1. Introduction

The challenge of establishing a solid physical basis for explaining the emergence of organized biological systems has troubled scientists for quite some time. A parallel situation emerged in the early 20th century within the realms of physics and chemistry. All scientists were of the belief that if they could discern the governing physical laws for each individual component of a chemical system, they could subsequently describe its properties as a function of these physical variables. While this notion was theoretically sound, it proved impractical in practice, as the theories of physical science remained incomplete to this task until the advent of quantum theory.

A similar predicament exists in the relationship between physics and biology. In theory, understanding the physical evolution of each constituent part of a biological system should enable us to describe any biological system. However, this aspiration encounters significant obstacles, not only due to the immense computational demands it entails but also because it conflicts with the established law of entropy increase. Many researchers share the conviction that this law is incomplete and a general principle exists.

The research on order generation and matter self-assembling in the field dates back to the 1930s [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Various extremal principles have been proposed for self-organized regimes governed by classical linear and non-linear non-equilibrium thermodynamic laws, with particular emphasis on stable stationary configurations.

However, a comprehensive understanding remains elusive. In 1945, Prigogine [

1,

2] introduced the "Theorem of Minimum Entropy Production," which applies exclusively to near-equilibrium stationary states. Prigogine's proof has faced substantial criticism [

3]. Šilhavý [

4] suggests that the extremal principle of near-equilibrium thermodynamics lacks a counterpart for far-from-equilibrium steady states, despite claims in the literature.

Sawada [

5], in the context of Earth's atmospheric energy transport, proposed the principle of the largest entropy increment per unit time. He cited Malkus and Veronis's work in fluid mechanics [

6], which demonstrated the principle of maximum heat current, as a particular example of maximum entropy production given certain assigned boundary conditions. However, this inference is not generally valid.

The concept of energy dissipation rate first appeared in Onsager's work [

7] on this subject. Grandy [

8] extensively discussed potential principles related to extremal entropy production and/or energy dissipation rates. He pointed out the challenge of defining the rate of internal entropy production in general cases, suggesting that, for predicting the course of a process, the extremum of the rate of energy dissipation may be more useful than that of entropy production.

Sawada and Suzuki [

9] confirmed, through numerical simulations and experiments, the maximum rate of energy dissipation in electro-convective instabilities. To this day, the debate continues regarding the principle of maximum free energy dissipation (MFED) and Prigogine's principle.

An alternative approach to understanding far-from-equilibrium evolution can be formulated using Langevin equations, which describe dynamics at a coarse-grained scale in some cases. Langevin equations can be derived using various techniques, such as the Poisson transformation [

10] and Fock space formalism [

11]. Exact formulations exist occasionally for non-linear reaction kinetics and a few other problems. In some cases, a Langevin equation can be assumed from a phenomenological standpoint, where the approximate dynamics are decided a priori. However, achieving a rigorous Langevin description in this context is challenging.

The way out is to derive satisfactory Langevin equations from a microscopic model. In this work, we employ the stochastic generalization of the Madelung’s quantum hydrodynamic analogy [

12,

13,

14,

15] as microscopic model from which to derive the classical non-equilibrium kinetics emerging at the coarse-grained macro-scale.

Prigogine's work is not applicable under conditions far from equilibrium because it derives the system's entropy production through a series expansion, which is essentially a semi-empirical approach with a limited range of convergence and lacking connections to microscopic physical variables rooted in quantum physics. Consequently, the limitations of Prigogine's theory stem from its classical foundations.

Conversely, a more fundamental approach could, in principle, be adopted by treating any far-from-equilibrium system as a quantum system. In this case, the evolution of the system's wavefunction would also need to account for its incoherent dynamics, leading to irreversible phenomena on a macroscopic scale. Although complex, if we can employ the quantum model to derive a coarse-grained macroscopic description, a more fundamental criterion for the system's spontaneous progression should naturally emerge. The limitation of this approach lies in the fact that the connection between quantum mechanics and classical mechanics remains unclear and is the subject of ongoing, intense, and contentious debate. [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

To address this theoretical gap, there are various interpretations of quantum mechanics available, such as the many-worlds interpretation [

16], Bohmian mechanics [

17,

18], modal interpretation [

19], relational interpretation [

20], consistent histories [

21], transactional interpretation [

22,

23], QBism [

24], Objective collapse theories [

25], Madelung quantum hydrodynamics [

26], and decoherence approach [

27].

The decoherence approach explores the idea of achieving the statistical mixture by means of the loss of quantum coherence caused by the presence of the environment. Decoherence is observed to occur within the system by considering it as a sub-part of larger quantum system, with its interaction being semi-empirically defined through non-unitary interactions [

27].

The proposed solution for the evolution of irreversible systems is achieved through a local quantum pseudo-diffusional effect [

28], where the system is embedded in a vastly large environment. This behavior, driven by quantum diffusion, but with a non-definite positive diffusion coefficient, implies a recurrence time—a period after which the entire system returns to its initial state [

29] with an anti-entropic evolution. However, the success of decoherence theory depends on the exceedingly long duration of this recurrence time.

Furthermore, the quantum pseudo-diffusional effect requires that simultaneous anti-entropic changes occur in other regions of the overall quantum system before the recurrence time elapses. This issue is addressed by assuming an infinite environment, thereby making the probability of these anti-entropic effects occurring within the local system approach zero. The major objections to this view are that such spontaneous anti-entropic phenomena have not been observed anywhere in the universe, and the assumption of distinguishability between the system and its environment subtly reintroduces the condition that the global system is classical.

The role of environmental fluctuations in quantum decoherence is also confirmed through experimental and numerical simulations, which provide strong evidence that decoherence and the localization of quantum states result from interactions with stochastic and gravitational fluctuations [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

The quantum-to-classical transition, the role of the observer, the existence of pre-measurement reality, and the self-sustained classical state of the global system are long-standing, fundamental unresolved issues in modern physics [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] the EPR paradox, von Neumann theorem, and related works]. Nevertheless, some approaches, such as Bohm's non-local hidden variable theory and Objective Collapse models, have introduced new insights, advancing scientific thought. Recently, by incorporating the effect of the gravitational background—considered as spatiotemporal curvature fluctuations—into Madelung quantum hydrodynamics, the author has proposed a stochastic hydrodynamic theory [

41] that potentially resolves quantum paradoxes and reconciles relativistic locality with quantum non-locality. The gravitational stochastic background, stemming from relics of the Big Bang and the general relativistic dynamics of bodies, causes the reference system to become interconnected with the dynamics of bodies. This noise acts as an external system or thermostat, though it is not truly external to the system. From this perspective, the universal quantum system is self-fluctuating, and on a scale larger than the de Broglie wavelength, it gradually loses quantum coherence, giving rise to classical mechanics.

The Madelung approach, a specific case of the Bohm mechanics [

39], has the important characteristic of being both mathematically equivalent to the Schrödinger approach [

12,

13.

26] and treating the evolution of the wave function in a classical-like way, as the motion of a mass density

governed by the impulse

.

The Madelung description offers the advantage of a controlled transition to classical mechanics when the so-called quantum pseudo-potential tends to zero [

40]. However, manually removing the quantum potential from the quantum hydrodynamic equations to derive classical mechanics is mathematically unjustified and invalid, as it effectively eliminates stationary quantum eigenstates and significantly alters the mathematical structure of the equations of motion. Therefore, to account for the effect of the quantum potential in the presence of random fluctuations and bridge the gap between the quantum non-local and classical descriptions, a more rigorous and analytical approach within the hydrodynamic framework is required [

40].

The Stochastic Quantum Hydrodynamics Model (SQHM) explains the emergence of a large-scale classical state as resulting from the loss of quantum entanglement, due to the shielding of the quantum potential at the wavefunction tails by noise fluctuations. This effect causes global wavefunction decay (collapse) and quantum decoherence in systems whose components are separated by exceedingly large distances, leading to statistical mixing and classical behavior. From this perspective, the SQHM aligns with Objective Collapse Theories. The unique feature of SQHM is that it focuses on the strength of the quantum potential, originating from wavefunction tails, as the key factor determining whether a macroscopically large system is in a classical state, rather than its infinitesimal mass density.

This formulation aligns with recent studies that explore the transition from quantum to classical dynamics by incorporating stochastic elements into the quantum hydrodynamic framework [

41]

The stochastic extension of the Madelung quantum hydrodynamic equations can provide an analytical unitary description from microscopic quantum dynamics to macroscopic behavior. As a result, it offers a way to explore the quantum foundations of irreversibility in far-from-equilibrium conditions and may lead to the formulation of a broader physical principle governing the emergence of spontaneous order and self-assembly of matter

2. The Quantum Stochastic Hydrodynamic Model

The Madelung quantum hydrodynamic representation transforms the Schrodinger equation [

12,

13,

26]

for the complex wave function

, into two equations of real variable: the conservation equation for the mass density

and the motion equation for the momentum

,

where

and where

Following the scientific hypothesis that considers the gravitational background noise (GBN) as a source of quantum decoherence [

42], first proposed in the Calogero conjecture [

43] and by introducing it into Madelung quantum hydrodynamics, equation (1.4) yields a generalized stochastic quantum model capable of describing wavefunction collapse dynamics and the measurement process, leading to a fully self-consistent quantum theory.

The fluctuating energy content of GBN leads to local variations in equivalent mass density. As shown in [

40], the SQHM is defined by the following assumptions:

The additional mass density generated by GBN is described by the wavefunction with density ;

The associated energy density of GBN is proportional to ;

The additional mass is defined by the identity

The additional mass is assumed to not interact with the mass of the physical system (since the gravitational interaction is sufficiently weak to be disregarded).

Under this assumption, the wavefunction of the overall system

reads as

Additionally, given that the energy density

of GBN is quite small, the mass density

is presumed to be significantly smaller than the body mass density typically encountered in physical problems. Hence, considering the mass

to be much smaller than the mass of the system, in Equations (3) and (4) we can assume

. Thence, by introducing the mass density fluctuations, through

, into the quantum potential (4), following the procedure given in reference [

40], it is possible for the complex field

to obtain the quantum-stochastic hydrodynamic equations of evolution that, for systems whose physical length is of order of the De Broglie length, reads

Given the physical length of the system

, the diffusion coefficient in (7) can be readjusted as

where

is a positive pure number, depending by the characteristics of the system [

40], and

is the De Broglie length defining physical distance below which the quantum coherence is maintained in presence of fluctuations since for

or

the Madelung quantum deterministic limit is recovered.

In fact, given the semiempirical parameter

defined by the identity [

40 and references therein]

expressing the ability of the system to dissipate energy, it is possible to show [

40] that

and therefore that the conventional quantum mechanics in the form of the quantum hydrodynamic representation (1-4) is recovered for noise amplitude tending to zero or equivalently for microscopic systems whose physical length is much smaller than the De Broglie length.

In the quantum-stochastic hydrodynamic representation,

is the probability mass density (PMD) determined by the probability transition function

[

44] obeying to the Smoluchowski conservation equation [

44] for the Marcovian process (7)

establishing the phase-space mass density conservation

that leads to the mass density distribution

in the spacetime

In the context of (7-9), does not denote the quantum wavefunction; rather, it represents the generalized quantum-stochastic probability wave. that adheres to the limit.

It is worth noting that the SQHM equations (7-9), stemming from the presence of noise curvature wrinkles of spacetime (a form of dark energy) both of relic origin from big bang and from bodies dynamics in curved spacetime, describe a self-fluctuating quantum system where the noise is an intrinsic property of the reference system that is not generated by an environment. An in-depth discussion regarding the property of true randomness or pseudo-randomness of the gravitational background noise is provided in

section 3.1.1. .

2.1. Emerging Classical Mechanics on Large Size Systems

When manually nullifying the quantum potential in the equations of motion for quantum hydrodynamics (1-3), the classical equation of motion emerges [

13]. However, despite the apparent validity of this claim, such an operation is not mathematically sound as it alters the essential characteristics of the quantum hydrodynamic equations. Specifically, this action leads to the elimination of stationary configurations, i.e., quantum eigenstates, as the balancing force of the quantum potential against the Hamiltonian force [

24]—which establishes their stationary condition—is eliminated. Consequently, even a small quantum potential cannot be disregarded in conventional quantum mechanics representing the zero-noise 'deterministic' limit of the quantum-stochastic hydrodynamic model (7-9)."

Conversely, in the stochastic generalization, it is possible to correctly neglect the quantum potential in (7) when its force is much smaller than the force noise

such as, by (7),

that leads to condition

and hence, in a coarse-grained description with elemental cell side

, such as

where

is the physical length of the system.

It is worth noting that, despite the noise

having a zero mean, the mean of the fluctuations in the quantum potential, denoted as

, is not null. This not-null mean contributes to the frictional dissipative force

in equation (7). Consequently, the stochastic sequence of noise inputs disrupts the coherent dynamic evolution of the quantum superposition of states, leading them to decay to a stationary mass density distribution with

. Moreover, by observing that the stochastic force noise

grows with the size of the system, for macroscopic systems (i.e.,

), condition (17) can be satisfied if

In order to achieve a large-scale description completely free from non-local quantum potential interaction, a more stringent requirement can be imposed, such as

Recognizing that since for linear systems it holds

we readily can observe that these systems are incapable of generating macroscopic classical phases. Generally speaking, as the Hamiltonian potential strengthens, the wave function localization increases, and the quantum potential behavior at infinity becomes more prominent.

In fact, by considering the mass density

where

is polynomial of order

k, it becomes evident that a vanishing quantum potential interaction at infinity is achieved for

.

On the other hand, for instance, for gas phases with particles that interact by the Lennard-Jones potential, whose long-distance wave function reads [

45]

leading to the quantum potential

developing the quantum force

in a sufficiently rarefied phase, can lead to large-scale classical behavior [

40]

It is interesting to note that in (25), the quantum potential coincides with the hard sphere potential of the “pseudo potential Hamiltonian model” of the Gross-Pitaevskii equation [

46,

47], where

is the boson-boson s-wave scattering length.

By observing that, to fulfill condition (21), we can sufficiently require that

so that it is possible to define the quantum potential range of interaction

as [

40]

Relation (28) provides a measure of the range of interaction associated with quantum non-local potential.

It is worth noting that the quantum non-local interaction extends up to a distance on the order of the largest length between and .. Below , a weak quantum potential emerges due to the damping of the noise. However, above and below , the quantum potential is strong enough not to be shielded by fluctuations, leading to the emergence of quantum behavior.

Therefore, quantum non-local effects can be extended by increasing as a result of lowering the temperature or by strengthening the Hamiltonian potential, which leads to larger values of . In the latter case, for instance, larger values of can be achieved by extending the linear range of Hamiltonian interaction between particles

For instance, when examining phenomena at intermolecular distances where the interaction is modeled as linear, the behavior exhibits quantum characteristics (e.g., X-ray diffraction from a crystalline lattice). However, when observing macroscopic behaviors, such as elastic sound waves, which primarily depend by the non-linear part of the Lennard-Jones interatomic potential without affecting the linear part, classical behavior emerges.

2.2. The Lindemann Constant at the Melting Point of Quantum Lattice

A validation test for the SQHM can be conducted by comparing its theoretical predictions with experimental data on the transition from a quantum solid lattice to a classical amorphous fluid. Specifically, we show that the SQHM can theoretically derive the Lindemann constant at the melting point of a solid lattice, representing the quantum-to-classical transition threshold, something that has remained unexplained within the frameworks of both conventional quantum and classical theories.

For a system of Lennard-Jones interacting particles, the quantum potential range of interaction

reads

where

(with

) represents the distance up to which the interatomic force is approximately linear, and

denotes the atomic equilibrium distance.

The physical significance of the quantum potential length of interaction is evident during the quantum-to-classical transition in a crystalline solid at its melting point.

Assuming that, to preserve quantum coherence within the quantum lattice, the atomic wave function (around the equilibrium distance) extends over a distance smaller than the quantum coherence length, the square root of its variance must result smaller than which corresponds to the melting point.

Based on these assumptions, the Lindemann constant

defined as [

44]

can be expressed as

and it can be theoretically calculated, as

that, being typically

and

, leads to

A more precise assessment, utilizing the potential well approximation for molecular interaction [

48], results in

, and yields a value

for the Lindemann constant consistent with measured values, falling within the range of 0.2 to 0.25 [

44].

2.3. The Fluid-Superfluid Transition

If the Lindemann constant is derived from a quantum-to-classical transition governed by the strength of the Hamiltonian interaction, which determines the quantum potential interaction length, another validation of the SQHM can be obtained by its predictions on transitions induced by the change of De Broglie physical length such as the fluid-to-superfluid transition.

Given that the De Broglie distance

is temperature-dependent, it impacts on the fluid-superfluid transition in monomolecular liquids at extremely low temperatures, when it equals the mean molecular distance as observed in

. The approach to this scenario is elaborated in reference [

48,

49], where, for the

-

interaction, the potential well is assumed to be.

In this context,

represents the Lennard-Jones potential depth,

denotes the mean

-

inter-atomic distance where

.

As the superfluid transition temperature is attained, the De Broglie length overlaps more and more the

-

wavefunctions within the potential depth. Therefore, we observe the gradual increase of

superfluid concentration within the interval

Therefore, the total superfluid occurs as soon as the De Broglie length covers all the - potential well for .

However, for

, we have no superfluid

. Therefore, given that

when

, the superfluid-to-normal

density ratio of 50% is reached at the temperature

where the

mass is assumed to be

, in good agreement with the experimental data

measured in reference [

50].

On the other hand, given that for

, all pairs of

enter the quantum state, the superfluid ratio of 100% is attained at the temperature

also consistent with the experimental data from reference [

50], which is approximately

.

Moreover, by employing the superfluid ratio of 38% at the

-point of

, such that

, the transition temperature

is determined to be

in good agreement with the measured superfluid transition temperature of

.

It is worth noting that there are two ways to establish quantum macroscopic behavior. One approach involves lowering the temperature, effectively increasing the de Broglie length. The second approach is to strength the Hamiltonian interaction, among the particles, to enhance the quantum potential length of interaction. The latter effect can be achieved simply by increasing the distance over which the Hamiltonian interaction remains linear. In the forme case the De Broglie length induces a strong and macroscopic quantum behavior, while in the latter one, induce by the quantum potential range of interaction, the quantum behavior is weaker and is limited to the electron delocalization bringing to the normal metal conductivity.

From this standpoint, we can conceptualize the classical mechanics as emergent from a decoherent outcome of quantum mechanics when fluctuating spacetime reference background is involved.

It is also important to highlight that the limited strength of the Hamiltonian interaction over long distances is the key factor allowing classical behavior to manifest.

Moreover, by observing that systems featuring interactions that are weaker than linear interactions are classically chaotic, it follows that the classical cahoticity is widespread characteristic of the classical reality.

To this respect, the strong divergence of chaotic trajectories of motion due to high Lyapunov exponents also contributes to facilitate the destruction of the quantum coherence maintained by the quantum potential by leading to high values of the dissipation parameter in (12).

2.4. Measurement Process and the Finite Range of Nonlocal Quantum Potential Interactions

Throughout the course of measurement, there exists the possibility of a conventional quantum interaction between the sensing component within the experimental setup and the system under examination. This interaction concludes when the measuring apparatus is relocated to a considerable distance from the system. Within the SQHM framework, this relocation is imperative and must surpass specified distances and.

Following this relocation, the measuring apparatus manages the "interaction output." This typically involves a classical, irreversible process, characterized by the time arrow, leading to the determination of the macroscopic measurement result.

Consequently, the phenomenon of decoherence assumes a pivotal role in the measurement process. Decoherence facilitates the establishment of a large-scale classical framework, ensuring authentic quantum isolation between the measuring apparatus and the system, both pre and post the measurement event.

This quantum-isolated state, both at the initial and final stages, holds paramount significance in determining the temporal duration of the measurement and in collecting statistical data through a series of independent repeated measurements.

It is crucial to underscore that, within the confines of the SQHM, merely relocating the measured system to an infinite distance before and after the measurement, as commonly practiced, falls short in guaranteeing the independence of the system and the measuring apparatus if either or is met. Therefore, the existence of a macroscopic classical reality remains indispensable for the execution of the measure process in quantum mechanics.

2.5. Minimum Measurement Uncertainty in Fluctuating Spacetime Background

Any quantum theory aiming to elucidate the evolution of a physical system across various scales, at any order of magnitude, must inherently address the transition from quantum mechanical properties to the emergent classical behavior observed at larger magnitudes. The fundamental disparities between the two descriptions are encapsulated by the minimum uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics, signifying the inherent incompatibility of concurrently measuring conjugated variables, and the finite speed of propagation of interactions and information in local classical relativistic mechanics.

Should a system fully adhere to the "deterministic" conventions of quantum mechanics up to a distance, possibly smaller than, where its subparts lack individual identities, the independent observer, to gain information about the system, needs to maintain a separation distance bigger than both before and after the process.

Should a system fully adhere to the conventional quantum mechanics within a physical length, smaller than , where its subparts lack individual identities, the independent observer, that wants to gain information about the system, needs to maintain a separation distance bigger than both before and after the process.

Therefore, due to the finite speed of propagation of interactions and information, the process cannot be executed in a time frame shorter than

Furthermore, considering the Gaussian noise in (7) with the diffusion coefficient proportional to

, we find that the mean value of energy fluctuation is

for the degree of freedom. As a result, a nonrelativistic (

) scalar structureless particle, with mass m, exhibits an energy variance

of

from which it follows that

It is noteworthy that the product remains constant, as the increase in energy variance with the square root of precisely offsets the corresponding decrease in the minimum acquisition time . This outcome holds true when establishing the uncertainty relations between the position and momentum of a particle with mass m.

If we acquire information about the spatial position of a particle with precision

, we effectively exclude the space beyond this distance from the quantum non-local interaction of the particle, and consequently

the variance

of its relativistic momentum

due to the fluctuations reads

and the uncertainty relation reads

Equating (62) to the uncertainty value, such as

or

It follows that represents the physical length below which quantum entanglement is fully effective, and it signifies the deterministic limit of the SQHM, specifically the realization of quantum mechanics.

As far as it concerns the theoretical minimum uncertainty of quantum mechanics, obtainable from the minimum indeterminacy (59, 62) in the limit of quantum mechanics (and) in the non-relativistic limit (), we have that

With regard to the minimum uncertainty of quantum mechanics, attainable from the minimum indeterminacy (59, 62) in the limit of

(

), in the non-relativistic limit (

), it follows that

and therefore that

That constitutes the minimum uncertainty in quantum mechanics, obtained as the deterministic limit of the SQHM.

It's worth noting that, owing to the finite speed of light, the SQHM extends the uncertainty relations to all conjugate variables of 4D spacetime. In conventional quantum mechanics, deriving the energy-time uncertainty is not possible because the time operator is not defined.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note that in the relativistic limit of quantum mechanics (

and

), influenced by the finite speed of light, the minimum acquisition time of information in the quantum limit is expressed as follows

The result (71) indicates that performing a measurement in a fully deterministic quantum mechanical global system is not feasible, as its duration would be infinite.

Given that non-locality is restricted to domains with physical lengths on the order of , and information about a quantum system cannot be transmitted faster than the speed of light (violating the uncertainty principle otherwise), local realism is established within the coarse-grained macroscopic physics where domains of order of reduce to a point.

The paradox of "spooky action at a distance" is confined to microscopic distances (smaller than ), where quantum mechanics is described in the low-velocity limit, assuming and . This leads to the apparent instantaneous transmission of interaction over a distance.

It is also noteworthy that in the presence of noise, the measure indeterminacy has a relativistic correction since leading to the minimum uncertainty in a quantum system submitted to gravitational background noise ()

It is also noteworthy that in the presence of noise, the measured indeterminacy undergoes a relativistic correction, as expressed by

, resulting in the minimum uncertainty in a quantum system subject to gravitational background noise (

):

and

This can become significant for light particles (with ), but in quantum mechanics, at , the uncertainty relations remain unchanged.

2.6. The Discrete Nature of Spacetime

Within the framework of the SQHM, incorporating the uncertainty on measure in fluctuating quantum system and the maximum attainable velocity of the speed of light such as

it follows that the uncertainty relations

leads to

and, consequently, to

where

is the Compton’s length.

Identity (76) reveals that the maximum concentration of the mass of a body, compatible with the uncertainty principle, is within an elemental volume with a side length equal to half of its Compton wavelength.

This result holds significant implications for black hole (BH) formation. To form a BH, all the mass must be compressed within a sphere of the gravitational radius

that cannot have a radius smaller than the Compton length

, giving rise to the relationship:

which further leads to the condition:

indicating that the BH mass

where

.

This in a vacuum at zero background temperature, If we consider positive temperature as in (57) it follows that

leading to

and, consequently, to

which leads to the condition

that for a BH reads

Result (67) shows that, in the presence of a positive temperature greater than zero, a black hole with Planck mass becomes unstable, requiring additional mass to achieve stability. It is worth noting that this temperature-driven instability could be the mechanism that destabilized pre-big bang black hole [

51], potentially leading to its extrusion beyond the gravitational radius and triggering the big bang.

Result (60) demonstrates that the maximum mass density, constrained by quantum laws—specifically the minimum uncertainty principle—is attained when confined within a sphere whose diameter equals half the Compton wavelength. This implies that,in this case, the repulsive quantum potential becomes infinite and insurmountable. Consequently, within the gravitational radius, the black hole's mass cannot collapse into a singular point; rather, the collapse is halted by quantum forces before reaching a sphere with a radius equal to the Compton wavelength. In equilibrium, the gravitational force and the quantum potential exactly counteract each other.

Considering the hypothesis that spacetime has a discrete structure, it follows that, given the nature of an elemental volume of spacetime—defined as the volume within which mass density is uniformly distributed—the assumption that the Planck length represents the smallest discrete elemental volume is unsustainable. This would make it impossible to compress the mass of large black holes, with masses greater than

, within a sphere whose diameter is half the Compton wavelength, thereby preventing the attainment of gravitational equilibrium [

52,

53]. This suggests that such a discrete description of the universe is incompatible with the gravitational dynamics of black holes.

On the other hand, since existing black holes compress their mass into a core smaller than the Planck length [

52,

53], spacetime discretization would require elemental cells of even smaller volumes. In the analogy of a simulation, the maximum grid density is defined by the size of these elemental cells of spacetime.

Thus, it is important to consider that the assumption that the smallest discrete spacetime distance corresponds to the minimum possible Compton wavelength

—derived from the maximum possible mass/energy density, which is the mass/energy of the universe—provides a criterion to rationalize the universe's mass. This helps explain why the mass of the universe is not higher than its observed value, as it is intrinsically tied to the minimum length of the discrete spacetime element. If the pre-big-bang black hole was generated by an anomalous fluctuation gravitationally confined within an elemental cell of spacetime, its mass content

could not be smaller than that of the universe.

2.6.1. Dynamics of Wavefunction Collapse

The Markov process (7) in the limit of slow kinetics (see Equation (74) below) can be described by the Smolukowski equation for the Markov probability transition function (PTF) [

44]

where the PTF

is the probability that in time interval τ is transferred to point q.

The conservation of the PMD shows that the PTF displaces the PMD according to the rule [

44]

Generally, for the quantum case, Equation (68) cannot be reduced to a Fokker–Planck equation (FPE). The functional dependence of

by

, and by the PTF

, produces non-Gaussian terms [

40].

Nonetheless, if, at initial time,

is stationary (e.g., quantum eigenstate) close to the long-time final stationary distribution

, it is possible to assume that the quantum potential is about constant in time as a Hamilton potential following the approximation

Being in this case the quantum potential independent by the mass density time evolution, the stationary long-time solutions

can be approximately described by the Fokker–Planck equation

where

leading to the final equilibrium of the stationary quantum configuration

In ref. [

40] the stationary states of a harmonic oscillator obeying (72) are shown. The results show that the quantum eigenstates are stable and maintain their shape (with a small change in their variance) when subject to fluctuations.

2.6.2. Evolution of the PMD of Superposition of States Submitted to Stochastic Noise

The quantum evolution of not-stationary state superpositions (not considering fast kinetics and/or jumps (eventually due to external inputs)) involves the integration of Equation (7) in the form

in which fast variables are eliminated.

By utilizing both the Smolukowski Equation (68) and the associated conservation Equation (69) for the PMD

, it is possible to integrate (74) by using its second-order discrete expansion

where

where

has a Gaussian zero mean and unitary variance which probability function

, for

, reads as

where the midpoint approximation

has been introduced and where

and

are the solutions of the deterministic problem:

As shown in ref. [

40], the PTF

can be achieved after successive steps of approximation and reads

and the PMD at the

-th instant reads

leading to the velocity field

Moreover, the continuous limit of the PTF gives

where

.

The resolution of the recursive Expression (86) offers the advantage of being applicable to nonlinear systems that are challenging to handle using conventional approaches [

54,

55,

56,

57].

2.6.3. General Features of Relaxation of Quantum Superposition of States

The classical Brownian process admits the stationary long-time solution

where

, leading to solution [

58]

As far as it concerns in (86) it cannot be expressed in a closed form, unlike (87), because it is contingent on the particular relaxation path the system follows toward the steady state. This path is significantly influenced by the initial conditions, namely the MDD as well as , and, consequently, by the initial time at which the quantum superposition of states is subjected to fluctuations. This means that the output of a measure to an eigenstate depends by the initial instant at which the system plus the measure system perform the measure. Therefore, if we repeat the measure statistically we end with a different output.

In addition, from (75), we can see that depends on the exact sequence of inputs of stochastic noise. This fact becomes more critical in classically chaotic systems since very small differences can lead to relevant divergences of the trajectories in a short time. Therefore, in principle, different stationary configurations (analogues of quantum eigenstates) can be reached whenever starting from identical superposition of states. Therefore, in classically chaotic systems, Born’s rule can also be applied to the measurement of a single quantum state.

Even if , it is worth noting that, to have finite quantum lengths and , necessary to have the quantum-decoupled classical environment (or measuring apparatus), also the nonlinearity of the overall system (system–environment) is necessary.

Quantum decoherence, which leads to the decay of superposition states, is significantly enhanced by the pervasive classical chaotic behavior observed in real systems. In contrast, a perfectly linear universal system would preserve quantum correlations on a global scale and would never allow quantum decoupling between the system and the experimental apparatus performing the measurement. It is important to note that even the decoupling of the system from the environment would be impossible, as quantum systems function as an integrated whole. Therefore, simply assuming the existence of separate systems and environments subtly introduces a classical condition into the nature of the overall supersystem.

Furthermore, since equation (7) is valid only in the leading order approximation of

(i.e., during a slow relaxation process with small amplitude fluctuations) [

40], in cases of large fluctuations occurring over a timescale much longer than the relaxation period of

, transitions may occur to configurations not captured by (86), potentially leading from a stationary eigenstate to a new superposition of states. In this case, relaxation will once again proceed toward another stationary state. The

given by (84) describes the relaxation process occurring during the time interval between two large fluctuations, rather than the system’s evolution toward a statistical mixture. Due to the extended timescales associated with these jumping processes, a system consisting of a significant number of particles (independent subsystems) undergoes gradual relaxation towards a statistical mixture. The statistical distribution of this mixture is determined by the temperature-dependent behavior of the diffusion coefficient.

2.7. EPR Paradox and Pre-Existing Reality in the SQHM

The SQHM (Stochastic Quantum Hamiltonian Mechanics) emphasizes that, despite the well-defined, reversible, and deterministic framework of quantum theory, its foundation remains incomplete. In particular, SQHM highlights that the measurement process is not accounted for within the deterministic "Hamiltonian" framework of standard quantum mechanics. Instead, it is better understood as a phenomenon described by a quantum stochastic approach.

SQHM reveals that standard quantum mechanics is essentially the deterministic, "zero-noise" limit of a broader quantum-stochastic theory, which arises from fluctuations in the spacetime gravitational background. In this context, zero-noise quantum mechanics defines the deterministic evolution of the system's "probabilistic wave." However, SQHM suggests that the term "probabilistic wave" is somewhat misleading, as it reflects the probabilistic nature of the measurement process—something standard quantum mechanics cannot fully explain. Since SQHM provides a framework that accounts for both wavefunction collapse and the measurement process, it proposes "state wave" as a more accurate term.

Moreover, SQHM reinstates the principle of determinism into quantum theory by clarifying that quantum mechanics describes the deterministic evolution of the system's "state wave." The apparent probabilistic outcomes arise from the influence of fluctuating gravitational backgrounds. SQHM also addresses the long-standing question of whether reality exists prior to measurement. While the Copenhagen interpretation suggests that reality only emerges when a measurement forces the system into a stable eigenstate, SQHM proposes that the world naturally self-decays through macroscopic-scale decoherence. In this view, only stable macroscopic eigenstates persist, establishing a lasting reality that exists even before measurement occurs.

With regard to the EPR paradox, SQHM shows that, in a perfectly deterministic (coherent) quantum universe, it is impossible to fully decouple the measuring apparatus from the system and therefore it is impossible to realize a measure within a finite time interval. Such decoupling can only be achieved in a large-scale classical supersystem—a quantum system embedded in 4D spacetime with a fluctuating background. In this scenario, quantum entanglement, driven by quantum potential, extends only over a finite distance. Thus, SQHM restores local relativistic causality in presence of GBN on macroscopic reality.

If the Lennard-Jones interparticle potential produces a sufficiently weak force, leading to a microscopic range of quantum non-local interactions and a large-scale classical phase, photons, as shown in reference [

40], retain their quantum properties at the macroscopic level due to their infinite quantum potential range of action. As a result, photons are the ideal particles for experiments designed to demonstrate the features of quantum entanglement over long distances.

In order to clearly describe the standpoint of the SQHM on this argument, we can analyze the output of two entangled photon experiments traveling in opposite directions in the state

where

and

are vertical and horizontal polarizations, respectively, and

is a constant phase coefficient.

Photons “one” and “two” impact polarizers (Alice) and (Bob) with polarization axes positioned at angles and relative to the horizontal axis, respectively. For our purpose, we can assume .

The probability that photon “two” also passes through Bob’s polarizer is .

As widely held by the majority of the scientific community in quantum mechanics physics, when photon “one” passes through polarizer with its axes at an angle of , the state of photon “two” instantaneously collapses to a linear polarized state at the same angle , resulting in the combined state .

In the context of the SQHM, able to describe the kinetics of the wavefunction collapse, the collapse is not instantaneous, and following the Copenhagen quantum mechanics standpoint, it needs to assert rigorously that the state of photon “two” is not defined before its measurement at the polarizer .

Therefore, after photon “one” passes through polarizer , from the standpoint of SQHM, we have to assume that the combined state is , where the state represents the state of photon “two” in the interaction with the residual quantum potential field generated by photon “one” at polarizer . The spatial extension of the field of the photon two, in the case the photons travel in opposite direction, is the double of that one crossed by the photon one before its adsorption. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the quantum potential is not proportional to the intensity of the field. Instead, it is proportional to its second derivative. Therefore, a minor perturbation in the field with a high frequency at the tail of photon two (during the absorption of photon one) can give rise to a significant quantum potential field .

When the residual part of the two entangled photons also passes through Bob’s polarizer, it makes the transition with probability . The duration of the photon two adsorption (wavefunction decay and measurement) due to its spatial extension, and finite light speed, it is just the time necessary to transfer the information about the measure of photon one to the place of photon two measurement. A possible experiment is proposed in ref. [4019].

Summarizing, the SQHM reveals the following key points:

- i.

The SQHM posits that quantum mechanics represents the deterministic limit of a broader quantum stochastic theory;

- ii.

Classical reality emerges at the macroscopic level, persisting as a preexisting reality before measurement;

- iii.

The measurement process is feasible in a classical macroscopic world, because we can have really quantum decoupled and independent systems, namely the system and the measuring apparatus;

- iv.

Determinism is acknowledged within standard quantum mechanics under the condition of zero GBN;.

- v.

Locality is achieved at the macroscopic scale, where quantum non-local domains condense to punctual domains.

- vi.

Determinism is recovered in quantum mechanics representing the zero-noise limit of the SQHM. The probabilistic nature of quantum measurement is introduced by the GBN.

- vii.

The maximum light speed of the propagation of information and the local relativistic causality align with quantum uncertainty;

- viii.

The SQHM addresses the GBN as playing the role of the hidden variable in the Bohm non-local hidden variable theory: The Bohm theory ascribes the indeterminacy of the measurement process to the unpredictable pilot wave, whereas the Stochastic Quantum Hydrodynamics attributes its probabilistic nature to the fluctuating gravitational background. This background is challenging to determine due to its predominantly early-generation nature during the Big Bang, characterized by the weak force of gravity without electromagnetic interaction. In the context of Santilli's non-local hidden variable approach in IsoRedShift Mechanics, it is possible to demonstrate the direct correspondence between the non-local hidden variable and the GBN. Furthermore, it must be noted that the consequent probabilistic nature of the wavefunction decay, and measure output, is also compounded by the inherently chaotic nature of the classical law of motion and the randomness of the GBN, further contributing to the indeterminacy of measurement outcomes.

2.8. The SQHM in the Context of the Objective-Collapse Theories

Ideally, the SQHM falls into the so-called Objective Collapse Theories [

25,

59,

60,

61]. In collapse theories, the Schrödinger equation is augmented with additional nonlinear and stochastic terms, referred to as spontaneous collapses, that serve to localize the wave function in space. The resulting dynamics ensures that, for microscopic isolated systems, the impact of these new terms is negligible, leading to the recovery of usual quantum properties with only minute deviations.

An inherent amplification mechanism operates to strengthen the collapse in macroscopic systems comprising numerous particles, overpowering the influence of quantum dynamics. Consequently, the wave function for these systems is consistently well-localized in space, behaving practically like a point in motion following Newton's laws.

In this context, collapse models offer a comprehensive depiction of both microscopic and macroscopic systems, circumventing the conceptual challenges linked to measurements in quantum theory. Prominent examples of such theories include: Ghirardi–Rimini–Weber model [

25], Continuous spontaneous localization model [

59] and the Diósi–Penrose model [

60,

61].

While the SQHM aligns well with existing Objective-Collapse models, it introduces an innovative approach that effectively addresses critical aspects within this class of theories. One notable achievement is the resolution of the 'tails' problem by incorporating the quantum potential length of interaction, in addition to the De Broglie length. Beyond this interaction range, the quantum potential cannot maintain coherent Schrödinger quantum behavior specifically of the wavefunction tails.

The SQHM also highlights that there is no need for an external environment, demonstrating that the quantum stochastic behavior responsible for wave-function collapse can be an intrinsic property of the system in a spacetime with fluctuating metrics due to the gravitational background. Furthermore, situated within the framework of relativistic quantum mechanics, which aligns seamlessly with the finite speed of light and information transmission, the SQHM establishes a clear connection between the uncertainty principle and the invariance of light speed.

The theory also derives, within a fluctuating quantum system, the indeterminacy relation between energy and time—an aspect not expressible in conventional quantum mechanics—providing insights into measurement processes that cannot be completed within a finite time interval in a truly quantum global system. Notably, the theory finds support in the confirmation of the Lindemann constant for the melting point of solid lattices and the transition of He4 from fluid to superfluid states. Additionally, it proposes a potential explanation for the measurement of entangled photons through a Earth-Moon-Mars experiment [

40].

3. The Computational Framework of the Universe in Shaping Future States

The discrete spacetime structure that comes from the finite speed of ligth together with the quantum uncertainty (60,67) allows the interpretation of the universe's evolution as the development of a discrete computer simulation.

In this case, the programmer of such universal simulation has to face with the following problems:

- i.

Finite nature of computer resources. One key argument revolves around the inherent challenge of any computer simulation, namely the finite nature of computer resources. The capacity to represent or store information is confined to a specific number of bits. Similarly, the availability of Floating-point Operations Per Second (FLOPS) is limited. Regardless of efforts, achieving a truly "continuous" simulated reality in the mathematical sense becomes unattainable due to these constraints. In a computer-simulated universe, the existence of infinitesimals and infinities is precluded, necessitating quantization, which involves defining discrete cells in spacetime.

- ii.

The speed of light and maximum velocity of information transfer must be finite. Another common issue in computer-simulation arises from the inherent limitation of computing power in terms of the speed of executing calculations. Objects within the simulation cannot surpass a certain speed, as doing so would render the simulation unstable and compromise its coherence. Any propagating process cannot travel at an infinite speed, as such a scenario would require an impractical amount of computational power. Therefore, in a discretized representation, the maximum velocity for any moving object or propagating process must conform to a predefined minimum single-operation calculation time. This simulation analogy aligns with the finite speed of light (c) as a motivating factor.

- iii.

Discretization must be dynamic. The use of fixed-size discrete grids is clearly a huge dispersion of computational resource in spacetime regions where there are no bodies and there is nothing to calculate (so that we can fix there just one big cell saving computational resources). On the one hand, the need to increase the size of the simulation requires lowering the resolution; on the other hand, it is possible to achieve better resolution within smaller domains of the simulation. This dichotomy is already present to those creating vast computerized cosmological simulations [

62]. This problem is attacked by varying the mass quantization grid resolution as a function of the local mass density and other parameters leading to the so-called Automatic Tree Refinement (ATR). The Adaptive Moving Mesh Method, a similar approach [

63,

64] to that of ATR would be to vary the size of the cells of the quantized mass grid locally, as a function of kinetic energy density while at the same time varying the size of the local discrete time-step, which should be kept per-cell as a 4th parameter of space, in order to better distribute the computational power where it's needed the most. By doing so, the grid would result as distorted having different local sizes. In a 4D simulation this effect would also involve the time that be perceived as flowing differently in different parts of the simulation: faster for regions of space where there's more local kinetic energy density, and slower where there's less.

- iv.

In principle, there are two methods for computing the future states of a system. One involves utilizing a classical apparatus composed of conventional computer bits. Unlike Qbits, these classical bits cannot create, maintain, or utilize the superposition of their states, being them classical machines. On the other hand, quantum computation employs a quantum system of Qbits and utilizes the quantum laws (superposition of states evolution) for calculations.

However, the capabilities of the classical and quantum approaches to predict the future state of a system differ. This distinction becomes evident when considering the calculation of the evolution of many-body system. In the classical approach, computer bits must compute the position and interactions of each at every calculation step. This becomes increasingly challenging (and less precise) due to the chaotic nature of classical evolution. In principle, the classical N-body simulations are straightforward as they primarily entail integrating the 6N ordinary differential equations that describe particle motions. However, in practice, the sheer magnitude of particles, N, is often exceptionally large (of order of millions or ten billion like at the Max Planck Society's Supercomputing Centre (Garching, Germany). Moreover, the computational expense becomes prohibitive due to the exponential increase in the number of particle-particle interactions that need to be computed. Consequently, direct integration of the differential equations requires an exponential increase of calculation and data storage resources for large scale simulations.

On the other hand, quantum evolution doesn't require defining the state of each particle at every step. It addresses the evolution of the global wave of superposition of states for all particles. Eventually, when needed or when decoherence is induced or spontaneously occurs, the classical state of each particle at a specific instant is obtained (calculated) through the wavefunction decay. Under this standpoint, “calculated” is equivalent to "measured". This represents a form of optimization sacrificing the knowledge of the classical state at each step, but being satisfied with knowing the classical state of each particle at fewer discrete time instants. This approach allows for a quicker computation of the future state of reality with a lesser use of computer resources. Moreover, since the length of quantum coherence is finite, the group of entangled particles undergoing to the common wavefunction decay, are of smaller finite number, further simplifying the algorithm of the simulation.

The advantage of quantum calculus over classical calculus can be metaphorically demonstrated by addressing the challenge of finding the global minimum. When using classical methods like maximum descent gradient or similar approaches, the pursuit of the global minimum—such as in the determination of prime numbers—results in an exponential increase in the calculation time as the maximum value of the prime numbers rises.

In contrast, employing the quantum method allows us to identify the global minimum in linear or, at least, polynomial time. This can be loosely conceptualized as follows: in the classical case, it's akin to having a ball fall into each valley to find a minimum, and then the values of each individual minimum must be compared with all the minima before determining the overall minimum. The utilization of the quantum method is similar to involve using an infinite number of balls, spanning the entire energy spectrum. Consequently, at each barrier between two minima (thanks to quantum tunneling), some of the balls can explore the next minimum almost simultaneously. This simultaneous exploration (quantum computing) greatly reduces the time required to probe the entire set of minima. Afterward, wavefunction decay enables the measurement (or detection) of the outcome, identifying the minimum at the classical location of each ball.

If we aim to create a simulation on a scale comparable to the vastness of the Universe, we must find a way to address the many-body problem. Currently, solving this problem remains an open challenge in the field of Computer Science. However, Quantum Mechanics appears to be a promising candidate for making the many-body problem manageable. This is achieved through the utilization of the Entanglement process, which encodes coherent particles and their interaction outcomes as a wavefunction. The wavefunction evolves without explicit solving and, when coherence diminishes, the wavefunction collapse leads to calculate (as well determine) the essential classical properties of the system given by the underlying physics at discrete time steps.

This sheds light on the reason why physics properties remain undefined until measured; from the standpoint of the simulation analogy it is a direct consequence of the quantum optimization algorithm, where properties are computed only when necessary. Moreover, the combination of the coherent quantum evolution with the wavefunction collapse has been proven to constitute a Turing-complete computational process, as evidenced by its application in Quantum Computing for performing computations.

An even more intriguing aspect of the possibility that reality can be virtualized as a computer simulation is the existence of an algorithm capable of solving the intractable many-body problem, challenging classical algorithms. Consequently, the entire class of problems characterized by a phenomenological representation, describable by quantum physics, can be rendered tractable through the application of quantum computing. However, it's worth noting that very abstract mathematical problems, such as the 'lattice problem' [

65], may still remain intractable. Currently, the most well-known successful examples of quantum computing include Shor's algorithm [

66] for prime number discovery and Grove's algorithm [

67] for inverting 'black box functions.'

Classical computation categorizes the determination of prime numbers as an NP (non-polynomial) problem, whereas quantum computation classifies it as a P (polynomial) problem with the Shor’s Algorithm. However, not all problems considered NP in classical computation can be reduced to P problems by utilizing quantum computation. This implies that quantum computing may not be universally applicable in simplifying all problems but a certain limited class.

The possibility of acknowledging the universe many-body problem as a computer simulation requires that the NP problem of N-body is tractable. In such a scenario, it becomes theoretically feasible to utilize universe-like particle simulations for solving NP problems by embedding the problem within specific assigned particle behavior. This concept suggests that the laws of physics are not predefined but rather emerge from the structure of the simulation itself, which is purposefully created to address particular issues.

To clarify further: if various instances of universe-like particle simulations were employed to tackle distinct problems, each instance would exhibit different Laws of Physics governing the behavior of its particles. This perspective opens up the opportunity to explore the purpose of the Universe and inquire about the underlying problem it seeks to solve.

In essence, it prompts the question: What is the fundamental problem that the Universe simulation is attempting to address?

3.1. The Meaning of Current Time of Reality and Free Will

At this stage, in order to analyze the universal simulation, producing the evolution with the characteristics of the SQHM in a flat space (at this stage) so that gravity is exclued except for the gravitational background noise that generates the quantum decoherence, let’s consider the local evolution, in a cell of spacetime of order of few De Broglie lengths or quantum coherence lengths

[

40]. After a certain characteristic time, the superposition of states, evolving following the motion equation (7), decays into one of its eigenstates and leads to a stable state that, surviving to fluctuations, constitutes a lasting over time measurable state: we can define it as reality since, for its stability, gives the same result even after repeated measurements. Moreover, due to macroscopic decoherence, the local domains in different locations are quantumly disentangled from each other, so their decay to the stable eigenstate does not always occur simultaneously. Due to the perceived randomness of the GBN, the wave function decay can be assumed to stochastically distribute across local domains of space, leading to a fractal-like classical reality in spacetime, where classical domains do not fully occupy space but result in a globally classical structure.

Furthermore, after an interval of time much larger than the wavefunction decay one, each domain is perturbed by a large fluctuation that is able to let it to jump to a quantum superposition that re-starts to evolve following the quantum law of evolution for a while, before new wavefunction collapse, and so on.

From the standpoint of the SQHM, the universal computation method exploits the quantum evolution for a while and then by the decoherence derives the classical N-body state at certain discrete instants by the wavefunction collapse exatly as a universal quantum computer. Then it goes to the next step by computing the evolutin of the quantum entangled wavefunction evolution, saving up of classically calculating the state of the N-bodies repeatedly, deriving it only when the quantum state decays into the classical one (as in a measure).

Practically, the universe realizes a sort of computational optimization to speed up the derivation of its future state by usitilizing a Qbits-like quantum computation..

3.1.1. The Free Will

Following the pigeonhole principle, which states that any computer that is a subsystem of a larger one cannot handle the same information (thus cannot produce a greater power of calculation in terms of speed and precision) as the larger one, and considering the inevitable information loss due to compression, we can infer that a human-made computer, even utilizing a vast system of Q-bits, cannot be faster and more accurate than the universal quantum computer.

Therefore, the temporal horizon for predicting future states before they occur is necessarily limited within reality. Among the many possible future states, we can infer that it is possible to determine or influence the future outcome within a certain time frame, suggesting that free will is limited. Moreover, since the decision about which reality state we want to realize is not directly connected to preceding events beyond a certain time interval (due to 4D disentanglement), we can also conclude that this decision is not predetermined. This is because the universal simulation progresses in steps of quantum computation, collapsing into classical states. As a result, multiple possible future realities exist, offering a genuine opportunity to choose which one to bring into being

This theoretical framework addresses the problem of time that arises in 4D General Relativity or within the deterministic framework of 4D quantum evolution, where given the initial conditions, 4D spacetime leads to predetermined future states. In this context, time does not flow but merely functions as a 'coordinate' within 4D spacetime, losing the dynamic significance it holds in real life. In the presence of GBN, the predetermination of future states depends on the inherent randomness of the GBN. Even if, in principle, the GBN is pseudorandom, resulting from spacetime evolution since the Big Bang, it appears random to all subsystems of the universe, with an encryption key that remains inaccessible. The detailed definition of all the GBN 'wrinkles' across the universe is beyond the reach of any finite subsystem, as the speed of light is finite and gathering complete information from the entire universe would require a practically infinite time frame.

Therefore, from inside the universal reality simulation, the GBN appears thruly random.

On the other hand, if the simulation makes use of a pseudo-random routine to generate the GBN and it appears truly-random inside the reality, the seed “encoding GBN” is kept outside the simulated reality, and is unreachable to us. In this case we are in front of an instance of a “one-time pad”, effectively equating to deletion, which is proven unbreakable. Therefore, in principle, the simulation could effectively conceal information about the key used to encrypt the GBN noise in a manner that remains unrecoverable.

Furthermore, even if from the inside reality we could have proof of the pseudo-random nature of the GBN, featuring a high level of randomness, the challenge of deciphering the key remains insurmountable [

68] and the encryption key practically irretrievable.

3.2. Nature of Time and Classical Reality: The Universal “Pasta Maker”

Working with a discrete spacetime offers advantages that are already supported by lattice gauge theory [

69]. This theory demonstrates that in such a scenario, the path integral becomes finite-dimensional and can be assessed using stochastic simulation techniques, such as the Monte Carlo method.

In our scenario, the fundamental assumption is that the optimization procedure for universal computation has the capability to generate the evolution of reality. This hypothesis suggests that the universe evolves quantum mechanics in polynomial time, efficiently solving the many-body problem and transitioning it from NP to P. In this context, quantum computers, employing Q-bits with wavefunction decay that both produces and effectively computes the result, utilize a method inherent to the physical reality itself.

From a global spacetime perspective, aside from the collapses in each local domain, it is important to acknowledge a second fluctuation-induced effect. Larger fluctuations taking place over very large time intervals can induce a jump process in the wavefunction configuration, leading to a new generic superposition of states. This prompts a restart of the new local state evolution following quantum laws. As a result, after each local wavefunction decay, the quantum progression towards the realization of the next local classical state of the universe restarts.

At the onset of the subsequent moment, the array of potential quantum states (in terms of superposition) encompasses multiple classical states of realization. Consequently, in the current moment, the future states form a quantum multiverse where each individual classical state is potentially attainable depending on events (such as the chain of wave-function decay processes) occurring beforehand. As the present unfolds, marked by the quantum decoherence process leading to the attainment of a classical state, the past is generated, ultimately resulting in the realization of the singular classical reality: the Universe. In this case, the classical state does not fully occupy spacetime, but it is perceived as doing so at the macroscopic scale.

Moreover, if all possible configurations of the realizable universe exist in the future (which we can only determine and therefore know to a limited extent), the past consists of fixed events (the formed universe) that we are aware of but unable to alter.

In this context, we can metaphorically illustrate spacetime and its irreversible universal evolution as an enormous pasta maker. In this analogy, the future multiverse is represented by a blob of unshaped flour dough, inflated because it contains all possible states. This dough, extending up to the surface of the present, is then pressed into a thin pasta sheet, representing the quantum superposition projective decay to the classical state realizing the universe. From this standpoint, classical bodies are ‘re-calculated’ at each instant and carried into the future, with each subsequent state of our body appearing progressively older as we move forward in time. However, in this process, as our bodies become quantum decoupled from the previous instant, we simultaneously forget and lose perception of the past universe.

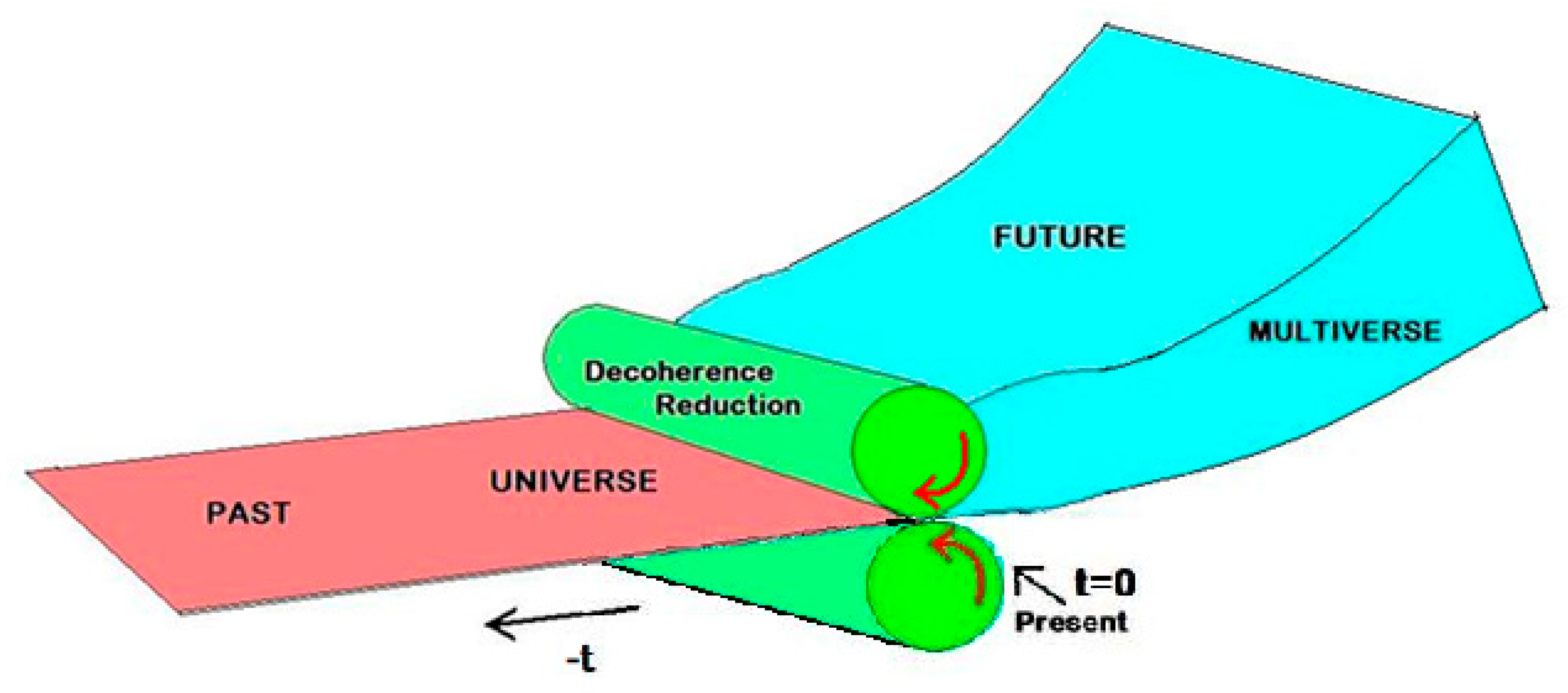

Figure 1.

The Universal “Pasta-Maker”.

Figure 1.

The Universal “Pasta-Maker”.

The 4D surface boundary between the future multiverse and the past universe marks the instant of present time. At this point, the irreversible process of decoherence occurs, entailing the computation or reduction to the present classical state. This specific moment defines the current time of reality, a concept that cannot be precisely located within the framework of relativistic spacetime. The moment in which irreversibility occurs distinguishes it from other points along the time coordinate and generates the experience of everyday real time.

4. Philosophical Breakthrough

The spacetime structure, governed by its laws of physical evolution, enables the modeling of reality as a computer simulation.

The randomness introduced by the GBN makes the simulation fundamentally unpredictable for an internal observer. Even if this observer uses the same algorithm as the simulation to predict future states, the lack of access to the same noise source quickly causes its predictions to diverge. This is because each fluctuation has a significant impact on the wavefunction's decay (see section 2.6.2-3). In other words, for the internal observer, the future is effectively "encrypted" by this noise.

If the noise driving the evolution of the simulation is pseudo-random but sufficiently unpredictable, only someone with knowledge of the seed would be able to accurately forecast the future or reverse the arrow of time. Even though pseudo-random noise can, in theory, be unraveled, the task of deriving the encryption key may be practically intractable. Therefore, with the presence of GBN, the outcome of the computation becomes "encrypted" by the high level of the randomness of this noise.

From this perspective, Einstein’s famous quote, "God does not play dice with the universe," takes on new meaning. Here, it suggests that the programmer of the universal simulation does not engage in randomness because, for he, everything is predetermined. However, from within our reality, we cannot access the seed of this noise, and thus it appears genuinely random to us.

Moreover, the laws of physics are not fixed or predetermined but rather the result of the settings of the simulation, which is designed to solve specific problems. For example, if we create a computer simulation of airplanes flying in the air, and we derive the behavior we observe—where the airplane stays in the air due to pressure on the wings—we derive the laws of gas aerodynamics. Similarly, if we simulate ships sailing, we observe and derive the laws of fluid dynamics. In the same way, the observed laws of reality are consequences of the purpose for which the universal simulation was created.

As discussed in § 3., if the aim of the simulation is to develop a physics that generates organized living structures through evolution—improving organization and efficiency—then the free will we exercise is simply the universe’s method of solving such a problem of "achieving the best organized and efficient possible future state."

From the programmer’s viewpoint, the simulation is progressing towards its intended solution through the method designed to this end. Inside the simulation, this manifests itself through a behavior we perceive as genuine free will.

4.1. Extending Free Will

At this point, a question arises: although we fortunately lack the omnipotent power to completely determine the future at will, and possess only free will limited to the near present, is scientific knowledge about the universe's evolutionary processes useful, and can it yield positive outcomes?

Although we cannot predict the ultimate outcome of our decisions beyond a certain point in time, it is feasible to develop methods that enhance the likelihood of achieving our desired results in the distant future. This forms the basis of the discipline of 'best decision-making.' It's important to highlight that having the most accurate information about the current state extends our ability to forecast future states. Furthermore, the farther away the realization of our desired outcome is, the easier it becomes to adjust our actions to attain it. This concept can be thought of as a preventive methodology. By combining information gathering and preventive methodology, we can optimize the likelihood of achieving our objectives and, consequently, expanding our free will.

Additionally, to streamline the evaluation process of 'what to do,' in addition to the rational-mathematical calculations that dynamically exatly e detailed reconstruct the pathway to our final state, we can focus solely on the probability of a certain future state configuration being realized, adopting a faster evaluation (a sort of Monte Carlo approach). This allows us to potentially identify the best sequence of events to achieve our objective. States beyond the time horizon in a realistic context can be accessed through a multi-step tree pathway. A practical example of this approach is the widely recognized cardiopulmonary resuscitation procedure [

70,

71]. In this procedure, even though the early assurance of the patient's rescue may not be guaranteed, it is possible to identify a sequence of actions that maximizes the probability of saving their life.