1. Introduction

In the ever-evolving landscape of health and wellness, the rise of probiotic beverages has acquired significant attention from both the scientific community and the general public. The term ‘probiotics’ was first used by Lilly and Stillwell [

1] to designate unknown growth-promoting substances produced by a ciliate protozoan that stimulated growth of another ciliate. Currently this term encompasses a much larger group of organisms. The joint Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) Working Group [

2] defined probiotics as “live micro-organisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host”. Also, the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics widely accepted and adopted this definition [

3].

The mechanism of action of probiotics relates to their influence on the microbes that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract. Normal microbial colonization of the human body is dependent on the conditions of the local chemical environment, the degree of oxygenation, the nutritional intake of the host tissue, and the intervention of the immune system, and for these reasons, the mechanisms of action of probiotics are complex and often strain-specific. The benefits of a probiotic are the result of the interaction between the probiotic strain, the resident microbiota, and the host [

4]. The effect of probiotics on human health has been studied under different conditions and has been shown to play a wide role in the prevention and treatment of numerous diseases. Scientific data show the benefits of probiotics in certain types of gastrointestinal diseases, cardiovascular disease, allergic diseases, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, different types of cancer and the side effects associated with cancer, osteoporosis, immune health, prevention of covid, among many others [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Most clinically documented and validated health effects have been studied using fermented milk products containing viable probiotic cultures. In addition, these probiotic beverages have been positively valued by consumers principally due to their distinctive taste and because they are easy to consume long-term in everyday life [

8]. However, in recent years there has been a notable increase in consumer demand for plant-based probiotic beverages. Furthermore, there is a rising demand for plant-based and dairy-free probiotics, especially designed for intolerance lactose people. As such, researchers and industry players have directed their efforts towards developing innovative plant-based probiotic formulations that not only meet various dietary preferences but also provide health benefits [

9,

10,

11]. These new plant-based beverages, majority derived from fruits and vegetables, are a promising solution by providing a rich source of probiotics without the limitations of dairy products. Recent research has highlighted the great potential of these plant-based probiotic beverages, which not only serve as a sustainable way to upcycle food waste but also possess numerous functional properties [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Likewise, the interaction between probiotic strains and the phytochemical compounds present in the plant-based substrates produces a wide array of functional bioactive compounds, expanding health. Phenolic compounds of the vegetable matrices have been also associated with plant health-promoting activities; moreover, their potential prebiotic activity as well as of their process-derived bioactive molecules have been recently recognized [

16,

17,

18].

Technological innovations can contribute to the evolution of production systems and the attainment of more sustainable and healthier food products. Despite their various health and environmental benefits, food innovations sometimes encounter resistance from a portion of the population [

19,

20,

21]. Several factors explain this situation, including changes in sensory properties related to innovative processes, fear of loss of traditionality, distrust of new technologies, and cultural habits [

22]. Therefore, it is important to analyze these tensions and evaluate under what conditions an innovation can contribute to the development of products that generate health benefits, in a way that is compatible with consumer preferences. Certainly, a better understanding of the factors influencing consumer perception of these new foods is needed to highlight certain possibilities for overcoming any reluctance [

23,

24].

In the scope of food and beverage research, the evaluation of sensorial characteristics, particularly aroma and taste, plays a crucial role in determining the overall acceptability of a product by consumers. The development of new foods involves achieving an aroma and flavor profile that is desirable for consumers, with an identifiable aroma, and with a minimal presence of unknown aromas [

25,

26]. It is noteworthy at this point that while trained panels have provided valuable data on the sensory properties of foods, there is increasing emphasis on understanding how untrained consumers perceive food flavours, as their integrated perceptions may better determine preferences and acceptance.

However, the acceptance of plant-based probiotic beverages depends not only on the choice of the substrate, but also on the adaptation of the probiotic strain to it, in this case to the vegetal beverage. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in obtaining probiotic bacteria from plant origins. This is the case of

Lactiplantibacillus pentosus LPG1, a lactic acid bacterium isolated from table olive biofilms which has shown remarkable technological features such as esterase and phytase activity, production of lactic acid, bacteriocin production, etc. [

27]. A recent genomic analysis of the

L. pentosus LPG1 strain has revealed various genes involved in adhesion, biofilm formation, bacteriocin production, degradation of carbohydrates, and metabolism of phenolic compounds, among these important technological features [

28,

29]. This microorganism has also shown important potential probiotic features, proving to be an anti-inflammatory agent, reducing cholesterol levels and inhibiting foodborne pathogens [

27,

30]. Moreover,

L. pentosus LPG1 has recently shown the capacity to modulate the intestinal microbiota of healthy individuals in a clinical trial [

31]. Therefore, using plant-based probiotics with

L. pentosus LPG1 to modulate gut microbiota is a promising strategy for enhancing gastrointestinal health in humans.

Thus, in view of the current market demand of non-dairy probiotic foods, this study aimed to develop four different non-dairy functional beverages containing L. pentosus LPG1, using different fruit and vegetable matrices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Probiotic Fruit and Vegetable Beverage Sample Preparation

For this study four different juices were prepared with diverse raw materials, such as fruits and vegetables.

Table 1 shows the specific information regarding the raw materials used for each type of beverage, which were produced by Probiotic Biotech & Pharma (Cordoba, Spain) in commercial shots of 100 mL (see Figure S1, supplementary material). Juices were fortified with the commercial probiotic of vegetable origin

L. pentosus LPG1. For this purpose, we used the commercial lyophile denominated as Oleica Starter Vegetable (Oleica, Seville, Spain), which had a dose of 1 x 10

12 CFU of the

L. pentosus LPG1 strain by 75 g of product. Juices were fortified using 1 g of lyophile by 1 L of juice, making a theoretical initial inoculation of 13.3 mill CFU/mL (1.33 x 10

9 CFU by shot). The lyophile was added once the juice was already prepared, subsequently proceeding to a slight homogenization of product by shaking 200 rpm for 5 min. Shots were not pasteurized. Probiotic vegetal beverages (PFVBs) were stored at 4 °C during storage (52 days) until analysis.

2.2. Microbial Analysis

The microbial population levels in the different PFVBs were controlled at initial (3 days) and final (52 days) of beverage storage for lactic acid bacteria (LAB), fungi/molds,

Enterobacteriaceae, and pathogen populations. Appropriate dilutions were carried out in 0.9 % sterile saline solution and then plated on selective media using a spiral plate maker model easySpiral Dilute (Interscience, Saint Nom la Brétèche, France).

Enterobacteriaceae were plated on VRBD (Crystal-violet Neutral-Red bile glucose) agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), LAB on MRS (Man, Rogosa, Sharpe) agar supplemented with 0.02 % sodium azide (Sigma, St. Luis, USA), and fungi/molds on YM (yeast-mal-peptone-glucose) agar (Difco™, Becton and Dickinson Company, Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with oxytetracycline and gentamicin sulfate as selective agents. Plates were subsequently incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and 48 h for

Enterobacteriaceae and LAB, respectively, or 30 °C for 48 h for fungi/molds. Counts were performed using an automatic image analysis system model Scan4000 (Interscience, SaintNom la Brétèche, France) and results were expressed as log

10 CFU/mL. For the analysis of foodborne pathogenic bacteria (Staphylococcus, Salmonella and Listeria), the method based on ISO standards [

32,

33,

34,

35] was used, respectively.

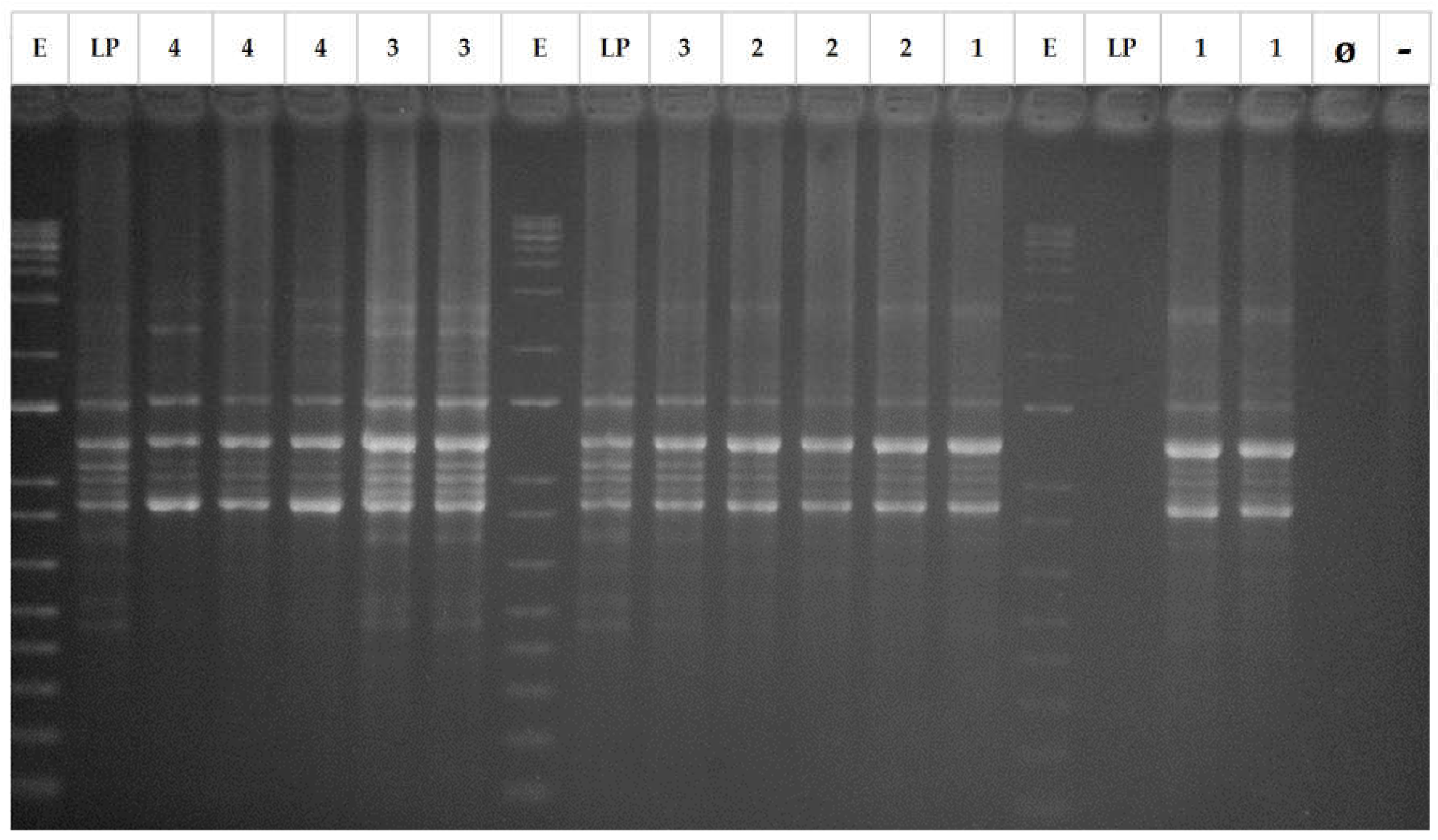

For characterization and genotyping of the lactobacilli population, repetitive bacterial DNA element fingerprinting analysis (rep-PCR) with primer GTG

5 was followed using the protocol described in Versalovic et al. [

36]. The PCR reaction in a final volume of 25 μL contained: 5 μL of 5x MyTaq reaction buffer (5mM dNTPs and 15 mM MgCl

2), 0.1 μL of My Taq DNA polymerase (BiolineReactives, United Kingdom), 1 μL GTG

5 primer (25 μM), 13.9 μL deionized H

20, and 5 μL DNA (~20 ng/μL). PCR amplification was carried out in a thermal cycler (Master Cycler Pro, Eppendorf) with the following program: 95 °C for 5 min as initial step plus 30 cycles at: 1) denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, 2) annealing at 40 °C for 1 min, and 3) extension at 65 °C for 8 min, with a final step of 65 °C for 16 min to conclude the amplification. This methodology was used to determine the recovery frequency of the

L. pentosus LPG1 strain at the end of storage (52 days). For this purpose, 3 isolates were randomly picked from each juice, making a total of 12 isolates for comparison with the LPG1 standard. Their pattern profiles of bands (from 100 up to 3,000 bp) were compared with the strains used to inoculate the juices (LPG1). Thereby, PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2 % agarose gel and visualized under ultraviolet light by staining with ethidium bromide.

2.3. Nutritional Information and pH Measurement

Sodium, protein, sugar, carbohydrates, fat, saturated fatty acid content and total energy were analyzed using the AOAC procedures [

37]. Values were expressed in g/100g of PFVBs. pH was measured using a pH meter model Five Easy Plus (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland).

2.4. Color

Color was determined according to the recommendations of the International Commission on Illumination [

38], with the illuminant D65 (daylight source) and 10° standard observer (perception of a human observer). The parameters calculated were a* (red/green values), b* (yellow/blue values), and L* (lightness). All spectrophotometric measurements were obtained after the centrifugation of the samples for 15 min at 3000 rpm, in a Beckman DU-640 spectrophotometer provided with quartz cells of 1 cm path length.

2.5. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

For the determination of total phenolic content, the Folin-Ciocalteu method was used, with some modifications [

39]. For this, 1.25 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent diluted in distilled water (1:5) was added to 50 µL of the sample filtered by 0.45 µm. This was stirred vigorously and allowed to stand for 1 min. Then, 1 mL of 10 % w/v sodium carbonate was added, and the mixture was allowed to react in the dark for 30 min. After this time, the blue coloration produced was measured at 760 nm using a Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer. A calibration curve for gallic acid was carried out using different concentrations of standard in the range between 0.01 g and 1 g gallic acid/L.

2.6. Antioxidant Activity (AA)

The free radical scavenging activity was measured using the DPPH assay according to Katalinic et al. [

40], with some modifications. 200 µL of the sample or 200 µL of water in the case of the control were added to 3 mL of a 45 mg/L DPPH solution. The absorbance of the control was measured at zero time at 517 nm, while the absorbance of the sample was measured after 30 min of incubation at room temperature and in the dark, using a Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer. The percentage inhibition of DPPH was calculated with the equation (1):

2.7. Sensory Analysis

Two sensory analyses were carried out with different objectives, the first to obtain the aromatic profile of each of the probiotic beverage’s formulation and the second to determine their degree of acceptability after addition of L. pentosus LPG1.

A Flash Profile (FP) was carried out according to the protocol described by Dairou and Sieffermann [

41]. An in-house trained sensory panel comprising 16 panelists, 9 women and 7 men, aged from 24 to 61 years, conducted the sensory evaluations of probiotic formulations. All had broad experience in sensory evaluation and had participated in previous studies of different food matrices. The sensory analysis was carried out in two sessions. During the first session, the four coded PFVBs were simultaneously presented. The panelists were asked to generate the vocabulary to describe the essential descriptors, which should be sufficiently discriminant to differentiate the samples concerning the aroma and taste. In the second session, the panelists grouped in odorant terms, by consensus, the descriptors previously obtained, to reduce the variables to be judged. Then, they evaluated to rank all probiotic beverages formulations on their attributes according to citation frecuency intensity. The samples (40 mL) were coded with random three-digit numbers and presented individually to each panelist in black glasses to prevent the color of the samples from interfering with the tasters' assessment. It was served at consumption temperature (12.0 ± 1.0 °C), and mineral water was provided for rinsing the mouth between samples.

The acceptance test of the different formulations probiotic beverages was conducted by a panel of 50 judges recruited from the staff and undergraduate and master's degree students at the University of Cordoba. The judges (28 women, 22 men) were between 22 and 55 years old. As in the previous sensory analysis, all 40 mL samples were coded with 3-digit random numbers and presented to the panelists in black cups to prevent the color of the samples from interfering with the tasters' evaluation. The acceptance testing of attributes (aroma, taste and overall liking) used a 6-point hedonic scale, as follows: 1-dislike very much, 2-dislike moderately, 3-neither like nor dislike, 4-like slightly, 5-like moderately, 6-like very much [

42]. The evaluation data were recorded and mean scores for each attribute were calculated. The index calculation for the acceptability (AI) of probiotic beverages was performed according to the equation (2):

Where X = average score for the product obtained and n = maximum score given to the product.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) at the 95 % confidence level was performed in triplicate using the Statgraphics v. 5.0 software package from Statistical Graphics Corp (Statgraphics Technologies, Inc. Technologies, Inc., Plains, Virginia). This analysis establishes homogeneous groups and allows testing for significant differences for TPC and AA.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Microbial Analysis

Microbial analysis is necessary to guarantee the quality and safety of food products.

Table 2 shows the microbiological analysis carried out at initial (3 days) and end (52 days) of storage (4 °C) for the different types of PFVBs assayed.

Enterobacteriaceae,

Listeria,

Salmonella, and

Staphylococcus spp. were not detected after spreading the samples in their respective selective growth medium, neither at the beginning or at the end of storage. This data shows that all the PFVBs are microbiologically safe, confirmed by the low pH values obtained. At the beginning the pH values ranged between 4.11 (PFVB4) and 3.78 (PFVB3) and the end of packaging ranged between 3.99 (PFVB4) and 3.70 (PFVB2). Therefore, and taking into account the average pH value of PFVBs at the beginning (3.91 ± 0.14) and at the end (3.82 ± 0.12), it can be concluded that no significant differences were observed between both sampling points. In this sense, the low pH value obtained, combined with the cold storage temperatures (4 °C), were significant environmental factors able to control microbial growth. Most familiar pathogenic bacteria, like

Enterobacteriaceae,

Staphylococci,

Listeria, and

Salmonella spp. are neutrophiles and do not fare well in the acidic pH. Also, fungi were also not noticed in the PFVBs, which may be due to the use of potassium sorbate during packaging. This preservative has proved to be very effective to control yeast growth at acidic pH [

43].

PFVBs were fortified with a theoretical value of the probiotic

L. pentosus LPG1 of 7.12 log

10 CFU/mL (13.3 mill CFU/mL). As can be deduced from

Table 2 and using the counts obtained in the LAB medium, within the first 3 days the probiotic decreased their population levels in the different types of juices studied. The highest decline was observed for the sample PFVB3 elaborated with apple and red fruit juice principally, which reached a 5.92 log

10 CFU/mL. The remaining formulations reached values close to 6.5 log

10 CFU/mL. This value was kept constant throughout storage, and after 52 days of packaging, the average probiotic counts obtained were 6.45 log

10 CFU/mL (>3.4 mill CFU/mL), with a survival rate of 25.6 %. In this sense, different authors [

44,

45,

46] point out that for maximum health benefits, the minimum probiotic organism level in probiotics food product should be 10

6-10

7 CFU/mL at the time of consumption.

To confirm that the LAB counts obtained in the different types of PFVBs correspond to the probiotic

L. pentosus LPG1, 3 isolates randomly taken from LAB medium for each juice were molecularly compared with the rep-PCR profile of

L. pentosus LPG1. As can been deduced from

Figure 1, the 12 isolates rep-PCR profiles were identical to the LPG1 control, confirming the presence of the probiotic at 52 days of packaging.

As mentioned above the FAO, defined probiotic as “live microorganisms when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host”.

L. pentosus LPG1 is a LAB obtained from table olives biofilms (vegetable origin), which has proved to be a probiotic microorganism in animal and human clinical studies as an anti-inflammatory agent and modulator of the intestinal microbiota [

27,

30,

31]. Because there are so many different probiotic organism and variables to consider when making recommendations (dosage, delivery methods, etc.) it is difficult to generalize one optima dose as “adequate”. The dosage of probiotic foods and supplements is based solely upon the number of live organisms present in the product. Successful results have been attained in clinical trials using between 10

7-10

11 CFU/day [

47,

48]. In our study, 100 mL of juices (one shot) give a total dose of 340,000,000 CFU (3.4 * 10

8) of probiotics.

3.2. Nutritional Information

In the development of new plant-based probiotic food products, it is important to examine their nutritional role.

Table 3 shows nutrient values of the different formulations of PFVBs elaborated. In general, fruit and vegetable juices have a low sodium, which is consistent with the particularly low sodium levels (< 0.03 g/100 g) obtained for all PFVBs formulations. Furthermore, they are naturally low in protein content oscillating between 0.7 g/100 g (PFVB2) and 1 g/100 g (PFVB3 and PFVB4), which agrees with the studies carried out by Boyle et al. [

49] on 156 different fruits and vegetables. There is considerable variation in the sugar content in the PFVBs studied, ranging from 1.6 to 11.4 g/100 g, PFVB1 and PFVB4, respectively, mainly due to the different raw materials used in the elaboration of each of them. Fruit juice production has a major effect on carbohydrates: extraction removes virtually all polysaccharides from the plant cell wall (dietary fiber). Regarding the carbohydrate contents, values were similar for the different formulations of PFVBs, ranging between 10 and 12 g/100 g for PFVB1 and PFVB3, respectively.

On the other hand, fruits and vegetables are generally considered low-energy and low-fat foods, which is mainly due to their high content of water. Still, they may contain up to 20 energy % of fat [

50]. PFVB1 showed significantly higher values than the rest of the formulations (3.3 g / 100 g), probably due to one of the ingredients is coconut milk. Coconut milk is rich in lipids, including about 35.2 % fat when no water is added [

51]. In general, the caloric value of fruit and vegetables juices ranges between 40 and 60 kcal per 100 g, except for lemon, tomato and carrot juices whose caloric value is also below average [

52]. The values of total energy of the different PFVBs varied between 47 and 74 kcal/100 g for PFVB2 and PFVB1, respectively. This last one formulation includes grape juice, fruit with one of the highest caloric contributions, and coconut milk, responsible for this greater caloric intake.

3.3. Color

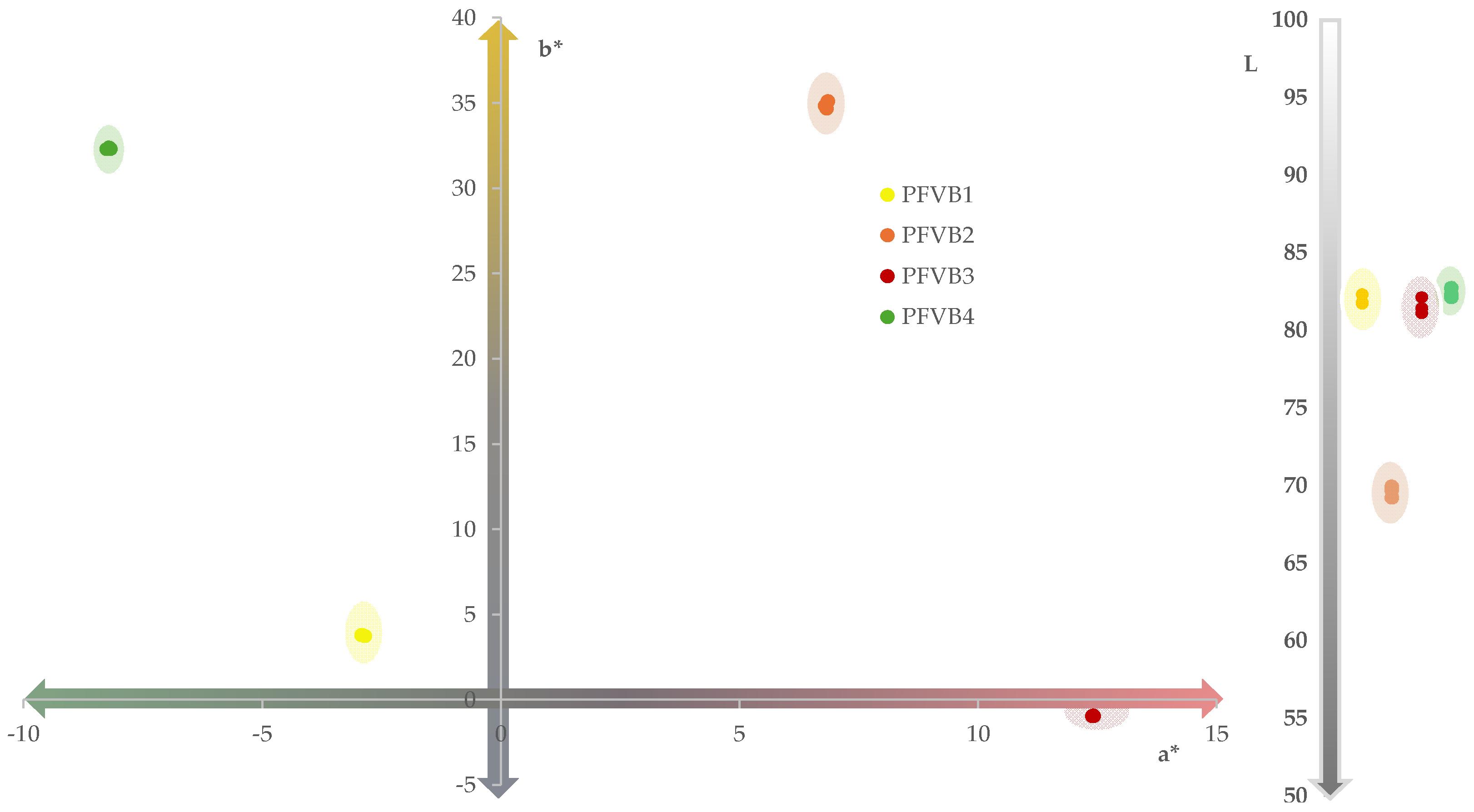

The final color of a product launched on the market is an important attribute because it conditions the choice of the consumer. One of the most widely used tools to define the color of a beverage is by the coordinates of CIELab space.

Figure 2 shows the resulting color of the different PFVBs. As can be seen, these presented final colors according to the composition of the raw materials of each PFVBs. Particularly, in the case of the PFVB1 and PFVB2 beverages, the resulting colors were yellowish and orange, respectively, since the CIELab space coordinates were set to negative a* and positive b* values in the case of PFVB1, and positive a* and b* values for PFVB2. The colors of these probiotic beverages derived mainly from carotenoids and phenolic compounds, present in pineapple, apple, grape, carrot, orange, mango, and ginger [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. In the case of the PFVB4 beverage, it was also included in the same quadrant of CIELab space of PFVB1, but it showed a greenish color, defined by higher value of the a* and b* coordinates. This color is mainly due to the chlorophylls in spinach [

60] and cucumber [

61], and to the phenolic pigments and carotenoids in the fruits and vegetables used in this beverage. On the other hand, the color of the PFVB3 beverage was red with bluish tones (positive a* and negative b* coordinate of CIELab space). This color is mainly due to anthocyanins present in red fruits [

62] and carotenoids and betalains from beet [

63]. Regarding lightness, all the vegetable probiotic beverages exhibited L values exceeding 65. This places them in the upper region of the CIELab color space, suggesting that the resulting beverages are lighting and brightness from the sensory point of view.

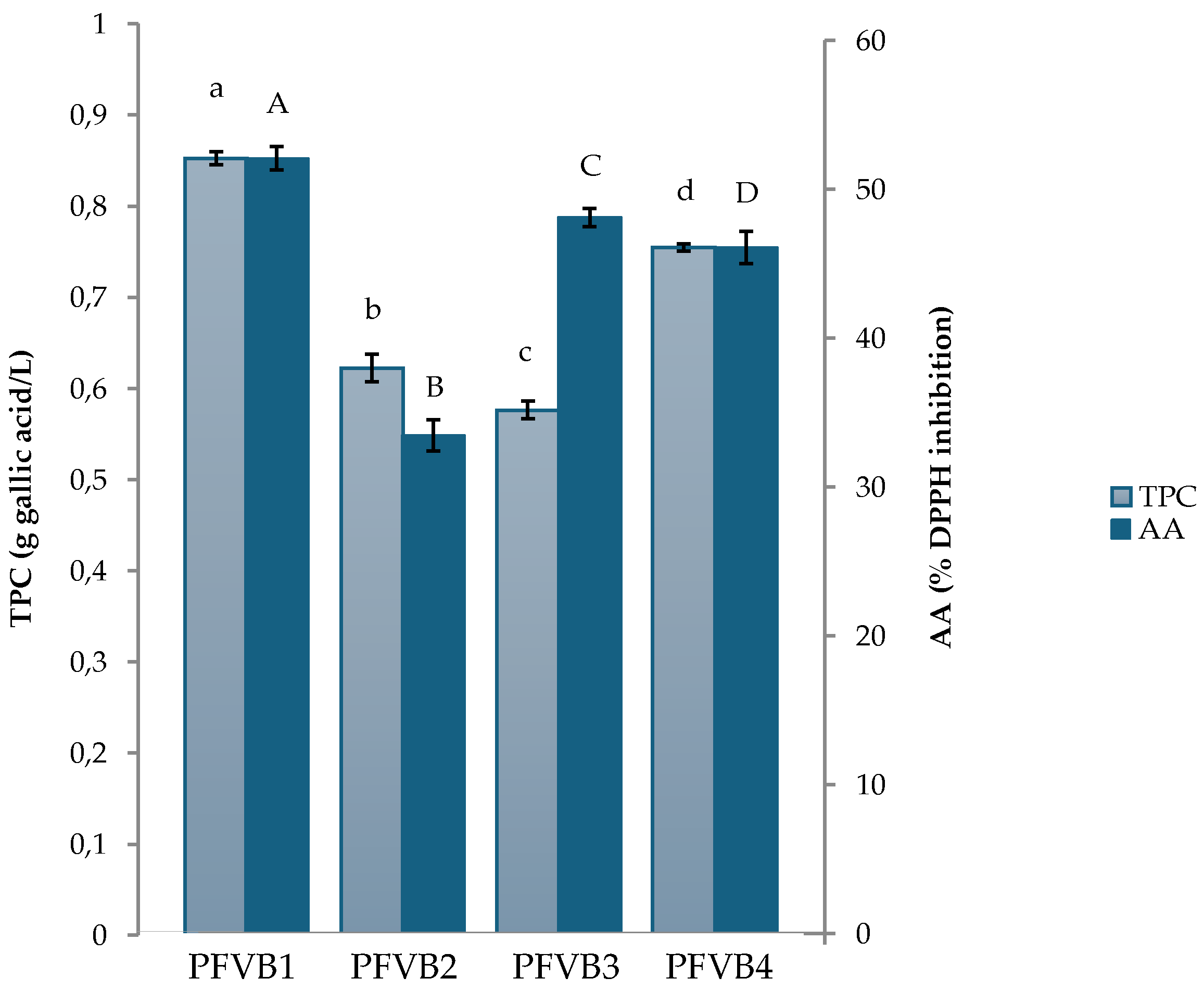

3.4. Total Phenol3.4. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity

Phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites of plants, and their antioxidant properties have been widely studied [

64,

65] due to the benefits they can bring to human health. Derived from the fruits and vegetables that constitute the probiotic beverages, it would be expected that they contain a large amount and variety of phenolic compounds, which makes them high value-added products. The presence of non-flavonoid phenolic compounds such as hydroxybenzoic and hydroxycinnamic acids, and flavonoid compounds such as anthocyanins, flavonols, flavan-3-ol derivatives and flavones, among others, can be highlighted [

56,

58,

59,

60,

62,

64,

66,

67].

Figure 3 shows the values of total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of the probiotic beverages studied. As can be seen, the beverage with the highest amount of total phenolic compounds was PFVB1, followed by PFVB4, PFVB2 and PFVB3, finding significant differences (

p ≤ 0.05) between total phenolic content of all formulations of PFVBs. Regarding antioxidant activity, significant differences were also found between all the beverages elaborated, with PFVB1 reaching the highest value, which is probably related to a higher concentration of phenolic compounds (0.853 ± 0.007 g gallic acid/L). However, PFVB3 presented a higher antioxidant activity value (48.1 % ± 0.628 of DPPH inhibition) than PFVB2 and PFVB4 (33.5 % ± 1.05 and 46.0 % ± 1.07 of DPPH inhibition, respectively) showing the lowest content of total polyphenols (0.576 ± 0.010 g gallic acid/L). Some studies have shown that antioxidant activity is closely related to the content of total phenolic compounds [

62,

68,

69], although it must be considered that this parameter is influenced by other non-phenolic compounds such as vitamins, betalains, carotenes, chlorophylls, etc., present in the probiotic beverages. This fact could justify that PFVB3 exhibited these above-mentioned values. In this sense, the beetroot used in this beverage provides betalains such as betacyanins (red-violet color) and betaxanthins (yellow-orange color), which are potent antioxidants [

70].

3.5. Sensory Evaluation

Sensory analysis is an important analytical tool to objectively characterize food products. In this sense, sensory evaluation of a product, including both the analytical sensory evaluation carried out by a panel of experts and the affective test carried out on consumers, allows to obtain more information about the product being analyzed, its quality and to verify factors influencing its acceptability by consumers, which facilitates work on improving the quality of the product or its reformulation [

42,

71]. Particularly, in the production of probiotic beverages acceptable sensory properties are very important because of the sensory changes that can occur during the development of probiotic products following the addition of probiotic bacteria to raw materials. This approach provides insight into the aromatic qualities of a new formulation, which contributes to product development, quality control and consumer satisfaction.

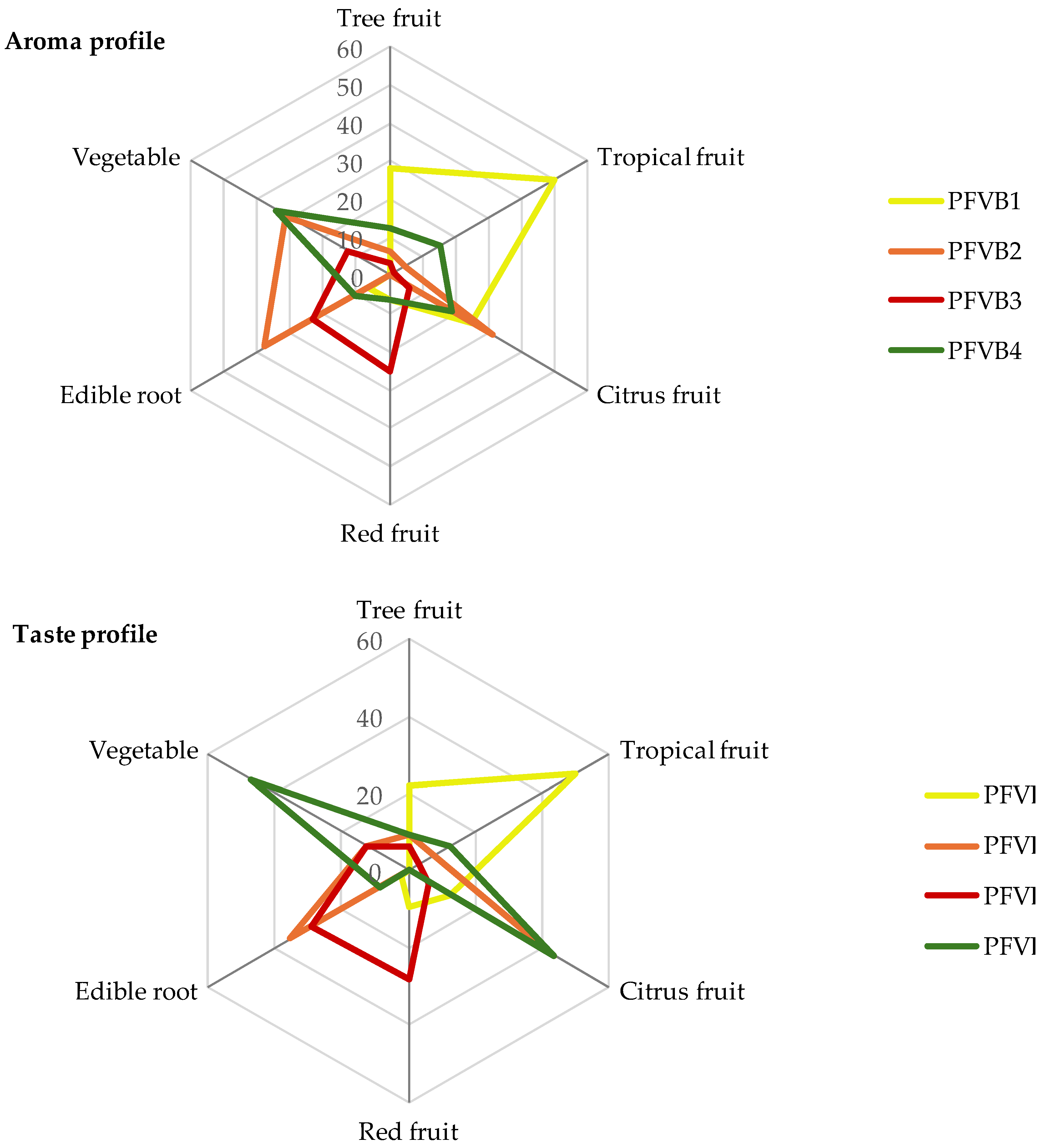

In the first flash profile (FP) session, the panelists recorded 14 sensory descriptors to describe the taste and aroma profile of PFVBs. The sensory attributed generated were: apple, peach, passion fruit, mango, coconut, pineapple, orange, strawberry, berries, carrot, beet, ginger, spinach, and cucumber. In the second session, the panelists grouped the descriptors by aroma similarity and reduced them to 6 sensory terms: tree fruit, tropical fruit, citrus fruit, red fruit, edible root, and vegetable.

The FP results from the four formulations of probiotics beverages are represented in

Figure 4. It is noteworthy that none of the formulations with added probiotic

L. pentosus LPG1 exhibited any unusual aromas or tastes.

The FP of the PFVB1 formulation was mainly described as tropical fruit, tree fruit, and citrus fruit, the latter being the only term that showed a lower citation frequency in the taste profile (12.5 %) versus the aromatic one (25.0 %). In relation to the FP of the PFVB2 notes such as citrus fruit, vegetable and edible root can be profiled in the polygonal diagram. There was a good correlation between the aromatic and taste profile, except for the vegetable term, which were only just detected (12.5 %) during the taste sensorial analysis. Regarding aroma and taste profile of PFVB3, the citation frequency of the sensorial terms of the two-flash profile were very closely matched. In addition, the panelists characterized this formulation by red fruits and edible root notes, principally. Finally, PFVB4 was predominantly characterized as vegetable and citrus notes by the panelists. However, the aroma profile was less intense than the taste profile, especially in terms of the citation frequency of citrus notes (18.8 %).

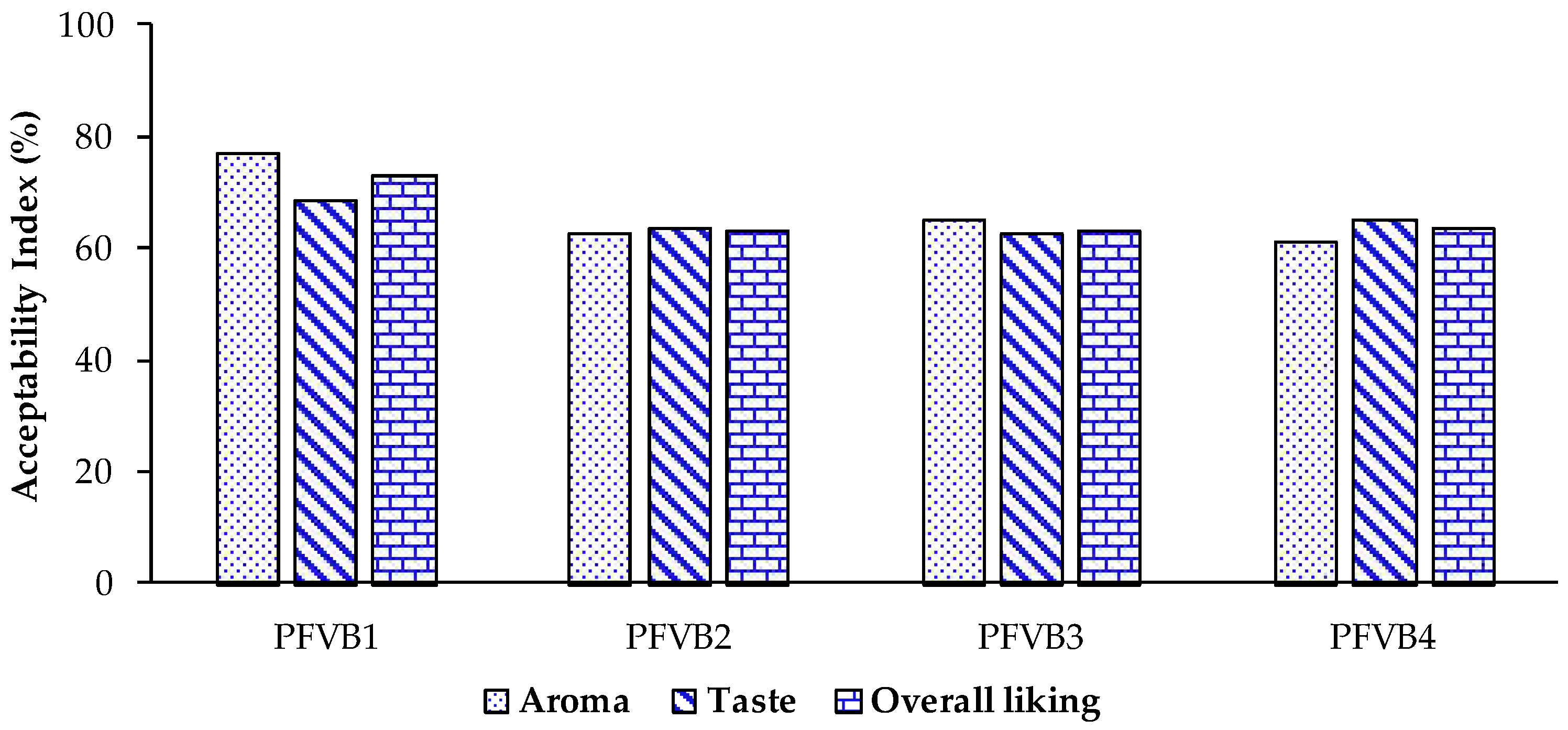

The acceptance rate of aroma and taste attributes and overall liking of the probiotic vegetal beverages was evaluated using the acceptability index and results are shown in

Figure 5. The judges indicated that they liked the odor and taste of beverages in all formulations, more than 61% of them indicated so. In particular, the PFVB1 containing mainly pineapple, apple, and grape juice presented the highest acceptability indexes for aroma (77.1 %) and taste (68.8 %). Contrary, the PFVB4 obtained the lowest acceptability for aroma (61.3 %). It could be related to the raw material of PFVB4, which included spinach (7.05 %) and cucumber (5.64 %). These vegetables contain nitrogen, sulfur and C9 aroma compounds with distinctive grassy, slightly musty, and earthy aromatic notes [

72]. Also, PFVB3 obtained the lowest acceptability index for taste (62.5 %). It is well-established that beets contain significant quantities of flavonoids and phenolic acids capable of providing astringency and bitterness to beverages [

73]. Finally, in terms of overall liking, the acceptability index was higher for the PFVB1 formulation (72.9 %), while for the other formulations the index was lower, at around 63 %.

4. Conclusions

According to results obtained in this study, it is possible to develop vegetable & fruit, not pasteurized, beverages with more than 3 * 108 of probiotics by 100 mL of juice, with appropriate organoleptic profiles and interesting nutritional values after 52 days of cold storage. This type of new products represents an alternative to dairy products as a source of probiotic microorganisms, especially designed for consumers who are lactose intolerant or need a low-cholesterol diet.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, A. L-T., M. V., and L. M., methodology, V. M-A, V.R-G. A. L-T., M. V., and L. M.; software, A. L-T., M. V., and L.M.; validation, A. L-T., M. V., and L. M., F. N. A-L.; formal analysis, F. N. A-L., A. L-T., M. V., P. M-M., and L. M.; investigation, V. M-A, V. R-G., A. L-T., M. V., P. M-M., and L. M., data curation, F. N. A-L., A. L-T., M. V., P. M-M., D. B-G., and L. M.; writing—original draft preparation, F. N. A-L., A. L-T., M.V., D. B-G., and L. M.; writing—review and editing, F. N. A-L, A. L-T., M. V., D. B-G., and L. M.; visualization, F. N. A-L., A. L-T., M. V., and L. M.; supervision, F. N. A-L., A. L-T., and L. M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank to Oleica company (Seville, Spain) for supplying us the probiotic cultures of L. pentosus LPG1, and Probiotic Biotech & Pharma (Cordoba, Spain) for supplying the vegetable and fruit juices.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lilly, D.M.; Stillwell, R.H. Probiotics: Growth-promoting factors produced by microorganisms. Sci. 1965, 147, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Probiotics in animal nutrition. Production, impact and regulation. In FAO Animal production and health paper; Bajagai, Y.S., Klieve, A.V., Dart, P.J., Bryden, W.L., Eds.; Publisher: FAO, Roma, 2016; Volume 179, pp. 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D. J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R. B. Harry; Flint, J.; Salminen, S.; Calder, P.C.; Sanders, M.E. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. In Consensus Statements; Publisher: Macmillan Publishers Limited, United Kingdom, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 506–514. [Google Scholar]

- Maftei, N.M.; Raileanu, C.R.; Balta, A.A.; Ambrose, L.; Boev, M.; Marin, D.B.; Lisa, E.L. The potential impact of probiotics on human health: an update on their health-promoting properties. Microorg. 2024, 12, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.C.R.; Bedani, R.; Saad, S.M.I. Scientific evidence for health effects attributed to the consumption of probiotics and prebiotics: an update for current perspectives and future challenges. British J. Nutrit. 2015, 114, 1993–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayakumar, S.; Rasika, D.M.D.; Priyashantha, H.; Vidanarachchi, J.K.; Ranadheera, C.S. Probiotics and beneficial microorganisms in biopreservation of plant-based foods and beverages. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11737–11754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, R.; Rocha, A.C.; Sousa, A.P.; Ferreira, D.; Fernandes, R.; Almeida, C.; Pais, P.J.; Baylina, P.; Pereira, A.C. Exploring the potential protective effect of probiotics in obesity-induced colorectal cancer: what insights can in vitro models provide? Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wua, M.; Zhao, W.; Kwok, L.Y.; Zhanga, W. Effects of probiotics and its fermented milk on constipation: a systematic review. Food Sci. Human Wellnes 2023, 12, 2124–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, A.; Janghu, S.; Virkar, K.; Gat, Y.; Kumar, V.; Chhikara, N. Potential non-dairy probiotic products-A healthy approach. Food Biosc. 2018, 21, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, C.K.; Guedes, A.F.; da Silva, J.R.; da Silva, E.B.; dos Santos, E.C.; Stamford, Th.C.; Stamford, T.C. Development of vegetal probiotic beverage of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims), yam (Dioscorea cayenensis) and Lacticaseibacillus casei. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchwinska, K.; Gwiazdowska, D.; Jus, K.; Gluzinska, P.; Gwiazdowska, J.; Pawlak-Lemanska, K. Innovative functional lactic acid bacteria fermented oat beverages with the addition of fruit extracts and Lyophilisates. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12707–12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Aguiar, N.F.B.; Voss, G.B.; Pintado, M.E. Properties of fermented beverages from food wastes/by-products. Beverages 2023, 9, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojikon, F.D.; Kasimin, M.E.; Molujin, A.M.; Gansau, J.A.; Jawan, R. Probiotication of nutritious fruit and vegetable juices: An alternative to dairy-based probiotic functional products. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3457–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, Z.; Mir, S.A.; Wani, S.M.; Rouf, M.A.; Bashir, I.; Zehra, A. Probiotic-fortified fruit juices: Health benefits, challenges, and future perspective. Nutrition 2023, 115, 112154–112163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoj, P.M.; Mohan, J.R.; Khasherao, B.Y.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K. Fruit based probiotic functional beverages: A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100729–100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Santos, A.M.; Araujo Sugizaki, C.S.; Carielo Lima, G.; Veloso Naves, M.M. Prebiotic effect of dietary polyphenols: A systematic review. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 74, 104169–104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bellis, P.; Sisto, A.; Lavermicocca, P. Probiotic bacteria and plant-based matrices: An association with improved health-promoting features. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 87, 104821–104833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patelski, A.M.; Dziekonska-Kubczak, U.; Ditrych, M. The fermentation of orange and black currant juices by the probiotic yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3009–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Filippelli, S. Sustainability and open innovation: Main themes and research trajectories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6763–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nat. Food. 2020, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadán, A.; Nieto, R.; Bernabéu, R. Food innovation as a means of developing healthier and more sustainable foods. Foods 2021, 10, 2069–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hobbs, J.E. How do cultural worldviews shape food technology perceptions? Evidence from a discrete choice experiment. J. Agric. Econom. 2020, 71, 465–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Bartkiene, E.; Szucs, V.; Tarcea, M.; Ljubicic, M.; Cernelic-Bizjak, M.; Isoldi, K.; EL-Kenawy, A.; Ferreira, V.; Straumite, E.; Korzeniowska, M.; Vittadini, E.; Leal, M.; Frez-Muñoz, L.; Papageorgiou, M.; Djekic, I.; Ferreira, M.; Correia, P.; Cardoso, A.P.; Duarte, J. Study about food choice determinants according to six types of conditioning motivations in a sample of 11,960 participants. Foods 2020, 9, 888–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Nikolic, A.; Mujcinovic, A.; Blazic, M.; Herljevic, D.; Goel, G.; Trafiałek, J.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Guiné, R.; Gonçalves, J.C.; Smole-Mozina, S.; Kunčič, A.; Miloradovic, Z.; Miocinovic, J.; Aleksic, B.; Gómez-López, V.M.; Osés, S.M.; Ozilgen, S.; Smigic, N. How do consumers perceive food safety risks? Results from a multi-country survey. Food Control 2022, 142, 109216–109221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Pato, V.M.; Sánchez, C.N.; Domínguez-Soberanes, J.; Méndoza-Pérez, D.E.; Velázquez, R. A multisensor data fusion approach for predicting consumer acceptance of food products. Foods 2020, 9, 774–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Kowalski, M.P.; Shackelford, L.T.; Brooks, D.C.; Ennis, J.M. Using Web3 technologies to represent personalized consumer taste preferences in whiskies. Food Qual. Pref. 2024, 118, 105201–105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Cabello, A.; Calero-Delgado, B.; Rodríguez-Gómez, F.; Garrido-Fernández, A.; Jiménez-Díaz, R.; Arroyo-López, F. N. Biodiversity and multifunctional features of lactic acid bacteria isolated from table olive biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- López-García, E.; Benítez-Cabello, A.; Ramiro-García, J.; Ladero, V.; Arroyo-López, F.N. In silico evidence of the multifunctional features of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus LPG1, a natural fermenting agent isolated from table olive biofilms. Foods 2023, 12, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, E.; Benítez-Cabello, A.; Tronchoni, J.; Arroyo-López, F.N. Understanding the transcriptomic response of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus LPG1 during spanish-style green table olive fermentations. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1264341–1264354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez-Cabello, A.; Torres-Maravilla, E.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.; Langella, P.; Martín, R.; Jiménez-Díaz, R.; Arroyo-López, F.N. Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus strains isolated from table olive biofilms. Probiot. Antimic. Proteins 2020, 12, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, E.; Benítez-Cabello, A.; Arenas-de Larriva, A.P.; Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M.; Pérez-Martínez, P.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Garrido-Fernández, A.; Arroyo-López, F.N. Oral intake of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus LPG1 produces a beneficial regulation of gut microbiota in healthy persons: a randomised, placebo-controlled, single-blind trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1931–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 6888-1:2021/Amd 1:2023 Microbiology of the food chain — Horizontal method for the enumeration of coagulase-positive staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and other species) — Part 1: Method using Baird-Parker agar medium — Amendment 1.

- ISO 6579:2002/Cor 1:2004 Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs — Horizontal method for the detection of Salmonella spp. — Technical Corrigendum 1.

- ISO 11290-1:1997/A1:2005 Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs - Horizontal method for the detection and enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes - Part 1: Detection method - Amendment 1: Modification of the isolation media and the haemolysis test, and inclusion of precision data (ISO 11290-1:1996/AM1:2004).

- ISO 11290-2:2018 Microbiology of the food chain - Horizontal method for the detection and enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp. - Part 2: Enumeration method (ISO 11290-2:2017).

- Versalovic, J.; Schneider, M.; de Brujin, F.; Lupski, J.R. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence based PCR (rep-PCR). Methods Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 5, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 22nd ed.Latimer, G.W., Jr., Ed.; AOAC International Publications, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIE Colorimetry, 3rd ed.; International Commission on Illumination: Vienna, Austria, 2004.

- Varo, M.A.; Jacotet-Navarro, M.; Serratosa, M.P.; Mérida, J.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Bily, A.; Chemat, F. Green ultrasound-assisted extraction of antioxidant phenolic compounds determined by high performance liquid chromatography from bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) juice by-products. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2019; 10, 1945–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katalinic, V.; Milos, M.; Kulisic, T.; Jukic, M. Screening of 70 medicinal plant extracts for antioxidant capacity and total phenol. Food Chem. 2006; 94, 550–557. [Google Scholar]

- Dairou, V.; Sieffermann, J.M. A comparison of 14 jams characterized by conventional profile and a quick original method, the Flash Profile. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilgaard, M.C.; Civille, G.V.; Carr, B.T. Sensory Evaluation Techniques, 4th ed.; CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group: New York, 2006; pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Gil, V.; Rodríguez-Gómez, F.; Garrido-Fernández, A.; García-García, P.; Arroyo-López, F.N. Lactobacillus pentosus is the dominant species in spoilt packaged Aloreña de Málaga table olives. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 70, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N. Functional cultures and health benefits. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.M.F.; Ramos, A.M.; Martins, M.L.; Leite-Junior, B.R.C. Fruit salad as a new vehicle for probiotic bacteria. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 36, 540–548. [Google Scholar]

- Shori, A.B. Influence of food matrix on the viability of probiotic bacteria: A review based on dairy and non-dairy beverages. Food Biosc. 2016, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gionchetti, P.; Rizzello, F.; Morselli, C.; Poggioli, G.; Tambasco, R.; Calabrese, C.; Brigidi, P.; Vitali, B.; Straforini, G.; Campieri, M. High-dose probiotics for the treatment of active pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007, 50, 2075–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shornikova, A.V.; Casas, I.A.; Mykkänen, H.; Salo, E.; Vesikari, T. Bacteriotherapy with Lactobacillus reuteri in rotavirus gastroenteritis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1997, 16, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, F.; Lynch, G.; Reynolds, C.M.; Green, A.; Parr, G.; Howard, C.; Knerr, I.; Rice, J. Determination of the protein and amino acid content of fruit, vegetables and starchy roots for use in inherited metabolic disorders. Nutrients, 2024; 16, 2812–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bere, E. Wild berries: a good source of omega-3. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007; 61, 431–433. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.W.; Tang, Y. J.; Chen, W.X.; Chen, H.M.; Zhong, Q.P.; Pei, J.F.; Han, T.; Chen, W.; Zhang, M. Mechanism for improving coconut milk emulsions viscosity by modifying coconut protein structure and coconut milk properties with monosodium glutamate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 252, 126139–126151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreiras, O.; Carbajal, A.; Cabrera, L.; Cuadrado, C. Tablas de composición de alimentos: Guía de prácticas. Pirámide, editor. 2018. ISBN 978-84-368-3623-3.

- Hamidin, N A.S.; Abdullah, S.; Nor, F.H.M.; Hadibarata, T. Isolation and identification of natural green and yellow pigments from pineapple pulp and peel. Materials Today: Proceed. 2022; 63, 406–410. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Pelayo, R.; Gallardo-Guerrero, L.; Hornero-Méndez, D. Chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments in the peel and flesh of commercial apple fruit varieties. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.F.; Lopez-Toledano, A.; Mayen, M.; Merida, J.; Medina, M. Changes in color and phenolic compounds during oxidative aging of sherry white wine. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, M.; Süslüoğlu, Z. Evaluating carrot as a functional food. Middle East J. Sci. 2018, 4, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Vicario, I.M.; Heredia, F.J. Analysis of carotenoids in orange juice. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2007, 20, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, L.; Yao, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhan, R.; Zhou, Y. Polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant properties in mango fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 129, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Jaafar, H.Z.; Rahmat, A. Antioxidant activities, total phenolics and flavonoids content in two varieties of Malaysia young ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Molecules 2010, 15, 4324–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia, M.A.; Jiménez-Monreal, A.M.; González, J.; Martínez-Tomé, M. Spinach. In Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Fruits and Vegetables, Jaiswal,A.K. Ed.; Academic Press: Ireland, 2020; pp. 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebretsadik, K.; Qiu, X.; Dong, S.; Miao, H.; Bo, K. Molecular research progress and improvement approach of fruit quality traits in cucumber. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 3535–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varo, M.A.; Martín-Gómez, J. Mérida, J.; Serratosa, M.P. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) grown in southern Spain. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021; 247, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, N.; Kushwaha, K.; Sharma, P.; Gat, Y.; Panghal, A. Bioactive compounds of beetroot and utilization in food processing industry: A critical review. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C.; Wilches-Pérez, D.; Hallmann, E.; Kazimierczak, R.; Rembiałkowska, E. Organic versus conventional beetroot. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant properties. LWT 2019, 116, 108552–108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umego, E.C.; Barry-Ryan, C. Optimisation of polyphenol extraction for the valorisation of spent gin botanicals. LWT 2024, 199, 116114–116124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunasiri, A.N.; Gunawardane, M.; Senanayake, C.M.; Jayathilaka, N.; Seneviratne, K.N. Antioxidant and nutritional properties of domestic and commercial coconut milk preparations. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 1, 3489605–3489614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotta, E.M.; Rodrigues, C.A.; Jardim, I.C.S.F.; Maldaner, L.; Visentainer, J.V. Determination of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in passion fruit pulp (Passiflora spp.) using a modified QuEChERS method and UHPLC-MS/MS. LWT, 2019; 100, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gómez, J.; García-Martínez, T.; Varo, M.A.; Mérida, J.; Serratosa, M.P. Enhance wine production potential by using fresh and dried red grape and blueberry mixtures with different yeast strains for fermentation. Foods 2023, 12, 3925–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, C.I.; Pop, N.; Babeş, A.C.; Matea, C.; Dulf, F.V.; Bunea, A. Carotenoids, total polyphenols and antioxidant activity of grapes (Vitis vinifera) cultivated in organic and conventional systems. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangar, S.P.; Sharma, N.; Sanwal, N.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Sahu, J.K. Bioactive potential of beetroot (Beta vulgaris). Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111556–111568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiader, K.; Marczewska, M. Trends of using sensory evaluation in new product development in the food industry in countries that belong to the EIT. regional innovation scheme. Foods 2021, 10, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeoka, G. Flavor chemistry of vegetables. In Flavor chemistry: 30 years of progress, an overview, Teranishi, R., Wick, E. L., Hornstein, I.; Kluwer academic / Plenum Publishers, New York, USA, 1999, pp. 287-304.

- Razzak, M.A.; Sharif, M.K.; Naz, T.; Rauf, M.A.; Shahid, F.; Shahzad, R.; Inam, A. Evaluating the bioactive compounds of beetroot and their pharmacological activities in promoting health. Eu. J. Health Sci. 2024, 10, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).