1. Introduction

Nowadays the need to reduce climate change phenomena and reduce carbon dioxide fingerprint forces the transition of the global economy to a more sustainable model with less use of fossil fuels in all sectors of industry [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This is called green transition or transition to a circular economy. In the sector of food technology circular economy demands the replacement of packaging materials based on fossil fuels which cannot be biodegraded by natural biodegradable biopolymers such as cellulose, starch, and chitosan or by biodegradable polymers, which can be developed from waste and byproducts such as poly-lactic acid (PLA) [

3,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. PLA is produced via the various polymerization processes of lactide acid (LA). LA can be recovered for various food and agricultural byproducts and thus it is considered as cheap [

13,

14,

15]. Another advantage of PLA is its ability to be used in melting blowing processes to produce industrially packaging films [

16,

17]. Thus, PLA has a great potential to replace fossil-based polymers in food packaging industry [

10,

12,

18,

19]. A disadvantage of PLA is its poor mechanical and thermomechanical properties [

20]. That’s why PLA is plasticized with various bio-based plasticizers [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Recently tri-ethyl-citrate (TEC) has been proved to be a very promising food grade bio-based plasticizer of PLA since it has achieved to improve PLA’s viscoelastic properties and give a PLA/TEC composite matrix with good water/oxygen barrier properties, improved antioxidant/antibacterial activity and most of all novel self-healable properties [

27].

One the other hand food safety under the spirit of green transition and circular economy demands the replacement of chemical additives by bio-based antioxidant/antibacterial agents such as natural extracts and essential oils (EOs) and their derivatives [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Carvacrol (CV) is the main component of oregano EO and it is a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) substance [

35,

36]. CV has been widely used to develop active packaging films with various polymer or biopolymer matrixes because of its high antioxidant/antibacterial activity and its desirable odor for fresh meat products [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Another trend in food safety sector is the removement of chemical additives from food and their encapsulation-incorporation into the packaging material to be released slowly in the food [

45,

46,

47]. Various technologies have been developed in the last decade for the encapsulation or nanoencapsulation of such EOs and their derivatives in the packaging films which makes them active packaging [

48,

49]. One of the most promising technologies is the adsorption of such EOs in cheap and biobased nanocarriers such as nanoclays, natural zeolites, silicas, and activated carbons (AC) to produce active nanohybrids followed by the dispersion of such active nanohybrids in polymer or biopolymer matrix [

37,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. AC has been recently used as nanocarrier of EOs and their derivatives because of its low cost, as it can be derived from various food and agricultural byproducts [

61]. AC’s high specific surface area and micro/meso-porosity structure make it an ideal nanocarrier for the absorption of high amounts of EOs and their derivatives and their slow release in food [

53,

58,

62,

63,

64]. In advance, its black color is considered as favorable for the packaging of fresh meat products [

65].

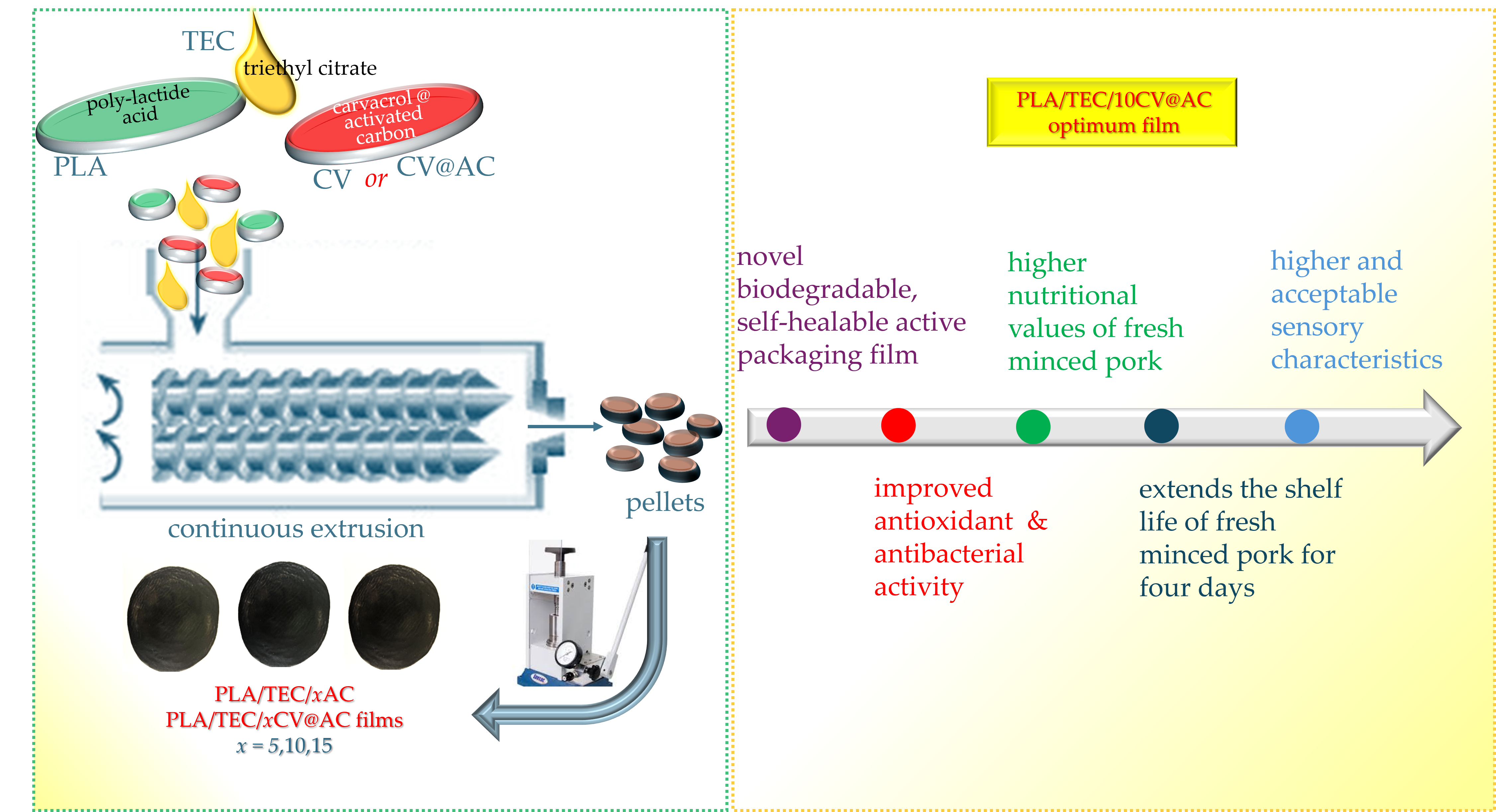

Recently the development and the characterization of a carvacrol@natural zeolite (CV@NZ) nanohybrid was presented. A novel vacuum assisted adsorption method was used which achieved to increase the CV absorbed amount on NZ up to 61 wt.%. This novel CV@NZ nanohybrid was incorporated in self-healable PLA/TEC matrix to obtain PLA/TEC/CV@NZ active film. This film, due to its high CV content achieved to extend the shelf life of fresh minced pork to four days. Herein the development and characterization of a novel CV@AC nanohybrid is presented employing the same vacuum assisted adsorption method. This novel CV@AC nanohybrid is incorporated in PLA/TEC via melt extrusion process at 5, 10 and 15 wt.% nominal contents to obtain novel PLA/TEC/xCV@AC (x=5, 10, and 15) active films. PLA/TEC films incorporated with 5, 10 and 15 wt.% pure AC nominal contents (PLA/TEC/xAC) was also prepared for comparison. The optimum PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active film is used to wrap and extend the shelf-life of fresh pork minced meat by monitoring the total variable counts, the lipid oxidation, the heme iron content and the sensory analysis during 10 days of storage at 4 oC. Innovative aspects of the current study are: (1) the development and characterization of CV@AC nanohybrid, (2) the development and characterization of novel both PLA/TEC/xCV@AC and PLA/TEC/xAC films, and (3) the shelf-life experiment of fresh pork minced meat using the optimum PLA/TEC/xCV@AC film as active film.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

PLA with the trade name Ingeo™ Biopolymer 3052D, crystalline melt temperature of 145–160 oC, and glass transition temperature of 55–60 oC was purchased from NatureWorks LLC (Minnetonka, MN, USA). Liquid triethyl citrate (TEC) with an Mw of 276.3 g/mol was purchased from Alfa Aesar GmbH & Co KG, (Karlsruhe, Germany). Charcoal Activated Carbon (AC) with CAS Number 7440-44-0 (product number 31616-250g), soluble in water (0.5%) with specific surface area (BET), ≥ 800 m²/g was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). 2,2-Diphenyl-1- picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Ethanol absolute for analysis and acetate buffer (CH3COONa·3H2O) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). The bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 6571) and Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhimurium (NCTC 12023) were supplied by Supelco® Analytical Products, a subsidiary of Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) as microbiological certified reference materials in the form of easy-tab™ pellets (S. aureus) by LGC Standards Proficiency Testing (Chamberhall Green Bury, Lancashire, UK) and in the form of disc-shaped Vitroids™ (S. Typhimurium). one Gram-negative

2.2. Preparation of CV@AC Nanohybrid

The CV@AC nanohybrid was prepared using the vacuum assisted method and the homemade apparatus recently presented in detail [

37].

2.3. Preparation of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

For the development of all PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC nanocomposite

pellets, a Mini Lab twin-screw extruder (Haake Mini Lab II, Thermo Scientific, ANTISEL,

S.A., Athens, Greece) was employed. The sample code names, the contents of PLA, TEC, pure AC, and CV@AC nanohybrid as well as the twin extruder operating conditions (temperature and speed) used for the development of all PLA/TECx composite blends are listed in

Table 1 for comparison. All the pellets obtained after the extrusion process were thermomechanically formed into films through a heat pressing process using a hydraulic press with heated platens (Specac Atlas™ Series Heated Platens, Specac, Orpinghton, UK) at constant pressure of 0.5 MPa and temperature of 180 °C. Approximately 1.0 g of pellets was added to obtain each film with an average diameter of 11 cm and a thickness of 0.10–0.15 mm.

2.4. Physicochemical Characterization of CV@AC Nanohybrid

2.4.1. CV Desorption Release Kinetics of CV@AC

Determination of CV wt.% desorbed content and CV release rate is crucial for such CV@AC nanohybrids. For this reason, CV desorption release kinetics took place by employing moisture analyzer AXIS AS-60 (AXIS Sp. z o.o. ul. Kartuska 375b, 80–125 Gdańsk, Poland). Approximately 100 mg of CV@AC nanohybrid was spread in the inner disk of moisture analyzer and its mass loss (m

t) was recorded as a function of time (t) at 50, 70, 90, and 110 °K. At least three desorption experiments were done at each temperature. From the recorded m

t and t values the desorption isotherms plots were constructed by plotting the values of (1 − m

0/m

t) as a function of t. The plots were fitted using the well-known pseudo-second-order adsorption-desorption equation [

66,

67]. For process order, n=2 the overall normalized mass balance is given by:

where k

2 is the rate constant of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model (s

−1), qt is the desorbed fraction capacity at time t, q

e=(1-m

e/m

0) is the maximum desorbed fraction capacity at equilibrium, m

0 is the initial CV loading into the nanohybrid, and m

t is the CV amount remaining in the nanohybrid at time t. By integrating equation (1) we achieve the pseudo-second-order kinetic model:

The initial release rate can be computed via the equation (1) and for t=0 (i.e., q

t=0). Thus:

From the best-fitted plots, the k

2 and q

e values were calculated. Using the estimated k

2 parameter the ln(k

2) term was calculated and plotted as a function of (1/T) to determine the desorption energy (Ε

0des) according to the Arrhenius equation and the theory presented in detail in [

68,

69,

70]:

and its linear transformed type:

where k

2 is the rate constant of the pseudo-second order kinetic model (s

−1), Ε

0des is the desorption activation energy, and A is the Arrhenius constant.

2.4.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis of CV@AC

To study the structural characteristics of CV@AC nanohybrid XRD powder analysis was performed in CV@AC as well as in pure AC in the range of 0.5–40 2 theta by employing a Brüker XRD D8 Advance diffractometer (Brüker, Analytical Instruments, S.A., Athens, Greece).

2.4.3. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis of CV@AC

To study potential relaxation between CV adsorbed molecules and AC FTIR spectroscopy analysis was performed for both CV@AV nanohybrid and pure AC powder in the range of 400 to 4000 cm−1 with an FT/IR-6000 JASCO Fourier-transform spectrometer (JASCO, Interlab, S.A., Athens, Greece).

2.5. Physicochemical Characterization of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films

2.5.1. XRD Analysis of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

All obtained PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as pure PLA/TEC film were structurally characterized employing a Brüker XRD D8 Advance diffractometer (Brüker, Analytical Instruments, S.A., Athens, Greece) in the renge of 0.5–40 2 theta.

2.5.2. FTIR Analysis of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

All obtained PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as pure PLA/TEC film were characterized with FTIR analysis to study possible relaxations between PLA/TEC matrix and pure AC and CV@AC nanohybrid. The FTIR measurements were done in the range of 400 to 4000 cm−1 using an FT/IR-6000 JASCO Fourier-transform spectrometer (JASCO, Interlab, S.A., Athens, Greece).

2.5.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy Images of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

Morphological characteristics of all obtained PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as pure PLA/TEC film were studied with a JEOL JSM-6510 LV SEM Microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.5.4. Mechanical and Thermomechanical Properties of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

All obtained PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as pure PLA/TEC film were measured according to the ASTM D638 method using a Simantzü AX-G 5kNt instrument (Simantzü. Asteriadis, S.A., Athens, Greece) to determine their tensile properties. At least three to five dog bone-shaped samples of all tested films were tensioned, and the stress–strain values were recorded. By using the applicable software (TrapeziumX version 1.5.6, Simantzü, Asteriadis, S.A., Athens, Greece) the elastic modulus E (MPa), ultimate strength σuts (MPa), and %elongation at break ε% Mean values were calculated .

All obtained PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as pure PLA/TEC film were examined for their dynamic mechanical behaviors by using a dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA Q800, TA Instruments, 159 Lukens Drive New Castle, DE, USA) in film tension mode. To evaluate the storage modulus (E′), a temperature range of −20 °C to 60 °C at a rate of 5 K/min, along with a frequency of 1 Hz, was applied.

2.6. Characterization of Active Packaging Properties of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

2.6.1. Water/Oxygen Barrier Properties of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

The water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) values of all PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as PLA//TEC film were determined according to the ASTM E96/E 96M-05 method at 38 °C and 95% RH using a handmade apparatus. For each film at least three to five samples were measured. The obtained Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR) values were transformed to water vapor diffusion coefficient values (D

wv) using the methodology described in detail recently, the Fick’s low theory, and the following equation [

71]:

where WVTR [g/(cm

2.s)] is the water vapor transmission rate, Dx (cm) is the film thickness, and DC (g/cm

3) is the humidity concentration gradient on the two opposite sides of the film.

The oxygen transmission rate (OTR) values of all PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as PLA/TEC film were determined according to ASTM D 3985 method at 23 °C and 0% RH using an oxygen permeation analyzer (O.P.A., 8001, Systech Illinois Instruments Co., Johnsburg, IL, USA). At least three to five samples of each film were measured. Average thickness (Δx) of each film was the average value of thickness values in twelve different points of film. The obtained OTR (ml/m

2/day) values were transformed to oxygen permeability (Pe

O2 – cm/s) values using the methodology described in detail recently and the following equation [

5,

71]:

2.6.2. Desorption Kinetics of PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films -% CV Content and CV Release Rate of PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

The release kinetics of CV release from PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films was studied using a moisture analyzer AXIS AS-60 (AXIS Sp. z o.o. ul. Kartuska 375b, 80-125 Gdańsk, Poland) and the methodology developed and described in detail recently [

37]. For each film three to five samples 500 to 700 mg were placed inside the moisture analyzer, and the mass loss values were recorded as function of time at 70 °C for 1 h. Using the obtained film mass loss values (m

t) as a function of time (t), for each film, the CV desorption kinetic plots were constructed by plotting the values of 1-m

t/m

0 as a function of time. These plots were fitted with pseudosecond order kinetic model to obtain k

2, and q

e mean values for all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films.

2.6.3. Antioxidant Activity of PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

A DPPH radical methanolic standard solution of 2.16 mM (mmol/L) was prepared and used for all experiments. Dilutions were made to obtain 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg/L DPPH solutions. For the preparation of calibration curve the absorbance of these five solutions was measured at 517 nm using a SHIMADZU UV-1900 UV/VIS Spectrometer. The calibration curve of absorbance (y) versus the concentration (x) of [DPPH

•] free radical was found to follow the next equation:

Next, the determination of the concentration required to obtain a 50% antioxidant effect (EC

50) from all obtained PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films was done. 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg of granule film were placed in dark vials in triplicates and 3 mL of standard DPPH radical methanolic solution and 2 mL of acetate buffer 100 mM (pH = 7.10) were added to each vial. All prepared dark vials were kept under dark conditions for 8 hours and next the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. As a blank sample, a vial containing 3 mL of standard DPPH radical methanolic solution and 2 mL of acetate buffer without the addition of any granule film was used. The % inhibition of DPPH radical was calculated using the following equation:

2.6.4. Antibacterial Activity of PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

The antimicrobial activity of all obtained PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films was tested against one Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 6571) and one Gram-negative Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Typhimurium (NCTC 12023) food pathogens.

The experimental procedure followed was based on the agar diffusion method described in detail recently [

37]. The diameters of inhibition zones in the contact area of the films and around them were measured using a Vernier caliper at 0.1 mm accuracy. The experimental procedure was repeated twice while films were measured in triplicate in each repetition.

2.7. Shelf-Life of Fresh Pork Minced Meat Wrapped with PLA/TEC/10CV@AC Film

2.7.1. Packaging Preservation Test of Minced Pork Meat

Minced pork, in portions of approximately 70–80 g each, were aseptically wrapped between two films of PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC10CV@AC samples that were 11 cm in diameter and placed inside the Aifantis company’s commercial wrapping paper without the inner film (coated with plasticized PVC). As a control sample, 80–90 g of minced pork was aseptically wrapped in the commercial opaque packaging paper (without removing the inner coated PVC film) from the Aifantis company. For all tested packaging systems, samples for the 2nd , 4th , 6th , 8th , and 10th day of preservation were prepared and stored at a temperature of 4 ± 1 °C (LG GC-151SA,Weybridge, UK).

2.7.2. Lipid Oxidation of Minced Pork Meat with Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances

Lipid oxidation rates of all minced pork samples during the 10 days of storage were determined by following the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) method according to the methodology described in detail recently [

37].

TBARS was expressed as mg of malondialdehyde (MDA)/kg of the sample using the following equation:

2.7.3. Heme Iron Content

The heme iron content values of all minced pork samples during the 10 days of storage were determined according to the methodology described in detail recently [

37]. The heme iron content in minced pork was calculated using the equation (11):

where A

640 is the absorbance measured at 640 nm and 680 and 0.0882 are constant values in the equation.

2.7.4. Total Viable Count (TVC) of Minced Pork Meat

For the estimation of total viable count (TVC) for all minced pork samples during the 10 days of storage, we used the methodology described in detail recently [

37].

2.7.5. Sensory Analysis of Minced Pork Meat

Color, odor, and texture of wrapped minced pork were evaluated during the 10 days of storage. All the above properties were ranked from 0 (lowest degree of each characteristic in the tested samples) to 5 (highest degree of each characteristic in the tested samples) for each packaging treatment, at each sampling day (2

nd , 4

th , 6

th , 8

th , and 10

th day of storage) by seven panelist/members of the Department of Food Science and Technology experienced in meat sensory evaluation using the conventional descriptive analysis [

72,

73,

74]. A descriptive analysis panel determined the important product characteristics and then evaluated the degree of each characteristic in the tested samples.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All the obtained data from mechanical properties measurements water/oxygen barrier properties measurements, EC50 values, TVC values, TBARS values, heme iron content values, as well as obtained sensory analysis scores values, were subjected to statistical analysis to indicate any statistical differences. The non-parametric statistical Mood’s median test method was chosen to evaluate the significance of difference between the properties’ mean values. Assuming a significance level of p < 0.05, all measurements were conducted using three to five separate samples of each PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC film. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software (v. 28.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of CV@AC Nanohybrid

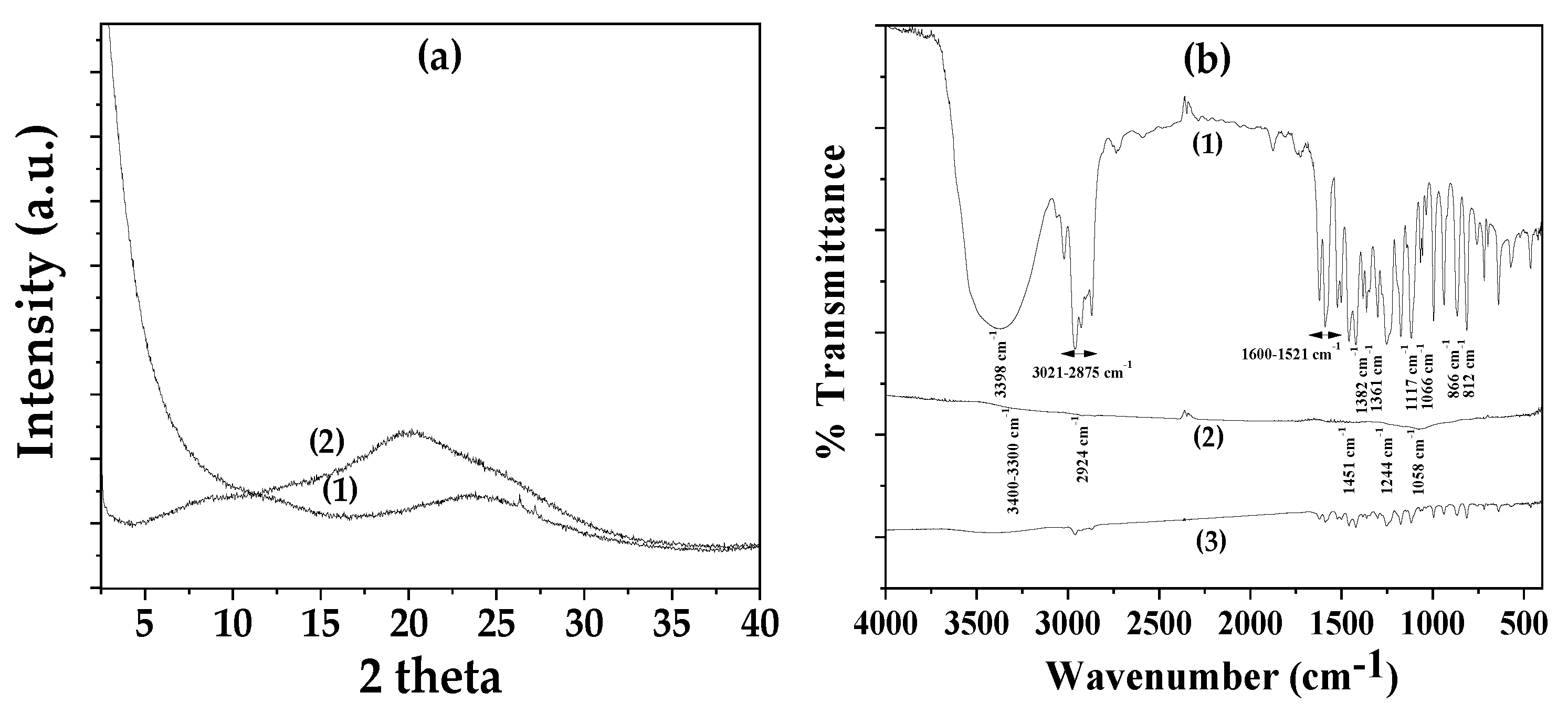

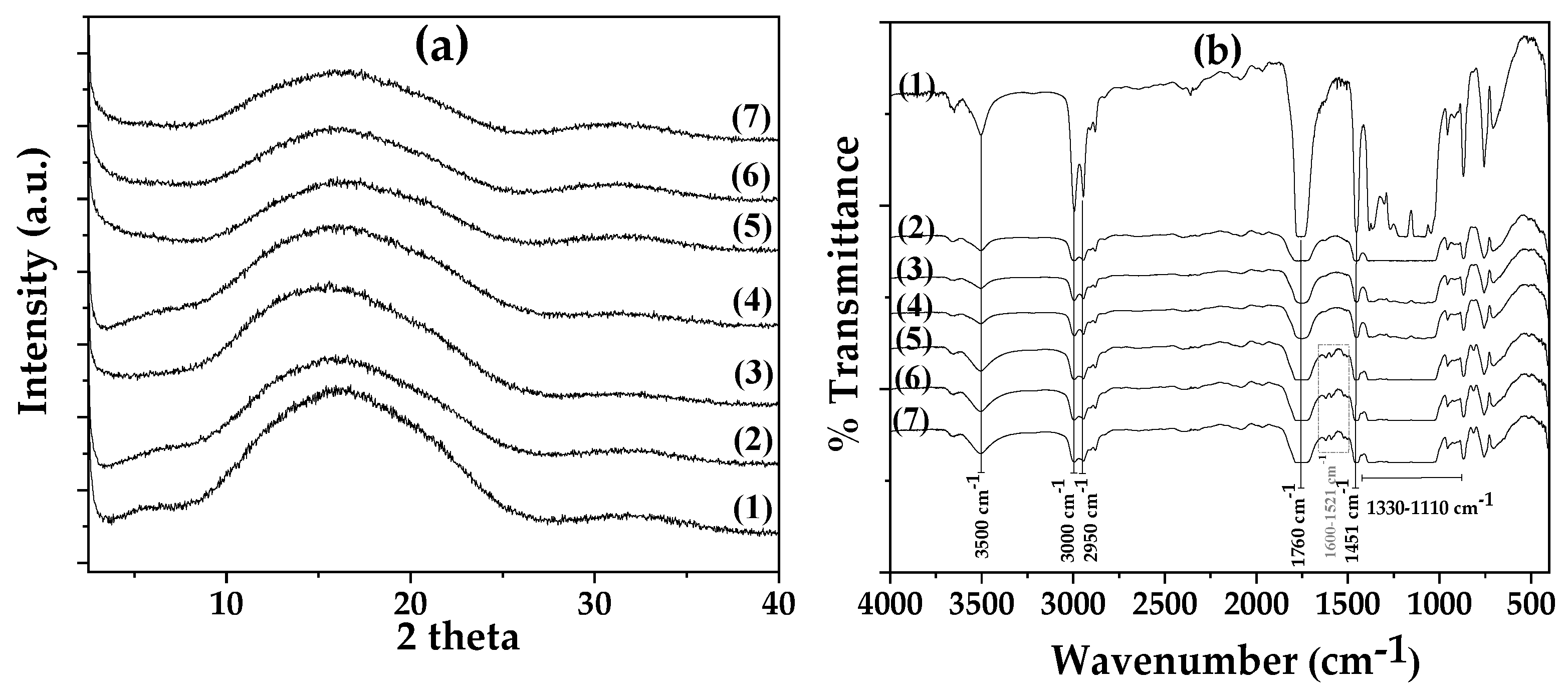

Figure 1(a) presents the XRD plots of AC as received (plot line (1)) and CV@AC nanohybrid (plot line (2)). In

Figure 1(b) the FTIR plots of pure CV (plot line (1)), AC as received (plot line (2)) and CV@AC (plot line (3)) nanohybrid are presented. The XRD plot of AC as received powder (see line (1) in

Figure 1(a)) has a very broad peak at around 24

o 2theta and it is consistent with a typical amorphous material. In the XRD plot of the CV@AC nanohybrid, (see line (2) in

Figure 1(a)) the amorphous broad peak shifted at around 21° 2theta suggesting that the adsorption of CV has subtly influenced the amorphous structure of pure AC.

In the FTIR spectrum of pure CV (see plot line (1) in

Figure 2(b)) the large broad band at 3398 cm

−1 is assigned to the stretching vibration of the O–H functional group of the CV molecule [

37,

75,

76]. The absorption bands at 2875–3021 cm−1 are assigned to the stretching vibrations of aliphatic C–H groups of CV. The denoted absorption bands in the range of 1521–1600 cm

−1 are assigned to C=C bond stretching vibrations of the aromatic ring of CV [

37,

75,

76]. The bands at 1361 and 1382 cm

−1 are assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric vibrations of CV’s isopropyl methyl group respectively [

37,

75,

76]. The bands denoted at 812 and 866 cm

−1 are assigned to the out-of-plane wagging vibrations C–H [

37,

75,

76]. Finally, the bands in the range of 1066–1117 cm

−1 are assigned to the ortho-substituted phenyl group [

37,

75,

76].

The transmittance FTIR plot of AC as received (see plot line (2) in

Figure 2(b)) has small peaks because of the high absorbance of AC’s black color. The band at 3400 cm

−1 could be due to the –OH stretching or the presence of N-H groups [

77,

78]. The peak at 2924 indicates presence of both methylene(–CH

2–) bridges and aromatic C–H stretching vibrations [

77,

78]. The peak at 1451 cm

−1 indicates C=C groups present in carbon. The additional small peaks at 1244 and 1058 cm

−1 indicate the presence of S=O groups in AC [

77,

78].

The FTIR plots of CV@AC (see line (3) in

Figure 1(b)) nanohybrid is a mix plot of CV’s FTIR plot and AC’s FTIR plot. No shift in CV’s reflection is observed suggesting no or low intensity interaction/relaxation between AC and CV adsorbed molecules [

53].

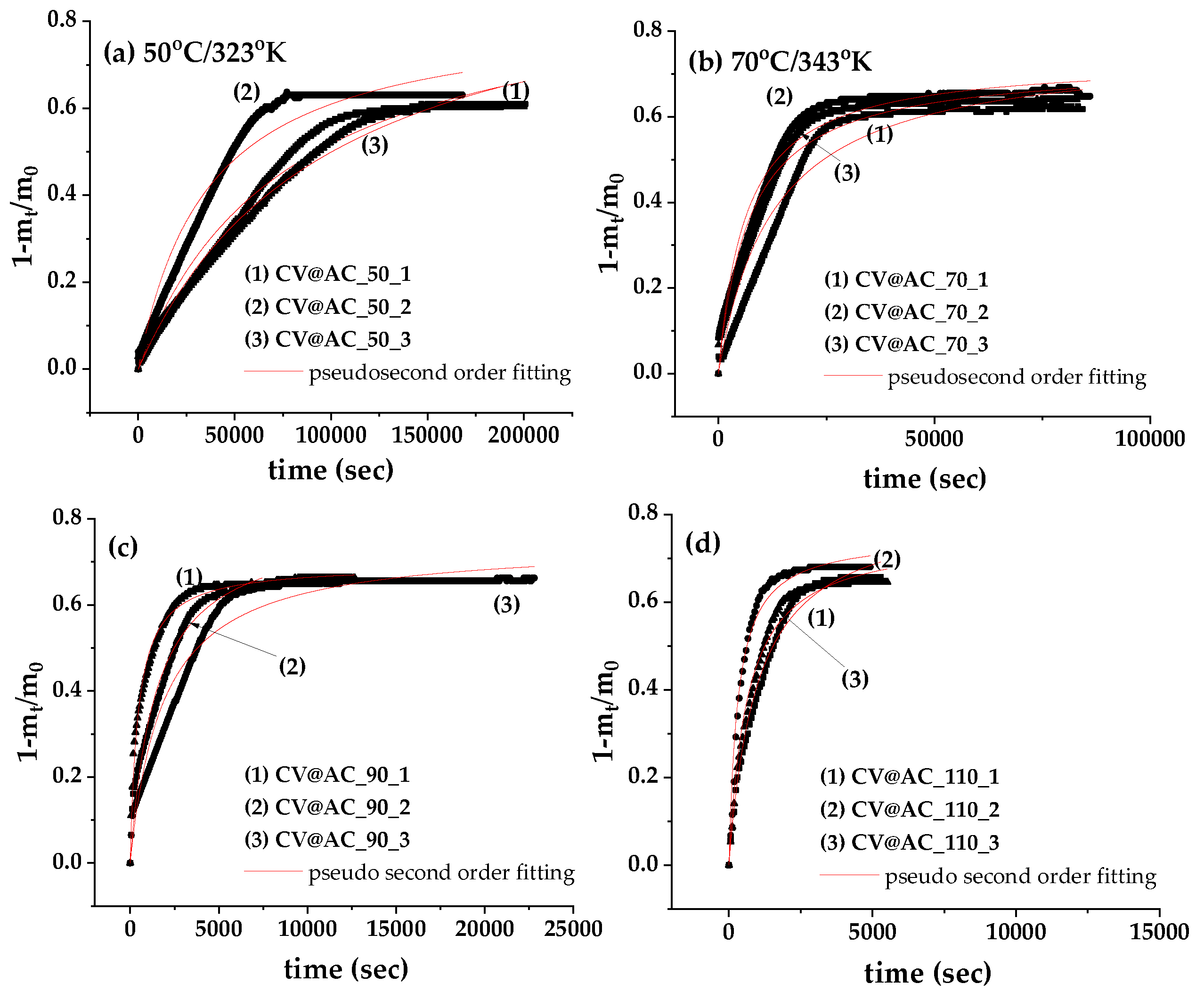

In

Figure 2 there are plotted the recorded (1-m

t/m

0) values as a function of time (t) for CV@AC nanohybrid (in triplicate) at (a)50

oC/323

oK, (b) 70

oC/343

oK, (c) 90

oC/363

oK and (d) 11

oC/383

oK. These plots were fitted with pseudo second order kinetic to calculate the k2 and qe mean values according to equation (1) and are listed in

Table 2.

As it is obtained from

Table 2 by increasing temperature both k

2 and q

e values increased, implying an increase in CV release rate and CV desorbed amount as temperature increases. The % total desorbed amount of CV was calculated to be 70.6 % at 50

oC/323

oK, 72.7% at 70

oC/343

oK, 74.3% at 90

oC/363

oK, and 77.4% at 110

oC/383

oK. Thus, AC is a very promising nanocarrier for such EOs based bioactive compounds as it achieves to release high amounts of CV because of its high specific surface area (≥800 m

2/g).

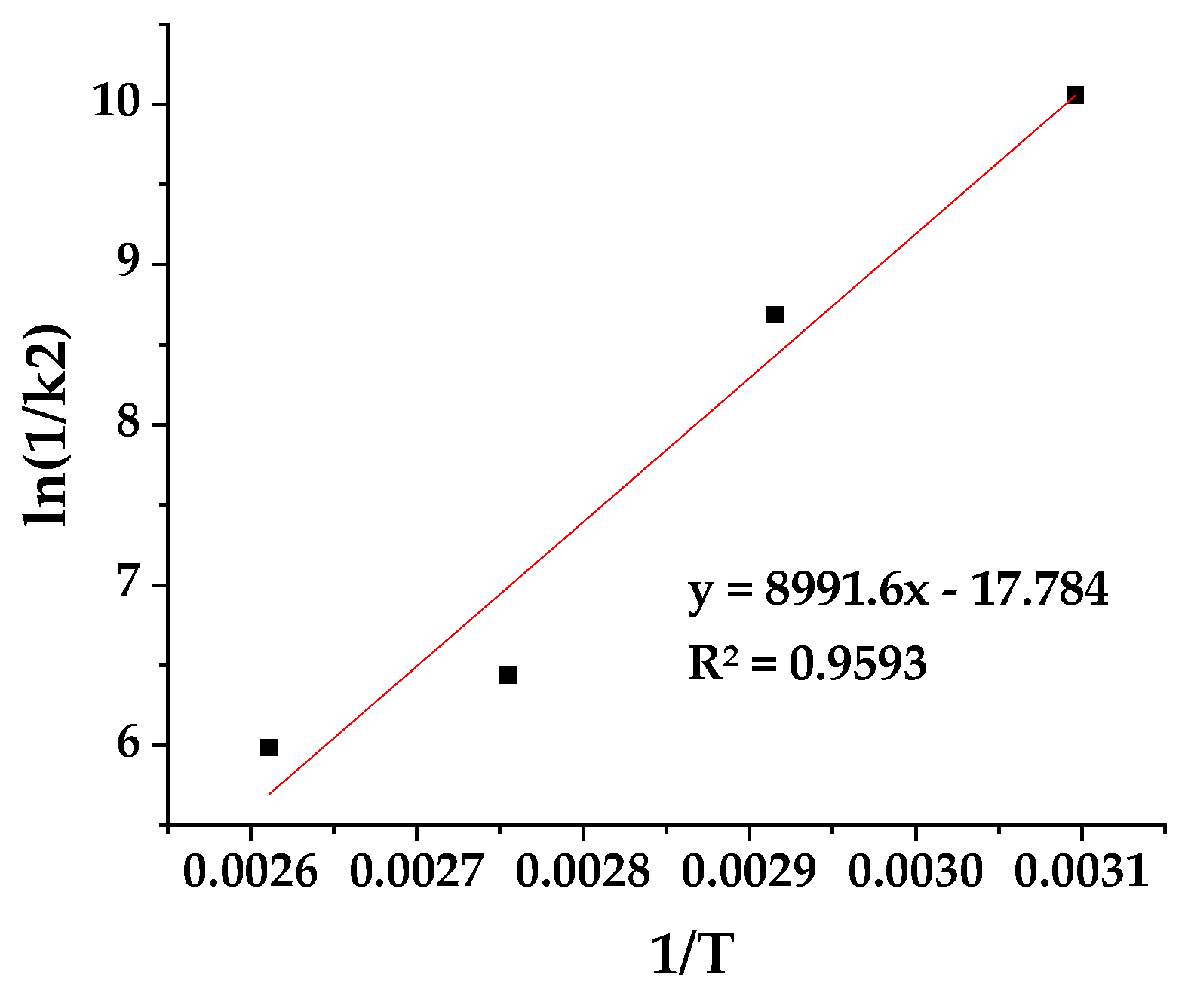

The ln(1/k2) values were determined using the calculated k2 values and are plotted as a function of (1/T) for CV@AC nanohybrid in

Figure 3.

The calculated slope from the linear fitted plot in

Figure 3 was used along with the equations (2) and (3) to determine the CV desorption energy (E0des) for CV@AC nanohybrid. Thus, the calculated E0des is 20.6 Kcal/mol suggesting a chemi-physisorption of CV on AC nanocarrier according to the Arrhenius theory. This value agrees with the pseudo-second order kinetic model followed and is in accordance with no or low intensity interaction/relaxation between AC and CV suggested by XRD and FTIR characterization hereabove [

70].

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

Both the XRD (

Figure 4(a)) and FTIR plots (

Figure 4(b)) of all obtained PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as pure PLA/TEC film for comparison are presented in

Figure 4.

As it is observed in

Figure 4(a), the XRD plot of pure PLA/TEC film (see plot line (1)) has a broad peak at around 15.5° 2-theta, which corresponds to its amorphous crystal phase [

27]. In advance, the addition of pure AC and CV@AC nanohybrid in PLA/TEC matrix does not affect the crystallinity of all obtained PLA/TEC/xAC (see plot lines (2), (3), and (4) in

Figure 4(a)). Also, PLA/TEC/xCV@AC (see plot lines (5), (6), and (7) in

Figure 4(a)) films and all the obtained plots are like that of PLA/TEC pure film and correspond to an amorphous polymer matrix.

In

Figure 4(b), the FTIR plots of pure PLA/TEC film and all obtained PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films are shown for comparison. As it was shown recently TEC is an excellent plasticizer for PLA because of its chemical similarity to PLA’s functional groups [

26,

27,

79]. So, the FTIR plot of pure PLA/TEC film (see line (1) in

Figure 4(b)), is a mixing of PLA and TEC bands of similar factional groups. The bands at 3500 cm

−1 and at 3496 cm

−1 are assigned to the hydroxyl (O–H) group of PLA and TEC correspondingly [

26,

27]. The bands at 3000, 2950, and 3050 cm

−1 and the bands at 2985, 2941, and 2909 cm

−1 are assigned to the asymmetrical and symmetrical stretching of the methyl group (–C–H) of PLA and TEC correspondingly [

26,

27]. The bands at 1760 cm

−1 and 1741 cm

-1 are assigned to the stretching vibration of the carbonyl group (C=O) from the ester unit of PLA and TEC correspondingly [

26,

27]. The bands at 1110–1330 cm

−1 are assigned to the stretching vibrations of the ether (–C–O–) group of PLA and TEC. Finally, the band at 1451 cm

−1 is assigned to the bending vibrations of methyl (–CH

3) group of PLA.

In the FTIR plots of all PLA/TEC/xAC (see plot lines (2), (3), and (4) in

Figure 4(a)), and all PLA/TEC/xAC@CV (see plot lines (5), (6), and (7) in

Figure 4(a)) films the addition of both black colored AC and CV@AC powders decreases the intensity of transmittance. The addition of pure AC does not add any additional peaks in the obtained FTIR plots of all PLA/TEC/xAC (see plot lines (2), (3), and (4) in

Figure 4(a)) films and does not cause any shifting of the PLA/TEC existed peaks suggesting the compatibility of pure AC with PLA/TEC matrix [

79].

In the FTIR plots of all PLA/TEC/xAC@CV (see plot lines (5), (6), and (7) in

Figure 4(a)) films a group of small peaks in the range of 1600-1521 cm

-1 declares the presence of encapsulated CV molecules.

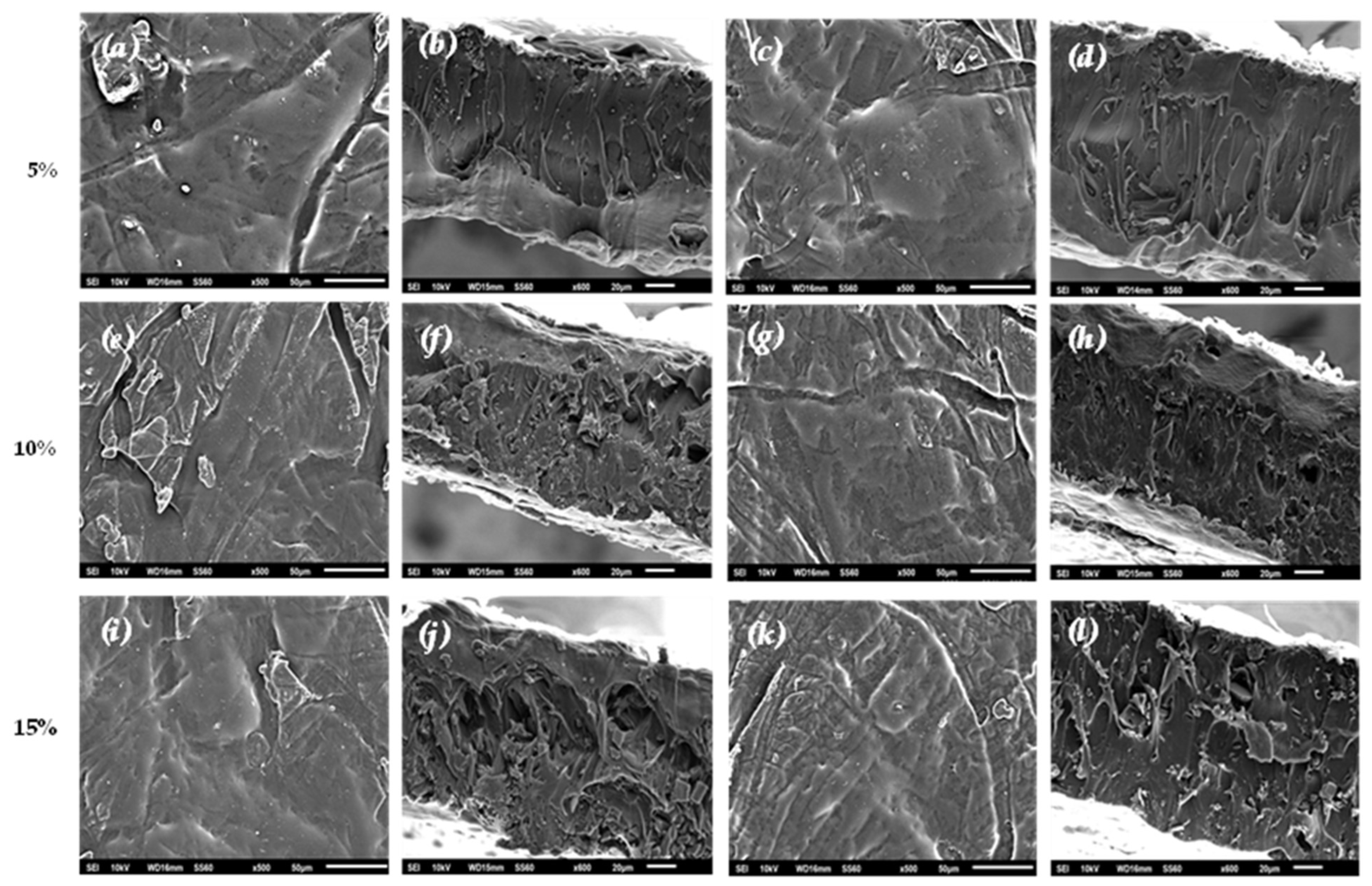

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to investigate the material’s behavior based on the effect of nanohybrid level on films and the surface features. Thus, morpho-logical characteristics of the surface and cross-sections of film samples were evaluated with SEM and are presented in

Figure 5.

The results of the SEM studies of the final nanocomposite films confirmed that the nano-hybrids were homogeneously dispersed, indicating their enhanced compatibility with the polymer matrix, which was the major parameter that improved the films’ behavior.

The surface and relative cross-section images of nanocomposite films of PLA/TEC/AC and PLA/TEC/CV@AC with different ratios (5, 10, 15% wt) of CV@AC nanohybrid and pure AC (white dots can be clearly identified in PLA/TEC matrix) are shown in

Figure 5(a). All films obtained were uniform in thickness. It is evident that increasing the contents (after in-corporation of AC and CV@AC) in the nanocomposites correspondingly increases the degree of dispersion. The SEM micrographs with lower amounts of AC (5%wt) showed surface and cross-section morphology with low dispersion and continuous phase without heterogeneities. Some aggregates and voids were observed in the cross-sectional film where pure AC with a higher concentration (15% wt) had accumulated.

It should be mentioned that based on the SEM (surface and cross-sectional) studies of all samples, a significant difference was observed when the CV@AC hybrid nanostructure was incorporated into the polymer matrix of PLA/TEC as the better interfacial adhesion was evident compared to the corresponding pure AC nanocomposite film.

We can conclude that the optimal nanocomposite active packaging film is achieved at 10 wt% CV@AC concentration in the polymer matrix, as the nanohybrid can be better stabilized without agglomeration with complete mixing and homogeneous morphology.

3.3. Mechanical and Thermomechanical Properties of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

From the obtained stress-strain curves the Elastic Modulus E (MPa), ultimate strength σ

uts (MPa), and % elongation at break values were calculated for all tested films and are listed in

Table 3 for comparison.

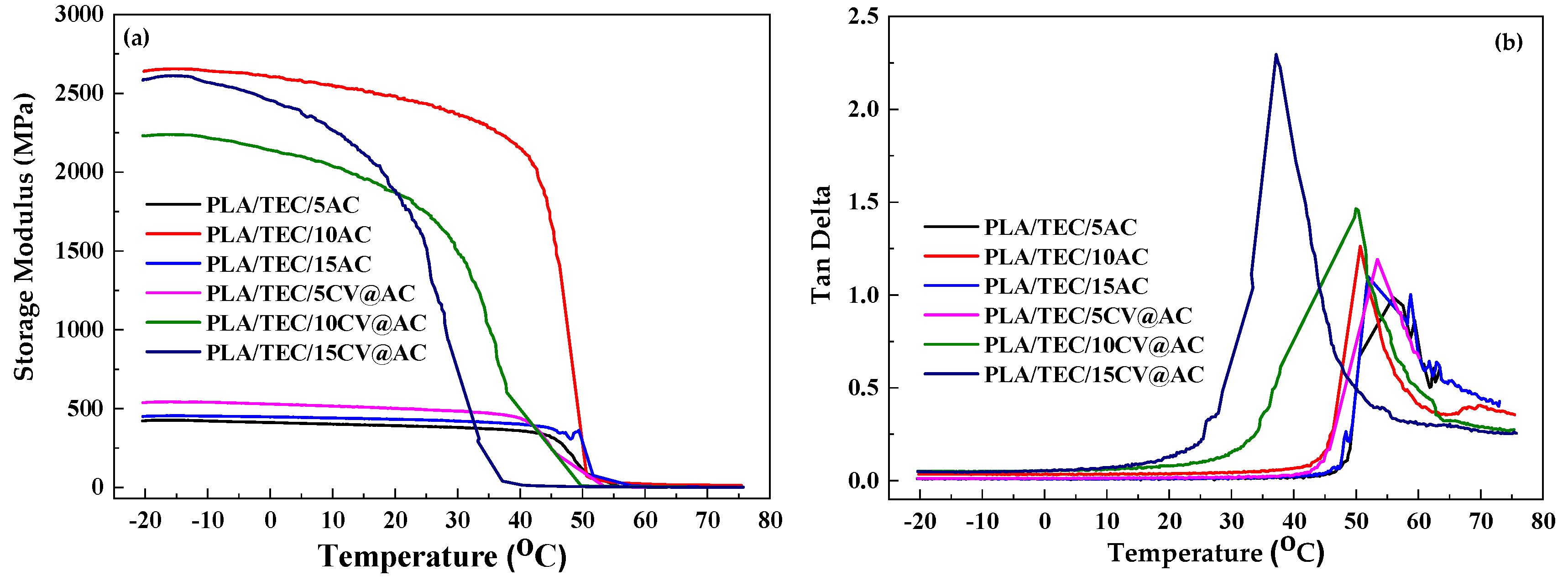

The data of the dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) measurements, storage modulus and tan delta for all tested PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as pure PLA/TEC film are plotted in

Figure 5a,b.

As it is depicted in

Figure 5, medium (10 %wt.) and high (15 %wt.) CV@AC loading contents increase storage modulus of obtained PLA/TEC/10CV@AC and PLA/TEC/15CV@AC composite films, while low (5 %wt.) CV@AC loading does not affect significantly the storage modulus of obtained PLA/TEC/5AC@AC.

3.4. Water/Oxygen Barrier Properties of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

The obtained water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) and oxygen transmission rate (OTR) mean values as well as the calculated water vapor diffusion coefficient(D

wv), and oxygen permeability Pe

O2 mean values of all tested of PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as pure PLA/TEC film are listed In

Table 4.

3.5. Antioxidant Activity of and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

Table 5 shows the calculated EC

50 mean values for all obtained PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films. In

Figures S4–S6, the plots and the linear equations used to calculate the mean EC

50 values for each PLA/TEC/xCV@AC film are presented. In

Figure S6 and

Table S3, the independent sample median test and pairwise comparisons of all the films obtained according to the mean values of EC

50 are listed.

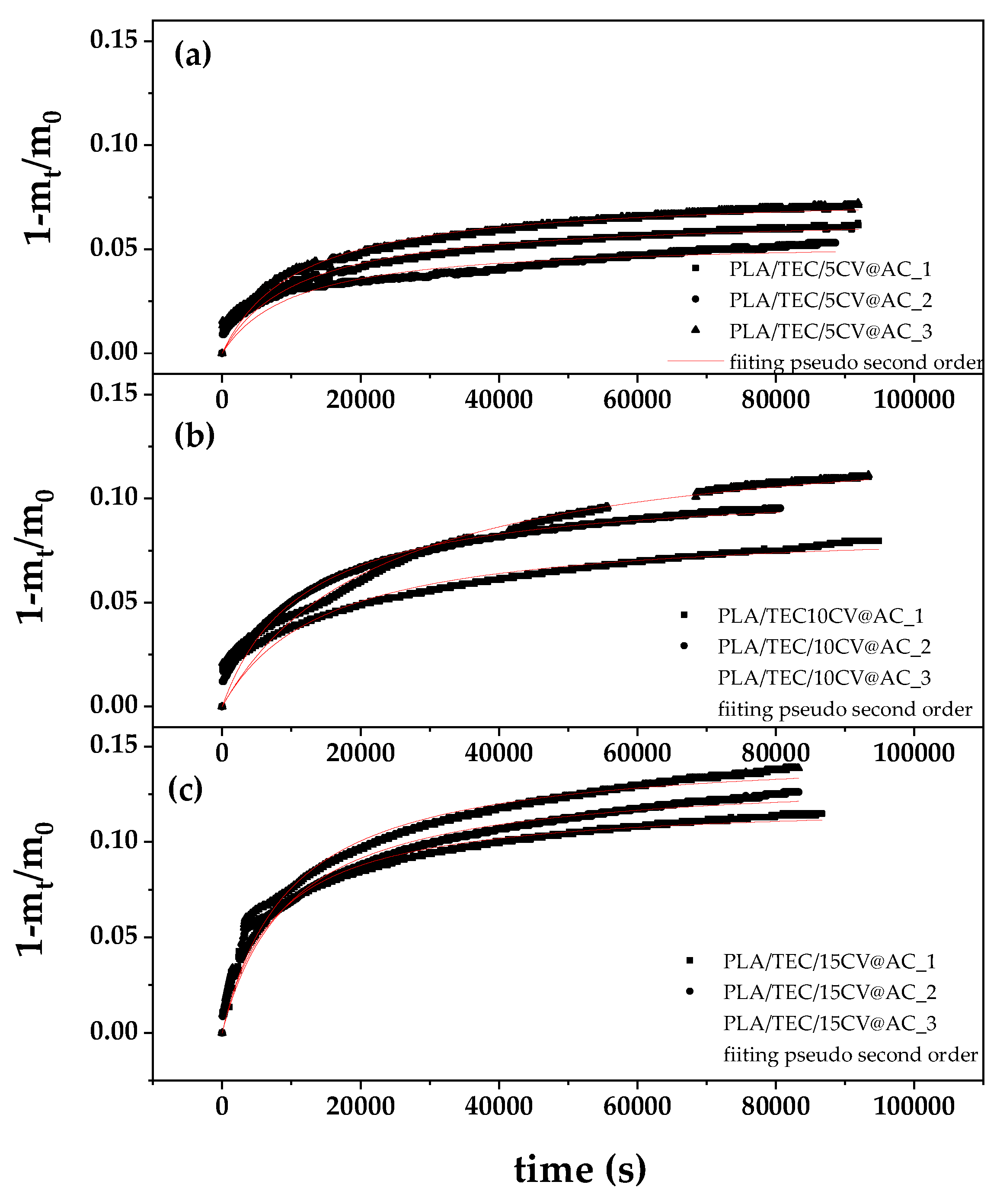

3.7. CV Release Kinetics of PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

The (1-m

t/m

0) values as a function of time (t) for all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films (in triplicate) at 70

oC are plotted in

Figure 6.

The data was fitted with pseudo second order kinetic (see red line plots in

Figure 6) to calculate the k

2 and q

e values using equation (1). The resulted k

2, and q

e mean values are listed in

Table 6 for all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films.

As it is obtained from

Table 6 as CV@AC content increases calculated k

2 values decrease while calculated q

e values increase. This means that by increasing CV@AC nanohybrid loading in PLA/TEC matrix CV release rate decreases and CV loaded content increases. The results reported here for k

2 and q

e values rates are in agreement with similar reports implying that by increasing the loaded EOs derivative amount in a polymer matrix diffusivity of such EOs derivatives molecules inside polymer film decreases [

37,

51,

53,

80]. Comparing the k

2, q

e calculated values for PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films with the recently reported k

2, q

e calculated values for PLA/TEC/xCV@NZ active films it is obtained that PLA/TEC/xCV@AC desorbed higher CV amounts in lower release rates than PLA/TEC/xCV@NZ films [

37]. The calculated k

2, q

e values validate such PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films as packaging materials suitable for increasing the shelf life of long-life foods.

3.8. Antibacterial Activity of PLA/TEC/xCV@AC Films

The results of antibacterial test of all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films against

S. aureus and

S. Typhimurium are listed in

Table 6.

According to

Table 6 all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films exhibited significant antibacterial activity against one Gram-positive,

Staphylococcus aureus, and one Gram-negative,

Salmonella enterica spp. enterica serovar Typhimurium, pathogenic bacteria in the contact area. As recently shown, pure PLA/TEC film exhibited strong antibacterial activity against the Gram- negative pathogenic bacteria in 6 out of 6 replicates but it wasn’t so effective against the Gram-positive showing moderate antibacterial activity in 3 replicates out of 6 replicates [

27]. Thus, it is concluded that the incorporation of CV@AC nanohybrid to obtain PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films has a positive effect on the antibacterial activity.

3.8. Preservation of Fresh Minced Pork Meat Wrapped in PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC Films

3.8.1. Microbiological Evaluation of Minced Pork Wrapped in PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC Films

Table 7 enlists the calculated TVC values for minced pork wrapped with the commercial Ayfantis company package (Control), the PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC films.

As it is obtained in

Table 6 the higher increase rate of TVC values is observed for control sample which reach the limit of acceptance for fresh pork meat according to International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods (ICMFS), 7 log CFU/g, after the 4

th day of storage. Minced pork wrapped with PLA/TEC film exhibits lower TVC increase rate lower than control sample and reaches the 7 log CFU/g after the 6

th day of storage. This result is in accordance with recent report were it was shown that PLA/TEC has antioxidant and antibacterial activity due to the presence of TEC [

27]. PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active film exhibits the lowest TVC increase rate and reaches the 7 log CFU/g value after the 8

th day of storage. This means a shelf-life extension from a microbiological point of view of four days as compared to control sample. Shelf-life extension of minced pork is in equal to this reported recently using PLA/TEC/xCV@NZ active films [

37].

3.8.2. Lipid Oxidation and Heme iron contents of Minced Pork Wrapped in PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC Films

In

Table 8 there are listed the calculated values of TBARS among with the calculated values of heme iron of minced pork wrapped with the commercial Ayfantis company package (Control), the PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC films

Minced pork wrapped in both PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active films exhibited lower TBARS increment rates than minced pork wrapped in the commercial film (control sample), while the lowest TBARS increment rate recorded for minced pork wrapped in the PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active film. Thus, on the 8th day, when minced pork wrapped in the PLA/TEC/10CV@AC film almost exceeded the limit of acceptance for TVC, 7 logCFU/g, minced pork meat had a TBARS value that was 14% lower than that for minced pork meat wrapped with the commercial film.

On the other hand, minced pork wrapped in both PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active films exhibit lower heme iron decrement rates than minced pork wrapped in the commercial film (control sample), while the lowest heme iron decrement rate recorded for minced pork wrapped in the PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active film. This result is in accordance with the lowest TBARS values obtained for the minced pork wrapped in the same packaging system. In other words, PLA/TEC/10CV@AC prevents minced pork from lipid oxidation deterioration and thus maintains a higher heme iron content in minced pork. In addition, a linear correlation between the increasing TBARS and the decreasing heme iron content values is recorded in accordance with all previous reports . Herein, the correlation between TBARS and heme iron content values was estimated using Pearson’s bivariate correlation (−1 to +1) at the confidence level p < 0.05 with respect to storage time. The results of the statistical analysis showed that there is a statistically significant and positive correlation between the two methods throughout the storage period (see

Table S7).

3.8.3. Sensory Analysis of Minced Pork Wrapped in PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC Films

Sensory analysis results of odor, color, and texture of minced pork wrapped in PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC films as well as in a commercial film (control sample) are enlisted in

Table 9 for comparison.

According to statistical analysis results, odor, color, and texture are significantly different for all the tested samples after the 4th day of storage. Minced pork wrapped in the PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active film, recorded odor, color, and texture values are significantly different from the other two samples after the 2nd day of storage. Overall, it can be concluded that both pure PLA/TEC and PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active films succeed in preserving wrapped minced pork in much better and acceptable sensory conditions than commercial packaging paper. Minced pork wrapped in the PLA/TEC/10CV@AC film exhibited the highest sensory analysis values during the 10 days of storage.

4. Discussion

In this work, the development and characterization of a novel CV@AC nanostructure was achieved and the subsequent utilization of this nanostructure as nano-reinforcement and CV control release nanocarrier to develop novel PLA/TEC/xCV@AC (x = 5, 10, 15%wt.) active packaging films. PLA/TEC/xAC (x = 5, 10, 15%wt.) films were also developed for comparison. To the best of our knowledge such CV@AC nanostructure and both PLA/TEC/xAC, PLA/TEC/xCV@AC packaging films are developed, characterized and reported for the first time. By following the vacuum assisted adsorption method high amounts of CV were loaded in AC and the CV desorption kinetics experiments revealed that this CV@AC nanostructure achieve to release high amounts of CV up to 77.4 %wt. This CV release desorbed amount is higher than 61.7 %wt. of the one reported recently for CV@NZ nanostructure [

37]. Desorption kinetic experiments also suggest chemi-physisorption of CV on AC nanocarrier in accordance with XRD, FTIR characterization of CV@AC nanostructure.

For PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC (x = 5, 10, 15%wt.) active packaging films, SEM studies confirmed that both pure AC and the CV@AC nanostructure were homogeneously dispersed and indicate their enhanced compatibility with the PLA/TEC matrix. Tensile properties studies show that pure AC enhances ultimate strength and decreases ductility of obtained PLA/TEC/xAC films while CV@AC nanostructure enhances ultimate strength and preserves the ductility of obtained PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films. This means that pure AC serves as reinforcement of the PLA/TEC matrix while CV@AC nanostructure serves as both reinforcement and plasticizer in PLA/TEC matrix. Increase of mechanical strength by increasing AC loaded contents on PLA/TEC matrix is in accordance with previous reports where activated carbon added in chitosan, starch and cellulose based packaging films [

81,

82,

83]. Addition of both pure AC and CV@AC nanostructure in PLA/TEC matrix increase water barrier properties in accordance with previous reports where AC was added in starch and chitosan based films [

81,

84]. On the other hand, oxygen barrier increases for lower (5%wt.) both AC and CV@AC loaded contents, remains constant for medium (10%wt.) AC and CV@AC loaded contents and decreases for higher (15%wt.) AC and CV@AC loaded contents. No data are available in the literature on the oxygen barrier properties of AC-based films for comparison.CV release desorption kinetics of PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films reveal that increment of CV@AC loaded contents decreases CV release rates in accordance with SEM studies which show that increase of CV@AC loaded contents increase particle aggregation. This CV@AC aggregation decreases CV diffusivity inside PLA/TEC matrix and thus, the highest antioxidant activity (lowest EC

50 value) recorded for PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active film.

Overall, considering that the aim of this study was to add the CV@AC nanohybrid to the PLA/TEC matrix to obtain the highest possible CV content (%wt.) and at the same time to improve as many packaging properties as possible, we conclude that PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active film is optimal. So, PLA/TEC/10CV@AC film has: (i) 277% higher ultimate strength than PLA/TEC and remains ductile, (ii) 72% higher water barrier than PLA/TEC film, (iii) almost the same oxygen barrier properties with PLA/TEC film, (iv) low CV release rate (k2 value), (v) the highest antioxidant activity, (vi) significant antibacterial activity against Gram+ and Gram- pathogens and it is self-healable (see Video S1 in supplementary materials). Minced pork wrapped with this film extends its shelf life for four days, compared to minced pork wrapped in commercial paper as it was shown by the recorded TVC values. At the same time minced pork wrapped with PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active film show the lowest lipid oxidation rates (TBARS values), keep the highest contents of heme iron and sensory characteristics after 10 days of storage.

This work among with a recently reported study are state of the art studies how EOs derivatives such as CV can be encapsulated in cheap, naturally abundant and edible nanocarriers such as NZ and AC and dispersed in biodegradable self-healable active packaging films with control release antioxidant/antibacterial properties for fresh meat shelf life extension [

80]. This technology is promising and advantageous over the direct use of EOs and their derivatives for meat preservation, as it requires lower amounts of EOs and results in an extension of the shelf life of the meat with more acceptable aesthetic characteristics such as color, odor and texture. [

85,

86,

87,

88,

89]. This technology is also advantageous over the direct incorporation of CV into PLA films, as it results in slower release rates and longer meat shelf life [

90].

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study provides a novel biodegradable, self-healable active packaging film by dispersing 10 %wt. CV@AC nanohybrid in a PLA/TEC matrix via extrusion molding method. This film with code name PLA/TEC/10CV@AC showed improved antioxidant/antibacterial activity, and slow CV release rates and succeeded in extending the shelf life of fresh minced pork, according to TVC values, for four days. Simultaneously, this film delays the lipid oxidation, provides higher nutritional values of fresh minced pork, as revealed by the determination of TBARS and heme iron content correspondingly, and provides higher and acceptable sensory characteristics than commercial packaging paper. Thus, this film has a great potential to be used as novel biodegradable, self-healable active film to extend the shelf life of fresh meat products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Independent sample median test for E, σ, and %ε; Figure S2: Independent sample median test for D

wv and Pe

O2; Figure S3: Equations for the determination of EC

50 in PLA/TEC/5CV@AC films; Figure S4: Equations for the determination of EC

50 in PLA/TEC/10CV@AC films; Figure S5: Equations for the determination of EC

50 in PLA/TEC/15CV@AC films; Figure S6: Independent sample median test of EC

50 values; Figure S7: Independent sample median test of TVC during storage time; Figure S8: Independent sample median test of TBARS during storage time; Figure S9: Independent sample median test of heme iron content during storage time; Figure S10: Independent sample median test of odor during storage time; Figure S11: Independent sample median test of color during storage time; Figure S12: Independent sample median test of texture during storage time; Table S1: Pairwise comparisons of the different treatments according to the mean values of E, σ, and %ε for all PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films; Table S2: WVTR, Dwv, O.T.R., and PeO

2 values for all PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films as well as for pure PLA/TEC films; Table S3: Independent sample median test summary of the different treatments according to the mean values of EC

50; Table S4: Pairwise comparisons of the different treatments according to the mean values of TVC during storage time; Table S5: Pairwise comparisons of the different treatments according to the mean values of TBARS during storage time; Table S6: Pairwise comparisons of the different treatments according to the mean values of heme iron content during storage time; Table S7: Pearson’s correlation between TBARS and heme iron content during storage time; Table S8: Pairwise comparisons of the different treatments according to the mean values of odor during storage time; Table S9: Pairwise comparisons of the different treatments according to the mean values of color during storage time; Table S10: Pairwise comparisons of the different treatments according to the mean values of texture during storage time; Video S1: Self-healing test of PLA/TEC/10CV@AC active film.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K.K., A.E.G., and C.E.S.; methodology, V.K.K., A.E.G., C.P., and C.E.S.; software, D.M. and A.K.-M.; validation, A.E.G., A.A., N.E.Z., and C.E.S.; formal analysis, N.D.A. and A.A.L.; investigation, V.K.K., N.D.A., D.M., and A.K.-M.; resources, A.E.G., A.A., N.E.Z., C.P., and C.E.S.; data curation, V.K.K., and A.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, V.K.K., A.E.G. and C.E.S.; writing—review and editing, V.K.K., A.A.L., A.E.G., and C.E.S.; visualization, V.K.K., A.A.L., A.E.G., and C.E.S.; supervision, A.E.G., and C.E.S.; project administration, A.E.G. and C.E.S.; and funding acquisition, A.E.G.;C.P.; and C.E.S.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A Review of the Global Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Sustainable Mitigation Measures. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabric, A.J. The Climate Change Crisis: A Review of Its Causes and Possible Responses. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Ogunseitan, O.A.; Wong, M.H.; Tang, Y. Sustainable Materials Alternative to Petrochemical Plastics Pollution: A Review Analysis. Sustainable Horizons 2022, 2, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.C. Greenhouse Effect and Climate Change: Scientific Basis and Overview. Renewable Energy 1993, 3, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, S.; Osman, A.I.; Doran, J.; Rooney, D.W. Strategies for Mitigation of Climate Change: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2020, 18, 2069–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Chen, L.; McClements, D.J.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, F.; Miao, M.; Tian, Y.; Jin, Z. Starch-Based Biodegradable Packaging Materials: A Review of Their Preparation, Characterization and Diverse Applications in the Food Industry. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 114, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Ji, N.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Sun, Q. Bioactive and Intelligent Starch-Based Films: A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 116, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Vázquez, M. Applications of Chitosan as Food Packaging Materials. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 36: Chitin and Chitosan: Applications in Food, Agriculture, Pharmacy, Medicine and Wastewater Treatment; Crini, G., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 81–123 ISBN 978-3-030-16581-9.

- Liu, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Sameen, D.E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, R.; Dai, J.; Li, S.; Qin, W. A Review of Cellulose and Its Derivatives in Biopolymer-Based for Food Packaging Application. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 112, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, N.; Majid, I.; Nayik, G.A. Bioplastics and Food Packaging: A Review. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2015, 1, 1117749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, S.; Milanese, D.; Gallichi-Nottiani, D.; Cavazza, A.; Sciancalepore, C. Poly(Lactic Acid) and Its Blends for Packaging Application: A Review. Clean Technologies 2023, 5, 1304–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetha, T.A.; Bora, A.; Mohanrasu, K.; Balaji, P.; Raja, R.; Ponnuchamy, K.; Muthusamy, G.; Arun, A. A Comprehensive Review on Polylactic Acid (PLA) – Synthesis, Processing and Application in Food Packaging. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 234, 123715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, R.; Kumar, V.; Bhunia, H.; Upadhyay, S.N. Synthesis of Poly(Lactic Acid): A Review. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part C 2005, 45, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.O.; de Smidt, O. Lactic Acid: A Comprehensive Review of Production to Purification. Processes 2023, 11, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Banat, F.; Alsafar, H.; Hasan, S.W. An Overview of Biodegradable Poly (Lactic Acid) Production from Fermentative Lactic Acid for Biomedical and Bioplastic Applications. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 14, 3057–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Södergård, A.; Stolt, M. Properties of Lactic Acid Based Polymers and Their Correlation with Composition. Progress in Polymer Science 2002, 27, 1123–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E. 7 - Extrusion of Biopolymers for Food Applications. In Advances in Biopolymers for Food Science and Technology; Pal, K., Sarkar, P., Cerqueira, M.Â., Eds.; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 137–169 ISBN 978-0-443-19005-6.

- O’Loughlin, J.; Doherty, D.; Herward, B.; McGleenan, C.; Mahmud, M.; Bhagabati, P.; Boland, A.N.; Freeland, B.; Rochfort, K.D.; Kelleher, S.M.; et al. The Potential of Bio-Based Polylactic Acid (PLA) as an Alternative in Reusable Food Containers: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamps, B.; Buntinx, M.; Peeters, R. Seal Materials in Flexible Plastic Food Packaging: A Review. Packaging Technology and Science 2023, 36, 507–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and Mechanical Properties of PLA, and Their Functions in Widespread Applications — A Comprehensive Review. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Dong, H.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J. Plasticization of Poly (Lactic) Acid Film as a Potential Coating Material. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 108, 022062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.G.A.; da Silva, M.A.; dos Santos, L.O.; Beppu, M.M. Natural-Based Plasticizers and Biopolymer Films: A Review. European Polymer Journal 2011, 47, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieng, B.W.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Then, Y.Y.; Loo, Y.Y. Epoxidized Vegetable Oils Plasticized Poly(Lactic Acid) Biocomposites: Mechanical, Thermal and Morphology Properties. Molecules 2014, 19, 16024–16038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mele, G.; Bloise, E.; Cosentino, F.; Lomonaco, D.; Avelino, F.; Marcianò, T.; Massaro, C.; Mazzetto, S.E.; Tammaro, L.; Scalone, A.G.; et al. Influence of Cardanol Oil on the Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid) Films Produced by Melt Extrusion. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Li, Y.; Gong, M.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Z.; Fang, Q.; Li, X. An Environmentally Sustainable Plasticizer Toughened Polylactide. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 11643–11651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiza, M.; Benaniba, M.T.; Massardier-Nageotte, V. Plasticizing Effects of Citrate Esters on Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid). Journal of Polymer Engineering 2016, 36, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabagias, V.K.; Giannakas, A.E.; Andritsos, N.D.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Leontiou, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E. Νovel Polylactic Acid/Tetraethyl Citrate Self-Healable Active Packaging Films Applied to Pork Fillets’ Shelf-Life Extension. Polymers 2024, 16, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E. Plant Extracts-Based Food Packaging Films. In Natural Materials for Food Packaging Application; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2023; pp. 23–49 ISBN 978-3-527-83730-4.

- Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Rehman, A.; Mahdi, A.A.; Al-Ansi, W.; Wei, M.; Yanyu, Z.; Phyo, H.M.; Galeboe, O.; Yao, W. Application of Essential Oils as Preservatives in Food Systems: Challenges and Future Prospectives – a Review. Phytochem Rev 2022, 21, 1209–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angane, M.; Swift, S.; Huang, K.; Butts, C.A.; Quek, S.Y. Essential Oils and Their Major Components: An Updated Review on Antimicrobial Activities, Mechanism of Action and Their Potential Application in the Food Industry. Foods 2022, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angane, M.; Swift, S.; Huang, K.; Butts, C.A.; Quek, S.Y. Essential Oils and Their Major Components: An Updated Review on Antimicrobial Activities, Mechanism of Action and Their Potential Application in the Food Industry. Foods 2022, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological Effects of Essential Oils – A Review. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpena, M.; Nuñez-Estevez, B.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Prieto, M.A. Essential Oils and Their Application on Active Packaging Systems: A Review. Resources 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacha, J.S.; Ofoedu, C.E.; Xiao, K. Essential Oil-Based Active Polymer-Based Packaging System: A Review of Its Effect on the Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Sensory Properties of Beef and Chicken Meat. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2022, 46, e16933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAFUS, A. A Food Additive Database. Centre for Food Safety, and Applied Nutrition.; US Food, and Drug Administration Washington, DC:, 2006.

- Council, E.P. and Regulation (EC) No 2232/96 the European Parliament, and of the Council on 28 October 1996, Commission Decision of 23 February 1999 Adopting a Register of Flavouring Substances Used in or on Foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Commun. 1996, 39, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Karabagias, V.K.; Giannakas, A.E.; Andritsos, N.D.; Leontiou, A.A.; Moschovas, D.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Proestos, C.; Salmas, C.E. Shelf Life of Minced Pork in Vacuum-Adsorbed Carvacrol@Natural Zeolite Nanohybrids and Poly-Lactic Acid/Triethyl Citrate/Carvacrol@Natural Zeolite Self-Healable Active Packaging Films. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan Tas, B.; Sehit, E.; Erdinc Tas, C.; Unal, S.; Cebeci, F.C.; Menceloglu, Y.Z.; Unal, H. Carvacrol Loaded Halloysite Coatings for Antimicrobial Food Packaging Applications. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2019, 20, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, M.; Manso, S.; Silva, F.; Cardoso, L.; Salafranca, J.; Nerín, C.; Alfonso, M.J.; Caballero, M.Á. New Active Packaging Based on Encapsulated Carvacrol, with Emphasis on Its Odour Masking Strategies. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, A.; Navarro-Martínez, A.; Garre, A.; Iguaz, A.; Maldonado-Guzmán, P.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Kinetics of Carvacrol Release from Active Paper Packaging for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables under Conditions of Open and Closed Package. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2023, 37, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krümmel, A.; Pagno, C.H.; Malheiros, P. da S. Active Films of Cassava Starch Incorporated with Carvacrol Nanocapsules. Foods 2024, 13, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroque, D.A.; de Aragão, G.M.F.; de Araújo, P.H.H.; Carciofi, B.A.M. Active Cellulose Acetate-Carvacrol Films: Antibacterial, Physical and Thermal Properties. Packaging Technology and Science 2021, 34, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozogul, F.; Çetinkaya, A.; EL Abed, N.; Kuley, E.; Durmus, M.; Ozogul, İ.; Ozogul, Y. The Effect of Carvacrol, Thymol, Eugenol and α-Terpineol in Combination with Vacuum Packaging on Quality Indicators of Anchovy Fillets. Food Bioscience 2024, 59, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, L.; Roustom, R.; Abiad, M.G.; El-Obeid, T.; Savvaidis, I.N. Combined Effects of Thymol, Carvacrol and Packaging on the Shelf-Life of Marinated Chicken. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2019, 291, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokoglu, N. Novel Natural Food Preservatives and Applications in Seafood Preservation: A Review. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2019, 99, 2068–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusuma, G.D.; Barabadi, M.; Tan, J.L.; Morton, D.A.V.; Frith, J.E.; Lim, R. To Protect and to Preserve: Novel Preservation Strategies for Extracellular Vesicles. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Singh, S.; Bahmid, N.A.; Sasidharan, A. Applying Innovative Technological Interventions in the Preservation and Packaging of Fresh Seafood Products to Minimize Spoilage - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, V.I.; Parente, J.F.; Marques, J.F.; Forte, M.A.; Tavares, C.J. Microencapsulation of Essential Oils: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, S.K.; Parikh, J.K. Advances and Trends in Encapsulation of Essential Oils. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 635, 122668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E. 7 - Bionanocomposites with Hybrid Nanomaterials for Food Packaging Applications. In Advances in Biocomposites and their Applications; Karak, N., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Composites Science and Engineering; Woodhead Publishing, 2024; pp. 201–225 ISBN 978-0-443-19074-2.

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Moschovas, D.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karabagias, I.K.; Baikousi, M.; Georgopoulos, S.; Leontiou, A.; Katerinopoulou, K.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; et al. Development, Characterization, and Evaluation as Food Active Packaging of Low-Density-Polyethylene-Based Films Incorporated with Rich in Thymol Halloysite Nanohybrid for Fresh “Scaloppini” Type Pork Meat Fillets Preservation. Polymers 2023, 15, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Baikousi, M.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karageorgou, I.; Iordanidis, G.; Emmanouil-Konstantinos, C.; Leontiou, A.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Kehayias, G.; et al. Low-Density Polyethylene-Based Novel Active Packaging Film for Food Shelf-Life Extension via Thyme-Oil Control Release from SBA-15 Nanocarrier. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Karabagias, V.K.; Moschovas, D.; Leontiou, A.; Karabagias, I.K.; Georgopoulos, S.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Zaharioudakis, K.; Andritsos, N.; Kehayias, G.; et al. Thymol@activated Carbon Nanohybrid for Low-Density Polyethylene-Based Active Packaging Films for Pork Fillets’ Shelf-Life Extension. Foods 2023, 12, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.H.; Trigueiro, P.; Souza, J.S.N.; de Carvalho, M.S.; Osajima, J.A.; da Silva-Filho, E.C.; Fonseca, M.G. Montmorillonite with Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents, Packaging, Repellents, and Insecticides: An Overview. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2022, 209, 112186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Zuñiga, J.N.; Sánchez-Valdes, S.; Ramírez-Vargas, E.; Guillen, L.; Ramos-deValle, L.F.; Graciano-Verdugo, A.; Uribe-Calderón, J.A.; Valera-Zaragoza, M.; Lozano-Ramírez, T.; Rodríguez-González, J.A.; et al. Controlled Release of Essential Oils Using Laminar Nanoclay and Porous Halloysite / Essential Oil Composites in a Multilayer Film Reservoir. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2021, 316, 110882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh, D.; Majdoub, H.; Darder, M. An Overview of Clay-Polymer Nanocomposites Containing Bioactive Compounds for Food Packaging Applications. Applied Clay Science 2022, 216, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.C.; Valencia, G.A.; López Córdoba, A.; Ortega-Toro, R.; Ahmed, S.; Gutiérrez, T.J. Zeolites for Food Applications: A Review. Food Bioscience 2022, 46, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaemsanit, S.; Matan, N.; Matan, N. Activated Carbon for Food Packaging Application: Review. Walailak Journal of Science and Technology (WJST) 2018, 15, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, H.; Ayed, A.; Srasra, M.; Attia, S.; Srasra, E.; Bouhtoury, F.C.-E.; Tabbene, O.; Saad, H.; Ayed, A.; Srasra, M.; et al. New Trends in Clay-Based Nanohybrid Applications: Essential Oil Encapsulation Strategies to Improve Their Biological Activity. In Nanoclay - Recent Advances, New Perspectives and Applications; IntechOpen, 2022 ISBN 978-1-80356-558-3.

- Lu, W.; Cui, R.; Zhu, B.; Qin, Y.; Cheng, G.; Li, L.; Yuan, M. Influence of Clove Essential Oil Immobilized in Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles on the Functional Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid) Biocomposite Food Packaging Film. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 11, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos, G.; Baikousi, M.; Kostas, V.; Papantoniou, M.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Zbořil, R.; Karakassides, M.A.; Salmas, C.E. Nanoporous Activated Carbon Derived via Pyrolysis Process of Spent Coffee: Structural Characterization. Investigation of Its Use for Hexavalent Chromium Removal. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 8812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitura, K.; Kornacka, J.; Kopczyńska, E.; Kalisz, J.; Czerwińska, E.; Affeltowicz, M.; Kaczorowski, W.; Kolesińska, B.; Frączyk, J.; Bakalova, T.; et al. Active Carbon-Based Nanomaterials in Food Packaging. Coatings 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhan, A.; Muthukumarappan, K.; Wei, L.; Van Den Top, T.; Zhou, R. Development of an Activated Carbon-Based Nanocomposite Film with Antibacterial Property for Smart Food Packaging. Materials Today Communications 2020, 23, 101124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmas, C.E.; Leontiou, A.; Kollia, E.; Zaharioudakis, K.; Kopsacheili, A.; Avdylaj, L.; Georgopoulos, S.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karydis-Messinis, A.; Kehayias, G.; et al. Active Coatings Development Based on Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol Polymeric Matrix Incorporated with Thymol Modified Activated Carbon Nanohybrids. Coatings 2023, 13, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillin, K.W.; Belcher, J.N. 6 - Advances in the Packaging of Fresh and Processed Meat Products. In Advances in Meat, Poultry and Seafood Packaging; Kerry, J.P., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing, 2012; pp. 173–204 ISBN 978-1-84569-751-8.

- Saleh, T.A. Chapter 3 - Kinetic Models and Thermodynamics of Adsorption Processes: Classification. In Interface Science and Technology; Saleh, T.A., Ed.; Surface Science of Adsorbents and Nanoadsorbents; Elsevier, 2022; Vol. 34, pp. 65–97.

- Asimakopoulos, G.; Baikousi, M.; Salmas, C.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Zboril, R.; Karakassides, M.A. Advanced Cr(VI) Sorption Properties of Activated Carbon Produced via Pyrolysis of the “<i>Posidonia Oceanica”</i> Seagrass. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 405, 124274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, J. Theorie der Adsorption und verwandter Erscheinungen. Z. Physik 1924, 26, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopf, D.A.; Ammann, M. Technical Note: Adsorption and Desorption Equilibria from Statistical Thermodynamics and Rates from Transition State Theory. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2021, 21, 15725–15753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrhenius, S. Über die Dissociationswärme und den Einfluss der Temperatur auf den Dissociationsgrad der Elektrolyte. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 1889, 4U, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Leontiou, A.; Moschovas, D.; Baikousi, M.; Kollia, E.; Tsigkou, V.; Karakassides, A.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Proestos, C. Performance of Thyme Oil@Na-Montmorillonite and Thyme Oil@Organo-Modified Montmorillonite Nanostructures on the Development of Melt-Extruded Poly-L-Lactic Acid Antioxidant Active Packaging Films. Molecules 2022, 27, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 11035:1994(En), Sensory Analysis — Identification and Selection of Descriptors for Establishing a Sensory Profile by a Multidimensional Approach Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:11035:ed-1:v1:en (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Heymann, H.; Machado, B.; Torri, L.; Robinson, A. l. How Many Judges Should One Use for Sensory Descriptive Analysis? Journal of Sensory Studies 2012, 27, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assanti, E.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karabagias, I.K.; Badeka, A.; Kontominas, M.G. Shelf Life Evaluation of Fresh Chicken Burgers Based on the Combination of Chitosan Dip and Vacuum Packaging under Refrigerated Storage. J Food Sci Technol 2021, 58, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, A.C.S.; De, G.C.R. Traceability of Active Compounds of Essential Oils in Antimicrobial Food Packaging Using a Chemometric Method by ATR-FTIR. American Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2017, 8, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M.G.; Hekmati, M.; Esmaeili, D.; Ziarati, P.; Yousefi, M. Evaluation and Efficacy Modified Carvacrol and Anti-Cancer Peptide Against Cell Line Gastric AGS. Int J Pept Res Ther 2022, 28, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmann, D.; Saal, L.; Zietzschmann, F.; Mai, M.; Altmann, K.; Al-Sabbagh, D.; Schumann, P.; Ruhl, A.S.; Jekel, M.; Braun, U. Characterization of Activated Carbons for Water Treatment Using TGA-FTIR for Analysis of Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups. Appl Water Sci 2022, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, H.; Demiral, İ. Surface Properties of Activated Carbon Prepared from Wastes. Surface and Interface Analysis 2008, 40, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, U.C.; Fragouli, D.; Bayer, I.S.; Zych, A.; Athanassiou, A. Effect of Green Plasticizer on the Performance of Microcrystalline Cellulose/Polylactic Acid Biocomposites. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 3071–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E.; Karabagias, V.K.; Moschovas, D.; Karabagias, I.K.; Gioti, C.; Georgopoulos, S.; Leontiou, A.; Kehayias, G.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. Development and Evaluation of a Novel-Thymol@Natural-Zeolite/Low-Density-Polyethylene Active Packaging Film: Applications for Pork Fillets Preservation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaśniewska, A.; Świetlicki, M.; Prószyński, A.; Gładyszewski, G. Physical Properties of Starch/Powdered Activated Carbon Composite Films. Polymers 2021, 13, 4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Luo, F.; Zhai, M.; Mitomo, H.; Yoshii, F. Study on CM-Chitosan/Activated Carbon Hybrid Gel Films Formed with EB Irradiation. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2008, 77, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhan, A.; Muthukumarappan, K.; Cen, Z.; Wei, L. Characterization of Nanocellulose and Activated Carbon Nanocomposite Films’ Biosensing Properties for Smart Packaging. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 225, 115189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, J.W.S.; Garcia, V.A.d.S.; Venturini, A.C.; Carvalho, R.A.d.; da Silva, C.F.; Yoshida, C.M.P. Sustainable Coating Paperboard Packaging Material Based on Chitosan, Palmitic Acid, and Activated Carbon: Water Vapor and Fat Barrier Performance. Foods 2022, 11, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabagias, I.; Badeka, A.; Kontominas, M.G. Shelf Life Extension of Lamb Meat Using Thyme or Oregano Essential Oils and Modified Atmosphere Packaging. Meat Science 2011, 88, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, N.; Houde, M.; Bayen, S.; Karboune, S. Exploring the Synergistic Effects of Essential Oil and Plant Extract Combinations to Extend the Shelf Life and the Sensory Acceptance of Meat Products: Multi-Antioxidant Systems. J Food Sci Technol 2023, 60, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleh, H.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Saada, M.; Ksouri, R. Essential Oils: A Promising Eco-Friendly Food Preservative. Food Chemistry 2020, 330, 127268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, L.; Chehab, R.; Osaili, T.M.; Savvaidis, I.N. Antimicrobial Effect of Thymol and Carvacrol Added to a Vinegar-Based Marinade for Controlling Spoilage of Marinated Beef (Shawarma) Stored in Air or Vacuum Packaging. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2020, 332, 108769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Befa Kinki, A.; Atlaw, T.; Haile, T.; Meiso, B.; Belay, D.; Hagos, L.; Hailemichael, F.; Abid, J.; Elawady, A.; Firdous, N. Preservation of Minced Raw Meat Using Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis) and Basil (Ocimum Basilicum) Essential Oils. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2024, 10, 2306016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Heising, J.; Fogliano, V.; Dekker, M. Fat Content and Storage Conditions Are Key Factors on the Partitioning and Activity of Carvacrol in Antimicrobial Packaging. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2020, 24, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) XRD plots of (1) AC as received, and (2) CV@AC nanohybrid, and (b) FTIR plots of (1) pure CV, (2) AC as received, and (3) CV@AC nanohybrid.

Figure 1.

(a) XRD plots of (1) AC as received, and (2) CV@AC nanohybrid, and (b) FTIR plots of (1) pure CV, (2) AC as received, and (3) CV@AC nanohybrid.

Figure 2.

CV desorption isotherm kinetic plots (in triplicates) for CV@AC nanohybrid (a)50 oC/323 oK, (b) 70 oC/343 oK, (c) 90 oC/363 oK and (d) 11 oC/383 oK. The simulation plots graphs according to the second-order pseudokinetic model are depicted by a red line diagram.

Figure 2.

CV desorption isotherm kinetic plots (in triplicates) for CV@AC nanohybrid (a)50 oC/323 oK, (b) 70 oC/343 oK, (c) 90 oC/363 oK and (d) 11 oC/383 oK. The simulation plots graphs according to the second-order pseudokinetic model are depicted by a red line diagram.

Figure 3.

Plot of ln(1/k2) values as a function of (1/T) for CV@AC nanohybrid.

Figure 3.

Plot of ln(1/k2) values as a function of (1/T) for CV@AC nanohybrid.

Figure 4.

(a) XRD plots and (b) FTIR plots of (1) pure PLA/TEC, (2) PLA/TEC/5AC, (3) PLA/TEC/10AC, (4) PLA/TEC/15AC, (5) PLA/TEC/5CV@AC, (6) PLA/TEC/10CV@AC, and (7) PLA/TEC/15CV@AC films.

Figure 4.

(a) XRD plots and (b) FTIR plots of (1) pure PLA/TEC, (2) PLA/TEC/5AC, (3) PLA/TEC/10AC, (4) PLA/TEC/15AC, (5) PLA/TEC/5CV@AC, (6) PLA/TEC/10CV@AC, and (7) PLA/TEC/15CV@AC films.

Figure 5.

SEM images of surface (a,c,e,g,i,k) and cross-section (b,d,f,h,j,l) nanocomposite films of PLA/TEC/5AC (a,b), PLA/TEC/5CV@AC (c,d), PLA/TEC/10AC (e,f), PLA/TEC/10CV@AC (g,h), PLA/TEC/15AC (i,j), PLA/TEC/15CV@AC (k,l).

Figure 5.

SEM images of surface (a,c,e,g,i,k) and cross-section (b,d,f,h,j,l) nanocomposite films of PLA/TEC/5AC (a,b), PLA/TEC/5CV@AC (c,d), PLA/TEC/10AC (e,f), PLA/TEC/10CV@AC (g,h), PLA/TEC/15AC (i,j), PLA/TEC/15CV@AC (k,l).

Figure 5.

(a) Storage modulus plots, (b) Tan delta plots of all PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC packaging films as well as pure PLA/TEC film.

Figure 5.

(a) Storage modulus plots, (b) Tan delta plots of all PLA/TEC/xAC and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC packaging films as well as pure PLA/TEC film.

Figure 6.

CV desorption isotherm kinetic plots (in triplicates) for (a) PLA/TEC/5CV@AC, (b) PLA/TEC/10CV@AC and (c) PLA/TEC/15CV@AC films.

Figure 6.

CV desorption isotherm kinetic plots (in triplicates) for (a) PLA/TEC/5CV@AC, (b) PLA/TEC/10CV@AC and (c) PLA/TEC/15CV@AC films.

Table 1.

Sample names, contents of PLA, TEC, pure AC, and CV@AC nanohybrid, and the twin extruder operating conditions (temperature and speed) used for the development of all PLA/TECx composite blends. PLA: poly-L-lactic acid, TEC: triethyl citrate, CV: carvacrol, and AC: activated carbon.

Table 1.

Sample names, contents of PLA, TEC, pure AC, and CV@AC nanohybrid, and the twin extruder operating conditions (temperature and speed) used for the development of all PLA/TECx composite blends. PLA: poly-L-lactic acid, TEC: triethyl citrate, CV: carvacrol, and AC: activated carbon.

| Sample Name |

PLA

(g) |

TEC

(ml-% v/w) |

AC

(g-% w/w) |

CV@AC

(g-% w/w) |

Twin Extruder Operating Conditions |

| T (°C) |

Speed (rpm) |

Time (min) |

| PLA/TEC |

4 |

0.6-15 |

- |

- |

180 |

120 |

5 |

| PLA/TEC/5AC |

4 |

0.6-15 |

0.2-5 |

- |

180 |

120 |

5 |

| PLA/TEC/10AC |

4 |

0.6-15 |

0.4-10 |

- |

180 |

120 |

5 |

| PLA/TEC/15AC |

4 |

0.6-15 |

0.6-15 |

- |

180 |

120 |

5 |

| PLA/TEC/5CV@AC |

4 |

0.6-15 |

- |

0.2-5 |

180 |

120 |

5 |

| PLA/TEC/10CV@AC |

4 |

0.6-15 |

- |

0.4-10 |

180 |

120 |

5 |

| PLA/TEC/15CV@AC |

4 |

0.6-15 |

- |

0.6-15 |

180 |

120 |

5 |

Table 2.

Calculated k2, and qe, mean values from CV desorption kinetic plots for CV@AC nanohybrid.

Table 2.

Calculated k2, and qe, mean values from CV desorption kinetic plots for CV@AC nanohybrid.

| 50oC/323oK |

CV@AC |

| k2 (s-1) |

4.29.10-5±1.97.10-6

|

| qe |

0.706±0.014 |

| 70oC/343oK |

CV@AC |

| k2 (s-1) |

1.69.10-4±5.91.10-5

|

| qe |

0.727±0.006 |

| 90oC/363oK |

CV@AC |

| k2 (s-1) |

1.60.10-3±0.001 |

| qe |

0.743±0.048 |

| 110oC/383oK |

CV@AC |

| k2 (s-1) |

2.52x10-3±0.001 |

| qe |

0.774±0.039 |

Table 3.

Elastic Modulus E (MPa), ultimate strength σuts (MPa), and % elongation at break values were calculated for all PLA/TEC/xAC, and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films as well as pure PLA/TEC film.

Table 3.

Elastic Modulus E (MPa), ultimate strength σuts (MPa), and % elongation at break values were calculated for all PLA/TEC/xAC, and PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films as well as pure PLA/TEC film.

| Sample Name |

E (Mpa) |

σuts (MPa) |

%ε |

| PLA/TEC |

564.1 ± 93.7 a

|

8.0 ± 1.9 a

|

436.3 ± 285.6 a

|

| PLA/TEC /5 AC |

3391.9±228.7b

|

59.7±7.4b

|

3.1±0.5b

|

| PLA/TEC /10 AC |

2498.7±538.1c

|

42.6±4.9c

|

2.6±0.6b

|

| PLA/TEC /15 AC |

2881.7±683.5d,c

|

50.7±7.6d,b

|

2.9±0.5b

|

| PLA/TEC /5CV@AC |

2003.5±279.3d,c

|

34.6±9.7d,b,c

|

15.9±24.7b

|

| PLA/TEC /10CV@AC |

1736.7±467.7d,c

|

30.2±4.7e,d,b,c

|

171.3±58.0a,c

|

| PLA/TEC /15CV@AC |

625.0±267.0a

|

8.8±1.9a

|

367.7±34.4d,a

|

Table 4.

Water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) and oxygen transmission rate (OTR) mean values as well as the calculated water vapor diffusion coefficient (Dwv), and oxygen permeability PeO2 mean values of all tested films.

Table 4.

Water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) and oxygen transmission rate (OTR) mean values as well as the calculated water vapor diffusion coefficient (Dwv), and oxygen permeability PeO2 mean values of all tested films.

| |

thickness (mm) |

WVTR

(gr.cm-2.s-1) x10-6

|

Dwv

(cm2.s-1) x10-4

|

thickness (mm) |

OTR

(ml.m-2.day-1) |

PeO2

(cm2.s-1)x10-9

|

| PLA/TEC |

0.14±0.01 |

1.8±0.67 |

5.71±1.69a

|

0.08±0.01 |

284.6±56.2 |

2.63±0.55a

|

| PLA/TEC /5 AC |

0.11±0.02 |

0.83±0.21 |

1.57±0.75b

|

0.12±0.04 |

151.5±27.6 |

2.12±0.31a

|

| PLA/TEC /10 AC |

0.13±0.01 |

0.37±0.05 |

1.13±0.05b

|

0.15±0.01 |

121.0±14.1 |

2.04±0.03b,a

|

| PLA/TEC /15 AC |

0.12±0.02 |

0.58±0.19 |

1.56±0.17c,b

|

0.13±0.01 |

159.3±55.1 |

2.39±1.20a

|

| PLA/TEC /5CV@AC |

0.10±0.02 |

0.54±0.28 |

1.14±0.54b

|

0.14±0.02 |

137.0±39.6 |

2.23±0.35a

|

| PLA/TEC /10CV@AC |

0.10±0.03 |

0.94±0.28 |

1.60±0.92b

|

0.09±0.01 |

268.0±152.7 |

2.79±1.14a

|

| PLA/TEC /15CV@AC |

0.13±0.01 |

0.65±0.22 |

1.46±0.52b

|

0.08±0.01 |

361.5±87.0 |

3.43±1.37a

|

Table 5.

Calculated EC50 mean values for all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films.

Table 5.

Calculated EC50 mean values for all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films.

| Sample |

EC50 (mg/L) |

| PLA/TEC/5CV@AC |

14.39 ± 0.60 |

| PLA/TEC/10CV@AC |

6.72 ± 1.23 |

| PLA/TEC/15CV@AC |

10.47 ± 0.43 |

Table 6.

Calculated k2, qe, and EC50, DPPH mean values for all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films.

Table 6.

Calculated k2, qe, and EC50, DPPH mean values for all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC active films.

| |

k2 (s-1) |

qe

|

| PLA/TEC/5CV@AC |

0.00144±0.0003 |

0.0661±0.0112 |

| PLA/TEC/10CV@AC |

0.00085±0.00028 |

0.1099±0.0245 |

| PLA/TEC/15CV@AC |

0.00064±0.00019 |

0.1351±0.0136 |

Table 6.

Antibacterial activity results of all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films against S. aureus and S. Typhimurium.

Table 6.

Antibacterial activity results of all PLA/TEC/xCV@AC films against S. aureus and S. Typhimurium.

| sample |

S. aureus |