Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

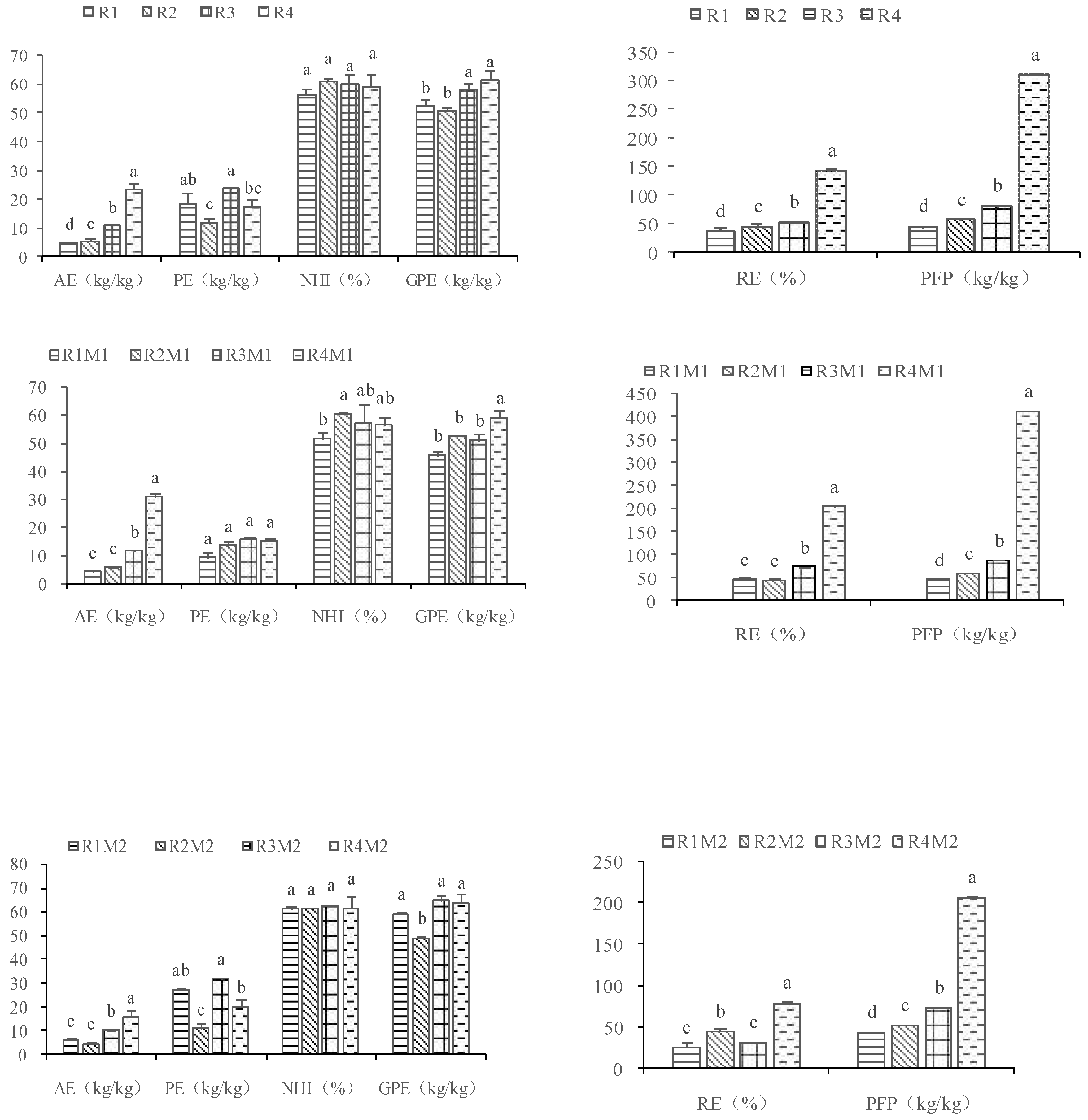

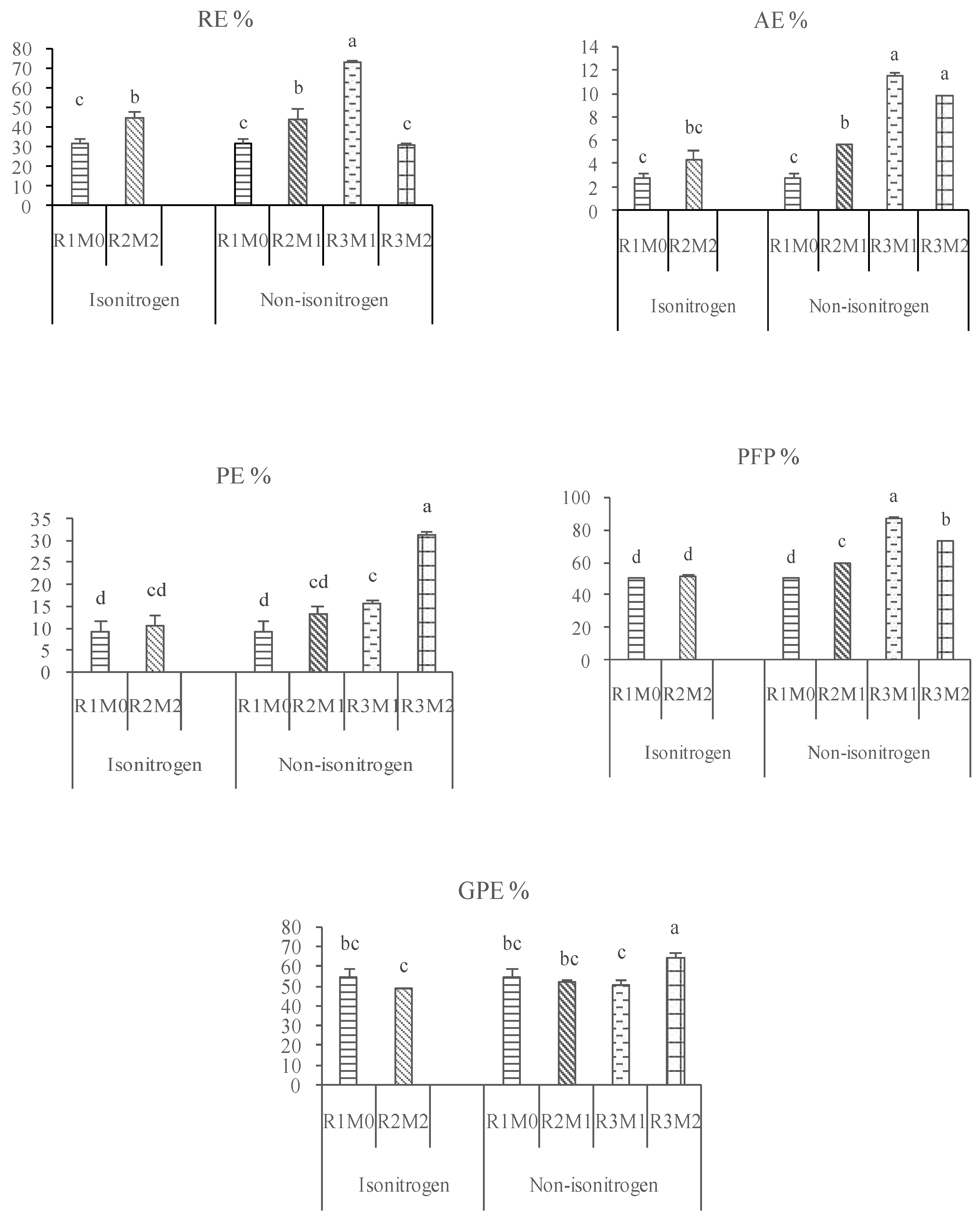

To investigate the effect of nitrogen reduction (NR) and combined application of organic fertilizer (OF) on nitrogen (N) utilization, yield, and quality of hybrid indica rice in the karst area, using rice ‘Yixiangyou 2115’ as the material, a split-plot design experiment of two factors of OF application rate as the main plots and NR rate as the subplots was carried out. The OF application rate had three levels: M0 (0 kg/ha), M1 (low OF, 1673 kg/ha), and M2 (high amount OF, 3346 kg/ha). The NR rate had four levels: R1 (NR rate 0%), R2 (NR rate 25%), R3 (NR rate 50%), and R4 (NR rate 100%). In this experiment, there were three modes of NR and OM application. Mode1: NR under the same amount of OM; Mode 2: NR and OM application under equal N conditions; and Mode 3: NR and combined application of OM under non-isonitrogen conditions. Rice yield was the highest under R3 in mode1. In modes 2 and 3, compared with single N fertilizer (R1M0), the yield of 25% NR combined with a high amount of OM (R2M2) increased significantly. In terms of yield components, under mode 1, with an increase in the N reduction rate, the effective panicle number showed a continuous decreasing trend, and the number of spikelets per panicle increased first and then decreased. The1000-grain weight and spikelet filling had no obvious change trend, but both were highest under R4. In modes 2 and 3, spikelet filling under NR combined with organic fertilizer treatment was higher than that of the single fertilizer treatment. In terms of N efficiency, in mode 1, with the increase in the N reduction rate, N recovery efficiency (RE), agronomic efficiency (AE), and partial factor productivity (PFP) showed a continuous increase trend, all of which were highest under R4. In mode 2, compared with R1M0, the RE of R2M2 significantly increased. In mode 3, compared with R1M0, the AE and PFP of 50% N reduction with low or high amounts of organic fertilizer were significantly increased. In terms of rice processing quality, in mode 1, as the N reduction rate improved, the milled rice rate and head rice rate continued to decline, but in modes 2 and 3, compared with the treatment of chemical fertilizer alone, the brown rice rate, milled rice rate, and head rice rate of the treatment of NR combined with OF improved. In terms of appearance quality and cooking nutritional quality of rice, under the same amount of OF, compared with no NR, the chalky degree and chalky rice rate of NR decreased, but gum consistency increased; meanwhile, under the condition of isonitrogen or non-nitrogen, compared with single N fertilization, the consistency of gel of the treatment of NR combined with OF increased. In summary, NR combined with OF fertilization mode was conducive to the improvement of N efficiency, yield, and quality of hybrid indica rice.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Materials.

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Measurement Items and Mathods

2.4.1. Measurement of Yield and Its Components

2.4.2. Determination of Plant N Content

2.4.3. Rice Quality Determination

2.4.4. Calculation of Relevant Indicators

3. Results

3.1. Yield and Its Composition

3.1.1. Yield

3.1.2. Yield Component Factors

3.2. N Efficiency

3.3. Rice Quality

3.3.1. Processing Quality

3.3.2. Appearance Quality

3.3.3. Cooking and nutritional quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, M, Feng, H, Chen, X. et al. Organic amendments with reduced chemical fertilizer promote soil microbial development and nutrient availability in a subtropical paddy field: The influence of quantity, type and application time of organic amendments. J. Applied Soil Ecology.42 (2) ,166-175(2009).. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.B. ,Huang, J. L. , Zhong, X. H.et al. Research Strategy in Improving Fertilizer-nitrogen Use Efficiency of Irrigated Rice in China. J. Scientia Agricultura Sinica.35(9),1095-1103 (2002)..

- Chen, H.F. , Yang, J. Research on the connotation of high-quality development of grain industry. J. Quality & Market. (01),59-61(2021).

- Ladha, J.K. ,Pathak, H, Krupnik, T. J.et al. Efficiency of Fertilizer Nitrogen in Cereal Production: Retrospects and Prospects. J. Advances in Agronomy.87,85-156(2005)..

- Zhang, F. S. ,Wang, J. Q. ,Zhang, W. F.et al. Nutrient use efficiencies of major cereal crops in China and measures for improvement. J. ActaPedologica Sinica.45(5):915-924 (2008)..

- Li, L.K. Research on the impact of production factor utilization on grain production increase and environmental impact. Ph.D. dissertation, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China(2015).

- Lu, N.W. Preliminary study on the effect of nitrogen reduction and organic fertilizer application in rice. Ph.D. dissertation, Northeast Agricultural University, Haerbin, Heilongjiang, China(2018).

- Mando, A ,Bonzi, M ,Wopereis, M. et al. Long-term effects of mineral and organic fertilization on soil organic matter fractions and sorghum yield under Sudano-Sahelian conditions. J. Soil Use & Management.21 (4) ,396-401(2010).. [CrossRef]

- Milkha, S. , Aulakh, et al. Denitrification, N2O and CO2 fluxes in rice-wheat cropping system as affected by crop residues, fertilizer N and legume green manure. J. Biology& Fertility of Soils (2001)..

- Tu, Q ,Zhang, Z ,Liu, M. Effect of Reducing Nitrogen and Applying Organic Fertilizer on Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Rice Yield in Red Soil Regions of the Southern China. J. Journal of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering.6 (1)(2021).. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q, Dang, S, Huang, X.l.et al. Research on combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizer-chemical fertilizer reduction technology. J. Northern rice. 52(04): 19-22(2022).

- Ding, H. X. ,Wu, X. Q. ,Lu, Y. Effects of combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizers on rice and wheat yield and soil quality. J. Zhejiang Agricultural Sciences. 62(03), 505-507(2021).

- Liu, H.J., Jiang, H.W., Sun, G.F.et al. Effects of Different Combined Application Ratios of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers on Nitrogen Uptake and Utilization Efficiency of Rice. J. Soil and Fertilizer in China. (05), 61-66(2017).

- Yu, Q.Q., Wang, H.F., Zhao, X.L. et al. Effects of combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizers on rice yield and nitrogen efficiency in Tongnanarea. J. Anhui Agricultural Sciences. 46(35), 137-139(2018).

- Yang, S.L., Hang, X.C., Li, Y.et al. Effects of long-term combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizers on rice growth, dry matter accumulation and yield. J. Zhejiang Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 34(09), 1815-1825(2022).

- Li, H. Study on nutrient accumulation and nitrogen use efficiency of rice with combined application of organic-inorganic fertilizer. Ph.D. dissertation, Northeast Agricultural University, Haerbin, Heilongjiang, China(2012).

- Hu, F. L. ,Yu, H. M. , Shen, B.S. Effects of nitrogen reduction and organic fertilizer on nitrogen efficiency and yield efficiency of rice in cold land. J. Northern rice. 50(01), 13-17(2020).

- Iqbal, A, He, L, Mcbride, S. G.et al. Manure Applications Combined With Chemical Fertilizer Improves Soil Functionality, Microbial Biomass and Rice Production in a Paddy Field. J.(2021).

- Ma B. Effects of organic fertilizer replacing part of nitrogen fertilizer on soil fertility and yield in subtropical paddy field. Ph.D. dissertation, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, Hunan, China(2017).

- Liu, Y.L., Li, Y, Bai, Y.J.et al. Effects of long-term different fertilization on dry matter and phosphorus accumulation and transport in rice. J. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science. 25(07),1146-1156 (2019).

- Zhang, W.J. Effects of combined organic-inorganic fertilizer application on crop growth and quality in rice/ryegrass rotation system. Ph.D. dissertation, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Huhehaote, Neimenggu, China(2021).

- Xu, W.B., Li, M, Luo, D.Q.et al. Effects of nitrogen reduction on yield and photosynthetic characteristics of machine-inserted hybrid indica rice. J. Soil and Fertilizer in China. (06),189-196(2021).

- Gu, W.W., Gu, S.P., Zhang ,Q.et al. Effects of organic-inorganic combined application on rice yield and yield composition factors. J. Shanghai Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 31(06), 95-100.24(2015).

- Zhao,J.H.,Zhang,C.Z.,Zhang, J.B. Effects of excited straw depth on soil nutrients and winter wheat yield. J. Journal of Soil Science. 53(02), 438-449(2016).

- Zhang, X.C., Dai, Q.G., Hu, X.X.et al. Effects of combined application of slow-release urea and conventional urea under soil with different textures on rice yield and growth and development. J. Acta Crops Sinica. 38(08), 1494-1503(2012).

- Wei, J, Guo, S.F., Zhai, L.M.et al. Effects of combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizers on nitrogen efficiency and nitrogen loss risk in rice. J. Soil. 50(05), 874-880(2018).

- Ren, T ,Wang, J ,Chen, Q , et al. The Effects of Manure and Nitrogen Fertilizer Applications on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen in a High-Input Cropping System. J. Plos One.9 (5) ,e97732(2014).. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.N., Zhou, H.P., Wen, Y.L.et al. Ecostoichiometric characteristics of nutrients and enzyme activities of clay soil under long-term different fertilization. J. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science. 28(06): 972-983(2022).

- Ren, Y, Shao, J.J., Lu, C.G.et al. Effects of fertilizer application on rice yield and nitrogen uptake.J. Zhejiang Agricultural Sciences. 62(08), 1486-1488(2021).

- He, X, Rong, X M, Xie, Y, et al. Effects of Fertilization Reduction and Organic Fertilizer Replacement on Rice Yield and Nutrient Utilization. J. Hunan Agricultural Sciences (2017)..

- Xi, M, Xu, Y.Z., Sun, X.Y.et al. Effect of nitrogen ear fertilizer on rice chalk white grain filling and its relationship with processing quality. J. China Agricultural Science and Technology Review. 23(09), 144-151(2021).

- Zhou, J.M. Effects of combined application of organic-inorganic fertilizer on yield, quality and nitrogen uptake of rice. J. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science. 18(01), 234-240(2012).

- Zhou, R.Q. Preliminary study on the effects of fertilizer types and nutrients on rice yield and quality. J. Crop Research. (01), 14-17(1988).

- Mo, Z.W., Li, W, Duan, M.Y.et al. Effects of potassium reduction on yield, quality and potassium absorption and utilization of morning and evening combined rice in South China. J. North China Journal of Agriculture. 29(01), 151-158(2014),.

- Nie J, Qiu J.R., Shi, L.L.et al. Effects of combined application of organic fertilizer and chemical fertilizer on yield, quality and potassium uptake and transport of dumped rice. J. Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences.44(02), 122-125(2016).

- Jiang, M.J., Xu, W.B., Wang, R.J.et al. Effects of nitrogen reduction on yield and rice quality of machine-inserted hybrid indica rice. J. Southern Journal of Agricultural Sciences.53(01), 104-114(2022).

- Shao, S.M. Effects of nitrogen reduction on yield and quality of different panicle japonica rice cultivars. Ph.D. dissertation, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China(2021).

| Treatment | EPN (m-2) | SPP | TGW (g) | SSR (%) | Grain yield (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1M1 | 201.39a | 189.23b | 33.44b | 76.50ab | 9388.01b |

| R2M1 | 192.59ab | 188.67b | 33.49b | 75.85ab | 9478.20b |

| R3M1 | 191.67ab | 218.16a | 33.41b | 72.83b | 9874.64a |

| R4M1 | 174.07b | 187.59b | 34.56a | 80.64a | 9275.61b |

| R1M2 | 190.74ab | 186.85a | 33.64b | 76.57b | 9858.30a |

| R2M2 | 200.00a | 187.72a | 33.54b | 75.59b | 9378.63b |

| R3M2 | 177.78b | 205.74a | 33.72b | 72.55b | 9912.98a |

| R4M2 | 183.33ab | 162.55b | 34.56a | 85.37a | 9279.53b |

| R1 | 196.06a | 188.04b | 33.54b | 76.54b | 9623.15b |

| R2 | 196.30a | 188.19b | 33.51b | 75.72b | 9428.41c |

| R3 | 184.72ab | 211.95a | 33.57b | 72.69b | 9893.81a |

| R4 | 178.70b | 175.07b | 34.56a | 83.00a | 9277.57d |

| R | 3.05 | 8.15** | 10.48** | 9.46** | 29.70** |

| R*M | 1.45 | 1.07 | 0.20 | 0.75 | 6.64** |

| Treatment | NARIF (kgN ha−1) |

NAROF (kgN ha−1) | TNAR (kgN ha−1) |

EPN(m−2) | SPP | TGW (g) | SSR (%) | Harvest yield (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1M0 | 180 | 0 | 180 | 180.56a | 196.44a | 33.37a | 67.30b | 9083.61c |

| R2M0 | 135 | 0 | 135 | 182.64a | 187.41a | 33.55a | 67.93b | 9937.53a |

| R2M1 | 135 | 22.5 | 157.5 | 192.59a | 188.67a | 33.49a | 75.85a | 9478.20b |

| R3M1 | 90 | 22.5 | 112.5 | 191.67a | 218.16a | 33.41a | 72.83ab | 9874.64a |

| R2M2 | 135 | 45 | 180 | 200.00a | 187.72a | 33.54a | 75.59a | 9378.63b |

| R3M2 | 90 | 45 | 135 | 177.78a | 205.74a | 33.72a | 72.55ab | 9912.98a |

| Treatment | BRR(%) | MRR(%) | HRR(%) |

| R1M1 | 78.071a | 71.134a | 45.293a |

| R2M1 | 78.189a | 70.337a | 42.952a |

| R3M1 | 77.827a | 68.401b | 42.005ab |

| R4M1 | 77.959a | 66.986b | 38.335b |

| R1M2 | 78.230a | 71.148a | 47.474a |

| R2M2 | 78.229a | 71.315a | 42.289b |

| R3M2 | 77.927a | 70.862a | 45.876ab |

| R4M2 | 77.009a | 70.257a | 43.920ab |

| R1 | 78.150a | 71.141a | 46.384a |

| R2 | 78.209a | 70.826ab | 42.621b |

| R3 | 77.877a | 69.631bc | 43.941ab |

| R4 | 77.484a | 68.622c | 41.127b |

| R | 0.89 | 7.16** | 4.66* |

| R*M | 0.56 | 2.86 | 1.66 |

| Treatment | NARIF (kgN ha−1) |

NAROF (kgN ha−1) |

TNAR (kgN ha−1) |

BRR(%) | MRR(%) | HRR(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1M0 | 180 | 0 | 180 | 77.11ab | 69.91ab | 43.28a |

| R2M0 | 135 | 0 | 135 | 78.26a | 70.90a | 45.87a |

| R2M1 | 135 | 22.5 | 157.5 | 78.19a | 70.34ab | 42.95cd |

| R3M1 | 90 | 22.5 | 112.5 | 75.37b | 68.40b | 42.01a |

| R2M2 | 135 | 45 | 180 | 78.23a | 71.32a | 42.29a |

| R3M2 | 90 | 45 | 135 | 77.93a | 70.86a | 45.88a |

| Treatment | CD(%) | CR(%) | LWR |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1M1 | 16.322a | 40.082a | 2.970a |

| R2M1 | 15.042ab | 39.258a | 2.967a |

| R3M1 | 13.015b | 34.640a | 2.959a |

| R4M1 | 13.067b | 35.028a | 2.964a |

| R1M2 | 13.282a | 34.002a | 2.959a |

| R2M2 | 14.015a | 35.830a | 2.961a |

| R3M2 | 13.757a | 35.592a | 2.964a |

| R4M2 | 11.690a | 31.840a | 2.949a |

| R1 | 14.802a | 37.042ab | 2.965a |

| R2 | 14.528a | 37.544a | 2.964a |

| R3 | 13.386ab | 35.116ab | 2.961a |

| R4 | 12.378b | 33.434b | 2.956a |

| R | 2.91 | 2.08 | 0.36 |

| R*M | 1.41 | 1.24 | 0.47 |

| Treatment | NARIF (kgN ha−1) |

NAROF (kgN ha−1) |

TNAR (kgN ha−1) |

CD(%) | CR(%) | LWR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1M0 | 180 | 0 | 180 | 14.268a | 37.412a | 2.948a |

| R2M0 | 135 | 0 | 135 | 15.965a | 40.367a | 2.957a |

| R2M1 | 135 | 22.5 | 157.5 | 15.042a | 39.258a | 2.967a |

| R3M1 | 90 | 22.5 | 112.5 | 13.015a | 34.640a | 2.959a |

| R2M2 | 135 | 45 | 180 | 14.015a | 35.830a | 2.961a |

| R3M2 | 90 | 45 | 135 | 13.757a | 35.592a | 2.964a |

| Treatment | AC(%) | GC(mm) | ASV | PC(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1M1 | 15.647b | 63.500a | 5.639a | 9.562a |

| R2M1 | 15.882b | 67.333a | 5.722a | 9.090ab |

| R3M1 | 16.514b | 69.167a | 5.833a | 8.243bc |

| R4M1 | 18.846a | 72.333a | 5.333a | 7.461c |

| R1M2 | 16.287a | 69.667ab | 5.861a | 8.755a |

| R2M2 | 16.114a | 66.000b | 5.611a | 8.721a |

| R3M2 | 16.453a | 73.833ab | 5.778a | 8.392a |

| R4M2 | 16.799a | 78.667a | 5.889a | 6.562b |

| R1 | 15.967b | 66.583b | 5.750a | 9.158a |

| R2 | 15.998b | 66.667b | 5.667a | 8.905ab |

| R3 | 16.484ab | 71.500ab | 5.806a | 8.318b |

| R4 | 17.823a | 75.500a | 5.611a | 7.011c |

| R | 3.38* | 2.51 | 0.44 | 15.05** |

| R*M | 1.59 | 0.44 | 1.37 | 0.94 |

| Treatment | NARIF (kgN ha−1) |

NAROF (kgN ha−1) |

TNAR (kgN ha−1) |

AC(%) | GC(mm) | ASV | PC(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1M0 | 180 | 0 | 180 | 16.122a | 63.667a | 5.917a | 8.934a |

| R2M0 R2M1 |

135 135 |

0 22.5 |

135 157.5 |

15.602a 15.882a |

67.883a 67.333a |

5.694a 5.722a |

8.843a 9.090a |

| R3M1 R2M2 |

90 135 |

22.5 45 |

115.5 180 |

16.514a 16.114a |

69.167a 66.000a |

5.833a 5.611a |

8.243a 8.721a |

| R3M2 | 90 | 45 | 135 | 16.453a | 73.833a | 5.778a | 8.392a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).