Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtention of Primary Materials

2.2. Growing Conditions of Probiotic Cultures

2.3. Preparation of Fermented Beverages with Whey and Fruits

2.4. Determination of pH, Titratable Acidity, and Soluble Solids

2.5. Determination of Vitamin C

2.6. Determination of Vitamin A

2.7. Determination of Minerals

2.8. Color Determination

2.9. Microbiological Evaluation of the Fermented Beverages

2.10. Sensory Evaluation

2.11. Acceptability Index

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Fruit Pulp

3.2. Vitamins and Minerals from Fruits

3.3. Properties of Probiotic Beverages

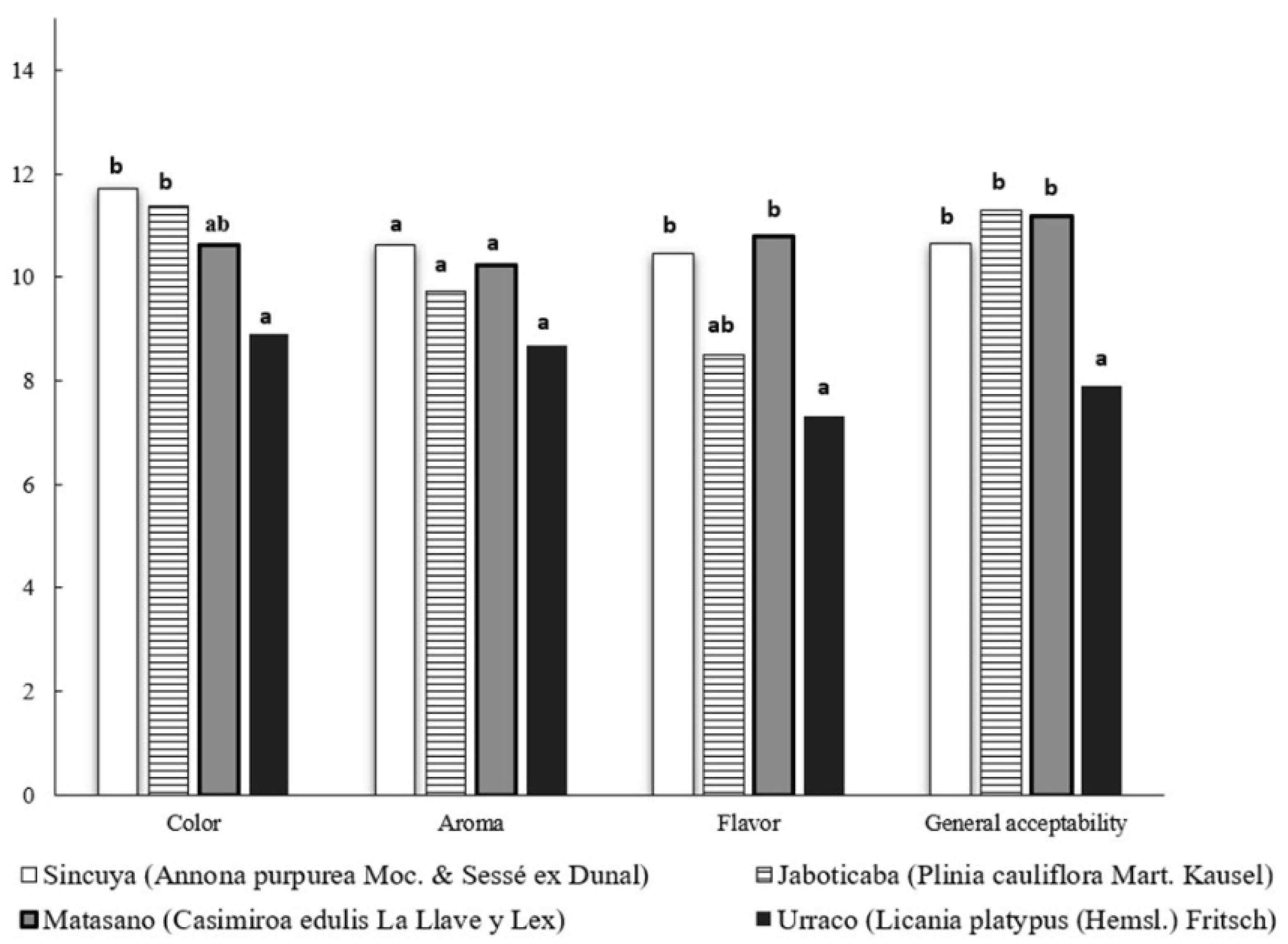

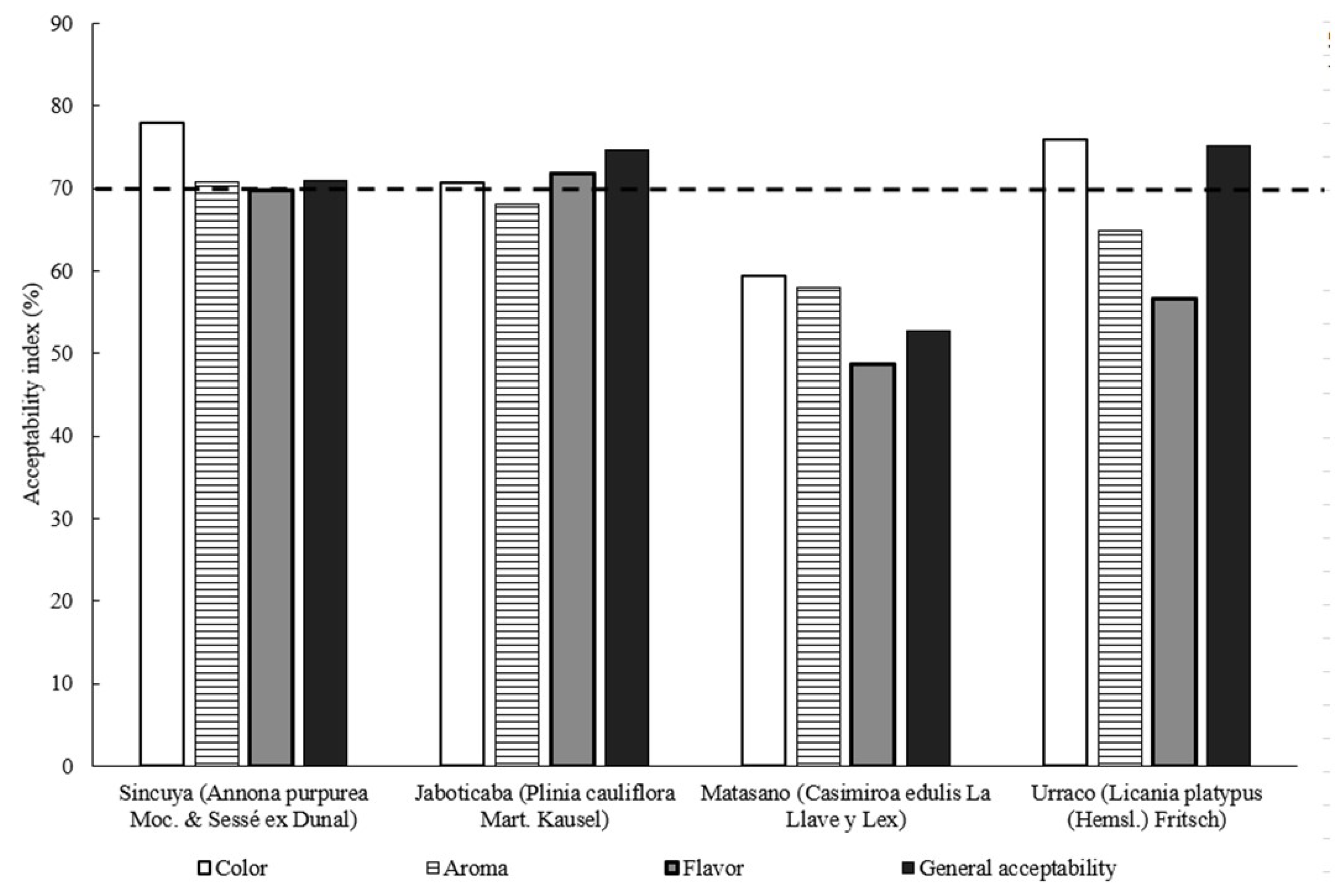

3.4. Sensory Characteristics of Beverages

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- B. T. Nguyen, E. Bujna, N. Fekete, and A. T. M. Tran, “Probiotic beverage from pineapple juice fermented with Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains,” Front Nutr, vol. 6, no. 54, pp. 1–7, 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Shori, “Proteolytic activity, antioxidant, and α-Amylase inhibitory activity of yogurt enriched with coriander and cumin seeds,” Lwt, vol. 133, no. 109912, pp. 1–10, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Meenu et al., “The golden era of fruit juices-based probiotic beverages: Recent advancements and future possibilities,” Process Biochemistry, vol. 142, pp. 113–135, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. & Markets., “Probiotic market – advanced technologies and global market (2022-2027),” 2022, Web. [Online]. Available: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/probiotics-market-69.html.

- K. O. P. Inada et al., “Screening of the chemical composition and occurring antioxidants in jabuticaba (Myrciaria jaboticaba) and jussara (Euterpe edulis) fruits and their fractions,” J Funct Foods, vol. 17, pp. 422–433, 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Yahia, M. Maldonado, and M. Svendsen, “Chemistry and biological functions,” in Fruit and vegetable phytochemicals: chemistry and human health, E. M. Yahia, Ed., 2017, pp. 3–52.

- J. Harris et al., “Fruit and vegetable biodiversity for nutritionally diverse diets: Challenges, opportunities, and knowledge gaps,” Glob Food Sec, vol. 33, p. 100618, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Camargo-Sanabria and E. Mendoza, “Interactions between terrestrial mammals and the fruits of two neotropical rainforest tree species,” Acta Oecologica, vol. 73, pp. 45–52, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Anaya-Esparza et al., “Annonas: underutilized species as a potential source of bioactive compounds,” Food Research International, vol. 138, no. 109775, pp. 1–18, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Khalil, H. A. Ismail, and W. F. Elkot, “Physicochemical, functional and sensory properties of probiotic yoghurt flavored with white sapote fruit (Casimiroa edulis),” J Food Sci Technol, vol. 59, no. 9, pp. 3700–3710, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- de A. A. Fernandes, G. M. Maciel, W. V. Maroldi, D. G. Bortolini, A. C. Pedro, and C. W. I. Haminiuk, “Bioactive compounds, health-promotion properties and technological applications of Jabuticaba: A literature overview,” Measurement: Food, vol. 8, p. 100057, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Islam, S. Tabassum, G. Elisabeth, S. Alam, and M. Ashiqul, “Development of probiotic beverage using whey and pineapple ( Ananas comosus ) juice : Sensory and physico-chemical properties and probiotic survivability during in-vitro gastrointestinal digestion,” J Agric Food Res, vol. 4, no. 100144, pp. 1–7, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. N. F. Hamad and M. K. El-Nemr, “Development of guava probiotic dairy beverages : application of mathematical modelling between consumer acceptance degree and whey ratio,” Int J Sci Res Sci Technol, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 186–193, 2015, doi: IJSRST151544.

- L. Meena, B. Malini, T. S. Byresh, C. K. Sunil, A. Rawson, and N. Venkatachalapathy, “Ultrasound as a pre-treatment in millet-based probiotic beverage: It’s effect on Fermentation kinetics and beverage quality,” Food Chemistry Advances, vol. 4, no. 100631, pp. 1–10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. de Matos Reis et al., “Development of milk drink with whey fermented and acceptability by children and adolescents,” J Food Sci Technol, vol. 58, no. 7, pp. 2847–2852, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Gunness, O. Kravchuk, S. M. Nottingham, B. R. D. Arcy, and M. J. Gidley, “Postharvest biology and technology sensory analysis of individual strawberry fruit and comparison with instrumental analysis,” vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 164–172, 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Lloyd, F. Warner, J. Kennedy, and C. White, “Quantitative analysis of vitam c (L-Ascorbic Acid) by ion suppression Reversed phase cromatography,” Food Chem, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 257–268, 1998. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Wall, “Ascorbic acid, vitamin A, and mineral composition of banana (Musa sp.) and papaya (Carica papaya) cultivars grown in Hawaii,” Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 434–445, Aug. 2006. [CrossRef]

- del P. Sánchez-Camargo, L.-F. Gutiérrez, S. M. Vargas, H. A. Martinez-Correa, F. Parada-Alfonso, and C.-E. Narváez-Cuenca, “Valorisation of mango peel: Proximate composition, supercritical fluid extraction of carotenoids, and application as an antioxidant additive for an edible oil,” J Supercrit Fluids, vol. 152, p. 104574, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Jr Latimer, Official methods of analysis of AOAC International, 20ed ed., vol. 2. AOAC International, Rockville, MD, 2016, 2016.

- H. Santana, A. J. V. Alvarado, S. K. Espinoza, and S. B. L. Aguilar, “Sensorial Evaluation and Physical Chemical Characterization of a Beverage Based on Whey and <i>β</i>-Glucans as a Potential Prevention of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis,” Food Nutr Sci, vol. 15, no. 08, pp. 770–789, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. de Souza Neves Ellendersen, D. Granato, K. Bigetti Guergoletto, and G. Wosiacki, “Development and sensory profile of a probiotic beverage from apple fermented with Lactobacillus casei,” Eng Life Sci, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1–11, 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Resende Maldonado et al., “Study of the composition of mango pulp and whey for lactic fermented beverages,” Journal of Biotechnology and Biodiversity, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 350–358, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. de F. Silva et al., “Acceptability of tropical fruit pulps enriched with vegetal/microbial protein sources: viscosity, importance of nutritional information and changes on sensory analysis for different age groups,” J Food Sci Technol, vol. 56, no. 8, pp. 3810–3822, 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Jayasena and I. Cameron, “°Brix/acid ratio as a predictor of consumer acceptability of crimson seedless table grapes,” J Food Qual, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 736–750, 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Mennella, A. R. Reiter, and L. M. Daniels, “Vegetable and fruit acceptance during infancy: impact of ontogeny, genetics, and early experiences,” Advances in Nutrition, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 211–219, 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. D. Cömert, B. A. Mogol, and V. Gökmen, “Relationship between color and antioxidant capacity of fruits and vegetables,” Curr Res Food Sci, vol. 2, pp. 1–10, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. D. Cömert, B. A. Mogol, and V. Gökmen, “Relationship between color and antioxidant capacity of fruits and vegetables,” Curr Res Food Sci, vol. 2, pp. 1–10, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Palmer, “Regulation of potassium homeostasis,” Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1050–1060, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. O. Bello, O. S. Falade, S. R. A. Adewusi, and N. O. Olawore, “Fruits, Studies on the chemical compositions and anti nutrients of some lesser known Nigeria,” Afr J Biotechnol, vol. 7(21), pp. 3972–3979, 2008.

- Q. Faryadi, “The magnificent effect of magnesium to human health: a critical review,” International Journal of Applied, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 118–126, 2012.

- H. E. Theobald, “Dietary calcium and health,” Nutr Bull, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 237–277, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Saavedra and A. M. Prentice, “Nutrition in school-age children: a rationale for revisiting priorities,” Nutr Rev, vol. 81, no. 7, pp. 823–843, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Aslam, S. M. Muhammad, S. Aslam, and J. A. Irfan, “Vitamins: key role players in boosting up immune response-a mini review,” Vitamins & Minerals, vol. 6(1), pp. 1–8, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Choudhary, K. Sharma, and O. Silakari, “The interplay between inflammatory pathways and COVID-19: A critical review on pathogenesis and therapeutic options,” Microb Pathog, vol. 150, no. 104673, pp. 1–20, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Mojikon, M. Kasimin, A. Molujin, J. Gansau, and R. Jawan, “Probiotication of nutritious fruit and vegetable juices: an alternative to dairy-based probiotic functional products,” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 3457, pp. 1–26, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ventura and J. Mennella, “Innate and learned preferences for sweet taste during childhood,” Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 379–384, 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. Worku, H. Kurabachew, and Y. Hassen, “Probiotication of fruit juices by suplemented culture of lactobacillus acidophilus,” Inernational Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Research, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 935–940, 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Malo and E. A. Urquhart, “Fermented foods: use of starter cultures,” in Encyclopedia of food and health, B. Caballero, P. M. Finglas, and F. Toldrá, Eds., Oxford: Academic Press, 2016, pp. 681–685. [CrossRef]

- A. Rodrigues, M. B. T. Ortolani, and L. A. Nero, “Microbiological quality of yoghurt commercialized in Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil,” Afr J Microbiol Res, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 210–213, 2010.

- J. S. B. Figueiredo et al., “Sensory evaluation of fermented dairy beverages supplemented with iron and added by Cerrado fruit pulps,” Food Science and Technology (Brazil), vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 410–414, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Souza et al., “Elaboration, evaluation of nutritional information and physical-chemical stability of dairy fermented drink with caja-mango pulp,” Ciência Rural, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues de Andrade, T. Rodrigues Martins, A. Rosenthal, J. Tiburski Hauck, and R. Deliza, “Fermented milk beverage : formulation and process,” Ciência Rural, vol. 49, no. 03, pp. 1–12, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Neffe-Skocińska, A. Rzepkowska, A. Szydłowska, and D. Kołożyn-Krajewska, “Trends and Possibilities of the Use of Probiotics in Food Production,” in Alternative and Replacement Foods, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 65–94. [CrossRef]

- S. Koirala and A. K. Anal, “Probiotics-based foods and beverages as future foods and their overall safety and regulatory claims,” Future Foods, vol. 3, p. 100013, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Donkor, A. Henriksson, T. Vasiljevic, and N. P. Shah, “Probiotic strains as starter cultures improve angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity in soy yogurt,” J Food Sci, vol. 70, no. 8, pp. 375–381, 2005. [CrossRef]

- B. Shori, G. S. Aljohani, A. J. Al-zahrani, O. S. Al-sulbi, and A. S. Baba, “Viability of probiotics and antioxidant activity of cashew milk-based yogurt fermented with selected strains of probiotic Lactobacillus spp.,” Lwt, vol. 153, no. 112482, pp. 1–8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhao et al., “The bioaccessibility, bioavailability, bioactivity, and prebiotic effects of phenolic compounds from raw and solid-fermented mulberry leaves during in vitro digestion and colonic fermentation,” Food Research International, vol. 165, no. 112493, pp. 1–13, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu et al., “Effect of probiotic administration on gut microbiota and depressive behaviors in mice,” DARU J. Pharm. Sci., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 181–189, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Fruits | °Brix | pH | % Titratable acidity (w/w)a | °Brix/Titratable acidity | Color | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | C* | h | |||||

| Sincuya (Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal) | 10.1 ± 0.1 b | 4.5 ± 0.1 c | 0.25 ± 0.01 c | 39.90 ± 1.25 b | 55.42 | 18.6 | 46.11 | 49.72 | 1.19 |

| Jaboticaba (Plinia cauliflora Mart. Kausel) | 11.2 ± 0.5 b | 3.2 ± 0.1 d | 1.28 ± 0.03 a | 8.70 ± 0.31 d | 15.04 | 18.33 | 8.22 | 20.09 | 0.42 |

| Matasano (Casimiroa edulis La Llave y Lex) | 16.0 ± 0.5 a | 6.2 ± 0.1 b | 0.25 ± 0.01 c | 65.80 ± 0.31 a | 41.16 | 11.05 | 33.87 | 35.63 | 1.26 |

| Urraco (Licania platypus (Hemsl.) Fritsch) | 15.4 ± 0.4 a | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 0.40± 0.02 b | 30.60 ± 0.74 c | 48.14 | 15.55 | 53.75 | 55.95 | 1.29 |

| Nutrient | Sincuya (Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal) | Jaboticaba (Plinia cauliflora Mart. Kausel) | Matasano (Casimiroa edulis La Llave y Lex) | Urraco (Licania platypus (Hemsl.) Fritsch) | |

| Minerales (mg/100 g) K |

444.49 | 56.72 | 238.32 | 504.37 | |

| Fe | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.49 | |

| Mg | 7.49 | 2.74 | 8 | 12.17 | |

| Cu | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.32 | |

| Zn | 0.63 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.45 | |

| Mn | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.1 | |

| Ca | 5.26 | 2.41 | 4.1 | 5.92 | |

| P | 2.03 | 0.52 | 1.96 | 2.52 | |

| Vitamin C (mg/100 g) | 2.21 | 4.42 | 5.19 | 2.31 | |

| Vitamin A (UI/100 g) | 334.37 | 5.82 | - | 25.63 | |

| Beverage | ||||

| Sincuya (Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal) | Jaboticaba (Plinia cauliflora Mart. Kausel) | Matasano (Casimiroa edulis La Llave y Lex) | Urraco (Licania platypus (Hemsl.) Fritsch) | |

| Before fermenting | ||||

| °Brix | 11.3 ± 0.2 c | 8.3 ± 0.0 d | 13.2 ± 0.2 b | 15.9 ± 0.1 a |

| pH | 5.7 ± 0.0 b | 4.7 ± 0.0 d | 4.9 ± 0.0 c | 6.3± 0.0 a |

| % Titratable acidity (w/w)a | 0.25 ± 0.0 d | 0.31 ± 0.0 c | 0.54 ± 0.0 a | 0.38 ± 0.0 b |

| °Brix/Titratable acidity | 44.9 ± 0.33 d | 26.6 ± 0.53 b | 24.5 ± 0.14 a | 29.8 ± 1.0 c |

| After fermenting | ||||

| °Brix | 10.5 ± 0.3 b | 7.9 ± 0.2 c | 10.2 ± 0.2 b | 15.1 ± 0.2 a |

| pH | 3.9 ± 0.0 d | 4.4 ± 0.0 a | 4.1 ± 0.0 c | 4.3± 0.0 b |

| % Titratable acidity (w/w)a | 0.63 ± 0.0 b | 0.37 ± 0.0 c | 0.76 ± 0.0 a | 0.65 ± 0.0 b |

| °Brix/Titratable acidity | 16.8 ± 0.94 b | 21.3 ± 0.67 c | 13.5 ± 0.69 a | 16.6 ± 0.41 b |

| Log CFU/mL (after 9 hours) | 10.4 ± 0.0 b | 4.3 ± 0.2 d | 9.7 ± 0.1 c | 10.9 ± 0.0 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).