Submitted:

17 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Citizen Science Recruitment

2.3. Estuaries Studied

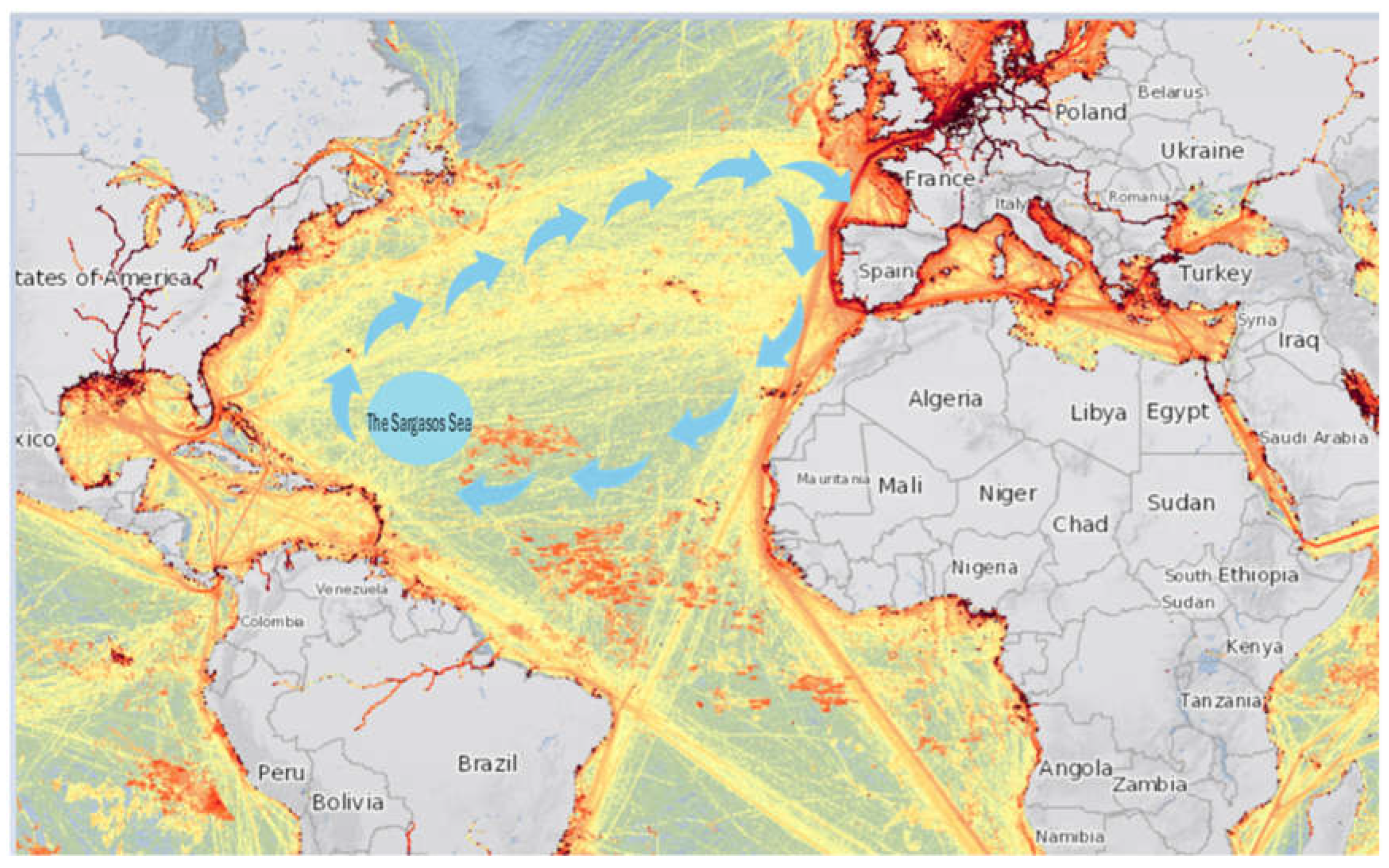

2.4. Maritime Traffic Records

2.5. Post-Activity Survey

2.6. Data Curation

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

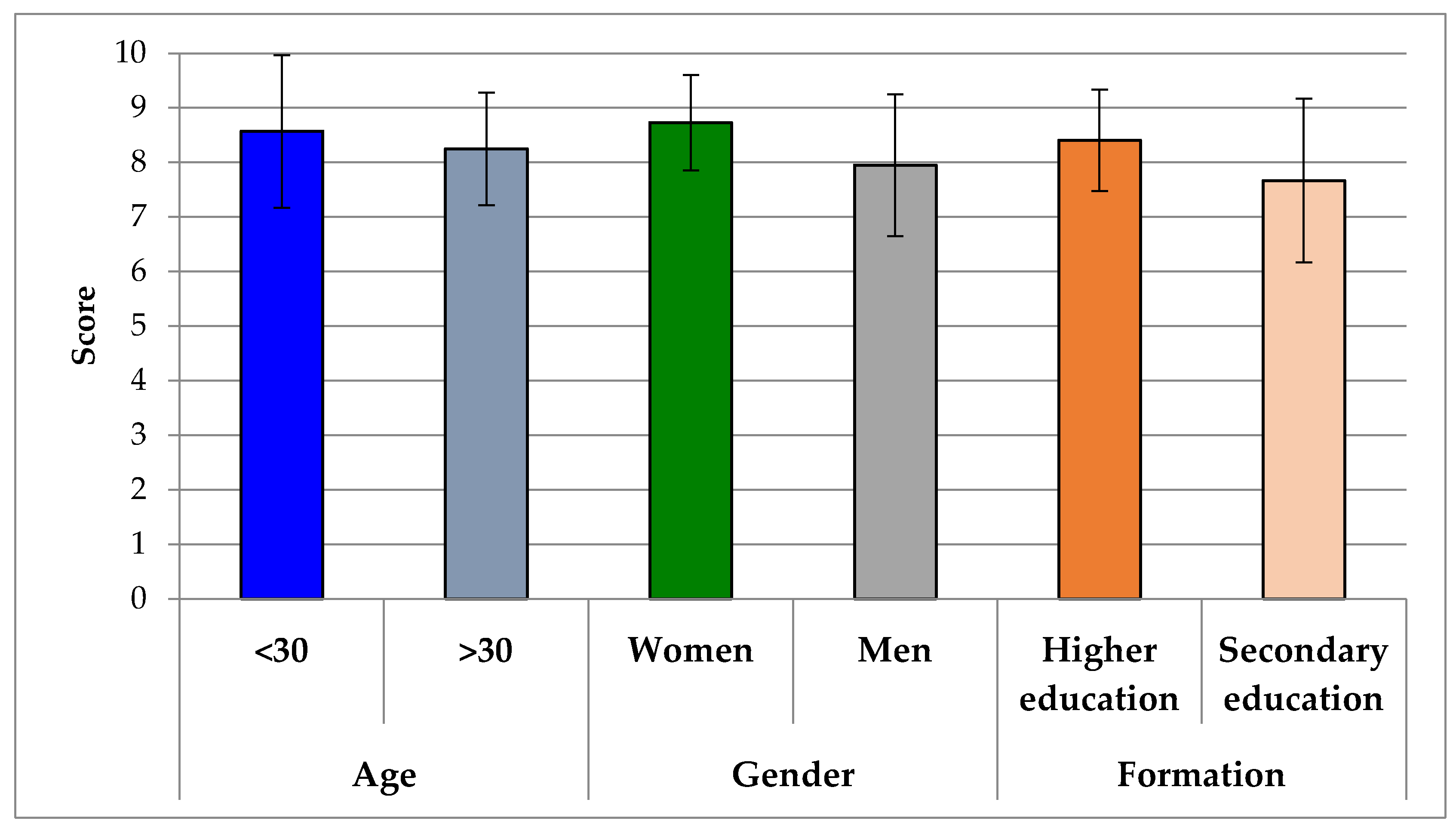

3.1. Citizen Science Performance And Volunteer Satisfaction

3.2. Maritime Traffic Recorded In The Studied Estuaries

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNCTAD. Review of maritime transport 2023. Towards a green and just green and just transition transition. United Nations Publications, New York, 2023. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/rmt2023_en.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Sardain, A.; Sardain, E.; Leung, B. Global forecasts of shipping traffic and biological invasions to 2050. Nat Sustain 2019, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, S.V.; Kessel, S.T. , Espinoza, M., McLean, M.F.; O'Neill, C., Landry, J., Hussey, N.E., Williams, R.; Vagle, S.; Fisk, A.T. Shipping alters the movement and behavior of Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida), a keystone fish in Arctic marine ecosystems. Ecol Appl 2020, 30, e02050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, A.; Whitfield, A. , Cowley, P.; Järnegren, J.; Næsje, T. Does boat traffic cause displacement of fish in estuaries? Mar Pollut Bull 2013, 75, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Correa, J.M.; Bayle Sempere, J-T.; Juanes, F.; Rountree, R.; Ruíz, J.F.; Ramis, J. Recreational boat traffic effects on fish assemblages: First evidence of detrimental consequences at regulated mooring zones in sensitive marine areas detected by passive acoustics. Ocean Coast Manag 2019, 168, 22–34. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.A.; Van Parijs, S.M.; Hatch, L.T. Underwater sound from vessel traffic reduces the effective communication range in Atlantic cod and haddock. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 14633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, J. The foraging specialisms, movement and migratory behaviour of the European Eel, PhD thesis. University of Glasgow, Scotland, 2015.

- Dekker, W. Management of the eel is slipping through our hands! Distribute control and orchestrate national protection. ICES J Mar Sci 2016, 73, 2442–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, C.; Crook, V.; Gollock, M. Anguilla anguilla. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: E.T60344A152845178. https://www.fishsec.org/app/uploads/2022/11/200709-Assessment-10.2305_IUCN.UK_.2020-2.RLTS_.T60344A152845178.en_.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

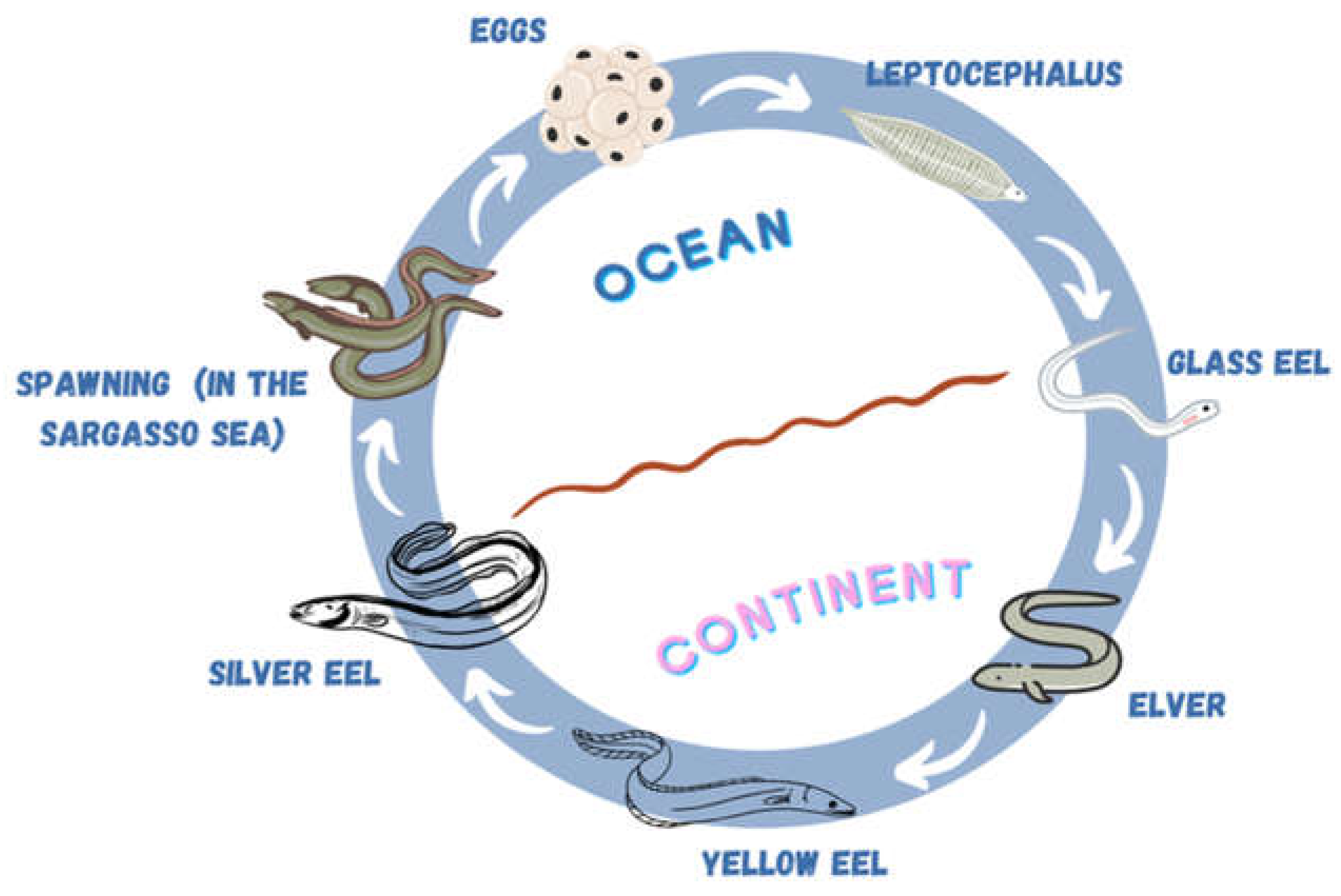

- McDowall, R.M. Diadromy in fishes: Migration between freshwater and marine environments. Timber press, Oregon, USA, 1988; pp. 308.

- https://globalmaritimetraffic.org/. (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Daverat, F.; Lanceleur, L.; Pécheyran, C.; Eon, M.; Dublon, J.; Pierre, M.; Schäfer, J.; Baudrimont, M.; Renault, S. Accumulation of Mn, Co, Zn, Rb, Cd, Sn, Ba, Sr, and Pb in the otoliths and tissues of eel (Anguilla anguilla) following long-term exposure in an estuarine environment. Sci Total Environ 2012, 437, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durif, C.; Dufour, S.; Elie, P. The silvering process of Anguilla anguilla: A new classification from the yellow resident to the silver migrating stage. J Fish Biol 2005, 66, 1025–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesch, F. W.; Thorpe, J.E. (Eds.). The eel. Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK, 2003. pp. 1–408.

- Cresci, A. A comprehensive hypothesis on the migration of European glass eels (Anguilla anguilla). Biol Rev 2020, 95, 1273–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podda, C.; Palmas, F.; Pusceddu, A.; Sabatini, A. Hard times for catadromous fish: The case of the European eel Anguilla anguilla (L. 1758). Adv Oceanog Limnol 2021, 12, 9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICES. 2023. European eel (Anguilla anguilla) throughout its natural range. In Report of the ICES Advisory Committee, 2023. ICES Advice 2023, ele.2737.nea. [CrossRef]

- Dekker, W.; Casselman, J.M. The 2003 Québec Declaration of concern about eel declines - 11 years later: Are eels climbing back up the slippery slope? Fisheries 2014, 39, 613–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouineau, H.; Durif, C.; Castonguay, M.; Mateo, M.; Rochard, E. , Verreault, G.; Yokouchi, K.; Lambert, P. Freshwater eels: A symbol of the effects of global change. Fish Fish 2018, 19, 903–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European eel management plan in Spain, 2010. Secretaría General del Mar, Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino del Gobierno de España (MARM). Gobierno de España. https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/pesca/temas/planes-de-gestion-y-recuperacion-de-especies/plan%20de%20gesti%C3%B3n%20anguila_Espa%C3%B1a_tcm30-282062.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Eel Management Plan of Andalusia, 2010. Consejería de Agricultura y Pesca, Consejería de Medio Ambiente. https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/export/drupaljda/PGA_Andalucia.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2024). (accessed on null).

- Clavero, M.; Hermoso, V. Historical data to plan the recovery of the European Eel. J. Applied Ecol 2015, 52, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decree 396/2010. 2010, November 2. Laying down measures for the recovery of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). Retrieved from https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2010/221/2 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Decree 209/2020. 2020, December 9. Laying down measures for the recovery of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). https://laadministracionaldia.inap.es/noticia.asp?id=1205885 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Erbe, C.; Smith, J.N.; Redfern, J.V.; Peel, D. Editorial: Impacts of Shipping on Marine Fauna. Front Mar Sci 2020, 7, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purser, J.; Bruintjes, R.; Simpson, S.D.; Radford, A.N. Condition-dependent physiological and behavioural responses to anthropogenic noise. Physiol Behav 2016, 155, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durif, C.M.F.; Arts, M.; Bertolini, F.; Cresci, A.; Daverat, F.; Karlsbakk, E.; Koprivnikar, J.; Moland, E.; Olsen, E.M.; Parzanini, C.; Power, M.; Rohtla, M.; Skiftesvik, A.B.; Thorstad, E.; Vøllestad, L.A.; Browman, H.I. The evolving story of catadromy in the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). J Mar Sci 2023, 80, 2253–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopico, E.; Ardura, A.; Borrell, Y. J.; Miralles, L.; García-Vázquez, E. Boosting adults scientific literacy with experiential learning practices. Eu J Res Educ Learn Adults 2021, 12, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Ethics for researchers – Facilitating research excellence in FP7, Publications Office, 2013. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/7491 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- ALLEA. The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity – Revised Edition 2023. All European Academies, Berlin, 2023.

- Valerio, M.A.; Rodriguez, N.; Winkler, P.; Lopez, J.; Dennison, M.; Liang, Y.; Turner, B. J. Comparing two sampling methods to engage hard-to-reach communities in research priority setting. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 2016, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraisl, D. , Hager, G., Bedessem, B.; Margaret Gold, M.; Hsing, P.H.; Danielsen, F.; Hitchcock, C.B.; Joseph M. Hulbert, J.M.; Piera, J.; Spiers, H.; Thiel, M.; Haklay, M. Citizen science in environmental and ecological sciences. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2022, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.marinetraffic.com (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/AIS.aspx (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. Available online: http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Rivas-Iglesias, L.; Garcia-Vazquez, E.; Soto-López, V. Maritime traffic from the Asturian coast. 2024. https://b2share.eudat.eu. (accessed on 1 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ardura, A.; Dopico, E.; Fernandez, S.; Garcia-Vazquez, E. . Citizen volunteers detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA from outdoor urban fomites. Sci. Total Environ 2021, 787, 147719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, N. V.; Dubey, A.; Millar, E.; Nava, V.; Leoni, B.; Gallego, I. Monitoring contaminants of emerging concern in aquatic systems through the lens of citizen science. Sci Total Environ 2023, 874, 162527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannino, A.M.; Borfecchia, F.; Micheli, C. Tracking Marine Alien Macroalgae in the Mediterranean Sea: The Contribution of Citizen Science and Remote Sensing. J Mar Sci Eng 2021, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlino, S.; Locritani, M.; Guarnieri, A.; Delrosso, D.; Bianucci, M.; Paterni, M. Marine Litter Tracking System: A Case Study with Open-Source Technology and a Citizen Science-Based Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppari, M.; Roveta, C.; Di Camillo, C.; Garrabou, J.; Lucrezi, S.; Pulido Mantas, T.; Cerrano, C. The pillars of the sea: Strategies to achieve successful marine citizen science programs in the Mediterranean area. BMC Ecol Evol 2024, 24, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, B.; Mooney, P.; Nováková, E.; Bastin, L.; Arsanjani, J. J. (2021). Data quality in citizen science. In The science of citizen science; Vohland, K.; Land-Zandstra, A.; Ceccaroni, L.; Lemmens, R.; Perelló, J.; Ponti, M.; Samson, R.; Wagenknecht, K.; Springer, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 139– 158.

- Freschi, G.; Menegatto, M.; Zamperini, A. Conceptualising the Link between Citizen Science and Climate Governance: A Systematic Review. Climate 2024, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjichambis, A.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Georgiou, Y.; Adamou, A. How can we transform citizens into ‘environmental agents of change'? Towards the citizen science for environmental citizenship (CS4EC) theoretical framework based on a meta-synthesis approach. Int J Sci Educ 2024, 14 Pt B, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleau, M. J.; White, P. R.; Peirson, G.; Leighton, T. G.; Kemp, P. S. Use of acoustics to enhance the efficiency of physical screens designed to protect downstream moving European eel (Anguilla anguilla). Fish Managt Ecol 2020, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.R.; Adebambo, O.; Del Aguila Feijoo, M.C.; Elhaimer, E.; Hossain, T.; Edwards, S.J.; Morrison, C.E.; Romo, J.; Sharma, N.; Taylor, S.; Zomorodi, S. Environmental Effects of Marine Transportation. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation; Sheppard, C. Ed.; Elsevier, Netherlands, 2019; pp. 505–530.

- Turan, F.; Karan, S.; Ergenler, A. Effect of heavy metals on toxicogenetic damage of European eels Anguilla anguilla. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 38047–38055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, R.J.; Paukert, C.P.; Aarestrup, K.; Auger-Méthé, M.; Baumgartner, L.; Birnie-Gauvin, K.; Boe, K.; Brink, K.; Brownscombe, J.W.; Chen, Y., Davidsen, J.G.; Eliason, E.J.; Filous, A.; Gillanders, B.M.; Helland, I.P.; Horodysky, A.Z.; Januchowski-Hartley, S.R.; Lowerre-Barbieri, S.K.; Lucas, M.C.; Martins, E.G.; Murchie, K.J.; Pompeu, P.S.; Power, M.; Raghavan, R.; Rahel, F.J.; Secor, D.; Thiem, J.D.; Thorstad, E.B.; Ueda, H.; Whoriskey, F.G.; Cooke, S.J. One hundred pressing questions on the future of global fish migration science, conservation and policy. Front Ecol Evol 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Popper, A.N.; Hastings, M.C. The effects of anthropogenic sources of sound on fishes. J Fish Biol 2009, 75, 455–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, C.; Marley, S.A.; Schoeman, R.P.; Smith, J.N.; Trigg, L.E. , Embling, C.B. The effects of ship noise on marine mammals – A review. Front Mar Sci 2019, 6, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, R.P.; Patterson-Abrolat, C.; Plön, S. A global review of vessel collisions with marine animals. Front Mar Sci 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Cavallaro, L.; Castro, E.; Musumeci, R.E.; Martignoni, M.; Roman, F.; Foti, E. New frontiers in the risk assessment of ship collision. Ocean Eng 2023, 274, 113999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laist, D.W.; Knowlton, A.R.; Mead, J.G.; Collet, A.S.; Podesta, M. Collisions between ships and whales. Mar Mammal Sci 2006, 17, 35–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sèbe, M.; David, L.; Dhermain, F.; Gourguet, S.; Madon, B.; Ody, D.; Panigada, S.; Peltier, H.; Pendleton, L. Estimating the impact of ship strikes on the Mediterranean fin whale subpopulation. Ocean Coast Manag 2023, 237, 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Matchinski, E.J.: B.C..; Chen, B.; Xundong. Y.; Jing, L.; Lee, K. Marine oil spills – oil pollution, sources and effects. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation, Sheppard, C. Ed; Elsevier, Netherlands, 2019; pp. 391–406.

- Verhelst, P.; Reubens, J.; Buysse, D.; Goethals, P.; Van Wichelen, J.; Moens, T. Toward a roadmap for diadromous fish conservation: The Big Five considerations. Front Ecol Environ 2021, 19, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua, D.; Meliá, P.; Gatto, M.; De Leo, G.A. A global viability assessment of the European eel. Glob Chang Biol 2015, 21, 3323–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, R.; Honkanen, H.M.; Lilly, J.; Green, A.; Rodger, J.R.; Shields, B.A.; Ramsden, P.; Koene, J.P.; Fletcher, M. , Bean, C.W., Adams, C.W. The effect of downstream translocation on Atlantic salmon Salmo salar smolt outmigration success. J Fish Biol 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komyakova, V.; Jaffrés, J.B.D.; Strain, E.M.A.; Cullen-Knox, C.; Fudge, M.; Langhamer, O. , Bender, A. ; Yaakub, S.M., Wilson, E.; Allan, B.J.M., Sella, I., Haward, M. Conceptualisation of multiple impacts interacting in the marine environment using marine infrastructure as an example. Sci Tot Environ 2022, 830, 154748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, N.; Williamson, A.; Aguero, M.; González Poblete, E.; Geeves, W. 2003. Marine invasive alien species: A threat to global biodiversity. Mar Pol 2003, 27, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, J.L.; Gamboa, R.L.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M.D. Assessing the global threat of invasive species to marine biodiversity. Front Ecol Environ 2008, 6, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayon-Viña, F.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, S.; Ibabe, A.; Dopico, E.; Garcia-Vazquez, E. Public awareness of beach litter and alien invasions: Implications for early detection and management. Ocean Coast Manag 2022, 219, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Estuary | Coordinates | River length (km) | Number and type of ports |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nalón | 43º 33’ 53” N 6º 04’ 36” W |

140.8 | Two fishing ports |

| Sella | 43º 28’ 02” N 5º 03’ 51” W |

66 | A fishing port and a marina |

| Ria of Avilés | 43º 35’ 34” N 5º 56’ 08” W |

22.1 | A fishing port and a marina |

| Odelouca | 37º 10’ 38” N 8º 29’ 07” W |

92.5 | A marina |

| Guadiana | 39º 07’ 54” N 3º 43’ 59” W |

865 | Two fishing ports and three recreational ports |

| Guadalhorce | 36º 39’ 58” N 4º 27’ 18” W |

154 | A fishing, commercial and recreational port |

| Vessel Type | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| ME (Merchant vessels) | Bull carrier; Oil/Chemical tanker; Container; Crude oil tanker; LPG tanker; Ro-Ro/Passenger ship; General cargo; Cargo vessel; Chemical vessel; Container cargo; Container ship; Container vessel; Vehicles carrier |

| FI (Fishing vessels) | Trawler; Fishing; Fishing vessel |

| SC (Special Craft vessels) | Special craft; Sailing vessel; Recreational craft; Yacht; Firefighting vessel; SAR |

| PA (Passenger vessels) | Passenger |

| NC (Naval vessels) | Naval craft; Maritime ops |

| Iberian coast | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of vessel | North | South |

| Cargo | 0.255 | 0.054 |

| Fishing boat | 0.136 | 0.304 |

| Special craft + sailing + recreational | 0.609 | 0.579 |

| Passengers vesel | 0 | 0.058 |

| Naval craft | 0 | 0.006 |

| N | 3962 | 11256 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).