1. Introduction

This study seeks to examine how residential satisfaction mediates the relationship between social capital and attitudes toward vulnerable groups, while investigating the moderating effects of vulnerability status, such as educational and employment vulnerabilities. By integrating social capital and residential satisfaction, this study aims to fill gaps in the literature by providing insights into how these factors interact, particularly for vulnerable populations. This research also contributes to ongoing discussions in housing policy and social capital development by offering practical policy recommendations to enhance community cohesion and address the needs of marginalized groups.

Since the 1960s, South Korea has undergone rapid urbanization, industrialization, and modernization, leading to a swift concentration of population in major cities. This urban shift resulted in significant social issues such as housing shortages, rapid increases in housing prices, and the growth of the low-income population [

1]. In response, the South Korean government implemented large-scale housing supply policies, separating home sales and rentals and constructing the first public rental housing in 1962 to support low-income individuals unable to meet minimum housing standards [

2]. During this policy implementation, negative perceptions of rental housing began to escalate [

3]. Public rental housing came to be perceived negatively, associated with slum-like conditions, social exclusion, and stigma, leading to social discrimination and conflicts among low-income groups residing in these areas. Consequently, persistent issues arose, including opposition from nearby residents, depreciation of public rental housing values, discrimination against residents, deterioration of residential environments, and a decline in local image [

4]. Despite various government initiatives aimed at improving the perception of public rental housing and fostering social integration, these efforts have not fully resolved the underlying social issues. Discrimination remains prevalent, with approximately 40% of households in public rental housing reporting experiences of discrimination, particularly households with children and newlyweds [

5]. The persistence of discrimination is often attributed to the failure to foster meaningful social relationships, such as trust and confidence, beyond physical integration [

6].

Numerous studies [

7,

8,

9] have highlighted the importance of social capital in explaining social relations, including issues such as discrimination, egoism, and community conflicts. Discrimination is widely recognized as a significant factor that diminishes social capital, and both domestic and international research has shown that public rental housing residents experience social exclusion and discrimination, which exacerbates social issues [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. These findings underscore the importance of global policy efforts to address discrimination and promote social inclusion.

Existing literature indicates that marginalized groups with lower social capital tend to experience higher levels of discrimination [

16,

17], and individuals who perceive discrimination generally report lower levels of social capital compared to those who do not [

16]. Moreover, inequalities within communities can weaken their ability to connect with external sources of capital, further entrenching social disadvantages [

18]. Therefore, this study builds on previous research by examining how discrimination experiences impact social capital and housing stability among low-income residents of public rental housing.

While most studies have taken a variable-oriented approach, focusing on how independent variables like discrimination experiences affect dependent variables such as social capital, a person-oriented perspective highlights qualitative differences within the same group. This approach acknowledges that residents of public rental housing do not necessarily experience the same levels of discrimination or face identical risk factors. Individuals with higher discrimination experiences may share feelings of solidarity with those who have faced similar discrimination or belong to similar socioeconomic backgrounds. Rather than isolating themselves from interactions or disconnecting from their external environment, they may strive to assist neighbors and build communities [

19].

Considering these exceptional cases, it becomes clear that assuming those who experience discrimination more frequently have lower social capital may overlook the diverse characteristics of public rental housing residents. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to identify the types of discrimination experiences and social capital levels among public rental housing residents using latent class analysis (LCA). Additionally, this study seeks to understand the housing characteristics, perceptions of social mixing, resident activities, mental health, and other attributes associated with each type to derive policy implications for addressing discrimination and conflict.

The specific research questions for this study are as follows: Research Question 1: How do latent classes manifest when applying latent class analysis to classify discrimination experiences and levels of social capital among public rental housing residents? Research Question 2: What characteristics are associated with each latent class?

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Relationship Between Discrimination Experiences of Public Rental Housing Residents and Social Capital

Despite recent improvements in public perceptions of rental housing, discrimination remains prevalent, with severe cases reported even in the media, sparking scholarly interest. Interviews with residents of public rental housing reveal biases and stigmatization not only from homeowners but also internally among residents themselves [

9], highlighting the widespread nature of discrimination.

Discrimination experiences are closely linked to social capital. Studies have found that while human rights education alone did not reduce experiences of discrimination among children and adolescents, social capital had a significant mitigating effect [

19]. Specifically, the presence of trustworthy social networks, such as individuals available for emotional or practical support, significantly reduced both perpetration and victimization of discrimination. Similarly, research on the elderly population confirmed that higher levels of social capital correlate with fewer discrimination experiences [

20]. These findings suggest a generally negative relationship between discrimination experiences and social capital, where stronger social networks can reduce instances of discrimination.

Table 1 integrates various factors—housing characteristics, perceptions of social mixing, residential activities, and mental health—that collectively influence discrimination experiences and social capital. This holistic framework allows for a deeper examination of the complex dynamics within public rental housing communities and guides policy recommendations.

This study advances existing research by offering a more detailed exploration of how distinct components of social capital, such as trust and community support, directly affect discrimination experiences. By delving into these specific aspects, the study provides practical insights that can inform targeted social policies to reduce discrimination and strengthen community ties, contributing to more inclusive public housing environments.

2.2. Person-Centered Approach

This study employs a person-centered approach to classify the discrimination and social capital experiences of public rental housing residents. The person-centered approach, which distinguishes latent subgroups based on individual response patterns, is conducive to discerning qualitative differences within the same group [

21]. In understanding the relationship between discrimination experiences and social capital among public rental housing residents, this approach offers a differentiated perspective from previous studies discussing the relationship between discrimination experiences and social capital among public rental housing residents.

According to this approach, the degree of discrimination experiences can vary among individuals, and attitudes towards discrimination experiences can influence individual behaviors. For instance, experiencing discrimination does not necessarily lead to a decrease in social capital for all citizens, nor does a decrease in social capital always result in discrimination experiences. The existence of social capital reducing experiences of discrimination victimization, as indicated in previous research [

19], supports this notion. Conversely, a study targeting public rental housing residents [

4] found higher levels of discrimination experiences among groups with high social capital. Therefore, discrimination experiences and social capital do not necessarily diminish each other. Considering previous research, analyzing the relationship between discrimination experiences and social capital through a person-centered approach is necessary. Therefore, this study aims to conduct research that typifies the relationship between discrimination experiences and social capital.

This study's use of the person-centered approach highlights the diversity of resident experiences, addressing gaps in prior literature that often assume uniform effects across populations. By identifying subgroup-specific patterns, this research challenges traditional linear models and emphasizes the need for tailored interventions that account for the varied needs of residents. This perspective provides a valuable foundation for designing effective policies that address the distinct characteristics of different subgroups within the public rental housing population.

2.3. Factors Related to Discrimination Experiences and Social Capital of Public Rental Housing Residents

This study not only aims to typify the relationship between discrimination experiences and social capital but also to explore the key factors influencing this relationship. To this end, additional variables such as housing characteristics, perception of social mixing, residential activities, and mental health were examined.

Firstly, housing characteristics have been reported to be closely related to social capital. Various housing characteristics (e.g., location of public rental apartments, homeownership status, and duration of residence) emerged as significant influencing factors on social capital [

22]. Additionally, the residential environment positively influenced neighborly relationships among the elderly [

23]. Furthermore, housing characteristics were validated to be associated with discrimination experiences [

24]. Particularly, discrimination and neighbor conflicts among public rental housing residents influenced the selection of different types of housing. Thus, housing characteristics can be seen as related to discrimination experiences and social capital.

Next, perception of social mixing is significantly related to discrimination experiences and social capital. Social perceptions of public rental housing residents, especially prejudices and social stigmatization, lead to discrimination experiences and outcomes [

9]. Public rental housing residents, due to policy characteristics, consist of various types of individuals, contributing to social mixing. However, sudden social mixing may exacerbate discrimination experiences. Researchers on the relationship between social mixing and social capital argue that higher levels of social mixing correspond to higher levels of social capital [

25]. Appropriate policies promoting social mixing can positively contribute to social capital formation. Thus, a deep relationship between social mixing or perception of social mixing and discrimination experiences and social capital is evident.

Residential activities are also associated with discrimination experiences and social capital. Research suggests that community facility utilization among public rental housing residents enhances residential satisfaction, fosters social relationships among neighbors, and alleviates stress [

26]. Studies indicate that discrimination experiences indirectly influence social participation, such as residential activities [

27]. Therefore, residential activities are related to discrimination experiences and social capital.

Finally, mental health plays a significant role in shaping the relationship between discrimination experiences and social capital. Negative mental health outcomes, such as increased stress and depression, have been linked to experiences of discrimination, particularly among vulnerable groups like the elderly and children [

28,

29]. Conversely, strong social capital has been shown to have positive effects on mental health, acting as a buffer against the adverse impacts of discrimination [

30]. For public rental housing residents, factors such as health status, employment, and the residential environment can further influence mental health outcomes, highlighting the complex interplay between these variables [

31].

Table 1 presents a detailed synthesis of the key factors influencing both discrimination experiences and social capital. It highlights the interconnected nature of housing characteristics, social mixing perceptions, residential activities, and mental health. This integrated framework offers a holistic perspective for analyzing the dynamics of public rental housing communities, providing a valuable foundation for developing targeted policies that aim to enhance resident well-being and foster social cohesion.

Table 1.

Key Factors Influencing Discrimination Experiences and Social Capital.

Table 1.

Key Factors Influencing Discrimination Experiences and Social Capital.

| Factor |

Description |

Key

References |

Housing

Characteristics |

Location, ownership status, and duration of

residence impacting social capital and discrimination |

[22,24] |

| Perception of Social Mixing |

Community attitudes toward diverse residents

contributing to social capital and discrimination outcomes |

[9,25] |

Residential

Activities |

Participation in community activities enhancing

social relationships and mitigating discrimination stress |

[26,27] |

| Mental Health |

Psychological well-being affected by discrimination

experiences and social capital |

[28,29,30] |

By moving beyond traditional approaches that analyze variables in isolation, this study examines the interrelationships among key factors, providing a comprehensive framework that captures the complex social dynamics within public rental housing communities. This integrated analysis offers a nuanced understanding of how discrimination experiences and social capital interact, laying a robust foundation for evidence-based policymaking aimed at improving community relations and fostering social inclusion. In conclusion, this chapter deepens the engagement with existing literature by incorporating diverse influencing factors and employing a person-centered approach. This innovative perspective paves the way for the subsequent empirical analysis and sets a clear direction for future research efforts, ultimately aiming to enhance social cohesion and improve resident well-being.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

This study utilized data from the 4th year (2021) of the Seoul Public Rental Housing Residents Panel Survey, which provided a comprehensive and representative sample of public rental housing residents in Seoul. The survey included a broad range of items that captured detailed housing characteristics and the residential environment, making it highly relevant for this research. Additionally, the survey encompassed specific items related to discrimination experiences and social capital, which are central to the study’s focus.

The survey items used to assess discrimination experiences and social capital were selected based on a thorough review of existing literature and validated instruments from related studies. Items measuring discrimination experiences were designed to capture both external stigmatization from non-residents and internal biases within the community, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the issue. For social capital, survey items were chosen to reflect key components such as trust, social networks, and community participation. These items were adapted from established social capital assessment frameworks to maintain reliability and relevance.

The selection process was disciplined through expert consultations and pilot testing to refine the measures, ensuring they were contextually appropriate for public rental housing residents. This careful approach allowed for accurate data collection aligned with the study’s objectives, providing robust input for subsequent Latent Class Analysis (LCA). The final sample comprised 4,683 household members surveyed in 2021, offering robust data for reliable statistical analysis.

The sample’s primary strength lies in its comprehensive representation of public rental housing residents in Seoul, allowing for findings that are relevant to this specific population. The large sample size of 4,683 participants enhances the robustness of the analysis and supports the reliability of generalizing findings to similar urban public rental housing settings. Additionally, the inclusion of varied housing characteristics, discrimination experiences, and social capital components ensures a well-rounded understanding of resident experiences.

However, there are limitations to consider when generalizing the results. The data is specific to Seoul and may not fully represent public rental housing residents in other regions with different socioeconomic or cultural contexts. Moreover, while the sample provides rich cross-sectional data, it may not capture temporal changes or causal relationships. These factors should be acknowledged when interpreting the efficacy and broader applicability of the approaches used in this study.

3.2. Variables and Relevant Factors

3.2.1. Experiences of Discrimination and Social Capital

In this study, the variables used for latent class classification are the experiences of discrimination and social capital among public rental housing residents. Experiences of discrimination are measured dichotomously, with respondents indicating whether they have ever felt discriminated against as rental housing residents ("No" coded as 0, "Yes" coded as 1).

Social capital, as referenced in previous studies, encompasses trustworthiness, sense of belonging, and reciprocity. Accordingly, in this study, social capital is measured based on similar constructs. Trustworthiness is assessed by transforming responses to the question "Do you think you can trust the neighbors where you live?" into a dichotomous scale ("Not at all+Not really" coded as 0, "In general, yes.+it really is" coded as 1). Sense of belonging is evaluated through responses to the question "How do you get along with your neighbors where you currently live?" with options converted into a dichotomous scale ("You have no idea who lives next door+You know your neighbors, but you don't say hello" coded as 0, "Say hello to your neighbors or make small talk+I tend to know or communicate with my neighbors about family matters" coded as 1). Reciprocity is measured by two items: "Do you have neighbors you can turn to if you need urgent help?" and "Would you be willing to help someone in your neighborhood if they needed help in an emergency?" Responses are transformed into a dichotomous scale ("No" coded as 0, "Yes" coded as 1) and ("Not at all+Not really" coded as 0, "In general, yes.+it really is" coded as 1), respectively. Further details are provided in <

Table 2>.

3.2.2. Housing Characteristics

Housing characteristics encompass housing environment satisfaction, mixed-use complex residency, and severity of conflicts in mixed-use complexes. Housing environment satisfaction is comprised of nine items, including accessibility to public transportation, amenities, public facilities, cultural facilities, medical facilities, recreational spaces, welfare facilities, educational environment, and childcare environment, measured on a 4-point Likert scale. A higher score indicates greater housing environment satisfaction. Mixed-use complex residency is determined by responses to the question "Do you reside in a complex where rental housing and ownership housing are mixed?" coded as "Yes" or "No". The severity of conflicts in mixed-use complexes is gauged through six items related to parking-related conflicts, cleanliness issues, playgrounds, internal roads, community facilities, using a 4-point Likert scale. A higher score reflects higher conflict severity.

3.2.3. Perception of Social Mixing

Perception of social mixing comprises three items, wherein respondents provide responses on a 4-point Likert scale to two questions: "What are your thoughts on economic integration of different socioeconomic classes for social integration?" and "How do you feel about the establishment of facilities such as special schools, facilities for disabled individuals, and funeral homes in your local community?" Higher scores indicate a stronger perception of social mixing. Additionally, respondents are asked to express their preference regarding the integration of rental and ownership housing in one complex or separate complexes. Response options include: (1) Integration of rental and ownership housing in one complex, (2) Separation of rental and ownership housing into different complexes, and (3) Uncertain.

3.2.4. Resident Activities

Resident activities include participation in community organization meetings, types of community organizations, and usage of community facilities. Participation in community organization meetings is determined by responses to the question "Have you participated in any community organization or meeting within the past year?" coded as "Yes" or "No". Types of community organizations include tenant representative meetings, women's groups, senior citizen groups, various clubs, resident communities (online sites), and other categories. The usage of community facilities is assessed based on eleven items, indicating frequency of use on a dichotomous scale ("Do not use" coded as 0, "Occasionally use+Frequently use" coded as 1).

3.2.5. Mental Health

Mental health comprises everyday life stress and self-esteem. Everyday life stress is measured on a 4-point Likert scale in response to the question "How much stress do you experience in your daily life?" ranging from "None" (1) to "Very much" (4). Self-esteem is assessed through eight items, scored on a 4-point Likert scale, reflecting positive self-regard. The reliability of the self-esteem scale is indicated by Cronbach’s alpha (.751). A higher score indicates higher self-esteem. All four relevant factors and their respective items used in this study are detailed in <

Table 3>.

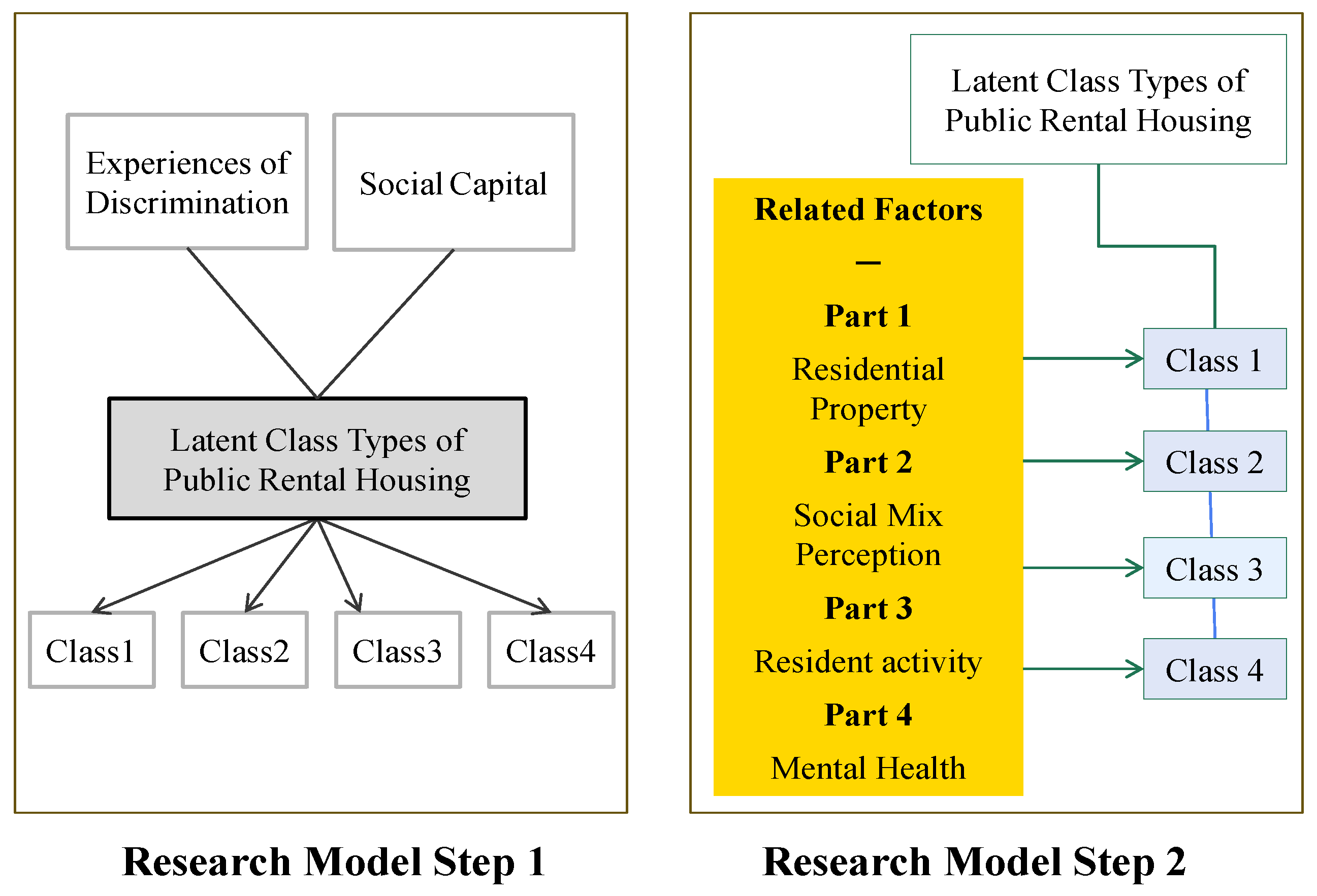

3.3. Research Model

The aim of this study is to typify discrimination experiences and social capital among public rental housing residents and analyze differences in related factors by type. To achieve this, the research model depicted in <

Figure 1> has been established. Latent Class Analysis (LCA) was employed to identify unobservable subgroups within the public rental housing residents based on their experiences of discrimination and levels of social capital. This method allowed for the classification of individuals into distinct types, facilitating a more nuanced examination of how these subgroups experience differences in related factors.

3.4. Latent Class Analysis Method

Latent Class Analysis (LCA) is a statistical technique used to identify hidden subgroups within a population based on observed variables. This method was selected for its ability to model complex patterns and uncover heterogeneity within the sample without relying solely on predefined categories. By using LCA, this study classified residents into distinct subgroups based on their reported discrimination experiences and levels of social capital, providing deeper insight into the characteristics of each group and their differences in related factors.

The justification for employing LCA lies in its flexibility and capability to handle multiple indicators to define latent classes. This approach aligns with the study’s goal of typifying discrimination experiences and social capital types among public rental housing residents, allowing for a detailed analysis that informs targeted policy recommendations for each subgroup.

3.5. Data Analysis Method

For data analysis, this study utilized SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 7.4 to perform Latent Class Analysis (LCA), chi-square analysis, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The primary goal was to explore the typologies of public rental housing residents based on their experiences with discrimination and social capital.

Latent Class Analysis (LCA) was employed to identify unobserved subgroups, or latent classes, that share similar patterns of responses regarding discrimination experiences and social capital. LCA is conceptually similar to cluster analysis but offers greater flexibility in assumptions about the data, such as the absence of linearity, normality, and homogeneity of variance. This method divides individuals into classes based on shared characteristics, allowing for an analysis of differences across these groups.

To determine the optimal number of latent classes, multiple fit indices were used. First, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and Adjusted BIC were used to assess model fit. These information-based indices evaluate the balance between model complexity and goodness of fit, with smaller values indicating a better fit. Additionally, the Entropy Index was employed to measure the classification accuracy of the latent class model. The entropy value ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a higher accuracy in classifying individuals. A value of 0.8 or above is typically considered indicative of well-classified latent classes. Finally, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (LMRT) was conducted to compare the fit between models with different numbers of latent classes. If the LMRT yielded significance at p < .05, it indicated that the k-class model was a better fit than the k-1 model, thus selecting the appropriate number of classes.

The LCA was conducted using Mplus 7.4, with the aforementioned statistical indices guiding the final determination of the latent classes based on residents' discrimination experiences and levels of social capital.

Following the identification of latent classes, chi-square analysis and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted using SPSS 26.0 to examine differences across the latent groups. The chi-square analysis was used to assess associations between categorical variables, such as housing characteristics and perceptions of social integration. Meanwhile, ANOVA was applied to evaluate mean differences in continuous variables, including resident activities, mental health outcomes (e.g., daily life stress, self-esteem), and social mixing perceptions across the latent groups. These statistical methods allowed for a comprehensive understanding of how these latent groups differed in terms of their housing environment, social integration, and well-being.

By employing these analytic techniques, the study provided a detailed examination of how residents of public rental housing in South Korea can be grouped based on their experiences with discrimination and social capital. Furthermore, the analysis revealed how these latent typologies related to housing characteristics, mental health, and perceptions of social cohesion, offering valuable insights into the social dynamics within public rental housing communities.

4. Results

4.1. Latent Class Classification of Discrimination Experience and Social Capital Among Public Rental Housing Residents

To address Research Question 1, we systematically identified latent classes among public rental housing residents by increasing the number of classes from 2 to 5 and examining model fit indices. Initially, as the number of classes increased, AIC, BIC, and Adjusted BIC values consistently decreased. However, from 5 classes onwards, these values began to increase. The entropy value, reflecting the quality of classification, remained at a moderate level of adequacy, around 0.6, up to 4 classes but decreased to 0.571 for 5 classes. It is considered feasible to compare latent classes when the sample size within each class exceeds 1% of the total sample [

36]. LMRT values were statistically significant up to 4 classes but not significant for 5 classes. Additionally, examination revealed that for models with 2, 3, and 4 latent classes, there were no latent classes comprising less than 1% of the total sample. Considering these statistical criteria, the 4-class model was deemed most appropriate for revealing discrimination experiences and social capital among public rental housing residents. The details of the model fit verification are provided in

Table 4.

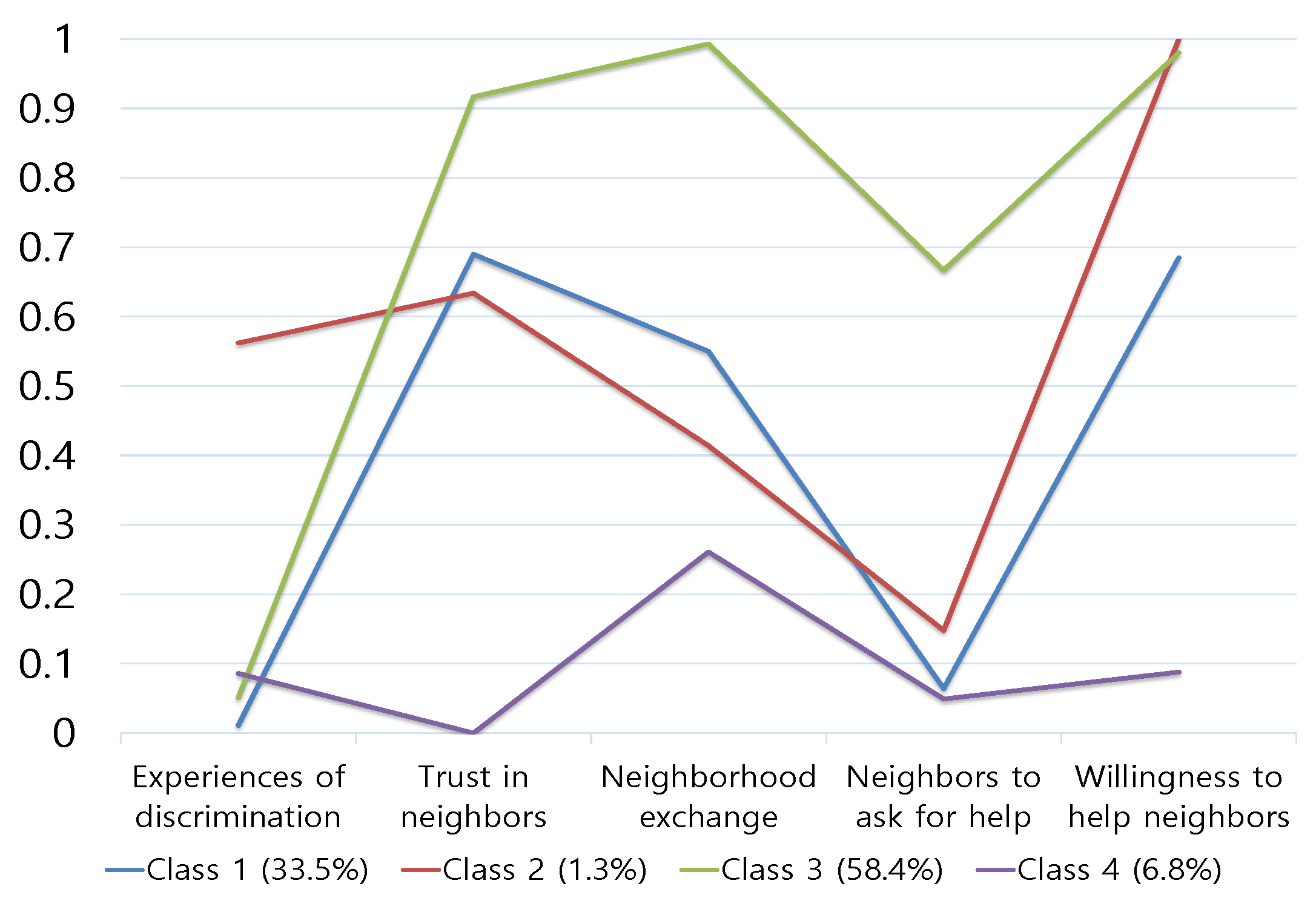

Latent Class 1 consisted of 1,567 individuals (33.5% of the total sample), characterized by minimal discrimination experiences (1.1%). However, they exhibited relatively high levels of neighbor trust (69.0%) and neighbor interaction (55.0%). Although they had few neighbors to turn to for help in times of difficulty (6.4%), their willingness to assist needy neighbors (68.5%) was pronounced. Considering their high neighbor trust and involvement indicative of belongingness, as well as their willingness to assist neighbors in need, Latent Class 1 was named the `Neighborly Support Seekers Group’.

Latent Class 2 comprised 63 individuals (1.3% of the total sample), exhibiting the highest level of discrimination experiences among the four groups (56.2%). Similar to Latent Class 1, they demonstrated high levels of neighbor trust (69.0%) and interaction (41.4%). While they had fewer neighbors to seek help from in times of need (14.8%), their willingness to assist struggling neighbors was 100%. Therefore, Latent Class 2 was labeled the `Group Accepting Losses’.

Latent Class 3 included 2,735 individuals (58.4% of the total sample) with minimal discrimination experiences (5.1%). They displayed the highest levels of neighbor trust (91.7%), interaction (99.3%), willingness to seek help from neighbors (66.7%), and willingness to assist neighbors (98.0%) among the four groups. Consequently, Latent Class 3 was designated the `Group with High Social Capital’.

Latent Class 4 comprised 318 individuals (6.8% of the total sample) with very few discrimination experiences, akin to Latent Classes 1 and 3 (8.6%). However, their response rates for neighbor trust (0%), interaction (26.1%), seeking help from neighbors (4.9%), and willingness to assist neighbors (8.8%) were the lowest among the four groups. Hence, Latent Class 4 was named the `Group Indifferent to Neighbors'. The characteristics of each latent class are summarized in

Table 5, and the response patterns by latent class types are illustrated in

Figure 2.

4.2. Factors Associated with Latent Class Types

Research Question 2 investigates the unique characteristics associated with each identified latent class. The following sections provide detailed analyses of these characteristics.

4.2.1. Association Between Latent Class Types and Housing Characteristics

An examination of housing characteristics among public rental housing residents by latent class types is presented in

Table 6. Significantly, differences were observed among groups in terms of housing environment satisfaction, residency in mixed-use complexes, and levels of conflict within such complexes. Specifically, housing environment satisfaction, rated on a 4-point scale, was significantly higher for the `Group Accepting Losses’ (3.21 points) and the `Group with High Social Capital’ (3.14 points) compared to other types. Satisfaction with access to amenities, public facilities, and medical services for these groups ranged around the low 3-point mark, whereas the `Group Indifferent to Neighbors’ scored notably lower, in the low 2-point range. Furthermore, the proportion of residents in mixed-use complexes was highest for the `Group Accepting Losses’ (50.8%).

An examination of conflict levels among residents in these complexes revealed significant differences. For instance, conflict related to parking was significantly higher for the `Group Accepting Losses’ (1.66 points) and the `Group with High Social Capital’ (1.42 points) compared to the `Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships’ (1.30 points). Similarly, issues regarding cleanliness were significantly higher for the `Group Accepting Losses’ (1.72 points) and the `Group with High Social Capital’ (1.40 points) compared to the ‘Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships’ (1.32 points) and the `Group Indifferent to Neighbors’ (1.34 points). Additionally, conflict over community facilities was higher for the `Group with High Social Capital’ (1.44 points) compared to the `Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships’ (1.31 points). The housing characteristics by latent class type are summarized in

Table 6.

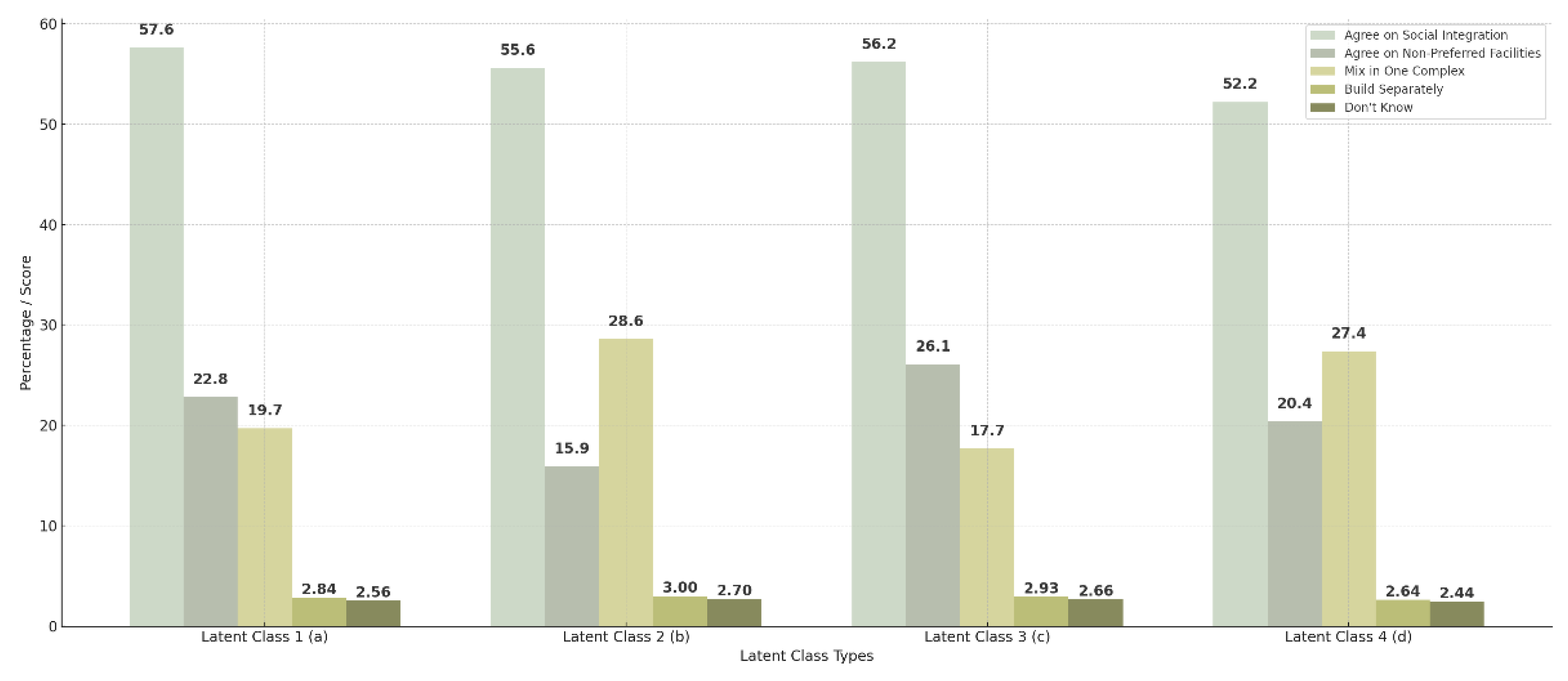

4.2.2. Association Between Latent Class Types and Social Mixing Perception

An examination of social mixing perception among public rental housing residents by latent class types, as shown in

Table 7 and

Figure 3, yielded the following results. First, regarding the degree of agreement (on a 4-point scale) with the idea of different socioeconomic strata living together for social integration, scores were highest for the `Group Accepting Losses’ (mean 3.00), followed by the `Group with High Social Capital (mean 2.93), the `Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships’ (mean 2.84), and the `Group Indifferent to Neighbors’ (mean 2.64). Similarly, agreement regarding the siting of undesirable facilities within the local community was highest for the `Group Accepting Losses’ (mean 2.70), followed by the `Group with High Social Capital’ (mean 2.66), the `Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships’ (mean 2.56), and the `Group Indifferent to Neighbors’ (mean 2.44). Interestingly, there was a consensus across all latent class types that mixing rental and ownership housing within the same complex is preferable.

4.2.3. Association Between Latent Class Types and Resident Activity

An examination of resident activities among public rental housing residents by latent class types, as shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9, revealed the following findings. Overall, participation rates in residents' organizations or groups were very low, with the `Group with High Social Capital’ (2.0%) showing slightly higher participation compared to other groups. Regarding the types of residents' organization participation, senior citizen groups (26.6%), women's groups (23.4%), resident communities (17.2%), and tenant representative meetings (12.5%) were most common. Usage of community facilities varied, with the `Group Accepting Losses’ and the `Group with High Social Capital’ reporting higher rates of occasional or frequent use compared to other groups.

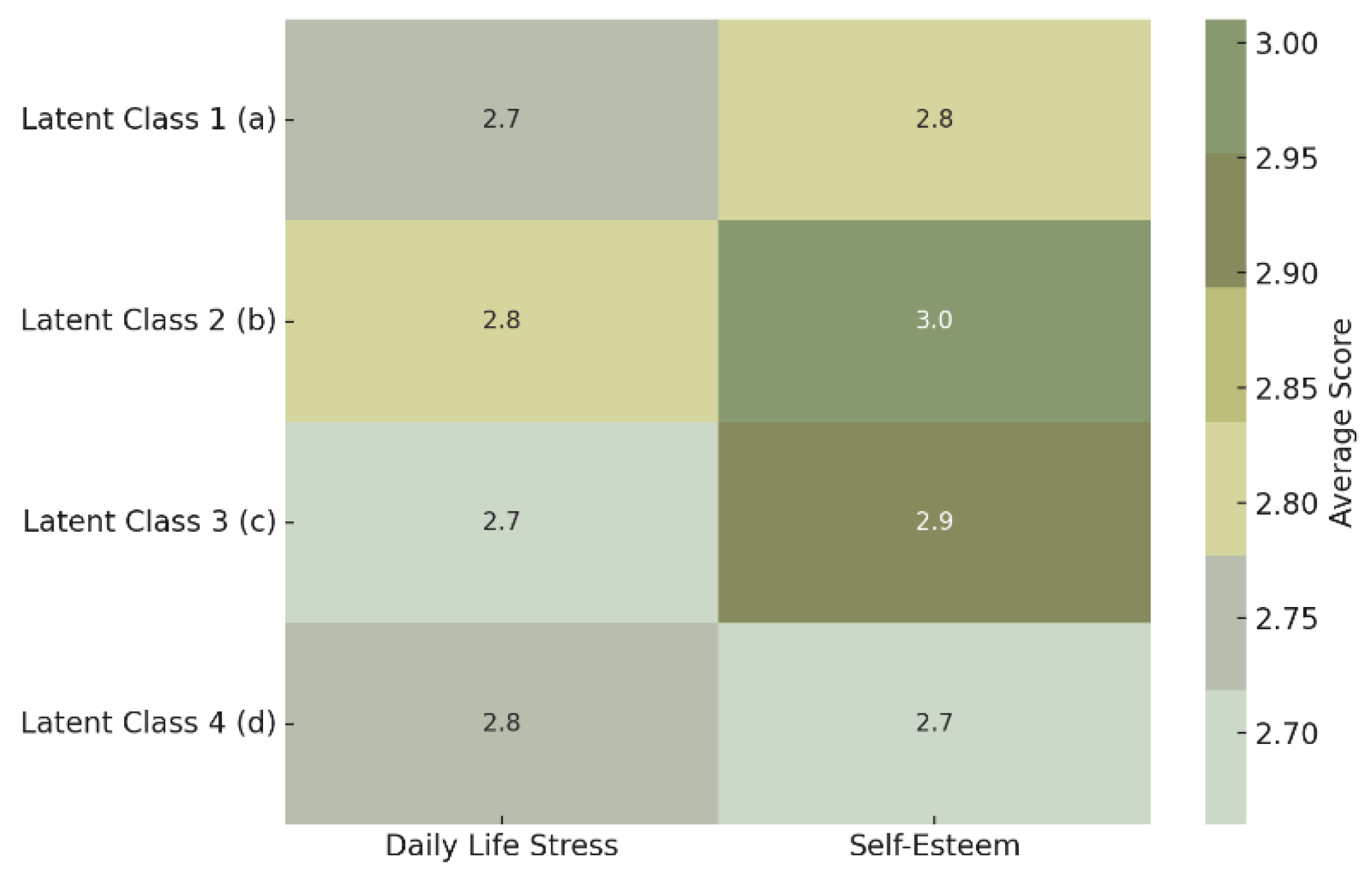

4.2.4. Association Between Latent Class Types and Mental Health

An examination of mental health among public rental housing residents by latent class types is presented in

Table 10. Significant differences were observed among groups in daily life stress and self-esteem. The `Group with High Social Capital’ reported lower levels of daily life stress (mean 2.66) compared to other groups. Additionally, both the `Group with High Social Capita’l (mean 2.94) and the `Group Accepting Losses’ (mean 3.01) reported higher levels of self-esteem compared to other groups. Conversely, the `Group Indifferent to Neighbors’ reported the lowest self-esteem (mean 2.71) among all latent class types. The mental health characteristics by latent class type are summarized in

Table 10, and the heatmap visualization of these characteristics is shown in

Figure 4.

5. Discussion

This study highlights the crucial role that social capital and residential satisfaction play in shaping attitudes toward vulnerable populations. The findings support existing theories that emphasize the interaction between social networks and residential environments in influencing social behaviors. While prior research has established the importance of social capital in fostering inclusive attitudes, this study extends that understanding by demonstrating the mediating effect of residential satisfaction. Individuals with higher residential satisfaction are more likely to develop positive attitudes toward disadvantaged groups, indicating that improvements in housing conditions can have far-reaching social implications.

Unlike previous studies that examined social capital and residential satisfaction independently, this research integrates these factors to analyze their combined influence on social attitudes. The results show that the positive effects of social capital are amplified by residential satisfaction, particularly among educationally and employment-vulnerable groups. This supports the notion that housing environments serve not only as physical spaces but also as social contexts that shape interpersonal interactions and attitudes. Therefore, improving residential environments through increased safety, accessibility, and social cohesion can contribute significantly to fostering more inclusive communities [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Additionally, this study advances the literature by addressing the differential effects of social capital based on vulnerability status. It reveals that educational and employment vulnerability moderate the relationship between residential satisfaction and attitudes, with more pronounced positive effects observed among vulnerable groups. This suggests that these populations are especially sensitive to improvements in residential satisfaction, which can act as a buffer against the social exclusion they often experience. These findings align with existing research, which underscores the compounded challenges faced by vulnerable populations, and highlights the critical role of housing in mitigating these disadvantages.

The policy implications of these findings are significant. Urban planners and policymakers should prioritize strategies that enhance social capital within communities. Initiatives that create communal spaces, support local organizations, and promote civic participation can foster trust, cooperation, and ultimately, more inclusive attitudes toward vulnerable populations. Additionally, housing policies aimed at improving living conditions for vulnerable groups particularly those who are educationally or employment-vulnerable will likely have a more substantial impact on fostering positive social attitudes. Enhancing neighborhood safety, transportation accessibility, and green spaces can improve residential satisfaction and, in turn, promote social cohesion.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the complex interaction between social capital, residential satisfaction, and attitudes toward vulnerable populations. It demonstrates that social capital significantly influences residential satisfaction, which in turn shapes attitudes toward disadvantaged groups. Moreover, the impact of residential satisfaction is stronger among educationally and employment-vulnerable individuals, emphasizing the need for targeted housing interventions for these groups. These findings offer critical guidance for urban policy and housing strategies aimed at promoting social inclusion and cohesion.

6. Conclusions

We categorized the response patterns between discrimination experiences and social capital among residents of public rental housing into several group types through latent class analysis and identified the housing characteristics, social mixing perception, resident activities, and mental health of each group. The key findings and discussions are as follows.

First, the classification of discrimination experiences and social capital response patterns resulted in four distinct groups. The characteristics of each group are as follows. Firstly, the `Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships’ (33.5% of the total sample) showed minimal discrimination experiences while exhibiting relatively high levels of neighbor trust and interaction. Moreover, although they had few neighbors to seek help from in times of difficulty, they expressed a willingness to help their neighbors in need. In contrast, the `Group Accepting Losses’ (1.3% of the total sample), which had the lowest proportion in this study, experienced the most discrimination while residing in rental housing. Yet, like the `Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships’, they also demonstrated high levels of neighbor trust and interaction. Additionally, while they had almost no neighbors to seek help from in times of difficulty, they expressed a 100% willingness to help their struggling neighbors. Conversely, the `Group with High Social Capital’ (58.4% of the total sample) experienced minimal discrimination while exhibiting the highest levels of neighbor trust, interaction, willingness to seek help from neighbors, and willingness to help neighbors. Lastly, the `Group Indifferent to Neighbors’ (6.8% of the total sample) had somewhat contrasting characteristics compared to the other three groups. That is, although they experienced minimal discrimination like the `Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships’ and `Group with High Social Capital’, they completely distrusted their neighbors, had minimal neighbor interaction or help-seeking behavior, and demonstrated the lowest willingness to help neighbors in need.

Second, cross-analysis and variance analysis were conducted to confirm the housing characteristics, social mixing perception, resident activities, and mental health of the identified latent strata. Firstly, the 'Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships' group had relatively high housing satisfaction scores on a 4-point scale. The degree of conflict experienced when residing in mixed-use complexes was also relatively low; however, like other groups, their participation rates in resident organizations or gatherings were low. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown a positive influence of the living environment on neighborly relations. Interestingly, the 'Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships' group had higher levels of daily life stress and lower levels of self-esteem compared to other groups. For instance, according to the latent class analysis results, the 'Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships' had almost no neighbors to seek help from, akin to the 'Group Indifferent to Neighbors' group, suggesting that due to this lack of social support network, the mental health of individuals in the 'Group Seeking Friendly Neighbor Relationships' group might have been compromised. Previous research has shown that low social support among middle-aged adults increases depression, and existing research results support the idea that the social capital of local residents affects mental health.

Third, the 'Group Accepting Losses' group had a higher proportion of residents living in mixed-use complexes compared to other groups and experienced higher levels of conflict related to parking and cleanliness issues, such as waste separation. Nevertheless, despite these challenges, they showed the highest agreement with the idea of economic integration for social integration, indicating a relatively high level of social mixing perception. Generally, discrimination experiences are widely recognized as a significant risk factor for worsening social capital. Typically, experiencing discrimination from one's surroundings can lead to distancing from neighbors or avoidance of residents in higher income brackets. However, the altruistic nature of many public rental housing residents might mitigate these effects. For example, in this study, the 'Group Accepting Losses' group showed a higher agreement rate for the placement of undesirable facilities within the community, such as special schools, facilities for disabled individuals, or funeral parlors, compared to other groups.

Fourth, the 'Group with High Social Capital' group had the highest housing satisfaction scores, while the 'Group Indifferent to Neighbors' group had the lowest. The agreement level regarding economic integration for social integration was also highest among the 'Group with High Social Capital' and lowest among the 'Group Indifferent to Neighbors'. Additionally, in terms of mental health, daily life stress was lowest among the 'Group with High Social Capital' and highest among the 'Group Indifferent to Neighbors'. Conversely, self-esteem was highest among the 'Group with High Social Capital' and lowest among the 'Group Indifferent to Neighbors'. These results indicate that a significant portion of public rental housing residents with good neighborly relations are satisfied with their living environment, have a high social mixing perception, and enjoy good mental health. In contrast, those who are indifferent to their neighbors are likely dissatisfied with their living environment, have a low social mixing perception, and experience poor mental health. Therefore, more social attention is needed for public rental housing residents who wish for good neighborly relations.

To effectively address discrimination and conflict issues among public rental housing residents, it is essential to develop step-by-step policies that focus on both physical and social integration. Policy Recommendations should prioritize creating diverse, inclusive communities by establishing clear guidelines at every stage from architectural planning to operational management. This includes ensuring mixed-use developments that encourage interaction across different social groups, implementing minimum housing standards to avoid segregation, and reducing visible distinctions between public rental housing and privately-owned housing. A holistic approach that integrates social, economic, and cultural aspects of community life is necessary to combat discrimination. By improving the physical environment and fostering social cohesion through community-building activities, discrimination and social conflict can be significantly mitigated.

Institutional standards must also reflect the social dynamics within public housing, supporting efforts to create inclusive, harmonious neighborhoods. Programs aimed at fostering social mixing such as community events, educational programs, and shared spaces will help reduce social isolation and build trust among residents. Enhancing access to resources and creating opportunities for interaction across different resident groups will further contribute to reducing prejudice and promoting social cohesion.

In summary, this study provides foundational data that can guide future housing policies by highlighting the importance of social capital in mitigating the effects of discrimination. While previous research has often emphasized the negative impact of discrimination on neighborly relations, this study offers a nuanced perspective by revealing the existence of a group of residents who maintain high levels of trust and interaction despite facing substantial discrimination. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions that are sensitive to the different profiles of public rental housing residents, offering tailored solutions for each group's unique needs.

Limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Firstly, the data were collected solely from residents in Seoul, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the entire country. Additionally, some survey items, such as the discrimination experience variable, were measured with a single-item indicator, which may not capture the full complexity of these experiences. This limitation may introduce biases in interpreting the strength and depth of discrimination-related effects on social capital.

Future Research Directions should address these limitations by conducting nationwide surveys that capture a broader demographic range. Using multi-item measures to assess discrimination experiences more comprehensively will allow for a deeper understanding of how social capital dynamics vary across different regions and resident profiles. Furthermore, exploring additional variables such as cultural diversity, age, and health status could provide further insights into the multifaceted nature of social capital and discrimination in public rental housing. Longitudinal studies could also help track changes over time, offering a clearer picture of how housing policies influence social integration and resident well-being in the long term.

In conclusion, this study contributes valuable insights into the role of social capital and residential satisfaction in shaping attitudes toward vulnerable populations in public rental housing. The findings suggest that tailored housing interventions focusing on physical and social integration can significantly reduce discrimination and improve social cohesion. These conclusions offer practical guidance for urban planners and policymakers aiming to foster inclusive communities and create more equitable housing environments.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, S.J., S.K.; methodology, S.J. and S.K.; validation, S.J. and S.K.; formal analysis, S.J. and S.K.; investigation, S.J. and S.K.; data curation, S.J. and S.K.; original draft preparation, S.J. and S.K.; review and editing, S.J. and S.K.; supervision, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Urban Regeneration Professional Human Resources Training Project (task number R2018045) implemented by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport.

Data Availability Statement

Data are publicly and freely available from the Korea Housing Survey released by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (

https://mdis.kostat.go.kr).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kang, E.T.; Ma, K.R. A Study on the Economic Effects of Migration to the Capital Region. Nat. J. Territorial Plann. Korean Society of Territorial and Urban Planning, 2012. 2012, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, C.H.; Kim, J.Y. A Study on the Residential Satisfaction of Residents in Publicly Sold and Publicly Rented Houses. J. Hous. Environ. Korean Society of Housing Studies, 2012. 2012, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.H.; Roh, S.H. Survey Study on Social Exclusion of Multi-Family Rental Housing and Permanent Rental Housing Residents. J. Korean Hous. Assoc. Korean Housing Association, 2011. 2011, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.E.; Kang, S.J.; Kang, M.S.; Seo, W.S. Relationship between Experience of Discrimination and Social Capital Formation from Public Housing Residents. Dep. Urban Plann. Real Estate 2018, 36, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Korea Housing Survey; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong City, Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, H.S. Social Integration Measures for Public Rental Housing Complexes. Natl. Land Policy Brief Korea Land Institute, 2012. 2012, 371. [Google Scholar]

- Murchie, J.; Pang, J. Rental housing discrimination across protected classes: Evidence from a randomized experiment. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018, 73, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.E.; Kang, S.J.; Kang, M.S.; Seo, W.S. Relationship between Experience of Discrimination and Social Capital Formation from Public Housing Residents. Korea Real Estate Soc. 2018, 36, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Park, J. A Study on Reduction of the Stigma Against Residents in Public Rental Housing Focusing on Social-Mix of Residents. Korea Spatial Plann. Rev. 2023, 116, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K.; Yang, K.M. The Study on the factors which affect the ego-resiliency of students from multicultural families. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2012, 19, 147–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.M.; Won, S.J.; Choi, S.H. Experiences of discrimination and psychological distress of children from multicultural families: Examining the mediating effect of social support. Korean J. Social Welfare Stud. 2011, 42, 117–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jeong, G. The Influence of Discrimination and Coping Strategies on Life Satisfaction of Multicultural Adolescents: The Moderating Effect of Coping Strategies. Health Soc. Welfare Rev. 2016, 36, 336–362. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, L.M.; Romero, A.J. Coping with discrimination among Mexican descent adolescents. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2008, 30, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, R.M.; Copeland Linder, N.; Martin, P.P.; Lewis, R.H. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2006, 16, 187–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.A.; Eccles, J.S.; Sameroff, A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents' school and socioemotional adjustment. J. Pers. 2003, 71, 1197–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Yang, T. The pathways from perceived discrimination to self-rated health: An investigation of the roles of distrust, social capital, and health behaviors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 104, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolcock, M. Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.; Maurer, K. Unravelling social capital: Disentangling a concept for social work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2012, 42, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, E.H. Human Rights Education, Social Capital and Youth Experiences of Discrimination. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 21, 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Moon, K.J. The Influence of Social Capital on Ageism: Focusing on The Mediating Effect of Sense of Community. Soc. Econ. Policy Stud. 2017, 7, 135–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, S.T.; Rhoades, B.L. Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prev. Sci. 2013, 14, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.K. The Study of Residential Influential Factors on Local Community Social Capital. Korean Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 27, 237–267. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.J.; Kim, E.P.; Nam, S.I. A Study on the Residential Environment Satisfaction Types and Neighborhood Relationships of Older People. Korean J. Gerontol. Soc. Welfare 2021, 76, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.E. A Study on the Future Housing Choice of Residents of Public Rental Housing in Seoul. J. Real Estate Anal. 2023, 9, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.N.; Kim, J.H. The Empirical Relationship between the Neighborhood-level Social Mix and the Residents’ Social Capital and Experience of Receiving Help. Korea Spatial Plann. Rev. 2013, 76, 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.Y.; Kim, J.H. An Analysis of the Frequency of Community Facility Usage on Residential Satisfaction in Public Rental Housing. SH Urban Res. Insight 2020, 10, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.D.; Son, E.S. The Influences of Self-Perception and Experiences of Age Discrimination upon the Social Participation Among the Elderly: A Mediating Effect of Self-Efficacy. Korean J. Gerontol. Soc. Welfare 2010, 49, 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Won, Y.H. Experiences of Elderly Discriminations and Psychological Well-being of the Elderly. Soc. Welfare Policy 2005, 21, 319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; Hong, C.H. The Effect of Discrimination experience and Language problems on Psychosocial adjustment in Children with Multi-cultural family: The Moderating Effect of Ego-resilience and Family strengths. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2017, 24, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Yeom, D.M. Relationship between Mental Health and Social Capital of Local Residents: Focusing on Gyungsangnam-Do. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2014, 14, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, M.J.; Choi, M.S.; Lim, H.Y. The Effects of the Discrimination Experience in Housing Lease and Residential Satisfaction on Depression among Single Parents. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2022, 22, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Jun, H.J. Mental Health among Public and Private Housing Residents. Korean J. Public Admin. 2018, 56, 313–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T. Longitudinal Study on Latent Class Analysis and Cluster Analysis: Comparing Growth Mixture Models. Korean Educ. Eval. Assoc. 2010, 23, 641–664. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, G.Y.; Park, T.Y. A Longitudinal Study on the Changes in the Typology of Social Relationships among Retirees by Using Latent Class Analysis. Korean J. Family Welfare 2013, 18, 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, U.K.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, H.J. Dual Trajectory Modeling Approach to Analyzing Latent Classes in Youth Employees` Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention Trajectories. Korean J. Survey Res. 2011, 12, 113–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, K.G.; White, H.R.; Chung, I.J.; Hawkins, J.D.; Catalano, R.F. Early adult outcomes of adolescent binge drinking: Person-and variable-centered analyses of binge drinking trajectories. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.K.; Lee, Y.H. Depression, Powerlessness, Social Support, and Socioeconomic Status in Middle Aged Community Residents. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 19, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).