSACP2 | 1:4 | 9.84±1.41abc | 23.94±3.33abc | 22.14±1.99cd | 22.39±2.03c | ||||

| OSACZ1 | ZnCl2 | 1:2 | 7.73±1.39abc | 20.27±3.37abc | 6.57±1.34ab | 6.61±1.21a | |||

| OSACZ2 | 1:4 | 4.32±2.15a | 11.40±5.77a | 6.32±2.58ab | 6.34±2.48a | ||||

| ASC | - | - | 13.06±2.82c | 32.65±7.29cd | 15.33±2.00bc | 16.64±3.07bc | |||

| ASACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | 20.42±2.55d | 51.13±8.09de | 34.40±3.19ef | 34.95±3.27de | |||

| ASACK2 | 1:4 | 24.92±3.33d | 62.33±10.14e | 45.15±4.11h | 45.83±3.43fg | ||||

| ASACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | 12.37±2.90bc | 29.82±5.82abc | 25.27±2.10de | 25.58±2.26cd | |||

| ASACP2 | 1:4 | 12.82±2.00c | 31.29±5.22abcd | 25.07±1.48cde | 25.36±1.52cd | ||||

| ASACZ1 | ZnCl2 | 1:2 | 5.21±1.78ab | 13.63±4.41abc | 6.82±3.09ab | 6.83±2.92a | |||

| ASACZ2 | 1:4 | 4.42±1.07a | 11.62±2.77ab | 1.34±0.95a | 1.35±0.96a | ||||

| Ci=100 mg L-1 – AD=2 g L-1 | Ci=100 mg L-1 – AD=5 g L-1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | Activating Agent | C/A Ratio (w/w) | AE, % | qe, mg g-1 | AE, % | qe, mg g-1 | |||

| OSC | - | - | 62.58±5.70ab | 34.55±1.98abcd | 73.28±1.65ab | 16.34±0.37abc | |||

| OSACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | 100.00d | 52.25±2.15e | − | − | |||

| OSACK2 | 1:4 | 100.00d | 52.28±1.98e | − | − | ||||

| OSACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | 75.97±2.83c | 39.59±0.72cd | 83.82±1.50cd | 17.99±1.33bcd | |||

| OSACP2 | 1:4 | 74.44±5.00c | 38.86±2.60cd | 86.94±2.07d | 18.64±1.33cd | ||||

| OSACZ1 | ZnCl2 | 1:2 | 58.97±2.85a | 30.82±1.33ab | 68.30±0.23a | 14.81±1.15ab | |||

| OSACZ2 | 1:4 | 63.47±2.59ab | 33.29±2.47abc | 76.38±2.97bc | 16.39±1.25abc | ||||

| ASC | - | - | 75.56±4.04c | 41.45±1.28d | 100.00e | 22.30±0.01e | |||

| ASACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | 100.00d | 52.28±1.98e | − | − | |||

| ASACK2 | 1:4 | 100.00d | 52.25±2.04e | − | − | ||||

| ASACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | 79.28±3.67c | 41.18±2.62d | 89.65±2.91d | 19.25±1.51cde | |||

| ASACP2 | 1:4 | 73.04±1.86bc | 37.83±0.98bcd | 87.83±2.96d | 18.85±1.41cd | ||||

| ASACZ1 | ZcCl2 | 1:2 | 70.31±1.84bc | 36.80±2.06bcd | 78.90±2.66bc | 16.92±0.91abcd | |||

| ASACZ2 | 1:4 | 53.21±2.76a | 27.80±1.55a | 68.05±4.35a | 14.55±0.57a | ||||

| Ci=500 mg L-1 – AD=2 g L-1 | Ci=500 mg L-1 – AD=5 g L-1 | ||||||||

| Carbon | Activating Agent | C/A Ratio (w/w) | AE, % | qe, mg g-1 | AE, % | qe, mg g-1 | |||

| OSC | - | - | 27.02±3.05abc | 71.21±8.58a | 33.84±2.07a | 37.00±2.32a | |||

| OSACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | 56.94±4.29d | 141.77±14.37cd | 97.61±0.69e | 99.22±5.72d | |||

| OSACK2 | 1:4 | 75.14±5.69e | 186.16±18.96d | 100.00e | 101.41±5.24d | ||||

| OSACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | 35.70±4.06bc | 89.07±14.03ab | 58.63±2.72cd | 61.32±2.40bc | |||

| OSACP2 | 1:4 | 39.40±1.73c | 97.94±8.45abc | 62.84±1.08d | 65.81±2.07c | ||||

| OSACZ1 | ZnCl2 | 1:2 | 25.06±4.79abc | 62.60±14.36a | 34.56±3.52a | 36.81±3.23a | |||

| OSACZ2 | 1:4 | 23.93±4.05ab | 59.81±12.25a | 32.58±2.18a | 34.13±2.60a | ||||

| ASC | - | - | 33.35±3.02abc | 88.06±8.39a | 47.23±1.42b | 51.67±1.60b | |||

| ASACK1 | KOH | 1:2 | 56.34±1.87d | 140.27±13.88bcd | 93.58±0.93e | 95.08±5.85d | |||

| ASACK2 | 1:4 | 72.83±4.67e | 182.69±21.56d | 100.00e | 101.68d | ||||

| ASACP1 | H3PO4 | 1:2 | 37.26±1.16bc | 92.88±8.49abc | 52.38±3.09bc | 55.21±3.03bc | |||

| ASACP2 | 1:4 | 34.20±2.96abc | 85.45±12.30a | 55.96±3.92cd | 59.47±2.73bc | ||||

| ASACZ1 | ZnCl2 | 1:2 | 26.88±5.41abc | 67.59±18.12a | 35.64±1.93a | 37.54±1.32a | |||

| ASACZ2 | 1:4 | 20.54±5.33a | 51.77±16.72a | 29.95±2.02a | 31.57±2.61a | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).