Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation and Curing of Rubber Compounds

2.2.2. Determination of Curing Characteristics

2.2.3. Determination of Cross-Link Density

2.2.4. Rheological Measurements

2.2.5. Investigation of Physical-Mechanical Characteristics

2.2.6. Microscopic Analysis

2.2.7. Determination of Dynamical-Mechanical Properties

3. Results and Discussion

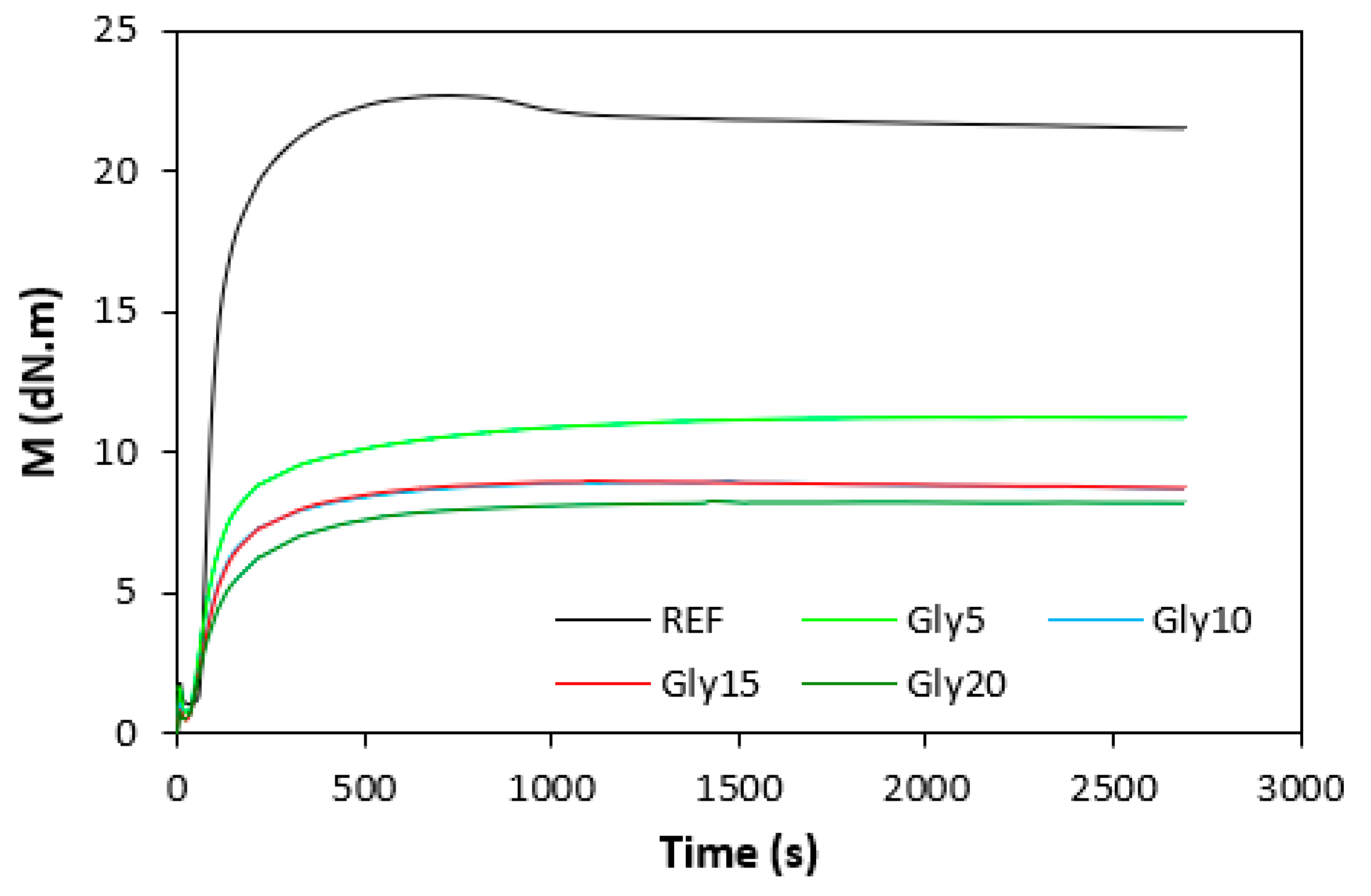

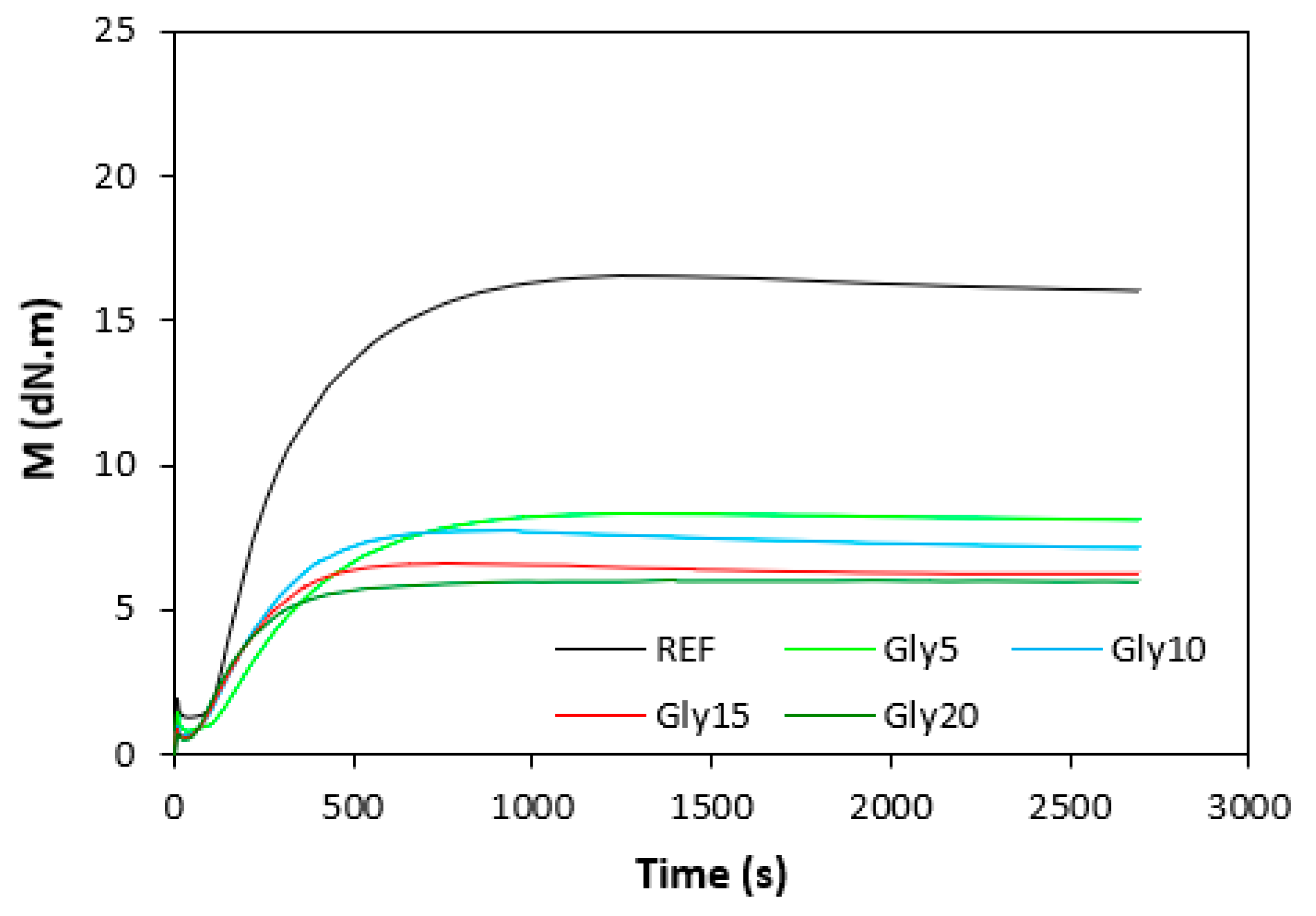

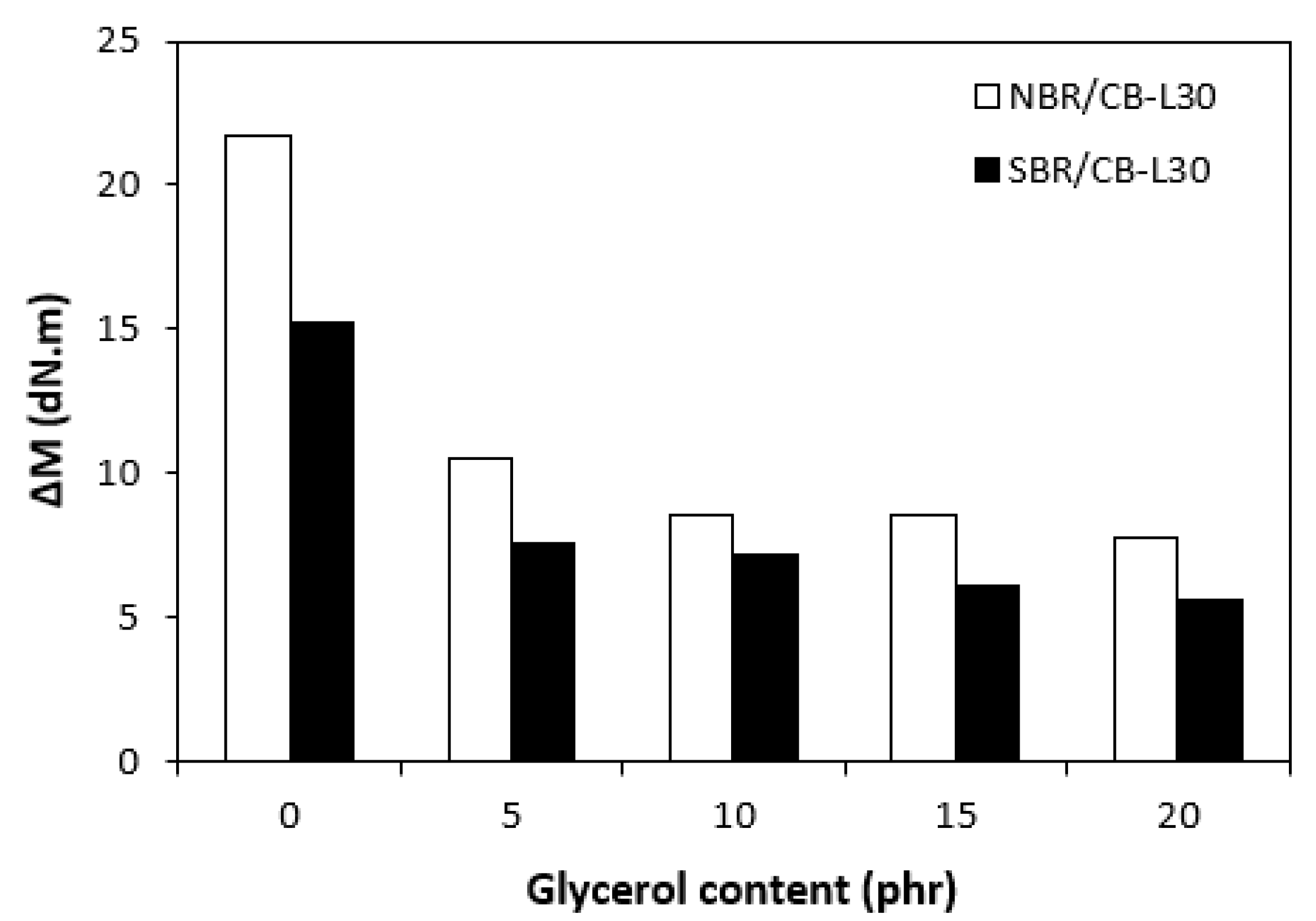

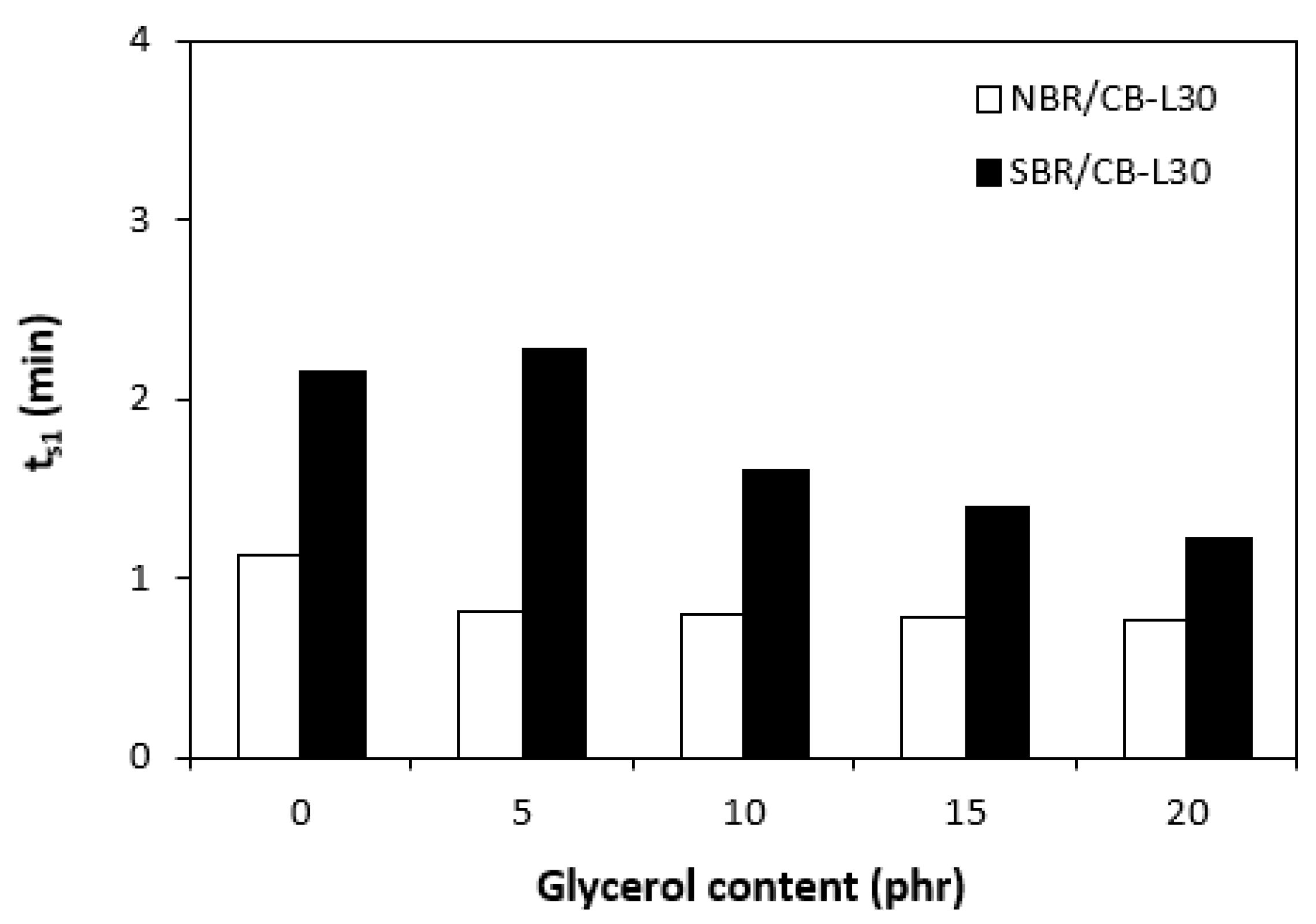

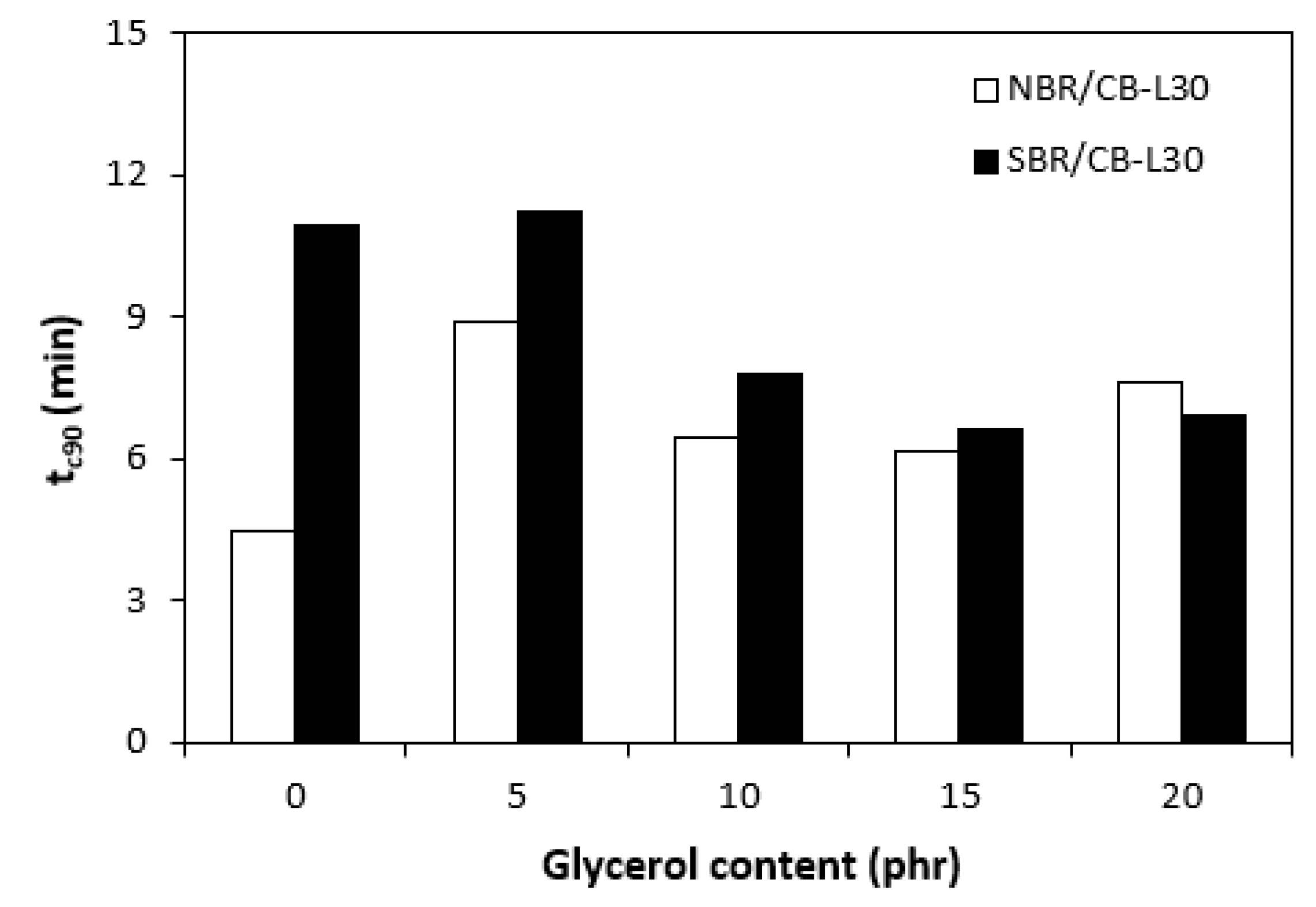

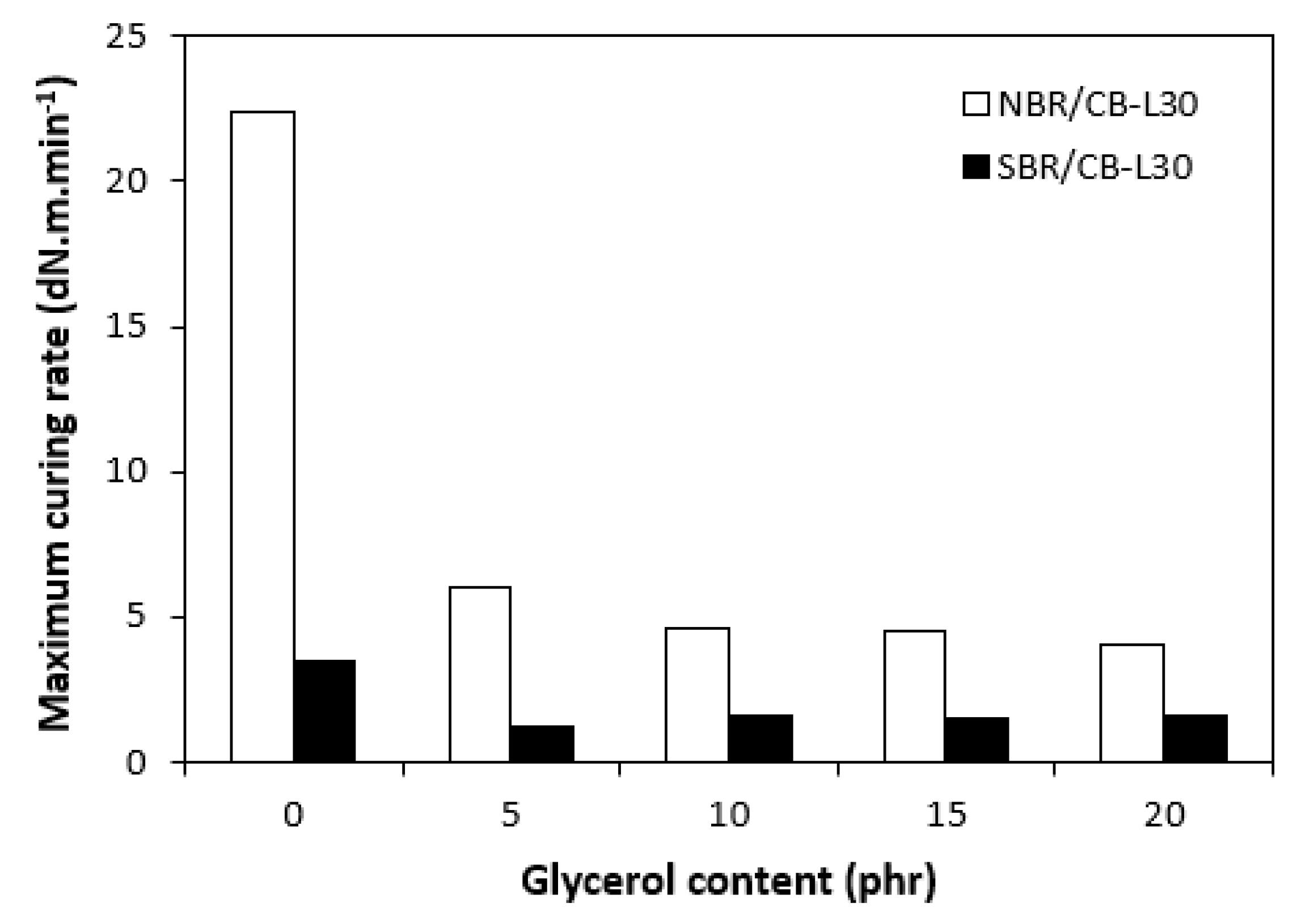

3.1. Curing Process and Cross-Link Density

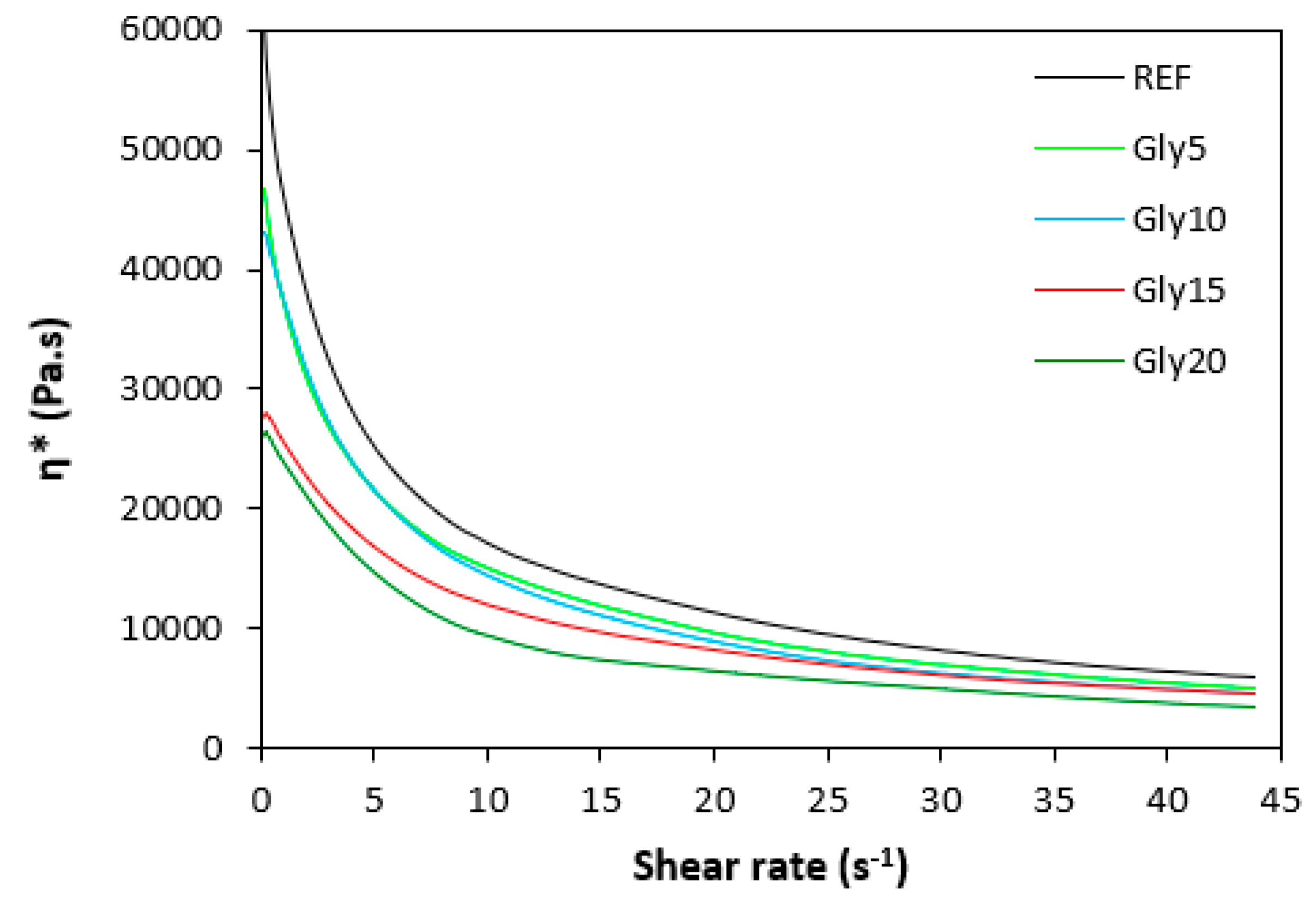

3.2. Rheological Study

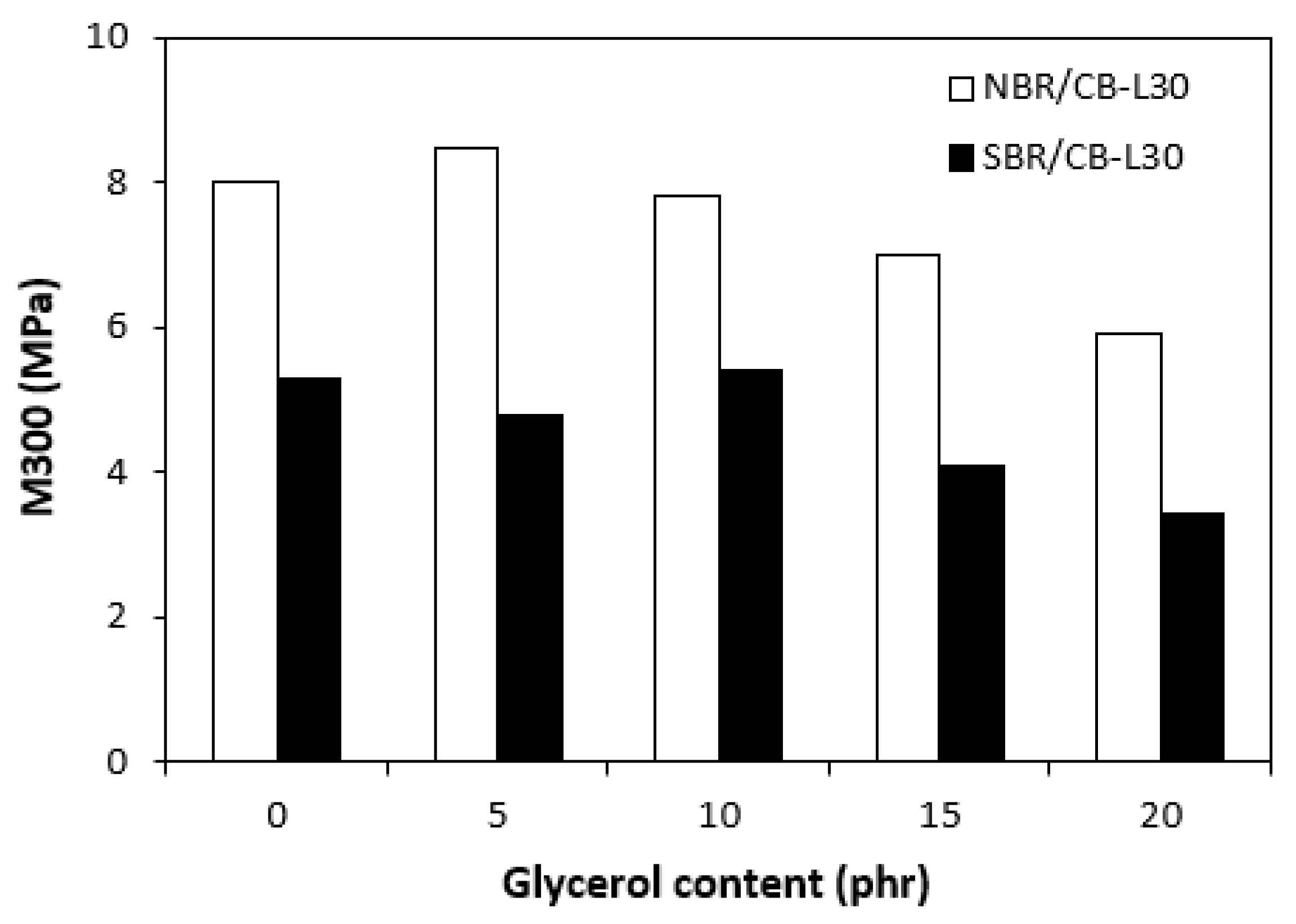

3.3. Physical-Mechanical Properties

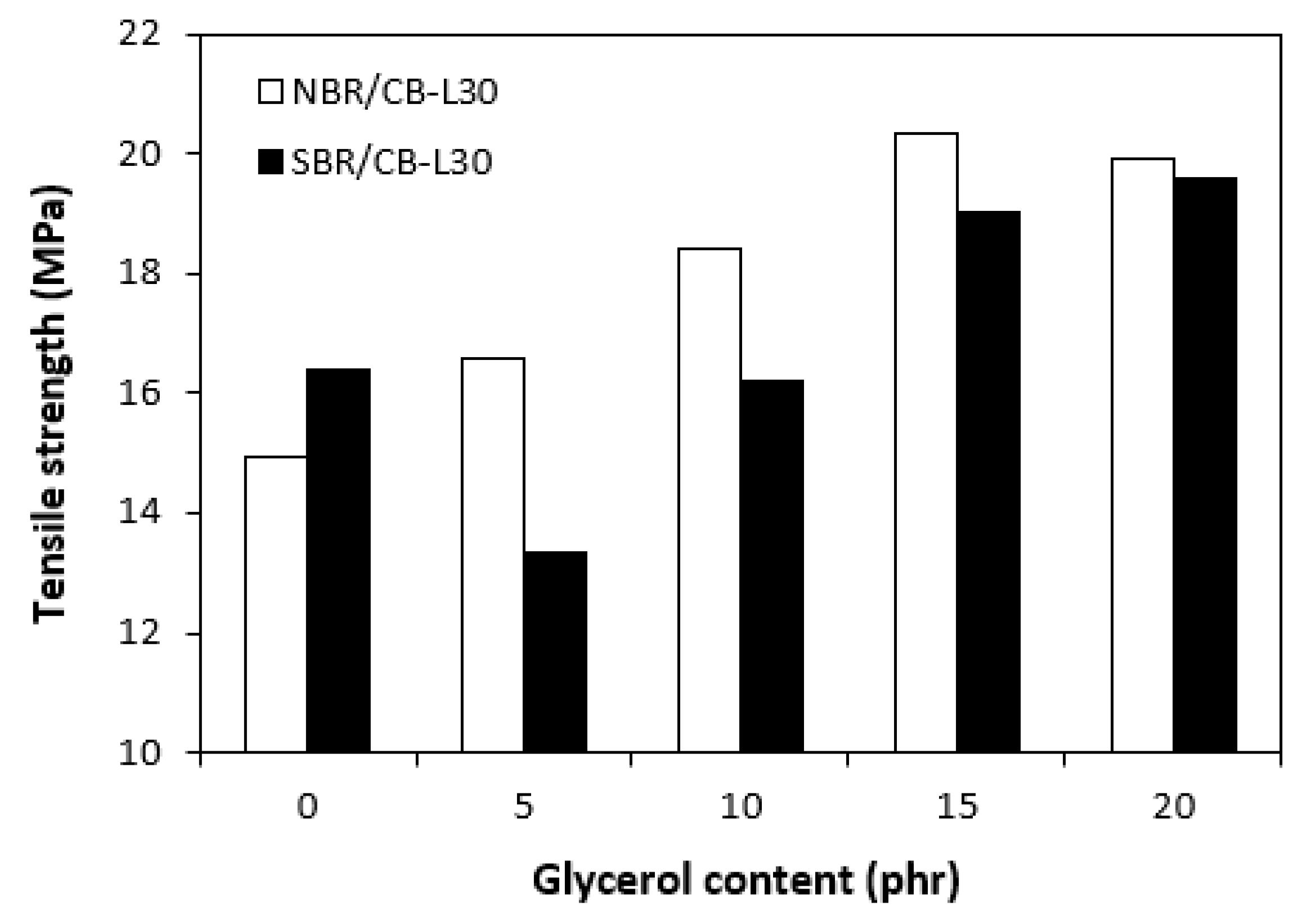

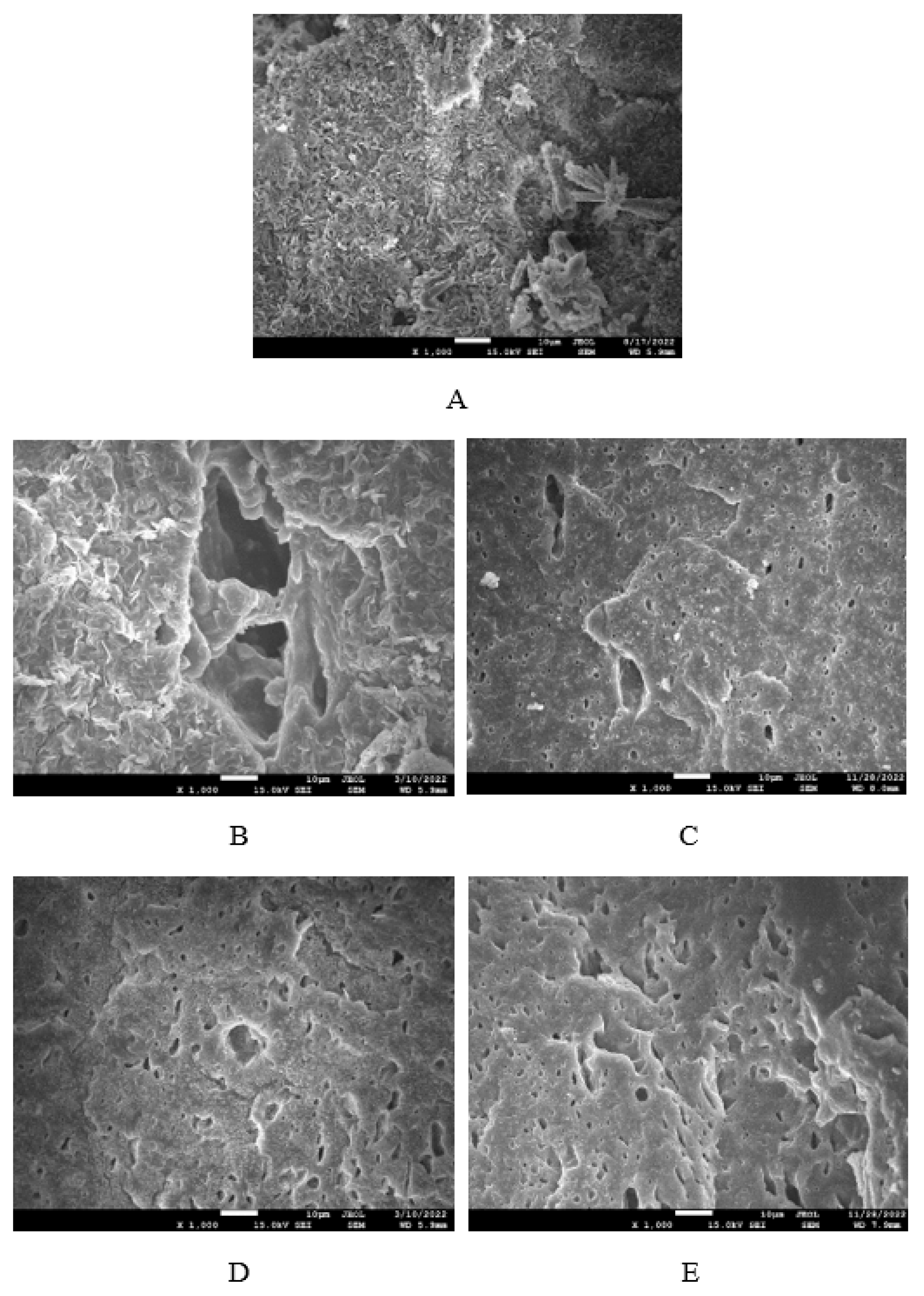

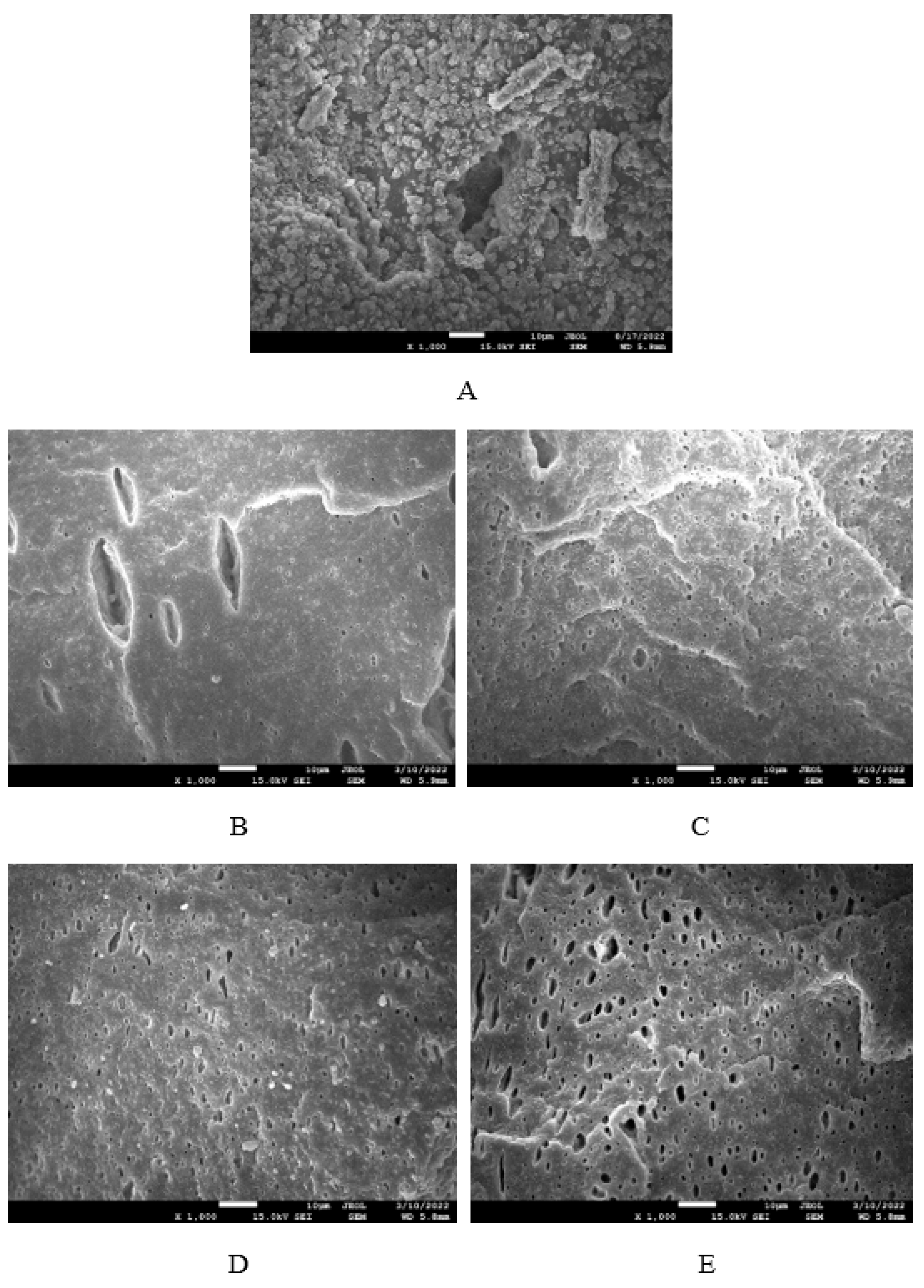

3.4. Morphology

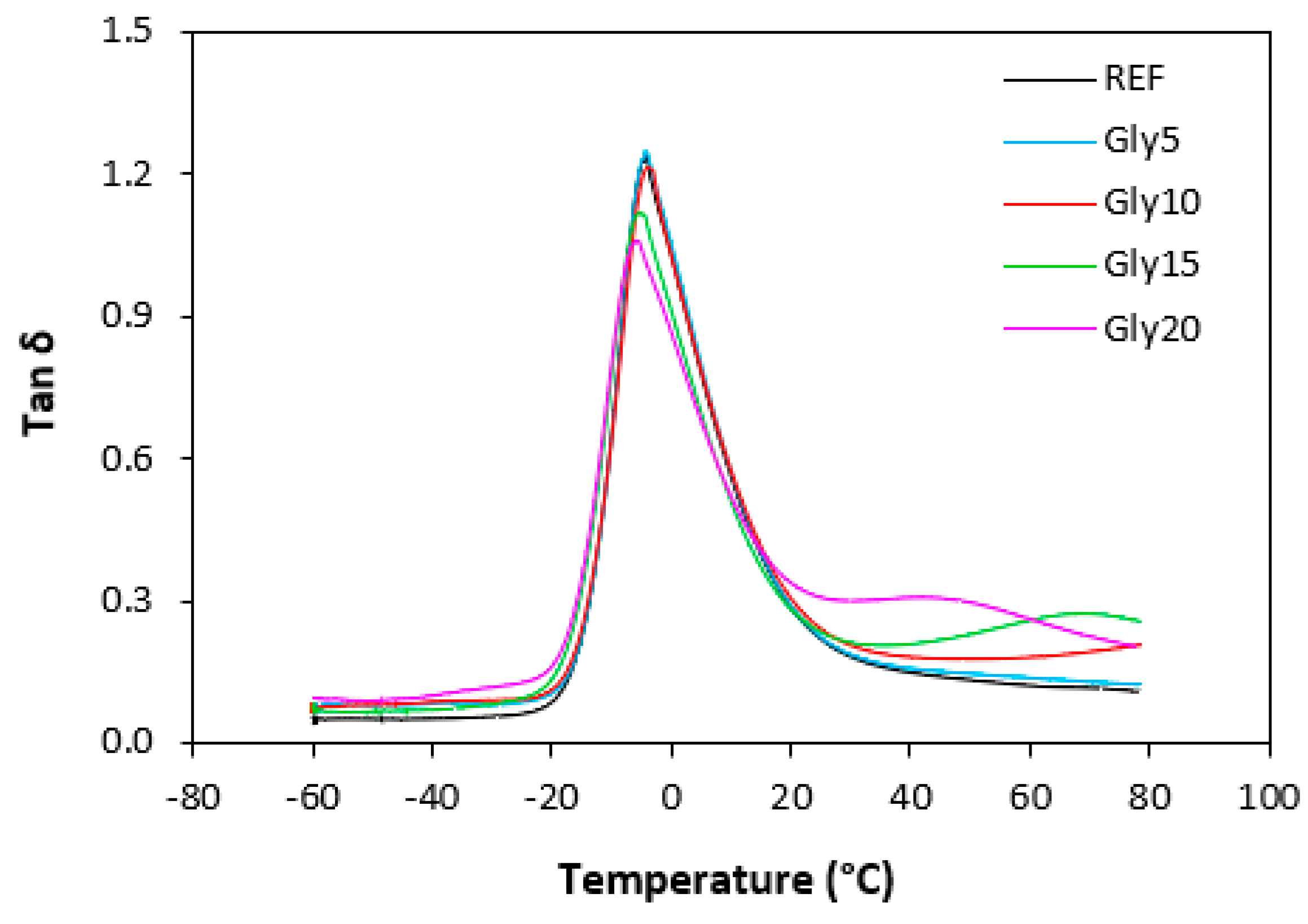

3.5. Dynamic-Mechanical Properties

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- European Green Deal. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (2019).

- Jacobs, B.; Yao, Y.; Van Nieuwenhove, I.; Sharma, D.; Graulus, G.J.; Bernaerts, K.; Verberckmoes, A. Sustainable lignin modifications and processing methods: green chemistry as the way forward. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 2042–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.K.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Krishnasamy, S.; Sabura Begum, P.M.; Nandi, D.; Siengchin, S.; Jacob George, J.; Hameed, N.; Salim, N.V.; Sienkiewicz, N. A comprehensive review on cellulose, chitin, and starch as fillers in natural rubber biocomposites. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2021, 2, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, J.; Sequerth, O.; Pilla, S. Green chemistry design in polymers derived from lignin: review and perspective. Prog Polym Sci. 2021, 113, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, S.; Rennert, M.; Tesfaye, T.; Grosmann, L.; Kuehnert, I.; Smolka, N.; Nase, M. Thermal, morphological, and structural characterization of starch-based bio-polymers for melt spinnability. e-Polymers. 2024, 24, 20240025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, K.; Tsujii, Y. Visualization of fibrillated cellulose in polymer composites using a fluorescent-labeled polymer dispersant. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2023, 11, 6332–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. Multilayer two-dimensional lignin/ZnO composites with excellent anti-UV aging properties for polymer films. Green Chem Eng. 2022, 3, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chung, H. Convenient cross-linking control of lignin-based polymers influencing structure–property relationships. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2023, 11, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridho, M.R.; Agustiany, E.A.; Rahmi Dn, M. Lignin as green filler in polymer composites: development methods, characteristics, and potential applications. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2022, Article ID 1363481, 33p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, T.R.; Bresolin, D.; de Oliveira, D.; Sayer, C.; de Araújo, P.H.P.; de Oliveira, J.V. Conventional lignin functionalization for polyurethane applications and a future vision in the use of enzymes as an alternative method. Eur Polym J. 2023, 188, 111934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksson, G.; Germgård, U.; Lindström, M.E. A review on chemical mechanisms of kraft pulping. Nord Pulp Paper Res J. 2024, 39, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, F.; Bischof, S.; Mayr, S.; Gritsch, S.; Bartolome, M.J.; Schwaiger, N.; Guebitz, G.M.; Weiss, R. The biomodified lignin platform: A review. Polymers. 2023, 15, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, O.; Kim, K.H. Lignin to materials: A focused review on recent novel lignin applications. Appl Sci. 2020, 10, 4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, P.; Leschinsky, M.; Seidel-Morgenstern, A.; Lorenz, H. Continuous separation of lignin from organosolv pulping liquors: combined lignin particle formation and solvent recovery. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2019, 58, 3797–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadix-Montero, S.; Sankar, M. Review on catalytic cleavage of C–C inter-unit linkages in lignin model compounds: towards lignin depolymerisation. Top Catal. 2018, 61, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, C.; Baican, M. Lignins as promising renewable biopolymers and bioactive compounds for high-performance materials. Polymers. 2023, 15, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.; Salaghi, A.; Fatehi, P.; Mekonnen, T.H. Valorization of lignin for advanced material applications: a review. RSC Sustainability. 2024, 2, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Ferra, J.; Paiva, N.; Martins, J.; Carvalho, L.H.; Magalhães, F.D. Lignosulphonates as an alternative to non-renewable binders in wood-based materials. Polymers. 2021, 13, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libretti, C.; Correa, L.S.; Meier, M.A.R. From waste to resource: advancements in sustainable lignin modification. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, K.; Szymona, K.; McDonald, A.G.; Mamiński, M. Characterization of thermal and mechanical properties of lignosulfonate- and hydrolyzed lignosulfonate-based polyurethane foams. BioRes. 2016, 11, 7355–7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiarto, S.; Leow, Y.; Li Tan, C.; Wang, G.; Kai, D. How far is lignin from being a biomedical material? Bioact Mater. 2022, 8, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Lin, Q.; Fang, L. Study on the mechanical properties of loess improved by lignosulfonate and its mechanism analysis and prospects. Appl Sci. 2022, 12, 9843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.; Bischof, S.; Rivas, B.L.; Weber, H.; Mahler, A.K.; Kozich, M.; Guebitz, G.M.; Nyanhongo, G.S. Biosynthesis of highly flexible lignosulfonate–starch based materials. Eur Polym J. 2023, 198, 112392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Liang, M.; Ma, X.; Luo, Y.; He, M.; Gu, X.; Gu, Q.; Hussain, I.; Luo, Z. Highly efficient, environmentally friendly lignin-based flame retardant used in epoxy resin. ACS Omega. 2020, 5, 32084–32093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komisarz, K.; Majka, T.M.; Pielichowski, K. Chemical transformation of lignosulfonates to lignosulfonamides with improved thermal characteristics. Fibers. 2022, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedrzejczyk, M.A.; den Bosch, S.V.; Van Aelst, J.; Van Aelst, K.; Kouris, P.D.; Moalin, M.; Haenen, G.R.M.M.; Boot, M.D.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Lagrain, B.; Sels, B.F.; Bernaerts, K.V. Lignin-based additives for improved thermo-oxidative stability of biolubricants. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2021, 9, 12548–12559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.Z.; Jiang, L.; Hu, X.Q.; Zhang, M.H.; Zhang, X. Lignosulfonate as reinforcement in polyvinyl alcohol film: Mechanical properties and interaction analysis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015, 83, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhao, X.; Han, X.; Du, P.; Su, Y.; Chen, C. Effect of thermal oxygen aging mode on rheological properties and compatibility of lignin-modified asphalt binder by dynamic shear rheometer. Polymers. 2022, 14, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mili, M.; Hasmi, S.A.R.; Ather, M.; Hada, V.; Markandeya, N.; Kamble, S.; Mohapatra, M.; Rathore, S.K.S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Verma, S. Novel lignin as natural-biodegradable binder for various sectors-A review. J Appl Polym Sci. 2022, 139, e51951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, K.; Jana, S.C. Surface modification of lignosulfonates for reinforcement of styrene–butadiene rubber compounds. J Appl Polym Sci. 2014, 131, 40123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.; Gupta, A.; Mekonnen, T.H. Hydrophobic modification of lignin for rubber composites. Ind Crops Prod. 2021, 174, 114189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Aini, N.A.; Othman, N.; Hussin, M.H.; Sahakaro, K.; Hayeemasae, N. Hydroxymethylation-modified lignin and its effectiveness as a filler in rubber composites. Processes. 2019, 7, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, J.; Kemppainen, N.; Sarlin, E. Lignin dispersion in polybutadiene rubber (BR) with different mixing parameters. Prog Rubber Plast Recycl Technol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ferruti, F.; Carnevale, M.; Giannini, L.; Guerra, S.; Tadiello, L.; Orlandi, M.; Zoia, L. Mechanochemical methacrylation of lignin for biobased reinforcing filler in rubber compounds. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2024, 12, 14028–14037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Xiao, H.; Shen, T.; Tan, Z.; Zhuang, W.; Xi, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhu, C.; Ying, H. Design of a lignin-based versatile bioreinforcement for high-performance natural rubber composites. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2022, 10, 8031–8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atifi, S.; Miao, C.; Hamad, W.Y. Surface modification of lignin for applications in polypropylene blends. J Appl Polym Sci. 2017, 134, 45103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komisarz, K.; Majka, T.M.; Pielichowski, K. Chemical and physical modification of lignin for green polymeric composite materials. Materials. 2023, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hait, S.; Kumar, L.; Ijaradar, J.; Ghosh, A.K.; De, D.; Chanda, J.; Ghosh, P.; Gupta, S.D.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Wiesner, S.; Heinrich, G.; Das, A. Unlocking the potential of lignin: Towards a sustainable solution for tire rubber compound reinforcement. J Clean Prod. 2024, 470, 143274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibi, A.; Jubinville, D.; Chen, G.; Mekonnen, T.H. In-situ surface grafting of lignin onto an epoxidized natural rubber matrix: A masterbatch filler for reinforcing rubber composites. React Funct Polym. 2024, 197, 105856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, D.; Pukánszky, B. Polymer/lignin blends: Interactions, properties, applications. Eur Polym J. 2017, 93, 618–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruželák, J.; Hložeková, K.; Kvasničáková, A.; Džuganová, M.; Chodák, I.; Hudec, I. Application of plasticizer glycerol in lignosulfonate-filled rubber compounds based on SBR and NBR. Materials. 2023, 16, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruželák, J.; Hložeková, K.; Kvasničáková, A.; Džuganová, M.; Hronkovič, J.; Preťo, J.; Hudec, I. Calcium-lignosulfonate-filled rubber compounds based on NBR with enhanced physical–mechanical characteristics. Polymers. 2022, 14, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, G. Swelling of filler-reinforced vulcanizates. J Appl Polym Sci, 1963, 7, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Kumar, V.; Potiyaraj, P.; Lee, D.J.; Choi, J. Mutual dispersion of graphite–silica binary fillers and its effects on curing, mechanical, and aging properties of natural rubber composites. Polym Bull. 2022, 79, 2707–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansarifar, A. Highly Efficient Methods for Sulfur Vulcanization Techniques, Results and Implications. Balboa Press, United Kongdom, 2022.

- Maciejewska, M.; Krzywania-Kaliszewska, A.; Zaborski, M. Ionic liquids applied to improve the dispersion of calcium oxide nanoparticles in the hydrogenated acrylonitrile-butadiene elastomer. Am J Mater Sci. 2013, 3, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kruželák, J.; Sýkora, R.; Hudec, I. Vulcanization of rubber compounds with peroxide curing systems. Rubber Chem Technol. 2017, 90, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Glycerol (phr) | G' (MPa) (-20 °C) |

G' (MPa) (0 °C) |

G' (MPa) (20 °C) |

G' (MPa) (60 °C) |

G" (MPa) (-20 °C) |

G" (MPa) (0 °C) |

G" (MPa) (20 °C) |

G" (MPa) (60 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3430 | 46.64 | 16.64 | 10.75 | 296 | 47.49 | 4.7 | 1.29 |

| 5 | 3227 | 45.62 | 15.68 | 9.83 | 343 | 47.37 | 4.47 | 1.34 |

| 10 | 3988 | 48.01 | 16.65 | 9.41 | 444 | 49.68 | 5.09 | 1.70 |

| 15 | 3137 | 43.84 | 16.59 | 7.66 | 434 | 39.86 | 4.71 | 2.00 |

| 20 | 2410 | 41.42 | 14.52 | 4.94 | 383 | 35.97 | 4.89 | 1.29 |

| Glycerol (phr) | Tg (°C) | tan δ (-20 °C) |

tan δ (0 °C) |

tan δ (20 °C) |

tan δ (60 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -4.4 | 0.09 | 1.02 | 0.28 | 0.12 |

| 5 | -4.4 | 0.11 | 1.04 | 0.29 | 0.14 |

| 10 | -3.8 | 0.11 | 1.03 | 0.31 | 0.18 |

| 15 | -5.5 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 0.28 | 0.26 |

| 20 | -5.6 | 0.16 | 0.87 | 0.34 | 0.26 |

| Glycerol (phr) | G' (MPa) (-20 °C) |

G' (MPa) (0 °C) |

G' (MPa) (20 °C) |

G' (MPa) (60 °C) |

G" (MPa) (-20 °C) |

G" (MPa) (0 °C) |

G" (MPa) (20 °C) |

G" (MPa) (60 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 36.57 | 13.75 | 10.63 | 8.18 | 37.05 | 3.81 | 1.63 | 0.96 |

| 5 | 42.53 | 15.91 | 12.13 | 8.79 | 41.01 | 4.47 | 2.01 | 1.22 |

| 10 | 44.61 | 17.31 | 12.85 | 8.55 | 40.09 | 4.75 | 2.21 | 1.36 |

| 15 | 45.62 | 18.29 | 13.31 | 7.2 | 39.09 | 4.94 | 2.42 | 1.74 |

| 20 | 43.67 | 17.19 | 11.67 | 4.62 | 37.45 | 4.98 | 2.48 | 1.31 |

| Glycerol (phr) |

Tg (°C) | tan δ (-20 °C) |

tan δ (0 °C) |

tan δ (20 °C) |

tan δ (60 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -26.3 | 1.01 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| 5 | -25.1 | 0.96 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| 10 | -26.3 | 0.90 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| 15 | -24.9 | 0.86 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.24 |

| 20 | -26.3 | 0.86 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).