Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Resources and Microstructures of Starches

2.1. Resources of Starches

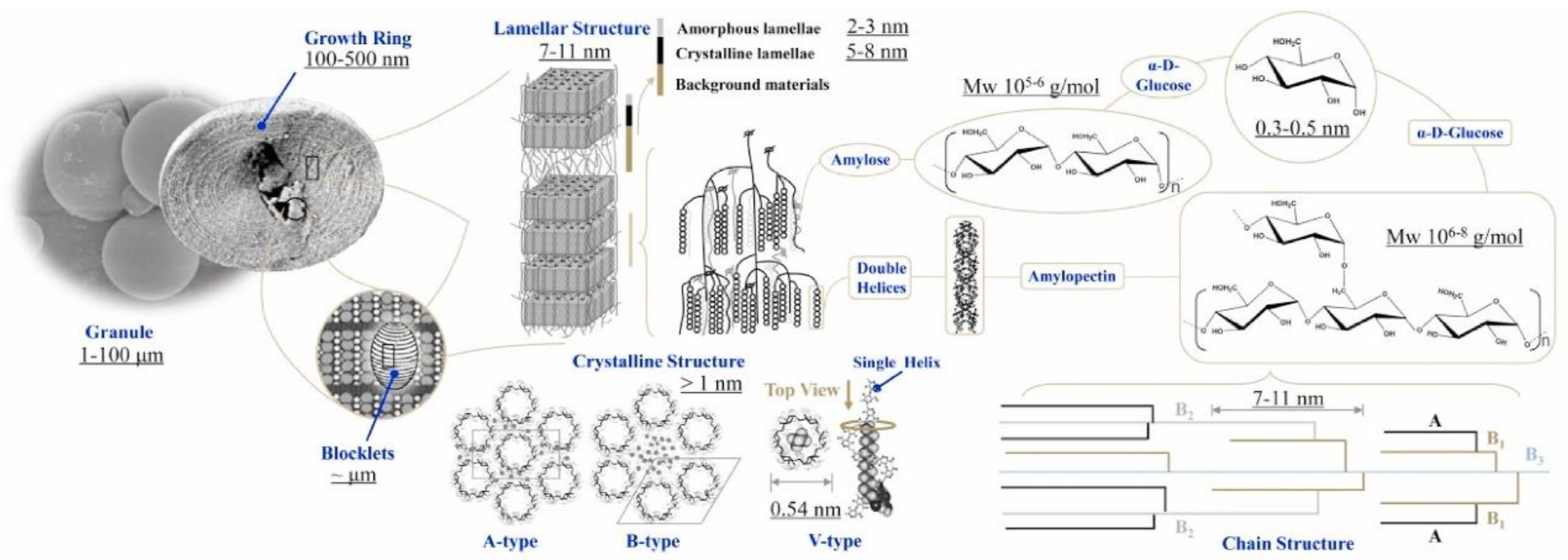

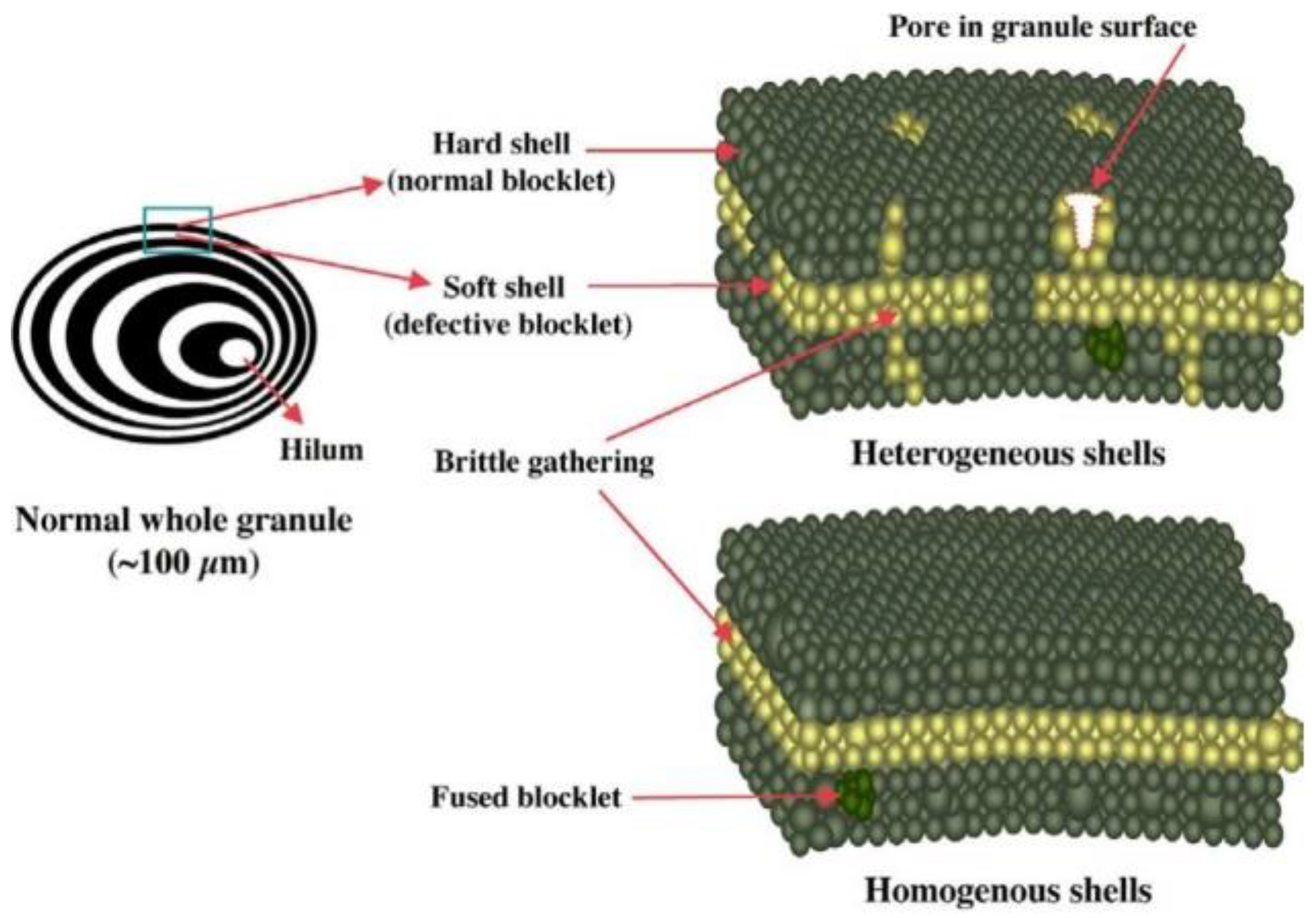

2.2. The Multi-Scale Structure of Starch

3. Phase Transitions of Starch During Thermal Processing

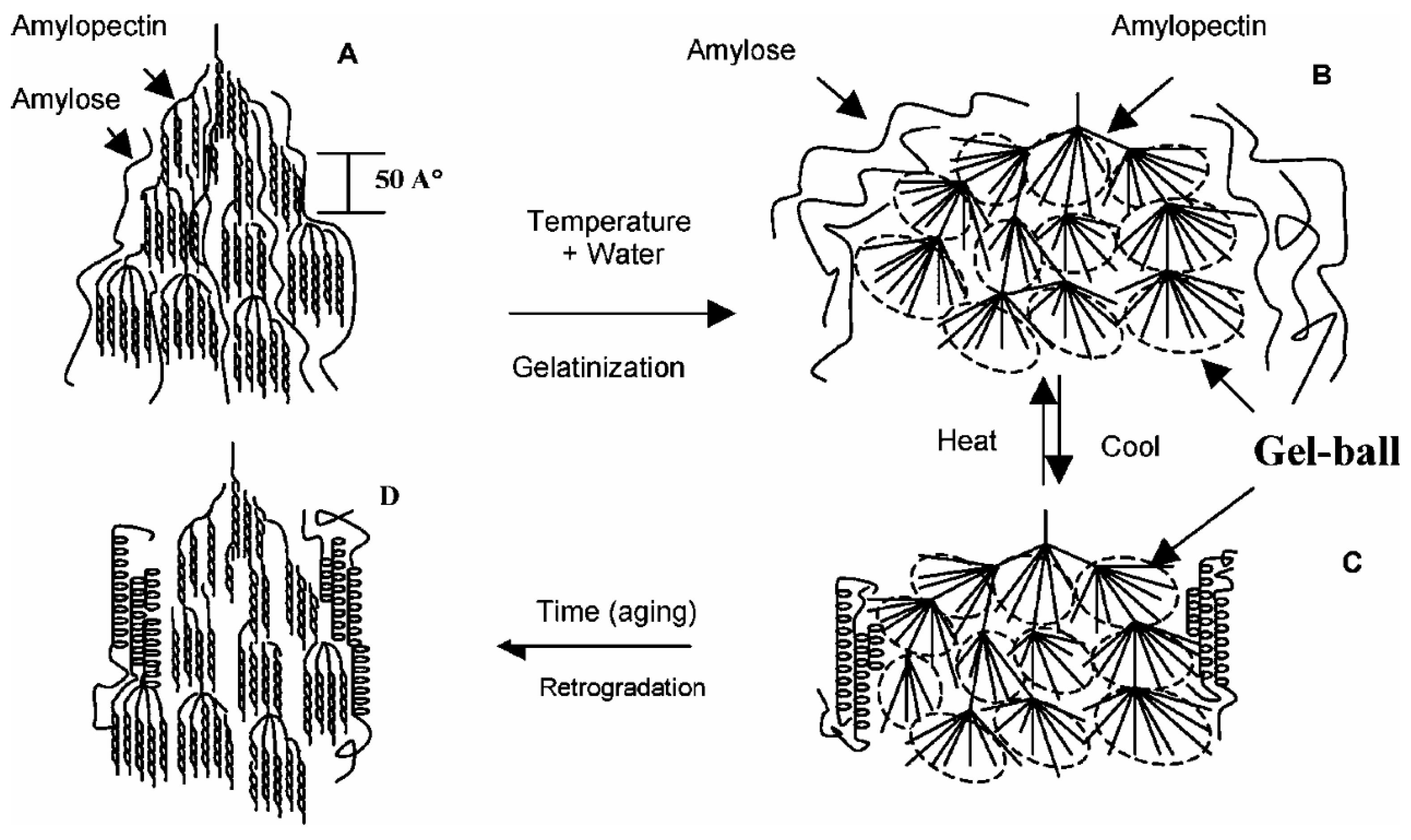

3.1. Starch Gelatinization

3.2. Starch Retrogradation

3.3. Phase Transition Under Shearless and Shear Strength Conditions

4. Improving Toughness by Plasticizers

4.1. Waters

4.2. Polyols and Saccharides

4.3. Other Polar Substances

4.4. Novel Plasticizers

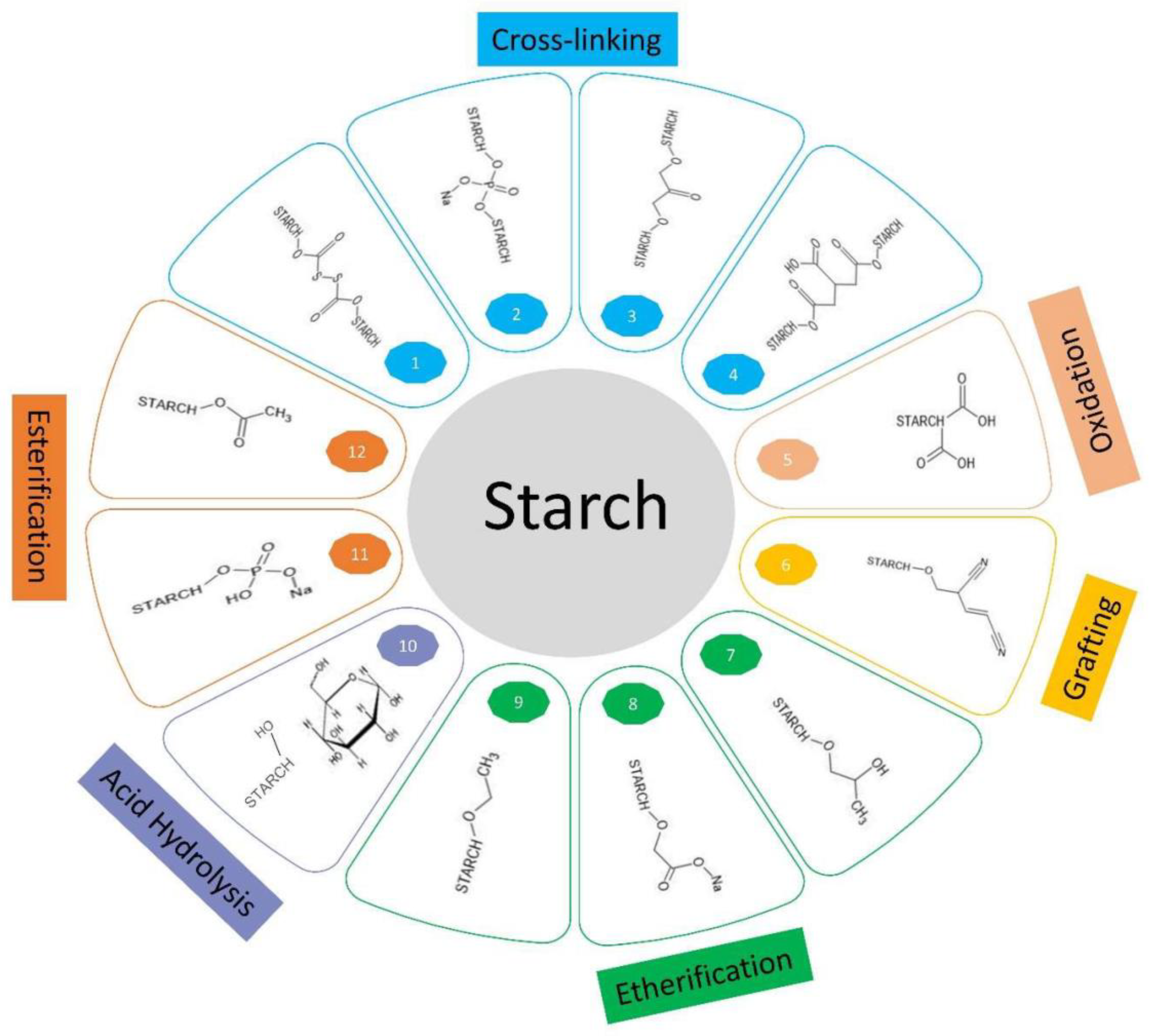

5. Chemical Modifications

5.1. Esterification

5.2. Etherification

5.3. Oxidization and Acid Hydrolysis

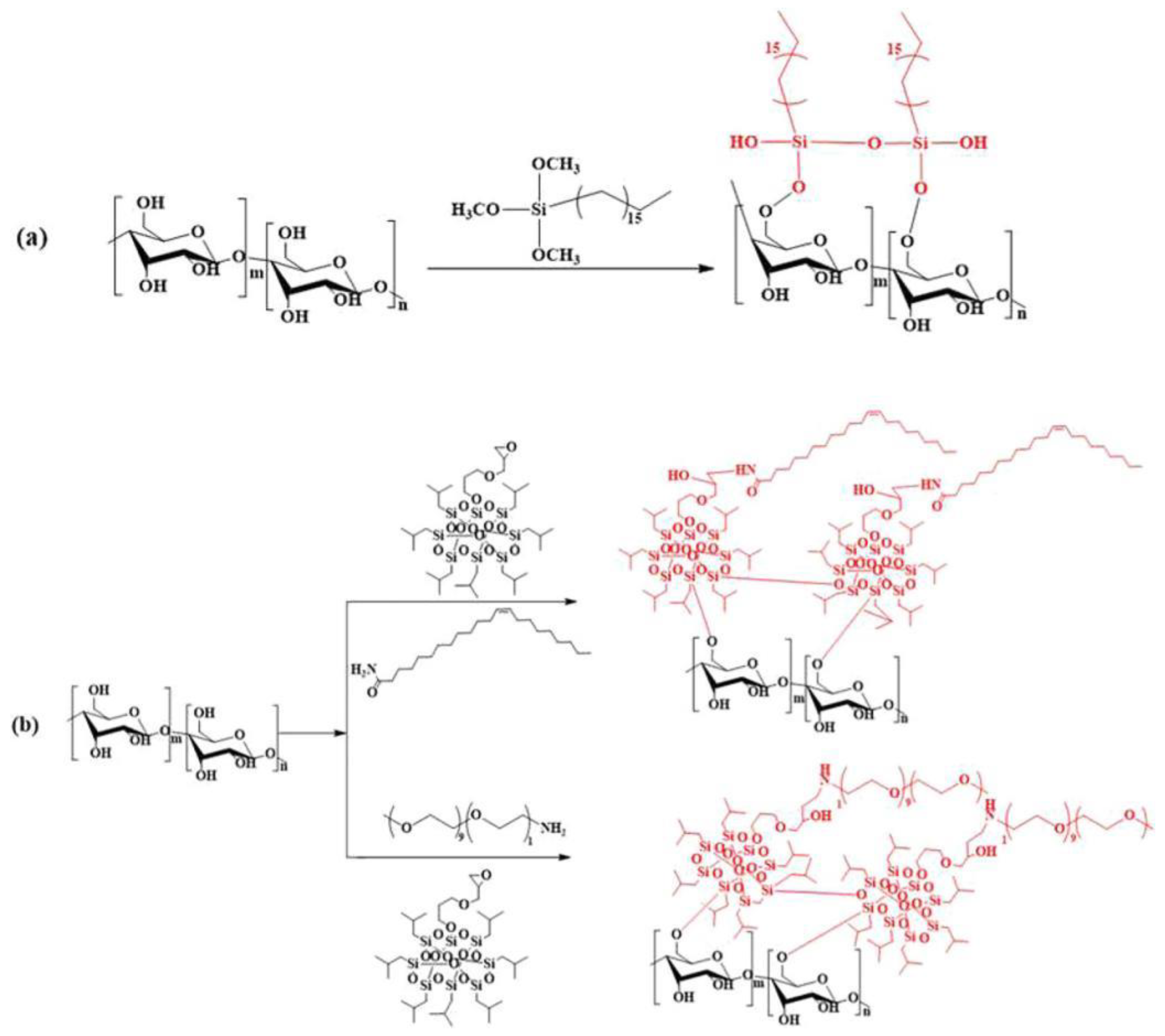

5.4. Grafting

5.5. Other Modification Methods

6. Composite with Other Hydrophilic Polymers

6.1. Starch/Cellulose Composite

6.2. Starch/ Hydrophilic Polymer Composites

7. Coating

Summary

- Microstructures of starches have been extensively investigated in multi-scales. Generally, there are two major chemical structures: linear amylose and branch amylopectin. Amylose chains showed higher flexibility and lower crystallinity, which results in better toughness after gelatinization and modifications. However, higher amylose starches still can’t meet the toughness requirement as packaging film.

- The well-accepted concept of gelatinization for starches is to destroy the crystalline strictures in the starch granules. Without gelatinization starches cannot be thermally processed using traditional facilities processing plastics, such as extrusion, film blowing etc. However, the gelatinized starch will recrystallize or retrogradate, which results brittleness of the starch materials.

- Plasticizing is one of the most popular methods to improve the toughness through internal lubrication. The ideal plasticizer should meet four primary necessities: efficiency, compatibility, less volatility, and performance. Since starch contains many hydroxyl groups, all the plasticizers must contain the same group. By decreasing the inner hydrogen bonding between chains of the starch, plasticizers can increase the flexibility and toughness of starch-based materials. Water is the most popular plasticizer for starches but the properties of starch-based products that are only plasticized by water are unstable, as water is a highly volatile substance with a low boiling point. To replace water as a plasticizer, various alternatives such as polyols, saccharides, and other polar substances like urea have been evaluated and developed. However, they showed lower efficacy under lower humidity conditions.

- Chemical modification is another popular and efficient way to improve performance of starches, including increasing toughness. However, in order to remove the residues of the chemicals used for modifications and higher yield, the modification DC is normally lower reacted in the aqueous solution. The highly efficient extrusion could produce modified starches with higher DC but the changelings is to remove the residues of the chemicals used for modifications. The various modified starch films are still brittle under very lower humidity.

- Blending and compositing with other polymers can improve the mechanical properties, including toughness of starch-based materials. In order to keep the advantages of fully biodegradable even edible, all the additivities must meet these requirements. Recently starches reinforced by various nano-cellulose have showed greatly promise. The weakness of instability under lower humidity conditions still in there plus higher cost.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adewale, P.; Yancheshmeh, M.S.; Lam, E. Starch modification for non-food, industrial applications: Market intelligence and critical review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 291, 119590. [CrossRef]

- Caldonazo, A.; Almeida, S.L.; Bonetti, A.F.; Lazo, R.E.L.; Mengarda, M.; Murakami, F.S. Pharmaceutical applications of starch nanoparticles: A scoping review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 181, 697-704. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yuan, T.Z.; Chigwedere, C.M.; Ai, Y. A current review of structure, functional properties, and industrial applications of pulse starches for value-added utilization. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2021, 20, 3061-3092. [CrossRef]

- Lauer, M.K.; Smith, R.C. Recent advances in starch-based films toward food packaging applications: Physicochemical, mechanical, and functional properties. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19, 3031-3083. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, P.; Zou, W.; Yu, L.; Xie, F.; Pu, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, L. Extrusion processing and characterization of edible starch films with different amylose contents. Journal of Food Engineering 2011, 106, 95-101. [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, I.; Chakraborty, I.; Baruah, V.J.; Sarmah, B.; Mahato, K.K.; Mazumder, N. Structure and Morphological Properties of Starch Macromolecule Using Biophysical Techniques. Starch - Stärke 2020, 73. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pacheco, E.; Canto-Pinto, J.C.; Moo-Huchin, V.M.; Estrada-Mota, I.A.; Estrada-León, R.J.; Chel-Guerrero, L. Thermoplastic Starch (TPS)-Cellulosic Fibers Composites: Mechanical Properties and Water Vapor Barrier: A Review. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Nawab, A.; Alam, F.; Haq, M.A.; Hasnain, A. Biodegradable film from mango kernel starch: Effect of plasticizers on physical, barrier, and mechanical properties. Starch - Stärke 2016, 68, 919-928. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, P. Botanical Sources of Starch. In Starch Structure, Functionality and Application in Foods, Wang, S., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 9-27.

- Chen, P.; Yu, L.; Simon, G.P.; Liu, X.; Dean, K.; Chen, L. Internal structures and phase-transitions of starch granules during gelatinization. Carbohydrate Polymers 2011, 83, 1975-1983. [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wei, C. Progress in C-type starches from different plant sources. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 73, 162-175. [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Li, X.; Huang, S.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Miao, S. Basic principles in starch multi-scale structuration to mitigate digestibility: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 109, 154-168. [CrossRef]

- Bertoft, E. Understanding Starch Structure: Recent Progress. Agronomy 2017, 7, 56. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Copeland, L.; Wang, S. Methods for characterizing the structure of starch in relation to its applications: a comprehensive review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2021, 63, 4799-4816. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, L.; Corrigan, P.A.; Yu, L.; Liu, Z. Application of Atomic Force Microscopy on Studying Micro- and Nano-Structures of Starch. International Journal of Food Engineering 2008, 4. [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Liu, H.; Chen, P.; Xue, T.; Chen, L.; Yu, L.; Corrigan, P. Starch Gelatinization under Shearless and Shear Conditions. International Journal of Food Engineering 2006, 2. [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Zhang, S. The green manufacturing of thermoplastic starch for low-carbon and sustainable energy applications: a review on its progress. Green Chemistry 2024, 26, 1194-1222. [CrossRef]

- Sangwongchai, W.; Tananuwong, K.; Krusong, K.; Natee, S.; Thitisaksakul, M. Starch Chemical Composition and Molecular Structure in Relation to Physicochemical Characteristics and Resistant Starch Content of Four Thai Commercial Rice Cultivars Differing in Pasting Properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 574. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, A.; Yu, W.; Hu, Y.; Li, E.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q. Parameterizing starch chain-length distributions for structure-property relations. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 241, 116390. [CrossRef]

- Gebre, B.A.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Sui, Z.; Corke, H. Impact of starch chain length distributions on physicochemical properties and digestibility of starches. Food Chemistry 2024, 435, 137641. [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Channab, B.-e.; El Idrissi, A.; Zahouily, M.; Motamedi, E. A comprehensive review on starch: Structure, modification, and applications in slow/controlled-release fertilizers in agriculture. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 322, 121326. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Luan, H. Multiscale Structures of Starch Granules. In Starch Structure, Functionality and Application in Foods, Wang, S., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 41-55.

- Tang, H.; Mitsunaga, T.; Kawamura, Y. Molecular arrangement in blocklets and starch granule architecture. Carbohydrate Polymers 2006, 63, 555-560. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Sun, Z.; Saleh, A.S.M.; Zhao, K.; Ge, X.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, L.; Yu, X.; Li, W. Understanding the granule, growth ring, blocklets, crystalline and molecular structure of normal and waxy wheat A- and B- starch granules. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 121, 107034. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ziegler, G.R.; Kong, L. Polymorphic transitions of V-type amylose upon hydration and dehydration. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 125, 107372. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, M.E.; Hernandez-Landaverde, M.A.; Delgado, J.M.; Ramirez-Gutierrez, C.F.; Ramirez-Cardona, M.; Millan-Malo, B.M.; Londoño-Restrepo, S.M. Crystalline structures of the main components of starch. Current Opinion in Food Science 2021, 37, 107-111. [CrossRef]

- Lourdin, D.; Putaux, J.-L.; Potocki-Véronèse, G.; Chevigny, C.; Rolland-Sabaté, A.; Buléon, A. Crystalline Structure in Starch. 2015, 61-90. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Duan, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, S.; Ge, X.; Shen, H.; Li, W.; Yan, W. Effect of dry heat treatment on multi-structure, physicochemical properties, and in vitro digestibility of potato starch with controlled surface-removed levels. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 134, 108062. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, E.; Khachatryan, G.; Wisła-Świder, A. Structural changes of different starches illuminated with linearly polarised visible light. Food Chemistry 2021, 344, 128693. [CrossRef]

- Hoover, R. Composition, molecular structure, and physicochemical properties of tuber and root starches: a review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2001, 45, 253-267.

- Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Simon, G.; Dean, K.; Chen, L. Effects of annealing on gelatinization and microstructures of corn starches with different amylose/amylopectin ratios. Carbohydrate Polymers 2009, 77, 662-669. [CrossRef]

- Donmez, D.; Pinho, L.; Patel, B.; Desam, P.; Campanella, O.H. Characterization of starch–water interactions and their effects on two key functional properties: starch gelatinization and retrogradation. Current Opinion in Food Science 2021, 39, 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; McClements, D.J.; Luo, S.; Liu, C.; Ye, J. Recent advances in the impact of gelatinization degree on starch: Structure, properties and applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 340, 122273. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Ai, Y. Gelation mechanisms of granular and non-granular starches with variations in molecular structures. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 129, 107658. [CrossRef]

- Apriyanto, A.; Compart, J.; Fettke, J. A review of starch, a unique biopolymer – Structure, metabolism and in planta modifications. Plant Science 2022, 318, 111223. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Recent progress in understanding starch gelatinization - An important property determining food quality. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 293, 119735. [CrossRef]

- Palabiyik, İ.; Toker, O.S.; Karaman, S.; Yildiz, Ö. A modeling approach in the interpretation of starch pasting properties. Journal of Cereal Science 2017, 74, 272-278. [CrossRef]

- Vamadevan, V.; Bertoft, E. Observations on the impact of amylopectin and amylose structure on the swelling of starch granules. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 103, 105663. [CrossRef]

- Yashini, M.; Khushbu, S.; Madhurima, N.; Sunil, C.K.; Mahendran, R.; Venkatachalapathy, N. Thermal properties of different types of starch: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 64, 4373-4396. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Xie, F.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Rheological properties and phase transition of cornstarches with different amylose/amylopectin ratios under shear stress. Starch-Starke 2010, 62, 667-675. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, F.; Chen, L.; Yu, L.; Dean, K.; Bateman, S. Thermal Behaviour of High Amylose Cornstarch Studied by DSC. International Journal of Food Engineering 2005, 1. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gong, B. Insights into chain-length distributions of amylopectin and amylose molecules on the gelatinization property of rice starches. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 155, 721-729. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Corke, H.; Bertoft, E. Amylopectin internal molecular structure in relation to physical properties of sweetpotato starch. Carbohydrate Polymers 2011, 84, 907-918. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ouyang, J. Influence of amylose on the pasting and gel texture properties of chestnut starch during thermal processing. Food Chemistry 2019, 294, 378-383. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gong, B. Relations between rice starch fine molecular and lamellar/crystalline structures. Food Chemistry 2021, 353, 129467. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xing, F.; Hou, H.; Wang, W.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, C. Exploring the influence mechanism of water grinding on the gel properties of corn starch based on changes in its structure and properties. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2023, 103, 4858-4866. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Copeland, L. Molecular disassembly of starch granules during gelatinization and its effect on starch digestibility: a review. Food & Function 2013, 4, 1564-1580. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, H.; Yang, H.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R. Effects of salts on the gelatinization and retrogradation properties of maize starch and waxy maize starch. Food Chemistry 2017, 214, 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Jane, J.-L. Mechanism of Starch Gelatinization in Neutral Salt Solutions. Starch - Stärke 1993, 45, 161-166. [CrossRef]

- Nicol, T.W.J.; Isobe, N.; Clark, J.H.; Matubayasi, N.; Shimizu, S. The mechanism of salt effects on starch gelatinization from a statistical thermodynamic perspective. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 87, 593-601. [CrossRef]

- Haixia, Z.; Zhiguang, C.; Junrong, H.; Huayin, P. Exploration of the process and mechanism of magnesium chloride induced starch gelatinization. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 205, 118-127. [CrossRef]

- Maaurf, A.G.; Che Man, Y.B.; Asbi, B.A.; Junainah, A.H.; Kennedy, J.F. Gelatinisation of sago starch in the presence of sucrose and sodium chloride as assessed by differential scanning calorimetry. Carbohydrate Polymers 2001, 45, 335-345. [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Tao, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, R.; Yan, X.; Jiang, F.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X. Impacts of Konjac Glucomannan on the Pasting, Texture, and Rheological Properties of Potato Starch with Different Heat–Moisture Treatments. Starch - Stärke 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chao, C.; Cai, J.; Niu, B.; Copeland, L.; Wang, S. Starch–lipid and starch–lipid–protein complexes: A comprehensive review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19, 1056-1079. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qin, L.; Chen, T.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, W.; Ji, X.; Xie, J. Modification of starch by polysaccharides in pasting, rheology, texture and in vitro digestion: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 207, 81-89. [CrossRef]

- Putseys, J.A.; Lamberts, L.; Delcour, J.A. Amylose-inclusion complexes: Formation, identity and physico-chemical properties. Journal of Cereal Science 2010, 51, 238-247. [CrossRef]

- Oyeyinka, S.A.; Singh, S.; Venter, S.L.; Amonsou, E.O. Effect of lipid types on complexation and some physicochemical properties of bambara groundnut starch. Starch - Stärke 2017, 69, 1600158. [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.; Liang, S.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S. Effects of Starch-Lipid Complexes on Quality and Starch Digestibility of Wheat Noodles. Starch - Stärke 2024. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.; Mondal, D.; Thomas, B.; Singh, A.; Praveen, S. Starch-lipid interaction alters the molecular structure and ultimate starch bioavailability: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 182, 626-638. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Chao, C.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. Effects of different sources of proteins on the formation of starch-lipid-protein complexes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 126853. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xu, S.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Ye, J.; Liu, C. Effect of Homogenization Modified Rice Protein on the Pasting Properties of Rice Starch. Foods 2022, 11, 1601. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q.; Ye, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.; Bao, J.; Corke, H.; Sui, Z. Starch granule-associated proteins affect the physicochemical properties of rice starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 101, 105504. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lin, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, G. Effects of endogenous proteins and lipids on structural, thermal, rheological, and pasting properties and digestibility of adlay seed (Coix lacryma-jobi L.) starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 111, 106254. [CrossRef]

- Woodbury, T.J.; Mauer, L.J. Oligosaccharide, sucrose, and allulose effects on the pasting and retrogradation behaviors of wheat starch. Food Research International 2023, 171, 113002. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Kim, G.; Ryu, K.; Park, J.; Lee, S. Effect of different sweeteners on the thermal, rheological, and water mobility properties of soft wheat flour and their application to cookies as an alternative to sugar. Food Chemistry 2024, 432, 137193. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Luo, Y.; Barba, F.J.; Wu, Y.; Ding, W.; Xiao, S.; Lyu, Q.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y. Effect of β-cyclodextrins on the physical properties and anti-staling mechanisms of corn starch gels during storage. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 284, 119187. [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Yang, J. The effects of sugar alcohols on rheological properties, functionalities, and texture in baked products – A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 111, 670-679. [CrossRef]

- Allan, M.C.; Rajwa, B.; Mauer, L.J. Effects of sugars and sugar alcohols on the gelatinization temperature of wheat starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2018, 84, 593-607. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Jia, Z.; Hou, L.; Xiao, S.; Yang, H.; Ding, W.; Wei, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X. Study on physicochemical properties and anti-aging mechanism of wheat starch by anionic polysaccharides. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 127431. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Rong, L.; Shen, M.; Liu, W.; Xiao, W.; Luo, Y.; Xie, J. Interaction between rice starch and Mesona chinensis Benth polysaccharide gels: Pasting and gelling properties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 240, 116316. [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Nawab, A.; Lutfi, Z.; Haider, S.Z. Effect of Non-Starch Polysaccharides on the Pasting, Gel, and Gelation Properties of Taro (Colocasia esculenta) Starch. Starch - Stärke 2020, 73. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, L.; Hu, C.; Huang, C.; Chen, Z.; Huang, L. Unveiling the retrogradation mechanism of a novel high amylose content starch-Pouteria campechiana seed. Food Chemistry: X 2023, 18, 100637. [CrossRef]

- Matignon, A.; Tecante, A. Starch retrogradation: From starch components to cereal products. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 68, 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Tong, Z.; Chen, L. Retrogradation of waxy cornstarch studied by DSC. Starch-Starke 2010, 62, 524-529. [CrossRef]

- Zhiguang, C.; Junrong, H.; Huayin, P.; Keipper, W. The Effects of Temperature on Starch Molecular Conformation and Hydrogen Bonding. Starch - Stärke 2022, 74, 2100288. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, F.; Jiao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Li, Q. Insight to starch retrogradation through fine structure models: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 273, 132765. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Dhital, S.; Shan, C.-S.; Zhang, M.-N.; Chen, Z.-G. Ordered structural changes of retrograded starch gel over long-term storage in wet starch noodles. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 270, 118367. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Bertoft, E. The molecular structures of starch components and their contribution to the architecture of starch granules: A comprehensive review. Starch - Stärke 2010, 62, 389-420. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, X.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y. Long-term retrogradation behavior of lotus seed starch-chlorogenic acid mixtures after microwave treatment. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 121, 106994. [CrossRef]

- Dobosz, A.; Sikora, M.; Krystyjan, M.; Tomasik, P.; Lach, R.; Borczak, B.; Berski, W.; Lukasiewicz, M. Short- and long-term retrogradation of potato starches with varying amylose content. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2019, 99, 2393-2403. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; Sui, Z.; Corke, H. Gel texture and rheological properties of normal amylose and waxy potato starch blends with rice starches differing in amylose content. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2021, 56, 1946-1958. [CrossRef]

- Holló, J.; Szejtli, J.; Gantner, G.S. Untersuchung der Retrogradation von Amylose (Investigation of the retrogradation of Amylose). Starch - Stärke 1960, 12, 73-77. [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.H.; Gidley, M.J.; Richardson, R.K.; Ross-Murphy, S.B. Rheological studies of aqueous amylose gels: the effect of chain length and concentration on gel modulus. Macromolecules 1989, 22, 346-351. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhan, J.; Shen, W.; Ma, R.; Tian, Y. Assessing Starch Retrogradation from the Perspective of Particle Order. Foods 2024, 13, 911. [CrossRef]

- Gidley, M.J.; Bulpin, P.V. Crystallisation of malto-oligosaccharides as models of the crystalline forms of starch: minimum chain-length requirement for the formation of double helices. Carbohydrate Research 1987, 161, 291-300. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, D.; Ying, Y.; Bao, J. Understanding starch biosynthesis in potatoes for metabolic engineering to improve starch quality: A detailed review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 346, 122592. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, Y.; Huang, T.; Gong, B.; Yu, W.-W. A combined action of amylose and amylopectin fine molecular structures in determining the starch pasting and retrogradation property. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 164, 2717-2725. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, Y. Antagonistic effects of amylopectin and amylose molecules on the starch inter- and intramolecular interactions during retrogradation. LWT 2021, 148, 111942. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.-H.; Sasaki, T.; Li, Y.-Y.; Yoshihashi, T.; Li, L.-T.; Kohyama, K. Effect of amylose content and rice type on dynamic viscoelasticity of a composite rice starch gel. Food Hydrocolloids 2009, 23, 1712-1719. [CrossRef]

- Slade, L.; Levine, H.; Reid, D.S. Beyond water activity: Recent advances based on an alternative approach to the assessment of food quality and safety. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 1991, 30, 115-360. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yu, L.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Chen, L.; Li, X. Glass transition temperature of starches with different amylose/amylopectin ratios. Journal of Cereal Science 2010, 51, 388-391. [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Kang, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, L.; Li, L. Identification of the Main Retrogradation-Related Properties of Rice Starch. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1562-1572. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, F.; Yu, L.; Chen, L.; Li, L. Thermal processing of starch-based polymers. Progress in Polymer Science 2009, 34, 1348-1368. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Christie, G. Microstructure and mechanical properties of orientated thermoplastic starches. Journal of Materials Science 2005, 40, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, H.; Yang, H.; Cui, M. Effects of salts on the freeze–thaw stability, gel strength and rheological properties of potato starch. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2016, 53, 3624-3631. [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. Starch re-crystallization kinetics as a function of various cations. Starch - Stärke 2011, 63, 792-800. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Chen, J.; Luo, S.-J.; Liu, C.-M.; Liu, W. Effect of food additives on starch retrogradation: A review. Starch - Stärke 2015, 67, 69-78. [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, W.; Tomasik, P. Thermal properties of complexes of amaranthus starch with selected metal salts. Thermochim. Acta 2003, 403, 161-171. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, C.; Copeland, L.; Niu, Q.; Wang, S. Starch Retrogradation: A Comprehensive Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2015, 14, 568-585. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chao, C.; Cai, J.; Niu, B.; Copeland, L.; Wang, S. Starch-lipid and starch-lipid-protein complexes: A comprehensive review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 1056-1079. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H. A comprehensive review of the factors influencing the formation of retrograded starch. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 186, 163-173. [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.; Awika, J.M. Effect of protein-starch interactions on starch retrogradation and implications for food product quality. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2023, 22, 2081-2111. [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.; Awika, J.M. Effect of protein–starch interactions on starch retrogradation and implications for food product quality. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2023, 22, 2081-2111. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Gong, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Qian, J.-Y.; Zhu, W. Effect of rice protein on the gelatinization and retrogradation properties of rice starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 242, 125061. [CrossRef]

- Carlstedt, J.; Wojtasz, J.; Fyhr, P.; Kocherbitov, V. Understanding starch gelatinization: The phase diagram approach. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 129, 62-69. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chao, C.; Huang, S.; Yu, J. Phase Transitions of Starch and Molecular Mechanisms. 2020; pp. 77-120.

- Chen, P.; Yu, L.; Kealy, T.; Chen, L.; Li, L. Phase transition of starch granules observed by microscope under shearless and shear conditions. Carbohydrate Polymers 2007, 68, 495-501. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Yu, L.; Liu, H.; Bao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L. Effect of pressure with shear stress on gelatinization of starches with different amylose/amylopectin ratios. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 72, 331-337. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Yu, L.; Liu, H.; Khalid, S.; Meng, L.; Chen, L. Preparation and characterization of starch-based composite films reinforced by corn and wheat hulls. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2017, 134. [CrossRef]

- Jiangping Ye, X.H., Shunjing Luo, Wei Liu, Jun Chen, Zhiru Zeng, Chengmei Liu. Properties of starch after extrusion: A review. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Jumaidin, R.; Mohd Zainel, S.N.; Sapuan, S.M. Chapter 2 - Processing of Thermoplastic Starch. In Advanced Processing, Properties, and Applications of Starch and Other Bio-Based Polymers, Al-Oqla, F.M., Sapuan, S.M., Eds.; Elsevier: 2020; pp. 11-19.

- Su, B.; Xie, F.; Li, M.; Corrigan, P.A.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Chen, L. Extrusion Processing of Starch Film. International Journal of Food Engineering 2009, 5. [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Yu, L.; Xie, F.; Chen, L.; Li, L. Rheological properties and phase transition of starch under shear stress. Food Hydrocolloids 2008, 22, 973-978. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Mai, S.; Li, C. Effects of Extrusion on Starch Molecular Degradation, Order–Disorder Structural Transition and Digestibility—A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 2538.

- Wang, K.; Tan, C.; Tao, H.; Yuan, F.; Guo, L.; Cui, B. Effect of different screw speeds on the structure and properties of starch straws. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 328, 121701. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Mai, S.; Li, C. Effects of Extrusion on Starch Molecular Degradation, Order-Disorder Structural Transition and Digestibility-A Review. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- González-Seligra, P.; Guz, L.; Ochoa-Yepes, O.; Goyanes, S.; Famá, L. Influence of extrusion process conditions on starch film morphology. LWT 2017, 84, 520-528. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Kealy, T.; Chen, P. Study of Starch Gelatinization in a Flow Field Using Simultaneous Rheometric Data Collection and Microscopic Observation. International Polymer Processing 2006, 21, 283-289. [CrossRef]

- Xixi Zeng, B.Z., Gengsheng Xiao, Ling Chen. Synergistic effect of extrusion and polyphenol molecular interaction on the short/long-term retrogradation properties of chestnut starch. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 276. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zheng, B.; Rao, C.; Chen, L. Effect of extrusion with hydrocolloid-starch molecular interactions on retrogradation and in vitro digestibility of chestnut starch and processing properties of chestnut flour. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 140, 108633. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Duan, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, F.; Shao, Z.; Shi, K.; Lin, X. How water acting as both blowing agent and plasticizer affect on starch-based foam. Industrial Crops and Products 2019, 134, 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.G.A.; da Silva, M.A.; dos Santos, L.O.; Beppu, M.M. Natural-based plasticizers and biopolymer films: A review. European Polymer Journal 2011, 47, 254-263. [CrossRef]

- Roz, A.; Carvalho, A.; Gandini, A.; Curvelo, A. The effect of plasticizers on thermoplastic starch compositions obtained by melt processing. Carbohydrate Polymers 2006, 63, 417-424. [CrossRef]

- Godbillot, L.; Dole, P.; Joly, C.; Roge, B.; Mathlouthi, M. Analysis of water binding in starch plasticized films. Food Chemistry 2006, 96, 380-386. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Alee, M.; Yang, M.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, L. Synergizing Multi-Plasticizers for a Starch-Based Edible Film. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, H.; Duan, Q.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, L. From macro- to nano- scales: Effect of fibrillary celluloses from okara on performance of edible starch film. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 262. [CrossRef]

- Juansang, J.; Puttanlek, C.; Rungsardthong, V.; Puncha-arnon, S.; Jiranuntakul, W.; Uttapap, D. Pasting properties of heat–moisture treated canna starches using different plasticizers during treatment. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 122, 152-159. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, B.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Effects of different proportions of erythritol and mannitol on the physicochemical properties of corn starch films prepared via the flow elongation method. Food Chemistry 2024, 437. [CrossRef]

- Alee, M.; Fu, J.; Duan, Q.; Yang, M.; Liu, H.; Zhu, J.; Xianyang, B.; Chen, L.; Yu, L. Plasticizing Effectiveness and Characteristics of Different Mono-Alcohols, Di-Alcohols, and Polyols for Starch-Based Materials. Starch - Stärke 2023, 75. [CrossRef]

- Alee, M.; Duan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Ali, A.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, T.; Rahaman, A.; Chen, L.; Yu, L. Plasticization Efficiency and Characteristics of Monosaccharides, Disaccharides, and Low-Molecular-Weight Polysaccharides for Starch-Based Materials. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021, 9, 11960-11969. [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Xu, J. Comparison of Single/Compound Plasticizer to Prepare Thermoplastic Starch in Starch-Based Packaging Composites. Materials Science 2019, 25. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, L.C.d.; Miranda, C.S.d.; Santos, W.J.d.; Gonçalves, A.P.B.; Oliveira, J.C.d.; José, N.M. Development of Starch Biofilms Using Different Carboxylic Acids as Plasticizers. Materials Research 2015, 18, 297-301. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Zambon, M.; Dasilvacurvelo, A.; Gandini, A. Thermoplastic starch modification during melt processing: Hydrolysis catalyzed by carboxylic acids. Carbohydrate Polymers 2005, 62, 387-390. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Han, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, D.; Tian, W. Characterization of citric acid/glycerol co-plasticized thermoplastic starch prepared by melt blending. Carbohydrate Polymers 2007, 69, 748-755. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, L.; Niu, C.; Hu, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhang, S.; Ren, J.; Qin, G.; Zhang, G.; et al. Effect of functional groups of plasticizers on starch plasticization. Colloid and Polymer Science 2024, 302, 1323-1335. [CrossRef]

- Montilla-Buitrago, C.E.; Gómez-López, R.A.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Serna-Cock, L.; Villada-Castillo, H.S. Effect of Plasticizers on Properties, Retrogradation, and Processing of Extrusion-Obtained Thermoplastic Starch: A Review. Starch - Stärke 2021, 73. [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhang, W.; Lou, F.; Wang, Y.; Guo, W. Characteristics of starch-based films produced using glycerol and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride as combined plasticizers. Starch - Stärke 2016, 69. [CrossRef]

- Mateyawa, S.; Xie, D.F.; Truss, R.W.; Halley, P.J.; Nicholson, T.M.; Shamshina, J.L.; Rogers, R.D.; Boehm, M.W.; McNally, T. Effect of the ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate on the phase transition of starch: Dissolution or gelatinization? Carbohydrate Polymers 2013, 94, 520-530. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.; Decaen, P.; Jacquet, P.; Coativy, G.; Pontoire, B.; Reguerre, A.-L.; Lourdin, D. Deep eutectic solvents as functional additives for starch based plastics. Green Chemistry 2012, 14, 3063-3066. [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, M. Starch treatment with deep eutectic solvents, ionic liquids and glycerol. A comparative study. Carbohydrate polymers 2020, 229, 115574. [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, M.; Johansson, C. Mechanical and barrier properties of starch-based films plasticized with two-or three component deep eutectic solvents. Carbohydrate Polymers 2016, 151, 103-112. [CrossRef]

- Compart, J.; Singh, A.; Fettke, J.; Apriyanto, A. Customizing Starch Properties: A Review of Starch Modifications and Their Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 3491. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ju, J.; Diao, Y.; Zhao, F.; Yang, Q. The application of starch-based edible film in food preservation: a comprehensive review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2024, 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Masina, N.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kumar, P.; du Toit, L.C.; Govender, M.; Indermun, S.; Pillay, V. A review of the chemical modification techniques of starch. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 157, 1226-1236. [CrossRef]

- Xiang Wanga, L.H., Caihong Zhang, Yejun Deng, Pujun Xie, Lujie Liu, Jiang Cheng. Research advances in chemical modifications of starch for hydrophobicity and its applications: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 250, 116292-116303. [CrossRef]

- Sneh Punia Bangar, A.O.A., Arashdeep Singh, Vandana Chaudhary, William Scott Whiteside. Enzymatic modification of starch: A green approach for starch applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 287, 119265-119292. [CrossRef]

- Mingyue Liu, X.W., Yihui Li, Danni Jin, Yuling Jiang, Yong Fang, Qinlu Lin, Yongbo Ding. Effects of OSA-starch-fatty acid interactions on the structural, digestibility and release characteristics of high amylose corn starch. Food Chemistry 2024, 454, 139742-139755. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Picchioni, F. Modification of starch: A review on the application of “green” solvents and controlled functionalization. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 241, 116350. [CrossRef]

- Md. Ruhul Amin, F.R.A., Md. Arif Mahmud, Shahriar Raian. Esterification of starch in search of a biodegradable thermoplastic material. Journal of Polymer Research 2020, 27. [CrossRef]

- Ji-Qiang Mei, D.-N.Z., Zheng-Yu Jin, Xue-Ming Xu, Han-Qing Chen Effects of citric acid esterification on digestibility, structural and physicochemical properties of cassava starch. Food Chemistry 2015, 187, 378–384. [CrossRef]

- Otache, M.A.; Duru, R.U.; Achugasim, O.; Abayeh, O.J. Advances in the Modification of Starch via Esterification for Enhanced Properties. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2021, 29, 1365–1379. [CrossRef]

- Nuswantari, S.R. Effect of chemical modification by oxidation and esterification process on properties of starch: A review. Eduvest Journal of Universal Studies 2022, 2, 2885-2896. [CrossRef]

- Effect ofRice Starch Hydrolysis and Esterification Processes on the Physicochemical Properties ofBiodegradable Films. Starch - Stärke 2021, 73, 2100022-2100030. [CrossRef]

- Ragavan, K.V.; Hernandez-Hernandez, O.; Martinez, M.M.; Guti´errez, T.J. Organocatalytic esterification of polysaccharides for food applications: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 119, 45-56. [CrossRef]

- Đurđica Ačkar, J.B.; Antun Jozinović , Borislav Miličević , Stela Jokić , Radoslav Miličević , Marija Rajič ,Drago Šubarić Starch Modification by Organic Acids and Their Derivatives: A Review. Molecules 2015, 20, 19554-19570. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, K.; Hu, J.; Xu, C.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, P. Synthesis of long-chain fatty acid starch esters in aqueous medium and its characterization. European Polymer Journal 2019, 119, 136-147. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zheng, H.; Yang, Y.; Bian, X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Sun, S.; et al. Effect of different chain-length fatty acids on the retrogradation properties of rice starch. Food Chemistry 2024, 461, 140796. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Jin, Y.; Hong, Y.; Gu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Li, Z.; Li, C. Effects of fatty acids with various chain lengths and degrees of unsaturation on the structure, physicochemical properties and digestibility of maize starch-fatty acid complexes. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 110, 106224. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X. Starch Modification and Application. In Starch Structure, Functionality and Application in Foods, Wang, S., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 131-149.

- Otache, M.A.; Duru, R.U.; Achugasim, O.; Abayeh, O.J. Advances in the Modification of Starch via Esterification for Enhanced Properties. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2021, 29, 1365-1379. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ren, M.H.; Bemiller, J. Developments in Hydroxypropylation of Starch: A Review. Starch - Starke 2018, 71. [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.M.; Haider, S.; Shaikh, M.; Butt, N.A.; Zehra, N. Chemical Crosslinking, Acid Hydrolysis, Oxidation, Esterification, and Etherification of Starch. In Advanced Research in Starch, Mazumder, N., Rahman, M.H., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 47-94.

- Milotskyi, R.; Bliard, C.; Tusseau, D.; Benoit, C. Starch carboxymethylation by reactive extrusion: Reaction kinetics and structure analysis. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 194, 193-199. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jung, C. Reaction Mechanisms Applied to Starch Modification for Biodegradable Plastics: Etherification and Esterification. International Journal of Polymer Science 2022, 2022, 2941406. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Cao, X.; Yu, J.; Su, H.; Wei, S.; Hong, H.; Liu, C. Quaternary Ammonium Groups Modified Starch Microspheres for Instant Hemorrhage Control. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2017, 159, 937-944. [CrossRef]

- Pooresmaeil, M.; Namazi, H. Developments on carboxymethyl starch-based smart systems as promising drug carriers: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 258, 117654. [CrossRef]

- Almonaityte, K.; Bendoraitiene, J.; Babelyte, M.; Rosliuk, D.; Rutkaite, R. Structure and properties of cationic starches synthesized by using 3-chloro-2-hydroxypropyltrimethylammonium chloride. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 164, 2010-2017. [CrossRef]

- Glover, P.A.; Rudloff, E.; Kirby, R. Hydroxyethyl starch: A review of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, current products, and potential clinical risks, benefits, and use. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 2014, 24, 642-661. [CrossRef]

- Zia ud, D.; Xiong, H.; Fei, P. Physical and chemical modification of starches: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 57, 2691-2705. [CrossRef]

- Clasen, S.H.; Müller, C.M.O.; Parize, A.L.; Pires, A.T.N. Synthesis and characterization of cassava starch with maleic acid derivatives by etherification reaction. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 180, 348-353. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Xie, F.; Chen, L. Oxidation-induced starch molecular degradation: A comprehensive kinetic investigation using NaClO/NaBr/TEMPO system. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 277, 134283. [CrossRef]

- Olawoye, B.; Jolayemi, O.S.; Akinyemi, T.Y.; Nwaogu, M.; Oluwajuyitan, T.D.; Popoola-Akinola, O.O.; Fagbohun, O.F.; Akanbi, C.T. Modification of Starch. In Starch: Advances in Modifications, Technologies and Applications, Sharanagat, V.S., Saxena, D.C., Kumar, K., Kumar, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 11-54.

- Dimri, S.; Aditi; Bist, Y.; Singh, S. Oxidation of Starch. In Starch: Advances in Modifications, Technologies and Applications, Sharanagat, V.S., Saxena, D.C., Kumar, K., Kumar, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 55-82.

- Olawoye, B.; Jolayemi, O.S.; Origbemisoye, B.A.; Oluwajuyitan, T.D.; Popoola-Akinola, O. Hydrolysis of Starch. In Starch: Advances in Modifications, Technologies and Applications, Sharanagat, V.S., Saxena, D.C., Kumar, K., Kumar, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 83-101.

- Vanier, N.L.; El Halal, S.L.M.; Dias, A.R.G.; da Rosa Zavareze, E. Molecular structure, functionality and applications of oxidized starches: A review. Food Chem 2017, 221, 1546-1559. [CrossRef]

- Cahyana, Y.; Verrell, C.; Kriswanda, D.; Aulia, G.A.; Yusra, N.A.; Marta, H.; Sukri, N.; Esirgapovich, S.J.; Abduvakhitovna, S.S. Properties Comparison of Oxidized and Heat Moisture Treated (HMT) Starch-Based Biodegradable Films. Polymers 2023, 15, 2046. [CrossRef]

- Oluwasina, O.O.; Olaleye, F.K.; Olusegun, S.J.; Oluwasina, O.O.; Mohallem, N.D.S. Influence of oxidized starch on physicomechanical, thermal properties, and atomic force micrographs of cassava starch bioplastic film. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 135, 282-293. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Copeland, L. Effect of acid hydrolysis on starch structure and functionality: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2015, 55, 1081-1097. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Copeland, L. Effect of Acid Hydrolysis on Starch Structure and Functionality: A Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2015, 55, 1081-1097. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jia, H.; Wang, B.; Ma, C.; He, F.; Fan, Q.; Liu, W. A Prospective Review on the Research Progress of Citric Acid Modified Starch. Foods 2023, 12, 458. [CrossRef]

- Meimoun, J.; Wiatz, V.; Saint-Loup, R.; Parcq, J.; Favrelle, A.; Bonnet, F.; Zinck, P. Modification of starch by graft copolymerization. Starch - Stärke 2018, 70, 1600351. [CrossRef]

- Sarder, R.; Piner, E.; Rios, D.C.; Chacon, L.; Artner, M.A.; Barrios, N.; Argyropoulos, D. Copolymers of starch, a sustainable template for biomedical applications: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022, 278, 118973. [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, A.N.; Carvalho, A.J.F. Starch-g-Copolymers: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. In Polysaccharide Based Graft Copolymers, Kalia, S., Sabaa, M.W., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; pp. 59-109.

- Bhattacharya, A.; Misra, B.N. Grafting: a versatile means to modify polymers: Techniques, factors and applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2004, 29, 767-814. [CrossRef]

- Noordergraaf, I.-W.; Fourie, T.K.; Raffa, P. Free-Radical Graft Polymerization onto Starch as a Tool to Tune Properties in Relation to Potential Applications. A Review. Processes 2018, 6, 31. [CrossRef]

- Noordergraaf, I.-W.; Witono, J.R.; Heeres, H.J. Grafting Starch with Acrylic Acid and Fenton’s Initiator: The Selectivity Challenge. Polymers 2024, 16, 255. [CrossRef]

- Weerapoprasit, C.; Prachayawarakorn, J. Characterization and properties of biodegradable thermoplastic grafted starch films by different contents of methacrylic acid. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 123, 657-663. [CrossRef]

- N.L. Tai, R.A., Robert Shanks, Benu Adhikari. Flexible starch-polyurethane films: Physiochemical characteristics and hydrophobicity. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 163, 236–246. [CrossRef]

- Tai, N.L.; Adhikari, R.; Shanks, R.; Adhikari, B. Starch-polyurethane films synthesized using polyethylene glycol-isocyanate (PEG-iso): Effects of molecular weight, crystallinity, and composition of PEG-iso on physiochemical characteristics and hydrophobicity of the films. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2017, 14, 116-127. [CrossRef]

- Jariyasakoolroj, P.; Chirachanchai, S. Silane modified starch for compatible reactive blend with poly(lactic acid). Carbohydrate Polymers 2014, 106, 255-263. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, T.; Mazela, B.; Olejnik, K.; Peplińska, B.; Perdoch, W. Starch-Silane Structure and Its Influence on the Hydrophobic Properties of Paper. Molecules 2022, 27, 3136. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, W.; Peng, S. High-performance poly(lactic acid)/starch materials prepared via starch surface modification and its in situ enhancement. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2024, 141, e55041. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, J.; Feng, X.; Qin, Z. Cellulose Nanofiber-Assisted Dispersion of Halloysite Nanotubes via Silane Coupling Agent-Reinforced Starch–PVA Biodegradable Composite Membrane. Membranes 2022, 12, 169. [CrossRef]

- Ojogbo, E.; Ogunsona, E.O.; Mekonnen, T.H. Chemical and physical modifications of starch for renewable polymeric materials. Materials Today Sustainability 2020, 7-8, 100028. [CrossRef]

- Garavand, F.; Rouhi, M.; Razavi, S.H.; Cacciotti, I.; Mohammadi, R. Improving the integrity of natural biopolymer films used in food packaging by crosslinking approach: A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 104, 687-707. [CrossRef]

- Narudom Srisawang, S.N., Supa Wirasate, Chayanisa Chitichotpanya. pH-Induced Crosslinking of Rice Starch via Schiff Base Formation. Macromolecular Research 2019. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.; Yang, Y. Citric acid cross-linking of starch films. Food Chemistry 2010, 118, 702-711. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, G.A.; Bezerra, M.C.; Bettini, S.H.P.; Lucas, A.A. Real-time monitoring of the starch cross-linking with citric acid by chemorheological analysis. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 311, 120733. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kong, L.; Ziegler, G.R. Fabrication of starch - Nanocellulose composite fibers by electrospinning. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 90, 90-98. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lei, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, C.; Cheng, J.; Wang, J.; Meng, W.; Liu, M. The Study of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF-8) Doped Polyvinyl Alcohol/Starch/Methyl Cellulose Blend Film. Polymers 2019, 11, 1986. [CrossRef]

- Ayorinde, J.O.; Odeniyi, M.A.; Balogun-Agbaje, O. Formulation and Evaluation of Oral Dissolving Films of Amlodipine Besylate Using Blends of Starches With Hydroxypropyl Methyl Cellulose. Polimery w medycynie 2016, 46, 45-51. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, K.M.; Campos, A.d.; Mitsuyuki, M.C.; Luchesi, B.R.; Marconcini, J.M. Corn and cassava starch with carboxymethyl cellulose films and its mechanical and hydrophobic properties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 223, 115055. [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Zhang, R.; Ji, T.; Sameen, D.E.; Ahmed, S.; Qin, W.; Dai, J.; He, L.; Liu, Y. Improving nisin production by encapsulated Lactococcus lactis with starch/carboxymethyl cellulose edible films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 251, 117062. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, T.J.; Alvarez, V.A. Cellulosic materials as natural fillers in starch-containing matrix-based films: a review. Polymer Bulletin 2016, 74, 2401-2430. [CrossRef]

- Mahardika, M.; Amelia, D.; Azril; Syafri, E. Applications of nanocellulose and its composites in bio packaging-based starch. Materials Today: Proceedings 2023, 74, 415-418. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Liu, H.; Xie, H.; Fu, J.; Chen, L.; Yu, L. Preparation and characterization of nanofibrillar cellulose obtained from okara via synergizing chemical and physical functions. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 203. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liza, A.A.; Yang, G.; Sipponen, M.H.; Guo, J.; Li, H. Nanocellulose: a review on preparation routes and applications in functional materials. Cellulose 2023, 30, 4115-4147. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.M.; Chawraba, K.; El Mogy, S.A. Nanocellulose: A Comprehensive Review of Structure, Pretreatment, Extraction, and Chemical Modification. Polymer Reviews 2024, 1-62. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xu, H.; Zhao, H.; Xu, M.; Qi, M.; Yi, T.; An, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Huang, C.; et al. Properties of thermoplastic starch films reinforced with modified cellulose nanocrystals obtained from cassava residues. New Journal of Chemistry 2019, 43, 14883-14891. [CrossRef]

- Bangar, S.P.; Whiteside, W.S. Nano-cellulose reinforced starch bio composite films- A review on green composites. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 185, 849-860. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Abdulkhani, A.; Tahir, P.M.; Dufresne, A. Effect of cellulosic fiber scale on linear and non-linear mechanical performance of starch-based composites. Int J Biol Macromol 2016, 91, 1040-1044. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Jiao, X.; Li, Q. The effects of cellulose nanocrystal and cellulose nanofiber on the properties of pumpkin starch-based composite films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 192, 444-451. [CrossRef]

- Mariano, M.; Chirat, C.; El Kissi, N.; Dufresne, A. Impact of cellulose nanocrystal aspect ratio on crystallization and reinforcement of poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate). Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics 2016, 54, 2284-2297. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Qian, S.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, J. The impact of esterified nanofibrillated cellulose content on the properties of thermoplastic starch/PBAT biocomposite films through ball-milling. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 127462. [CrossRef]

- Oswaldo Ochoa-Yepes, L.D.G., Silvia Goyanes, Adriana Mauri, Lucía Famá. Influence of process (extrusion/thermo-compression, casting) and lentil protein content on physicochemical properties of starch films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 208, 221–231. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Long, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L. Preparation and performance of thermoplastic starch and microcrystalline cellulose for packaging composites: Extrusion and hot pressing. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 165, 2295-2302. [CrossRef]

- do Val Siqueira, L.; Arias, C.I.L.F.; Maniglia, B.C.; Tadini, C.C. Starch-based biodegradable plastics: methods of production, challenges and future perspectives. Current Opinion in Food Science 2021, 38, 122-130. [CrossRef]

- Versino, F.; Lopez, O.V.; Garcia, M.A.; Zaritzky, N.E. Starch-based films and food coatings: An overview. Starch - Stärke 2016, 68, 1026-1037. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Dong, Y.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Sui, G. Novel sandwiched structures in starch/cellulose nanowhiskers (CNWs) composite films. Composites Communications 2017, 4, 5-9. [CrossRef]

- Fourati, Y.; Magnin, A.; Putaux, J.L.; Boufi, S. One-step processing of plasticized starch/cellulose nanofibrils nanocomposites via twin-screw extrusion of starch and cellulose fibers. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 229, 115554. [CrossRef]

- Alves, Z.; Brites, P.; Ferreira, N.M.; Figueiredo, G.; Otero-Irurueta, G.; Gonçalves, I.; Mendo, S.; Ferreira, P.; Nunes, C. Thermoplastic starch-based films loaded with biochar-ZnO particles for active food packaging. Journal of Food Engineering 2024, 361, 111741. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Lu, R.; Xu, J.; Hu, K.; Liu, Y. Preparation of Chitosan/Corn Starch/Cinnamaldehyde Films for Strawberry Preservation. Foods 2019, 8, 423. [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.-q.; Li, F.-y.; Li, J.-y.; Li, J.-f.; Zhang, C.-w.; Chen, S.; Sun, X.; Cui, J.-f. Optimisation of compatibility for improving elongation at break of chitosan/starch films. RSC Advances 2019, 9, 24451-24459. [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yan, X.; Zhou, J.; Tong, J.; Su, X. Influence of chitosan concentration on mechanical and barrier properties of corn starch/chitosan films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 105, 1636-1643. [CrossRef]

- Martins da Costa, J.C.; Lima Miki, K.S.; da Silva Ramos, A.; Teixeira-Costa, B.E. Development of biodegradable films based on purple yam starch/chitosan for food application. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03718. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Khan, M.R.; Ahmad, I.; Sadiq, M.B. Recent advances in modified starch based biodegradable food packaging: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Qiao, D.; Zhao, S.; Lin, Q.; Wang, J.; Xie, F. Starch-based food matrices containing protein: Recent understanding of morphology, structure, and properties. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 114, 212-231. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Duan, Q.; Zhu, J.; Liu, H.; Yu, L. Starch-based biodegradable materials: Challenges and opportunities. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research 2020, 3, 8-18. [CrossRef]

- Romani, V.P.; Prentice-Hernández, C.; Martins, V.G. Active and sustainable materials from rice starch, fish protein and oregano essential oil for food packaging. Industrial Crops and Products 2017, 97, 268-274. [CrossRef]

- Chinma, C.E.; Ariahu, C.C.; Abu, J.O. Development and characterization of cassava starch and soy protein concentrate based edible films. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2012, 47, 383-389. [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, F.M.; Costa, D.; Yamashita, F.; Martelli, S.M.; Jesus, R.C.; Alganer, K.; Collares-Queiroz, F.P.; Innocentini-Mei, L.H. Comparative study of processing methods for starch/gelatin films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2013, 95, 681-689. [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Imam, S.; Gordon, S.; Cinelli, P.; Chiellini, E. Extruded Cornstarch-Glycerol-Polyvinyl Alcohol Blends: Mechanical Properties, Morphology, and Biodegradability. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2000, 8, 205-211. [CrossRef]

- Sin, L.T.; Rahman, W.A.W.A.; Rahmat, A.R.; Samad, A.A. Computational modeling and experimental infrared spectroscopy of hydrogen bonding interactions in polyvinyl alcohol–starch blends. Polymer 2010, 51, 1206-1211. [CrossRef]

- Siddaramaiah; Raj, B.; Somashekar, R. Structure–property relation in polyvinyl alcohol/starch composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2004, 91, 630-635. [CrossRef]

- Abedi-Firoozjah, R.; Chabook, N.; Rostami, O.; Heydari, M.; Kolahdouz-Nasiri, A.; Javanmardi, F.; Abdolmaleki, K.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. PVA/starch films: An updated review of their preparation, characterization, and diverse applications in the food industry. Polymer Testing 2023, 118, 107903. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Duan, Q.; Zhu, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Yu, L. Anchor and bridge functions of APTES layer on interface between hydrophilic starch films and hydrophobic soyabean oil coating. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 272. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Duan, Q.; Ji, Z.; Chen, L. Superhydrophobic Modification on Starch Film Using PDMS and Ball-Milled MMT Coating. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2020, 8, 10423-10430. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Bao, X.; Yu, L.; Cui, F.; Zahid, N.; Liu, F.; Zhu, J.; Liu, H. Study on hydroxypropyl corn starch/alkyl ketene dimer composite film with enhanced water resistance and mechanical properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 126613. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).