1. Introduction

The hypothesis of dark matter is a

way to explain why among other galaxies seem not to obey Newton’s law of

gravity. There exist several approaches to account for dark matter or for the

additional gravity it yields. Like Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) [1–3] , Bekenstein’s

TensorVectorScalar gravity (TeVeS) [4] or Covariant Emergent Gravity

(CEG) [5,6] , which

assume dark matter does not really exist. But that leaves the statistical

distribution of ‘cold’ and ‘hot’ spots in the background radiation unresolved,

that would still need the existence of (much) dark matter vs. baryonic matter

to be understandable in terms of Big Bang nucleosynthesis, as well as matters

like gravitational lensing.

In this paper a hybrid alternative

will be presented, which is based upon the existence of dark matter and follows

from Hawking’s Cosmology [7,8]. It solves the problem that Lelli and Mistele [9] showed, that the common way to

project dark matter halos around galaxies cannot be valid, since the

alternative naturally assumes dark matter is distributed like the visible

matter in a galaxy. The hypothesis gives a natural explanation for both dark matter

and the behaviour of gravity and why it shows behaviour as described by MOND

and TeVeS theory. The term naturalness is extensively

discussed by Hossenfelder [10] (p. 57). In short it means that a theory is without fine-tuned

constants. Since General Relativity (GR) in galaxies would need the said halos

too so as to properly include the effect of dark matter, it must be modified

with some additional terms to make correct solutions possible without these

halos. TeVeS [4] meets this need.

In this paper the Spitzer Space

Telescope satellite data of 175 galaxies, as processed and reported by Lelli et

al. [11] and Starkman

et al [12] are used to

test several predictions that follow from this theory. The mass-to-light ratio

has been used as the only fitting parameter to fit the baryonic rotation

velocity, and hence the baryonic gravitational acceleration in each galaxy to

the observed values near the core of the galaxies. After that, the hypothesis

in hand is used to predict the additional gravitational acceleration at all

radii without any further fitting and to compare the predictions with the

observed values.

After a brief introduction of Big

Bang theory in chapter 2.1 and Hawking’s cosmology in chapter 2.2 and some

other indispensable literature about quantum systems in chapter 2.3, MOND and TeVeS

will be discussed in chapter 3. Then, in chapter 4.1, firstly, an

interpretation of the MOND like behaviour of dark matter as a sum of two fields

will be proposed. Secondly, the natural basis for this will be explored in

chapter 4.2 and will stepwise be derived in a logical manner from Hawking’s

cosmology in chapter 4.3. In chapter 5, based upon chapter 6, the hypothesis

for dark matter will be elaborated and its consequences and behaviour will be

explored. In chapter 6 six testable predictions are proposed, five of which are

proved, and an improved alternative to MOND for the prediction of rotation

velocities will be presented. In chapter 7 TeVeS will be

elaborated and used for a relativistic formulation of the hypothesis. In

chapter 8 the conclusions and suggestions for further work are presented.

2. Hawking´s Cosmology and Superposition State of Universe

2.1. Big Bang Theory

The line of thought of the

universe as a quantum system is an elaboration of The Grand Design,

[8]

with additions from Van den

Heuvel

[13]

and

references to Hartle & Hawking

[7]

.

The universe, according to the Big

Bang theory, comes from an infinitesimal small point in which only elementary

particles existed in the form of a plasma, with an extremely high temperature

[13]

(pp. 127-136).

The originally extremely high

temperature is still visible and measurable in the so-called background

radiation. Its properties are direct evidence that the universe originated from

a hot Big Bang stage. The Big Bang theory is also a logical extrapolation of

the expansion of the universe that we observe, among other things due to the

redshift of the spectrum of the radiation of stars, but also of the

history/evolution of stars and galaxies as visible through our telescopes. In

addition, the non-uniform distribution of stellar objects as quasars over the

different redshifts proves the universe is not static.

Moreover, Big Bang theory can

quantitatively explain many phenomena, such as the distribution over the

various elements of the mass in the universe, the cosmic composition, based on

nuclear physics. The fact that it is dark at night also proves that the universe

cannot be infinitely large and infinitely old, because then the entire sky

would be filled with light from stars. So, our universe indeed has a beginning.

Moreover, the Big Bang theory forms a well-cohesive whole with astronomy and

the rest of physics.

2.2. Hawking´s Cosmology

Somewhere at the beginning, our

universe has been in a quantum state, because that's where one ends upon

extrapolating the expansion of the universe back to the very smallest starting

point,

[7,8]

have

derived solutions to the wave function of the universe as proposed by Everett

[14]

and further elaborated by

DeWitt

[15]

. As

derived and explained by Hartle & Hawking

[7]

these solutions must satisfy the Wheeler-DeWitt equation.

Hartle & Hawking

[7]

show the Wheeler-DeWitt

equation has the following form:

Where is the wave function of the

universe and where Ĥ(x) is called

the Hamiltonian constraint,

[7]

. The Hamiltonian, in this case derived from General Relativity

[7]

, describes the total energy of

a system and is the Hamiltonian operator

[16]

(p. 27). The so-called

constraint described by (1) follows from the total energy of the universe being

zero, gravitational energy cancelling out the mass energy.

Hawking’s & Hartle’s solutions

of this equation describe a universe that has no beginning, the Hartle-Hawking

state,

[7]

. Hawking

[8]

explains this in simpler terms

as well: time must have been indeterminate there on the smallest scale in that

quantum state, because of the extreme gravitational warpage of space-time at

that moment,

[8]

(p.

172). The time t=0 therefore is not precisely defined and at these

scales time reduces to a fourth spatial dimension.

So, the universe has no exact

measurable beginning. Hawking calls this the ‘no-boundary-condition’,

[8]

(pp. 172-173). It makes it

impossible to trace the development of our universe from the beginning to this

time in a deterministic ‘bottom-top’ way and, hence, there is a need for a

statistical ‘top-down cosmology’, considering all possible alternative

histories of the universe.

He states that as a consequence of

this, at the very beginning time acted as a fourth spatial dimension, ”In the

early universe-when the universe was small enough to be governed by both

general relativity and quantum theory, there were effectively four dimensions

of space and none of time”,

[8]

(p. 172) This is the starting point of the proposal of this paper.

String theory, however, suggests as much as eleven dimensions, but using the

minimum of four is more economical and easier to understand.

The quantum aspects of the Big

Bang become clearer when considering so-called ‘double-slit’ experiments, with

a light beam split in two that are directed at a wall with two narrow slits.

Especially the variant where only one photon is fired at a time is exciting.

The same interference patterns then arise as with continuous beams of photons,

so the probability waves of single photons interfere with themselves, as it

were. One photon behaves as if it passed through both slits. That can only

happen if the photon itself follows all possible alternative paths

simultaneously, as it were like a split probability wave. So, the behaviour of

the single photon can be seen as a superposition of all possible alternative

paths it follows, so alternative histories,

[8]

(p.104).

Hawking’s and other’s point about

the probabilities is that a quantum experiment will only have a certain outcome

when it is performed. The Big Bang can be regarded as such an experiment

[8]

p. 179), where the universe in

the quantum state may have had a statistical probability distribution of many

‘alternative histories’, following the interpretation of Feynman. Maybe 10500

ones as ‘String-theory’ and the more general ‘M-theory’ suggest,

[8]

(pp. 152 and 181). At page 77

Hawking states that “the universe does not have a single existence or history,

but rather every possible version of the universe exists simultaneously in what

is called a quantum superposition”.

This does not a-priori imply we

still are in a real a state of superposition between all, or part of these

alternative histories now, but this paper will argue that this is indeed the

case with our universe, to some extent.

The parameters and hence the

quantum state of our universe are known now. Our universe has known single

values for the fundamental parameters and constants. Of all the

‘alternative histories’, ours is the one that has come true. It has been

performed; we know the outcome. This is only possible when there is an observer

to the experiment,

[8]

(pp. 107 and 179). This where the idea of an ‘observed universe’ of Hawking and

others like Wheeler comes from. The assumption is that man or other sentient

beings can perform this role of external observer, as Hawking and Wheeler

argue, based upon the ‘delayed-choice’ experiment by Wheeler. That shows that

the moment of time where the observer enters the history is not relevant

[8]

p. 106-107).

2.3. Other Relevant Quantum Systems in a State of Superposition

Quantum superposition can be

forced by a beam-splitter like in the famous ‘double-slit’ experiment discussed

up here. It can be forced as well by a dedicated device like in a Qubit or in

an MRI-scanner. A tensor-interaction like in the deuteron may as well yield a

superposition state. The latter will be discussed into more depth in the

sequel, since it might be very relevant to the behaviour of our universe.

A deuteron Is a bare proton and a

neutron, glued together, without electrons. The binding force between the

neutron and the proton is the sum of the resulting forces of the

superposition of two quantum spin states, see Bethe

[17]

. This force would not be

strong enough if the deuteron were in just one of those states, according to

Khalili

[18]

(p. 20).

This is essential to the following

part of this paper: as with the single photon in the double-slit or with the

deuteron, our universe could still be in a superposition of multiple

histories. The result should be able to interfere with itself very well like

the single photon, and forces like gravity might add up like in the deuteron.

This, at its turn, leads to a pair

of testable hypotheses of the nature of dark matter. This now is presented as

well as the path of thinking that led to it. But firstly, MOND and TeVeS

theories are briefly visited in the next chapter.

3. Introduction to MOND and TeVeS Theories

Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND)

is an empirical alternative to the hypothesis of dark matter to explain why

galaxies and open clusters [19] seem not to obey Newton’s law of gravity. It is explored in this

chapter and among other described by Schilling [20].

First published in 1983 by Milgrom

[1–3], the aim was to

explain why the observed velocities of stars in galaxies are larger than

expected based on Newtonian gravity. An example of the so-called ‘rotation

curves’ discussed down here, is shown below in

Figure 1. It shows the

rotation velocities as a function of radius from the centre of a galaxy, as

well as the logarithmic brightness curve, which is a good measure for radial

mass distribution. It comes from Lelli [11]. It is one of the 175 galaxies studied with the SPARC satellite

(UCG09037). The black dots are observed velocities, to be called Vobs

in the sequel. They are higher than the velocities calculated from

gravitational attracting force according to Newton’s law of gravity. Taking

this equal to the centrifugal force, results in the theoretically expected

velocity, called Vbar, the blue line.

Figure 1.

rotation curve sample [

11].

Figure 1.

rotation curve sample [

11].

If at large radii both the total

observed gravity decrease linearly with radius, just like the opposing

centrifugal force, the observed velocities, Vobs, can remain

constant over a long range of radii as can be seen in

Figures 1 and 7 and as is

shown by Lelli [9,11]

for many of the other galaxies with Spitzer photometry. See Annex 3 for all the

rotation curves.

Milgrom noted that instead of

assuming dark matter to solve this, the discrepancy might be resolved if the gravitational

force experienced by a star in the outer regions of a galaxy would vary

inversely

linearly with radius

R (as opposed to the inverse

square of the radius, as in Newton’s law of gravity). MOND has been fitted

empirically such that it differs from Newton’s laws at extremely small

accelerations that are characteristic of the outer regions of galaxies with

formula (2). The transition would occur below an acceleration of

am

= 1.2 x 10

-10 m

2/s, Milgrom’s constant. The area with

lower gravitational acceleration is called the MOND regime. The theory needs an

interpolation algorithm for the acceleration beneath

am in a

pragmatic manner. The interpolation depends on the variable µ (

) with

, so the predicted total

acceleration over Milgrom’s constant, as follows:

and the Newtonian acceleration g

Nis related to the resulting total predicted acceleration

a

through:

Since this equation needs to be

solved iteratively when it is used to predict the total acceleration from the

Newtonian, and since this interpolation formula allows for inversion, it can be

rewritten as follows:

See for example Platschorre [21]. With back and forth

calculating a series of values for and it can easily be shown that this

formula works correctly.

In terms of the Newtonian

gravitational potential of the visible matter,

, this can be written as follows [4]:

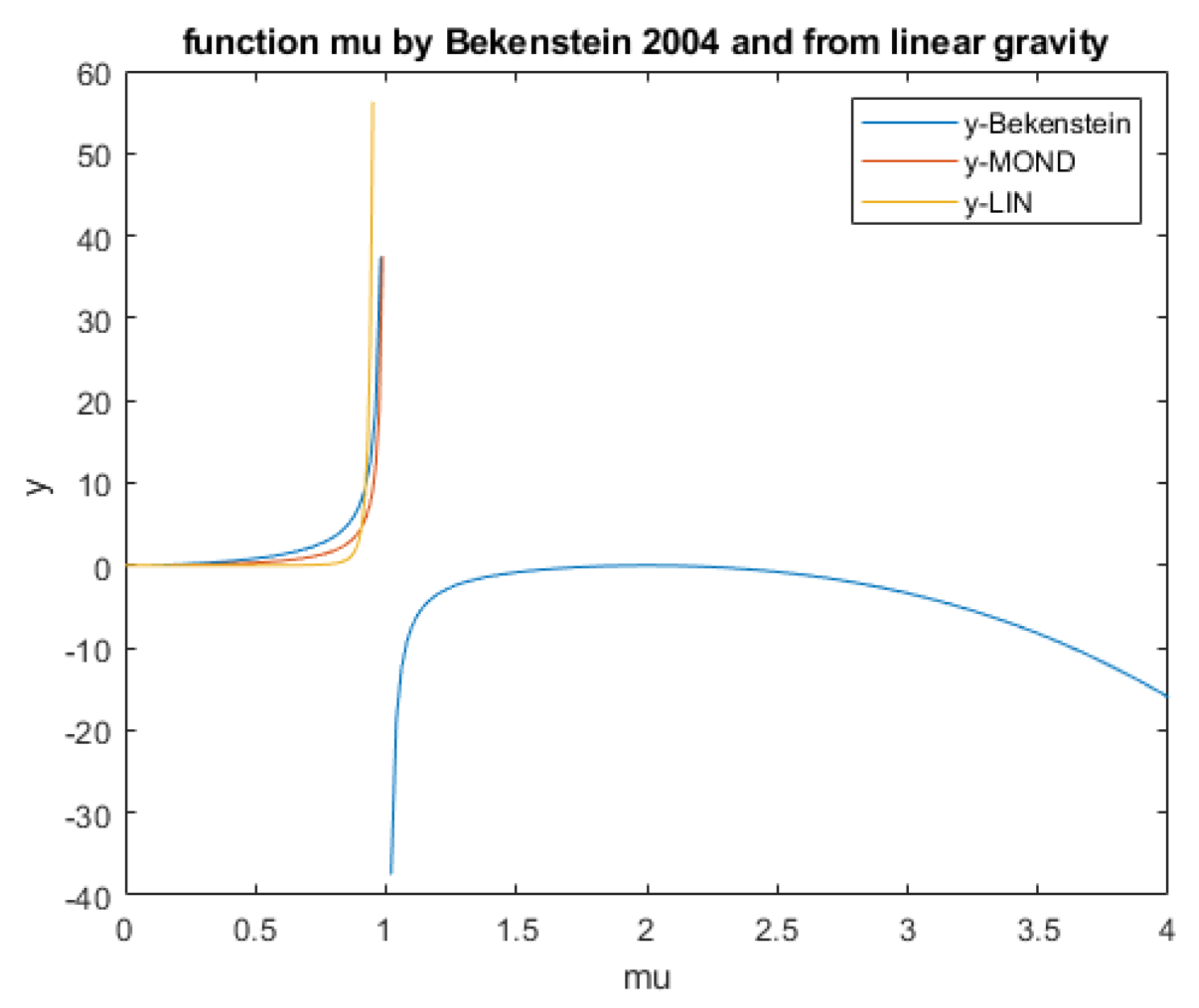

Bekenstein uses a parameter y

= ||2/am2 which

equals x2. So: µ() or simpler µ(y), which will be used in the sequel. He gives an

alternative for µ(y) resulting from formula (2).

However, this MOND theory of

gravity does improve the calculations on the velocities of stars but does not

explain the observed deviations from Newtonian mechanics. Furthermore, as

Bekenstein [4]

mentions it does not specify how to calculate gravitational lensing by galaxies

and clusters of galaxies and it violates conservation of momentum. For the

latter, a theory derived from an action principle is needed.

Early attempts to generalise MOND

by making a relativistic version of it were relativistic AQUAL [4,22] and Phase Coupled Gravity

(PCG) [4,22].

Fascinating is that PCG yields a description of total gravity as a sum of two

competing fields, one with quadratic decay of gravity with distance x

and one that decays linearly [4] (formula (17) at p. 7). This is consistent with formula (7) in the

next chapter. It is interesting to note that Covariant Emergent Gravity (CEG) [5,6] as well yields a sum of two

competing fields, as Platschorre [21] shows.

But both AQUAL and PCG attempts

had problems like waves propagating faster than light and incorrect light

deflection [4].

Bekenstein provided a theory, that accounts for this, TeVeS, in

which MOND is reformulated in terms of GR [4]. This will be succesfully applied to the linear gravity hypothesis

in chapter 7.

However, the mathematical

framework of Bekenstein still does not give an explanation for the source of

the additional scalar and vector fields. The paper in hand, presents a

hypothesis that provides a natural explanation for it, one that does not need

any interpolation algorithm and that significantly can improve the MOND

predictions for all galaxies in the database, especially those that are at

large distances from our galaxy further. It is presented down here.

4. A Hypothesis on the Nature of Dark Matter

4.1. Interpreting Linear MOND-Like Behaviour of Gravity

When interpreting the linear

behaviour of MOND, first thing to realize is, that the dependency of

gravitational acceleration g from the radius R can be interpreted

as the sum of two contributions. The case for this will be argued in the

sequel, but here it suffices just to see how it would work out,

Now, there is no need for an

interpolation procedure, like in formulas (2) to (4), above

g = 1.2 x 10

-10

m/s

2, Milgrom’s constant, because taking the sum of the

Newtonian gravitational acceleration and the linear one does this naturally at

the place where they have the same order of magnitude. This reduces the number

of assumptions. Down here it is written as a simple formula, which then is

reformulated in the format consistent with MOND, for further use in chapter 7.

With glinear being

proportional to R-1 instead of R-2 for the Newtonian

gravity.

Thus, the gravitational potential

then, upon integrating

g, takes the form:

k

being a positive constant that depends on the dark matter distribution, to be

discussed in chapter 6 and k2 being some integration

constant. The same potential results from MOND and TeVeS,

according to Bekenstein

[4]

. He concludes that in his theory the additional potential (a term

that is greater than zero) of an isolated galaxy is growing logarithmically

with distance R, in the case it is not spherically symmetric

[4]

(p. 19). According to

Platschorre

[21]

(p.

51), it as well follows from CEG in the non-relativistic limit.

Since

gN is

proportional to

R-2 and

glinear

proportional to

R-1 equation (6) can be rewritten as:

Here c is a smooth function

of the radial position R, that depends on the different contributions of

all masses in the galaxy to the acceleration at a certain R. In fact, g

is the sum of an almost infinite amount of contributions, from all masses in

the galaxy, each with a varying value of c. This will be elaborated in

chapters 6 and 7.

Inverting formula (8) to find

gN

as function of

g, allows this concept to be reformulated in a way

analogue to MOND, so in line with formula (3), in terms of a function

µ(y).

With

y as defined in the previous chapter.

But firstly, it must be shown this

concept holds, for this natural explanation to be satisfactory. This will be

shown in chapters 6 and 7. But firstly, the underlying natural explanation for

this concept will be presented in the next section.

4.2. Exploring the Logical Consequences of Hawkings’s Cosmology

In the sequel, the case is argued

for a natural explanation for the MOND-like behaviour explained in the previous

section, starting from this cosmology and the other elaborations made about

superposition. This will not only merge to a natural explanation but yield an

improvement of MOND too, in the form of a simple physical model.

The crucial observation of the

paper in hand is that if the moment of time where the observer enters the

history is not relevant, as discussed in chapter 2.2, this would give all

possible observers the same causal status.

Now, it is of paramount importance

to realize that there is no natural relationship between the

numbers 1, for one universe, and 10500 for the number of

possibilities, mentioned in chapter 2. Arguing that this number can only lead

to one single universe with sentient beings, has created a fine-tuned number,

which is not the most economical of explanations, since it would require more

explanations itself.

If a universe in which man

originated is a realization of 10500 possibilities, it is irrational

to assume that not at least one more history of the universe, with sentient

beings who can also act as observers, has been realized. Who was first or last

does not play a role in this, as the 'delayed choice' experiments show. We

are then in a multiverse, which state of real superposition, as defined by

[8]

(p. 77), would result

necessarily from the existence of multiple observers. The superposition has

then been maintained in the way presented earlier in this essay. The real

superposition must necessarily exist if man is the needed observer of our

universe. The states will be able to interact with our universe by adding up

certain effects, as in the deuteron or the double-slit experiments.

The additional gravity attributed

to dark matter can be such an effect. The constants of nature in those

universes will have nearly exactly the same value as ours, since the existence

of sentient beings does not allow very different values, as explained by

[8]

(chapter 7 p. 203 in

particular) and by Rees in Just Six Numbers

[23]

.

When one would argue that

universes can never get in a superposition state, one ends in a ‘reductio ad

absurdum’. There must necessary be a real superposition, but there cannot be

one…

But, the values of some of the

forces or energies in our universe, like gravity or the cosmological constant,

or the mass might be explained as the sum of contributions from different

quantum states or histories of the universe if it still would be in real

superposition. Then their value should match the sum of two or more allowed

values conforming to their probability distribution, as defined by for instance

Weinberg regarding the cosmological constant, see Hossenfelder

[10]

(p. 155). Cosmic forces would

then act on the sum of all mass in this superposed universe. The necessary

existence of sentient beings in more than one universe, will then be the

mechanism that maintains part of the original superposition. Because the ‘delayed-choice’

experiment by Wheeler shows that the moment of time where the observer enters

the history is not relevant

[8]

(p. 106), the observers in the parallel universes possess exactly

the same causal status, so they must necessarily all act as observers then.

That might be the natural and necessary cause of such a maintained

superposition state.

This is a logical way of creating

a multiverse from one Big Bang that results inevitably from Hawking’s cosmology

if 10500 is not a fine-tuned number, and it is presented in chapter

4.3 in steps. The result should interfere with itself very well, as the single

photon in a double-slit experiment and yield a sum of binding forces (each with

their own amplitude) like in the deuteron.

For there is nothing outside our

universe that could disturb the superposition state, it could be in that state

forever, without de-coherence effects disturbing it. Since a universe has one

history as defined by Feynman, so a common, shared, set of values of nature’s

constants, its size is not a reason to disturb it either. And that is why

Hawking and others

[7,14]

can speak of the wave function of the universe in the first place.

4.3. The Argument in Steps

The thoughts leading to the

hypothesis can be logically summarized as follows:

Hawking’s cosmology is a logical combination of two well proven theories, quantum mechanics and Big Bang theory, and thus, it is a good description of the earliest stages of our universe.

Our universe results from a Big Bang that was in a quantum superposition state at its start, that can be interpreted as 10500 alternative histories in an 11-dimensional space, using the Feynman interpretation of quantum mechanics and M-theory.

The realization of our universe from the 10500 alternative histories cannot have occurred without a sentient observer.

Our universe has been realized.

At least one sentient observer exists, which can have come into being in the universe following the conclusion of Wheeler’s delayed choice experiments.

Since it is not economical to consider 10500 a fine-tuned number, aimed at creating exactly one universe with sentient being, there still remains a superposition state of more than one alternative histories of the universe. This makes it a multiverse, each universe with sentient beings. This multiverse still exists by means of a state of superposition, which must not necessarily be disturbed by de-coherence, since nothing exists outside the multiverse.

The other universes in superposition can follow a history comparable with ours that leads to sentient beings, but do not necessarily share all our spatial dimensions in the 11-dimensional space, but do have nearly exactly the same constants of nature. From the delayed choice experiment it follows they all have the same causal status.

The gravity of these superposed 11-dimensional universes acts together just like the binding force in a deuteron.

Since there are more ways to yield partly overlapping universes in an 11-dimensional space than fully overlapping, the odds are that there exist multiple universes that share only one or two dimensions with our universe.

Gravity acting in our universe resulting from the 2-dimensional projection of another one, leads to a linear decrease of the gravitational acceleration as a function of distance from a mass.

The existence of multiple universes that share two dimensions with our universe in a state of superposition, forms a natural explanation for the linear MOND-like behaviour of gravity at large distances from the core of galaxies.

An argument like this is as strong

as its premises. Therefore, the word proof or evidence is avoided

here and it is called an argument. In the sequel, this path of thinking

will be further worked out.

5. An Elaborated Proposal for Dark Matter

Here it is important to recall

that mathematically, a linear gravity field, following an inversed linear law,

can only occur in a 2-dimensional universe. Or in a 2-dimensional projection or

intersection of a higher dimensional universe that is proposed here. This is

analogue to the fact that mathematically in our 3-dimensional universe gravity

must follow an inversed square law. That is the starting point for the line of

thought to be pursued in the sequel.

The intersection of these

universes one would appear to one another as a series of mutually

unconnected planar cross sections of the same higher dimensional galaxy, so

with one dimension less. Together the 2-dimensional projections fill the

volume like a stack of papers. This will be elaborated further in the sequel.

It is vital to note, that to get

from one intersection of a galaxy to another, can take an exceedingly long

distance in the 2-dimensional universe. With one dimension more, as discussed

in the previous, this would even concern different galaxies. But what would the

expansion of space dot to this? This is explored in chapter 6.3.

Taking a side-step about the

number of dimensions in a universe within the framework of String-theory i.e.,

eleven is important here. Our 3-dimensional universe does have eight other

dimension that are curled up in the strings of which all matter and energy is

made. This means they are not zero but have the Planck-length Lp. But,

for the sake of economy it suffices to work with four dimensions instead of

eleven.

All the universes could fill the

higher dimensional multiverse in exactly the same manner, but orthogonally to

each other. In the multiverse, what in a 3-dimensional universe seem

independent galaxies at huge distances from another, might be part of one larger

structure in 4-dimensional space, analogue to the 4-dimensional representation

of the bookshelves towards the end of the motion picture Interstellar at

2 h: 16 m.

Now, the proposed natural

explanation for dark matter comes from the line of thought set in motion with

Hawkings’s cosmology and the investigation of MOND-like behaviour in the above.

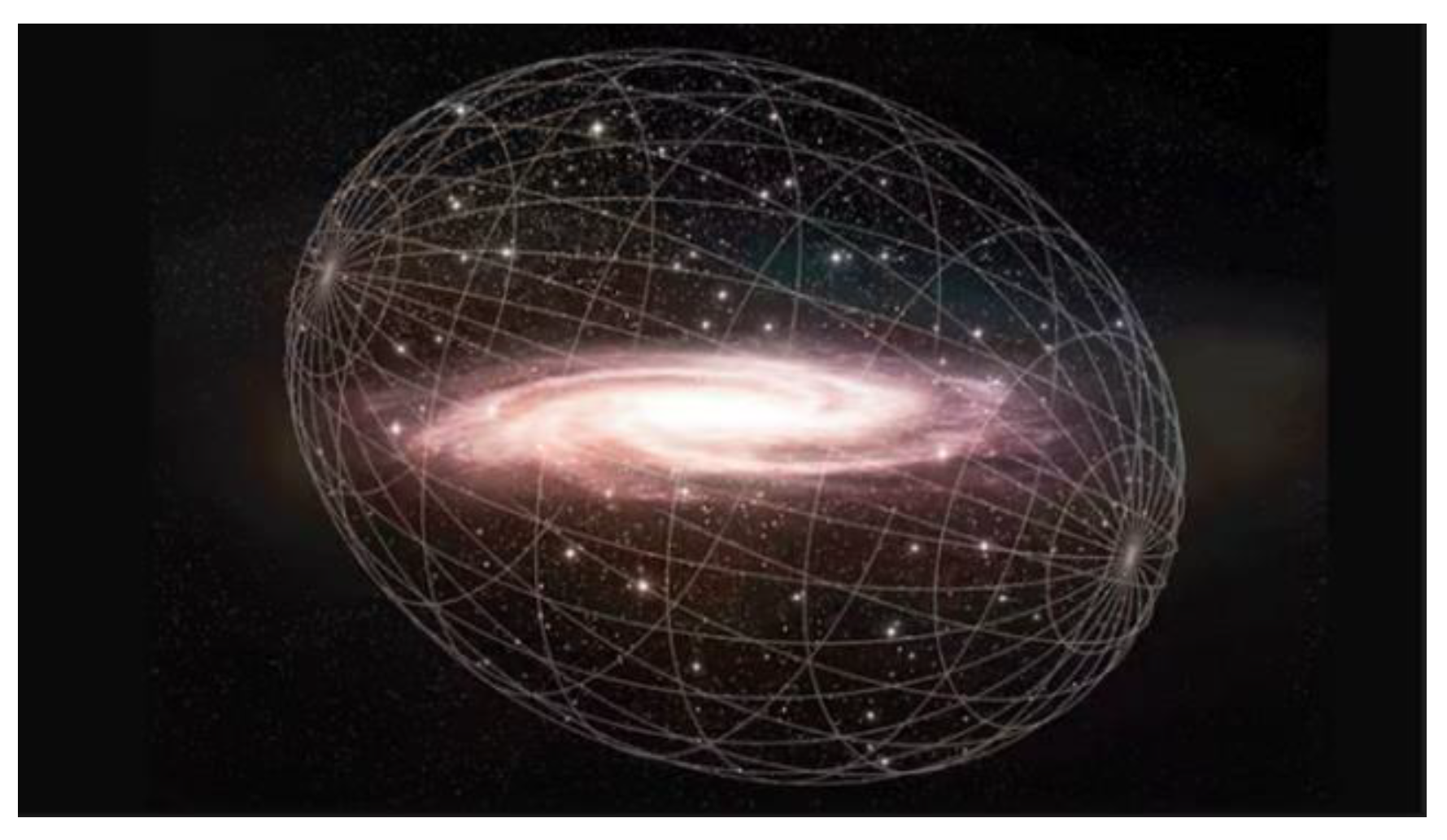

It is that the universe consists of four 3-dimensional universes, existing as

four states of a superposed 4-dimensional space. ‘Our’ third dimension will be

curled up in the strings of the others, just like ours is in the four others,

according to String-theory. At the very start, the diameter of our

3-dimensional universe Lp, would exactly match the thickness in the

other three universes, being Lp too. Thus, they can all be

represented by the same particle. This could be Lemaitre’s ‘primeval atom’ [24]. And this was in a state of

superposition.

At the very beginning, ‘ours’ and

the superposed universes, a multiverse in a sense, would then have a perfect

geometrical and physical match, without any internal contradiction. All would

be perfectly overlapping and thus be causally coupled entirely, since they all

exist the same underlying 4-dimensional space, with, say dimensions w, x, y and

z. All the constants of nature could be the same or differ only very

slightly and just the distribution of the dimensions that are not curled up,

would differ. Then, when the universe starts expanding, the thickness of the

other as seen from our universe would remain Lp. The four expanding

universes fill the higher dimensional multiverse each in the same way, but

mutually orthogonal. The four dimensions will be distributed over the universes

as follows: xyz, wxy, wxz and wyz.

Galaxies that in our 3-dimensional

universe seem independent galaxies at huge distances from another, might be

part of one larger structure in 4-dimensional space. In the other superposed

universes this will be different structures, but the structures will attract

each other by 4-dimensional gravity and tend to overlap in 4-dimensional space.

As a result, on the scale of a galaxy the mass would be located at globally the

same positions as in our universe, but on the scale of individual stars or

solar systems not, since on these smaller scales Newtonian gravity fully

dominates.

As a result, our 3-dimensional

universe would from the start be totally keep filled with three additional

linear gravity fields. Linear because it comes from a two-dimensional

projection of the others in our universe.

Formula 1 can then be rewritten as

follows for the fourfold multiverse:

In a sense (1*) says the total energy of the multiverse is zero.

A variant with only three of those would as well give linear gravity in all directions, but then one of the coordinates would be in the set three times and the other only twice, yielding an anisotropy of sorts. Such an anisotropy would as well occur if the amplitudes aijk in formula (1*) would not all have equal values. Since the said SPARC data give no clue to this option, it is not further elaborated in this paper.

The same applies to universes that overlap in one dimension; this gravity would remain constant with distance and hence, along a closed loop through the universe, this gravity from both sides would cancel out. Three overlapping dimensions would just yield additional gravity with an inverse square law. The said SPARC data gives no indication for that either, since its effects will remain hidden upon fitting the mass-to-light ratios but contributing to the variation in these ratios between different galaxies.

The additional gravity field, i.e. the sum of three 2- dimensional fields, will then naturally be a field with linear decrease of gravity with distance r between two objects.

The dark matter would be there in the Big Bang at the time it was needed to come to the cosmic composition as we know it and create the ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ spots in the background radiation, see Darling [

25] (p. 204), Schilling [

20] (p. 225).

The orientation of the sets of two overlapping dimensions in relation to a galaxy still is an issue. Han in 2023 [

26] showed that the outer disk of the Milky Way Galaxy is warped and flared. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain these phenomena, but none have quantitatively reproduced both features. Han demonstrated that the Galactic stellar halo is tilted with respect to the disk plane, suggesting that at least some component of the dark matter halo may also be tilted. The origin of this misalignment of the dark halo, of approximately 25°, can be explained by the linear gravity theory in the paper in hand, since the orientation of the two dimensions of another superposition state overlapping with ours can deviate from the orientation of a galaxy. There is no reason s galaxy should be in line with these dimensions and hence with the linear gravity field. But a tilting will cause a moment acting on the galaxy, because linear gravity will give a force acting in its own plane, which will act to rotate the galaxy in the direction of the 2-dimensional linear gravity, but that will take time. In the meanwhile, the apparent dark matter halo can be tilted.

In chapter 6 it will be shown this linear gravity proposal indeed works and leads to a good description of the contribution of dark matter to gravity in galaxies. To get there, firstly for all 175 galaxies in the SPARC database as reported by Lelli et al. [

11] and Starkman et al. [

12], the contributions of the visible ‘baryonic’ matter distribution to the gravitational acceleration and from the invisible gas have been recalculated.

The resulting matter distribution has been derived from the brightness profiles and HI gas concentrations as reported by Lelli et al. [

11] and Starkman et al. [

12] and then compared with their results. This has done so as to be sure that the author has performed the conversion from brightness to mass distribution correctly, for gas, disk and bulges, see

Figure 2 and annex 1 where the variables

Vgas, Vdisk and

Vbulge of the SPARC team and the author are mutually compared. In chapter 6.1 this is all explained in depth.

6. Testable Predictions

In the sequel, six predictions that follow from the hypothesis and support for them will be presented.

6.1. First Prediction

The first prediction that follows from the above considerations is that this superposed particle fits in the mathematics of M-theory. It will be a valid solution of the equations of M-theory. They can then be exactly solved for the superposed ‘primeval atom’ depicted earlier.

Now, the boundary condition for this solution would be the existence of ‘our’ multiverse, following the ‘top-down’ way as Hawking argues, since our observed multiverse is the realized one in the ‘cosmic double-slit’ experiment. This would need to be done with a quantum gravity theory based upon this superposition. In line with this, Einstein’s field equations, with some added fields, will have a solution that matches with this hypothesis. This will be studied in chapter 7.

6.2. Second Prediction

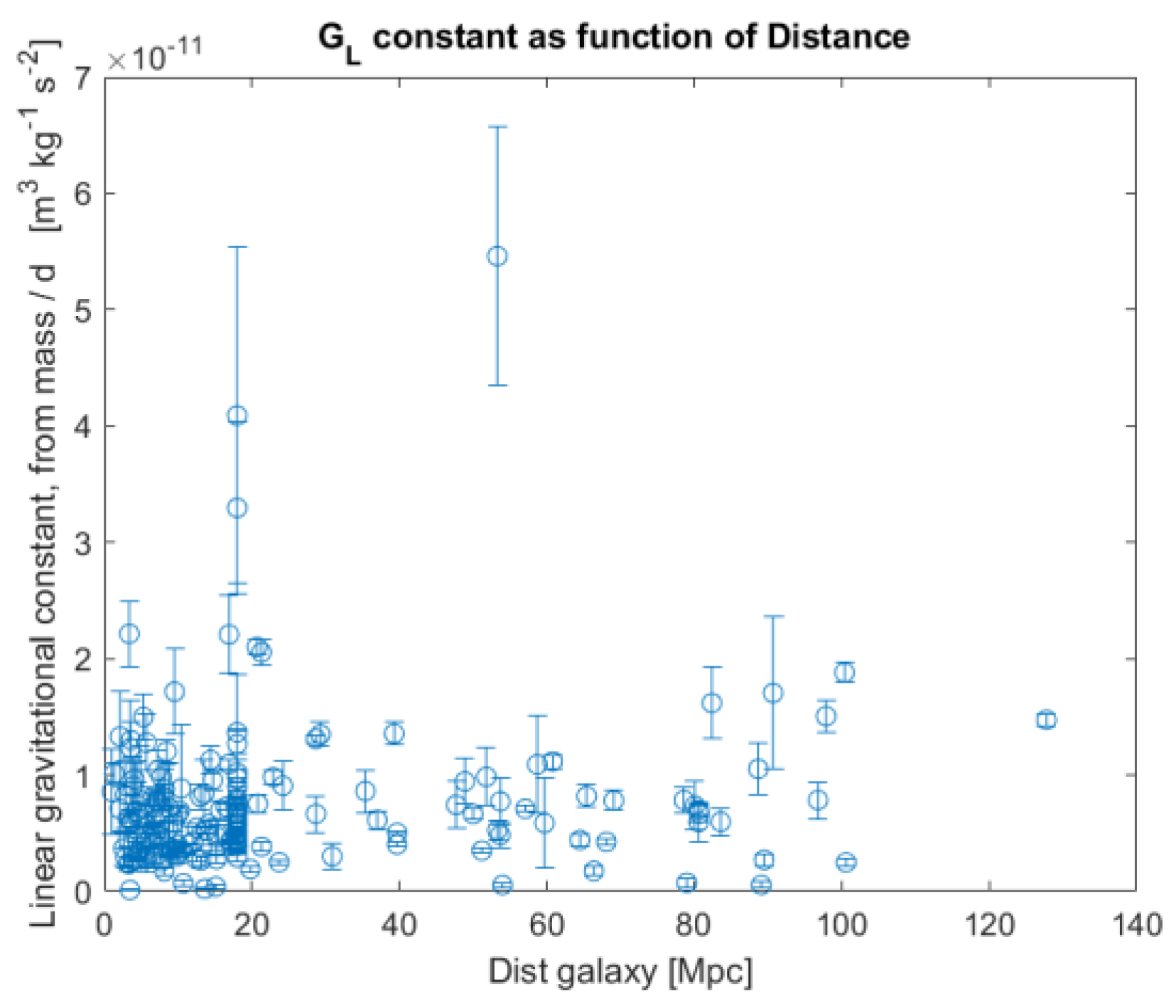

The second prediction is that the additional acceleration can be expressed in the form of a linear constant of gravity

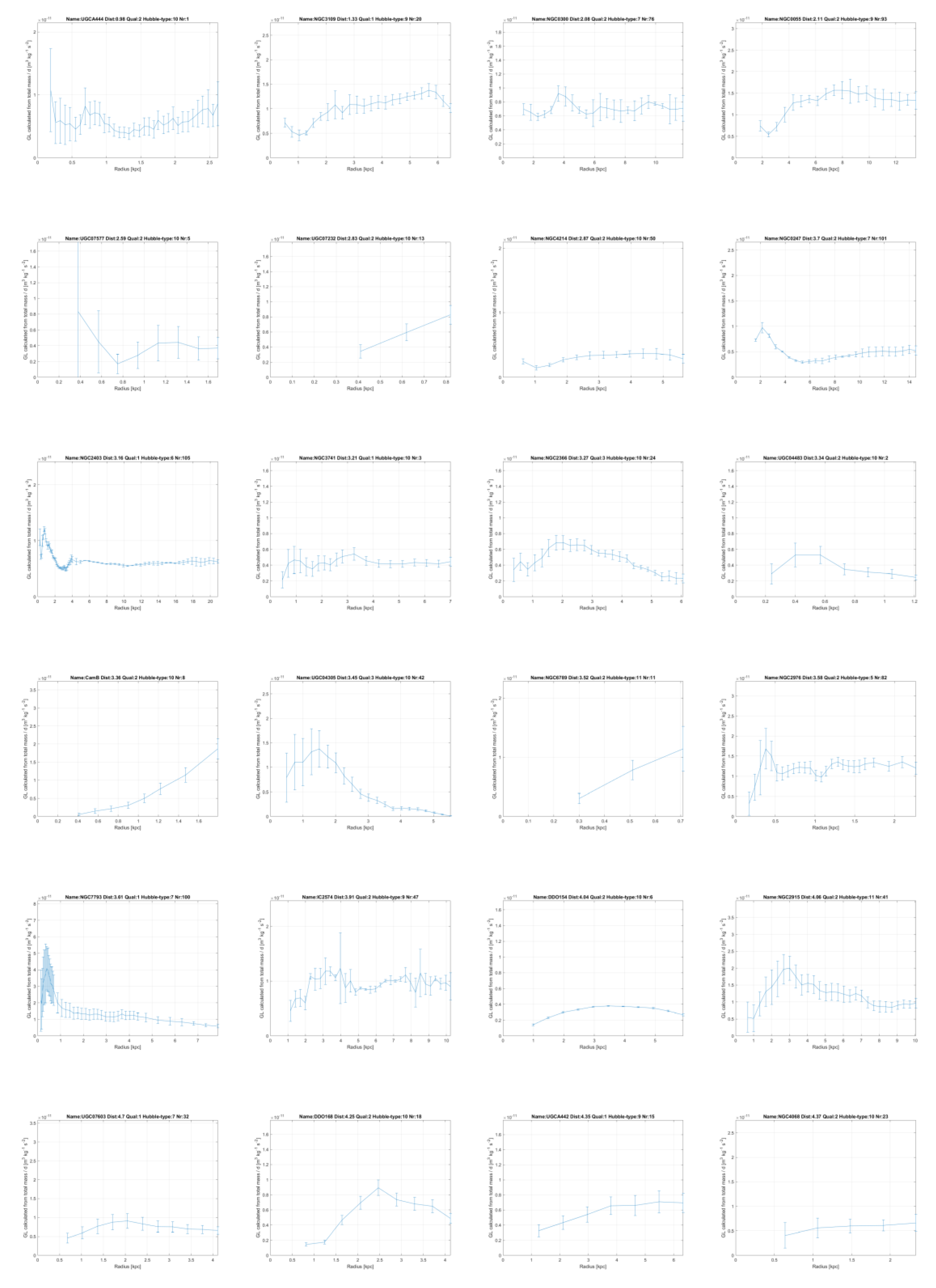

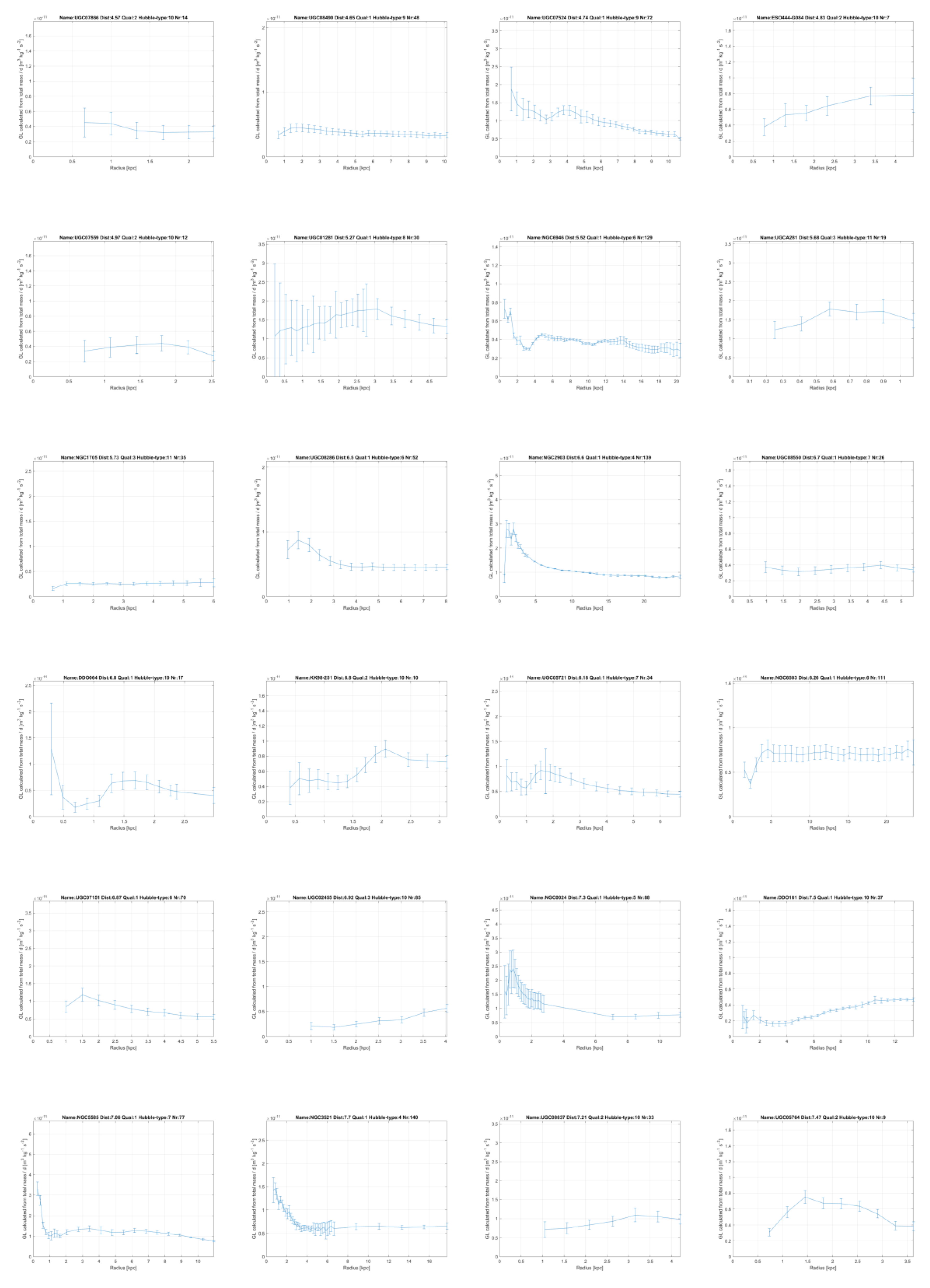

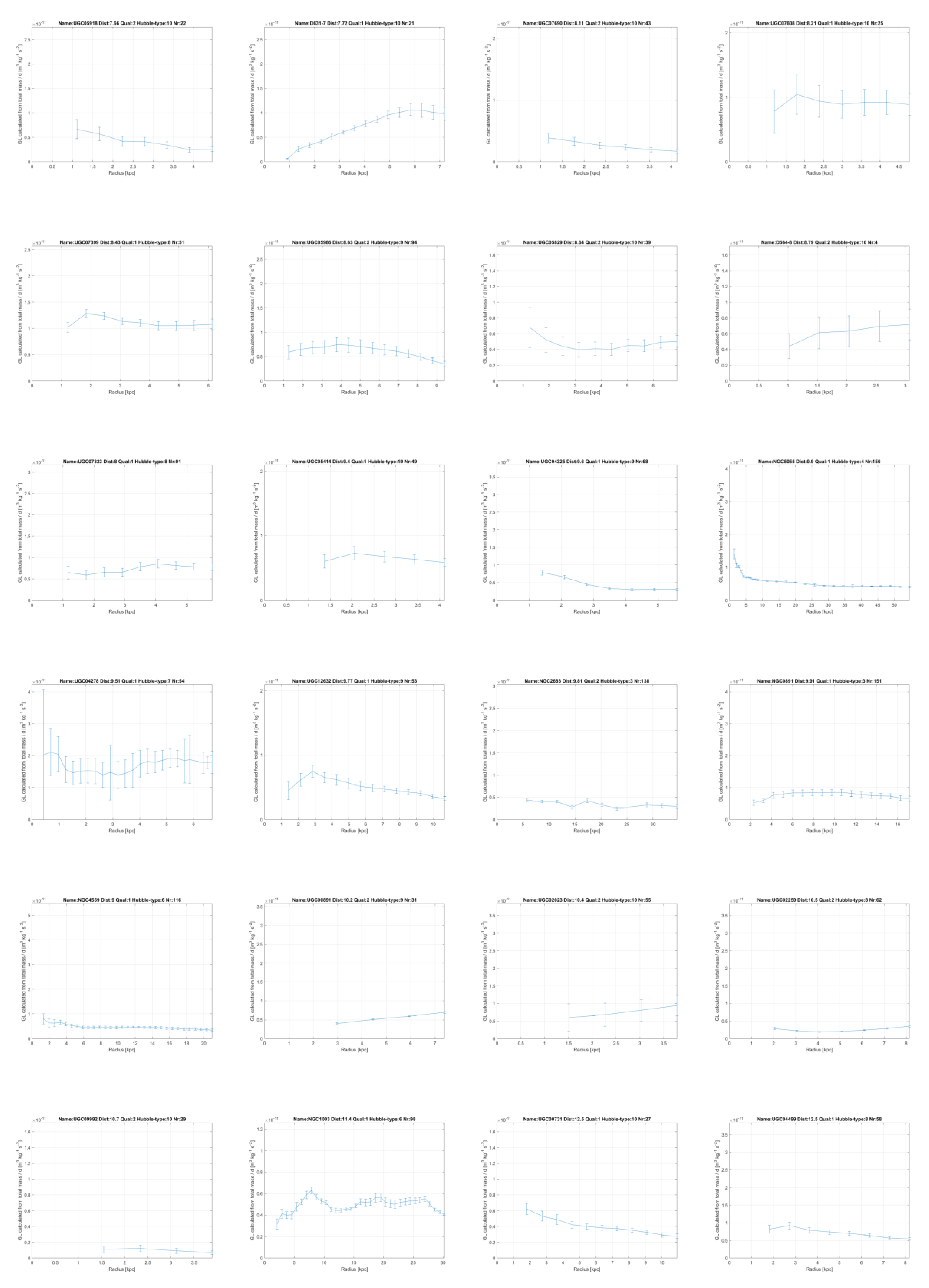

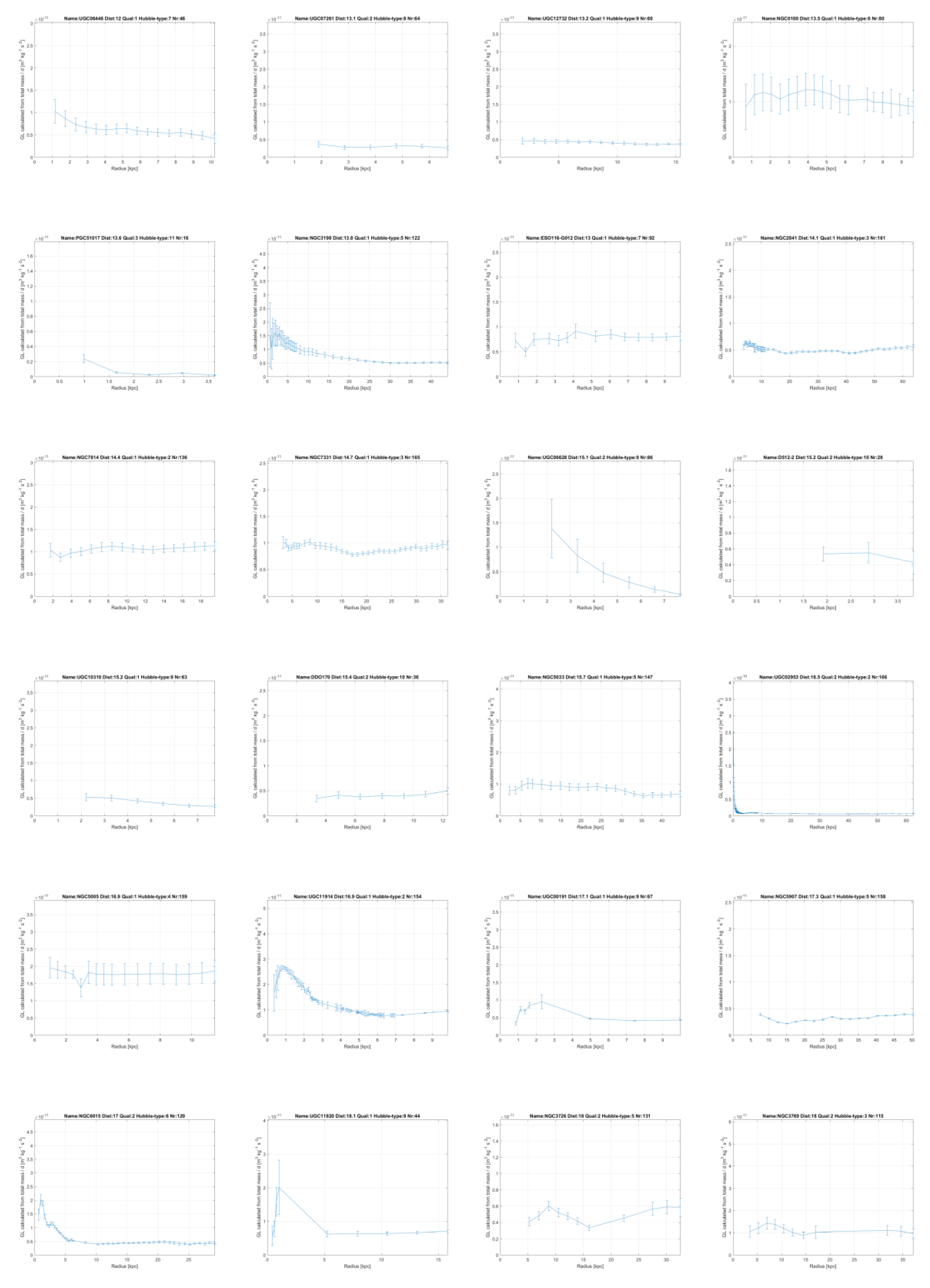

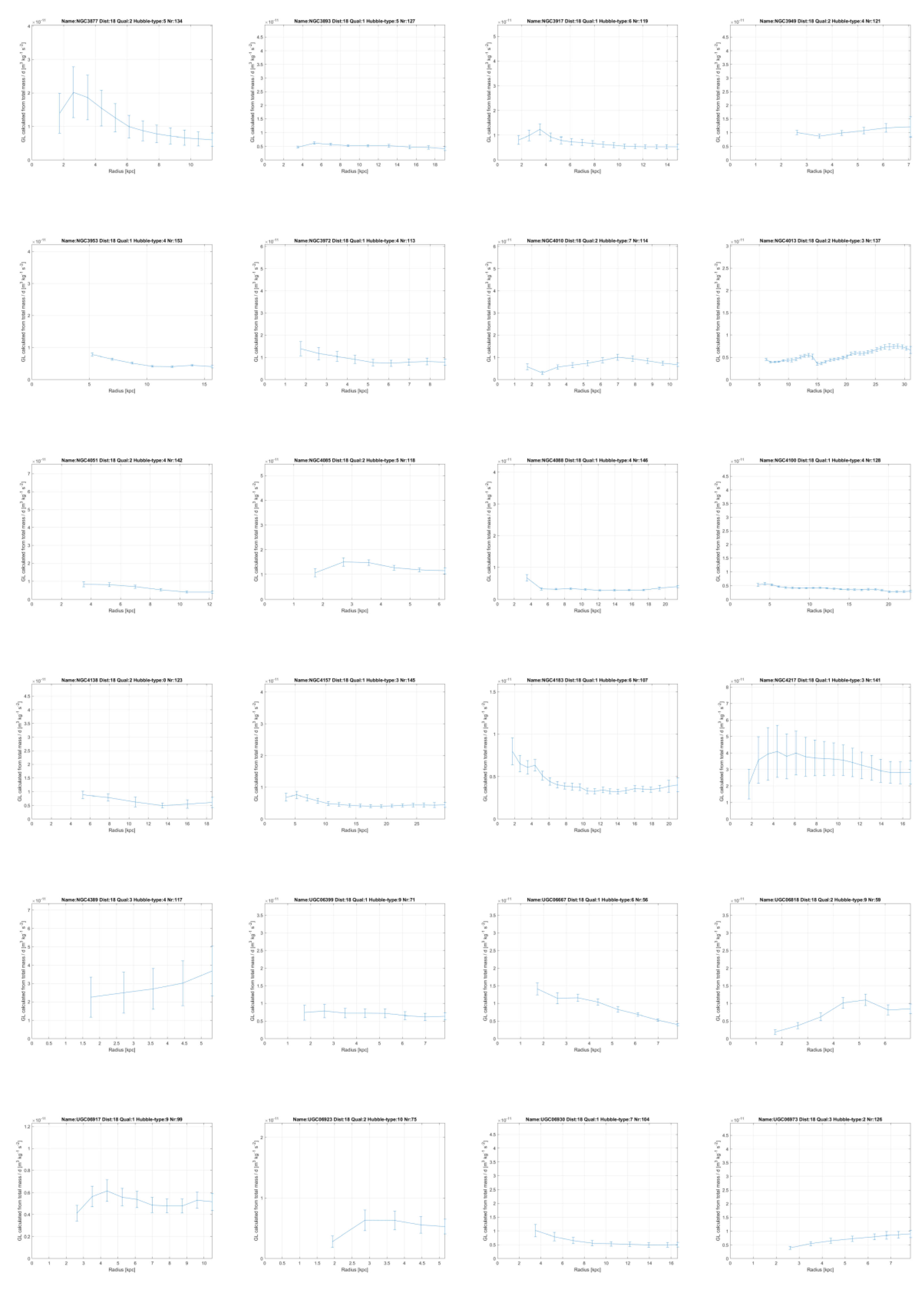

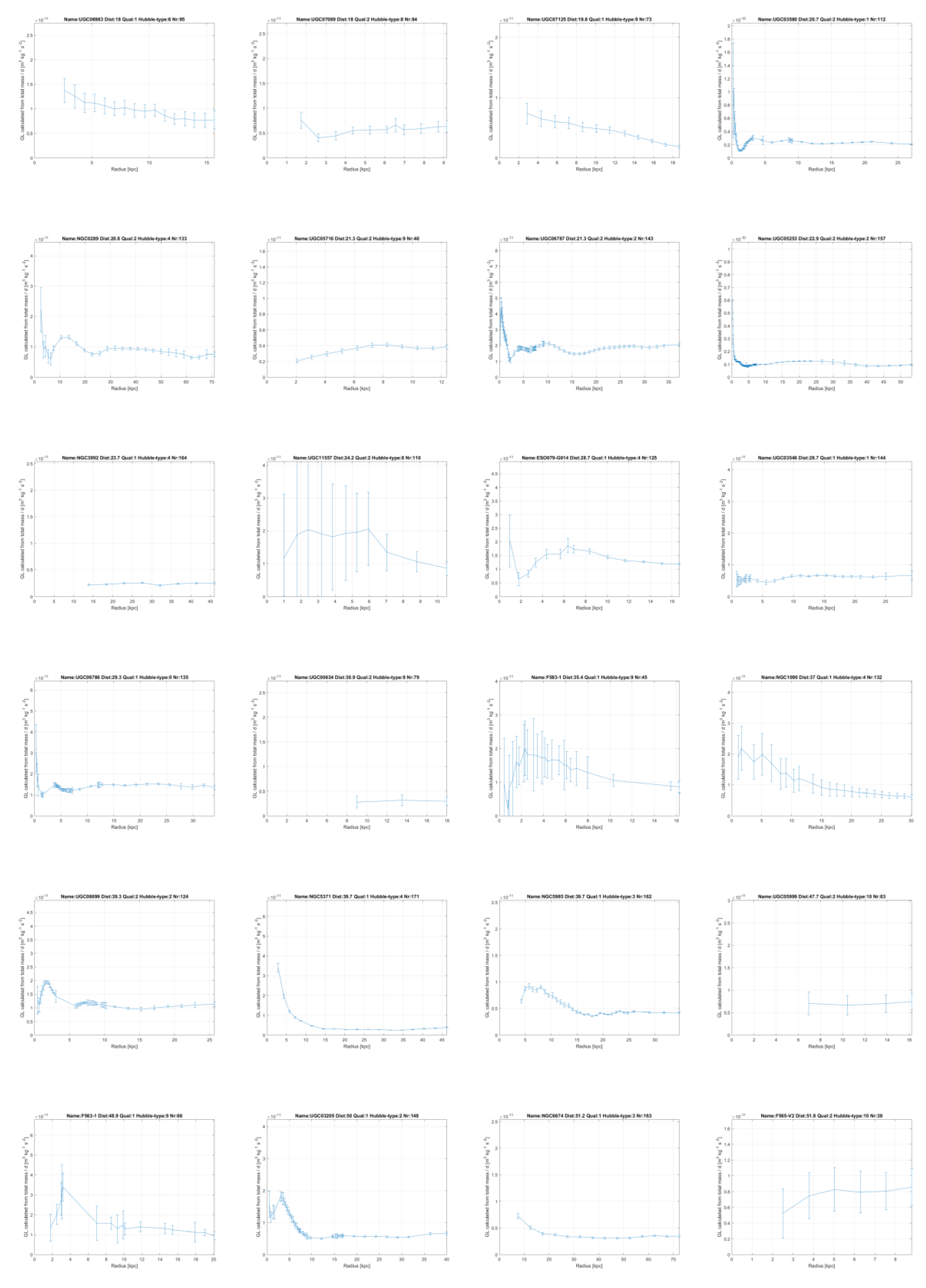

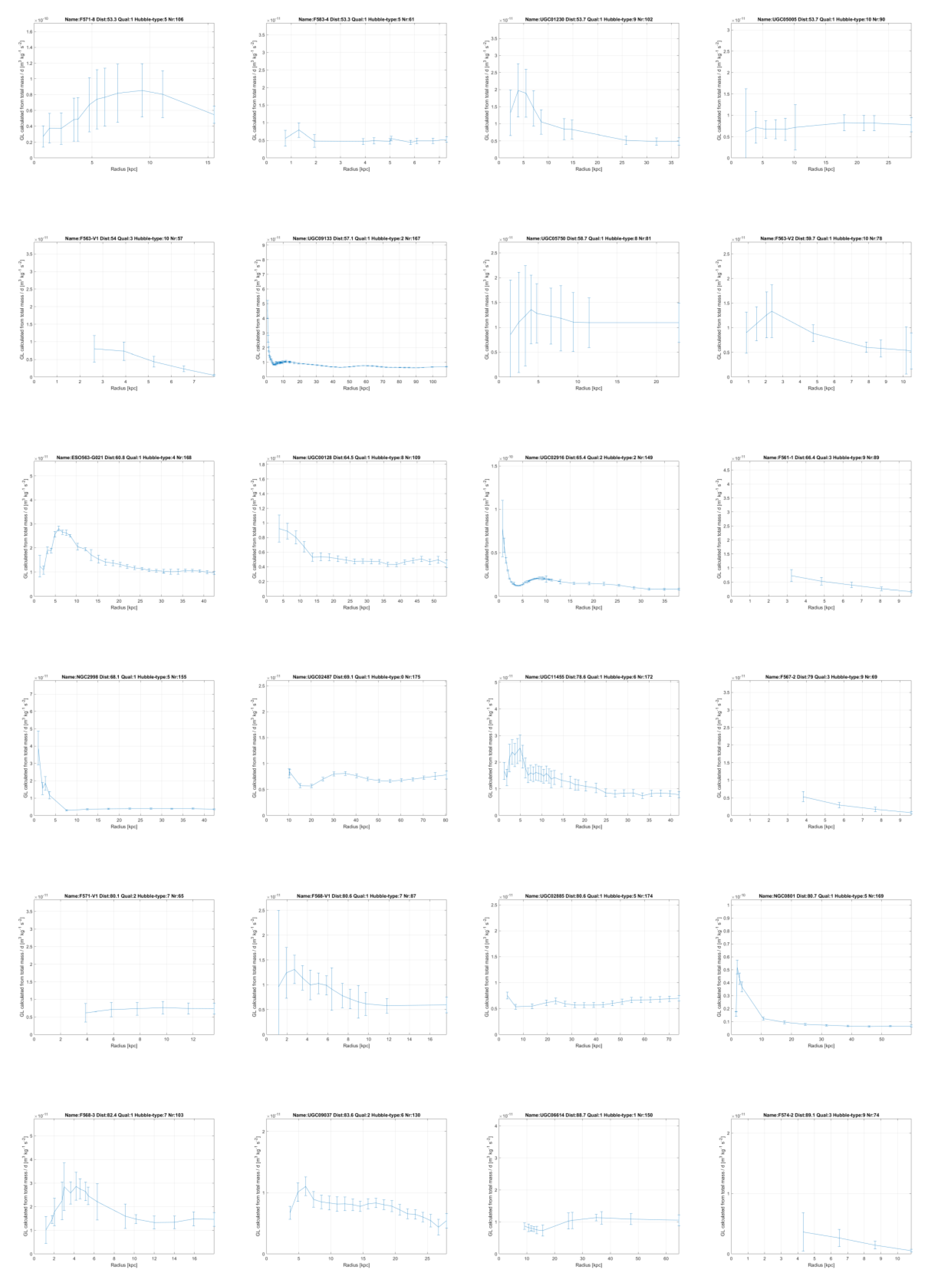

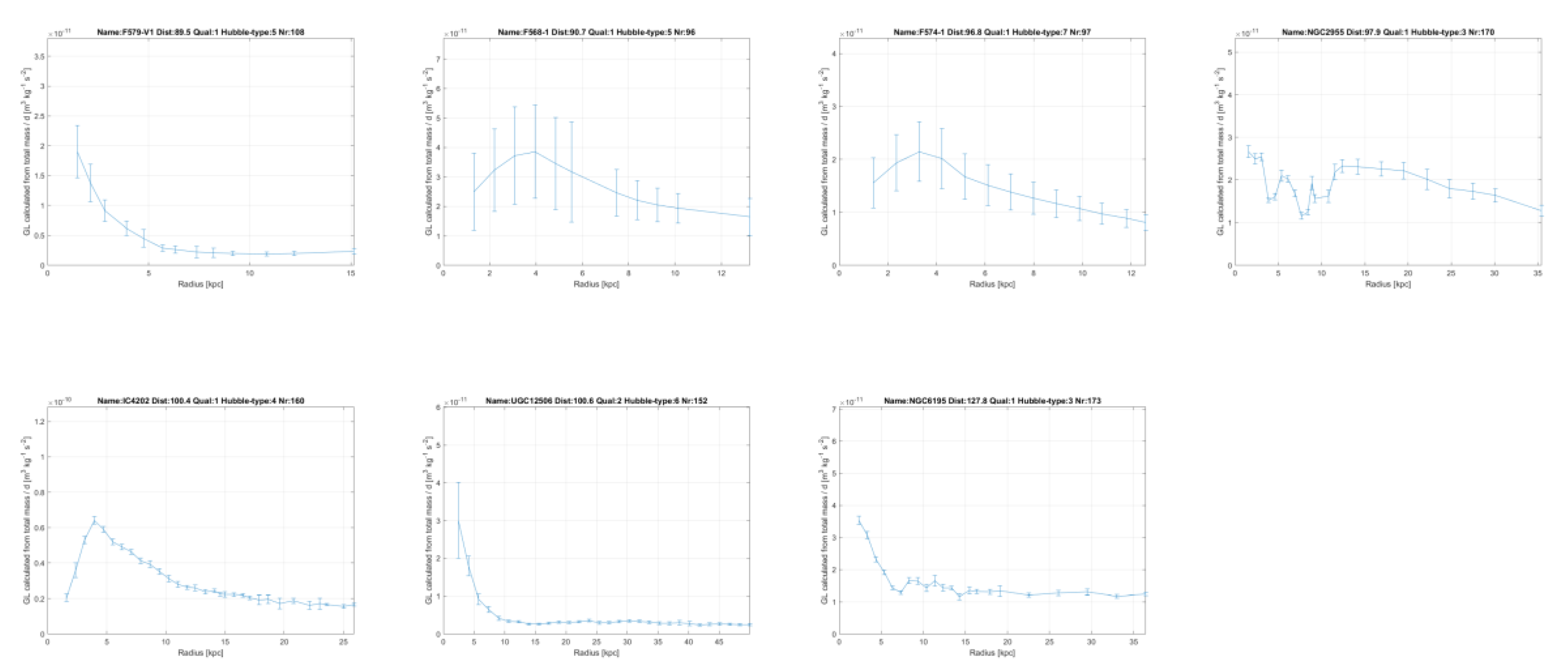

GL, which is constant within each galaxy and will be proportional to the amount of dark matter in a galaxy, which will vary between different galaxies, but to a limited extent. In the annex this linear constant of gravity

GL, has been plotted for all 175 galaxies from the SPARC database measured with the Spitzer Space Telescope [

11,

12] and it is mainly seen to be constant.

The core assumption, as mentioned, is that the distribution of dark matter closely resembles the that of the visible matter, since they attract each other through linear gravity in the 4-dimensional space. This is consistent with the findings of Lelli and Mistele [

9] mentioned in the introduction. They used a new deprojection formula to infer the gravitational potential around isolated galaxies from weak gravitational lensing with the said SPARC data. With these data, they showed circular velocity curves that remain flat for hundreds of kpc, greatly extending the classic result from 21 cm observations. Indeed, they state there is no clear hint of a decline out to 1 Mpc, well beyond the expected virial radii of dark matter halos. This means the common way to project dark matter halos around galaxies cannot be valid. The hypothesis in the paper in hand clearly does not have this problem, since it models dark matter as existing at the same location as the visible matter because of the mutual gravitational attraction.

To assess the validity of this constant for linear gravity, firstly for all 175 galaxies the contributions of the visible ‘baryonic’ matter distribution to the gravitational acceleration and from the invisible gas have been recalculated from the brightness profiles and HI-gas concentrations as reported by Starkman et al. [

12]. This has been expressed in the form of velocity contributions, as the SPARC team did too. For the visible disk contribution, it is called

Vdisk and for the HI gas

Vgas. This done in order to verify and show that the author has interpreted the brightness profiles from the visible disk, from the bulges and the gas mass distributions correctly.

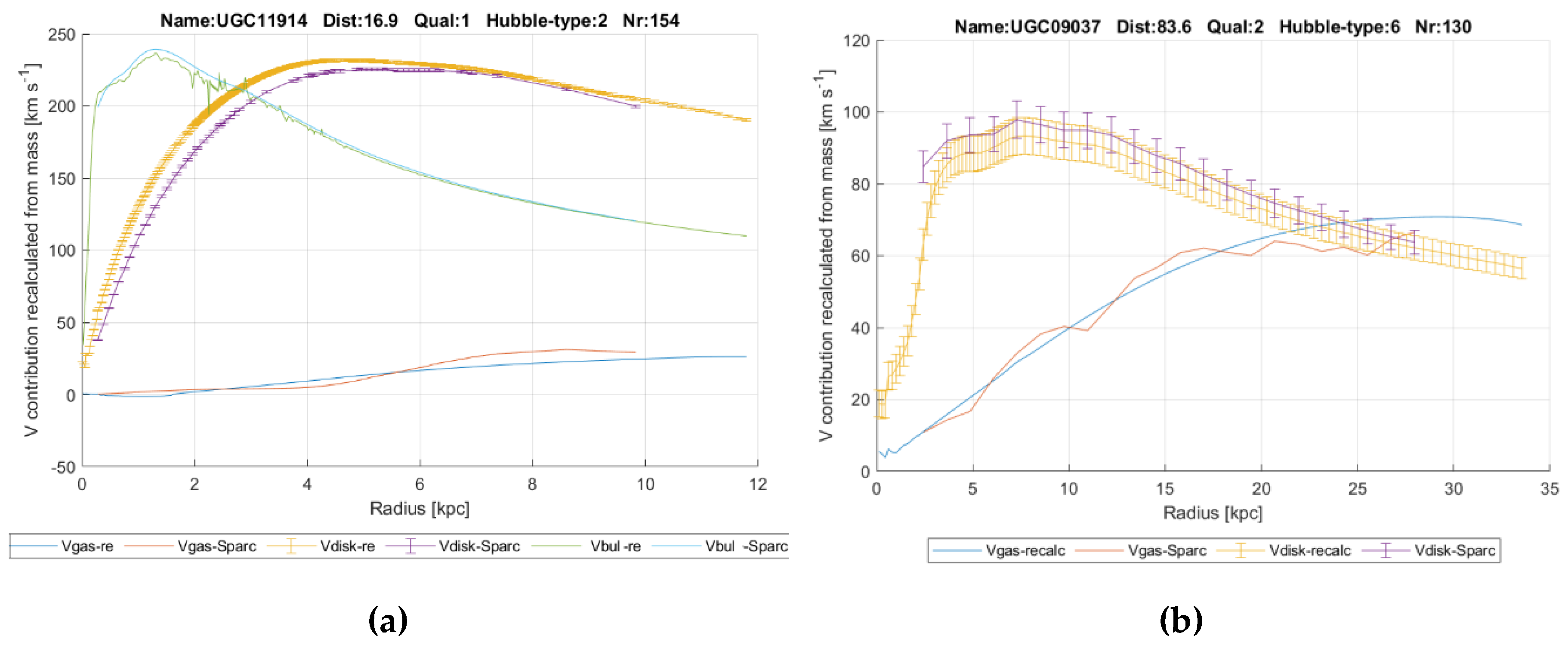

Figure 2 shows the contributions to gravitational acceleration as a function of radius distance. It is plotted for the galaxies UGC11914 and UCG09037, the first of which with a bulge contribution, called

Vbulge. The ‘recalc’ subscripts refer to the values as calculated by the author, The ‘SPARC’ indications refer to the values as reported by Starkman [

12] at the website, in the file MaximumDisk_Mass_Models_mrt.txt. This is the file produced by [

12]. It contains disk brightness profiles as well as observed rotation velocities

, Vobs and bulge brightness profiles as well as the theoretical velocities as calculated by the SPARC team with Newton’s law of gravity. It also contains error estimates, except for

Vbulge and for the HI gas

Vgas. As a consequence, for those variables, no error bars will be shown in the graphs down here and in the Annexes.

The squared theoretical velocities can be added and then result in the total Newtonian or baryonic gravitational acceleration, which can as well be expressed as a velocity contribution

Vbar. But the contribution of

Vdisk and

Vbuls depend on the mass-light-ratio

Yml, as follows:

Vgas in particular can have a significant negative contribution from gas outside the observed radius. Therefore, it is multiplied with its absolute value here to maintain the correct sign.

The mass-light-ratio, Yml is assumed 1 at this stage and will later act as the single fitting parameter.

The contributions are calculated from the brightness profiles under the assumption that in thin disks the latter directly represent a distribution of the mass density. In the bulges this is not true; here brightness represents a cumulative mass density distribution since all observations of brightness run through the entire bulge and each layer adds brightness to the inward layers. So, it must be converted to a distributive mass distribution first, by subsequently subtracting the brightness contributions from larger radii at each observed radius, the part between two radii considered as a slice of a sphere. A complication with this is that the integration path length through each slice of the bulge is dependent on the radius observed. For example, at the most inner radius the brightness contribution from the outmost slice is much smaller than at the second outmost radius, since there one looks a long way perpendicularly through the outmost slice.

The HI-gas densities have been retrieved from the reported total HI mass and from the reported HI-radius by fitting the reported

Vgas to the formula from Martinsson [

27], see formula (11). Three of the parameters that were fixed by Martinsson have been replaced by fitted parameters a, b and

The latter is fitted to match the total reported HI mass of the galaxy. Multivariate regression has been used to find the optimal values in:

Following Lelli [

11], the total gas mass has been multiplied by a factor of 1.33 to account for helium gas as well.

Since, as mentioned, the goal of the calculations in the above merely is to verify and show that the author has interpreted the brightness profiles from the visible disk, from the bulges and the gas mass distributions correctly and not to obtain an improved mass-model, for some galaxies interpolations and extrapolations of the brightness profiles have been made to come closer to the SPARC graphs. In some cases, the extrapolations have been performed based upon the logarithm of brightness, which more or less is linear, but sometimes manual adaption to this profile have been made to, again, come closer to the SPARC graphs.

The centrifugal force

Fc is linearly decreasing with radius

R and proportional to the square of rotation velocity. Thus, the contribution of each mass component to the velocity can be calculated from the respective gravitational acceleration contribution

gc = Fc/m with:

Then gravitational acceleration for each particle at each radius and each angle of it’s orbit can be calculated by summing up masses in each part of the galaxy disk and bulge with (13) for the disk and with (14) for the 3-dimensional bulge:

G is Newtons constant of gravity. Mass outside the orbit of each particle as far as it is not at the side of the centre of rotation as seen from the particle has a negative sign. It has a negative contribution to the centrifugal force after all.

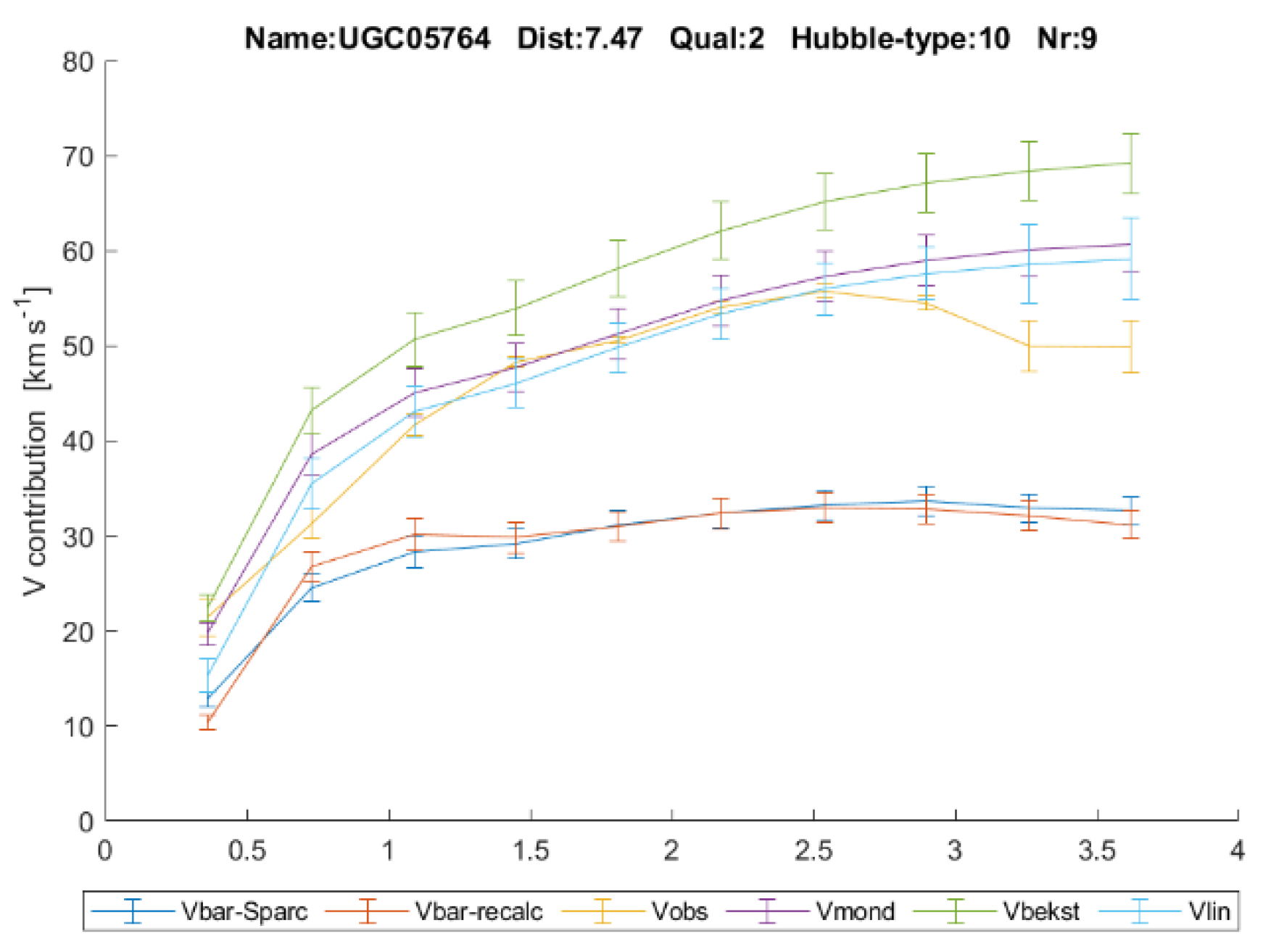

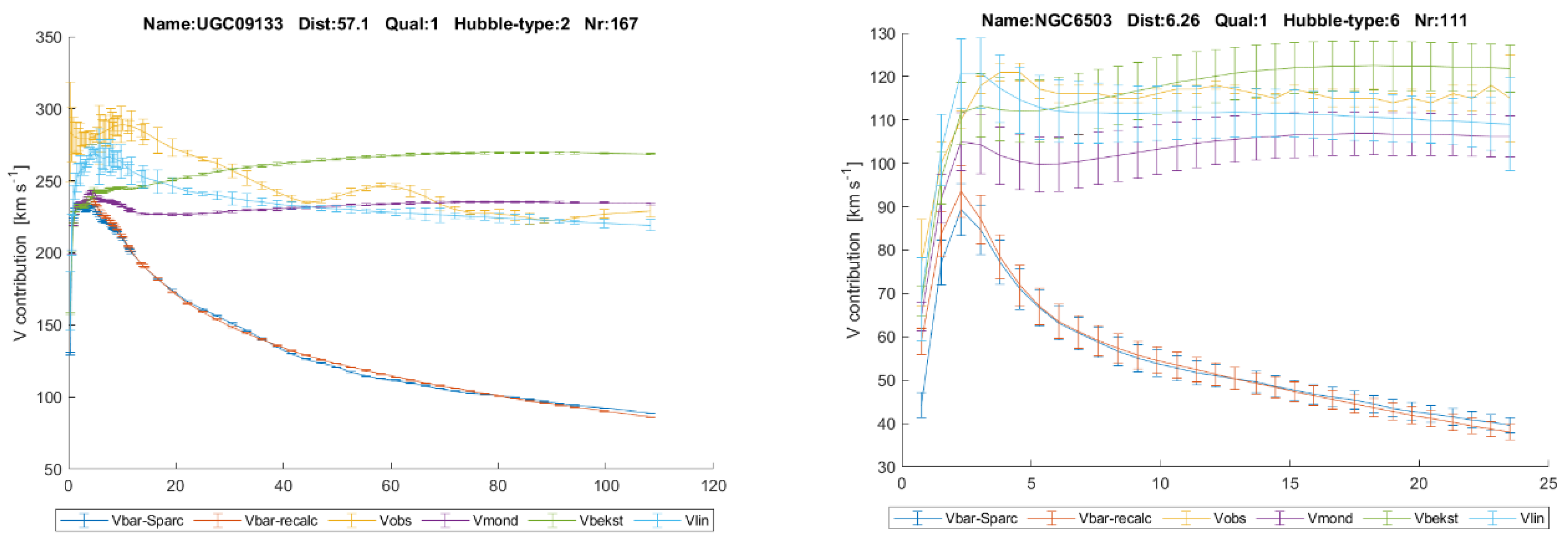

Gravitational acceleration as observed in each galaxy, is calculated from the observed velocities

Vobs i.e. from the centrifugal force. This

Vobs is plotted in

Figure 3, as well as the baryonic contribution to the acceleration expressed as

Vbar, see its definition in formula (10). The lines

Vmond and

Vrecalc will be discussed in chapter 6.4.

The mass-to-light ratio has been used as the only fitting parameter to fit the baryonic rotation velocity, and hence the baryonic gravitational acceleration in each galaxy to the observed values near the core of the galaxies. After that, the hypothesis in hand is used to predict the additional gravitational acceleration at all radii without any further fitting.

The Newtonian gravitational accelerations, expressed by Vbar, are now calculated with a fitted mass-to-light ratio, Yml. It has for each galaxy simply be fitted such that Vbar < 0.85 Vobs, at all radii, so following the sub-maximum disk hypothesis. This assumes that the contribution from the Newtonian gravity never can be larger than the observed value, with some margin at all radii, so assuming there always is some contribution of dark matter at the smallest radii where Newtonian gravity will dominate too.

The error bars have been computed from the error estimates provided by the SPARC team, which concern

eVdisk,

eVbar, eVobs and the error of the disk surface brightness

eSBdisk. But

eVdisk is already entailed in

eVbar, so it is ignored in the following. It has been assumed that deviations occurring in the measurements of the surface brightness at each radius are independent from each other and that those measurements are independent from the measurements of the rotation velocities and from the calculated velocities. The latter means that the correlation between

eVbar and

individual errors of

eSBdisk, each occurring at one radius, is negligible. Furthermore, the contributions of

eSBdisk. at specific radii have been weighted with the inverse of the squared distance

of each mass

mi as defined in formulas (13) and (14) to the observed point.

. The errors in the variables computed in formulas (13) and (14) can then be combined at each radius

R, after Ku [

28] (p. 265) as follows:

The case for linear gravity from dark matter being a 2-dimensional projection of other 3-dimensional universes, makes the additional gravity glinear dependent on the mass density in the plane of rotation since this gravity only can work in a 2-dimensional plane.

It thus depends on the mass density in the plane of rotation M/d. For the disks the thickness d must be estimated, for the bulges this can be exactly calculated. Please note, for the bulges all mass in the bulge outside the plane of rotation is ignored and only the mass density in that plane contributes to the observed rotation velocities. It will be shown this holds very well.

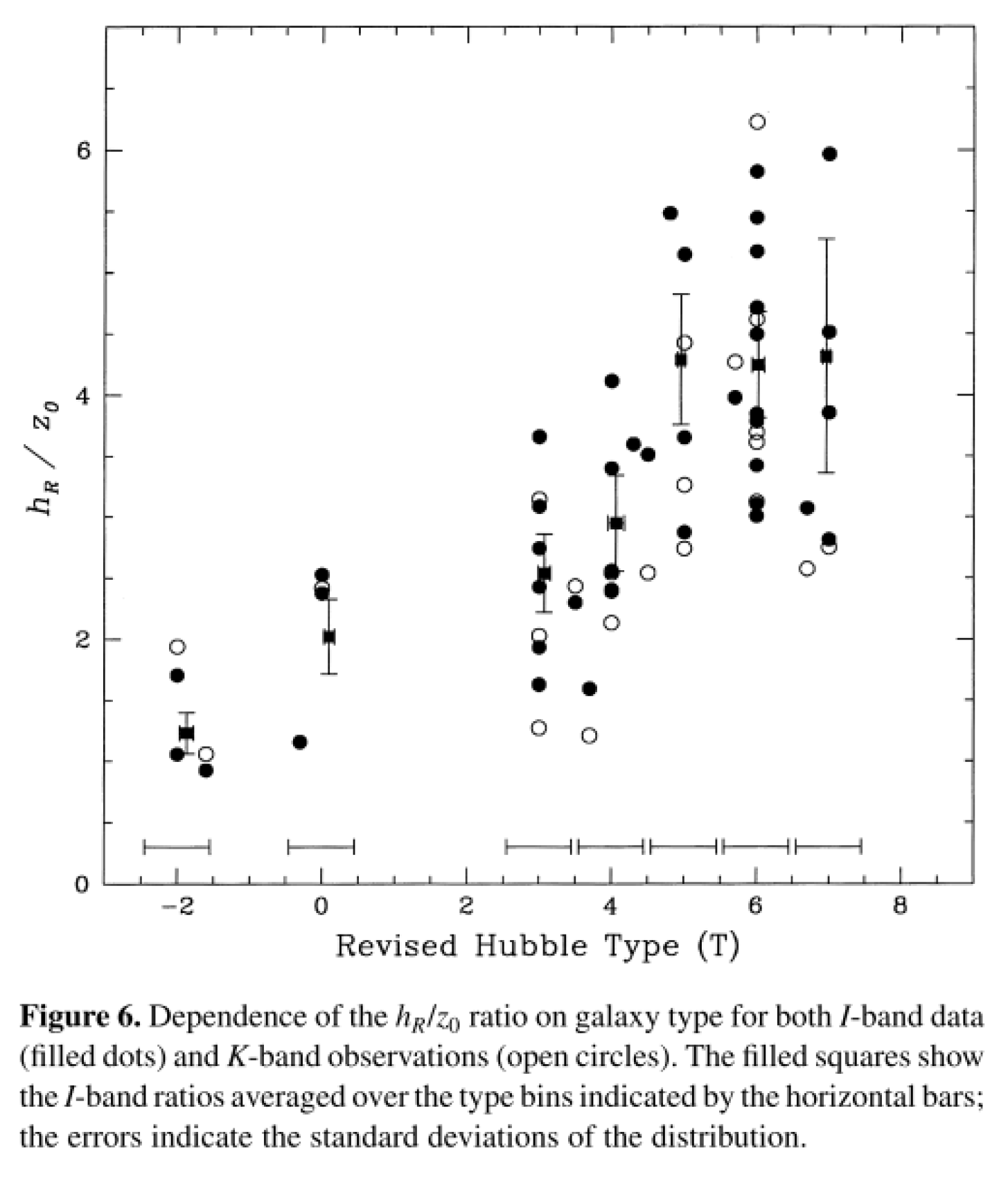

The thickness

d has been taken equal to the vertical scale length z

o as calculated from the disk scale length ratio

hr /z

o, defined after Kruijt [

29] (p. 11) and Sparke and Gallagher [

30] (p. 202). The latter reference states at that page that typically the disk is about 10 % as thick as it is wide, so

hr /z

o ≈ 0.1. But, calculations by the author show that better predictions can be made if this ratio is made dependent of the Hubble type of a galaxy. The ratio

hr /z

o depends on the galaxies’ Hubble type after De Grijs [

31], see

Figure 4.

The definition is as follows:

GL is the linear constant of gravity. From which follows:

The mass density

M/d is calculated over the full two dimensions of the disk and the rotation plane through the bulge and the gas cloud, comparable with the procedure in formulas (13) and (14) so over all other particles

i at radii within the observed radius and outside, for all azimuths. This has been done in a numerical manner in patches, so with a limited resolution of radial distances and for 24 azimuth angles and using one mean value for

d, the disk vertical scale length, in a galaxy.

In the bulge, the 3-dimensional distribution of the bulge mass is exactly known, so no assumption for

d is needed. Here

m’ is the mass density in the plane of rotation:

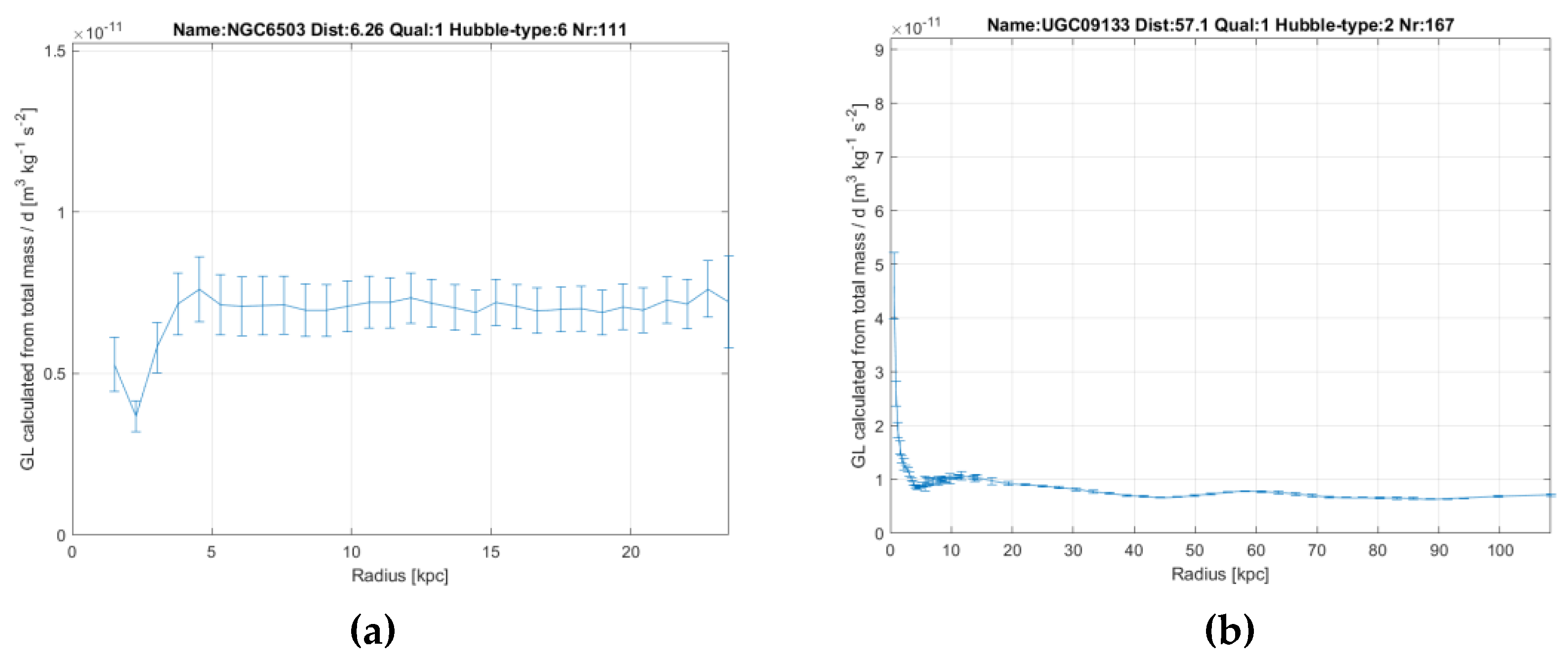

Since no assumption for

d is needed in a bulge, they typically show more constant values. In

Figure 5 two typical examples are depicted: NGC6503 and UGC09133. UGC09133 is a huge galaxy and has a significant bulge. The constant value of

GL extents over more than 100 kpc (!). The great majority of the galaxies show this constant value, or a clear convergence to a constant value at higher radii.

It should, however, be noted that in the disk and gas cloud a certain amount of ‘viscosity’ because of magnetism occurs, see Begelman & Rees [

32] (pp. 66 and 67), This yields an exchange of angular momentum over the disks cross dimension. As a result, still one value of

Vbar and

Vobs can be attributed to or measured at each radius in the galaxy.

The reformulation of the linear gravity concept in line with MOND in formulas (8) and (9) in chapter 6, so gravity modified by

µ(y), led to a factor

c. The meaning of this factor becomes clear now: for every mass patch

mi at a position

Xi it is some ratio of the mass

mi and the thickness

d and it contains

GL over

G. It becomes (the subscript

i added to stress it has a dedicated value for all patches

mi):

The size chosen for a patch, i.e.. the resolution of the calculation, does not affect

µ a priori, since, for instance, doubling

mi doubles

gN and that makes the term

double as well, and so

g in formula (9). For this reason, this formulation is free from the violation of conservation of momentum and the paradox Bekenstein mentions regarding MOND [

4] (p. 2) and can be used to predict gravitational acceleration from a given mass distribution.

All the values of

GL at the highest reported radii of each galaxy have been plotted in

Figure 6. They show a certain bandwidth, which indicates that the amount of dark matter can vary between different galaxies and have a different proportion to the visible matter. After all, the values of

GL represent the effect of the matter in the superposed universes as observed in our galaxies. The amount of matter in the galaxies in the superposed universes can vary according to their history, since there is no fundamental reason why it should be exactly distributed as in our universe. However, in the sequel it will be shown that assuming one mean value for

GL nevertheless can yield better predictions for the rotation curves, starting from the visible matter, as compared with MOND, formula (4).

6.3. Third Prediction

The third prediction is mentioned already: the 2-dimensional matter density will be slowly decaying, strongly correlated to the expansion of the radius of our universe i.e. expansion of space-time, as described by the Hubble constant, see Riess [

33].

This affects the 2-dimensional projections of universes in one another in the proposed 4-dimensional multiverse. The 2-dimensional projections of other 3-dimensional universes that expand at the same rate as ours, will be stretched, at the same rate as the radius of the 3-dimensional universe, to remain consistent geometrically. Now, to fill the expanding space in all dimensions, additional note papers must be added. This occurs since a 2-dimensional plane with a fixed thickness, i.e. The Planck-length Lp, will have to increase its number of surfaces at the same rate as the other increases its volume to still fill that volume.

The expansion of space will not enlarge a galaxy as such, since gravity and angular momentum will resist to that. It is only the space in between galaxies that expands [

8] (p. 160). Now the projections, i.e. the intersections of the corresponding galaxies from the other 2-dimensional universe, are separate objects with continuously more planes added between them, more and more space appearing between the intersections. But as noted in chapter 5, the distance to cover to get from one intersection to another a plane may be very large. An intersection of a galaxy cannot just hop from one plane to another, not even when the higher dimensional gravity attracts them to another in the cross-dimension.

Therefore, its projections and hence its gravity contribution in the other universe will be diluted and decrease strongly correlated with the expansion rate of the radius of the universes.

The test of this prediction must come from a solution of Einstein’s equations, with an added term to describe dark matter well, as provided by T

eV

eS [

4], which is elaborated in chapter 7. In chapter 7.2 it will be shown this indeed is consistent with these equations, and that a vast decay must have occurred since the start of the matter dominated era. Bekenstein himself concluded that too [

4] (section E p. 21). Since in equation (32) the time derivative of the potential in this equation will be multiplied by the value of

µ, which is inversely proportional to the potential, this gives a change proportional to the value, which is exactly what you would expect for a dilution as described up here.

Besides this, from this prediction, it logically follows that in the past, when the universe was much smaller, the additional gravity must have been much larger. In the small universe of the beginning, it has been larger than Newtonian gravity. The effect of this must be traceable in the initial stages of the evolution of the universe.

Recently a paper published in Nature by Labbé et al. [

34] confirmed this. The James Webb telescope showed there is a very rapid development of large galaxies already at 600 million years after the Big Bang [

34].

Figure 7 is a compilation of photographs from that paper. Following Heuvel [

13] (p. 236), the diameter of the universe over this timespan expands with time

2/3. Thus, the diameter of our universe was roughly 7 times smaller than now. As a result, linear gravity according to our hypothesis was significantly stronger too.

This rapid development of large galaxies is much sooner than the current theories predict. But a much larger gravitational acceleration can account for this, since that will greatly accelerate the contraction of gas clouds and the development of stars and galaxies.

Another prediction, that logically follow from this, is that because of this extra gravity, the rotation velocities of these early galaxies will be shown to be exceedingly higher than what we observe in nearby galaxies. This prediction can eventually be tested.

The question remains to what extent this can be extrapolated back in time into the smaller universe that existed then. Looking back in time, the ratio of linear gravity over Newtonian will not increase anymore when the distances over which it can work at all, start to decrease as well. From that moment the density of dark matter will continue to increase, but the square distance term in the Newtonian gravity will increase more rapidly than the linear one. This perfectly compensates each other at small sizes of our universe.

6.4. Fourth Prediction

The fourth prediction is that with this natural explanation and the formula’s (16) to (19) a prediction model for the total acceleration, glinear + gbar (as defined in formula (6)) can be made that is more accurate than MOND and TeVeS, upon employing one optimised value of GL ≈ 6.4 ± 0.2 x 10-12 [m3 kg-1 s-2].

The proof of this prediction comes from the same 175 measurements with SPARC. To this end, The observed Newtonian gravitational accelerations, corrected with MOND or TeVeS using formula (4) are divided by the observed gravitational acceleration Vobs2/R. Firstly, this was done with observed velocity Vobs at the highest reported radius R at which it was measured. Optimisation of GL has been done such that the r.m.s. error value of the deviations of glinear + gbar from gobs over all radii is minimised. The said error estimate of ± 0.2 [m3 kg-1 s-2] directly follows from testing the sensitivity of this optimisation. It is consistent with the integer values of the % improvement compared with MOND. In practical terms, a step of ± 0.2 reduces the improvement from 24 % to 23 %.

As a confirmation of this, following Ku [

28] (p. 265) the error estimate has as well been calculated as the r.m.s. value of the 175 error estimates of

GL over

(175 the number of SPARC galaxies). This gives an error estimate of ± 0.14 [m

3 kg

-1 s

-2].

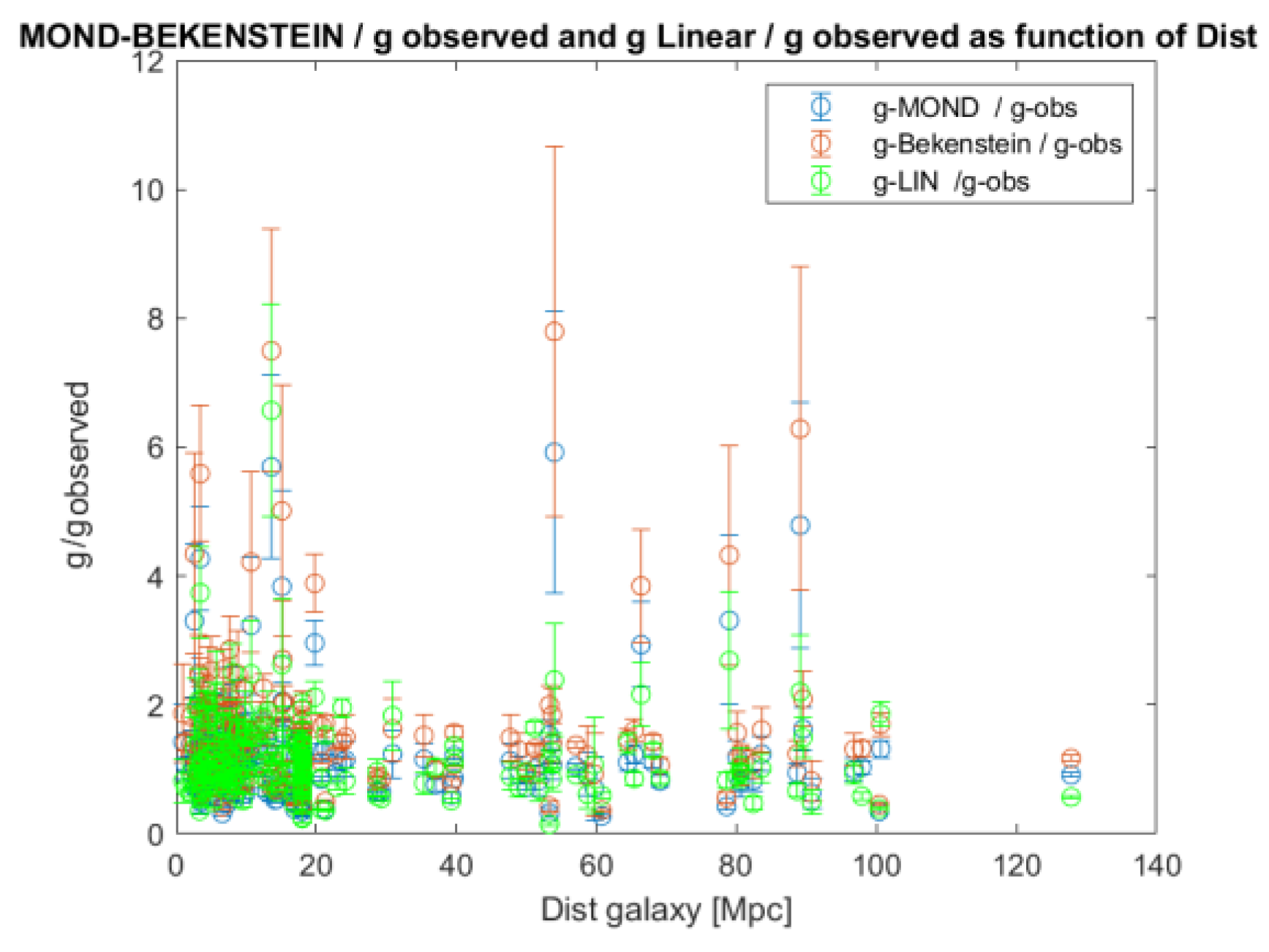

Both the predictions following from MOND and the

µ(y) variant used by Bekenstein [

4] have been plotted as function of the distance

Dist of the galaxy to ourselves in

Figure 8. This can be done, since in galaxies, because of the low velocities and the weak field, the non-relativistic limit of T

eV

eS is applicable and that is equivalent to MOND, only with a different function

µ(y) [

4]. The ratio to the observed value

gobs has been plotted in

Figure 8 for all 175 galaxies as function of distance to ourselves. For linear gravity it shows the smallest scatter from the target value of unity.

As well the ratio of values predicted with the linear model presented in this paper and the observed accelerations, (glinear + gbar) / gobs have been compared for all 175 galaxies. The predictions lie 24 % closer to the observed values than MOND and 26 % closer than TeVeS, when the square root of the deviations of gMOND and (glinear + gbar) compared to gobs are added for all radii of all 175 galaxies. To get here, the function µ(y) from TeVeS had to be solved in an iterative manner at each radius, since it has an implicit form, see chapter 7, and it cannot be inverted.

But this was based upon fitting the mass-to-light ratio

Yml based upon the sub-maximal disk hypothesis. As well it is computed what happens when a constant value is assumed, for example

Yml = 0.5 for all galaxies, like Lelli [

11] suggests as the best overall approximation. Then the predictions lie 23 to 27 % closer to the observed values. The overall performance of MOND is again slightly better than that of T

eV

eS.

This is based upon the velocities

Vgas and

Vdisk as calculated by the SPARC team from the detailed density distributions they measured, resulting in

Vbar. The Newtonian gravitational accelerations as calculated by that team were corrected with MOND as well as Bekenstein’s T

eV

eS. In Annex 3 all the 175 rotation curves with the predictions are depicted. Some show that the predictions with linear gravity,

Vlin, reproduce little more details of the observed rotation curves too, see for example

Figure 9 down here. In the legend T

eV

eS is indicated as

Vbekst in the graphs.

The error-bars in the graphs have again been calculated with formula (15) from the error margins as reported by the SPARC team with the assumption that the different quantities are independent.

The question is what this brings in terms of improving calculation methods for galaxies or simulation models for the evolution of galaxies. The linear gravity is the best way to proceed, but should be extended with a transient term, implementing the decay of linear gravity in proportion with the expansion of space, which is rather straightforward. The application of this calculation scheme, alternative to MOND, would take the following steps for a given radius R in a galaxy:

Calculate the Newtonian gravitational acceleration at R, from the baryonic mass distribution with formula (13), for bulges with formula (14).

From the same baryonic mass distribution, already available from step 1), calculate the sum of mass/distance at R, only taking the mass density in the rotation plane into account.

Assuming a value GL ≈ 6.4 x 10-12 [m3 kg-1 s-2], calculate the additional linear gravitational acceleration with formula (16).

Correct the computed linear gravitational acceleration at time t with the ratio current radius of the universe / radius at time t.

Add the Newtonian gravitational acceleration to the linear gravitational acceleration and compute the rotation velocity with formula (12).

It works at all radii, without the need for a distinction between two regimes, and without an interpolation scheme between the two regimes, as with MOND.

6.5. Fifth Prediction

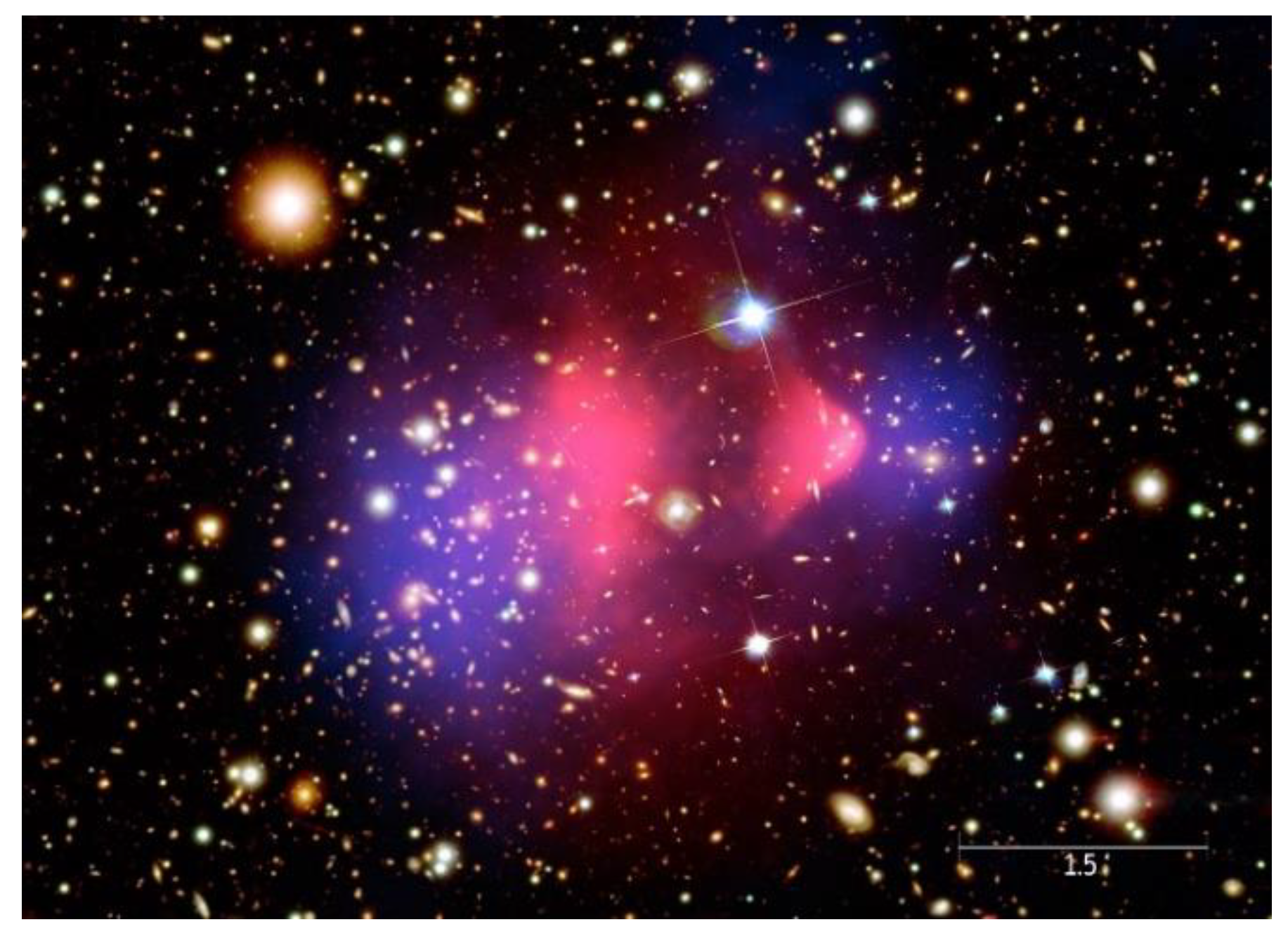

A fifth prediction is that the dark matter is

undetectable in any way, since it cannot interact with visible matter, except by gravity, which deforms space and time. The effect of this non-interacting is directly visible in the Bullet cluster [

13]. In the plot down here,

Figure 10, depicting the Bullet Cluster, the calculated distribution of dark matter is coloured blue. It is shown the dark matter acts like the heaviest visible matter and just flows through the other galaxy, because of its momentum, whereas the ionized HI gas cloud, coloured pink, interacts and stays behind. It may be expected that when the halos are recomputed based upon the linear gravity proposal, this behaviour will still be visible in the Bullet Cluster.

Now, according to the hypothesis in hand, there is a fundamental reason dark matter is undetectable. That is

orthogonality, see Griffiths & Schroeter [

16] (p. 98 and 151) in terms of quantum mechanics. It follows from the definition of a superposition state, namely as a linear combination of

independent quantum states, i.e. orthogonal states. They are per definition not accessible to each other. For the superposition of 3-dimensional universes in a 4-dimensioanl space with two overlapping dimensions, the meaning of this is evident, because one of the dimensions is orthogonal to that of the other universes. But it is in all cases necessary to maintain a superposed state. For instance, Zeilinger [

35] states about the double-slit experiment: “The superposition of amplitudes .. is only valid if there is no way to know, even in principle, which path the particle took. It is important to realize that this does not imply that an observer actually takes note of what happens. It is sufficient to destroy the interference pattern, if the path information is accessible in principle from the experiment or even if it is dispersed in the environment and beyond any technical possibility to be recovered, but in principle still ‘‘out there.’’ The absence of any such information is

the essential criterion for quantum interference to appear”.

That is why we can never perform any measurement on the properties of dark matter. This information must be and remain absent for the superposition at the earliest stage of the Big Bang to have been possible at all. Otherwise, the quantum states are not independent anymore. But gravity differs greatly from the other forces and interactions, deforming space and time. the question, however, may be asked whether gravity itself, would make a sort of information exchange between the universes possible, for instance like the manipulation of the seconds hand of the wristwatch in the said motion picture Interstellar at 2 h: 21 m. Fortunately, our entire history can never be transmitted, i.e. it cannot even be known in its entirety.

6.6. Sixth Prediction

As mentioned in chapter 5, Han [

26] shows that the Milky Way galactic stellar halo is tilted with respect to the disk plane, suggesting that at least some component of the dark matter halo may also be tilted, see

Figure 11 in the sequel. The origin of this misalignment of the dark halo, of approximately 25°, can be explained by the linear gravity hypothesis in the paper in hand, since the orientation of the two dimensions of another superposition state overlapping with ours, can deviate from the orientation of a galaxy and can be anisotropic if the amounts of matter in overlapping galaxies differ. The sixth prediction is that the orientations of the halos of different galaxies will reveal a deep underlying structure in the universe, i.e. will display the direction of the pair of two dimensions overlapping with our universe. In other words, the orientations of the halos will, when compared with each other on a large scale, display the underlying coordinate system, of sorts, of the universe.

7. General Relativity and TeVeS Theory

Bekenstein [

4] provided a theory, T

eV

eS, in which MOND is reformulated in terms of GR. T

eV

eS was developed on the basis of the action principle, with two additional actions and a free function added to the geometric action of GR and varying those actions with respect to the metric and to the scalar and vector fields added by Bekenstein in those actions. This yields a differential equation for the free function

F, which then is shown to reproduce MOND. The differential equation of Bekenstein is used here to show the theory of linear gravity as well is a valid solution of this. And it is shown that the mentioned decay with time inevitably follows from these equations.

His work resulted in a general theory: TeVeS, so as to provide for a relativistic formulation of gravity without the assumption of dark matter. Then Bekenstein shows that MOND is well incorporated in TeVeS, so that it is a relativistic formulation of MOND. He applies different metrics in his actions for different applications and solves them for those situations, like for instance non-spherical symmetric cases like galaxies and to study the evolution in time using the Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) metric in his added actions. In this chapter it will be shown that this framework as well allows for the hypothesis of linear gravity to be entered into TeVeS, so the mathematics of TeVeS as well can incorporate linear gravity perfectly. And hence that linear gravity yields a consistent relativistic formulation.

As with MOND, in TeVeS a function µ is introduced, that modifies the total gravitational acceleration to obtain the Newtonian acceleration. It thus acts on the sum of all contributions to the total gravitational acceleration and not on the contributions from different masses in a galaxy separately. The application of TeVeS in this chapter will, however, do so. Like in chapter 6.3 formulas (13) and (14), the contributions all masses in a galaxy have to be summed up. Here this will be done after modification with µ for each contribution separately.

7.1. Introducing and Applying TeVeS

Conservation of momentum is not satisfied by MOND, but is automatically satisfied in physical theories that are derived using an action principle [

4]. To that end, in AQUAL, his starting point, the following Lagrangian was formulated under the assumption of and additional real scalar field ψ:

Where f is some function, not known a priori. The same recipe is followed in TeVeS: define and additional scalar field as well as a free function, the exact form of which at a later stage follows from constraints that come with solving the linearized GR equations. MOND formula (5) then follows from (21) under spherical symmetry and static conditions. But, as mentioned in chapter 3, AQUAL failed to describe light deflection.

T

eV

eS [

4] is based on three dynamical gravitational fields: and Einstein metric

gµυ with a well-defined inverse

gµυ and a time-like 4-vector field Џ

µ as well as a dynamic scalar field

ϕ and a non-dynamical scalar field

σ. The physical metric is obtained by stretching the Einstein metric in space-time directions orthogonal to Џ

α = gαβ Џ

β by a factor e

-2ϕ while shrinking it by the same factor in the direction parallel to it. As becomes clear from [

4] (p. 21 formulas (52), (53) and (58)) the scalar field

ϕ is to be interpreted as the additional gravitational potential. So, in T

eV

eS this

ϕ is added to the Newtonian potential.

Then the total action resulting from the scalar fields contains a geometric part just as in GR, the Einstein-Hilbert action

Sg, the matter action

Sm and two extra actions,

Ss and

Sv, including two positive parameters

k (dimensionless) and

l (a length scale) and a free dimensionless function

F, which is related to an additional gravitational potential [

4] (p. 8). The shape and behaviour of

F must be consistent with the theory and yield a valid solution of the equations, so effectively it is not entirely free. In the hypothesis in hand, it directly will follow from the acceleration being the sum of two components, so from formula (8). The extra action for the pair of scalar fields is as follows [

4]:

where h

αβ = g

αβ - Џ

α Џ

β. The extra term for the action of the vector Џ

α has the form:

The square brackets around pairs of indices indicate anti-symmetrisation in that pair. The factor λ is a spacetime dependent Lagrange multiplier to enforce normalisation. This action of the vector field by Bekenstein introduces the parameter K, but does not contain F, so is left unaltered by the hypothesis in hand and therefore it is not further discussed here. But the value of the dimensionless parameter K was determined by fitting to cosmological effects, with µ > 1, which is not necessary anymore in the hypothesis of linear gravity. So it is free to be determined again, which might be a favourable to solve some reported problems with TeVeS, see the discussion in the sequel.

Then, varying those three actions with respect to the metric and to the scalar and vector fields added by Bekenstein in those actions gives a general solution for spherically symmetric situations. Variation of σ in

Ss gives the relation between σ and ϕ

,α and

F, where per definition [

4]

F’ = dF(µ)/dµ:

Now [

4] defines the function

µ(y) such that equation (24) takes the following shape:

so that

.

This differential equation can be solved when the function µ(y) is specified, so as to yield the function F(µ). If µ(y) yields a solution for F(µ) and the solution shows proper behaviour, i.e. consistent with the theory, then the theory incorporates relativity consistently. This now is done for the hypothesis of linear gravity.

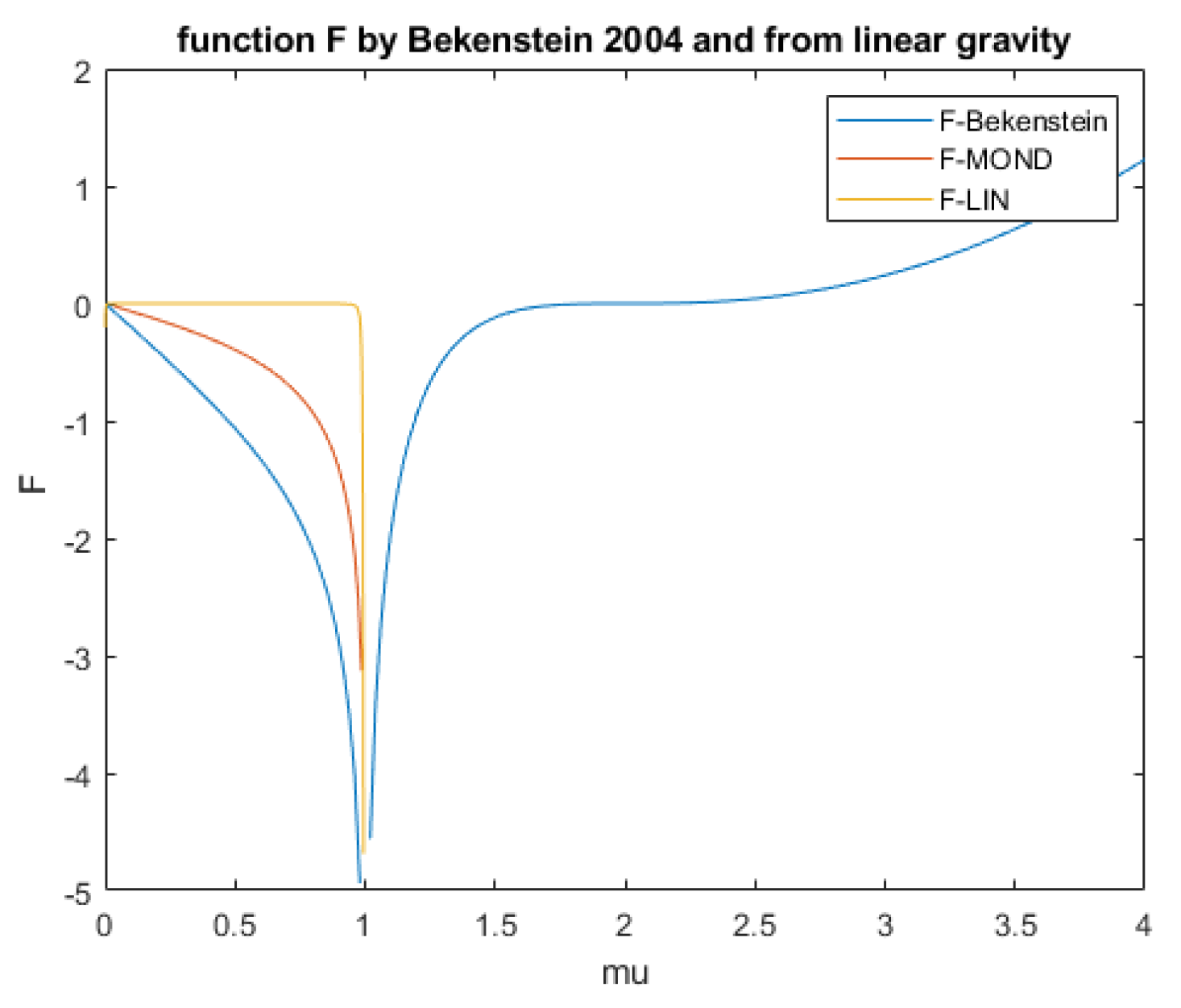

Bekenstein has firstly derived his free function

F(µ) for relativity in quasistatic systems. He does not calculate it for MOND separately, but explores the behaviour in different limits, for example the non-relativistic limit, to show it just reproduces MOND in those cases. This, for example leads to an equation [

4] (p. 13 formula (58)) that closely resembles equation (7), so the potential being the sum of Newtonian and an additional potential. This, again, hints at the strong relationship between MOND, T

eV

eS and linear gravity.

As a starting point to determine

F(µ) for linear gravity, so as to predict gravitational acceleration from a given mass distribution including relativistic effects, inverting formula (9) yields:

This follows directly from the theory of linear gravity as outlined in chapters 4 and 6 and it can be used instead of Bekenstein’s free function

y(µ) from [

4] (Bekenstein’s formula (50) to predict gravitational acceleration from a given mass distribution. Bekenstein states that there is great freedom in choosing

y(µ) and hence

F(µ), but here it directly follows from the theory that the gravitational acceleration in a galaxy is the sum of two contributions, see chapter 4, formula’s (6) to (9).

Figure 12 shows it gives a somewhat steeper increase towards

µ = 1, but the trend as well as the sign and magnitude are of the same order as MOND and T

eV

eS. And no values for

µ > 1 to account for cosmological effects are needed now, since dark matter is part of this hypothesis, opposed to MOND and T

eV

eS. The most left part, with

µ << 1 is the deep MOND-regime.

µ = 1 is the case where Newtonian gravity fully dominates.

However,

c is not a constant but depends on the mass

mi in a certain position in the galaxy now as discussed in chapter 6.3 formula (20). But, on using a linearised metric as in Bekenstein [

4] (p. 18, section B) the sum is a valid solution when each contribution to the sum is a valid solution.

As explained in Schutz [

36] (p. 200) this is only valid for low gravitational acceleration where space-time is nearly flat, but comparing Milgrom’s constant with the Earth’s gravitational acceleration in one glance shows that this is the case in galaxies. And Bekenstein as well does it in his section B to study systems wit no particular symmetry.

For stronger fields, the accelerations due to the different masses in a galaxy should be added to each other using the acceleration addition formula for GR, based upon the Lorentz factor, to obtain a relativistic solution for the sum.

So, in galaxies, y may be treated the sum of many contributions from all mass in the galaxy, each with their own value of c, i.e conforming to formula (20). ci. And in galaxies with a bulge, in line with chapter 6, the bulge and the disk can be treated separately and the results added to yield a solution for the galaxy with bulge as a whole. The same applies to all different masses in a galaxy. So, if at one radial position R for one contribution from mass at another position X, agreement is proved, it is valid for the total acceleration g at a point.

Integration of (25) with use of (26), with

c* = c4/am2, gives:

k1 is an integration constant, which can be chosen small compared to c* such that the function F(µ) at small values of µ, i.e. in the outer regions of the galaxy, is not dominated by the most right quadratic term in (27) but continues to converge steadily when µ, goes to zero. µ is limited to the range [0-1) in galaxies and when µ = 1 Newtonian acceleration is the only contribution to the acceleration, so in the centre of the galaxy and y would go to infinity. Bekenstein applies his function F to values of µ > 1 for cosmology and gravitational lensing, but that is not necessary if dark matter is used to explain those effects.

Again, as

Figure 13 shows, the function

F by linear gravity towards

µ = 1 is steeper, but the trend and the sign are as well as the orders of magnitude are the same. The same applies to the function derived from MOND, what Bekenstein did not do, but is done here in the same way equation (27) was derived. As can be seen in

Figure 9 and in chapter 6.4 as well as Annex 3, the impact of the differences in

F on the predicted rotation velocities are small. And again, no values for

µ > 1 to account for cosmological effects are needed here.

This latter restriction, valid since dark matter is not excluded here, as well cures some of the reported problems of T

eV

eS like the incompatibility with the value of the quantity

Eg at cosmological scales reported by Zhang [

37]. Since linear gravity is an explanation of dark matter and not designed to do without it, it unlike T

eV

eS, does not have to account for gravitational lensing effects and cosmological dark matter. The function

µ introduced in chapter 4 and used up here now, like in MOND, only is applied in the range

µ =[0-1), so with a positive contribution of dark matter to gravity, as it happens in galaxies. And since it is only applied for very weak fields, determining the motions of stars and gas in galaxies, the T

eV

eS problem with instability in stars reported by Seifert [

38] does not apply here either.

7.2. Evolution in Time

Bekenstein [

4] also explores the dynamic, time-dependent, behaviour in his section E for, among other, the matter ara in the evolution of our universe. Please note, the elaboration in the sequel fully applies to his theory and MOND as well, since in the outer regions of galaxies, i.e. the deep MOND regime, the theories behave the same with respect to the function

y(

µ) and

F(

µ). And they are still free in Bekenstein’s scalar equation [

4] (Bekenstein’s equation (37)) that is applied down here again.

Recall that

µ is the ratio of Newtonian acceleration over total acceleration. Hence it is a decreasing function of the radial position in a galaxy and a supposed decay of the additional gravity by dark matter would make it grow towards unity. To explore this, Bekenstein uses the Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) cosmology [

4] (p. 10) in which

a(t) is the scale factor of the expanding universe.

Bekenstein uses (28) to a obtain a modified, now time-dependent scalar equation, (31) in the sequel, as well as a modified Friedmann equation (29) in TeVeS. Then he uses a combination of both to study the resulting evolution of F in time.

His modified Friedmann equation, obtained from variation of his additional action

S with respect to this metric, with

ρ being the proper energy density and

p the pressure and

ϕ the additional gravitational potential caused by the added scalar field (

ϕ > 0), is:

Please note, that all variables are scaled such way by Bekenstein that

ϕ << 1 and that is it dimensionless [

4] (pp. 8, 12 and 20). Later on he will argue that the left term of the right-hand-side in (29) dominates over the right term, which he then ignores.

Now Bekentein wants to find a relation between the time derivatives of

a(t) and

ϕ(t) by combining this, as said, with a time dependent scalar equation. Applying his scalar equation (Bekenstein’s formula (37)) to the FRW metric yields Bekenstein’s formula (45) copied down here [

4] (p. 10):

Since the function F(µ) was part of the definitions of Bekenstein’s additional action Ss and hence of formula (24), the function µ reappears here as part of a differential equation, but, as said, with F still free.

In the matter era

and

ρ varies as

a-3 [

4] (p. 21). Then integrating equation (30) from the start of this era gives:

The time

tr is the time at the end of the radiation era and the start of the matter era, where

a = ar. Now Bekenstein explicitly evaluated this integral from

tr to

t to let (31) become the following equation:

Now equation (29) is used to express the left term in the right-hand-side in as a function of .

After that, Bekenstein argues that after the start of the matter era, after the first e-folding of a, the first term of the right-hand side becomes dominant, so over most of the matter era up to the present. Ignoring the second term in the right hand makes (32) a simple differential equation. This is elaborated down here following Bekenstein.

Bekenstein [