1. Introduction

In response to the urgent challenge of climate change, this paper presents an innovative approach to urban sustainability. The need for a more analytical perspective on urban sustainability is both relevant and essential. It is relevant because sustainability, in the context of the critical need to mitigate climate change, remains one of the most pressing issues in modern urban development [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Moreover, it is essential, as both sustainability and urban environments are inherently complex systems. Their formal definition, let alone quantification, has proven difficult with the conventional tools and methods applied thus far [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

To address these challenges, this paper introduces a semantic-network framework that integrates smart technologies and sustainable planning into a unified model for urban transformation. By leveraging digital advancements and sustainability principles, this framework supports emerging planning models that are reshaping city ecosystems in the context of the digital and green transitions. These twin transitions represent the foundation for cities moving toward climate neutrality and net-zero carbon emissions, aligning with both local and global sustainability goals.

The semantic approach to urban sustainability proposed in this paper leverages the capabilities of the Semantic Web and graph theory, offering several advantages that make it ideal for managing the complexities of modern cities. It provides a structured framework for handling Big Data, establishing a common language for both humans and computers [

18,

19]. This enables diverse data types to be processed and understood across different domains, allowing for seamless collaboration between stakeholders using varying terminologies and technologies [

20,

21]. Additionally, semantic technologies are highly adaptable, facilitating the alignment of heterogeneous datasets [

21,

22,

23] and managing the complex relationships inherent in urban systems [

20,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. As cities undergo green and digital transitions, this adaptability is key to supporting real-time decision-making processes and smart-green city metrics [

1,

3].

Building on these strengths, this paper adopts a localized ontology approach to urban sustainability, based on Greek urban planning terminology and categorization to describe urban objects and their relationships. There are two key reasons for this choice. First, by concentrating on a specific and well-defined urban planning framework, we can more easily test and validate the new methodology. Second, while broad city planning ontologies provide valuable frameworks for urban planning and sustainability, they often lack the tailored specificity required to incorporate local regulatory nuances [

27,

28]. This focus on a city ecosystem model enables greater precision and relevance when addressing local planning regulations and sustainability concerns.

This paper makes several important contributions to the field. First, we develop an ontology that semantically describes urban space based on Greek urban planning terminology and categorization, integrating sustainability aspects. This approach offers a context-sensitive representation of local planning while incorporating sustainability parameters [

19]. Second, we demonstrate how to populate this ontology using open geospatial data, making it an accessible and practical tool for urban sustainability assessment, even in cases where data are scarce or unavailable [

29]. Third, we propose a methodology that explores the utilization of graph theory to build sustainability indicators and integrate them into the ontology. While this paper does not yet create these indicators, it sets the stage for their future development by establishing a new semantic and network-theoretic framework for urban sustainability analysis. The framework begins with a tailored ontology that can be easily populated with OpenStreetMap (OSM) data and outlines a way to enhance it with network analysis metadata, providing a clear path for future exploration.

2. State of the Art in Urban Sustainability and Semantics

2.1. Sustainability

The term sustainability is widely used in various fields. It implies a balance between environmental, social, and economic considerations. It is a manifestation of responsibility towards meeting present generations’ needs, without sacrificing the ability or capacity that future generations have to meet their own. However, a key challenge is the lack of standardized metrics for measuring and understanding sustainability.

As a critical issue in urban development, sustainability is complex and dynamic, with diverse perspectives in literature. Costanza and Patten [

4] highlight the difficulty in defining and predicting sustainability due to its inherent complexity. Heinberg and Lerch [

5] explore its implications amid global challenges. Thiele [

30] highlights the role of creativity alongside conservation, and Farley and Smith [

6] question whether the broad scope of sustainability risks diluting its meaning. Giovannoni and Fabietti [

31] further discuss the challenges in defining sustainability, reviewing its multifaceted nature and applications across various contexts.

The literature shows a lack of consensus on sustainability values and urban layouts. Metrics for sustainability are influenced by ecological resilience, social equity, and economic viability, making it difficult to quantify and compare. Bibri and Krogstie [

3] discuss the interdisciplinarity of smart sustainable cities, exploring the role of digital transitions alongside green transitions in shaping future city models, while Bai et al. [

1] propose a systems approach emphasizing the interconnected nature of urban systems. Sodiq et al. [

7] highlight the need to renew urban spaces based on current sustainability trends, emphasizing the ongoing urban transformation and green transition processes. Girardet [

8] emphasizes the integration of ecological, social, and economic systems in achieving urban sustainability, reinforcing the need for comprehensive approaches to city ecosystems and planning models.

This research addresses this gap by exploring new standards and indices for assessing sustainability, recognizing that subjective evaluations are insufficient. The aim is to establish a concrete foundation for measuring and comparing urban sustainability.

Urban sustainability connects ecological, social, and economic systems, necessitating tools to navigate this complexity. This research discusses the use of Semantic Web technologies and graph theory to provide a comprehensive outlook on urban sustainability and develop an interdisciplinary language.

The following chapters will investigate these computational tools and their potential to create new sustainability metrics, aiming to provide measurable parameters and establish a common language across disciplines. The ensuing chapters will explore the methodology, case studies, and results to demonstrate how these tools are analytically robust and capable of providing an integrated comprehension of urban sustainability.

2.2. The Semantic Web

The Semantic Web represents a paradigm shift in the development of the World Wide Web, advancing it from a network of unstructured and loosely linked resources to a more organized, semantically rich, and interoperable data space, as envisioned by Tim Berners-Lee in his foundational work on transforming the Web into a 'web of data' with well-defined relationships and meaning [

32].

Transitioning from Web 1.0 to Web 3.0, the Semantic Web involves dynamic and smart processing of information. Antoniou and Van Harmelen [

22] discuss its historical development, highlighting the addition of metadata, ontologies, and standardized formats to create a structured digital ecosystem. A key aspect of the Semantic Web is data interoperability, enabling seamless linking and transfer of data across different platforms to create a universal data space. Becker and Bizer [

33] show how linked data principles enhance information accessibility and relevance, while Andročec et al. [

34] highlight the role of Semantic Web technologies in ensuring compatibility within the Internet of Things (IoT) landscape. Heath and Bizer [

35] describe how linked data principles have evolved the web into a global data space, providing a framework for organizing and connecting data through well-defined relationships.

Semantic Web tools, including ontologies and knowledge graphs, are widely adopted across a range of fields, demonstrating their effectiveness in handling complexity. In medicine, for instance, they are used to develop semantically enriched learning environments, support mixed reality educational experiences, and improve knowledge retrieval processes [

36,

37,

38]. These tools are also central to law and forensic science, where they enhance crime scene analysis through forensic ontologies and assist in the semantic representation of complex legal concepts, such as the intersection between criminal law and civil tort [

39,

40]. In the sports domain, Semantic Web technologies are employed to facilitate the multidimensional classification and analysis of sports data [

41]. Broadly, they play a critical role in data alignment and ontology matching, which ensures semantic consistency across diverse knowledge systems [

42].

Additionally, Semantic Web technologies have been utilized in internationalized linked data projects, such as the Greek DBpedia, showcasing their scalability for multilingual data interoperability [

43,

44]. They also extend to specialized areas like mathematics, where they assist in linking and organizing complex subject classifications [

45]. In national strategic frameworks, these tools help mine and analyze large datasets, identifying red flags and trends [

46].

This wide array of applications underscores the Semantic Web’s capacity to handle intricate datasets and complex systems across various fields, making it an essential tool for interdisciplinary research and problem-solving.

2.3. Ontologies: Definition, Importance, and Applications in Smart Cities

Ontologies, formal representations of knowledge within a specific domain, provide a structured framework to understand concepts, like objects, properties, or relations. Noy and McGuinness [

47] claim ontologies enhance understanding and communication by organizing knowledge. Although it is a concept rooted in philosophical inquiries into existence and reality [

48], in computer science, it has become a crucial tool for semantic interoperability and knowledge management across various domains [

18,

25,

34,

48,

49].

In smart cities, ontologies play a vital role in building common understanding and enhancing interoperability among disparate systems. Komninos et al. [

24] highlight their use in creating shared vocabularies and facilitating communication among stakeholders. Recent advancements in smart city ontologies have improved dynamic reasoning and data integration, addressing urban sustainability complexities [

14,

16,

49]. Additionally, ongoing research highlights the role of ontologies in refining urban planning processes and fostering sustainable development within smart cities [

18,

47].

City-related ontologies can be divided into those exclusively focused on the city and those including the city as a class, such as the DBpedia ontology. While many ontologies provide various perspectives on cities, none fully address the spatial definition from an urban planning viewpoint. For instance, the Smart City Ontology 2.0 covers various urban aspects but lacks comprehensive spatial considerations [

14,

16,

50]. This paper aims to bridge this gap by exploring the city from a spatial perspective grounded in urban planning principles. The ultimate goal is to combine all ontologies that describe specific aspects of a city into a unified ontology, encompassing all perspectives.

Ontologies also have significant applications in architecture, where they facilitate a holistic understanding of structures and drive innovation in design. Chieh-Jen Lin [

51] introduces semantic topology in architecture, demonstrating how ontologies can transform architectural design and analysis. Recent studies further explore the integration of architectural and urban data through semantic topology, enhancing design processes [

50,

52]. Lin's studies showcase the transformative potential of Semantic Web technologies, that can empower algorithmic design by providing structured data, redefining creative boundaries in architectural design [

15,

52,

53].

Semantic Web ontologies offer transformative potential in architecture by improving data understanding and performance evaluation. Research by Panagoulia and Lancaster [

23] delves into the intersection of Semantic Web ontologies and building performance data, offering insights into structuring and interpreting information for a comprehensive understanding of building functionality [

50]. Lin's work on semantic-topological-geometric information conversion illustrates how ontologies can enhance Building Information Modeling (BIM), paving the way for more meaningful digital models and the future trajectory of urban design [

16,

50,

52].

2.4. Ontologies and the Semantic Web for Urban Sustainability

Urban sustainability presents a complex challenge that necessitates advanced tools for analysis and decision-making. Ontologies and the Semantic Web offer promising solutions by providing structured frameworks that enhance data integration and interoperability across different domains. However, there are still significant gaps, particularly in the integration of urban planning aspects with sustainability considerations [

14,

15,

24].

Existing ontologies often focus on specific domains of urban sustainability, such as environmental, social, or economic aspects, without fully capturing the intricate interconnections required for comprehensive urban planning. For instance, the CityGML standard models 3D urban environments but lacks detailed urban planning and sustainability elements [

50,

54]. Similarly, GIS-based ontologies provide spatial analysis tools but fail to fully integrate urban planning complexities [

14,

20].

While broader frameworks attempt to bridge these gaps by linking urban planning and sustainability elements through knowledge graphs, challenges remain in adapting these approaches to local regulatory contexts and specific urban dynamics. To address these shortcomings, an integrated approach combining CityGML, GIS-based ontologies, and sustainability-focused models is needed. Such an approach, along with more localized ontologies, can better support urban analysts and planners by offering more robust tools for tackling urban sustainability challenges.

This paper introduces an ontology that integrates urban planning with sustainability factors, leveraging the capabilities of semantics and network theory. By focusing on a localized approach rooted in Greek urban planning terminology, this ontology offers greater specificity and adaptability to local contexts, addressing regulatory nuances often overlooked in broader city planning ontologies. While still a small part of a comprehensive urban sustainability framework, it demonstrates the potential of a semantic approach in organizing, categorizing, and analyzing urban data. Additionally, it highlights how network theory can be applied to enhance the interconnectedness of urban elements, further supporting the integration of sustainability and urban planning.

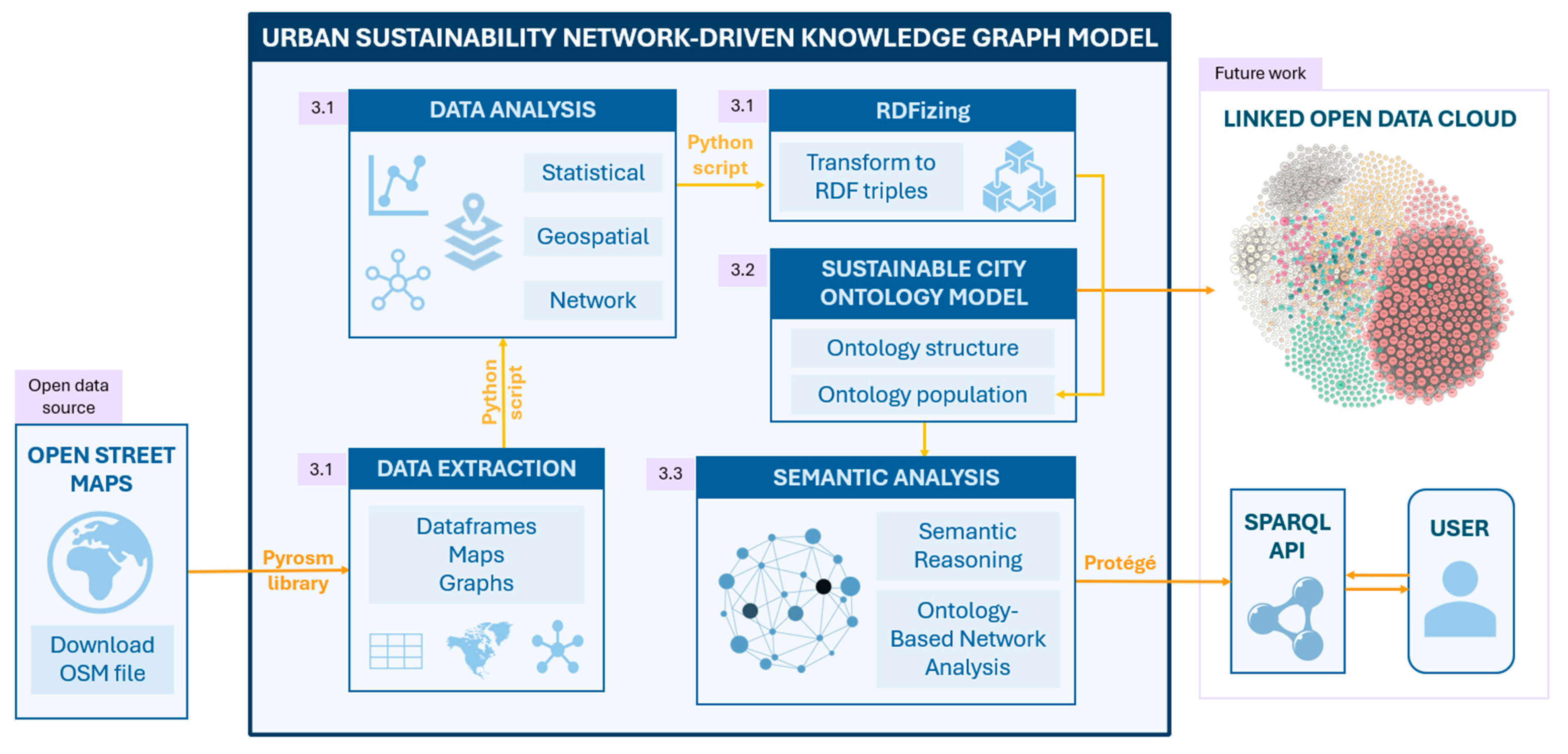

3. The Proposed Approach Towards Measuring Sustainability: Assessment and Analysis Tools

This research explores innovative approaches to assess and quantify urban sustainability by integrating the Semantic Web and graph theory. The goal is to lay the groundwork for a unified sustainability index, aligning with the ongoing digital and green transitions shaping urban transformation.

The study presents a methodology to develop and evaluate indices that could contribute to a unified sustainability index. While creating such an index requires further research, this paper takes the first step by developing a framework and tools designed for this purpose. The analysis focuses on key urban features linked to sustainability, such as green spaces, proximity, connectivity, and accessibility. Although there is no consensus on the exact values correlated with sustainability, this study identifies potential indicators through an exploratory approach, acknowledging the trial-and-error nature of this task.

When fully realized, the proposed methodology aims to provide urban planners and policymakers with a systematic framework to create, assess, and validate sustainability indicators, set goals, design strategies, and monitor progress. This research represents the initial step in demonstrating the potential of this approach to support city transformation and assist cities in their journey towards becoming smart and climate-neutral by leveraging the twin digital and green transitions.

This chapter presents the framework for the proposed approach, illustrated through a comprehensive diagram in

Figure 1. The diagram outlines the workflow and individual components that form the backbone of the proposed methodology. In the following sections, each component will be thoroughly examined, providing detailed explanations, examples, and case studies to demonstrate their functionality and applicability. The right side of the diagram shows features that are identified as potential areas for future development, which will be further explored in the conclusions chapter.

3.1. Data Preparation and Potential Tools of Analysis

3.1.1. Data Extraction

At this stage of the research, the primary focus is on the efficient extraction, conversion, and analysis of data from OpenStreetMap (OSM) files. The workflow enables data to be structured into various formats such as dataframes, graphs, or RDF triples, facilitating a comprehensive analysis of the urban landscape. By leveraging appropriate tools, the study ensures streamlined data processing and transformation, allowing for deeper insights into urban features and relationships.

In a case study using Thessaloniki's center, a Python script was developed to generate dataframes from OSM data, including streets, buildings, land uses, and natural elements. These dataframes allow for easy categorization, measurement, and extraction of data for further analysis.

Figure 2.

The part of Thessaloniki Center that was used as a case study.

Figure 2.

The part of Thessaloniki Center that was used as a case study.

Figure 3.

Example of a dataframe extracted from an OSM file containing street network data in a part of Thessaloniki’s center.

Figure 3.

Example of a dataframe extracted from an OSM file containing street network data in a part of Thessaloniki’s center.

Additionally, OSM data can be converted into geospatial representations, creating maps that visually illustrate various data dimensions providing a detailed and interconnected perspective of the urban environment.

Figure 4.

Example of a plot representing the buildings in the same area with colors denoting different building types.

Figure 4.

Example of a plot representing the buildings in the same area with colors denoting different building types.

3.1.2. Data Analysis

Converting OSM files into dataframes and maps provides a better understanding of the data. Integrating raw data into tables with geometric and morphological information from georeferenced representations forms a detailed and interconnected perspective. This integration, embedded in 3D, real-space coordinates, ensures data accessibility and navigability. The dataframes allow for dynamic exploration, enabling swift identification of specific information, while spatial maps facilitate immediate recognition and preliminary insights, guiding subsequent in-depth analysis. The data can be subjected to various forms of analysis, including statistical analysis to identify patterns or trends, spatial analysis to examine geographic relationships and distributions, and network analysis to explore connectivity and interactions within urban structures. This multifaceted approach enriches the exploration process, contributing to a more nuanced and comprehensive.

Custom filters further enhance analysis by calculating additional information, such as areas not initially present in the data. For example, a script was created to calculate and add area measurements to the dataframes, demonstrating the adaptability of the approach to specific analytical needs.

Network Analysis

The flexibility of working with OSM data allows for the creation of diverse graphs, offering a deeper analysis of urban structures compared to traditional tabular data or visual maps. For example, using tools like the Pyrosm package, street networks can be filtered, and nodes (intersections) and edges (road segments) extracted to form graphs. These graphs can then be further analyzed applying graph theory concepts to enhance urban network analysis. This approach is grounded in graph theory principles [

55,

56] and have been advanced by numerous studies on urban networks [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62].

This allows for a more nuanced analysis of urban sustainability. The intricate relationships within urban networks, as revealed through these graph-theoretical approaches, underscore the importance of further investigation to refine these tools and fully realize their potential for urban planning and sustainability.

Figure 5.

Example of a graph of the street network of a part of Thessaloniki's center where nodes represent intersections, and edges signify road segments.

Figure 5.

Example of a graph of the street network of a part of Thessaloniki's center where nodes represent intersections, and edges signify road segments.

3.1.3. RDFizing Data and Metadata

Once the raw OSM data has been extracted and transformed into dataframes and geospatial maps, the next step involves converting this structured data into RDF triples. RDF (Resource Description Framework) is a data model that enables the representation of information about resources in the form of subject-predicate-object triples. The transformation of dataframes into RDF triples ensures that the data is machine-readable and semantically enriched.

Each urban element—whether a street, park, building, or natural feature—is represented as an RDF triple, encoding its properties and relationships. For example, a street might be transformed into an RDF subject, with its attributes (such as name, width, and length) forming the predicates and their values as the objects. This process ensures that the urban data is properly categorized and can later be integrated into a larger semantic framework for further analysis.

By RDFizing both the data and associated metadata, the system ensures that the information is not only structured but also interoperable and ready for integration into semantic platforms or ontologies in future stages of the project.

3.2. Sustainable City Ontology Model

3.2.1. Ontology Structure

SKOS Concept Scheme

The Sustainable City ontology is essentially a dictionary of urban planning terms, making a SKOS schema ideal for its representation. The Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) is a standard data model that facilitates sharing and communication in knowledge management systems, particularly on the web. SKOS captures and organizes commonalities in dictionaries and classifications, promoting data sharing across various applications. It can be used alone or with formal knowledge representation languages like OWL. SKOS allows concepts to be identified by URIs, labeled in multiple languages, assigned notations, documented with notes, connected to other concepts, organized into hierarchies, grouped into collections, and mapped to other schemes [

63].

A SKOS scheme for the city is created, with an urban planning dictionary describing the hierarchy of terms within the CITY Concept Scheme. This includes concepts related hierarchically (e.g., broader, narrower) or semantically (e.g., exact match). The semantic connections between concepts allow for mapping the degree of similarity or interchangeability between terms. This is crucial, since finding exact synonyms across languages is challenging due to differences in connotation, frequency, and context [

64].

Figure 6.

The SUBCITY concept scheme.

Figure 6.

The SUBCITY concept scheme.

For example, "square" and "plaza" in urban planning may be considered synonymous but have historical and functional differences. A plaza, often seen as the Span-ish equivalent of a square, typically refers to public spaces with well-defined sides and is historically linked to commercial functions, while squares are associated with cultural and historical functions. These distinctions, although less relevant today, should be reflected in an urban planning dictionary, which SKOS concepts can accommodate.

Figure 7.

The CITY concept.

Figure 7.

The CITY concept.

Classes

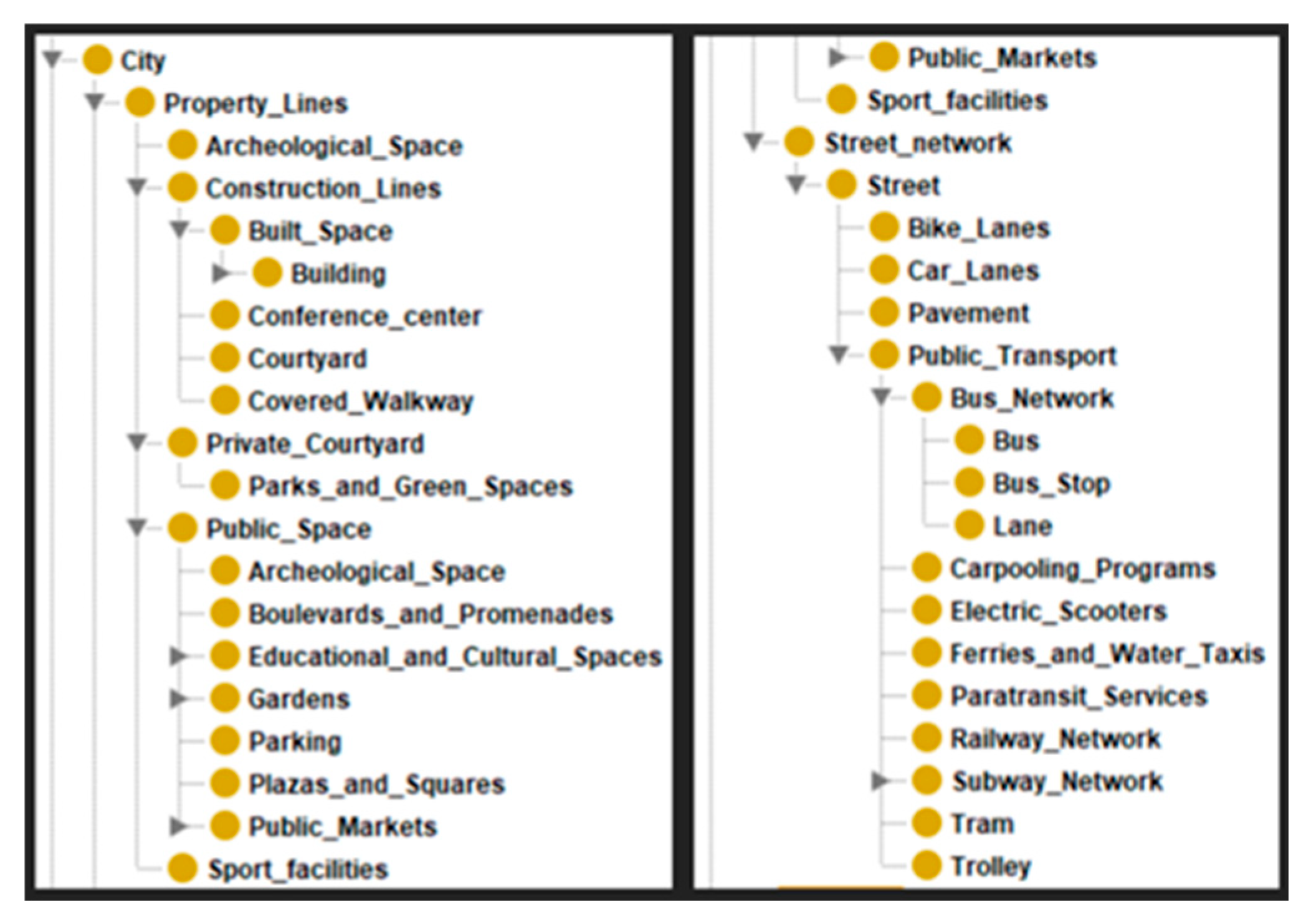

Equivalent OWL classes have been created for each SKOS concept to utilize both of their capabilities. While SKOS handles the taxonomy of urban planning terms, OWL manages more complex relationships between classes. Each SKOS concept is linked to an equivalent OWL class via IRIs, enabling the transfer of properties between them.

The ontology’s class hierarchy is based on urban planning, mirroring the SKOS scheme. More specifically, the terms used on this otology are based on Greek urban planning rules from e-poleodomia [

65]. The two main classes are

PropertyLine and

StreetNetwork, reflecting urban planning principles where road networks surround property lines, which contain built spaces and public areas. Subcategories of these main classes are:

ConstructionLine, a subclass of

PropertyLine, represents built spaces, while

PublicSpace includes subclasses like Park, Square, and Parking. Similarly,

StreetNetwork includes the Street class, which is further divided into

BikeLane, CarLane, Pavement,

PublicTransport, etc.

Additional classes related to activities (e.g., Culture, Education, Sport) and space types (e.g., circulation, greenery, resting areas) are associated with the main classes, which are particularly useful for examining urban sustainability.

These classes provide a structured foundation for a comprehensive and adaptable city ontology. For instance, sustainability-focused classes are included here, but if the research shifts to climate change, environmental factors such as gas emissions and sensor data can be easily integrated. This ontology can also be linked with other sustainability ontologies, enhancing its capacity to monitor and analyze environmental impact.

Figure 8.

The class hierarchy of the ontology.

Figure 8.

The class hierarchy of the ontology.

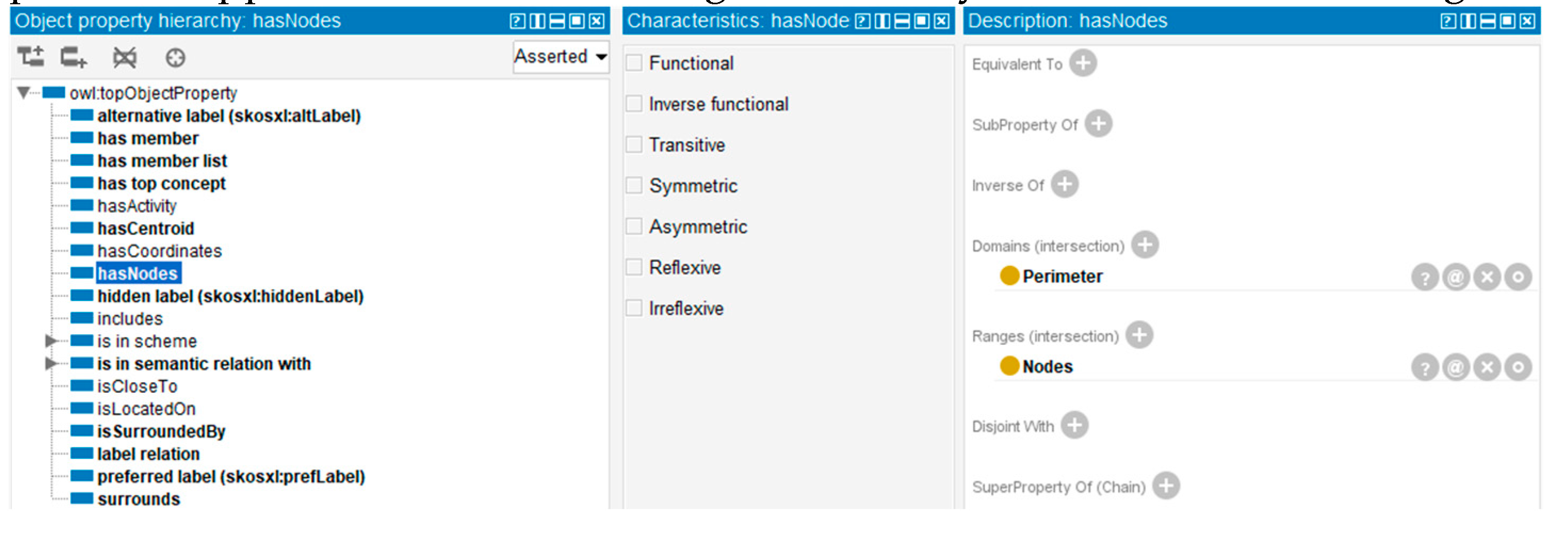

Object Properties

The present ontology includes object properties representing spatial relationships between classes, such as isLocatedOn, isCloseTo, surrounds, and isSurroundedBy (the inverse of surrounds). For example, a PublicSpace individual isSurroundedBy a Street individual, and vice versa. Additionally, all CITY classes and subclasses have the property hasCoordinates, linking to an individual of the Coordinates class.

Properties also enable legality checks for plots or buildings. The Perimeter and Nodes classes facilitate this by defining perimeters with lengths and nodes (vertices). A PropertyLine or ConstructionLine can include a perimeter, and queries can check if the perimeter aligns with the property or construction line. Any discrepancies indicate potential illegality. This illustrates the ontology's potential applications in urban design, data analysis, and decision-making.

Figure 9.

Object property hierarchy of the ontology and the hasNode object property example.

Figure 9.

Object property hierarchy of the ontology and the hasNode object property example.

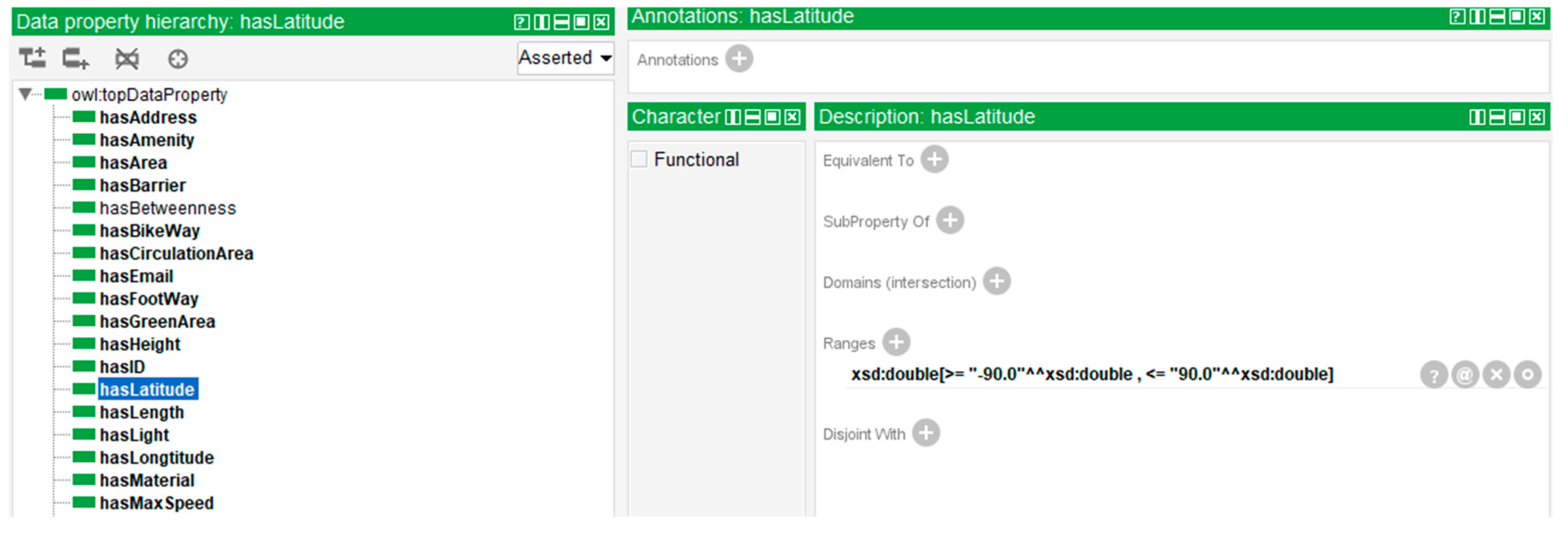

Data Properties

Data properties describe characteristics of class entities, with their values belonging to predefined data types (e.g., decimal, string). OWL properties have domains (subject) and ranges (object). For object properties, the range is another class entity, while for data properties, the range is a simple data type.

For example, the object property hasCoordinates links a class individual to a Co-ordinates individual. The Coordinates class then uses data properties like hasLatitude (with a range: xsd:double[>= "-90.0"^^xsd:double, <= "90.0"^^xsd:double]) and hasLongitude (with a range: xsd:double[>= "-180.0"^^xsd:double, <= "180.0"^^xsd:double]) to describe its specific attributes. Although hasCoordinates could be a data property taking a pair of numbers as input, this method ensures the correct input of values due to the lack of a predefined data type for such pairs with different ranges.

The ontology can include any relevant data for analysis, such as name, length, width, or address. In the context of sustainability, data properties like hasArea, hasGreenArea, hasRestArea, and hasCirculationArea are crucial for assessing urban spaces.

Figure 10.

Data property hierarchy of the ontology and the hasLatitude data property example.

Figure 10.

Data property hierarchy of the ontology and the hasLatitude data property example.

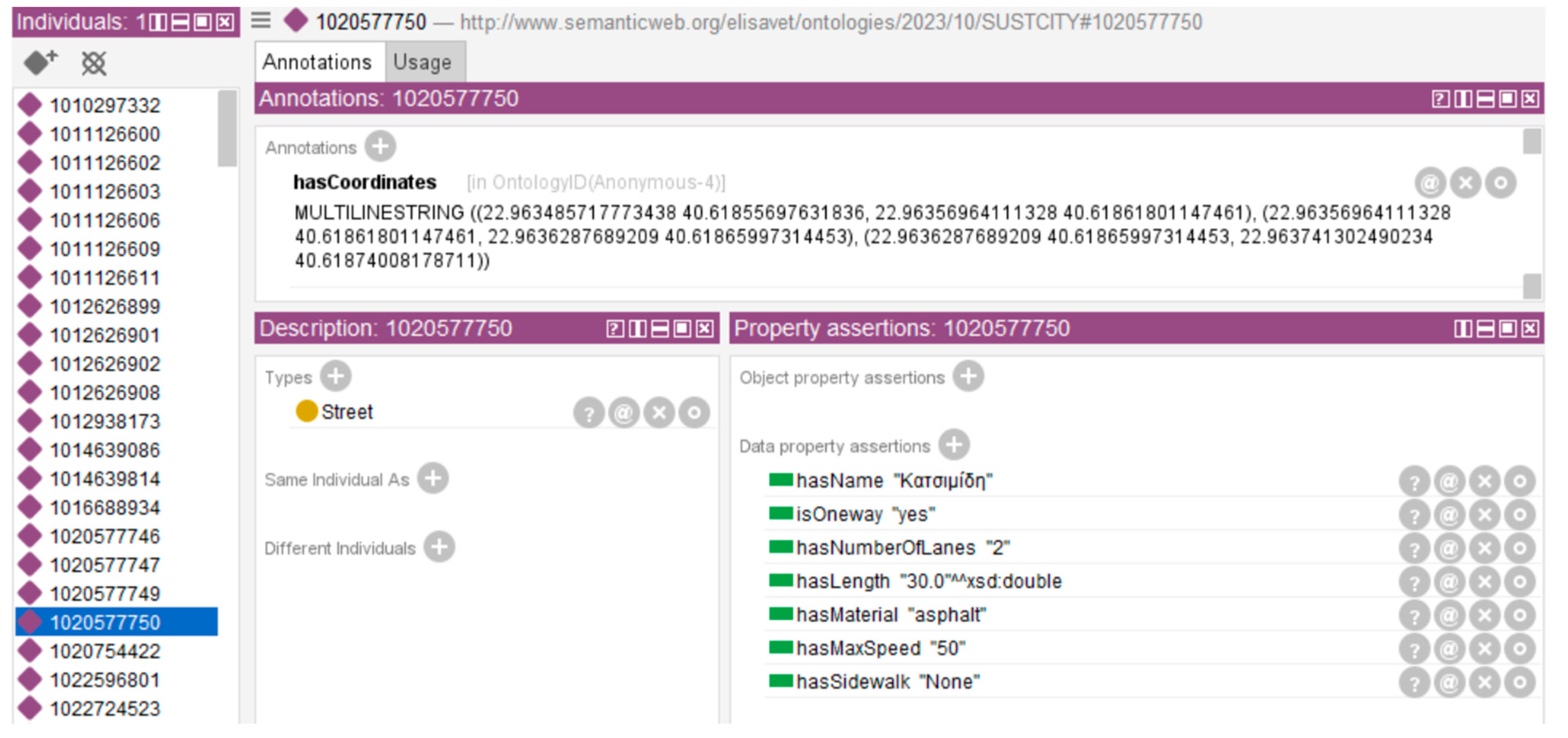

3.2.2. Ontology Population

Once the data has been structured into RDF triples, the next step is populating the ontology. The triples generated from the OSM data are used to populate the ontology with individuals—real-world instances of urban objects such as streets, parks, or buildings.

To automate this process, a script was developed to extract relevant urban features (streets, buildings, parks, squares, etc.) from OSM, analyze them, and then convert this information into RDF triples that align with predefined ontology classes. For example, each street in the OSM data becomes an individual within the "Street" class in the ontology, with attributes described using RDF predicates and objects. The script also processes urban networks (nodes and edges), calculating centralities and adding this information to the RDF triples. These triples are then mapped to the appropriate ontology properties, ensuring that the relationships between urban objects are preserved in the ontology.

In addition, the script handles geometric and morphological data, such as area calculations for parks and squares, integrating these measurements as attributes of the relevant individuals. This automated population of the ontology ensures that the urban sustainability framework is enriched with real-world data, ready for use in more advanced analyses or decision-making processes related to urban planning and sustainability. The result is a coherent and interconnected model of the urban landscape, represented semantically, that can be queried and analyzed using ontology-based reasoning tools.

3.3. Semantic Analysis

3.3.1. Urban Sustainability Ontology Development: Scenarios and Case Studies

The development of an urban sustainability ontology is a dynamic and iterative process, shaped by real-world scenarios and case studies. These practical applications helped refine both the ontology and the accompanying scripts, guiding the research in an Agile-like manner. Instead of following a linear path, the process evolved through continuous feedback and adjustments, ensuring that the methodology was responsive to new insights and data requirements.

This iterative approach, like Agile development in software engineering, allowed for incremental improvements in the research outcomes. Scenarios and case studies provided valuable test environments where the ontology was examined, refined, and adapted, ultimately ensuring its robustness and flexibility for urban sustainability analysis.

Data Extraction and Ontology Construction

The OpenStreetMap (OSM) platform provided a repository of complex urban data, which was extracted and structured using Python scripts, then integrated into Protégé’s ontology editor. This process enabled the conversion of raw geospatial information into RDF triples adhering to predefined ontology classes, creating a comprehensive framework to support urban sustainability analysis. The workflow enabled data to be structured into different formats, allowing diverse urban features, such as streets, parks, and intersections, to be represented as individuals within the ontology.

Once imported into Protégé, these individuals appeared in the Individuals tab, with all available properties mapped. For example, each individual representing an urban element was assigned attributes such as location, size, and type. This selective approach provided a streamlined method for converting OSM data into semantic classes.

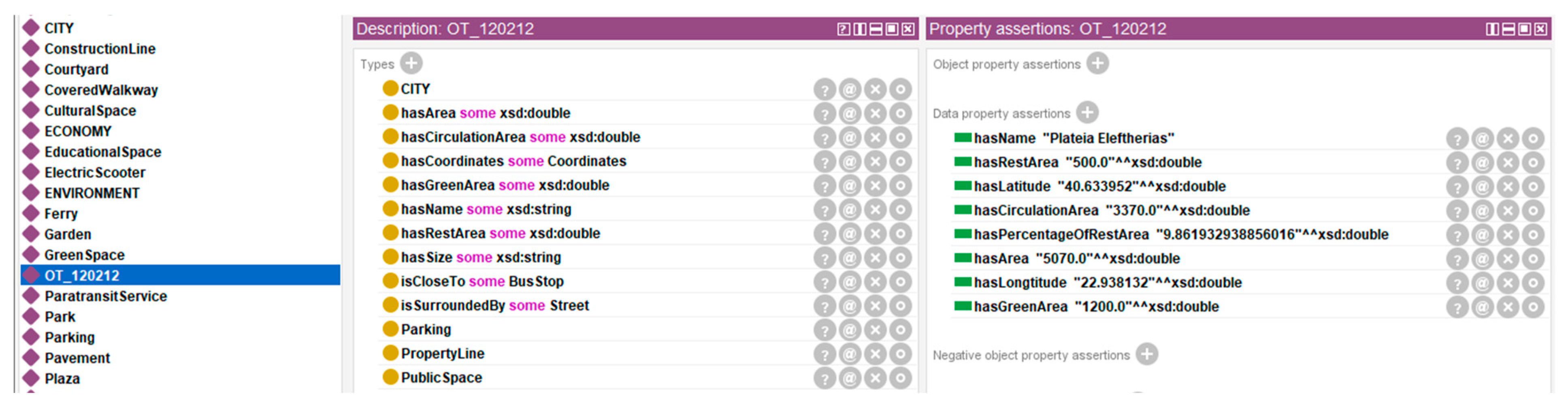

Figure 11.

Snapshot of the Protege's individuals tab after the import of RDF triples.

Figure 11.

Snapshot of the Protege's individuals tab after the import of RDF triples.

While the current scripts demonstrate key conversions, they do not yet cover all possible transformations. Instead, they serve as foundational examples that illustrate how various urban data properties can be mapped and linked within the ontology. This method ensures flexibility for future extensions and allows researchers to iteratively refine the ontology as new data is integrated.

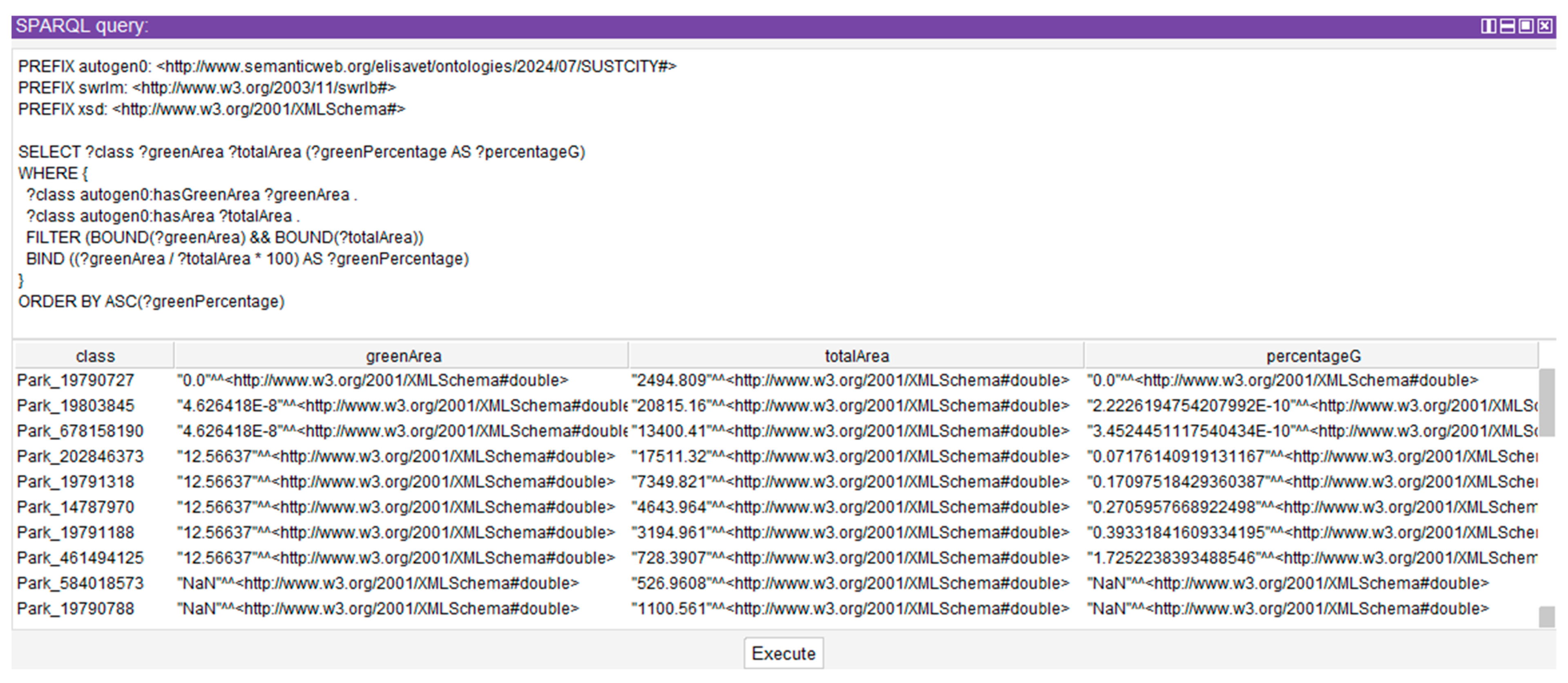

Reasoner and SPARQL Queries for Urban Analysis

With data integrated into Protégé as RDF triples, the ontology supports advanced knowledge representation and analysis. Protégé’s built-in reasoner detects inconsistencies in the data and refines the ontology by uncovering implicit relationships and ensuring that the imported information adheres to predefined rules.

At the same time, SPARQL queries provide a powerful tool for filtering and searching within the ontology. For example, a query can identify streets located near both bus stops and green spaces or perform calculations such as finding public areas where the percentage of green space is below a certain threshold. These queries also allow for aggregations, ranking, and ordering, enabling researchers to analyze trends, patterns, and potential correlations.

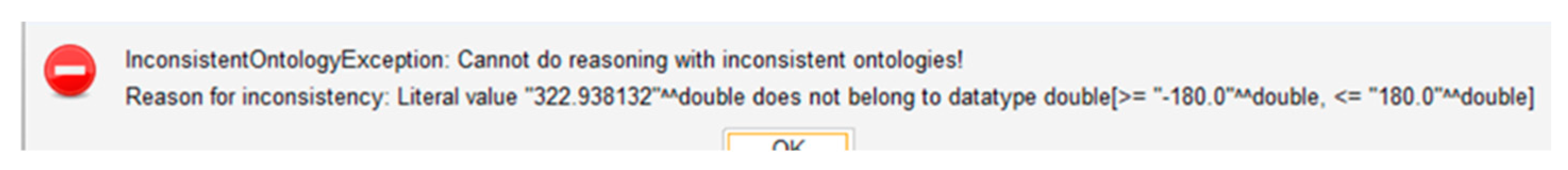

In a case study focusing on “Plateia Eleftherias” in Thessaloniki, SPARQL queries were used to analyze specific elements of the square, such as its name, coordinates, and land use areas. The reasoner uncovered inconsistencies, such as incorrect coordinates, while the SPARQL queries provided detailed data on the percentage of green, circulation, and rest areas.

Figure 12.

The Plateia Eleftherias’ individual with the input data, before running the reasoner.

Figure 12.

The Plateia Eleftherias’ individual with the input data, before running the reasoner.

Figure 13.

The error message from wrong input in coordinates.

Figure 13.

The error message from wrong input in coordinates.

Figure 14.

SPARQL query calculating and ranking green area percentages.

Figure 14.

SPARQL query calculating and ranking green area percentages.

Development of Sustainability Indices

The city ontology, enhanced with processed OSM data and network analysis, provides a foundation for developing and evaluating new sustainability indices. This section outlines conceptual approaches for creating these indices, though a full exploration extends beyond the present research.

The methodology for creating indices can follow the approach used for graph weight creation: combining multiple urban factors through formulas, each weighted by specific thresholds. For instance, an Accessibility Index might integrate factors like proximity to public transport, sidewalk availability, topography, and pavement materials. These factors, each given a value on a predefined scale, can be combined to create the final value of the Accessibility Index for the studied area.

Likewise, indices such as a Green Index that combines green space percentage and centrality values, can be developed. Although this chapter establishes a foundation for these indices, extensive research and experimentation are required for their creation.

Once calculated, these indices can be incorporated into properties like hasConnectivity, hasAccessibility, and hasGreen, that can be aggregated into a unified hasSustainability property. This allows for the creation of a sustainability matrix for evaluating and comparing cities’ sustainability levels and identifying areas or aspects requiring attention due to low sustainability values.

This methodology is dynamic and requires iterative adjustments before evolving into a formal and comprehensive framework for assessing urban sustainability. Once indices and respective object properties are established, these ontologies can work as assessment tools. By altering values in hypothetical scenarios, researchers could observe the impact of changes on the overall sustainability score. This approach aids in evaluating factors by identifying those influencing sustainability, highlighting points of risk, and revealing points of opportunity. For example, adding bus stops to observe their influence on the indices can unveil optimal locations for new bus stops, considering multiple factors simultaneously. Conversely, removing a green area might cause a more significant drop in values than removing another, signaling areas of vulnerability that warrant protection or enhancement. This process, borrowed from network analysis, finds application in this context as well.

Therefore, this integrated framework opens substantial opportunities for future research in urban sustainability, as it enables the systematic analysis of urban attributes and their interdependencies. By establishing a robust foundation for sophisticated sustainability indices, the framework not only meets current research objectives but also paves the way for future explorations in urban sustainability analysis.

3.3.2. Ontology Based Network Analysis: Network Analysis Indices

This research explores the conceptual foundations of

network analysis for sustainability insights using graphs generated from OSM data. While this study does not develop specific indices, it discusses the potential application of

graph theory to urban systems, offering an exploratory framework to understand the complexities of urban sustainability. This initial exploration provides valuable theoretical starting points, highlighting diverse possibilities as indicated by existing studies on urban network analysis, such as those by Derudder [

66]. Further investigation and empirical validation will be necessary to refine these conceptual tools and fully realize their potential.

Street Networks and Accessibility Indices

Network analysis of a city's street network offers profound insights into its structure, vulnerabilities, and opportunities. Graph theory provides a toolkit of centralities and indices, each highlighting different aspects of the city's functionality and relationships. This section outlines potential approaches to analyzing these aspects, with a particular focus on their conceptual relevance to urban sustainability.

A crucial metric is the diameter, measuring interconnectedness; a smaller diameter indicates better communication efficiency between vertices and a more interconnected web [

67]. Albert et al. [

56] emphasize that scale-free networks have a smaller diameter than exponential networks, suggesting more efficient link utilization.

Various studies have explored network structures in urban planning, examining grid-like and organic patterns and their impact on spatial configuration and connectivity [

58,

59,

68,

69]. Wang et al. introduce meshness and organic indices as metrics to quantify urban networks' organicity, offering a more detailed understanding of urban form and connectivity. The meshness coefficient (M), quantifies how organic or structured a graph is (Equation (1) and (2)). A square-like grid network, often seen in real cities, strikes a compromise between tree-like and complete networks. The organicity of the graph is further explored using the rv ratio (Equation (3)), providing insights into the presence of dead ends and 'unfinished' crossings [

67].

Degree distribution studies and fit-to-power-law tests reveal hierarchical structures among nodes. Porta et al. [

20] compare centrality distributions in self-organized versus planned cities. Centrality measures are pivotal in understanding the significance of nodes within the network. Betweenness identifies nodes acting as crucial bridges within the graph [

59,

61,

68,

70]. Closeness centrality highlights nodes with short average distances to all other nodes, indicating accessibility [

70]. Eigenvector emphasizes nodes connected to other well-connected nodes, indicating importance based on neighbors' importance [

60,

61,

71]. These centrality measures are valuable for urban planners. Identifying less-connected areas can optimize public transport connections and improve accessibility, as demonstrated by Huang et al. [

70]. Pinpointing key hubs can guide the strategic placement of accessible green spaces, as shown by Alavi et al. [

72].

A reverse analysis aimed at augmenting connectivity and resilience involves evaluating network strengths and weaknesses, including calculating the resilience and robustness of the network [

61,

73,

74,

75]. These approaches provide a foundational understanding of a city's adaptability to challenges and disruptions.

In sustainability analysis, metrics such as connectivity, proximity, and between-ness can guide urban planners in optimizing various aspects of the city's functionality. Understanding node interactions, spatial relationships, and their role in connecting disparate areas is instrumental in designing sustainable urban interventions.

Moreover, entropy indices, as explored by Gudmundsson and Mohajeri [

76], provide insights into the network's heterogeneity or homogeneity. This analysis unveils intricate patterns and order within urban street networks, opening avenues for examining diversity and mixed-use considerations in sustainability planning. This holistic perspective aligns with the diverse needs of urban populations.

Incorporating the results of such analysis into the ontology or leveraging them for calculating sustainability parameters enhances our understanding of urban sustainability, fostering a comprehensive perspective on city dynamics.

Public Spaces and Green Indices

Apart from the accessibility factor in a city that can be examined through the analysis of its road network, analyzing the spatial distribution, and spread of green and public spaces can also be insightful for a sustainability analysis.

To begin with, the existence of green in any public space, like a square or a park, can be searched through the OSM’s tags. Then, a 'natural' column can be added comparing the coordinates of natural elements and squares. If a natural element falls within a square, it is added to the square’s dataframe.

A graph of green public spaces can be created, with nodes representing green public spaces. The edges of the graph can be defined depending on the analysis purpose:

Distance-based Edges (Accessibility): Connect nodes based on proximity, using spatial clustering or thresholds (e.g., walking distance). For example, Comber et al. [

77] used GIS-based network analysis to determine the accessibility of urban greenspace for different ethnic and religious groups, providing a flexible and replicable model.

Functional Edges (Diversity and Mixed Development): Connect spaces with simi-lar recreational purposes or features, revealing diversity and mixed use. The study by Guenat et al. [

78] on social network analysis in greenspace conservation reveals how functional connectivity between green spaces can be lacking, which is a critical consideration for enhancing urban green space networks.

Combining Multiple Factors: Use multiple criteria (distance, transport, connectivity) to define edges with weighted thresholds. For example, the work by Mougiakou and Photis [

79] on urban green space network evaluation and planning used connectivity and raster GIS analysis to optimize accessibility, demonstrating how multiple factors can be integrated into green space network analysis.

Network analysis of the resulting graphs can provide insights into the distribution of public spaces, their proximity to points of interest, accessibility, and diversity. For instance, research by Alavi et al. [

72] explores the connectivity of urban green spaces and their role in environmental justice and ecosystem services. Sevtsuk [

71] revisits the betweenness index to estimate pedestrian flows, offering insights into how well-connected public spaces are within the urban network. Sevtsuk and Kalvo [

80] further contribute to this understanding by modeling pedestrian activity to enhance the strategic placement of green spaces. Ma [

81] also applies spatial network analysis to evaluate spatial equity in green space distribution, emphasizing proximity and connectivity. These analyses offer a better understanding of the urban network and its sustainability, guiding urban planners in optimizing the design of public spaces.

The results of such network analysis can be used to create sustainability-related indices, such as green or accessibility indices, which can be added to the ontology as data for further examination and semantic comparison. Srikanth and Schroepfer [

82] conducted a network science-based analysis of urban green spaces in Singapore, which could serve as a model for such indices.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we explored innovative approaches to urban sustainability by integrating semantics and graph theory as tools for advancing urban transformation within the context of the digital and green transition. Our research aimed to construct an analytical framework to address the multifaceted challenges of urban sustainability and climate neutrality. This work provides a foundation for a methodological approach that could guide the development of sustainability metrics and assessments, ultimately leading to the creation of a unified sustainability index. This framework reflects the growing need for cities to transition into more adaptive, resilient, and data-driven ecosystems, aligning with the city-as-a-platform concept.

We developed a city ontology to structure and analyze extensive urban datasets, integrating data and metadata from OpenStreetMap, to illustrate its potential for urban sustainability analysis. The ontology's scope could be expanded to include additional sustainability dimensions—economic, environmental, and social—while also integrating with other existing ontologies for a more comprehensive assessment. This methodology represents an initial step toward creating and evaluating indices that could contribute to a unified sustainability index, a critical element in achieving long-term sustainability goals.

A key aspect of this research was the introduction of an automated method for populating the ontology using geospatial data, streamlining system analysis, and unifying disparate data formats. The data extraction and analysis modules emerged as crucial analytical tools, enabling the convergence of tabular precision, spatial context, and graph theory to deepen our understanding of urban networks and sustainability. While the exact parameters for sustainability indices are yet to be universally defined, the methodology outlined here provides a clear path for their development and validation. This research provides a systematic approach that urban planners and policymakers can utilize to design, assess, and validate sustainability indicators, set goals, and monitor progress.

Our findings suggest that a semantic approach, combined with network analysis, holds substantial promise for advancing urban sustainability assessment and analysis. The ability to integrate and analyze diverse data sources within a unified framework offers a more holistic view of urban systems, which is essential for sustainable urban development. The methodology also points toward the potential development of sustainability indices, providing a foundation for formalizing sustainability measures that can guide cities toward becoming climate-neutral and resilient ecosystems.

The automated population of the ontology using geospatial data also highlights the potential to apply semantic technologies across other databases and domains. For example, the same principles could be extended to include databases such as BIM, CityGML, and environmental or economic datasets. Integrating tools like CityGML into the ontology further supports the comprehensive management and utilization of data for analysis and research. As the ontology continues to expand, the process of importing diverse data sources contributes to a more holistic representation and understanding of urban systems. This iterative expansion enables the identification of previously unseen patterns and relationships, potentially leading to the development of measurable indices and a formal framework for sustainability analysis.

Future research should focus on expanding the range of sustainability indices and refining the semantic methodology presented in this paper. Continued enhancement of the ontology structures and the merging of relevant ontologies will improve the precision and applicability of semantics in environmental and sustainability analyses. Integrating additional data sources and formats, such as CityGML and BIM models, will lead to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of urban sustainability. Further exploration of network analysis could reveal new patterns and relationships, offering deeper insights into urban sustainability and resilience.

Collaboration across disciplines is essential to advance this research. The complex and interconnected nature of urban sustainability challenges demands collective expertise and interdisciplinary dialogue. By fostering collaboration and embracing diverse perspectives, we can more effectively address the wide-ranging and multifaceted challenges cities face today in the digital and green transition.

The integration of this ontology with other urban applications holds significant potential beyond the current case studies. For instance, smart city frameworks could be enhanced by incorporating real-time sensor networks to monitor environmental data such as air quality, energy consumption, and traffic patterns. This real-time data integration would enable dynamic and responsive management of cities, allowing for better adaptation to environmental challenges. Another promising avenue is the incorporation of IoT (Internet of Things) devices within the urban ontology, facilitating comprehensive environmental monitoring and enabling more precise sustainability assessments. This approach could also support various applications, including waste management, water conservation, and energy optimization—all crucial to achieving climate-neutral goals.

As the ontology evolves, it could integrate data from environmental impact assessments, climate modeling, and sustainability reporting tools, providing a unified platform for managing and analyzing urban sustainability in the context of broader climate goals. If fully realized, this holistic framework could become an invaluable tool across all stages of urban development—from architectural design and urban planning to monitoring, renovation, and future scenario planning in virtual twin environments. Such an approach would significantly enhance the capacity to design, assess, and optimize urban systems for sustainability and resilience.

This methodology provides the potential for developing sustainability indices that allow for the formal comparison and classification of sustainable cities. Future research should explore additional applications of network analysis in urban sustainability, further refine the presented methodology, and expand the range of sustainability indices developed. By offering a set of tools to assess climate indicators, sustainability objectives, and strategic goals, this framework has the potential to significantly advance urban planning. Moreover, collaboration across disciplines is key to realizing these goals and developing a comprehensive urban model aimed at achieving climate neutrality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Material S1: OWLdoc of the unpopulated ontology, Supplementary Material S2: OWLdoc of the populated ontology with OSM data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P., C.B. and D.G.; methodology, E.P. and C.B.; software, E.P.; validation, C.B. and D.G.; formal analysis, E.P.; investigation, E.P.; data curation, E.P.; writingȔoriginal draft preparation, E.P.; writingȔreview and editing, E.P., C.B. and D.G.; supervision, C.B and D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai, X.; Surveyer, A.; Elmqvist, T.; Gatzweiler, F.; Güneralp, B.; Parnell, S.; Webb, R. Defining and advancing a systems approach for sustainable cities. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2016, 23, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Solecki, W.; Romero-Lankao, P. (Eds.). (2018). Climate change and cities: Second assessment report of the urban climate change research network. Cambridge University Press.

- Bibri, S.; Krogstie, J. Smart sustainable cities of the future: An extensive interdisciplinary literature review. Sustainable Cities and Society 2017, 31, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Patten, B. Defining and predicting sustainability. Ecological Economics 1995, 15, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinberg, R.; Lerch, D. (2010). What is sustainability. In The post carbon reader (pp. 11-19). Post Carbon Institute.

- Farley, H.; Smith, Z. (2020). Sustainability: If inter everything, is it nothing? Routledge.

- Sodiq, A.; Baloch, A.; Khan, S.; Sezer, N.; Mahmoud, S.; Jama, M.; Abdelaal, A. Towards modern sustainable cities: Review of sustainability principles and trends. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 227, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, H. (2001). Creating Sustainable Cities. Green Books.

- Galderisi, A.; Colucci, A. (2018). Smart, Resilient and Transition Cities: Emerging Approaches and Tools for a Climate-Sensitive Urban Development. Elsevier.

- Pickett, S.; Cadenasso, M.; Grove, J. Resilient cities: Meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms. Landscape and Urban Planning 2004, 69, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravantinos, A. (2007). Urban planning: Towards a sustainable development of the built environment. Symmetria.

- Gibson, R. Sustainability assessment: Basic components of a practical approach. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2006, 24, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Zhang, X. (2023). Leveraging big data analytics for urban planning: A study using the Big Data Analytics Efficiency Test. ResearchGate.

- Kuster, F.; Hippolyte, J.-L.; Rezgui, Y. The UDSA ontology: An ontology to support real-time urban sustainability assessment. Advances in Engineering Software 2020, 140, 102731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, E.; Athanassiadis, A.; Psyllidis, A.; Binder, C. R. (Eds.). (2020). Sustainability assessment of urban systems (pp. 332-350). Cambridge University Press.

- Komninos, N.; Panori, A.; Kakderi, C. (2020). Smart City Ontology 2.0.

- Feleki, E.; Vlachokostas, C.; Moussiopoulos, N. Holistic methodological framework for the characterization of urban sustainability and strategic planning. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 243, 118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, S.; Lehmann, J.; Ngonga Ngomo, A.-C. (2011). Introduction to linked data and its lifecycle on the web. In Reasoning on the Web in the Big Data Era (pp. 1-75). Springer.

- Zhang, X.; Beetz, J.; Weise, M. Interoperable data models for linked building data. Automation in Construction 2017, 81, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, E.; Karanikolas, N.; Kaimaris, D. A GIS for urban sustainability indicators in spatial planning. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 2012, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Métral, C.; Falquet, G.; Vonlanthen, M. (2007). An Ontology-based Model for Urban Planning Communication. In J. Teller, J. R. Lee, & C. Roussey (Eds.), Ontologies for Urban Development (Vol. 61, pp. 61–72). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, G.; Van Harmelen, F. (2004). A semantic web primer. MIT Press.

- Panagoulia, E.; Lancaster, Z. (2021). Semantic web ontologies for building objects and their performance data. In Proceedings of Building Simulation 2021.

- Komninos, N.; Bratsas, C.; Kakderi, C.; Tsarchopoulos, P. Smart city ontologies: Improving the effectiveness of smart city applications. Journal of Smart Cities 2019, 1, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, K. (2016). Sustainable landscape planning in selected urban regions. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Tampouridou, A.; Pozoukidou, G. Smart cities and urban sustainability: Two complementary and inter-related concepts. Journal of European Real Estate Research 2018, 11, 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Von Richthofen, A.; Herthogs, P.; Kraft, M.; Cairns, S. Semantic City Planning Systems (SCPS): A Literature Review. Journal of Planning Literature 2022, 37, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvennoinen, H.; Chadzynski, A.; Farazi, F.; Grišiūtė, A.; Shi, Z.; Von Richthofen, A.; Cairns, S.; Kraft, M.; Raubal, M.; Herthogs, P. A semantic web approach to land use regulations in urban planning: The OntoZoning ontology of zones, land uses and programmes for Singapore. Journal of Urban Management 2023, 12, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Jennings, I. (2008). Cities as sustainable ecosystems: Principles and practices. Island Press.

- Thiele, L. (2016). Sustainability.

- Giovannoni, E.; Fabietti, G. (2013). What is sustainability? A review of the concept and its applications. In Integrated reporting: Concepts and cases that redefine corporate accountability (pp. 21-40). Springer.

- Berners-Lee, T.; Hendler, J.; Lassila, O. The Semantic Web. Scientific American 2001, 284, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Bizer, C. Exploring the geospatial semantic web with DBpedia mobile. Journal of Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web 2009, 7, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andročec, D.; Novak, M.; Oreški, D. Using Semantic Web for Internet of Things interoperability: A systematic review. International Journal on Semantic Web and Information Systems 2018, 14, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, T.; Bizer, C. (2011). Linked data: Evolving the web into a global data space (1st ed.). Morgan & Claypool. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, P. E.; Chondrokostas, E.; Bratsas, C.; Filippidis, P.-M.; Bamidis, P. D. A Medical Ontology Informed User Experience Taxonomy to Support Co-creative Workflows for Authoring Mixed Reality Medical Education Spaces. 2021 7th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN) 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratsas, C.; Kapsas, G.; Konstantinidis, S.; Koutsouridis, G.; Bamidis, P. D. A semantic wiki within moodle for Greek medical education. 2009 22nd IEEE International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems. [CrossRef]

- Bratsas, C.; Koutkias, V.; Kaimakamis, E.; Bamidis, P.; Maglaveras, N. Ontology-based Vector Space Model and Fuzzy Query Expansion to Retrieve Knowledge on Medical Computational Problem Solutions. 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2007, 3794–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A. Z.; Bratsas, C.; Makris, G. C.; Garoufallou, E.; Tsiantos, V. Interoperability-Enhanced Knowledge Management in Law Enforcement: An Integrated Data-Driven Forensic Ontological Approach to Crime Scene Analysis. Information 2023, 14, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A. Z.; Kornilakis, A.; Makris, G. C.; Bratsas, C.; Tsiantos, V.; Antoniou, I. Semantic Representation of the Intersection of Criminal Law & Civil Tort. Data 2022, 7, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippidis, P.-M.; Dimoulas, C.; Bratsas, C.; Veglis, A. A unified semantic sports concepts classification as a key device for multidimensional sports analysis. 2018 13th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation and Personalization (SMAP) 2018, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampatakis, S.; Bratsas, C.; Zamazal, O.; Filippidis, P. M.; Antoniou, I. Alignment: A Hybrid, Interactive and Collaborative Ontology and Entity Matching Service. Information 2018, 9, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratsas, C.; Chrysou, D. E.; Eftychiadou, E.; Kontokostas, D.; Bamidis, P. D.; Antoniou, I. (2012, April). Semantic Web Game Based Learning: An I18n approach with Greek DBpedia. In LiLe@ WWW.

- Kontokostas, D.; Bratsas, C.; Auer, S.; Hellmann, S.; Antoniou, I.; Metakides, G. Internationalization of Linked Data: The case of the Greek DBpedia edition. Journal of Web Semantics 2012, 15, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.; Ion, P.; Dimou, A.; Bratsas, C.; Sperber, W.; Kohlhase, M.; Antoniou, I. (2012). Bringing Mathematics to the Web of Data: The Case of the Mathematics Subject Classification. Στο E. Simperl, P. Cimiano, A. Polleres, O. Corcho, & V. Presutti (Επιμ.), The Semantic Web: Research and Applications (τ. 7295, σελ. 763–777). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Bratsas, C.; Chondrokostas, E.; Koupidis, K.; Antoniou, I. The Use of National Strategic Reference Framework Data in Knowledge Graphs and Data Mining to Identify Red Flags. Data 2021, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, N.; McGuinness, D. (2001). Ontology development 101: A guide to creating your first ontology. Stanford University.

- Cohnitz, D.; Smith, B. (2003). Assessing ontologies: The question of human origins and its ethical significance. In E. Runggaldier & C. Kanzian (Eds.), Persons: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 43-61). Springer.

- Ferrer, R. Semantic interoperability and ontologies in computer science. Journal of Computer Science Research 2021, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bröring, A.; Meier, A. Geospatial ontologies and digital twins. Journal of Urban Technology 2016, 23, 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-J. Visual architectural topology: An ontology-based topological tool for use in an architectural case library. Computer-Aided Design & Applications 2013, 10, 929–937. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-J. The STG pattern – Application of a “semantic-topological-geometric” information conversion pattern to knowledge-based modeling in architectural conceptual design. Computer-Aided Design & Applications 2017, 14, 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-J. Design criteria modeling - Use of ontology-based algorithmic modeling to represent architectural design criteria at the conceptual design stage. Computer-Aided Design & Applications 2016, 13, 549–557. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y. CityGML and its role in urban modeling. Sustainability 2020, 12, 300. [Google Scholar]

- West, D.B. Introduction to graph theory.

- Albert, R.; Jeong, H.; Barabási, A.-L. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature 2000, 406, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, M.; Memarmontazerin, S.; Soleimani, S. (2018). Where to look for power Laws in urban road networks? Applied Network Science. [CrossRef]

- Barthélemy, M. (2011). Spatial networks. Phys Rep.; 499:1–101.

- Porta, S.; Crucitti, P.; Latora, V. (2006a). The network analysis of urban streets: A dual approach. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 369, 853–866. [CrossRef]

- Porta, S.; Crucitti, P.; Latora, V. (2006b). The Network Analysis of Urban Streets: A Primal Approach. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G. Urban spatial order: Street network orientation, configuration, and entropy. Applied Network Science 2019, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G. Street Network Models and Indicators for Every Urban Area in the World. Geographical Analysis 2022, 54, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.; Bechhofer, S. (2009). SKOS Simple Knowledge Organization System Reference. W3C Recommendation. Retrieved from http://www.w3.org/TR/skos-reference.

- Costa, D. (2023). Synonym. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 29, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/synonym.

- e-ΠOΛΕOΔOΜΙA. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://gis.epoleodomia.gov.gr/v11/#/22.9579/40.6295/15.

- Derudder, B. Network Analysis of ‘Urban Systems’: Potential, Challenges, and Pitfalls. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 2021, 112, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Resilience of self-organised and top-down planned cities—a case study on London and Beijing street networks. PLOS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, J.; Gautrais, J.; Reeves, N.; Solé, R.; Valverde, S.; Kuntz, P.; et al. Topological patterns in street networks of self-organized urban settlements. Eur Phys JB 2006, 49, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, A.; Scellato, S.; Latora, V.; Porta, S. Structural properties of planar graphs of urban street patterns. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Chiou, S.; Li, W. Accessibility and street network characteristics of urban public facility spaces: Equity research on parks in Fuzhou city based on GIS and space syntax model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevtsuk, A. Estimating Pedestrian Flows on Street Networks: Revisiting the Betweenness Index. Journal of the American Planning Association 2021, 87, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S. A.; Esfandi, S.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A. R.; Tayebi, S.; Shamsipour, A.; Sharifi, A. Assessing the Connectivity of Urban Green Spaces for Enhanced Environmental Justice and Ecosystem Service Flow: A Study of Tehran Using Graph Theory and Least-Cost Analysis. Urban Science 2024, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, Y.; Heinimann, H. R. Robustness response of the Zurich road network under different disruption processes. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2020, 81, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, R.; Wentao, Y.; Yuting, H.; Zihao, L. Defining urban network resilience: A review. Frontiers of Urban and Rural Planning 2024, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, D.; Kulkarni, S. A Social Network Analysis of World Cities Network. 2017 2nd International Conference on Computational Systems and Information Technology for Sustainable Solution (CSITSS) 2017, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, A.; Mohajeri, N. Entropy and order in urban street networks. Scientific Reports 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Brunsdon, C.; Green, E. Using a GIS-based network analysis to determine urban greenspace accessibility for different ethnic and religious groups. Landscape and Urban Planning 2008, 86, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenat, S.; Dougill, A. J.; Dallimer, M. Social network analysis reveals a lack of support for greenspace conservation. Landscape and Urban Planning 2020, 204, 103928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougiakou, E.; Photis, Y. N. Urban green space network evaluation and planning: optimizing accessibility based on connectivity and raster GIS analysis. European Journal of Geography 2014, 4, 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sevtsuk, A.; Kalvo, R. Modeling pedestrian activity in cities with urban network analysis. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F. Spatial equity analysis of urban green space based on spatial design network analysis (sDNA): A case study of central Jinan, China. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 60, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, A. D.; Schroepfer, T. Network Science-based Analysis of Urban Green Spaces in Singapore. International Journal on Smart and Sustainable Cities 2023, 01, 2340004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).