Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

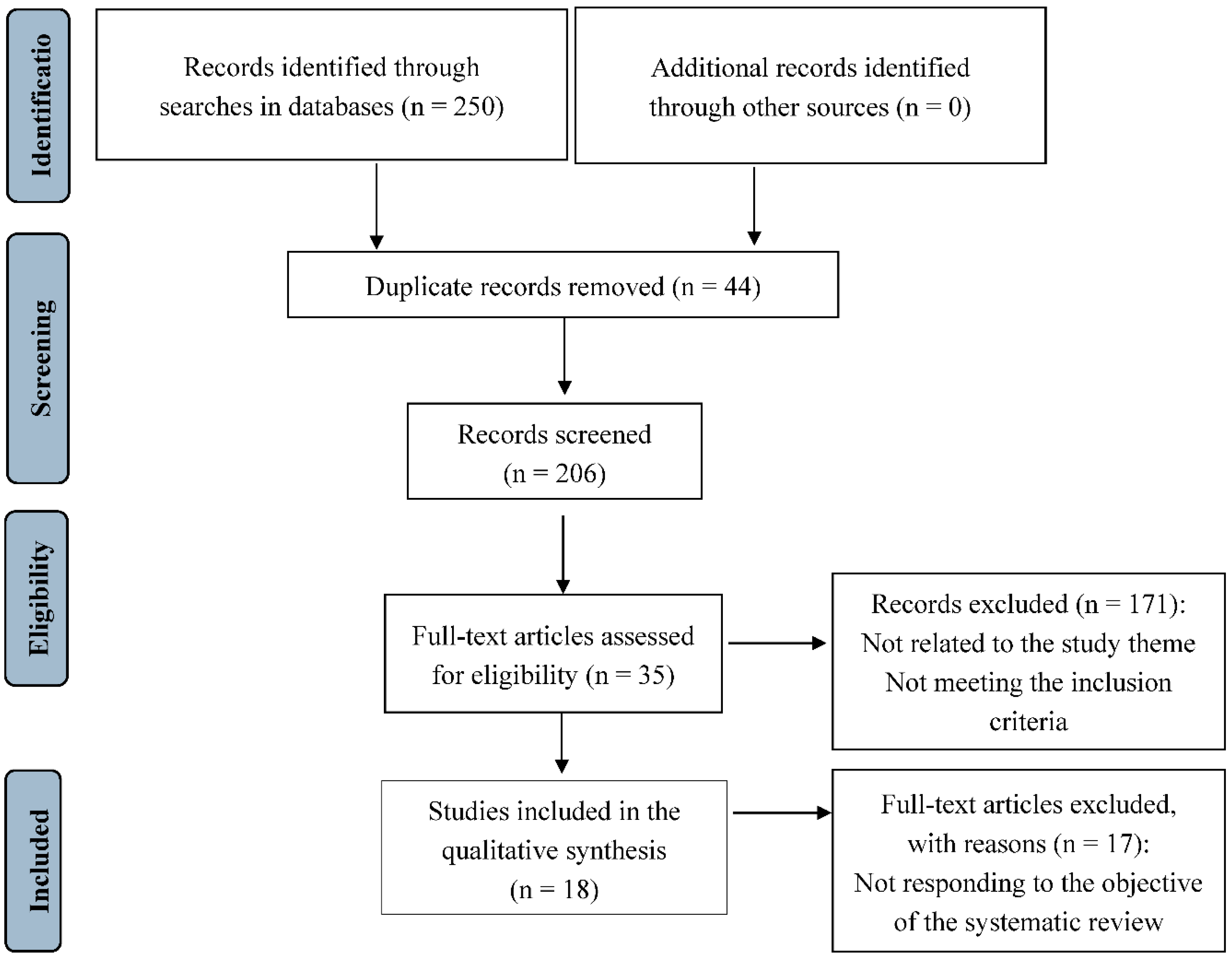

Different international organizations recommend exclusive breastfeeding during the neonate's first six months of life; however, figures of around 38% are reported at the global level. One of the reasons for early abandonment is the mothers' perception of supplying insufficient milk to their newborns. The objective of this research is to assess how mothers' perceived level of self-efficacy during breastfeeding affects their ability to breastfeed and the rates of exclusive breastfeeding up to six months postpartum. A systematic review for the 2000-2023 period was conducted in the following databases: Cochrane, Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Science Direct and CINAHL. Original articles, clinical trials, and observational studies in English and Spanish were included. The results comprised 18 articles in the review (2006-2023), with an overall sample of 2004 participants. All studies were conducted in women who wanted to breastfeed, used the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale or its short version to measure postpartum self-efficacy levels, and breastfeeding rates were assessed up to 6 months postpartum. The present review draws on evidence suggesting that mothers' perceived level of self-efficacy about their ability to breastfeed affects rates of exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months postpartum. High levels of self-efficacy are positively related to the establishment and maintenance of exclusive breastfeeding; however, these rates decline markedly at 6 months postpartum.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Measuring Instruments and Interval

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Self-Efficacy Levels Perceived by the Mothers About Their Ability to Breastfeed

3.5. Self-Efficacy and Exclusive Breastfeeding Rates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics. 2012, 129, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Project on Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe. Protection, promotion and support of breast-feeding in Europe: A blueprint for action (revised). European Union Project. 2008, pp. 39–46.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Exclusive breastfeeding for six months best for babies everywhere. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2011/breastfeeding_20110115/en/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (WHO). Metas mundiales de nutrición 2025: Documento normativo sobre lactancia materna. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255731/WHO_NMH_NHD_14.7_spa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Chowdhury, R.; Sinha, B.; Sankar, M.J.; Taneja, S.; Bhandari, N.; et al. Breastfeeding and Maternal Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Jackson, J. "Breastfeeding Knowledge and Intent to Breastfeed". Clinical Lactation. 2016, 7(2), 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, F.; Kendall, S.; Mead, M. "Breastfeeding support - the importance of self-efficacy for low-income women". Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2010, 6(3), 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, L.L.; Ip, W.Y.; Chan, W.C.S. "Predictors of breast feeding self-efficacy in the immediate postpartum period: A cross-sectional study". Midwifery. 2016, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Abreu, L.M.; Filipini, R.; Alves, B.D.C.A.; da Veiga, G.L.; Fonseca, F.L.A. Evaluation of Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy of Puerperal Women in Shared Rooming Units. Heliyon. 2018, 4, e00900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.S.; Alexander, D.D.; Krebs, N.F.; Young, B.E.; Cabana, M.D.; et al. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodt, R.C.M.; Ximenes, L.B.; Oriá, M.O.B. "Validação de álbum seriado para promoção do aleitamento materno". Acta Paulista de Enfermagem. 2012, 25, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, E.E.; McLellan, J.; Dombrowski, S.U. "Is being resolute better than being pragmatic when it comes to breastfeeding? Longitudinal qualitative study investigating experiences of women intending to breastfeed using the Theoretical Domains Framework". Journal of Public Health (United Kingdom) 2017, 39(3), 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraishi, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Kurihara, S.; Iwamoto, M.; Shimada, M. "Post-breastfeeding stress response and breastfeeding self-efficacy as modifiable predictors of exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum: a prospective cohort study". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2020, 20(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vila-Candel, R.; Soriano-Vidal, F. J.; Murillo-Llorente, M.; Pérez-Bermejo, M.; Castro-Sánchez, E. Mantenimiento de la lactancia materna exclusiva a los 3 meses posparto: experiencia en un departamento de salud de la Comunidad Valenciana. Atención Primaria 2019, 51, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Human Agency in Social Cognitive Theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L. Theoretical Underpinnings of Breastfeeding Confidence: A Self-Efficacy Framework. J. Hum. Lact. 1999, 15, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dégrange, M.; Delebarre, M.; Turck, D.; et al. Les Mères Confiantes en Elles Allaitent-elles Plus Longtemps Leur Nouveau-né? Arch. Pediatr. 2015, 22, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efrat, M. W. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and Level of Acculturation among Low-Income Pregnant Latinas. International Journal of Child Health and Nutrition. 2018, 7, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki-Saghooni, N.; Amel, M.; Karimi, F.Z. Investigation of the relationship between social support and breastfeeding self-efficacy in primiparous breastfeeding mothers. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 3097–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- W, S.V.; Chen, S.C.; Liu, H.Y.; Lee, H.L.; Lin, Y.E. Knowledge, Intention, and Self-Efficacy Associated with Breastfeeding: Impact of These Factors on Breastfeeding during Postpartum Hospital Stays in Taiwanese Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 9,18, 5009. [Google Scholar]

- Awaliyah, S.N.; Rachmawati, I.N.; Rahmah, H. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy as a Dominant Factor Affecting Maternal Breastfeeding Satisfaction. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockway, M.; Benzies, K.; Hayden, K.A. Interventions to Improve Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and Resultant Breastfeeding Rates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Hum. Lact. 2017, 33, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.Y.; Ip, W.Y.; Choi, K.C. The Effect of a Self-Efficacy-Based Educational Programme on Maternal Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy, Breastfeeding Duration and Exclusive Breastfeeding Rates: A Longitudinal Study. Midwifery. 2016, 36, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yepes-Nuñez, J. J.; Urrútia, G.; Romero-García, M.; Alonso-Fernández, S. Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- López de Argumedo, M.; Reviriego, E.; Gutiérrez, A.; Bayón, J. C. Actualización del Sistema de Trabajo Compartido para Revisiones Sistemáticas de la Evidencia Científica y Lectura Crítica (Plataforma FLC 3.0). 2017. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Servicio de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias del País Vasco.

- Noel-Weiss, J.; Rupp, A.; Cragg, B.; Bassett, V.; Woodend, A.K. Randomized controlled trial to determine effects of prenatal breastfeeding workshop on maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy and breastfeeding duration. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2006, 35, 616–624. [Google Scholar]

- Awano, M.; Shimada, K. Development and evaluation of a self care program on breastfeeding in Japan: A quasi-experimental study. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2010, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQueen, K. A.; Dennis, C. L.; Stremler, R.; Norman, C. D. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention with primiparous mothers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 2011, 40, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, S.; Abedi, P.; Hasanpoor, S.; Bani, S. The effect of interventional program on breastfeeding self-efficacy and duration of exclusive breastfeeding in pregnant women in Ahvaz, Iran. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2014, 19, 510793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassman, M. E.; McKearney, K. .; Saslaw, M.; Sirota, D. R. Impact of breastfeeding self-efficacy and sociocultural factors on early breastfeeding in an urban, predominantly Dominican community. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2014, 9, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, K.; Taguri, M.; Dennis, C. L.; Wakutani, K.; Awano, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Jimba, M. Effectiveness of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention: do hospital practices make a difference? Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2014, 18, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. S.; Hu, J.; McCoy, T. P.; Efird, J. T. The effects of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention on short-term breastfeeding outcomes among primiparous mothers in Wuhan, China. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2014, 70, 1867–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henshaw, E. J.; Fried, R.; Siskind, E.; Newhouse, L.; Cooper, M. Breastfeeding self-efficacy, mood, and breastfeeding outcomes among primiparous women. Journal of Human Lactation 2015, 31, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.Y.; Ip, W.Y.; Choi, K.C. The effect of a self-efficacy-based educational programme on maternal breast feeding self-efficacy, breast feeding duration and exclusive breast feeding rates: A longitudinal study. Midwifery. 2016, 36, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, W.Y.; Gao, L.L.; Choi, K.C.; Chau, J.P.; Xiao, Y. The Short Form of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale as a Prognostic Factor of Exclusive Breastfeeding among Mandarin-Speaking Chinese Mothers. J Hum Lact. 2016, 32, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araban, M.; Karimian, Z.; Kakolaki, Z. K.; McQueen, K. A.; Dennis, C. L. Randomized controlled trial of a prenatal breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention in primiparous women in Iran. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 2018, 47, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shariat, M.; Abedinia, N.; Noorbala, A. A.; Zebardast, J.; Moradi, S. Breastfeeding self-efficacy as a predictor of exclusive breastfeeding: A clinical trial. Iranian Journal of Neonatology 2018, 9, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- De Roza, J.G.; Fong, M.K.; Ang, B.L.; Sadon, R.B.; Koh, E.Y.L.; Teo, S.S.H. Exclusive breastfeeding, breastfeeding self-efficacy and perception of milk supply among mothers in Singapore: A longitudinal study. Midwifery. 2019, 79, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, J.F.; Chen, S.R.; Au, H.K.; Chipojola, R.; Lee, G.T.; Lee, P.H.; Shyu, M.L.; Kuo, S.Y. Effectiveness of an integrated breastfeeding education program to improve self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding rate: A single-blind, randomised controlled study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020, 111, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakilian, K.; Farahani, O.C.T.; Heidari, T. Enhancing Breastfeeding - Home-Based Education on Self-Efficacy: A Preventive Strategy. Int J Prev Med 2020, 3;11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.V.; Chen, S.C.; Liu, H.Y.; Lee, H.L.; Lin, Y.E. Knowledge, Intention, and Self-Efficacy Associated with Breastfeeding: Impact of These Factors on Breastfeeding during Postpartum Hospital Stays in Taiwanese Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 9;18, 5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.S.; Chien, W.T. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of an Online Educational Program for Primiparous Women to Improve Breastfeeding. J Hum Lact. 2023, 39, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesil, Y.; Ekşioğlu, A.; Turfan, E. C. The effect of hospital based breastfeeding group education given early perinatal period on breastfeeding self-efficacy and breastfeeding status. Journal of Neonatal Nursing. 2023, 29, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C. L.; Faux, S. Development and psychometric testing of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale. Res. Nurs. Health. 1999, 22, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C. L. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: Psychometric assessment of the short form. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, A.; Penrose, K.; Morrison, C.; Dennis, C.L.; MacArthur, C. Psychometric properties of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form in an ethnically diverse U.K. sample. Public Health Nurs. 2008, 25, 278–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husin, H.; Isa, Z.; Ariffin, R.; Rahman, S. A.; Ghazi, H. F. The Malay version of antenatal and postnatal breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form: Reliability and validity assessment. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2017, 17, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ip, W.Y.; Yeung, L.S.; Choi, K.C.; Chair, S.Y.; Dennis, C.L. Translation and validation of the Hong Kong Chinese version of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form. Res Nurs Health. 2012, 35, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarter-Spaulding, D.E.; Dennis, C.L. Psychometric testing of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form in a sample of Black women in the United States. Res Nurs Health. 2010, 33, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Roig, A.; d'Anglade-González, M.L.; García-García, B.; Silva-Tubio, J.R.; Richart-Martínez, M.; Dennis, C.L. The Spanish version of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form: reliability and validity assessment. Int J Nurs Stud 2012, 49, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubaran, C.; Foresti, K.; Schumacher, M.; Thorell, M.R.; Amoretti, A.; Müller, L.; Dennis, C.L. The Portuguese version of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form. J Hum Lact. 2010, 26, 26,297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuthill, E.L.; McGrath, J.M.; Graber, M.; Cusson, R.M.; Young, S.L. Breastfeeding Self-efficacy: A Critical Review of Available Instruments. J Hum Lact. 2016, 32, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dégrange, M.; Delebarre, M.; Turck, D.; Mestdagh, B.; Storme, L.; Deruelle, P.; Rakza, T. Les mères confiantes en elles allaitent-elles plus longtemps leur nouveau-né? [Is self-confidence a factor for successful breastfeeding?]. Arch Pediatr. 2015, 22, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki, A.; Faghihzadeh, E.; Youseflu, S. The Effect of Educational Intervention on Improvement of Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2021, 10, 5522229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipojola, R.; Chiu, H.Y.; Huda, M.H.; Lin, Y.M.; Kuo, S.Y. Effectiveness of theory-based educational interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020, 109, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gallego, I.; Corrales-Gutierrez, I.; Gomez-Baya, D.; Leon-Larios, F. Effectiveness of a Postpartum Breastfeeding Support Group Intervention in Promoting Exclusive Breastfeeding and Perceived Self-Efficacy: A Multicentre Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2024, 16, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartle, N.C.; Harvey, K. Explaining infant feeding: The role of previous personal and vicarious experience on attitudes, subjective norms, self-efficacy, and breastfeeding outcomes. Br J Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodou, H.D.; Bezerra, R.A.; Chaves, A.F.L.; Vasconcelos, C.T.M.; Barbosa, L.P.; Oriá, M.O.B. Telephone intervention to promote maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy: randomized clinical trial. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2021, 15, e20200520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piro, S.S.; Ahmed, H.M. Impacts of antenatal nursing interventions on mothers' breastfeeding self-efficacy: an experimental study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Participants | Puerperal women who wanted to breastfeed. |

| Intervention | Individual or group intervention or program carried out to promote and support BSES and BF rates. Also, monitoring of breastfeeding progress. |

| Comparison | Puerperal women with high and low levels of SE, respectively. Usual care. |

| Outcome | EBF rates up to 6 months postpartum. |

| Database | Strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| CINAHL | ((TITLE “self efficacy”) AND (TITLE (breastfeeding OR lactation OR "exclusive breastfeeding")) AND (ABSTRACT "breastfeeding rate")) ((ABSTRACT (“self confidence” OR “self reliance”)) AND (ABSTRACT ((breastfeeding OR lactation OR "exclusive breastfeeding")) AND (ABSTRACT "breastfeeding rate")) |

11 |

| COCHRANE | "self efficacy" in Title AND (breastfeeding OR lactation OR "exclusive breastfeeding") in Title Summary Keyword AND "breastfeeding rate" in Title Summary Keyword | 15 |

| PUBMED | ("self efficacy"[Title]) AND ((breastfeeding OR lactation OR "exclusive breastfeeding")) AND ("breastfeeding rate") | 12 |

| SCIENCE DIRECT | self efficacy” (Tittle) AND (breastfeeding OR lactation OR “exclusive breastfeeding”) AND ”breastfeeding rate” (“self confidence” OR “self reliance”) AND (breastfeeding OR lactation OR “exclusive breastfeeding”) AND ”breastfeeding rate |

127 |

| SCOPUS | (TITLE (“self efficacy”) AND TITLE ((breastfeeding OR lactation OR "exclusive breastfeeding")) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“breastfeeding rate”)) (TITLE ((“self confidence” OR “self reliance”)) AND TITLE ((breastfeeding OR lactation OR "exclusive breastfeeding")) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("breastfeeding rate")) |

37 |

| WEB OF SCIENCE | self efficacy” (Topic) AND (breastfeeding OR lactation OR “exclusive breastfeeding”) (Topic) AND ”breastfeeding rate” (Topic) (“self confidence” OR “self reliance”) (Topic) AND (breastfeeding OR lactation OR “exclusive breastfeeding”) (Topic) AND ”breastfeeding rate” (Topic) |

48 |

| Author, (Year) | Objetive | Design | Participants | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noel-Weiss, J. et al. (2006) [29] | To determine the effects of a prenatal breastfeeding workshop on maternal BSE and BF duration. | Randomized controlled trial | Primparous women | 110 |

| Awano, M & Shimada, K. (2010) [30] | To develop a self-care programme for BF aimed at increasing mothers' breastfeeding confidence and to evaluate its effectiveness. | Quasi-experimental | Primiparous women | 117 |

| McQueen, K.A. et al. (2011) [31] | To pilot test a newly developed BSE intervention. | Randomized controlled trial | Primiparous women | 149 |

| Ansari, S. et al. (2014) [32] | To determine the effect of an educational programme on BSE and the duration of EBF in pregnant women. | Randomized controlled trial | Primiparous women | 120 |

| Glassman, M.E. et al. (2014) [33] | To quantify early changes in amounts of BF and to explore the role of BSE and sociocultural factors associated with any BF and EBF in the first 4–6 weeks postpartum. | Observational and descriptive | Primiparous and multiparous women | 209 |

| Otsuka, K. et al. (2014) [34] | To evaluate the effect of an SE intervention on BSE and EBF. | Clinical trial | Primiparous and multiparous women | 781 |

| Wu, D.S. et al. (2014) [35] | To evaluate the effects of a breastfeeding intervention on primiparous mothers' BSE, BF duration, and exclusivity at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum. | Randomized clinical trial | Primiparous women | 74 |

| Henshaw, E.J. et al. (2015) [36] | To evaluate the relationship among BSE, mood, and breastfeeding outcomes in primiparous women. A secondary purpose was to explore self-reported reasons for difficult emotional adjustment during the transition to motherhood. | Prospective study | Primiparous women | 146 |

| Chan, M.Y. et al. (2016) [37] | To investigate the effectiveness of a self-efficacy-based breast feeding educational programme (SEBEP) in enhancing BSE, BF duration, and EBF rates. |

Clinical trial | Primiparous women | 71 |

| Ip, W.Y. et al. (2016) [38] | To examine the relative effect of maternal BSE and selected relevant factors on the EBF rate at 6 months postpartum. | Cohort study | Primiparous and multiparous women | 562 |

| Araban, M. et al. (2018) [39] | To determine the effects of a prenatal BSE intervention on BSE and BF outcomes. | Randomized controlled trial | Primiparous women | 120 |

| Shariat, M. et al. (2018) [40] | To examine the effect of the interventions leading to increased awareness, knowledge, and SE regarding EBF and duration of BF. | Randomized clinical trial | Primiparous and multiparous women | 129 |

| De Roza, J.G. et al. (2019) [41] | To examine the factors that affect EBF. | Observational and descriptive study | Primiparous and multiparous women | 400 |

| Tseng, J.F. et al. (2020) [42] | To develop an integrated BF education programme based on SE theory, and evaluate the effect of the intervention on first-time mothers' BSE and attitudes. | Randomized clinical trial | Primiparous women | 93 |

| Vakilian, K. et al. (2020) [43] | To evaluate the effects of home-based education intervention on the exclusivity and promoting the rates of BSE. | Randomized clinical trial | Primiparous women | 130 |

| Wu, S.F.V. et al. (2021) [44] | To assess women's intention to breastfeed and knowledge and SE regarding BF following childbirth, and to identify the factors associated with postpartum breastfeeding during women's hospital stays. | Descriptive and longitudinal study with pre-/post-test | Primiparous and multiparous women | 120 |

| Wong, M.S. & Chien, W.T. (2023) [45] | To examine the effects of different approaches to educational and supportive interventions that can help sustain BF and improve BSE for primiparous postnatal women; and to identify key characteristics of the effective interventions in terms of delivery time, format and mode, main components, use of theoretical framework, and number of sessions | Randomized clinical trial | Primiparous women | 30 |

| Yesil, Y. et al. (2023) [46] | To examine the effect of hospital-based group BF education provided to mothers before discharge from the hospital on mothers’ SE and on the increase of BF rates | Randomized clinical trial | Primiparous and multiparous women | 80 |

| Author, (Year) | Country | Design | Tool to Assess SE | Assessment of the EBF Rates | Main Results | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noel-Weiss, J. et al. (2006) [29] | Canada | Randomized controlled trial | BSES-SF | 4 and 8 weeks postpartum | SE scores increased in both groups at 4 and 8 weeks. These SE scores positively correlated with the maintenance of EBF, with the mean EBF rate of both groups being 68% at 8 weeks. | Medium |

| Awano, M & Shimada, K. (2010) [30] | Japan | Quasi-experimental | BSES-SF | Early postpartum and 4 weeks postpartum | The BSES-SF score in the IG increased significantly from 3.8 to 49.9 one month after birth (p<0.01), unlike the CG (p=0.03). The early postpartum BF rate was similar in both groups; however, at 4 weeks postpartum, the EBF rate was significantly reduced to 65% in the CG when compared to 90% in the IG (p=0.02). | Medium |

| McQueen, K.A. et al. (2011) [31] | Canada | Randomized controlled trial | BSES-SF | 4 and 8 weeks postpartum | Scores for SE were high in both the IG (59 points) and the CG (54.9 points). This had an impact on EBF rates, keeping them above 65% in both groups at 8 weeks postpartum. Additionally, the mothers' prior intention to breastfeed influenced the results. | High |

| Ansari, S. et al. (2014) [32] | Iran | Randomized controlled trial | BSES | 6 months postpartum | SE increased significantly in the IG when compared to the CG 1 month after birth (p<0.001). EBF duration was significantly longer in the IG (p<0.001). There was a significant relationship between SE and EBF duration (p<0.001). | Medium |

| Otsuka, K. et al. (2014) [34] | Japan | Clinical trial | BSES-SF | Early postpartum, and 4 and 12 weeks postpartum | In the IG there were improvements both in SE up to 4 weeks postpartum (p=0.037) and in the EBF rate at 4 weeks postpartum (ORadj=2.32, 95% CI=1.01–5.33), unlike the CG. Higher scores in the BSES-SF scale—and therefore higher SE levels—were related to better results in the EBF rates. | Low |

| Wu, D.S. et al. (2014) [35] | China | Randomized clinical trial | BSES-SF | 4 and 8 weeks postpartum | The IG obtained significantly higher SE scores and better EBF rates than the CG (p<0.01) at 4 and 8 weeks. The women with higher SE levels were more prone to the EBF practice at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum (p<0.01). Differences were found in both groups in BF duration at 8 weeks (p=0.047), though not at 4 weeks (p=0.11). | |

| Chan, M.Y. et al. (2016) [37] | China | Clinical trial | BSES-SF | 2, 4, and 8 weeks and 6 months postpartum | SE exerted an influence on the EBF rates, which were higher in the IG than in the CG at 2 weeks (p<0.01). There were no significant differences between the groups for BF duration at 6 months (p=0.07) | Medium |

| Araban, M. et al. (2018) [39] | Iran | Randomized controlled trial | BSES-SF | 8 weeks postpartum | EBF rates and self-efficacy scores were higher in the IG than in the CG at 8 weeks postpartum. There is clear evidence that increasing SE levels improves EBF rates. | High |

| Shariat, M. et al. (2018) [40] | Iran | Randomized clinical trial | BSES | Early postpartum, and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months postpartum | Although there were no significant differences in the BSES scores between the groups (p=0.09), SE exerted a positive and significant effect on EBF duration, which was significantly longer in the IG than in the CG at 6 months (p<0.01). The higher the SE levels, the more EBF was extended. | High |

| Tseng, J.F. et al. (2020) [42] | Taiwan | Randomized clinical trial | BSES-SF | 1 week, and1, 3, and 6 months postpartum | The EBF rates were higher in all the IG participants, where the BSES-SF scores were also significantly better than in the CG at 1 week, 1 month and 3 months postpartum (p<0.01), with a positive relationship between SE levels and EBF duration. There were no significant differences at 6 months postpartum. | High |

| Vakilian, K. et al. (2020) [43] | Iran | Randomized clinical trial | BSES-SF | Early postpartum, and 1 month postpartum | There were no differences between the groups regarding the SE level in early postpartum. However, the BSES-SF scores in the IG were higher after 1 month postpartum (p=0.01), as well as the EBF rate (p=0.01). | High |

| Wong, M.S. & Chien, W.T. (2023) [45] | China | Randomized clinical trial | BSES-SF | 2 months postpartum | Only 50% of the mothers in both groups EBF at 2 months postpartum. BSE scores were low in both groups (43.2 IG; 42.9 CG), which may have influenced the EBF rates. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic also had an impact. | High |

| Yesil, Y. et al. (2023) [46] | Turkey | Randomized Clinical trial | BSES | Early postpartum, and 4 and 12 weeks postpartum | EBF rates were higher in the IG at birth compared to the CG (70% vs 30%). EBF rates were maintained in the IG but not in the CG. | High |

| Author, (Year) | Country | Design | Tool to Assess SE | Assessment of the EBF Rates | Main Results | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glassman, M.E. et al. (2014) [33] | United States | Observational and descriptive | BSES-SF | 4-6 weeks postpartum | Higher SE levels were associated with higher EBF rates at 4-6 weeks postpartum (ORadj=1.18 (1.05, 1.32), where SE was a factor that presented a positive association with EBF. | Medium |

| Henshaw, E.J. et al. (2015) [36] | United States | Prospective study | BSES-SF | Early postpartum, 6 weeks and 6 months | Women's mood was related to the BSE levels, which, in turn, were associated with EBF continuity—i.e., better mood was positively related to higher SE scores and, in turn, with better success rates in EBF continuity at 6 months postpartum (p<0.01). | High |

| Ip, W.Y. et al. (2016) [38] | China | Cohort study | BSES-SF | Early postpartum, 1, 4, and 12 weeks postpartum | The mothers showed low SE levels with only 47.3 points on the BSES-SF. As a result, EBF rates were only 24.6% at birth, while at 6 months almost no mother was exclusively BF, with a rate of just 0.2%. | High |

| De Roza, J.G. et al. (2019) [41] | Singapore | Observational and descriptive study | BSES-SF | 3 and 6 months | The BSES-SF scores were significantly higher in the mothers who continued EBF at 3 and 6 months, when compared to those who interrupted breastfeeding (p<0.01). | |

| Wu,S.F.V. et al. (2021) [44] | Taiwan | Descriptive and longitudinal study with pre-/post-test | BSES-SF | 30-34 gestational weeks Early postpartum |

The mean SE score was 41.55 (SD=12.09). Among the factors that exerted an influence on BF and EBF duration during postpartum, SE presented a statistically significant difference (p<0.05). SE was one of the significant characteristics among the women who chose to breastfeed during the postpartum period and those who did not (p=0.011) | High |

| Author, (Year) | Variables Measured | Instruments | Reliability and Validity of Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noel-Weiss, J. et al. (2006) [29] | SE and EBF at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum | BSES-SF | Original version of BSES-SF scale. Cronbach's Alpha 0.94 |

| Awano, M & Shimada, K. (2010) [30] | SE, BF, and EBF in early postpartum and 4 weeks postpartum | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale to Japan. Cronbach's Alpha 0.94 |

| McQueen, K.A. et al. (2011) [31] | SE and EBF at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum | BSES-SF | Original version of BSES-SF scale. Cronbach's Alpha 0.94 |

| Ansari, S. et al. (2014) [32] | SE and EBF at 6 months postpartum | BSES | Adaptation and validation BSES scale to Persian. Cronbach's Alpha 0.82 |

| Glassman, M.E. et al. (2014) [33] | SE and EBF | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale to Portuguese. Cronbach's Alpha 0.71 |

| Otsuka, K. et al. (2014) [34] | SE and EBF in early postpartum, and 4 and 12 weeks postpartum | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale to Japanese. Cronbach's Alpha 0.95 |

| Wu, D.S. et al. (2014) [35] | SE, BF, and EBF at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale Chinese. Cronbach's Alpha 0.89 |

| Henshaw, E.J. et al. (2015) [36] | SE and EBF | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale to USA population. Cronbach's Alpha 0.92 |

| Chan, M.Y. et al. (2016) [37] | SE, BF, and EBF at 4 and 8 weeks and 6 months postpartum | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale to Hong Kong Chinese. Cronbach's Alpha 0.89 |

| Ip, W.Y. et al. (2016) [38] | SE and EBF | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale to Chinese. Cronbach's Alpha 0.89 |

| Araban, M. et al. (2018) [39] | SE and EBF at 8 weeks postpartum | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale to Persian. Cronbach's Alpha 0.91 |

| Shariat,M. et al. (2018) [40] | SE and EBF in early postpartum, and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months postpartum | BSES | Adaptation and validation of the BSES scale to the population of Tehran. Cronbach's Alpha 0.82 |

| De Roza, J.G. et al. (2019) [41] | SE and EBF | BSES-SF | Original version of BSES-SF scale. Cronbach's Alpha 0.94 |

| Tseng, J.F. et al. (2020) [42] | SE and EBF at 1 week, and1, 3, and 6 months postpartum | BSES-SF | The Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the Taiwanese version of BSES-SF was 0.95. The Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.93 |

| Vakilian, K. et al. (2020) [43] | SE and EBF in early postpartum, and 1 month postpartum | BSES | Persian version of BSES scale. Cronbach’s alpha 0.89 |

| Wu, S.F.V. et al. (2021) [44] | SE and EBF | BSES-SF | Adaptation and validation BSES-SF scale Chinese. Cronbach's Alpha 0.89 |

| Wong, M.S. & Chien, W.T. (2023) [45] | SE and EBF at 2 months postpartum | BSES-SF | Hong Kong Chinese version of the BSES-SF scale. Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95 |

| Yesil, Y. et al. (2023) [46] | SE and EBF in early postpartum, and 4 and 12 weeks postpartum | BSES | Turkish adaptation and validation of BSES scale. Cronbach's Alpha 0.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).