1. Introduction

The white cocoyam (ocumo, tannia, yautía, quequisque, tiquisque or malanga) (

Xanthosoma sagittifolium) and the purple cocoyam (

Xanthosoma violaceum) are plants that produce edible subway stems. Both species of cocoyam are propagated only asexually, through corm or cormels sections [

1]. Propagation by sexual seed is not done because flowering is very scarce [

2]. In the purple cocoyam, although flowering is more frequent, seed formation is very erratic [

3].

The cocoyam (

Xanthosoma spp.) of the Araceae family is native to the American continent. The genus has about 45 species and within each species there are different clones [

4]. According to Montaldo [

5], the main species are

Xanthosoma sagittifolium (white cocoyam) and

Xanthosoma violaceum (purple cocoyam). Their vegetative cycle is 8 to 12 months, although they are perennial plants and from an agronomic point of view are considered annuals [

6].

In cocoyam the inflorescences occurring in the last two nights and are protandrous in some species but not in others, passing from the pistillate phase, which attracts pollinators the night it opens, to a staminate phase on the second night, when pollen is released [

7]. When the inflorescence opens, it produces heat and gives off a sweet odor that attracts its pollinators, dinasthine beetles (

Cyclocephala spp.). The flowers are produced in spadixes, unisexual, the female flowers are pistillate and are located at the base of the spadix; the male flowers are staminate with a group of sterile flowers between the two zones [

8].

Some attempts to increase genetic diversity in this crop involve the production of sexual seed through the application of gibberellic acid (GA

3) as a flowering inducer [

9,

10]. Volin and Zettler [

11], were one of the first authors to report on

Xanthosoma flowering and seed production from crossing several clones of

Xanthosoma caracu that flowered naturally in the State of Florida in the United States of America. Besides, foliar applications of this phytohormone, at concentrations of 500 mg.L

-1, induced uniform flowering in several

Xanthosoma species, resulting in the production of true botanical seeds by hand pollination [

12]. Another effective method to inducing inflorescences in

Colocasia cultivars is injecting GA

3 near the apical meristem, even in cultivars that are difficult to flower [

13].

In Cuba,

Xanthosoma spp. cultivars rarely or never produce inflorescences. Propagation of this genus has been through rhizomes or fractions of these for a long time, which has caused the loss of its ability to reproduce sexually [

14]. Following this approach and taking into account that the Genetic Improvement Program (GIP) of the Research Institute of Tropical Roots and Tuber Crops (INIVIT), since its inception, has not been able to obtain botanical seed in this genus of plants by conventional methods, it was decided to rearrange the analyses to investigate in other methods that could induce flowering and finally obtain botanical seeds through directed crosses in the selected parents. To achieve this, the research was designed to contrast the reproducibility of the exposed methods under controlled conditions in a preliminary study using the plant growth regulators Gibberellic Acid (GA

3) and VIUSID

® Agro as flowering inducers.

2. Materials and Methods

The preliminary study was carried out at the Research Institute of Tropical Roots and Tuber Crops (INIVIT, 22°35'10"N, 80°13'35"W) as part of the Genetic Improvement Program (GIP) developed in the genus (

Colocasia esculenta [L.] Schott) and the genus (

Xanthosoma spp.). On this occasion, accessions were identified that, due to the color of the corm mass, could represent genetic diversity. Subsequently, the “plus plants” of these accessions that integrate the germplasm collection of cocoyam (

Xanthosoma spp.) were isolated; specifically, the edible species:

Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott, polymorphic species with diversity of shapes and colors but bringing together many common characters: 44 white mass (2n=26 chromosomes), 12 purple mass (2n=24 chromosomes) and two yellow mass (2n=26 chromosomes) and

Xanthosoma nigrum (Vell.) Mansf., a purple mass accession (2n=24 chromosomes) [

15].

For inducing flowering in the accessions of the genus

Xanthosoma spp., was using the previously method described by Katsura [

13], who succeeded in obtaining inflorescences in all the treated cultivars of

Colocasia, including those that were difficult to flower. Three formulated concentrations of GA

3 at 500, 750 and 1000 mg.L

-1 were applied in the plant base through injected with an amount of 5 mL of each concentrations using a disposable syringe (see

Figure 1a) at three different times with weekly frequencies. The first GA

3 injected started when the plants reached 5 cm diameter in the stem base. The study was designed in such a way that there was one plant for each dose and another plant with no dose (control) for a total of four plants per accession.

One week after the GA

3 treatments were completed, a foliar application was made with the plant growth promoter VIUSID

® Agro at the concentration of 0.2 mL.L

-1 (manufacturer's recommendation) due to its broad nutritional spectrum. VIUSID

® Agro is a plant growth regulator of natural origin marketed by the Spanish company Catalysis S.L. It is a product used to improve plant growth conditions, increase productivity and resistance to diseases and pests. It contains a blend of active ingredients, including ascorbic acid, vitamin B5, vitamin B6, folic acid, arginine, glycine, glucosamine and other essential nutrients. These components work together to activate vegetative growth, induce flowering and stem elongation, and promote cell multiplication. In addition, VIUSID

® Agro has additional benefits, such as the ability to reduce flower drop, increase the number of fruits, delay or accelerate fruit ripening without affecting fruit quality and improve fruit skin consistency [

16].

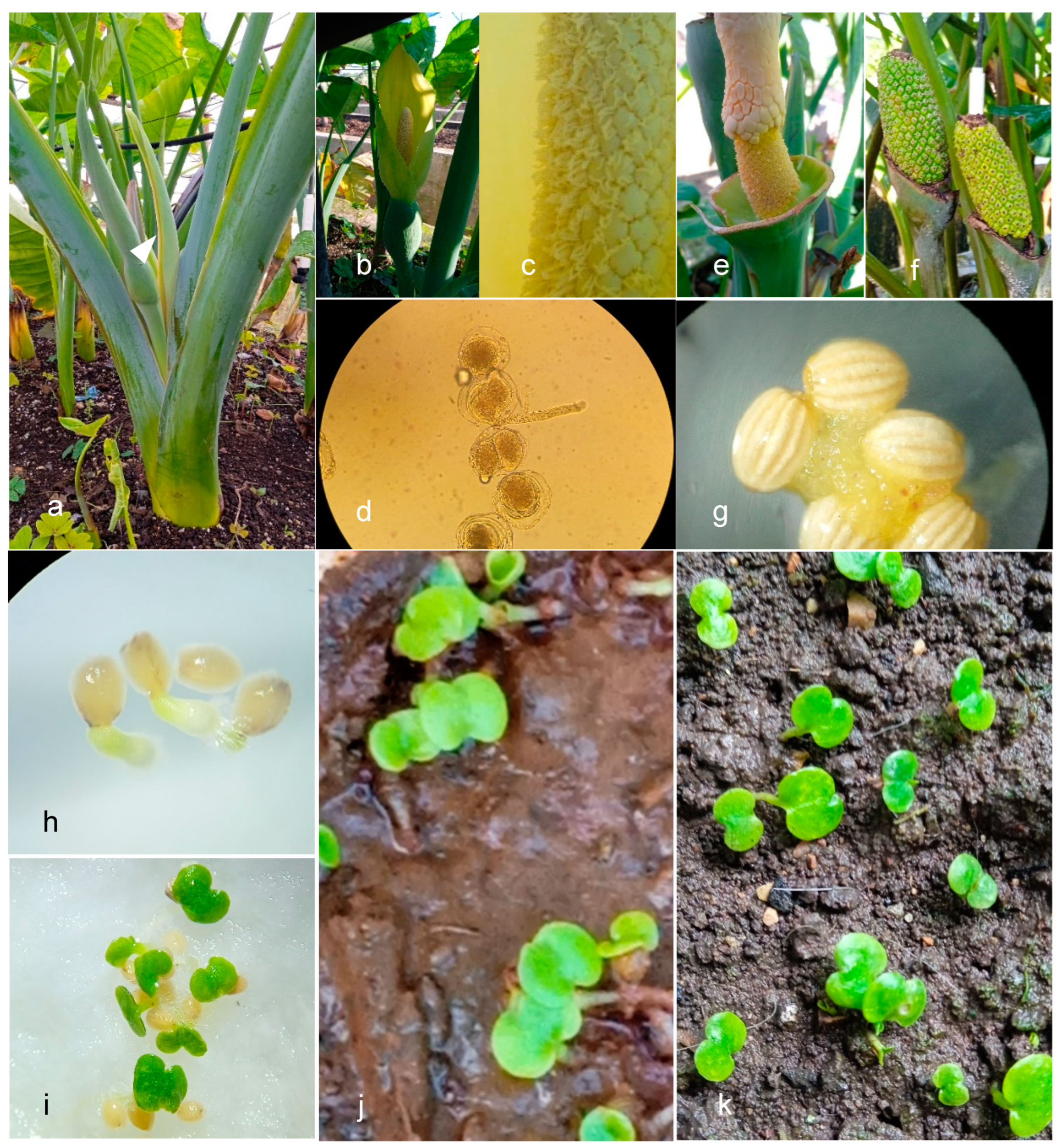

For pollinations, the first indication was the detection of a sweet odor, sometimes a little strong, expelled by the inflorescences, at which time the reproductive organs were uncovered by complete removal of the spathe before they opened. The exposed stigmas showed a yellow gelatinous exudation indicating the receptivity of the ovaries. These were coated with mature pollen from other inflorescences using a brush (

Figure 1b). The fertility of the pollen grains was analyzed using the Aceto-carmine staining method. Finally, the stigmas were coated with the lower tubular portion of the spathe without sectioning the spadix (

Figure 1c), in order to collect the pollen once emitted and make new crosses.

In the seed germination tests, seeds were allowed to germinate for one week after harvesting. Three different substrates and random seeds of the cross “Jibara” (X. sagittifolium) with “Morada 1726” (X. nigrum); and “Morada 1726” (X. nigrum) with “Morada 1726” (X. nigrum) were used for this purpose; in both cases the accession Morada 1726” (X. nigrum) was the female parent. In the first substrate, a Petri dish filled with moist cotton was used where the seeds were deposited, covered and the dish was placed in a shaded place at room temperature. For the second substrate, a magenta filled with moist black soil was used, the seeds were deposited and in the same way as the previous one, the magenta was placed in the shade at room temperature, and water was provided to it over time while it was losing moisture. In the third substrate, a magenta filled with red soil was used and the same procedure was followed as for the second substrate.

3. Results

Indistinctly, flowering was observed in the minority of plants treated with GA

3 and VIUSID

® Agro, some accessions first (easy flowering) than others (difficult flowering). This initially favored manual pollination due to the fact that the inflorescences of these species are protandrous; and also, the directed crossing of the parents, an action that could not be planned due to the small sample. The plants that were given doses of 500 and 750 mg.L

-1 of GA

3 did not flower (

Table 1), except for one accession, “Morada 1726” (easy flowering), which emitted two inflorescences per plant in each treatment. The other accessions emitted inflorescences only with the application of 1000 mg.L

-1. The control plants of all accessions did not flower. VIUSID

® Agro was applied by spraying, at the dose recommended by the manufacturer (0.2 mg.L

-1), to the leaves of all plants except the control until runoff occurred.

The first evidence of the action of these growth regulators was the expression of flag leaves in the leaf axils (

Figure 2a). This physiological expression started to appear at 19 weeks after starting the GA

3 injection method near the meristem. It should be emphasized that one plant per treatment was used, which means that it is not possible to show a statistical analysis of the study in question or to make an accurate judgment on the number of days elapsed in this phase. In general, most of the inflorescences obtained (

Figure 2b) showed no deformations, except for two inflorescences in the accession “Morada 1726” that developed two spathes, the first spathe enveloping the second. The study also showed a strong presence of anthers on the staminodes (

Figure 2c) giving rise to a considerable number of pollen grains; the latter (

Figure 2d) had a very high fertility and germination rate. The total covering of the stigmas by the collected pollen (

Figure 2e) led to the formation of a homogeneous fruit (

Figure 2f) in all the crosses achieved; these reached a vegetative cycle of 46 and 48 days, the ripening being distinguished by the change from green to yellow color and the presence of a sweet odor. Of all the pollinations performed, only eight were successful; the remaining ones never produced fruit and three days after pollination the stigmas showed dehydration and black color and the peduncles changed color from green to carmelite, showing dryness and finally dehiscence. Only one cross was achieved between the accession “Jibara” (

X.

sagittifolium) being the female parent and the accession “Morada 1726” (

X.

nigrum) being the male parent; the other crosses resulted from “Morada 1726” (

X.

nigrum) being the male and female parent. the seeds harvested (

Figure 2g) did not exceed 1.5 millimeters in length and the coloration varied from light to dark yellow; they were washed with ordinary water to remove the predominant mucilage and then stored. All the harvested seeds reached a mass of 10.6 grams. The average germination rate reached 92%. The germination tests carried out for a group of random seeds showed that they began to germinate nine days after sowing in the different substrates and after 16 days the last seeds germinated; this occurred in the three substrates without differing in time from one another (

Figure 2h–k).

So far, we can speak of a GIP of

Xanthosoma cocoyam structured in phases, starting with (Phase 1) Selection of parents. In this phase, accessions are carefully selected from the available germplasm bank that meet the qualitative and quantitative characters that can be inherited to the progenies. (Phase 2) Selection of the most efficient method to induce flowering; this phase involves materials that become indispensable for inducing inflorescence in cocoyam plants. In this case study, GA

3 and VIUSID

® Agro were used, with their doses still to be defined in future studies; likewise, further experimentation in an extended block design to improve the reproducibility of the method described by Katsura [

13]. The third phase, (Phase 3) Pollination, focuses on the technique of directed pollination taking into account the protandry of the flowers. In (Phase 4) Successful fertilization and fruit maintenance, great attention is given to fruit set with frequent application of irrigation and care of mechanical damage by insects. In (Phase 5) Harvesting, the days close to it are also taken into account, since at the moment of fruit ripening a sweet smell is released, which attracts insects and could cause seed loss. Once the seed extraction process has been completed, (Phase 6), seed germination, begins in order to assess the percentage of viability of the seed.

4. Discussion

The successful production of botanical seeds of Xanthosoma spp., marks a significant advance in the sustainable management of this crop in Cuba. Traditionally, the propagation of cocoyam Xanthosoma spp., has been based, both inside and outside the country, on asexual methods, that is, through corms and cormels, an implication that has led to a decrease in genetic diversity and sexual reproductive capacity. This preliminary study demonstrates that by using growth regulators such as Gibberellic Acid (GA3) and VIUSID® Agro, it is possible to induce inflorescences and seed production, thus revitalizing the genetic diversity of these plants. From an agroecological perspective, increasing genetic diversity within Xanthosoma spp. is crucial for improving resistance to pest organisms, diseases and changing environmental conditions.

The introduction of new progenies, resulting from the high viability of botanical seeds, an aspect in which few researchers and breeding programs of cocoyam Xanthosoma spp., in the world have achieved similarity with this result, not only facilitates the offspring of new genetic combinations and the heritability of traits, but also strengthens the overall adaptability of the crop. This scenario shows affinity with agroecological principles that make persistence in biodiversity a key factor in sustainable agricultural practices.

The results indicate that different concentrations of GA3 influenced the flowering rates of several accessions. In particular, the accession 'Morada 1726' showed a greater responsiveness to GA3 treatment, producing multiple inflorescences even at low concentrations. This suggests that certain genetic lines may be more susceptible to induced flowering, highlighting the importance of selecting appropriate mother plants for breeding programs. In addition, the use of VIUSID® Agro has shown promise in improving plant vitality and productivity. Its application was shown to favor flowering and overall plant health, making them less susceptible to biotic and abiotic stress factors. This is especially important in an agroecological context where the aim is to minimize chemical inputs and maximize natural growth processes.

Seed characteristics and parameters (

Figure 2g) are similar to earlier report in this species plants, but the germination rate (92%) was higher to observed before in this plant species (85%) [

12]. High germination rates are indicative of conventional seed production improvements and are essential to ensure that new clonal progenies of

Xanthosoma spp. can be grown effectively. These findings indicate that

Xanthosoma spp., seed production could have been favored by the application of the growth regulators GA

3 and VIUSID

® Agro; and it was maintained until three months after the seeds were stored at room temperature, differing from these same authors who reported long seed life under other storage conditions.

5. Conclusions

In the context in which the study was developed, it is very hasty to determine conclusions with the results; even so, it can be stated that the application of Gibberellic Acid (GA3) and VIUSID® Agro proved to be a viable method to induce flowering in the different accessions of cocoyam; suggesting to investigate in new combinations to find the most effective dose, although in the study the combination of 1000 mg.L-1 of GA3 with 0.2 mL.L-1 of VIUSID® Agro proved to be the dose that induced the greatest number of inflorescences. It can also be added that the success rate in pollination is a limiting factor in the process, since it is dependent on the protandric condition of the inflorescences.

The study suggests that a broader and more systematic experimental design could improve the reproducibility of the methods used and increase the success rate of flowering induction and botanical seed production. The results open the door to future research that could explore different concentrations and combinations of plant growth regulators, as well as the implementation of more efficient pollination techniques. This research not only contributes to our understanding of the reproductive biology of Xanthosoma spp. but also provides a framework for integrating agroecological principles into crop improvement strategies. Future research should focus on exploring what would be the efficacy of GA3 to induce flowering in the absence of VIUSID® Agro and its interactions with environmental factors to further optimize seed production.

6. Patents

The patents related to the study are assumed to relate to the commercial product VIUSID® Agro.

Author Contributions

AJ and AM conceived and designed the research. AJ performed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. DG and BK contributed the materials and products. AM and AC reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the professionals and workers of the Research Institute of Tropical Roots and Tuber Crops (INIVIT) who collaborated directly or otherwise in obtaining this result. We also thank Dr. Bulent's work team for providing the commercial product VIUSID® Agro in its different presentations to carry out the research. And another special thanks to the Ph.D Plant Biology: Vincent Lebot and the Doctor in Agricultural Sciences: Ivan Javier Pastrana Vargas for their contributions to the knowledge and accompaniment in this result.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- León, J. (1987). Botánica de los cultivos tropicales (2da. Ed). IICA.

- O’Hair, S. K., & Asokan, M. P. (1986). Edible aroids: Botany and horticulture. Horticultural reviews, 8, 43-99.

- Saborío, F., L., S., & R. (2000). Introducción de floración en Tiquisque (Xanthosoma ssp) en cinco regiones de Costa Rica. Agronomía Costarricense, 24, 37-45.

- Vásquez, B. E., & López, F. R. (1984). Raíces y tubérculos. La Habana Pueblo y Educación, 245, 248.

- Montaldo, A. (1991). Cultivo de raíces y tubérculos tropicales (Vol. 21). Agroamerica.

- Rivas, A. F. G., & Najeres, L. I. F. (2008). Estudio del proceso de floración inducido por el ácido giberelico (AG3) en nueve cultivares de quequisque (Xanthosoma spp) en Nicaragua.

- Valerio, C. (1988). Notes on phenology and pollination of Xanthosoma wendlandii (Araceae) in Costa Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical, 36(1), 55-61.

- Varela, Torres, D., & Saavedra, D. (2000). Cultivo del quequisque. Guía Tecnológica (Nicaragua), 24.

- Alamu, S., & McDavid, C. R. (1978). Promotion of flowering in edible aroids by gibberellic acid. Tropical Agriculture, 55(1), 81-86.

- Onokpise, O. U., Boya-Meboka, M., & Wutoh, J. G. (1992). Hybridisation and fruit formation in macabo cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott). Annals of Applied Biology, 120(3), 527-535. [CrossRef]

- Volin, R. B., & Zettler, F. W. (1976). Seed Propagation of Cocoyam, Xanthosoma caracu Koch & Bouche1. HortScience, 11(5), 459-460.

- Goenaga, R., & Hepperly, P. (1990). Flowering induction, pollen and seed viability and artificial hybridization of taniers (Xanthosoma spp.). The Journal of Agriculture of the University of Puerto Rico, 74(3), 253-260. [CrossRef]

- Katsura, N., Takayanagi, K., & Sato, T. (1986). Gibberellic Acid Induced Flowering in Cultivars of Japanese. Taro. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science, 55(1), 69-74. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M. D. M. (2018). Revisión bibliográfica RECURSOS GENÉTICOS DE LA MALANGA DEL GÉNERO Xanthosoma Schott EN CUBA. 39(2).

- Jiménez, M. D. M., Concepción, O. M., & Aguila, Y. F. (2018). Integrated Characterization of Cuban Germplasm of Cocoyam (Xanthosoma Sagittifolium (L.) Schott). Journal of Plant Genetics and Crop Research, 1(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- CATALYSIS AGRO – Investigación y el desarrollo de productos dentro de los sectores cosmético y dietético. (s. f.). Recuperado 1 de mayo de 2024, de https://catalysisagro.es/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).