Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

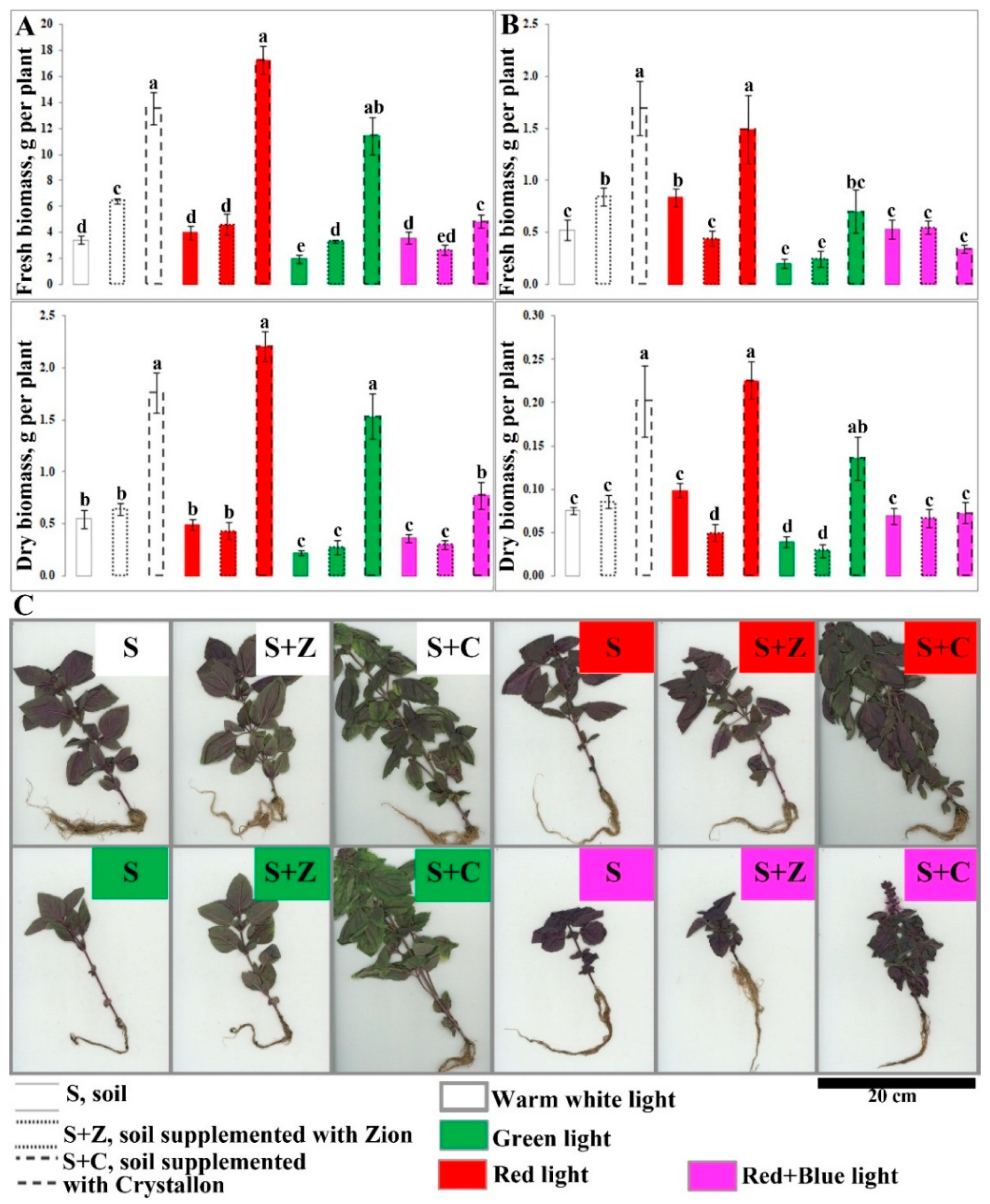

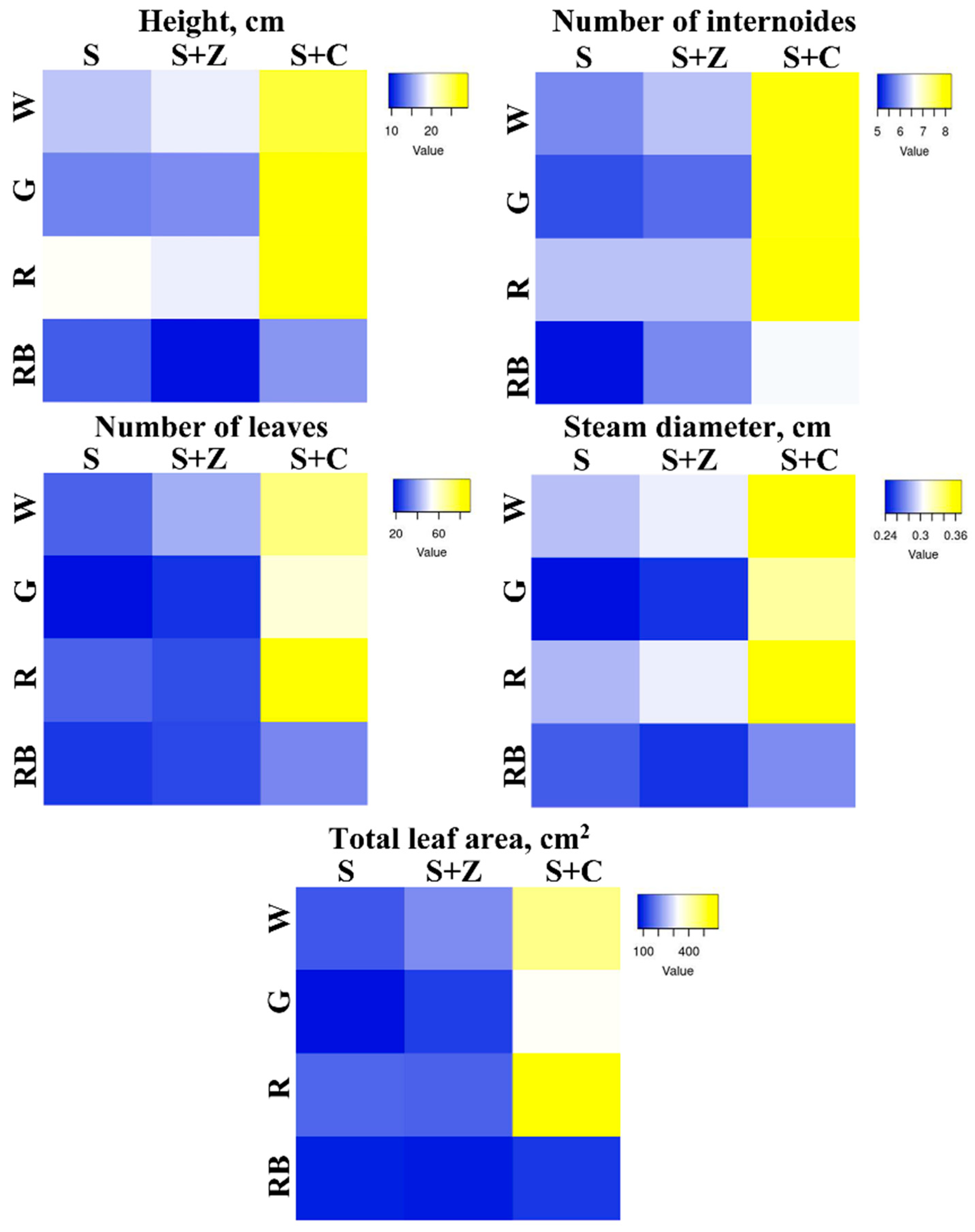

2.1. The Effects of Artificial Light and Soil Composition on the Growth of O. basilicum Plants

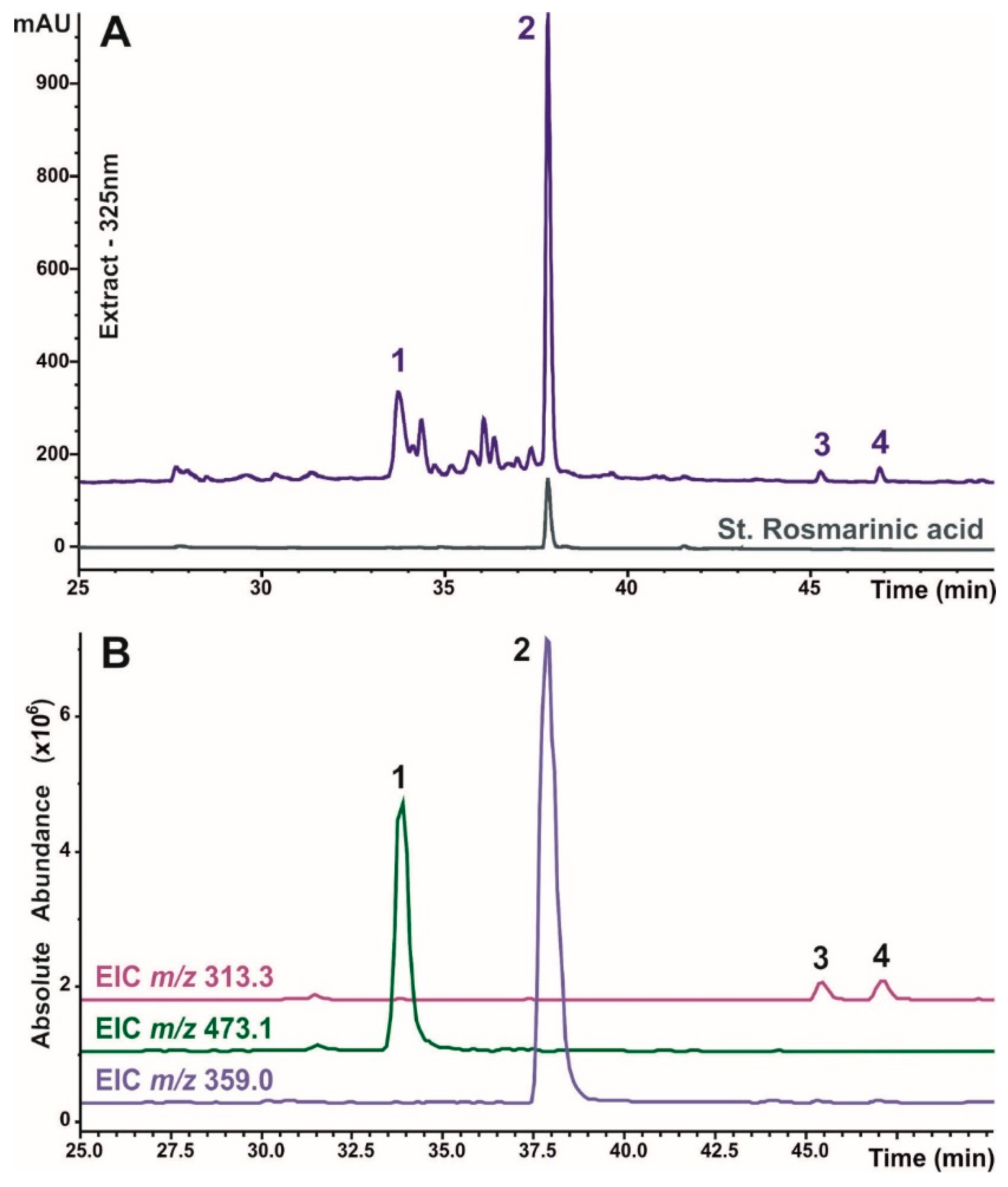

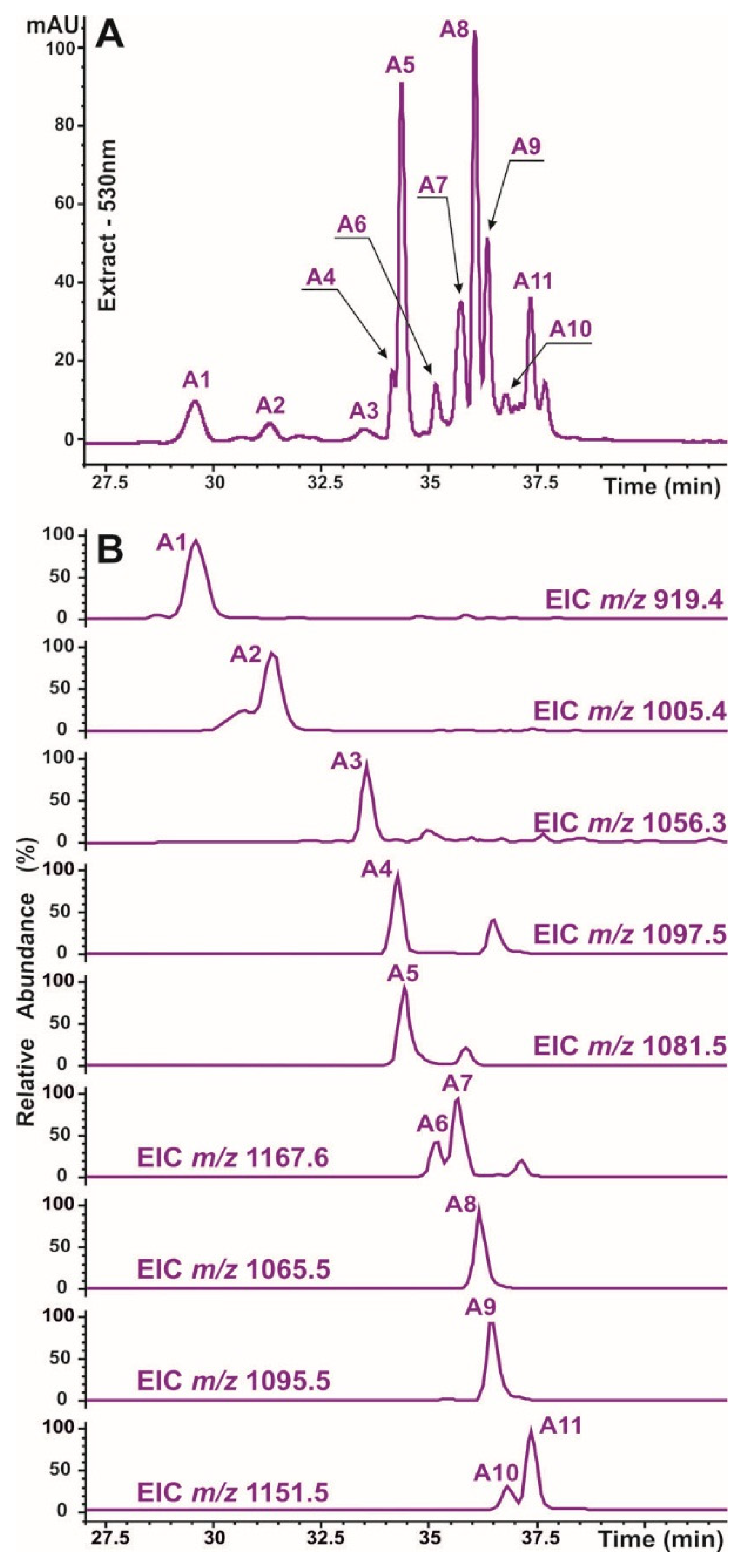

2.2. Identification of Caffeic Acid Derivatives in O. basilicum Plants

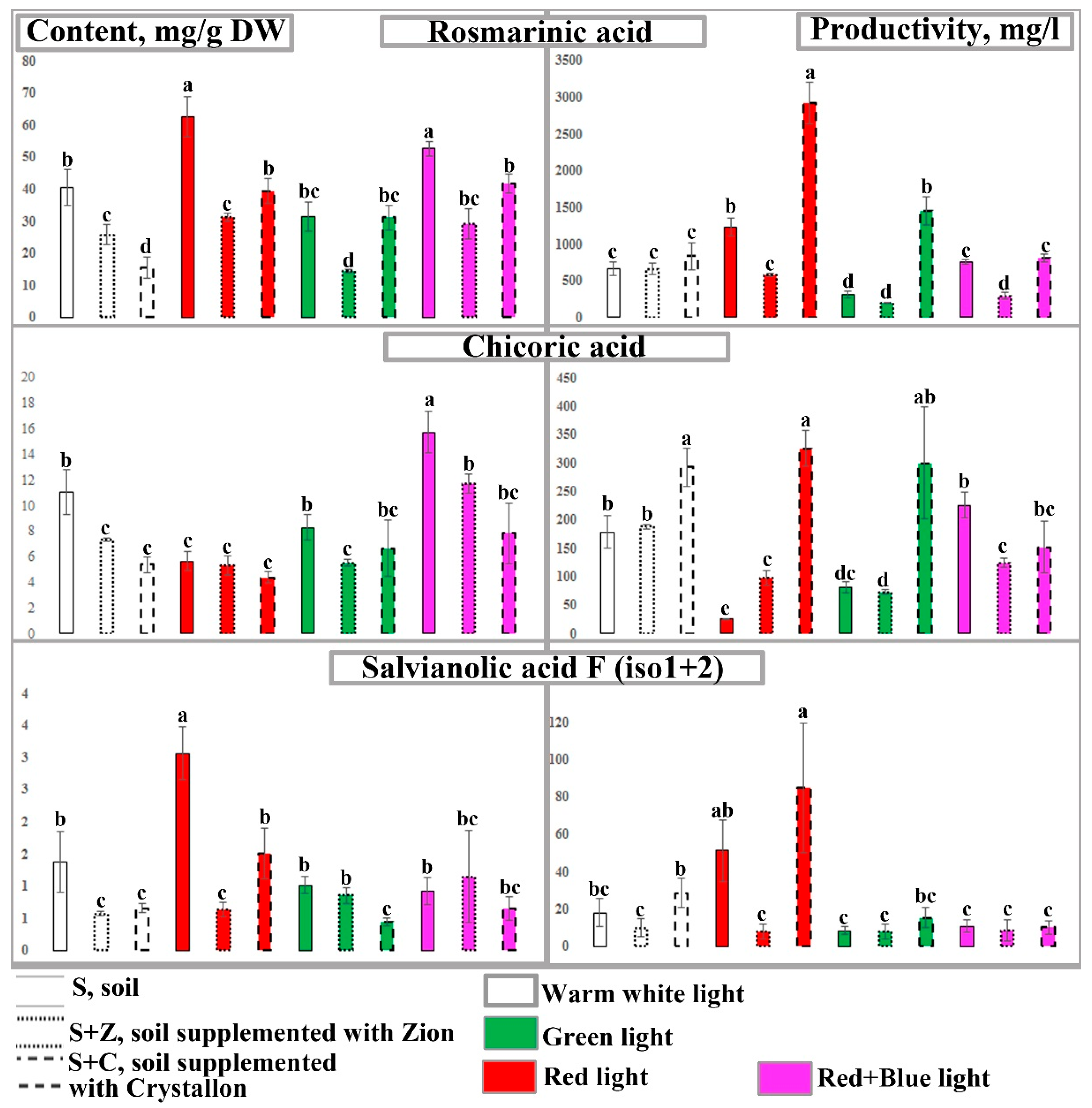

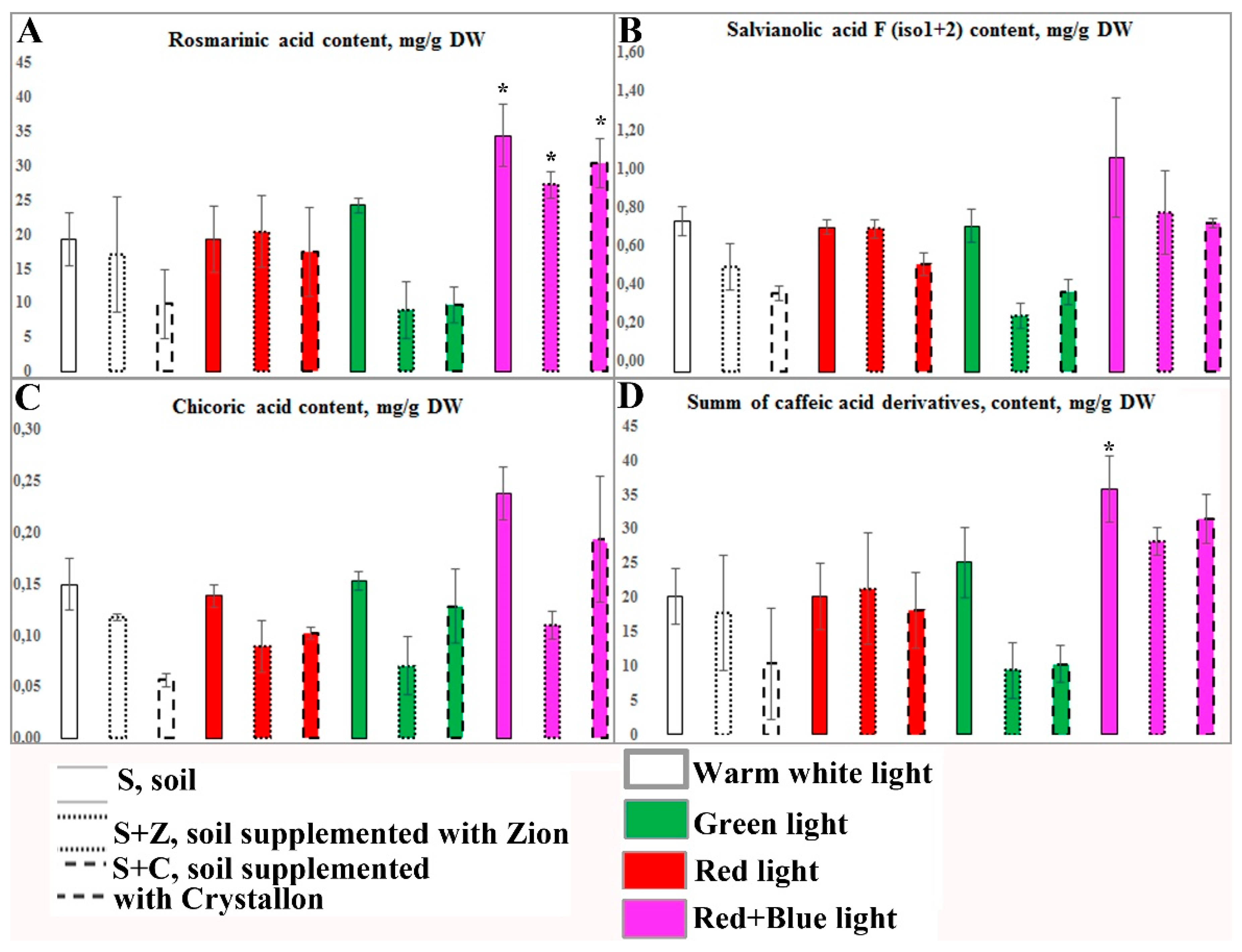

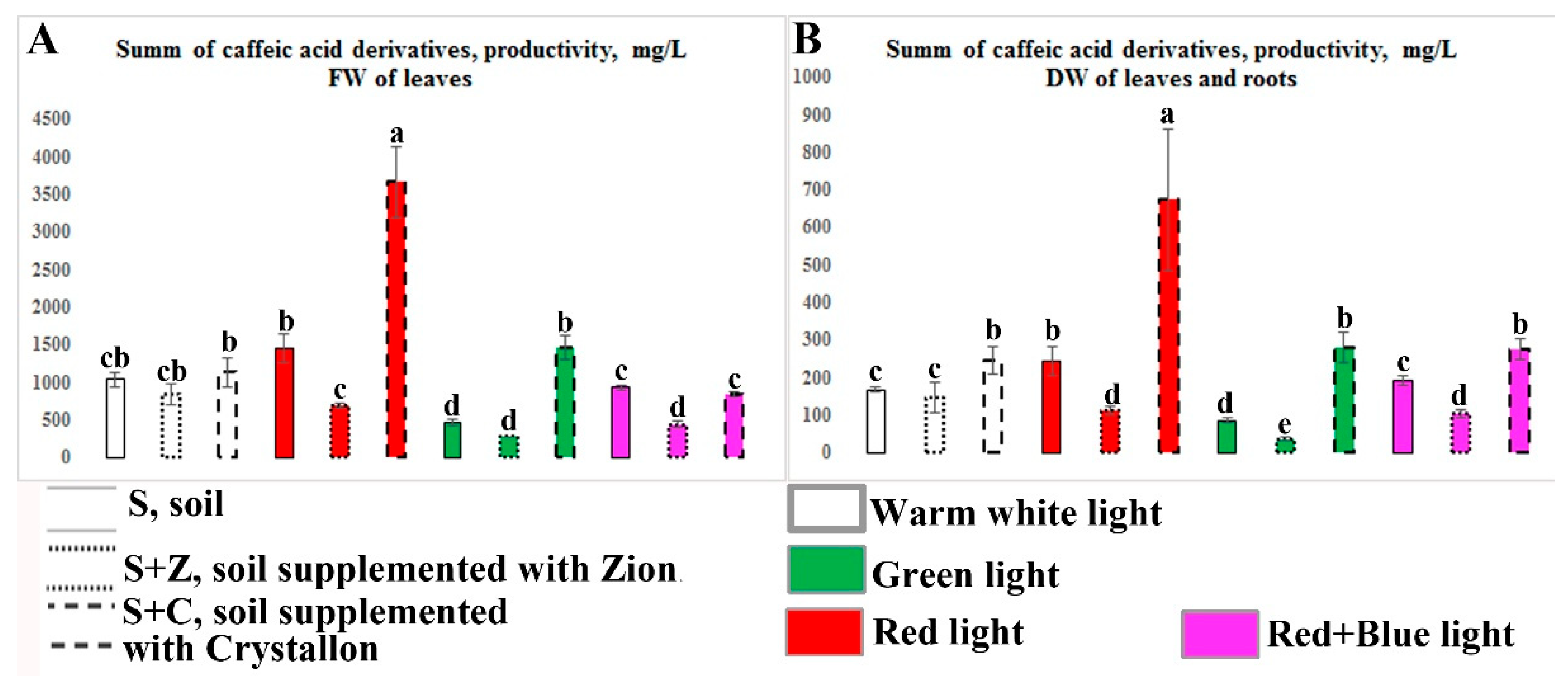

2.3. Content and Productivity of Caffeic Acid Derivatives in O. basilicum Plants

| No | Rt, min | Compound assignment | UV max, nm | Molecular Formula | ESI-MS(MS2) data | Ref. | |||

| Ion composition | HRMS, m/z values | error, mDa | MS2, main diagnostic ions, m/z | ||||||

| Caffeic acid derivatives | |||||||||

| 1 | 33.7 | Chicoric acid | 326 | C22H18O12 | [2M-H]- [M-H]- |

947.1500 473.0721 |

2.4 0.5 |

473, 311, 293 311, 293, 219, 179, 149 |

1 |

| 2 | 37.7 | Rosmarinic acid | 230, 327 | C18H16O8 | [2M-H]- [M-H]- |

719.1581 359.0758 |

3.7 1.4 |

359 197, 179, 161 |

1 |

| 3 | 45.3 | Salvianolic acid F (isomer 1) | 248, 339 | C17H14O6 | [M-H]- | 313.0719 | 0.1 | 161 | 1 |

| 4 | 46.9 | Salvianolic acid F (isomer 2) | 252, 339 | C17H14O6 | [M+H]+ [M-H]- |

315.0884 313.0710 |

2.1 0.8 |

nd 269, 161 |

1 |

| Anthocyanins | |||||||||

| A1 | 29.6 | Cyanidine-3-(Cou-diHex)-5-Hex | 225, 281, 520 | C42H47O23 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

919.2512 917.2335 935.2423 |

0.9 2.2 4 |

757, 595, 449, 287 755, 593, 447, 285 773, 755, 611, 447, 285 |

2 |

| A2 | 31.3 | Cyanidine-3-(Mal-Cou-diHex)-5-Hex | 226, 283, 523 | C45H49O26 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1005.2495 1003.2339 1021.2432 |

1.2 2.2 3.5 |

843, 681, 449, 287 959, 797 977, 815, 797 |

2 |

| A3 | 33.5 | Cyanidine-3-(Caf-hydroxybensoyl-diHex)-5-Hex | 221, 287, 523 | C49H51O26 | M+ [M-2H]- |

1055.2623 1053.2537 |

4.0 1.9 |

893, 449, 287 891 |

3 |

| A4 | 34.1 | Cyanidine-3-(Caf-Caf-diHex)-5-Hex | 222, 286, 528 | C51H53O27 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1097.2802 1095.2632 1113.2689 |

3.3 0.9 4 |

935, 773, 611, 449 933, 771, 609, 447 1095, 951, 933 |

2 |

| A5 | 34.3 | Cyanidine-3-(Caf-Cou-diHex)-5-Hex | 228, 283, 528 | C51H53O26 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1081.2836 1079.2643 1097.2753 |

1.6 3.1 2.7 |

919, 757, 595, 449 917, 755 1079, 935, 917, 465 |

1, 2 |

| A6 | 35.2 | Cyanidine-3-(Caf-Cou-diHex)-5-Mal-Hex | 225, 295, 529 | C54H55O29 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1167.2850 1165.2706 1183.2763 |

2.6 2.8 2.1 |

1081, 1005, 919, 535, 449 1121 1139, 1121 |

1, 2 |

| A7 | 35.7 | Cyanidine-3-(Mal-Caf-Cou-diHex)-5-Hex | 226, 285, 528 | C54H55O29 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1167.2840 1165.2666 1183.2773 |

1.6 1.2 1.1 |

1005, 449 1121 1139 |

1, 2 |

| A8 | 36.0 | Cyanidine-3-(diCou-diHex)-5-Hex | 229, 283, 529 | C51H53O25 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1065.2882 1063.2722 1081.2828 |

1.2 0.3 0.3 |

903, 757, 595, 449 901, 615, 447 919, 901, 465 |

1 |

| A9 | 36.3 | Cyanidine-3-(Caf-Fer-diHex)-5-Hex | 226, 292, 530 | C52H55O26 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1095.3008 1093.2787 1111.2905 |

3.2 4.4 3.1 |

933, 757, 595, 449 931, 755, 593, 447 949, 931 |

2 |

| A10 | 36.8 | Cyanidine-3-(diCou-diHex)-5-Mal-Hex | 224, 288, 530 | C54H55O28 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1151.2917 1149.2715 1167.2809 |

4.3 1.4 2.5 |

1065, 989, 903, 535, 449 1105, 943, 901 1123 |

1, 2 |

| A11 | 37.4 | Cyanidine-3-(Mal-diCou-diHex)-5-Hex | 228, 284, 529 | C54H55O28 | M+ [M-2H]- [M-2H+H2O]- |

1151.2915 1149.2702 1167.2829 |

4.1 2.7 0.6 |

989, 945, 843, 681, 449 1105, 943 1123 |

1, 2 |

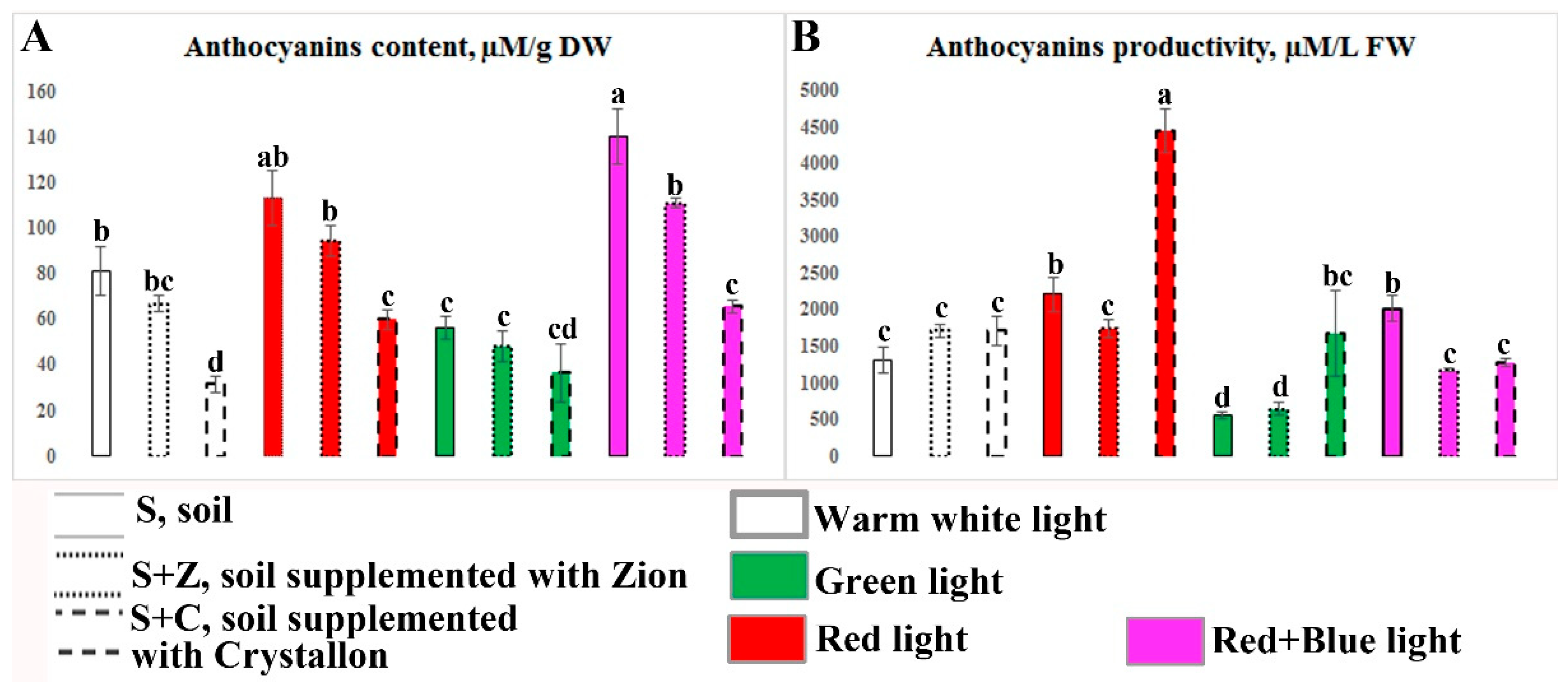

3.4. Content and Productivity of Anthocyanins in O. basilicum Plants

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials, Growth Conditions and Experimental Design

4.2. Measurements of Morphometric Characteristics

4.3. Anthocyanin and Caffeic Acid Derivative Analysis

Chemicals

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orsini, F.; Pennisi, G.; Gianquinto, F.Z.G. Sustainable use of resources in plant factories with artificial lighting (PFALs). Europ J Hortic Sci 2020, 85, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makri, O.; Kintzios, S. Ocimum sp. (Basil): Botany, Cultivation, Pharmaceutical Properties, and Biotechnology. J Herb Spices Med P 2008, 13, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, K.S.; Arora, S.; Shri, R. Role of Ocimum basilicum L. in prevention of ischemia and reperfusion-induced cerebral damage, and motor dysfunctions in mice brain. J of Ethnopharmac 2011, 137, 1360–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, T.; Rasul, A.; Sarfraz, A.; Sarfraz, I.; Hussain, G.; Anwar, H.; Riaz, A.; Liu, S.; Wei, W.; Li, J.; Li, X. Salvianolic acid A & B: potential cytotoxic polyphenols in battle against cancer via targeting multiple signaling pathways. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15, 2256–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinsi, B.; Morgutti, S.; Negrini, N.; Faoro, F.; Espen, L. Insight into composition of bioactive phenolic compounds in leaves and flowers of green and purple Basil. Plants 2019, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xie, J.; Sun, M.; Xiong, S.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Lin, L. Plant-derived caffeic acid and its derivatives: an overview of their NMR data and biosynthetic pathways. Molecules 2024, 29, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Bamunuarachchi, N.I.; Tabassum, N.; Kim, Y.-M. Caffeic acid and its derivatives: antimicrobial drugs toward microbial pathogens. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 2979–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Scagel, C.F. Chicoric acid found in basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) leaves. Food Chem 2009, 115, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; De Luca, L.; Aiello, A.; Pagano, R.; Di Pierro, P.; Pizzolongo, F.; Masi, P. Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) leaves as a source of bioactive compounds. Foods 2022, 11, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trócsányi, E.; György, Z.; Zámboriné-Németh, É. New insights into rosmarinic acid biosynthesis based on molecular studies. Cur Plant Biol 2020, 23, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgakov, V.P.; Vereshchagina, Y.V.; Veremeichik, G.N. Anticancer polyphenols from cultured plant cells: production and new bioengineering strategies. CMC 2018, 25, 4671–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.-S.; Liu, A. Light signaling induces anthocyanin biosynthesis via AN3 mediated COP1 expression. Plant Signal Behav 2015, 10, e1001223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taulavuori, K.; Pyysalo, A.; Taulavuori, E.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R. Responses of phenolic acid and flavonoid synthesis to blue and blue-violet light depends on plant species. Environ Exp Bot 2018, 150, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Su, M.; Li, H.; Zeng, B.; Chang, Q.; Lai, Z. Effects of supplemental lighting with different light qualities on growth and secondary metabolite content of Anoectochilus roxburghii. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaye Noroozlo, Y.; Souri, M.K.; Delshad, M. Effects of soil application of amino acids, ammonium, and nitrate on nutrient accumulation and growth characteristics of sweet basil. Com Soil Sci Plant Anal 2019, 50, 2864–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.O.; Kim, H.J.; Gil Nam, H. leaf senescence. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2007, 58, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ma, X.; Gao, X.; Wu, W.; Zhou, B. Light induced regulation pathway of anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants. IJMS 2021, 22, 11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasch, J.; Appelbaum, S.; Palm, H.W.; Knaus, U. Growth of basil (Ocimum basilicum) in aeroponics, DRF, and raft systems with effluents of african catfish (Clarias gariepinus) in decoupled aquaponics (s.s.). AgriEngineering 2021, 3, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fussy, A.; Papenbrock, J. An overview of soil and soilless cultivation techniques—chances, challenges and the neglected question of sustainability. Plants 2022, 11, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, B.; Silvestre, W.P.; Pauletti, G.F. Preliminary study on the effect of artificial lighting on the production of basil, mustard, and red cabbage seedlings. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammock, H.A.; Kopsell, D.A.; Sams, C.E. Supplementary blue and red LED narrowband wavelengths improve biomass yield and nutrient uptake in hydroponically grown basil. horts 2020, 55, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiga, T.; Shoji, K.; Shimada, H.; Hashida, S.; Goto, F.; Yoshihara, T. Effect of light quality on rosmarinic acid content and antioxidant activity of sweet basil, Ocimum basilicum L. Plant Biotechnol 2009, 26, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, B.; Kowalski, A. The growth, photosynthetic parameters and nitrogen status of basil, coriander and oregano grown under different led light spectra. Acta Sci Pol Hortorum Cultus 2021, 20(2), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Kinoshita, T.; Takemiya, A.; Doi, M.; Shimazaki, K. Leaf positioning of Arabidopsis in response to blue light. Mol Plant 2008, 1, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones-Baumgardt, C.; Llewellyn, D.; Zheng, Y. Different microgreen genotypes have unique growth and yield responses to intensity of supplemental PAR from light-emitting diodes during winter greenhouse production in southern ontario, Canada. horts 2020, 55, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbert, J.M.; Riewe, D.; Schulz, H.; Krähmer, A. Facing energy limitations – approaches to increase basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) growth and quality by different increasing light intensities emitted by a broadband LED light spectrum (400-780 nm). Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1055352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veremeichik, G.N.; Grigorchuk, V.P.; Makhazen, D.S.; Subbotin, E.P.; Kholin, A.S.; Subbotina, N.I.; Bulgakov, D.V.; Kulchin, Y.N.; Bulgakov, V.P. High production of flavonols and anthocyanins in Eruca sativa (Mill) Thell plants at high artificial LED light intensities. Food Chem 2023, 408, 135216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedoreyev, S.A.; Veselova, M.V.; Krivoschekova, O.E.; Mischenko, N.P.; Denisenko, V.A.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Glazunov, V.P.; Bulgakov, V.P.; Tchernoded, G.K.; Zhuravlev, Y.N. Caffeic acid metabolites from Eritrichium sericeum cell cultures. Planta med 2005, 71, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrine, D.; Greco, T.M.; Muhammad, B.; Wu, B.-S.; Zhao, X.; Lefsrud, M. Color-specific recovery to extreme high-light stress in plants. Life 2021, 11, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, N.; Tripathi, R.; Wu, B.-S.; MacPherson, S.; Singh, J.; Lefsrud, M. The effect of light quality on plant physiology, photosynthetic, and stress response in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Delden, S.H.; SharathKumar, M.; Butturini, M.; Graamans, L.J.A.; Heuvelink, E.; Kacira, M.; Kaiser, E.; Klamer, R.S.; Klerkx, L.; Kootstra, G.; Loeber, A.; Schouten, R.E.; Stanghellini, C.; Van Ieperen, W.; Verdonk, J.C.; Vialet-Chabrand, S.; Woltering, E.J.; Van De Zedde, R.; Zhang, Y.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Current status and future challenges in implementing and upscaling vertical farming systems. Nat Food 2021, 2, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deineka, V.I.; Kul’chenko, Ya.Yu.; Blinova, I.P.; Chulkov, A.N.; Deineka, L. A Anthocyanins of basil leaves: determination and preparation of dried encapsulated forms. Rus J Bioorg Chem 2019, 45, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saga Kaboré, D.; Héma, A.; Kabré, E.; Bazié, R.; Sakira, A.K.; Koala, M.; Koussao Somé, P.-A.; Palé, E.; Issa Somé, T.; Duez, P. Identification of five acylated anthocyanins and determination of antioxidant contents of total extracts of a purple-fleshed Ipomoea batatas L. variety grown in Burkina Faso. IRJPAC 2021, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.C.; Bekhradi, F.; Ferreres, F.; Jordán, M.J.; Delshad, M.; Gil, M.I. Effect of water stress and storage time on anthocyanins and other phenolics of different genotypes of fresh sweet basil. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 9223–9231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Ovando, A.; Pacheco-Hernández, Ma.D.L.; Páez-Hernández, Ma.E.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Galán-Vidal, C.A. Chemical studies of anthocyanins: A review. Food Chem 2009, 113, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczyńska, M.; Soldatov, V.; Wasąg, H. Effect of different variants of the ion exchange substrate on vegetation of Dactylis glomerata L on the degraded soil. Proc ECOpole 2010, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chomczyńska, M.; Soldatov, V.; Wasąg, H.; Turski, M. Effect of ion exchange substrate on grass root development and cohesion of sandy soil. Int Agrophysics 2016, 30, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczyńska, M.; Zdeb, M. The effect of Z-ion zeolite substrate on growth of Zea mays L. as energy crop growing on marginal soil. J Ecol Eng 2019, 20, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovene, C.; Orsini, F.; Bosi, S.; Sanoubar, R.; Bregola, V.; Dinelli, G.; Gianquinto, G. Optimal red:blue ratio in led lighting for nutraceutical indoor horticulture. Sci Horticult 2015, 193, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobiuc, A.; Vasilache, V.; Oroian, M.; Stoleru, T.; Burducea, M.; Pintilie, O.; Zamfirache, M.-M. Blue and red LED illumination improves growth and bioactive compounds contents in acyanic and cyanic Ocimum basilicum L. microgreens. Molecules 2017, 22, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutimanukul, P.; Wanichananan, P.; Janta, S.; Toojinda, T.; Darwell, C.T.; Mosaleeyanon, K. The influence of different light spectra on physiological responses, antioxidant capacity and chemical compositions in two holy basil cultivars. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, H.; Niu, G.; Gu, M.; Masabni, J. Morphological and physiological responses in basil and brassica species to different proportions of red, blue, and green wavelengths in indoor vertical farming. J Amer Soc Hort Sci 2020, 145, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäenpä, M.; Mofikoya, A.; Abd El-Raheem, A.M.; Riikonen, J.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R.; Holopainen, J.K. Alteration in light spectra causes opposite responses in volatile phenylpropanoids and terpenoids compared with phenolic acids in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) leaves. J Agric Food Chem 2022, 70, 12287–12296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Vasiliev, M.; Alameh, K. LED illumination spectrum manipulation for increasing the yield of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). Plants 2021, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.-E.; Moon, J.-K.; Lee, C.H. Polyphenol content and essential oil composition of sweet basil cultured in a plant factory with light-emitting diodes. HST 2020, 38, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Author 1, A.B. (University, City, State, Country); Author 2, C. (Institute, City, State, Country). Personal communication, 2012.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).