1. Introduction

Active packaging has gained significant interest in the context of increasing demands for food safety and quality and environmental concerns related to traditional plastic packaging. Unlike traditional methods that directly add active ingredients, such as antioxidants and antimicrobials, to food, active packaging strategies are based on the incorporation of these substances into the packaging material. This method extends the effectiveness of the active ingredients within the packaging system and addresses sustainability concerns [

1]. Despite these advancements, achieving effective controlled release of active additives from the packaging materials remains challenging, highlighting the growing interest in microencapsulation technologies [

2]. In addition, shifting towards green packaging solutions has become a priority, sparking intense research into biodegradable polymer materials [

3,

4].

Microencapsulation typically involves enveloping the potentially volatile active chemicals in a continuous film of tiny droplets or particles, using natural or synthetic polymers as the encapsulating material. These particles, known as microcapsules, can significantly enhance active compounds' stability, solubility, and release dynamics [

5]. Cyclodextrins have shown as adequate encapsulating materials by their globular structure permitting to host specific molecules by the formation of covalent bonds [

6,

7]. Among them, β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) is particularly notable due to its moderate molecular cavity and cost-effective production. β-CD microencapsulation shows a promising strategy for enhancing different compounds' stability, solubility, and release characteristics [

6,

7]. These studies demonstrated the successful encapsulation of various molecules within β-CD frameworks, improving stability and reducing volatility of the active chemicals. The formation of inclusion complexes between β-CD and specific molecules through host-guest interactions enhances the encapsulated compounds' stability and solubility [

8]. β-CD microencapsulation has been also proposed to offer controlled and sustained release profiles of specific compounds [

8]. Overall, the use of β-CD in microencapsulation holds significant potential for a wide range of applications. It is crucial not only for extending the shelf life of volatile compounds and enhancing the efficacy of flavour agents, but also for increasing their antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, ensuring controlled or sustained release from the inclusion complex [

9,

10].

Allyl isothiocyanate (AITC), a compound known for its strong antimicrobial performance, is extensively used as a natural preservative in biomedical applications [

11]. However, high volatility and rapid degradation limit its use in active packaging systems. By encapsulating AITC in β-CD, these limitations can be mitigated, enhancing the antimicrobial efficacy of the packaging material and changing the mechanical and thermal stability of the resulting active materials, making them effective for antimicrobial packaging [

12,

13].

Polylactic acid (PLA) possesses excellent properties such as bio-absorbability, biodegradability, mechanical strength, and transparency, which are essential for packaging applications [

14]. The addition of active compounds to PLA matrices amplify its functionalities, offering effective solutions for reducing post-harvest losses and improving environmental sustainability [

15]. Research has shown that incorporating β-CD complexes into PLA can influence the film's physical properties, antimicrobial activity, and disintegration under composting conditions [

16,

17]. For instance, it has been proved that β-CD inclusion complexes can improve the controlled release properties of active agents in biodegradable films, enhancing food safety and extending shelf life [

18]. Shi et al. (2022) also observed an antimicrobial effect on releasing oregano essential oil from the electrospun-based PLA nanofibers [

19].

Previous studies explored the use of AITC-β-CD complexes in different materials, particularly on PLA films, for preservative purposes [

20]. However, given the limited research until now on the compostability of these active films, this study aims to evaluate how the β-CD:AITC inclusion complexes affect the physical, chemical, and biological properties of PLA films when they disintegrate under composting conditions. This study also aims to determine the potential uses of these films as biodegradable antimicrobial material, while developing sustainable packaging solutions that meet environmental and functional standards. These findings have broad implications for the packaging industry, offering innovative approaches to managing waste and enhancing food preservation.

2. Results

2.1. Characterisation of PLA Films

2.1.1. Field Emission Scanning Electronic Microscopy (FESEM)

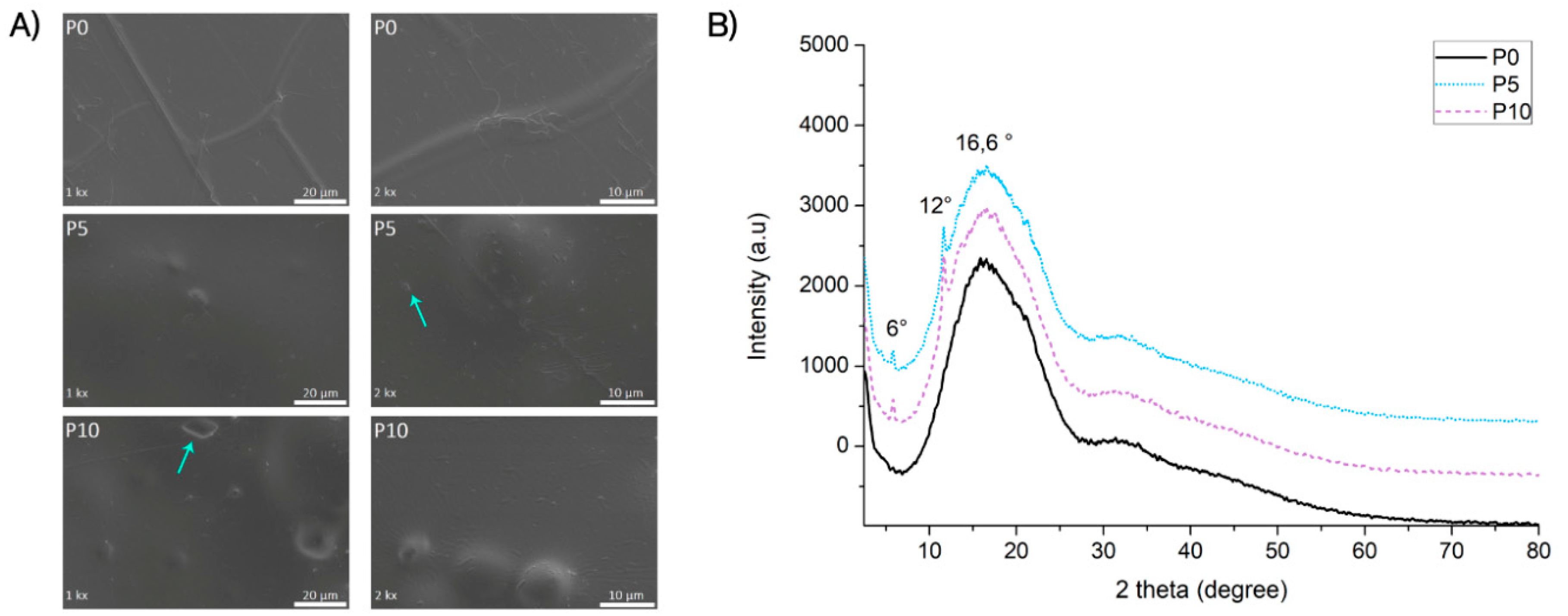

Figure 1A shows the surface morphological analysis of the PLA films with and without the addition of the inclusion complexes. P0 films showed smooth surface, while active films exhibited structures with different morphologies on their surface. Indeed, structures with bubbles were evident on the surface of P5 and P10 films. Furthermore, small structures like flakes were also identified on these materials, as indicated with arrows in

Figure 1. Previous studies on extruded films loaded with inclusion complexes also identified bubbles-type structure in the material surface, which were associated to the agglomeration of fillers due to the low miscibility between all components in these blends [

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, the agglomeration is not apparent on the polymer surface, but it could be embedded in the matrix, producing some relief on the surface. This observation is related to the fact that the flake-like structures (pointed with arrows) on the surface of active films were similar to those observed in a previous study for the original inclusion complexes [

25].

2.1.2. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

The crystalline structure of films was studied by XRD analysis (

Figure 1B). XRD patterns showed a broad band at 2θ = 16.6° for P0, which evidenced a polymer with an amorphous state [

26,

27]. On the other hand, in P5 and P10 films the broad peak corresponding to PLA was observed, but also characteristic crystallinity peaks at 11.6° and 5.8° were observed, corresponding to the crystalline structure of inclusion complexes. This change in the polymer structure is related to the host:guest interaction evidencing the AITC complexation [

25]. This result evidenced the presence and distribution of the inclusion complexes into the polymeric matrix, which was also observed in the FESEM analysis. Therefore, it could be concluded that the extrusion process did not affect the original structure of inclusion complexes, which confirmed the thermal protection of the AITC by the β-CD after the extrusion process.

2.1.3. Thermal Properties

The thermal parameters obtained by using TGA and DSC are summarised in

Table 1. All films exhibited a one-step thermal degradation with maximum rate around 366 °C (T

deg), indicating the occurrence of bond cleavage on the backbone to produce cyclic oligomers, lactide, and carbon monoxide as products [

19]. It was evidenced that inclusion complexes were not able to modify the thermal stability of PLA.

On the other hand, glass transition temperature (T

g), cold crystallization temperature (T

cc), melting temperature (T

m), and enthalpies associated with the first-order transitions were obtained from DSC thermograms of different films. Results obtained for the P0 film were similar to those reported in other studies [

28,

29,

30]. The presence of inclusion complexes did not modify the values of T

g, but higher T

cc and T

m values were registered for P5 and P10. This fact was associated with the thermal stability of the inclusion complexes that withstand temperatures up to 300 °C [

25], which could slightly improve the thermal behaviour of the active films. Moreover, a decrease in cold crystallization and melting enthalpies (∆H

cc and ∆H

m) in active films was observed. The reduction in ∆H

cc could be related to a high free volume in the amorphous zone due to the presence of inclusion complexes, which generated higher chain mobility in the materials. Instead, the lower value in ∆H

m was related to a decrease in crystallinity due to the low miscibility of all components in the inclusion complexes. Other authors have also reported similar results [

21,

28,

31]. Finally, the PLA crystallinity was not modified, being lower than 5% for all samples, which agrees with the XRD results.

2.1.4. Colour Measurements

The visual aspect and the colour parameters (L*, a*, and b* and the colour difference ∆E) for all materials are shown in

Table 1. A high value of L*, a value of a* close to 0 and a positive value of b* were found for P0, which means the film was luminous with a greenish tonality. Other researchers have also obtained similar colour parameters for PLA films [

21,

30]. The incorporation of inclusion complexes β-CD:AITC into PLA affected significantly the colour parameters of films. For instance, the highest concentration of complexes decreased L* and a* values, but b* increased to 2.57 ± 0.02 and 2.92 ± 0.09 for P5 and P10, respectively. Therefore, P5 and P10 materials were darker, with a higher yellow and green tone than P0. Nevertheless, active films showed ∆E value lower than 5 and likewise, perceptible colour changes were not visible to the human eye [

32].

2.1.5. Mechanical Properties

The tensile parameters of films are shown in

Table 1. Values of the elastic modulus, tensile strength and elongation at the break of P0 were similar to PLA films reported in other works [

28,

33]. However, the incorporation of inclusion complexes significantly decreased all tensile parameters, obtaining more rigid and brittle films compared to P0. This behaviour has also been reported in active PLA films loaded with inclusion complexes obtained from cyclodextrin and different active compounds [

28,

31,

34]. In this study, the low compatibility between PLA and the inclusion complexes generated physical interactions that were able to limit the movement of the polymeric chains in the active films. Furthermore, the inclusion complexes agglomerations into the polymeric matrix of the active films observed in

Figure 1A could generate breakpoint zones in the materials that increased their fragility [

30].

2.1.5. Barrier Properties (Water Vapour and Oxygen Permeability)

Table 1 summarises the OP and WVP of the films evaluated at different RH. The permeability values of P0 were similar to those reported in previous works on PLA films [

31,

34]. Furthermore, the RH was not significantly influenced in the OP (p-value = 0.2101) and WVP (p-value = 0.6296) according to a multifactorial variance analysis. [

35] also reported a similar effect in PLA films from 40 to 90 %RH. Regarding active films, the incorporation of inclusion complexes in P5 and P10 films did not produce significant changes in their OP.

However, the incorporation of inclusion complexes to P5 and P10 films produced a significant and systematic increase in WVP of active films. This fact can be attributed to the presence of inclusion complexes on the surface of the films that favoured the adsorption of water molecules. Furthermore, in a previous study it was demonstrated that β-CD:AITC produced a more wettable film surface that could favour the water diffusion [

13].

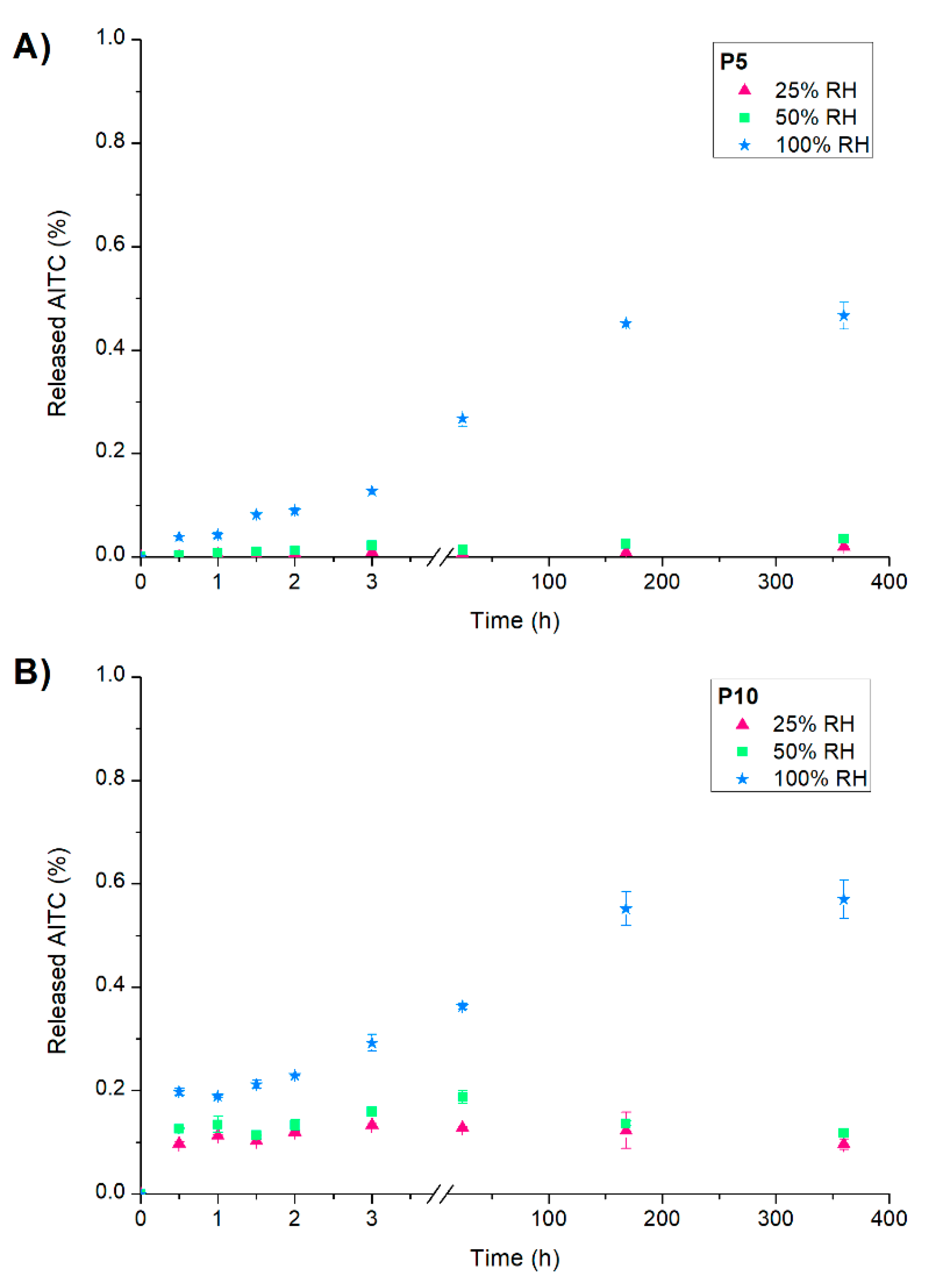

2.2. Releasing of AITC from Active Films (Responsive Capacity)

Figure 2a shows the curves of AITC release from active PLA films exposed at different RH. A slow initial release was observed in all cases, and the plateau was reached after 166 h (7 days). However, the increase in RH produced a higher release of AITC from P5 and P10, demonstrating that these films are RH-responsive materials. This fact was attributed to the interaction of water molecules through hydrogen bonds with the inclusion complexes that trigger the AITC release [

25]. This behaviour shows that the materials could maintain their functionality at low RH values and release the active compound at high RH, which are important factors for considering the storage and application of these active films at an industrial scale as food packaging materials.

On the other hand, the percentage of released AITC from P5 and P10 was similar when they were exposed to the same RH. This result could be associated with a similar distribution of inclusion complexes in the polymeric matrix for both films, as the FESEM micrographs evidenced. Nevertheless, it was expected a higher AITC release percentage from P10 since the agglomerations increased the diffusion rate of water molecules (according to barrier properties analysis), which could trigger the release of active compound from β-CD:AITC inclusion complexes [

25]. Therefore, it seems that AITC was mainly released from inclusion complexes located on the surface of the active films instead of the embedded ones. This fact could be confirmed by the low percentage of AITC released, considering the low loss of active compound during extrusion since the structure of inclusion complexes were maintained in the process according to XRD and DSC analysis.

2.3. Disintegration Under Composting Conditions

The disintegration under composting conditions is a decomposition process of organic matter carried out by microorganisms to carbon dioxide, water, and heat. PLA-based materials are generally converted to small fragments during this natural process, and soil benefits for the plant growth is obtained [

36]. The biodegradation of PLA starts with water diffusion through the polymeric matrix, producing a non-enzymatic hydrolysis of the polymer and a reduction of its molecular weight. Subsequently, oligomers and lactic acid obtained from the fragmentation of PLA are assimilated by microorganisms to be finally converted to carbon dioxide and water [

37,

38]. On the other hand, the biodegradation process of polymeric materials can be affected by the characteristics of the polymer, the environmental conditions, and the presence of additives. Therefore, the effect of incorporating β-CD:AITC inclusion complexes on the disintegration of PLA films under composting conditions was evaluated through macroscopic changes (colour, size, and texture), disintegration percentage, morphological, structural, and thermal properties.

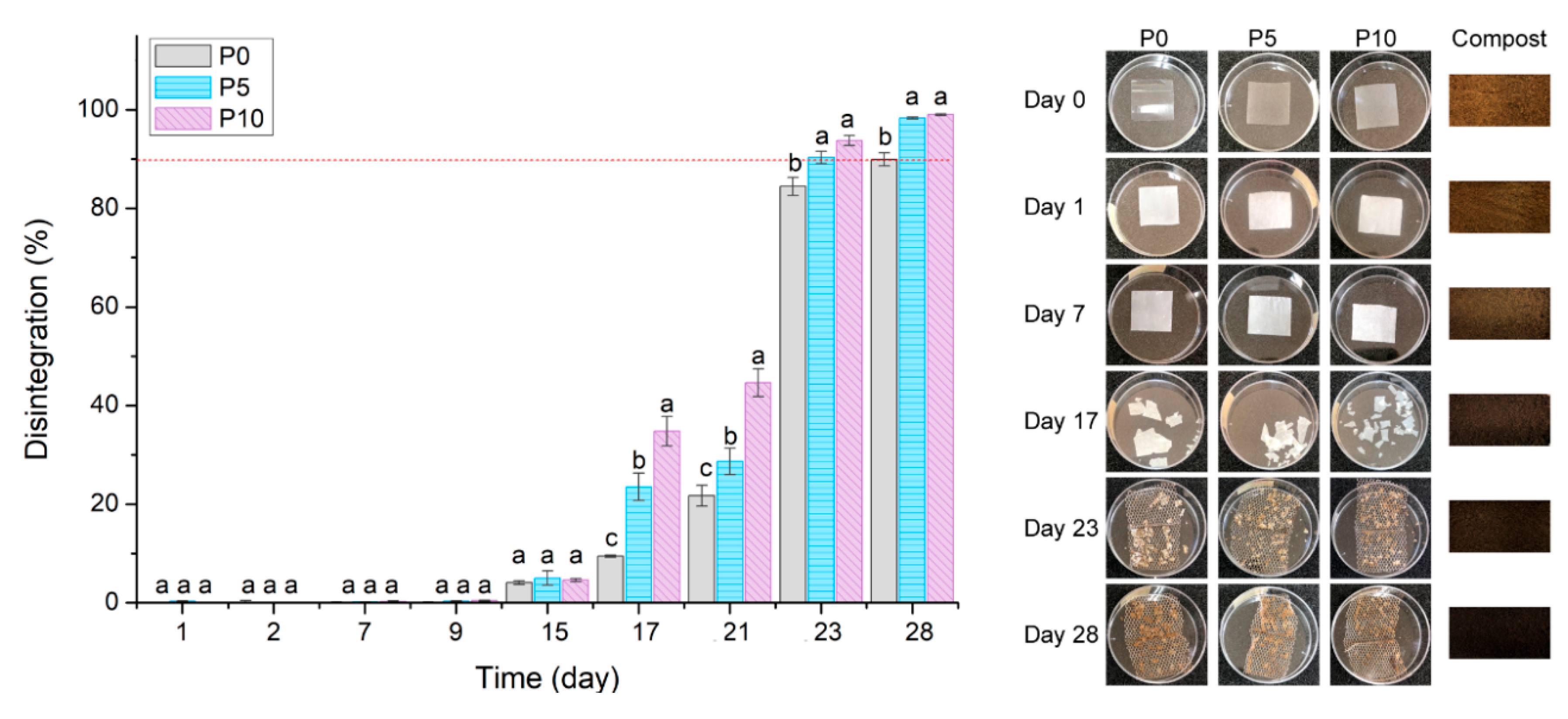

2.3.1. Macroscopic Changes and Disintegration Percentage

Figure 3 shows the disintegration percentage of PLA films and the changes that occurred in their visual appearance. The whitening of films produced an increase in their opacity at day 1. These visual changes have been widely reported as the result of the hydrolytic degradation of PLA due to the water intake from compost to the amorphous sites of the polymer matrix [

39,

40,

41]. Furthermore, the disintegration percentage of films was not modified up to day 9. This fact would be associated with the change in the polymer crystallinity and its way to be initially disintegrated (surface erosion), as it will be further discussed [

42]. At day 15, all films exhibited a disintegration percentage of 5%, similar results to those reported in other studies [

37,

39,

43,

44]. At day 17, the disintegration percentage of all materials started to increase, and samples lost their physical integrity, as evidenced by the fragmented films appearance. This phenomenon occurred due to the beginning of the polymer hydrolysis and the consequent assimilation of the short polymer chains by microorganisms.

Furthermore, it was evidenced that the highest content of inclusion complexes favoured the disintegration percentage and fragility of films. These changes are associated with active films mechanical and barrier characteristics. The lower tensile strength obtained for P5 and P10 films was related to the inclusion complexes agglomerations, as breakpoints, to improve the fragmentation of active films. Moreover, inclusion complexes increased the WVP of the polymer matrix due to their hydrophilic nature. As a result, active films could absorb and diffuse higher amounts of water from compost, producing a higher hydrolysis of PLA. On the other hand, the rupture of polymer chains possibly exposed the β-CD of inclusion complexes to microorganisms that could assimilate it as a substrate. This fact could support the results obtained on day 23, where both active films reached the objective of the disintegration test established by UNE-EN 13432 normative (represented by the dotted red line), while P0 reached 90% of disintegration on day 28.

Regarding the physico-chemical properties of synthetic solid bio-waste (compost), it started with pH = 5.4, volatile solids = 17.7% and dry solids = 48.0%, which indirectly showed around 50% moisture as the ISO 20200:2015 standard requires. After 28 days, the pH increased to 8.0, while volatile and dry solids decreased to 10.7% and 28.4%, respectively. This means that compost showed alkaline pH, higher carbon amounts, and around 72% moisture. These physico-chemical variations, as well as the colour change in the compost, evidenced the generation of water, ammonium, nitrogen, carbon and other substances derived from aerobic fermentation, which in turn confirmed the composting trial success during PLA and active films disintegration [

45].

2.3.2. Morphological Analysis

Figure 3 shows the disintegration percentage of PLA films and the changes that occurred in their visual appearance. The whitening of films produced an increase in their opacity at day 1. These visual changes have been widely reported as the result of the hydrolytic degradation of PLA due to the water intake from compost to the amorphous sites of the polymer matrix [

39,

40,

41]. Furthermore, the disintegration percentage of films was not modified up to day 9. This fact would be associated with the change in the polymer crystallinity and its way to be initially disintegrated (surface erosion), as it will be further discussed [

42]. At day 15, all films exhibited a disintegration percentage of 5%, similar results to those reported in other studies [

37,

39,

43,

44]. At day 17, the disintegration percentage of all materials started to increase, and samples lost their physical integrity, as evidenced by the fragmented films appearance. This phenomenon occurred due to the beginning of the polymer hydrolysis and the consequent assimilation of the short polymer chains by microorganisms.

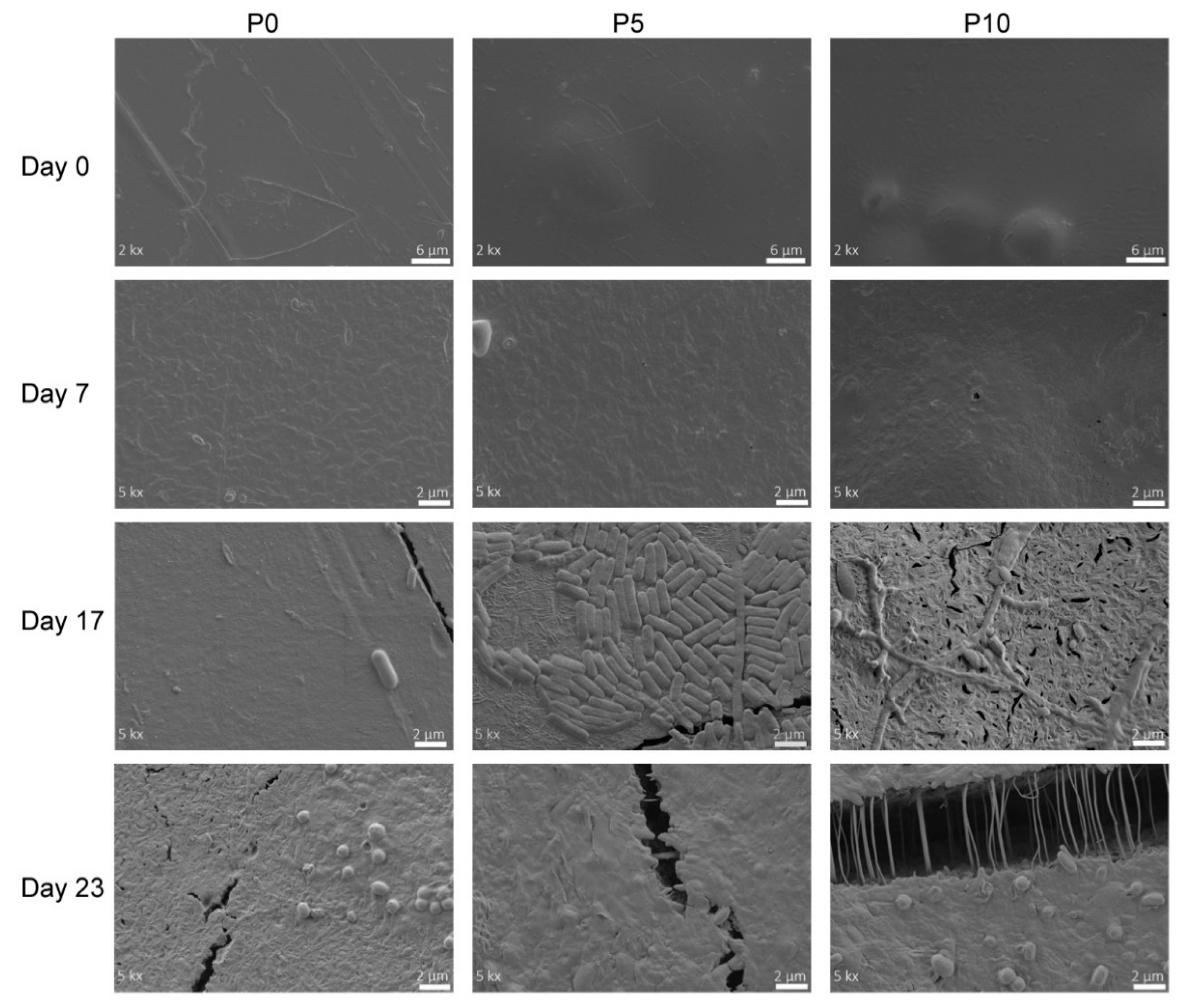

The changes occurring in the surface of the PLA films during their disintegration were followed by FESEM.

Figure 4 shows the micrographs of the materials subjected to different composting times. All films exhibited smooth surfaces and a highly compact structure during the first days of the trial. Furthermore, the presence of inclusion complexes in P5 and P10 films was also observed. On day 7, an increase in surface roughness was observed, which was associated with the beginning of films erosion caused by changes in crystallinity. Besides, the inclusion complexes contained in active films were exposed to the surface, and in the P10 film, the presence of small holes was evidenced. On day 17, some fractures in the materials surface were observed, in agreement with the increase in fragility caused by the disintegration process. For instance, the P0 film showed some fractures despite its surface was still mainly even. Instead, P5 and P10 films exhibited highly fractured surfaces due to the remarkable hydrolytic degradation favoured by the high water intake into the polymer matrix. Furthermore, micrographs of both active films showed that small polymeric chains produced by the disintegration started to be assimilated by the microorganisms, whose morphology is similar to

Stenotrophomonas pavanii, a PLA-degrading bacteria [

46]. It is important to note that the incorporation of inclusion complexes might delay the disintegration process due to the antimicrobial activity of AITC. However, the development of microorganisms was not significantly affected, because of the low concentration of the active compound. Moreover, it was observed in the WVP analysis that inclusion complexes enhanced the diffusion of water through matrix, improving the PLA hydrolysis [

17]. The advancement of the disintegration process (23 days in

Figure 4) favoured higher damage on the surface of P5 and P10 films. Thus, larger fractures were generated as the result of the strong hydrolysis of PLA. Furthermore, as this hydrolysis mainly occurred in amorphous zones, small crystalline spherulites appeared on the films surface, corresponding to crystalline sites of PLA that are further degraded [

37].

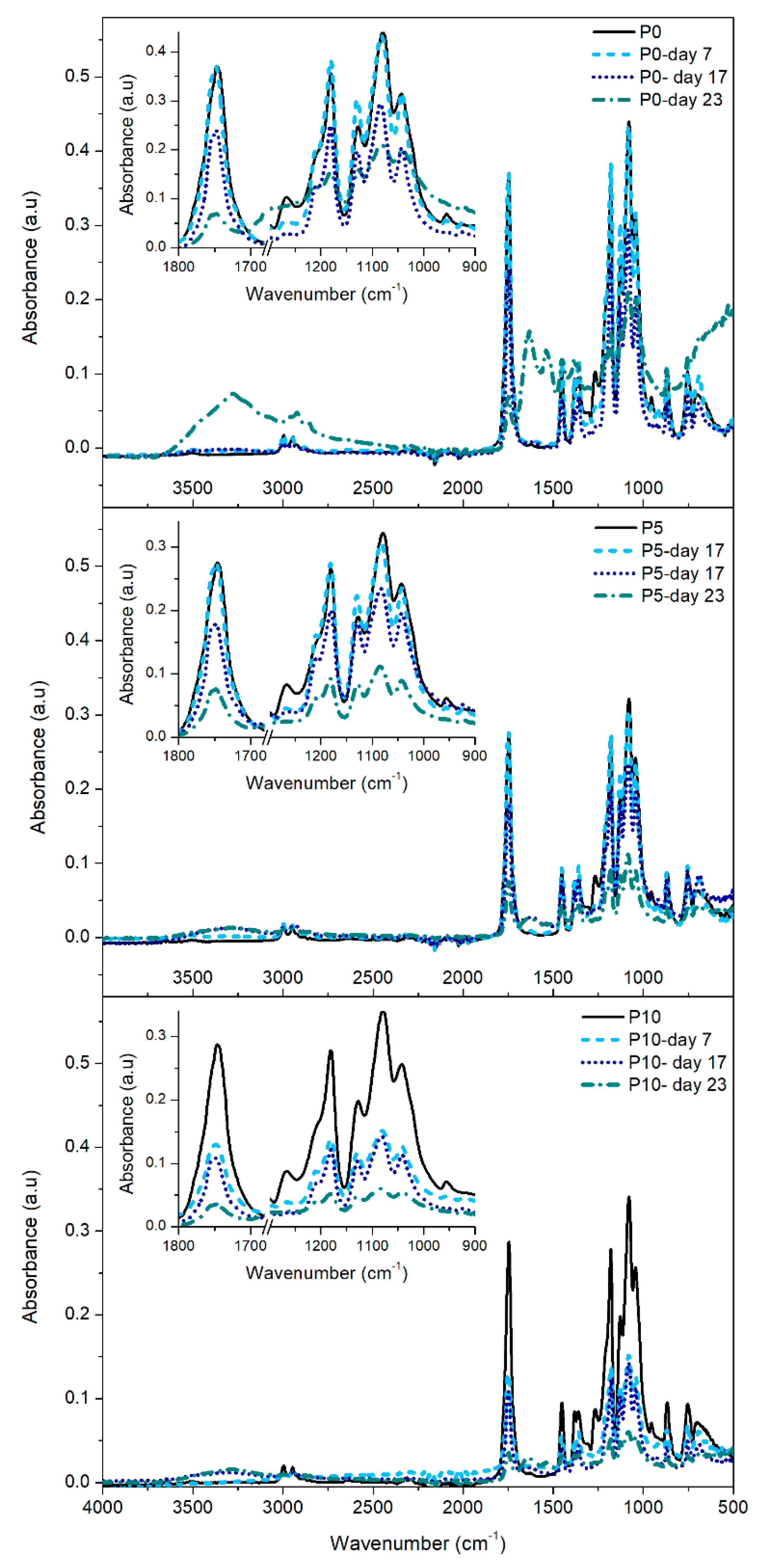

2.3.3. FTIR Analysis

Changes in the chemical structure of PLA and active films can be determined through the analysis of FTIR spectra, shown in

Figure 5. The FTIR analysis focused on the characteristic bands of PLA [

29,

45] associated with some specific regions of the spectra: (I) crystalline zone (920 and 1210 cm

-1); (II)amorphous zone (954 and 1268 cm

-1); (III) C-O and C-C-O bonds (bands from 1000 to 1150 cm

-1); (IV) stretching of carbonyl group C=O (1744 cm

-1); (V) C-H bonds of the polymeric chain (bands from 2900 to 3000 cm

-1).

Since all films were amorphous at day 0, the bands related to the crystalline zone of PLA were not detected in the corresponding spectrum. On day 7, a decrease in intensity of the bands at 954 and 1268 cm

-1 and the appearance of two new bands at 920 and 1210 cm

-1 were observed. These changes are related to the increase in the crystalline domains of the samples with low molecular weight as the result of the beginning of hydrolysis in the more accessible amorphous zones [

42,

45]. This fact, in turn, supports the changes observed in the visual appearance of the films during the first stage of the degradation trial. At day 17, the intensity of the bands associated with the carbonyl group and with C-O and C-C-O bonds decreased. These changes confirmed the hydrolytic scission of ester groups of PLA and the formation of lactic acid, lactide and oligomers [

47]. It was also remarkable the presence of two new bands in P5 and P10 films, one at 3300 cm

-1 associated with the presence of water in the polymer matrix and the exposition of hydroxyl groups of β-CD towards the films surface; while a small band detected at 1630 cm

-1 was related with the presence of free carboxylate ions produced by the assimilation of lactic acid and oligomers by microorganisms [

39,

45]. These findings support the fact that inclusion complexes facilitated the intake of water molecules into the polymer matrix, accelerating the hydrolytic degradation of PLA and the appearance of fractures in the materials, as observed by FESEM. These results demonstrated the increase of material fragility by the effect of the disintegration process of the polymer matrix. On day 23, a high decrease in the intensity of all FTIR bands was observed in all materials, especially in active films. Furthermore, the bands between 2900 and 3000 cm

-1 disappeared, showing the collapse of the polymeric structure by depletion of lactic acid and the final stretch of the disintegration process observed after 28 days [

48].

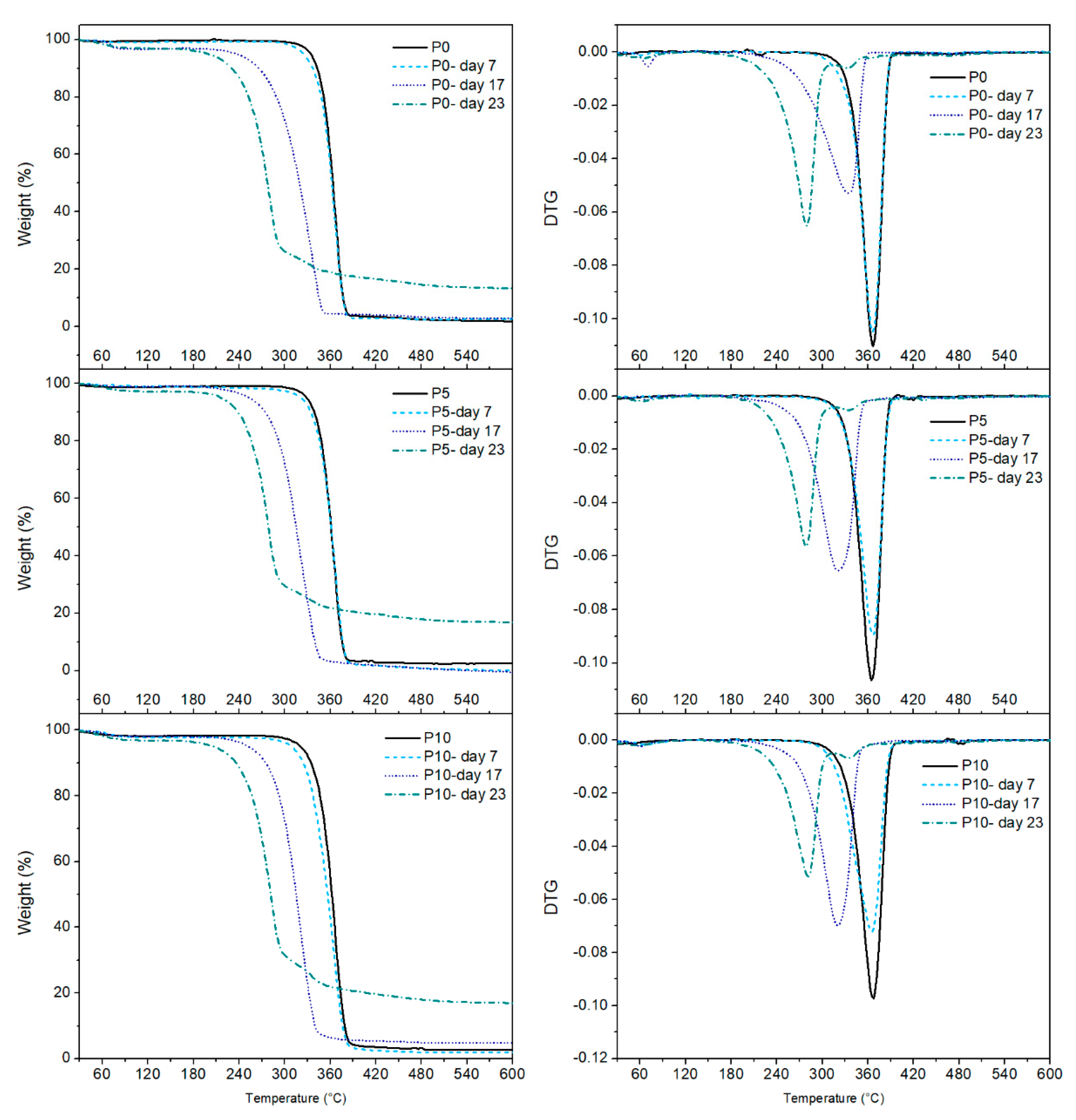

2.3.4. Thermal Analysis (TGA and DSC)

Figure 6 shows the TGA and DTGA curves of the films, while the main data are summarised in

Table 2. All samples exhibited only one thermal degradation process related to PLA. However, disintegration affected the samples maximum degradation temperature (T

deg). At day 0, all samples showed a maximum weight loss of films around 366 °C, which was maintained at day 7. This result confirmed that surface erosion occurred during this time, as it was previously discussed. The significant decrease of T

deg for all films at day 17 was associated with the reduction of the polymer molecular weight caused by the advanced hydrolysis process and the consequent microbial attack [

47]. However, this phenomenon primarily affected P5 and P10 films since their T

deg was lower than the T

deg in the P0 film, confirming that the presence of inclusion complexes improved polymer hydrolysis, generating shorter polymeric chains, which needed a lower temperature for degradation. At day 23, all materials exhibited a reduction of ≈ 70 °C from the initial T

deg showing the loss of the polymeric structure caused by degradation.

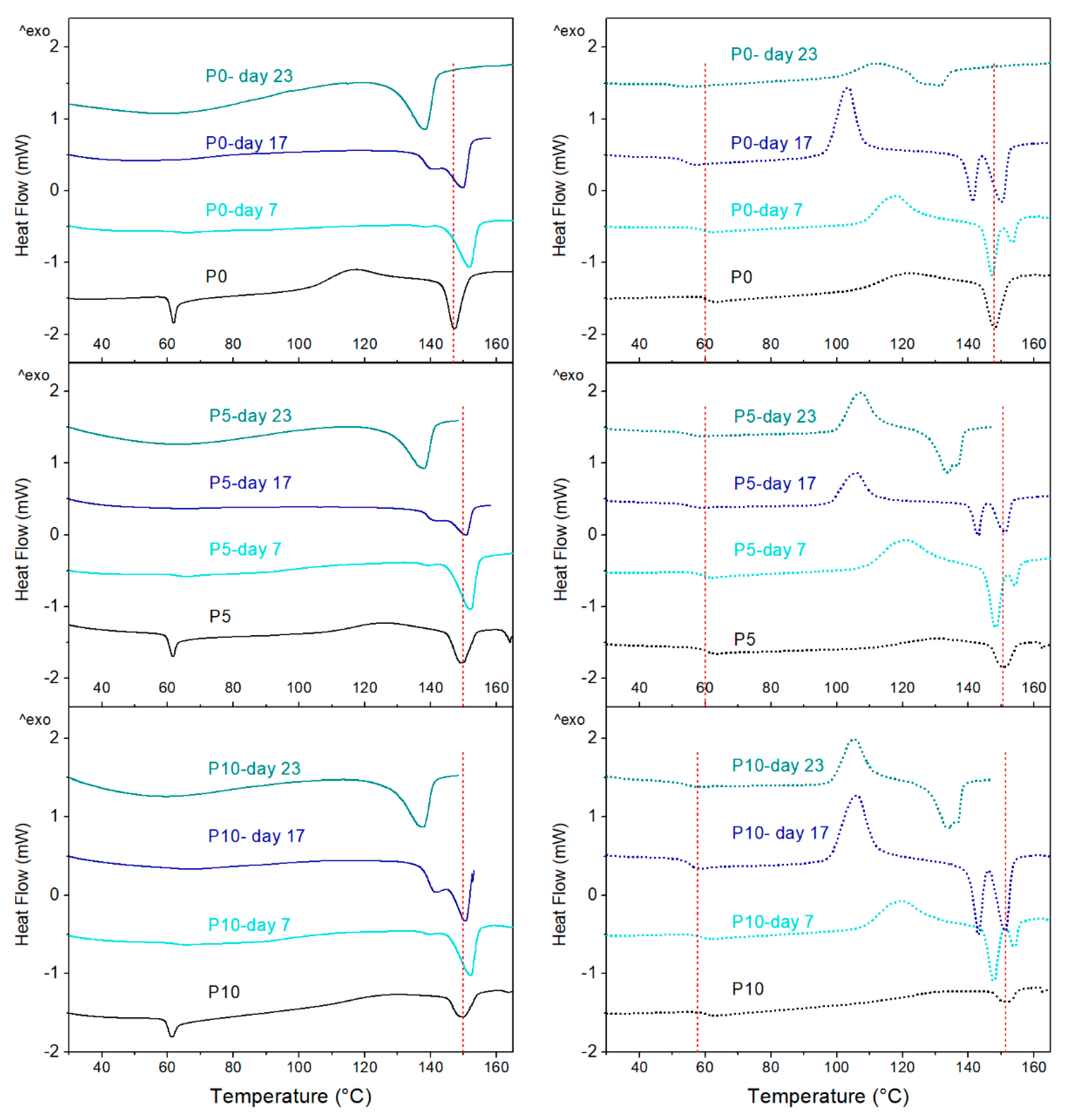

On the other hand, DSC thermograms obtained during the first and second heating scans are shown in

Figure 7. Furthermore, the DSC parameters obtained from different thermal events are detailed in

Table S1 and

Table S2. At day 0, the glass transition temperature (T

g) of PLA in P0, P5 and P10 was observed at 60 °C, while an endothermic peak characteristic of the enthalpic relaxation phenomenon was also observed [

49], followed by the cold crystallization (T

cc) around 120 °C and melting (T

m) at 150 °C. During the second heating scan, the peak associated with the enthalpy relaxation of PLA disappeared, and cold crystallization and melting enthalpies (∆H

cc and ∆H

m) were reduced. These changes were associated with the slow reorganisation of polymer chains during the cooling step.

On day 7, peaks corresponding to the enthalpy relaxation and cold crystallization of PLA disappeared in all films, while values for the T

m, ∆H

m and crystallinity (X

c) of materials were increased. These results are related to the hydrolysis of amorphous zones of PLA since they are responsible for these thermal transitions. For instance, the polymer amorphous zones are responsible for the cold crystallization [

41,

42,

47]. Moreover, the polymer amorphous zones increase the enthalpy relaxation, and a reduction in these zones decreases relaxation [

49]. Additionally, the decrease of the amorphous zones produces an increase in the polymer overall crystallinity, resulting in the need of higher melting energy. From day 17, T

g was not visible for any sample, and a small shoulder before the polymer melting was detected. This effect is attributed to the break of the polymer chains and the microbial attack to yield oligomers with different molecular weight and the formation of different crystalline structures able to melt at different temperatures [

47,

48]. Furthermore, the T

m of active films was reduced compared to values registered at day 7. This change supports the observation of a higher hydrolytic degradation of the active films. At day 23, a significant decrease in the melting temperature of materials was observed due to the high disintegration of samples, which triggered very small polymer chains. Furthermore, the polymer crystallinity was significantly increased, which supports the observations in the FESEM analysis, where crystalline spherulites were detected on the film surfaces.

On the other hand, the DSC thermograms obtained during the second heating for the disintegrated films (from day 7) also showed the thermal events associated with glass transition, cold crystallization, and the double melting peak of PLA. The progress in the disintegration process of materials progressively decreased the T

g value of the polymer while ∆H

cc and ∆H

m increased. These findings were attributed to changes in the amorphous / crystalline ratio of the polymeric matrix by the effect of the PLA hydrolysis. The presence of shorter polymeric chains improved the molecular mobility resulting in a lower T

g. The high molecular mobility caused a higher ordering of amorphous zones of the polymer and their later crystallization during heating. This fact is evident since the DSC thermograms of the films second heating showed the polymer cold crystallization, unlike the first heating. Furthermore, the presence of the two melting peaks in the films was associated with the different ways of PLA crystallization due to the heterogeneity in the molecular size of the polymer chains [

37,

48]. These observations agreed with the presence of spherulites on the films surface observed in the FESEM micrographs at day 17.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

β-cyclodextrin (purity >98.5%) was obtained from Cyclolab, Ltd. (Budapest, Hungary). The active compound allyl isothiocyanate (AITC >95%) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Santiago, Chile). Poly(lactic acid) resin (PLA) 2003D Ingeo™ was obtained from NatureWorks (Minetonka, MIN, USA). β-CD:AITC inclusion complexes (1:1 molar ratio) were obtained by a co-precipitation method already reported in a previous study [

25].

3.2. Films Preparation

PLA powder was dried at 50 °C for 48 h. Dried PLA or its different mixtures with inclusion complexes were melt-extruded in a 20-mm co-rotating laboratory twin-screw extruder Labtech LTE20 (Samutprakarn, Thailand). A temperature profile from 190 °C to 210 °C (feed zone to die zone) was used for the extrusion, and films were collected in an attached chill roll (Samutprakarn, Thailand) at 2 m min-1. Films were denoted as P0, P5 and P10 for neat PLA, PLA with 5% wt. and 10% wt. of the inclusion complex, respectively.

3.3. Film Characterisation

3.3.1. Field Emission Scanning Electronic Microscopy (FESEM)

Micrographs of the materials surface were taken in 1 kx and 2 kx using a FESEM Supra 25-Zeiss microscopy (Jena, Germany). Prior to FESEM measurements, samples were coated with a tungsten layer to enhance their electrical conductivity.

3.3.2. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

XRD diffractograms of samples were recorded between 2° and 80° of the 2θ angle at 0.05 Hz, 40 mA, 40 kV and CuKα radiation (k=1.54 Å) using a Bruker D8-Advance diffractometer (Madison, WI, USA).

3.3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Samples of 5-7 mg were put in an alumina crucible, and they were heated from 25 °C to 700 °C at 10 °C min-1 in a nitrogen atmosphere (50 mL min-1) using a TGA/SDTA 851e equipment (Mettler Toledo, Schwarzenbach, Switzerland). The maximum degradation temperature (Tdeg) of each sample was registered. The analysis was done in triplicate.

3.3.4.Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Samples of 3 mg (in triplicate) were introduced in a sealed aluminium crucible and submitted to a first heating from 0 to 160 °C, a cooling from 160 °C to 0 °C and a second heating from 0 °C to 150 °C. All scans were performed at 10 °C min

-1 in a nitrogen atmosphere (50 mL min

-1) using a DSC Q2000 (TA Instruments, USA). The percentage of crystallinity (

Xc) in the samples was calculated from DSC thermograms using

Equation (1).

where

ΔHm and

ΔHcc are the melting and cold crystallization enthalpies associated with T

m (melting temperature) and T

cc (cold crystallization temperature), while

ΔHm0 was the enthalpy for 100 % crystalline PLA (93 J g

-1 according to Xu et al. (2017) [

50] and

XIC was the fraction of inclusion complexes incorporated to the film (0.05 for P5 and 0.10 for P10).

3.3.5. Colour Measurements

CIEL*a*b* parameters of the materials were obtained using a CR-410 Minolta Chroma Meter colourimeter (Minolta Series, Japan) with a D65 illuminant, 2° observer and a standard white background (L*= 97.76, a*= -0.03 and b*= 1.87). The reported values were the mean of ten measurements for each film.

3.3.6. Mechanical Properties

The tensile properties were determined using a INSTRON 3344 equipment (Illinois Tool Works, USA) with a charge of 2 kN, initial separation of 125 mm and speed of 12.5 mm min-1, according to the ASTM D882-09 norm. The reported values were the mean of ten measurements for each film probe (150 mm x 2.5 mm).

3.3.7. Barrier Properties

Barrier properties considered as oxygen permeability (OP) and water vapour permeability (WVP) were evaluated at 50 and 80% RH, respectively. The OP was determined at 23 °C using an OXTRAN (MOCON, USA) equipment according to ASTM D3985-17 standard. Instead, the WVP values of films were determined using a Systech Illinois M7002 water permeation analyser (Industrial Physics, USA) at 37.8 °C, according to ASTM F1249-13 standard.

3.4. Release Vapour Phase (Responsive Capacity)

The AITC release kinetics from the materials to headspace was determined at 25, 50 and 100 % RH. Saturated salt solutions (0.6 mL) of potassium acetate, magnesium nitrate or distilled water were used inside 22 mL chromatograph vials to keep RH values. A film sample of 4 x 5 cm2 was rolled up in the top of the vial to avoid contact with the salt solution, and it was sealed with an aluminium lid coupled to a silicone/PTFE septum. Vials were stored at 20 °C and analysed at different times using a Turbomatrix 40 headspace analyser coupled to a Clarus 580 gas chromatograph (Perkin Elmer, USA). Three vials for each sample were prepared. For AITC quantification, the headspace autosampler took 0.2 mL of the headspace from the vial and transferred it to the gas chromatograph (GC). The injection temperature was set at 240 °C, and the column temperature started at 40 °C for 0.5 min, then it was heated to 120 °C at 20 °C min-1, it maintained this temperature for 0.5 min, and finally it increased to 270 °C at the same heating rate, keeping this temperature for 0.5 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at 11 psi, and the flame ionization detector (FID) was programmed at 260 °C. The released AITC at each time was quantified in triplicate using a calibration curve previously prepared with standards from 0 to 0.3 mgAITC Lair (R2=0.9970).

3.5. Disintegration in Compost Conditions

The disintegration trial was performed at a laboratory scale according to the ISO 20200:2015 standard. Films were cut into 25 x 25 mm

2 pieces, weighted, and placed in a textile mesh to facilitate the removal during composting test. Samples were buried at approximately 6 cm depth in perforated plastic boxes with a moist synthetic solid bio-waste (40% of sawdust, 30% of rabbit food, 10% starch, 10% compost, 5% sugar, 3% corn oil, and 2% urea with 50 wt% of water). These reactors were stored at 58 °C and 50% RH in aerobic conditions. Bio-waste was scrambled, and evaporated water was restored according to the norm. Samples were analysed at different times (0, 1, 2, 7, 9, 15, 17, 21, 23 and 28 days), by removing them from the textile mesh, washing with deionized water, drying for 24 h and weighing. The percentage of disintegration at each time was calculated using the

Equation (2).

where

Wi and

Wt correspond to the sample weight before the assay and after its remotion/drying operation, respectively.

Photographs of test samples were taken when a principal visual change occurred (7, 17 and 23 days). In addition, these samples were analysed through FESEM, TGA, DSC and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to follow the morphological, thermal, and chemical changes of films during the disintegration process. The physicochemical properties of synthetic solid bio-waste, such as pH, volatile and dry solids, and colour, were also assessed before and after the trial.

4. Conclusions

The incorporation of β-CD:AITC inclusion complexes to PLA matrices through extrusion processing results in major changes in the morphological, thermal and barrier properties of the obtained films. Although inclusion complexes were agglomerated in the polymer matrix, they improve the thermal stability of the polymer. Moreover, oxygen permeability of PLA was not modified by the addition of inclusion complexes, but they produced higher water vapour permeability due to their high water-sorption capacity. In addition, non-detectable colour changes were produced by the incorporation of inclusion complexes to PLA, which is an important parameter for food packaging applications. Furthermore, the incorporation of inclusion complexes to PLA films reduced the disintegration time of materials under composting conditions by 5 days, achieving the maximum disintegration rate after 23 days. The water absorption capacity of the inclusion complexes is the main reason for this reduction by accelerating the polymer hydrolysis. This fact was supported by the significant changes in the morphological, chemical-structural, and thermal properties of the active films during the disintegration trial.

The release processes of AITC in the headspace was promoted by the increase of RH, regardless of the inclusion complex concentration. This means that PLA/inclusion complex films are RH-responsive materials that can maintain their functionality at low RH and release the active compound within a specific time under controlled conditions. This behaviour could be useful for determining the material storage conditions and their application for food that require an antimicrobial function at high moisture, such as fruit and vegetables.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: DSC parameters obtained during the first heating of the PLA (P0) and active (P5 and P10) films subjected to the disintegration process under composting conditions; Table S2: DSC parameters obtained during the second heating of the PLA (P0) and active (P5 and P10) films subjected to the disintegration process under composting conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M-S., M.R., and F.R.M.; methodology: C.M-S., M.R., and F.R.M; validation, C.M-S., M.R., M.C.G. and F.R.M; formal analysis, C.M-S., M.R., M.C.G., A.J. and F.R.M.; investigation, C.M-S. and M.R ; resources, C.M-S., F.R.M., A.G., M.J.G., A.J. and M.C.G..; data curation, C.M-S., M.R., and F.R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M-S.; writing—review and editing, C.M-S., M.R., M.C.G., A.J. and F.R.M; visualization, X.X.; supervision, M.R., and F.R.M; project administration, F. .R.M., A.G., M.J.G., A.J. and M.C.G..; funding acquisition, .R.M., A.G., M.J.G., A.J. and M.C.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was founded by the “Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo” (ANID Chile) through the PhD Grant [ANIDPFCHA/Doctorado Nacional/2019-21190326], Regular FOND-ECYT project [1180686] and by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the Spanish Research Agency (Ref. PID2020-116496RB-C21).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was founded by the “Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo” (ANID Chile) through the PhD Grant [ANIDPFCHA/Doctorado Nacional/2019-21190326] and Regular FONDECYT project [1180686]. Additionally, the authors would like to thank the Conservation and Food Safety group from IATA-CSIC and Dr. Patiño Vidal for carrying out the oxygen permeability tests. This work was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the Spanish Research Agency (Ref. PID2020-116496RB-C21).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lombardi, A.; Fochetti, A.; Vignolini, P.; Campo, M.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Puglia, D.; Luzi, F.; Papalini, M.; Renzi, M.; et al. Natural Active Ingredients for Poly (Lactic Acid)-Based Materials: State of the Art and Perspectives. Antioxidants 2022, Vol. 11, Page 2074 2022, 11, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Singh, S.; Bahmid, N.A.; Mehany, T.; Shyu, D.J.H.; Assadpour, E.; Malekjani, N.; Castro-Muñoz, R.; Jafari, S.M. Release of Encapsulated Bioactive Compounds from Active Packaging/Coating Materials and Its Modeling: A Systematic Review. Colloids and Interfaces 2023 2023, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlake, J.R.; Tran, M.W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Burrows, A.D.; Xie, M. Biodegradable Biopolymers for Active Packaging: Demand, Development and Directions. Sustainable Food Technology 2023, 1, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlake, J.R.; Tran, M.W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Burrows, A.D.; Xie, M. Biodegradable Active Packaging with Controlled Release: Principles, Progress, and Prospects. ACS Food Science and Technology 2022, 2, 1166–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Shugulí, C.; Patiño Vidal, C.; Cantero-López, P.; Lopez-Polo, J. Encapsulation of Plant Extract Compounds Using Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes, Liposomes, Electrospinning and Their Combinations for Food Purposes. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021, 108, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Tavakoli, O.; Khoobi, M.; Wu, Y.S.; Faramarzi, M.A.; Gholibegloo, E.; Farkhondeh, S. Beta-Carotene/Cyclodextrin-Based Inclusion Complex: Improved Loading, Solubility, Stability, and Cytotoxicity. J Incl Phenom Macrocycl Chem 2022, 102, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benucci, I.; Mazzocchi, C.; Lombardelli, C.; Del Franco, F.; Cerreti, M.; Esti, M. Inclusion of Curcumin in B-Cyclodextrin: A Promising Prospective as Food Ingredient. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A 2022, 39, 1942–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño Vidal, C.; López de Dicastillo, C.; Rodríguez-Mercado, F.; Guarda, A.; Galotto, M.J.; Muñoz-Shugulí, C. Electrospinning and Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes: An Emerging Technological Combination for Developing Novel Active Food Packaging Materials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2021, 62, 5495–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran Maniam, M.M.; Loong, Y.H.; Samsudin, H. Understanding the Formation of β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes and Their Use in Active Packaging Systems. Starch 2022, 74, 2100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, F.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Lai, D.; Sriboonvorakul, N.; Hu, J. A Review of Cyclodextrin Encapsulation and Intelligent Response for the Release of Curcumin. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.B.; Patel, J.K. Chemopreventive Aspects, Investigational Anticancer Applications and Current Perspectives on Allyl Isothiocyanate (AITC): A Review. Mol Cell Biochem 2023, 478, 2763–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.S.; Dias, M.V.; Soares, N. de F.F.; Borges, S.V.; de Oliveira, I.R.N.; Pires, A.C. dos S.; Medeiros, E.A.A.; Alves, E. Ultrastructural and Antimicrobial Impacts of Allyl Isothiocyanate Incorporated in Cellulose, β-Cyclodextrin, and Carbon Nanotubes Nanocomposites. Journal of Vinyl and Additive Technology 2021, 27, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Shugulí, C.; Rodríguez-Mercado, F.; Benbettaieb, N.; Guarda, A.; Galotto, M.J.; Debeaufort, F. Development and Evaluation of the Properties of Active Films for High-Fat Fruit and Vegetable Packaging. Molecules 2023, 28, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abellas, E.L.; Bentain, K.B.; Mahilum, R.J.D.; Pelago, C.R.J.; Yntig, R.M.; John, M.S. Bioplastic Made from Starch as a Better Alternative to Commercially Available Plastic. Sci Educ (Dordr) 2021, 2, 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Swetha, T.A.; Bora, A.; Mohanrasu, K.; Balaji, P.; Raja, R.; Ponnuchamy, K.; Muthusamy, G.; Arun, A. A Comprehensive Review on Polylactic Acid (PLA) – Synthesis, Processing and Application in Food Packaging. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 234, 123715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzyńska-Mizera, M.; Knitter, M.; Szymanowska, D.; Mallardo, S.; Santagata, G.; Di Lorenzo, M.L. Optical, Mechanical, and Antimicrobial Properties of Bio-Based Composites of Poly(L-Lactic Acid) and D-Limonene/β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex. J Appl Polym Sci 2022, 139, 52177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A.; Velásquez, E.; Patiño, C.; Guarda, A.; Galotto, M.J.; López de Dicastillo, C. Active PLA Packaging Films: Effect of Processing and the Addition of Natural Antimicrobials and Antioxidants on Physical Properties, Release Kinetics, and Compostability. Antioxidants 2021, Vol. 10, Page 1976 2021, 10, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, F.; Pajohi-Alamoti, M.; Emamifar, A.; Nourian, A. Fabrication and Characterization of Active Poly(Lactic Acid) Films Containing Thymus Daenensis Essential Oil/Beta-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex and Silver Nanoparticles to Extend the Shelf Life of Ground Beef. Food Bioproc Tech 2023, 17, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhou, A.; Fang, D.; Lu, T.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Lyu, L.; Wu, W.; Huang, C.; Li, W. Oregano Essential Oil/β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Compound Polylactic Acid/Polycaprolactone Electrospun Nanofibers for Active Food Packaging. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 445, 136746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qiu, C.; Narsimhan, G.; Jin, Z. Preparation and Characterization of Ternary Antimicrobial Films of β-Cyclodextrin/Allyl Isothiocyanate/Polylactic Acid for the Enhancement of Long-Term Controlled Release. Materials 2017, 10, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarca, R.L.; Rodríguez, F.J.; Guarda, A.; Galotto, M.J.; Bruna, J.E.; Fávaro Perez, M.A.; Ramos Souza Felipe, F.; Padula, M. Application of β-Cyclodextrin/2-Nonanone Inclusion Complex as Active Agent to Design of Antimicrobial Packaging Films for Control of Botrytis Cinerea. Food Bioproc Tech 2017, 10, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhu, M.; Miao, K.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Mu, C. Development of Antimicrobial Gelatin-Based Edible Films by Incorporation of Trans-Anethole/β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex. Food Bioproc Tech 2017, 10, 1844–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, K.; Zhen, W.; Luo, D.; Zhao, L. Preparation, Structure, and Performance of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Vermiculite-Poly(Lactic Acid)-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex Nanocomposites. Polym Adv Technol 2021, 32, 2218–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Chen, X.; Park, H.J. Calcium-Alginate Beads Loaded with Gallic Acid: Preparation and Characterization. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2016, 68, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Shugulí, C.; Rodríguez-Mercado, F.; Mascayano, C.; Herrera, A.; Bruna, J.E.; Guarda, A.; Galotto, M.J. Development of Inclusion Complexes With Relative Humidity Responsive Capacity as Novel Antifungal Agents for Active Food Packaging. Front Nutr 2022, 8, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, A.; Aadil, K.R.; Jha, H. Synthesis and Characterization of Lignin-Poly Lactic Acid Film as Active Food Packaging Material. https://doi-org.ezproxy.usach.cl/10.1080/10667857.2020.1782060 2020, 36, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Fei, X.; He, Y.; Li, H. Poly(Lactic Acid)-Based Composite Film Reinforced with Acetylated Cellulose Nanocrystals and ZnO Nanoparticles for Active Food Packaging. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 186, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Contreras, F.; Acevedo-Parra, H.; Nuño-Donlucas, S.M.; Núñez-Delicado, E.; Gabaldón, J.A. Development and Characterization of a Biodegradable PLA Food Packaging Hold Monoterpene–Cyclodextrin Complexes against Alternaria Alternata. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.N.; Redhwi, H.H.; Tsagkalias, I.; Vouvoudi, E.C.; Achilias, D.S. Development of Bio-Composites with Enhanced Antioxidant Activity Based on Poly(Lactic Acid) with Thymol, Carvacrol, Limonene, or Cinnamaldehyde for Active Food Packaging. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YousefniaPasha, H.; Mohtasebi, S.S.; Tabatabaeekoloor, R.; Taherimehr, M.; Javadi, A.; Soltani Firouz, M. Preparation and Characterization of the Plasticized Polylactic Acid Films Produced by the Solvent-Casting Method for Food Packaging Applications. J Food Process Preserv 2021, 45, e16089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Y.; Rodriguez, K.; Han, J.H.; Kim, Y.T. Improved Thermal Stability of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Composite Film via PLA–β-Cyclodextrin-Inclusion Complex Systems. Int J Biol Macromol 2015, 81, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenyorege, E.A.; Ma, H.; Aheto, J.H.; Agyekum, A.A.; Zhou, C. Effect of Sequential Multi-Frequency Ultrasound Washing Processes on Quality Attributes and Volatile Compounds Profiling of Fresh-Cut Chinese Cabbage. LWT 2020, 117, 108666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, A.; Park, S.; Volpe, S.; Torrieri, E.; Masi, P. Active Packaging Based on PLA and Chitosan-Caseinate Enriched Rosemary Essential Oil Coating for Fresh Minced Chicken Breast Application. Food Packag Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, C.; Xu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Antibacterial Polylactic Acid Film Incorporated with Cinnamaldehyde Inclusions for Fruit Packaging. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 164, 4547–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auras, R.A.; Harte, B.; Selke, S.; Hernandez, R. Mechanical, Physical, and Barrier Properties of Poly(Lactide) Films: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/8756087903039702 2016, 19, 123–135, doi:10.1177/8756087903039702. [CrossRef]

- Weligama Thuppahige, V.T.; Karim, M.A. A Comprehensive Review on the Properties and Functionalities of Biodegradable and Semibiodegradable Food Packaging Materials. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2022, 21, 689–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Montes, M.L.; Soccio, M.; Luzi, F.; Puglia, D.; Gazzano, M.; Lotti, N.; Manfredi, L.B.; Cyras, V.P. Evaluation of the Factors Affecting the Disintegration under a Composting Process of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) (PLA/PHB) Blends. Polymers 2021, Vol. 13, Page 3171 2021, 13, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalita, N.K.; Nagar, M.K.; Mudenur, C.; Kalamdhad, A.; Katiyar, V. Biodegradation of Modified Poly(Lactic Acid) Based Biocomposite Films under Thermophilic Composting Conditions. Polym Test 2019, 76, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; López, J.; Rayón, E.; Jiménez, A. Disintegrability under Composting Conditions of Plasticized PLA–PHB Blends. Polym Degrad Stab 2014, 108, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerro, D.; Bustos, G.; Villegas, C.; Buendia, N.; Truffa, G.; Godoy, M.P.; Rodríguez, F.; Rojas, A.; Galotto, M.J.; Constandil, L.; et al. Effect of Supercritical Incorporation of Cinnamaldehyde on Physical-Chemical Properties, Disintegration and Toxicity Studies of PLA/Lignin Nanocomposites. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 167, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Fortunati, E.; Peltzer, M.; Jimenez, A.; Kenny, J.M.; Garrigós, M.C. Characterization and Disintegrability under Composting Conditions of PLA-Based Nanocomposite Films with Thymol and Silver Nanoparticles. Polym Degrad Stab 2016, 132, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, M.A.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.W.; Deep, A. Hydrolytic Degradation of Polylactic Acid (PLA) and Its Composites. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 79, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Kopitzky, R.; Tolga, S.; Kabasci, S. Polylactide (PLA) and Its Blends with Poly(Butylene Succinate) (PBS): A Brief Review. Polymers 2019, Vol. 11, Page 1193 2019, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Fortunati, E.; Peltzer, M.; Dominici, F.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.D.C.; Kenny, J.M. Influence of Thymol and Silver Nanoparticles on the Degradation of Poly(Lactic Acid) Based Nanocomposites: Thermal and Morphological Properties. Polym Degrad Stab 2014, 108, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, F.R.; Arrieta, M.P.; Elena Antón, D.; Lozano-Pérez, A.A.; Cenis, J.L.; Gaspar, G.; de la Orden, M.U.; Martínez Urreaga, J. Effect of Yerba Mate and Silk Fibroin Nanoparticles on the Migration Properties in Ethanolic Food Simulants and Composting Disintegrability of Recycled Pla Nanocomposites. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaaba, N.F.; Jaafar, M. A Review on Degradation Mechanisms of Polylactic Acid: Hydrolytic, Photodegradative, Microbial, and Enzymatic Degradation. Polym Eng Sci 2020, 60, 2061–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Montes, M.L.; Luzi, F.; Dominici, F.; Torre, L.; Manfredi, L.B.; Cyras, V.P.; Puglia, D. Migration and Degradation in Composting Environment of Active Polylactic Acid Bilayer Nanocomposites Films: Combined Role of Umbelliferone, Lignin and Cellulose Nanostructures. Polymers 2021, Vol. 13, Page 282 2021, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.; Fortunati, E.; Beltrán, A.; Peltzer, M.; Cristofaro, F.; Visai, L.; Valente, A.J.M.; Jiménez, A.; María Kenny, J.; Carmen Garrigós, M. Controlled Release, Disintegration, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Properties of Poly (Lactic Acid)/Thymol/Nanoclay Composites. Polymers 2020, Vol. 12, Page 1878 2020, 12, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nofar, M. Polylactide (PLA): Molecular Structure and Properties. Multiphase Polylactide Blends 2021, 97–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Xie, J.; Lei, C. Influence of Melt-Draw Ratio on the Crystalline Behaviour of a Polylactic Acid Cast Film with a Chi Structure. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 39914–39921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).