1. Introduction

Shadow fleets, operating beneath the veil of international legality, have long been a clandestine feature of global maritime commerce. While not a new phenomenon, these fleets have gained unprecedented prominence and scale in recent years, particularly in the wake of recent geopolitical events and international sanctions. The International Maritime Organization [

1] defines "dark fleet" or "shadow fleet" as:

Ships engaged in illegal operations aimed at circumventing sanctions, evading compliance with safety or environmental regulations, avoiding insurance costs, or engaging in other illegal activities. These activities may include carrying out unsafe operations that do not adhere to international regulations, well-established industry standards, and best practices. Ships in these fleets intentionally avoid flag State and port State control inspections, as well as commercial screenings or inspections. They often fail to maintain adequate liability insurance or other financial security. A key characteristic of dark or shadow fleet ships is their deliberate effort to avoid detection, often by switching off their Automatic Identification System (AIS) or Long-Range Identification and Tracking (LRIT) transmissions, or by concealing the ship's actual identity when there is no legitimate safety or security concern sufficient to justify such action.

This comprehensive definition underscores the multifaceted nature of shadow fleet operations and the various ways in which these vessels operate outside of international norms and regulations. The use of subterfuge tankers is not new in the oil trade, with similar tactics observed in Iranian and Venezuelan oil exports, providing historical precedents for current operations [

2], [

3].

This research addresses the gap through analysis of multiple empirical cases from 2022-2024, a period marked by unprecedented expansion of shadow fleet activities following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Our investigation examines established sanctions evasion tactics while documenting new operational patterns that emerged in response to international sanctions. As mainstream shipping companies and insurers withdrew from Russian oil trade to comply with Western restrictions, a new ecosystem of opaque operators emerged to facilitate Russian sanctions evasion on an unprecedented scale [

4], [

5], [

6].

Despite the growing significance of shadow fleets in global maritime trade, a critical research gap persists in the precise definition and categorization of this evolving phenomenon. The recent geopolitical events have not only expanded the scale of shadow fleet operations but have also diversified their nature and tactics, outpacing existing conceptual frameworks.

This research addresses this gap through analysis of multiple empirical cases from 2022-2024, a period marked by unprecedented expansion of shadow fleet activities following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Our investigation examines established sanctions evasion tactics while documenting new operational patterns that emerged in response to international sanctions. Through systematic surveillance and case study analysis, we demonstrate how shadow fleet operations have evolved from isolated instances of sanctions evasion to industrial-scale networks of vessels operating outside regulatory frameworks.

To address this gap, our research proposes an innovative conceptual framework that introduces a more nuanced definition of shadow fleets. We posit that the term 'shadow fleet' encompasses a spectrum of covert maritime activities, which can be primarily distinguished between 'dark fleets' and 'gray fleets'. This distinction is crucial in understanding the varying degrees of illicit activities and the complex strategies employed by these vessels.

"Dark fleets" and "gray fleets" represent two distinct categories of covert maritime operations that operate outside or within the fringes of international regulations. "Dark fleets" are vessels that engage in wholly illicit activities, deliberately avoiding detection and compliance by disabling their Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmitters, falsifying documentation, and frequently changing flags to evade regulatory oversight. These ships operate completely outside legal frameworks, often involved in activities such as sanctions evasion, illegal trade, and unregulated fishing. In contrast, "gray fleets" exploit legal ambiguities and regulatory loopholes to operate in a zone of questionable legality. While these vessels generally maintain active AIS transmitters and adhere to a semblance of compliance, they manipulate data and engage in practices that skirt the edges of international law. "Gray fleets" typically conduct operations that, although not entirely illegal, push the boundaries of legal acceptability, thereby complicating enforcement efforts. Understanding the nuances between these two types of fleets is essential for developing effective strategies to address the challenges they pose to global maritime governance.

This pioneering approach allows for a more sophisticated analysis of shadow fleet operations, recognizing that not all covert maritime activities are equally illicit or operate in the same manner. By examining the nuances between these two newly defined subsets of shadow fleet operations, we seek to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges posed by shadow fleets in global maritime commerce and their role in broader geopolitical strategies. Our research aims to contribute significantly to the field by providing this more refined tool for analyzing and addressing the complex issues surrounding these clandestine activities.

2. Methodology

The paucity of academic literature specifically addressing shadow fleets reflects both the clandestine nature of these operations and their relatively recent prominence in global maritime affairs. Our temporal framework focuses on 2022-2024, capturing the dramatic shift in shadow fleet operations following the implementation of the Russian Oil Price Cap in December 2022. This period documents both the rapid expansion of shadow fleet capabilities and the evolution of evasion tactics from individual vessels to coordinated networks. To mitigate the limitations imposed by the scarcity of academic sources, this research heavily relies on primary sources, expert consultations, and contemporary case studies. While this lacuna in prior research presents certain constraints, it simultaneously offers an opportunity for this study to make a substantive contribution to the nascent field of shadow fleet analysis.

To elucidate the intricate operations of shadow fleets and their covert maritime activities, we have developed a comprehensive and methodical approach that synthesizes historical analysis, contemporary case studies, and cutting-edge technological insights. This dual-faceted methodology integrates a thorough examination of extant scholarly literature with detailed case studies, complemented by an extensive data collection process enhanced by modern technological advancements. Throughout this process, we have incorporated the invaluable perspectives of subject matter experts. This multidimensional strategy facilitates a profound examination of shadow fleets, illuminating their operational methodologies, strategic objectives, and the technological innovations that underpin their covert operations.

Integrated Methodological Approach: Literature Review, Case Studies, and Data Analysis

The selection and analysis of case studies followed a rigorous methodological framework designed to ensure comprehensive coverage of shadow fleet operations while maintaining analytical rigor. Our research draws from an extensive database of vessels identified as operating in dark or gray fleet capacities between 2022-2024. The selection methodology considered multiple vessel types and operational modalities, requiring verified documentation and data to support analysis. From this comprehensive dataset, we selected representative cases for detailed presentation that best exemplify the distinctive characteristics of dark and gray fleets. These cases were chosen based on the clarity of documentation, completeness of tracking data, evidence of multiple evasion tactics, and their ability to demonstrate typical operational patterns observed across the larger dataset.

Our analysis integrated a comprehensive data collection framework incorporating both primary and secondary sources. Primary sources included satellite imagery analysis, AIS tracking data. These were complemented by secondary sources encompassing industry reports, academic literature, investigative journalism, expert interviews, and government documentation. This multi-layered approach enabled thorough verification and cross-referencing of findings.

The analytical protocol proceeded through several distinct phases. Initial case identification emerged from systematic review of media reports, industry alerts, regulatory enforcement notices, and expert recommendations. From our database, we identified the M/V Wise Honest, ANITA, and OLIVE as archetypal examples of dark fleet operations, demonstrating comprehensive regulatory evasion. For gray fleet operations, we selected ADVANTAGE ANGEL and STI DUCHESSA as they exemplify the nuanced approach of maintaining partial compliance while engaging in sanctioned trade. The verification process involved rigorous cross-referencing of multiple independent data sources, coupled with expert consultation and comprehensive documentation review. This verification phase proved crucial in establishing the validity of identified patterns and operational characteristics.

3. Dark Fleet and Gray Fleet: A Comparative Analysis

The proliferation of shadow fleets in global maritime commerce necessitates a nuanced understanding of their operational modalities. This section proposes a dichotomous classification of shadow fleets into 'Dark Fleets' and 'Gray Fleets', examining their distinct characteristics, operational strategies, and implications for international maritime governance.

3.1. Subsection Dark Fleet: Characteristics and Operation

Analysis of specific vessels reveals sophisticated patterns of regulatory evasion and detection avoidance. North Korea has pioneered many of the tactics now employed by larger shadow fleets. A primary feature of Dark Fleet operations is the systematic manipulation of Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmitters. This practice, which contravenes international maritime safety protocols, involves disabling AIS systems to evade tracking and monitoring efforts [

1]. Complementing this tactic is the employment of various deceptive practices, including the falsification of documentation and cargo manifests, further obfuscating the true nature of their activities.

Another key characteristic of the Dark Fleet is the practice of 'flag hopping'. This involves frequent changes in vessel registration to jurisdictions with lenient regulatory frameworks, commonly referred to as 'flags of convenience' [

7], [

8]. Such practices enable these vessels to exploit regulatory loopholes and operate with minimal oversight. Furthermore, the Dark Fleet is notable for its opaque ownership structures. The utilization of complex corporate arrangements serves to obscure true ownership, significantly impeding accountability and complicating efforts to enforce regulations or impose sanctions [

9].

North Korea has pioneered many of the tactics now employed by larger shadow fleets. For example, the M/V Wise Honest (IMO: 8905490), seized by U.S. authorities in 2019, exemplifies sophisticated sanctions evasion. This 17,061-ton bulk carrier systematically disabled its AIS transmitter while conducting ship-to-ship transfers of coal and receiving refined petroleum products. The vessel used a complex network of front companies, including Korea Songi Shipping Company, to obscure its ownership and operations. This case highlighted how dark fleets combine multiple evasion tactics: AIS manipulation, fraudulent documentation, and complex ownership structures [

10], [

11]

Further empirical evidence of dark fleet operations can be found in the documented activities of vessels such as the ANITA (IMO: 9203253), registered under the Sudanese flag. This vessel exemplifies the comprehensive nature of dark fleet evasion tactics through its systematic engagement in unauthorized ship-to-ship transfers with Iranian vessels, coupled with frequent identity obscuration through multiple name and flag changes. The vessel's complete departure from regulatory compliance and operation without verified insurance coverage illustrates the defining characteristics of dark fleet operations.

The case of the OLIVE (IMO: 9318034), operating under the Gabonese flag, further reinforces this pattern of deliberate regulatory evasion. Despite the vessel's age exceeding 20 years, it continues to operate without recognized Protection and Indemnity (P&I) insurance, displaying consistent patterns of AIS manipulation while maintaining routes commonly associated with sanctions evasion. Such cases demonstrate how dark fleet operators combine multiple evasion strategies to operate entirely outside established maritime governance frameworks.

3.2. Gray Fleet: Operational Modalities

The Gray Fleet represents a more nuanced phenomenon in the landscape of shadow maritime operations, characterized by its operation in a zone of legal ambiguity. Unlike the Dark Fleet, Gray Fleet vessels typically maintain active Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmitters, although data manipulation is not uncommon [

12]. This practice of maintaining active AIS while potentially altering the transmitted data allows these vessels to project an appearance of compliance with international maritime regulations while still obscuring aspects of their operations.

A defining feature of the Gray Fleet is its exploitation of regulatory loopholes and jurisdictional complexities, an approach that bears striking similarities to the concept of gray zone warfare in international relations. Gray zone warfare refers to actions that fall between the traditional binary of war and peace, often involving covert or deniable operations that exploit ambiguities in international law and norms [

13]. In a similar vein, Gray Fleet vessels operate in a gray area of international maritime law, leveraging the intricacies and inconsistencies in global maritime regulations to their advantage. This strategic approach allows them to navigate the complex web of international sanctions and trade restrictions while maintaining a veneer of legitimacy. Much like state actors engaging in gray zone tactics, the Gray Fleet employs various methods to project an image of compliance, carefully managing their visible operations to appear adherent to international norms while obscuring their true operational nature. This parallel underscore the sophisticated nature of Gray Fleet operations and highlights the challenges they pose to traditional regulatory and enforcement mechanisms in the maritime domain.

The emergence of the Gray Fleet as a significant actor in global maritime trade is particularly evident in its role in the transportation of Russian oil. Comprising over 900 vessels, this fleet has become instrumental in facilitating oil exports to non-sanctioning countries, including China, Turkey, and India [

14]. The composition of the Gray Fleet reflects its specialized role in this trade, with a significant proportion dedicated to oil transportation: 33% are crude oil tankers, 23% are oil product tankers, and 20% are oil/chemical tankers. This specialized fleet structure underscores the Gray Fleet's strategic importance in circumventing international sanctions on Russian oil exports.

The operational patterns of gray fleet vessels are notably demonstrated by the ADVANTAGE ANGEL (IMO: 9779953), registered under the Marshall Islands flag. This vessel exemplifies the nuanced approach characteristic of gray fleet operations, maintaining formal registration and selective AIS compliance while engaging in sanctioned trade routes. Documentation reveals the transport of 500,000 barrels of crude oil along contentious routes, yet the vessel maintains its formal flag registration and corporate structure, illustrating the gray fleet's strategy of operating within technical compliance while pursuing questionable activities.

Similarly, the STI DUCHESSA (IMO: 9669938), also registered in the Marshall Islands, demonstrates the sophisticated methods employed by gray fleet operators to maintain a facade of legitimacy while facilitating sanctions evasion. The vessel's operations involve the transportation of Russian-origin refined products through complex indirect routes, utilizing transshipment points in India before reaching final destinations. While maintaining active insurance and registration, the vessel's operations reveal the intricate mechanisms through which gray fleet operators exploit regulatory ambiguities.

3.3. Dark Fleet: Comparative Analysis of Dark and Gray Fleets

Despite their nuanced differences, the Dark and Gray Fleets exhibit significant commonalities, especially in their cargo focus, which primarily includes various types of wet cargo. The Dark Fleet shows a predilection for oil/chemical tankers (35%) and crude oil tankers (32%), whereas the Gray Fleet prominently features crude oil tankers (33%), oil products tankers (23%), and oil/chemical tankers (20%) [

15]. This collective emphasis on transporting wet cargo highlights their pivotal role in the global shipping industry, representing 18% of vessels tasked with such cargo.

Ownership structures within both fleets unveil patterns that amplify concerns regarding the evasion of regulations and sanctions. The frequent utilization of flags of convenience from countries like Panama, Liberia, Marshall Islands, Malta, and Russia is common to both fleets, facilitating their ability to navigate through regulatory loopholes and operate under reduced scrutiny. This strategic choice underscores the challenges in enforcing international maritime regulations and sanctions effectively [

16].

Moreover, the age profile of vessels across both fleets introduces serious concerns about safety and environmental risks. Over 50% of vessels in both the Dark and Gray Fleets are 15 years or older, significantly exceeding the average lifespan of oil tankers. This trend towards an aging fleet, compounded by dubious maintenance standards, heightens the risk of accidents, spills, and consequent environmental hazards [

17].

In essence, while the Dark and Gray Fleets may diverge in their operational tactics, they converge in their broader impact on the maritime industry, highlighting issues related to safety, environmental sustainability, and the global effort to enforce sanctions. As shown in

Table 1, while these fleets differ in their AIS usage and operational tactics, they share similar characteristics in vessel age and flag choice.

Case Study: Chinese Fishing Dark Fleets The emergence of Chinese distant-water fishing (DWF) fleets during the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates a distinct variant of dark fleet operations. In 2020, a fleet of approximately 340 Chinese vessels operated near the Galapagos Marine Reserve [

18], with over 100 vessels regularly disabling their AIS systems. Unlike Russian oil tankers operating in gray zones of sanctions compliance, these vessels directly violated international fishing regulations while maintaining a facade of legitimacy through partial compliance with tracking requirements [

19], [

20], [

21], [

22], [

23].

Comparative Analysis: EU "Light Fleets" in Fishing In contrast to Chinese dark fleets, European Union fishing vessels present an interesting counterpoint. While maintaining active AIS systems and formal compliance with regulations, some EU vessels engage in similarly unsustainable fishing practices. For instance, in 2023, the EU super-trawler Helen Mary (IMO: 9126364) maintained active transponders while operating off West Africa, demonstrating how destructive fishing practices can occur within technical compliance of regulations. Also, the trawler Willem Van Der Zwan (IMO: 9187306) had transponders active during his campaign in West Africa. This comparison highlights how the binary between dark and light operations does not always align with the actual impact of maritime activities [

24], [

25], [

26].

As shown in

Table 2, the operational patterns and characteristics of shadow fleets vary significantly across maritime sectors, from oil transportation to fishing activities, demonstrating how these evasive tactics have been adapted for different commercial purposes.

4. Approaches to Detecting Dark and Gray Fleet Characteristics

The covert nature of dark and gray fleets poses significant challenges to traditional methods of monitoring and regulation. Without the right tools, identifying vessels engaged in sanctioned cargo transportation becomes a daunting task, as these fleets invest substantial effort in concealing their actions. However, advancements in technology provide a promising avenue for enhancing detection capabilities and safeguarding the integrity of global maritime operations. The identification and monitoring of such vessels require a nuanced understanding of their operating characteristics and behaviors.

Despite its more sophisticated operational model, the Gray Fleet faces challenges like those of the Dark Fleet, particularly concerning vessel age and maintenance. A substantial portion of Gray Fleet vessels exceed 15 years of age, mirroring the trend observed in the Dark Fleet. This aging infrastructure raises significant concerns about operational safety and environmental risk mitigation. The use of older vessels not only increases the likelihood of mechanical failures and accidents but also poses potential environmental hazards due to the increased risk of oil spills and other maritime incidents.

Disabled AIS Transmitter

One of the most telling signs of a vessel's attempt to operate under the radar is the manipulation or complete disabling of its Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmitter. The AIS is a crucial tool in maritime safety, designed to provide real-time tracking and identification information about ships to other vessels and to coastal authorities. It transmits data including the ship's identity, position, speed, and course [

27].

Dark and gray fleet vessels often disable their AIS transmitters to vanish from radar and avoid detection by authorities. This tactic is particularly common in areas where illicit activities, such as smuggling, illegal fishing, or unauthorized transshipment of sanctioned goods, are conducted. By going "dark," these vessels can operate without revealing their location, making it challenging for enforcement agencies to track their movements and ascertain their activities [

28], [

29]. The deliberate disabling of AIS transmitters not only poses significant risks to maritime safety, as it increases the likelihood of collisions at sea, but it also complicates the task of monitoring international waters for illegal activities. This behavior necessitates the development and deployment of alternative tracking technologies and methodologies that can detect and monitor vessels even when they attempt to hide their presence [

30], [

31].

The waters off West Africa have emerged as a hotspot for AIS spoofing and other deceptive practices, highlighting the global nature of these evasion tactics. Investigations have revealed sophisticated operations involving multiple vessels and coordinated AIS manipulation. For instance, tankers have been observed using falsified coordinates while conducting ship-to-ship transfers in the Mediterranean, demonstrating the lengths to which operators will go to conceal their activities [

32]. One particularly concerning development has been the manipulation of AIS data. In some cases, 'ghost ships' have been created, with AIS signals showing nonexistent vessels or falsified positions, complicating efforts to track the movement of sanctioned oil [

33], [

34].

The economic impact of these deceptive practices is substantial. Estimates suggest that 8 billions of dollars’ worth of oil exports have been facilitated through AIS spoofing and other evasion tactics, undermining the effectiveness of sanctions regimes [

35].

Case Study: The Crude Carrier Network Recent investigations have revealed sophisticated networks of crude carriers operating in the shadow fleet. The PABLO, (ex-Mockinbird, ex-Helios, ex-Adisa, ex-Siro 1, ex-Hudara, ex-S Spirit, ex-Olympic Spirit II). IMO: 9133587), a 2003-built crude oil tanker flagged in Gabon, exemplifies the complexity of these operations [

36]. After changing ownership in late 2022, the vessel:

Switched off its AIS for extended periods in the Mediterranean

Conducted multiple ship-to-ship transfers in the Black Sea

Changed its flag twice within six months

Operated without proper insurance documentation

Systematic satellite surveillance between May and November 2024 has documented patterns of potentially illicit maritime operations in specific geographic regions. In waters approximately 70 kilometers offshore Eastern Johor, up to eight simultaneous ship-to-ship transfers have been observed in a single day, often involving aging vessels that compound environmental and safety risks. These operations frequently coincide with oil slick detections, demonstrating how operational patterns exploit gaps in maritime surveillance while increasing risks to marine ecosystems.

The scale and regularity of these activities suggest an industrialized approach to sanctions evasion, with established operational patterns that exploit gaps in maritime surveillance and enforcement capabilities. The combination of AIS manipulation, aging vessels, and unsafe transfer practices observed in these waters exemplifies the complex challenges facing regulatory authorities and underscores the need for enhanced monitoring and enforcement mechanisms.

Inconsistent Information

Inconsistent information regarding a ship's name, flag, or registration details is a significant red flag. Covert fleets frequently manipulate or change their identification information to sow confusion and evade tracking. Discrepancies between the information from official sources and the vessel's reported details, or frequent changes in identification information, can indicate the vessel's potential involvement in illicit activities [

37].

This practice of altering or providing inconsistent information is a deliberate attempt to obfuscate the vessel's true identity and ownership, making it difficult for authorities and other interested parties to track its history or investigate its activities. Such maneuvers may involve changing the vessel's name, flag (the country of registration), or even manipulating its physical appearance through repainting and modifications [

38], [

39].

Unusual Behavior

Dark fleet vessels may display behavior patterns that deviate from the norm, including operating in restricted areas, shunning designated ports or coastlines, or conducting suspicious meetings with other vessels at sea. Ship-to-ship (STS) transfers have become a key tactic in the dark fleet's operations. While STS transfers are a legitimate practice in the oil trade, their frequency and locations have changed significantly in response to sanctions, often occurring in international waters to avoid regulatory scrutiny [

40], [

41], [

42], [

43], [

44]. Such atypical actions are key indicators of involvement in covert operations. Regulatory bodies have increasingly focused on these risky STS operations, recognizing them as a critical weak point in sanctions enforcement. The proliferation of these transfers in areas like the Mediterranean and Southeast Asian waters has raised concerns about both safety and legal compliance [

45].

These vessels often avoid well-monitored routes and ports to evade scrutiny, opting instead for remote areas where oversight is minimal. Meetings between vessels at sea, especially in international waters, can facilitate the transfer of illegal cargo, including drugs, weapons, and sanctioned goods, without detection. Such rendezvous are challenging to monitor and regulate, requiring surveillance from air and space, as well as coordination between different countries' naval and coastguard services.

Ownership Registration

Dark fleet vessels often have obscure ownership structures, complicating accountability. These vessels are commonly registered to owners in countries known for less stringent regulatory oversight, complicating the tracking and regulation of their activities, and contributing to the difficulties in ensuring compliance with international norms [

46].

The practice of registering vessels through complex networks of shell companies and offshore entities is designed to obscure the true ownership and, consequently, the responsibility for the vessel's activities. This lack of transparency hinders efforts to enforce maritime laws and regulations, as it becomes challenging to identify and hold the actual owners accountable for violations [

47], [

48].

Age of Vessels

Dark and gray fleet vessels, especially oil tankers, are frequently older, with a significant portion being over 15 years of age. The utilization of aging vessels, which may not meet the most current safety and environmental standards, heightens the risk of accidents, spills, and environmental harm.

Older vessels are often preferred by operators of dark and gray fleets due to their lower acquisition and maintenance costs. However, these vessels may lack the latest safety features and technologies, making them more prone to mechanical failures and accidents. Additionally, their inferior environmental performance can lead to significant ecological damage, particularly in the event of an oil spill or other hazardous incident.

Flag Choice

The use of flags of convenience has long been a contentious issue in maritime trade, but it has taken on new significance in the context of sanctions evasion. Dark and gray fleets often register their vessels under flags of convenience, such as Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands, among others. This choice is strategically made to benefit from the legal advantages and lax regulatory practices associated with these flags, facilitating evasion of sanctions and reduced oversight in their operations [

49]. Also, countries with less stringent regulatory oversight, such as Cameroon and Gabon, have been implicated in registering vessels linked to sanctioned oil trades, complicating enforcement efforts [

50]

Flags of convenience offer a regulatory environment that allows vessel operators to circumvent stricter labor, safety, and environmental standards that might be enforced under more stringent registries. This practice not only undermines international efforts to promote maritime safety and environmental protection but also complicates the enforcement of sanctions and other regulatory measures.

5. Discussion

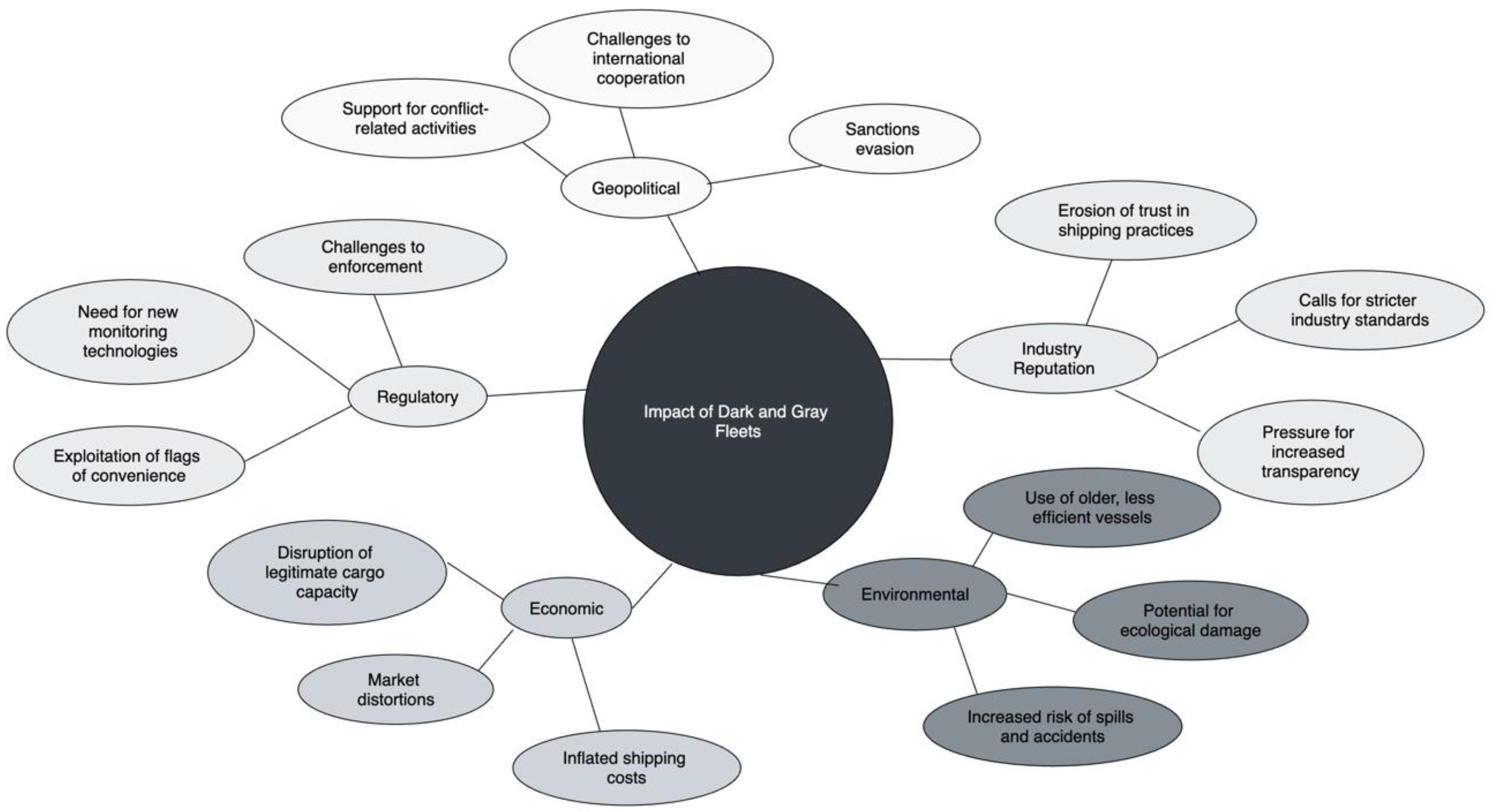

The emergence of dark and gray fleets has significantly disrupted the global maritime industry, particularly in response to international sanctions on Russian oil exports. These fleets operate covertly, often evading traditional monitoring and regulatory mechanisms, which has led to cascading effects across economic, geopolitical, environmental, and regulatory spheres

[Figure 1]. The scale of this phenomenon is substantial, with the dark fleet expanding rapidly to reach approximately 1,100 vessels by 2024 [

15]. By September 2023, it accounted for an estimated 10% of global seaborne oil transportation, with over 600 tankers from a global fleet of about 6,000 engaged in covert operations [

51].

The evolution of shadow fleet tactics is particularly evident in specific regional contexts. North Korea's sophisticated sanctions evasion through maritime channels has created a template now being adapted by other actors. Their techniques, particularly in ship-to-ship transfers and documentation fraud, have been refined and scaled up by larger operations. Similarly, the emergence of Chinese fishing dark fleets represents a distinct challenge, demonstrating how shadow fleet tactics are being adapted beyond sanctions evasion to resource exploitation [

11], [

52].

The economic impact of dark and gray fleets is multifaceted, characterized by significant market disruption. The increased demand for older vessels has led to unexpected price surges for aging tonnage, creating a parallel market operating outside normal commercial frameworks [

53], [

54]. This has resulted in a disruption of traditional market dynamics and fleet renewal patterns [

55]. Furthermore, the reduced vessel availability has increased shipping costs, with these higher costs being transferred to legitimate cargo owners. The G7's price cap mechanism on Russian oil, introduced in December 2022, has faced challenges in enforcement, with reports suggesting significant breaches of the cap [

45], [

56]. The tanker sale and purchase market has seen a significant shift, with older vessels that might have been destined for scrap yards now fetching premium prices. This trend has altered fleet renewal patterns and complicated long-term planning for legitimate operators [

57]. With tanker demolition rates at historic lows, ships that would typically be scrapped are instead being pressed into service in these shadowy operations [

53]. These developments have collectively reshaped the maritime industry's economic landscape, creating a complex web of challenges for stakeholders across the sector.

Geopolitically, these fleets have enabled Russia to continue and even expand oil sales despite sanctions, facilitating a shift in export destinations from Europe to Asian markets, particularly India and China [

58]. The opacity in ownership structures complicates the understanding of these operations, raising concerns about funds potentially supporting undesired activities, such as the Russian war effort. Moreover, there are significant challenges in balancing regulatory enforcement with complex international relations [

59].

Environmental and safety concerns are paramount in the context of dark and gray fleets. Over 50% of dark fleet vessels exceed 15 years of age, increasing the risk of mechanical failures, accidents, and oil spills. There are serious concerns about inadequate maintenance standards and outdated safety equipment, heightening the potential for major environmental disasters, especially in sensitive areas [

60]. Additionally, the growing number of uninsured or underinsured vessels poses an increased risk to coastal communities and ecosystems [

61]

The regulatory challenges posed by dark and gray fleets are substantial. These fleets exploit flags of convenience, leveraging lax regulatory practices in countries like Panama, Liberia, Marshall Islands, Malta and Cameroon. This exploitation creates difficulties in enforcing sanctions and safety standards [

62]. There is a pressing need for advanced technological solutions for vessel tracking and identification, as well as for addressing the challenges in analyzing complex ownership structures and vessel histories. International collaboration is crucial, necessitating coordinated efforts to close regulatory loopholes and develop unified guidelines for transparency, accountability and safety.

Addressing the challenges posed by dark and gray fleets requires a multifaceted approach. This includes the development of comprehensive and adaptive maritime governance frameworks, the integration of advanced technologies including Ai [

63], [

64], [

65], for monitoring and detection and enhanced international collaboration and information sharing. Stricter enforcement of environmental and safety standards is essential, as are public awareness campaigns to garner support for regulatory initiatives. The maritime industry must evolve to meet these challenges, striking a delicate balance between economic interests, environmental responsibility, and global security concerns.

6. Conclusions

The fight against clandestine maritime operations, including dark and gray fleets, necessitates robust international collaboration. Given the transnational nature of these illicit activities, no single nation can effectively address the challenge alone. Strengthening international cooperation is paramount to closing regulatory gaps and enhancing enforcement capabilities. Concrete mechanisms to improve this cooperation include the establishment of a global maritime surveillance system that leverages satellite technology and AIS data to detect suspicious vessel activities. Harmonizing maritime laws and standards across jurisdictions will further ensure consistent enforcement and reduce the avenues for regulatory evasion. By prioritizing these collaborative efforts, the international community can more effectively safeguard the integrity of global maritime commerce and protect the marine environment from the risks posed by these covert operations.

The economic disruptions, geopolitical intricacies, environmental risks, and regulatory challenges emanating from covert maritime operations demand a holistic and multi-pronged approach. The journey towards robust maritime governance involves not only fortifying regulatory measures but also harnessing the potential of advanced technologies, fostering international collaboration, nurturing public-private partnerships, and prioritizing environmental sustainability. The diversity of shadow fleet operations - from North Korean sanctions evasion to Chinese fishing fleets and Russian oil transportation - underscores the need for a nuanced and adaptive regulatory response. While these operations share common characteristics, their varying objectives and methods require targeted enforcement strategies.

The convergence of artificial intelligence, satellite imagery, and collaborative frameworks emerges as a beacon of hope in the quest to illuminate the shadows of maritime covert activities. By leveraging the collective intelligence and capabilities of nations, private entities, and technological innovators, we can construct a resilient and adaptive governance framework capable of withstanding the clandestine maneuvers of dark and gray fleets [

66].

In this pursuit, it is essential to recognize the interconnectedness of global maritime activities and the need for a united front against illicit operations. The collaborative efforts of nations, supported by the ingenuity of private enterprises, hold the key to dismantling the shadows that threaten the transparency and security of our oceans.

As we chart the course forward, the lessons learned from the covert world of maritime operations serve as guideposts for a future defined by resilience, accountability, and sustainability. The endeavor to illuminate the shadows is not only a matter of safeguarding economic interests but also a collective responsibility to protect our oceans, preserve our environment, and fortify the foundations of a secure and interconnected global maritime ecosystem.

In the journey towards secure seas and transparent waters, the commitment to innovation, collaboration, and ethical stewardship will serve as the compass guiding us through the maritime shadows into a future where the seas are not just navigated but protected, ensuring the prosperity of generations to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.-D.; methodology, E.R.-D. and J.I.A.; software, N.E.; validation, E.R.-D., J.I.A. and N.E.; formal analysis, E.R.-D.; investigation, E.R.-D.; resources, J.I.A.; data curation, N. E.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R.-D.; writing—review and editing, J.I.A.; visualization, N.E.; supervision, J.I.A.; project administration, E.R.-D.; funding acquisition, J.I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is obtained from the sources which are open sources. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author directly or the reader can consult the sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IMO, “Resolution A.1192(33) - ‘Urging Member States and All Relevant Stakeholders to Promote Actions to Prevent Illegal Operations in the Maritime Sector by the “Dark Fleet” or the “Shadow Fleet,”’” 2023. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/AssemblyDocuments/A.1192(33).pdf.

- F. Shamgholi, “Sanctions against Iran and their effects on the global shipping industry,” Lund University, 2012. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=2520391&fileOId=3046709.

- M. Fries, “The repeal of economic sanctions against Iran: Global economic implications and opportunities for the chemical tanker sector,” Erasmus University Rotterdam, 2014. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://thesis.eur.nl › pub › Fries-M.-The-repeal-of..

- J. Horowitz, “A mysterious fleet is helping Russia ship oil around the world. And it’s growing,” CNN. Accessed: Sep. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/03/01/business/russia-oil-shadow-fleet/index.html.

- J. Yerushalmy and H. Krishnamoorthy, “How a burnt out, abandoned ship reveals the secrets of a shadow tanker network,” The Guardian. Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/sep/18/how-a-burnt-out-abandoned-ship-reveals-the-secrets-of-a-shadow-tanker-network.

- E. Braw, “Russia’s growing dark fleet: Risks for the global maritime order,” Atlantic Council. Accessed: Sep. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/russias-growing-dark-fleet-risks-for-the-global-maritime-order/.

- E. Braw, “Ships Are Flying False Flags to Dodge Sanction,” Foreign Policy. Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/01/30/ships-false-flags-convenience-sanctions/.

- J. Stockbruegger, “Reducing Russia’s Oil Revenues,” The RUSI Journal, vol. 168, no. 5, pp. 34–42, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Raanan, “The great flag exodus: Where did Iran-linked ships deflagged by Panama go,” 2023. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1144047/The-great-flag-exodus-Where-did-Iran-linked-ships-deflagged-by-Panama-go.

- United Nations. Security Council, “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009). S/2019/171,” 2019. Accessed: Nov. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n19/028/82/pdf/n1902882.pdf.

- Office of Public Affairs, “Department of Justice Announces Forfeiture of North Korean Cargo Vessel,” United States Department of Justice. Accessed: Nov. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-announces-forfeiture-north-korean-cargo-vessel.

- S. Parker, “Russia’s shadow tanker fleet runs into trouble,” 2024. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/russia-s-shadow-tanker-fleet-runs-trouble.

- J. L. Votel, C. T. Cleveland, C. T. Connett, and W. Irwin, “Unconventional warfare in the gray zone,” Joint Forces Quarterly, vol. 80, no. 1, pp. 101–109, 2016.

- T. Yusuf, “U.S. Sanctions Are Ineffective: Russia’s Dark Fleet and Gray Fleet and its Circumvention of Sanctions,” University Library of Munich, Germany, Aug. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:pra:mprapa:121829.

- Windward, “Windward Q4 Trade Patterns & Risk Insights Report,” 2024.

- T. Pastucha, “Russia’s ‘Shadow Fleet’ on Course to Circumvent Western Sanctions,” The Polish Institute of International Affairs. Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://pism.pl/publications/russias-shadow-fleet-on-course-to-circumvent-western-sanctions.

- B. Hilgenstock, O. Hrybanovskii, and A. Kravtsev, “Assessing Russia’s Shadow Fleet: Initial Build-Up, Links to the Global Shadow Fleet, and Future Prospects,” 2024. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://kse.ua/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Global-Shadow-Fleet-June-2024.pdf.

- S. Arcos, “Ecuador navy surveils huge Chinese fishing fleet near Galapagos,” Reuters, 2020. Accessed: Nov. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/article/world/ecuador-navy-surveils-huge-chinese-fishing-fleet-near-galapagos-idUSKCN2550RR/.

- J. Li et al., “Satellite observation of a newly developed light-fishing ‘hotspot’ in the open South China Sea,” Remote Sens Environ, vol. 256, p. 112312, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guan et al., “Study on the Activity Laws of Fishing Vessels in China’s Sea Areas in Winter and Spring and the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic Based on AIS Data,” Front Mar Sci, vol. 9, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Li et al., “Trend in fishing activity in the open South China Sea estimated from remote sensing of the lights used at night by fishing vessels,” ICES Journal of Marine Science, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 230–241, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Pedrozo, “China’s IUU Fishing Fleet: Pariah of the World’s Oceans,” International Law Studies, vol. 99, no. 1, p. 10, 2022.

- X. Shi, “International advocacy and China’s distant water fisheries policies,” Mar Policy, vol. 152, p. 105635, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Mazaris et al., “Threats to marine biodiversity in European protected areas,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 677, pp. 418–426, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Aminian-Biquet et al., “Over 80% of the European Union’s marine protected area only marginally regulates human activities,” One Earth, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 1614–1629, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Seas at Risk, “A quantification of bottom towed fishing activity in marine Natura 2000 sites,” 2024. Accessed: Nov. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://seas-at-risk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/report_bottom_towed_fishing_actvity_in_marine_natura_2000_sites.pdf.

- IMO, “A 33/13/2 - Consideration of the reports and recommendations of the marine environment protection committee,” 2023.

- N. Longépé et al., “Completing fishing monitoring with spaceborne Vessel Detection System (VDS) and Automatic Identification System (AIS) to assess illegal fishing in Indonesia,” Mar Pollut Bull, vol. 131, pp. 33–39, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Kurekin et al., “Operational Monitoring of Illegal Fishing in Ghana through Exploitation of Satellite Earth Observation and AIS Data,” Remote Sens (Basel), vol. 11, no. 3, p. 293, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Oozeki et al., “Reliable estimation of IUU fishing catch amounts in the northwestern Pacific adjacent to the Japanese EEZ: Potential for usage of satellite remote sensing images,” Mar Policy, vol. 88, pp. 64–74, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Chuaysi and S. Kiattisin, “Fishing Vessels Behavior Identification for Combating IUU Fishing: Enable Traceability at Sea,” Wirel Pers Commun, vol. 115, no. 4, pp. 2971–2993, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alaric Nightingale, “Tanker Tricks on the High Seas Expose Shadowy Russian Oil Trade,” Bloomberg, 2023. Accessed: Nov. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/international-trade/tanker-tricks-on-the-high-seas-expose-shadowy-russian-oil-trade.

- A. Androjna, I. Pavić, L. Gucma, P. Vidmar, and M. Perkovič, “AIS Data Manipulation in the Illicit Global Oil Trade,” J Mar Sci Eng, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 6, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. D. do Nascimento, T. A. O. Alves, C. M. de Farias, and D. L. C. Dutra, “A Hybrid Framework for Maritime Surveillance: Detecting Illegal Activities through Vessel Behaviors and Expert Rules Fusion,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 17, p. 5623, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Poetzsch, “Uncovering 8 billion dollars worth of spoofed oil exports using Spire Maritime’s AIS Position Validation,” 2023. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://spire.com/blog/maritime/uncovering-8-billion-dollars-worth-of-spoofed-oil-exports-using-ais-position-validation/.

- Robin Des Bois, “Shipbreaking. Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition,” 2023.

- H. Meyers, The nationality of ships. Springer, 2012.

- R. Rogers, “Ship registration: a critical analysis,” World Maritime University, 2010. Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://commons.wmu.se/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1446&context=all_dissertations.

- D. D. Miller and U. R. Sumaila, “Flag use behavior and IUU activity within the international fishing fleet: Refining definitions and identifying areas of concern,” Mar Policy, vol. 44, pp. 204–211, 2014.

- D. I. Stavrou and N. P. Ventikos, “Ship to ship transfer of cargo operations: risk assessment applying a fuzzy inference system,” Journal of Risk Analysis and Crisis Response, vol. 4, no. 4, 2014.

- L. J. Clarke, G. J. Macfarlane, I. Penesis, J. T. Duffy, S. Matsubara, and R. J. Ballantyne, “A Risk Assessment of a Novel Bulk Cargo Ship-to-Ship Transfer Operation Using the Functional Resonance Analysis Method,” in Volume 3B: Structures, Safety and Reliability, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Sultana, P. Okoh, S. Haugen, and J. E. Vinnem, “Hazard analysis: Application of STPA to ship-to-ship transfer of LNG,” J Loss Prev Process Ind, vol. 60, pp. 241–252, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. Suyatna et al., “Determination of water quality condition from water samples around location of ship to ship transfer of coal in Balikpapan, East Kalimantan, Indonesia,” IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci, vol. 348, no. 1, p. 012067, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. P. V. Dimitrios I. Stavrou, “Ship to Ship Transfer of Cargo Operations: Risk Assessment Applying a Fuzzy Inference System,” Journal of Risk Analysis and Crisis Response, vol. 4, no. 4, Oct. 2021, [Online]. Available: https://jracr.com/index.php/jracr/article/view/129.

- M. W. Bockmann, “Dark fleet tanker Mando One seen at anchor off Italy,” 2023. Accessed: Nov. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1150624/Dark-fleet-tanker-Mando-One-seen-at-anchor-off-Italy.

- J. B. Fox Jr, “Vessel ownership and terrorism: requiring disclosure of beneficial ownership is not the answer,” Loy. Mar. LJ, vol. 4, p. 92, 2005.

- A. Kandakoglu, M. Celik, and I. Akgun, “A multi-methodological approach for shipping registry selection in maritime transportation industry,” Math Comput Model, vol. 49, no. 3–4, pp. 586–597, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Celik, I. D. Er, and A. F. Ozok, “Application of fuzzy extended AHP methodology on shipping registry selection: The case of Turkish maritime industry,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 190–198, 2009.

- F. J. M. Llácer, “Open registers: past, present and future,” Mar Policy, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 513–523, Nov. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Bockmann, “Cameroon flag registry in fresh links to Iran oil trading,” 2021. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1138869/Cameroon-flag-registry-in-fresh-links-to-Iran-oil-trading.

- M. W. Bockmann, “Dark fleet of tankers now comprises 10% of seaborne oil transport,” 2023. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1144275/Dark-fleet-of-tankers-now-comprises-10-of-seaborne-oil-transport.

- J. Park et al., “Illuminating dark fishing fleets in North Korea,” Sci Adv, vol. 6, no. 30, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Wingrove, “Scrapping levels slow as demand rises for older tonnage,” Riviera. Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.rivieramm.com/news-content-hub/news-content-hub/scrapping-levels-slow-as-demand-rises-for-older-tonnage-81845.

- Allianz, “Navigating troubled waters: risk challenges for shipping in 2024,” Allianz Insurance. Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://commercial.allianz.com/news-and-insights/expert-risk-articles/shipping-red-sea-impact.html.

- UNCTAD, “Review of maritime transport 2024,” 2024. Accessed: Nov. 14, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/rmt2024_en.pdf.

- European Union, “Official Journal of the European Union, L 311I, 3 December 2022,” Dec. 2022.

- UNCTAD, “Review of Maritime Transport 2023,” 2023. Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/rmt2023_en.pdf.

- P. Katinas, “Monthly analysis of Russian fossil fuel exports and sanctions,” Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air. Accessed: Sep. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://energyandcleanair.org/april-2024-monthly-analysis-of-russian-fossil-fuel-exports-and-sanctions/.

- M. W. Bockmann, “UK contributed to ‘shadow fleet’ evolution as sanctions side effect, says Sovcomflot,” 2024, Accessed: Sep. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1150628/UK-contributed-to-shadow-fleet-evolution-as-sanctions-side-effect-says-Sovcomflot.

- M. W. Bockmann, “Dark fleet danger as accident-prone elderly tankers anchor off Malaysia :: Lloyd’s List,” 2022. Accessed: Jun. 13, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1142833/Dark-fleet-danger-as-accident-prone-elderly-tankers-anchor-off-Malaysia.

- I. Parlov and U. Sverdrup, “The Emerging ‘Shadow Fleet’ as a Maritime Security and Ocean Governance Challenge,” in Maritime Security Law in Hybrid Warfare, Brill | Nijhoff, 2024, pp. 225–262. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Alcaide, E. Rodríguez-Díaz, and F. Piniella, “European policies on ship recycling: A stakeholder survey,” Mar Policy, vol. 81, pp. 262–272, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Octavian and W. Jatmiko, “Designing Intelligent Coastal Surveillance based on Big Maritime Data,” in 2020 International Workshop on Big Data and Information Security (IWBIS), IEEE, Oct. 2020, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- A. Haijoub, A. Hatim, M. Arioua, S. Hammia, A. Eloualkadi, and A. Guerrero-González, “Fast Yolo V7 Based CNN for Video Streaming Sea Ship Recognition and Sea Surveillance,” in Modern Artificial Intelligence and Data Science: Tools, Techniques and Systems, A. Idrissi, Ed., Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023, pp. 99–109. [CrossRef]

- P. Bernabé, A. Gotlieb, B. Legeard, D. Marijan, F. O. Sem-Jacobsen, and H. Spieker, “Detecting Intentional AIS Shutdown in Open Sea Maritime Surveillance Using Self-Supervised Deep Learning,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, pp. 1–12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Maceiras, G. Cao-Feijóo, J. M. Pérez-Canosa, and J. A. Orosa, “Application of Machine Learning in the Identification and Prediction of Maritime Accident Factors,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 16, p. 7239, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).