1. Introduction

The adrenal cortex has a dynamic cellular structure capable of self-renewal throughout life: aging cells are replaced by new ones, and metabolism along with the width of functional zones are regulated to meet the physiological need for steroids or to respond adequately to external pharmacological stimuli. Renewal of the adrenal cortex occurs both as a result of damage and under normal homeostatic conditions. At the same time, the entire cortex is replaced every few months [

1].

In the adult adrenal gland, various populations of cells are described that are located in the adrenal capsule and cortex, involved in maintaining homeostasis of the adrenal cortex [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. These capsule and cortical populations interact via reciprocal signaling networks, using mechanisms that are not well understood, coordinating centripetal proliferation and differentiation in response to paracrine and endocrine signals. However, we still do not have a clear understanding of how the niche of somatic stem cells in the adrenal cortex functions: the biological properties of these cells, their division rate, and migration ability are controlled, and thus the main regulators of the various stages of their differentiation remain unknown. For this reason, a reliable protocol for obtaining a cell model of the adrenal cortex through the differentiation of stem cells into long-lived and functional steroidogenic cells has not yet been developed. Studies describing the production of steroidogenic cells in vitro are based solely on the enhanced exogenous expression of steroidogenic factor 1, its homologues (liver receptor homolog-1) [

7,

8], and additional transcription factors such as WT1, CITED2, PBX1, DAX1 [

9]. In a number of works, the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway is activated in parallel through the addition of cAMP [

7,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Both pluripotent stem cells [

11,

12,

14,

15] and mesenchymal stem cells isolated from adipose [

16] and bone tissue [

10,

16,

17], umbilical cord blood [

11,

13], and even urine [

9] are used.

According to modern theories of carcinogenesis, cancer develops as a result of the accumulation of oncogenic mutations in the DNA molecule. The risk of DNA damage is particularly high during cell division and differentiation. Stem cells are the only cells that are able to preserve DNA from the zygote stage throughout the life of the organism and that are able to divide, self-renew, and differentiate throughout their existence. Both of these facts strongly suggest that in most cases the occurrence of cancer is associated with the oncotransformation of somatic stem cells into cancer stem cells [

18,

19]. As a consequence, organs with high regenerative potential, such as the intestine, respiratory tract, liver, and pancreas, have a high incidence of cancer [

20].

The transcription profile of cancer stem cells (CSCs) has much in common with the transcription profile of normal somatic stem cells; they share similar cellular characteristics, including surface markers and intercellular signaling pathways. As a consequence, CSCs show striking similarities with normal somatic stem cells in terms of long-term proliferation and an apoptosis inhibition program [

21]. Pathways involved in the self-renewal of normal somatic stem cells and the maintenance of stemness contribute to the proliferation and invasion of CSCs [

22]. According to the monophyletic origin model of cancer, the main biological feature that distinguishes CSCs from normal somatic stem cells may be that CSCs either differentiate into disordered cell types that do not restore the function of damaged tissues, or they do not differentiate at all into mature tissues [

23].

The presence of common critical signaling pathways explains why there is currently no publication on the successful creation of a relevant self-renewing cell model of adrenocortical cancer (ACC). Unlike, for example, other organs for which somatic stem cell niche signals have been identified and reproduced in vitro [

24,

25,

26,

27], recently, Baregamian reported creating 3-dimensional (3D) patient-derived organoid models of a spectrum of endocrine neoplasms, including ACC. However, in this study, the culture system was not validated by comparing the cellular and genetic heterogeneity of the obtained organoids with the original tumor, and it was not demonstrated that the ACC cell model proliferated stably for a long time [

28].

According to the evolution of the cancer stem cell model, only cancer stem cells have the ability to drive tumorigenesis, while other cancer cells exhibit features of normal tissue organization [

29]. Thus, due to the different functional properties of CSCs and cells that are not CSCs, there must be certain differences within a heterogeneous cancer population. To maintain the stemness property, specific signaling pathways and transcription programs must be active in CSCs, which means that characteristic markers must also exist.

Currently, various CSC markers have been characterized [

30,

31], many of which are multipotency markers [

32]. Some of the most well-characterized CSC markers are involved in signaling pathways that are crucial in the regulation of the somatic stem cell pool of organs; a striking example is the LGR5 receptor (

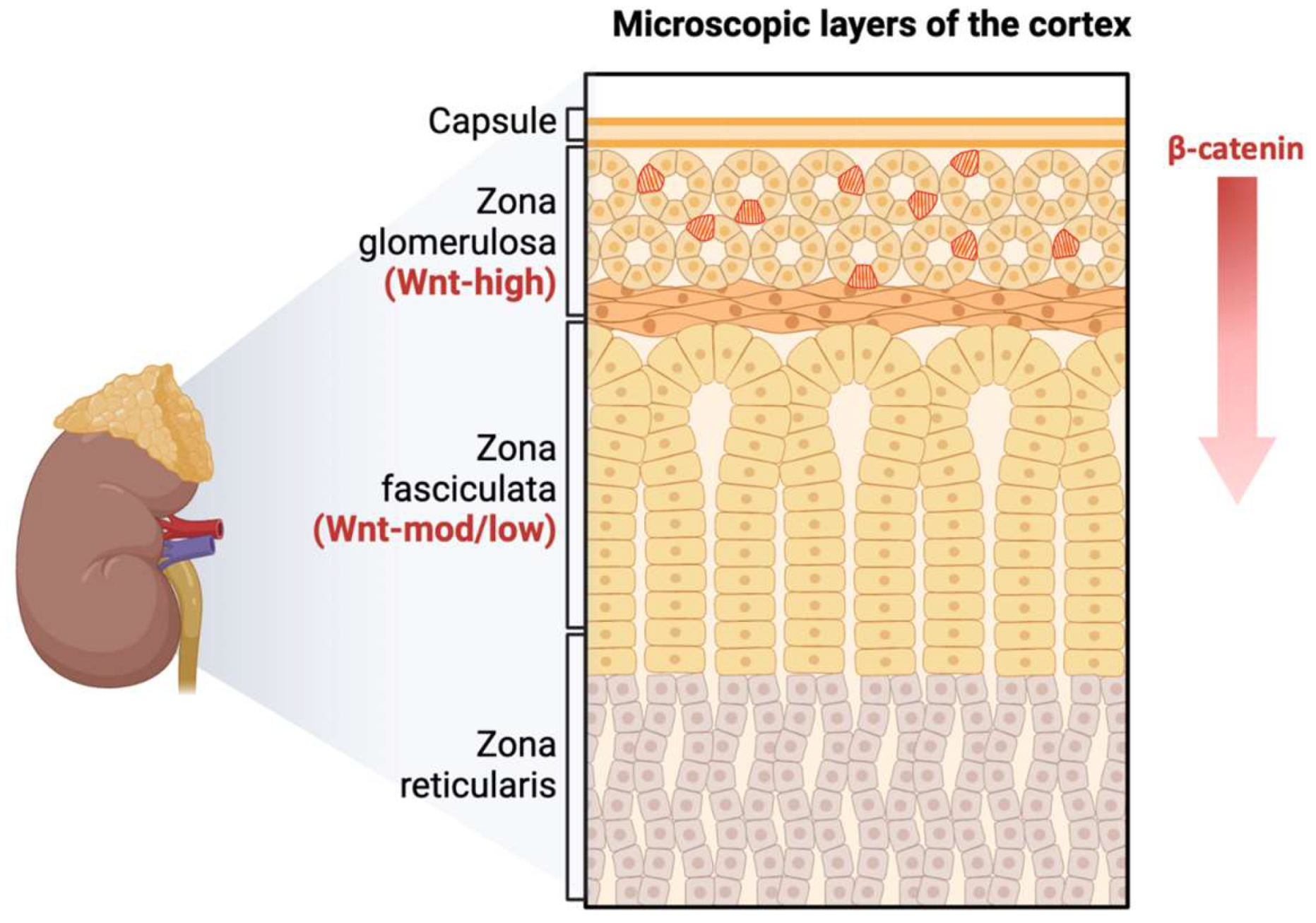

Figure 1). Vidal et al. demonstrated the canonical role of RSPO/LGR5 signaling in the ZG of the healthy adrenal cortex, which induces the well-known direct descending targets of β-catenin (AXIN2 and DAB2) and maintains the size of the organ in the adult body [

33]. In addition, a recent study from Al-Bedhawi showed that a few specific type cells within the capsule expressed a high level of CD90 [

34]. CD90, as a cell surface antigen, is considered one of the mesenchymal multipotent stem cell markers [

35].

In our study, we focused on the search for the aforementioned multipotency markers in various types of ACC to confirm their presence and localization. The obtained results suggested that there are not just one, but at least two populations of stem cells in the adrenal cortex, which are spatially separated and supported by different signaling systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Samples

The study included tumor tissue samples from patients with adrenocortical cancer who were treated at the Endocrinology Research Centre. All patients underwent adrenalectomy in the period from 2005 to 2023. Patients under the age of 18 at the time of surgery were excluded from the study. A total of 13 cases of adrenal tumors were selected for the study.

The study also included 2 samples of normal adrenal tissue obtained from surgical material from patients who underwent surgery for renal tumors. Tissue samples were taken at a distance from the tumor, and the presence of pathological formations in the material was completely ruled out.

2.2. Histological Imaging

Tumor tissue samples obtained during surgical treatment were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, processed in the histological wiring system of Leica ASP200, and embedded in paraffin. Further, paraffin sections with a thickness of 3 µm were made from the paraffin-embedded tumor tissue samples on the microtome, applied to slides treated with poly(L-lysine). Then, the slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin according to the standard procedure.

All tumor tissue samples were verified in accordance with the 2022 WHO classification of adrenal cortical tumors. The study included 3 cases of conventional subtype of adrenocortical cancer, 3 oncocytic, 3 myxoid, and 4 cases of mixed tumor (conventional and oncocytic subtypes).

2.3. Immunohistochemistry Imaging

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor tissue sections was carried out using a standard technique with a peroxidase detection system employing DAB on an automatic Leica BOND III IHC staining system. The antibodies used in this study were: anti-CD90 rabbit monoclonal antibody, ab133350 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); and anti-LGR5 rabbit polyclonal antibody, ab219107 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). All histological slides were scanned using a Leica Aperio AT2 system at 20x magnification for further analysis.

The counting of CD90-positive cells was performed in five fields of view each measuring 0.05 mm² (total area of 0.25 mm²) separated into areas for the tumor parenchyma and the subcapsular region. The most representative fields of view were selected. A semi-quantitative approach was used to assess LGR5 expression. Samples were scored on a scale from 0 to 3 in ascending order: 0 for negative samples or those with less than 10% stained tumor tissue; 1 for samples with 10 to 39% stained tumor tissue; 2 for samples with 40 to 79% stained tumor tissue; and 3 for tumors with 80% or more stained tumor tissue. Scores were determined independently by three pathologists. Clinicopathological information was concealed from the observers.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Python 3.9, utilizing libraries such as pandas, numpy, sklearn, scipy, and lifelines.

Descriptive statistics for quantitative features are presented as medians along with first and third quartiles, while qualitative features are reported in terms of absolute and relative frequencies. The comparison of three or more independent groups on a quantitative basis was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis criterion, followed by post-hoc analysis. Correlation analysis was conducted using Spearman's method.

Survival analysis was carried out using Kaplan-Meier analysis. A log-rank test was employed to compare the survival of two groups. Cox regression analysis was used to construct prognostic survival models. The critical level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. For multiple comparisons, the level of statistical significance was corrected using the Bonferroni correction.

3. Results

The study included 13 tumor samples from 13 patients with ACC, comprising 12 females with a median age of 54 years (Q1-Q3: 37-59) and one male patient aged 35 years. The clinical and morphological characteristics of the study group are presented in

Table 1.

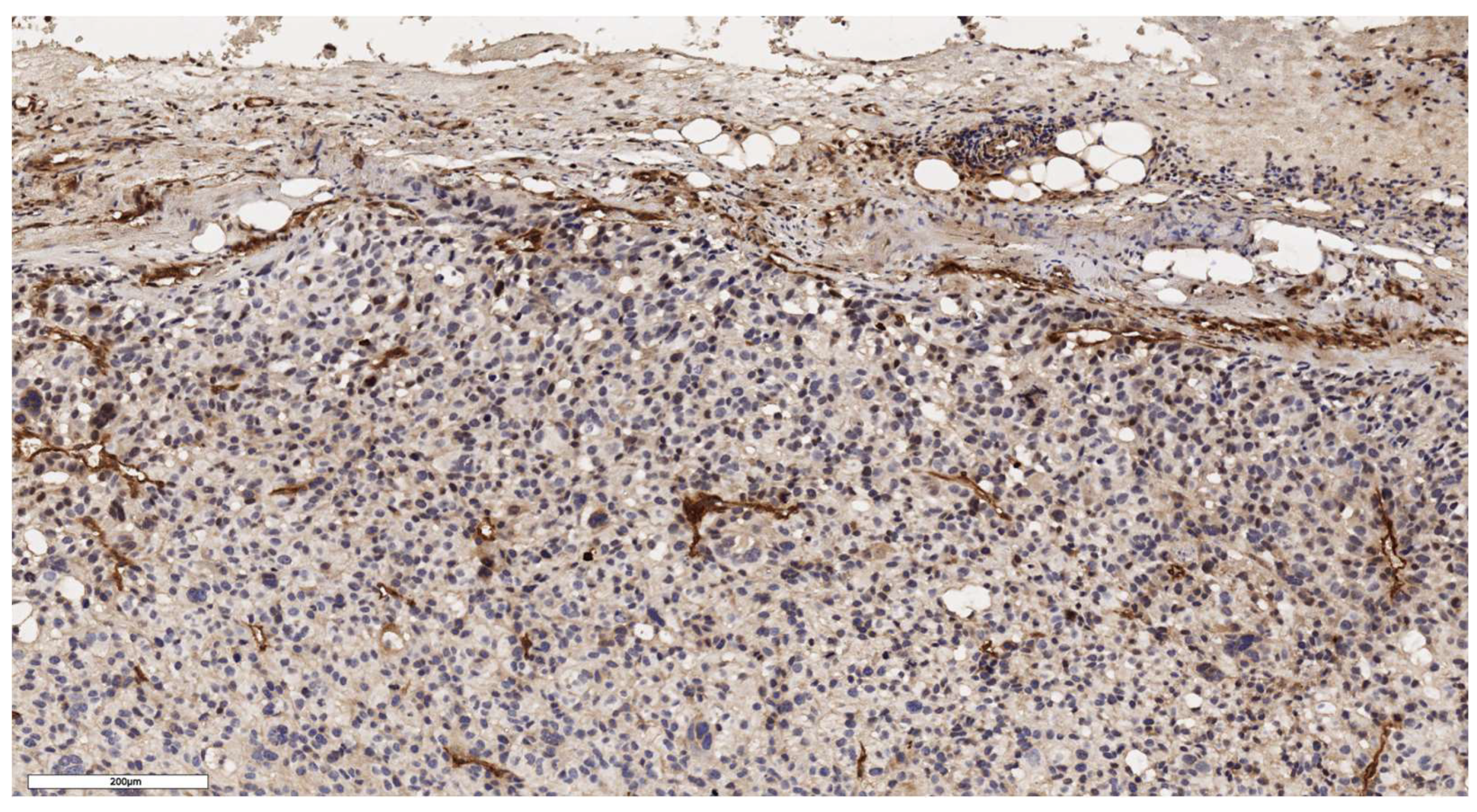

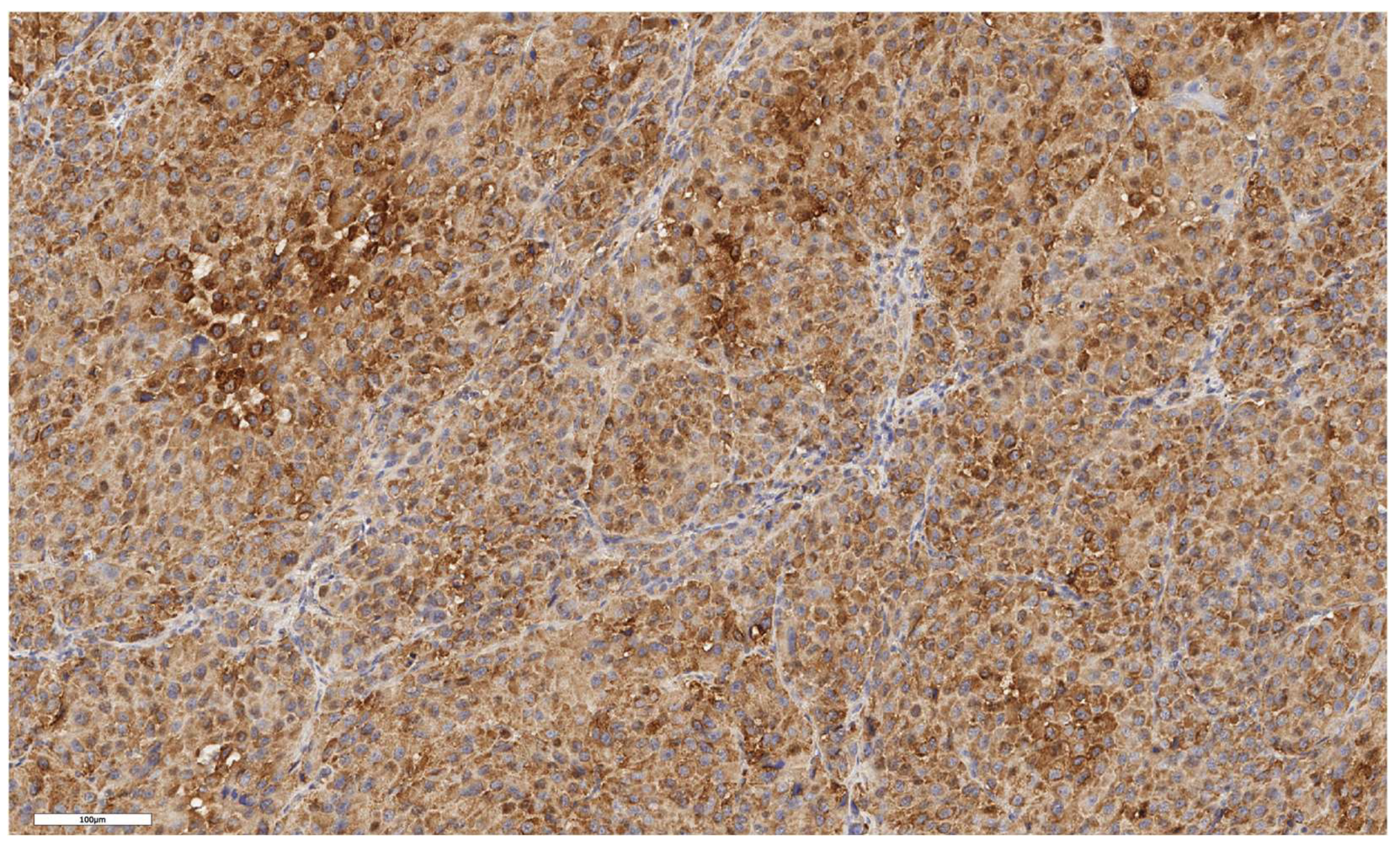

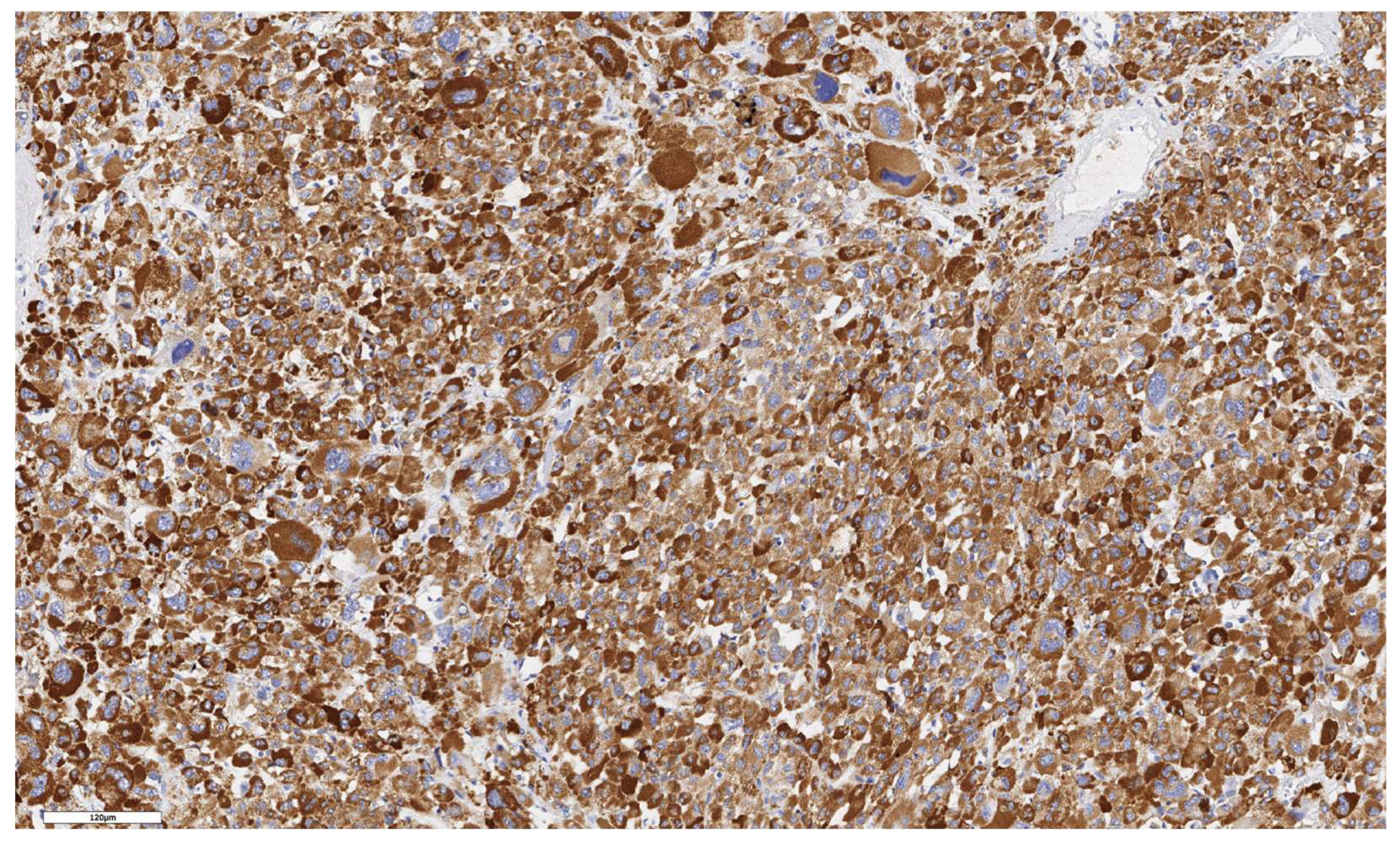

3.1. Analysis of CD90 Marker Expression

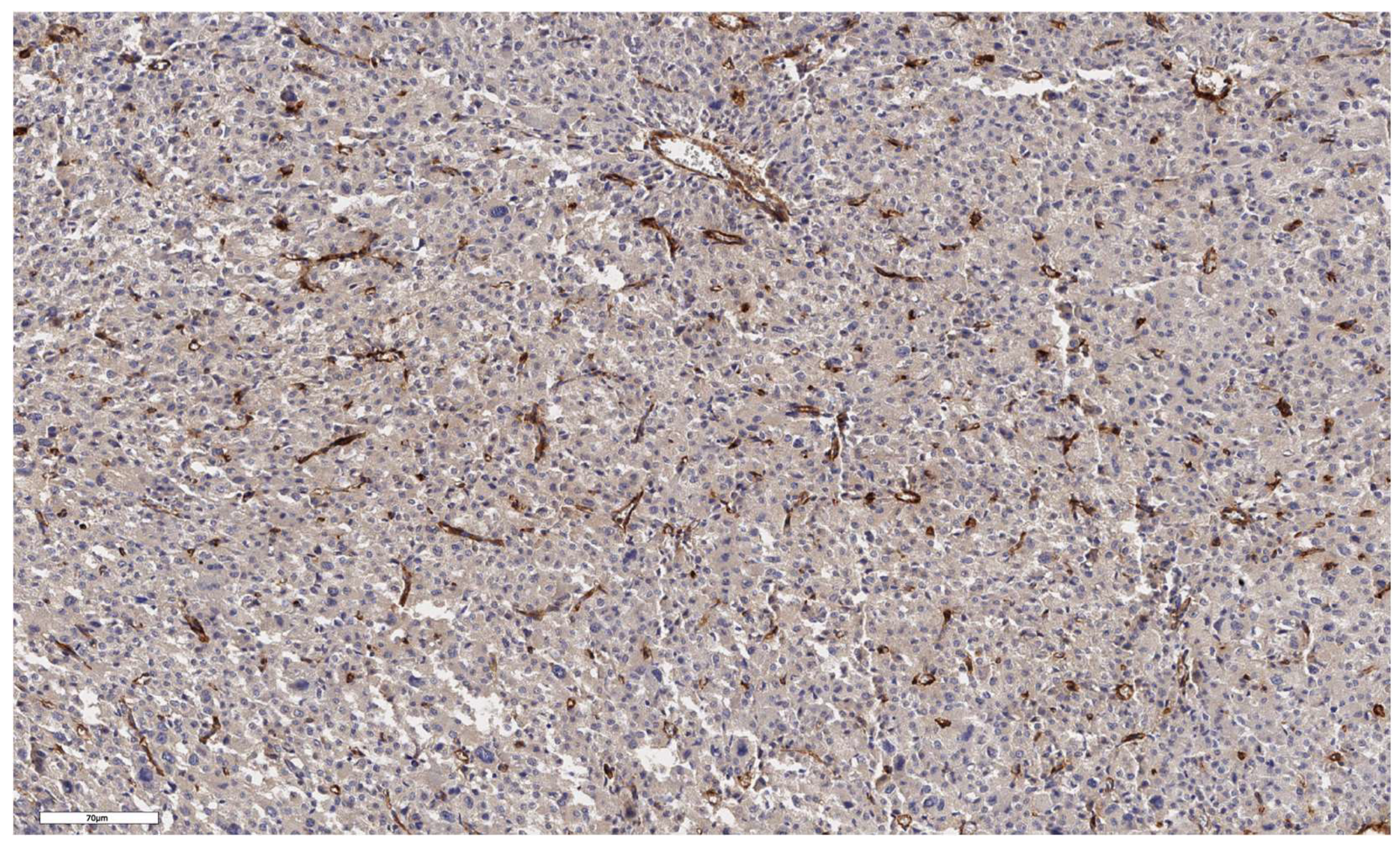

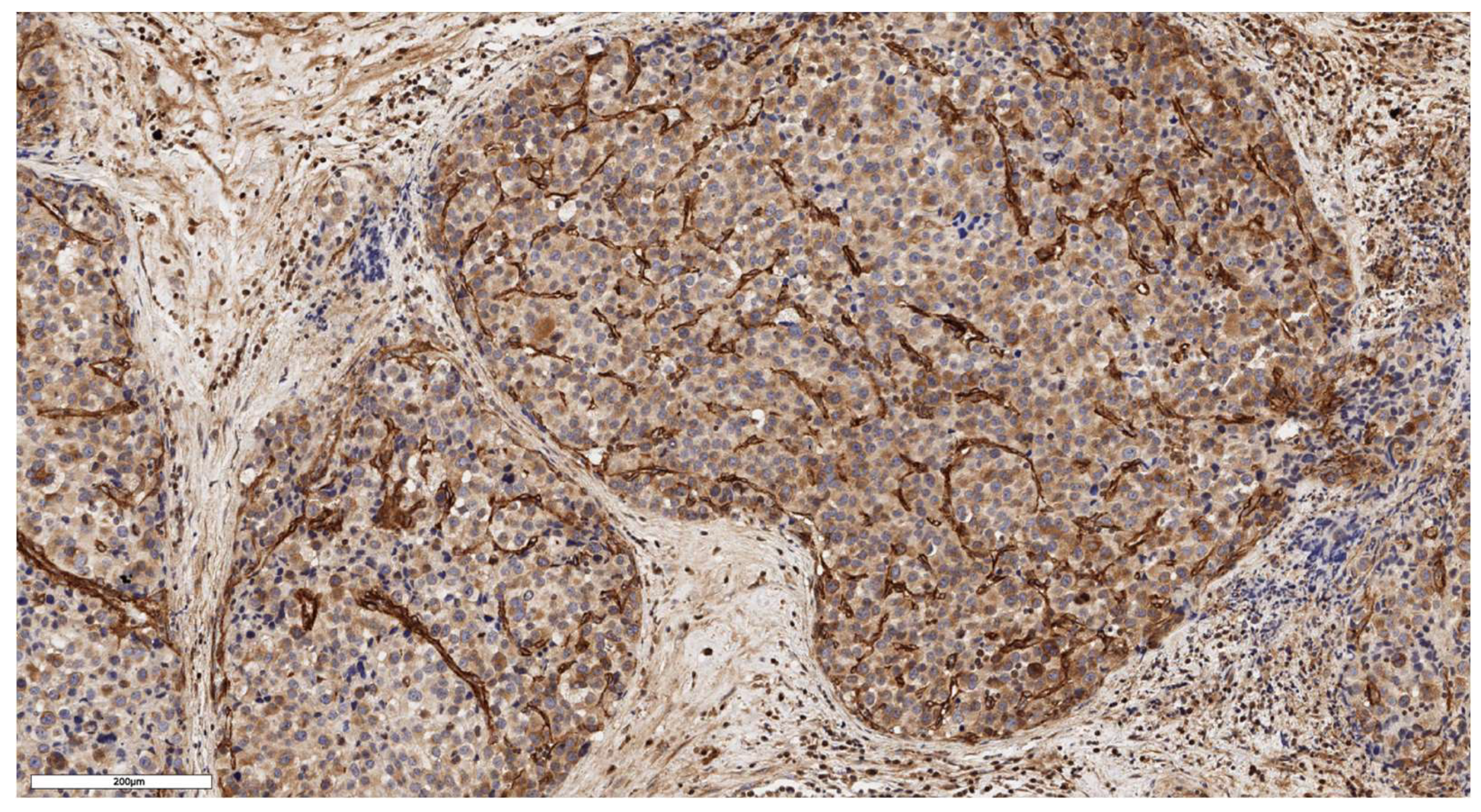

A positive immunohistochemical reaction with the CD90 marker was detected in all studied ACC samples. The number of CD90-positive cells under the capsule and in the tumor parenchyma was 26 (Q1-Q3: 10-91) and 28 (Q1-Q3: 13-207) cells/mm², respectively.

An analysis of the association between CD90 expression and the clinicopathological data of patients was conducted (

Table 2). The number of CD90+ cells in the tumor parenchyma was relatively higher in samples of conventional and mixed histological subtypes compared to other histological subtypes of ACC (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5); however, these differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.161). No significant differences in CD90 expression beneath the tumor capsule were found across histological subtypes either.

3.2. Analysis of LGR5 Marker Expression

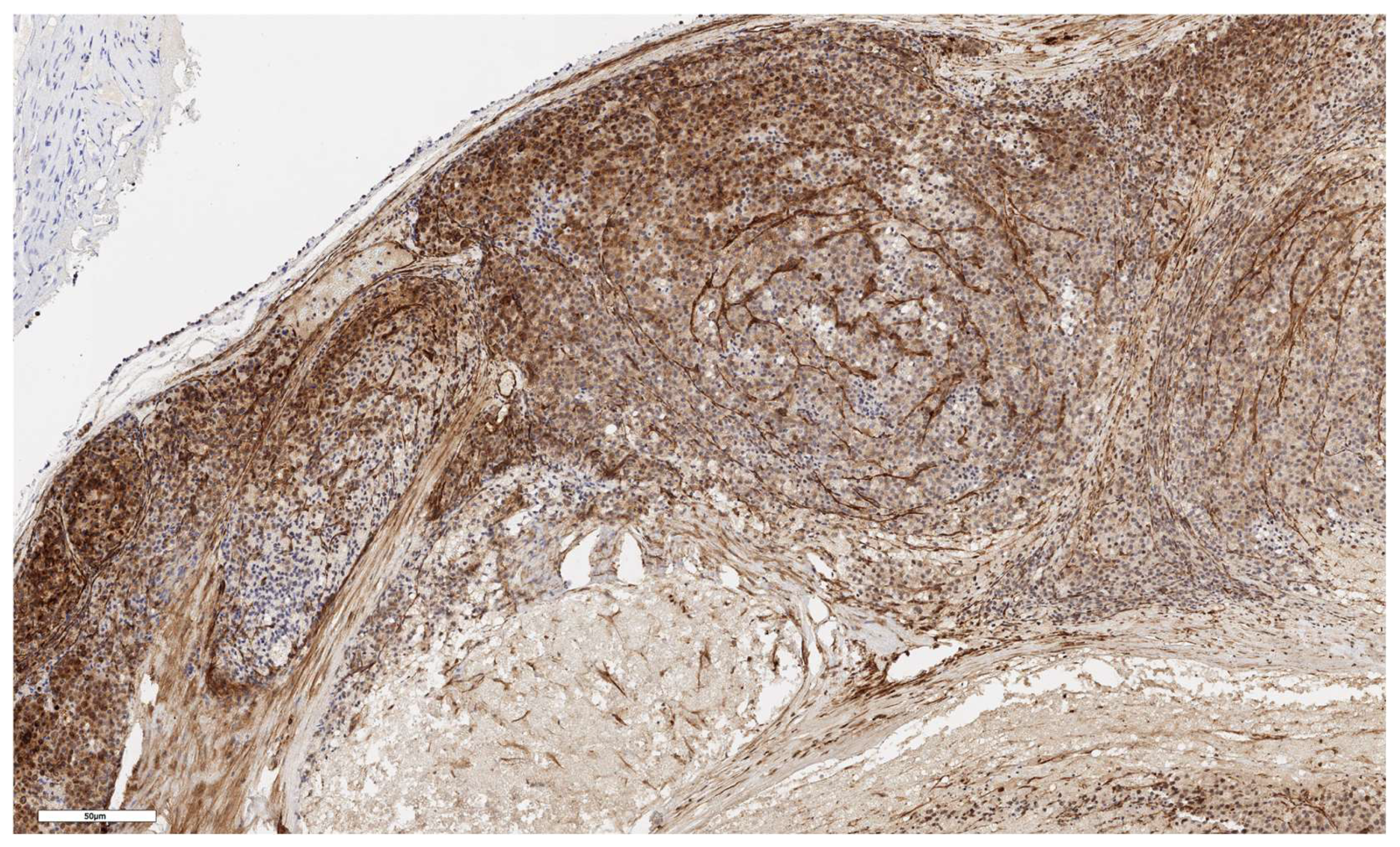

LGR5 expression scored as 1 was observed in 6 cases (46%), as 2 in 4 cases (31%), and as 3 in 3 cases (23%). In 8 cases (62%), LGR5 expression was focal, while in 5 cases (38%) it was diffuse (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). An analysis of LGR5 expression based on the histological subtype of ACC (

Table 3) revealed no significant differences (p = 0.199).

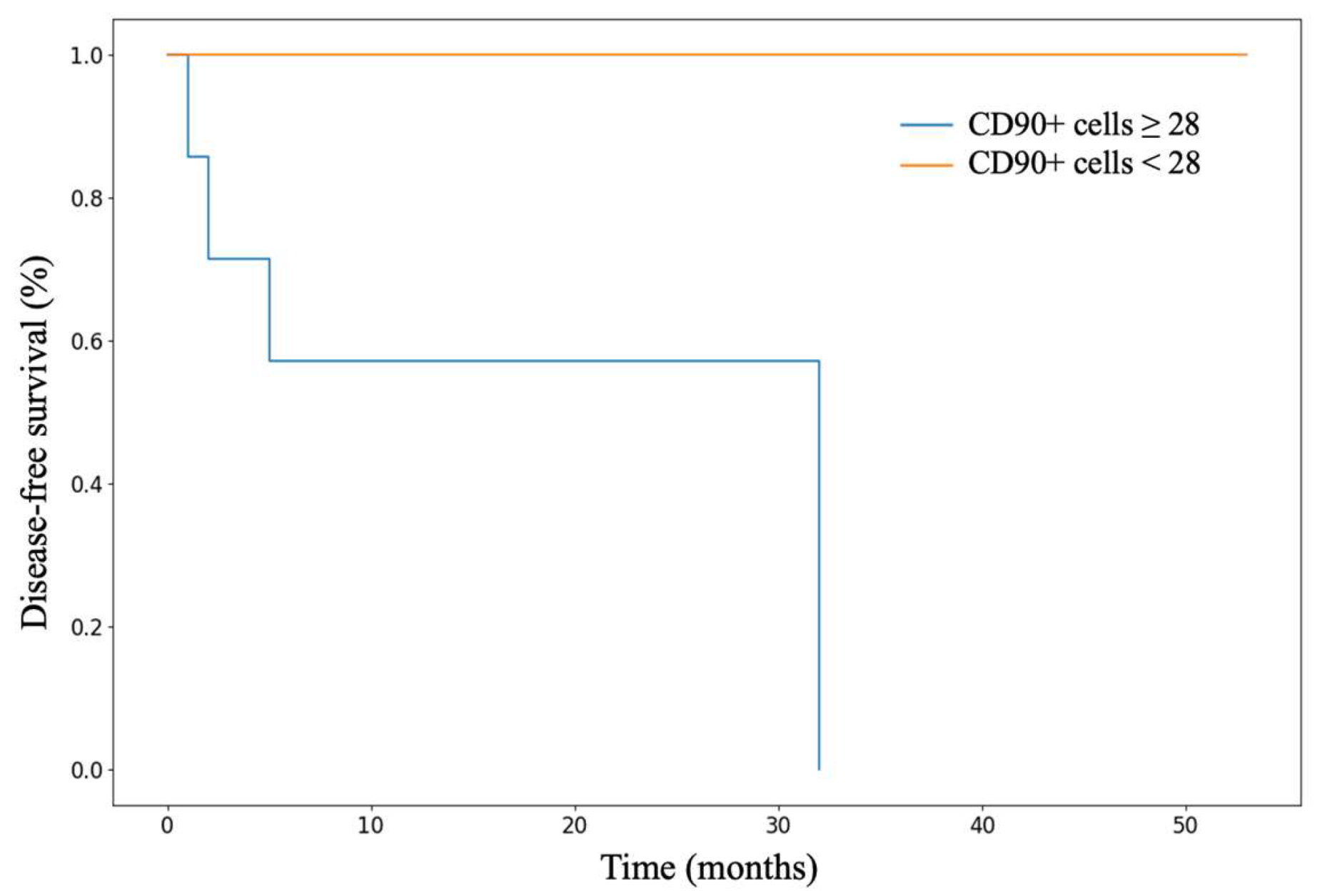

3.3. Analysis of Patient Survival Depending on the Expression of Stem Markers

We conducted an analysis of patient survival based on characteristics of stem marker expression. Statistically significant differences were found in the disease-free survival (DFS) rates of patients with ACC depending on the number of CD90+ cells in the tumor parenchyma (p = 0.042). Kaplan-Meier survival curves are presented in

Figure 8. Patients with a number of CD90+ cells below the median value demonstrated better DFS compared to those with a number above the median (p = 0.042).

3.4. Analysis of Stem Markers Expression in Normal Adrenal Tissue

In an immunohistochemical study of normal adrenal gland tissue using CD90 and LGR5 markers, a substantial number of cells stained positive. Notably, cells that stained positively for CD90 were located beneath the organ's capsule (

Figure 9); no positive cells were detected in other zones of the adrenal gland. Conversely, cells expressing LGR5 were predominantly found in the zona reticularis and beneath the organ's capsule (

Figure 10). This distinct localization suggests specific roles for these markers in different regions of the adrenal gland.

4. Discussion

ACC is a malignant neoplasm originating from cells of the adrenal cortex, with an incidence of 0.7-2 cases per 1 million population per year. Although radical tumor removal can potentially cure patients in some cases, the prognosis for a significant proportion remains unfavorable: the median overall survival (OS) is about 15 months. Currently, therapeutic options for these patients are extremely limited. The use of the adrenolytic drug mitotane, in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents, has not demonstrated a significant improvement in survival for most patients, and targeted immunotherapy is only effective in limited cases. The development of new, more effective, and safer methods of ACC treatment is now as relevant as ever.

Recent studies have demonstrated that CSCs contribute to the phenotypic heterogeneity of primary tumors, playing a crucial role in the initiation, growth, and metastasis of malignant neoplasms [

36]. Furthermore, CSCs are significant in promoting immune evasion, thereby diminishing the effectiveness of cancer treatments. One avenue for enhancing therapeutic efficacy in treating patients with ACC may involve a deeper understanding of the role of adrenocortical stem/progenitor cells in the pathogenic mechanisms of disease onset and progression. Although existing data indicate the presence of stem and progenitor characteristics in certain ACC cell populations, the challenge of identifying adrenocortical stem cell markers directly involved in the carcinogenesis of this disease remains unmet.

A number of markers have been proposed to identify and characterize subpopulations of cells with CSCs properties [

36]. It is important to recognize that currently, there is no universal, standardized marker for CSCs that is both highly sensitive and specific. Previous studies have shown that various mechanisms are involved in the development and maintenance of CSCs populations, and even within a single tumor, different types of CSCs with distinct marker expressions and properties can coexist. CD90 (also known as Thy-1) is a glycoprotein expressed on the surface of both tumor and immune cells. The phenotype of CD90-positive CSCs has been detailed in gastric cancer cell lines [

37]. In this study, it is demonstrated that CD90-positive cells are associated with high tumor cell proliferation through cell cycle progression in some gastric cancer cultures. The CD90 surface antigen is now considered one of the markers of mesenchymal multipotent stem cells.

Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5), also known as G-protein-coupled receptor 49 (GPR49), is a well-studied stem cell marker expressed in several organs, including the stomach, small intestine, colon, and liver [

38]. It has been reported that selective ablation of LGR5-positive CSCs leads to tumor regression, and exposure to colon LGR5-positive CSCs enhances the effect of chemotherapy [

39]. The presence and role of these markers in the adrenal gland have been previously described, but not investigated in ACC until now.

To our knowledge, this is the first time the presence and localization of the multipotent stem cell markers CD90 and LGR5 in different subtypes of ACC have been confirmed. In particular, unlike previous studies, we also detected the expression of the LGR5 marker in normal adrenal cortex tissue not only in the zona glomerulosa but also in the zona reticularis. Immunohistochemical expression of the studied markers was detected in all 13 cases. Moreover, even in such a small sample, statistically significant differences in disease-free survival (DFS) depending on the number of CD90-positive cells were found. This suggests a potential diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive value of these CSC markers and necessitates their analysis in a larger cohort of patients with ACC. Furthermore, the IHC study of samples from normal adrenal cortex tissue suggests that there are not one, but at least two populations of stem cells in the adrenal cortex, which are spatially separated and supported by different signaling systems.

Additionally, identification of stem cell subpopulations can contribute to the development of a cell model of the adrenal cortex, as well as a self-renewing cell model of ACC. The main common difficulty here is still the lack of a clear understanding of the critical signaling pathways involved in maintaining and differentiating stem cells. Studies on organs where somatic stem cell niches have been identified confirm that culture mediums effective for somatic stem cells [

40] also work with minor changes for cancer stem cells [

41]. Cells are provided with a culture medium consisting of a growth factor cocktail to trigger a regenerative response in the stem cells of the pertinent epithelium according to niche factor requirements. For example, key components for preparing human colon organoid culture medium include activators of Wnt signaling, ligands of tyrosine receptor kinases, and inhibitors of transforming growth factor-β/bone morphogenetic protein signaling such as Noggin [

27]. However, the possibility of niche-independent growth of stem cells, associated with the accumulation of multiple mutations, cannot be excluded [

42]. Genotype-phenotype analyses at a single-patient level could provide insights into adrenocortical tumorigenesis and patient-centered therapeutic development.

5. Conclusions

The results of this pilot study demonstrate the presence of LGR5- and CD90-positive tumor cells in ACC, confirming the importance of studying CSCs markers in both basic and clinical research. The identification and examination of CSC-specific markers in ACC offer a wide range of possibilities for targeted killing of these cell populations, potentially contributing to the cessation of tumor growth and prevention of disease recurrence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and L.U.; methodology, N.P. and A.F.; investigation, N.P., A.B. and L.U.; data curation, N.P. and A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, N.P., A.B. and E.P.; writing—review and editing, A.T., D.B., and L.U.; visualization, N.P.; supervision, E.K., R.I. and N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (agreement no. 075-15-2022-310).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Endocrinology Research Centre (protocol code 10, 26.05.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grabek, A.; Dolfi, B.; Klein, B.; Jian-Motamedi, F.; Chaboissier, M.C.; Schedl, A. The Adult Adrenal Cortex Undergoes Rapid Tissue Renewal in a Sex-Specific Manner. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 290–296.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariniello, K.; Ruiz-Babot, G.; McGaugh, E.C.; Nicholson, J.G.; Gualtieri, A.; Gaston-Massuet, C.; Nostro, M.C.; Guasti, L. Stem Cells, Self-Renewal, and Lineage Commitment in the Endocrine System. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, G.D.; Basham, K.J. Stem cell function and plasticity in the normal physiology of the adrenal cortex. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 2021, 519, 111043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyraki, R.; Schedl, A. Adrenal cortex renewal in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 2021, 17, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oikonomakos, I.; Weerasinghe Arachchige, L.C.; Schedl, A. Developmental mechanisms of adrenal cortex formation and their links with adult progenitor populations. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 2021, 524, 111172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatti, E.; Flück, C.E. Adrenal cortex development and related disorders leading to adrenal insufficiency. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 2021, 527, 111206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazawa, T.; Inanoka, Y.; Mizutani, T.; Kuribayashi, M.; Umezawa, A.; Miyamoto, K. Liver receptor homolog-1 regulates the transcription of steroidogenic enzymes and induces the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into steroidogenic cells. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3885–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, T.; Imamichi, Y.; Miyamoto, K.; Khan, M.R.; Uwada, J.; Umezawa, A.; Taniguchi, T. Regulation of steroidogenesis, development, and cell differentiation by steroidogenic factor-1 and liver receptor homolog-1. Zoolog. Sci 2015, 32, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Babot, G.; Balyura, M.; Hadjidemetriou, I.; Ajodha, S.J.; Taylor, D.R.; Ghataore, L.; Taylor, N.F.; Schubert, U.; Ziegler, C.G.; Storr, H.L.; et al. Modeling Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia and Testing Interventions for Adrenal Insufficiency Using Donor-Specific Reprogrammed Cells. Cell Rep 2018, 22, 1236–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, T.; Mizutani, T.; Yamada, K.; Kawata, H.; Sekiguchi, T.; Yoshino, M.; Kajitani, T.; Shou, Z.; Umezawa, A.; Miyamoto, K. Differentiation of adult stem cells derived from bone marrow stroma into Leydig or adrenocortical cells. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 4104–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazawa, T.; Inaoka, Y.; Okada, R.; Mizutani, T.; Yamazaki, Y.; Usami, Y.; Kuribayashi, M.; Orisaka, M.; Umezawa, A.; Miyamoto, K. PPAR-γ coactivator-1α regulates progesterone production in ovarian granulosa cells with SF-1 and LRH-1. Mol. Endocrinol 2010, 24, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonoyama, T.; Sone, M.; Honda, K.; Taura, D.; Kojima, K.; Inuzuka, M.; Kanamoto, N.; Tamura, N.; Nakao, K. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells and human induced pluripotent stem cells into steroid-producing cells. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4336–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Peng, G.; Zheng, S.; Wu, X. Differentiation of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells into steroidogenic cells in comparison to bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Prolif 2012, 45, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, U.; Jameson, J.L. Steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1)-driven differentiation of murine embryonic stem (ES) cells into a gonadal lineage. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 2870–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Y.; Sottas, C.; Culty, M.; Fan, J.; Hu, Y.; Cheung, G.; Chemes, H.E.; Papadopoulos, V. Directing differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells toward androgen-producing Leydig cells rather than adrenal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 23274–23283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondo, S.; Okabe, T.; Tanaka, T.; Morinaga, H.; Nomura, M.; Takayanagi, R.; Nawata, H.; Yanase, T. Adipose tissue-derived and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells develop into different lineage of steroidogenic cells by forced expression of steroidogenic factor 1. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 4717–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Gondo, S.; Okabe, T.; Ohe, K.; Shirohzu, H.; Morinaga, H.; Nomura, M.; Tani, K.; Takayanagi, R.; Nawata, H.; et al. Steroidogenic factor 1/adrenal 4 binding protein transforms human bone marrow mesenchymal cells into steroidogenic cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol 2007, 39, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H. The cancer stem cell: Premises, promises and challenges. Nat Med 2011, 17, 313–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lázaro, M. The stem cell division theory of cancer. Cell Cycle 2018, 123, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.F. Clinical and Therapeutic Implications of Cancer Stem Cells. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001, 414, 105–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Liu, P.; Yu, P.; Qin, T. Cancer Stem Cells are Actually Stem Cells with Disordered Differentiation: the Monophyletic Origin of Cancer. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2023, 19, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, P.; Sato, T.; Merlos-Suárez, A.; Barriga, F.M.; Iglesias, M.; Rossell, D.; Auer, H.; Gallardo, M.; Blasco, M.A.; Sancho, E.; et al. Isolation and in vitro expansion of human colonic stem cells. Nat Med 2011, 17, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drost, J.; Artegiani, B.; Clevers, H. The generation of organoids for studying Wnt signaling. Methods Mol Biol 2016, 1481, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, K.; Clevers, H. Organoids: Modeling Development and the Stem Cell Niche in a Dish. Dev Cell 2016, 38, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driehuis, E.; Kretzschmar, K.; Clevers, H. Establishment of patient-derived cancer organoids for drug-screening applications. Nat Protoc 2020, 15, 3380–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baregamian, N.; Sekhar, K.R.; Krystofiak, E.S.; Vinogradova, M.; Thomas, G.; Mannoh, E.; Solórzano, C.C.; Kiernan, C.M.; Mahadevan-Jansen, A.; Abumrad, N.; et al. Engineering functional 3-dimensional patient-derived endocrine organoids for broad multiplatform applications. Surg 2023, 173, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreso, A.; Dick, J.E. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walcher, L.; Kistenmacher, A.K.; Suo, H.; Kitte, R.; Dluczek, S.; Strauß, A.; Blaudszun, A.R.; Yevsa, T.; Fricke, S.; Kossatz-Boehlert, U. Cancer Stem Cells—Origins and Biomarkers: Perspectives for Targeted Personalized Therapies. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Stemness-Related Markers in Cancer. Cancer Transl Med 2017, 3, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Ji, X.; Zhang, F.; Li, L.; Ma, L. Embryonic Stem Cell Markers. Molecules 2012, 17, 6196–6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, V.; Sacco, S.; Rocha, A.S.; da Silva, F.; Panzolini, C.; Dumontet, T.; Doan, T.M.; Shan, J.; Rak-Raszewska, A.; Bird, T.; et al. The adrenal capsule is a signaling center controlling cell renewal and zonation through Rspo3. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-bedhawi, M. Identification and characterisation of a potential adrenocortical stem cell population. 2018.

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, Dj.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; Fang, Y.; Lyu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, L. Exploring the dynamic interplay between cancer stem cells and the tumor microenvironment: implications for novel therapeutic strategies. J Transl Med 2023, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Liu, H.; Pan, Y.; Sun, L.; Yu, L.; Sun, L.; Yang, Z.; Ran, Y. Distinct biological characterization of the CD44 and CD90 phenotypes of cancer stem cells in gastric cancer cell lines. Mol Cell Biochem 2019, 459, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Tan, S.H.; Barker, N. Recent Advances in Lgr5+ Stem Cell Research. Trends Cell Biol 2018, 28, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, Y.; Fujii, M.; Takahashi, S.; Takano, A.; Nanki, K.; Matano, M.; Hanyu, H.; Saito, M.; Shimokawa, M.; Nishikori, S. Cell-matrix interface regulates dormancy in human colon cancer stem cells. Nature 2022, 608, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Vries, R.G.; Snippert, H.J.; van de Wetering, M.; Barker, N.; Stange, D.E.; van Es, J.H.; Abo, A.; Kujala, P.; Peters, P.J.; et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 2009, 459, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Stange, D.E.; Ferrante, M.; Vries, R.G.; Van Es, J.H.; Van den Brink, S.; Van Houdt, W.J.; Pronk, A.; Van Gorp, J.; Siersema, P.D.; et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1762–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M.; Shimokawa, M.; Date, S.; Takano, A.; Matano, M.; Nanki, K.; Ohta, Y.; Toshimitsu, K.; Nakazato, Y.; Kawasaki, K.; et al. A Colorectal Tumor Organoid Library Demonstrates Progressive Loss of Niche Factor Requirements during Tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).