Introduction

The current theory of gravity was established over a hundred years ago as part of Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (1915) but it does not represent a full explanation of the cause of gravity or its effects. This paper presents a new theory on the subject and is presented in three parts. In the first part, some background is given on the historical development of ideas regarding the nature of gravity, leading to the established theory that a specific type of distortion of space-time around an object causes it to attract other objects. There is also a description of the fundamental properties of space-time, all of which are relevant to gravity. The second part examines some shortcomings in the ETG. In the third part an alternative theory is put forward, suggesting that a different form of distortion of space-time is the cause of both gravity and its effects.

Definitions

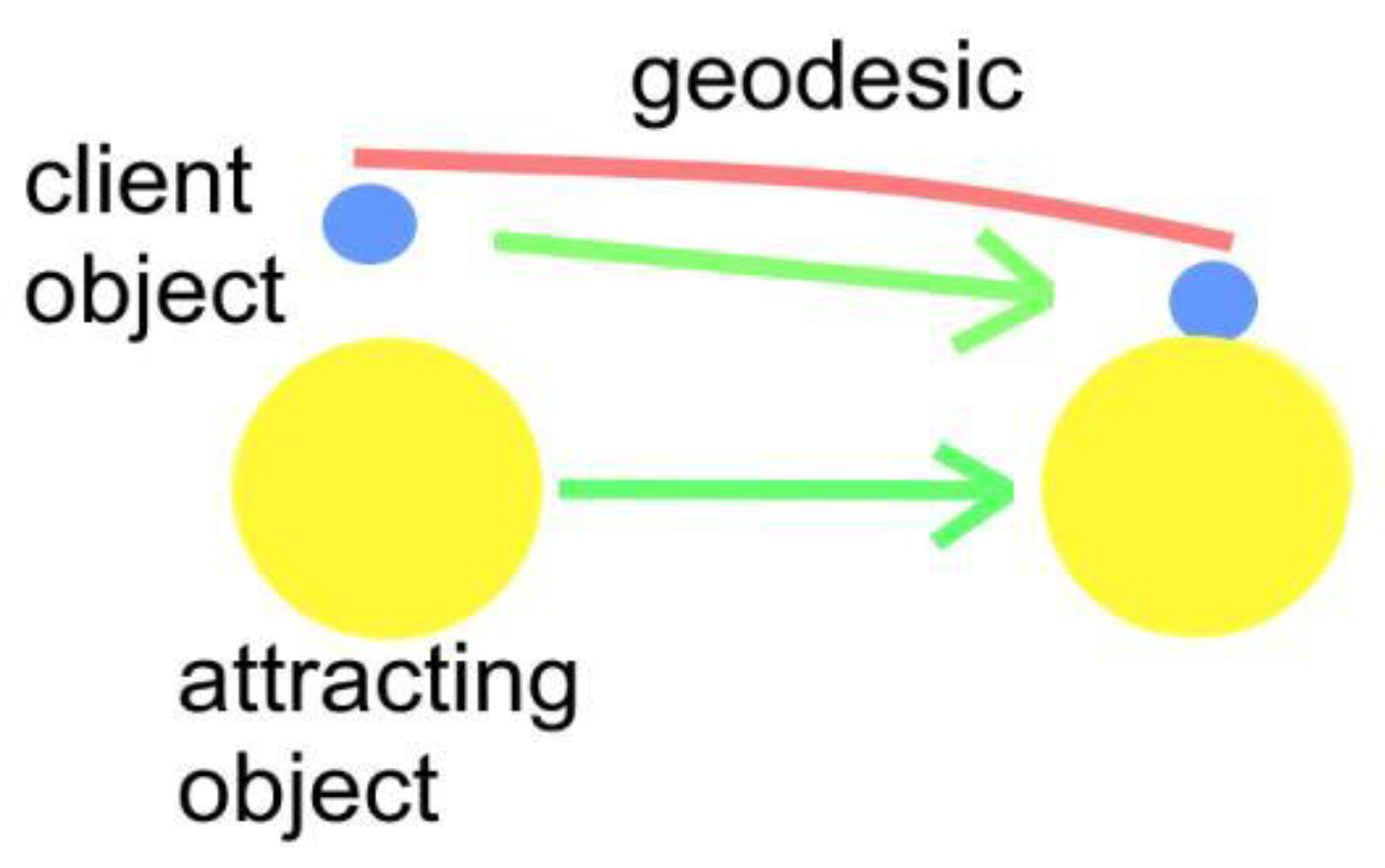

The term attracting object refers to the object that is exerting a gravitational pull on another object, with the latter referred to as the client object.

The term gravitational field is used to denote an area within which an attracting object exerts gravitational pull over a client object.

Early History

Since ancient times there has been speculation, often contradictory, on the cause of gravity. Many theories were of a magical, non-scientific nature. For example, Aristotle (fourth century BCE) believed that solid objects, such as metal or stone, fall towards Earth as a result of them being made of earthly matter. Aristotle also believed that objects fall at a constant speed relative to their weight. In contrast, Plutarch (first century CE) correctly stated that other bodies, not just Earth, had their own gravity. It was only many centuries later that a commonly accepted scientific theory on the nature of gravity was established.

Galileo

In the late 16th century Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) conducted tests that measured the speed at intervals of a ball rolling down a slope. Through these tests he was able to calculate with reasonable accuracy an object’s rate of acceleration due to gravity. Galileo also suggested that all objects, regardless of mass, size and shape, fall at the same speed when air resistance is not a factor. The common speed of falling objects in an environment free of air resistance was demonstrated on the Moon in 1971 when astronaut David Scott dropped a hammer and a feather, with both objects landing on the surface at the same time.

Isaac Newton

Newton (1687) described gravity as a universal force and stated that "the forces which keep the planets in their orbs must be reciprocally as the squares of their distances from the centres about which they revolve." This statement was later summarised in Newton’s inverse-square law of gravity:

In this formula, F represents the force of gravity, m1 and m2 are the respective masses of the two objects, d is the distance between the centres of the two objects, and G is Newton’s gravitational constant:

Newton’s law was used nearly two hundred years later when the planet Neptune was discovered by estimating its position using the equation.

Henry Cavendish

In 1797-1798 Henry Cavendish (1731–1810) conducted a high precision experiment, later named the Cavendish experiment, which confirmed Newton’s earlier theory that all objects have their own gravity. During this experiment Cavendish also calculated with good accuracy the mass of Earth.

Einstein and Relativity

Before the 20th century, scientists had succeeded in accurately calculating the power of Earth’s gravity as well as determining its key characteristics, such as all objects having their own gravity, common speed and rate of acceleration when air resistance is not a factor, as well as the maximum speed of a falling object. However, there was no science-based theory on the cause of gravity until the early 20th century. The breakthrough came as part of the General Theory of Relativity (1915) written by Albert Einstein. Einstein explains the falling of a stone to the ground as follows:

"The effects of gravitation also are regarded in an analogous manner. The action of the earth on the stone takes place indirectly. The earth produces in its surrounding a gravitational field, which acts on the stone and produces its motion of fall."

This has been the established theory of gravity for more than a century, attributing it to the movement of an object along a warping of space-time, however it does not represent a full explanation of the cause of gravity or its effects, as will be demonstrated further on.

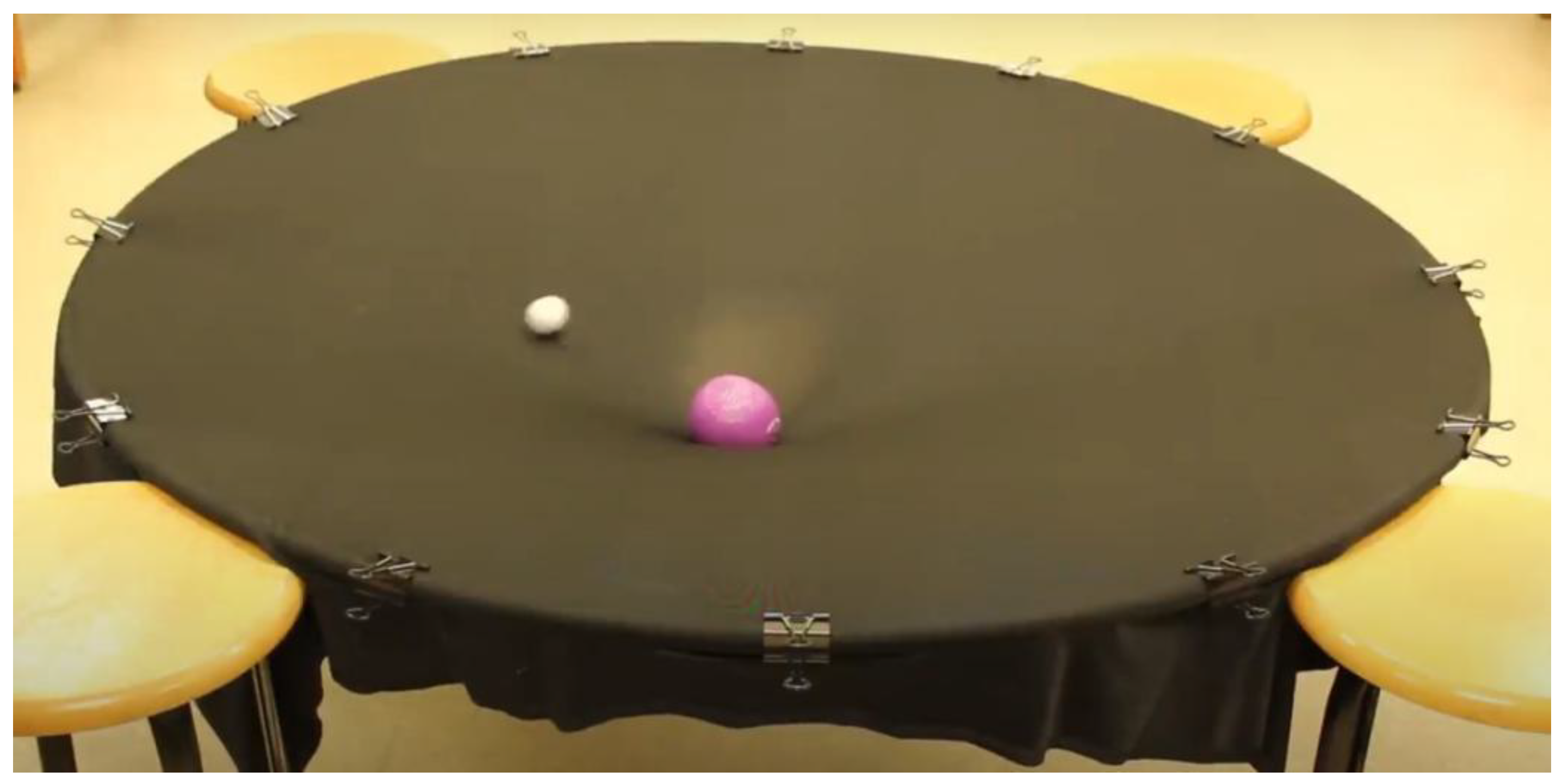

Practical Demonstration of Gravity

A helpful practical demonstration of the concept of a warp in space-time causing gravity, one which is occasionally presented in science classes, involves placing an object in the middle of a piece of taut material such as spandex, causing it to dip in the centre. A ball is then released on the edge of the spandex and rolls towards the centre, possibly in a spiral shaped path. The dip in the centre of the material represents a distortion of space-time and the ball represents an object being pulled by the gravity of the larger object which is causing the dip in the centre. Although this is a helpful way of showing how one object orbits another one, it inevitably cannot show how an object falling vertically to the centre from any direction would move along a warping in space-time. This paper focuses primarily on objects falling vertically towards other objects as a result of gravity rather than on one object orbiting another one.

Figure 1 shows an example of this demonstration.

Properties of Space-Time

Space-time has a number of properties that affect the way in which gravity works. These relate to its physical characteristics and the mutual effects when interacting with matter.

Universal Presence

As already stated, space-time fills empty space throughout the universe. This includes not only the space outside all matter but also an atom’s empty space outside its nucleus.

Extreme Weakness

Space-time is extremely weak when pushed against from a stable surface even with very limited force. For example, when an ant picks up a leaf it is overcoming the power of Earth’s gravity. Despite its weakness, gravity has the power to control matter across very long distances and can affect the movement of remote objects, such as stars and planets, regardless of their mass.

Displacement and Distortion by Matter

Space-time is displaced by any matter or energy present within it, in the same way that a rock on the seabed displaces an equivalent volume of seawater. It is also distorted by the movement or collision of matter, for example the creation of a gravitational wave when two objects collide. Any displacement or distortion of space-time is dependent upon the size, shape, mass, density, and relative speed of movement of any objects that are moving or colliding.

Movement and Distortion of Matter

Space-time causes movement and distortion of matter. Examples of this are the effects of gravity, including the creation of black holes, and the effects of gravitational waves.

Gravitational Waves

A gravitational wave is a ripple in space-time that is generated by the movement of an object or when objects collide. The combined mass and relative speed of the colliding objects determine the magnitude of the wave. A gravitational wave may cause the movement or distortion of remote objects, possibly trillions of miles away. This is similar in effect to a stone being dropped into still water, creating a ripple which moves a leaf floating on the surface some distance away. Gravitational waves were originally proposed in the 19th century but the first direct detection of a wave took place on 14th September, 2015, simultaneously by two American Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatories. This wave was caused by the collision of two black holes an estimated 1,300 million years ago. Moving at the speed of light, the wave took hundreds of millions of years to reach Earth and for a split second caused extremely small distortion to all matter on Earth.

Self-Correction and Levelling Out

Space-time has a three-dimensional elasticity which causes it to level itself out after it has been displaced or distorted by matter in the same way that disturbed water finds its level. The presence of matter affects the levelling out process. It is this self-correcting property of space-time which causes objects to move towards other objects.

Shortcomings in the ETG

According to the ETG, falling client objects move towards an attracting object along a curved warp in space-time, known as a geodesic, which is generated by the attracting object. The movement of a client object along a geodesic causes its linear movement through three-dimensional space until it lands on the attracting object or is stopped by other matter (

Figure 2).

A popular analogy involves two people travelling from different points on the equator in a straight line across Earth’s curved surface (a land geodesic) and meeting at the North Pole. Several of the shortcomings in the ETG, including the concept of geodesics, are covered in the following sections. All of the scenarios described assume an environment free of air resistance.

Differences Between Land Geodesics and Space-Time Geodesics

Analogies are a helpful way of relating a concept to something familiar but they rarely offer a perfect comparison. There are some notable differences between the land geodesics in the analogy just described and the space-time geodesics suggested in the ETG:

In the analogy, the two people move along land geodesics of similar length and curved shape. In contrast, the ETG involves a client object moving along a curved space-time geodesic while the attracting object moves on a more direct trajectory through space-time.

The land geodesics in the analogy are stationary relative to Earth. A space-time geodesic, as described in the ETG, would function in one of two possible ways, both of which are different to a land geodesic. The first possibility is that the client object moves along a space-time geodesic which is part of a snapshot of the warping of space-time around the attracting object the moment the client object began its descent. This is highly implausible and would mean that the space-time geodesic is not stationary relative to the attracting object which is moving through space-time and might be rotating on an axis. The client object would therefore be moving along an obsolete geodesic which relates to the attracting object’s position in space-time the instant the client object began its descent.

The second possibility is that the attracting object is constantly re-creating the geodesics surrounding it and the client object moves along a series of geodesics as each one is created. This is also different to the analogy of the two static land geodesics and would require a mechanism to ensure that a client object moves along the correct series of possibly trillions of geodesics. These geodesics would not necessarily be in alignment with each other if the attracting object is moving on an unpredictable trajectory through space-time and rotating on an axis.

The two travellers specifically select two land geodesics that meet at the North Pole. Most land geodesics do not cross the North Pole and not all space-time geodesics around an attracting object would be guaranteed to point in a forwards direction relative to the attracting object’s movement through space-time.

It is highly unlikely that the two people would reach the North Pole at exactly the same time. In contrast, the ETG involves an object travelling along one or more space-time geodesics then landing at exactly the right moment on the surface of the attracting object directly below the starting point of its descent. Perfect timing needs to occur for all falling objects anywhere in the universe when they are descending towards an attracting object, whatever their respective speeds and relative direction of movement through space-time. This would include attracting objects that rotate on an axis with varying surface speed and at any angle of tilt relative to its movement.

Einstein's Field Equations

Einstein's field equations describe how matter or energy warps space-time at the point of contact between them. Due to their length and detail, they are often presented in summarised form:

The expression to the right of the equals sign multiplies a constant value by the variable value and represents the pressure exerted on space-time by a specific area of matter or energy. The expression to the left represents the curvature of one specific area of space-time caused by the pressure described on the right side.

The field equations enable individual solutions to be calculated but they are non-linear and it is not always possible to derive an exact solution without using simplification, approximations, symmetry or small deviations from flat space-time. Solutions to date often involve either symmetrical objects (the Schwarzschild solution and the Kerr solution), a weak gravitational field or a vacuum absent of matter. The field equations do not work with the singularity inside a black hole, the presence of multiple massive bodies or at the quantum level. They also do not take into account the effects of a gravitational wave on an area of empty space-time. The equations are not proof of a specific theory of gravity or proof that a potentially infinite number of perfectly shaped geodesics is generated by every object in the universe trillions of times a second.

The Geodesic Equation Used in General Relativity

The geodesic equation describes how matter and energy move through space-time along curved geodesics:

The equation serves a very useful purpose for describing how a falling object would move through space-time along a geodesic but this paper describes an alternative theory of gravity that does not involve geodesics.

Assumption That All Geodesics Move an Object in the Correct Direction

The ETG assumes that all objects, regardless of mass and shape, generate geodesics which are perfectly formed to cause movement of a falling object in the correct direction towards the surface of an attracting object. For example, a pyramid- shaped object with its wide base moving forwards into space-time would create the same shaped geodesics as it would create if moving into space-time with its pointed end forward.

Creation of Accurate Geodesics

The ETG does not include a mechanism that would ensure that geodesics originating at any altitude always terminate at a specific point on the attracting object’s surface directly below the point where the geodesic originated. At the instant of a geodesic’s creation, the precise future location that an attracting object will occupy further on in space-time depends on factors such as its speed and direction of movement through space-time, the surface speed of any rotation around an axis, and the angle of tilt relative to its direction of movement.

Potentially Infinite Number of Geodesics and Their Mutual Distortion

When a client object is dropped from any height along an invisible vertical line originating at the surface of an attracting object, it lands on the surface at the origin of the line irrespective of the altitude from which it was dropped. This precision would require trillions if not infinite uniquely shaped and non-overlapping geodesics. Each of these geodesics would originate at a unique altitude along the invisible vertical line and would terminate at the same point on the surface of the attracting object but at different points in space-time. If, instead of individual geodesics, all client objects that begin their descent directly above the same point on the surface then move along one shared geodesic, it would be impossible to impose a maximum speed on these falling objects.

Gravity has at least atom width precision, therefore every square inch of an object’s surface would contain billions of invisible vertical lines, each one the originating point of trillions of geodesics. This would cause widespread mutual distortion of geodesics originating from different vertical lines but pointing in a similar direction through space-time. The field equations do not take into account the existing warping of space-time by previously created geodesics.

Frequency of Geodesic Creation

Many planets rotate on an axis at varying surface speeds and move through space-time in a solar orbit, the solar system possibly in orbit within its galaxy. The galaxy itself is moving through space-time at high speed and may also be orbiting within a galaxy cluster. Therefore, the geodesics surrounding an object would very quickly lose synchronisation with it and stationary client objects resting on an attracting object would not be held in place. Re-creation of the geodesics would be necessary many trillions of times a second. The most recently created geodesics would clash with any expired ones, resulting in distortion. As previously stated, if a client object moved along a series of geodesics in order to ensure an accurate surface landing, this movement would need to be controlled by a separate mechanism. In this scenario, the newest geodesics would not necessarily be in alignment with previous expired ones along which an object had been moving, since movement through space-time can be non-linear.

The ETG and the field equations do not describe how every object in the universe creates trillions of geodesics at the necessary time frequency in order to remain synchronised with the attracting object’s speed and direction of movement through space-time and, if rotating around an axis, any varying surface speed.

Varying Distortion of Space-Time Around the Surface of a Moving Object

As an object moves through space-time, its leading (front) side causes distortion to the space-time into which it is moving. This distortion is very different to the wake turbulence of space-time at the back of the object. The distortion on the other sides of the object is different to that at the front or back. This varying distortion is similar to the way that a speeding car affects the air around it. The field equations use the degree of pressure from matter or energy on a specific point in space-time to calculate its curvature but solutions to the equations assume uniform density of space-time around an object. The significant variation in the warping of space-time around an object would eliminate any certainty of the creation of uniformly shaped geodesics around an object of uniform mass.

Speed of Falling Client Objects Moving Through Space-Time

If falling objects move through space-time at a speed that is less than or equal to the speed of the attracting object, a falling object at the wake (rear) end of an attracting object, relative to its movement through space-time, would never catch up with the attracting object. Alternatively, if falling objects move through space-time at a speed greater than the attracting object’s speed, then falling objects at the front of the attracting object would take longer to land on its surface than falling objects at the wake end. A mechanism would therefore be required in order to control every falling object’s speed but no such mechanism is described in the ETG.

Common Rate of Acceleration of Falling Objects

As previously stated, there is no certainty that every object in the universe generates the necessary geodesics that, according to the ETG, guide descending objects towards the surface of the attracting object. Without these geodesics, the ETG has no alternative mechanism that would impose a common rate of acceleration on falling objects in the same gravity. Moreover, any such mechanism would involve action at a distance.

Maximum Speed of Falling Objects

The ETG does not explain how a common maximum speed of descent is imposed on falling objects in the same gravity. The altitude at which this speed is imposed is related to the altitude from which an object began its descent. Even if a maximum speed is imposed on a client object moving along a geodesic there is, as previously stated, no guarantee that geodesics exist around every object. A separate unspecified mechanism that imposes a maximum speed of descent would therefore be required, again involving action at a distance.

Alternative Theory of Gravity

An alternative theory of gravity is now presented. It consists of two features:

The compression of space-time outwards from the centre of mass of an attracting object to create the gravitational field.

The two interconnected processes forming the movement mechanism that is triggered by the presence of a client object within an attracting object’s gravitational field.

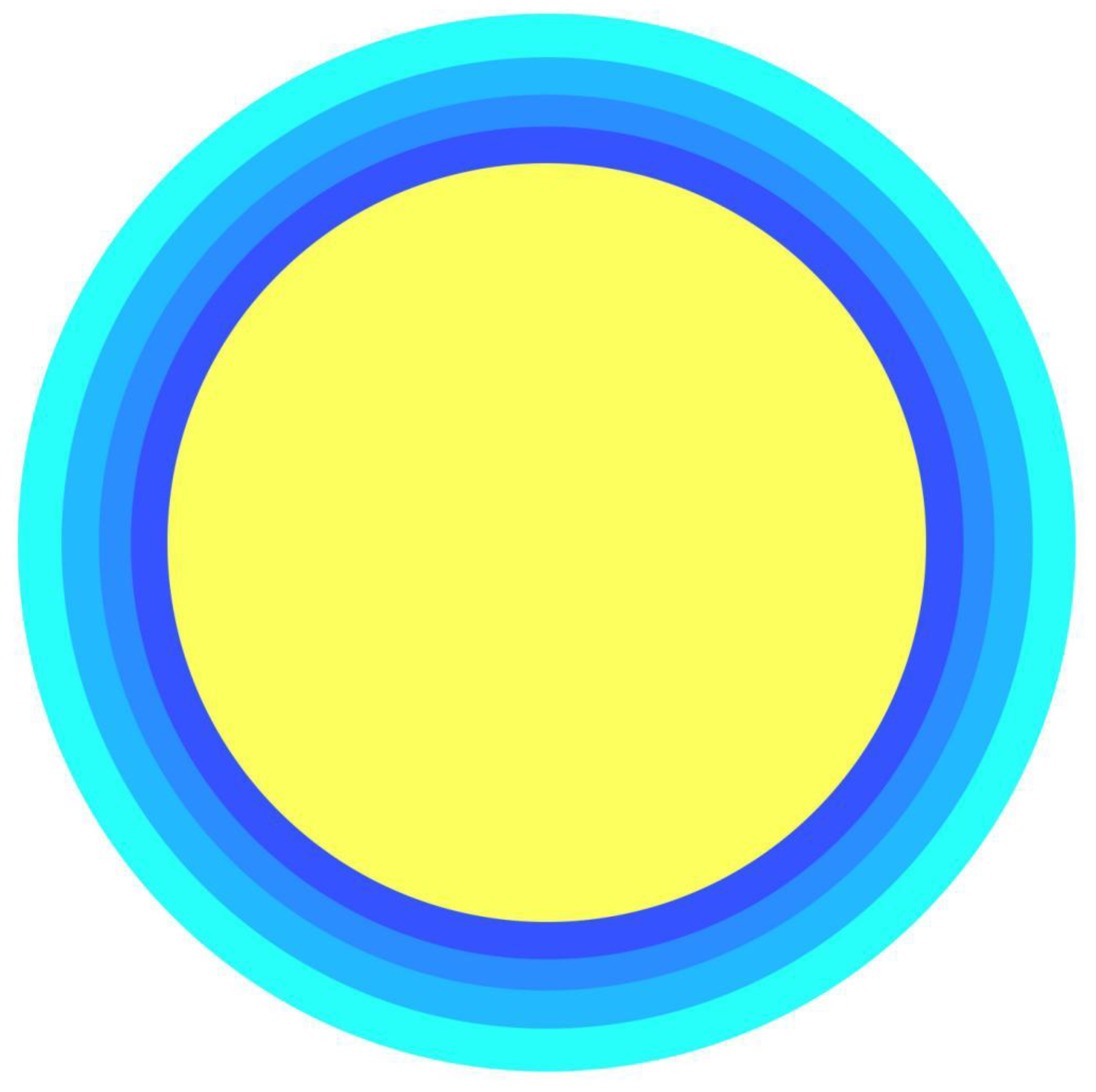

Compression of Space-Time Outwards from an Object’s Centre of Mass

The nucleus of an atom displaces the space-time from the area it occupies, compressing it outwards in all directions. This compression reduces exponentially as distance from the nucleus increases. All objects made up of atoms cause compression of space-time from the centre of mass of the object outwards. The degree and form of compression is determined by an object’s mass, density, size and shape. The density of an object’s matter varies, therefore the strongest gravitational pull may be closer to the centre than it is to the surface. This outwards compression of space-time around an object creates a gravitational field, but it is not the mechanism that moves one object towards another one.

Figure 3 shows space-time compressed outwards around the outside of a hypothetical perfect sphere of matter of uniform density.

Real matter is never perfectly formed, therefore gravity varies around the surface of an object. For simplicity,

Figure 3 does not show the compressed space-time inside the object. The compression is shown in four colours where darker represents greater compression. The shading is for illustration purposes only, since space-time is continuous and has no separate sections based on degrees of compression. This is similar to the use of different colours on a thermal map.

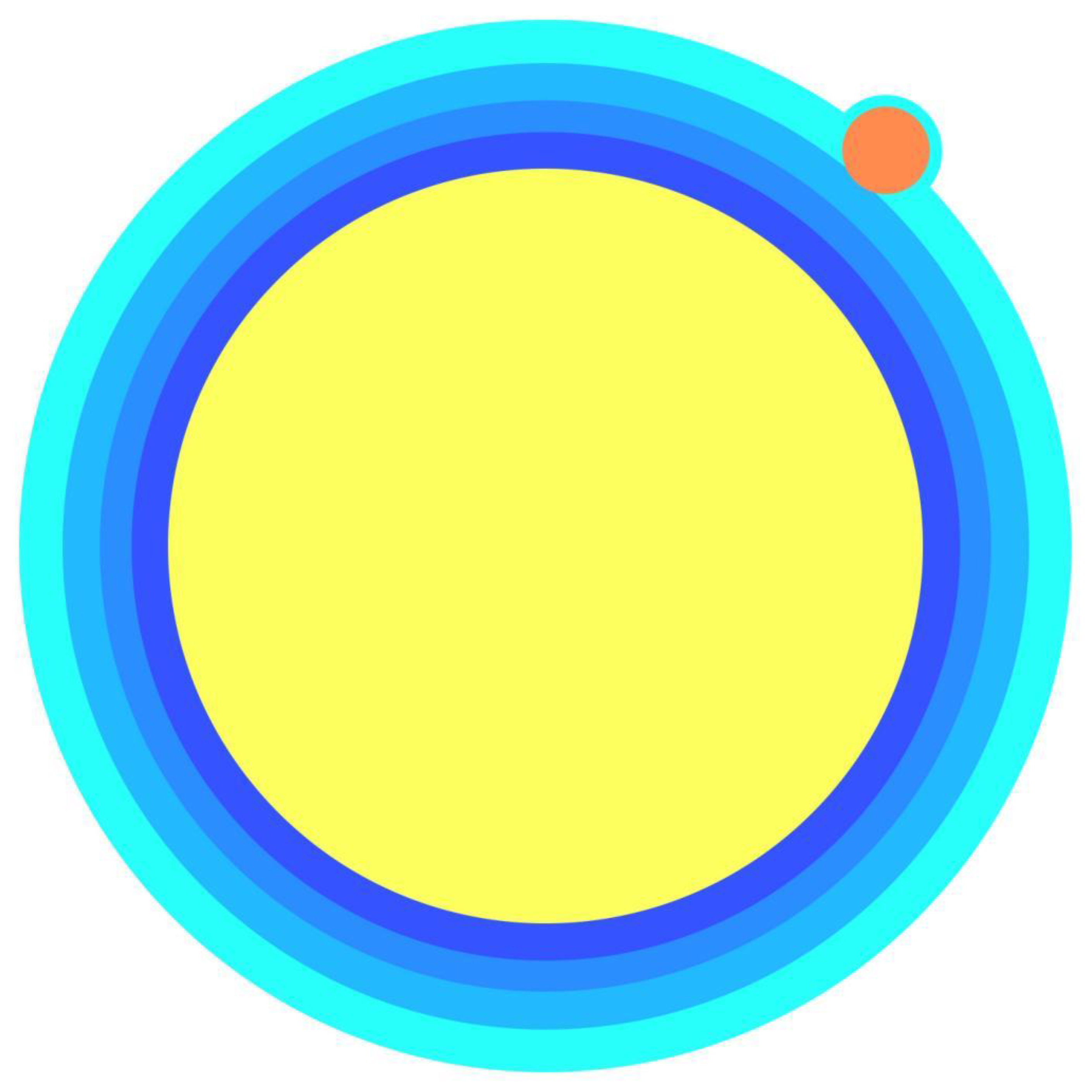

Wraparound Process

When a client object (object C) comes within the gravitational field of an attracting object (object A), some of the space-time that is compressed outwards around object A is displaced by the presence of object C. The displaced space-time takes the path of least resistance, resulting in it wrapping itself around object C on the side further away from object A, due to the space-time between objects A and C being under greater compression than the space-time on the far side of object C, as in

Figure 4.

Levelling Out Process

The levelling out process occurs when the space-time that has wrapped around a client object finds its level. The new level is never perfectly even since it is dependent upon the size, shape, mass and density of any matter present. This process is similar to the way that disturbed water finds its level. As space-time levels itself out it moves the client object towards the attracting object, provided there are no obstacles present. Once one area of space-time has levelled itself out behind object C, thereby moving it closer to object A, another area of space-time wraps around object C, as shown in

Figure 5.

This is the process that causes movement due to gravity. It also explains why objects fall vertically in an environment free of resistance. Wrap around and levelling out continue until object C cannot move any closer to object A, as shown in

Figure 6.

The concept of an area of space-time is used for illustration purposes only, just as an ocean may be divided into arbitrary named areas on a map despite it being one continuous body of water. In addition, many parts of a client object are simultaneously subjected to the wraparound and levelling out processes since space-time concurrently wraps around the nuclei of each atom.

Simultaneous Wrapping Around all Nuclei

It takes no longer for space-time to wrap around the nuclei of a million atoms than it does to wrap around the nucleus of one atom, since these are independent concurrent processes. This simultaneous wraparound process is the reason that all objects fall at the same speed when in the same gravity and air resistance is not a factor.

Acceleration of the Wraparound Process

It takes longer for space-time to wrap around a stationary object than it does to wrap around an object that is already moving in the direction towards which space-time is pushing it during the levelling out process. As a falling object’s speed increases, the wraparound and levelling out processes speed up, further increasing the speed of the falling object. It is this process that causes acceleration of a falling object.

Maximum Speed of Wraparound and Levelling Out Processes

There is a finite speed at which space-time can wrap around the nucleus of an atom and then level itself out, therefore a falling object has a maximum speed of descent. This maximum speed exists for all attracting objects but it varies depending on the gravitational power involved.

Einstein’s Equivalence Principle

This alternative theory is consistent with Einstein’s equivalence principle which states that an object’s gravity can be reproduced on a spacecraft in near zero gravity by accelerating at a rate appropriate for the object’s gravity. When a client object is on the surface of an attracting object, it is due to the downwards pressure from the compressed space-time above the object. Earth’s gravity can be duplicated on a remote spacecraft in very low gravity due to minimal compression of space-time. If the spacecraft accelerates, the space-time into which it is moving becomes increasingly compressed. As long as the degree of compression of space-time matches its compression at Earth’s surface and the correct acceleration is applied to maintain this degree of compression, the craft simulates Earth’s gravity. It is sometimes stated that a remote spacecraft accelerating at 9.8m per second squared would simulate Earth’s gravity, but it would actually require at least ten times this rate of acceleration. This is due to the much lower level of compression of the space-time into which the craft is accelerating.

Simulated Zero Gravity Plane Flights

A steeply falling plane creates an environment that simulates zero gravity. This is due to the plane falling at a speed that is faster than the space-time above it is levelling itself out. In addition, there is gravitational lift caused by the downwards compression of space-time below the plane. While the effects are the same as being in remote space in very low gravity, the two situations are very different.

Client Objects in Orbit

A client object is in orbit when the force generated by its remote movement around an attracting object compresses the space-time at this distance from the attracting object. This compression is sufficient to maintain the client object’s orbit while the force exerted by the object’s movement is not strong enough to break through the compressed space-time. This can be compared to someone riding a motorbike around the inside wall of a large cylinder at a speed that maintains the bike’s momentum without breaking through the wall. If an orbiting client object increased its speed to escape speed, it would break through the compressed space-time and move away from the attracting object and out of orbit. This technique is used to sling shot a spacecraft to a higher speed.

Einstein's Field Equations and the Geodesic Equation

Einstein's field equations and the geodesic equation relate to another theory of gravity involving a different form of space-time curvature (geodesics), with client objects moving through space-time along these geodesics. A modified version of the field equations could apply to this alternative theory of gravity but the geodesic equation is specific to the ETG.

Black Holes and the Schwarzschild Radius

This alternative theory is fully consistent with the existence of black holes. A black hole is caused by the mass of an object being so densely packed that the object’s radius is below a value specific to its mass, i.e., its Schwarzschild radius. This causes outwards compression of space-time at such a density that the object’s gravity imposes an escape speed above the speed of light, preventing even light from escaping.

Using an Accelerometer to Prove that Gravity Exerts Downward Pressure

An accelerometer is a device containing three internal sensors that detect movement along the x, y and z axes of three-dimensional space. The sensors compress or stretch when external pressure causes them to move relative to the body of the accelerometer. Readings for their respective axes are displayed in metres per second squared and each reading is positive or negative depending on the direction of the relevant sensor’s movement. All three sensors react to the accelerometer being moved by a secondary object such as a person’s hand. Various mobile phone accelerometer apps are available for testing of acceleration readings.

Testing Gravity Using a Stationary Accelerometer

An upright and stationary accelerometer on a table top displays an x axis acceleration of approximately 9.8 metres per second squared. It is no coincidence that this is the rate of acceleration of a falling object, since the reading is caused by gravity, i.e. compressed space-time, pushing downwards on the x axis sensor. The acceleration is not related to any outwards pressure from below Earth’s surface, even though this is present in some form. If outward pressure from below the ground were the cause of the reading then pushing downwards on the accelerometer while it is stationary on a tabletop would increase the reading and placing the accelerometer on an object that is floating on water would reduce the reading. In fact, neither of these has any effect. Upwards pressure against the bottom of a stationary accelerometer does not cause any of the internal sensors to move relative to the body of the accelerometer. A positive x axis reading is also obtained by holding an accelerometer upright and lifting it upwards, causing downwards pressure on the x axis sensor.

An Accelerometer in Free Fall

When an accelerometer is in free fall it displays zero readings due to the three internal sensors remaining stationary relative to the body of the accelerometer. This is occasionally misinterpreted as proof that gravity is caused by an upwards pressure from below Earth’s surface. A comparable scenario would be to attach an object to weighing scales and then drop them from a height. While in free fall, the scales would display a zero reading despite the weight of the attached object.

Conclusion

The theory described in this paper represents a full explanation of both the cause and the effects of gravity, including the common speed, rate of acceleration and maximum speed of falling objects; all objects having their own gravity; gravitational power being directly linked to the mass of an object; gravity decreasing with distance; Einstein’s equivalence principle; objects in orbit. It demonstrates that it is the flexible, self-correcting property of space-time that causes attraction between objects. This is the fundamental difference with the established theory of gravity, which involves a highly complex warping of space-time and an inconsistent mechanism which moves a client object along these warps.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Einstein, Albert. 1915. The Gravitational Field. In: General Relativity.

- Newton, Isaac. 1687; Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. [Google Scholar]

- University of Toledo. 2016. Spandex Gravity Well. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHySqQtb-rk (Last accessed 11th September 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).