Submitted:

17 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

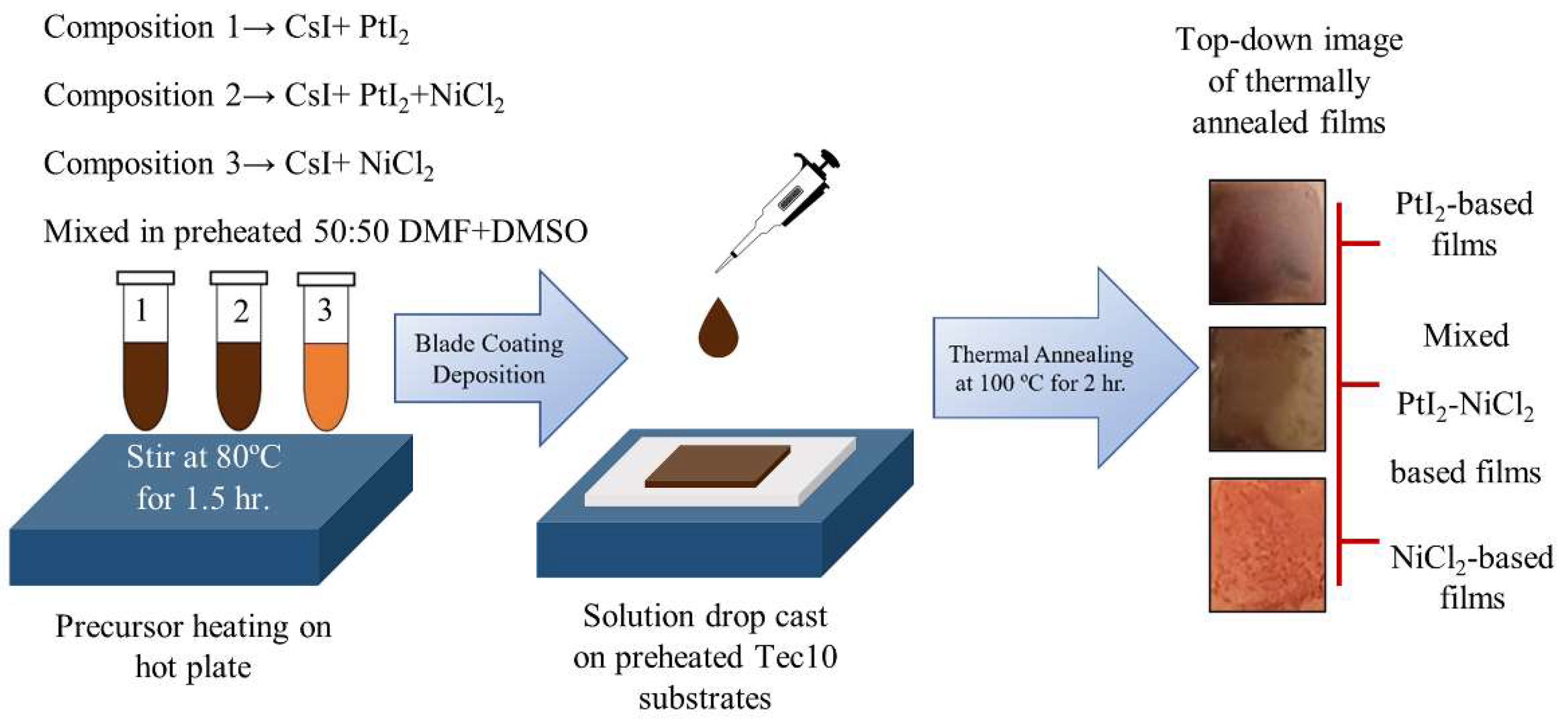

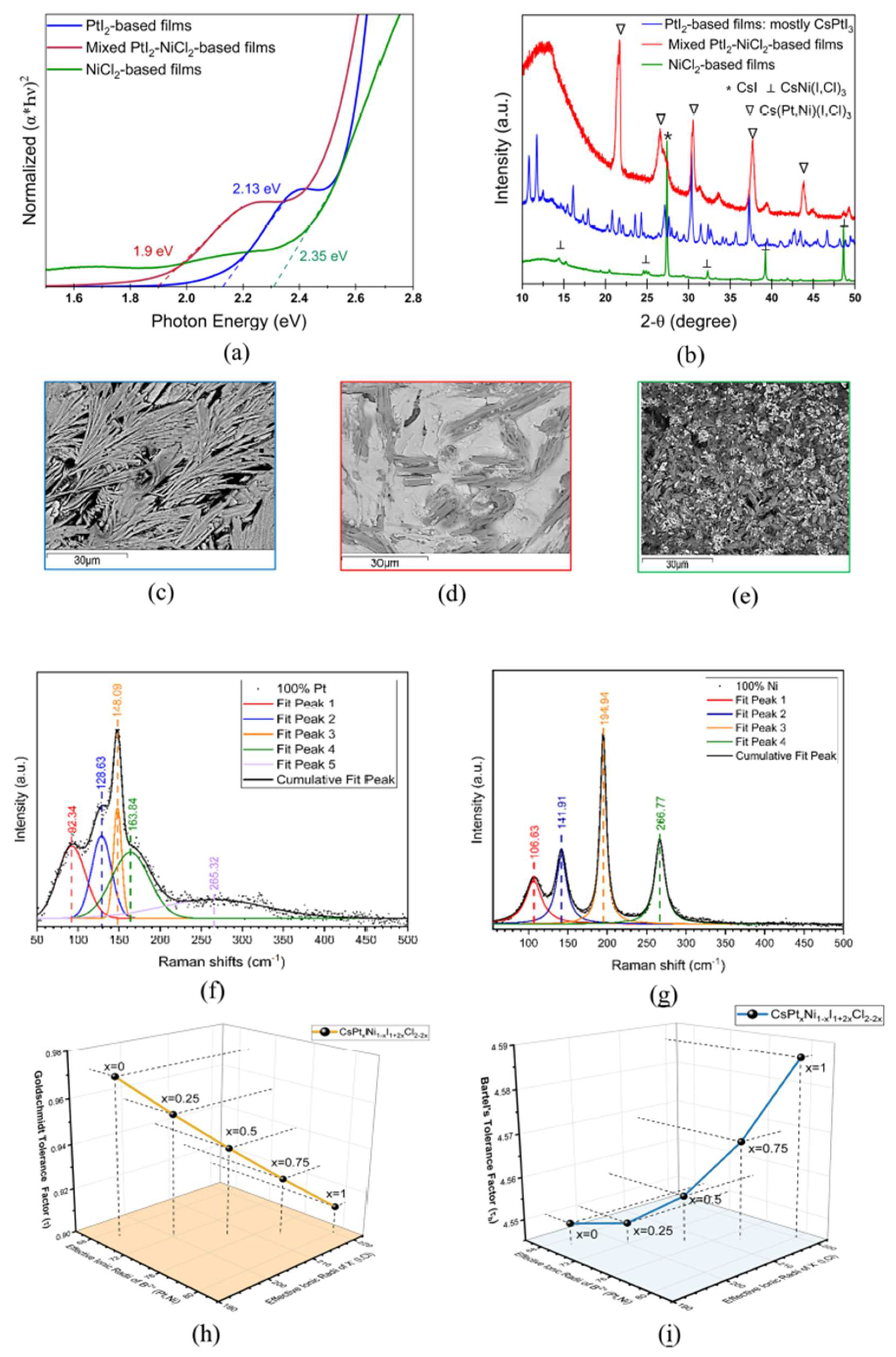

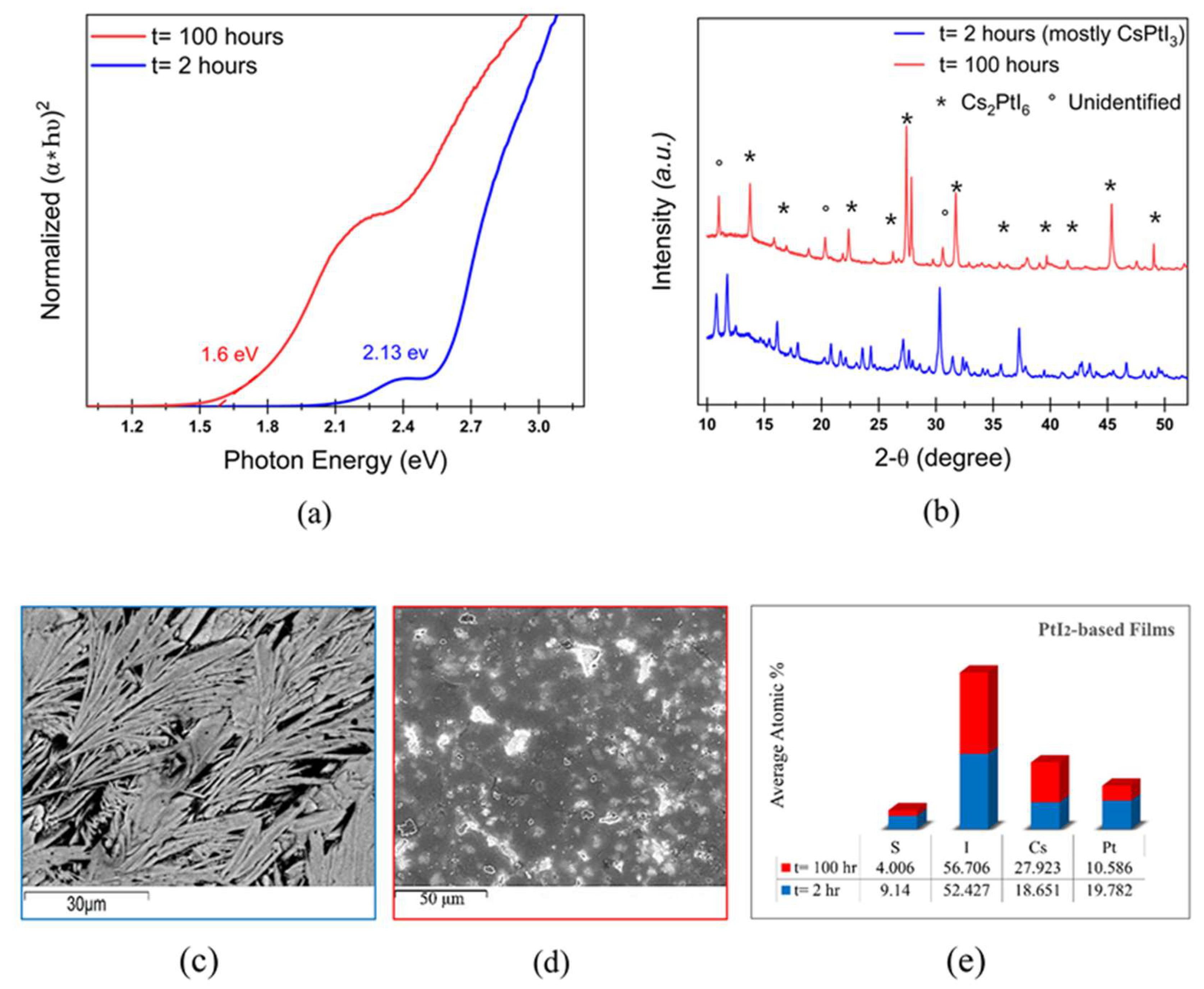

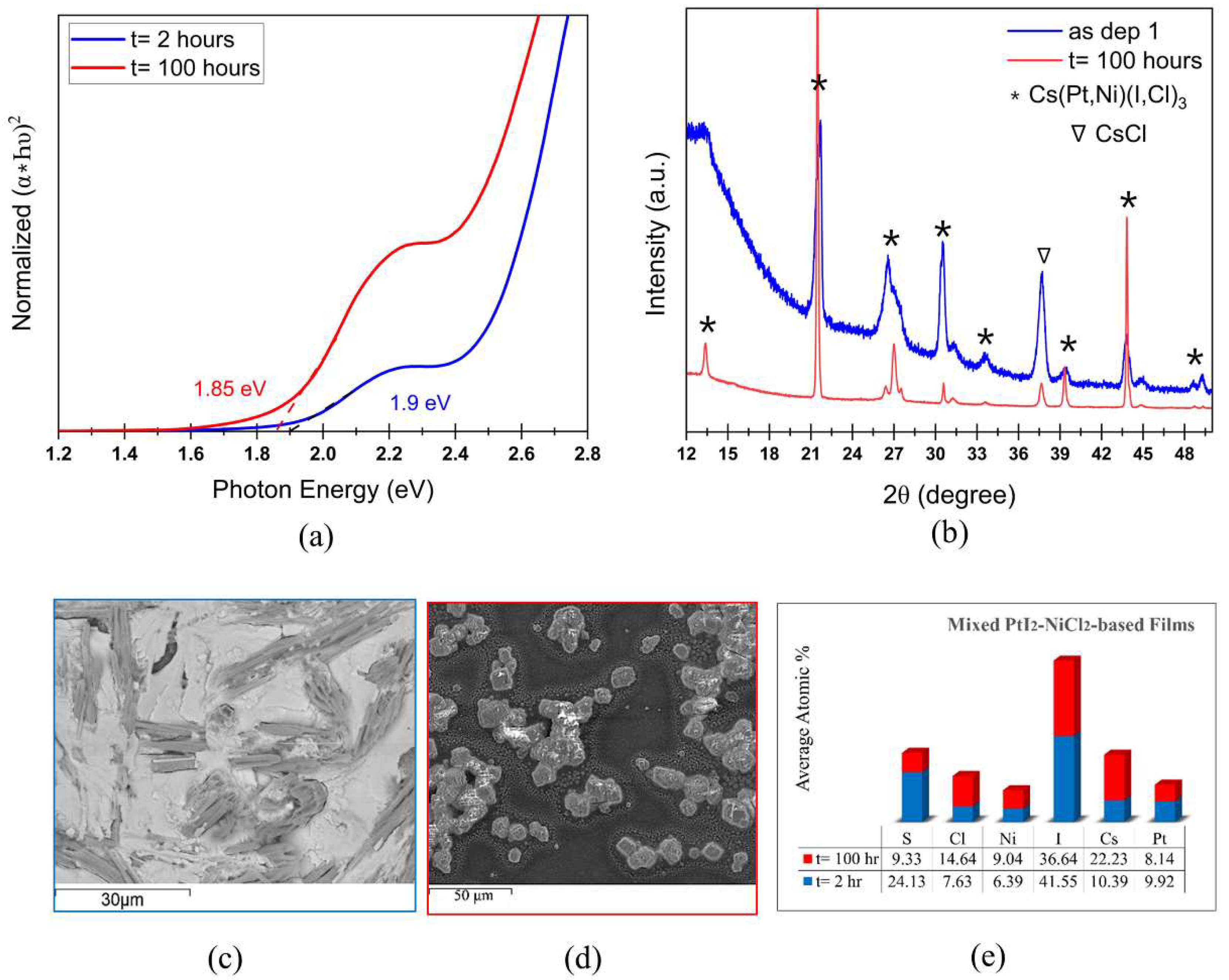

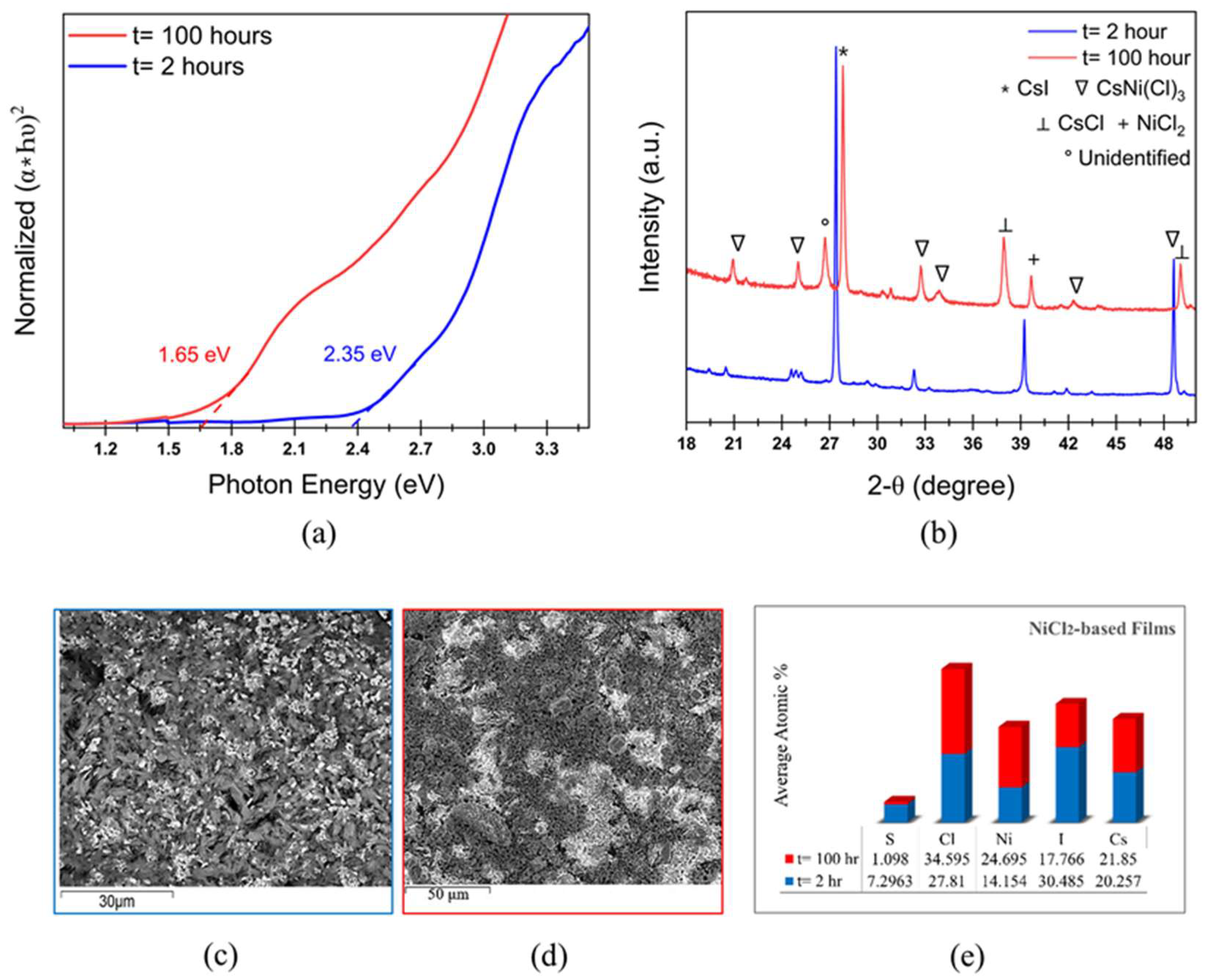

Cs2PtI6 is a promising photoabsorber with direct bandgap of 1.4 eV and high carrier lifetime, however, the cost of Pt inhibits its commercial viability. Here, we explore the effect of replacing Pt with earth-abundant Ni in solution-processed Cs(PtxNi1-x)(I,Cl)3 thin-films on the properties and stability of the perovskite material. Films fabricated with CsI and PtI2 precursors result in perovskite phase with bandgap of 2.13 eV which transitions into stable Cs2PtI6 with a bandgap of 1.6 eV upon annealing. Complete substitution of PtI2 in films with CsI + NiCl2 precursors results in a wider bandgap of 2.35 eV and SEM shows 2 phases- a rod-like structure identified as CsNi(I,Cl)3 and residual white particles of CsI, also confirmed by XRD and Raman spectrum. Upon extended thermal annealing, the bandgap reduces to 1.65 eV and transforms to CsNiCl3 with a peak shift to higher 2-theta. Partial substitution of PtI2 with NiCl2 in mixed 50-50 Pt-Ni-based films produces a bandgap of 1.9 eV exhibiting a phase of Cs(Pt,Ni)(I,Cl)3 composition. A similar bandgap of 1.85 eV and the same diffraction pattern with improved crystallinity is observed after 100 hours of annealing, confirming the formation of a stable mixed Pt-Ni phase.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

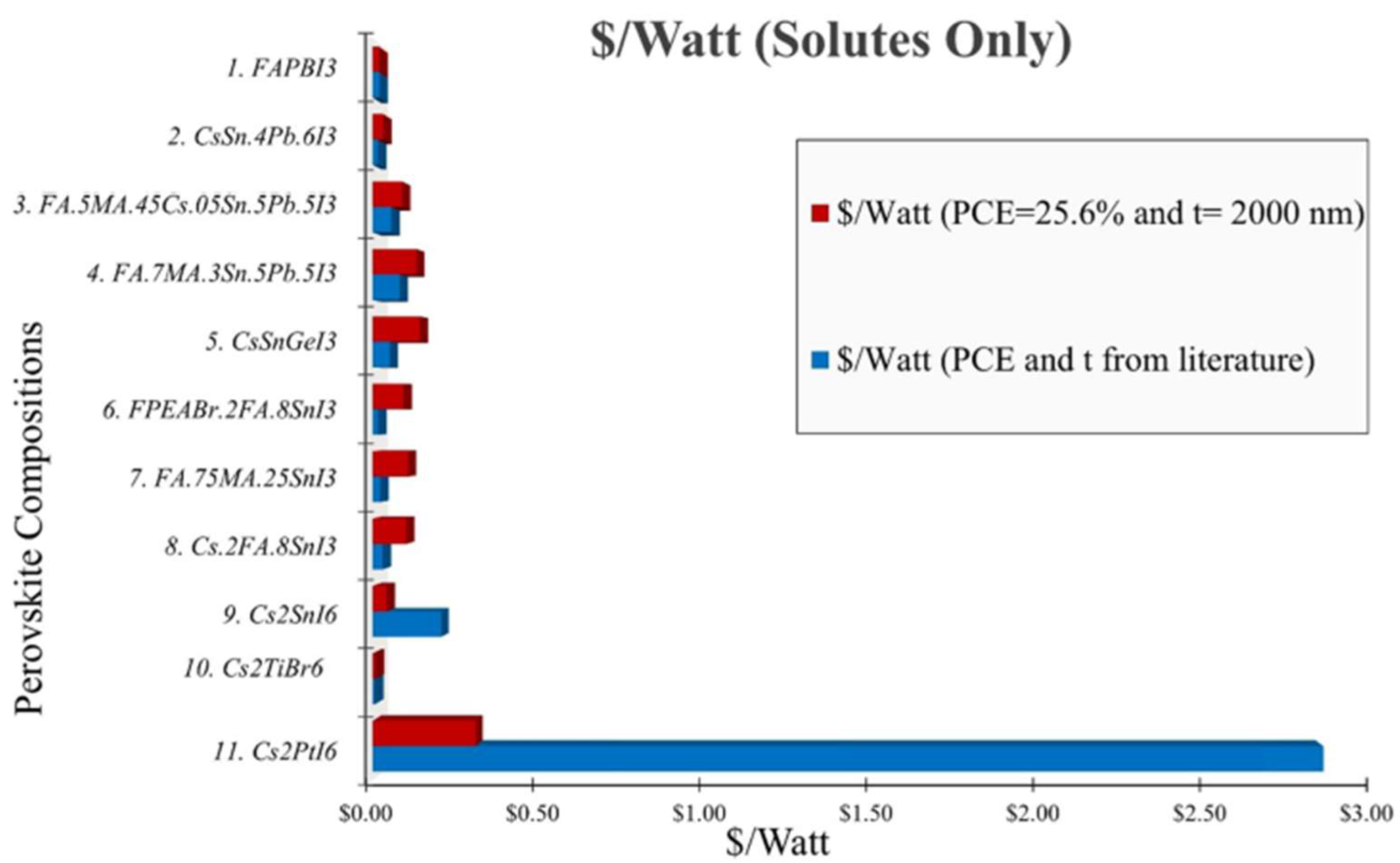

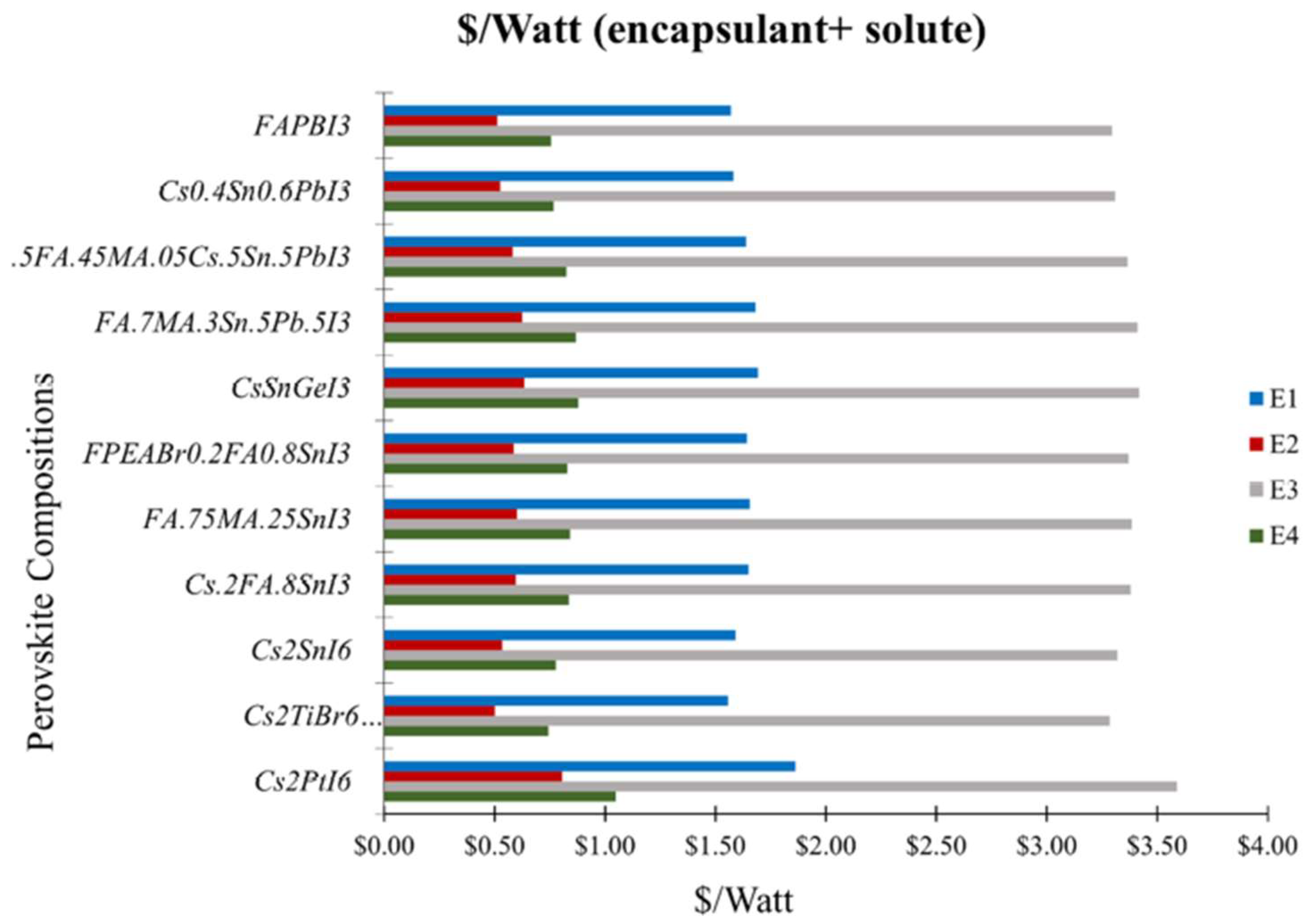

3.1. Cost Analysis of Solutes for Perovskite Precursor and Encapsulation for HPSCs

3.2. Pt-Ni Mixing in Halide Perovskite

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency.html (accessed on 06 11 2024).

- Jeong, J.; Kim, M.; Seo, J.; Lu, H.; Ahlawat, P.; Mishra, A.; Yang, Y.; Hope, M. A.; Eickemeyer, F. T.; Kim, M.; Yoon, Y. J.; Choi, I. W.; Darwich, B. P.; Choi, S. J.; Jo, Y.; Lee, J. H.; Walker, B.; Zakeeruddin, S. M.; Emsley, L.; Rothlisberger, U.; Hagfeldt, A.; Kim, D. S.; Grätzel, M.; Kim, J. Y. Pseudo-halide anion engineering for α-FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells. Nature 2021, 592(7854), 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Xu, J.; Wei, M.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Xiao, K.; Chen, B.; Park, S. M.; Chen, G.; Atapattu, H.R.; Graham, K. R.; Xu, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Sargent, E. H.; Tan, H. All-perovskite tandem solar cells with improved grain surface passivation. Nature 2022, 603, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; You, J.; Yang, Y. Addressing the stability issue of perovskite solar cells for commercial applications. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Lu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, C.; Yi, X; Zhu, G.; Lv, H.; Ma, L.; Chen, T.; Tie, Z.; Jin, Z.; Liu, J. All-Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138(49), 15829–15832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X. X.; Luo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, R.; Zhang, B.; Züttel, A.; Feng, Y.; Nazeeruddin, M. K. Stable and High-Efficiency Methylammonium-Free Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1905502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Kim, M.; Lee, S. U.; Kim, H.; Kim, G.; Choi, K.; Lee, J. H.; Seok, S. I. Efficient, stable solar cells by using inherent bandgap of α-phase formamidinium lead iodide. Science 2019, 366(6466), 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, L. K.; Park, N. G.; Zhu, K.; Huang, W.; Qi, Y. Perovskite Solar Cells—Towards Commercialization. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2(8), 1749–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, H. L.; Jiao, W. B.; Wang, Q.; Wei, M.; Cantone, I.; Lü, J.; Abate, A. Biological impact of lead from halide perovskites reveals the risk of introducing a safe threshold. Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijtens, T.; Prasanna, R.; Parker, A. G.; Toney, M. F.; McGehee, M. D. Mechanism of Tin Oxidation and Stabilization by Lead Substitution in Tin Halide Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2(9), 2159–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, N. K.; Stranks, S. D.; Abate, A.; Wehrenfennig, C.; Guarnera, S. Haghighirad, A. A.; Sadhanala, A.; Eperon, G. E.; Pathak, S. K.; Johnston, M. B.; Petrozza, A.; Herza, L. M.; Snaith, H. J. Lead-free organic–inorganic tin halide perovskites for photovoltaic applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3061–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, P.; Xue, T.; Su, M.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T.; Han, L.; Aldamasy, M.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F.; Song, Y. Design of Low Bandgap CsPb1−xSnxI2Br Perovskite Solar Cells with Excellent Phase Stability. Small 2021, 17, 2101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, K.; Kamarudin, M. A.; Hirotani, D.; Hamada, K.; Shen, Q.; Iikubo, S.; Minemoto, T.; Yoshino, K.; Hayase, S. Lead-free tin-halide perovskite solar cells with 13% efficiency. Nano Energy 2020, 74, 104858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Liu, A.; Zhou, Y.; Han, Q.; Yu, F.; Gao, L.; Zhang, C.; Ma, T. Novel Lead-Free Material Cs2PtI6 with Narrow Bandgap and Ultra-Stability for Its Photovoltaic Application. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces 2020, 12(40), 44700–44709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, D.; Murshed, R.; Larson, H.; Usprung, B.; Soltanmohamad, S.; Pandey, R. , Barnard, E. S.; Rockett, A.; Hartmann, T.; Castelli, I. E.; Bansal, S. Air Stable, High-Efficiency, Pt-Based Halide Perovskite Solar Cells with Long Carrier Lifetimes. Phys. Status Solidi RRL. 2020, 14, 2000182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkons, C.; Murshed, R.; Bansal, S. Numerical Analysis of Pb-Free Perovskite Absorber Materials: Prospects and Challenges. Solar RRL. 2020, 4, 2000299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V. K.; Markad, G. B.; Nag, A. Band Edge Energies and Excitonic Transition Probabilities of Colloidal CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) Perovskite Nanocrystals. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavney, A. H.; Hu, T.; Lindenberg, A. M.; Karunadasa, H.I. A Bismuth-Halide Double Perovskite with Long Carrier Recombination Lifetime for Photovoltaic Applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2016, 138, 2138–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, P.; Wei, S. Band Structure Engineering of Cs2AgBiBr6 Perovskite through Order–Disordered Transition: A First-Principle Study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, Y.; Rani, U.; Shukla, A.; Joshi, T. K.; Verma, A. S. Transition metal-based halides double Cs2ZSbX6 (Z = Ag, Cu, and X = Cl, Br, I) perovskites: A mechanically stable and highly absorptive materials for photovoltaic devices. J Solid State Chem. 2022, 314, 123420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, M. R.; Giustino, F. Computational Screening of Homovalent Lead Substitution in Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskites. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120(1), 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, G.; Zhao, Q.; Gao, X. Non-precious transition metals as counter electrode of perovskite solar cells. Energy Storage Mater. 2017, 7, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Sheng, X.; Shi, B.; Feng, X.; Xu, T. Nickel-Cathoded Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118(45), 25878–25883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, T.; Okuno, T.; Awaga, K. Observation of Spontaneous Magnetization in the Layered Perovskite Ferromagnet, (p-Chloroanilinium)2CuBr4. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37(9), 2129–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Bradford, A. J.; Slawin, A. M. Z.; Bode, B. E.; Fusco, E.; Lee, S. L.; Tang, C. C.; Lightfoot, P. Structural Features in Some Layered Hybrid Copper Chloride Perovskites: ACuCl4 or A2CuCl4. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60(15), 11014–11024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNulty, J. A.; Lightfoot, P. Unprecedented tin iodide perovskite-like structures featuring ordering of organic moieties. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56(33), 4543–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, A.; Mack, S. A.; Lin, Y.; Mao, W. L.; Neaton, J. B.; Karunadasa, H. I. High Compression-Induced Conductivity in a Layered Cu–Br Perovskite. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4017–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, L.; Hu, T.; Li, M.; Ling, B.; Lassoued, M. S.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Zheng, Y. Template effects in Cu(i)–Bi(iii) iodide double perovskites: a study of crystal structure, film orientation, band gap and photocurrent response. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 7288–7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qin, H.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Hu, J. Acetone sensing properties and mechanism of nano-LaFeO3 thick-films. Sensors and Actuators B 2016, 235, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, A. A.; Sackmann, A.; Weimar, U.; Barsan, N. A highly selective sensor to acetylene and ethylene based on LaFeO3. Sensors and Actuators B 2020, 303, 127204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, J. C.; Trout, J. M. Transformer oil DGA monitoring technology study 2015. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power Engineering Society Transmission and Distribution Conference (July 2016.

- Duval, M. A review of faults detectable by gas-in-oil analysis in transformers. IEEE Electrical Insulation Magazine. 2002, 18, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, B.; Schnorr, J. M.; Swager, T. M. Selective Detection of Ethylene Gas Using Carbon Nanotube-based Devices: Utility in Determination of Fruit Ripeness. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5752–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Luo, T.; Cao, J.; Yin, M.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Z. Application of moisture-induced discoloration material Nickel(II) iodide in humidity detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 309, 127769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. M.; Shimizu, Y.; Teraoka, Y.; Miura, N.; Yamazoe, N. Oxygen sorption and catalytic properties of La1−xSrxCo1−yFeyO3 Perovskite-type oxides. J Catal. 1990, 121, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, H.; Yamada, T.; Eguchi, K.; Seiyama, T. Catalytic combustion of methane over various perovskite-type oxides. Appl Catal. 1986, 26, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, M. O.; Norman, A. K.; Hüttermann, C. F.; Morris, M. A. Catalytic oxidation over lanthanum-transition metal perovskite materials. Catalysis Today 1999, 47, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, M.; Matsui, T.; Domanski, K.; Seo, J.; Ummadisngu, A.; Zakeeruddin, S. M.; Baena, J. P. C.; Tress, W. R.; Abate, A.; Hagfeldt, A.; Grätzel, M. Incorporation of rubidium cations into perovskite solar cells improves photovoltaic performance. Science 2016, 354(6309), 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, J. P. C.; Saliba, M.; Buonassisi, T.; Grätzel, M.; Abate, A.; Tress, W.; Hagfeldt, A. A. Promises and challenges of perovskite solar cells. Science 2017, 358(6364), 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D. M.; Park, K.; Kim, D. H.; Park, J.; Shojaei, F.; Kang, H. S.; Ahn, J.; Lee, J. W.; Song, J. K. Reversible Halide Exchange Reaction of Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Colloidal Nanocrystals for Full-Range Band Gap Tuning. Nano Lett. 2015, 15(8), 5191–5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugadoss, G.; Tanake, S.; Mizuta, G.; Kanaya, S.; Nishino, H.; Umeyama, T.; Imahori, H.; Ito, S. Light stability tests of methylammonium and formamidinium Pb-halide perovskites for solar cell applications. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 54, 08KF08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.; Seo, S.; Cho, S. M.; Park, N. Formamidinium and Cesium Hybridization for Photo- and Moisture-Stable Perovskite Solar Cell. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1501310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Xie, W.; Ding, H.; Chen, Y.; Thirumal, K.; Wong, L. H.; Mathews, N.; Mhaisalkar, S. G.; Sherbume, M.; Asta, M. Computational Study of Halide Perovskite-Derived A2BX6 Inorganic Compounds: Chemical Trends in Electronic Structure and Structural Stability. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29(18), 7740–7749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, R.; Bansal, S. Additive-Assisted Optimization in Morphology and Optoelectronic Properties of Inorganic Mixed Sn-Pb Halide Perovskites. Materials 2022, 15(3), 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lead and Copper Rule, US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/lead-and-copper-rule (accessed on 06 11 2024).

- Lead(II) iodide, PbI2, CID 24931, PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/24931 (accessed on 06 11 2024).

- Aitola, K.; Sonal, G. G.; Markkanen, M.; Kaschuk, J. J.; Hou, X.; Miettunen, K.; Lund, P. D. Encapsulation of commercial and emerging solar cells with focus on perovskite solar cells. Solar Energy 2022, 237, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czanderna, A. W.; Pern, F. J. Encapsulation of PV modules using ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer as a pottant: A critical review. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 1996, 43, 101–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, G., Faes, A., Li, H., Galliano, F., Gragert, M., Yao, Y., Despeisse, M., Ballif, C. Lamination process and encapsulation materials for glass–glass PV module design. Photovoltaics Int. 2014, 1, 1–8.

- López-Escalante, M.C.; Caballero, L. J.; Martín, F.; Gabás, M.; Cuevas, A.; Ramos-Barrado, J.R. Polyolefin as PID-resistant encapsulant material in PV modules. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2016, 144, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Liu, P.; Zhang, K.; Tang, G.; Hou, H.; Li, B.; Wang, W. Vinyl-Functionalized Polyolefins for Fast Photovoltaic Cell Encapsulation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2(7), 2571–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adothu, B.; Bhatt, P.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Zele, S.; Oderkerk, J.; Sagar, H. P.; Costa, F. R.; Mallick, S. Newly developed thermoplastic polyolefin encapsulant–A potential candidate for crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules encapsulation. Solar Energy 2019, 194, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, N. A. N.; Yang, M.; He, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Han, C. B.; Zhang, Y. Influence of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) on photovoltaic performance and perovskite solar cell stability. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2020, 4, 4257–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Jeong, I.; Lee, J.; Ko, M. J.; Yong, K. Enhancing Stability of Perovskite Solar Cells to Moisture by the Facile Hydrophobic Passivation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7(31), 17330–17336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Li, M.; Xie, J.; Bao, S.; Jin, P.; Huang, A. Long-term stable perovskite solar cells with room temperature processed metal oxide carrier transporters. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2019, 7, 21085–21095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xia, R.; Gao, J.; Wang, S.; Zhu, J.; Xiong, W.; Yuan, N.; Ding, J. A Facile Approach for the Encapsulation of Perovskite Solar Cells. Energies 2023, 16(2), 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Lee, K.; Huang, W.; Siao, H.; Chang, Y. High-Performance, Air-Stable, Low-Temperature Processed Semitransparent Perovskite Solar Cells Enabled by Atomic Layer Deposition. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27(14), 5122–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jeon, G. G.; Kim, J. H.; Kim, J.; Park, N. Design of a Flexible Thin-Film Encapsulant with Sandwich Structures of Perhydropolysilazane Layers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14(30), 34678–34685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, C. T. The effect of the halide anion on the optical properties of lead halide perovskites. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 2019, 195, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, E.; Ozturk, T.; Xiang, W.; Sadegh, F.; Prochowicz, D.; Tavakoli, M. M.; Yadav, P.; Yilmaz, M.; Akin, S. The effect of B-site doping in all-inorganic CsPbIxBr3−x absorbers on the performance and stability of perovskite photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci., 2023, 16, 372–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Chen, Z.; Ye, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Zang, J. Gram-scale synthesis of all-inorganic perovskite quantum dots with high Mn substitution ratio and enhanced dual-color emission. Nano Research 2019, 12(7), 1733–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C. F. J.; Deng, X.; Zheng, J.; Kim, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Bing, J.; Wilkinson, B.; Hu, L.; Patterson, R.; Huang, S.; Ho-Baillie, A. Enhanced performance via partial lead replacement with calcium for a CsPbI3 perovskite solar cell exceeding 13% power conversion efficiency. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2018, 6, 5580–5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raw, A. D.; Ibers, J. A.; Poeppelmeier, K. R. Syntheses and structure of hydrothermally prepared CsNiX3 (X=Cl, Br, I). Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2012, 192, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICSD, Cs2PtI6, Details on Search Result. Available online: https://icsd.fiz-karlsruhe.de/display/details.xhtml.

- Jandl, S.; Banvile, M.; Xu, Q. F.; Ait-Ouali, A. Raman and infrared studies of the one-dimensional antiferromagnet CsNiCl3. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 11585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolari, P. Engineering Properties of Transition Metal Halides via Cationic Alloying. Master Thesis, Arizona State University 2020.

- Shang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, M.; Horvath, D.; Simpson, M. F.; Lockwoodtf, D. J.; Bertrand, D.; Carrarat, P.; Mischlert, G.; Billereys, D.; Terriers, C. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys 1979, 12, 3615.

- Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wan, J.; Wen, R.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, Z.; Xie, L. Vapor Deposition of Magnetic Van der Waals NiI2 Crystals. ACS Nano 2020, 14(8), 10544–10551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baechle, W.; Rotter, H. W.; Thiele, G.; Clark, R. J. H. Raman and resonance Raman spectroscopy of iodoplatinate(II), iodoplatinate(IV) and mixed-valence iodoplatinate(II,IV) salts. Inorganica Chimica Acta 1992, 191, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, H.; Harada, I.; Shimanouchi, T. Resonance Raman Effect of Octahedral Complex Ions, PtBr62- and PtI62-. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 1974, 2, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. F.; Williams, K. P. J.; Smith, T.; Ramirez-Cuesta, A. J.; Daemen, L. L. Vibrational Spectroscopy of Hexahalo Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61(15), 5844–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, G.; Weigl, W.; Wochner, H. Die Platiniodide PtI2 und Pt3I8. Z. anorg. allg. Chem. 1986, 539, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortecchia, D.; Dewi, H. A.; Yin, J.; Bruno, A.; Chen, S.; Baikie, T.; Boix, P. P.; Grätzel, M.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Soci, C.; Mathews, N. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55(3), 1044–1052.

- Bartel, C. J.; Sutton, C.; Goldsmith, B. R.; Ouyang, R.; Musgrave, C. B.; Ghiringhelli, L. M.; Scheffler, M. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav0693.

- Yeo, J.; Kang, R.; Lee, S.; Jeon, Y.; Myoung, N.; Lee, C.; Kim, D.; Yun, J.; Seo, Y.; Kim, S.; Na, S. Highly efficient and stable planar perovskite solar cells with reduced graphene oxide nanosheets as electrode interlayer. Nano Energy 2015, 12, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegler, T. D.; Reimnitz, L. C.; Suri, M.; Cho, S. H.; Bergerud, A. J.; Abney, M. K.; Milliron, D. J.; Korgel, B. A. Deliquescent Chromism of Nickel (II) Iodide Thin Films. Langmuir 2019, 35(6), 2146–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Structure | 2Ɵ | 2Ɵ | 2Ɵ | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std. CsNiCl3 (ICSD: 423828) |

20.8° | 25° | 30.24° | 63 |

| New Structure: Cs(Pt,Ni)(I,Cl)3 |

21.68° | 26.56° | 30.52° | Our work |

| Std. Cs2PtI6 (ICSD: 37193) |

22.52° | 27.8 | 32.14° | 64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).