1. Introduction

In its many forms, human communication is an essential pillar of social and cognitive development, facilitating the transmission of ideas and cultural and social integration. Language acts as a shared system of signs and rules, allowing individuals to express and comprehend complex meanings [

1,

2]. In this context, language acquisition emerges as a natural process that develops through interaction and observation of the communicative environment, enabling spontaneous learning without formal instruction [

3,

4,

5]. However, language acquisition is not equally accessible to everyone, as certain sensory conditions, such as hearing impairments, can create significant barriers.

According to data from the World Health Organisation, 15% of the global population has some form of disability, with 24% of these corresponding to sensory and communication disabilities [

6,

7]. Among this group, hearing impairments affect 25% of people with sensory disabilities, a situation that is expected to worsen. Projections indicate that by 2050, the number of people with hearing loss could reach 2.5 billion [

6,

7,

8]. Factors contributing to this increase include population ageing, prolonged exposure to loud noises, lack of adherence to medical treatments for ear infections, and the use of ototoxic medications [

6,

7]. The implications of these impairments vary and depend on the severity of hearing loss and the age at which it occurs, impacting both oral and written communication and affecting learning, social relationships, and personal development.

In the context of deaf people, sign language is crucial in enabling active social engagement through a unique linguistic system that includes gestures, movements, and facial expressions [

2,

4,

8]. It is important to note that sign language is not universal; regional and cultural variations can hinder communication among deaf people from diverse backgrounds [

2,

4,

9,

10]. Moreover, the limited inclusion of sign language in essential services such as education and healthcare creates barriers to the social integration of people with hearing disabilities [

2,

6,

11,

12].

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence and deep learning techniques have significantly contributed to sign language recognition and automatic translation. These advancements have led to the development of systems capable of interpreting gestures and converting them into text or speech [

2,

4,

9,

10,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, these systems have limitations in accuracy and in capturing the complexity of visual language, which involves hand configurations, gestures’ orientation, movement, location, and contextual meaning. There is a fundamental need for a more comprehensive and detailed approach to developing these technologies to improve their effectiveness and applicability in everyday life.

Our research introduces a new method for automatically translating sign language using an optimised deep-learning architecture designed to model the linguistic features of sign language. It is a significant advancement compared to previous approaches focusing on classifying individual words through computer vision since our study breaks down gestures into their essential double articulation components. This approach allows us to more accurately capture the complexity of interactions between hands, space, and movements to perform detailed and semiotic analysis, which studies signs and symbols and their use or interpretation of gestures. Thus, we provide a more faithful representation of visual language that overcomes the limitations of conventional approaches. Our tests achieved a Cohen’s Kappa coefficient and a Matthews correlation coefficient of 99.65% for 10, 30, 100, 150, 220, 320, 480, 700, and 1171 simulated gestures of representative sign language vocabulary. These findings suggest that our proposed architecture has the potential to improve communication between deaf and hearing individuals significantly. If implemented, it could enhance the accuracy and reliability of sign language interpretation and have a meaningful impact on social integration and communication.

The document gives a detailed overview of the development and validation of the proposed system. It starts with thoroughly reviewing the literature on sign language recognition to build a strong foundation for the research. This review discusses the limitations and recent advancements in the field. The document then explains the methodology, including semiotic transcription and scalable architecture design. It presents the experimental results and evaluates the accuracy of the approach compared to other methodologies. Finally, it discusses the implications, limitations of the approach, and future research directions, emphasising the importance of integrating more diverse data and continuously refining the system for optimal real-time translation.

2. Literature Review

The global population of individuals with hearing impairments is increasing, making sign language recognition systems essential for improving communication within this community. The research on sign language (SL) translation and recognition is extensive and diverse, encompassing various innovative approaches. From haptic technology to advanced computer vision techniques, through smart wearable devices and human-machine interfaces, the design of sign language translation systems has been a challenging topic with promising results, making it a viable solution to promote more inclusive communication.

A hydrogel deformation sensor with silica nanoparticles has been developed in [

17] to improve the control of robotic hands and recognise gestures. The sensor successfully identified 15 sign language signs with an accuracy of

. A gesture recognition system made of silicone elastomer and ultrasonic waves achieved an accuracy of 91.13% to recognise eight common hand gestures and 88.5% to recognise ten SL digits [

18]. Another innovative device is a flexible deformation sensor with a snake-inspired structure, which has demonstrated high accuracy in recognising 21 SL signs, achieving a 98% success rate [

19]. Furthermore, a smart glove designed for SL translation uses a single sensor to capture hand movements and convert them into text or voice, achieving 90% accuracy for 26 letters of the American alphabet [

20]. Lastly, an optical fibre glove has been made for American SL recognition. It is very good at figuring out what ten numbers, 26 letters, 18 words, and five sentences mean, with a success rate of 98.6% for static gestures and 95% for dynamic gestures [

21].

In real-time translation, Turkish SL has been utilised to create a glove that combines fuzzy logic-assisted and extreme learning machines. This system has achieved 96.8% accuracy with a minimal processing time of

for 120 words, providing an innovative solution for real-time communication [

22]. The “SignTalk” mobile application receives and converts recognised signs into text and voice by employing a Tiny machine learning solution to recognise SL using a low-cost wearable device connected to the Internet. It utilises a lightweight deep neural network to interpret isolated signs of Indian SL based on motion sensor data, where transfer learning is used to initialise the model parameters. The system achieves an accuracy of 87.18% with only four observations of the 120 signs [

23].

Researchers have also proposed using computer vision, neural networks, and landmark estimation to improve sign language (SL) translation and recognition. These ideas involve developing and comparing various algorithms capable of understanding SL. Several studies have utilised deep neural networks and data from SL in RGB video or image format, resulting in significant progress in translation and recognition tasks for this language. One of the proposals involves an application that leverages the Internet of Things (IoT) and gesture recognition with MediaPipe [

24]. This application enables communication between Mexican SL users and non-disabled individuals by connecting an Apple Watch with a camera to translate gestures. It has achieved 96% recognition accuracy for 44 classes, including digits, Spanish alphabet letters, greetings, and an object. Another study aimed to improve communication for deaf or hard-of-hearing individuals who do not know SL through a mobile application [

25]. The app uses the MediaPipe library for video classification and includes a real-time translation function. Initially, the VGG16 library was used to create and train the model, but due to low accuracy, the MediaPipe library was chosen for better 3D coordinate detection. The model achieved 85% accuracy for ten words.

The work in [

26] suggested an algorithm using CNN, which achieved an accuracy of 99.7% for 32 different classes, which is better than current models and has much potential for helping technology work better. In [

27], an SL translation between Mexican SL and Spanish achieved an accuracy of 98.8% for ten signs using a bidirectional RNN, including phrases that can be used in school. This is done using MediaPipe to find critical points in gestures. The study highlights the importance of manual features in SL translation and its potential to be expanded to other languages. In [

28], a system for translating Panamanian SL into Spanish text was developed using an LSTM model. This model can work with non-static signs as sequential data. The deep learning model focuses on action detection, accurately processing frames where gestures are executed. In addition to hands, visual features such as the speaker’s face and pose were considered. The system was trained with a dataset of 330 videos corresponding to 5 classes and achieved an accuracy of 98.8%.

A study introduces an innovative method for translating Urdu sign language using a CNN model designed explicitly for languages with limited resources [

29]. In contrast to previous research focusing on sign languages with large networks, this study addresses translation in Urdu sign language with limited ones. The study conducted experiments using two datasets of 1500 and 78000 images for 37 Urdu signs. The process involved modules for gathering, preprocessing, categorisation, and prediction. The results showed that the model outperformed other machine learning methods, achieving an accuracy of 95% and excelling in precision, recall, and F1-score measures. Another proposal focused on expanding Indian and Vietnamese sign language datasets [

30]. This involved distorting gestures using the MediaPipe tool and a GRU-LSTM classification model, resulting in over 95% accuracy for 60 Indian SL words. This approach applied data augmentation over the Vietnamese sign language corpus to get 4364 new samples, demonstrating its potential to enhance resources for sign language recognition systems.

On the other hand, there needs to be more research in sign language (SL) translation than in spoken language translation advances. Because obtaining annotations is costly and slow, a new method of processing SL videos without using annotations was proposed in [

31]. This approach uses the interpreter’s skeletal points to identify movements, which increases the model’s robustness against background noise. These methods were tested with German SL (RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather 2014T) and Korean SL (KETI), achieving an 84% success rate. Likewise, existing research in SL translation has yet to fully utilise techniques such as skin masking, edge detection, and feature extraction [

32]. The study employs the SURF model for feature extraction, which is resistant to variations such as rotation, scale, and occlusion. Additionally, it uses the Bag of Visual Words (BoVW) model for gesture-to-text conversion. The system was evaluated with machine learning algorithms, achieving accuracy between 79% and 92% for Indian alphabet letter and digit classification.

Finally, some studies focus on creating a two-way sign language translation system to help people with hearing impairments communicate more effectively. One study introduces a real-time avatar system that can translate text or voice into Arabic SL movements using a deep learning model based on YOLOv8. This system can recognise and interpret gestures in real time with high precision. The avatar is trained with three sets of data: an RGB dataset of the Arabic alphabet sign language, an SL detection image dataset, and an Arabic SL dataset with

recognition accuracy. This technology aims to improve communication for deaf and mute individuals in Arabic-speaking communities [

33]. Similarly, an automatic translation system was developed to convert Arabic text and audio into sign language using an animated character to replicate the corresponding gestures. Due to limited resources, a dataset of 12187 pairs of words and signs was created. The model uses bidirectional transformers and achieved an accuracy of 94.71% in training and 87.04% in testing [

34].

In summary, translation and automatic sign language recognition have seen significant advancements in recent years, thanks to the convergence of various disciplines such as artificial intelligence and image processing. Research in this area has led to various innovative solutions, from sensor-based systems and wearable devices to sophisticated deep-learning algorithms. Studies demonstrate a consensus about the feasibility and potential of these technologies to improve communication and inclusion for deaf people. The developed systems have achieved increasingly higher levels of accuracy in gesture classification and translation thanks to advanced techniques in deep learning and transformation methods.

Despite significant progress in the field, challenges still require in-depth understanding. These include the need for standardisation in the notation used to represent sign language, the development of vision-based techniques to improve the accuracy of gesture translation, and the creation of language-independent annotations to connect different sign languages.

First, generating synthetic sign language datasets can enhance the effectiveness of sign language systems, as demonstrated in [

35]. Second, it is important to separate key elements involved in the process, such as posture and hand position. This was effectively accomplished in [

36], where the researchers achieved high accuracy by training models with data from one hand and two hands, even in noisy backgrounds. Finally, the need for standardised notations for representing sign language and the scarcity of large annotated datasets limit the development of more robust and generalisable models. For instance, the work in [

37] highlights the need for standardised annotation methods by focusing on the interpreter’s body movements rather than the meanings of the signs. This underscores the necessity for a broader range of databases to support machine learning models.

3. The Sign Language Visual Semiotic Decoder

The progress in sign language (SL) recognition and translation is impressive; however, the absence of a standard notation and the limited data availability hinder its development. To address these challenges, pioneering researchers such as William Stokoe, Scott Liddell, R. E. Johnson, Ursula Bellugi, and others have established a foundation for a better understanding of sign language structure [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. This study introduces the Sign Language Visual Semiotic Decoder (SLVSD), which addresses the need for a systematic decomposition of signs. This approach allows for the coherent, consistent, and objective representation of signs, regardless of who is presenting them. Such decomposition facilitates accurate comparisons, making identifying patterns and linguistic relationships easier. Additionally, it enhances understanding of the structure and meaning of sign language, providing a semiotic representation geared towards linguistic modelling.

The SLVSD consists of two main components: the Visual Semiotic Encoder (VSE) and the Sign Language Decoder (SLD). The VSE employs a descriptive methodology to analyse each sign by breaking it into its basic elements. This detailed approach allows for extracting fundamental semiotic units converted into a textual format. The SLD utilises a deep learning model that provides a linguistic representation of sign language and performs a lexical interpretation of the semiotic transcription of signs.

3.1. Visual Semiotic Encoder

The Visual Semiotic Encoder (VSE) is designed to create a standard notation for representing the fundamental semiotic units of the double articulation in sign language. Its goal is to transform the inherently complex articulatory parameters into a clear and easily understandable semiotic representation. The VSE comprises the following semiotic units: hang configuration (HC), orientation (OR), localisation (LO), and movement (MOV). This system not only simplifies and models the intricate articulatory features of SL but also establishes a way for developing more accessible transcription systems for sign language.

3.1.1. Hand Configuration - HC

We propose a simplified transcription system for HC using the principles of formational trait systems presented in [

38,

39,

40]. This system involves a detailed decomposition of formational traits, including selection, finger posture, and their interactions. The aim is to develop a coding system incorporating alpha-numeric signs and specific diacritical symbols [

b,

c,

d,

°]. These combinations enable the essential elements of binary systems to be captured in a manner that is more accessible and understandable for users.

The chosen fingers play a crucial role in the HC features. These indicate which fingers are involved in a specific configuration and how they are utilised. Each finger is assigned a number: one for the index finger, two for the middle finger, three for the ring finger, and four for the pinky finger. A positive symbol is deemed if a finger is selected. Otherwise, the finger will receive a negative symbol. Additionally, the trait indicating unselected fingers, referred to as [usf], specifies whether these unselected fingers are flexed (positive symbol) or extended (negative symbol), providing further insight into the hand’s posture.

The posture of the fingers determines the shape each selected finger takes, considering the flexion or extension of its three phalanges. Three traits describe the state of each joint: metacarpophalangeal joint [mcp], proximal interphalangeal joints [pip], and distal interphalangeal joints [dip]. The symbols [+] for open fingers and [-] for closed fingers represent the most typical postures. Additionally, there is a less common posture, [d-] and [d+], which indicates a closed finger with an extended distal interphalangeal joint. However, our HC simplification does not use them.

Within the interaction of the fingers, we find traits such as separated [sep], alpha crossed [], beta crossed [], tip contact [tip], and stacked [stk]. This variety of interactions is fundamental to understanding how SL encodes meanings through subtle and precise hand movements and how these movements are articulated with other semiotic units. The tip contact will not be used in our HC simplification as the hand’s [d-] and [d+] posture.

In addition to considering the posture and interaction, the joint tension in HC can influence the meaning of a sign, particularly in cases where the shape of the fingers is crucial for differentiation. The rounded feature [°], which denotes a slight relaxation in finger posture, represents this tension. This relaxation means that joints adopt a more open position if initially closed, and vice versa.

The thumb is one of the most essential elements of HC, providing information about the form and meaning of the signs. The thumb traits are categorised into two main areas: selection [sel] and posture. Selection refers to the thumb’s active involvement in the configuration, while posture describes its position to the other fingers. The specific thumb posture traits include opposable thumb [ot], carpometacarpal joint [cmc], metacarpophalangeal joint [mcp], and interphalangeal joint [ip].

The contact between the thumb and the fingers is another trait for HC. The features active contact [ac], selected finger active in contact [sac], and the active articulator touching the passive one with the tip [t] can all describe different types of contact between the thumb and the chosen fingers.

The posture of the unselected fingers is only sometimes decisive for the sign’s meaning. However, they allow for a more detailed and precise description of the HC. When the fingers do not directly participate in the formation of the sign, their position can provide additional information. The features used to describe this posture are: unselected fingers open above [uso], unselected fingers separated above [uss], and unselected fingers rounded above [us°].

Finally, the use of diacritics such as [b, c, d, °] helps to highlight differences within the same hand configuration. These symbols indicate the position of the thumb. At the same time, [°] shows the phalanges of the fingers bent at a 45-degree angle, illustrating how the HC is represented in the manual alphabet or number system.

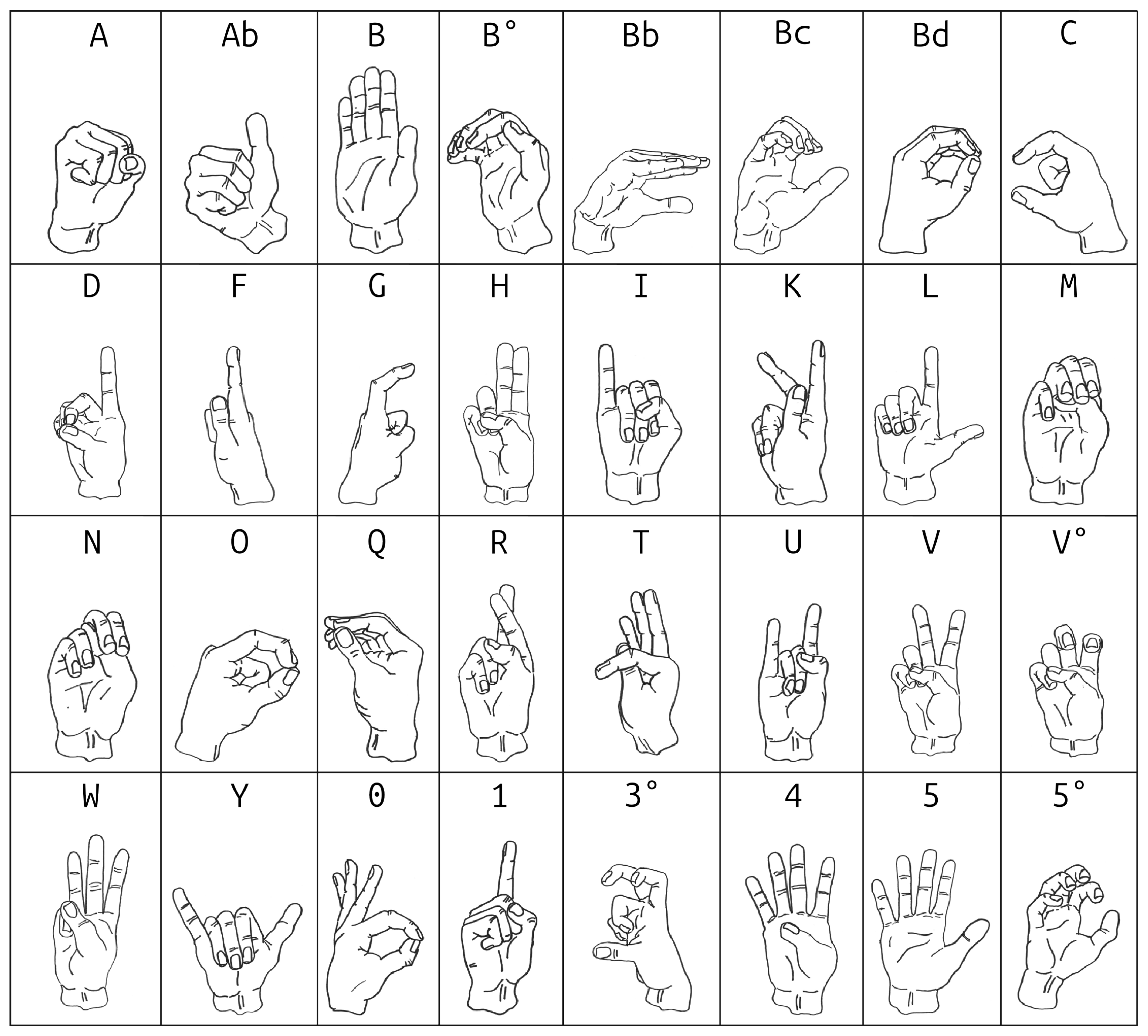

Details on this decomposition are presented in

Table 1, which lists the components of the binary descriptive traits system and their typical interpretations. A more precise visualisation of each HC is illustrated in

Figure 1, which provides a graphical representation of each configuration as a valuable tool for analysing and comparing them.

3.1.2. Orientation - OR

The hand, a primary articulating element in sign language (SL), is envisioned as a geometric solid with six defined faces, similar to a cube or block. Understanding these six sides is crucial for comprehending their orientation (OR) in space. The sides include palm, the inner part of the hand used for holding objects; back, the outer part of the hand where the knuckles are located; tips, the fingertips at the farthest extension of the hand; base, the part that connects the hand to the arm; ulna, the side of the hand closest to the pinky finger; and radius, the side of the hand closest to the thumb. These elements are fundamental for describing orientation in sign language, providing a necessary perspective that contributes to constructing essential visual grammatical elements.

The orientation of the palm is closely linked to the meanings of various signs. This is achieved through the rotation of the forearm and the positioning of the ulna and radius bones, which helps differentiate between signs that may have a similar hand configuration. These rotations can be grouped into three standard positions: neutral, with palms facing each other; prone, with palms facing down; and supine, with palms facing up. Mastering these different types of rotation enhances fluent articulation and provides a deeper understanding of the grammar and vocabulary of SL.

This study proves that the placement of different body parts and the orientation (OR) of the dominant hand to the signer’s body make it possible to tell the difference between signs. This will help us learn a lot more about the structure of sign language. A proposed transcription system employs abbreviations formed by the first three letters of each body part’s name, along with the letters [N, P, S] representing neutral, prone, and supine rotations, respectively. This notation distinguishes signs with similar hand configurations but articulated in different body areas, conveying different meanings.

Table 2 summarises this information based on forearm rotation.

3.1.3. Localisation - LO

The Localisation (LO), similar to the coordinate systems used in mathematics and other disciplines, employs a three-dimensional reference system to organise and locate signs in space. This system is built around three main axes: the vertical axis (V-LO), which uses the signer’s body to show how high or where the signs are to each other; the horizontal axis (H-LO), which is based on the transverse plane of the human body and shows MOV or UB along the lateral width; and the depth or distance axis (D-LO), which is connected to the sagittal plane and shows distances and directions forward or backward [

38,

39,

40]. In this way, SL also transmits information through the spatial relationship of gestures in a three-dimensional environment, adding a unique spatial dimension to communicative interaction.

The vertical localisation (V-LO) specifies the position where these signs are performed. Along with Hand Configuration (HC) and Movement (MOV), V-LO helps differentiate between various meanings [

38,

39,

40]. The same HC can take on different meanings based on its proximity to the body—whether it is executed close, far away, or at a specific location in the space. This highlights the significance of V-LO in meaningful construction. V-LO also defines the physical space for executing a sign and creates a symbolic space that organises the relationships between signs and their referents in a coherent and culturally specific manner. Variations in V-LO convey emotional nuances and reflect the linguistic conventions unique to each SL.

V-LO traverses the body as an essential aspect of sign articulation. The various parts of the body, from the head to the fingers, serve as reference points for producing signs. The signer’s position enhances the clarity and effectiveness of communication and conveys emotions and attitudes, contributing to the grammatical structure of SL. Additionally, the relationship between signs and the body allows them to be categorised based on whether they are performed in direct contact or within the surrounding space, always adhering to the cultural conventions of each deaf community.

The horizontal axis (H-LO) is defined through a vector system that originates from the body’s centre and extends outward to the sides. The central vector [V0], which goes through the middle of the body, and the lateral vectors [-V3, -V2, -V1] and [+V1, +V2, +V3], which are on the chest, the arms, and beyond the shoulders, respectively, make it possible to place H-LO signs in space accurately. Similarly, the depth axis (D-LO) establishes the proximity of the sign to the signer’s body, defining three degrees of amplitude. In the first degree, the hand is articulated very near [n] the body without touching it. This is used to talk about things that are close by or personal. In the second degree, the hand is articulated at a medium [m] distance from the body, about twenty centimetres away from the full extension of the open hand. This gives the speaker a moderate range of expression. In the third degree, the far [f], the hand is articulated at a distance equal to or greater than the full extension of the forearm. This is used to talk about objects, ideas, or distances. This system of spatial coordinates allows for the precise articulation of signs, even when there is no direct contact with the body or the other hand. By combining the three axes—vertical, horizontal, and distance—the spatial position of the articulating hand is accurately defined, which is fundamental for the clarity and comprehension of the signs. This use of space contributes to the richness and complexity of SL, allowing a three-dimensional representation of ideas, subjects, and actions.

This way, the LO’s vectorial representation in SL breaks down space into simple units that can be measured and analysed. This makes it possible to find patterns, differences, and linguistic universals. As shown in

Table 3, breaking the sign down into simple vectors makes it possible to transcribe the V-LO, H-LO, and D-LO parameters in great detail.

3.1.4. Movement - MOV

Just as words are the building blocks of spoken languages, movement (MOV) is one of the structural elements of SL. Each movement, with its meaning, allows the linguistic system to add nuances and depth to the message, enabling signers to express a wide range of concepts and emotions [

38,

39,

40]. The MOV is established as contour and non-contour movements, as Scott Liddell and R. E. Johnson proposed. By analysing the presence or absence of significant hand movements in space, this distinction enables a detailed examination of sign structures and identifies the unique features of each movement. Contour movements, which involve a visible displacement of the hand in space, provide information about the location (LO) of the sign; on the other hand, non-contour movements, which occur at a fixed point in space, provide information about the HC and the OR.

Contour movements involve a change in LO and are characterised by describing various trajectories. These movements include a variety of spatial patterns that allow for the precise articulation of signs. Among the most common contours are straight-line movement between two locations, which represents a direct displacement; circular trajectory, which returns to the initial location after completing the route; curved line displacement, which adds smoothness to the movement; zigzag movement, which alternates directions quickly; spiral trajectories, which describe a progressive turn; wavy contours, which mimic the movement of a wave-like surface; and movements that involve contact or brushing during the displacement, where the hand touches different points as it moves. On the other hand, non-contour movements do not involve a change in the LO but rather affect other parameters within the articulatory matrix of the SL. Three main types of these movements are changes in the HC, which involve changing the shape of the hand by moving fingers or opening the palm, which can change the meaning of the sign; changes in the relationship of the V-LO component, which involve moving the hand closer to the body or turning it in a different direction without actually moving; and oscillations, which are short movements that happen over and over again and add subtleties to the meaning of the sign.

Using MOV principles, the simplified transcription system identifies significant hand movements in space and distinguishes the unique features of each movement type. The detailed description of this transcription, which organises and standardises both types of movement, is presented in

Table 4.

3.1.5. Additional Considerations

The VSE proposes simplifying the basic units of the double articulation of SL as previously presented and introduces a system for the systematic, detailed description of signs. First, it is suggested that the execution of a sign can be split up into temporal transition spaces. This implies that each change in the sign has a unique HC and LO value and a number that increases to indicate the order of the changes. Secondly, only six basic semiotic units are considered: HC, OR, LO-V, LO-D, LO-H, and MOV. These units provide an essential structure for the semiotic analysis of SL, allowing for a standardised and simplified representation without losing the inherent complexity of the language.

Additionally, the VSE introduces the concept of mirror analysis, recognising that the active and passive hands are combined to represent most sign languages. To differentiate hand activity, the abbreviations [

A] for the active hand and [

P] for the passive hand are used. As explained in

Table 5, this method ensures symmetry and hand relationships are respected when the signs are made. This is a significant part of semiotic interpretation, and the subscript [

n] shows the change in time. Finally, we standardised the basic semiotic units in the following order: HC, OR, LO-V, LO-D, LO-H, and MOV. It should also be considered that all temporal transitions are analysed one hand at a time.

3.2. Sign Language Decoder

The Sign Language Decoding (SLD) architecture is designed to efficiently and accurately represent the complex linguistic landscape of SL. This approach utilises universal components from deep learning networks, such as Inception, ResNet, and Siamese networks [

48,

49,

50]. These architectures have revolutionised deep learning by enabling valuable insights from data. They open new avenues for modelling linguistic features applied to SL.

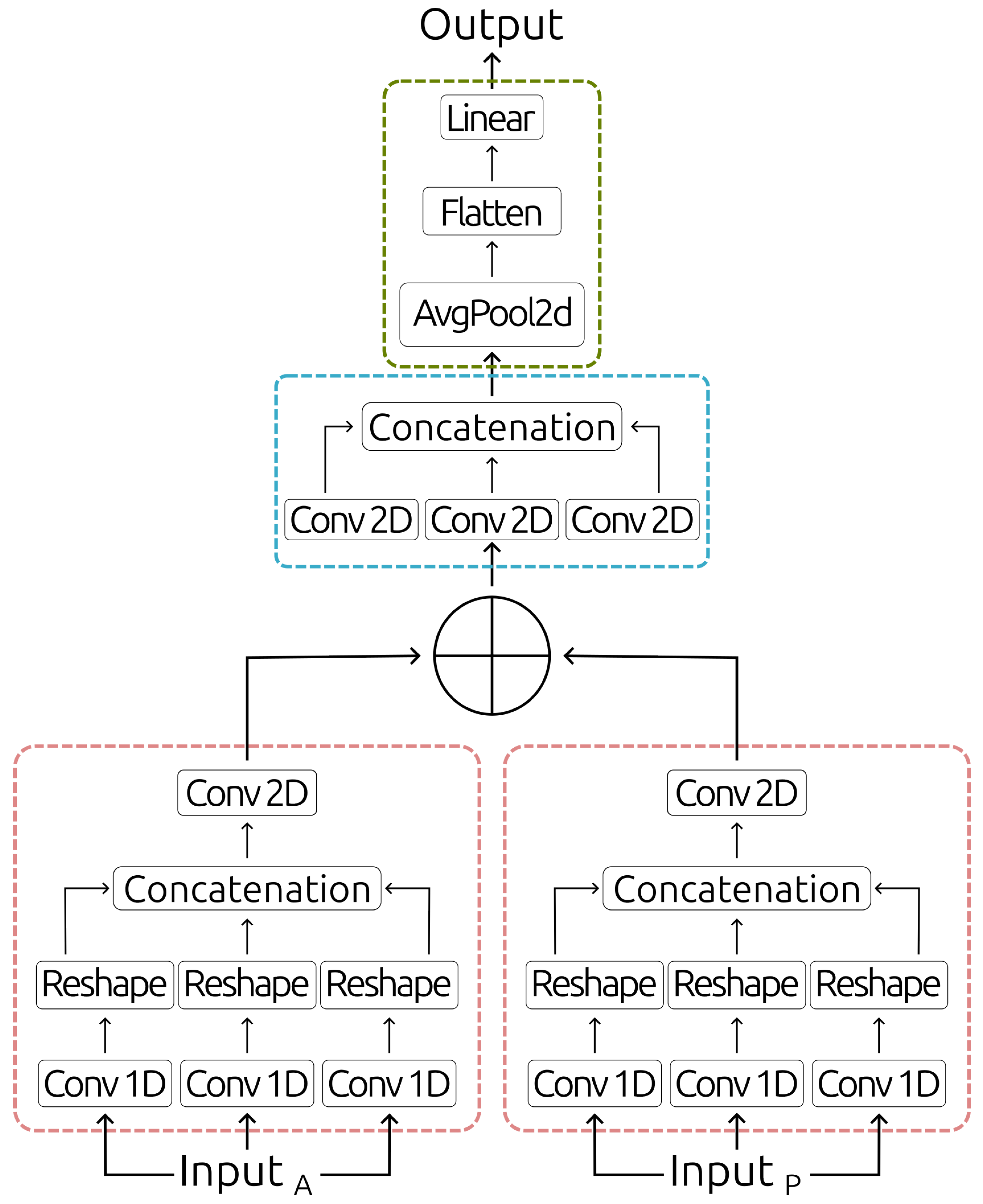

This section discusses the components of the SLD architecture, emphasising its capability to capture the semiotic complexities inherent in visual communication systems. As

Figure 2 illustrates, the SLD architecture consists of three main parts. From bottom to top, these parts are the semiotic unit analysis block, which receives the patterns from the SLVSD; the lexical comprehension block, which defines the specific lexical patterns of semiotic components; and the lexical classification block, which removes duplicate data while keeping features useful for classification. Active and passive hand features are analysed using a cell-type architecture.

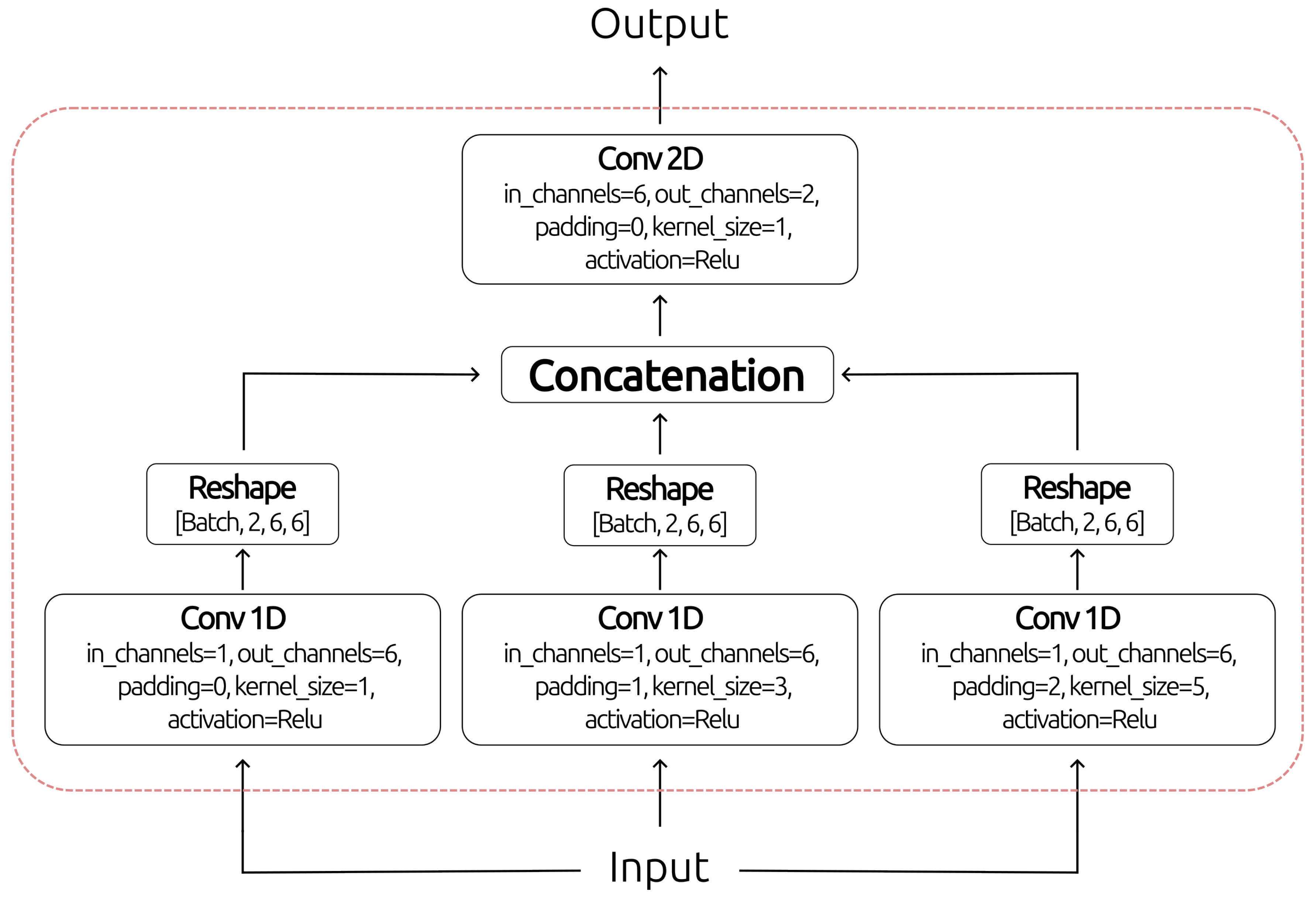

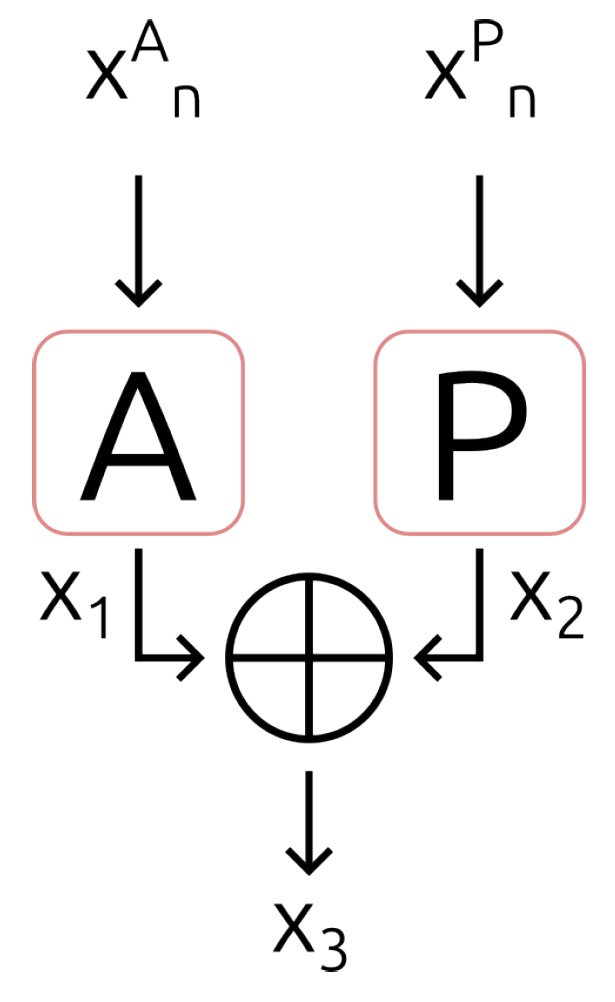

The semiotic block receives a vector of twelve features: six basic semiotic units at instant n joint with six basic semiotic units at , i.e., a temporal transition. Two blocks represent a Siamese network for both active and passive hands. This approach allows two subnetworks to share the same parameters while simultaneously processing different data, which is especially useful for comparing and analysing common elements or differences between the active and passive hands in the linguistic representation of SL.

Likewise, the Inception architecture, which uses a multidimensional filtering approach to analyse semiotic units, is part of the block. Six output channels result from crossing through three 1D convolutional units with kernel sizes one, three, and five, respectively. The 1D convolution with a kernel size of one serves as a positional reference block for basic semiotic units, making it easier to find where each part is in the space of language. The kernel size of three is for complementary relationships in the semiotic structure, focusing on unique patterns that appear from the double articulation of SL. This lets the architecture find links and slight differences between various articulatory parameters. Lastly, the five-sized kernel is used as a semiotic discrimination block to pick out differences in temporality within double articulation. This filter helps the network tell the difference between signs’ temporal changes, which makes it better at understanding transitions and order.

After that, they are reshaped to get 3D representations that include time, space, and the language relationship of the SL of size

(see

Figure 3). Thus, these outputs are concatenated to go through a 2D convolution with two output channels defining double articulation’s temporality obtained for each hand. This does volumetric minimisation, which improves spatial information processing and simplifies the features. Thus, the model focuses on how the basic semiotic units can be separated in time and show specific patterns in time and space without losing details about how the semiotic parts interact.

The SLD architecture also incorporates a residual connection similar to ResNet, as illustrated in

Figure 4. This connection is essential for solving recurrent problems such as overfitting and gradient vanishing. A residual connection lets the information flow smoothly and continuously. This makes the representation easier by combining the semiotic units’ specific time and space patterns from active and passive hands. This capability of the network to maintain data integrity enables the model to continue learning and improving without losing accuracy, even when handling complex or low-volume datasets.

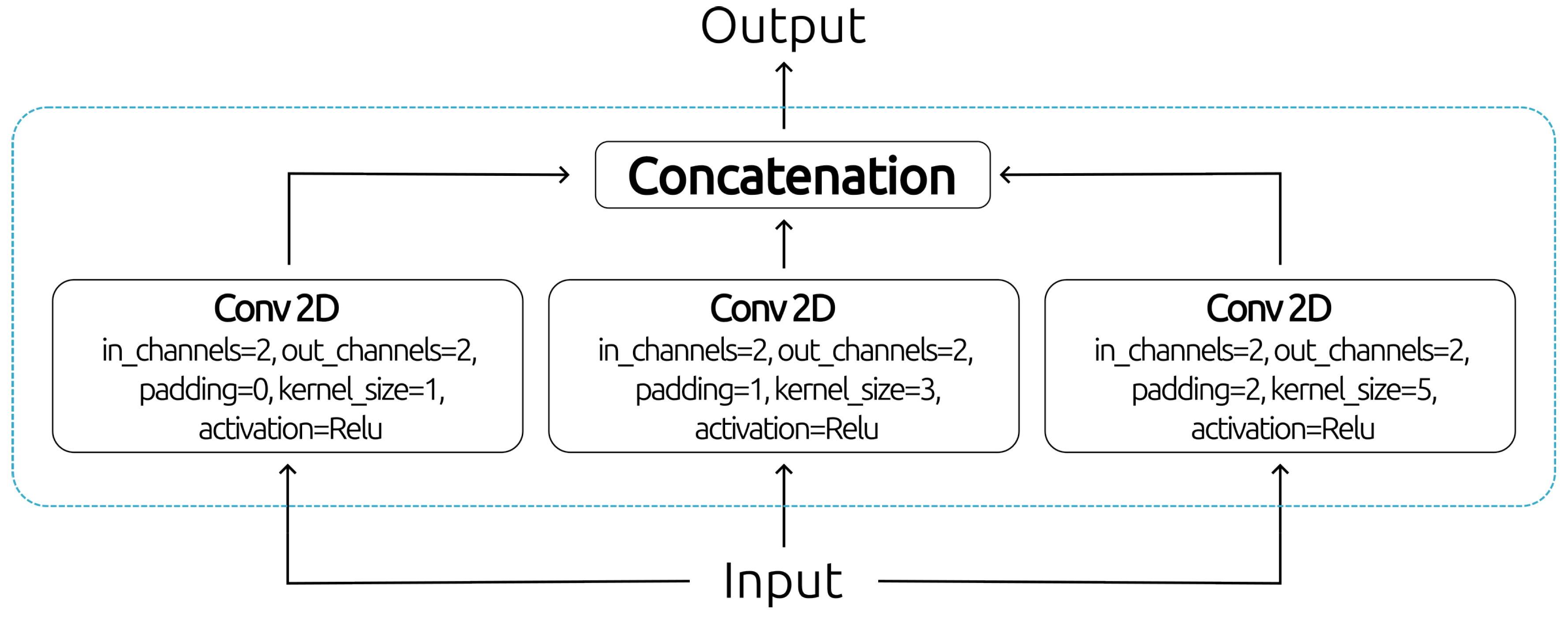

The second part of the SLD architecture adds a lexical comprehension block that works like the analysis block of basic semiotic units. It does this by using multidimensional filters in 2D convolutions with two output channels that define the specific lexical patterns of the semiotic components. There are three kernel sizes: The kernel is a positional reference block for the semiotic components, which lets you precisely map out where each component is in the lexical space. The kernel is a complementary lexical block that looks for unique patterns in the SL lexical structure. The kernel is a discriminative lexicon block to find each word’s unique patterns.

Figure 5.

The lexical comprehension block.

Figure 5.

The lexical comprehension block.

Lastly, the SLD architecture has a lexical classification block. First, this cuts down on the number of dimensions through an average pooling of

. This makes it easier to get lexical features by eliminating duplicate data and keeping the most important features for SL classification. After that, dimensional flattening is used to turn the data into a linear representation, which is then processed through a softmax layer with data about the words in the vocabulary that need to be classified. This layer ensures that signs are correctly classified within the defined lexical set. The lexical classification block is shown in

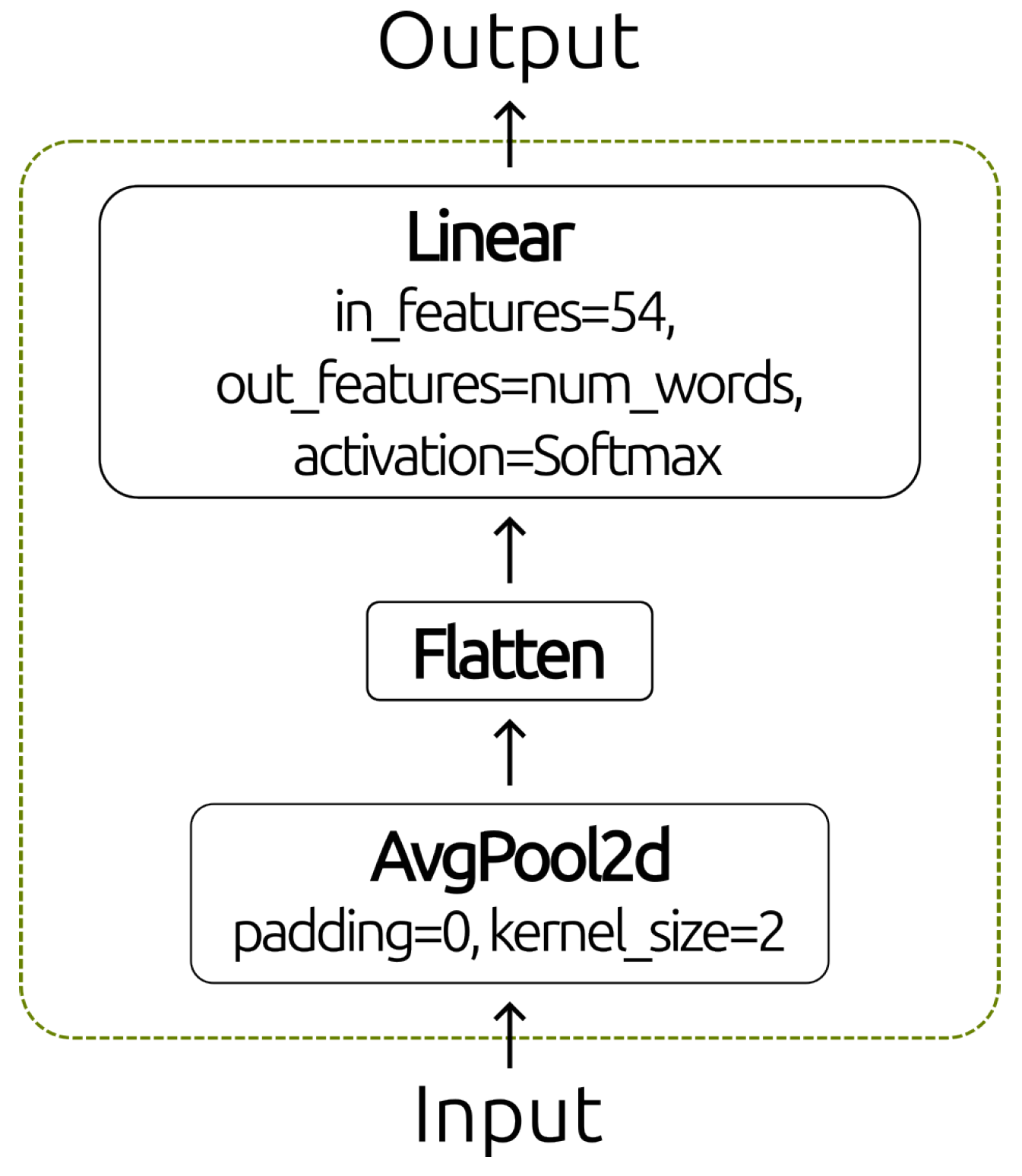

Figure 6.

4. Design of Experiments

Although the SLVSD comprises two main components, this paper only develops its second part. However, the VSE presented in the previous section, based on SL models, is robust enough to construct a dataset that adequately represents the essential semiotic features of SL. Due to the lack of a fully annotated linguistic corpus that reflected the linguistic and semiotic diversity inherent to SL, synthetic data was generated. These data only partially capture the complexity of a natural linguistic environment with all its inherent variations. Despite this, they are considered adequate for evaluating the functionality of the different components of the SLD model. Likewise, they allow for analysing how a model can establish an effective correspondence between a linguistic representation and its basic semiotic features. The experiment plan below uses the SLD model to show how well it can interpret a randomly chosen made-up language corpus of up to 1171 words.

The made-up datasets have 10, 30, 100, 150, 220, 320, 480, 700, and 1171 words from the Colombian Sign Language (CSL) dictionary [

47]. They are meant to show the words that a Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (DHH) person would use to talk to someone daily. When making semiotic features for SL words, there are a few essential things to remember to make sure the synthetic datasets are representative and make sense. First of all, both the active and passive hands are considered when executing each sign, which allows for the complexity of the double articulation characteristic of many SLs to be captured. Second, representations of null value or semiotic inactivity are excluded, meaning that all signs will have significant activity in both hands, ensuring relevant semiotic information is omitted. Third, each semiotic feature is modelled using a normal distribution. This ensures that the chances of each semiotic configuration stay the same and that the datasets accurately show how the signs are executed. Fourth, the analysis is limited to a maximum of two temporal changes per sign, simplifying the temporal modelling without compromising the model’s ability to reflect the inherent sequentiality of the signs. These considerations allow for creating a representative set of semiotic units that adequately reflect the structure and dynamics of SL. In this way, the SLD model’s validation and development process is optimised, facilitating its application in linguistic classification and decoding tasks.

4.1. Synthetic Lexical Corpus

The SLD model, designed for the lexical classification of sign language, is represented by a unit vector that labels the everyday vocabulary of a DHH person. Each hand’s associated vector contains twelve semiotic features. These characteristics encompass the six basic semiotic units in their two temporal changes

. The input subsets to the SLD model, referred to as

A (active) and

P (passive), are shown in

Table 6 to get 24 features.

The semiotic features in each synthetic dataset are encoded as positive integer values for each of the six basic semiotic units; that is, , , , , , and . These labels are nominal categorical variables representing the lexical corpus of the SL. To make the natural variations of the language more interesting, noise was added to these values, turning them from nominal to numerical to increase the representativeness and variability of the SL. Gaussian white noise was used, with a range of , where C is the number that corresponds to the category of each basic semiotic unit.

On the other hand, the unit vector that makes up the output labels is structured according to the total number of words that the model must classify. This unit vector is a categorical vector where all positions have a value of zero, except for the position representing one of the words, which takes the value of one.

Under the above considerations, one hundred fifty samples of each word were made synthetically in the new numerical representation of the features. Of these, 100 samples were used for the training set, 30 for the validation set, and 20 for the test set. After that, each basic semiotic unit is set to a standard value between 0 and 1 based on its range to train the standardised SLD model.

4.2. SLD Models

To check how robust the SLD model is, it is suggested that several models be trained with 10, 30, 100, 150, 220, 320, 480, 700, and 1171 words. This approach allows for a comprehensive view of the limitations and capabilities of the SLD model. The training of the SLD models was carried out by adjusting parameters through an iterative backpropagation process using mini-batches of 64 lexical words, in which, at each iteration, the SLD models evaluate their predictions by comparing them with the actual labels using a Binary Cross-Entropy Loss (BCE Loss) function,

where

is the true label and

is the predicted probability.

The BCE loss function, widely used in binary classification problems within deep learning, is also adaptable to multiclass classification problems, especially in multilabel scenarios. BCE loss is justifiable because it can penalise classes independently, avoiding interdependencies between predictions. This is especially useful when classes have a complex structure or are not mutually exclusive [

51,

52,

53]. It also works well for dealing with class overlap, which helps the model better understand relationships that are unclear or happen simultaneously, which can happen in some Natural Language Processing (NLP) classification problems.

All models employ the Adam optimiser—adaptive moment estimation—to complement the loss function with a learning rate set at 0.023. Adam improves training stability and ensures that models reach an optimal solution more quickly and effectively. Adam’s momentum helps accelerate convergence by smoothing out oscillations in parameter adjustment. This is crucial in NLP problems, where models often have many parameters and can face sparse or unstable gradients. Likewise, data can be noisy or complex, which could cause significant fluctuations in the training process.

L1 regularisation is also proposed, as it promotes sparsity in the model weights, forcing many of them to go to zero. This property is particularly beneficial in SL classification, as it reduces irrelevant or redundant features, making it easier for the models to focus on the most important features for the classification task. This makes it easier for the models to generalise in large datasets that are often highly correlated since different signs may share semiotic traits like movements or hand configurations. This is especially relevant in the domain of SL, where variations between gestures can be subtle and focusing on the most distinctive features is crucial for effective recognition.

4.3. Performance Metrics

To ensure successful training and guarantee the stability of the SLD models, it was decided to monitor and evaluate overall performance using two key metrics: Cohen’s Kappa Coefficient (

) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (

). These metrics were chosen because they can give a fair and accurate evaluation. For example,

is an excellent way to see how consistent the model’s predictions are with what people expect to happen. It is a more reliable measure than just accuracy because it considers the chance that matches do not happen by chance, i.e., it makes accurate and consistent predictions. Likewise,

stands out for its ability to penalise both false positives and false negatives in a balanced manner. This metric is handy in classification problems with class imbalances, as it considers all the confusion matrix values, providing a more comprehensive reflection of the model’s overall performance.

Finally, to evaluate the robustness of the SLD models, a Top-K analysis was chosen using the metrics of accuracy, precision, recall, F1-Score, and Hamming distance. These metrics were selected due to their ability to provide a detailed and comprehensive evaluation of the behaviour of models oriented towards classification tasks.

combines precision and recall into a single metric, providing a balanced view and is especially useful in scenarios with a class imbalance. And,

count the places where the SLD models’ predictions and actual results differ. This lets us determine the number of prediction mistakes for multiple classes at overlapping levels.

4.4. Other Considerations

The SLD models were implemented using Python and the PyTorch library, optimised for deep learning tasks. The process was carried out on an ASUS laptop equipped with an Intel Core i9-14900HX 32-core processor, 64 gigabytes of RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 Mobile AD103 graphics processing unit with 16 gigabytes of dedicated video memory, limited to a power of 80 Watts. Adding this GPU was crucial for speeding up matrix calculations and parallel operations, so the times reported in results depend on these hardware considerations.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. SLD Model Analysis

Various topologies can be created using the SLD model to represent SL’s made-up language space. This is done by creating artificial datasets for sorting 10, 30, 100, 150, 220, 320, 480, 700, and 1171 made-up SL words. When the SLD models were being trained, the number of epochs needed to reach convergence and the value of

corresponding to

L1 regularisation were changed. These hyperparameters are presented in

Table 7. In general, the models responsible for classifying 100, 150, 220, 320, 480, 700, and 1171 words required a similar number of epochs, while the topologies with 10 and 30 words required approximately 2.3 and 1.6 times more epochs to reach convergence. Regarding the regularisation value

, an adjustment is needed at a rate of

for each approximate increase of

100 words up to the classification model

320. For models that classify a vocabulary exceeding this amount, the adjustment of

remained constant at

. These adjustments are essential to balance the models’ complexity and generalisation capacity, ensuring that these models maintain stable performance when facing different sizes of lexical words in the SL.

5.2. Global Performance Analysis

The training of the SLD models achieved an average of 99.64% in both

and MCC, reflecting excellent consistency between the predictions and the expected results. During the validation phase, the SLD models performed well, averaging 99.58% for

and MCC. This shows that they can generalise new data well. Finally, in the testing phase, the models achieved an average of 99.65% in both

and MCC, confirming the stability of the models in SL classification.

Table 8 shows the outcomes for each model. It suggests that these models are consistent at all stages, and the semiotic representation and learning ability are good enough to handle the complexity of the SL linguistic space.

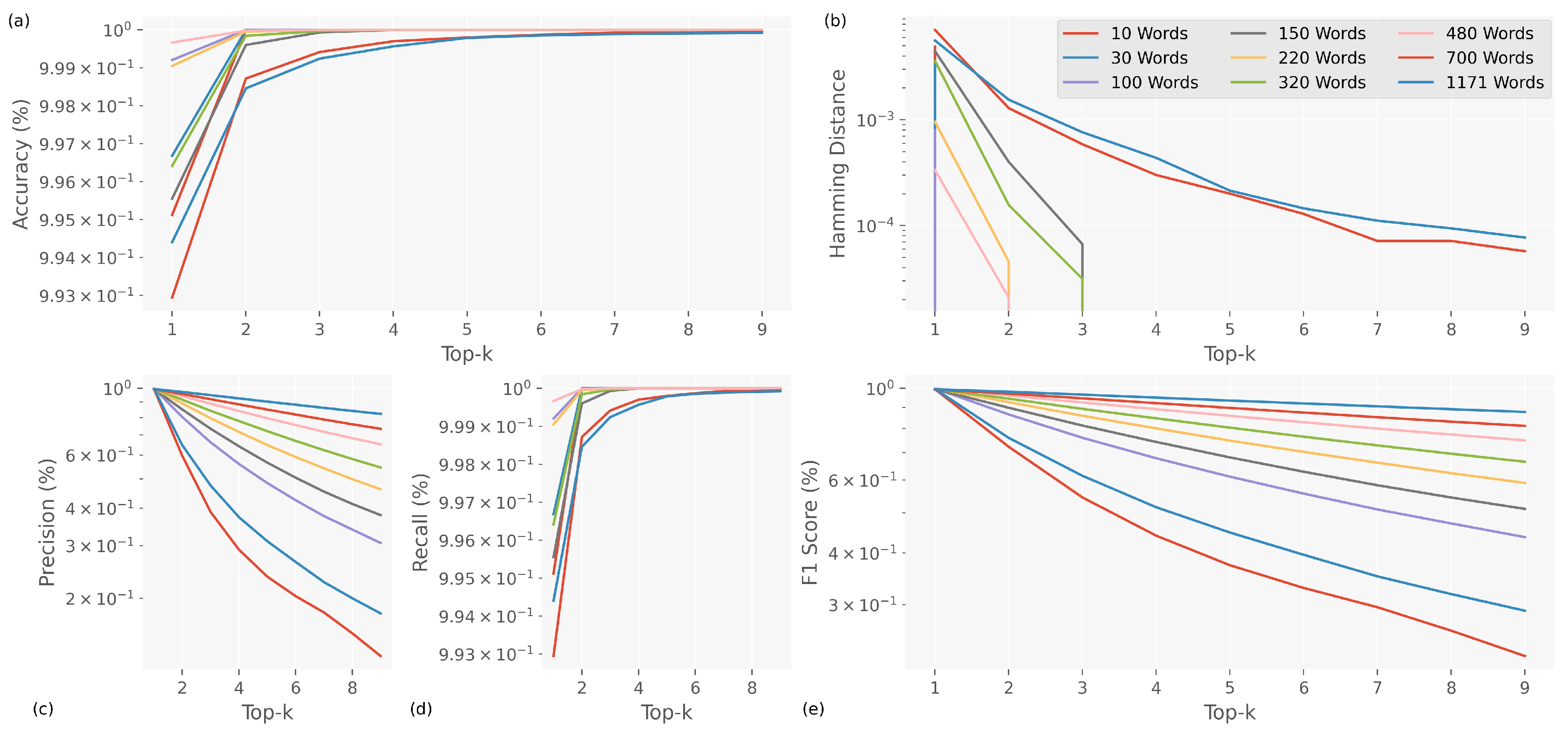

5.3. Robustness Analysis of SLD Models

We did a robustness analysis on the

Top-K metric during the training phase (see

Figure 7). We found that the SLD models are 100% accurate at classifying the

Top-3 words into the following groups: 10, 30, 100, 150, 220, 320, and 480. This result indicates that, although the models may make errors in the first prediction, the correct label is consistently found within the Top-2 most probable options. This behaviour indicates the robustness of the SLD models, as it ensures that the most relevant predictions are always within the first estimations. Another situation happens for classification models for 700 and 1171 words that reach their best performance at 99.28% and 99.43% accuracy starting from the

Top-5. This behaviour may be related to the added complexity of handling an intermediate set of classes, which makes it more challenging to identify the correct label.

The results can also be seen in the Hamming distance, showing that the differences between the predicted and correct labels get smaller as the analysis reaches the top of the Top-K metric. This shows that even though the models might have trouble classifying correctly on the first try due to an error in a semiotic transcription, they can still find the correct label from a smaller set of options.

Consequently, during training, the accuracy exhibited a particular behaviour, as increasing the number of classes to classify improved its performance within the Top-2. This result suggests that SLD models are robust enough to predict relevant labels, even in highly dense and complex corpora. Despite the increase in classes, the models maintain their ability to identify the most probable labels in the initial estimates accurately.

Recall demonstrated a performance of 100% for classification models of 10, 30, 100, 150, 220, 320, and 480 words within the Top-3, indicating that these models are capable of correctly detecting all positive instances within that range. For the 700- and 1171-word classification models, recall is best starting from the Top-5. This shows that the medium and high complexity of the dataset has a negligible effect on the position of the correct label, even though it is one of the best choices.

The F1-Score metric exhibited behaviour similar to precision, showing significant improvements as the number of classes increased, reflecting an adequate balance between precision and sensitivity. This shows that SLD models can maintain high accuracy in correct predictions, reducing false positives and false negatives. This ensures that the quality of predictions is maintained in various classification situations involving different numbers of SL words.

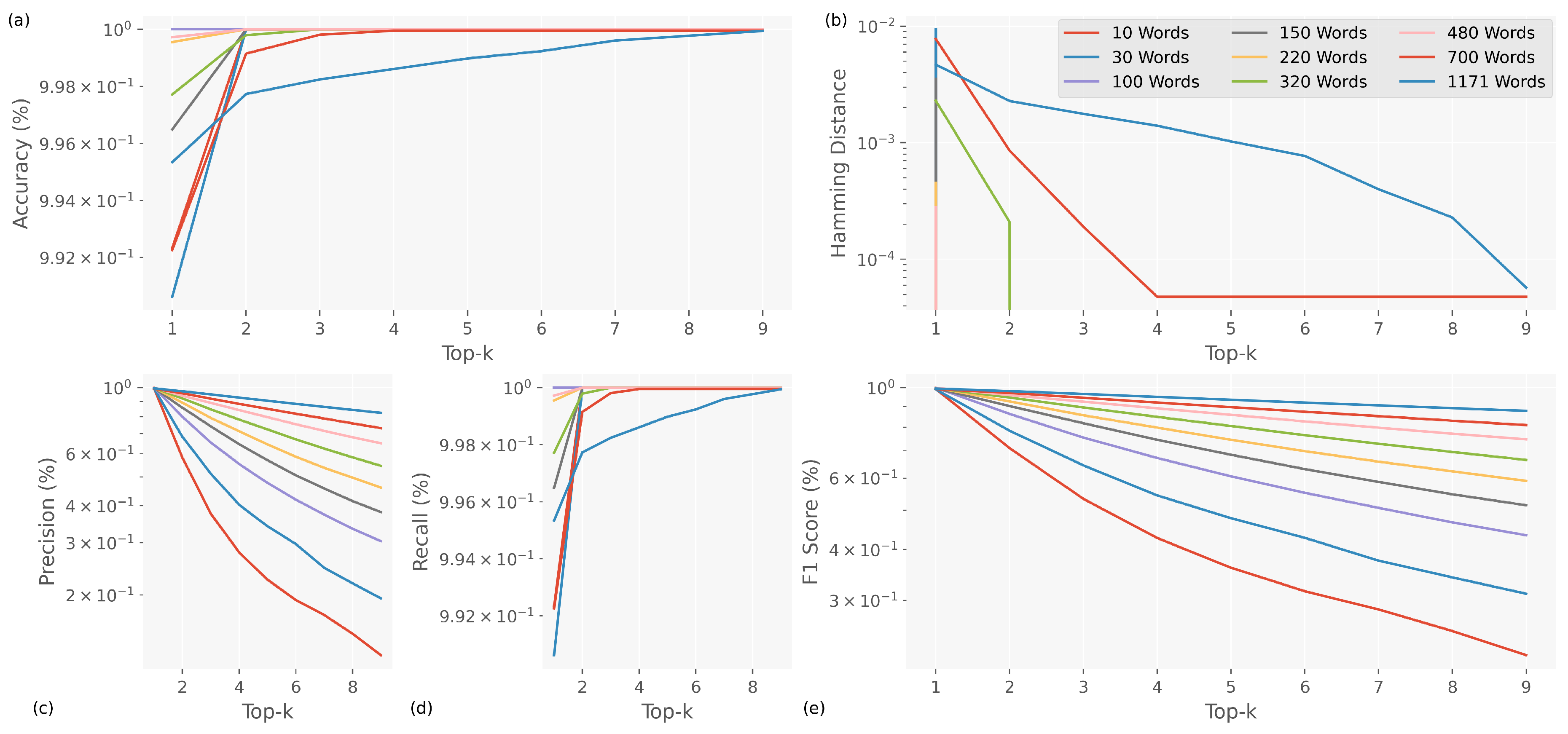

In the case of the

Top-K analysis during the validation phase (see

Figure 8), it exhibited behaviour almost identical to that observed during training. This demonstrates that the models achieved excellent generalisation of the semiotic features of SL, suggesting that they could adapt correctly to previously unseen data.

This consistent performance shows how strong the SLD models are; they can handle the inherent variability of synthetic data while still being accurate and able to classify things in new situations. The fact that the results from training and validation are similar supports the idea that the models do not overfit and instead do an excellent job of adapting to different datasets. This is important for ensuring they can be used in real-life situations where SL is used for linguistic classification.

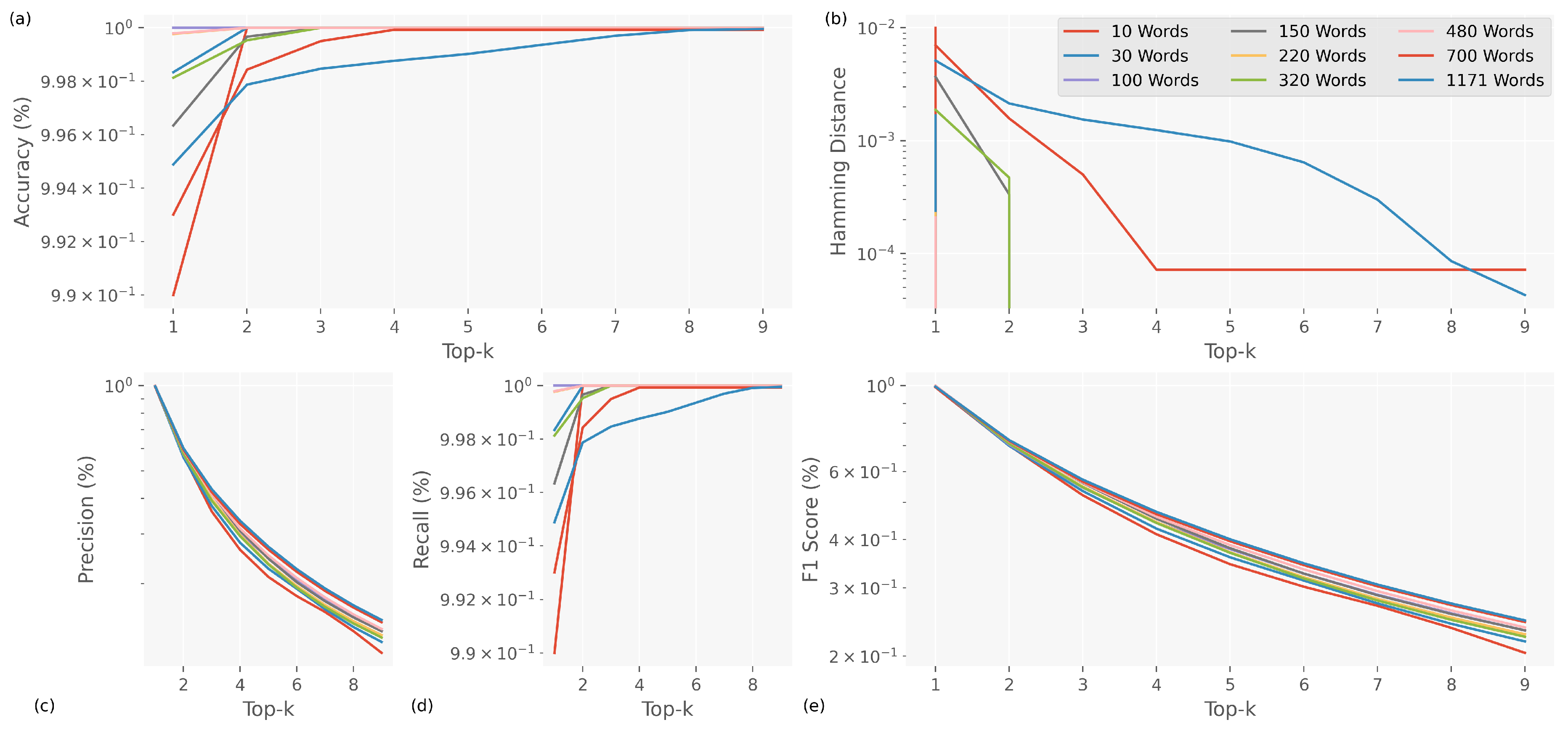

Last but not least, looking at

Top-K during the testing phase showed that the SLD models for 10, 30, 100, 150, 220, 320, and 480 words could reach 100% accuracy as it is shown in

Figure 9. This behaviour indicates the effectiveness of SLD models in reducing classification errors and maintaining the relevance of predictions. This performance is also reflected in the Hamming distance metric, as reaching the

Top-2 results in the difference between the correct label and the predictions being equal to zero. This suggests that, in those cases, there are no significant errors in the Top-2 options, which reinforces confidence in the model’s accuracy within that range.

Other results showed that some classes overlapped, especially in the 700 and 1171 models. It might be harder to tell some data groups apart because their meanings are so similar. The Hamming distance shows that these models frequently perform at their best in the Top-4 and above the Top-10. However, implementing preventive measures, such as ongoing validation of the Hamming distance, can reduce these overlaps. By monitoring this metric, it is possible to determine whether the correct label is in the first or second position, which allows for adjusting the final accuracy of the system and reducing errors in the most critical predictions. This strategy ensures that, even when the model faces difficulties in assigning the correct label in the first prediction, it continues to offer highly reliable results by relying on the most probable estimates. This reinforces the system’s robustness for real-world applications, where consistency and accuracy in classification are essential.

The accuracy analysis revealed that, within the Top-2, the SLD models achieved an accuracy close to 60% during the tests. This suggests that the models can find the relevant label among the Top-2 most probable options more than half the time. Although they do not always assign the correct label initially, the most relevant predictions are present within the top options, indicating good performance. Additionally, the sensitivity was 100% within the Top-2 estimations, showing that the models can correctly find all positive cases between the first two estimations. This indicates that the models can accurately capture even the most subtle changes in the data, responding adequately to variations in the signs and ensuring correct identification within a narrow range of predictions. This behaviour was also reflected in the F1-Score metric, where the models achieved a performance close to 70%. This value indicates a satisfactory balance between precision and recall, ensuring that the correct label is present within the top possibilities in many cases.

These results confirm the effectiveness of SLD models in making consistent and high-quality predictions, especially in classification scenarios with multiple classes or similar signals. Offering precise results within a limited set of options is essential for their application in linguistic classification systems, where accuracy in the initial estimates is crucial to improving the usability and reliability of the solutions.

6. Conclusions

The proposal of the visual semiotic encoder is presented as an innovative technique for transcribing sign language by breaking it down into six fundamental semiotic units. First, the hand configuration (HC) unit organises 32 differentiated configurations through 24 descriptive elements, facilitating the classification of different hand positions. Next, the orientation (OR) unit describes the direction of the palm based on the traits of the forearm and the position of the ulna and radius, allowing for an accurate description of the spatial orientation of the signs. With three units, the localisation represents the space in which the signs are made in the vertical (V-LO), depth (D-LO), and horizontal (H-LO) planes to reflect the spatial position of the hand to the body. Lastly, the movement (MOV) unit groups both the paths of displacement and the small changes in one place. This gives a complete picture of the movements and transitions accompanying each hand configuration, making the transcription more accurate and valuable for sign language translation.

The experiments consisted of sorting sign language (SL) words with numbers 10, 30, 100, 150, 220, 320, 480, 700, and 1171 into groups, the SLD architecture created several models that could accurately reflect the made-up language space of SL. It was crucial to make specific adjustments to the number of iterations and the value () of the L1 regularisation for the models to converge optimally. Notably, models designed for classifying 10 and 30 words required more iterations to converge than the others, indicating a higher complexity associated with smaller sets. Also, changing the regularisation parameter based on the vocabulary size made it easier to control how complicated the model was while keeping its generalisation ability. This shows how important it is to fine-tune parameters so that SLD models can correctly depict semiotic relationships in different synthetic SL datasets.

The results illustrate that models based on the SLD architecture demonstrate excellent accuracy, consistency, and generalisation performance. The high performance of the and MCC metrics across training, validation, and testing data indicates that these models successfully capture and represent the linguistic complexities of SL. The low variability between phases and the stability in classification further suggest that the models learn effectively and maintain robustness when confronted with new data. This indicates that the SLD architecture is highly suitable for SL translation and recognition applications in real-world environments.

The Top-K metric analysis showed that the models could correctly identify the expected label within the top options, with 100% of accuracy within the Top-2 and Top-3 for most datasets and above the Top-5 for the classification model of 700 and 1171 words. This suggests that the correct labels are consistently found within the highest probability despite the difficulties in predicting accurately at first glance. In addition, models do not overfit and can adequately adapt to new data because the accuracy, recall, and F1-Score metrics stay mostly the same between the training and validation data. The reduction in Hamming distance as the Top-K range is expanded supports the ability of SLD models to minimise significant errors in the top prediction options.

Lastly, the SLD architecture creates systems that can translate the semiotic features used in this method a prior because it positions itself as an effective and flexible way to recognise and classify signs. In this sense, it will be essential to have advanced computer vision systems to detect HC precisely. Likewise, systems capable of performing a landmark estimation will be required to capture the LO units, which is crucial for understanding the relative position of the hands and their relationship with the body and the surrounding space. Optical flow systems will also be needed to study the MOV unit, making it easier to keep track of gestures and how they change over time. These parts will work together to make the Visual Semiotic Encoder architecture, which will help read signs more accurately and quickly. This will improve recognition and move us closer to automatic and real-time transcription of SL.

It is also necessary to thoroughly analyse the semiotic units in a real SL to deeply understand the patterns and groupings shared by the different families of signs. This analysis is essential to ensure a more faithful and accurate representation of the linguistic space of SL, especially when designing generative systems or synthetic models of linguistic corpora. The detailed study of semiotic units allows for identifying regularities and variations among signs belonging to the same category or grouped into related linguistic families. This makes it easier to describe the signs in a more organised way and makes it easier to make computer models that can accurately represent the complicated way that meaning and syntax interact in an SL. So, having a deep knowledge of semiotic units and how they relate is essential for accurately representing SL and making progress in technologies that include everyone, like automatic translation systems, sign synthesis, and other algorithms that make SL easier to access and use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.J.R. and W.A.; Methodology, J.J.R. and W.A.; Software, J.J.R. and W.A.; Validation, J.J.R. and W.A.; Formal Analysis, J.J.R. and W.A.; Investigation, J.J.R. and W.A.; Resources, J.J.R. and W.A.; Data Curation, J.J.R.; Writing–Original Draft Preparation, J.J.R. and W.A.; Writing–Review & Editing, J.J.R. and W.A.; Visualisation, J.J.R. and W.A.; Supervision, W.A; Project Administration, W.A.; Funding Acquisition, W.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Vice-Rectory of Research at the Universidad del Valle supported this research under the Master Students Support Call No. 148-2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the Perception and Intelligent Systems research group for providing the installations to perform this study, as well as the Vice-Rectory of Research for their financial support in publishing this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stuart-Fox, M. Major Transitions in Human Evolutionary History. World Futures 2022, 79, 29–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Marcos, A.; de Viñaspre, O.P.; Labaka, G. A survey on Sign Language machine translation. Expert Systems With Applications 2023, 213, 118–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.K.; Chalupny, J.; Grote, K.; Huckauf, A. How sign language expertise can influence the effects of face masks on non-linguistic characteristics. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Goyal, V.; Goyal, L. Comparative Analysis of Translation Systems from Indian Languages to Indian Sign Language. SN Computer Science 2022, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.C.; Kuhl, P.K. Development of infants’ neural speech processing and its relation to later language skills: A MEG study. NeuroImage 2022, 256, 119242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H.; Bank, W. World report on disability, 2011. ISBN: 978-92-4-156418-2.

- Organization, W.H. World report on hearing; World Health Organization, 2021; pp. xiv, 252 p. ISBN: 978-92-4-002048-1.

- Martínez, J.L.A.; López, M.A.; Mayas, J.C.A.; Nicólas, M.B.S.; Ceballos, M.I.C.; Hermoso, C.C.; Melgar, M.I.C.; Albero, M.I.F.; Ibáñez, P.G.; Perales, F.J.G.; et al. Manual for students with specific educational support needs arising from hearing impairment; Consejería de educación, Dirección General de Participación e Innovación Educativa, 2008. 978-84-691-8127-0. Spanish.

- Zahid, H.; Rashid, M.; Hussain, S.; Azim, F.; Syed, S.A.; Saad, A. Recognition of Urdu sign language: a systematic review of the machine learning classification. PeerJ Computer Science 2022, 8, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassim, M.R.; Parry, J.; Pantanowitz, A.; Rubin, D.M. Design and construction of a cost-effective, portable sign language to speech translator. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2022, 30, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, G.S.X.; Xavier, E.W.S.N.; Fidalgo, S.S. Deadly silence: the (lack of) access to information by deaf Brazilians in the context of Covid-19 pandemic. DELTA: Documentação de Estudos em Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada 2022, 38-1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlilah, U.; Prasetyo, R.; Mahamad, A.; Handaga, B.; Saon, S.; Sudarmilah, E. Modelling of basic Indonesian Sign Language translator based on Raspberry Pi technology. Scientific and Technical Journal of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics 2022, 22, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.S.; Rizvi, S.T.H. Sign Gesture Classification and Recognition Using Machine Learning. Cybernetics and Systems 2022, 54, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Thakur, N.; Bansal, D.; Chaudhary, G.; Davaasambuu, B.; Hua, Q. CNN-LSTM Hybrid Real-Time IoT-Based Cognitive Approaches for ISLR with WebRTC: Auditory Impaired Assistive Technology. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2022, 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2017, pp. 5967–5976. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, R.A.; Chen, C.; Lim, T.Y.; Schwing, A.G.; Hasegawa-Johnson, M.; Do, M.N. Semantic Image Inpainting with Deep Generative Models. 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2017, pp. 6882–6890. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhao, B.; Liang, J.; Lu, F.; Yang, W.; Xu, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z. Low hysteresis, water retention, anti-freeze multifunctional hydrogel strain sensor for human-machine interfacing and real-time sign language translation. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 3856–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemu, M.Y.; Lin, Y.; Shull, P.B. EchoGest: Soft Ultrasonic Waveguides Based Sensing Skin for Subject-Independent Hand Gesture Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2024, 32, 2366–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Luo, X.; Song, Z.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, G. Ultra-Robust and Sensitive Flexible Strain Sensor for Real-Time and Wearable Sign Language Translation. Advanced Functional Materials 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaim, A.I.M.; Sazali, N.; Kadirgama, K.; Jamaludin, A.S.; Turan, F.M.; Razak, N.A. Smart Glove for Sign Language Translation. Journal of Advanced Research in Applied Mechanics 2024, 112, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Fan, D.; Lin, J.; Feng, H.; Wang, H.; Dai, J.S. Machine-Learning-Assisted Soft Fiber Optic Glove System for Sign Language Recognition. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonugur, G.; Cayli, A. Turkish sign language recognition using fuzzy logic asisted ELM and CNN methods. Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems 2023, 45, 8553–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gupta, R.; Kumar, A. A TinyML solution for an IoT-based communication device for hearing impaired. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 246, 123147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Hernández, H.; Muñoz-Jiménez, V.; Ramos-Corchado, M.A. Translation of Mexican sign language into Spanish using machine learning and internet of things devices. Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics 2024, 13, 3369–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltem Eryilmaz, E.B.E.U.G.T.; Oral, S.G. Machine vs. deep learning comparision for developing an international sign language translator. Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 2024, 36, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Ali, A.H.; Sabri, A.A. Enhancing communication: Deep learning for Arabic sign language translation. Open Engineering 2024, 14, 20240025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, J.R.; Córdova-Esparza, D.M.; Terven, J.; Romero-González, J.A. Towards a Bidirectional Mexican Sign Language–Spanish Translation System: A Deep Learning Approach. Technologies 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teran-Quezada, A.A.; Lopez-Cabrera, V.; Rangel, J.C.; Sanchez-Galan, J.E. Sign-to-Text Translation from Panamanian Sign Language to Spanish in Continuous Capture Mode with Deep Neural Networks. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushal Das, F.A.J.R.K.T.A.S.A.S.S. Enhancing Communication Accessibility: UrSL-CNN Approach to Urdu Sign Language Translation for Hearing-Impaired Individuals. Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2024, 141, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Bessmertny, I.A. ViSL One-shot: generating Vietnamese sign language data set. Scientific and Technical Journal of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics 2024, 24, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Baek, H. Preprocessing for Keypoint-Based Sign Language Translation without Glosses. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, K.M.; Kamat, P.; Patil, S.; Jayaswal, R.; Ahirrao, S.; Kotecha, K. Gesture-to-Text Translation Using SURF for Indian Sign Language. Applied System Innovation 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, F.M.; El-Shafai, W.; Soliman, N.F.; Algarni, A.D.; Abd El-Samie, F.E.; Siam, A.I. Real-time Arabic avatar for deaf-mute communication enabled by deep learning sign language translation. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2024, 119, 109475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, D.T.; Nasef, N.A.; Lotfy, M.A.; Abohany, A.A.; Essa, R.M.; Salem, A. A real-time Arabic avatar for deaf - mute community using attention mechanism. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 21709–21723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Trigo, M.; Celia, B.L.; del Amor; Miguel Ángel, M.; Álvarez García; Juan Antonio.; Miguel, S.M.L.; José, V.O.J. Synthetic Corpus Generation for Deep Learning-Based Translation of Spanish Sign Language. Sensors 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Singla, V.; Bawa, S.; Singh, J. Improving accuracy using ML/DL in vision based techniques of ISLR. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 20677–20698, Cited by: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlin, M.; Majchrowska, S.; Plantykow, M.; Kwaśniewska, A.; Mikołajczyk-Bareła, A.; Olech, M.; Nalepa, J. Quantifying inconsistencies in the Hamburg Sign Language Notation System. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 256, 124911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naert, L.; Larboulette, C.; Gibet, S. A survey on the animation of signing avatars: From sign representation to utterance synthesis. Computers & Graphics 2020, 92, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, A. Notes for a Grammar of Colombian Sign Language. Spanish.

- Oviedo, A. Classifiers in Venezuelan Sign Language; Signum Verlag, 2006. ISBN: 978-3-927731-94-3.

- Capirci, O.e.a. Signed Languages: A Triangular Semiotic Dimension. Frontiers in psychology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor H, C.K. Sociolinguistic Variation in Mouthings in British Sign Language: A Corpus-Based Study. Lang Speech 2023, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmelman, V.e.a. Exploring Networks of Lexical Variation in Russian Sign Language. Frontiers in psychology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokoe, William C., J. Sign Language Structure: An Outline of the Visual Communication Systems of the American Deaf. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 2005, 10, 3–37. [CrossRef]

- Klima, E.; Bellugi, U. The Signs of Language; Harvard University Press, 1988. ISBN: 978-0674807969.

- Butcher, C.; Goldin-Meadow, S., Gesture and the transition from one- to two-word speech: when hand and mouth come together. In Language and Gesture; Language Culture and Cognition, Cambridge University Press, 2000; pp. 235–258. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional para Sordos - INSOR.; Instituto Caro y Cuervo. Basic Dictionary of Colombian Sign Language, 2011. Spanish. Available online: https://www.insor.gov.co/descargar/diccionario_basico_completo.pdf.

- K, A.; P, P.; Poonia, R.C. LiST: A Lightweight Framework for Continuous Indian Sign Language Translation. Information 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, B.M.; Jamal, A.T.; Al Khuzayem, L.A.; Alsaedi, O.A. An End-to-End Scene Text Recognition for Bilingual Text. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölücü, N.; Can, B.; Artuner, H. A Siamese Neural Network for Learning Semantically-Informed Sentence Embeddings. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 214, 119103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaiah, K.; Bolla, B.K. Aspect category learning and sentimental analysis using weakly supervised learning. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 235, 1246–1257, International Conference on Machine Learning and Data Engineering (ICMLDE 2023). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lim, H.S. Neural Network With Binary Cross Entropy for Antenna Selection in Massive MIMO Systems: Convolutional Neural Network Versus Fully Connected Network. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 111410–111421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, T.; Wu, X.; Hua, X.S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Q. Class Re-Activation Maps for Weakly-Supervised Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022; pp. 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Essential visual grammatical elements for the hand configuration. Adapted from [

39,

40,

47]

Figure 1.

Essential visual grammatical elements for the hand configuration. Adapted from [

39,

40,

47]

Figure 2.

Sign Language Decoder (bottom to top): red dashed line, the semiotic block; blue dashed line, the lexical comprehension block; and green dashed line, the lexical classification block.

Figure 2.

Sign Language Decoder (bottom to top): red dashed line, the semiotic block; blue dashed line, the lexical comprehension block; and green dashed line, the lexical classification block.

Figure 3.

The semiotic unit analysis block.

Figure 3.

The semiotic unit analysis block.

Figure 4.

Residual connection between active and passive processing. Here is the twelve features (six from time n and six from time ) for the hand h, with .

Figure 4.

Residual connection between active and passive processing. Here is the twelve features (six from time n and six from time ) for the hand h, with .

Figure 6.

The lexical classification block.

Figure 6.

The lexical classification block.

Figure 7.

Top-K analysis in the training stage for SLD models. (a) Accuracy analysis, (b) Hamming distance analysis, (c) Precision analysis, (d) Recall analysis, and (e) the F1-score analysis.

Figure 7.

Top-K analysis in the training stage for SLD models. (a) Accuracy analysis, (b) Hamming distance analysis, (c) Precision analysis, (d) Recall analysis, and (e) the F1-score analysis.

Figure 8.

Top-K analysis in the validation data for SLD models. (a) Accuracy analysis, (b) Hamming distance analysis, (c) Precision analysis, (d) Recall analysis, and (e) the F1-score analysis.

Figure 8.

Top-K analysis in the validation data for SLD models. (a) Accuracy analysis, (b) Hamming distance analysis, (c) Precision analysis, (d) Recall analysis, and (e) the F1-score analysis.

Figure 9.

Top-K analysis in the test data for SLD models. (a) Accuracy analysis, (b) Hamming distance analysis, (c) Precision analysis, (d) Recall analysis, and (e) the F1-score analysis.

Figure 9.

Top-K analysis in the test data for SLD models. (a) Accuracy analysis, (b) Hamming distance analysis, (c) Precision analysis, (d) Recall analysis, and (e) the F1-score analysis.

Table 1.

The sign language visual semiotic encoder traits for the hand configuration.

Table 1.

The sign language visual semiotic encoder traits for the hand configuration.

| HC |

Formational |

Posture |

Interaction |

Ten |

Thumb |

Contact |

Unselected |

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

usf |

mcp |

pip |

dip |

sep |

|

|

stk |

° |

sel |

ot |

cmc |

mcp |

ip |

ac |

sac |

t |

uso |

uss |

us° |

| A |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ab |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| B |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| B° |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bb |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

| Bc |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bd |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

| D |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| F |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| G |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| H |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |