Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

17 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Liver fibrosis, a progressive condition often linked to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), lacks specific biomarkers to accurately gauge disease progression and therapeutic response. Emerging research suggests that microRNAs, particularly miR-455-3p, may play a crucial role in modulating fibrosis-related pathways. This narrative review explores the potential of miR-455-3p as a biomarker and therapeutic target in liver fibrosis among MASLD patients. The miR-455-3p’s effects on pathways, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) signaling and extracellular matrix remodeling, both of which are pivotal in hepatic fibrosis. Additionally, the influence of miR-455-3p on hepatic stellate cell activation—a key process in fibrotic progression, should be considered. By challenging current perspectives, this review aims to elucidate the role of miR-455-3p in liver fibrosis, ultimately contributing to a deeper understanding of liver fibrosis mechanisms and highlighting the potential for innovative MASLD treatment strategies.

Keywords:

Background

Liver Fibrosis in MASLD

The Pathophysiology of Liver Fibrosis in MASLD

Liver Fibrosis Biomarkers

The miRNAs as Liver Fibrosis Biomarkers

The Role of miR-455-3p in Liver Fibrosis

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Mokhtare, M.; Abdi, A.; Sadeghian, A.M.; Sotoudeheian, M.; Namazi, A.; Sikaroudi, M.K. Investigation about the correlation between the severity of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 58, 221–227. [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. Galectin-3 and Severity of Liver Fibrosis in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Protein Pept. Lett. 2024, 31, 290–304. [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. Agile 3+ and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: Detecting Advanced Fibrosis based on Reported Liver Stiffness Measurement in FibroScan and Laboratory Findings. Int. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Dis. 2024, 03, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Tan, J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, M.; He, Y. MicroRNAs in metabolic dysfunction-associated diseases: Pathogenesis and therapeutic opportunities. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70038. [CrossRef]

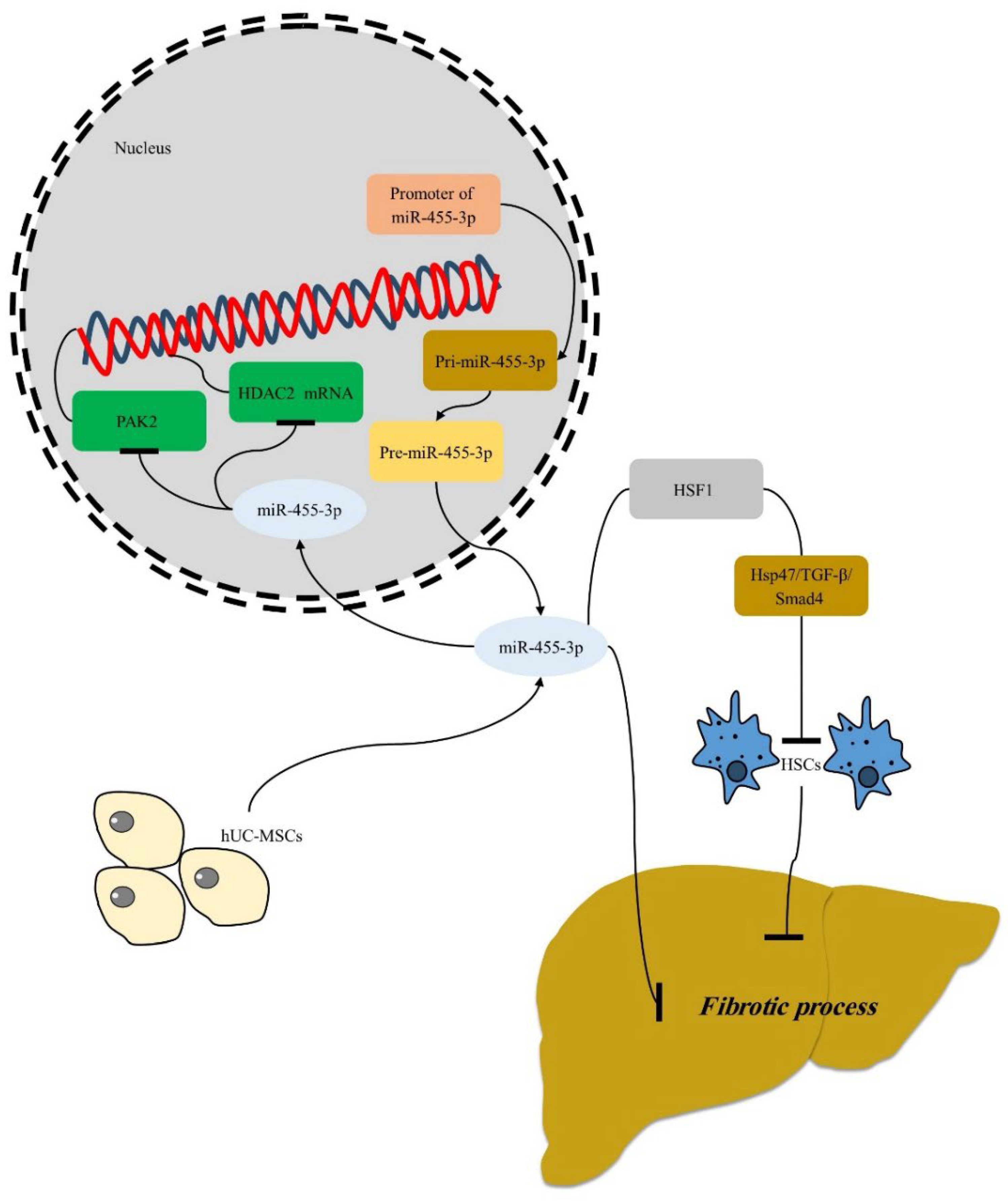

- Wei, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Qiu, J.; Li, C.; Shi, C.; Zhou, S.; Liu, R.; Lu, L. miR-455-3p Alleviates Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis by Suppressing HSF1 Expression. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2019, 16, 758–769. [CrossRef]

- Fan W, Bradford TM, Török NJ. Metabolic dysfunction− associated liver disease and diabetes: Matrix remodeling, fibrosis, and therapeutic implications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2024;1538:21-33.

- Ciardullo, S.; Perseghin, G. Prevalence of NAFLD, MAFLD and associated advanced fibrosis in the contemporary United States population. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1290–1293. [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Alizadeh-Tabari, S.; Ajmera, V.; Singh, S.; Murad, M.H.; Loomba, R. Global Prevalence of Advanced Liver Fibrosis and Cirrhosis in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Buckholz, A.; Kumar, S.; Newberry, C. Implications of Protein and Sarcopenia in the Prognosis, Treatment, and Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Nutrients 2024, 16, 658. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.; Tacke, F.; Arrese, M.; Sharma, B.C.; Mostafa, I.; Bugianesi, E.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Yilmaz, Y.; George, J.; Fan, J.; et al. Global Perspectives on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2019, 69, 2672–2682. [CrossRef]

- Schneider CV, Schneider KM, Raptis A, Huang H, Trautwein C, Loomba R. Prevalence of at-risk MASH, M et ALD and alcohol-associated steatotic liver disease in the general population. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2024;59:1271-81.

- Younossi, Z.M.; Kalligeros, M.; Henry, L. Epidemiology of Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Parente, A.; Milana, F.; Hajibandeh, S.; Menon, K.V.; Kim, K.-H.; Shapiro, A.M.J.; Schlegel, A. Liver transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease versus other etiologies: A meta-analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Cao, Y.-Y.; Zheng, M.-H. Current status and future trends of the global burden of MASLD. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 35, 697–707. [CrossRef]

- Torre, E.; Di Matteo, S.; Martinotti, C.; Bruno, G.M.; Goglia, U.; Testino, G.; Rebora, A.; Bottaro, L.C.; Colombo, G.L. Economic Impact of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) in Italy. Analysis and Perspectives. Clin. Outcomes Res. 2024, ume 16, 773–784. [CrossRef]

- Theys C. The new epigenetic driver role of PPARα and mitochondria in metabolic dysfunction associated liver disease (MASLD), paving the way towards new therapeutics and diagnostic biomarkers: University of Antwerp; 2024.

- Venkatesan N, Doskey LC, Malhi H. The Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum in Lipotoxicity during MASLD Pathogenesis. The American Journal of Pathology. 2023.

- Arumugam, M.K.; Gopal, T.; Kandy, R.R.K.; Boopathy, L.K.; Perumal, S.K.; Ganesan, M.; Rasineni, K.; Donohue, T.M.; Osna, N.A.; Kharbanda, K.K. Mitochondrial Dysfunction-Associated Mechanisms in the Development of Chronic Liver Diseases. Biology 2023, 12, 1311. [CrossRef]

- Karkucinska-Wieckowska, A.; Simoes, I.C.M.; Kalinowski, P.; Lebiedzinska-Arciszewska, M.; Zieniewicz, K.; Milkiewicz, P.; Górska-Ponikowska, M.; Pinton, P.; Malik, A.N.; Krawczyk, M.; et al. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A complex relationship. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 52, e13622. [CrossRef]

- Svegliati-Baroni, G.; Pierantonelli, I.; Torquato, P.; Marinelli, R.; Ferreri, C.; Chatgilialoglu, C.; Bartolini, D.; Galli, F. Lipidomic biomarkers and mechanisms of lipotoxicity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. 2019, 144, 293–309. [CrossRef]

- Białek W, Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, Czechowicz P, Sławski J, Collawn JF, Czogalla A, et al. The lipid side of unfolded protein response. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2024:159515.

- Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, N.; Huang, Y.; Hu, T.; Rao, C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated cell death in liver injury. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, N.U.; Sheikh, T.A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Free. Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 1405–1418. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, N.; Coelho, I.C.; Patarrão, R.S.; Almeida, J.I.; Penha-Gonçalves, C.; Macedo, M.P. How Inflammation Impinges on NAFLD: A Role for Kupffer Cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lee, G.; Heo, S.-Y.; Roh, Y.-S. Oxidative Stress Is a Key Modulator in the Development of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 11, 91. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Duan, Q.; Wu, R.; Harris, E.N.; Su, Q. Pathophysiological communication between hepatocytes and non-parenchymal cells in liver injury from NAFLD to liver fibrosis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 176, 113869. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Diaz, J.G.; Um, E.; Hahn, Y.S. Major roles of kupffer cells and macrophages in NAFLD development. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Liu, F.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Ding, W.-X.; Feng, D.; Ji, Y.; Qin, X. Kupffer cells promote T-cell hepatitis by producing CXCL10 and limiting liver sinusoidal endothelial cell permeability. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7163–7177. [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Diaz, J.; Gomez-Llorente, C.; Fontana, L.; Gil, A. Modulation of immunity and inflammatory gene expression in the gut, in inflammatory diseases of the gut and in the liver by probiotics. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 15632–49. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, T.; Friedman, S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 397–411. [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, B.; Meyer, C.; Dooley, S.; Meindl-Beinker, N. TGF-β in Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrogenesis—Updated 2019. Cells 2019, 8, 1419. [CrossRef]

- Ni X-X, Li X-Y, Wang Q, Hua J. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activity affects the hepatic stellate cell activation and the progression of NASH via TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway. Journal of physiology and biochemistry. 2021;77:35-45.

- Breitkopf K, Weng H, Dooley S. TGF-β/Smad-signaling in liver cells: Target genes and inhibitors of two parallel pathways. Signal Transduction. 2006;6:329-37.

- Kikuchi AT. Emerging Roles of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor Alpha in Chronic Liver Injury: Potential Therapeutic Target in Hepatic Fibrosis: University of Pittsburgh; 2017.

- Bocca, C.; Protopapa, F.; Foglia, B.; Maggiora, M.; Cannito, S.; Parola, M.; Novo, E. Hepatic Myofibroblasts: A Heterogeneous and Redox-Modulated Cell Population in Liver Fibrogenesis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1278. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, X.; Cheng, J.; He, Y.; Jiang, Y. NADPH Oxidase Signaling Pathway Mediates Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Induced Inhibition of Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.K.; Jun, J.; Du, K.; Diehl, A.M. Hedgehog Signaling: Implications in Liver Pathophysiology. Semin. Liver Dis. 2023, 43, 418–428. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-W.; Kim, Y.J. The evidence-based multifaceted roles of hepatic stellate cells in liver diseases: A concise review. Life Sci. 2024, 344, 122547. [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Wang, F.; Zhai, D.; Meng, X.; Liu, J.; Lv, X. Matrix metalloproteinases induce extracellular matrix degradation through various pathways to alleviate hepatic fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114472. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, A.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Xu, A.; Yan, X.; Han, Q.; Wang, B.; You, H.; Chen, W. Crosstalk of lysyl oxidase-like 1 and lysyl oxidase prolongs their half-lives and regulates liver fibrosis through Notch signal. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8. [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Sayed, N.; Allawadhi, P.; Weiskirchen, R. It’s all about the spaces between cells: role of extracellular matrix in liver fibrosis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 728–728. [CrossRef]

- Breitkopf, K.; Godoy, P.; Ciuclan, L.; Singer, M.V.; Dooley, S. TGF-β/Smad Signaling in the Injured Liver. Z. Fur Gastroenterol. 2006, 44, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.-Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, W.-Y.; Zhang, H.-H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.-Z.; Fang, J.; Yu, C.-H. PDGF signaling pathway in hepatic fibrosis pathogenesis and therapeutics. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 7879–7889. [CrossRef]

- Bourebaba, N.; Marycz, K. Hepatic stellate cells role in the course of metabolic disorders development – A molecular overview. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 170, 105739. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Friedman, S.L. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in liver injury and hepatic fibrogenesis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2010, 3, 21–21. [CrossRef]

- Paik, Y.-H.; Schwabe, R.F.; Bataller, R.; Russo, M.P.; Jobin, C.; Brenner, D.A. Toll–Like Receptor 4 Mediates Inflammatory Signaling by Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide in Human Hepatic Stellate Cells. Hepatology 2003, 37, 1043–1055. [CrossRef]

- Akkız, H.; Gieseler, R.K.; Canbay, A. Liver Fibrosis: From Basic Science towards Clinical Progress, Focusing on the Central Role of Hepatic Stellate Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7873. [CrossRef]

- Duspara, K.; Bojanic, K.; Pejic, J.I.; Kuna, L.; Kolaric, T.O.; Nincevic, V.; Smolic, R.; Vcev, A.; Glasnovic, M.; Curcic, I.B.; et al. Targeting the Wnt Signaling Pathway in Liver Fibrosis for Drug Options: An Update. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2021, 000, 000–000. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qi, Y.-F.; Yu, Y.-R. STAT3: A key regulator in liver fibrosis. 2020, 21, 100224. [CrossRef]

- Xiang D-M, Sun W, Ning B-F, Zhou T-F, Li X-F, Zhong W, et al. The HLF/IL-6/STAT3 feedforward circuit drives hepatic stellate cell activation to promote liver fibrosis. Gut. 2018;67:1704-15.

- Mia, M.M.; Singh, M.K. New Insights into Hippo/YAP Signaling in Fibrotic Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 2065. [CrossRef]

- Driskill, J.H.; Pan, D. The Hippo Pathway in Liver Homeostasis and Pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2020, 16, 299–322. [CrossRef]

- Schiavoni, G.; Messina, B.; Scalera, S.; Memeo, L.; Colarossi, C.; Mare, M.; Blandino, G.; Ciliberto, G.; Bon, G.; Maugeri-Saccà, M. Role of Hippo pathway dysregulation from gastrointestinal premalignant lesions to cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Dong, B. Molecular mechanisms in MASLD/MASH-related HCC. Hepatology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Tao, H.; Lu, C.; Yang, J.-J. m6A epitranscriptomic and epigenetic crosstalk in liver fibrosis: Special emphasis on DNA methylation and non-coding RNAs. Cell. Signal. 2024, 122, 111302. [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Qiu, X.; Liu, H.; Gan, C.; Tan, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ye, T. Epigenetic regulation in fibrosis progress. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 173, 105910. [CrossRef]

- Tobaruela-Resola, A.L.; Milagro, F.I.; Elorz, M.; Benito-Boillos, A.; Herrero, J.I.; Mogna-Peláez, P.; Tur, J.A.; Martínez, J.A.; Abete, I.; Zulet, M.. Circulating miR-122-5p, miR-151a-3p, miR-126-5p and miR-21-5p as potential predictive biomarkers for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease assessment. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Kumar, V.; Sud, N.; Mahato, R.I. MicroRNAs in the pathogenesis and treatment of progressive liver injury in NAFLD and liver fibrosis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 129, 54–63. [CrossRef]

- Iacobini, C.; Menini, S.; Ricci, C.; Fantauzzi, C.B.; Scipioni, A.; Salvi, L.; Cordone, S.; Delucchi, F.; Serino, M.; Federici, M.; et al. Galectin-3 ablation protects mice from diet-induced NASH: A major scavenging role for galectin-3 in liver. J. Hepatol. 2010, 54, 975–983. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Niki, T.; Nomura, T.; Oura, K.; Tadokoro, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Tani, J.; Yoneyama, H.; Morishita, A.; Kuroda, N.; et al. Correlation between serum galectin-9 levels and liver fibrosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 33, 492–499. [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Philips, C.A.; Chen, J.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Guo, X.; Qi, X. Role of Galectins in the Liver Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Shen, Q.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Shuai, M.; Zheng, S. Galectin-1 gene silencing inhibits the activation and proliferation but induces the apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells from mice with liver fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 43, 103–116. [CrossRef]

- Wu M-H, Chen Y-L, Lee K-H, Chang C-C, Cheng T-M, Wu S-Y, et al. Glycosylation-dependent galectin-1/neuropilin-1 interactions promote liver fibrosis through activation of TGF-β-and PDGF-like signals in hepatic stellate cells. Scientific reports. 2017;7:11006.

- Potikha, T.; Pappo, O.; Mizrahi, L.; Olam, D.; Maller, S.M.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Galun, E.; Goldenberg, D.S. Lack of galectin-1 exacerbates chronic hepatitis, liver fibrosis, and carcinogenesis in murine hepatocellular carcinoma model. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 7995–8007. [CrossRef]

- Kawanaka, M.; Kamada, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Iwaki, M.; Nishino, K.; Zhao, W.; Seko, Y.; Yoneda, M.; Kubotsu, Y.; Fujii, H.; et al. Serum Cytokeratin 18 Fragment Is an Indicator for Treating Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Gastro Hep Adv. 2024, 3, 1120–1128. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Rios, R.S.; Boursier, J.; Anty, R.; Chan, W.-K.; George, J.; Yilmaz, Y.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Fan, J.; Dufour, J.-F.; et al. Hepatocyte apoptosis fragment product cytokeratin-18 M30 level and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis risk diagnosis: an international registry study. Chin. Med J. 2023, 136, 341–350. [CrossRef]

- Meurer, S.K.; Karsdal, M.A.; Weiskirchen, R. Advances in the clinical use of collagen as biomarker of liver fibrosis. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 20, 947–969. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.J.; Veidal, S.S.; Karsdal, M.A.; Ørsnes-Leeming, D.J.; Vainer, B.; Gardner, S.D.; Hamatake, R.; Goodman, Z.D.; Schuppan, D.; Patel, K. Plasma Pro-C3 (N-terminal type III collagen propeptide) predicts fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2014, 35, 429–437. [CrossRef]

- Del Turco, S.; De Simone, P.; Ghinolfi, D.; Gaggini, M.; Basta, G. Comparison between galectin-3 and YKL-40 levels for the assessment of liver fibrosis in cirrhotic patients. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 22, 187–192. [CrossRef]

- JABEEN R, JAMI A, SAEED A, NAEEM ST. Significance of YKL-40 in comparison to Fibroscan Elastography in Staging liver Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis C.

- Mehta, P.; Ploutz-Snyder, R.; Nandi, J.; Rawlins, S.R.; Sanderson, S.O.; Levine, R.A. Diagnostic Accuracy of Serum Hyaluronic Acid, FIBROSpect II, and YKL-40 for Discriminating Fibrosis Stages in Chronic Hepatitis C. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 928–936. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ji, J.; Han, X. Osteopontin: an essential regulatory protein in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Histochem. J. 2023, 55, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Song, J.; Du, R.; Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Bai, F.; Liang, J.; Lin, T.; Liu, J.; et al. Prognostic significance of osteopontin in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig. Liver Dis. 2007, 39, 167–172. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.S.; Claridge, L.C.; Jhaveri, R.; Swiderska-Syn, M.; Clark, P.; Suzuki, A.; Pereira, T.A.; Mi, Z.; Kuo, P.C.; Guy, C.D.; et al. Osteopontin is up-regulated in chronic hepatitis C and is associated with cellular permissiveness for hepatitis C virus replication. Clin. Sci. 2014, 126, 845–855. [CrossRef]

- Soysouvanh, F.; Rousseau, D.; Bonnafous, S.; Bourinet, M.; Strazzulla, A.; Patouraux, S.; Machowiak, J.; Farrugia, M.A.; Iannelli, A.; Tran, A.; et al. Osteopontin-driven T-cell accumulation and function in adipose tissue and liver promoted insulin resistance and MAFLD. Obesity 2023, 31, 2568–2582. [CrossRef]

- Coombes, J.D.; Manka, P.P.; Swiderska-Syn, M.; Vannan, D.T.; Riva, A.; Claridge, L.C.; Moylan, C.; Suzuki, A.; Briones-Orta, M.A.; Younis, R.; et al. Osteopontin Promotes Cholangiocyte Secretion of Chemokines to Support Macrophage Recruitment and Fibrosis in MASH. Liver Int. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Remmerie, A.; Martens, L.; Thoné, T.; Castoldi, A.; Seurinck, R.; Pavie, B.; Roels, J.; Vanneste, B.; De Prijck, S.; Vanhockerhout, M.; et al. Osteopontin Expression Identifies a Subset of Recruited Macrophages Distinct from Kupffer Cells in the Fatty Liver. Immunity 2020, 53, 641–657.e14. [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeheian, M. Value of Mac-2 Binding Protein Glycosylation Isomer (M2BPGi) in Assessing Liver Fibrosis in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Liver Disease: A Comprehensive Review of its Serum Biomarker Role. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2024, 25, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Magkrioti, C.; Galaris, A.; Kanellopoulou, P.; Stylianaki, E.-A.; Kaffe, E.; Aidinis, V. Autotaxin and chronic inflammatory diseases. J. Autoimmun. 2019, 104, 102327. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, H.; Ikeda, H.; Nakamura, K.; Ohkawa, R.; Masuzaki, R.; Tateishi, R.; Yoshida, H.; Watanabe, N.; Tejima, K.; Kume, Y.; et al. Autotaxin as a novel serum marker of liver fibrosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2011, 412, 1201–1206. [CrossRef]

- Kaffe, E.; Katsifa, A.; Xylourgidis, N.; Ninou, I.; Zannikou, M.; Harokopos, V.; Foka, P.; Dimitriadis, A.; Evangelou, K.; Moulas, A.N.; et al. Hepatocyte autotaxin expression promotes liver fibrosis and cancer. Hepatology 2017, 65, 1369–1383. [CrossRef]

- Shiha G, Mousa N. Noninvasive Biomarkers for Liver Fibrosis. Liver Diseases: A Multidisciplinary Textbook. 2020:427-41.

- A Lidbury, J.; Hoffmann, A.R.; Fry, J.K.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Steiner, J.M. Evaluation of hyaluronic acid, procollagen type III N-terminal peptide, and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as serum markers of canine hepatic fibrosis.. 2016, 80, 302–308.

- Baranova, A.; Lal, P.; Birerdinc, A.; Younossi, Z.M. Non-Invasive markers for hepatic fibrosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011, 11, 91–91. [CrossRef]

- Salkic, N.N.; Jovanovic, P.; Hauser, G.; Brcic, M. FibroTest/Fibrosure for Significant Liver Fibrosis and Cirrhosis in Chronic Hepatitis B: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 796–809. [CrossRef]

- Poynard T, Vergniol J, Ngo Y, Foucher J, Thibault V, Munteanu M, et al. Staging chronic hepatitis B into seven categories, defining inactive carriers and assessing treatment impact using a fibrosis biomarker (FibroTest®) and elastography (FibroScan®). Journal of Hepatology. 2014;61:994-1003.

- Treeprasertsuk S, Björnsson E, Enders F, Suwanwalaikorn S, Lindor KD. NAFLD fibrosis score: a prognostic predictor for mortality and liver complications among NAFLD patients. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2013;19:1219.

- Ciardullo S, Perseghin G. Advances in fibrosis biomarkers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Advances in Clinical Chemistry: Elsevier; 2022. p. 33-65.

- Martinou, E.; Pericleous, M.; Stefanova, I.; Kaur, V.; Angelidi, A.M. Diagnostic Modalities of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Biochemical Biomarkers to Multi-Omics Non-Invasive Approaches. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 407. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-T.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Tsai, M.-H.; Han, C.-L.; Mersmann, H.J.; Ding, S.-T. Identification of Potential Plasma Biomarkers for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Integrating Transcriptomics and Proteomics in Laying Hens. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Xia W, Lv Z, Ni C, Xin Y, Yang L. Liquid biopsy for cancer: circulating tumor cells, circulating free DNA or exosomes? Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2017;41:755-68.

- Temraz, S.; Nasr, R.; Mukherji, D.; Kreidieh, F.; Shamseddine, A. Liquid biopsy derived circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA as novel biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 507–518. [CrossRef]

- Gerussi, A.; Scaravaglio, M.; Cristoferi, L.; Verda, D.; Milani, C.; De Bernardi, E.; Ippolito, D.; Asselta, R.; Invernizzi, P.; Kather, J.N.; et al. Artificial intelligence for precision medicine in autoimmune liver disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 966329. [CrossRef]

- Baciu, C.; Xu, C.; Alim, M.; Prayitno, K.; Bhat, M. Artificial intelligence applied to omics data in liver diseases: Enhancing clinical predictions. Front. Artif. Intell. 2022, 5, 1050439. [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.; Venkatasamy, A.; Saviano, A.; Lupberger, J.; Hoshida, Y.; Vilgrain, V.; Nahon, P.; Reinhold, C.; Gallix, B.; Baumert, T.F. Conventional and artificial intelligence-based imaging for biomarker discovery in chronic liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2022, 16, 509–522. [CrossRef]

- Nappi, F. Non-Coding RNA-Targeted Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3630. [CrossRef]

- Arrese, M.; Eguchi, A.; Feldstein, A.E. Circulating microRNAs: Emerging Biomarkers of Liver Disease. Semin. Liver Dis. 2015, 35, 043–054. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, N.; Chakrabarti, S. Role of long non-coding RNAs and related epigenetic mechanisms in liver fibrosis (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 47, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ge, G.; Pan, T.; Wen, D.; Gan, J. A Pilot Study of Serum MicroRNAs Panel as Potential Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e105192. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y.; Mackowiak, B.; Gao, B. MicroRNAs as regulators, biomarkers and therapeutic targets in liver diseases. Gut 2020, 70, 784–795. [CrossRef]

- Noetel, A.; Kwiecinski, M.; Elfimova, N.; Huang, J.; Odenthal, M. microRNA are Central Players in Anti- and Profibrotic Gene Regulation during Liver Fibrosis. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 49. [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, S.; Pfeffer, S.; Baumert, T.F.; Zeisel, M.B. miR-122 – A key factor and therapeutic target in liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 448–457. [CrossRef]

- Long J-K, Dai W, Zheng Y-W, Zhao S-P. miR-122 promotes hepatic lipogenesis via inhibiting the LKB1/AMPK pathway by targeting Sirt1 in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Molecular Medicine. 2019;25:1-13.

- Xue, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Peng, C.; Li, Y. A comprehensive review of miR-21 in liver disease: Big impact of little things. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 134, 112116. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Huang, C.-L.; Wang, H.-W.; Hsu, W.-F.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Chen, S.-H.; Peng, C.-Y. Serum miR-21 correlates with the histological stage of chronic hepatitis B-associated liver fibrosis. 2019, 12, 3819–+.

- Li W, Yu X, Chen X, Wang Z, Yin M, Zhao Z, et al. HBV induces liver fibrosis via the TGF-β1/miR-21-5p pathway. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2021;21:1-.

- Yang F, Luo L, Zhu Z-D, Zhou X, Wang Y, Xue J, et al. Chlorogenic acid inhibits liver fibrosis by blocking the miR-21-regulated TGF-β1/Smad7 signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017;8:929.

- Dalgaard, L.T.; Sørensen, A.E.; Hardikar, A.A.; Joglekar, M.V. The microRNA-29 family: role in metabolism and metabolic disease. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2022, 323, C367–C377. [CrossRef]

- Roderburg, C.; Urban, G.-W.; Bettermann, K.; Vucur, M.; Zimmermann, H.W.; Schmidt, S.; Janssen, J.; Koppe, C.; Knolle, P.; Castoldi, M.; et al. Micro-RNA profiling reveals a role for miR-29 in human and murine liver fibrosis. Hepatology 2011, 53, 209–218. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y-H, Yang Y-L, Wang F-S. The role of miR-29a in the regulation, function, and signaling of liver fibrosis. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018;19:1889.

- Kumar V, Kumar V, Luo J, Mahato RI. Therapeutic potential of OMe-PS-miR-29b1 for treating liver fibrosis. Molecular Therapy. 2018;26:2798-811.

- Bao, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, N.; Huang, C.; Chen, M.; Cheng, Q.; Yu, K.; Chen, S.; Zhu, M.; Shi, G. Serum MicroRNA Levels as a Noninvasive Diagnostic Biomarker for the Early Diagnosis of Hepatitis B Virus-Related Liver Fibrosis. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 860–869. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huo, Z.; He, X.; Liu, F.; Liang, J.; Wu, L.; Yang, D. The Role of MiR-29 in the Mechanism of Fibrosis. Mini-Reviews Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 1846–1858. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, W.; Fan, X.; Ma, \. A review of MASLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma: progress in pathogenesis, early detection, and therapeutic interventions. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1410668. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; McDaniel, K.; Wu, N.; Ramos-Lorenzo, S.; Glaser, T.; Venter, J.; Francis, H.; Kennedy, L.; Sato, K.; Zhou, T.; et al. Regulation of Cellular Senescence by miR-34a in Alcoholic Liver Injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 2788–2798. [CrossRef]

- Soluyanova, P.; Quintás, G.; Pérez-Rubio, .; Rienda, I.; Moro, E.; van Herwijnen, M.; Verheijen, M.; Caiment, F.; Pérez-Rojas, J.; Trullenque-Juan, R.; et al. The Development of a Non-Invasive Screening Method Based on Serum microRNAs to Quantify the Percentage of Liver Steatosis. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1423. [CrossRef]

- Shan W, Gao L, Zeng W, Hu Y, Wang G, Li M, et al. Activation of the SIRT1/p66shc antiapoptosis pathway via carnosic acid-induced inhibition of miR-34a protects rats against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell death & disease. 2015;6:e1833-e.

- Liang, M.; Xiao, X.; Chen, M.; Guo, Y.; Han, W.; Min, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yu, W. Artemisia capillaris Thunb. Water extract alleviates metabolic dysfunction-associated Steatotic liver disease Disease by inhibiting miR-34a-5p to activate Sirt1-mediated hepatic lipid metabolism. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 338, 119030. [CrossRef]

- Csak, T.; Bala, S.; Lippai, D.; Kodys, K.; Catalano, D.; Iracheta-Vellve, A.; Szabo, G. MicroRNA-155 Deficiency Attenuates Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis without Reducing Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Steatohepatitis. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0129251. [CrossRef]

- Bala, S.; Csak, T.; Saha, B.; Zatsiorsky, J.; Kodys, K.; Catalano, D.; Satishchandran, A.; Szabo, G. The pro-inflammatory effects of miR-155 promote liver fibrosis and alcohol-induced steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1378–1387. [CrossRef]

- Bala, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Nagesh, P.T.; Catalano, D.; Zivny, A.; Wang, Y.; Xie, J.; Gao, G.; Szabo, G. Therapeutic inhibition of miR-155 attenuates liver fibrosis via STAT3 signaling. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2023, 33, 413–427. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Zhang N, Wang Z, Ai D-m, Cao Z-y, Pan H-p. Decreased MiR-155 level in the peripheral blood of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients may serve as a biomarker and may influence LXR activity. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2016;39:2239-48.

- Mao, Y.; Chen, W.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S. Mechanisms and Functions of MiR-200 Family in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2021, ume 13, 13479–13490. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cai, W. The expression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition–related proteins in biliary epithelial cells is associated with liver fibrosis in biliary atresia. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 77, 310–315. [CrossRef]

- Yang J-J, Tao H, Liu L-P, Hu W, Deng Z-Y, Li J. miR-200a controls hepatic stellate cell activation and fibrosis via SIRT1/Notch1 signal pathway. Inflammation Research. 2017;66:341-52.

- Cong N, Du P, Zhang A, Shen F, Su J, Pu P, et al. Downregulated microRNA-200a promotes EMT and tumor growth through the wnt/β-catenin pathway by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1/ZEB2 in gastric adenocarcinoma. Oncology reports. 2013;29:1579-87.

- Mongroo PS, Rustgi AK. The role of the miR-200 family in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer biology & therapy. 2010;10:219-22.

- Wu, N.; Meng, F.; Zhou, T.; Han, Y.; Kennedy, L.; Venter, J.; Francis, H.; DeMorrow, S.; Onori, P.; Invernizzi, P.; et al. Prolonged darkness reduces liver fibrosis in a mouse model of primary sclerosing cholangitis by miR-200b down-regulation. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 4305–4324. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Wong, W.K.K.; Fan, B.; Lau, E.S.; Hou, Y.; O, C.K.; Luk, A.O.Y.; Chow, E.Y.K.; Ma, R.C.W.; Chan, J.C.N.; et al. Detection of increased serum miR-122-5p and miR-455-3p levels before the clinical diagnosis of liver cancer in people with type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Wang, L.; Bu, F.; Meng, H.; Pan, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, A.; Yin, N.; Huang, C.; et al. The miR-455-3p/HDAC2 axis plays a pivotal role in the progression and reversal of liver fibrosis and is regulated by epigenetics. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21700. [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Xu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Shu, Y.; Cao, X.; Chen, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, R.; et al. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate IL-6-induced acute liver injury through miR-455-3p. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Gu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhuansun, X.; Xu, S.; Kuang, Y. Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorate Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis by Upregulating MicroRNA-455-3p through Suppression of p21-Activated Kinase-2. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).