Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Theoretical Framework

Ethical Leadership, Autonomy and Self-Efficacy

Ethical Leadership and Job Self-Efficacy

Ethical Leadership, Egoistic Ethical Climate, and Self-Efficacy

Methods

Participants

Instruments

Procedure

Data Analysis

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Practical Implications

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Markey:, K. , Ventura, C. A. A., Donnell, C. O., & Doody, O. Cultivating ethical leadership in the recovery of COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Management 2021, 29, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and creativity within the Colombian electricity sector. The mediating role of work autonomy, affective commitment, and intrinsic motivation. Revista iberoamericana de estudios de desarrollo= Iberoamerican journal of development studies 2023, 12, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal-Chérif, O. , Guijarro-García, M., Ballester-Miquel, J. C., & Carrilero-Castillo, A. Being an ethical leader during the apocalypse: Lessons from the walking dead to face the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Business Research 2021, 133, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R. L. Ethical leadership and its impact on service innovative behavior: The role of LMX and job autonomy. Tourism Management 2016, 57, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Aguirre, M. , Campoverde Aguirre, R., Hernandez-Pozas, O., Ayala, Y., & Barriga Medina, H. The Digital Self-Efficacy Scale: Adaptation and Validation of its Spanish Version. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Wattoo, M. A. , Zhao, S., & Xi, M. High-performance work systems and work–family interface: job autonomy and self-efficacy as mediators. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2020, 58, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M. , Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. M., & Nielsen, K. The impact of group efficacy beliefs and transformational leadership on followers’ self-efficacy: a multilevel-longitudinal study. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 2024–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, M. , Ingusci, E., Cortese, C. G., Giancaspro, M. L., Manuti, A., Molino, M., Signore, F., & Russo, V. Does the End Justify the Means? The Role of Organizational Communication among Work-from-Home Employees during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, E. C. , Tanner, J. F., & Wakefield, K. Panacea or paradox? The moderating role of ethical climate. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 2015, 35, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brändle, L. , Berger, E. S. C., Golla, S., & Kuckertz, A. I am what I am - How nascent entrepreneurs’ social identity affects their entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 2018, 9, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H. , Williams, K. A., Ramayah, T., Aldieri, L., & Vinci, C. P. Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: the moderating role of person–organization fit. Personnel Review 2021, 50, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. R. E-ethical leadership for virtual project teams. International Journal of Project Management 2009, 27, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, A. v. , van Wart, M., Wang, X., Liu, C., Kim, S., & McCarthy, A. Defining E-leadership as Competence in ICT-Mediated Communications: An Exploratory Assessment. Public Administration Review 2019, 79, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziner, A. , Felea, M., & Vasiliu, C. Relating ethical climate, organizational justice perceptions, and leader-member exchange (LMX) in Romanian organizations. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones 2015, 31, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsira, M. , Denkers, A., & Huisman, W. Both Sides of the Coin: Motives for Corruption Among Public Officials and Business Employees. Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 151, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D. , van Dick, R., Tenbrunsel, A., Pillutla, M., & Murnighan, J. K. Understanding Ethical Behavior and Decision Making in Management: A Behavioural Business Ethics Approach. British Journal of Management 2011, 22, S1–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaman, J. M. , Gondo, M. B., & Allen, D. G. Ethical climate and pro-social rule breaking in the workplace. Human Resource Management Review. [CrossRef]

- Frazier, M. L. , & Jacezko, M. C. Leader Machiavellianism as an Antecedent to Ethical Leadership: The Impact on Follower Psychological Empowerment and Work Outcomes. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 2021, 28, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Keefe, D. F. , Peach, J. M., & Messervey, D. L. The combined effect of ethical leadership, moral identity, and organizational identification on workplace behavior. Journal of Leadership Studies 2019, 13, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dust, S. B. , Resick, C. J., Margolis, J. A., Mawritz, M. B., & Greenbaum, R. L. Ethical leadership and employee success: Examining the roles of psychological empowerment and emotional exhaustion. The Leadership Quarterly 2018, 29, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A. , Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. A Meta-analytic Review of Ethical Leadership Outcomes and Moderators. Journal of Business Ethics 2016, 139, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. , Baranchenko, Y., An, F., Lin, Z., & Ma, J. The impact of ethical leadership on employee creative deviance: the mediating role of job autonomy. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 2020, 42, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väänänen, A. , Toivanen, M., & Lallukka, T. Lost in Autonomy – Temporal Structures and Their Implications for Employees’ Autonomy and Well-Being among Knowledge Workers. Occupational Health Science 2020, 4, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedahanov, A. T. , Rhee, C., & Gapurjanova, N. Job autonomy and employee voice: is work-related self-efficacy a missing link? Management Decision 2019, 57, 2401–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, I. , & Salgado, E. When deeds speak, words are nothing: a study of ethical leadership in Colombia. Business Ethics: A European Review 2016, 25, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. , Naseem, A., & Masood, S. A. Effect of Continuance Commitment and Organizational Cynicism on Employee Satisfaction in Engineering Organizations. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Gencoglu, M. , & Dinc, M. S. (2017). "Ethical Climate, Job Satisfaction, and Effective Commitment relationship in the Shoes Manufacturing Sector ". [CrossRef]

- Saygili, M. , Özer, Ö., & Karakaya, P. Ö. Paternalistic Leadership, Ethical Climate and Performance in Health Staff. Hospital Topics 2020, 98, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalshoven, K. , den Hartog, D. N., & de Hoogh, A. H. B. Ethical leadership and followers’ helping and initiative: The role of demonstrated responsibility and job autonomy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2013, 22, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F. , Baykal, E., & Abid, G. E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and Beyond: What We Know and Where Do We Go. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, A. , Tirado, F., & Martínez, M. J. Work–Life Balance, Organizations and Social Sustainability: Analyzing Female Telework in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janfada, M. Enriching ethical leadership in higher education as advanced learning. Journal of Leadership Studies 2017, 11, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. , Lin, L., & Liu, J. T. Leveraging the employee voice: a multi-level social learning perspective of ethical leadership. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2019, 30, 1869–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Fearful expectations and avoidant actions as coeffects of perceived self-inefficacy. American Psychologist 1986, 41, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. , Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. Self-Efficacy Beliefs as Shapers of Children’s Aspirations and Career Trajectories. Child Development 2001, 72, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B. , Albrecht, S. L., & Leiter, M. P. Work engagement: Further reflections on the state of play. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2011, 20, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudiana, K. , & Saputra, N. The Role of e-Leadership on the Productivity of Virtual Work in Higher Education. 2021 Universitas Riau International Conference on Education Technology (URICET). [CrossRef]

- Javed, B. , Rawwas, M. Y. A., Khandai, S., Shahid, K., & Tayyeb, H. H. Ethical leadership, trust in leader and creativity: The mediated mechanism and an interacting effect. Journal of Management & Organization 2018, 24, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthely, L. M. Individual flourishing and spiritual leadership: An approach to ethical leadership. Journal of Leadership Studies 2017, 11, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, R. Ancient wisdom for ethical leadership: Ubuntu and the ethic of ecosophy. Journal of Leadership Studies 2020, 13, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, N. , & Isha, A. S. N. B. Identifying the Moderating Effect of Hyperconnectivity on the Relationship between Job Demand Control Imbalance, Work-to-Family Conflict, and Health and Well-Being of Office Employees Working in the Oil and Gas Industry, Malaysia. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Darics, E. E-Leadership or “How to Be Boss in Instant Messaging?” The Role of Nonverbal Communication. International Journal of Business Communication 2020, 57, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, P. C. N. , Leal, S. E., Lopes, I., Cascão, A. F., & Gomes, P. (2022). Transformational and Authentic Leadership in Telework. [CrossRef]

- Segbenya, M. , & Okorley, E. N. A. Effect of teleworking on working conditions of workers: A post-COVID-19 lockdown evaluation. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Afshar Jahanshahi, A. , Rivas, M. I. M., & Castillo, A. Y. Q. The Outcomes of Organizational Fairness among Precarious Workers: The Critical Role of Anomie at the Work. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Saha, R. , Shashi, Cerchione, R., Singh, R., & Dahiya, R. Effect of ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility on firm performance: A systematic review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2020, 27, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S. , & Chadee, D. Ethical leadership, self-efficacy and job satisfaction in China: the moderating role of guanxi. Personnel Review 2017, 46, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toleikienė, R. , Rybnikova, I., & Juknevičienė, V. Whether and How Does the Crisis-Induced Situation Change E-Leadership in the Public Sector? Evidence from Lithuanian Public Administration. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F. , Abid, G., & Ilyas, S. Impact of Ethical Leadership on Employee Engagement: Role of Self-Efficacy and Organizational Commitment. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2021, 11, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latta, G. F. , & Clottey, E. N. Ethical leadership: Understanding ethical failures and researching consequences for practice: Priority 8 of the National Leadership Education Research Agenda 2020–2025. Journal of Leadership Studies 2020, 14, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, R. W. , Allen, D. G., Fedor, D. B., & Davis, W. D. The Roles of Personality and Self-Defeating Behaviors in Self-Management Failure. Journal of Management 2005, 31, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W. Doing the Job Well: An Investigation of Pro-Social Rule Breaking. Journal of Management 2006, 32, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, S. , Botha, P., & Rose-Innes, R. Organizational Behaviour: Exploring The Relationship Between Ethical Climate, Self-Efficacy and Hope. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 2015, 31, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumusluoglu, L. , Karakitapoğlu-Aygün, Z., & Hu, C. Angels and devils?: How do benevolent and authoritarian leaders differ in shaping ethical climate via justice perceptions across cultures? Business Ethics: A European Review 2020, 29, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-Y. , & Wang, L. The Mediating Effect of Ethical Climate on the Relationship Between Paternalistic Leadership and Team Identification: A Team-Level Analysis in the Chinese Context. Journal of Business Ethics 2015, 129, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozavize Ayodele, F. , Binti Haron, H., & Ismail, I. (2019). Ethical Leadership, Ethical Leadership Climate and Employee Moral Effectiveness: A Social Learning Perspective. KnE Social Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Morris, L. R. Finding inner harmony in the paradoxical coexistence of leadership innovation and ethics. Journal of Leadership Studies 2016, 10, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, A. , & Achen, R. M. Explicating the synergies of self-determination theory, ethical leadership, servant leadership, and emotional intelligence. Journal of Leadership Studies 2018, 12, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M. , & MacMillan, I. C. Entrepreneurial Behavior: A Reconceptualization and Extension Based on Identity Theory. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2017, 11, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, R. , Tramontano, C., Paciello, M., Ghezzi, V., & Barbaranelli, C. Understanding the Interplay Among Regulatory Self-Efficacy, Moral Disengagement, and Academic Cheating Behaviour During Vocational Education: A Three-Wave Study. Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 153, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. E. , Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J. , Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, L., & Han, X. Just the Right Amount of Ethics Inspires Creativity: A Cross-Level Investigation of Ethical Leadership, Intrinsic Motivation, and Employee Creativity. Journal of Business Ethics 2018, 153, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Academy of Management Journal 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C. Y., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey. En C. Maslach, S.E. Jackson y M.P. Leiter (Eds.) The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Test Manual (3rd ed.) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Salanova, M. , & Schaufeli, W. B. Exposure to information technology and its relation to burnout. Behaviour & Information Technology 2000, 19, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B. , & Cullen, J. B. The Organizational Bases of Ethical Work Climates. Administrative Science Quarterly 1988, 33, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023b). Ethical Climate and Creativity: The Moderating Role of Work Autonomy and the Mediator Role of Intrinsic Motivation. Cuadernos de Gestión. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. Software Review: Software Programs for Structural Equation Modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 1998, 16, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. , & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M. , & Balážová, Ž. The Impact of Age, Education and Seniority on Motivation of Employees. Verslas: Teorija Ir Praktika 2015, 16, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research (pp. 295–358). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hair, J. F. , Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P. , Yi, Y., & Nassen, K. D. Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. Journal of Econometrics 1998, 89, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. , & Larcker, D. F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumjaun, A. , & Narod, F. (2020). Social Learning Theory—Albert Bandura. [CrossRef]

- Mihalca, L. , Lucia Ratiu, L., Brendea, G., Metz, D., Dragan, M., & Dobre, F. (2021). Exhaustion while teleworking during COVID-19: a moderated-mediation model of role clarity, self-efficacy, and task interdependence. Oeconomia Copernicana. [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F. O. , Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. L. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 2011, 115, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikeleze, M. C. , & Baehrend Jr, W. R. Ethical leadership style and its impact on decision-making. Journal of leadership studies 2017, 11, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. , Lin, W., Wu, J., Zheng, Q., Chen, X., & Jiang, X. Ethical Leadership and Knowledge Sharing: The Effects of Positive Reciprocity and Moral Efficacy. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 215824402110218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyousfi, F. , Anand, A., & Dalmasso, A. Impact of e-leadership and team dynamics on virtual team performance in a public organization. International Journal of Public Sector Management 2021, 34, 508–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardane, S. D. , & Jayawardana, A. K. L. Factors affecting Virtual Team Performance: A Theoretical Integration. Journal of Management and Research. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D. M. , Kuenzi, M., & Greenbaum, R. L. Examining the Link Between Ethical Leadership and Employee Misconduct: The Mediating Role of Ethical Climate. Journal of Business Ethics 2010, 95, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özden, D. , Arslan, G. G., Ertuğrul, B., & Karakaya, S. The effect of nurses’ ethical leadership and ethical climate perceptions on job satisfaction. Nursing Ethics 2019, 26, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atshan, N. A. , Al-Abrrow, H., Abdullah, H. O., Khaw, K. W., Alnoor, A., & Abbas, S. The effect of perceived organizational politics on responses to job dissatisfaction: The moderating roles of self-efficacy and political skill. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 2022, 41, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. , Miao, Q., Jameel, A., Manzoor, F., & Hussain, A. How ethical leadership influence employee creativity: A parallel multiple mediation model. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 3021–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L. Moving from a compliance-based to an integrity-based organizational climate in the food supply chain. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19, 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M. , & Hassan, S. The need for ethical leadership in combating corruption. International Review of Administrative Sciences 2020, 86, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A. A. Creating safer workplaces: The role of ethical leadership. Safety Science 2015, 73, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. , Mahmood, F., Sarwar, N., Obaid, A., Memon, M. A., & Khaskheli, A. (2022). Ethical leadership: Exploring bottom-line mentality and trust perceptions of employees on middle-level managers. Current Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A. K. , & Agrawal, R. K. (2022). It’s a knowledge centric world! Does ethical leadership promote knowledge sharing and knowledge creation? Psychological capital as mediator and shared goals as moderator. Journal of Knowledge Management. [CrossRef]

- Nunn, S. G. , & Avella, J. T. Does moral leadership conflict with organizational innovation. Journal of Leadership Studies 2015, 9, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletzer, J. L. , Voelpel, S. C., & van Lange, P. Selfishness Facilitates Deviance: The Link Between Social Value Orientation and Deviant Behavior. Academy of Management Proceedings 2018, 2018, 12354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, C. , Lydon, S., Kelly, M. E., Murphy, A. W., & O’Connor, P. An analysis of general practitioners’ perspectives on patient safety incidents using critical incident technique interviews. Family Practice 2019, 36, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Leadership styles and knowledge workers’ work engagement: Psychological capital as a mediator. Current Psychology 2019, 38, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M. , Abid, G., & Torres, F. V. C. Impact of prosocial motivation on organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating role of ethical leadership and leader–member exchange. Quality & Quantity 2021, 55, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensap, A. , Virakul, B., Senasu, K., & Ayman, R. Effect of ethical leadership and interactional justice on employee work attitudes. Journal of leadership studies 2019, 12, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babič, K. , Černe, M., Connelly, C. E., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. Are we in this together? Knowledge hiding in teams, collective prosocial motivation and leader-member exchange. Journal of Knowledge Management 2019, 23, 1502–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. , & Rojas-Espinosa, S. R. Pandemia COVID-19 y compromiso laboral: relación dentro de una organización del sector eléctrico colombiano. Revista de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación 2021, 11, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I. , & Grant-Vallone, E. J. Understanding Self-Report Bias in Organizational Behavior Research. Journal of Business and Psychology 2002, 17, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. , Corral-Marfil, J. A., & Tarrats-Pons, E. Relationship between Personal Ethics and Burnout: The Unexpected Influence of Affective Commitment. Administrative Sciences 2024, 14, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. , Corral-Marfil, J. A., & Tarrats-Pons, E. The Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion in a Virtual Work Environment: A Moderated Mediation Model. Systems 2024, 12, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. , González-Carrasco, M. , & Miranda Ayala, R. A. Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion: The Impact of Moral Intensity and Affective Commitment. Administrative Sciences 2024, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Creativity and Emotional Exhaustion in Virtual Work Environments: The Ambiguous Role of Work Autonomy. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2024, 14, 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Constructs | N | M | SD | 1 | 2 | EL | EC | SE | JA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | 0.39 | 0.488 | ||||||

| Seniority | 1 | 3.58 | 1.839 | -0.038 | |||||

| Ethical Leadership (EL) | 10 | 49.62 | 10.130 | -0.049 | -0.113* | (0.830) | |||

| Egoistic Ethical Climate (EC) | 14 | 55.60 | 8.912 | -0.082 | -0.193** | 0.084* | (0.590) | ||

| Self-efficacy (SE) | 6 | 29.81 | 3.923 | 0.001 | 0.195** | 0.314** | 0.104* | (0.810) | |

| Job Autonomy (JA) | 3 | 14.91 | 2.560 | -0.039 | 0.100* | 0.180** | 0.074 | 0.368** | (0.890) |

| ALPHA1 | CR2 | CFC3 | AVE4 | DV5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egoistic Ethical Climate | 0.77 | > 1.96 | 0.730 | 0.350 | 0.590 |

| Ethical Leadership | 0.92 | > 1.96 | 0.830 | 0.690 | 0.830 |

| Job Self-efficacy | 0.89 | > 1.96 | 0.860 | 0.650 | 0.810 |

| Job Autonomy | 0.87 | > 1.96 | 0.850 | 0.790 | 0.890 |

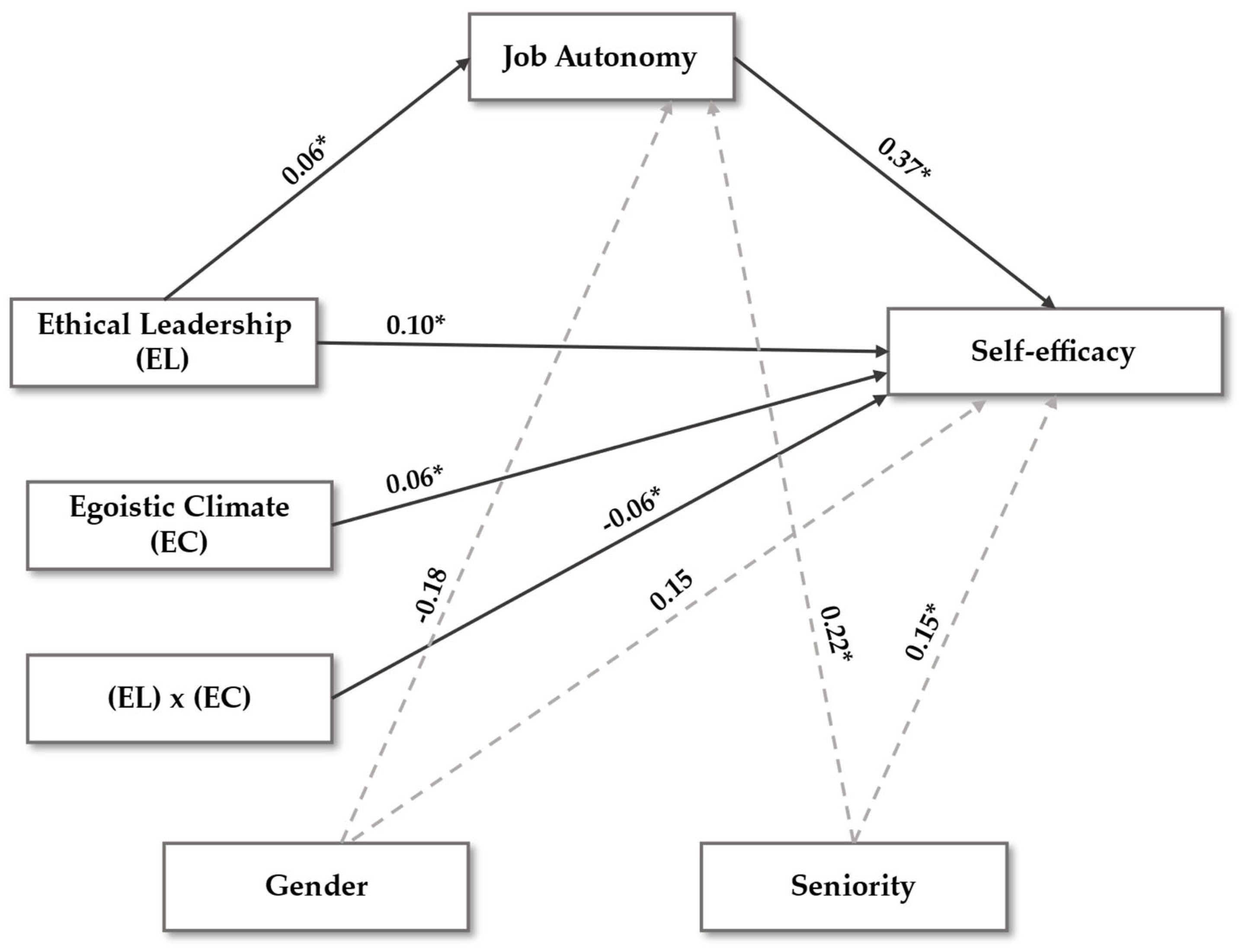

| Effect | Route | β | p | t | ES | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Effect EL1 vs JA2 | a1 | 0.059 | 0.001 | 3.636 | 0.014 | 0.023 | 0.078 | |

| Gender Covariate vs JA | --- | -0.181 | 0.522 | -0.641 | 0.229 | -0.596 | 0.303 | |

| Seniority Covariate vs JA | --- | 0.220 | 0.017 | 2.402 | 0.062 | 0.027 | 0.273 | |

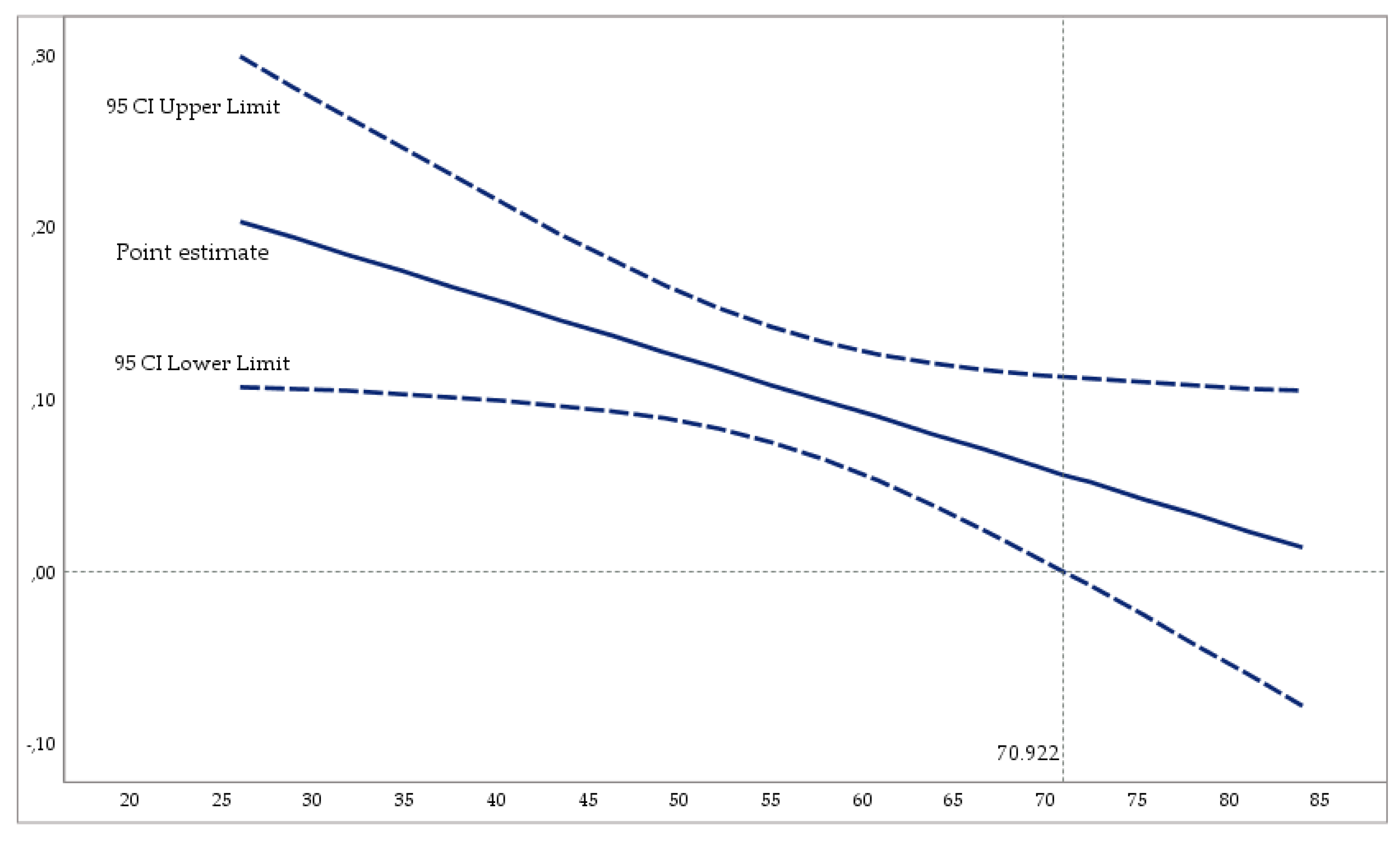

| Effect EL vs SE3 | c1’ | 0.104 | 0.001 | 3.302 | 0.087 | 0.117 | 0.459 | |

| Effect JA vs SE | b1 | 0.369 | 0.001 | 5.900 | 0.058 | 0.228 | 0.456 | |

| Effect EEC4 vs SE | c2’ | 0.056 | 0.023 | 2.276 | 0.082 | 0.025 | 0.346 | |

| Effect EL x EEC vs SE | c3’ | -0.061 | 0.034 | -2.129 | 0.034 | -0.013 | -0.001 | |

| Gender Covariate vs SE | --- | 0.152 | 0.558 | 0.586 | 0.277 | -0.382 | 0.706 | |

| Seniority Covariate vs SE | --- | 0.153 | 0.032 | 2.145 | 0.076 | 0.014 | 0.312 | |

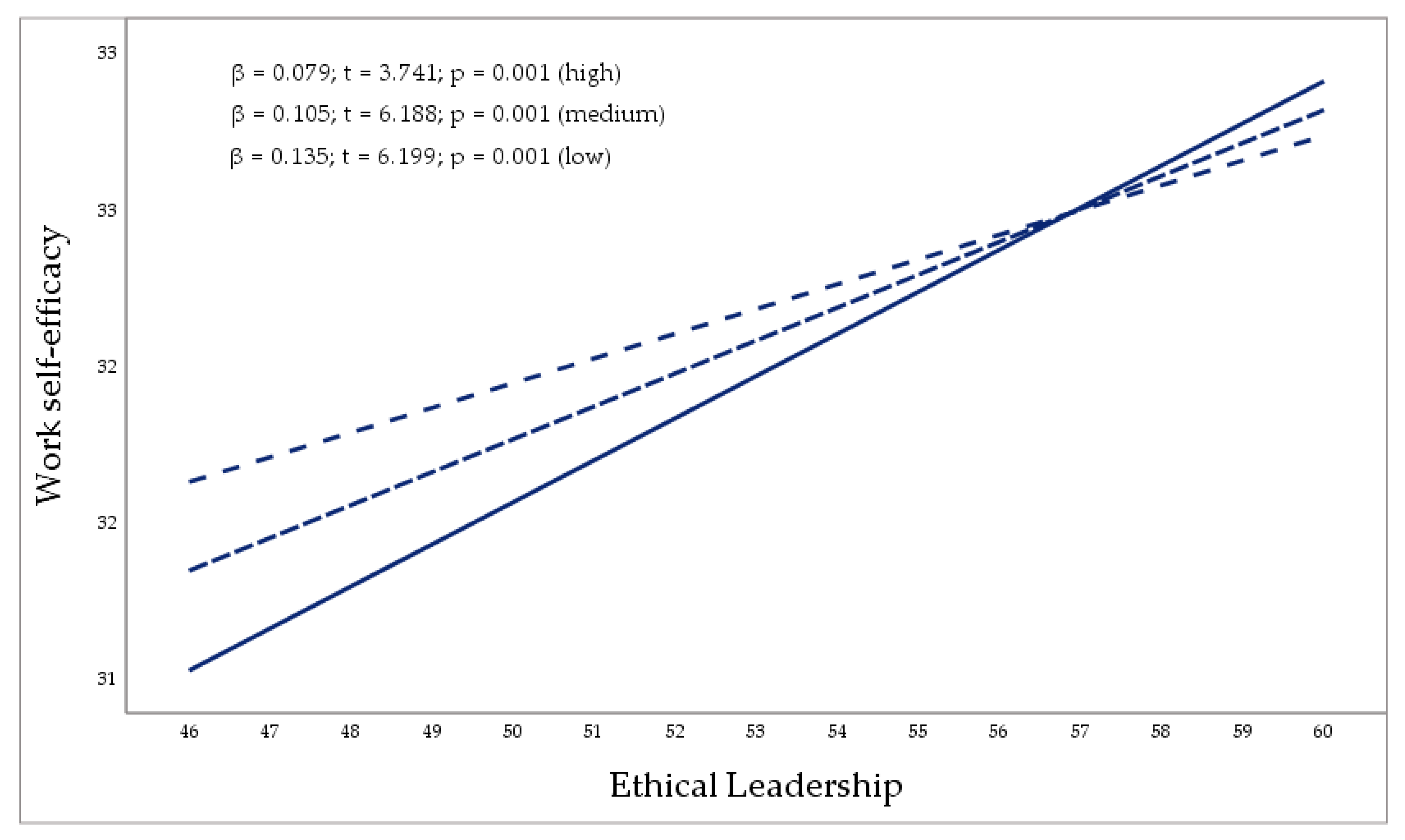

| Conditional Effect EEC (XY) | Low (47) | --- | 0.135 | 0.001 | 6.199 | 0.022 | 0.092 | 0.177 |

| Medium (56) | --- | 0.105 | 0.001 | 6.188 | 0.017 | 0.072 | 0.139 | |

| High (64) | --- | 0.079 | 0.001 | 3.741 | 0.021 | 0.038 | 0.121 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).