1. Introduction

Breastfeeding is well-recognised as the best nutrition for infants [

1,

2,

3], providing both mother and infant with numerous health benefits and long-term advantages [

1,

4,

5,

6]. Human breast milk is specifically adapted to the infants’ biological requirements and is the optimal source of sustenance for infants [

2]. Breastfeeding protects against diarrhoea and common childhood illnesses such as pneumonia, can have longer-term advantages, like lowering the risk of childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity [

1,

7,

8,

9], and provides necessary support for the developing immune system [

10,

11]. Exclusive breastfeeding is related to low levels of morbidity [

9,

12] and fewer hospitalisations [

13]. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States (CDC) consider breastfeeding as the optimal nutrition for infants [

14].

Similar to its protective effects against various diseases in infants, it has several benefits for mothers, including reducing the incidence of premenopausal breast cancer and ovarian cancer in mothers [

15,

16]. Women who breastfeed have a lower risk of developing breast cancer, type 2 diabetes, ovarian cancer, heart disease, osteoporosis, and postpartum depression [

4,

7,

17].

Additional benefits of breastfeeding include economic advantages. Breastmilk is less expensive than formula; due to its natural secretion from the mother's body, breastmilk is free and always available. There is no need to pay for, prepare or store breast milk as opposed to formula. Formula feeding generates extra costs: formula, bottles, sterilising equipment, and, in exceptional cases, special types of formula for allergic babies or those with specific dietary needs. In fact, most often, through breastfeeding, families avoid these expenses, and therefore, it is more economical and accessible [

18,

19,

20].

Nonetheless, infant formula is still a healthy alternative for mothers who cannot or decide not to breastfeed. While it provides babies with the nutrients they need to grow and thrive, its benefits are still fewer than those of breast milk [

21]; therefore, manufacturers have proposed a diverse range of new ingredients in an effort to develop formulas that mimic the perceived and potential advantages of human milk [

22].

Differences in participants' attitudes toward breastfeeding can be attributed to cultural norms [

23,

24,

25], societal expectations, social networks [

26], personal experiences [

27,

28], and exposure to breastfeeding education [

29]. In certain societies, breastfeeding is seen as a duty for all mothers [

30,

31,

32], while in some others, formula feeding is accepted as an alternative [

33,

34]. Additionally, media representation, healthcare recommendations, and prior exposure to breastfeeding within one’s social environment play a significant role in shaping attitudes [

25,

35].

Some countries like Korea and Albania have high exclusive breastfeeding rates, with almost 71% and 62% respectively, according to UNICEF data. While in the United States, for example, exclusive breastfeeding until five months is only 26% [

36].

The prevalence of breastfeeding in Hungary is 53.9%, while exclusive breastfeeding was 25.1% [

37]. These numbers are higher than in the WHO European Region, which has some of the lowest rates of exclusive breastfeeding, with just 13% of infants exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months. [

38]

Education can impact students’ perspectives in terms of breastfeeding knowledge, resulting in more evidence-based views [

29], while those with limited information may rely on societal norms or personal opinions [

39]. These variations highlight the interplay between cultural, social, and educational factors in shaping attitudes toward infant feeding.

Although studies documenting breastfeeding attitudes have been reported previously in a range of settings [40-44], this is the first time, to our knowledge, that the comparison in attitudes between Syrian and Hungarian female university students has been assessed using the IIFAS scale.

This study aims to understand how attitudes influence mothers’ final decisions. Focusing on university students who represent future parents helps to understand the young generation's attitude towards breastfeeding, providing insights into how cultural and educational factors impact breastfeeding beliefs, which may be helpful for international public health initiatives.

This study fills a gap by comparing two distinct populations, Syrian and Hungarian university students, who differ in cultural norms, healthcare exposure, and social expectations Exploring these differences can also inform future interventions that address misconceptions, promote breastfeeding awareness, and support women’s choices in distinct cultural contexts.

2. Materials and Methods[40–44

2.1. Participants

The survey was conducted in Syria and Hungary in two phases. The first phase occurred at Damascus University in October and November 2022, with a sample of 317 female students. The second phase was conducted in Budapest, Hungary, during April and May 2023, involving 303 Semmelweis University and Eötvös Loránd University students (

Table 1). To ensure linguistic accuracy, the questionnaire was administered exclusively in paper format in the native languages of each country: Arabic and Hungarian. Independent professional translators translated the survey from English to Arabic and Hungarian using the back-translation method.

2.2. Study Design

This research is part of an extensive survey using a multi-section questionnaire with three modules. The present study investigates the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS)

[1], which is a widely used tool designed to assess attitudes about infant feeding methods, including breastfeeding and formula feeding, developed by De La Mora and Russell in 1999 [

45]. The scale evaluates individuals' beliefs and preferences regarding infant feeding practices. Participants were required to read the statements and choose the most appropriate response from a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree, with the “not sure" option provided.

2.3. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Samples

This study utilised a questionnaire to collect data on participants' socio-demographic characteristics, including nationality, gender, birth year, parental education levels, marital status, permanent residency, and wealth index. Additionally, participants' current level of education was recorded (

Table 2).

Comparing the Hungarian and the Syrian samples revealed significant differences in several socio-economic dimensions. In terms of educational level, a larger percentage of Syrians (79.5%) had a BSc degree than Hungarians (57.1%), while Hungarians had a higher percentage of MSc degrees (37.0% vs. 14.2%). Differences were less marked in parental education, with similar percentages of fathers (40.6% Hungarian, 45.7% Syrian) and mothers (45.9% Hungarian, 47.0% Syrian) having a university degree. By place of residence, a significantly higher percentage of Syrian respondents lived in an urban neighbourhood (82.3%) than Hungarians (63.9%). Marital status presented a marked difference: while almost all Hungarian respondents were unmarried (99.7%), more than half of Syrian respondents (53.6%) were married. The wealth indicator showed the greatest imbalance: almost all Hungarians (97.4%) said they had "enough" income, while two-thirds of Syrians (66.8%) said they had "less than enough" for their necessities. Finally, the distribution of age showed that most respondents in both groups were in the younger age category (21-25 years).

The samples from the two countries were nearly balanced regarding nationality, with 51.0% Syrian and 49.0% Hungarian respondents. All participants were female, with the majority, 68.3%, enrolled in bachelor's programs, 25.0% pursuing master's degrees, and a smaller proportion, 6.0%, engaged in PhD studies.

2.4. Measurements

The methodology for this study utilised a statistical analysis with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software. Data analysis was carried out using the Predictive Analysis Software (PASW 18, formerly known as SPSS). Statistical procedures were completed at a significance level of 5%. Descriptive statistics were performed for demographic variables, scale scores, and the responses to all statements within each scale.

3. Results

The findings of this study regarding the comparison between Hungarian and Syrian students present the distribution of responses to the IIFAS, highlighting their attitudes toward breastfeeding (

Table 3).

3.1. Agreement and Disagreement

The most vigorous agreement was in the statement discussing whether breastfeeding boosts the connection between mother and infant; it can be observed that 95.7% of participants agree with this statement (

Table 3). Similarly, 87.9% agreed that breast milk is the ideal food for babies. Likewise, slightly fewer, but still 62.0% of participants, agreed that breastfed babies are healthier than formula-fed babies.

The disagreements among students were shown in many statements; 67.2% of participants disagreed that the formula is more suitable or comfortable than breastfeeding. 66.2% of participants showed disagreement that fathers feel left out if a mother breastfeeds. Regarding the statement related to breastfeeding in public places, participants showed 48.6% disagreement with not breastfeeding publicly.

Many differences emerged in participants' responses, one of which related to the statement that breast milk is more easily digested than formula. While 83.0% of Syrian participants agreed with this statement, only 34.8% of Hungarian participants shared this agreement. Similarly, 77.6% of Syrian participants agreed with the statement that mothers who formula-feed miss one of the great joys of motherhood. In comparison, only 30.7% of Hungarian students agreed with this sentiment.

Hungarian students were notably more uncertain about the statement

“Breast milk is lacking in iron” 71.5% of Hungarian participants were unsure about this claim, while 53.3% of Syrian participants opposed it. Along similar lines, for the two statements about overfeeding, which have opposite meanings, the percentages of participants who selected “not sure” were notably high and comparable across groups. Regarding the statement

“Formula-fed babies are more likely to be overfed than are breastfed babies” 38.9% of participants were unsure, while for

“Breastfed babies are more likely to be overfed than formula-fed babies” 38.1% expressed uncertainty (

Table 3).

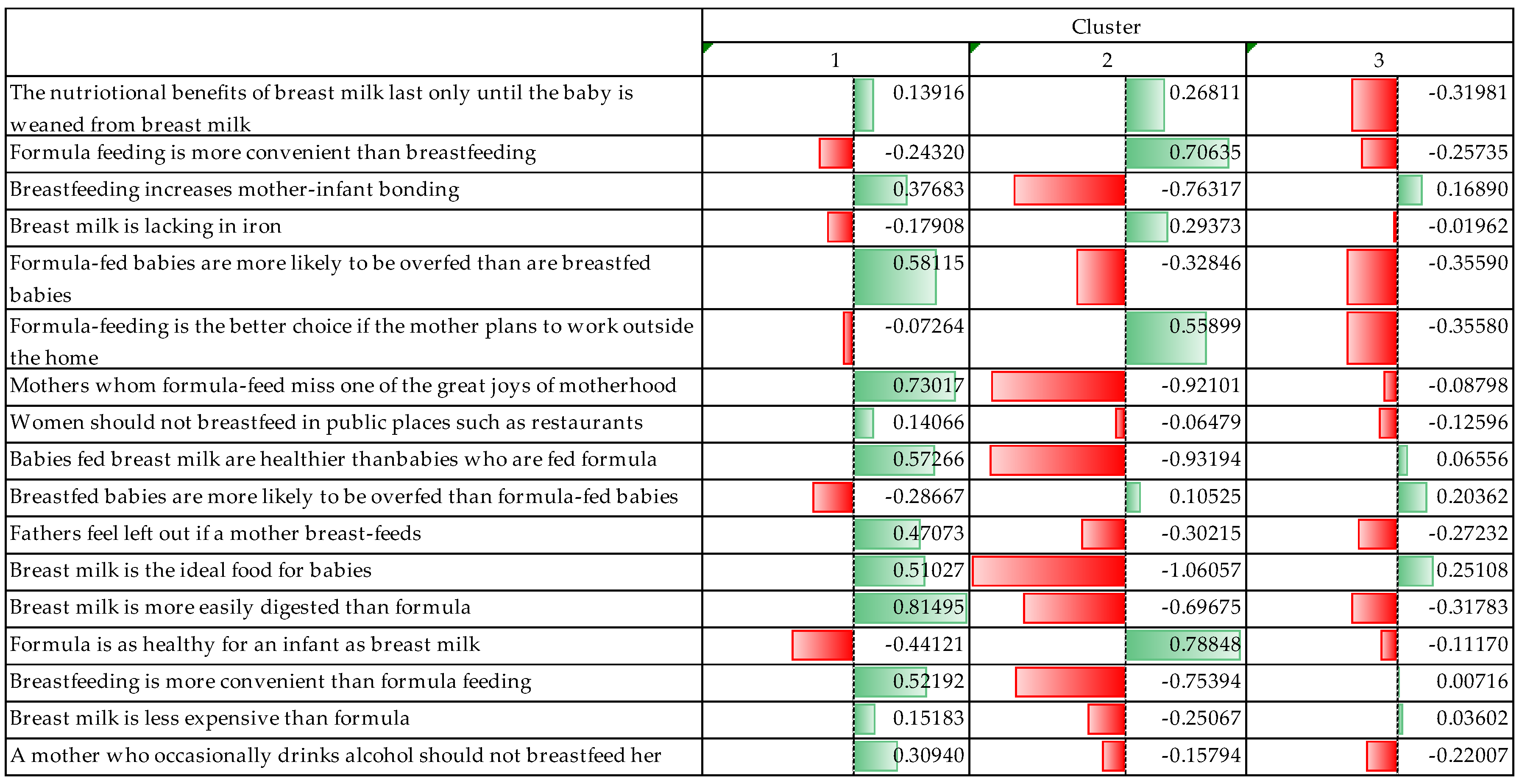

3.2. Cluster Analysis

Based on the attitudes towards breastfeeding and formula feeding, the cluster analysis detected three well-distinct clusters. In the following, the process of cluster formation is firstly described and the description of the clusters that emerged (

Figure 1).

In the process of clustering, it was observed that the groups were well separated, and the differences between the clusters became explicitly clear. The maximum distance between cluster centres was 10.257, meaning the respondents' opinions were explicitly divergent.

The significance level for all variables used for cluster analysis was below 0.05, indicating that the differences between clusters were statistically significant. It could be seen during the process that three variables were explicitly determinant and discriminating factors between the clusters. The three variables were positive statements about breastfeeding: “Mothers who formula feed miss one of the great joys of motherhood” (F = 212.750); “Breast milk is the ideal food for babies” (F = 214.941); “Breast milk is more easily digested than formula” (F = 209.261).

The three clusters had distinct characteristics, and based on these characteristics, each cluster was named, which name is used in the following.

Our first cluster was called “Supporters of breast milk” (SBM). Respondents who belong to this cluster explicitly believed in the benefits of breastfeeding and breast milk. They thought breast milk is ideal for babies. In relation to formula feeding, they rejected the idea that formula is as healthy as breast milk and preferred to see the disadvantages; for example, they believed that formula-fed babies are more likely to be overfed. At the same time, cluster members considered breast milk to be more digestible for babies and breastfeeding a more positive experience for mothers. They did not seem to believe that formula feeding is more convenient, nor did they think of breastfeeding in public as a problematic situation. Furthermore, they did not believe that formula feeding is a better option for working mothers.

The second group was called “Supporters of formula feeding” (SFF). They were those who explicitly accepted the benefits of formula feeding and emphasised the convenience and practicality of formula, especially for mothers returning to work. They did not believe that breast milk makes babies healthier than formula because they believed that the two feeding methods are equally healthy and that by not breastfeeding, a mother is not missing out on an important experience. Even without breastfeeding, they believed that a mother can fully connect with her child and raise it.

The last cluster was called the “Flexible Thinkers” (FT). Respondents in this cluster acknowledged that there are advantages to breast milk, but at the same time, they did not reject formula. They believed that both methods have their advantages and disadvantages. They acknowledged that breast milk is a more natural and healthy food for the baby but rejected extreme pro-breast-milk views. However, they also disagreed with the more extreme pro-formula opinions. Additionally, they did not believe that fathers are missing the experience of raising a child because of breastfeeding. They even favoured breastfeeding but believed that in certain situations it is more practical to use formulas.

Thus, it can be said that in the cluster analysis, the three attitude groups were explicitly distinct on different issues related to breast milk and infant formula. SFF strongly believed in the benefits of breast milk and rejected formulas. SFF believed that formulas are more convenient and healthier. Those with a flexible approach took a balanced view, accepting both methods in certain circumstances.

3.3. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Groups Defined by Attitudinal Measurement

After establishing clusters, it is important to examine whether the three groups are separated along sociodemographic lines.

In terms of nationality, two-thirds of Syrian respondents were in the SBM group (61.1%), while only one-tenth of Hungarians thought this way (12.7%). However, the proportion of Hungarians in favour of infant formula feeding was much higher (39.1%), while a tenth of Syrians shared their attitude (13.3%). The proportion of Hungarians thinking flexibly was 48.2%, while it was only a quarter (25.6%) of Syrian respondents (

Table 4).

The relationship between nationality and feeding preferences was significant and moderately strong, so nationality was a significant factor in determining cluster membership in relation to feeding preferences. Syrian participants were more in favour of breastfeeding, while Hungarians were more flexible or even in favour of formula feeding. (

Table 4, Sig.: 0.000; Cramer’s V: 0.502)

The proportion of SBM decreased with increasing educational attainment. It was highest among those with a BSc (43.0%), while only a quarter of those with a higher degree fell into this cluster (MSc: 28.1%, PhD: 29.7%). The distribution of the SFF group was relatively even, but the proportion was moderately increased among those with a higher degree (BSc: 24.7%, MSc: 26.7%, PhD: 27.0%). The proportion of FT was highest among MSc and PhD graduates (MSc: 45.2%, PhD: 43.2%), while a third of those with a bachelor's degree belonged to this group (32.3%) (

Table 5).

Thus, those with MSc and PhD degrees were more likely to be FT, while those with lower degrees (BSc) were more likely to be in favour of breastfeeding.

Although the relationship between educational attainment and clustering was statistically significant, the level of education had only a moderate influence on feeding attitudes (

Table 5, Sig.: 0.012; Cramer’s V: 0.104).

There was also a significant relationship between parental education and respondents' cluster group membership, but this relationship was very weak (

Table 6, Sig.: 0.023; Cramer's V: 0.113).

A higher proportion (40.5%) of children of fathers who did not have a university degree tended to belong to the SBM group, while a third (35.9%) of children of fathers who had a university degree belonged to this attitude group. Similar proportions were found in the FT group. Among children of fathers with lower education, a higher proportion (38.4%) appeared in this group than among children of fathers with university education (33.2%). The reverse was observed for the proportions of those who were SFF. Children of fathers with a high level of education were more likely to be in the SBM group (30.9%), and children of fathers with a lower level of education were less likely (21.0%) (

Table 6).

The following comparison shows that the majority of married respondents (64.1%) were in the SBM group, while the proportion of unmarried respondents was significantly lower in this group. The SFF was dominated by unmarried respondents (30.6%), while only one-tenth of married respondents belonged to this cluster (12.4%). The FT included 41.2% of unmarried respondents, while only one quarter of married respondents (23.5%) had similar attitudes. Married people were much more likely to support breastfeeding, while unmarried people were more likely to support formula feeding and to be flexible (

Table 7).

Marital status was statistically significant for the feeding preference groups, and a moderately strong effect could be seen (

Table 7, Sig.: 0.001; Cramer's V: 0.336).

Income was also significantly related to the attitudes that made up the clusters, and the association was moderately strong (

Table 8, Sig.: 0.001; Cramer's V: 0.278). The low-income group had the highest proportion of SBM (63.6%), while the lowest proportion was of those in the SFF (12.1%). Among those with sufficient income, the proportions were more interesting. Both the proportions of SFF (32.9%) and FT (42.9%) were above 30%, so they had a higher proportion than SBM. FT tended to dominate among those with the highest incomes (50.0%), and SFF accounted for 33.3%. Those with lower incomes were more likely to support breastfeeding, while those with higher incomes were more inclined towards formula feeding or a flexible approach (

Table 8).

4. Discussion

It can be noted that IIFAS statements can be grouped by thematic criteria.

The participants' attitudes toward

perceived health and nutritional values are the most important. There is no doubt that breastfeeding is the optimal nutrition for the ideal growth, development, and health of infants [

1,

3,

46]. In our study, the responses among the two nationalities are logical and consistent with research, which indicates that breastfed infants generally experience better health outcomes compared to formula-fed infants [

1,

20,

47]. Infants generally digest breast milk more easily than formula because breast milk contains enzymes that facilitate better absorption of nutrients. Additionally, the proteins in breast milk are predominantly whey proteins, which are softer and more easily digestible than the casein-dominant proteins found in many formulas [

22,

48]. Syrian participants agree more than Hungarians that breast milk is more easily digested than formula, but the percentages align with previous studies [

49]. Breast milk indeed contains relatively low amounts of iron [

50,

51], but it is highly bioavailable, meaning that infants can absorb it efficiently. Thus, students' choices may differ based on how they interpret the fact of iron bioavailability. There were notable differences in how Hungarian and Syrian students responded to this statement. Most of the Hungarian participants were uncertain. In comparison, Syrian participants were more divided. Thus, these results do not resemble previous studies [

49,

52]. Potential overfeeding occurs in 37% of fully formula-fed infants [

53,

54]. However, the high rate of “not sure” responses among the two statements regarding the relationship between feeding methods and overfeeding could reflect the complexity of the topic; still, this finding is consistent with previous research in particular details: agreement and disagreement [

55].

Another thematic criterion pertains to the

convenience and practical aspects. According to international organizations, breastfeeding has always been more convenient than formula feeding [

1,

40], and our study's results comply with this finding. Although only about half of the participants expressed their agreement with this statement, it aligns with previous studies [

52]. Returning to work is one of the significant challenges nursing mothers faces and affects the duration of exclusive breastfeeding [

56,

57]. Previous studies showed that formula feeding is the best option when the mother plans to return to work [

58], which is what we also found in our results.

Bonding and emotional connection are criteria that can clearly be shown. Research shows that hormones are associated with bonding and emotional closeness between mother and child [

59,

60]. Skin-to-skin contact is an ideal method for greeting the newborn. It fosters a sense of safety and tranquillity in the infant while initiating the bonding process [

17,

20,

61,

62] and positively affecting the mother’s mood [

63]. The majority of the participants agreed that breastfeeding increases mother-infant bonding, making their decisions strongly consistent with the results of previous studies [

3,

6] and with global organizations [

17,

20]. In addressing emotional connection, fathers have a remarkable role in supporting mothers, and their attitudes usually significantly influence mothers’ decisions to breastfeed [

64,

65]. Our findings showed that these results are different from the findings of previous studies [

52].

The last criterion is related to

social and risk perception; Breastfeeding in public spaces always has conflicting opinions among participants, especially when the “breastfeeding with discretion” phrase is missing or when the location or use of a cover is not determined, and that is why it is noticeable that, in general, there is concord in the responses among the participants, making the approximate percentages consistent with other international research [

65,

66], and conflict with others who found restrictive attitudes toward exposure to the breast, considering it unacceptable behaviour and to be kept private [

67,

68]. Consuming alcohol during breastfeeding undoubtedly has effects on both infants and mothers [

69,

70]. However, current recommendations emphasise waiting a minimum of two hours after consuming alcohol before breastfeeding [

71,

72]. This fact, which encourages mothers not to stop breastfeeding even if they drink alcohol, considering the recommendations, is unknown to the majority of the participants, making the results consistent with other studies [

49].

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant role of cultural norms and personal experiences in shaping breastfeeding attitudes among female university students in Syria and Hungary. The cluster analysis produced distinct groups along the lines of breastfeeding and formula-feeding attitudes. These clusters differed not only in terms of feeding preferences but also in terms of demographic factors (nationality, education, marital status, income differentials, father's education).

It was found that low-income respondents were more likely to support breastfeeding, probably due to cost-effectiveness and perceived benefits. However, higher-income respondents tended to prefer formula feeding or a flexible approach, presumably because of either better access to financial resources or convenience and lifestyle factors.

Differences between clusters by nationality were also clearly visible. Syrians were more in favour of breastfeeding, which may be due to cultural and religious reasons. At the same time, Hungarians preferred a more flexible approach or even the use of a formula, which may indicate that Hungarians tend to have a more modernised, convenience-focused approach.

These findings indicate that economic and cultural factors influence infant feeding decisions and how society views breastfeeding or formula feeding.

Understanding these differences is crucial for developing targeted health promotion strategies that encourage informed breastfeeding choices while respecting cultural diversity. Future research should further explore how societal changes, healthcare policies, and exposure to breastfeeding education influence young adults’ perspectives across different regions.

Data Availability Statement:

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Author Contributions

M.A.K. and H.J.F.; methodology, K.A.B.; formal analysis, M.A.K. and K.A.B.; investigation, M.A.K. and H.J.F.; resources, M.A.K.; data curation, M.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.K.; writing—review and editing, M.A.K., H.J.F., A.Z.-B. and K.A.B.; supervision, H.J.F.; project administration, H.J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of DAMASCUS UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF PHARMACY (No. 1538; 14 November 2022) and the Ethics Committee of DAMASCUS UNIVERSITY SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH AND POSTGRADUATE STUDIES (No. 578, 15 November 2022; 1538); and the SEMMELWEIS UNIVERSITY REGIONAL, INSTITUTIONAL AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH ETHICS COMMITTEE (No. 240/2022; 1 February 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all persons involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all the students who participated in this study from both countries and to the management of Damascus, Semmelweis, and Eötvös Loránd Universities, who let us launch this questionnaire in a facilitated manner.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IIFAS |

The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| PASW |

Predictive Analysis Software |

References

- (WHO), W.H.O. Exclusive breastfeeding for optimal growth, development and health of infants. 2023; Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/exclusive-breastfeeding.

- NEWTON, E.R., Breastmilk: The Gold Standard. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2004. 47(3): p. 632-642.

- Meek, J.Y.; Noble, L.; Breastfeeding, S.O. Policy Statement: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2022, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterich, C.M.; Felice, J.P.; O’sullivan, E.; Rasmussen, K.M. Breastfeeding and Health Outcomes for the Mother-Infant Dyad. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2013, 60, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, H. Cesar, and O. World Health, Long-term effects of breastfeeding: a systematic review. 2013, Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Ip, S.; Chung, M.; Raman, G.; Chew, P.; Magula, N.; Devine, D.; Trikalinos, T.; Lau, J. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Évid. Rep. Technol. Assess. 2007, 153, 1–186. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; Franca, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C.; et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.S.; Kakuma, R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scariati, P.D.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Fein, S.B. A Longitudinal Analysis of Infant Morbidity and the Extent of Breastfeeding in the United States. Pediatrics 1997, 99, e5–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.S.; Chheda, S.; E Keeney, S.; Schmalstieg, F.C.; Schanler, R.J. Immunologic protection of the premature newborn by human milk.. 1994, 18, 495–501.

- Garofalo, R.P.; Goldman, A.S. Expression of Functional Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Factors in Human Milk. Clin. Perinatol. 1999, 26, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Mihrshahi, S. Exclusive Breastfeeding and Childhood Morbidity: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 14804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, T.M.; Wright, A.L. Health Care Costs of Formula-feeding in the First Year of Life. Pediatrics 1999, 103, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (CDC), C.f.D.C.a.P., About Breastfeeding. 2024.

- Stuebe, A., The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Rev Obstet Gynecol, 2009. 2(4): p. 222-31.

- Modak, A.; Ronghe, V.; Gomase, K.P.; Dukare, K.P. The Psychological Benefits of Breastfeeding: Fostering Maternal Well-Being and Child Development. Cureus 2023, 15, e46730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicine, J.H. The Benefits of Breastfeeding. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns-hopkins-howard-county/services/mothers-and-babies/breastfeeding.

- Hastings, G.; Angus, K.; Eadie, D.; Hunt, K. Selling second best: how infant formula marketing works. Glob. Heal. 2020, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasaro-Donahue, V.M.; Tovar, A.; Sebelia, L.; Greene, G.W. Increasing Breastfeeding in WIC Participants: Cost of Formula as a Motivator. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elana Pearl Ben-Joseph, M. Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding. 2018; Available from: https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/breast-bottle-feeding.html.

- Martin, C.R.; Ling, P.-R.; Blackburn, G.L. Review of infant feeding: key features of breast milk and infant formula. Nutrients 2016, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, S., Chung, M., Raman, G., Trikalinos, T.A., & Lau, J., Infant Formula: Evaluating the Safety of New Ingredients. 2009: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US).

- Wanjohi, M.; Griffiths, P.; Wekesah, F.; Muriuki, P.; Muhia, N.; Musoke, R.N.; Fouts, H.N.; Madise, N.J.; Kimani-Murage, E.W. Sociocultural factors influencing breastfeeding practices in two slums in Nairobi, Kenya. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2016, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinsma, K.; Bolima, N.; Fonteh, F.; Okwen, P.; Yota, D.; Montgomery, S. Incorporating cultural beliefs in promoting exclusive breastfeeding. Afr. J. Midwifery Women's Heal. 2012, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kamsheh, M.; Bornemissza, K.A.; Zimonyi-Bakó, A.; Feith, H.J. Examining Sociocultural Influences on Breastfeeding Attitudes Among Syrian and Hungarian Female Students. Nutrients 2025, 17, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, R.F.; Mathews, A.; Oden, R.; Moon, R.Y. The Influence of Social Networks and Norms on Breastfeeding in African American and Caucasian Mothers: A Qualitative Study. Breastfeed. Med. 2019, 14, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodribb, W.; Fallon, A.; Jackson, C.; Hegney, D. The relationship between personal breastfeeding experience and the breastfeeding attitudes, knowledge, confidence and effectiveness of Australian GP registrars. Matern. Child Nutr. 2008, 4, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobzon, A.; Engström, Å.; Lindberg, B.; Gustafsson, S.R. Mothers’ strategies for creating positive breastfeeding experiences: a critical incident study from Northern Sweden. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, C.L. Effects of education on breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes among middle school students. Heal. Educ. J. 2015, 75, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvatum, I.a.G., Mothers’ experience of not breastfeeding in a breastfeeding culture. J Clin Nurs, 26: 3144-3155, 2017.

- Woollard, F.; Porter, L. Breastfeeding and defeasible duties to benefit. J. Med Ethic- 2017, 43, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollard, F. Should we talk about the ‘benefits’ of breastfeeding? The significance of the default in representations of infant feeding. J. Med Ethic- 2018, 44, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leahy-Warren, P.; Creedon, M.; O’mahony, A.; Mulcahy, H. Normalising breastfeeding within a formula feeding culture: An Irish qualitative study. Women Birth 2017, 30, e103–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, P.A.R.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Rollins, N.C.; Piwoz, E.; Baker, P.; Barros, A.J.D.; Victora, C.G. Infant Formula Consumption Is Positively Correlated with Wealth, Within and Between Countries: A Multi-Country Study. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, S.W., Milk and social media: online communities and the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. J Hum Lact, 2012. 28(3): p. 400-6.

- UNICEF, Country Profiles.

- K. KOPCSÓ, J.B., L. FRUZSINA, Z. VEROSZTA, A szoptatás és a kizárólagos anyatejes táplálás gyakorisága és korrelátumai a csecsemő születésétől hat hónapos koráig. 2022.

- WHO. Promoting breastfeeding and complementary foods. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/activities/promoting-breastfeeding-and-complementary-foods.

- Khresheh, R. Knowledge and attitudes toward breastfeeding among female university students in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2020, 9, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charafeddine, L.; Tamim, H.; Soubra, M.; de la Mora, A.; Nabulsi, M.; Research and Advocacy Breastfeeding Team; Kabakian, T. ; Yehya, N.; Sinno, D.; Masri, S. Validation of the Arabic Version of the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale among Lebanese Women. J. Hum. Lact. 2015, 32, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bień, A.; Kulesza-Brończyk, B.; Przestrzelska, M.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Ćwiek, D. The Attitudes of Polish Women towards Breastfeeding Based on the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS). Nutrients 2021, 13, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, U.T. Breastfeeding Exposure, Attitudes, and Intentions of African American and Caucasian College Students. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.A.; Alshahrani, M.A.; Al-Thubaity, D.D.; Sayed, S.H.; Almedhesh, S.A.; Elgzar, W.T. Associated Factors of Exclusive Breastfeeding Intention among Pregnant Women in Najran, Saudi Arabia. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Binns, C.W.; Katsuki, Y.; Ouchi, M. Japanese mothers' breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes assessed by the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitudes Scale. 2013, 22, 261–265. [CrossRef]

- Mora, A.d.l., et al., The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale: Analysis of Reliability and Validity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 1999. 29(11): p. 2362-2380.

- Lessen, R.; Kavanagh, K. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedlinePlus. Breastfeeding vs. formula feeding. 2023; Available from: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000803.htm.

- Martin, C.R.; Ling, P.-R.; Blackburn, G.L. Review of infant feeding: key features of breast milk and infant formula. Nutrients 2016, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotelo, M.D.C.S.; Movilla-Fernández, M.J.; Pita-García, P.; Novío, S. Infant Feeding Attitudes and Practices of Spanish Low-Risk Expectant Women Using the IIFAS (Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale). Nutrients 2018, 10, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friel, J.; Qasem, W.; Cai, C. Iron and the Breastfed Infant. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Iron. 2024 February 9, 2024; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/hcp/diet-micronutrients/iron.html.

- Adegbayi, A.; Scally, A.; Lesk, V.; Stewart-Knox, B.J. A Survey of Breastfeeding Attitudes and Health Locus of Control in the Nigerian Population. Matern. Child Heal. J. 2023, 27, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.E.; Martinez, C.E.; Ventura, A.K.; Whaley, S.E. Potential overfeeding among formula fed Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children participants and associated factors. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J.; Russell, C.G.; Laws, R.; Fowler, C.; Campbell, K.; Denney-Wilson, E. Infant formula feeding practices associated with rapid weight gain: A systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.; Bhatt, A.; Chapple, A.G.; Buzhardt, S.; Sutton, E.F. Attitudes and barriers to breastfeeding among women at high-risk for not breastfeeding: a prospective observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, F., Returning to work while breastfeeding. American family physician, 2003. 68(11): p. 2199-2207.

- Chuang, C.-H.; Chang, P.-J.; Chen, Y.-C.; Hsieh, W.-S.; Hurng, B.-S.; Lin, S.-J.; Chen, P.-C. Maternal return to work and breastfeeding: A population-based cohort study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppiger, D.; Natalucci, G.; Reinelt, T. Reliability and validity of the German version of the Iowa infant feeding attitude scale (IIFAS-G) and relations to breastfeeding duration and feeding method. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2024, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvnäs moberg, K.; Ekström-Bergström, A.; Buckley, S.; Massarotti, C.; Pajalic, Z.; Luegmair, K.; Kotlowska, A.; Lengler, L.; Olza, I.; Grylka-Baeschlin, S.; et al. Maternal plasma levels of oxytocin during breastfeeding—A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0235806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuebe, A.M.; Grewen, K.; Meltzer-Brody, S. Association Between Maternal Mood and Oxytocin Response to Breastfeeding. J. Women's Heal. 2013, 22, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.R.; Bergman, N.; Anderson, G.C.; Medley, N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD003519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, R.; Rosenthal, Z.; Eidelman, A.I. Maternal-Preterm Skin-to-Skin Contact Enhances Child Physiologic Organization and Cognitive Control Across the First 10 Years of Life. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, R.; Eidelman, A.I.; Sirota, L.; Weller, A. Comparison of Skin-to-Skin (Kangaroo) and Traditional Care: Parenting Outcomes and Preterm Infant Development. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.; Landers, M.; Hughes, R.; Binns, C. Factors associated with breastfeeding at discharge and duration of breastfeeding. J. Paediatr. Child Heal. 2001, 37, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.N.; Giglia, R.C.; Binns, C.W. The influence of infant feeding attitudes on breastfeeding duration: evidence from a cohort study in rural Western Australia. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2015, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.T., Breastfeeding in Public: Knowledge and Perceptions on a University Campus., in The Eleanor Mann School of Nursing Undergraduate Honors. 2021, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

- Aloysius, M.; Jamaludin, S.S.S. Breastfeeding in public: A study of attitudes and perception among Malay undergraduates in Universiti Sains Malaysia. Malays. J. Soc. Space 2018, 14, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurles, P.K.; Babineau, J. A Qualitative Study of Attitudes Toward Public Breastfeeding Among Young Canadian Men and Women. J. Hum. Lact. 2010, 27, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, S., et al., Why do women consume alcohol during pregnancy or while breastfeeding? Drug and Alcohol Review, 2022. 41(4): p. 759-777.

- Giglia, R.C. and C.W. Binns, Alcohol and breastfeeding: what do Australian mothers know? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr, 2007. 16 Suppl 1: p. 473-7.

- Haastrup, M.B., A. Pottegård, and P. Damkier, Alcohol and Breastfeeding. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 2014. 114(2): p. 168-173.

- Popova, S.; Lange, S.; Rehm, J. Twenty Percent of Breastfeeding Women in Canada Consume Alcohol. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2013, 35, 695–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) can be found in the appendix file. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).