1. Introduction

Sustainable management of landslides involves implementing strategies and practices that aim at reducing the risk and impact of landslides while looking for environmentally responsible, economically viable, and socially equitable solutions [

1]. This approach focuses on reaching long-term solutions to strengthen community resilience, including infrastructures and preserving natural ecosystems. Sustainable management seeks to balance hazard mitigation with resource preservation and promote safe land use practices according to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

2].

Ecuador is a country in South America affected by climate change such as El Niño (warm and rainy) or La Niña (cold, dry, and with eastwardly wind) events, and where the Andean cordillera (heights up to 4000 meters above sea level) divide it into three parts: coastal, mountain, and amazon climate and geological classification. That offers an exposition to severe conditions increased by exposition and population vulnerability. Recent natural disasters like flooding, volcanic-related events, and massive landslides (for example, in Chimborazo province) are a source of destruction, including the loss of lives. Thus, adopting sustainable management approaches is crucial, and there is a need to perform extended studies to improve knowledge about the natural hazards that will prevent that impact and permit mitigation of the effects. In that context, the geophysical surveys could provide valuable information and ensure the safety of the population, maintenance of infrastructures, and environmental preservation [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Ecuador’s surficial geomorphology and geology are dominated by eruptive volcanic episodes from 25 M years ago through actual times; hence, that kind of sediments (ashes and tobas) presents the most thickness over ancient rocks and basements. Soil landslides are common hazards, and the surficial geology is the main factor that controls slope stability analysis. Landslides have increased in recent years both in frequency and severity all along the Andean Cordillera [

9,

10] and also in Ecuador, where the climate changes with the increase in rainfall operate like a trigger for those events [

11].

Understanding the factors involved in slope stability is vital to identifying potential prone areas to landslides. Both spatial and temporal dimensions must be analyzed to assess the susceptibility to landslides and deep knowledge of potential causes and factors involved in landslides is required. The vulnerability in Andean countries is also increasing due to the size of the population, land use (deforestation), and urbanization, the last two poorly controlled by states. All those issues drive a progressive risk increase [

1,

10,

11].

The Ecuadorian government has been actively working to address the impact of landslides on its territory. That is part of their broader strategy to promote sustainable development and ensure the safety and well-being of the population, as outlined in the

Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir 2017-2021 [

12] and subsequent planning initiatives, as a broader strategy to promote sustainable development. Some of those activities are pursuing an integrated approach to risk reduction by focusing on sustainability and resilience from updating building codes (it is close to presenting the new 2024 release of the Ecuadorian normative of construction), renovating the baseline information on zoning hazard areas, and developing methodological guidelines for land use planning. Ecuador has a decentralized system of organization where the provincial, canton, and parish GAD (Decentralized Autonomous Government, in Spanish abbreviation) manage and are responsible for risk reduction and their definition into each territory. That aims to develop a local capacity integrated with local policies and strategies. However, technical capacity needs to be improved and strengthened without specialized technicians. There is also a need to increase seismic vulnerability analysis, reduce structural losses, and preserve lives, including a regulatory and policy framework, technical and engineering solutions, and community education and involvement.

The present work focuses on applying geophysical surveys from the point of view of sustainable management strategies that need the application of easy and low-cost techniques and where the application and resolution of the modelizations or their use in monitoring can address those issues. Some case examples of large landslide events in Ecuador (historical and news) are analyzed to show how geophysical surveys can help give quick information and be a valuable tool to face the mitigation or provide a solution. Thus, the work explores and analyzes the role of the geophysical surveys being leveraged in the sustainability and effective management of landslide problems in Ecuador.

2. Understanding the Landslide Problem in Ecuador

Ecuador has mountainous regions in both flanks of the Andean Cordillera as well as topographical features that confer particular conditions. The presence and development of tropical soils, mostly from recent volcanic eruptions and neo-tectonic activity, contribute to modeling different landscapes prone to landslides [

13,

14,

15].

Over the last decades, Ecuador has suffered significant landslide events, such as those reported in La Josefina, Azuay province (1993), Chunchi, Chimborazo province (2021), Gulag-Marianza and La Cría (

Figure 1), Azuay province (2022), and most recently, Alausí, Chimborazo province (2023). The impact and affectation of those landslides are not limited to rural areas but also to urban ones like El Tejado (Quito), in Pichincha province, with two events in 2022 and 2024 [

16], and the Rio Verde event, Tugurahua province (2024), where debris and mud flow events were also experienced.

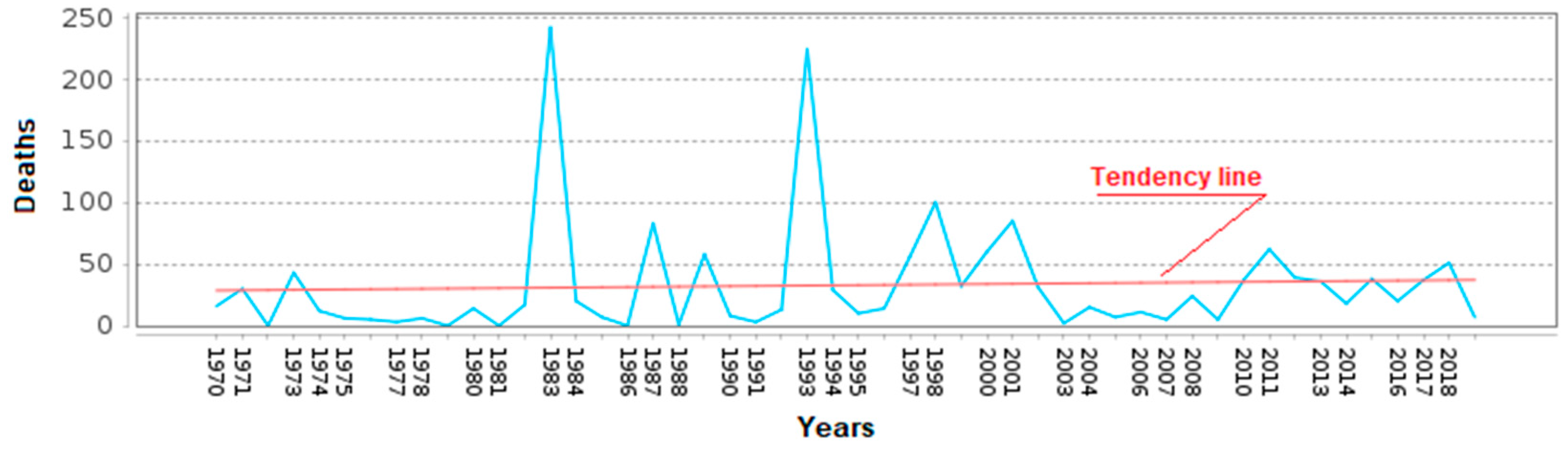

Landslides are an important and dangerous hazard in Ecuador. According to the Desinventar-Sendai database (

www.desinventar.org, accessed on 20 August 2024), the phenomena that generated the most deaths in that country during the period 1970-2019 were landslides, having directly killed more than 1642 people from the landslide mass movement (with a tendency line increasing across the years, see

Figure 2), cause 1481 people to be injured and/or missing, affected 10307 houses (destroyed or damaged), and damaged 1420 kilometers of roads. As an example, from the first of December 2023 to the first days of May 2024, 647 landslide events were reported, five of which produced live losses (ten people died), and in 2 mudflow events, two people were also reported as dead (

https://www.gestionderiesgos.gob.ec/informes-de-situacion-epoca-lluviosa-2022-2023/, accessed on 21 September 2024).

However, the natural environmental contribution to landslide hazards is not alone. Human factors, such as uncontrolled land use and invasion of hazard-prone areas combined with the stepped flanks of mountains, flood river areas, and filled rivers, also play a significant role.

All in all, significant factors that contributed to landslides in Ecuador include:

Heavy rainfall: The climate all over the country experiences two seasons; one of them has intense, fast and prolonged rainy periods, which increases soil saturation.

Seismic activity: Ecuador is located along the Pacific Ring of Fire, an area prone to earthquakes, one common trigger of landslides [

18].

Volcanic activity: The so-called Volcanoes Avenue (named by A. Humbolt in the XIX century) has the presence of active volcanoes and recent soft sediments from their eruptions.

Deforestation and land use: Inappropriate or uncontrolled land use and deforestation practices exacerbate soil nudity and, consequently, the erosion of slopes.

According to Auflič et al. [

19], landslides are more prominent in earth slide type (>50%) with a medium to large size, with deep to very deep failure surfaces (between 5 to 20 m and more than 20 m); a slow motion is reported in more than 65% and same proportion to trigger element (rainfall) and an important 10% for human activity affecting to infrastructural facilities and residential houses (75%). Even though these figures were gathered from European landslides, such characteristics can be applied to Ecuadorian landslides, adding the tectonic characteristics of the country affected by several earthquakes yearly [

20].

3. Geophysical Surveys in Sustainable Management Approaches for Landslide Risk Reduction

Landslide complexities in Ecuador make it necessary to adopt an approach from different ways to conduct proper landslide management. Conducting a landslide risk reduction and affectation effects in a sustainable way includes using early warning systems, planning and regulating land use, keeping ecosystems and the engagement of communities, and engineering intervention through infrastructure construction [

1,

21].

Apart from community and ecosystem approaches, geophysical surveys can play a fundamental role in landslide management, as they can be used in definition, delimitation and investigation of landslides. Geophysical surveys can be a fundamental component of early warning systems, identifying and monitoring prone areas to slide or suffer some kind of movement (even in rock slopes). In land use planning, although based on and supported by surficial and shallow information, in-depth information obtained from geophysical surveys may help define and limit high-risk areas. For infrastructure design, such as slope stabilization, drainage definition, or geological hazards mitigation procedures, where knowledge about geological materials and geotechnical parameters is vital, geophysical surveys complement borehole investigation and laboratory tests while easily covering and providing information on a greater geographical area with low costs.

3.1 Geophysical Surveys as an Investigation Tool

Geophysical surveys can be applied as a complementary source of information together with other investigations and monitoring surveys. They are not limited to a single method but involve diverse methods [

22]. These include seismic, electric, and electromagnetic (EM) methods mainly from the different techniques: refraction, passive or reflection (seismic surveys); electrical resistivity and chargeability measures from vertical electrical soundings (VES) and 2D and 3D electrical tomography (ERT); and, ground-penetrating radar (GPR) or time-domain (TDEM) in the EM method [

8]. Using one or some combined techniques approach allows for gathering detailed information about the subsurface structure of the terrain. That is essential for identifying potential landslide hazard areas and developing effective risk reduction strategies.

The advantages of using geophysical surveys when compared with traditional or mechanical methods (boreholes) for landslide studies in risk reduction include [

3]:

They can provide non-invasive information about the stratigraphy (internal structure of material as layers) and physical properties of ground subsurface geological materials. This helps understand landslide mechanisms and identify potential failure surfaces.

They can be applied over two, three, and even four (over time) dimensions from a variety of methods (seismic, electrical, and electromagnetically-EM) to map the subsurface. This helps to understand better and more comprehensively characterize landslide areas against traditional geological and engineering mapping methods, which are more limited tools.

They cover areas and volumes larger than traditional investigations (which ones are local and point-based, i.e., one-dimensional surveys). This enables them to explore great areas affected by hazards, conduct a widespread investigation, or perform a regional-scale landslide assessment.

However, integrating multiple investigation techniques (geophysical and non-geophysical ones) is essential when developing a proper landslide study and management strategy [

3,

22] since geophysical surveys also suffer some limitations, such as:

Indirect nature of the measuring, as they recall data about physical properties that can be correlated to geotechnical parameters or other material characteristics. Careful data acquisition and interpretation are needed, and although applying several methods or techniques is highly recommended to lessen this fact, direct geological and geotechnical measurements are often needed to calibrate and validate models [

3].

Non-uniqueness of solution in modelizations can be challenging if relying solely on geophysical surveys. It can produce problematic solutions due to the infinite models obtained from a dataset.

Geophysical methods show a typical decreasing resolution with depth due to absorption and/or distortion on the main field. Integration with other direct data techniques and/or geophysical methods is therefore needed.

Overestimation of the reliability and quality of the results can lead to misinterpretations or bad use of the final models by practitioners.

Based on the authors’ experience and the literature [

3,

5,

23,

24],

Table 1 shows the suitability of different techniques used in geophysical surveys to study landslides in rocks and soils (used abbreviations: SP: Self Potential, IP: Induced Polarization, FDEM: Frequency Domain EM, SASW: Spectral Analysis of Surface Waves, MASW: Multichannel Analysis of Surface Waves, ReMi: Refraction Microtremor, HVSR: Horizontal to Vertical Spectral ratio, and SPAC: Spatial Autocorrelation). The primary techniques listed in the first column include artificial field methods and natural field methods, such as gravity and magnetic methods, which have limited application to landslide investigations. The reflection seismic technique has also limitations in terms of its economy (it is too expensive in small size areas or for geotechnical investigation budgets) and the size and depth of the landslide (it is not adequate for shallow ones); however, reflection offers good results when high-definition reflection seismics are applied.

Rock falls landslide typologies (including toppling) are complex systems in defining the survey campaign, even for direct surveys as boreholes, due to discontinuous landslide possibility, i.e., isolated rocks and blocks; therefore, depending on the ground and objectives to be defined, some geophysical techniques could be appropriately applied to their definition.

The applicability of each geophysical technique depends on the measured parameter, the basis of each method, and the correlation with geotechnical or geological parameters. The applicability of a method or technique is subject to what one wants to measure and its characteristics. Size, depth, impedance contrast, and surrounding materials are the most important characteristics that generate good modeling after data processing [

8].

Table 2 gives a comprehensive guide to the related geotechnical parameters, identification of failure surface, and hydrogeological parameters for each technique, as shown in

Table 1. That provides a general idea of those investigating techniques, aiding in understanding and applying each method. Geotechnical parameters can be found through seismic surveys based on the elastic waves analyzed. Electrical and EM methods cannot provide geotechnical parameters but help define geological structures (better than seismic refraction), stratigraphy, moisture, and hydrologic conditions (humidity and aquifer presence, including phreatic levels and flows).

When failure surface definition is sought, seismic techniques can establish that surface depending on sonic impedance contrast. However, a contrast value of up to 2 is required to have good results between geological material layers that separate the mobilized part of the landslide from the fixed one [

8]. Electrical methods also help define failure surfaces by electrical impedance contrast. In this case, the presence of high water content (close to or saturated) or clays could be an exceptional support for identifying it. Particularly, the induced potential (IP) technique enables the separation of water-saturated materials from clayed ones by analyzing the chargeability potential (water can never be charged).

Electrical and EM methods are in fact the most valuable methods for hydrogeology investigations. They can give information about the presence of aquifer layers (phreatic or piezometric) and the percentage of humidity (with previous parametrization of resistivities). The usefulness of SP in subterranean flows and IP in the discrimination of clay materials from saturated sands is remarkable.

Conversely, the natural field methods, i.e., gravity and magnetic ones, have limited application to landslides. This is due to the need for high contrast in measured parameters (variations of potential fields gravimetric and magnetic) as well as the presence of magnetic permeability. For example, very dense grids must use the magnetic method to get useful and accurate results.

3.2 Geophysical Surveys in Landslide Early Warning Systems (LEWS)

Geophysical surveys can be used with other investigation techniques (like remote sensing, monitoring, direct surveys, and topographical data) to provide valuable Landslide Early Warning Systems (LEWS) inputs [

3]. A LEWS can be considered a procedure focusing on vulnerability reduction by measuring different geological, geotechnical, hydrological, and/or geophysical parameters. LEWS can be divided into regional/territorial (great to medium scale) and local (small scale) ones [

25], depending on the slope-scale set. However, both are related to the increasing moisture and precipitation trigger measures.

While geophysical surveys can investigate broad areas, slope-scale applications are more suitable. Surface monitoring by topographical or satellite measures offers a shallow view of the movements, while geophysical surveys can produce internal and deeper information about the structure and parameter variations.

Electrical surveys such as tomography or seismic data acquisition (2D or 3D imaging) can detect changes in parameters such as moisture, porosity, compaction, and internal structure. A good correlation with geotechnical parameters obtained from traditional borehole investigations is needed to achieve satisfactory accuracy in these determinations. This correlation process involves comparing the geophysical data with the physical properties of the soil and rock samples obtained from the borehole investigations, thereby enhancing the reliability of the LEWS. However, these techniques are currently underused mainly by the economic or technical processes needed to install, analyze, and implement a LEWS [

25].

A promising geophysical technique in LEWS uses ambient noise correlation, a seismic passive technique. This technique has a robust processing (stable signal affected by only great changes), improves the time resolution below a day (giving options to implement warnings before the rupture happens), and enables understanding of environmental fluctuations (related to humidity or topographical changes) [

26].

3.3 Engineering Assessing Landslide Risk Reduction

Landslide Risk Reduction (LRR) is composed of Exposure Reduction (ER), which is considered as management, and Hazard Reduction (HR), which is applied as mitigation. The former comprises educational approaches, geographical warnings, and the response to disaster events. The latter focuses on engineering elements at risk, remediating hazards, and removing elements at risk [

27].

The landslide investigation must consider different approaches, from a multi-method for information compilation to reach the LRR. While surface characteristics are typically defined from field morphology mapping [

28] and recently using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) and LiDAR (light detection and ranging) topography [

5], the geotechnical investigations and geophysical surveys apply in the definition of the inner structures, material characteristics, and hydrogeological conditions [

29,

30,

31].

The influencing factors in the LRR in tropical countries must be understood because they are essential inputs, particularly in the last changing climate conditions. These factors, including the absolute physical exposure of people to landslides and prone landslide areas, the population size, and the country’s Human Development Index (HDI), are significantly impacted by climate change. The difficult access conditions to the landslide areas (vegetation and slopes), the lack of geotechnical knowledge, and the insufficient temporally information (due to the reduced statal budgets) can be addressed using geophysics (land and airborne methods), UAV equipment or LiDAR [

32].

Table 3 tries to summarize the assessment methods used to manage and analyze landslide risk events in soil and rock from an engineering point of view. Modelization methods implied a qualitative risk assessment where different risk grades (to assets or human safety) could be defined based on hazards and consequences. They use the Safety Factor (SF) or failure and slide displacement velocity as the main parameters. These methods imply general data observations, which could be obtained from direct surveys (boreholes and laboratory tests) and geophysical surveys as complementary information. Stress-strain methods (finite element method, FEM), as a quantitative risk assessment method through the definition of strains, displacements, and weak zones related to rupture, can also be performed from the same type of data. In contrast, statistical methods need a detailed database, including other additional parameters, such as reliability index, probability of failure, and system reliability, being, together with FEM methods, applicable to both soil and rock landslide types [

1].

4. Analyzed Landslide Case Studies in Ecuador

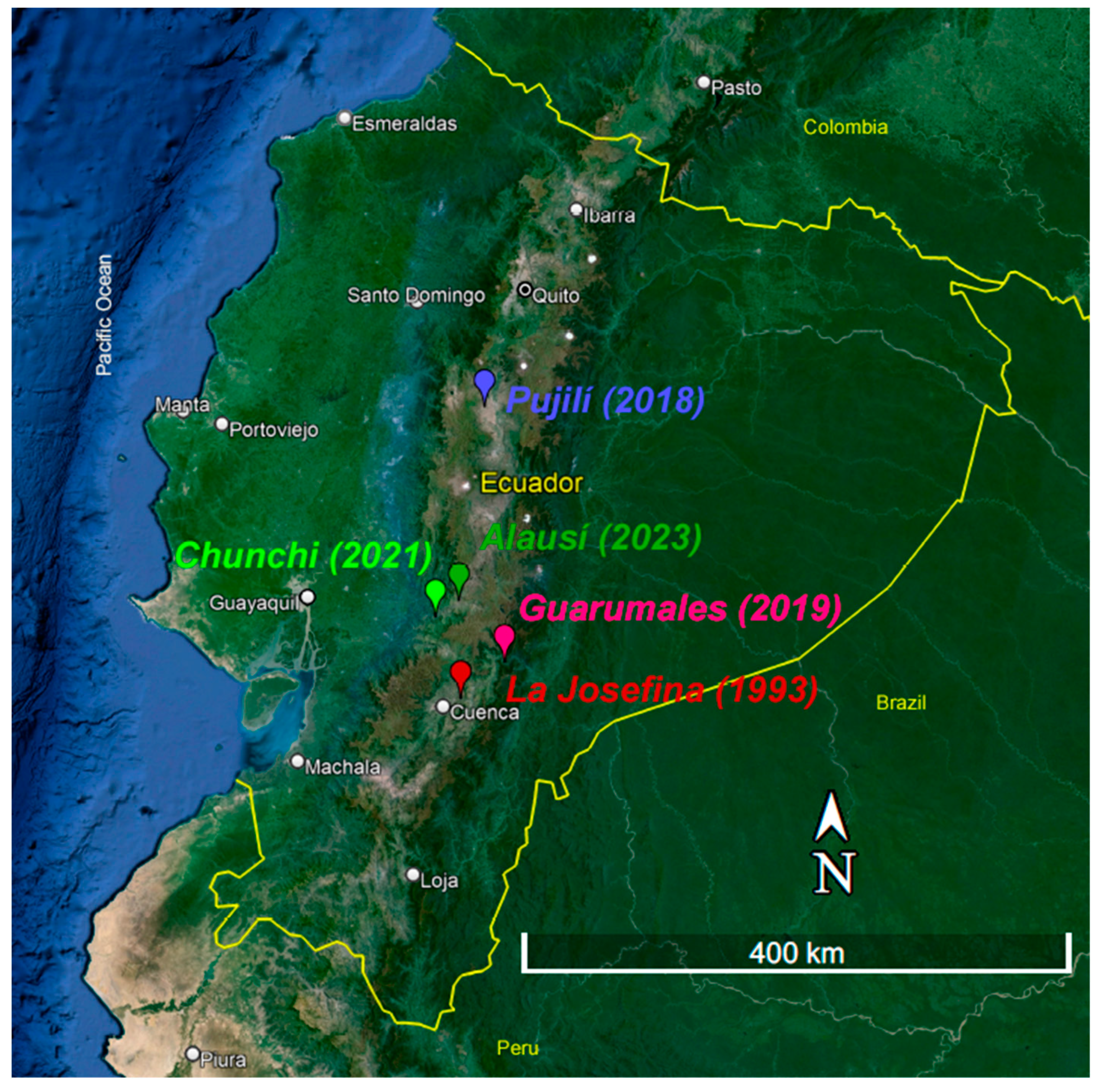

Several case studies of landslides and different approaches and practices in using geophysical surveys can be drawn from Ecuador. Five of the most relevant areas with a sustainable management focus are sequentially analyzed below (

Figure 3) in a way of conducting a systematic comparison of the type and application of geophysical surveys to landslides.

Table 4 lists, for each case study, the Ecuadorian province where the landslide occurred along with the year, size, damages, and injuries, and geotechnical investigations performed. It is interesting to note that the first case study analyzed, La Josefina, which occurred in 1993, is a case where no in-depth studies were conducted due to its size and the hurry-up need to demolish the natural dam that led to the collapse of the surrounding area. The other four case studies have geophysical surveys but no direct investigation (boreholes).

4.1. The La Josefina Case (Azuay Province)

La Josefina landslide is an example of how rainfall and anthropic combination have triggered a macro-landslide where the affectation and consequences of no investigation ended in a catastrophic damage [

33,

34]. In 1991, three years before, some studies warned about the possibility of a landslide in the zone, but no studies, mitigation, or previous decisions were applied before the damage [

34,

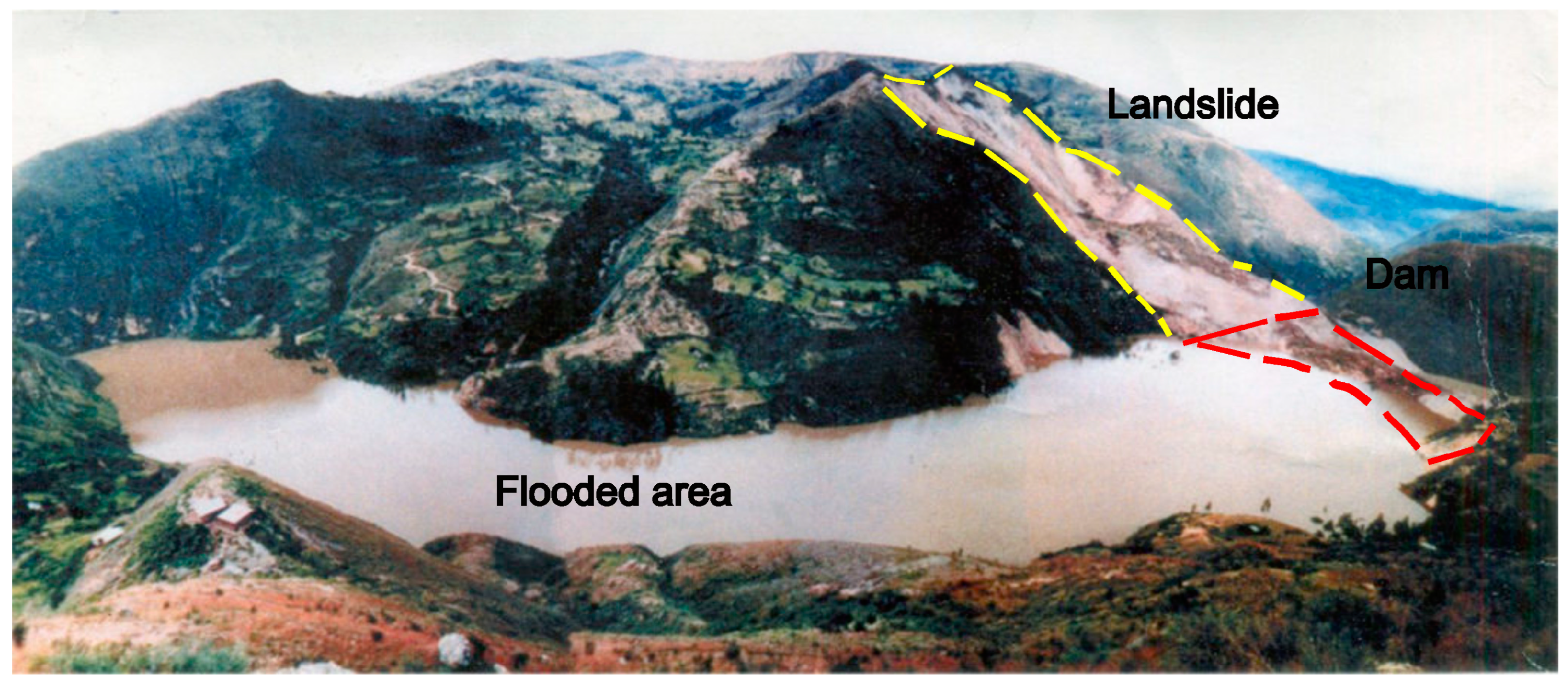

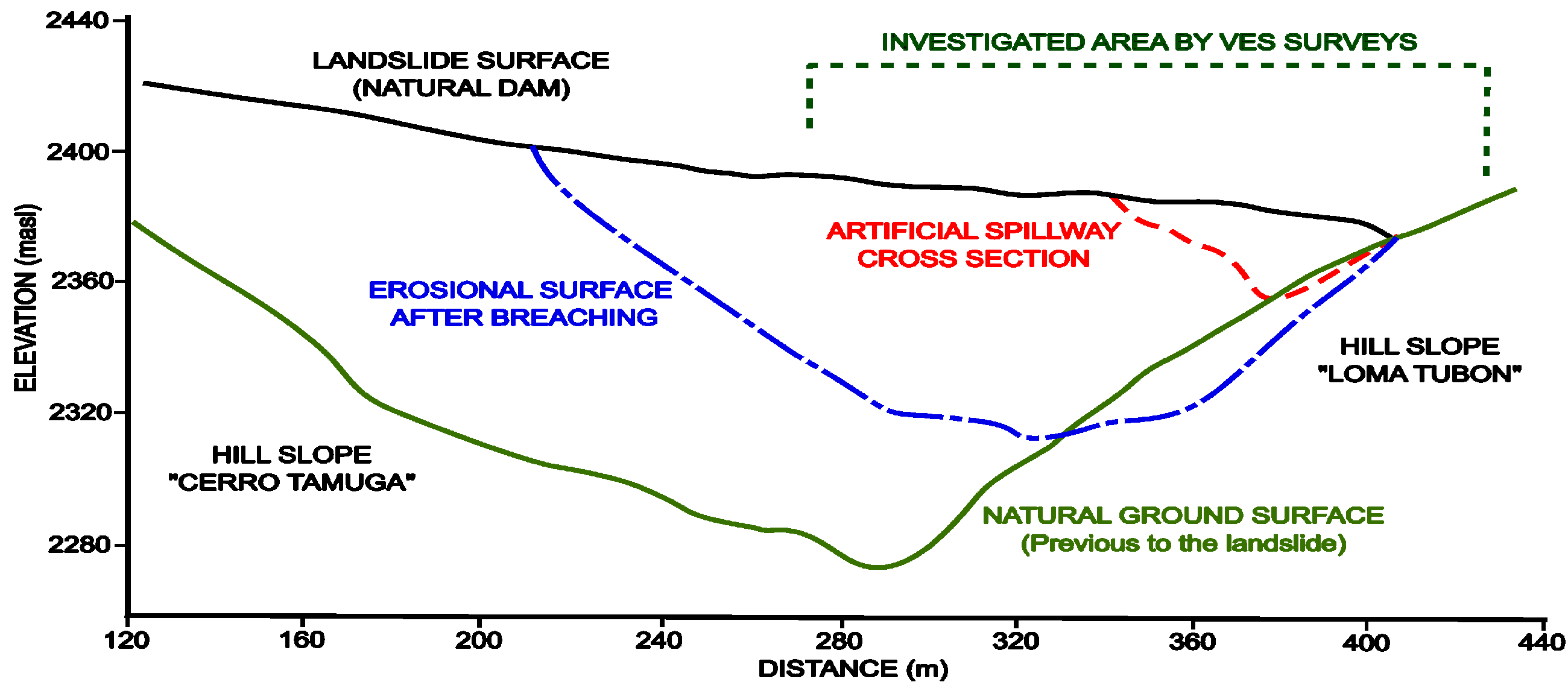

35]. The Tamuga mountainside was rundown in March 1993, creating a natural dam on the Paute River (

Figure 4).

The urgent need to reduce the height of the material blocking the river course (the level of flooded areas increased quickly and occupied backward toward major cities) led to the removal of the fallen sediments by digging an artificial spillway. INECEL government institution performed 12 VES (and probably seismic refraction profiles, not confirmed) over the natural dam to analyze the characteristics of materials (

Figure 5), but the obtained results were scarcely used, and some people considered they were unreliable [

36].

In the 90s, the geophysical surveys remained well-developed in the country, and interpretations could be under the necessary accuracy. Nevertheless, that is a good example where the use of geophysical surveys could have provided valuable knowledge on the initial area that later slid (the landslide had two phases: the upper area moved downhill, and then the mobilized material pushed the rest of the material through the river valley), as well as two years before the event when warnings signals initiated.

Even though the landslide size makes it unstoppable, such evidence might have been used as premonitory advice and preparation for the disaster (alerts, evacuation and ready-to-act processes). As Schneider [

37] indicates, there was a limitation in the linkage between hazard mitigation, community planning, and emergency management, which creates the impossibility of successfully implementing hazard mitigation strategies.

4.2 The Chunchi Case (Chimborazo Province)

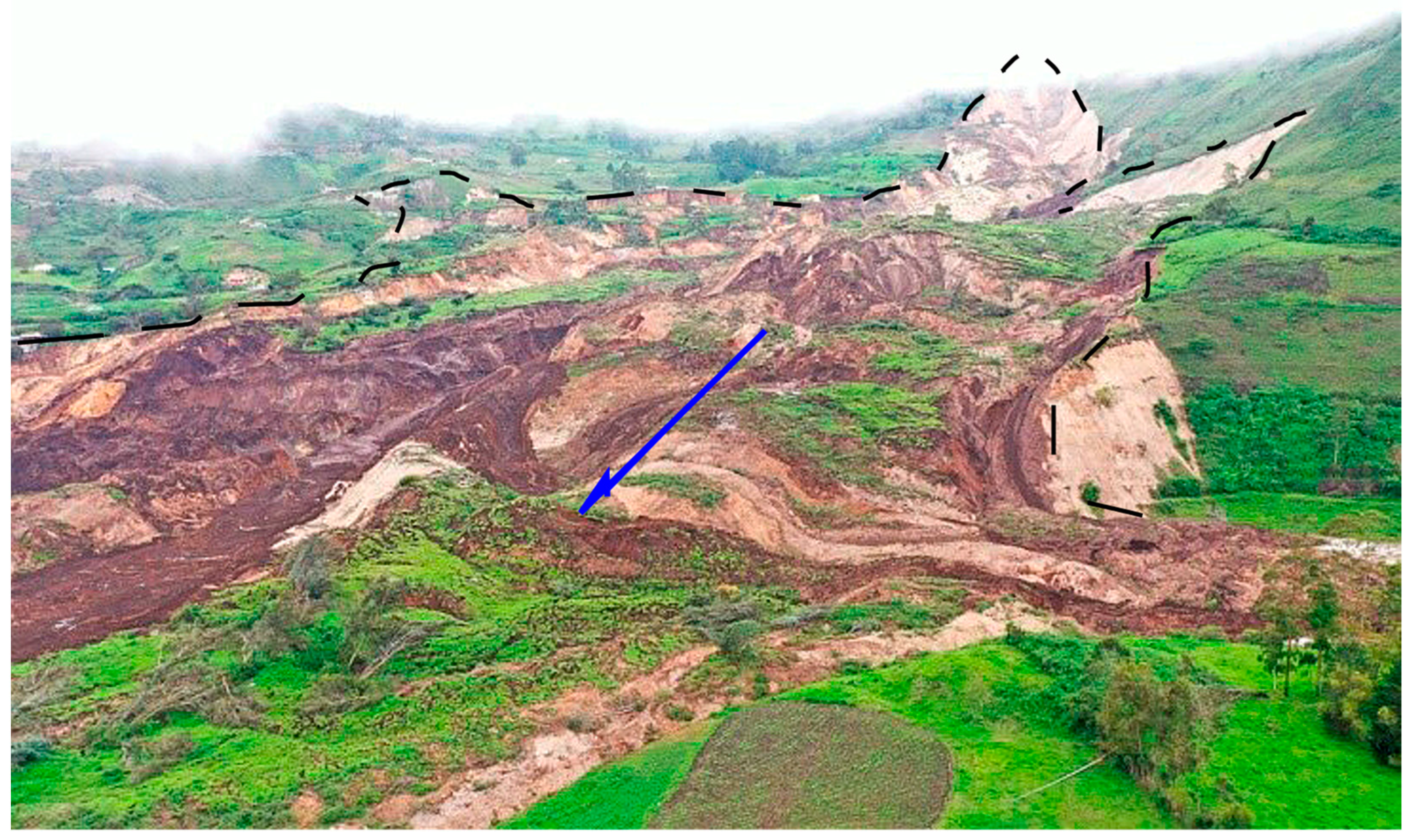

In the La Armenia sector (Chunchi canton), a mass movement affecting an area of 115.35 hectares with a volume of approximately 30 million cubic meters occurred in 2021. This would later temporally dam the Picay River in the Guataxi sector, generating a flow of debris that partially destroyed the Chanchan village (

Figure 6).

Initial observations indicate that the mass movement comprises of three large-magnitude landslides: two rotational slides and one mass-flow type that moved along a fault wedge [

38]. The instability of the ground was mainly conditioned by geological characteristics of the sector, where poorly consolidated soils (area of an old landslide) and residual soils (soil weathering) are observed; hydrogeological characteristics, i.e., presence of groundwater; and steep slopes on the margins of the basin with marks of water erosion which, together with the rains of February 12th 2021 (11 to 19 mm) and the agricultural activities in the area, created a continuous process of the soil mass sliding [

38].

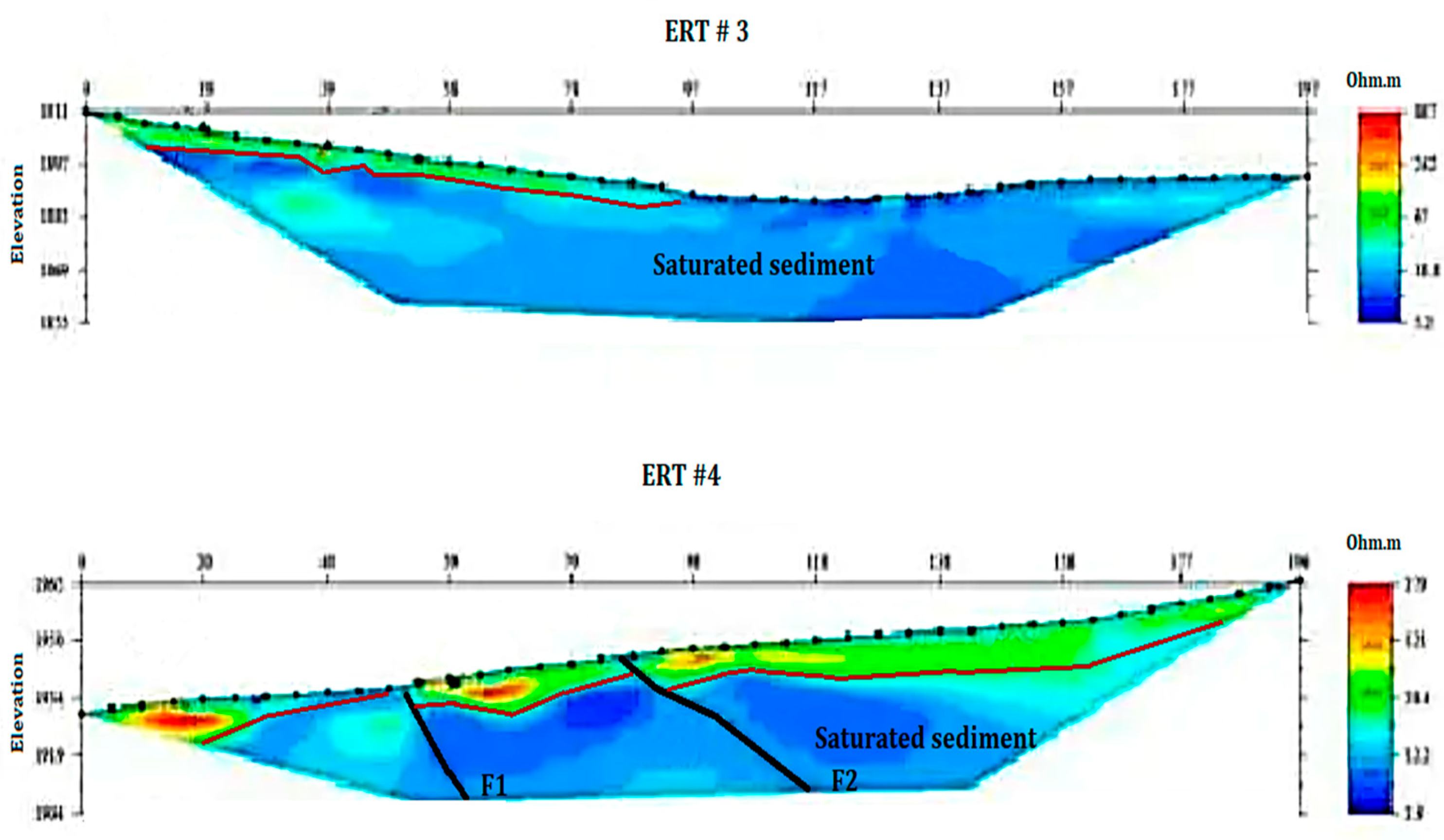

In previous field trips and investigations, the National Risk and Emergency Management Service (SNGRE) evidenced the need for mitigation actions and defined the risk areas to proceed with prevention processes. Such delimitation of the slide area and the characteristics of the materials involved in the near to happen landslide were performed from the application of electrical tomography surveys. In the area, 6 ERT profiles were performed by IIGE and SNGRE institutions (

Figure 7 shows two examples) and they put in evidence the high water content, reaching the saturation at deep levels. That saturation corresponds with an aquifer with low mobility in the water (aquiclude) and faults (F1 and F2 in

Figure 7) inside the body of the mobilized materials as part of the compartmentation of the landslide [

38].

The ERT geophysical technique applied here is a source of information, including the stratigraphy and 2D or even 3D geometric distribution of materials, water content, saturation state, and geological structures (faults and discontinuities). This kind of information can also be used to define the landslide failure surface if the depth of the data reaches it [

39].

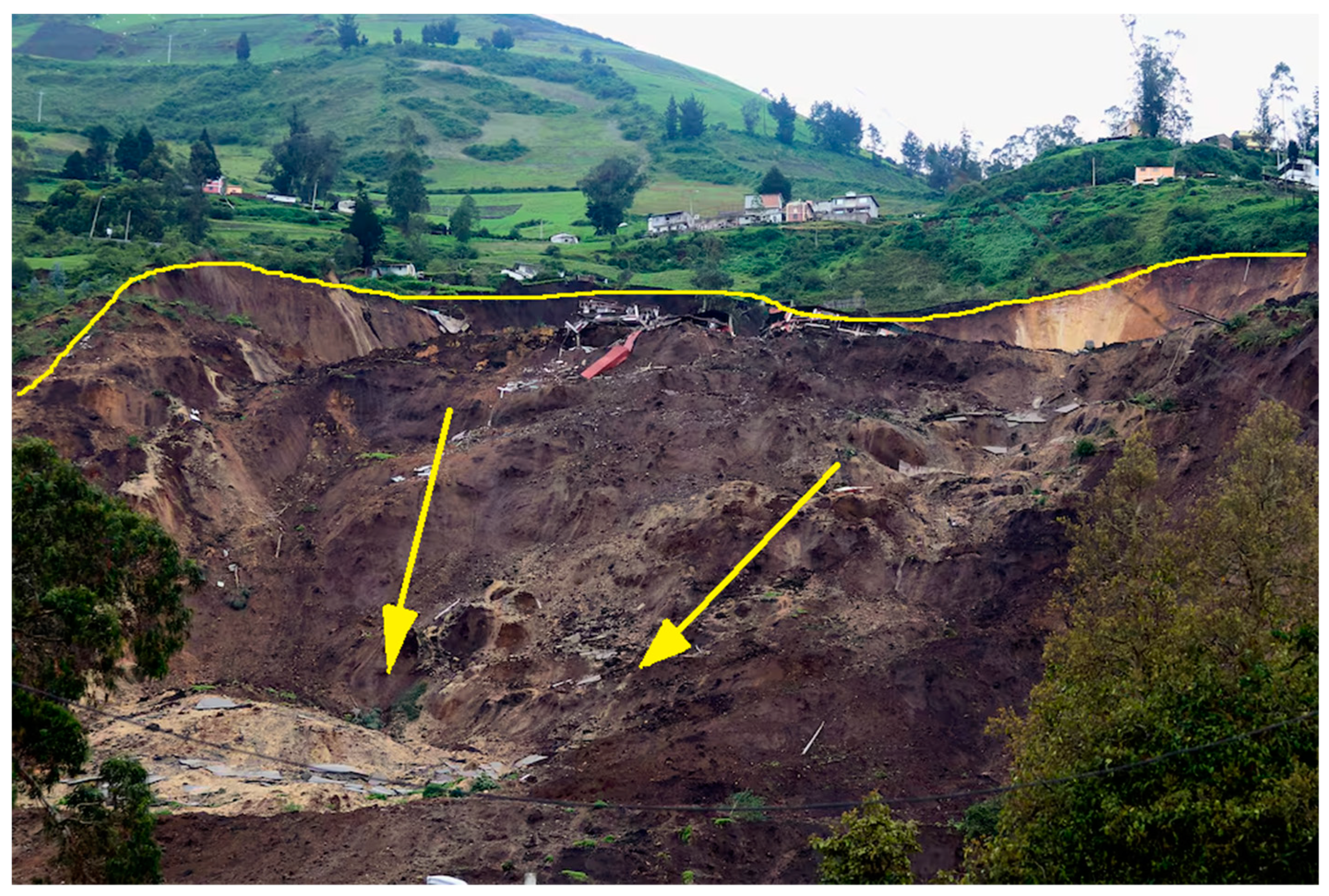

4.3 The Alausí Case (Chimborazo Province)

The Alausí landslide is one of Ecuador’s most recent and still sliding mass movements. On the evening of March 23, 2023, a landslide 380 m wide and 780 m long (more than 125 thousand cubic meters of soil) affected the Alausí village (Chimborazo province). According to official reports from the SNGR [

40], up to this point, the landslide has buried more than 161 homes, leaving 65 people dead, 10 missing, 44 people injured, and more than 800 affected.

Several months before the event happened, some cracks were observed in the area, particularly on the national road E-35. The rainy days and the possible interaction of an earthquake five days before the landslide were the most probable causes of the ground failure [

41,

42].

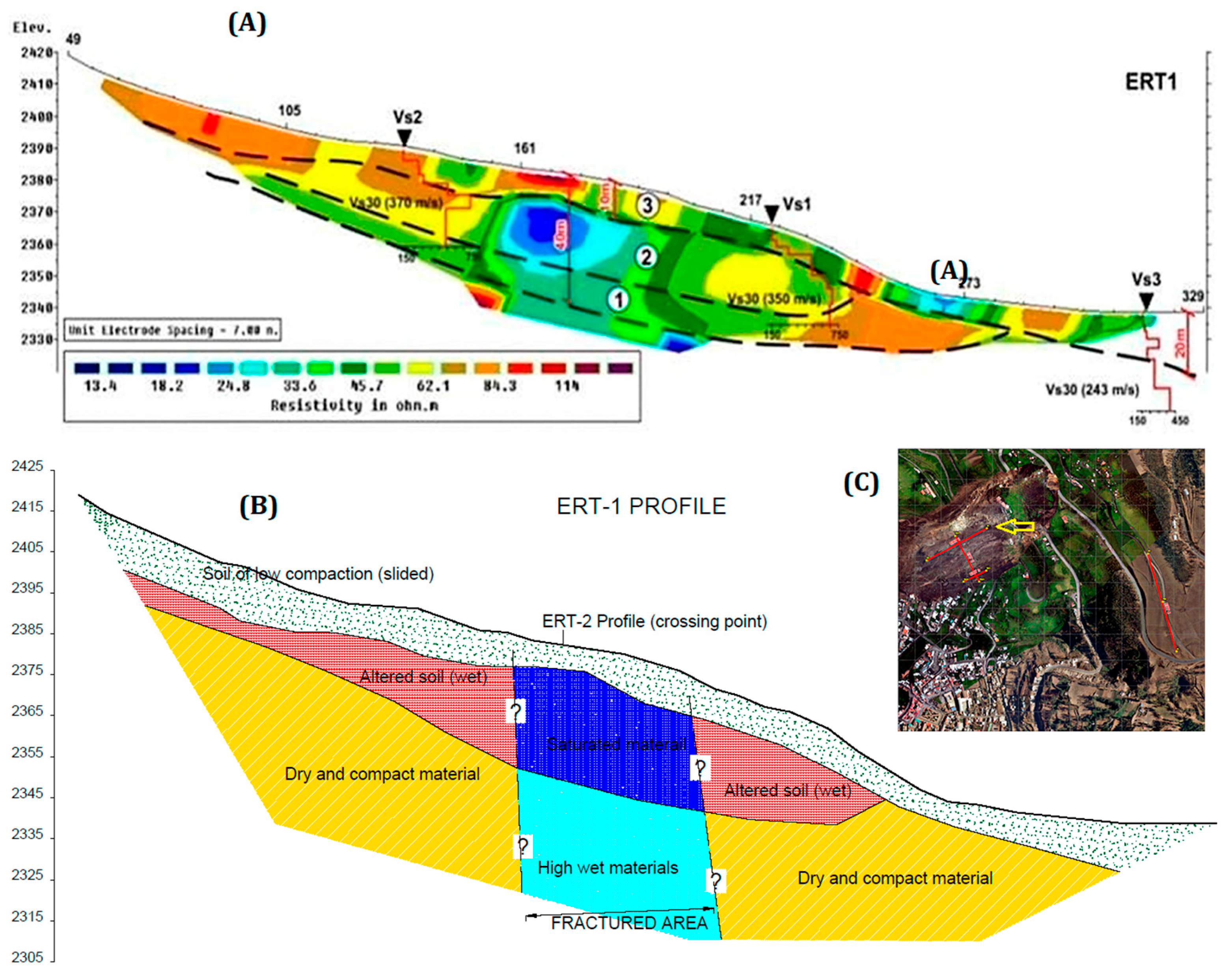

The investigation of the landslide area before and after the event was performed by the Geological and Energy Research Institute (IIGE) and SNGRE [

43]. Two electric tomography profiles were applied before and six more after the failure. MASW seismic technique was also used to separate the mobilized material from the static one (

Figure 9A). The geophysical results provided information about the sediment layer deposited (up to 45 m thick) and the characteristics of the soil resistivity of the bottom along the longitudinal ERT-1 profile (

Figure 9A). A reinterpretation of the geophysical data is made in the present work by the authors (

Figure 9B), also delineating the altered layer of soil (in situ saprolite) and the probable presence of a fault with saturation.

The surroundings of the landslide continue to be unstable. A FIGEMPA Faculty of the Universidad Central del Ecuador team is still working on analyzing new prone-to-slide areas based on topographical measures and geological data [

41].

4.4 The Guarumales Case (Azuay Province)

The area around the Guarumales village (Azuay province) has various landslides affecting infrastructures (roads and hydroelectric dams). Those landslides were triggered by the rainy climate with increasing in time precipitations on a steeped mountain flanks environment with more than 40° inclination [

15].

One of those landslides at Guarumales was investigated by the authors applying a combination of geophysical techniques, particularly seismic and electric methods [

22]. Even though the landslide study was small, it had a transcendental value because the affected road was the unique access to a hydroelectrical machine building.

After an initial release of materials and an urgent remediation action (

Figure 10A), the landslide continued its movement, and a detailed investigation was necessary. The work focused on defining the landslide failure surface, a challenging task due to its continuous movement and the loose and falling stones. Only geophysical surveys were used for that.

Figure 10B shows the obtained longitudinal geologic section along the maximum slope of the landslide. By performing the VES test, the delimitation of the rocky basement (thickness of sediments) and water saturation conditions was achieved, while seismic refraction and MASW techniques enabled the establishment of

Vp and

Vs seismic velocity values and an HVSR single station passive seismic surveys (

Figure 11) was able to delimitate and set the failure surface [

22].

This methodology, which has never been applied before in Ecuador, implied the empirical correlation between sediment thickness and ground natural frequency (

fo) to define a formulation that is extensible to all around the investigated area. In that situation, it is only necessary to obtain the

fo value from the HVSR tests. This geophysical technique is easy, quick, and economical. Measures obtained by this technique can be also used in time series analysis as a monitoring process, where the robustness of HVSR signals might better indicate previous movement than the precipitation analysis [

26].

Moreover, the HVSR

Kg vulnerability index defined by Nakamura [

44] was validated as a valuable tool in the determination of prone-to-landslide areas (

Figure 11), identifying two zones with the highest values (up to 30) where the movement continued and needed new mitigation actions [

22].

4.5 The Pujilí Case (Cotopaxi Province)

The Pujilí canton and surrounding areas are prone to landslide events, being defined in more than 40 potential zones to suffer a mass movement. Cangahua Formation, a recent volcanic sedimentary hard soil, overlays a Paleozoic basement in this area. These types of materials are easily weathered at shallow levels, leading to a high susceptibility to slide [

45].

Near Cachi Alto village, over a small landslide located inside a big one (

Figure 12), partially stable, the authors performed an investigation using natural vibration of the ground measured by HVSR surveys as a first technique [

46]. More than 80 single stations were performed to delimitate the mobilized materials from the static ones. From the ground natural frequency (

fo) and the sediment’s shear-wave velocity averaged over the whole sedimentary soft material above the static materials considered as the basement, the soft sediment thickness was computed by applying the formulation shown in Nakamura [

44]. That shear-wave velocity was obtained using the MASW seismic technique, which can be applied to every measured HVSR point (

Figure 13A). In this case study, failure surface was obtained from three methodologies based on the geophysical surveys performed. Differences between them were established as minimum values (

Figure 13B).

Figure 13A shows a complementary analysis of the directivity of HVSR signals. This enables the establishment of the direction of the movement of every block in the landslide and also sets the internal cracks that section the mobilized mass (blue arrows in

Figure 13A). The statistical analysis of those directivities in the frequency of appearance gives the direction and sense of the motion (rose diagram in

Figure 13A) and also defines new areas prone-to-slide by applying the same

Kg parameter that was used in the previous case study [

46].

5. Discussion

The surficial geology in Ecuador is dominated by volcano-sedimentary sediments from recent geomorphological events (eruptions, erosion, and fluvial processes). Those materials can develop a great soft thickness overburden that is prone to weathering and alteration in their geotechnical properties. Besides, the two climate seasons (rainy and drought) increased by global climate change have modified the static stability of those geological materials in high steep slopes’ topography [

13,

15,

45].

The use of integrated techniques involving the geophysical surveys has demonstrated to accurately define the failure surface. In the Loja basin, a multi-method approach using geotechnical and mineralogical parameters and rain time series could identify the importance of smectites and their expansivity as a conditional factor in the mobilization. Those delineate the low-rate slide materials with the support of ERT profiles [

47]. The Pujilí landslide [

46] is another example of the use of basic geotechnical parameters supporting and constraining the geophysical modeling. In that case, seismic active and passive techniques were combined to set the failure surface using three different approaches.

In locations and geology where the geophysical investigation can be difficult to access and application, areas uprising techniques such as Differential Interferometry Synthetic Aperture Radar (DInSAR) is a helpful tool to perform analysis in real time series and apply a LEWS to preserve infrastructures and lives [

48]. That type of monitoring can be also implemented by other geophysical techniques or used for the identification of sliding-prone areas using the Vulnerability Index (

Kg) as an indication of hazardous areas [

22].

In the last few years, investigations and studies in different cases developed in Ecuador were conducted using other approaches related to geophysical measures, although these were noted and considered here. Those new techniques are related to telemetry, i.e., the measure from space or over the Earth’s surface, and involve the use of:

Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS): Photogrammetric techniques were applied to study and characterize landslides in Ecuador to characterize and analyze landslide evolution in intramountain areas [

49,

50].

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle - Structure from Motion (UAV-SFM): 4D mapping was applied to study and monitor landslides in Ecuador and was also used to monitor landslides in steep terraced agricultural areas, providing valuable insights for early warning systems [

51,

52].

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Remote Sensing: Both technologies have been integrated to identify micro-scale landforms of landslides and monitor landslide dynamics [

49].

Integrating those techniques and their data with other geospatial and environmental data, especially complemented by detailed studies such as boreholes and surface-applied geophysical surveys, enables the practitioners to gain a more comprehensive understanding of landslide dynamics. Thus, a more effective risk management strategy is expected to be developed in the future [

29].

To address the sustainable management of landslides in Ecuador, an approach that adopts and incorporates strategies from long and short-term planning is necessary. The last lines of investigation must incorporate the new approaches in LEWS and monitoring through geophysical technique applications, which can produce valuable information in maintenance or mitigation strategies. Those inputs must be a tool to translate the land use planning to improve infrastructure and building conditions in considering the risks and hazards affecting the zones. This will result in a solid development for the growth of communities and the expansion of the cities.

Besides, the communities must be involved in those actions and activities. Installing monitoring or recurrent measures in controlling the landslide risk areas is an important source of engaging the local communities with government activities and a way to incorporate them into the education processes (schools, colleges, and people) and share the knowledge of living with disaster events.

Resilience is fundamental for social sustainability and enabling communities to cope with disasters, and these are related to technical knowledge, which comes from geotechnical studies and geophysical data as primary information and investigation elements. That also permits communities to adapt and plan in changing conditions.

The Andean Cordillera that crosses Ecuador is experiencing an increasing number of landslides that demand deep behavior from scientific and policy approaches. The policy design and implementation of mitigation strategies need specific local adaptations but face a complicated situation where political cycles, institutional gaps, and informal land uses mark handicaps in the correct applications. Moreover, the uncertainty of a changing climate (considered global but increased locally) means that the adaptation capacity needs to be increased [

53].

6. Conclusions

The last landslides that affected the Ecuadorian territory and their losses (including lives) pose a significant threat to be facing by the government. Adopt new sustainable management approaches, where the geophysical surveys are a fundamental tool to investigate and to mitigate their impacts, are the way to reduce risk and get resilience in next years.

Including various geophysical techniques in combination with the aerial and/or terrestrial methods in implementing LEWS or using them to strengthen the foundation of the infrastructures and buildings is a novel and useful application.

Advanced technologies such as RPAS photogrammetric products, UAV-Structure from Motion (SfM) 4D mapping, GIS, and remote sensing can provide valuable insights and support effective risk management strategies. Those aerial methods must be confirmed and specified accurately by applying terrestrial techniques such as direct borehole studies and geophysical surveys.

Technical, social, and economic considerations must be integrated into the approach to the sustainable management of landslides. By leveraging geophysical surveys, the reduction of risk and the impact of the landslides can be achieved, including community engagement, infrastructure development, monitoring and maintenance, and the economic and environmental considerations of communities. At the same time, natural ecosystems are preserved and social sustainability promoted. Thus, Ecuador can reduce the landslide risk and increase the safety and well-being of its population through geophysical surveys.

Sustainable landslide management in Ecuador must be addressed by a multifaceted approach that combines improving models and achieving greater accuracy with land use strategies and mitigation processes. That can be achieved by applying traditional geophysical techniques (ERT, refraction seismic, VES, or GPR) with emerging ones (DInSAR, HVSR, or RPAS-based) as a source of knowledge that complements the direct data (boreholes and laboratory test) or could be used as continuous monitoring at moving masses. Most of these techniques, combined or isolated, were yet implemented in the landslide investigation in Ecuador, evidencing that they can improve the hazard characterization, lead to mitigation solutions, and promote the communities’ information to be safer and more resilient when facing those natural events.

Supplementary Materials

No supplementary materials are added.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Olegario Alonso-Pandavenes, Francisco Torrijo Echarri and Julio Garzón-Roca; Data curation, Francisco Torrijo Echarri and Julio Garzón-Roca; Formal analysis, Francisco Torrijo Echarri; Investigation, Olegario Alonso-Pandavenes, Francisco Torrijo Echarri and Julio Garzón-Roca; Methodology, Olegario Alonso-Pandavenes; Supervision, Francisco Torrijo Echarri and Julio Garzón-Roca; Validation, Olegario Alonso-Pandavenes, Francisco Torrijo Echarri and Julio Garzón-Roca; Visualization, Olegario Alonso-Pandavenes; Writing – original draft, Olegario Alonso-Pandavenes, Francisco Torrijo Echarri and Julio Garzón-Roca; Writing – review & editing, Olegario Alonso-Pandavenes, Francisco Torrijo Echarri and Julio Garzón-Roca. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data can be revised by email solicitation to authors.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the MDPI Sustainability journal editors who made possible that article with their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Flentje, P.; Chowdhury, R. Resilience and Sustainability in the Management of Landslides. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Engineering Sustainability 2018, 171, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadi, H.; Petrescu, D.C.; Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Ozunu, A. Special Issue: Environmental Risk Mitigation for Sustainable Land Use Development. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongmans, D.; Garambois, S. Geophysical Investigation of Landslides: A Review. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 2007, 178, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazzi, V.; Morelli, S.; Fanti, R. A Review of the Advantages and Limitations of Geophysical Investigations in Landslide Studies. International Journal of Geophysics 2019, 2019, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Y.; Schlögel, R.; Innocenti, A.; Hamza, O.; Iannucci, R.; Martino, S.; Havenith, H.-B. Review on the Geophysical and UAV-Based Methods Applied to Landslides. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pandavenes, O.; Torres, G.; Torrijo, F.J.; Garzón-Roca, J. Basement Tectonic Structure and Sediment Thickness of a Valley Defined Using HVSR Geophysical Investigation, Azuela Valley, Ecuador. Bull Eng Geol Environ 2022, 81, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pandavenes, O.; Andrade-Mendoza, C.; Torrijo-Echarri, F.J. La Investigación Geofísica En Los Estudios de Balsas de Relaves: Su Aplicación e Inclusión En El ACUERDO Nro. MERNNR-MERNNR-2020-0043-AM de La República de Ecuador. Figempa 2023, 16, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Pandavenes, O. Técnicas de sísmica pasiva HVSR aplicadas a la geotecnia. Aplicación al estudio de Movimientos en Masa en la Planificación Territorial e Infraestructura Civil en Ecuador. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València. Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos: Valencia, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett, T.A.; Blizard, C.; Isacks, B.L. Andean Landslide Hazards. In Geomorphological Hazards in High Mountain Areas; Kalvoda, J., Rosenfeld, C.L., Eds.; The GeoJournal Library; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1998; ISBN 978-94-010-6200-8. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, F.; Zerathe, S.; Schwartz, S.; Mathieux, B.; Benavente, C. Inventory of Large Landslides along the Central Western Andes (ca. 15°–20° S): Landslide Distribution Patterns and Insights on Controlling Factors. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 2022, 116, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos-Mora, S.L.; Rodriguez-Galiano, V.; Lima, A. Analysis of Landslide Explicative Factors and Susceptibility Mapping in an Andean Context: The Case of Azuay Province (Ecuador). Heliyon 2023, 9, e20170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SENPLADES Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir 2017-2021 2017. https://www.gobiernoelectronico.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2017/09/Plan-Nacional-para-el-Buen-Vivir-2017-2021. 22 September.

- Aspden, J.A.; Litherland, M. The Geology and Mesozoic Collisional History of the Cordillera Real, Ecuador. Tectonophysics 1992, 205, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltorti, M.; Ollier, C.D. Geomorphic and Tectonic Evolution of the Ecuadorian Andes. Geomorphology 2000, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgilez Vinueza, A.; Robles, J.; Bakker, M.; Guzman, P.; Bogaard, T. Characterization and Hydrological Analysis of the Guarumales Deep-Seated Landslide in the Tropical Ecuadorian Andes. Geosciences 2020, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, L.; Torrijo, F.J.; Ibadango, E.; Pilatasig, L.; Alonso-Pandavenes, O.; Mateus, A.; Solano, S.; Cañar, R.; Rondal, N.; Viteri, F. Analysis of the Impact Area of the 2022 El Tejado Ravine Mudflow (Quito, Ecuador) from the Sedimentological and the Published Multimedia Documents Approach. GeoHazards 2024, 5, 596–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Encalada, S.I. Análisis del macro deslizamiento suscitado en la comunidad La Cría del cantón Santa Isabel, provincia de Azuay. Master Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador: Portoviejo, Manabí. Ecuador, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Román-Herrera, J.C.; Rodríguez-Peces, M.J.; Garzón-Roca, J. Comparison between Machine Learning and Physical Mo-dels Applied to the Evaluation of Co-Seismic Landslide Hazard. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auflič, M.J.; Herrera, G.; Mateos, R.M.; Poyiadji, E.; Quental, L.; Severine, B.; Peternel, T.; Podolszki, L.; Calcaterra, S.; Kociu, A.; et al. Landslide Monitoring Techniques in the Geological Surveys of Europe. Landslides 2023, 20, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibaldi, A.; Ferrari, L.; Pasquarè, G. Landslides Triggered by Earthquakes and Their Relations with Faults and Mountain Slope Geometry: An Example from Ecuador. Geomorphology 1995, 11, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.G.; Holcombe, L. Sustainable Landslide Risk Reduction in Poorer Countries. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Engineering Sustainability 2006, 159, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pandavenes, O.; Torrijo, F.J.; Garzón-Roca, J.; Gracia, A. Early Investigation of a Landslide Sliding Surface by HVSR and VES Geophysical Techniques Combined, a Case Study in Guarumales (Ecuador). Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Kruse, J.-E.; Garcia, A.; Glade, T.; Hördt, A. Subsurface Investigations of Landslides Using Geophysical Methods: Geoelectrical Applications in the Swabian Alb (Germany). Geogr. Helv. 2006, 61, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Gómez, A.M.; Tijera Carrión, A.; Ruiz Bravo, R. Utilización de Técnicas Geofísicas En La Identificación de Deslizamientos de Ladera. CEDEX Ingeniería Civil 2014, 175, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, J.S.; Watlet, A.; Kendall, J.M.; Chambers, J.E. Brief Communication: The Role of Geophysical Imaging in Local Landslide Early Warning Systems. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 3863–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton, M.; Bontemps, N.; Guillemot, A.; Baillet, L.; Larose, É. Landslide Monitoring Using Seismic Ambient Noise Correlation: Challenges and Applications. Earth-Science Reviews 2021, 216, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.G. A Strategic Approach to Landslide Risk Reduction. International Journal of Landslide and Environment 2014, 2, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Travelletti, J.; Malet, J.-P. Characterization of the 3D Geometry of Flow-like Landslides: A Methodology Based on the Integration of Heterogeneous Multi-Source Data. Engineering Geology 2012, 128, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissak, C.; Bartsch, A.; De Michele, M.; Gomez, C.; Maquaire, O.; Raucoules, D.; Roulland, T. Remote Sensing for Assessing Landslides and Associated Hazards. Surv Geophys 2020, 41, 1391–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fressard, M.; Maquaire, O.; Thiery, Y.; Davidson, R.; Lissak, C. Multi-Method Characterisation of an Active Landslide: Case Study in the Pays d’Auge Plateau (Normandy, France). Geomorphology 2016, 270, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cance, A.; Thiery, Y.; Fressard, M.; Vandromme, R.; Maquire, O.; Reid, M.E.; Mergili, M. Influence of complex slope hydrogeology on landslide susceptibility assessment: the case of the Pays d’Auge (Normandy, France). In Proceedings of the Journées Aléas Gravitaires; Besançon, France; 2017; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Thiery, Y.; Kaonga, H.; Mtumbuka, H.; Terrier, M.; Rohmer, J. Landslide Hazard Assessment and Mapping at National Scale for Malawi. Journal of African Earth Sciences 2024, 212, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevallos, O. Lecciones del Deslizamiento “La Josefina” - Ecuador. In Proceedings of the Sistema Nacional para la prevención y atención de desastres de Colombia; Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, February 1994; Vol. A-09; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Harden, C. Sediment Movement and Catastrophic Events: The 1993 Rockslide at La Josefina, Ecuador. Physical Geography 2001, 22, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, G.; Zevallos, O.; Cadier, É. La Josefina Landslide Dam and Its Catastrophic Breaching in the Andean Region of Ecuador. In Natural and Artificial Rockslide Dams; Evans, S.G., Hermanns, R.L., Strom, A., Scarascia-Mugnozza, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; ISBN 978-3-642-04763-3. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza, G.; Zevallos, O. La Josefina: lecciones aprendidas en Ecuador. Desastres y Sociedad.

- Schneider, R.O. Hazard Mitigation and Sustainable Community Development. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 2002, 11, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SNGRE Análisis de nuevas grietas. Cantón Chunchi. Informe Técnico No SNGRE-IASR-08-2021-036; Servicio Nacional de Gestión de Riesgos y Emergencias: Quito, Ecuador, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Perrone, A.; Lapenna, V.; Piscitelli, S. Electrical Resistivity Tomography Technique for Landslide Investigation: A Review. Earth-Science Reviews 2014, 135, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SNGRE Deslizamiento Casual-Alausí. Informe de Situación No 98 (7/11/2023); Servicio Nacional de Gestion de Riesgos y Emergencias: Quito, Ecuador, 2023; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Pilatasig, L.; Ibadango, E.; Troncoso, L.; Mateus, A.; Alulema, R.; Alonso Pandavenes, O. Evaluación del deslizamiento Casual Nuevo Alausí y su zona de influencia; FIGEMPA - Universidad Central del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2023; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- IG-EPN Observaciones sobre el deslizamiento del 26 de marzo del 2023 en Alausí (Provincia de Chimborazo); Instituto Geofísico de la Escuela Politécnica Nacional: Quito, Ecuador, 2023; p. 22.

- SNGRE; IIGE Instituto de Investigación Geológico y Energético Estudio Geológico-Geofísico para generación de datos para estabilidad del deslizamiento de Alausí 26. 03.32023; SNGRE-IIGE: Quito, Ecuador, 2023; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Y. A Method for Dynamic Characteristics Estimation of Subsurface Using Microtremor on the Ground Surface. Quarterly Report of Railway Technical Research 1989, 30, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pilatasig, L.; Bustillos, J.; Jácome, F.; Mariño, D. Evaluación de la Actividad de los Movimientos en Masa de Cachi Alto-Pujilí, Ecuador Mediante Monitoreo Instrumental de Bajo Costo. RP 2022, 49, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pandavenes, O.; Bernal, D.; Torrijo, F.J.; Garzón-Roca, J. A Comparative Analysis for Defining the Sliding Surface and Internal Structure in an Active Landslide Using the HVSR Passive Geophysical Technique in Pujilí (Cotopaxi), Ecuador. Land 2023, 12, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.; Galve, J.P.; Palenzuela, J.A.; Azañón, J.M.; Tamay, J.; Irigaray, C. A Multi-Method Approach for the Characterization of Landslides in an Intramontane Basin in the Andes (Loja, Ecuador). Landslides 2017, 14, 1929–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, P.; Di Napoli, M.; Guerriero, L.; Ramondini, M.; Sellers, C.; Annibali Corona, M.; Di Martire, D. Landslide Awareness System (LAwS) to Increase the Resilience and Safety of Transport Infrastructure: The Case Study of Pan-American Highway (Cuenca–Ecuador). Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate, B.A.; El Hamdouni, R.; Fernández, T. GNSS and RPAS Integration Techniques for Studying Landslide Dynamics: Application to the Areas of Victoria and Colinas Lojanas, (Loja, Ecuador). Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate, B.A.; El Hamdouni, R.; Fernández Del Castillo, T. Characterization and Analysis of Landslide Evolution in Intramountain Areas in Loja (Ecuador) Using RPAS Photogrammetric Products. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, L.; Straffelini, E.; Cucchiaro, S.; Tarolli, P. UAV-SfM 4D Mapping of Landslides Activated in a Steep Terraced Agricultural Area. J Agricult Engineer 2021, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, L.; Cucchiaro, S.; Grigolato, S.; Dalla Fontana, G.; Tarolli, P. Evaluating the Interaction between Snowmelt Runoff and Road in the Occurrence of Hillslope Instabilities Affecting a Landslide-Prone Mountain Basin: A Multi-Modeling Approach. Journal of Hydrology 2022, 612, 128200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Sotomayor, F.; Egas, A.; Teller, J. Land Policies for Landslide Risk Reduction in Andean Cities. Habitat International 2021, 107, 102298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).