1.1. General Review

The Second Law of Thermodynamics is one of the most remarkable physical laws for its profound meaning, its deep implications in every field of physics and for the several applications in other fields of science such as any field of engineering, chemistry, biology, genetics, medicine and, more generally, in natural sciences.

In simple terms, according to the first Clausius statement (Clausius I statement) the Second Law of Thermodynamics states that the transfer of heat from a higher-temperature reservoir to a lower-temperature reservoir is spontaneous and continue until thermal equilibrium is established. Instead, the transfer of heat from a lower-temperature reservoir to a higher-temperature reservoir is not spontaneous and occurs only if work is done. More profoundly, the understanding of heat and energy and their interplay requires the knowledge of both the First Law of Thermodynamics and the Second Law of Thermodynamics [

44].

Thanks to the introduction of the concept of entropy

S by Clausius studying the relation between heat transfer and work as a form of heat energy it can be stated a second form of the Second Law of Thermodynamics which can be identified with the second Clausius statement (Clausius II statement) for closed and isolated thermodynamic systems subjected to reversible processes in terms of entropy change: entropy does not decrease, namely

. Entropy variation

is equal to the ratio of heat

Q reversibly exchanged with the environment and the thermodynamic temperature

T at which this exchange occurs, viz.

. If the heat is absorbed from the environment by the thermodynamic system it is

leading to

, while if it is released by the system to the environment it is

. Here,

indicates the finite variation experienced either by entropy or by heat when the thermodynamic system passes from its initial to its final state supposed in thermodynamic equilibrium. The relationship between entropy and heat energy in terms of their variations can be regarded as the quantitative formulation of the Second Law of Thermodynamics based on a classical framework [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This relationship has been given by Clausius also in differential form and for reversible processes it is

where

is the infinitesimal entropy change due to the infinitesimal heat

reversibly exchanged. It should be emphasized that, while

is not an exact differential,

is a complete (exact) differential due to the integrating factor

so that

S is a function of state depending only on the initial and final thermodynamic states.

An equivalent formulation of the Second Law of Thermodynamics is represented by the Kelvin statement according to which it is not possible to convert all the heat absorbed from an external reservoir at higher temperature into work: part of it will be transferred to an external reservoir at a lower temperature. The roots were laid in [

11,

12] where are discussed the consequences of Carnot’s proposition that there is a waste of mechanical energy when heat is allowed to pass from one body to another at a lower temperature. This statement has been historically referred to as the Kelvin-Planck statement [

10,

13]. However, after Kelvin another pioneer of this principle was Ostwald who completed the Kelvin statement by formulating the

perpetuum mobile kind II. For this reason, in this paper, we combine the two pioneering contributions referring to the Kelvin-Ostwald statement. The role of Planck was marginal in the formulation of this principle but was mainly focused in its divulgation within the scientific community.

In strict relation with the above mentioned general statements, it can be stated that, according to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, it is impossible to realize a perpetuum motion machine of the second kind or

perpetuum mobile kind II able to use the internal energy of only one heat reservoir (see also

Section 1.2 for more details).

As a general note, the entity of entropy variations in the Second Law of Thermodynamics applied to isolated thermodynamic systems allows the distinction between reversible processes, ideal processes for which

(

), and irreversible processes, real processes for which

(

). To study reversible and irreversible thermodynamic processes it is not sufficient to consider the thermodynamic system itself but also its local and nonlocal surroundings defining together with the system what is called the thermodynamic universe [

10,

13]. It describes the constructive role of entropy growth and makes the case that energy matters, but entropy growth matters more.

At a later time, the Second Law of Thermodynamics has been reformulated mathematically and geometrically still in a classical thermodynamics framework, through the so called Carathéodory’s principle [

18] that exists in different formulations appearing in textbooks and articles (see e.g. [

10,

13]) even though very similar one to the other. Following Koczan [

14] Carathéodory’s principle states: "In the surroundings of each thermodynamic state, there are states that cannot be achieved by adiabatic processes". Often this statement has been given without a rigorous proof of equivalence with other formulations but it has been also proved even though not so rigorously that this principle is a direct consequence of Clausius and Kelvin statements [

19,

20,

21]. However, a recent critique of this principle [

22] has allowed to know that it received a strong criticism already by Planck and the issue related to its necessity and validity is still an open debate.

Afterwards, the Second Law of Thermodynamics has acquired a more general significance when it has been introduced a statistical physics definition of entropy by Boltzmann and Planck[

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] and then generalized by the same Boltzmann [

30] and by Gibbs [

31], an aspect not discussed in [

13]. The main advancement contained in the celebrated Boltzmann probabilistic formula proposed within his kinetic theory of gases,

with

the Boltzmann constant and

the number of microstates which characterize a gas’s macrostate. This formula was put forward and interpreted later by Planck [

29] and is also known as the Boltzmann-Planck relationship: the entropy of a thermodynamic system is proportional to the number of ways its atoms or molecules can be arranged in different thermodynamic microstates. If the occupation probabilities of every microstate are different it can be shown that Boltzmann formula is written in the Gibbs form or Boltzmann-Gibbs form valid also for states far from thermodynamic equilibrium,

with

the probability that microstate

i has energy

during the system energy fluctuation. It is straightforward to show that the Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy infinitesimal change in a canonical ensemble is equivalent to the Clausius entropy change and, thanks to this equivalence, the Second Law of Thermodynamics is formulated also within a statistical physics approach.

It is important to point out that, very recently, Koczan has shown that Clausius and Kelvin statements are not exhaustive formulations of the Second Law of Thermodynamics if compared to the Carnot more complete formulation [

14]. Specifically, it has been proved that the Kelvin principle is a weaker statement (or more strictly non-equivalent) than the Clausius classical principle (Clausius I principle), and the Clausius I principle is a weaker statement than Carnot principle, which can be considered equivalent to Clausius II principle. By indicating the heat absorbed by a heat source at temperature

with

(

) and the work resulting from the conversion of heat with

W in the device operating between the heat source and the heat receiver at temperature

Carnot principle states that

with

the efficiency

: the efficiency of the heat

conversion process to work

W in the device operating in the range between

and

cannot be greater than the ratio of the difference between the two temperatures and the temperature of the heat source. In this paper a criticism is made to Caratheodory’s principle showing that there is not a real equivalence among this principle and Clausius and Kelvin statements of the Second Law of Thermodynamics contrary to what is asserted in texbooks. Particular attention is also paid to the problem of deriving the Second Law of Thermodynamics from statistical physics. It is also reexamined revised and clarified the problem of reversibility and irreversibility in relation to the usual formulation of the Second Law of Thermodynamics in terms of increasing entropy showing that it cannot be always considered a fundamental and elementary law of statistical physics and, in some cases, even not completely true as recently proved via the fluctuation theorem [

39,

44]. At the same time, it is also proved that the Second Law of Thermodynamics is a phenomenological law of nature working extremely well for describing the behavior of several thermodynamic systems. In this respect, one of the aims of this work is to explain the above mentioned dissonance basing on precise and novel formulations of the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

This paper is organized as follows: in

Section 1 are reviewed the basic definitions of phenomenological thermodynamics, the statistical definitions of entropy and the fluctuation theorem.

Section 2 is devoted to some general clarifications of the Second Law of Thermodynamics in its purely phenomenological and classical form, while

Section 3 deals with some important clarifications of it in statistical physics. Conclusions are drawn in

Section 4.

1.2. Basic Definitions of Phenomenological Thermodynamics

A very important concept that led to the formulation of the laws of thermodynamics was perpetuum mobile. However, even in the classical sense, there are several types of them. It is therefore worth clarifying this type terminology now, so that it can be further developed and used effectively in later sections of the article.

Perpetuum mobile is most often understood to mean a hypothetical device that would operate contrary to the accepted laws of physics. Usually by perpetuum mobile we mean a heat engine or a heat machine - so it has the following basic definitions:

Definition 1 (Perpetuum mobile kind 0 and I) "Perpetuum mobile" kind zero is a hypothetical device that moves forever without power, which appears to be free from resistance to motion. This device neither performs work nor emits heat. However, a "perpetual motion" kind one is a hypothetical device that performs work from nothing or almost nothing (it has an efficiency of infinite or greater than 100%).

Sometimes perpetuum mobile kind 0 is referred to as kind III. However, number 0 better reflects the original Latin meaning of the word (from Latin perpetuum mobile=perpetual motion), and number III will be used further. However, in traditional thermodynamics, the greatest emphasis, not necessarily rightly, was placed on number II.

Definition 2 (Perpetuum mobile kind II) "Perpetuum mobile" kind two is a hypothetical lossless operating warm engine with an efficiency of exactly 100%.

It is quite obvious that kind I and II do not exist, but it is not clear that kind 0 cannot exist. For example, the solar system, which has existed in an unchanged form for millions of years, seems to be kind 0 in kinematic terms. Of course, we assume here that the energy of the Sun’s thermonuclear processes does not directly affect the motion of the planets.

Since the First Law of Thermodynamics was recognized historically later than the Second one, we will introduce a special form of the First Law for the needs of the Second Law.

Definition 3 (First Law of Thermodynamics for two heat reservoirs)

We consider thermal processes taking place in contact with two reservoirs: a radiator with a temperature of and a cooler with a temperature of . We will denote the heat released by the radiator by and the heat absorbed by the cooler by . We assume that we can only transfer work to the environment or absorb work , but we cannot remove or absorb heat from the environment. Therefore, the principle of conservation of energy for the process takes the form:

which can be written, following the example of the First Law of Thermodynamics, as an expression for the change in the internal energy

E of the system:

In the set of processes, all possible signs and zeros are allowed for the quantities that meet the condition (1) or (2). In addition, thermodynamic processes can be combined (added), but not necessarily subtracted.

The specific form of the First Law of Thermodynamics for a system of two reservoirs results from the assumption of only internal heat exchange. The definition of the first law formulated in this way creates a space of energetically allowed processes for the second law. However, the second rule introduces certain restrictions on these processes (see [

14]).

Definition 4 (Clausius First Statement) Heat naturally flows from a body at a higher temperature to a body at a lower temperature. Therefore, a direct (not forced by work) process of heat transfer from the body at a lower temperature to the body at a higher temperature is not possible. Clausius First Principle allows for a large set (sets) of possible physical processes, the addition of which does not violate the above rule or the First Law of Thermodynamics.

Definition 5 (Kelvin–Ostwald Statement) The processes of converting heat to work and work to heat do not run symmetrically. A full conversion of work to heat (internal energy) is possible. However, a full conversion of the heat to the work is not possible in a cyclical process. In other words, there is no Perpetuum Mobile Second Kind. The Kelvin–Ostwald principle allows for the existence of a large set (sets) of possible physical processes, the addition of which does not create a Perpetuum Mobile Second Kind and does not violate the First Law of Thermodynamics.

To provide a more comprehensive statement of the second law of thermodynamics, thermodynamic entropy must be defined. It turns out that this can be done in thermodynamics in three subtly different ways. We will see further that in statistical mechanics, contrary to appearances, there are even more possibilities.

Definition 6 (C-type Entropy for Reservoirs)

There is a thermodynamic function of the state of a system of two heat reservoirs. Its change is equal to the sum of the ratio of heat absorbed by these reservoirs to the absolute temperature of these reservoirs:

The minus sign results from the convention that a reservoir with a higher temperature releases heat (for ). However, if , then under the same convention, the reservoir with temperature will absorb heat.

In this version, the total entropy change of the heat reservoirs is considered. We assume that the devices operating between these reservoirs operate cyclically, so their entropy should not change. The definition of type C entropy assumes that the heat capacity of the reservoirs is so large that the heat flow does not change their temperatures. Following Clausius, we can of course generalize the definition of entropy to processes with changing temperature:

Definition 7 (

Q-type Clausius Entropy)

The entropy change of a thermodynamic system or part of it is the integral of the heat gain divided by the temperature of that system or part of it:

It turns out that in certain irreversible processes, entropy increases despite the lack of heat flow. Therefore, we can further generalize the entropy formula, e.g. for the expansion of gas into a vacuum [

15]:

Definition 8 (

V-type Entropy)

The entropy change of a gas is equal to the integral of the sum of the increase in internal energy and the product of the pressure and the increase in volume divided by the temperature of the gas:

Entropies of type

V and

Q seem apparently equal, but it will be shown below that this need not be the case - which also applies to entropy of type C. However, for any entropy (by default type C or

Q) the following are considered the most popular statement of the second law of thermodynamics (see [

14]):

Definition 9 (Clausius Second Statement)

There is a function of the state of the thermodynamic system called entropy, which the dependence of the value on time allows to determine the system’s following of the thermodynamic equilibrium. Namely, in thermally insulated systems, the only possible processes are those in which the total entropy of the system (two heat reservoirs) does not decrease:

For reversible processes, the increase in total entropy is zero, and for irreversible processes it is greater than zero. The same principle can also be applied to Q-type or V-type entropy for a gas system. Then the additivity of entropy for the components of the system must also be respected.

Assuming a given definition of entropy and thanks to the principle of its additivity, the Clausius Second Statement is a direct condition for every process (possible and impossible). Therefore, this principle immediately states which process is possible and which is impossible and should be rejected according to this principle.

However, Clausius First Statement and Kelvin-Olstwald Statement allow us to reject only some of the impossible processes. We reject the remaining part of the impossible processes on the basis of adding processes leading to the impossible ones. Possible processes are those which, as a result of arbitrary addition, do not lead to impossible processes. It has been shown that the Clausius Second Statement is stronger and not equivalent to the Clausius Fist Statement and the Kelvin-Ostwald Statement. [

14].

1.3. A Review of Statistical Definitions of Entropy and Application to Ideal Gas

It is also worth considering statistical definitions of entropy. Contrary to appearances, this issue is not disambiguated in relation to phenomenological thermodynamics. On the contrary, there are many different aspects and cases of entropy in statistical physics. It is probably not even possible to talk about a strict universal definition, but only about definitions for characteristic types of statistical systems. Most often, definitions of entropy in statistical physics refer implicite to an equilibrium situation - that is, a state with the maximum possible entropy. From the point of view of the analysis of the second law of thermodynamics, this situation seems loopy - we postulate entropy maximization, but we define maximum entropy. However, dividing the system into subsystems makes sense of such a procedure. This shows a sample of the problem of defining entropy and the problem of precisely formulating the second law of thermodynamics. Boltzmann’s general definition is considered to be the first historical static definition of entropy:

Definition 10 (General Boltzmann entropy for number of microstates)

Entropy of the state of a macroscopic system is a logarithmic measure of the number of microstates that can realize a given macrostate, assuming a small but finite resolution of distinguishing microscopic states (in terms of location in the volume and values of speed, energy or temperature):

where the proportionality coefficient is Boltzmann’s constant . The counting of states in quantum mechanics is arbitrary in the sense that it depends on the sizes of the elementary resolution cells. However, due to the property of the logarithm function for large numbers, the resolution parameters should only affect the entropy value in an additive way. In the framework of quantum mechanics, counting states is more literal, but for example, for an ideal gas without rotational degrees of freedom it should lead to essentially the same entropy value.

However, the entropy defined in this way cannot be completely unambiguous as to the additive constant. Even in quantum mechanics, not all microstates are completely quantized, so there must be an element of arbitrariness in the choice of resolution parameters. Even if the quantum mechanics method for an ideal gas were unambiguous, it should be realized that at low temperatures such a method loses its physical sense and cannot be consistent with experiment. Therefore, to eliminate the freedom of constant additive entropy, the third law of thermodynamics is introduced, which postulates zeroing of entropy as the temperature approaches zero. However, such a principle has only a conventional and definitional character and cannot be treated as a fundamental solution - and should not even be treated as a law of physics. Moreover, it does not apply to an ideal gas because no constant will eliminate the logarithm singularity at zero temperature.

Sometimes in the definition of Boltzmann entropy other symbols are used instead of : or . However, the use of the Greek letter omega may be misleading because it suggests a reference to all microstates of the system, not just those that realize a given macrostate. Therefore, in this article it was decided to use the letter , just like on Boltzmann’s tombstone - but in a decorative version to distinguish it from the work symbol W.

Until we specify what microstates we consider to realize a given macrostate, then: (i) we do not even know whether we can count microstates of the non-equilibrium type in the entropy formula. Similarly, it is not clear: (ii) can Botzmann’s definition apply to non-equilibrium macrostates? Regarding problem (ii), it seems that the Boltzmann definition can be used for non-equilibrium states, even though the equilibrium entropy formulas are most often given. The latter results from the simple fact that the equilibrium state is described by fewer parameters. For example, when specifying the parameters of the gas state, we mean (consciously or not) the equilibrium state. Therefore, consistently regarding (i), if we have a non-equilibrium macrostate, then its entropy must be calculated after the non-equilibrium microstates. If the macrostate is in equilibrium, it is logical to count the entropy after the microstates relating to equilibrium. Unfortunately, some definitions of entropy force the counting of non-equilibrium states. This is the case, for example, in the microcanonical complex, in which one should consider a state in which one particle has taken over the energy of the entire system. Fortunately, this condition has a negligible importance (probability), so problem (i) is not critical. This is because probability, the second law of thermodynamics, and entropy distinguish equilibrium states. However, this distinction is a result of the nature of things and should not be put into place by hand at the level of definition.

It is worth making the definition of Boltzmann entropy a bit more specific. Let us consider a large

set of identical particles (but not necessarily quantum indistinguishable). Let us assume that we recognize a given macrostate as a specific filling of

k cells into which the phase space has been divided (the space of positions and momenta of one particle - not to be confused with the full configuration space of all particles). Each cell contains a certain number of particles, e.g. in the

ith cell there are

particles. Of course, the number of particles must sum to

N:

Now the possible number of all configurations is equal to the number of permutations with repetitions, because we do not distinguish permutations within one cell:

In mathematical considerations, one should be prepared for a formally infinite number of cells k and, consequently, fractional or even smaller than unity values of . However, even in such cases it is possible to calculate a finite number of states . Taking the above into account, let’s define the Boltzmann entropy in relation to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution:

Definition 11 (Boltzmann entropy at a specific temperature)

The entropy of an equilibrium macroscopic system with volume V and temperature T, composed of N "point" particles, is a logarithmic measure of the number of microstates that can realize this homogeneous macrostate assuming small volume cells in the space of positions υ and the space of momentum μ:

where the proportionality coefficient is Boltzmann’s constant . The counting of states within classical mechanics is arbitrary here, in the sense that it depends on the volume of the unit cells. However, thanks to the property of the logarithm function for large numbers, these parameters only affect the additive entropy constant (and also allow the arguments of the logarithmic function to be written in dimensionless form).

An elementary formula for this type of Boltzmann entropy can be derived using the formula (

9) for the distribution in space cells and the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for momentum space (the temperature-dependent part) [

32,

33]:

where the cell size of the shoot space has been replaced for simplicity by the equivalent temperature "pixel":

where

m is the mass of one particle.

In the formula (

11), what is disturbing is the presence of an extensive variable

V in the logarithm, instead of an intensive combination of variables

. In the [

32,

33] derivation, division by

N does not appear implicitly via an additive constant either. The question is whether it is an error of this type of derivation (in two sources) or an error of the definition, which should, for example, include some dividing factor of the Gibbs type? This issue is taken up further in this work. However, it is worth seeing that in the volume part the formula (

11) for

of air gives an entropy more than twice as large as for

– and it shouldn’t be like that.

The second doubt concerns the coefficient

in the expression

in the derivations of [

32,

33], which also appears in the entropy derived by Sackur in 1913 (see [

34]). In further alternative calculations the ratio is

– e.g. in Tetrode’s calculations of 1912 (see [

34]). It is worth adding that we are considering here a gas of material "points" (so-called monatomic) with the number of degrees of freedom for a determinate particle of 3, not 5. It is therefore difficult to indicate the reason for the discrepancy and to determine whether it is important due to the frequent omission of the considered term (or terms conditioned by "random" constants). There is quite a popular erroneous opinion that the considered term can only be derived on the basis of statistical mechanics, and it cannot be done within the framework of phenomenological thermodynamics. Namely, if, at a constant volume, we start to increase the number of particles with the same temperature, then, according to the definition of the

V type, we will obtain the entropy term under consideration with the coefficient

. However, if the same were calculated formally at constant pressure, the coefficient would be

.

A steady-temperature state subject to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution is effectively a canonical ensemble – this will be analyzed further in these terms. One can also consider a microcanonical ensemble in which the energy E of the system is fixed. This leads to a slightly different way of understanding Boltzmann entropy:

Definition 12 (Boltzmann Entropy at a Specific Energy)

The entropy of a macroscopic system with volume V and energy E, composed of N particles, is a logarithmic measure of the number of microstates that can realize this homogeneous macrostate assuming small cells of volume υ and low resolution of energy levels ε:

where the proportionality coefficient is Boltzmann’s constant . The counting of states within classical mechanics is arbitrary in the sense that it depends on the choice of the size of the elementary volume cell and the choice of the width of the energy intervals. However, due to the property of the logarithm function for large numbers, the parameters υ and ε only affect the entropy value in an additive way.

The calculation of this type of Boltzmann entropy for a part of the spatial volume is the same as before. Unfortunately, calculating the energy part is much more difficult. First, one must consider the partition of energy E into individual molecules. Secondly, the isotropic velocity distribution should be considered here without assuming the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Therefore, the counting of states should take place over a larger set than for equilibrium states, but for states that are isotropic in terms of velocity distribution.

Counting states using the partition function is rarely performed because it is cumbersome. An example is the calculations for the photon sphere of a black hole in the context of Hawking radiation [

15]. These calculations resulted in a result consistent with the equation of state of the photon gas, but compliance with Hawking radiation was obtained only for low energies.

While the Boltzmann entropy of the type was defined directly for equilibrium states, and the entropy of the type counted isotropic, but not necessarily equilibrium, states, one can also consider the entropy counting even non-isotropic states. This takes place in the extended phase space, i.e. in the configuration space, where the state of the microstate is described by one point in the space. Namely, there is another approach to measuring the complexity of a macrostate from previous ones. Instead of dividing the space of positions and pedos into cells and counting all possibilities, we can take as a measure the volume of configurational phase space that a given macrostate could realize. Unfortunately, energy resolution or cell size is also somewhat useful here.

Definition 13 (Boltzmann Entropy for a Phase Volume with the Gibbs Factor)

The entropy of a macroscopic system with a volume V, composed of N particles, is a logarithmic measure of the phase volume of all microstates of the system with energy in the range , which can realize a given macrostate with energy in this range:

where, in addition to the unit volume of the ω phase space configuration cell, the so-called Gibbs divisor . The role of the Gibbs divider is to reduce a significant value of the phase volume and is sometimes interpreted on the basis of the indistinguishability of identical particles. The dependence on the parameters ε and ω is additive.

The definition could be limited to the surface area of the hypersphere in the configurational phase space instead of the volume of the hypersphere shell. This would remove the parameter, but would formally require changing the volume of the unit cell to a unit area one dimension smaller.

In Boltzmann phase entropy, counting takes place over all microstates from the considered energy range. Therefore, both non-isotropic states in velocity and non-uniform states in position - in short, non-equilibrium states - are taken into account. Nevertheless, we will refer the entropy to the equilibrium state, since no non-equilibrium parameters are given for the state. The entropy of non-equilibrium macrostates can be found by dividing them into subsystems that can be treated as equilibrium, and then adding their entropies.

It is often postulated that the volume of a unit cell in phase space follows from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle . Then it should be , although it is usually simplified to , because units are more important than values (however, the problem of the presence of a divisor is decidable in quantum computations). However, if the size of the unit cell approached zero, the entropy would approach infinity.

The area of the constant energy phase hypersurface of dimension

can be calculated from the exact formula for the area of an odd-dimensional hypersphere of radius

r immersed in an even-dimensional space:

Taking into account that the radius of the sphere in the configurational momentum space can be related to the energy for material points

as follows, we obtain:

For further simplifications, Stirling’s asymptotic formula is standardly used:

Its application to further approximations leads to:

On this basis, the Boltzmann phase entropy of an ideal gas takes the form:

where the auxiliary dimensional constant

was chosen so that the volume of the phase cell of one particle is

. It is customary to simply omit the dimensional constants and the additive constant (but not in the so-called Sackur-Tetrode entropy formula). In any case, here the simplest part of the additive term has a coefficient of 5/2, and not 3/2 as before. Furthermore, the volume under the logarithm sign is divided by the number

N of particles. Generally, the presented result and the derivation method are consistent with the Tetrode method (see [

34]).

There is no temperature yet in the entropy formula obtained from the microcanonical decomposition. However, the general formalism of thermodynamics allows us to introduce such a temperature in a formal way:

The formula uses the phase Boltzmann entropy

, although the formula also applies to the entropy

, which, however, has not been calculated (at least here). In any case, using the above relation between temperature and energy, the entropy

can be given a form almost equivalent to the entropy

. The difference concerns the discussed factor dividing the volume and the less important term with factors 5/2 vs 3/2.

There is yet a slightly different approach to the statistical definition of entropy than Boltzmann’s original approach. Most often it refers to the canonical distribution and is attributed to Gibbs. Gibbs was probably the first to use the new formula for statistical entropy, but Boltzmann did not shy away from this formula either (see below). In addition, Shannon used this formula in information theory, as well as in ordinary mathematical statistics without a physical context.

Definition 14 (Gibbs or Gibbs–Shannon entropy)

The entropy of a macroscopic system whose microscopic energy realizations have probabilities is given by:

where the proportionality coefficient is the Boltzmann constant taken with a minus sign. The counting of states may be arbitrary in the sense of dividing them into micro-scale realizations of a macrostate and, consequently, assigning them a probability distribution.

Gibbs entropy usually applies to a canonical system in which the energy of the system is not strictly defined, but the temperature is specified. Therefore, we can only talk about the dependence of entropy on the average energy value. In a sense, entropy (like energy) in the canonical distribution also has a secondary, resulting role. Well, a more direct role is played by the Helmholtz free energy, which in thermodynamics is defined as follows:

Only from this energy can entropy be calculated. This will be an entropy equivalent to the Gibbs entropy, but due to a different way of obtaining it, we will treat it as a new definition:

Definition 15 (Entropy of type

F)

The entropy of the (canonical) system, expressed in terms of the Helmholtz free energy F, is with the opposite sign equal to the partial derivative of this free energy with respect to temperature:

In statistical terms, the free energy F is proportional with a sign opposite to the absolute temperature and to the logarithm of the statistical sum:

The statistical sum is the normalization coefficient of the unnormalized exponential probabilities of energy in the thermal (canonical) distribution:

Although this definition partially resembles the Boltzmann definition (e.g. instead of the number of states

there is a statistical sum

Z), it is more complex and specific (it includes temperature, which complicates the partial derivative). At least superficially, this entropy seems to be slightly different from the general idea of Boltzmann entropy (or even from Gibbs entropy):

but in a moment we will see that this additional last term contains only a part proportional to the number of particles

N and is often omitted in many types of entropy (does not apply to Sackur–Tetrode entropy). However, in this work it was decided to check the main part of this term, omitting the scale constants (Planck’s constant, the sizes of unit cells, the mass of particles, the logarithms of pi and e).

For an ideal gas, the statistical sum

Z can be calculated similarly to the calculation of entropy

. In the case of calculating the Boltzmann entropy

, we referred to arbitrary cells of the position and momentum space. Due to the discrete nature of the statistical sum, its calculation is usually performed as part of quantization on a cubic or cuboid box. The spatial boundary conditions on the box quantize momentum and energy, so the counting takes place only in terms of momentum quantum numbers - the volume of the box appears only indirectly in these relations. The result of this calculation is [

35]:

We see that this value is very similar to

when calculating the Boltzmann entropy of the type

. Indeed, after making standard approximations, the first principal term (

) of the entropy of a perfect gas of the

type will differ from the previous entropy only by a term proportional to the variable

N itself. However, the additional additive term of this entropy will be

and will reconcile these entropies:

where this time the auxiliary dimensional constants

and

satisfy the relation

.

In addition to the microcanonical and canonical (thermal) systems, there is also a large canonical system in which even the number of particles is not constant. Due to the numerous complications in defining entropy so far, the grand canonical system will not be considered here. Even more so, niche isobaric systems (isothermal or isenthalpic) will be omitted.

Note that the probability appearing in the Gibbs entropy is simply normalized to unity, and not to the number of particles

N, which may suggest that the Gibbs entropy differs from the Boltzmann-type entropy in the absence of this multiplicative factor

N. Indeed, this is reflected in the next version of Boltzmann entropy, in which there is a single-particle probability distribution function in the phase space [

36] normalized to

N (and not to unity):

Definition 16 (Boltzmann entropy of

H type)

In the state described in the phase space by the single-particle distribution function , the entropy of the H system (or simply the function, but not the Hamiltonian and not enthalpy) is defined by the following logarithm integral:

whereby the distribution function is normalized to a number of particles N, and the constant e in the denominator does not have any fundamental character.

Note that the divisor e after taking into account the normalization condition of the distribution function leads to an additive entropy term of without the factors or . However, perhaps this divisor actually corrects the target entropy value.

Moreover, it is often assumed that the quantity defined above (or slightly modified) is not entropy, but taken with the opposite sign, the so-called H function. However, in the light of the various definitions cited in this work, there is no point in considering this quantity as something different from entropy. All the more so because Boltzmann formulated a theorem regarding this function, which was supposed to reflect the second law of thermodynamics. To formulate this theorem, the Boltzmann kinetic equation and the assumption of molecular chaos are also needed.

The Boltzmann kinetic equation for the one-particle distribution function

of the initial state

N postulates that the complete derivative of the distribution function is equal to the partial derivative taking into account two-particle collisions:

where

is the external acceleration field – e.g., the gravitational field.

The assumption of molecular chaos (

Stosszahlansatz), in simple terms, consists in assuming that two-particle collisions are factored using the one-particle distribution function as follows:

where

is the differential cross section related to the velocity angles satisfying the relation

. The kinematic-geometric idea of the molecular chaos assumption is quite simple (it is a simplification), but the mathematical formula itself is already complex - we will not go into details here. It turned out that the assumption

Stosszahlansatz together with the evolution equation (

32) was enough for Boltzmann, in a sense, to derive the second law of thermodynamics:

Theorem 1 (

H Boltzmann)

If the single-particle distribution function satisfies the "Stosszahlansatz" assumption regarding the Boltzmann evolution equation (32), then the entropy of the H Boltzmann type is nondecreasing time function:

The proof of Boltzmann’s theorem, in a notation analogous to the one adopted here, can be found in the textbooks [

36,

37].

Although Boltzmann’s theorem is a true mathematical theorem, it is unfortunately not (and cannot be) a derivation of the second law of thermodynamics. The thesis of every theorem follows from an assumption, and the assumption of molecular chaos (Stosszahlansatz) is not entirely true. This assumption, in some strange way, introduces irreversibility and asymmetries of time evolution into the macroscopic system, when the remaining equations of physics do not contain this element of time asymmetry. This issue has even been called the irreversibility problem or even Loschmidt’s irreversibility paradox.

Typically, in the context of the irreversibility problem, it is claimed (somewhat incorrectly) that all the fundamental equations of physics are time-symmetric. However, this does not in any way apply to equations involving resistances to motion, including friction. It is difficult to explain why the aspect of resistance to motion is so neglected in physics. Ignorance of resistance to movement is imputed to Aristotle, when in fact it is exactly the opposite and Aristotle described the proportion of movement that included resistance. This proportion can even be interpreted as consistent with Newtonian dynamics according to the some corresponding correspondence principle [

38]. The time asymmetry of Aristotle’s equation (proportion) of dynamics was noticed by the American physicist Leonard Susskind (see [

38]). Another example of an equation lacking time symmetry is the Langevin equation, which relates to friction in statistical mechanics.

In the context of Boltzmann and statistical physics, it is impossible not to mention the very fundamental ergodic hypothesis, which serves as a basic assumption and postulate. The ergodic hypothesis assumes that the average value of a physical quantity (random variable) based on a statistical distribution is realized over time, i.e. it tends to the average time value of this physical quantity (random variable). Let us assume that this pursuit simply boils down to the postulate of equality of these two types of averages (without precisely defining the period

of this averaging):

If the distribution is stationary (does not evolve over time), then of course

can and should tend to infinity

. And this is indeed the standard assumption - however, averaging over the future or past or the entire timeline should not differ. However, for non-stationary (time-dependent) distributions, averaging over an infinite time seems to be pointless. In such situations, one could therefore consider "local" averages over time. Then the forward time averaging used above could prefer to evolve forward in time relative to the symmetric averaging time interval. Unfortunately, ergodicity is limited to stationary situations, even where it supposedly does not always occur.

As you can see, the physical status of the ergodic hypothesis is not entirely clear. While the left side of the considered equalities has a clear statistical sense, it is not entirely clear how to determine the right side, which requires knowledge of the time evolution of the system under consideration. Namely, what Liouville equation should be used to describe this evolution in time: the Boltzmann equation or some other equivalent? In other words, it is not clear whether in practice the ergodic hypothesis is a working definition of time averages (right-hand side), or whether it is a postulate or principle of physics that can be confirmed or disproved theoretically or experimentally. The literature states as an indisputable fact that given known systems are ergodic or not ergodic. Nevertheless, it seems that in this matter we should be more humble regarding the physical status of the ergodic hypothesis and treat it as an important methodological tool. In any case, it seems that the ergodic hypothesis should be independent of the Botzmann equation with molecular chaos. Therefore, the problem of irreversibility cannot be solved merely by questioning the ergodic hypothesis. Erodicity should not be confused with weak erdodicity, which is based on the Boltzmann equation as a simplifying assumption.

Regardless of the existence of resistance to motion, the criticisms of the molecular chaos assumption, the problems with the status of ergodicity, or Boltzmann’s generally enormous contribution, it seems that the essence of the second law of thermodynamics in a statistical approach can be contained in the newer fluctuation theorem and its corollary, the second-law inequality.

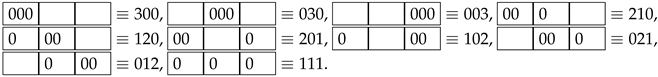

. In the graphic diagram, the balls are marked with zero numbers. The considered macrostate is represented by three microstates (), which can be presented in graphical diagrams containing ball numbers:

. In the graphic diagram, the balls are marked with zero numbers. The considered macrostate is represented by three microstates (), which can be presented in graphical diagrams containing ball numbers:  ,

,  ,

,  . Of course, the order of the two balls in a given cell does not matter.

. Of course, the order of the two balls in a given cell does not matter.