Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. The Mice Model

2.3. DSS Induced IBD

2.5. Blood Cell Count (CBC)

2.6. Assessment of Inflammatory Process by Mesenteric Lymph Nodes (MLN) WBC Cellularity

2.7. Assessment of the Severity of Inflammatory Processes by Neutrophil Activity by Myeloperoxisdase (MPO) Assay in Colon Samples

2.8. Colon Histology

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

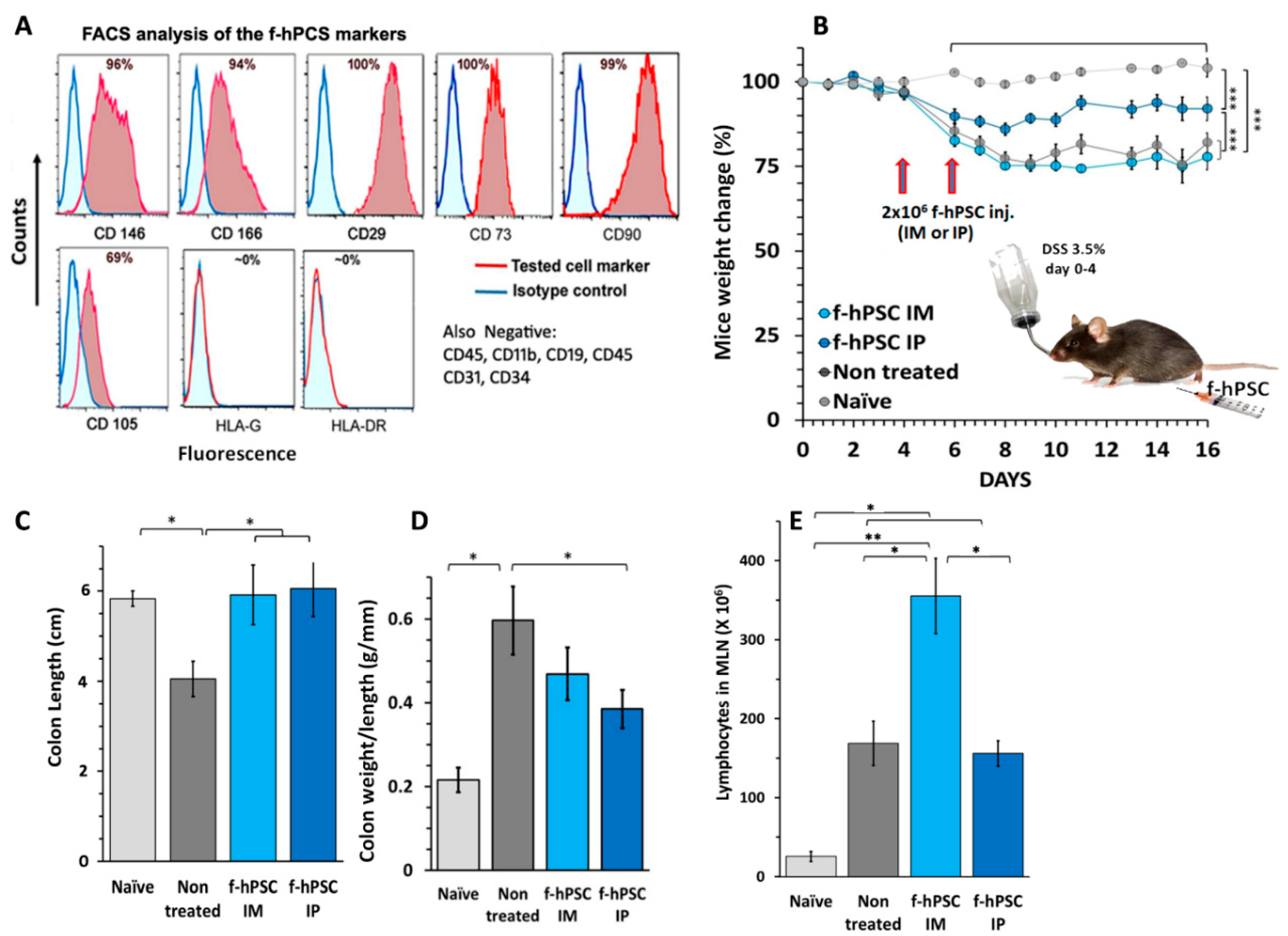

3.1. Characterization of the f-hPSCs

3.2. DSS Induced of IBD

3.3. The Influence of f-hPSCs Injection on the Mice Colon

3.4. The Influence of f-hPSCs Treatments on the Total MLN Cell Counts

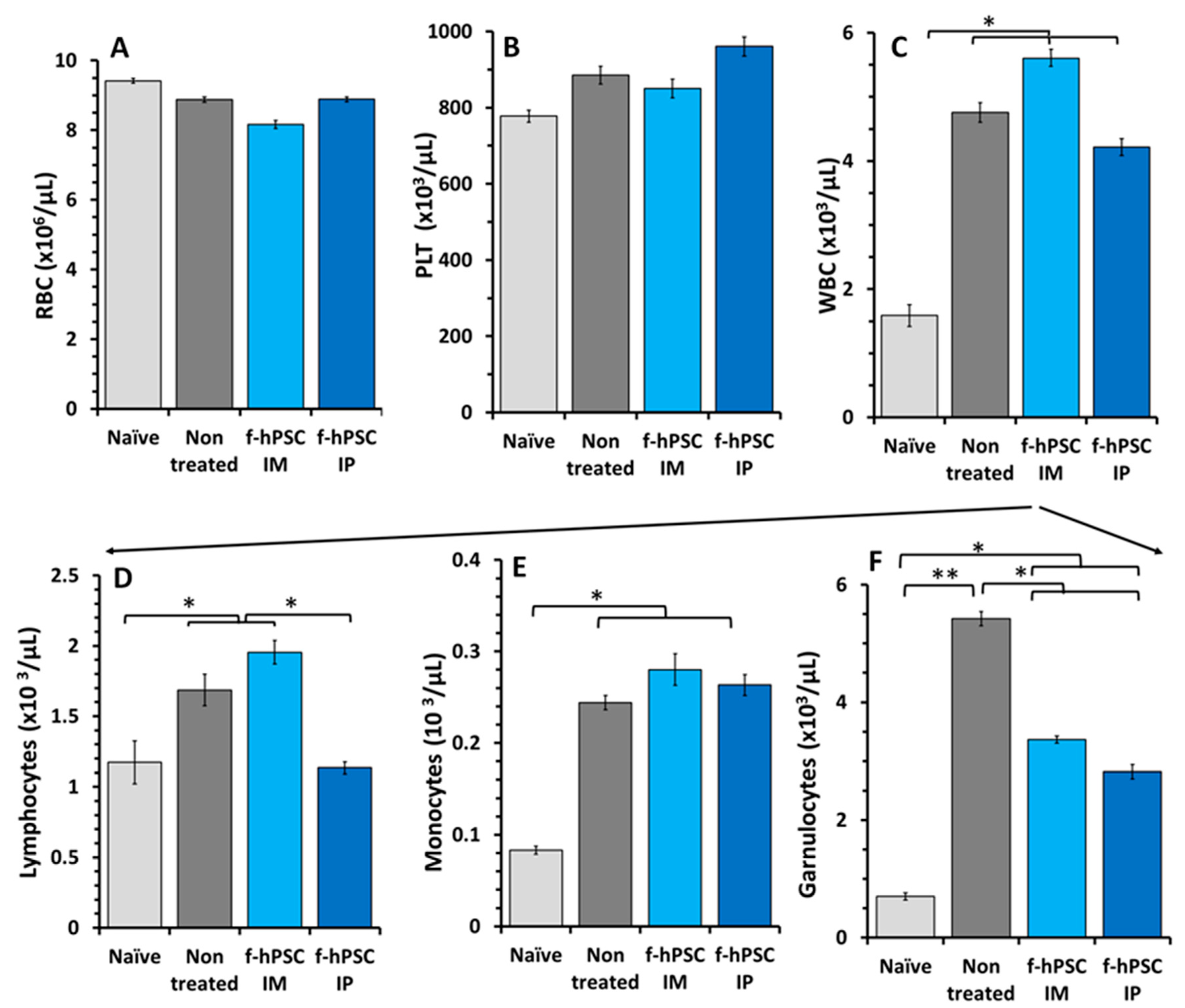

3.5. Effect of the DSS and f-hPSCs Treatments on the Peripheral Blood Cells Counts

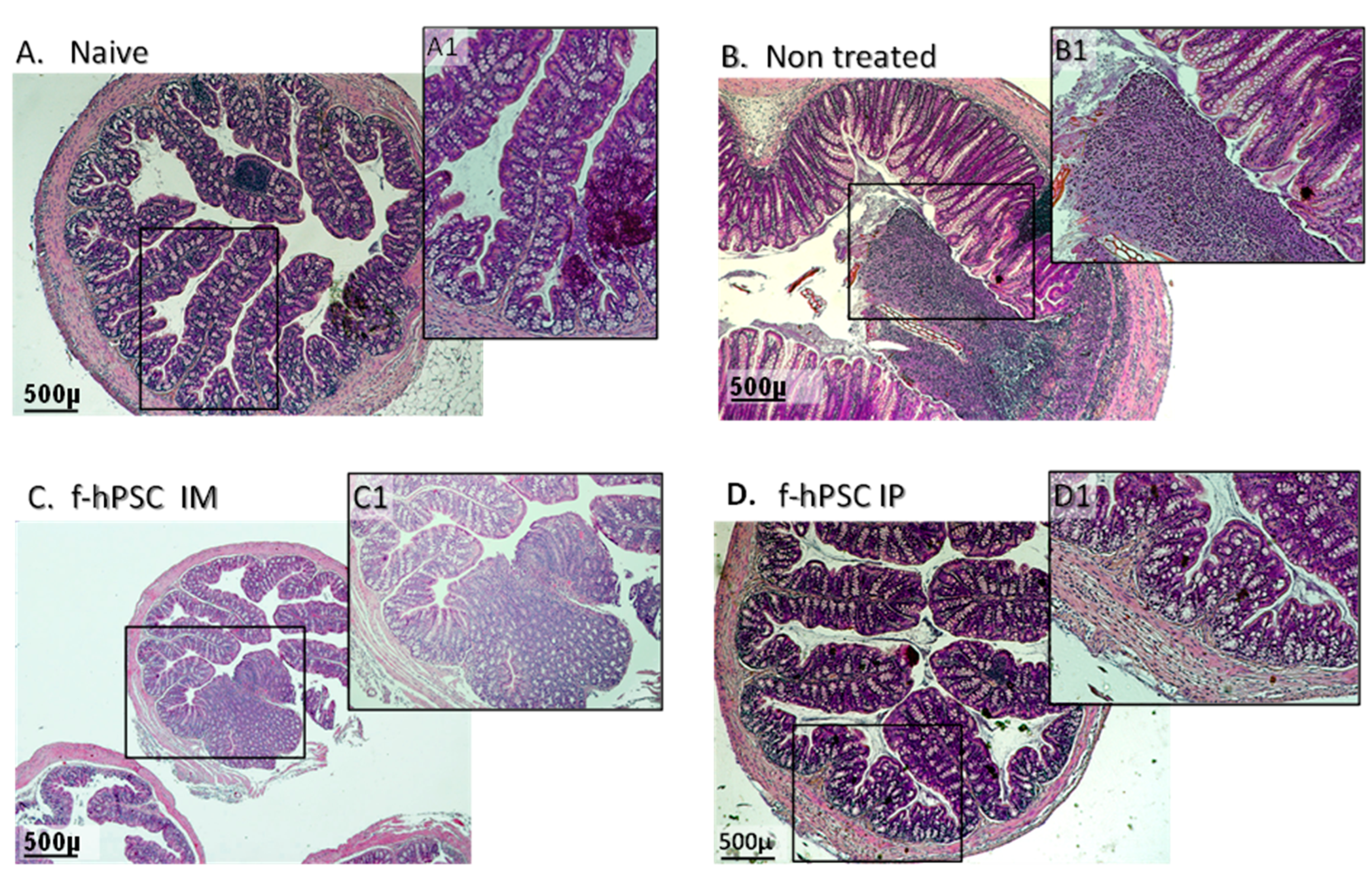

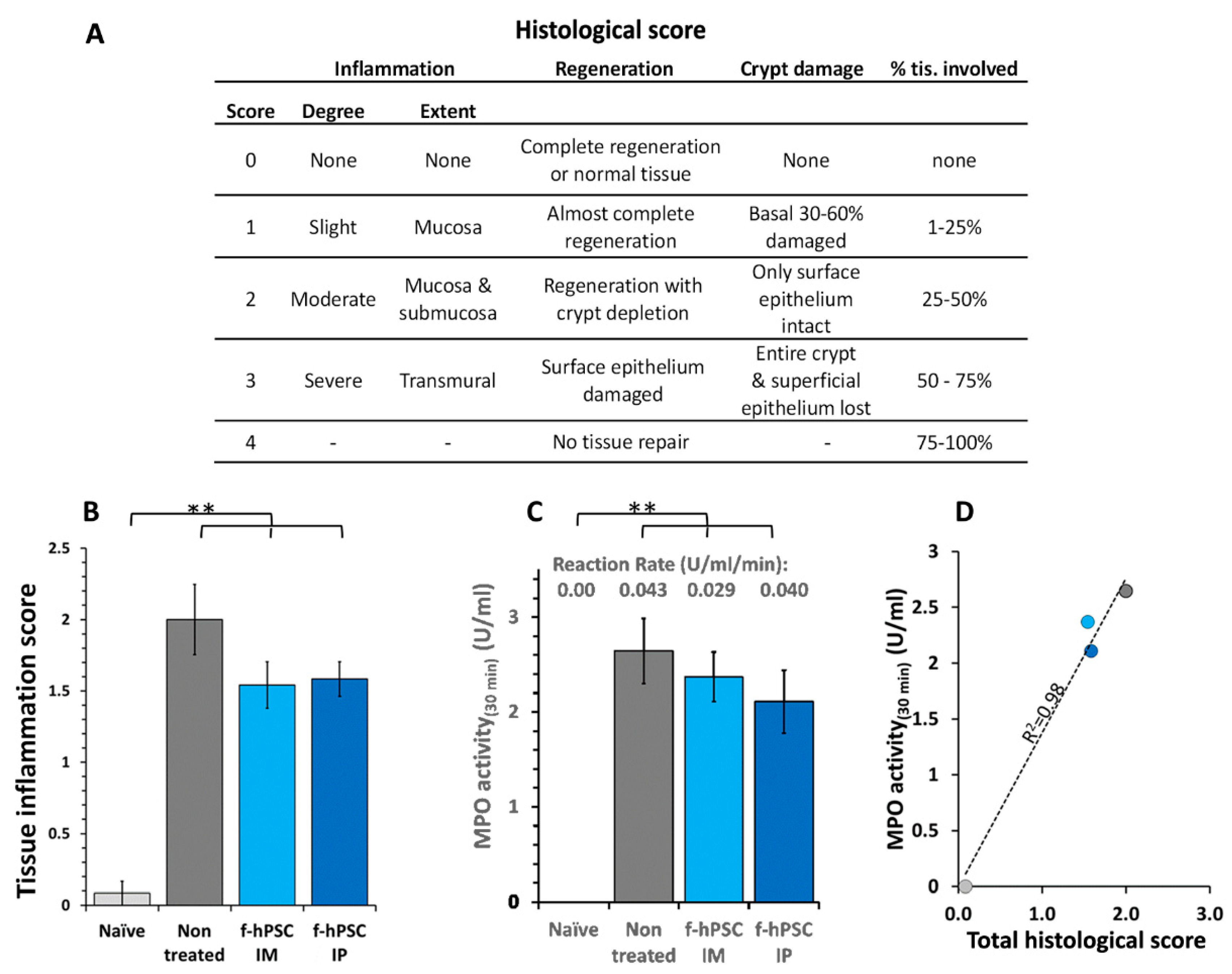

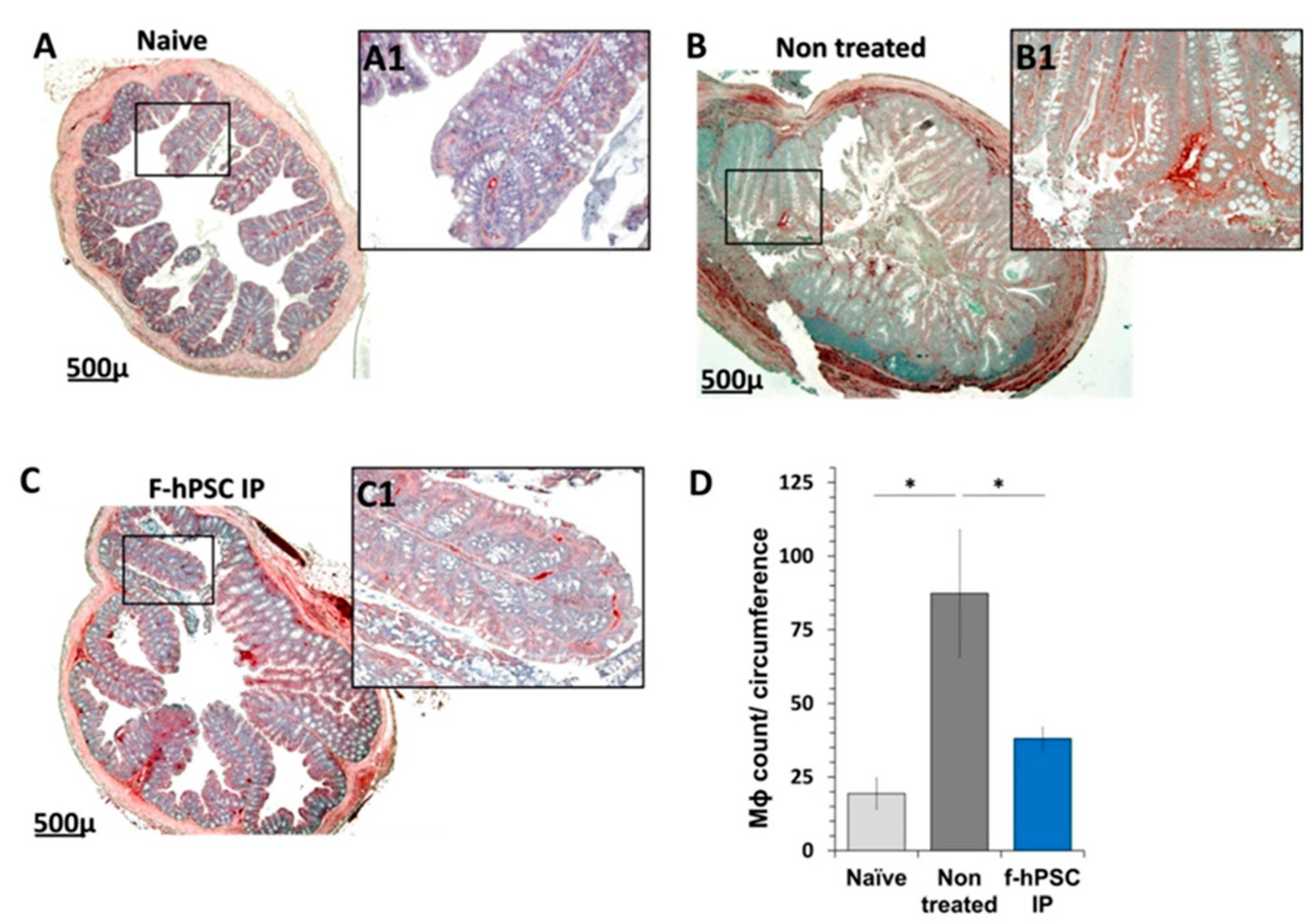

3.6. Colon Histology

3.7. MPO Assay for Neutrophils Density

4. Discussion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hold, G. L., Smith, M., Grange, C., Watt, E. R., El-Omar, E. M., and Mukhopadhya, I. (2014) Role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: what have we learnt in the past 10 years?, World journal of gastroenterology 20, 1192-12.10.

- Strober, W. (2013) Impact of the gut microbiome on mucosal inflammation, Trends Immunol 34, 423-430.

- Singh, S., Andersen, N. N., Andersson, M., Loftus, E. V., Jr., and Jess, T. (2018) Comparison of infliximab with adalimumab in 827 biologic-naive patients with Crohn's disease: a population-based Danish cohort study, Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 47, 596-604.

- Feagan, B. G., Rutgeerts, P., Sands, B. E., Hanauer, S., Colombel, J. F., Sandborn, W. J., Van Assche, G., Axler, J., Kim, H. J., Danese, S., Fox, I., Milch, C., Sankoh, S., Wyant, T., Xu, J., Parikh, A., and Group, G. S. (2013) Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis, The New England journal of medicine 369, 699-710.

- Mishra, R., Dhawan, P., Srivastava, A. S., and Singh, A. B. (2020) Inflammatory bowel disease: Therapeutic limitations and prospective of the stem cell therapy, World journal of stem cells 12, 1050-1066.

- Mayer, L., Pandak, W. M., Melmed, G. Y., Hanauer, S. B., Johnson, K., Payne, D., Faleck, H., Hariri, R. J., and Fischkoff, S. A. (2013) Safety and tolerability of human placenta-derived cells (PDA001) in treatment-resistant crohn's disease: a phase 1 study, Inflammatory bowel diseases 19, 754-760.

- Pak, S., Hwang, S. W., Shim, I. K., Bae, S. M., Ryu, Y. M., Kim, H. B., Do, E. J., Son, H. N., Choi, E. J., Park, S. H., Kim, S. Y., Park, S. H., Ye, B. D., Yang, S. K., Kanai, N., Maeda, M., Okano, T., Yang, D. H., Byeon, J. S., and Myung, S. J. (2018) Endoscopic Transplantation of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Sheets in Experimental Colitis in Rats, Scientific reports 8, 11314.

- Liao, Y., Lei, J., Liu, M., Lin, W., Hong, D., Tuo, Y., Jiang, M. H., Xia, H., Wang, M., Huang, W., and Xiang, A. P. (2016) Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Mitigate Experimental Colitis via Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 7-mediated Immunosuppression, Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 24, 1860-1872.

- Melmed, G. Y., Pandak, W. M., Casey, K., Abraham, B., Valentine, J., Schwartz, D., Awais, D., Bassan, I., Lichtiger, S., Sands, B., Hanauer, S., Richards, R., Oikonomou, I., Parekh, N., Targan, S., Johnson, K., Hariri, R., and Fischkoff, S. (2015) Human Placenta-derived Cells (PDA-001) for the Treatment of Moderate-to-severe Crohn's Disease: A Phase 1b/2a Study, Inflamm Bowel Dis 21, 1809-1816.

- Trebol, J., Georgiev-Hristov, T., Pascual-Miguelanez, I., Guadalajara, H., Garcia-Arranz, M., and Garcia-Olmo, D. (2022) Stem cell therapy applied for digestive anastomosis: Current state and future perspectives, World journal of stem cells 14, 117-141.

- Caplan, A. I. (2017) Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Time to Change the Name!, Stem cells translational medicine 6, 1445-1451.

- Gaberman, E., Pinzur, L., Levdansky, L., Tsirlin, M., Netzer, N., Aberman, Z., and Gorodetsky, R. (2013) Mitigation of Lethal Radiation Syndrome in Mice by Intramuscular Injection of 3D Cultured Adherent Human Placental Stromal Cells, PloS one 8, e66549.

- Lee, R. H., Pulin, A. A., Seo, M. J., Kota, D. J., Ylostalo, J., Larson, B. L., Semprun-Prieto, L., Delafontaine, P., and Prockop, D. J. (2009) Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6, Cell stem cell 5, 54-63.

- Pampalone, M., Corrao, S., Amico, G., Vitale, G., Alduino, R., Conaldi, P. G., and Pietrosi, G. (2021) Human Amnion-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Cirrhotic Patients with Refractory Ascites: A Possible Anti-Inflammatory Therapy for Preventing Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis, Stem cell reviews and reports 17, 981-998.

- Duan, L., Huang, H., Zhao, X., Zhou, M., Chen, S., Wang, C., Han, Z., Han, Z. C., Guo, Z., Li, Z., and Cao, X. (2020) Extracellular vesicles derived from human placental mesenchymal stem cells alleviate experimental colitis in mice by inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress, International journal of molecular medicine 46, 1551-1561.

- Eiro, N., Fraile, M., Gonzalez-Jubete, A., Gonzalez, L. O., and Vizoso, F. J. (2022) Mesenchymal (Stem) Stromal Cells Based as New Therapeutic Alternative in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Basic Mechanisms, Experimental and Clinical Evidence, and Challenges, International journal of molecular sciences 23.

- Fu, Y., Zhang, C., Xie, H., Wu, Z., Tao, Y., Wang, Z., Gu, M., Wei, P., Lin, S., Li, R., He, Y., Sheng, J., Xu, J., Wang, J., and Pan, Y. (2023) Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviated TNBS-induced colitis in mice by restoring the balance of intestinal microbes and immunoregulation, Life sciences 334, 122189.

- Ke, C., Biao, H., Qianqian, L., Yunwei, S., and Xiaohua, J. (2015) Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases: promise and challenge, Current stem cell research & therapy 10, 499-508.

- Lightner, A. L., Irving, P. M., Lord, G. M., and Betancourt, A. (2024) Stem Cells and Stem Cell-Derived Factors for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease with a Particular Focus on Perianal Fistulizing Disease: A Minireview on Future Perspectives, BioDrugs 38, 527-539.

- Bandzar, S., Gupta, S., and Platt, M. O. (2013) Crohn's disease: a review of treatment options and current research, Cellular immunology 286, 45-52.

- Cao, X., Duan, L., Hou, H., Liu, Y., Chen, S., Zhang, S., Liu, Y., Wang, C., Qi, X., Liu, N., Han, Z., Zhang, D., Han, Z. C., Guo, Z., Zhao, Q., and Li, Z. (2020) IGF-1C hydrogel improves the therapeutic effects of MSCs on colitis in mice through PGE(2)-mediated M2 macrophage polarization, Theranostics 10, 7697-7709.

- Adani, B., Basheer, M., Hailu, A. L., Fogel, T., Israeli, E., Volinsky, E., and Gorodetsky, R. (2019) Isolation and expansion of high yield of pure mesenchymal stromal cells from fresh and cryopreserved placental tissues, Cryobiology 89, 100-103.

- Pinzur, L., Akyuez, L., Levdansky, L., Blumenfeld, M., Volinsky, E., Aberman, Z., Reinke, P., Ofir, R., Volk, H. D., and Gorodetsky, R. (2018) Rescue from lethal acute radiation syndrome (ARS) with severe weight loss by secretome of intramuscularly injected human placental stromal cells, J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 9, 1079-1092.

- El-Nakeep, S. (2022) Stem Cell Therapy for the Treatment of Crohn's Disease; Current Obstacles and Future Hopes, Current stem cell research & therapy 17, 727-733.

- Volinsky, E., Lazmi-Hailu, A., Cohen, N., Adani, B., Faroja, M., Grunewald, M., and Gorodetsky, R. (2020) Alleviation of acute radiation-induced bone marrow failure in mice with human fetal placental stromal cell therapy, Stem Cell Res Ther 11, 337.

- Bai, K., Li, X., Zhong, J., Ng, E. H. Y., Yeung, W. S. B., Lee, C. L., and Chiu, P. C. N. (2021) Placenta-Derived Exosomes as a Modulator in Maternal Immune Tolerance During Pregnancy, Frontiers in immunology 12, 671093.

- Amend, B., Buttgereit, L., Abruzzese, T., Harland, N., Abele, H., Jakubowski, P., Stenzl, A., Gorodetsky, R., and Aicher, W. K. (2023) Regulation of Immune Checkpoint Antigen CD276 (B7-H3) on Human Placenta-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in GMP-Compliant Cell Culture Media, International journal of molecular sciences 24.

- Shapira, I., Fainstein, N., Tsirlin, M., Stav, I., Volinsky, E., Moresi, C., Ben-Hur, T., and Gorodetsky, R. (2016) Placental Stromal Cell Therapy for Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis: The Role of Route of Cell Delivery, Stem cells translational medicine.

- Adani, B., Sapir, E., Volinsky, E., Lazmi-Hailu, A., and Gorodetsky, R. (2022) Alleviation of Severe Skin Insults Following High-Dose Irradiation with Isolated Human Fetal Placental Stromal Cells, International journal of molecular sciences 23.

- Abumaree, M. H., Al Jumah, M. A., Kalionis, B., Jawdat, D., Al Khaldi, A., AlTalabani, A. A., and Knawy, B. A. (2013) Phenotypic and functional characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from chorionic villi of human term placenta, Stem cell reviews 9, 16-31.

- Perse, M., and Cerar, A. (2012) Dextran sodium sulphate colitis mouse model: traps and tricks, Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology 2012, 718617.

- Chassaing, B., Aitken, J. D., Malleshappa, M., and Vijay-Kumar, M. (2014) Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice, Current protocols in immunology 104, Unit 15 25.

- Abomaray, F. M., Al Jumah, M. A., Alsaad, K. O., Jawdat, D., Al Khaldi, A., AlAskar, A. S., Al Harthy, S., Al Subayyil, A. M., Khatlani, T., Alawad, A. O., Alkushi, A., Kalionis, B., and Abumaree, M. H. (2016) Phenotypic and Functional Characterization of Mesenchymal Stem/Multipotent Stromal Cells from Decidua Basalis of Human Term Placenta, Stem cells international 2016, 5184601.

- Galvez, J. (2014) Role of Th17 Cells in the Pathogenesis of Human IBD, ISRN inflammation 2014, 928461.

- Yi, Q., Wang, J., Song, Y., Guo, Z., Lei, S., Yang, X., Li, L., Gao, C., and Zhou, Z. (2019) Ascl2 facilitates IL-10 production in Th17 cells to restrain their pathogenicity in inflammatory bowel disease, Biochemical and biophysical research communications 510, 435-441.

- Riddell, M. R., Winkler-Lowen, B., Chakrabarti, S., Dunk, C., Davidge, S. T., and Guilbert, L. J. (2012) The characterization of fibrocyte-like cells: a novel fibroblastic cell of the placenta, Placenta 33, 143-150.

- Zhao, Y., Gillen, J. R., Harris, D. A., Kron, I. L., Murphy, M. P., and Lau, C. L. (2014) Treatment with placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells mitigates development of bronchiolitis obliterans in a murine model, The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 147, 1668-1677 e1665.

- Shin, S., Lee, J., Kwon, Y., Park, K. S., Jeong, J. H., Choi, S. J., Bang, S. I., Chang, J. W., and Lee, C. (2021) Comparative Proteomic Analysis of the Mesenchymal Stem Cells Secretome from Adipose, Bone Marrow, Placenta and Wharton's Jelly, International journal of molecular sciences 22.

- Pinzur, L., Akyuez, L, Levdansky L.,Blumenfeld,M, Volinsky,E, Aberman,Z, Reinke,P, Ofir,R, Volk,HD, Gorodetsky,R. (2018) Rescue from lethal acute radiation syndrome (ARS) with severe weight loss by secretome of intramuscularly injected human placental stromal cells, Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle (in press).

- Lahiani, A., Zahavi, E., Netzer, N., Ofir, R., Pinzur, L., Raveh, S., Arien-Zakay, H., Yavin, E., and Lazarovici, P. (2015) Human placental eXpanded (PLX) mesenchymal-like adherent stromal cells confer neuroprotection to nerve growth factor (NGF)-differentiated PC12 cells exposed to ischemia by secretion of IL-6 and VEGF, Biochimica et biophysica acta 1853, 422-430.

- Petrou, P., Gothelf, Y., Argov, Z., Gotkine, M., Levy, Y. S., Kassis, I., Vaknin-Dembinsky, A., Ben-Hur, T., Offen, D., Abramsky, O., Melamed, E., and Karussis, D. (2016) Safety and Clinical Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Secreting Neurotrophic Factor Transplantation in Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Results of Phase 1/2 and 2a Clinical Trials, JAMA neurology 73, 337-344.

- Shapira, I., Fainstein, N., Tsirlin, M., Stav, I., Volinsky, E., Moresi, C., Ben-Hur, T., and Gorodetsky, R. (2017) Placental Stromal Cell Therapy for Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis: The Role of Route of Cell Delivery, Stem cells translational medicine 6, 1286-1294.

- Adams, K. M., Yan, Z., Stevens, A. M., and Nelson, J. L. (2007) The changing maternal "self" hypothesis: a mechanism for maternal tolerance of the fetus, Placenta 28, 378-382.

- Chang, C. J., Yen, M. L., Chen, Y. C., Chien, C. C., Huang, H. I., Bai, C. H., and Yen, B. L. (2006) Placenta-derived multipotent cells exhibit immunosuppressive properties that are enhanced in the presence of interferon-gamma, Stem cells 24, 2466-2477.

- Gorodetsky, R., and Aicher, W. K. (2021) Allogenic Use of Human Placenta-Derived Stromal Cells as a Highly Active Subtype of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Cell-Based Therapies, International journal of molecular sciences 22.

- Maier, C. L., and Pober, J. S. (2011) Human placental pericytes poorly stimulate and actively regulate allogeneic CD4 T cell responses, Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 31, 183-189.

- Forbes, G. M. (2017) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Crohn's Disease, Dig Dis 35, 115-122.

- Macholdova, K., Machackova, E., Proskova, V., Hromadnikova, I., and Klubal, R. (2019) Latest findings on the placenta from the point of view of immunology, tolerance and mesenchymal stem cells, Ceska gynekologie / Ceska lekarska spolecnost J. Ev. Purkyne 84, 154-160.

- Magatti, M., De Munari, S., Vertua, E., Gibelli, L., Wengler, G. S., and Parolini, O. (2008) Human amnion mesenchyme harbors cells with allogeneic T-cell suppression and stimulation capabilities, Stem cells 26, 182-192.

- Wang, Y., Zhao, X., Li, Z., Wang, W., Jiang, Y., Zhang, H., Liu, X., Ren, Y., Xu, X., and Hu, X. (2024) Decidual natural killer cells dysfunction is caused by IDO downregulation in dMDSCs with Toxoplasma gondii infection, Commun Biol 7, 669.

- Li, C., Zhang, W., Jiang, X., and Mao, N. (2007) Human-placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit proliferation and function of allogeneic immune cells, Cell and tissue research 330, 437-446.

- Liu, W., Morschauser, A., Zhang, X., Lu, X., Gleason, J., He, S., Chen, H. J., Jankovic, V., Ye, Q., Labazzo, K., Herzberg, U., Albert, V. R., Abbot, S. E., Liang, B., and Hariri, R. (2014) Human placenta-derived adherent cells induce tolerogenic immune responses, Clinical & translational immunology 3, e14.

- Wang, Q., Liu, T., Zhang, Y., Chen, D., Wang, L., Li, Y., and Wei, J. (2013) [Immunomodulatory effects of human placental-derived mesenchymal stem cells on immune rejection in mouse allogeneic skin transplantation], Zhongguo xiu fu chong jian wai ke za zhi = Zhongguo xiufu chongjian waike zazhi = Chinese journal of reparative and reconstructive surgery 27, 775-780.

- Kshirsagar, S. K., Alam, S. M., Jasti, S., Hodes, H., Nauser, T., Gilliam, M., Billstrand, C., Hunt, J. S., and Petroff, M. G. (2012). Immunomodulatory molecules are released from the first trimester and term placenta via exosomes, Placenta 33, 982-990.

- Ouyang, Y., Mouillet, J. F., Coyne, C. B., and Sadovsky, Y. (2014) Review: placenta-specific microRNAs in exosomes - good things come in nano-packages, Placenta 35 Suppl, S69-73.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).