Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

-

Radar early warning technology:

- (1)

- American Echo Shield 4D radar combines Ku-band BSA beamforming and dynamic waveform synthesis. It offers wireless positioning service at 15.7-16.6 GHz and wireless navigation function at 15.4-15.7 GHz, with a tracking accuracy of 0.5° and an effective detection distance of 3 km;

- (2)

- HARRIER DSR UAV surveillance radar developed by DeTecT Company of the United States adopts a solid-state Doppler detection radar system, which is used for small RCS targets in complex clutter environments. The detection range of UAVs flying without RF and GPS programs is 3.2 km;

- (3)

- Hof Institute of High-Frequency Physics and Radar Technology in Flawn, Germany, proposed Scanning Surveillance Radar System (SSRS) technology. The FMCW radar sensor was scanned mechanically, with a scanning frequency of 8 Hz and a bandwidth of 1 GHz. The maximum range resolution was 15 cm, and the maximum detection range was 153.6 m.

-

Passive optical imaging technology:

- (1)

- Poland Advanced Protection System Company designed the SKYctrl anti-UAV system, which includes an ultra-precision FIELDctrl 3D MIMO radar, PTZ day/night camera, WiFi sensor, and acoustic array. The detecting target’s minimum height is 1 m;

- (2)

- France’s France-Germany Institute in Saint Louis adopts two optical sensing channels, and the passive colour camera provides the image of the target area, with a field of view of 4°×3°, and realizes the detection of DJI UAV from 100 m to 200 m;

- (3)

- The National Defense Development Agency of Korea proposed a UAV tracking method using KCF and adaptive threshold. The system includes a visual camera, a pan/tilt, an image processing system, a pan/tilt control computer, a driving system and a liquid crystal display, which can detect the UAV with a target size of about 30×30 cm, a flying speed of about 10 m/s and a distance of 1.5 km;

- (4)

- DMA’s low-altitude early warning and tracking photoelectric system, developed by China Hepu Company, integrates a high-definition visible light camera and infrared imaging sensor. The system can detect micro UAVs within 2 km, and the tracking angular velocity can reach 200°.

-

Acoustic detection technology:

- (1)

- Dedrone Company of Germany has developed Drone Tracker, a UAV detection system that uses distributed acoustic and optical sensors to detect UAVs comprehensively. It can detect UAVs illegally invading 50-80 m in advance;

- (2)

- Holy Cross University of Technology in Poland studied the acoustic signal of a rotary-wing UAV. Using an Olympus LS-11 digital recorder, the acoustic signal was recorded at a 44 kHz sampling rate and 16-bit signal resolution, and it was obtained as far as 200 m.

- The target is small and difficult to detect: the reflection cross-section of UAV radar is actively tiny, which is difficult for traditional radar to capture effectively;

- Complex background interference: it is greatly influenced by ground clutter, which increases the detection difficulty;

- Low noise and low infrared radiation: the sound wave and infrared characteristics generated by UAVs are weak, so it is difficult to detect by sound wave or infrared detector;

- Significant environmental impact: weather conditions such as smog and rainy days will affect the performance of traditional optical and acoustic detection.

2. System Design

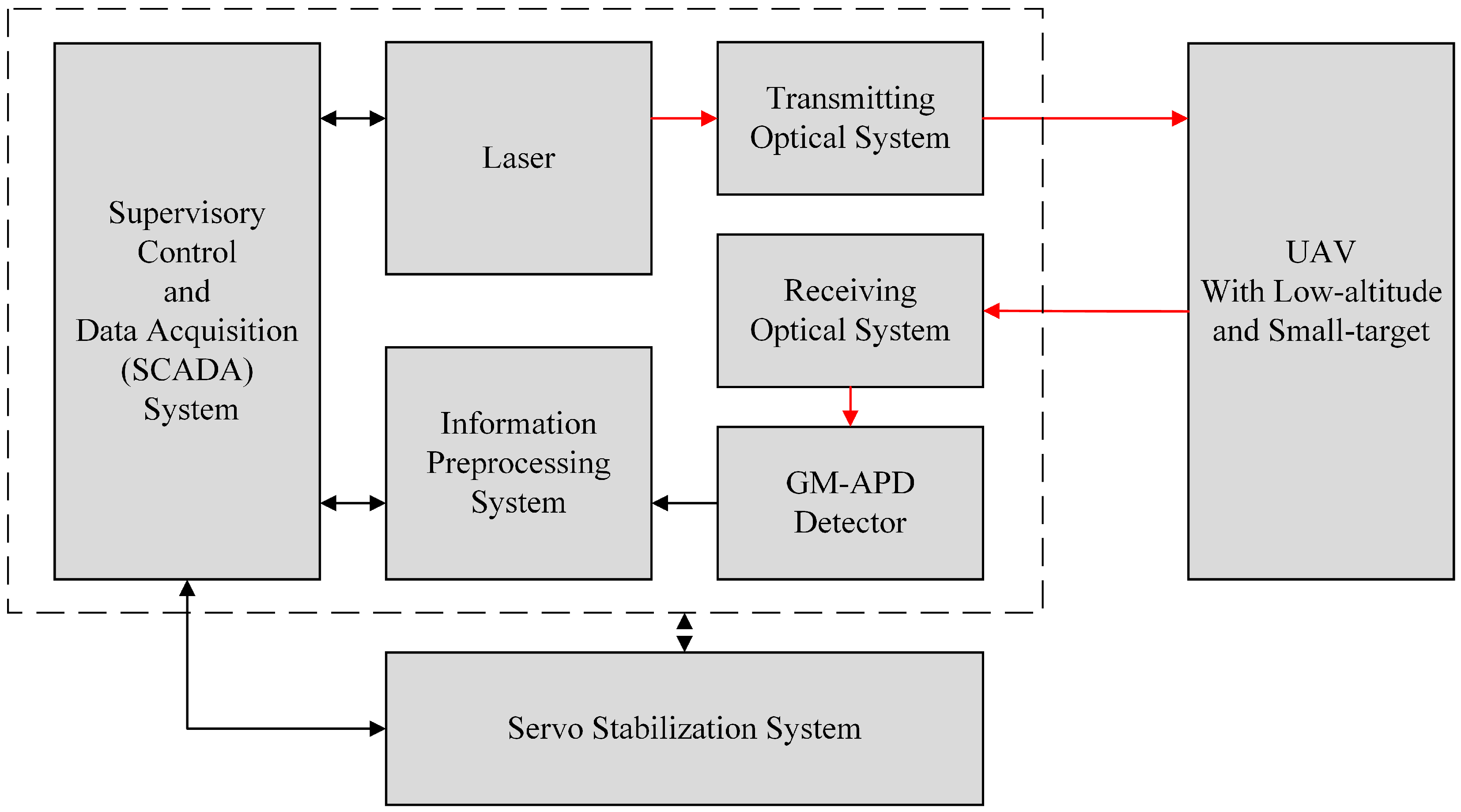

2.1. Design of Gm-APD LiDAR System

2.2. Detection Process of Gm-APD LiDAR Imaging System

- (1)

- Laser emission: The high-power and narrow-pulse laser is pointed to the UAV target after optical shaping;

- (2)

- Laser echo reception: Echo photons reflected by the target are converged on the GM-APD detector through the receiving optical system, triggering the avalanche effect;

- (3)

- Signal recording: GM-APD detector records the echo signal and transmits it to the FPGA data acquisition and processing system;

- (4)

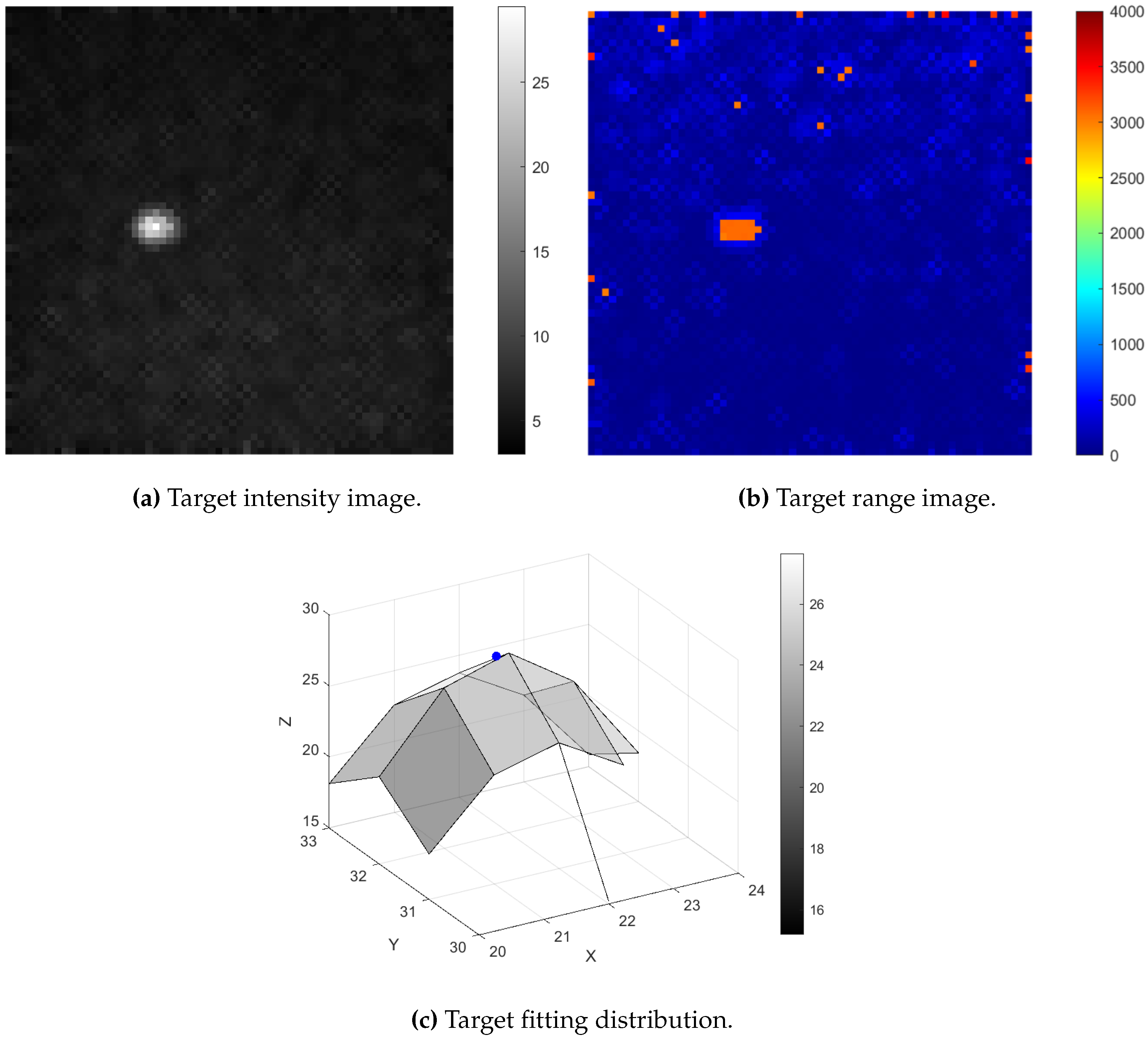

- Signal processing: The acquisition system processes the signal and reconstructs the intensity image and the range image of the UAV target;

- (5)

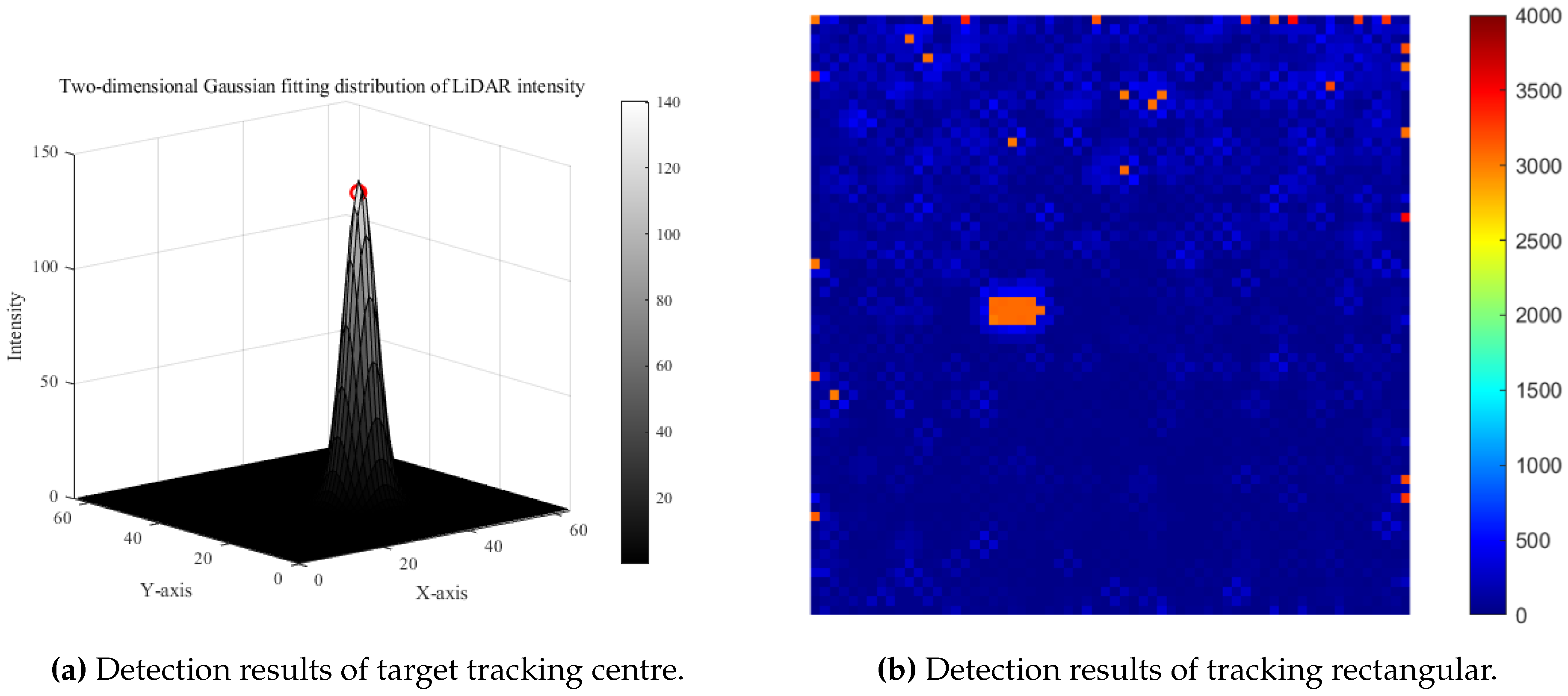

- Target fitting and tracking: Threshold filtering, Gaussian fitting, and Canny edge detection methods are adopted, and the Cam-Kalm algorithm is combined to realize real-time and automatic target tracking;

- (6)

- Dynamic adjustment: The FPGA system calculates the angle according to the miss distance, adjusts the pitch or azimuth of the servo platform, and dynamically tracks the target.

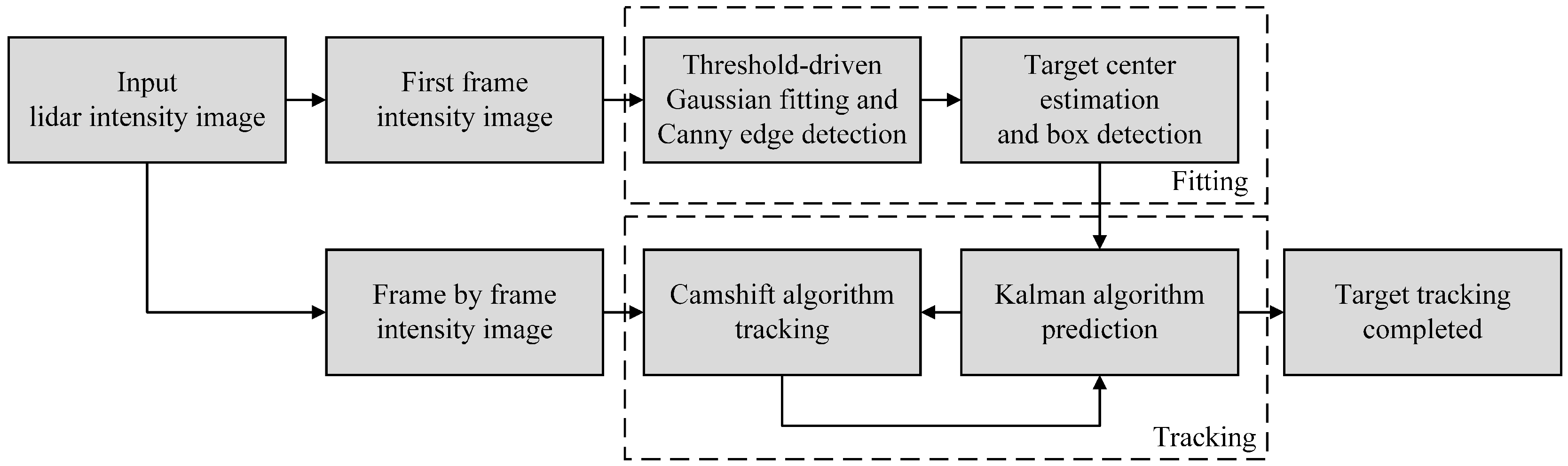

3. Description of Tracking Algorithm

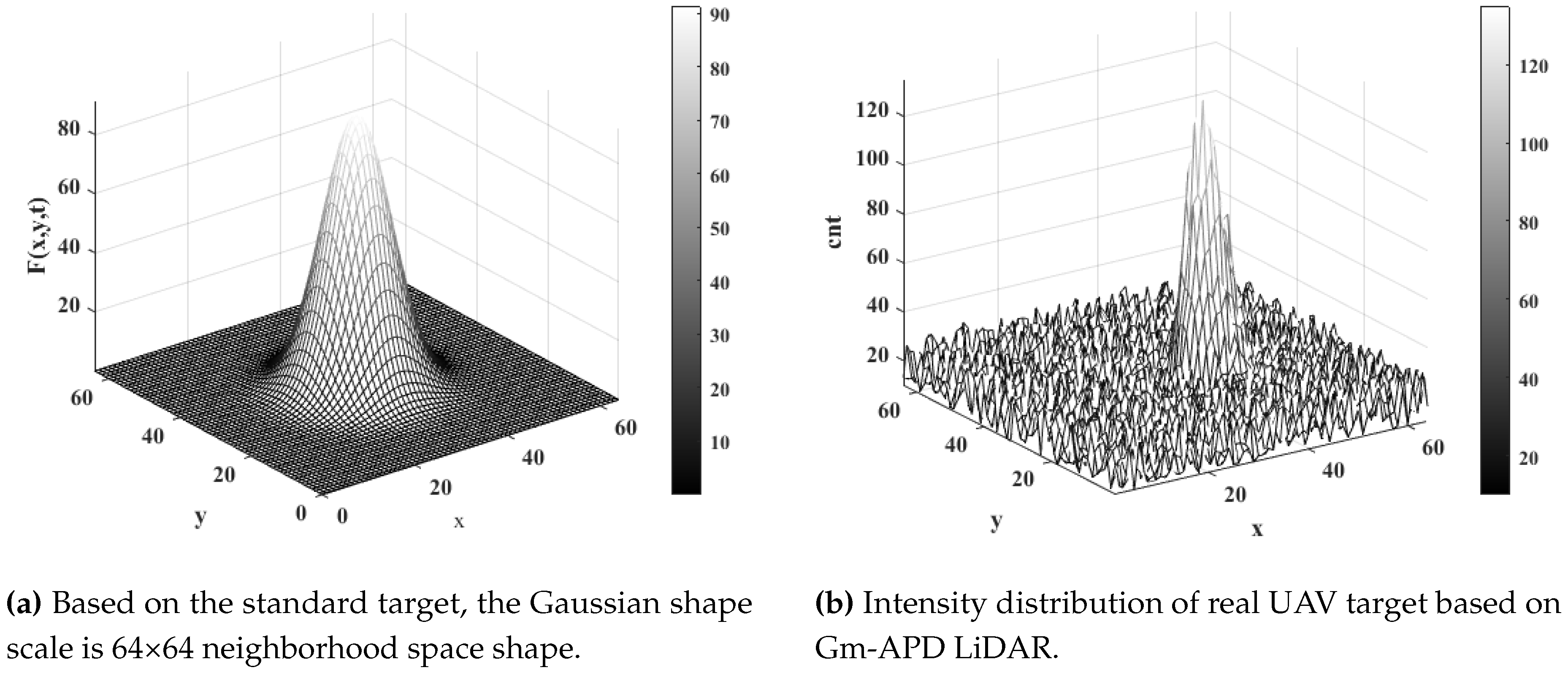

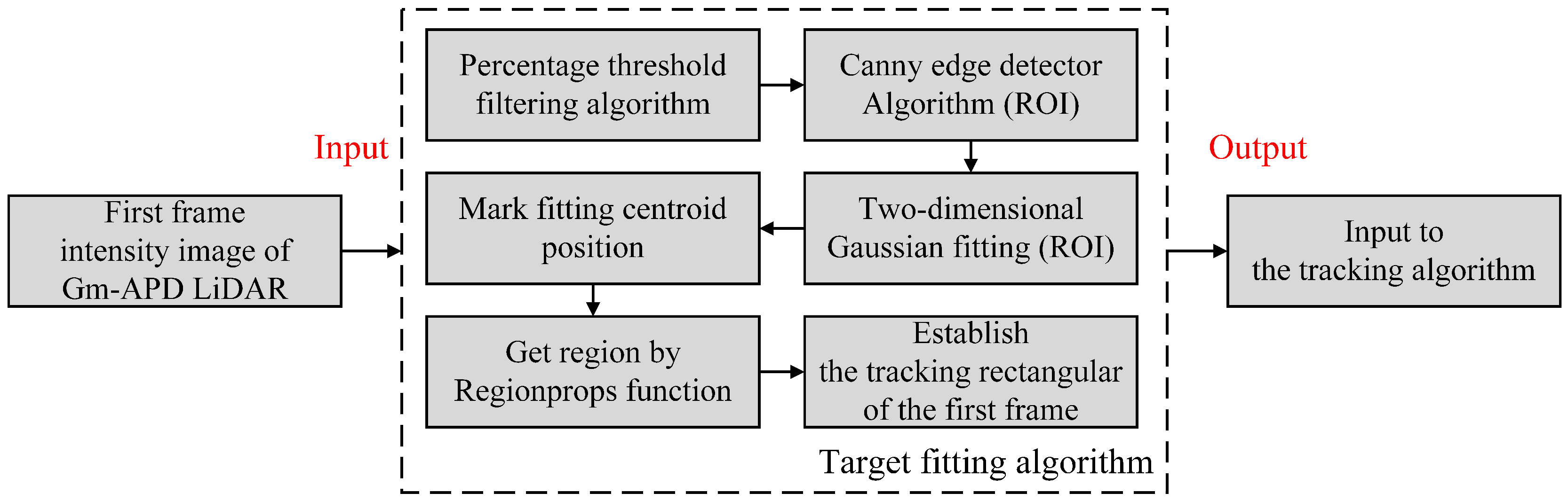

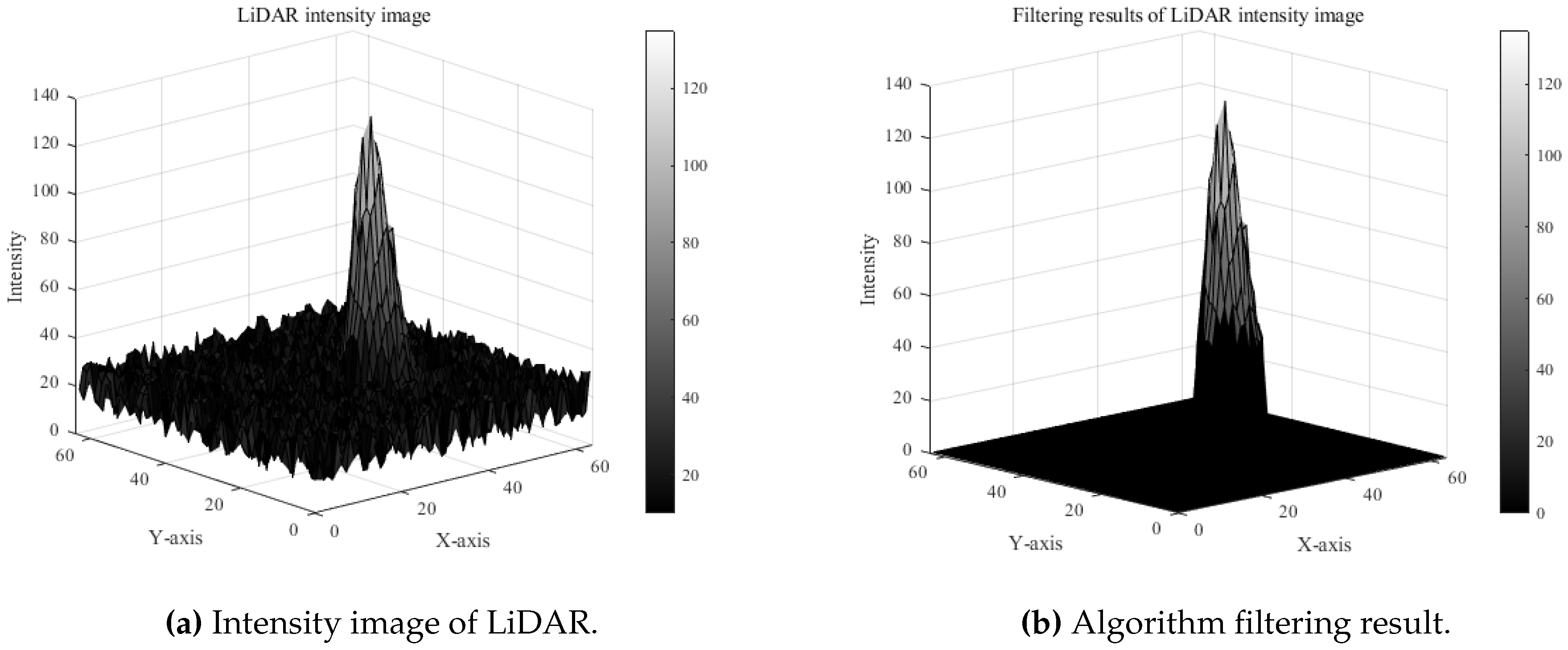

3.1. Target Extraction

- (1)

- There is little difference between the spatial distribution of the target intensity image and the geometric ideal shape;

- (2)

- The actual detected target presents an irregular convex pattern relative to the background, consistent with the smooth central convex feature of the standard model.

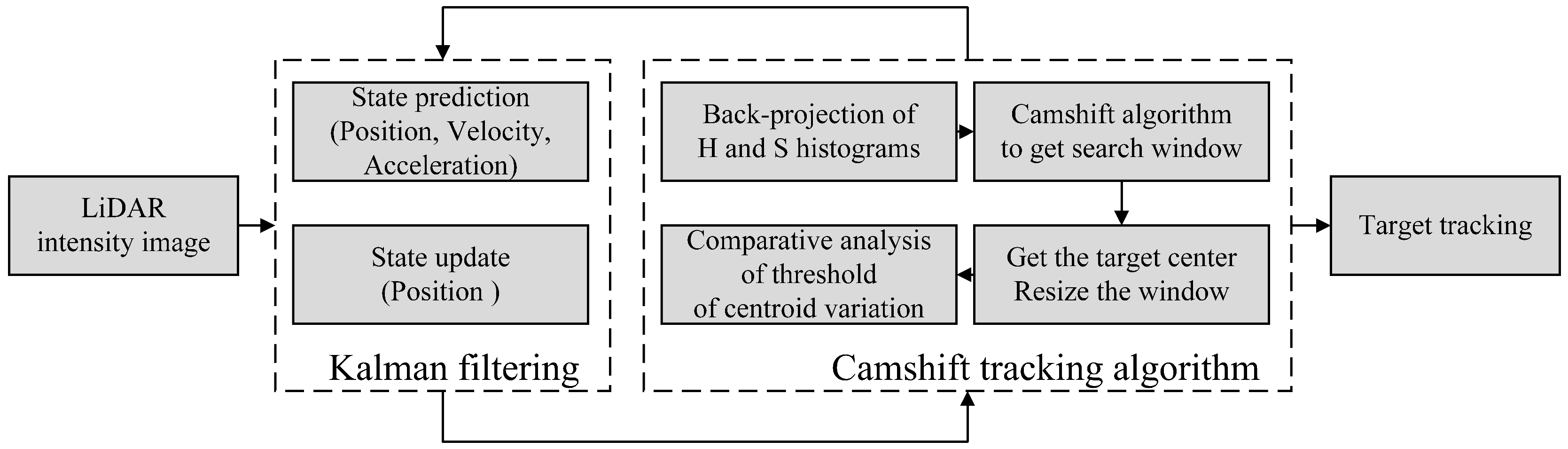

3.2. Target Tracking and State Prediction

- (1)

- Increase forecasting ability: Based on predicting the target position, velocity, and acceleration variables are introduced to improve the adaptability to the rapid change of UAV position. This not only improves the system’s robustness but also reduces the iterative calculation of the Camshift algorithm and accelerates the coordination with the two-dimensional tracking platform;

- (2)

- Reduce the false alarm rate: By predicting the speed and acceleration of the target, the moving trend of the target can be judged, and the influence of ghosts in LiDAR imaging can be reduced, thus reducing the false alarm rate;

- (3)

- Adaptive adjustment of search window: Realize the adaptive adjustment of the search window and effectively solve the loss of the tracking target caused by the expansion of the tracking window of the Camshift algorithm.

- Step 1

-

Initialization.

- (1)

- Automatic extraction of the first frame target. Use the fitting method in Section 3.1 to obtain the ROI of the target point and synchronously initialize the center position and size of the search window.

- (2)

-

Initialize the Kalman filter. The state prediction equation and the observation equation of the tracking system is:Where and represent the motion state vectors of and respectively; is the system state observation vector at the moment; A is the state transition matrix, which contains the dynamic model of target position, velocity and acceleration; H is the observation matrix, indicating the position of direct observation; and respectively representing the system state noise and the observed Gaussian distribution noise matrix [46].Where is the time interval between two adjacent frames. Accordingly, the covariance matrix of and corresponds to Q and R represent the uncertainty in the modeling process and the observed noise respectively, and its Formula updated to:

- Step 2

-

Backprojection of histogram of LiDAR intensity image.

- (1)

- Color space conversion. Read the intensity image of Gm-APD lidar, extract H and S components, and convert them into HSV colour space to enhance the colour difference between the target and background [47]. At the same time, the corresponding background component is set to zero to realize background filtering.

- (2)

- Back projection of histogram of the search area.

- Step 3

-

Calculate the search window.The centroid of the range profile search window of LiDAR is calculated by using its zero-order moment and first-order moment: is the pixel values at in the back projection image, where x and y change within the search window , the calculation steps are as follows:

- (1)

- Calculate the zero-order moment at the initial moment as follows:

- (2)

- Calculate the first moment in the x and y directions as follows:

- (3)

- Calculate the centroid coordinates of the tracking window as follows:

- (4)

- Moving the center of the search window to the center-of-mass position .

- Step 4

-

Calculate the trace window.Camshift algorithm obtains the directional target area through the second-order matrix:

- (1)

- Calculate the second moment in the x and y directions as follows:

- (2)

-

Calculate the new tracking window size () as:Among it,

- (3)

- Iterate continuously until the centroid position converges. The centroid of the target point is the iterative result , which is used to update and predict the Kalman filtering time .

- Step 5

-

Kalman filter prediction.At the moment , the state vector of UAV target motion is:Where, and is the speed of the target in the X and Y axis directions in the field of view, and is the acceleration of the target. According to Eq. (3) and Eq. (4), the motion state equation of the system is updated as follows:The motion observation equation of the system is updated as follows:

- Step 6

-

Repeat Steps 2, 3, 4 and 5.Take the predicted value in Step 3 as the search window center of the th frame search area.

4. Analysis of Experimental Results

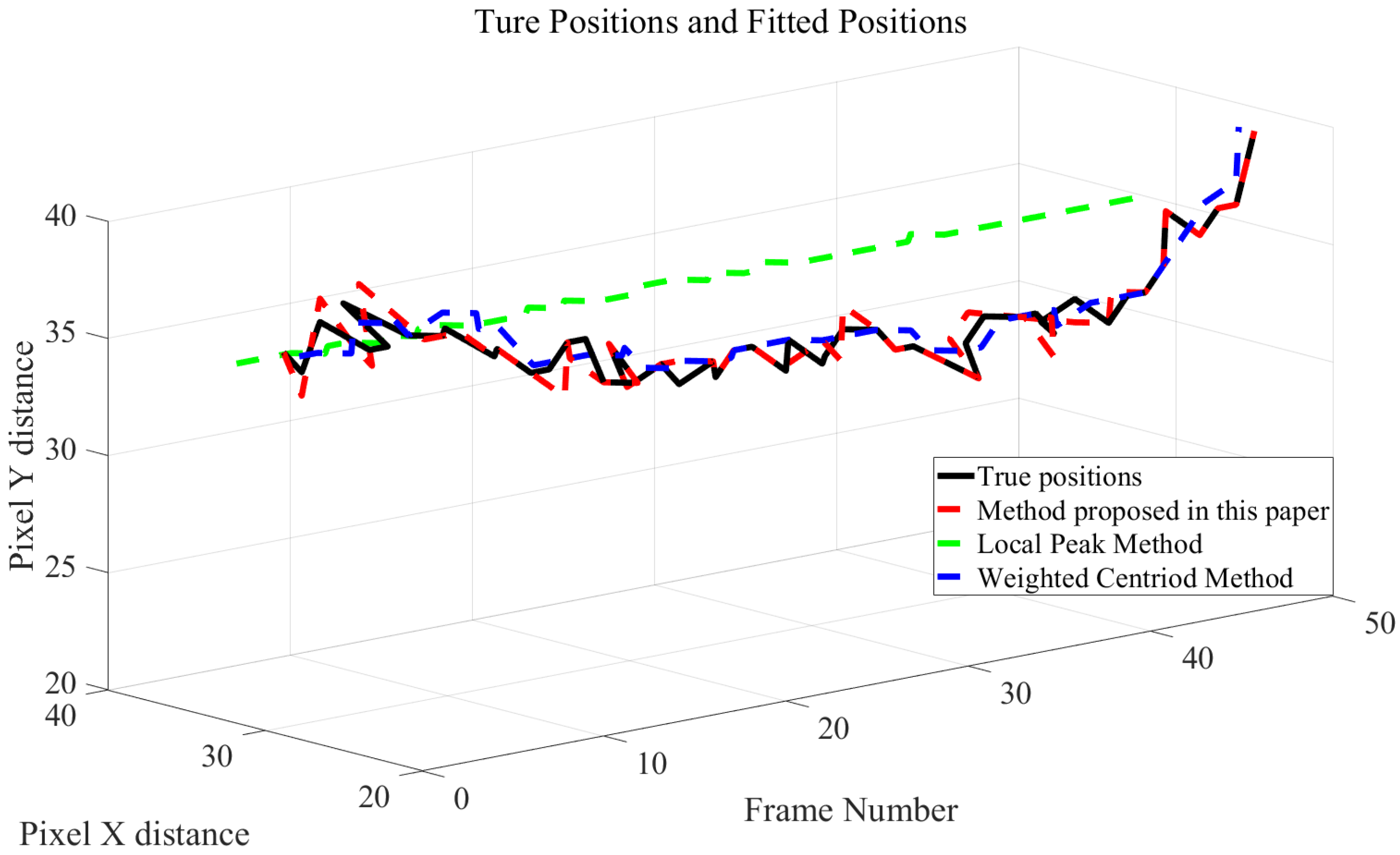

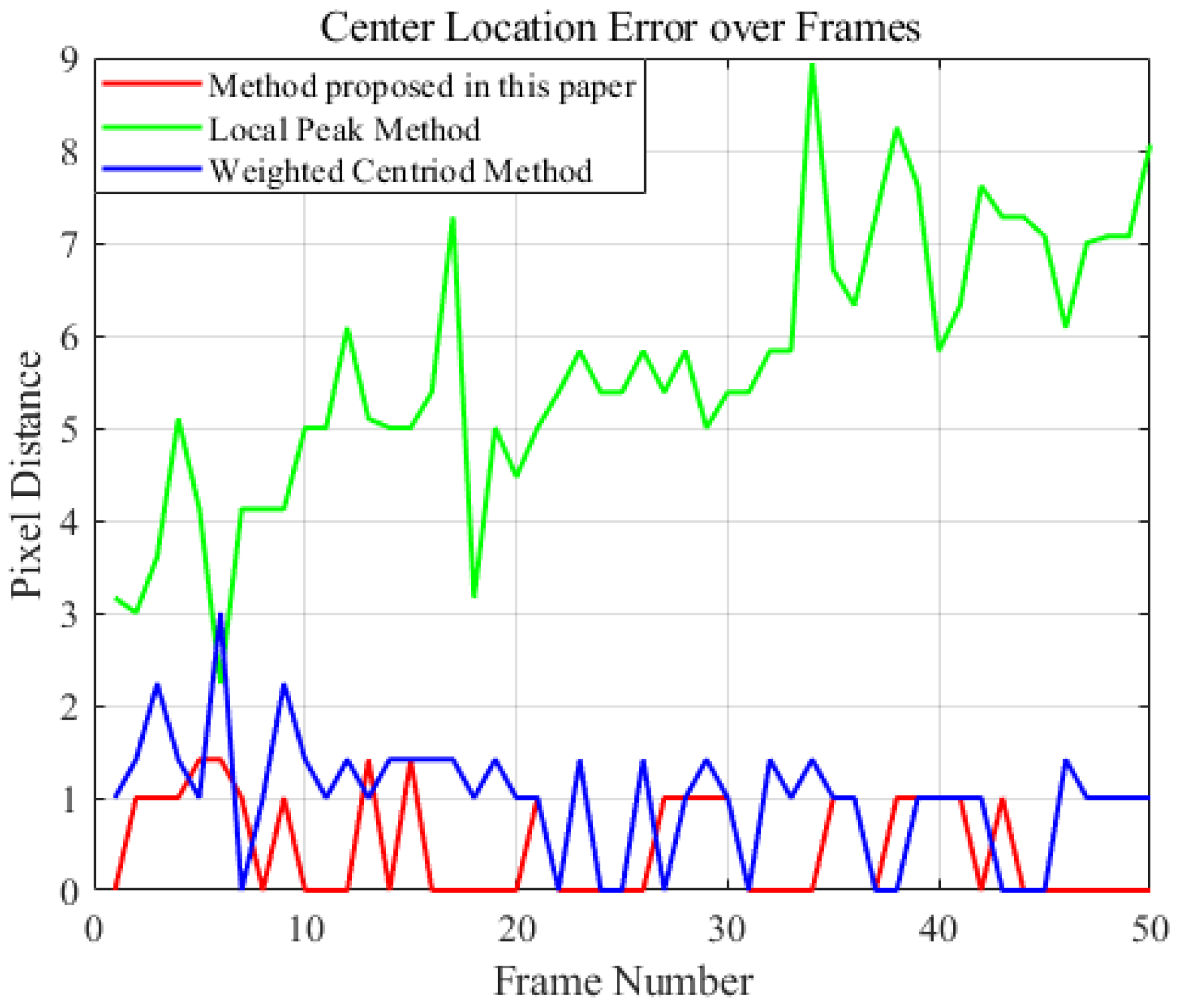

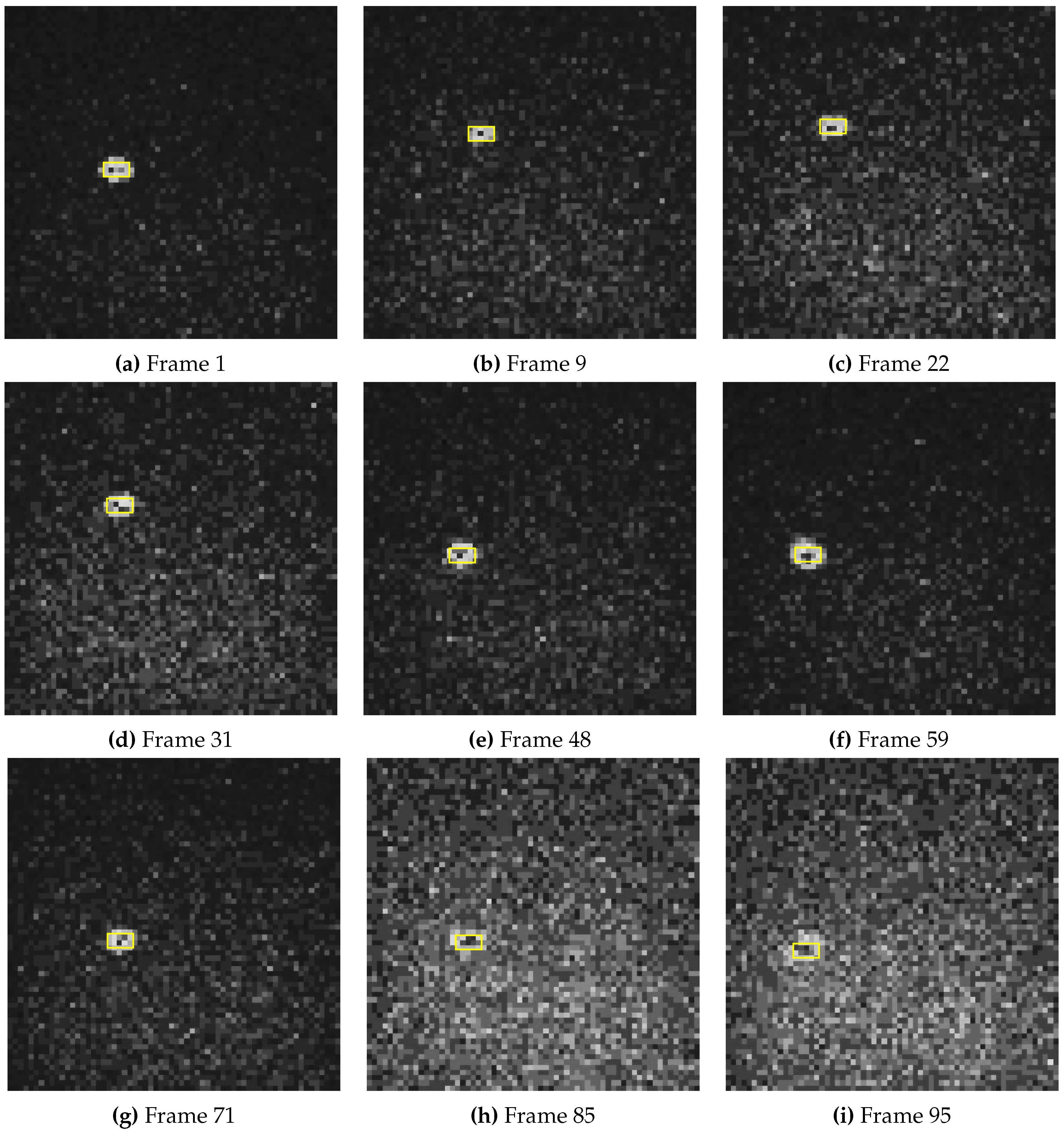

4.1. Estimation Results of Target Tracking Center of Gm-APD LiDAR System

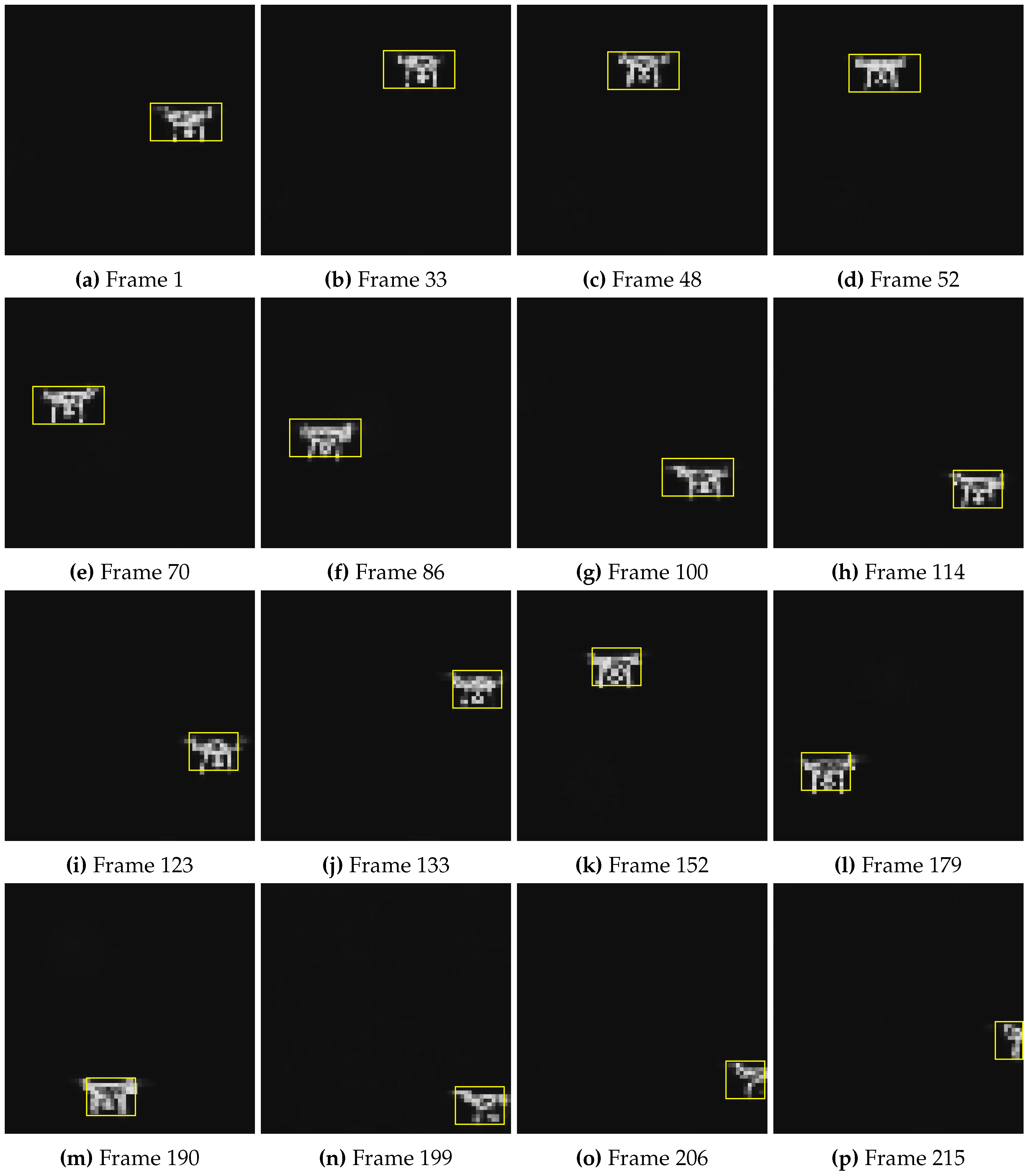

4.2. Results of Tracking Algorithm for Gm-APD LiDAR System

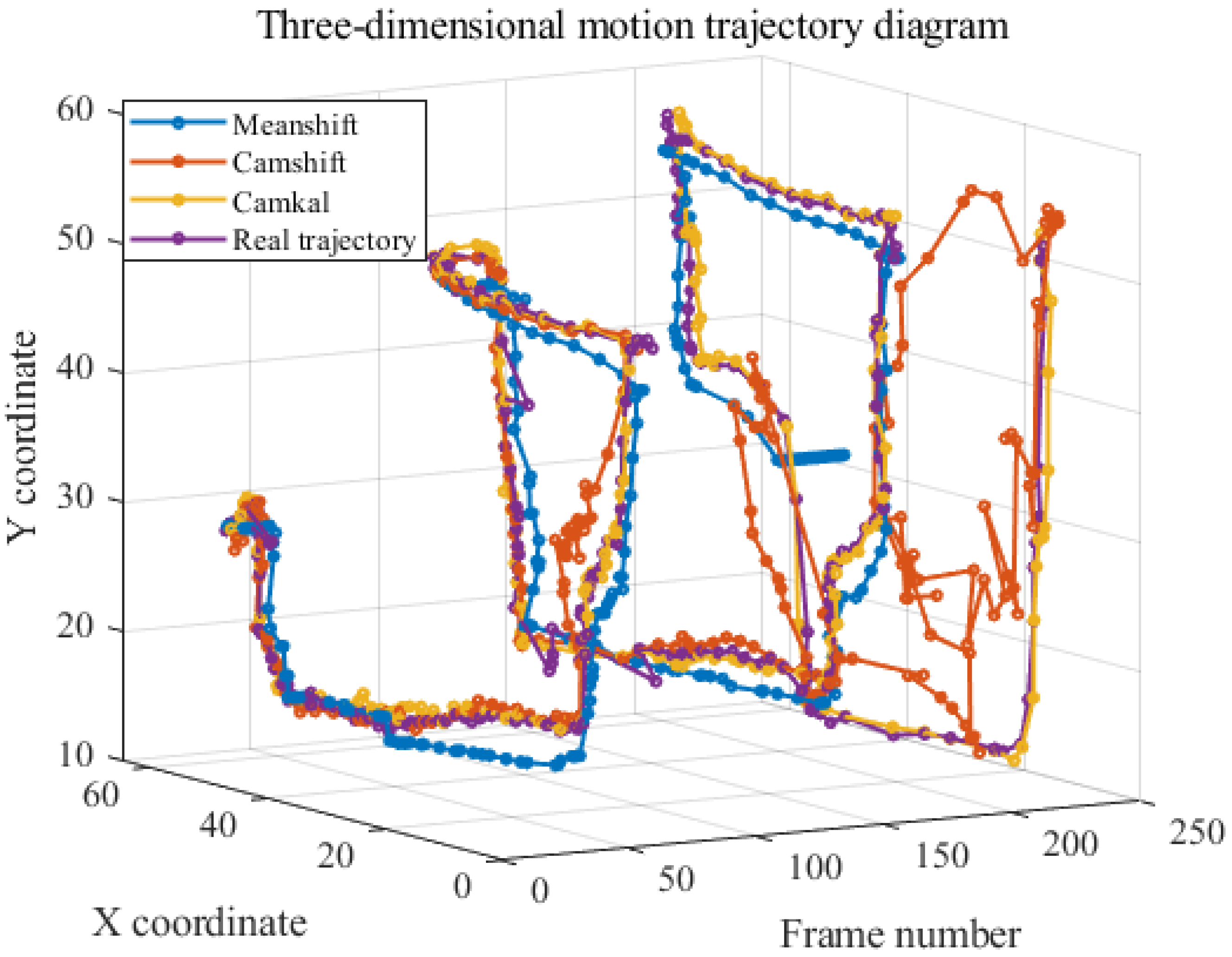

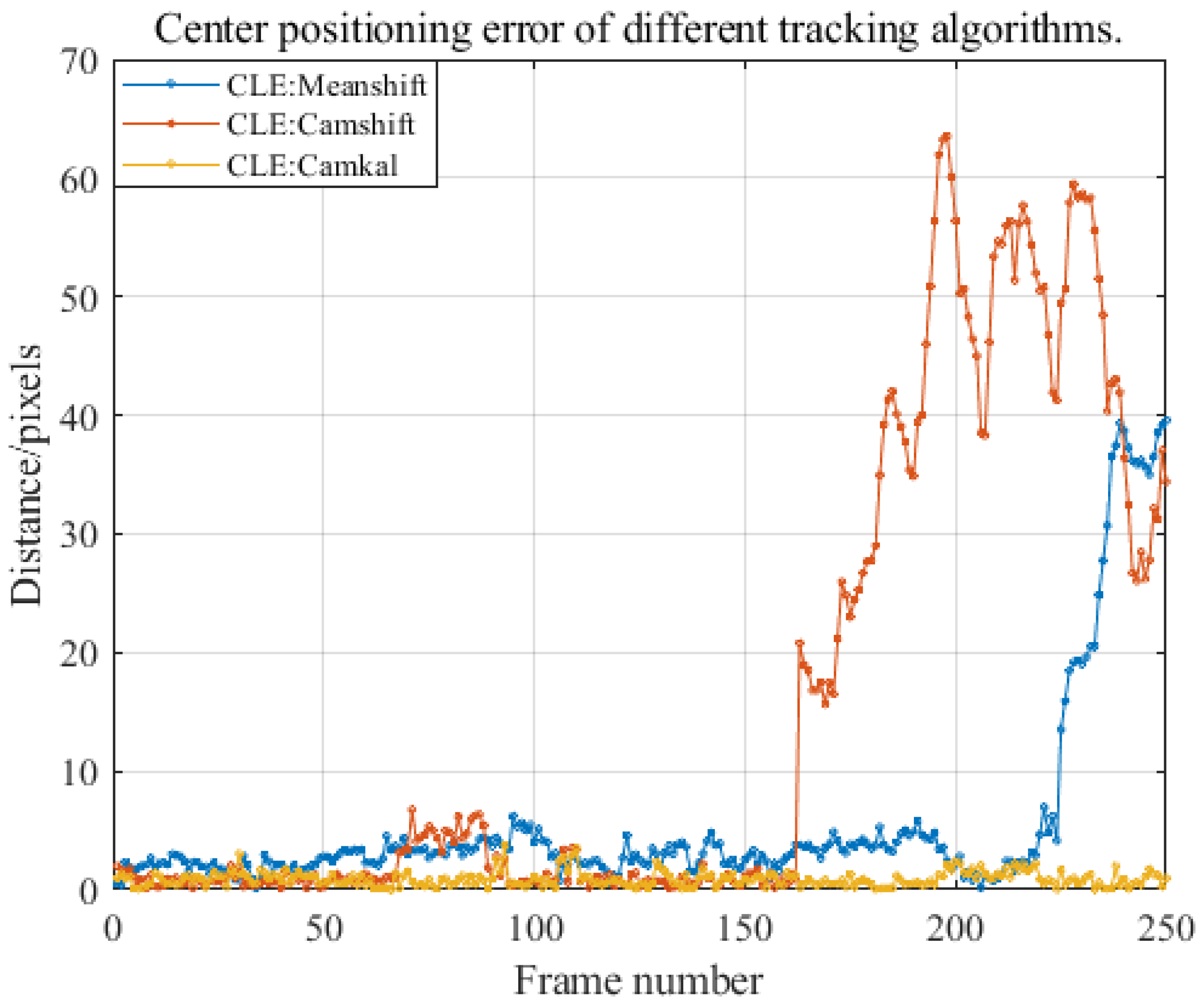

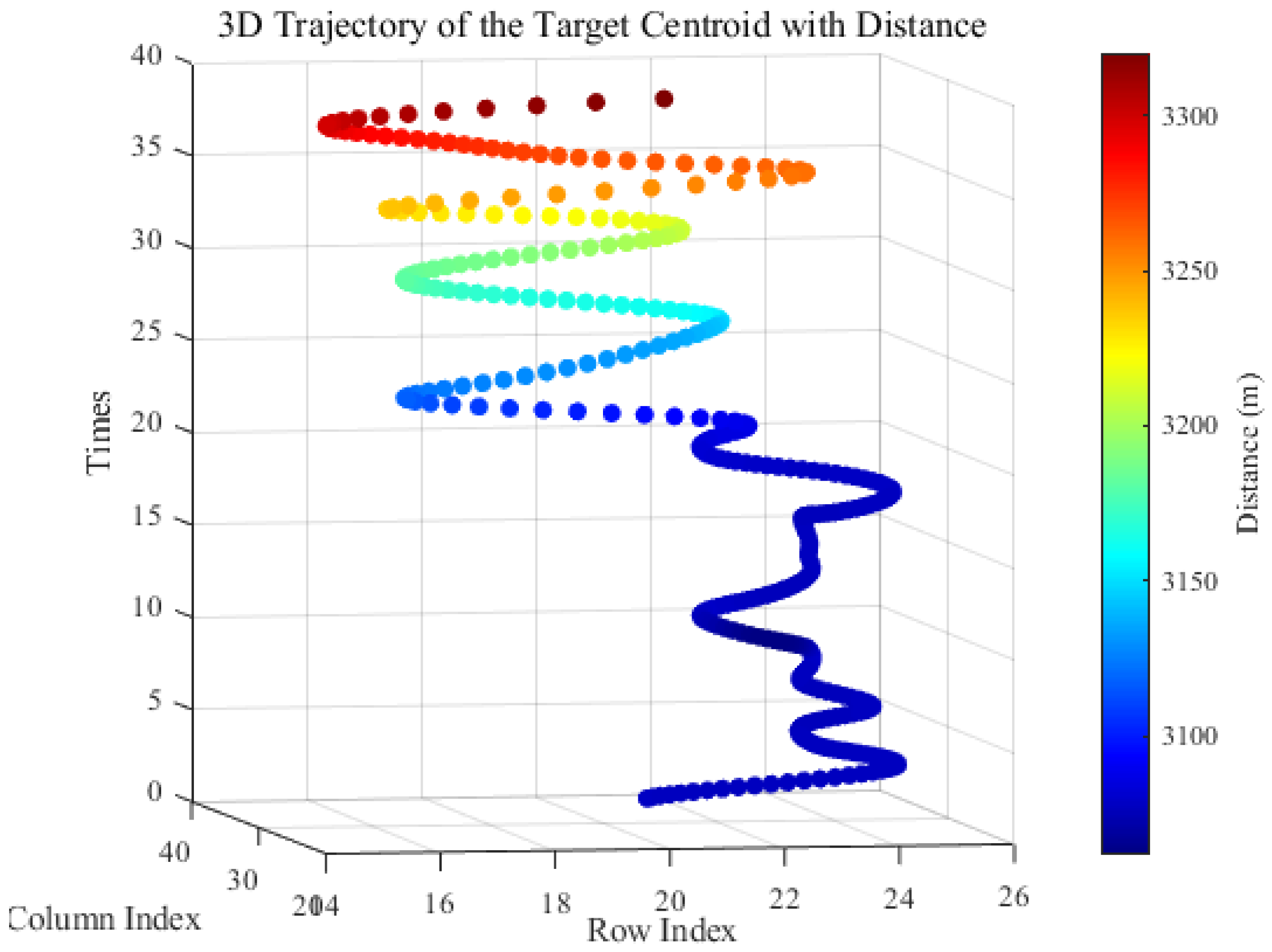

4.3. Long-Distance Tracking Results of Gm-APD LiDAR Based on Cam-Kalm Algorithm

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farlík J, Gacho L. Researching UAV threat–new challenges[C]//2021 International Conference on Military Technologies (ICMT). IEEE, 2021: 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Lyu C, Zhan R. Global analysis of active defense technologies for unmanned aerial vehicle[J]. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, 2022, 37(1): 6-31. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Rao B, Wang W. UAV swarm intelligence: Recent advances and future trends[J]. Ieee Access, 2020, 8: 183856-183878. [CrossRef]

- Mohsan S A H, Khan M A, Noor F, et al. Towards the unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): A comprehensive review[J]. Drones, 2022, 6(6): 147. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Liu Y, Song H. Counter-unmanned aircraft system (s)(C-UAS): State of the art, challenges, and future trends[J]. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, 2021, 36(3): 4-29. [CrossRef]

- Anil A, Hennemann A, Kimmel H, et al. PERSEUS-Post-Emergency Response and Surveillance UAV System[M]. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Luft-und Raumfahrt-Lilienthal-Oberth eV, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bi Z, Chen H, Hu J, et al. Analysis of UAV Typical War Cases and Combat Assessment Research[C]//2022 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS). IEEE, 2022: 1449-1453. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Liu Y, Song H. Counter-unmanned aircraft system (s)(C-UAS): State of the art, challenges, and future trends[J]. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, 2021, 36(3): 4-29. [CrossRef]

- Lykou G, Moustakas D, Gritzalis D. Defending airports from UAS: A survey on cyber-attacks and counter-drone sensing technologies[J]. Sensors, 2020, 20(12): 3537. [CrossRef]

- Park S, Kim H T, Lee S, et al. Survey on anti-drone systems: Components, designs, and challenges[J]. IEEE access, 2021, 9: 42635-42659. [CrossRef]

- McManamon P, F. Review of ladar: a historic, yet emerging, sensor technology with rich phenomenology[J]. Optical Engineering, 2012, 51(6): 060901-060901. [CrossRef]

- Advanced time-correlated single photon counting applications[M]. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Becker W, Bergmann A. Multi-dimensional time-correlated single photon counting[J]. Reviews in fluorescence 2005, 2005: 77-108. [CrossRef]

- Prochazka I, Hamal K, Sopko B. Recent achievements in single photon detectors and their applications[J]. Journal of Modern Optics, 2004, 51(9-10): 1289-1313. [CrossRef]

- Natarajan C M, Tanner M G, Hadfield R H. Superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors: physics and applications[J]. Superconductor science and technology, 2012, 25(6): 063001. [CrossRef]

- Yuan Z L, Kardynal B E, Sharpe A W, et al. High speed single photon detection in the near infrared[J]. Applied Physics Letters, 2007, 91(4). [CrossRef]

- Buller G S, Collins R J. Single-photon generation and detection[J]. Measurement Science and Technology, 2009, 21(1): 012002. [CrossRef]

- Eisaman M D, Fan J, Migdall A, et al. Invited review article: Single-photon sources and detectors[J]. Review of scientific instruments, 2011, 82(7). [CrossRef]

- Fersch T, Weigel R, Koelpin A. Challenges in miniaturized automotive long-range LiDAR system design[C] //Three-Dimensional Imaging, Visualization, and Display 2017. SPIE, 2017, 10219: 160-171. [CrossRef]

- Raj T, Hanim Hashim F, Baseri Huddin A, et al. A survey on LiDAR scanning mechanisms[J]. Electronics, 2020, 9(5): 741. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer N, Briese C. Laser scanning–principles and applications[C]//Geosiberia 2007-international exhibition and scientific congress. European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 2007: cp-59-00077. [CrossRef]

- Kim B H, Khan D, Bohak C, et al. V-RBNN based small drone detection in augmented datasets for 3D LADAR system[J]. Sensors, 2018, 18(11): 3825. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Liu B, Guo G. Adaptive single photon detection under fluctuating background noise[J]. Optics express, 2020, 28(20): 30199-30209. [CrossRef]

- Pfennigbauer M, Möbius B, do Carmo J P. Echo digitizing imaging LiDAR for rendezvous and docking[C]//Laser Radar Technology and Applications XIV. SPIE, 2009, 7323: 9-17. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy A, Ren X, Della Frera A, et al. Kilometer-range depth imaging at 1550 nm wavelength using an InGaAs/InP single-photon avalanche diode detector[J]. Optics express, 2013, 21(19): 22098-22113. [CrossRef]

- Pawlikowska A M, Halimi A, Lamb R A, et al. Single-photon three-dimensional imaging at up to 10 kilometers range[J]. Optics express, 2017, 25(10): 11919-11931. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, He Y, You L, et al. Few-photon imaging at 1550 nm using a low-timing-jitter superconducting nanowire single-photon detector[J]. Optics express, 2015, 23(11): 14603-14611. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Yu Y, Chen Z, et al. True random coded photon counting LiDAR[J]. Opto-Electronic Advances, 2020, 3(2): 190044-1-190044-6. [CrossRef]

- Li Z P, Ye J T, Huang X, et al. Single-photon imaging over 200 km[J]. Optica, 2021, 8(3): 344-349. [CrossRef]

- Kirmani A, Venkatraman D, Shin D, et al. First-photon imaging[J]. Science, 2014, 343(6166): 58-61. [CrossRef]

- Hua K, Liu B, Chen Z, et al. Fast photon-counting imaging with low acquisition time method[J]. IEEE Photonics Journal, 2021, 13(3): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Liu B, Guo G, et al. Single photon imaging with multi-scale time resolution[J]. Optics Express, 2022, 30(10): 15895-15904. [CrossRef]

- Ding Y, Qu Y, Zhang Q, et al. Research on UAV detection technology of Gm-APD LiDAR based on YOLO model[C]//2021 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS). IEEE, 2021: 105-109. [CrossRef]

- Bi H, Ma J, Wang F. An improved particle filter algorithm based on ensemble Kalman filter and Markov chain Monte Carlo method[J]. IEEE journal of selected topics in applied earth observations and remote sensing, 2014, 8(2): 447-459. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni M, Wadekar P, Dagale H. Block division based camshift algorithm for real-time object tracking using distributed smart cameras[C]//2013 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia. IEEE, 2013: 292-296. [CrossRef]

- Yang, P. Efficient particle filter algorithm for ultrasonic sensor-based 2D range-only simultaneous localisation and mapping application[J]. IET Wireless Sensor Systems, 2012, 2(4): 394-401. [CrossRef]

- Cong D, Shi P, Zhou D. An improved camshift algorithm based on RGB histogram equalization[C]//2014 7th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing. IEEE, 2014: 426-430. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Zhang H, Luo M, et al. Research on target echo characteristics and ranging accuracy for laser radar[J]. Infrared Physics & Technology, 2019, 96: 330-339. [CrossRef]

- Chauve A, Mallet C, Bretar F, et al. Processing full-waveform lidar data: modelling raw signals[J]. International archives of photogrammetry, remote sensing and spatial information sciences, 2007, 36(part 3): W52.

- Laurenzis M, Bacher E, Christnacher F. Measuring laser reflection cross-sections of small unmanned aerial vehicles for laser detection, ranging and tracking[C]//Laser Radar Technology and Applications XXII. SPIE, 2017, 10191: 74-82. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Detection and tracking of human motion targets in video images based on Camshift algorithms[J]. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2019, 20(20): 11887-11893. [CrossRef]

- Bankar R, Salankar S. Improvement of head gesture recognition using Camshift based face tracking with UKF[C]//2019 9th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology-Signal and Information Processing (ICETET-SIP-19). IEEE, 2019: 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zhang Y, Shen S, et al. Research and application of police UAVs target tracking based on improved Camshift algorithm[C]//2019 3rd International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering (EITCE). IEEE, 2019: 1238-1242. [CrossRef]

- Nishiguchi K I, Kobayashi M, Ichikawa A. Small target detection from image sequences using recursive max filter[C]//Signal and Data Processing of Small Targets 1995. SPIE, 1995, 2561: 153-166. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Detection and tracking of human motion targets in video images based on Camshift algorithms[J]. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2019, 20(20): 11887-11893. [CrossRef]

- Solanki P B, Al-Rubaiai M, Tan X. Extended Kalman filter-based active alignment control for LED optical communication[J]. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 2018, 23(4): 1501-1511. [CrossRef]

- Exner D, Bruns E, Kurz D, et al. Fast and robust Camshift tracking[C]//2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition-Workshops. IEEE, 2010: 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Guo G, Zhao S. 3D multi-object tracking with adaptive cubature Kalman filter for autonomous driving[J]. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, 2022, 8(1): 512-519. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Bian C, Chen H. Object tracking in satellite videos: Correlation particle filter tracking method with motion estimation by Kalman filter[J]. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2022, 60: 1-12. [CrossRef]

| Fitting method | MSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Local peak | 17.08 | -5.1084 |

| Centroid weighting | 0.70 | 0.7569 |

| Proposed in this paper | 0.25 | 0.9143 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).