Submitted:

15 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Corn Stover

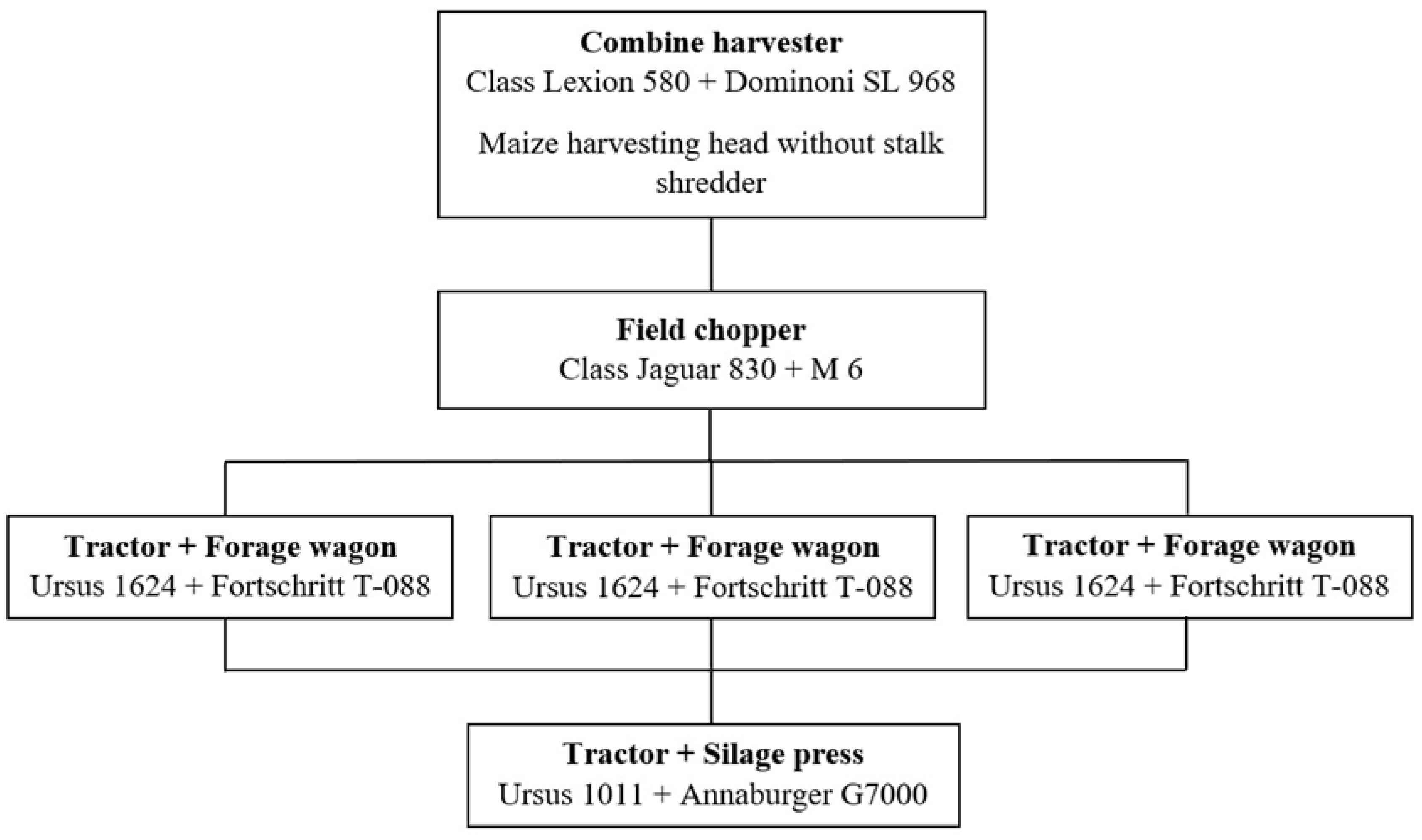

2.2. Harvest and Ensilage Methods

- Variant 1 (CSS1) - with an ensiling enhancer containing Lactobacillus plantarum (DSM 3676 and DSM 3677) and two strains of propionic acid bacteria (DSM 9676 and DSM 9677) at a dose of 2 l/Mg.

- Variant 2 (CSS2) - with an ensiling enhancer in which the active ingredients were sodium benzoate, propionic acid and sodium propionite at a dose of 5 l/Mg.

- Variant 3 (CSS3) - with an ensiling enhancer containing lactic acid bacteria of the Lactobacillus plantarum strain and Lactobacillus Buchneri at a dose of 0.2 l/Mg.

- Variant 4 (CSS4) - control, with no ensiling enhancer.

2.3. Chemical Analysis

- basic chemical analysis (content of dry matter, crude ash, total protein, crude fiber),

- analysis of volatile fatty acid content,

- pH determination.

2.4. Laboratory Investigations Methane Yield

2.5. Identification of Resource Consumption

2.6. Energy Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of Silages

3.2. Biogas and Methane Yield

| Method of ensiling |

TS | Crude fiber |

Protein | Ash | pH | Lactic acid |

Acetic acid |

Butyric acid |

Methane yield |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method of ensiling | - | |||||||||

| TS | 0.79 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

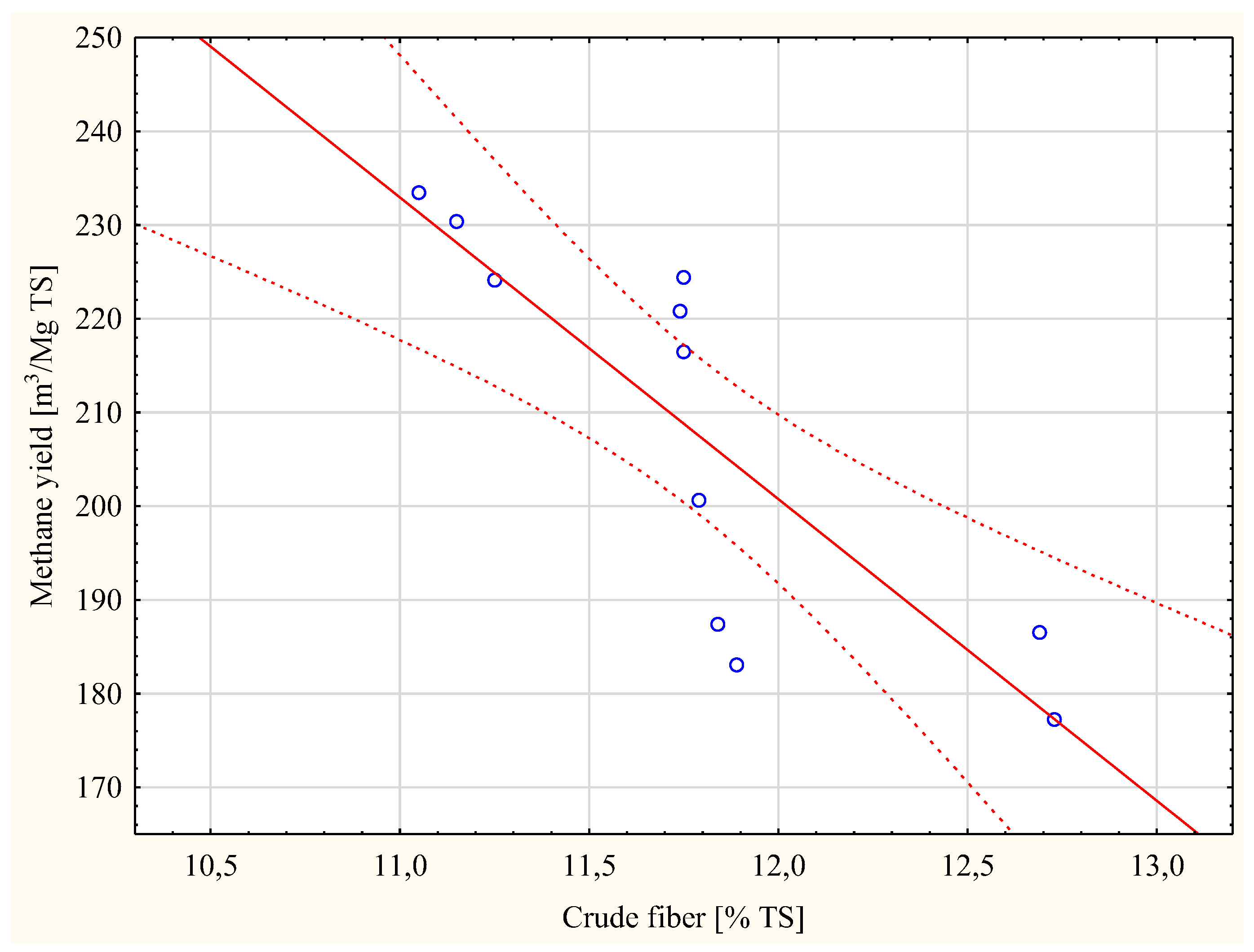

| Crude fiber | 0.65 | 0.08 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Protein | 0.21 | -0.22 | 0.72 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ash | 0.76 | 0.40 | 0.82 | 0.73 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| pH | -0.35 | -0.35 | -0.26 | -0.61 | -0.73 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lactic acid | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.49 | -0.06 | 0.56 | - | - | - | - |

| Acetic acid | -0.46 | -0.34 | -0.44 | -0.71 | -0.84 | 0.98 | 0.48 | - | - | - |

| Butyric acid | 0.26 | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.11 | -0.57 | -0.12 | 0.14 | - | - |

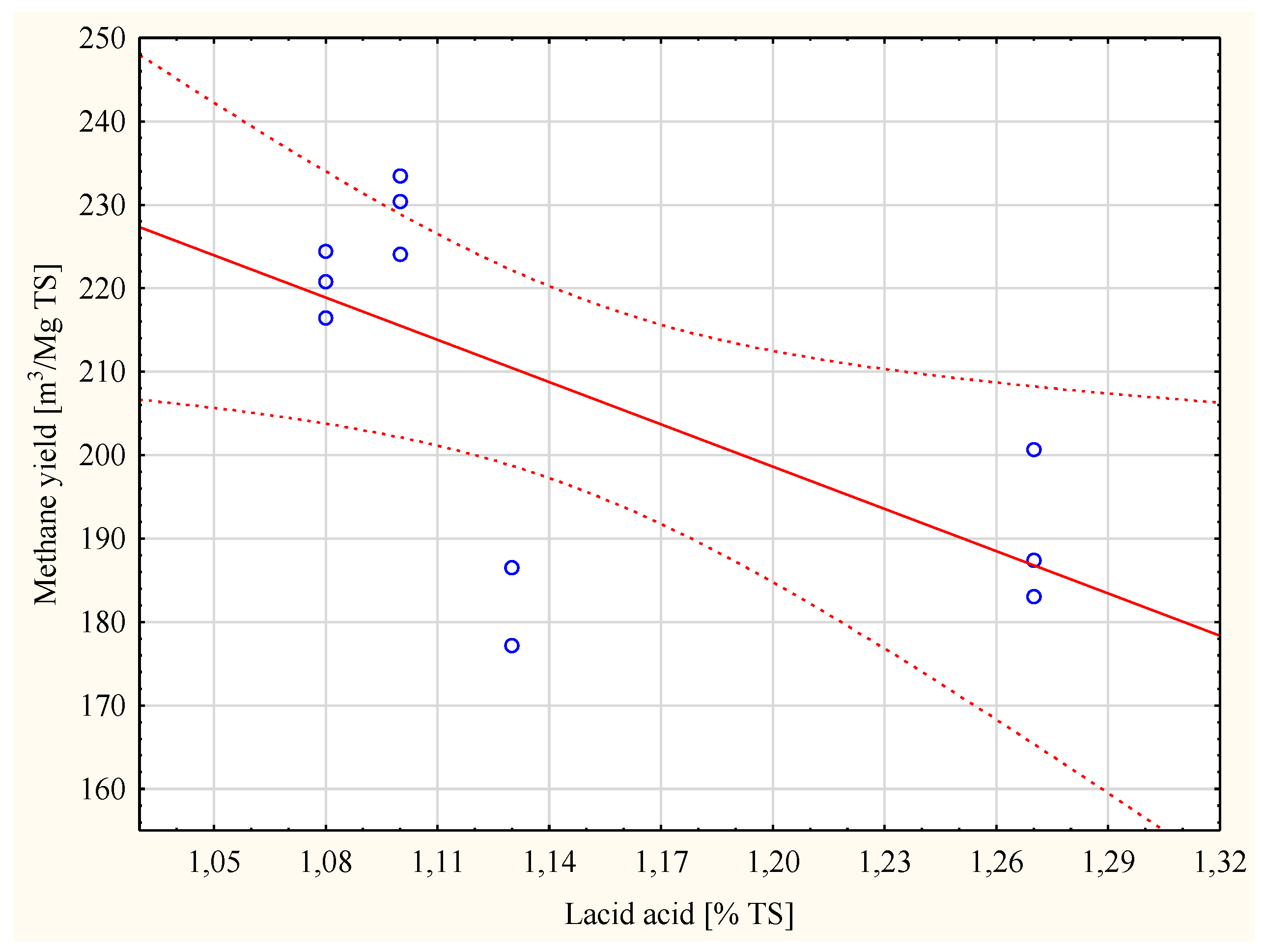

| Methane yield | -0.83 | -0.40 | -0.83 | 0.28 | -0.61 | -0.01 | -0.65 | 0.12 | 0.27 | - |

3.3. Energy and Emission

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Talarek, K.; Knitter-Piątkowska, A.; Garbowski, T. Wind Parks in Poland - New Challenges and Perspectives. Energies 2022, 15, 7004. [CrossRef]

- Talarek, K.; Garbowski, T. RES as the future of district heating. Przegląd Budowlany 2023, 94(3-4), 66–75. [CrossRef]

- Talarek, K.; Knitter-Piątkowska, A.; Garbowski, T. Challenges for district heating in Poland. Discover Energy 2023, 3, 5. [CrossRef]

- Buchspies, B.; Kaltschmitt, M.; Neuling, U. Potential changes in GHG emissions arising from the introduction of biorefineries combining biofuel and electrofuel production within the European Union – A location specific assessment. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 110395. [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources. Dec 21 2018.

- Amon, T.; Amon, B.; Kryvoruchko, V.; Machmüller, A.; Hopfner-Sixt, K.; Bodiroza, V.; et al. Methane production through anaerobic digestion of various energy crops grown in sustainable crop rotations. Bioresour Technol 2007, 98(17) 3204-3212. [CrossRef]

- Czekała, W.; Lewicki, A.; Pochwatka, P.; Czekała, A.; Wojcieszak, D.; Jóźwiakowski, K.; Waliszewska, A. Digestate management in Polish farms as an element of the nutrient cycle. J Clean Prod 2020, 118454. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.F.; Rulli, M.C.; Seveso, A.; D’Odorico, P. Increased food production and reduced water use through optimized crop distribution. Nat Geosci 2017, 10, 919–924. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.H.; Luan, X.B.; Sun, J.X.; Zhao, J.F.; Yin, Y.L.; Wang, Y.B.; Sun, S.K.. Impact assessment of climate change and human activities on GHG emissions and agricultural water use. Agric For Meteorol 2021, 108218. [CrossRef]

- Ravi, R.; de Souza, M.F.; Adriaens, A.; Vingerhoets, R.; Luo, H.; Van Dael, M.; Meers, E. Exploring the environmental consequences of roadside grass as a biogas feedstock in Northwest Europe. J Environ Manage 2023, 344, 118538. [CrossRef]

- Menardo, S.; Airoldi, G.; Cacciatore, V.; Balsari, P. Potential biogas and methane yield of maize stover fractions and evaluation of some possible stover harvest chains. Biosyst Eng 2015, 129, 352–359. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Shen, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.L.; Shao, T.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.X.; Xu, Q.F.; Huo, W.J. The effect of lactic acid bacteria inoculums on in vitro rumen fermentation, methane production, ruminal cellulolytic bacteria populations, and cellulase activities of corn stover silage. J Integr Agric 2020, 19, 838–847. [CrossRef]

- Takada, M.; Niu, R.; Minami, E.; Saka, S. Characterization of three tissue fractions in corn (Zea mays) cob. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 115, 130-135. [CrossRef]

- USDA. World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates. Wiley, 2019.

- Zych, D. The Viability of Corn Cobs As a Bioenergy Feedstock. West Central Research and Outreach Center 2008.

- Sokhansanj, S.; Mani, S.; Tagore, S.; Turhollow, A.F. Techno-economic analysis of using corn stover to supply heat and power to a corn ethanol plant - Part 1: Cost of feedstock supply logistics. Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 75–81. [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszak, D.; Przybył, J.; Myczko, R.; Myczko, A. Technological and energetic evaluation of maize stover silage for methane production on technical scale. Energy 2018, 151, 903–912. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.B.; Wachemo, A.C.; Yuan, H.R.; Li, X.J. Modification of corn stover for improving biodegradability and anaerobic digestion performance by Ceriporiopsis subvermispora. Bioresour Technol 2019, 283, 76–85. [CrossRef]

- Anshar, M.; Ani, F.N.; Kader, A.S.; Makhrani. Electrical energy potential of corn cob as alternative energy source for power plant in Indonesia. Adv Sci Lett 2017, 23, 4184–4187. [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, J.; Marczuk, A.; Pochwatka, P.; Kujawa, S. Maize straw as a valuable energetic material for biogas plant feeding. Materials 2019, 12, 3848. [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, Ł.; Wojcieszak, D.; Olek, W.; Przybył, J. Thermal properties of fractions of corn stover. Constr Build Mater 2019, 210, 709–712. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Siddhu, M.A.H.; He, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.;Liu, G. Enhancing methane production of corn stover through a novel way: Sequent pretreatment of potassium hydroxide and steam explosion. Bioresour Technol 2015, 181, 345-350. [CrossRef]

- Sapci, Z.; Morken, J.; Linjordet, R. An investigation of the enhancement of biogas yields from lignocellulosic material using two pretreatment methods: Microwave irradiation and steam explosion. Bioresources 2013, 8(2), 1976-1985 . [CrossRef]

- Croce, S.; Wei, Q.; D’Imporzano, G.; Dong, R.; Adani, F. Anaerobic digestion of straw and corn stover: The effect of biological process optimization and pre-treatment on total bio-methane yield and energy performance. Biotechnol Adv 2016, 34(8), 1289-1304. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Horiguchi, K.I.; Yoshida, N.; Cai, Y. Methane emissions from sheep fed fermented or non-fermented total mixed ration containing whole-crop rice and rice bran. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2010, 157(1-2), 72-78. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Stokes, M.R.; Wallace, C.R. Wallace Effects of enzyme-inoculant systems on preservation and nutritive value of haycrop and corn silages. J Dairy Sci 1994, 77(2), 501-512. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. Identification and characterization of Enterococcus species isolated from forage crops and their influence on silage fermentation. J Dairy Sci 1999, 82(11), 2466-2471. [CrossRef]

- Buxton, D.R.; Muck, R.E. Silage science and technology. 2003.

- Adamski, M.; Czechlowski, M.; Durczak, K.; Garbowski, T. Determination of the concentration of propionic acid in an aqueous solution by POD-GP model and spectroscopy. Energies 2021, 14(24), 8288. [CrossRef]

- PN-EN ISO 6497:2005 - Animal feeding stuffs. 2005.99.

- Dach, J.; Boniecki, P.; Przybył, J.; Janczak, D.; Lewicki, A.; Czekała, W.; Witaszek,K.; Carmona, P.C.R. Cieślik, M. Energetic efficiency analysis of the agricultural biogas plant in 250kWe experimental installation. Energy 2014, 69(1), 34-38. [CrossRef]

- Wolna-Maruwka, A.; Dach, J. Effect of type and proportion of different structure-creating additions on the inactivation rate of pathogenic bacteria in sewage sludge composting in a cybernetic bioreactor. Archives of Environmental Protection 2009, 35(3), 87-100.

- Ozkan, B.; Kurklu, A.; Akcaoz, H. An input-output energy analysis in greenhouse vegetable production: A case study for Antalya region of Turkey. Biomass Bioenergy 2004, 26(1), 89-95. [CrossRef]

- Houshyar, E.; Zareifard, H.R.; Grundmann, P.; Smith, P. Determining efficiency of energy input for silage corn production: An econometric approach. Energy 2015, 93(2), 2166-2174. [CrossRef]

- Wojcieszak, D.; Przybył, J.; Ratajczak, I.; Goliński, P.; Janczak, D.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Szentner, K.; Woźniak, M. Chemical composition of maize stover fraction versus methane yield and energy value in fermentation process. Energy 2020, 198, 117258. [CrossRef]

- Mani, I.; Kumar, P.; Panwar, J.S.; Kant, K. Variation in energy consumption in production of wheat-maize with varying altitudes in hilly regions of Himachal Pradesh, India. Energy 2007, 32(12), 2336-2339. [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.D.; Omid, M. Energy use patterns and econometric models of major greenhouse vegetable productions in Iran. Energy 2011, 36(1), 220-225. [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh, M.; Omid, M.; Akram, A. A comparative study on energy use and cost analysis of potato production under different farming technologies in Hamadan province of Iran. Energy 2010, 35(7), 2927-2933. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I.; Akcaoz, H.; Ozkan, B. An analysis of energy use and input costs for cotton production in Turkey. Renew Energy 2005, 30(2), 145-155. [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.A.; Kulshreshtha, S.N.; McConkey, B.G.; Desjardins, R.L. An assessment of fossil fuel energy use and CO2 emissions from farm field operations using a regional level crop and land use database for Canada. Energy 2010, 35(5), 2261-2269. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.T.; Hermansen, J.E.; Mogensen, L. Environmental costs of meat production: The case of typical EU pork production. J Clean Prod 2012, 28, 168-176. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Leeke, G.A.; Moretti, C.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Mu, L.; Li, J.; Tao, J.; Yan, B.; Hou, L. Replacing Traditional Plastics with Biodegradable Plastics: Impact on Carbon Emissions. Engineering 2023, 32, 152-162. [CrossRef]

- Wuensch, K.L.; Evans, J.D. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. J Am Stat Assoc 1996, 91(436), 1750-1751. [CrossRef]

- Tharangani, R.M.H.; Yakun, C.; Zhao, L.S.; Ma, L.; Liu, H.L.; Su, S.L.; et al. Corn silage quality index: An index combining milk yield, silage nutritional and fermentation parameters. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2021, 273, 114817. [CrossRef]

- Kung, L.; Shaver, R.D.; Grant, R.J.; Schmidt, R.J. Silage review: Interpretation of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. J Dairy Sci 2018, 101(5), 4020-4033. [CrossRef]

- Kung, L.; Shave, R. Interpretation and use of silage fermentation analysis reports. Focus on Forage 2001, 3, 1–5.

- Kleinschmit, D.H.; Kung, L. A meta-analysis of the effects of Lactobacillus buchneri on the fermentation and aerobic stability of corn and grass and small-grain silages. J Dairy Sci 2006, 89(10), 4005-4013. [CrossRef]

- Oude Elferink, S.J.W.H.; Krooneman, E.J.; Gottschal, J.C.; Spoelstra, S.F.; Faber, F.; Driehuis, F. Anaerobic conversion of lactic acid to acetic acid and 1,2-propanediol by Lactobacillus buchneri. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001, 67(1), 125-132. [CrossRef]

- Sutaryo, S.; Ward, A.J.; Møller, H.B. Thermophilic anaerobic co-digestion of separated solids from acidified dairy cow manure. Bioresour Technol 2012, 114, 195-200. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Sun, S.; Ju, D.; Shan, X.; Lu, X. Review of the state-of-the-art of biogas combustion mechanisms and applications in internal combustion engines. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 69, 50-58. [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, M.; Dach, J.; Lewicki, A.; Smurzyńska, A.; Janczak, D.; Pawlicka-Kaczorowska, J.; Boniecki, P.; Cyplik, P.; Czekała, W.; Jóźwiakowski, K. Methane fermentation of the maize straw silage under meso- and thermophilic conditions. Energy 2016, 115(2), 1495-1502. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Lestander, T.; Geladi, P. Variations in fuel characteristics of corn (Zea mays) stovers: General spatial patterns and relationships to soil properties. Renew Energy 2010, 35(6), 1185-1191. [CrossRef]

- Veluchamy, C.; Gilroyed, B.H.; Kalamdhad, A.S. Process performance and biogas production optimizing of mesophilic plug flow anaerobic digestion of corn silage. Fuel 2019. [CrossRef]

- Veluchamy, C.; Kalamdhad, A.S.; Gilroyed, B.H. Evaluating and modelling of plug flow reactor digesting lignocellulosic corn silage. Fuel 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rotunno, P.; Lanzini, A.; Leone, P. Energy and economic analysis of a water scrubbing based biogas upgrading process for biomethane injection into the gas grid or use as transportation fuel. Renew Energy 2017, 102(b), 417-432. [CrossRef]

- Omar, B.; El-Gammal, M.; Abou-Shanab, R.; Fotidis, I.A.; Angelidaki, I.; Zhang, Y. Biogas upgrading and biochemical production from gas fermentation: Impact of microbial community and gas composition. Bioresour Technol 2019, 286, 121413. [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, F.R.H.; Mel, M.; Jami, M.S.; Ihsan, S.I.; Ismail, A.F. A review of chemical absorption of carbon dioxide for biogas upgrading. Chin J Chem Eng 2016. [CrossRef]

- Gasparatos, A. Resource consumption in Japanese agriculture and its link to food security. Energy Policy 2011, 39(3), 1011-1112. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, J.; Zhang, W. Emergy evaluation of agricultural sustainability of Northwest China before and after the grain-for-green policy. Energy Policy 2014, 67, 508-516. [CrossRef]

| Machine | Number of machines | Machine weight [kg] |

Operating efficiency [ha/h] |

Fuel consumption [l/ha] |

Utilization over time [h] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field chopper | 1 | 10840 | 1.0 | 30 | 3600 |

| Tractor | 3 | 5028 | 0.33 | 12 | 900 |

| Forage wagon | 3 | 3900 | 0.33 | - | 12000 |

| Tractor | 1 | 3700 | 1.00 | 10 | 900 |

| Silage press | 1 | 6500 | 1.00 | - | 3600 |

| Input [unit] | Energy equivalent [MJ/unit] | Reference | Emission factor [kgCO2 e/MJ] | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machinery [kg] | 62.7 | [34,37,38,39] | 0.072 | [34,40] |

| Diesel [l] | 56.3 | [34,37,38,39] | 0.09 | [34,41] |

| Human labor [h] | 1.96 | [34,37,38,39] | 0.36 | [34,41] |

| Liquid chemical [l] | 102 | [34] | 0.25 | [34,41] |

| Flexi silo [kg] | 90 | [37] | 0.25 | [42] |

| Silage | TS [%] | Ash [%TS] | Protein [%TS] | Crude fiber [%TS] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSS1 | 1 | |||

| CSS2 | ||||

| CSS3 | ||||

| CSS4 | ||||

| n | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Silage | pH | Acetic acid [% TS] |

Lactic acid [% TS] |

Butyric acid [% TS] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSS1 | 4.04 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| CSS2 | 4.07 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.1 |

| CSS3 | 3.99 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| CSS4 | 3.95 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| n | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Silage | Biogas yield[m3/Mg TS] | Methane concentration[%] | Methane yield[m3/Mg TS] | HRT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSS1 | 25 | |||

| CSS2 | 25 | |||

| CSS3 | 25 | |||

| CSS4 | 25 | |||

| n | 3 | 3 | 3 | - |

| Silage | Energy equivalent [MJ/Mg TS] | Input energy [MJ/Mg TS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machinery | Diesel | Human labor |

Liquid chemical | Flexi silo | ||

| CSS1 | 80.4 | 715.3 | 1.6 | 34.1 | 212.6 | 1044.0 |

| CSS2 | 80.4 | 715.3 | 1.6 | 85.2 | 212.6 | 1095.1 |

| CSS3 | 80.4 | 715.3 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 212.6 | 1013.3 |

| CSS4 | 80.4 | 715.3 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 212.6 | 1009.9 |

| Silage | Total electricity calculated [kWh/Mg TS] |

Total heat calculated [kWh/Mg TS] |

[GJ/Mg TS] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSS1 | 910.3 | 829.4 | 6.3 |

| CSS2 | 785.7 | 715.8 | 5.4 |

| CSS3 | 946.2 | 862.1 | 6.5 |

| CSS4 | 750.6 | 683.9 | 5.2 |

| Silage | Emission factor [kgCO2/Mg TS] |

[kgCO2/Mg TS] |

[kg CO2/GJ] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machines | Diesel | Human labor |

Liquid chemical |

Flexi silo | |||

| CSS1 | 5.8 | 64.4 | 0.6 | 8.5 | 53.2 | 132.4 | 21.1 |

| CSS2 | 5.8 | 64.4 | 0.6 | 21.3 | 53.2 | 145.2 | 26.9 |

| CSS3 | 5.8 | 64.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 53.2 | 124.7 | 19.2 |

| CSS4 | 5.8 | 64.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 53.2 | 123.9 | 24.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).