Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- bioplastics derived from renewable resources but not biodegradable, e.g., bio-polyamide, bio-polyethylene;

- -

- bioplastics derived from fossil (non-renewable) resources that are biodegradable, e.g., polycaprolactone, poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate);

- -

- bioplastics derived from renewable resources that are biodegradable, e.g., starch, cellulose, collagen, polylactic acid.

2. Results and Discussion

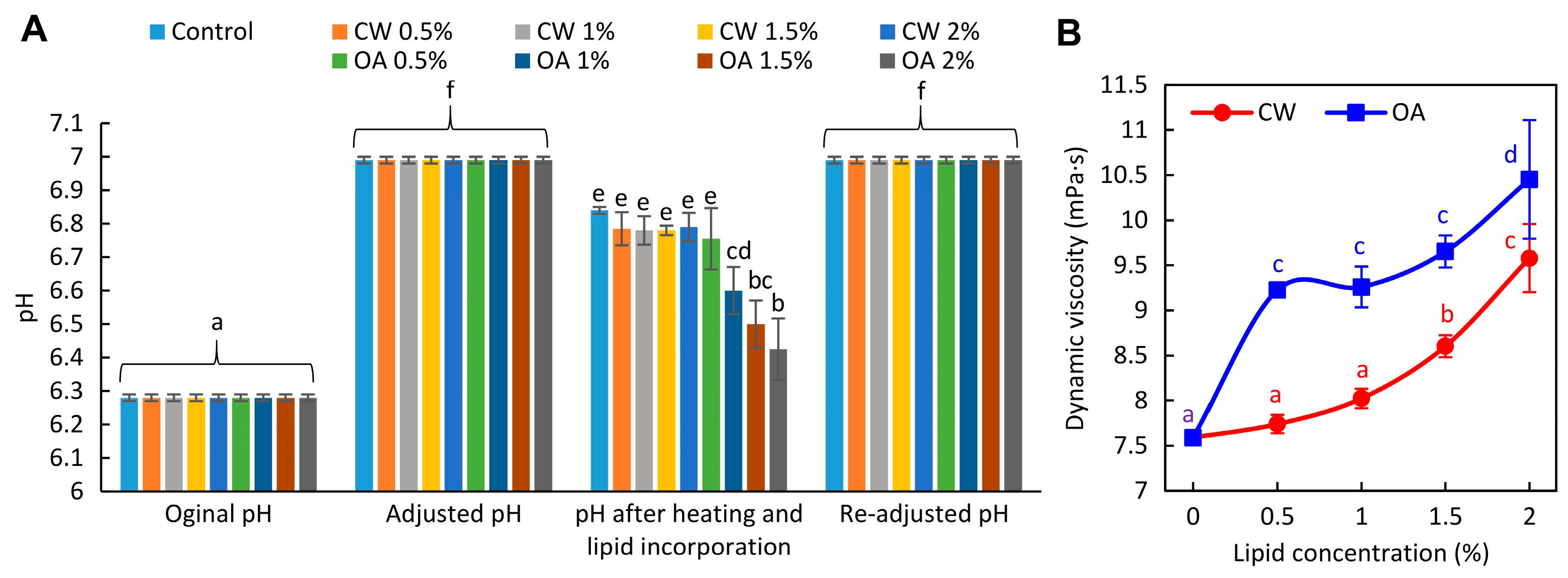

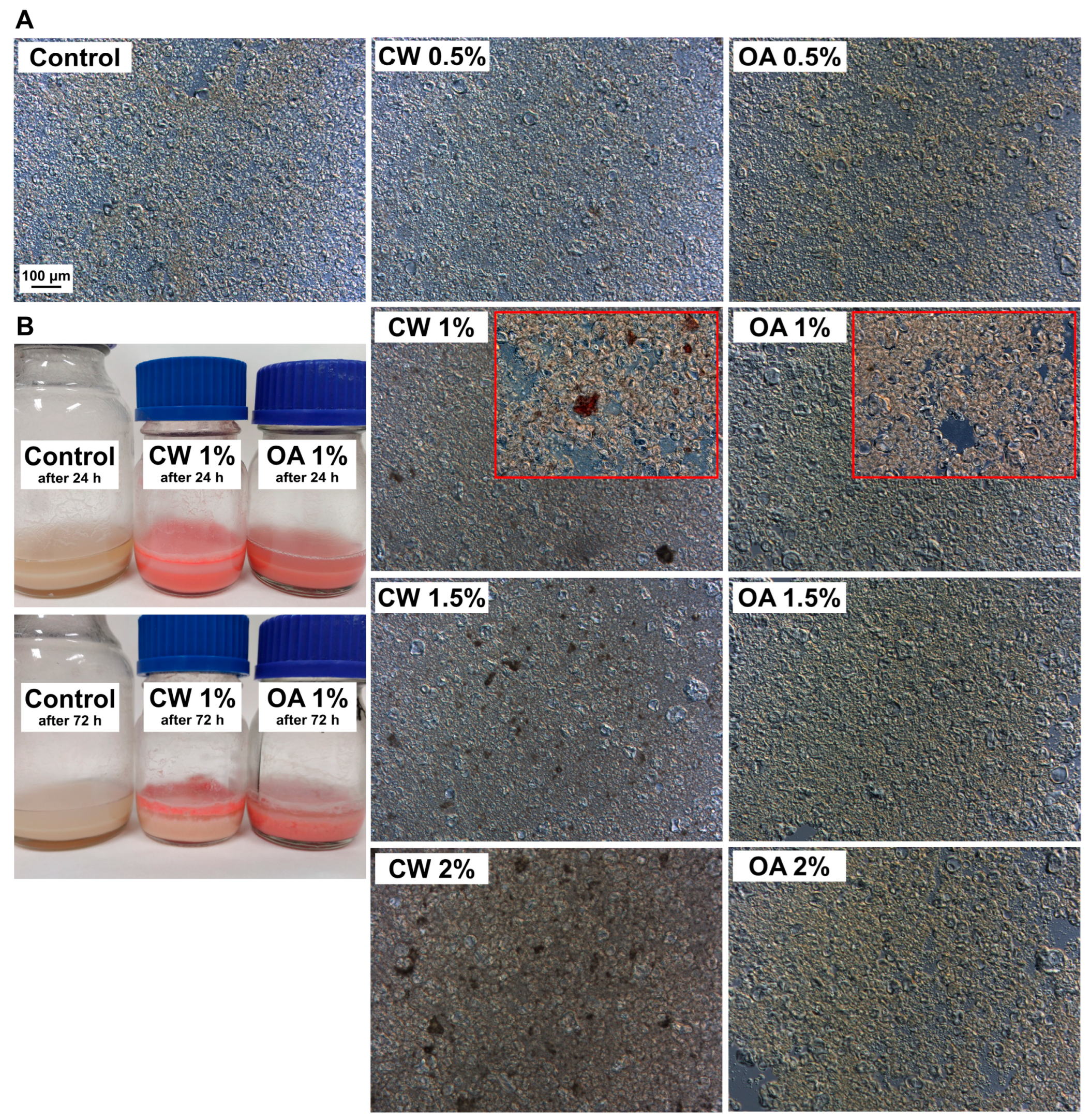

2.1. pH, Microstructure, and Viscosity of Film-Forming Solutions (FFSs)

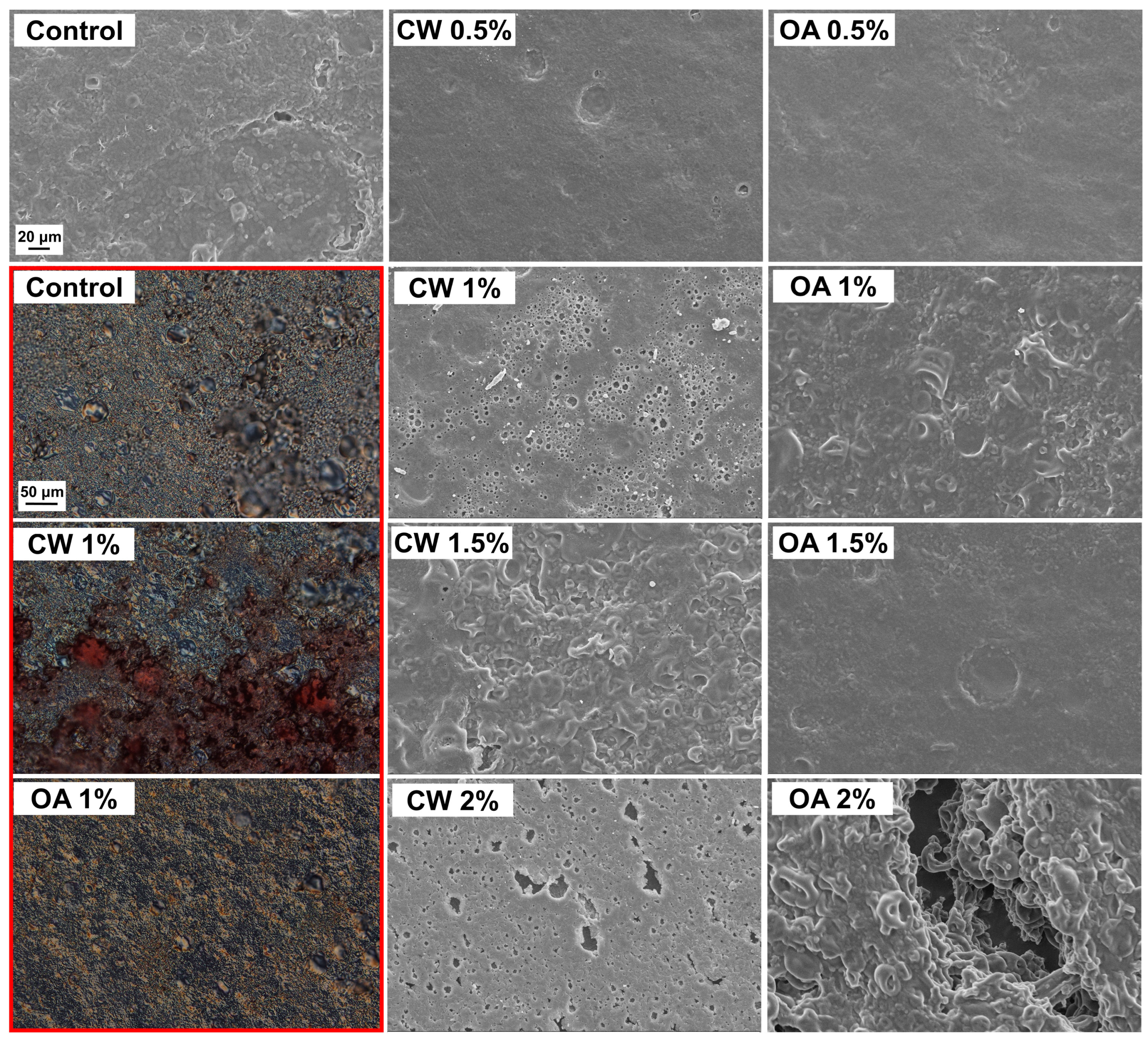

2.2. Microstructure and pH of the Films

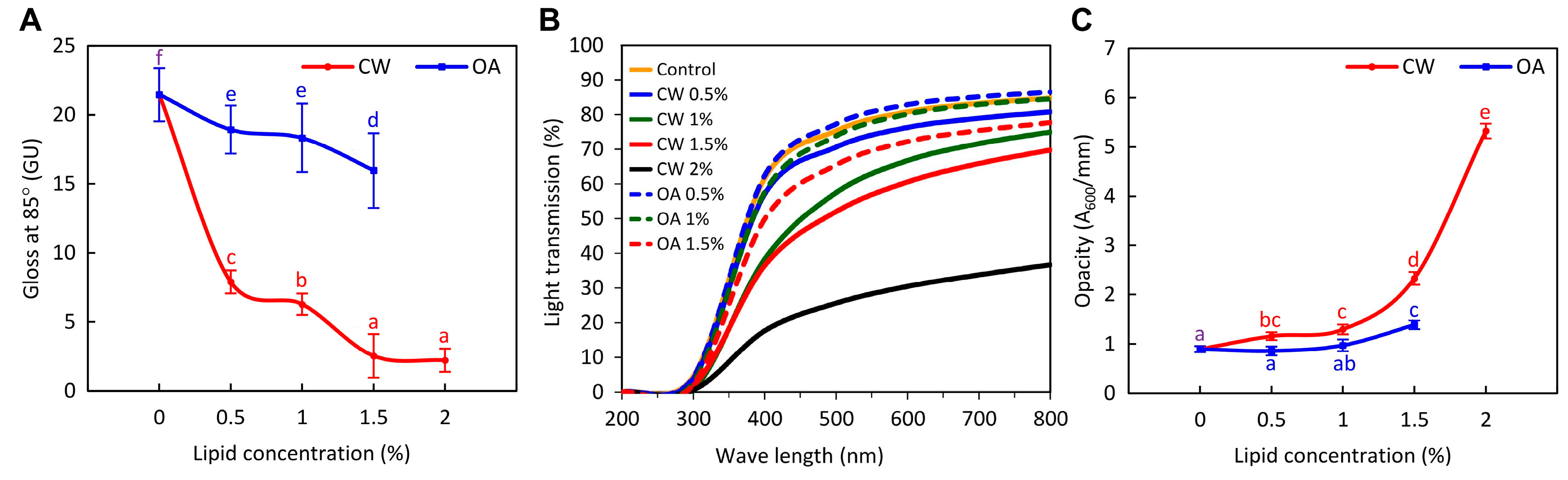

2.3. Optical Properties of the Films

2.4. Water Affinities of the Films

2.5. Mechanical Properties of the Films

2.6. Hot Seal Strength (HSS) of the Films

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Preparation and Conditioning of Films

3.2.2. Characterization of the FFSs

3.2.3. Microstructure of the Films

3.2.4. pH of the Films

3.2.5. Optical Properties

3.2.6. Water Affinities

3.2.7. Mechanical Properties

3.2.8. Heat Sealing Properties

3.2.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dirpan, A.; Ainani, A.F.; Djalal, M. A Review on Biopolymer-Based Biodegradable Film for Food Packaging: Trends over the Last Decade and Future Research. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15, 2781. [CrossRef]

- Zaborowska, M.; Bernat, K. The Development of Recycling Methods for Bio-Based Materials – A Challenge in the Implementation of a Circular Economy: A Review. Waste Management and Research 2023, 41, 68–80. [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.S.; Trafiałek, J.; Kolanowski, W. Edible Packaging: A Technological Update for the Sustainable Future of the Food Industry. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8234. [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on food additives (Text with EEA Relevance). OJ L 354, 31.12.2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02008R1333-20241028.

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Phillips, R.; Milo, R. The Biomass Distribution on Earth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018, 115, 6506–6511. [CrossRef]

- Żyłowski T. Ślad Węglowy Głównych Roślin Uprawnych Polsce. Studia i Raporty IUNG-PIB 2022, 67(21), 25-35. Available online: https://www.iung.pl/sir/zeszyt67_2.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lan, Y. A Comparative Study on Carbon Footprints between Plant- and Animal-Based Foods in China. J Clean Prod 2016, 112, 2581–2592. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Kazimierczak, W. Impact of Calcium Chloride Addition on the Microstructural and Physicochemical Properties of Pea Protein Isolate-Based Films Plasticized with Glycerol and Sorbitol. Coatings 2024, 14, 1116. [CrossRef]

- Shanthakumar, P.; Klepacka, J.; Bains, A.; Chawla, P.; Dhull, S.B.; Najda, A. Molecules The Current Situation of Pea Protein and Its Application in the Food Industry. Molecules 2022, 27(16), 5354. [CrossRef]

- Linares-Castañeda, A.; Sánchez-Chino, X.M.; Yolanda de las Mercedes Gómez y Gómez; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; Martínez Herrera, J.; Cid-Gallegos, M.S.; Corzo-Ríos, L.J. Cereal and Legume Protein Edible Films: A Sustainable Alternative to Conventional Food Packaging. Int J Food Prop 2023, 26, 3197–3213.

- Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Bian, H.; Pan, Y.; Sun, J.; Han, W. Application of Protein-Based Films and Coatings for Food Packaging: A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 2039. [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.A.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Tarahi, M.; Almasi, H.; Chawla, R.; Ali, A.M.M. Insights into Recent Innovations in Barrier Resistance of Edible Films for Food Packaging Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 271, 132354. [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.S.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Lipid Incorporated Biopolymer Based Edible Films and Coatings in Food Packaging: A Review. Curr Res Food Sci 2024, 8, 100720. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gago, M. B.; Krochta J.M. 22 - Emulsion and bi-layer edible films, In Food Science and Technology, Innovations in Food Packaging, Editor(s): Jung H. Han, Academic Press, 2005, pp. 384-402. [CrossRef]

- Scientific Opinion on the Re-Evaluation of Candelilla Wax (E 902) as a Food Additive. EFSA Journal 2012, 10. [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Ledesma, N.E.; Bautista-Hernández, I.; Rojas, R.; Aguilar-Zárate, P.; Medina-Herrera, N. del P.; Castro-López, C.; Guadalupe Martínez-Ávila, G.C. Candelilla Wax: Prospective Suitable Applications within the Food Field. LWT 2022, 159, 113170. [CrossRef]

- Shellhammer, T.H.; Krochta, J.M. Whey Protein Emulsion Film Performance as Affected by Lipid Type and Amount. J Food Sci 1997, 62, 390–394. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Gustaw, W.; Zieba, E.; Lisiecki, S.; Stadnik, J.; Baraniak, B. Microstructure and Functional Properties of Sorbitol-Plasticized Pea Protein Isolate Emulsion Films: Effect of Lipid Type and Concentration. Food Hydrocoll 2016, 60, 353–363. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhai, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, R.; Sun, C.; Wang, W.; Hou, H. Effects of Natural Wax Types on the Physicochemical Properties of Starch/Gelatin Edible Films Fabricated by Extrusion Blowing. Food Chem 2023, 401, 134081. [CrossRef]

- Galus, S.; Gaouditz, M.; Kowalska, H.; Debeaufort, F. Effects of Candelilla and Carnauba Wax Incorporation on the Functional Properties of Edible Sodium Caseinate Films. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 9349. [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G.; Dunn, R.O. A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Melting Points of Fatty Acids and Esters Determined by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2009, 86, 843–856. [CrossRef]

- Kazaz, S.; Miray, R.; Lepiniec, L.; Baud, S. Plant Monounsaturated Fatty Acids: Diversity, Biosynthesis, Functions and Uses. Prog Lipid Res 2022, 85, 101138. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Hu, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. Tara Gum Edible Film Incorporated with Oleic Acid. Food Hydrocoll 2016, 56, 127–133. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemlou, M.; Khodaiyan, F.; Oromiehie, A.; Yarmand, M.S. Characterization of Edible Emulsified Films with Low Affinity to Water Based on Kefiran and Oleic Acid. Int J Biol Macromol 2011, 49, 378–384. [CrossRef]

- Monedero, F.M.; Fabra, M.J.; Talens, P.; Chiralt, A. Effect of Oleic Acid–Beeswax Mixtures on Mechanical, Optical and Water Barrier Properties of Soy Protein Isolate Based Films. J Food Eng 2009, 91, 509–515. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; De Apodaca, E.D.; Cebrián, M.; Villarán, M.C.; Maté, J.I. Effect of the Unsaturation Degree and Concentration of Fatty Acids on the Properties of WPI-Based Edible Films. European Food Research and Technology 2007, 224, 415–420. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-G.; Won, S.-R.; Rhee, H.-I. Oleic Acid and Inhibition of Glucosyltransferase. In Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier, 2010; pp. 1375–1383.

- Arsic, A. Oleic Acid and Implications for the Mediterranean Diet. In The Mediterranean Diet; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 267–274.

- Webb, D.; Dogan, H.; Li, Y.; Alavi, S. Physico-Chemical Properties and Texturization of Pea, Wheat and Soy Proteins Using Extrusion and Their Application in Plant-Based Meat. Foods 2023, 12, 1586. [CrossRef]

- González F. O. C.; González, M. M. P.; Gancedo, J.C.B; Suárez, R. A. Estudio de La Densidad y de La Viscosidad de Algunos Ácidos Grasos Puros. Grasas y Aceites 1999, 50(5), 359-368. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/22004/1/691.pdf.

- Kowalczyk, D.; Baraniak, B. Effects of Plasticizers, PH and Heating of Film-Forming Solution on the Properties of Pea Protein Isolate Films. J Food Eng 2011, 105, 295–305. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Gustaw, W.; Zieba, E.; Lisiecki, S.; Stadnik, J.; Baraniak, B. Microstructure and Functional Properties of Sorbitol-Plasticized Pea Protein Isolate Emulsion Films: Effect of Lipid Type and Concentration. Food Hydrocoll 2016, 60. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, J. Dispersion Process and Effect of Oleic Acid on Properties of Cellulose Sulfate- Oleic Acid Composite Film. Materials 2015, 8, 2346–2360. [CrossRef]

- Mokrzycki,W.S.; Tatol, M. Color Difference ΔE: A Survey. Machine Graphics and Vision 2011, 20(4), 383–411.

- ISO 2813:2014 Paints and Varnishes — Determination of Gloss Value at 20°, 60° and 85°.

- Fabra, M.J.; Jiménez, A.; Atarés, L.; Talens, P.; Chiralt, A. Effect of Fatty Acids and Beeswax Addition on Properties of Sodium Caseinate Dispersions and Films. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1500–1507. [CrossRef]

- Gorji Kandi, S.; Panahi, B.; Zoghi, N. Impact of Surface Texture from Fine to Coarse on Perceptual and Instrumental Gloss. Prog Org Coat 2022, 171, 107028. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Baraniak, B. Effects of Plasticizers, PH and Heating of Film-Forming Solution on the Properties of Pea Protein Isolate Films. J Food Eng 2011, 105. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Mandal, I.; Singh, S.; Paul, A.; Mandal, B.; Venkatramani, R.; Swaminathan, R. Near UV-Visible Electronic Absorption Originating from Charged Amino Acids in a Monomeric Protein. Chem Sci 2017, 8, 5416–5433. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Baraniak, B. Effect of Candelilla Wax on Functional Properties of Biopolymer Emulsion Films - A Comparative Study. Food Hydrocoll 2014, 41, 195–209. [CrossRef]

- Kashiri, M.; Maghsoudlou, Y.; Moayedi, A. Fabrication of Active Whey Protein Isolate/Oleic Acid Emulsion Based Film as a Promising Bio-Material for Cheese Packaging. Food Science and Technology International 2023, 29, 395–405. [CrossRef]

- Norfarahin, A. H.; Sanny, M.; Sulaiman, R.; Nur Hanani, Z.A. Fish Gelatin Films Incorporated with Different Oils: Effect of Thickness on Physical and Mechanical Properties. International Food Research Journal 2018, 25(3), 1036-1043. Available online: http://ifrj.upm.edu.my/25%20(03)%202018/(21).pdf.

- Fabra, M.J.; Jiménez, A.; Atarés, L.; Talens, P.; Chiralt, A. Effect of Fatty Acids and Beeswax Addition on Properties of Sodium Caseinate Dispersions and Films. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1500–1507. [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, F.M.; Martelli, S.M.; Caon, T.; Velasco, J.I.; Buontempo, R.C.; Bilck, A.P.; Innocentini Mei, L.H. The Effect of Fatty Acids on the Physicochemical Properties of Edible Films Composed of Gelatin and Gluten Proteins. LWT 2018, 87, 293–300. [CrossRef]

- Gontard, N.; Duchez, C.; Cuq, J.; Guilbert, S. Edible Composite Films of Wheat Gluten and Lipids: Water Vapour Permeability and Other Physical Properties. Int J Food Sci Technol 1994, 29, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Taqi, A.; Askar, K.A.; Nagy, K.; Mutihac, L.; Stamatin, I. Effect of Different Concentrations of Olive Oil and Oleic Acid on the Mechanical Properties of Albumen (Egg White) Edible Films. Afr J Biotechnol 2011, 10, 12963–12972. [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.S.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Lipid Incorporated Biopolymer Based Edible Films and Coatings in Food Packaging: A Review. Curr Res Food Sci 2024, 8, 100720. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Kordowska-Wiater, M.; Nowak, J.; Baraniak, B. Characterization of Films Based on Chitosan Lactate and Its Blends with Oxidized Starch and Gelatin. Int J Biol Macromol 2015, 77, 350–359. [CrossRef]

- Donhowe, G.; Fennema, O. Water Vapor and Oxygen Permeability of Wax Films. J Am Oil Chem Soc 1993, 70, 867–873. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, T.; Ma, L.; Li, S.; Jiang, W.; Qin, W.; Li, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H. Optimization of Heat-Sealing Properties for Antimicrobial Soybean Protein Isolate Film Incorporating Diatomite/Thymol Complex and Its Application on Blueberry Packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100690. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, G. Synergistic Effect of Oleic Acid and Glycerol on Zein Film Plasticization. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 10075–10081. [CrossRef]

- Bamps, B.; Buntinx, M.; Peeters, R. Seal Materials in Flexible Plastic Food Packaging: A Review. Packaging Technology and Science 2023, 36, 507–532. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, T.; Ma, L.; Li, S.; Jiang, W.; Qin, W.; Li, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H. Optimization of Heat-Sealing Properties for Antimicrobial Soybean Protein Isolate Film Incorporating Diatomite/Thymol Complex and Its Application on Blueberry Packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100690. [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, L.; Salgado, P.R.; Mauri, A.N. Flavored Oven Bags for Cooking Meat Based on Proteins. LWT 2019, 101, 374–381. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, T.; Ma, L.; Li, S.; Jiang, W.; Qin, W.; Li, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H. Optimization of Heat-Sealing Properties for Antimicrobial Soybean Protein Isolate Film Incorporating Diatomite/Thymol Complex and Its Application on Blueberry Packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100690. [CrossRef]

- Tai, J.; Chen, K.; Yang, F.; Yang, R. Heat-sealing Properties of Soy Protein Isolate/Polyvinyl Alcohol Film Made Compatible by Glycerol. J Appl Polym Sci 2014, 131. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ustunol, Z. Thermal Properties, Heat Sealability and Seal Attributes of Whey Protein Isolate/ Lipid Emulsion Edible Films. J Food Sci 2001, 66, 985–990. [CrossRef]

- Janjarasskul, T.; Tananuwong, K.; Phupoksakul, T.; Thaiphanit, S. Fast Dissolving, Hermetically Sealable, Edible Whey Protein Isolate-Based Films for Instant Food and/or Dry Ingredient Pouches. LWT 2020, 134, 110102. [CrossRef]

- Tongnuanchan, P.; Benjakul, S.; Prodpran, T.; Pisuchpen, S.; Osako, K. Mechanical, Thermal and Heat Sealing Properties of Fish Skin Gelatin Film Containing Palm Oil and Basil Essential Oil with Different Surfactants. Food Hydrocoll 2016, 56, 93–107. [CrossRef]

- Nafchi, A.M.; Nassiri, R.; Sheibani, S.; Ariffin, F.; Karim, A.A. Preparation and Characterization of Bionanocomposite Films Filled with Nanorod-Rich Zinc Oxide. Carbohydr Polym 2013, 96, 233–239. [CrossRef]

- PN-ISO 2528:2000 - Wersja Polska PN-ISO 2528:2000; Sheet Materials—Determination of Water Vapour Transmission Rate—Gravimetric (Dish) Method. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2000.

- Kowalczyk, D.; Gustaw, W.; Świeca, M.; Baraniak, B. A Study on the Mechanical Properties of Pea Protein Isolate Films. J Food Process Preserv 2014, 38. [CrossRef]

| Lipid type |

Lipid content (%) |

pH | L* | a* | b* | WI | ΔE* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 6.76 ± 0.11 b | 41.39 ± 0.01 c | -0.21 ± 0.03 c | 2.13 ± 0.07 a | 41.35 ± 0.01 c | - |

| CW | 0.5 | 6.69 ± 0.02 ab | 42.05 ± 0.48 c | -076 ± 0.15 a | 5.21 ± 0.05 d | 41.81 ± 048 c | 3.22 ± 0.16 a |

| 1 | 6.66 ± 0.03 ab | 39.98 ± 1.71 b | -0.79 ± 0.03 a | 4.12 ± 037 c | 39.83 ± 1.70 b | 2.75 ± 1.08 a | |

| 1.5 | 6.65 ± 0.07 ab | 39.21 ± 0.30 ab | -0.88 ± 0.08a | 4.03 ± 0.33 c | 39.07 ± 0.39 ab | 2.96 ± 0.50 b | |

| 2 | 6.69 ± 0.08 ab | 39.51 ± 0.21 ab | -0.69 ± 0.02 ab | 4.94 ± 0.49 d | 39.45 ± 0.27 ab | 2.87 ± 0.49 a | |

| OA | 0.5 | 6.71 ± 0.06 ab | 39.94 ± 1.22 b | -0.46 ± 0.02 b | 2.69 ±0.46 b | 39.87 ± 1.21 b | 1.67 ± 1.12 a |

| 1 | 6.62 ± 0.02 a | 38.54 ± 0.86 a | -0.65 ± 0.17 ab | 2.68 ± 0.44 ab | 38.47 ± 0.84 a | 2.97 ± 0.79 b | |

| 1.5 | 6.58 ± 0.15 a | 39.62 ± 0.412 ab | -0.50 ± 0.05 b | 3.23 ± 0.18 b | 39.53 ± 0.16 ab | 2.11 ± 0.16 ab |

|

Lipid type |

Lipid content (%) |

MC (%) |

Sw (%) | So (%) | WVP (g mm m−2 day−1 kPa−1) | CA (O) |

| Control | 0 | 22.73 ± 1.20 b | 203.28 ± 19.35 a | 47.22 ± 2.53 a | 14.30 ± 0.68 f | 41.22 ± 6.66 a |

| CW | 0.5 | 22.80 ± 0.32 b | 222.32 ± 4.73 abc | 50.33 ± 3.68 ab | 8.96 ± 0.32 c | 74.71 ± 7.41 b |

| 1 | 19.99 ± 0.48 a | 238.36 ± 13.35 bcd | 51.73 ± 1.10 abc | 8.75 ± 0.51 c | 64.77 ± 4.01 b | |

| 1.5 | 20.62 ± 1.24 a | 223.33 ± 1.57 abc | 51.78 ± 3.43 abc | 6.89 ± 0.42 b | 97.60 ± 26.73 c | |

| 2 | 19.19 ± 0.73 a | 208.91 ± 15.40 ab | 57.40 ± 2.02 d | 5.36 ± 0.22 a | 100.13 ± 20.33 c | |

| OA | 0.5 | 19.86 ± 1.33 a | 247.20 ± 23.72 cd | 53.26 ± 0.67 bcd | 13.96 ± 1.02 ef | 36.25 ± 6.82 a |

| 1 | 20.06 ± 1.03 a | 245.17 ± 30.11 cd | 55.86 ± 4.77 cd | 12.90 ± 1.01 e | 28.95 ± 3.65 a | |

| 1.5 | 19.53 ± 0.95 a | 263.88 ± 31.14 d | 54.13 ± 4.24 bcd | 11.72 ± 0.68 d | 24.28 ± 2.08 a |

| Lipid type |

Lipid content (%) |

σmax (MPa) | εb (%) | EM (MPa) | HSS (N/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 3.56 ± 0.28 c | 81.23 ± 7.97 e | 99.11 ± 5.81 d | 0.069 ± 0.016 ab |

| CW | 0.5 | 2.70 ± 0.20 b | 50.38 ± 11.45 c | 71.14 ± 5.26 bc | 0.060 ± 0.030 a |

| 1 | 2.56 ± 0.25 ab | 55.44 ± 14.68 cd | 70.04 ± 3.60 b | 0.098 ± 0.015 cd | |

| 1.5 | 2.50 ± 0.27 ab | 39.88 ± 4.00 ab | 72.20 ± 9.32 bc | 0.063 ± 0.033 a | |

| 2 | 2.28 ± 0.13 a | 33.68 ± 5.01 a | 69.09 ± 6.12 b | 0.073 ± 0.006 abc | |

| OA | 0.5 | 3.61 ± 0.40 c | 64.19 ± 10.28 d | 99.63 ± 16.44 d | 0.105 ± 0.022 d |

| 1 | 2.57 ± 0.48 ab | 57.28 ± 7.60 cd | 81.47 ± 17.74 c | 0.091 ± 0.009 bcd | |

| 1.5 | 2.25 ± 0.36 a | 47.02 ± 5.44 bc | 56.76 ± 6.86 a | 0.088± 0.008 abcd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).