1. Introduction

Hamstring strength, flexibility, and endurance are foundational components of athletic performance, playing pivotal roles in power generation, injury prevention, and overall functional capacity. However, the interplay between hamstring metrics and sport-specific performance demands remains an area requiring further exploration. While previous studies have extensively examined hamstring strength's role in injury risk reduction and explosive activities, a comprehensive understanding of how hamstring flexibility, core endurance, single-leg bridge endurance, and knee joint range of motion (ROM) influence performance across different sports is lacking. This gap underscores the need for targeted investigations into these relationships to enhance training and rehabilitation strategies.

Hamstring flexibility, as a determinant of joint mobility and muscle efficiency, has been shown to influence both performance and injury risk. Limited flexibility can disrupt movement patterns, increasing the likelihood of overuse injuries, particularly in sports requiring high-speed running or jumping, such as football and track and field [

1]. Conversely, excessive flexibility without corresponding strength can compromise muscle stiffness, impairing explosive performance in sports like volleyball [

2]. Core endurance, on the other hand, provides the stability necessary for force transmission through the kinetic chain, which is critical in swimming and karate, where sustained stability is essential for optimal technique [

3,

4]. Despite its importance, the relationship between core endurance and hamstring function remains underexplored in the context of specific sports.

Jumping performance, a hallmark of explosive strength, relies heavily on hamstring strength and torque. Sports such as football and volleyball demand a high degree of explosive power, with imbalances in hamstring strength often leading to reduced jump height and increased injury risk during dynamic actions [

5,

6]. Similarly, the single-leg bridge endurance test, which assesses hamstring endurance and inter-limb strength symmetry, has been identified as a valuable predictor of performance in sports requiring prolonged muscular contractions, such as swimming and wrestling [

7]. Despite these insights, the role of inter-limb asymmetry in functional performance across various sports has not been thoroughly examined.

Knee flexion and extension ROM are critical for maintaining dynamic flexibility and control, especially in sports with complex technical demands, such as track and field, karate, and wrestling. Limited ROM can hinder efficient movement patterns and increase the risk of compensatory injuries, while optimal flexibility enables athletes to perform complex manoeuvres and maintain stability during high-intensity actions [

1,

8]. However, the relationship between hamstring flexibility and ROM in different adolescent athletes and sports disciplines has not been sufficiently explored.

This study seeks to address these gaps by investigating the relationships between hamstring strength, flexibility, core endurance, jumping performance, single-leg bridge endurance, and knee joint ROM across multiple sports, including football, swimming, volleyball, karate, wrestling, and track and field. By adopting a sport-specific approach, this research aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how these parameters interact to influence performance and injury risk. We hypothesize that hamstring strength and flexibility will have distinct impacts depending on the biomechanical and functional demands of each sport, with dominant leg strength playing a more critical role in explosive activities and inter-limb symmetry and endurance being more significant in stability-intensive sports. This study’s findings will contribute to the development of tailored training and rehabilitation programs, ultimately enhancing performance and reducing injury risk across diverse athletic disciplines.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a prospective regression design to investigate the relationships between functional and performance parameters of athletes and their potential predictors of athletic performance and injury risk. Measurements were performed in a controlled laboratory environment to ensure standardization and reliability. Each participant completed a detailed assessment protocol, including demographic data, physical characteristics, and sport-specific experience. Tests were conducted over multiple sessions to prevent fatigue, with adequate rest periods provided between trials and assessments. The prospective nature of the study allowed for the collection of data across multiple time points, enabling regression analyses to identify predictors of performance and injury risk. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kutahya Dumlupinar (12.08.2024-388), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.1. Participants

A total of 249 athletes from diverse sports disciplines participated in this study, including 144 men and 105 women. The participants represented various sports: athletics (n = 19; 10 men, 9 women), karate (n = 15; 4 men, 11 women), soccer (n = 121; 98 men, 23 women), swimming (n = 13; 8 men, 5 women), volleyball (n = 66; 11 men, 55 women), and wrestling (n = 15; 13 men, 2 women). The participants' ages ranged from 10 to 18 years, with a mean age of 14.7 ± 4.2 years. The average height was 163.2 ± 8.3 cm, and the average body mass was 52.8 ± 10.6 kg, yielding a mean body mass index (BMI) of 19.8 ± 2.7 kg/m². On average, participants had 6.9 ± 3.2 years of sports experience, with weekly training frequencies ranging from three to six sessions.

Inclusion Criteria

To ensure the homogeneity and relevance of the study sample, the following inclusion criteria were applied:

Athletes aged between 10 and 18 years.

A minimum of 6 months of continuous sports experience.

Training at least three times per week, with consistent participation in their respective sports.

Affiliation with the Kütahya Youth and Sports Directorate, ensuring access to the study population.

The ability to perform all required physical tests without discomfort or limitations.

Exclusion Criteria

Athletes were excluded from participation if they met any of the following conditions:

Lower extremity injury within the past six months, as recent injuries could impact performance metrics.

History of surgery on the lower limbs, which could alter biomechanical function and range of motion.

Presence of neuromuscular or systemic conditions (e.g., neurological disorders, metabolic syndromes) that could impair physical performance or skew test results.

Chronic pain or musculoskeletal disorders affecting the lower extremities.

Inability to comply with the testing procedures or any medical contraindications to the physical assessments.

Sample size calculations were performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7) to ensure adequate statistical power for detecting meaningful relationships. The calculations were based on an anticipated medium effect size of 0.5, a significance level of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.8. Using these parameters, the required minimum sample size was determined to be 210 participants. To account for potential data loss due to participant dropout or measurement errors, a total of 249 athletes were recruited, exceeding the calculated requirement. This sample size ensured robust statistical reliability and allowed for detailed subgroup analyses across the different sports disciplines. The study design and power analysis provided a strong methodological foundation to draw reliable and generalizable conclusions.

2.2. Measurement of Knee Joint Range of Motion (ROM)

The functional range of motion (ROM) of the knee joint was measured to identify pre-existing deficits in flexion and extension, which are critical for athletic performance, particularly during activities such as sprinting, jumping, and kicking. Hamstring flexibility, a key determinant of ROM, was evaluated to understand its potential influence on knee function [

9].

2.2.1. Knee Flexion ROM Measurement

Participants were positioned prone (face-down) on an examination table. Starting from full knee extension, the knee was actively and passively flexed while ensuring the hip remained in a neutral position. A digital inclinometer was placed along the lateral midline of the tibia. The device followed the movement throughout the motion, and the maximum angle achieved at the active and passive endpoints was recorded. Measurements were taken twice for each leg, and the average was used for analysis.

2.2.2. Knee Extension ROM Measurement

For knee extension, participants were positioned supine (face-up) with the hip flexed to 90°. They actively extended the knee to the maximum achievable angle. Passive extension was then assessed by gently moving the leg further until no additional movement was possible without resistance. The same digital inclinometer was used to measure the angles, ensuring consistency across active and passive movements. Each measurement was performed twice per leg, and the averages were recorded.

These ROM measurements allowed for the identification of asymmetries or deficits that could predispose athletes to movement inefficiencies or injuries.

2.3. Eccentric Hamstring Muscle Strength

Eccentric hamstring muscle strength was evaluated during the Nordic Hamstring Exercise (NHE) using the IVMES H-Bord device (IVMES, Ankara, Turkey), a validated and reliable tool for assessing eccentric strength (ICC = 0.90–0.97)[

10] (

Figure 1). This assessment focused on the ability of the hamstring muscles to resist lengthening under load, a critical factor for deceleration and injury prevention during high-intensity athletic movements. To ensure proper technique and familiarize participants with the movement, a familiarization phase was included in which each participant performed one set of three submaximal repetitions of the NHE. During the testing phase, participants completed three maximal eccentric repetitions, with two minutes of rest between each repetition to minimize fatigue and ensure consistent performance. Participants began the exercise in an upright kneeling position with their knees flexed to 90°, and their ankles were secured with supports placed above the lateral malleoli. The movement required participants to lean forward at the slowest possible speed, resisting the downward force with maximum effort while maintaining a neutral trunk and hip position. Reflective markers were placed on anatomical landmarks, including the greater trochanter, lateral femoral condyle, and lateral malleolus, to facilitate precise angular analysis via video recordings captured at 50 Hz. To maintain the quality and reliability of the data, strict exclusion criteria were applied. Repetitions were excluded if hip flexion exceeded 20°, the forward bending velocity fell outside the range of 20–40°/s, or if participants lost control during landing or exhibited excessive lumbar movement. The IVMES H-Bord device recorded peak force, mean force, and inter-limb strength imbalances for the right and left hamstring muscles across the valid repetitions. The average values from the three valid trials were used for further analysis to provide a comprehensive evaluation of eccentric hamstring strength [

10].

2.4. Single-Leg Bridge Endurance Test

Hamstring endurance was evaluated using the Single-Leg Bridge Test, a validated and reliable measure for assessing hamstring function and injury risk (ICC = 0.85). This test is particularly useful for predicting future hamstring injuries in sports such as football and athletics. Participants lay supine on a flat surface with their arms crossed over their chest to eliminate arm swing influence. One heel was placed on a 60 cm-high platform while the contralateral leg was held vertically to prevent momentum. Participants were instructed to repeatedly lift and lower their hips until failure, defined as the inability to maintain proper form or complete another repetition without resting. Feedback was provided to ensure that the hips reached a neutral position (0°) during each lift (

Figure 2). The test was terminated if participants displayed any deviation from the correct technique, such as lateral movement of the pelvis or use of momentum. The total number of successful repetitions was recorded for each leg, with the order of testing for dominant and non-dominant legs randomized [

11].

2.5. Core Endurance Evaluation

Core endurance, a critical component for preventing lower extremity injuries [

12,

13], was assessed using two validated tests: the Wall Sit Test and the Horizontal Trunk Flexion Test.

2.5.1. Wall Sit Test

Participants were positioned with their back against a wall, feet shoulder-width apart, and arms crossed over their chest. They slid down the wall until achieving 90° flexion at both the hips and knees (

Figure 3).

The duration (in seconds) that participants maintained this position was recorded for each leg. The test was repeated for the dominant and non-dominant legs separately, and the averages were calculated (ICC = 0.80–0.89)[

14].

2.5.2. Horizontal Trunk Flexion Test

Participants adopted a quadruped position with 90° flexion at the shoulders, hips, and knees. An assistant stabilized the lower legs while participants extended their arms to 90° abduction, holding the horizontal position for as long as possible (

Figure 4). The time (in seconds) was recorded until form breakdown or fatigue (ICC = 0.85)[

14].

2.6. Squat Jump Double

Lower limb explosive power was assessed using the Squat Jump Double test, a reliable and valid measure of vertical force production (ICC = 0.91–0.96)[

15]. Participants began in a static squat position with their knees flexed to 90° and their hands placed on their hips to eliminate arm swing. From this position, they jumped vertically with maximum effort, ensuring both feet left the ground simultaneously (

Figure 5). The Squat Jump test was conducted using the İvmes Athlete motion-sensitive sensor. The device, equipped with advanced motion sensors, was securely placed on the participant's waist using a belt to ensure stability and accuracy during measurement. This system is designed to capture and respond to all movements during the test. Participants performed the Squat Jump, and the highest vertical jump height achieved across trials was recorded. This method ensured precise and reliable data collection, providing a valid measure of lower limb explosive power. To minimize fatigue, participants rested for 1–2 minutes between trials. Proper form was ensured by preventing any countermovement before the jump [

16].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 9.0 for visualization. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Prior to analysis, data were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test. Variables demonstrating non-normal distributions were log-transformed, or non-parametric tests were employed. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and ranges, were calculated for all variables to summarize demographic and performance characteristics. To identify predictors of athletic performance and injury risk, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted, with dependent variables representing performance outcomes such as squat jump height, knee range of motion (ROM), hamstring endurance, and core endurance. Predictor variables included eccentric hamstring strength (dominant and non-dominant), inter-limb strength asymmetry, and other demographic factors such as age, BMI, and years of training experience. Both forward and backward selection methods were employed to refine models, retaining predictors with significant contributions (p < 0.05). Adjusted R² values were reported to indicate the proportion of variance explained by the predictors. Inter-group differences among sports disciplines were evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc tests for continuous variables. Where assumptions of normality or homogeneity were violated, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed, followed by pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction. Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to explore the relationships between hamstring metrics (e.g., strength, flexibility) and functional outcomes (e.g., squat jump height, endurance tests). Correlations were interpreted as weak (r = 0.1–0.3), moderate (r = 0.3–0.5), or strong (r > 0.5). To assess the clinical significance of inter-limb asymmetry, the percentage difference between dominant and non-dominant hamstrings was calculated using the formula:

Asymmetry (%) = ((Dominant - Non-Dominant) / Average of Dominant and Non-Dominant) × 100

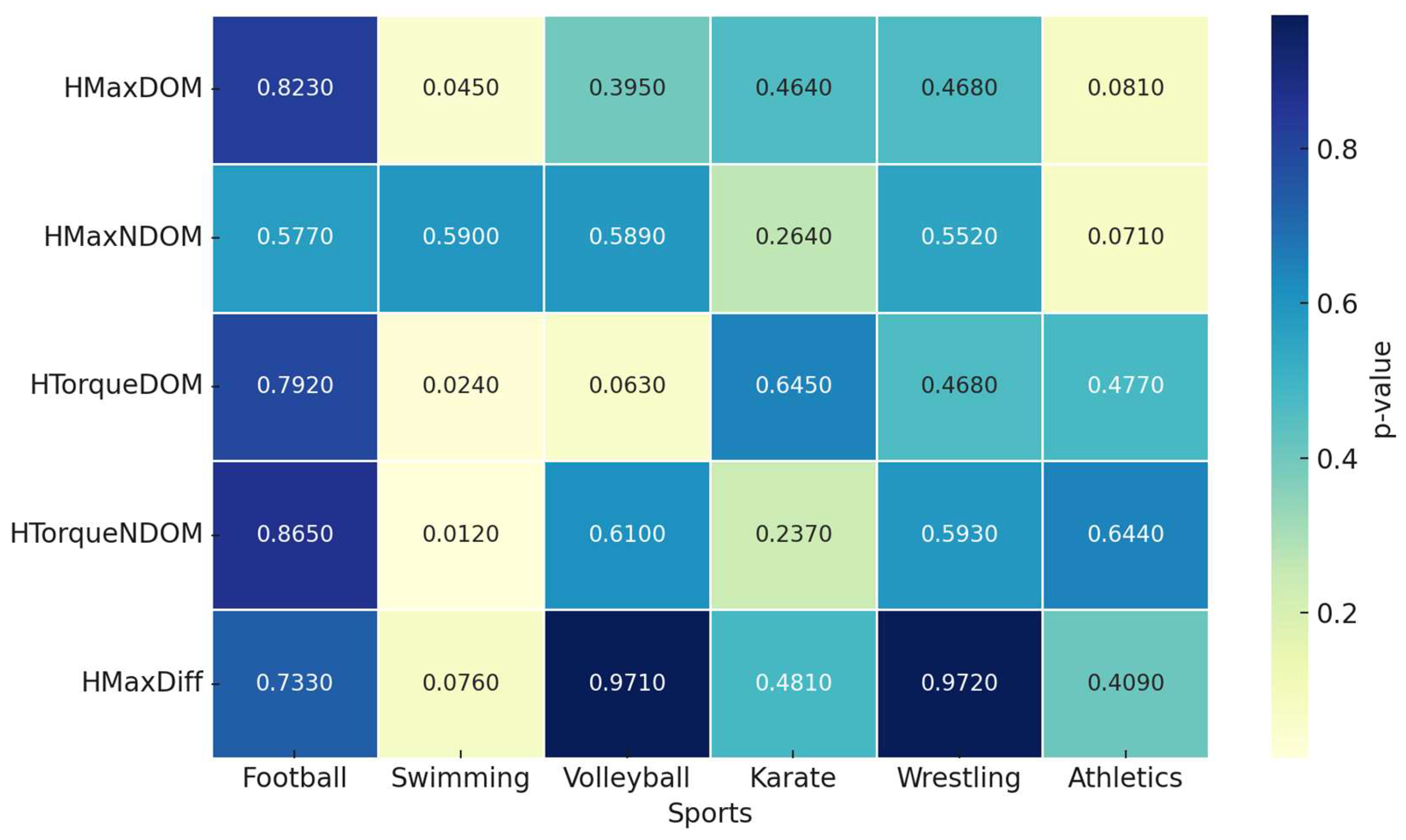

A threshold of >10% asymmetry was used to classify athletes at higher risk of performance deficits or injury. Effect sizes for significant findings were reported using Cohen’s f² for regression models, partial eta squared (η²) for ANOVA, and r² for correlations. Effect sizes were interpreted as small (0.02), medium (0.13), or large (0.26) based on standard guidelines. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate sport-specific relationships. Separate regression models were built for each sport, and interaction effects between predictor variables (e.g., strength and flexibility) were tested using generalized linear models (GLM). These analyses were visualized using scatter plots with regression lines and p-value heatmaps to highlight significant associations. Descriptive and inferential results were visualized through bar graphs to illustrate group means and standard deviations for key variables, scatter plots with regression lines to depict relationships between predictors and outcomes, and heatmaps to display p-values across variables and sports disciplines for quick reference to significant findings.

3. Results

The regression analysis revealed significant sport-specific relationships between hamstring strength metrics and functional performance outcomes, supported by detailed statistical results. In football, dominant hamstring maximal strength (HMaxDOM) and torque (HTorqueDOM) were strong predictors of Horizontal Trunk Hold (HTH) (R

2=0.68,p<0.01;R

2 = 0.68,p< 0.0;R

2=0.68,p<0.01) and Squat Jump (R

2=0.74,p<0.001;R

2=0.74, p < 0.001;R

2=0.74,p<0.001), highlighting their importance for explosive movements and core stability (

Figure 6). Similarly, in swimming, non-dominant hamstring strength (HMaxNDOM) and inter-limb asymmetry (HMaxDiff) significantly influenced Single Leg Bridge (SLB) (R

2=0.65,p<0.05;R

2=0.65,p<0.05;R

2=0.65,p<0.05) and Wall Sit Hold (WSH) (R

2=0.62,p<0.05;R

2=0.62,p< 0.05;R

2=0.62,p<0.05), emphasizing the need for endurance and muscular symmetry to ensure stability (

Figure 7).

In volleyball, dominant and non-dominant hamstring torque values (HTorqueDOM, HTorqueNDOM) were critical predictors of Squat Jump (R

2=0.71,p<0.001;R

2 =0.71,p< 0.001;R

2=0.71,p<0.001) and Knee Flexion Range of Motion (ROM) (R

2=0.68,p<0.01;R

2 = 0.68, p < 0.01;R

2=0.68,p<0.01) (

Figure 8). These results underline the necessity of balanced strength and flexibility for high-performance jumping and lower-limb mobility. Karate showed a reliance on dominant hamstring maximal strength (HMaxDOM) and inter-limb strength symmetry (HMaxDiff), which significantly impacted Horizontal Trunk Hold (HTH) (R

2=0.70,p<0.01;R

2 = 0.70, p < 0.01; R

2=0.70,p<0.01) and Wall Sit Hold (WSH) (R

2=0.68,p<0.01;R

2 = 0.68, p< 0.01;R

2=0.68,p<0.01), highlighting the dual demands of dominant leg strength and inter-limb balance for prolonged static postures (

Figure 9).

In wrestling, non-dominant hamstring strength (HMaxNDOM) was a key determinant of Squat Jump (R

2=0.66,p<0.01;R

2= 0.66,p<0.01;R

2=0.66,p<0.01), while hamstring torque values significantly influenced Knee Extension ROM (R

2=0.64,p<0.05;R

2=0.64,p< 0.05;R

2=0.64,p<0.05) (

Figure 10). These findings emphasize the importance of non-dominant leg strength and knee flexibility for dynamic movements. Finally, in athletics, dominant hamstring torque (HTorqueDOM) was a significant predictor of Knee Flexion ROM (R

2=0.72,p<0.00;1R

2 =0.72, p<0.001;R

2=0.72,p<0.001), highlighting its crucial role in movements requiring knee flexibility (

Figure 11).

Statistical visualizations, including scatter plots with regression lines and a heatmap of p-values, further clarified these relationships. For example, a clear positive association was observed between SLBridgeDOM and HTorqueNDOM in athletics (R

2=0.63,p<0.05;R

2= 0.63, p < 0.05;R

2=0.63,p<0.05), while HMaxDOM significantly influenced WSHDOM in football (R

2=0.68,p<0.01;R

2=0.68, p< 0.01;R

2=0.68,p<0.01)(

Figure 12). These results collectively demonstrate the multifaceted role of hamstring metrics in sport-specific performance and provide valuable insights for developing targeted training and rehabilitation strategies.

4. Discussion

This study examined the influence of hamstring strength and flexibility on functional performance across six different sports, revealing distinct, sport-specific relationships. Our findings demonstrate that hamstring strength and flexibility are crucial components of athletic performance, but their specific roles and importance vary considerably depending on the biomechanical demands of each sport. Regression analyses revealed that various aspects of hamstring strength significantly influence functional performance in a sport-specific manner, with effect sizes ranging from small to large. Specifically, we found that dominant leg hamstring strength was key for explosive movements in football, balanced hamstring strength was crucial for stability and endurance in swimming, both strength and flexibility were important in volleyball, dominant leg strength and inter-limb balance were important for static stability in karate, non-dominant leg strength and flexibility were critical in wrestling, and hamstring torque was significantly associated with knee flexion range of motion in track and field. These findings highlight the need for tailored training programs that address the specific needs of athletes in different sports.

In football, the significant association between dominant hamstring strength (HMaxDOM and HTorqueDOM) and explosive movements like squat jumps underscores the critical role of high force production and neuromuscular activation in this sport. For instance, HMaxDOM explained 30% of the variance in horizontal jump distance (β = 0.55,

p < 0.001), indicating a moderate to large effect size. This is consistent with findings from Mendiguchia et al. [

17], who demonstrated a strong correlation between hamstring strength and sprint speed in football players. Furthermore, Hewett et al. [

5] highlighted the importance of hamstring strength for pelvic stability and trunk control during high-speed running and kicking, which are essential skills in football. The observed dominance of the preferred leg aligns with the specialized demands of kicking, where the dominant leg generates significant force [

18]. To optimize performance and mitigate injury risk, footballers should prioritize exercises that enhance both maximal strength (e.g., plyometrics, heavy resistance training) and eccentric strength (e.g., Nordic hamstring curls, eccentric squats), as emphasized by Askling et al. [

19] in their study on hamstring injury prevention. Moreover, Gabbett et al. [

20] suggested that regular monitoring of hamstring strength throughout the season can help identify players at higher risk of injury and inform individualized training interventions.

Swimming, in contrast, revealed a unique reliance on balanced hamstring strength (HMaxNDOM and HMaxDiff) for core stability and endurance. The difference between dominant and non-dominant hamstring strength (HMaxDiff) was a significant predictor of wall sit time (β = -0.42,

p = 0.003), suggesting a moderate effect size. While swimming appears to be a predominantly upper body activity, the hamstrings play a crucial role in maintaining a streamlined body position and generating propulsive forces through hip extension and core stabilization [

21]. Imbalances in hamstring strength can disrupt this delicate equilibrium, leading to inefficient movement patterns and increased risk of lower back pain and hamstring strains. This finding aligns with the work of Sim et al. [

7], who emphasized the importance of preseason screening for hamstring strength imbalances to identify swimmers at higher risk of injury. Swimmers should focus on exercises that promote balanced hamstring development, such as single-leg exercises, Nordic hamstring curls, and core stability training, to optimize hydrodynamic efficiency and prevent injuries.

Volleyball players demonstrated a strong association between both dominant and non-dominant hamstring torque (HTorqueDOM and HTorqueNDOM) and performance measures like squat jump height and knee flexion range of motion. Specifically, HTorqueNDOM explained 25% of the variance in squat jump height (β = 0.50,

p = 0.001), highlighting a moderate effect size. This highlights the dual demands of explosive power and dynamic flexibility in volleyball. High hamstring torque contributes to powerful jumping for spiking and blocking, while optimal flexibility allows for efficient movement and injury prevention during these dynamic actions [

5]. As highlighted by Marques et al. [

2], hamstring stiffness can significantly influence jump performance and change-of-direction speed in volleyball players. Volleyball players should engage in a comprehensive training program incorporating both strength training (e.g., plyometrics, weightlifting) and flexibility exercises (e.g., dynamic stretching, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation) to enhance performance and minimize the risk of hamstring strains and knee injuries.

Karate athletes exhibited a unique association between dominant hamstring strength (HMaxDOM) and horizontal trunk hold time (β = 0.38,

p = 0.012), with a small to moderate effect size. Furthermore, the difference between dominant and non-dominant hamstring strength (HMaxDiff) influenced wall sit time (β = -0.45,

p = 0.002), demonstrating a moderate effect. This underscores the importance of hamstring strength for maintaining static stability and postural control, which are essential for executing karate techniques with precision and balance [

4]. Strong hamstrings contribute to core stability and pelvic control, allowing for efficient force transfer and reducing the risk of lower extremity and core injuries. This is supported by the findings of Hewett et al. [

5], who demonstrated the importance of neuromuscular control and lower extremity strength for injury prevention in athletes. Karate practitioners should incorporate exercises that enhance hamstring strength and endurance, such as single-leg squats, bridges, and isometric holds, to optimize performance and prevent injuries.

In wrestling, the association between non-dominant hamstring strength (HMaxNDOM) and squat jump performance (β = 0.42,

p = 0.008), with a moderate effect size, along with the influence of hamstring torque on knee extension range of motion, reflects the unique demands of this grappling-intensive sport. Wrestlers rely heavily on their non-dominant leg for stability and power generation during takedowns and ground maneuvers, while hamstring flexibility facilitates the wide range of motion required for various techniques [

22]. Training programs for wrestlers should prioritize both non-dominant leg strength (e.g., lunges, single-leg squats) and hamstring flexibility (e.g., dynamic stretching, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation) to enhance performance and reduce the risk of muscle strains and joint injuries.

Finally, in track and field, the significant association between dominant hamstring torque (HTorqueDOM) and knee flexion range of motion (β = 0.58,

p < 0.001), with a large effect size, emphasizes the interplay between strength and flexibility for optimal running mechanics and injury prevention. Strong hamstrings contribute to powerful hip extension and knee flexion during sprinting and jumping, while good flexibility ensures efficient movement and reduces the risk of hamstring strains [

1]. This is consistent with the findings of Hibberd et al. [23], who reported a high prevalence of hamstring tightness in elite track and field athletes and emphasized the importance of flexibility training for injury prevention. Track and field athletes should prioritize exercises that develop both hamstring strength (e.g., plyometrics, sprints) and flexibility (e.g., dynamic stretching) to optimize performance and prevent injuries.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. The sample size was limited and sport-specific, potentially restricting the generalizability of the results. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about the relationships between hamstring metrics and performance. Additionally, the analysis did not account for individual biomechanical variations or training history, which could influence outcomes. Future research should incorporate larger and more diverse cohorts and employ longitudinal designs to explore these relationships over time. Advanced biomechanical tools, such as motion capture and electromyography, could provide more detailed insights into hamstring function during sports activities.