Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

13 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

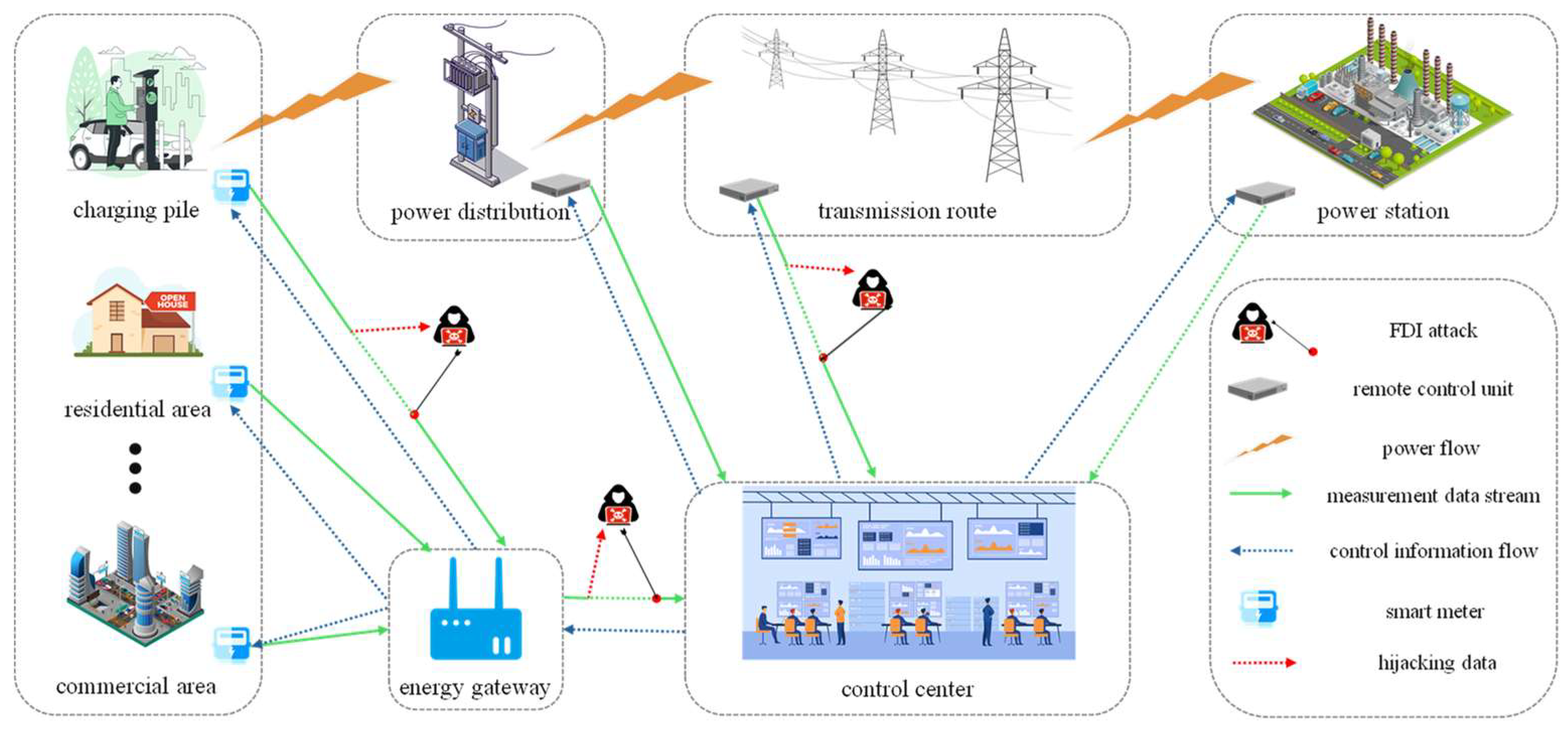

1. Introduction

- A data-driven FDIA detection method is proposed to identify false data that bypasses the traditional bad data detection (BDD) mechanism to further improve the security of power system.

- The method is completely data-driven and has excellent scalability without considering the physical model and topology of the power system.

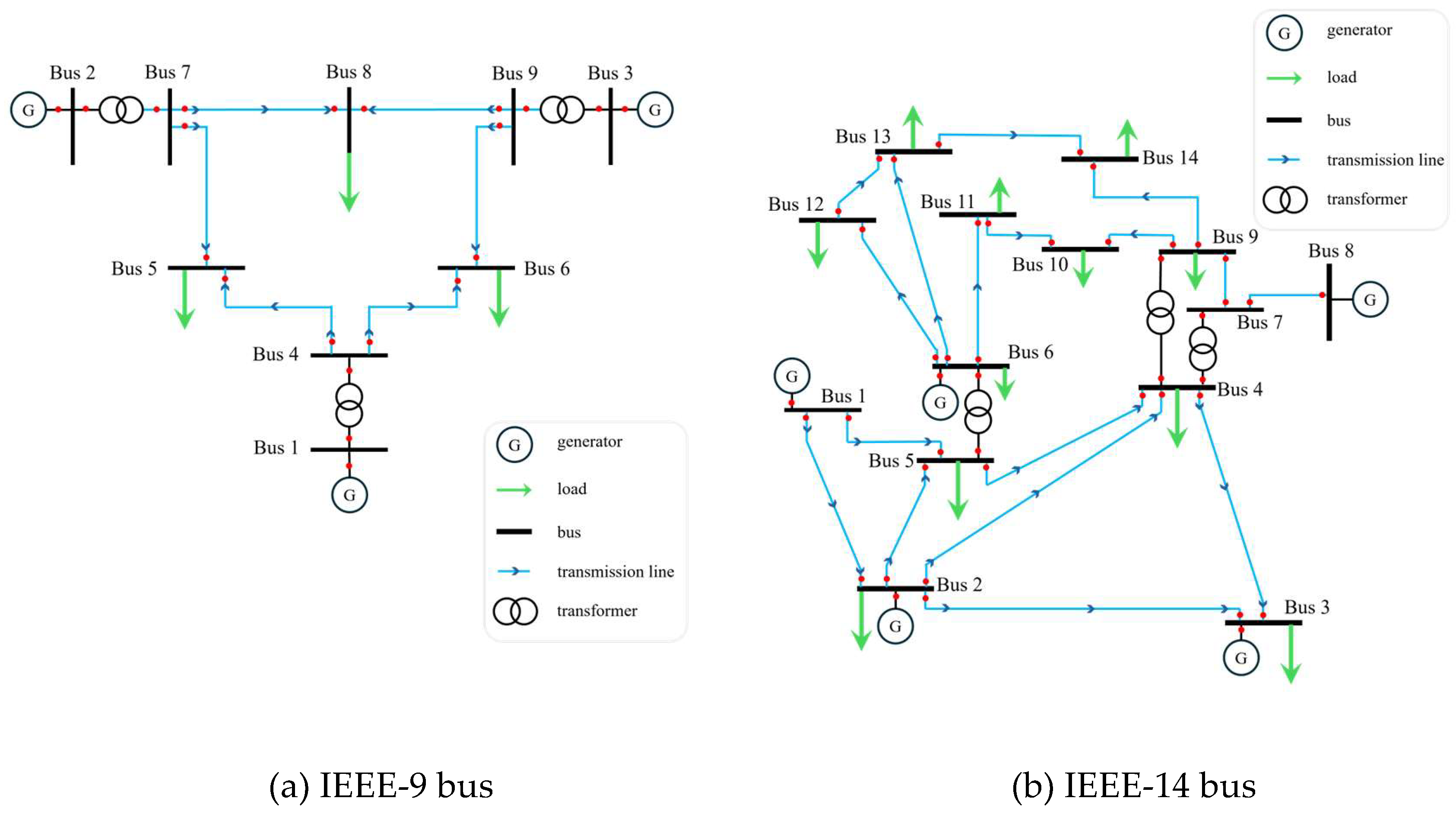

- The proposed method is validated by simulation on IEEE-9, IEEE-14, and IEEE-118 bus systems, considering the interference of measured data in real environments.

2. Related Work

2.1. Based on Model Detection Method

2.2. Based on Data-Driven Detection Method

3. State Estimation and FDIA

3.1. State Estimation

3.2. BDD Technology

3.3. False Data Injection Attack

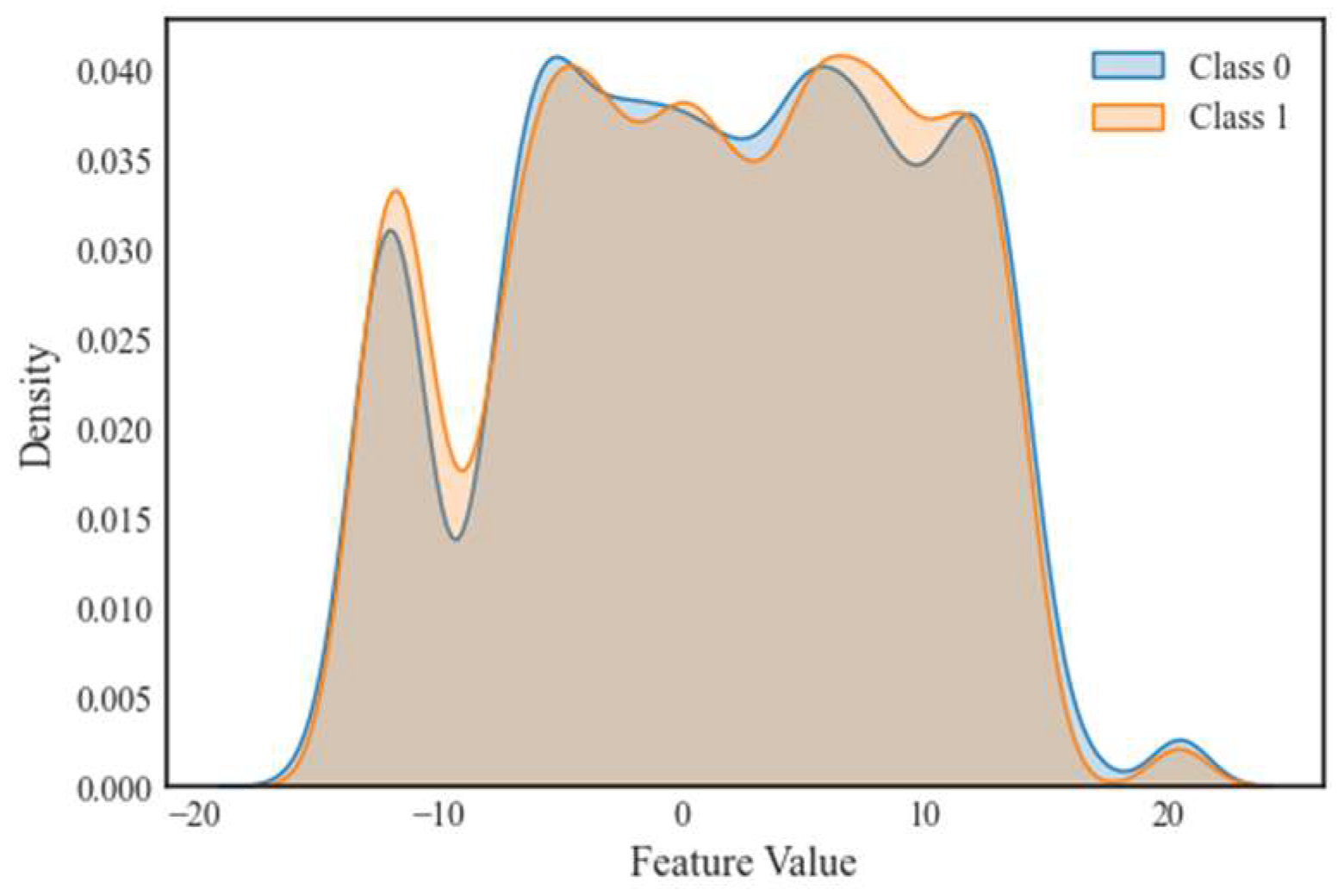

3.4. Problem Analysis

4. Proposed Detection Method

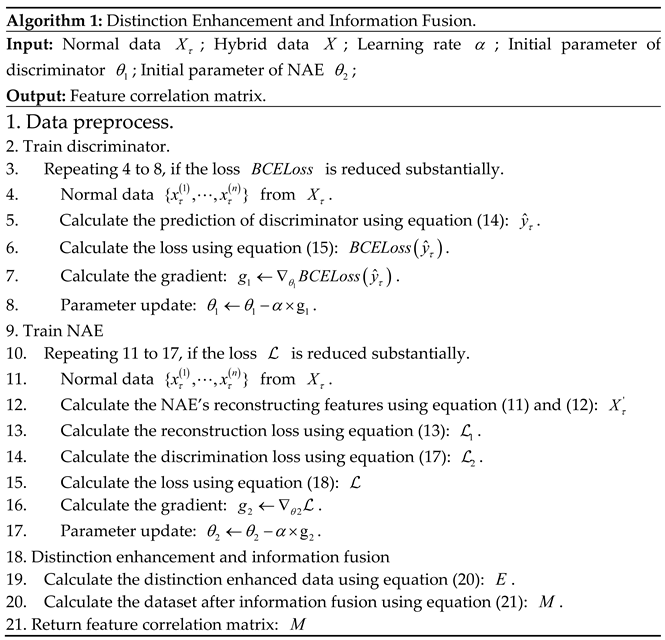

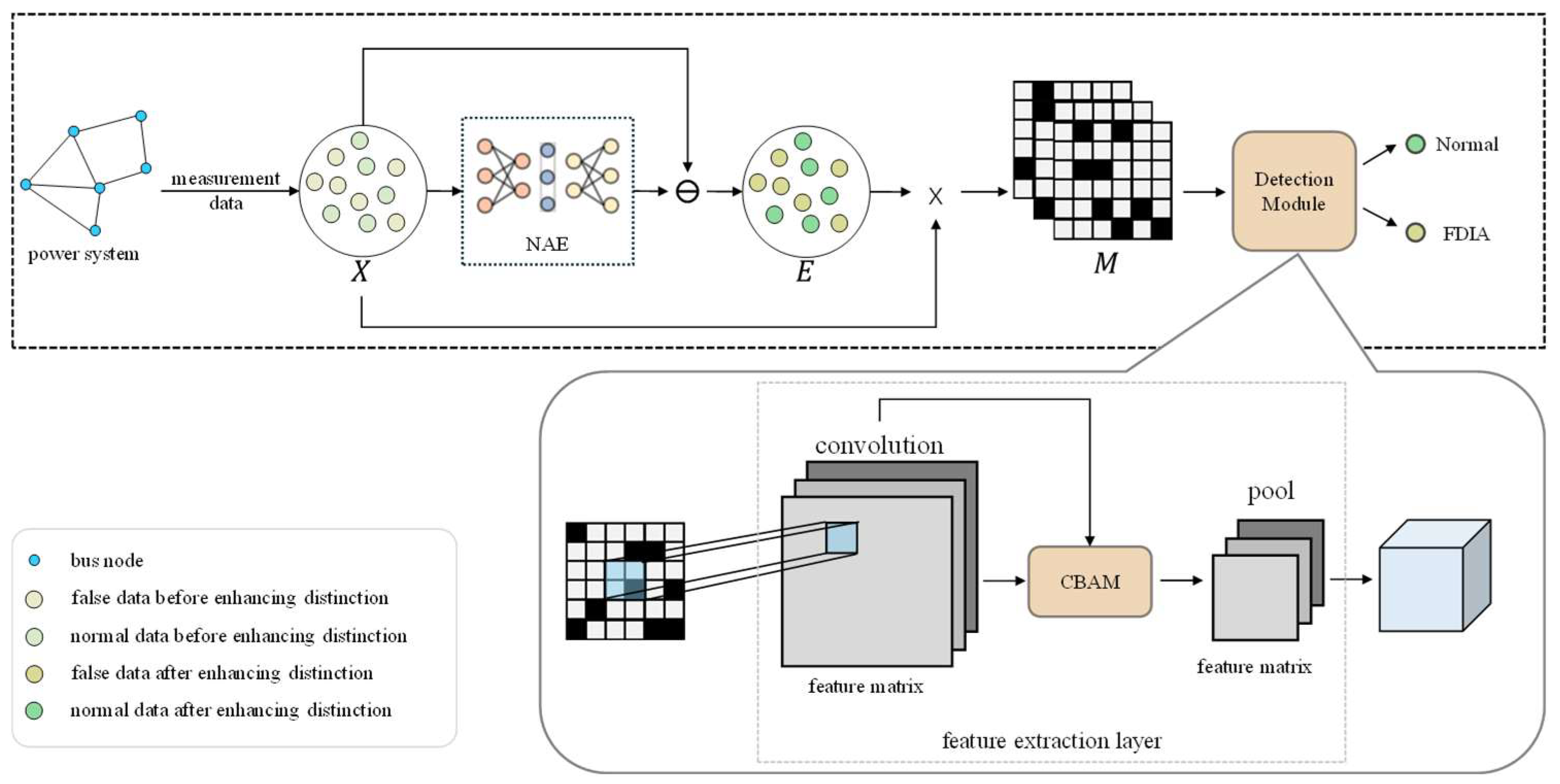

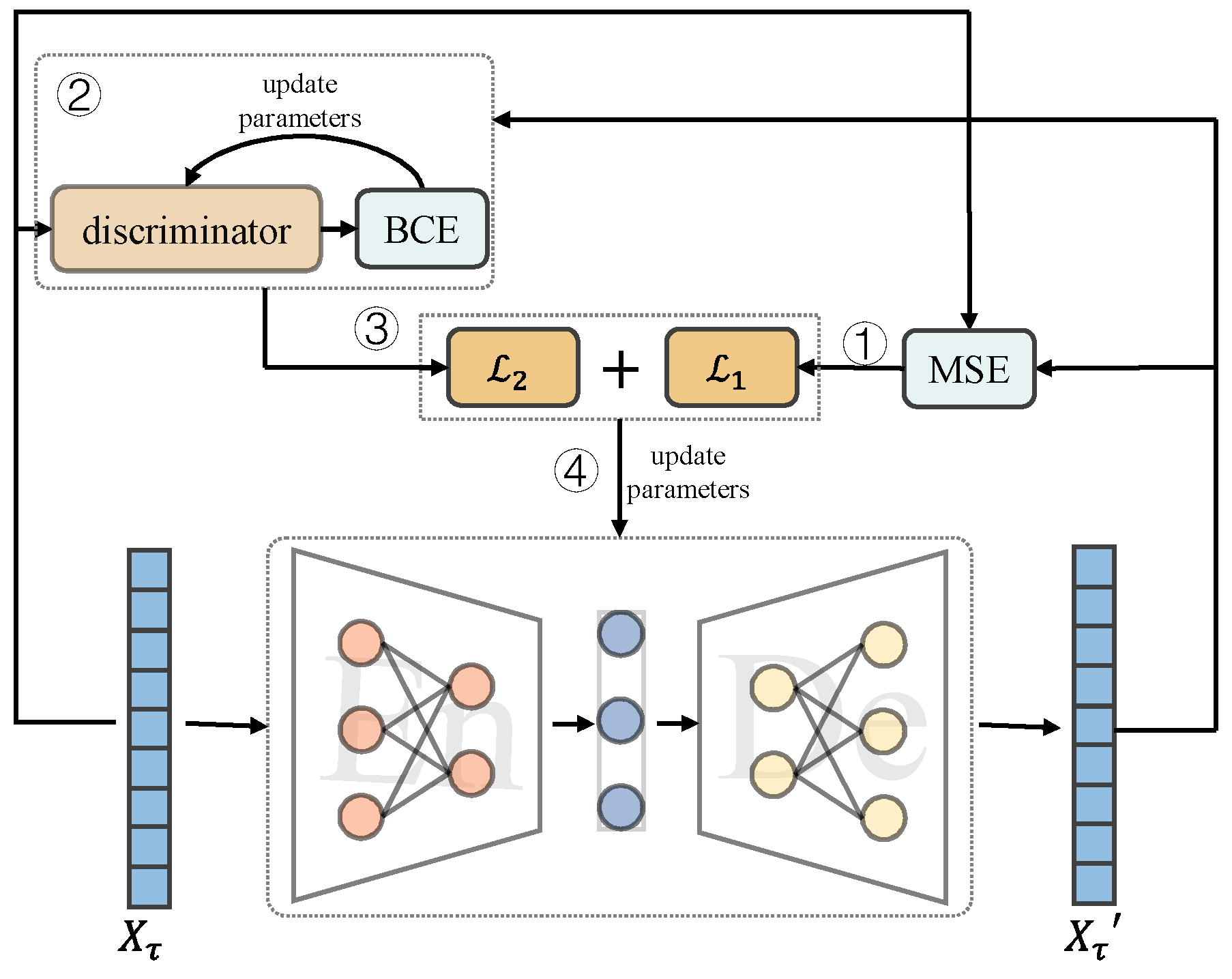

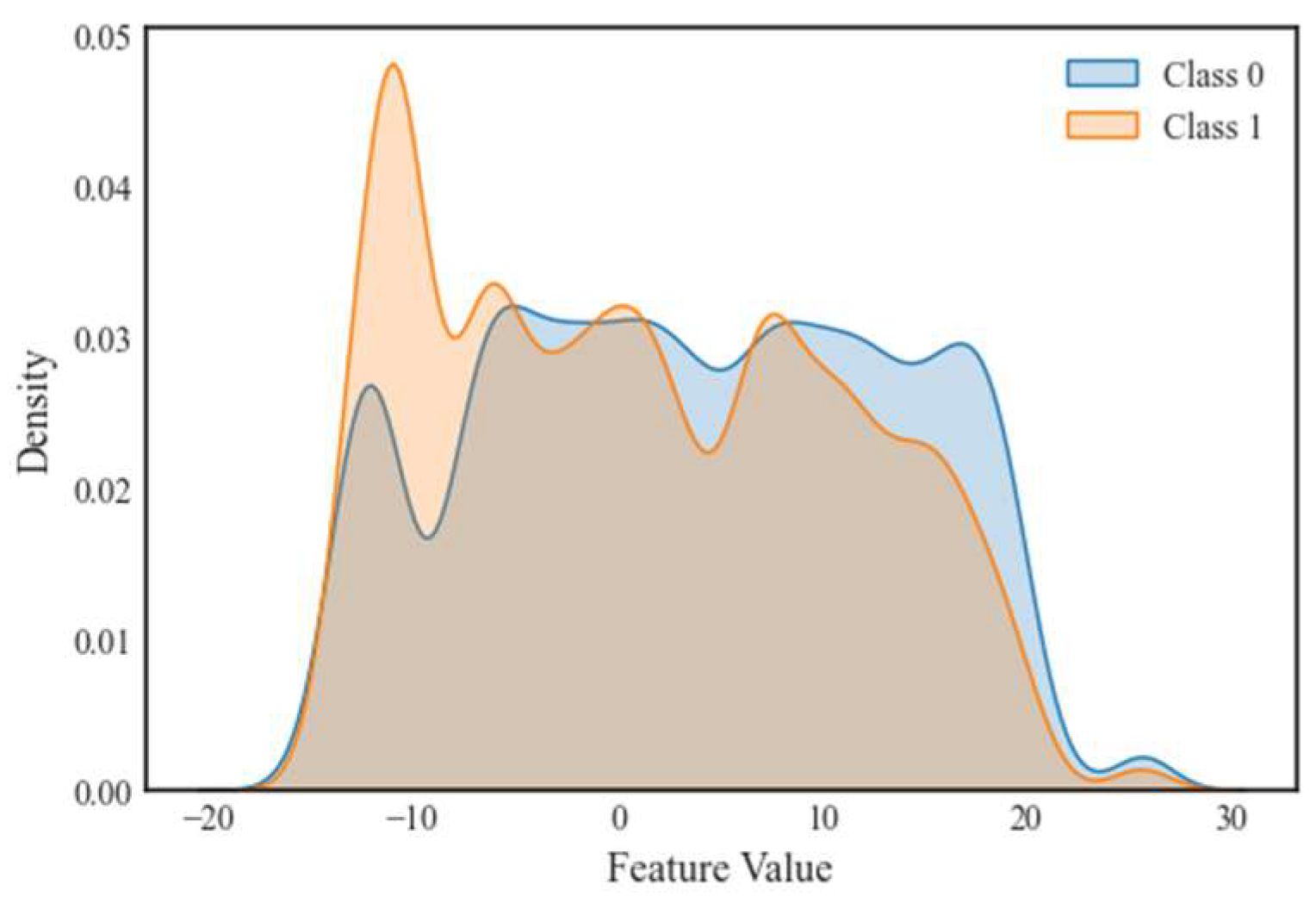

4.1. Distinction Enhancement and Information Fusion

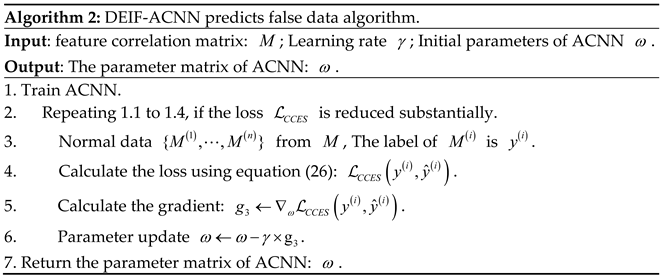

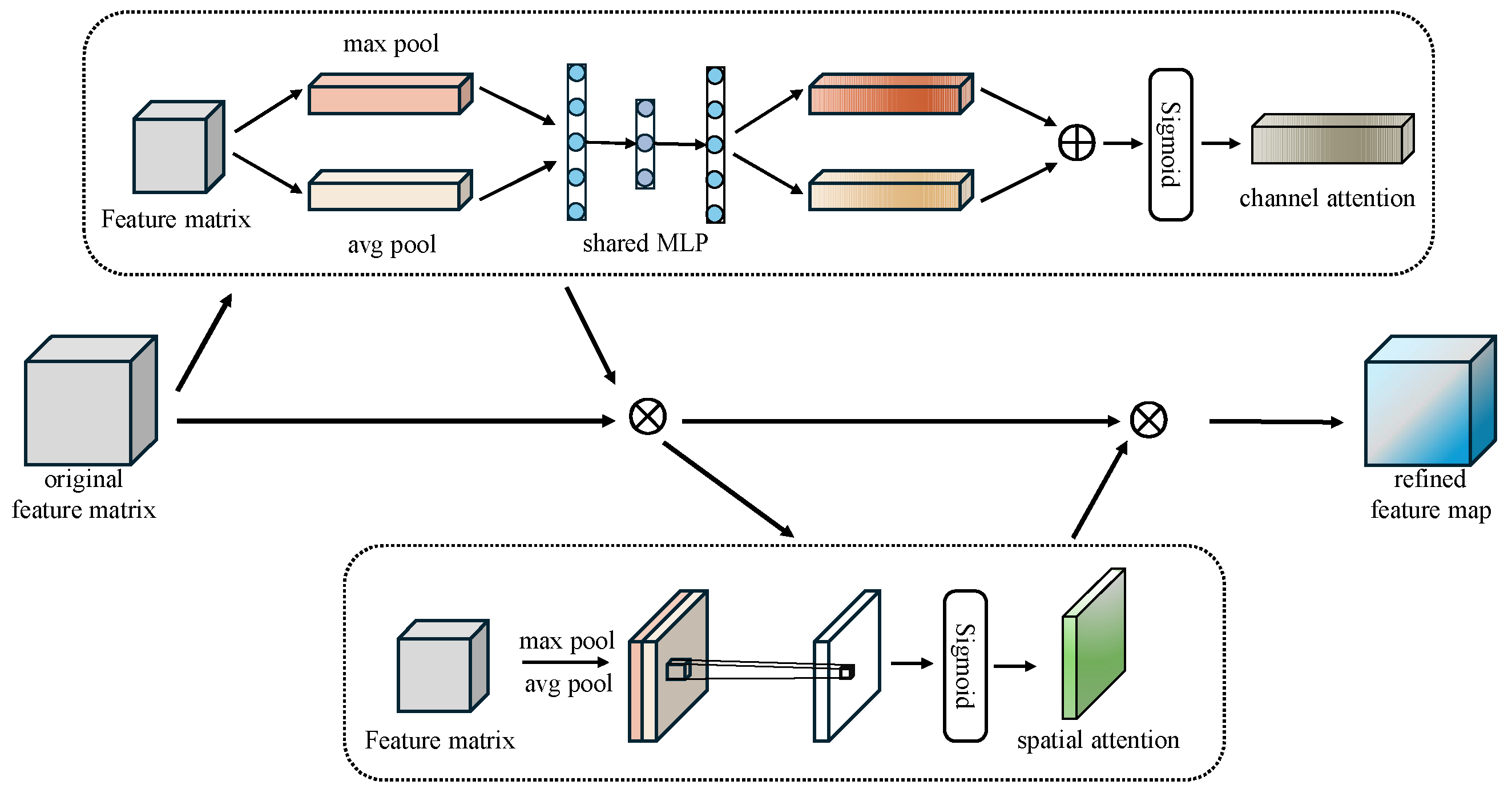

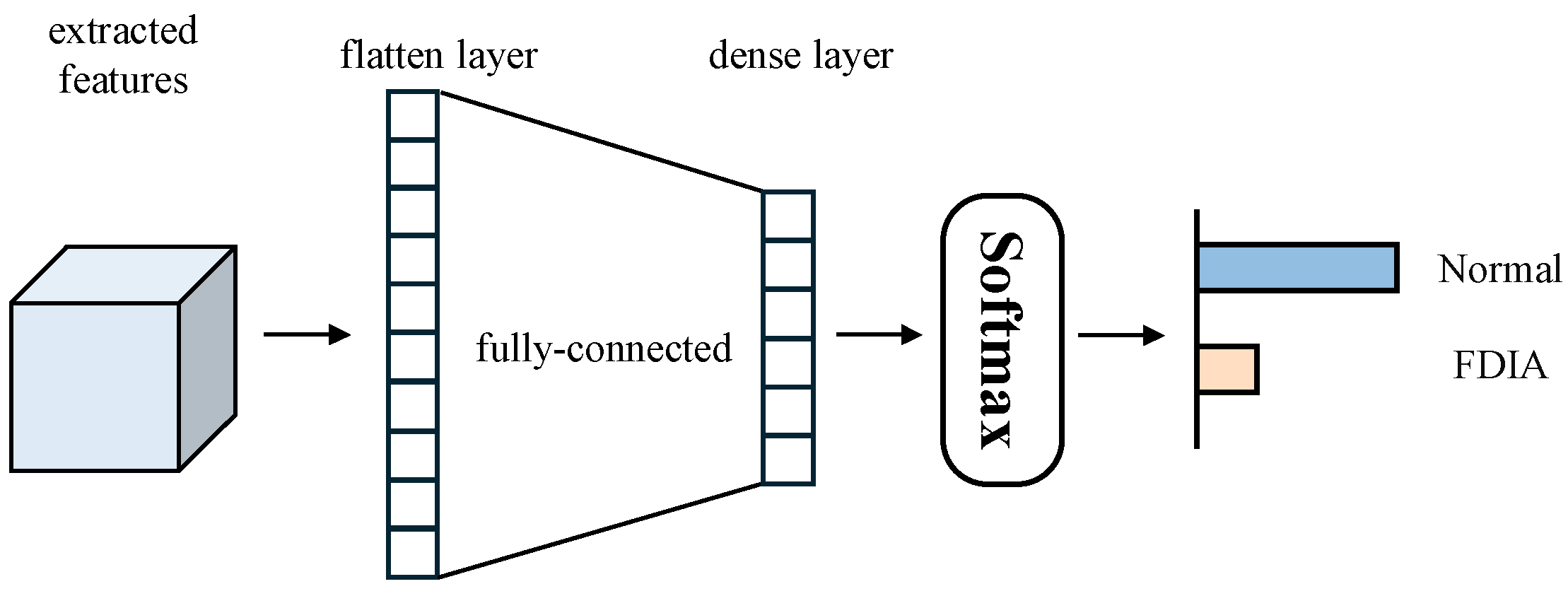

4.2. Attention Convolutional Neural Network

- Feature invariance: pooling operation removes unimportant information in data features, while the retained information is scale invariance and still representative of the data features before pooling.

- Feature dimensionality reduction: the pooling layer reduces the data dimensionality by removing redundant information and extracting only the most important features, thus reducing the amount of computation and preventing overfitting to a certain extent.

5. Experiments

5.1. Dataset Setup

5.1.1. Simulation Case Description

5.1.2. Data Generation

5.1.3. Data Preprocessing

- Balancing Process. From the generated dataset, 15k normal data and 15k false data were randomly selected to form the sample balanced dataset, details are given in Table 3.

- Normalization Process. The features of the dataset are deflated to between [0,1]. The deflation process is as follows:

| Bus name | Bus-9 | Bus-14 | Bus-118 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal data | 15000 | 15000 | 15000 |

| False data | 15000 | 15000 | 15000 |

| Number of features | 36 | 68 | 608 |

| Total | 30000 | 30000 | 30000 |

- 3.

- Dataset splitting. Throughout the experiments, each dataset was divided into 60% training set, 20% validation set and 20% test set.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

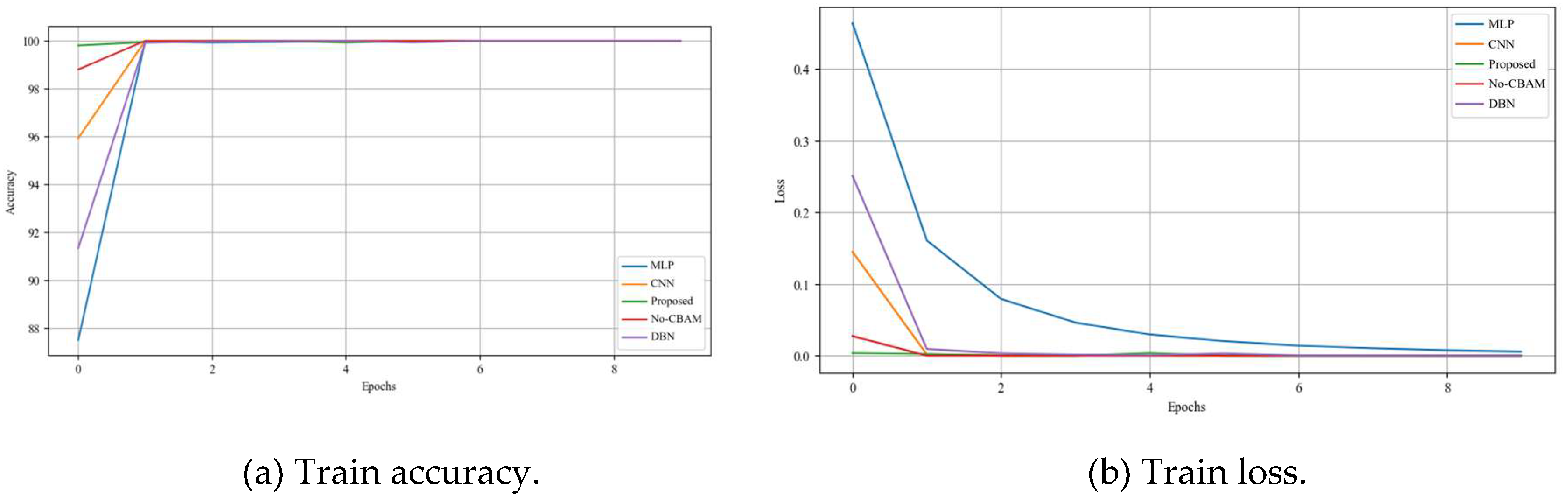

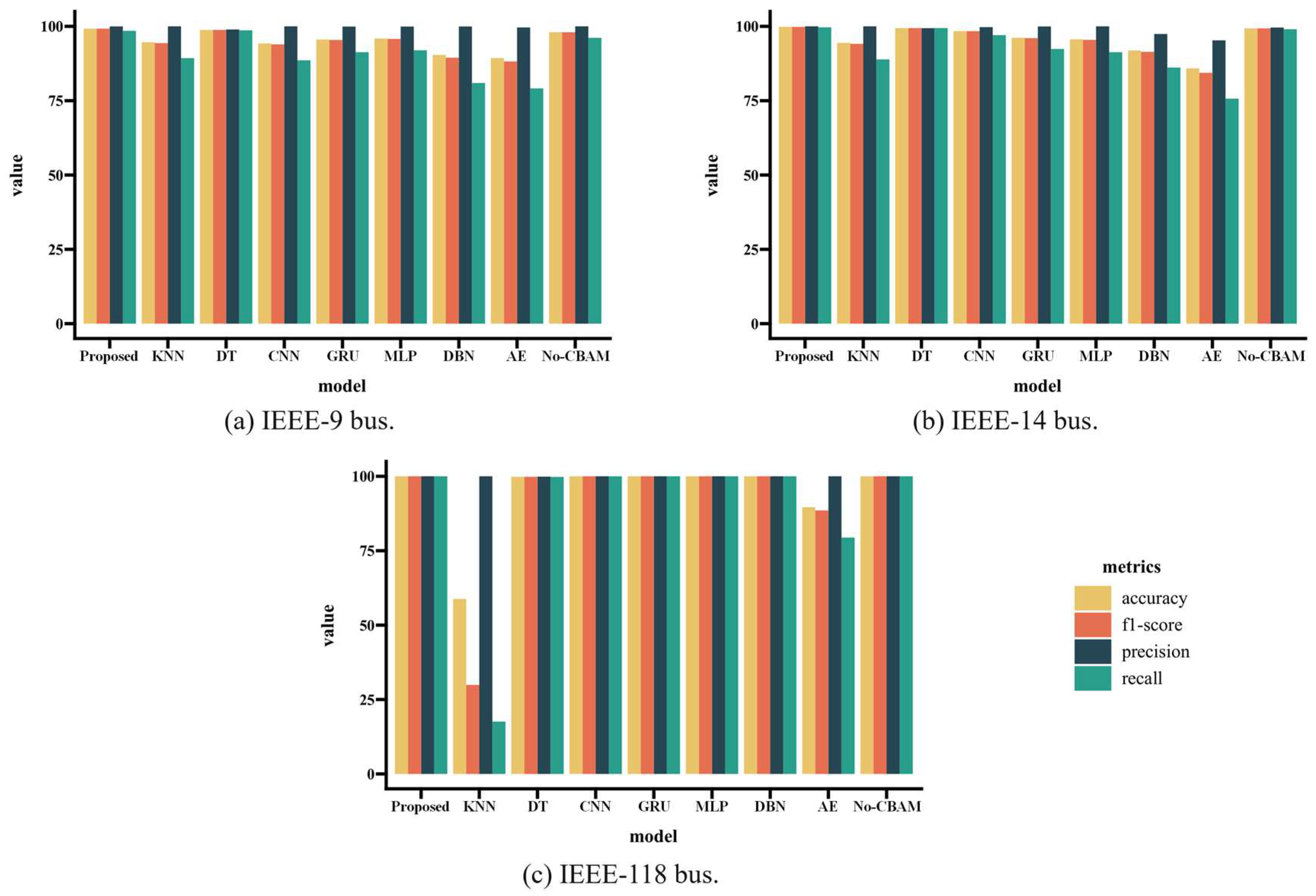

5.3. FDIA Detection Performance

5.3.1. Ideal Environment

5.3.2. Noise Environment

6. Conclusion

7. Patents

References

- Dehghanpour, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Bu, F. A Survey on State Estimation Techniques and Challenges in Smart Distribution Systems. in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 2312-2322, March 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Misra, S.; Xue, G.; Yang, D. Smart Grid — The New and Improved Power Grid: A Survey,” in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 944-980, Fourth Quarter 2012. [CrossRef]

- Spanò, E.; Niccolini, L.; Pascoli, S.D.; Iannacconeluca, G. Last-Meter Smart Grid Embedded in an Internet-of-Things Platform,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 468-476, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Hahn, A.; Govindarasu, M. Cyber–Physical System Security for the Electric Power Grid,” in Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 210-224, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Xiao, G.; Lu, R.; Liang, H.; Vasilakos, A.V. False Data Injection on State Estimation in Power Systems—Attacks, Impacts, and Defense: A Survey,” in IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 411-423, April 2017. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; et al. Smart Transmission Grid: Vision and Framework,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 168-177, Sept. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.-H.; Chin, W.-L. Blind False Data Injection Attack Using PCA Approximation Method in Smart Grid,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 1219-1226, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Zhao, J.; Luo, F.; Weller, S.R.; Dong, Z.Y. A Review of False Data Injection Attacks Against Modern Power Systems,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 1630-1638, July 2017. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ning, P.; Reiter, M.K. 2011. False data injection attacks against state estimation in electric power grids. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 14, 1, Article 13 (May 2011), 33 pages. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, L.; Lu, Z. Detection of false data injection attack in power grid based on spatial-temporal transformer network[J]. Expert Systems with Applications, 2024, 238: 121706.

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Developing graphical detection techniques for maintaining state estimation integrity against false data injection attack in integrated electric cyber-physical system[J]. Journal of systems architecture, 2020, 105: 101705.

- Musleh, A.S.; Chen, G.; Dong, Z.Y. A Survey on the Detection Algorithms for False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 2218-2234, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zeng, W.; Chow, M.-Y. Resilient Distributed DC Optimal Power Flow Against Data Integrity Attack,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 3543-3552, July 2018. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lu, R.; Xiao, G.; Su, Z.; Ghorbani, A. PAMA: A Proactive Approach to Mitigate False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids,” 2018 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2018, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Kallitsis, M.G.; Bhattacharya, S.; Stoev, S.; Michailidis, G. Adaptive statistical detection of false data injection attacks in smart grids,” 2016 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP), Washington, DC, USA, 2016, pp. 826-830. [CrossRef]

- Moslemi, R.; Mesbahi, A.; Velni, J.M. A Fast, Decentralized Covariance Selection-Based Approach to Detect Cyber Attacks in Smart Grids,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 4930-4941, Sept. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, K.; Cao, X.; Hu, F.; Liu, Y. Detection of Faults and Attacks Including False Data Injection Attack in Smart Grid Using Kalman Filter,” in IEEE Transactions on Control of Network Systems, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 370-379, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ding, T.; Huang, C.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y. Detecting False Data Injection Attacks Against Power System State Estimation With Fast Go-Decomposition Approach,” in IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 2892-2904, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yılmaz, Y.; Wang, X. Quickest Detection of False Data Injection Attack in Wide-Area Smart Grids,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 2725-2735, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Mendis, G.J.; Wei, J. Real-Time Detection of False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grid: A Deep Learning-Based Intelligent Mechanism,” in IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 2505-2516, Sept. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, S.A.; Salmasi, F.R. (2017), Detection of false data injection attacks against state estimation in smart grids based on a mixture Gaussian distribution learning method. IET Cyber-Physical Systems: Theory & Applications, 2: 161-171. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tindemans, S.; Pan, K.; Palensky, P. Detection of False Data Injection Attacks Using the Autoencoder Approach,” 2020 International Conference on Probabilistic Methods Applied to Power Systems (PMAPS), Liege, Belgium, 2020, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Wang, L.; Cao, Z. , et al. False data injection attacks detection on power systems with convolutional neural network[C]//Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2020, 1633(1): 012134.

- Zimmerman, R.D.; Murillo-Sanchez, C.E.; Thomas, R.J. MATPOWER: Steady-State Operations, Planning and Analysis Tools for Power Systems Research and Education,” Power Systems, IEEE Transactions on, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 12–19, Feb. 2011.

- Information Trust Institute Grainger College of Engineering (2024). IEEE 118-Bus System. https://icseg.iti.illinois.edu/ieee-118-bus-system/.

- Trindade, A. (2015). ElectricityLoadDiagrams20112014 [Dataset]. UCI Machine Learning Repository. [CrossRef]

| name | Column | Description |

|---|---|---|

| bus | PD | real power demand |

| QD | reactive power demand | |

| generator | PG | real power output |

| QG | reactive power output | |

| branch | PF | real power injected at “from” bus end |

| QF | reactive power injected at “from” bus end |

| Test case | Type | Number | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| IEEE-9 bus | 9 (9 buses) | 36 | |

| 9 (9 buses) | |||

| 9 (9 branch) | |||

| 9 (9 branch) | |||

| IEEE-14 bus | 14 (14 buses) | 68 | |

| 14 (14 buses) | |||

| 20 (20 branch) | |||

| 20 (20 branch) | |||

| IEEE-118 bus | 118 (118 buses) | 608 | |

| 118 (118 buses) | |||

| 186 (186 branch) | |||

| 186 (186 branch) |

| System | Method | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEEE-9 bus | Proposed | 99.22 | 99.97 | 98.48 | 99.22 |

| KNN | 94.65 | 100.00 | 89.31 | 94.35 | |

| DT | 98.80 | 98.95 | 98.66 | 98.80 | |

| MLP | 94.25 | 100.00 | 88.58 | 93.95 | |

| CNN | 95.58 | 99.93 | 91.30 | 95.42 | |

| GRU | 95.92 | 99.93 | 91.96 | 95.78 | |

| DBN | 90.38 | 99.96 | 80.94 | 89.45 | |

| AE | 89.33 | 99.62 | 79.12 | 88.20 | |

| No-CBAM | 98.05 | 100.00 | 96.13 | 98.03 | |

| IEEE-14 bus | Proposed | 99.83 | 100.00 | 99.67 | 99.83 |

| KNN | 94.44 | 100.00 | 88.88 | 94.11 | |

| DT | 99.40 | 99.38 | 99.42 | 99.40 | |

| MLP | 95.62 | 100.00 | 91.30 | 95.45 | |

| CNN | 98.38 | 99.73 | 97.05 | 98.37 | |

| GRU | 96.15 | 99.96 | 92.39 | 96.03 | |

| DBN | 91.87 | 97.42 | 86.14 | 91.43 | |

| AE | 85.87 | 95.29 | 75.68 | 84.36 | |

| No-CBAM | 99.32 | 99.60 | 99.04 | 99.32 | |

| IEEE-118 bus | Proposed | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| KNN | 58.80 | 100.00 | 17.58 | 29.90 | |

| DT | 99.84 | 99.89 | 99.79 | 99.84 | |

| MLP | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| CNN | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| GRU | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| DBN | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| AE | 89.63 | 100.00 | 79.42 | 88.53 | |

| No-CBAM | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Dataset | λ (Noise level) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEEE-9 bus | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| IEEE-14 bus | 0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| IEEE-118 bus | 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).