Submitted:

09 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

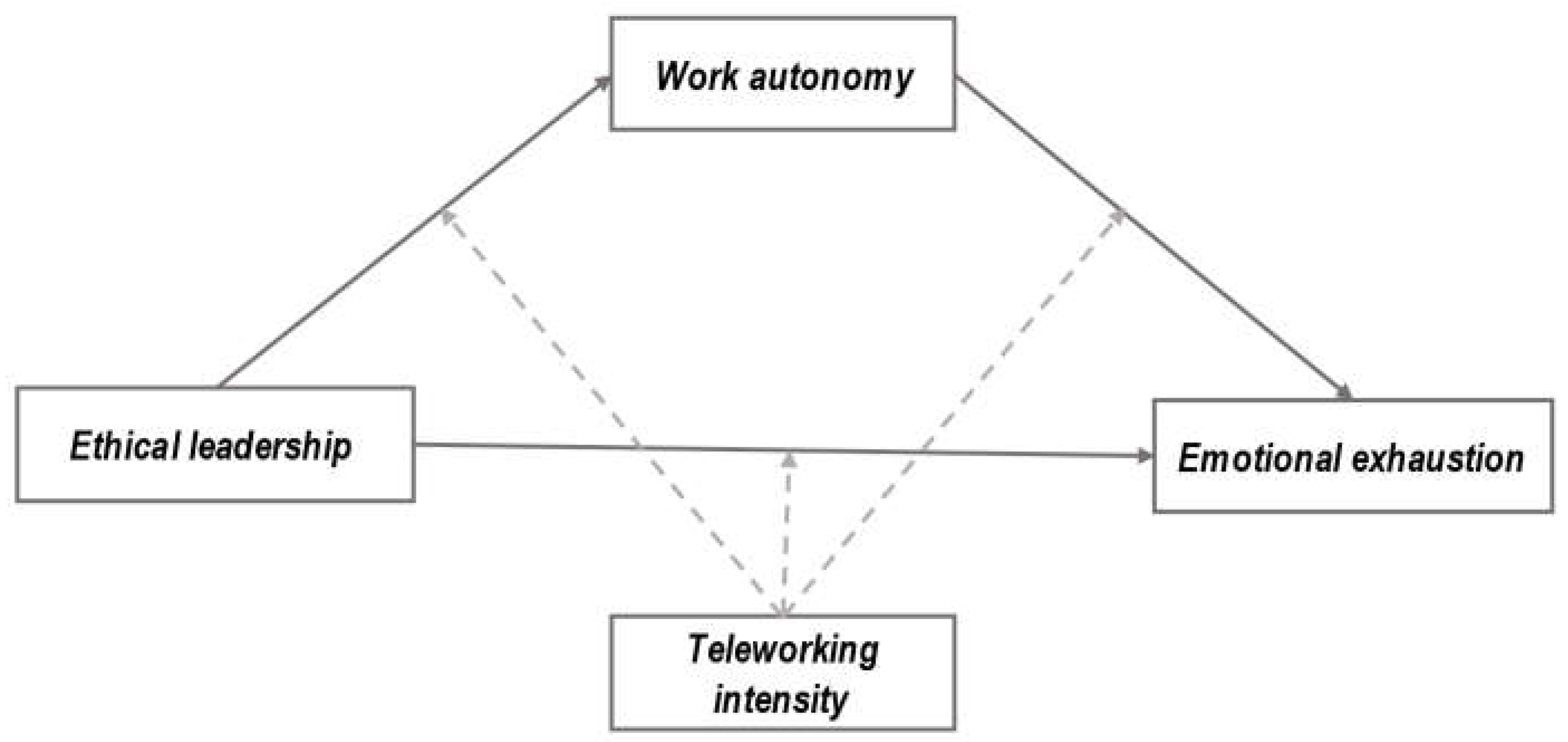

2. Relationship between Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion

3. The Mediating Role of Work Autonomy

4. The Moderating Role of Teleworking Intensity

5. Presentation of the Study

6. Methods

6.1. Participants

6.2. Measures

6.3. Procedure

6.4. Data Analysis

7. Results

7.1. Descriptive Statistics and Discriminant Validity

7.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

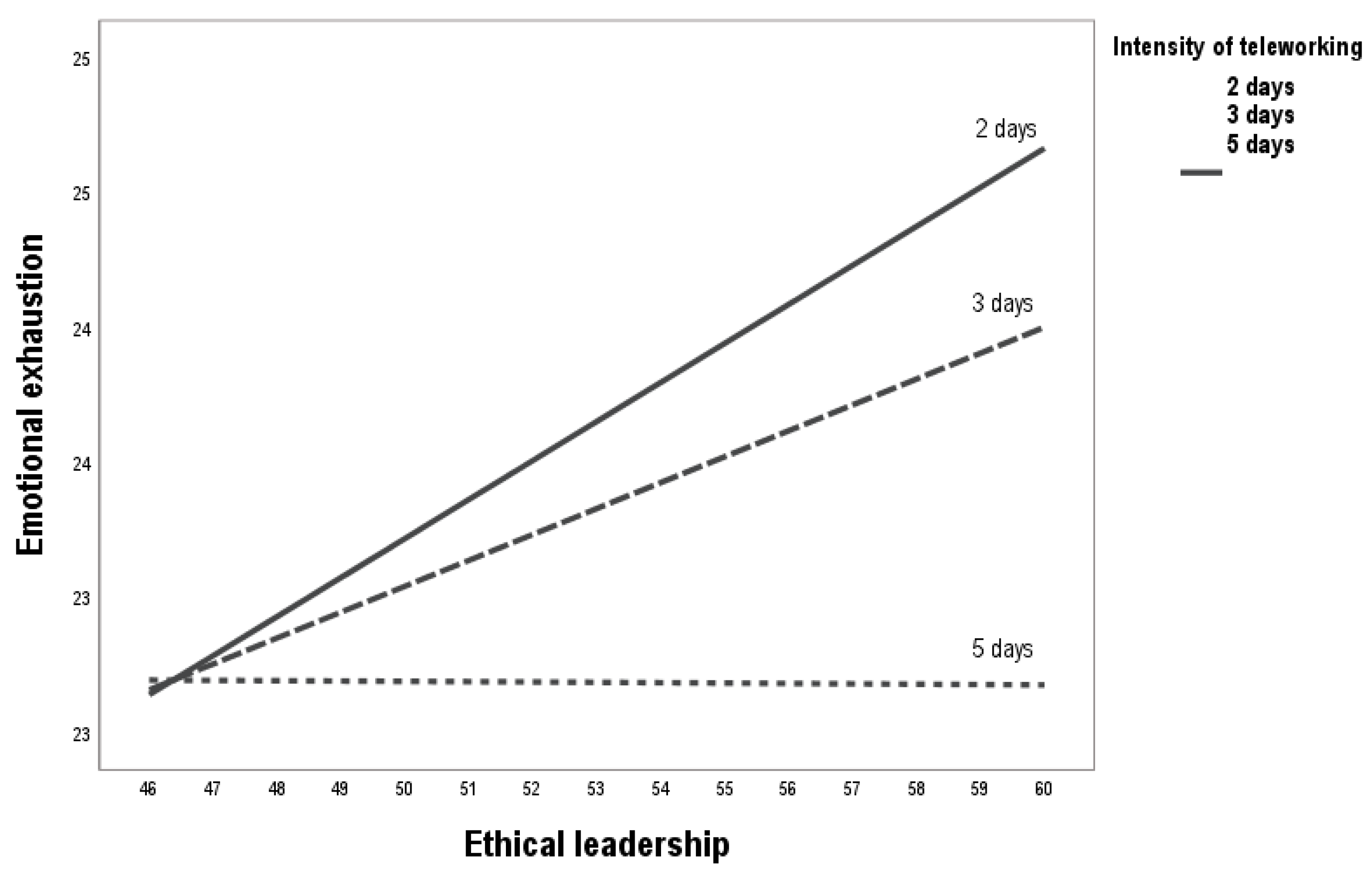

7.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

8. Discussion

9. Limitations and Future Research

10. Practical Implications

11. Conclusion

References

- Dust, S.B., Resick, C.J., Margolis, J.A., Mawritz, M.B., & Greenbaum, R.L. (2018). Ethical leadership and employee success: Examining the roles of psychological empowerment and emotional exhaustion. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 570–583. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., An, S., Lim, G.Y., & Sohn, Y.W. (2021). Ethical Leadership and Followers’ Emotional Exhaustion: Exploring the Roles of Three Types of Emotional Labor toward Leaders in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10862. [CrossRef]

- Okpozo, A.Z., Gong, T., Ennis, M.C., & Adenuga, B. (2017). Investigating the impact of ethical leadership on aspects of burnout. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(8), 1128–1143. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D., Witt, L.A., Waite, E., David, E.M., van Driel, M., McDonald, D.P., Callison, K.R., & Crepeau, L.J. (2015). Effects of ethical leadership on emotional exhaustion in high moral intensity situations. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(5), 732–748. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Sheng, X., He, Y., & Qian, X. (2020). Ethical Leadership as the Reliever of Frontline Service Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 976. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Corral-Marfil, J.A., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2024). Relationship between Personal Ethics and Burnout: The Unexpected Influence of Affective Commitment. Administrative Sciences, 14(6), 123. [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F., Baykal, E., & Abid, G. (2020). E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and Beyond: What We Know and Where Do We Go. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lazauskaitė-Zabielskė, J., Urbanavičiūtė, I., & Žiedelis, A. (2023). Pressed to overwork to exhaustion? The role of psychological detachment and exhaustion in the context of teleworking. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 44(3), 875–892. [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, A.G., Rapuano, V., & Varkulevičiūtė, K. (2021). Sensitive Men and Hardy Women: How Do Millennials, Xennials and Gen X Manage to Work from Home? Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(2), 106. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.R. (2009). E-ethical leadership for virtual project teams. International Journal of Project Management, 27(5), 456–463. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023a). Ethical leadership and creativity in employees with University education: The moderating effect of high intensity telework. Intangible Capital, 19(3), 393. [CrossRef]

- Doblinger, M., & Class, J. (2023). Does it fit? The relationships between personality, decision autonomy fit, work engagement, and emotional exhaustion in self-managing organizations. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 31(3), 420-442. [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T., Verhoogen, R., Sercu, M., Van den Broeck, A., Baillien, E., & Godderis, L. (2017). Not Extent of Telecommuting, But Job Characteristics as Proximal Predictors of Work-Related Well-Being. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 59(10), e180–e186. [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R.S., & Harrison, D.A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1524–1541. [CrossRef]

- Fonner, K.L., & Roloff, M.E. (2010). Why Teleworkers are More Satisfied with Their Jobs than are Office-Based Workers: When Less Contact is Beneficial. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 38(4), 336–361. [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R.S., Harrison, D.A., & Delaney-Klinger, K. (2015). Are Telecommuters Remotely Good Citizens? Unpacking Telecommuting’s Effects on Performance Via I-Deals and Job Resources. Personnel Psychology, 68(2), 353–393. [CrossRef]

- Junça Silva, A., Almeida, A., & Rebelo, C. (2022). The effect of telework on emotional exhaustion and task performance via work overload: the moderating role of self-leadership. International Journal of Manpower. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E., Treviño, L.K., & Harrison, D.A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H.D., Căpușneanu, S., Javed, T., Rakos, I.S., & Barbu, C.M. (2024). The Mediating Role of Attitudes towards Performing Well between Ethical Leadership, Technological Innovation, and Innovative Performance. Administrative Sciences, 14(4), 62. [CrossRef]

- Hamoudah, M.M., Othman, Z., Abdul Rahman, R., Mohd Noor, N.A., & Alamoudi, M. (2021). Ethical leadership, ethical climate and integrity violation: A comparative study in Saudi Arabia and Malaysia. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 43. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, M., Moreira, A., & Ramos, F. (2023). Occupational stress and turnover intentions in employees of the Portuguese tax and customs authority: Mediating effect of burnout and moderating effect of motivation. Administrative Sciences, 13(12), 251. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Han, X., Wang, W., Sun, G., & Cheng, Z. (2018). How social support influences university students’ academic achievement and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of self-esteem. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, L., Bruni, E., & Zampieri, R. (2019). The Role of Leadership in a Digitalized World: A Review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J., Kim, M.-J., & Kim, T.-H. (2021). “The Power of Ethical Leadership”: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Creativity, the Mediating Function of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2968. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. (2017). Finding solutions to the problem of burnout. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(2), 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Van Wart, M., Roman, A., Wang, X., & Liu, C. (2019). Operationalizing the definition of e-leadership: identifying the elements of e-leadership. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 85(1), 80–97. [CrossRef]

- Baer, M.D., Dhensa-Kahlon, R.K., Colquitt, J.A., Rodell, J.B., Outlaw, R., & Long, D.M. (2015). Uneasy Lies the Head that Bears the Trust: The Effects of Feeling Trusted on Emotional Exhaustion. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1637–1657. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.L. (2016). Ethical leadership and its impact on service innovative behavior: The role of LMX and job autonomy. Tourism Management, 57, 139–148. [CrossRef]

- Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D.N., & de Hoogh, A.H.B. (2013). Ethical leadership and followers’ helping and initiative: The role of demonstrated responsibility and job autonomy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 165–181. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Baranchenko, Y., An, F., Lin, Z., & Ma, J. (2020). The impact of ethical leadership on employee creative deviance: the mediating role of job autonomy. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(2), 219–232. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., & He, X. (2022). Role Stress, Job Autonomy, and Burnout: The Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction among Social Workers in China. Journal of Social Service Research, 48(3), 365–375. [CrossRef]

- Tourigny, L., Han, J., Baba, V.V., & Pan, P. (2019). Ethical Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: A Multilevel Study of Their Effects on Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(2), 427–440. [CrossRef]

- Anand, G., Chhajed, D., & Delfin, L. (2012). Job autonomy, trust in leadership, and continuous improvement: An empirical study in health care. Operations Management Research, 5(3–4), 70–80. [CrossRef]

- Borst, R.T. (2018). Comparing Work Engagement in People-Changing and People-Processing Service Providers: A Mediation Model With Red Tape, Autonomy, Dimensions of PSM, and Performance. Public Personnel Management, 47(3), 287–313. [CrossRef]

- Metselaar, S.A., den Dulk, L., & Vermeeren, B. (2023). Teleworking at Different Locations Outside the Office: Consequences for Perceived Performance and the Mediating Role of Autonomy and Work-Life Balance Satisfaction. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 43(3), 456–478. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Liu, W., Han, Y., & Zhang, P. (2016). Linking empowering leadership and change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 29(5), 732–750. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.M., & Scandura, T.A. (2014). Do Perceptions of Ethical Conduct Matter During Organizational Change? Ethical Leadership and Employee Involvement. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 185–196. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E., & Lilly, R.S. (1993). Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology, 21(2), 128–148.

- Park, H.I., Jacob, A.C., Wagner, S.H., & Baiden, M. (2014). Job Control and Burnout: A Meta-Analytic Test of the Conservation of Resources Model. Applied Psychology, 63(4), 607–642. [CrossRef]

- Farfán, J., Peña, M., Fernández-Salinero, S., & Topa, G. (2020). The Moderating Role of Extroversion and Neuroticism in the Relationship between Autonomy at Work, Burnout, and Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8166. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B., Liu, L., Ishikawa, H., & Park, S.-H. (2019). Relationships between social support, job autonomy, job satisfaction, and burnout among care workers in long-term care facilities in Hawaii. Educational Gerontology, 45(1), 57–68. [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C., Austin, S., Trépanier, S.-G., & Dussault, M. (2013). How do job characteristics contribute to burnout? Exploring the distinct mediating roles of perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 123–137. [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C., Lavigne, G.L., Vallerand, R.J., & Austin, S. (2014). Fired up with passion: Investigating how job autonomy and passion predict burnout at career start in teachers. Work & Stress, 28(3), 270–288. [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S.R., Sharma, D., & Golden, T.D. (2012). Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: a job demands and job resources model. New Technology, Work and Employment, 27(3), 193–207. [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T., Verhoogen, R., & Godderis, L. (2020). Teleworking and Employee Well-Being in Corona Times. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 62(12), e776–e777. [CrossRef]

- Belle, S.M., Burley, D.L., & Long, S.D. (2015). Where do I belong? High-intensity teleworkers’ experience of organizational belonging. Human Resource Development International, 18(1), 76–96. [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D., & Veiga, J.F. (2005). The Impact of Extent of Telecommuting on Job Satisfaction: Resolving Inconsistent Findings. Journal of Management, 31(2), 301–318. [CrossRef]

- Chambel, M.J., Castanheira, F., & Santos, A. (2022). Teleworking in times of COVID-19: the role of Family-Supportive supervisor behaviors in workers’ work-family management, exhaustion, and work engagement. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Moens, E., Lippens, L., Sterkens, P., Weytjens, J., & Baert, S. (2022). The COVID-19 crisis and telework: a research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes. The European Journal of Health Economics, 23(4), 729–753. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Tarrats-Pons, E., & Corral-Marfil, J.A. (2023a). Teleworking and emotional exhaustion. The curvilinear role of work intensity. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 12(2), 123-156. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Modroño, P. (2022). Working Conditions and Work Engagement by Gender and Digital Work Intensity. Information, 13(6), 277. [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P., Delaney-Klinger, K., & Hemingway, M.A. (2005). The Importance of Job Autonomy, Cognitive Ability, and Job-Related Skill for Predicting Role Breadth and Job Performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 399–406. [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D., Cho, E., & Meier, L.L. (2014). Work–Family Boundary Dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 99–121. [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D., Golden, T.D., & Shockley, K.M. (2015). How Effective Is Telecommuting? Assessing the Status of Our Scientific Findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(2), 40–68. [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A. (2010). Effects of Job Satisfaction and Conscientiousness on Extra-Role Behaviors. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(1), 119–130. [CrossRef]

- Ren, T., Fang, R., & Yang, Z. (2017). The impact of pay-for-performance perception and pay level satisfaction on employee work attitudes and extra-role behaviors. Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 8(2), 94–113. [CrossRef]

- Mo, S., & Shi, J. (2017). Linking Ethical Leadership to Employee Burnout, Workplace Deviance and Performance: Testing the Mediating Roles of Trust in Leader and Surface Acting. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(2), 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Schall, M.A. (2019). The Relationship Between Remote Work and Job Satisfaction [San Jose State University]. [CrossRef]

- Jing, L., Chen, R., Jing, L., Qiao, Y., Lou, J., Xu, J., Wang, J., Chen, W., & Sun, X. (2017). Development and enrolee satisfaction with basic medical insurance in China: A systematic review and stratified cluster sampling survey. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 32(3), 285–298. [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. (2013). Stratified cluster sampling. BMJ, 347(nov22 3), f7016–f7016. [CrossRef]

- Bonett, D.G., & Wright, T.A. (2015). Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Huang, N., Qiu, S., Yang, S., & Deng, R. (2021). Ethical Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Mediation of Trust and Psychological Well-Being. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, Volume 14, 655–664. [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. (1995). Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M., Andrade, J.R., Ratten, V., & Santos, E. (2023). Psychological empowerment for the future of work: Evidence from Portugal. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 42(5), 65–78. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B. , Leiter, M.P. , Maslach, C.Y., & Jackson, S.E. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey. En C. Maslach, S.E. Jackson y M.P. Leiter (Eds.) The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Test Manual (3rd ed.) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- De Beer, L.T., Schaufeli, W.B., & Bakker, A.B. (2022). Investigating the validity of the short form Burnout Assessment Tool: A job demands-resources approach. African Journal of Psychological Assessment, 4, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Virick, M., DaSilva, N., & Arrington, K. (2010). Moderators of the curvilinear relation between extent of telecommuting and job and life satisfaction: The role of performance outcome orientation and worker type. Human Relations, 63(1), 137–154. [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., & Podsakoff, N.P. (2012). Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. (1998). Software Review: Software Programs for Structural Equation Modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 16(4), 343–364. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P., Yi, Y., & Nassen, K.D. (1998). Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. Journal of Econometrics, 89(1–2), 393–421. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M., & Kenny, D.A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J., Long, Y., He, Q., & Liu, Y. (2020). Can Ethical Leadership Improve Employees’ Well-Being at Work? Another Side of Ethical Leadership Based on Organizational Citizenship Anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. (2014). Does Ethical Leadership Lead to Happy Workers? A Study on the Impact of Ethical Leadership, Subjective Well-Being, and Life Happiness in the Chinese Culture. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(3), 513–525. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1979). Self-referent mechanisms in social learning theory. American Psychologist, 34(5), 439–441. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1985). Model of Causality in Social Learning Theory. In Cognition and Psychotherapy (pp. 81–99). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G.V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-Efficacy Beliefs as Shapers of Children’s Aspirations and Career Trajectories. Child Development, 72(1), 187–206. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W., Treviño, L.K., & Zheng, X. (2016). Ethical Leaders and Their Followers: The Transmission of Moral Identity and Moral Attentiveness. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(1), 95–115. [CrossRef]

- Páez, I., & Salgado, E. (2016). When deeds speak, words are nothing: a study of ethical leadership in Colombia. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(4), 538–555. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023b). Curvilinear relationship between ethical leadership and creativity within the Colombian electricity sector. The mediating role of work autonomy, affective commitment, and intrinsic motivation. Revista iberoamericana de estudios de desarrollo= Iberoamerican journal of development studies, 12(1), 74-100. [CrossRef]

- Turgut, S., Michel, A., Rothenhöfer, L.M., & Sonntag, K. (2016). Dispositional resistance to change and emotional exhaustion: moderating effects at the work-unit level. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(5), 735–750. [CrossRef]

- Girardi, D., Dal Corso, L., Arcucci, E., Di Sipio, A., & Falco, A. (2022). Can perceived social support protect against emotional exhaustion in smart workers? a longitudinal study. 400–404. [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, M., Orlikowski, W.J., & Yates, J. (2013). The Autonomy Paradox: The Implications of Mobile Email Devices for Knowledge Professionals. Organization Science, 24(5), 1337–1357. [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P., & Molinaro, D. (2020). Negative (Workaholic) Emotions and Emotional Exhaustion: Might Job Autonomy Have Played a Strategic Role in Workers with Responsibility during the Covid-19 Crisis Lockdown? Behavioral Sciences, 10(12), 192. [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B., Paškvan, M., & Bunner, J. (2017). The Bright and Dark Sides of Job Autonomy. In Job Demands in a Changing World of Work (pp. 45–63). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., Schmitt, A., Jimmieson, N.L., & Rudolph, C.W. (2019). Dynamic effects of personal initiative on engagement and exhaustion: The role of mood, autonomy, and support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(1), 38–58. [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A.S., Heine, G., & Mahembe, B. (2014). The influence of ethical leadership on trust and work engagement: An exploratory study. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Suifan, T.S., Diab, H., Alhyari, S., & Sweis, R.J. (2020). Does ethical leadership reduce turnover intention? The mediating effects of psychological empowerment and organizational identification. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30(4), 410–428. [CrossRef]

- Schulze, J., Krumm, S., Eid, M., Müller, H., & Göritz, A.S. (2024). The relationship between telework and job characteristics: A latent change score analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Psychology, 73(1), 3–33. [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B., Paškvan, M., & Korunka, C. (2015). Development and validation of an instrument for assessing job demands arising from accelerated change: The intensification of job demands scale (IDS). European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 898–913. [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A.B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Daily self-management and employee work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(1), 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Parent-Lamarche, A. (2022). Teleworking, Work Engagement, and Intention to Quit during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Same Storm, Different Boats? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1267. [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D.M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.H.J., Ma, J., & Johnson, R.E. (2016). When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(6), 815–830. [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F., Gailliot, M., DeWall, C.N., & Oaten, M. (2006). Self-Regulation and Personality: How Interventions Increase Regulatory Success, and How Depletion Moderates the Effects of Traits on Behavior. Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1773–1802. [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A., Thomas, G., Martin, R., Guillaume, Y., & Marstand, A.F. (2019). Beyond relationship quality: The role of leader–member exchange importance in leader–follower dyads. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(4), 736–763. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y., Chien, C., & Shen, L.-F. (2023). Teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic: a leader-member exchange perspective. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 11(1), 68–84. [CrossRef]

- Varma, A., Jaiswal, A., Pereira, V., & Kumar, Y.L.N. (2022). Leader-member exchange in the age of remote work. Human Resource Development International, 25(2), 219–230. [CrossRef]

- Schermuly, C.C., & Meyer, B. (2016). Good relationships at work: The effects of Leader–Member Exchange and Team–Member Exchange on psychological empowerment, emotional exhaustion, and depression. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(5), 673–691. [CrossRef]

- Adams, N., Little, T.D., & Ryan, R.M. (2017). Self-Determination Theory. In Development of Self-Determination Through the Life-Course (pp. 47–54). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (2012). Self-Determination Theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Volume 1 (pp. 416–437). SAGE Publications Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E.L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [CrossRef]

- Giebe, C., & Rigotti, T. (2022). Tenets of self-determination theory as a mechanism behind challenge demands: a within-person study. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 37(5), 480–497. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C., Tarrats-Pons, E., & Corral-Marfil, J.A. (2023b). Effects of Intensity of Teleworking and Creative Demands on the Cynicism Dimension of Job Burnout. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Stouten, J., van Dijke, M., Mayer, D.M., De Cremer, D., & Euwema, M.C. (2013). Can a leader be seen as too ethical? The curvilinear effects of ethical leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(5), 680–695. [CrossRef]

- Qi, H., Jingtao, F., Wenhao, W., & Pervaiz, S. (2023). You are “insisting”, or you want to “withdraw”? Research on the negative effect of ethical leadership on leaders themselves. Current Psychology, 42(30), 25968–25984. [CrossRef]

- Gheni, A.Y., Jusoh, Y.Y., Jabar, M.A., Ali, N.M., Abdullah, R. Hj., Abdullah, S., & Khalefa, M.S. (2015). The virtual teams: E-leaders challenges. 2015 IEEE Conference on E-Learning, e-Management and e-Services (IC3e), 38–42. [CrossRef]

- Roman, A.V., Van Wart, M., Wang, X., Liu, C., Kim, S., & McCarthy, A. (2019). Defining E-leadership as Competence in ICT-Mediated Communications: An Exploratory Assessment. Public Administration Review, 79(6), 853–866. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J., De las Heras-Rosas, C., Rodríguez-Fernández, M., & Ciruela-Lorenzo, A.M. (2022). Teleworking: The Link between Worker, Family and Company. Systems, 10(5), 134. [CrossRef]

- Thulin, E., Vilhelmson, B., & Johansson, M. (2019). New Telework, Time Pressure, and Time Use Control in Everyday Life. Sustainability, 11(11), 3067. [CrossRef]

- Vayre, É., Morin-Messabel, C., Cros, F., Maillot, A.-S., & Odin, N. (2022). Benefits and Risks of Teleworking from Home: The Teleworkers’ Point of View. Information, 13(11), 545. [CrossRef]

- Wibawa, W.M.S., & Takahashi, Y. (2021). The effect of ethical leadership on work engagement and workaholism: examining self-efficacy as a moderator. Administrative Sciences, 11(2), 50. [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23–43. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A., Patmos, A., & Pitts, M.J. (2018). Communication and Teleworking: A Study of Communication Channel Satisfaction, Personality, and Job Satisfaction for Teleworking Employees. International Journal of Business Communication, 55(1), 44–68. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., & Eyoun, K. (2021). Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102850. [CrossRef]

- Kao, K.-Y., Hsu, H.-H., Lee, H.-T., Cheng, Y.-C., Dax, I., & Hsieh, M.-W. (2022). Career Mentoring and Job Content Plateaus: The Roles of Perceived Organizational Support and Emotional Exhaustion. Journal of Career Development, 49(2), 457–470. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, L., & Han, X. (2018). Just the Right Amount of Ethics Inspires Creativity: A Cross-Level Investigation of Ethical Leadership, Intrinsic Motivation, and Employee Creativity. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(3), 645–658. [CrossRef]

- Kranabetter, C., & Niessen, C. (2017). Managers as role models for health: Moderators of the relationship of transformational leadership with employee exhaustion and cynicism. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(4), 492–502. [CrossRef]

| Constructs | N | M | SD | G | EL | TI | WA | EE |

| Gender | 1 | 0.32 | 0.45 | x | ||||

| Ethical Leadership (EL) | 10 | 51.60 | 8.22 | 0.04 | (0.80) | |||

| Teleworking Intensity (TI) | 1 | 3.90 | 1.99 | 0.06 | 0.14** | (0.72) | ||

| Work Autonomy (WA) | 3 | 14.25 | 2.52 | -0.03 | 0.18** | -0.11* | (0.84) | |

| Emotional Exhaustion (EE) | 5 | 23.11 | 5.50 | 0.05 | 0.26** | -0.12** | 0.20** | (0.76) |

| Predictors | Model 1 (EE) | Model 2 (WA) | Model 3 (EE) | ||||||

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| EL | 0.35** | 0.03 | 5.97** | 0.17** | 0.01 | 6.87** | 0.16** | 0.02 | 4.89** |

| WA | 0.59** | 0.05 | 8.28** | ||||||

| R² | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| F | 12.83** | 14.96** | 22.50*** | ||||||

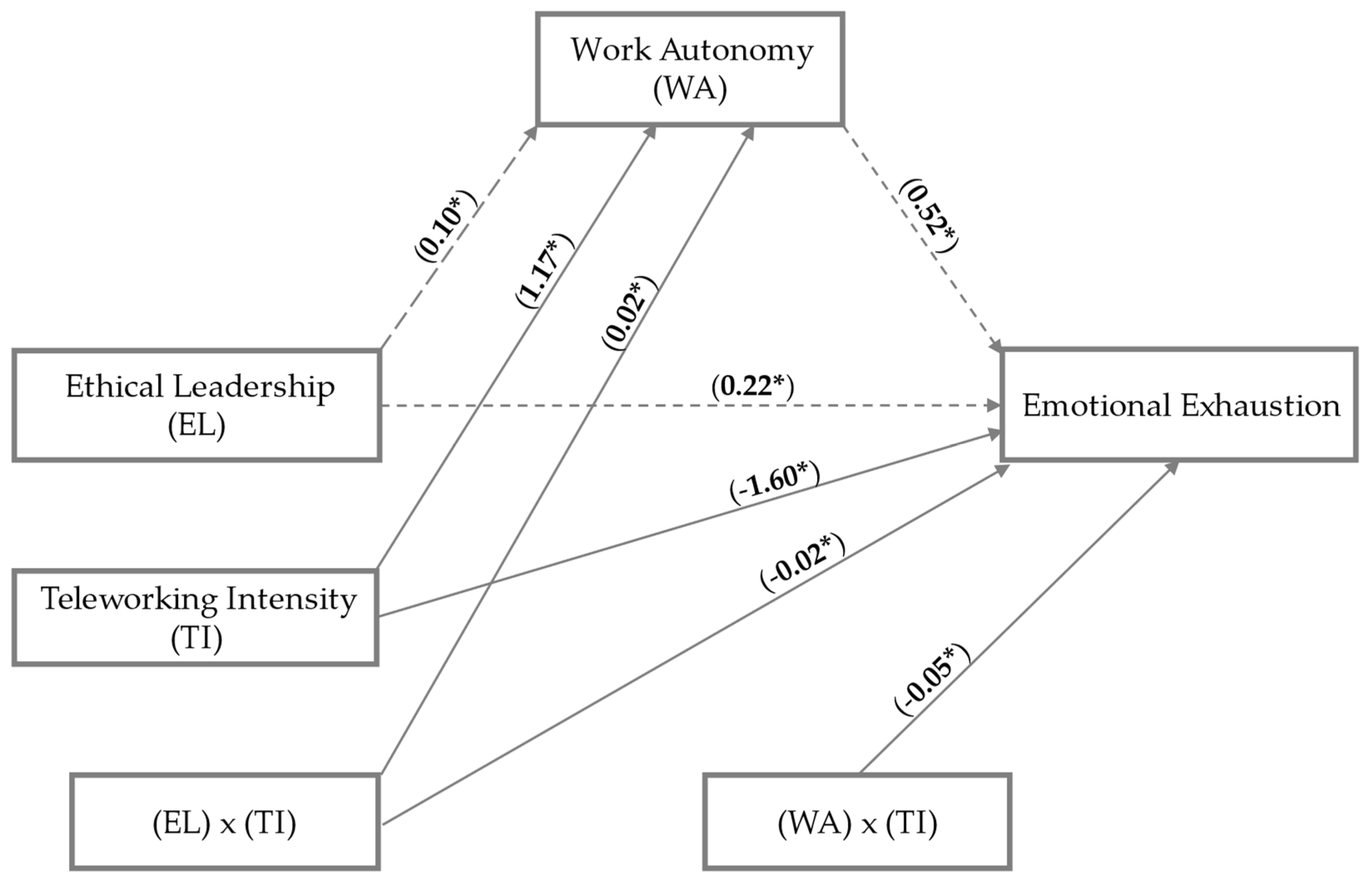

| Predictors | Model 1 (EE) | Model 2 (WA) | Model 3 (EE) | ||||||

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

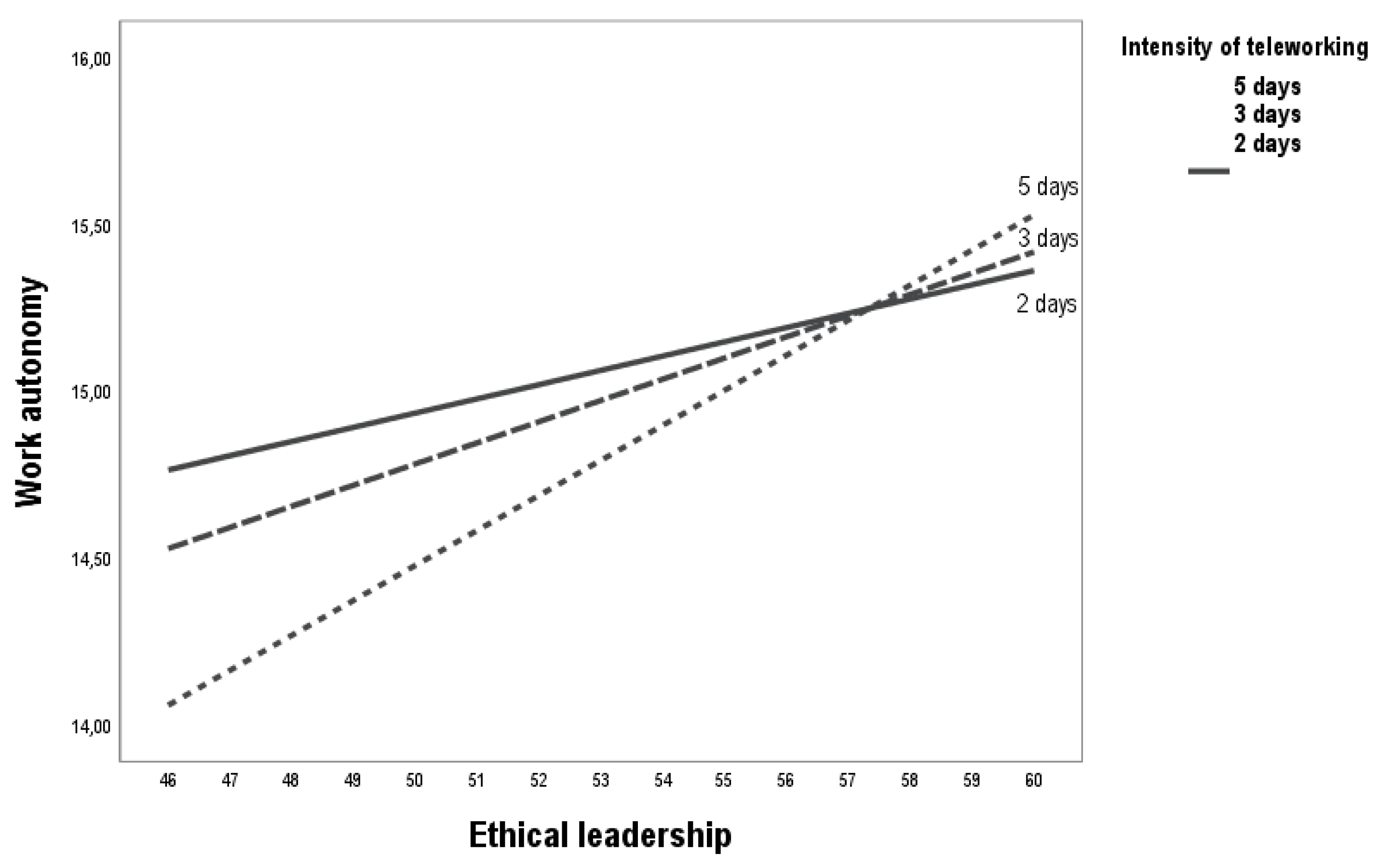

| EL | 0.22** | 0.07 | 3.26** | 0.10 | 0.03 | 2.03** | |||

| TI | -1.60** | 1.46 | -2.22** | 1.17** | 0.57 | 2.09** | |||

| EL(x) TI | -0.02** | 0.02 | -3.08** | 0.02** | 0.01 | 2.90** | |||

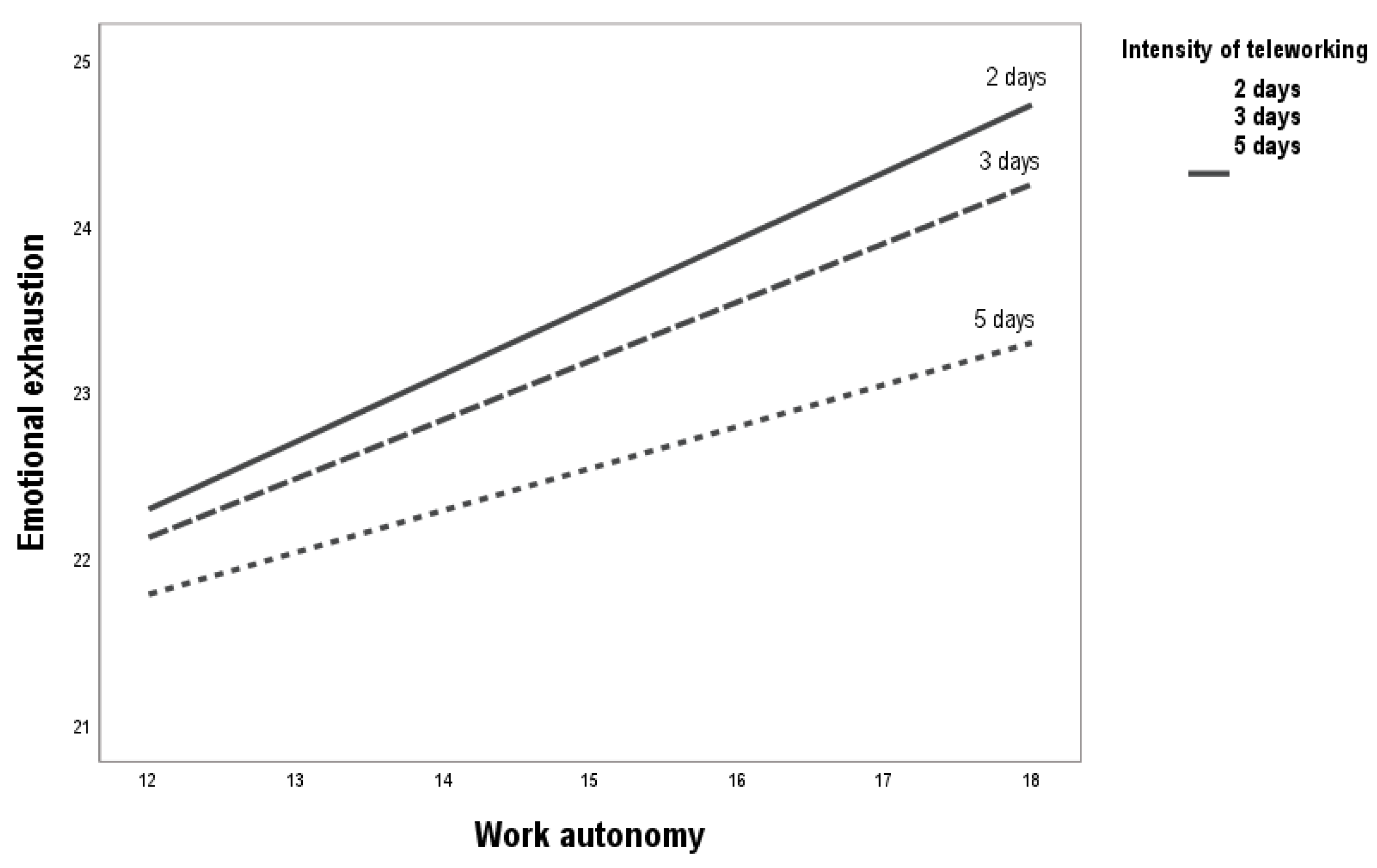

| WA | 0.52** | 0.26 | 2.89** | ||||||

| WA (x) TI | -0.05** | 0.07 | -3.24** | ||||||

| R² | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| F | 9.93** | 6.26** | 10.50** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).