1. Introduction

Since there is a global demand for renewable energy that minimizes carbon emissions, wind turbine systems became an attractive research area for the academic and industrial sectors. The current installed modern large-scale, i.e. multi-MW WECSs typically operate at variable speed [

1,

2]. For these systems, DFIG still stands out as one of the best options for the manufacturing and supplier sectors, due to its important advantages such as requiring small-sized and low-cost power electronic converters and facilitating independent active and reactive power control [

3]. Therefore, its market share is expected to continue to increase in the next 5-10 years [

4]. However, from a technical standpoint, DFIG is quite interesting and a bit difficult to understand compared to its traditional counterparts such as squirrel-cage induction generator (SGIG), and permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG).

In these respect, it is considered that even though the need for engineers employed as maintenance, service and research staff for the industry field is constantly increasing in the world energy sector but most of the new graduated engineers have a serious lack of knowledge about renewable energy conversion systems. Therefore, a particular aim of this study is to fulfill the gap and address the needs of new entrants in this field regarding to the key issues of variable speed turbine systems. Moreover, the paper aims at two points: first, to develop an easy-to-use dynamic model to provide greater physical and practical understanding with effective simulation tests on the basic theory of DFIG; Secondly, to demonstrate how to carry out various tests such as smooth excitation at system startup and to test the working principle of variable speed, constant voltage and constant frequency, stand-alone operation with different types of loads and no-load conditions, connection of DFIG to the grid and intentional islanding, and some other issues from both theoretical and practical perspectives.

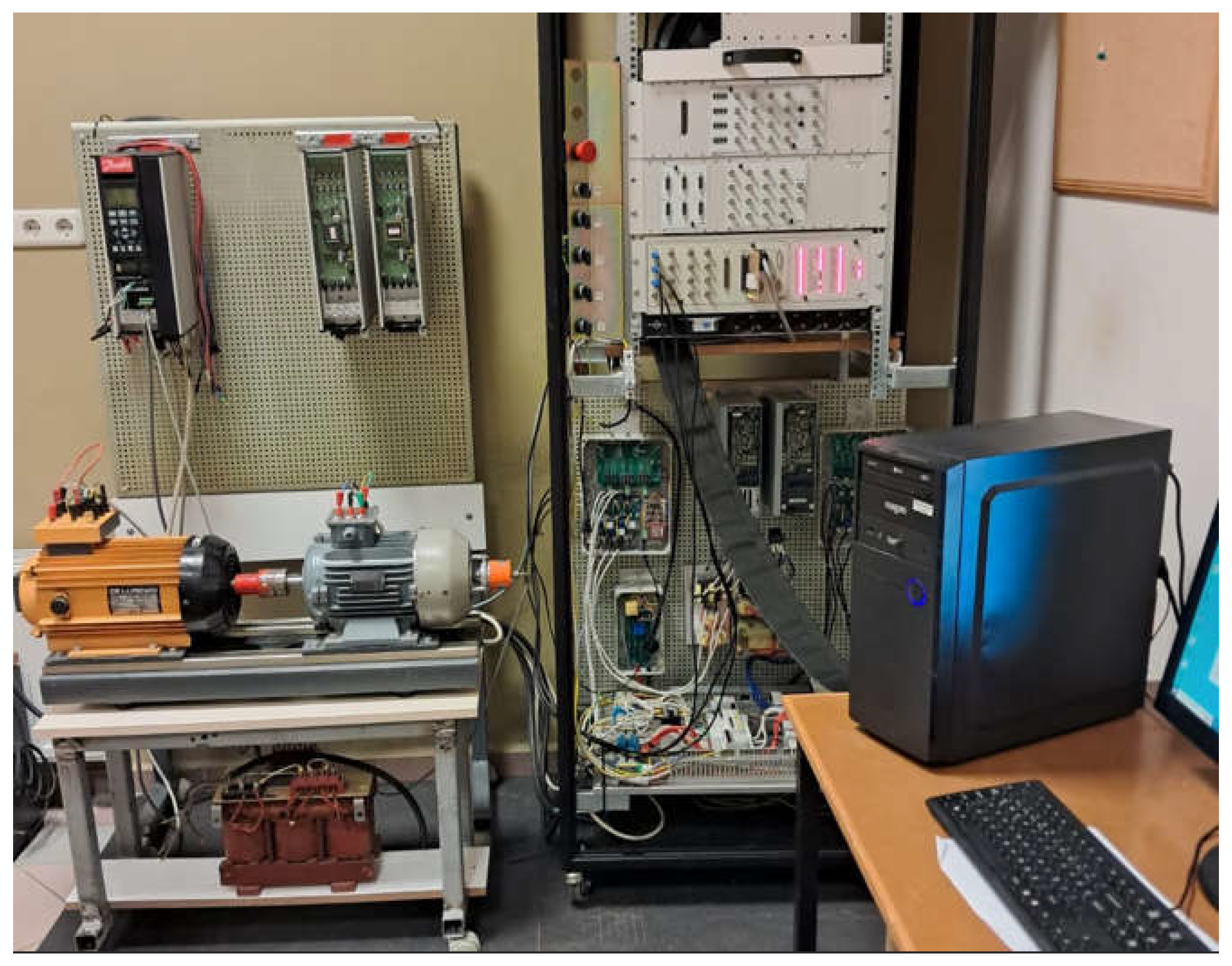

From a research and education perspective real experiments of WECS are impractical and applicable less frequently due to lack of access to real systems in the installation sites. Therefore, research and teaching activities regarding WECSs are generally performed on lab scale test setups, but mostly with computer simulation using well-known commercial software packages, such as Matlab/Simulink, Plecs, DigSling, Simpow, and the others. These software packages offer pre-built demo simulation models of physical systems, which are often complex and created with some special toolbox that users might be unfamiliar with [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In addition, with regard to these models, it is often difficult to establish the relationship between the mathematical model equations of physical systems and their pre-built simulation models. Thus, these pre-build models are not very effective to understand the underlying relationships and also not appropriate for all real operational requirements in DFIG-based WECSs. Therefore, various modeling approaches have been proposed to meet different research requirements, usually related to large-scale grid-connected variable speed DFIG-WECSs. Moreover, many research and case studies have been proposed to analyze the steady-state and dynamic behavior of the DFIG and furthermore to improve the overall control performance and operational safety, increase the system efficiency and predict and solve the problems under normal and fault conditions. A significant amount of literature on these studies can be found in [

3,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] and references therein. In these studies, the aerodynamic model of wind turbines has also been extensively investigated. Therefore, to better simplify the system structure and focus on the DFIG machine itself, the above-mentioned extreme points are not considered in this study.

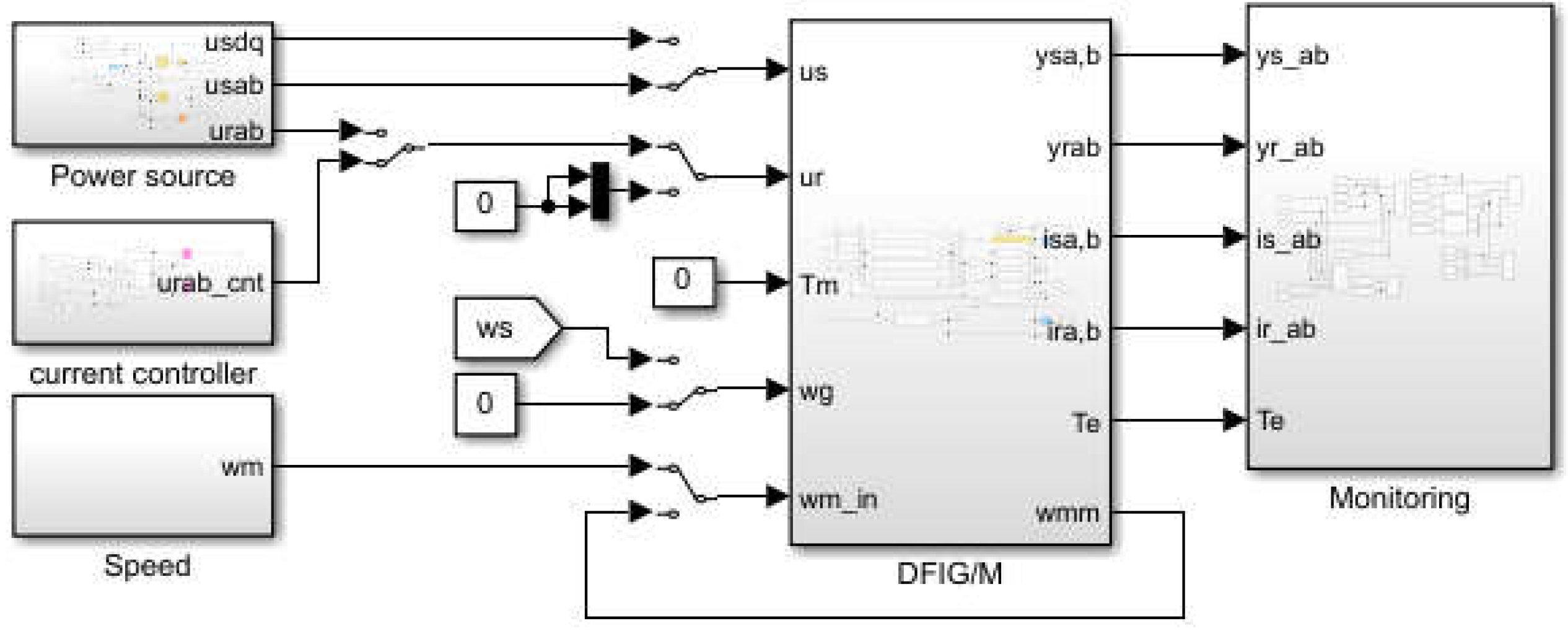

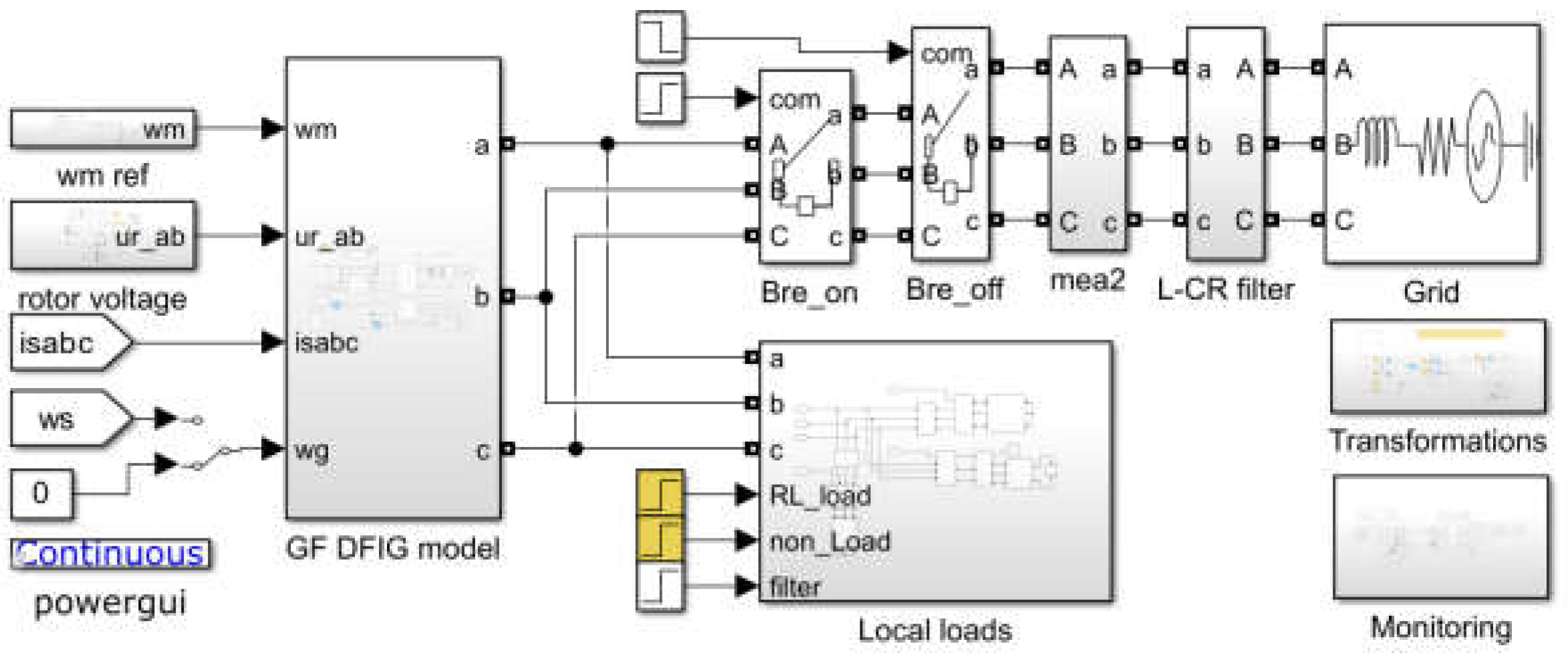

The proposed modeling and simulation approach takes into account the difference between grid-connected and stand-alone operation of DFIG and provides a good opportunity to test both operating modes. It has the advantage that the user can directly build his own model using the building blocks of the appropriate software and optionally take into account the parameter variation of DFIG. In addition, free acceleration testing of DFIM (motoring mode) can be performed using the grid-connected model version to verify its accuracy.

Accordingly, this paper is organized as follows: The basic structure and theoretical background of the DFIG-WEGS are briefly explained with intuitive illustrations in Section II. To clarify the complexity arising from alternative coordinate frames and selectable state variables, the dynamic model equations of DFIG are reviewed. Then, various DFIG models available in the literature are addressed and difference of stand-alone and grid connected DFIG models are discussed in Section III. The structure and building of the proposed simulation model in Matlab/Simulink is presented in Section IV, Section V is devoted to simulation and experimental tests of DFIG. Conclusions are given in Section VI.

2. Operation Principle of DFIG-WEGS

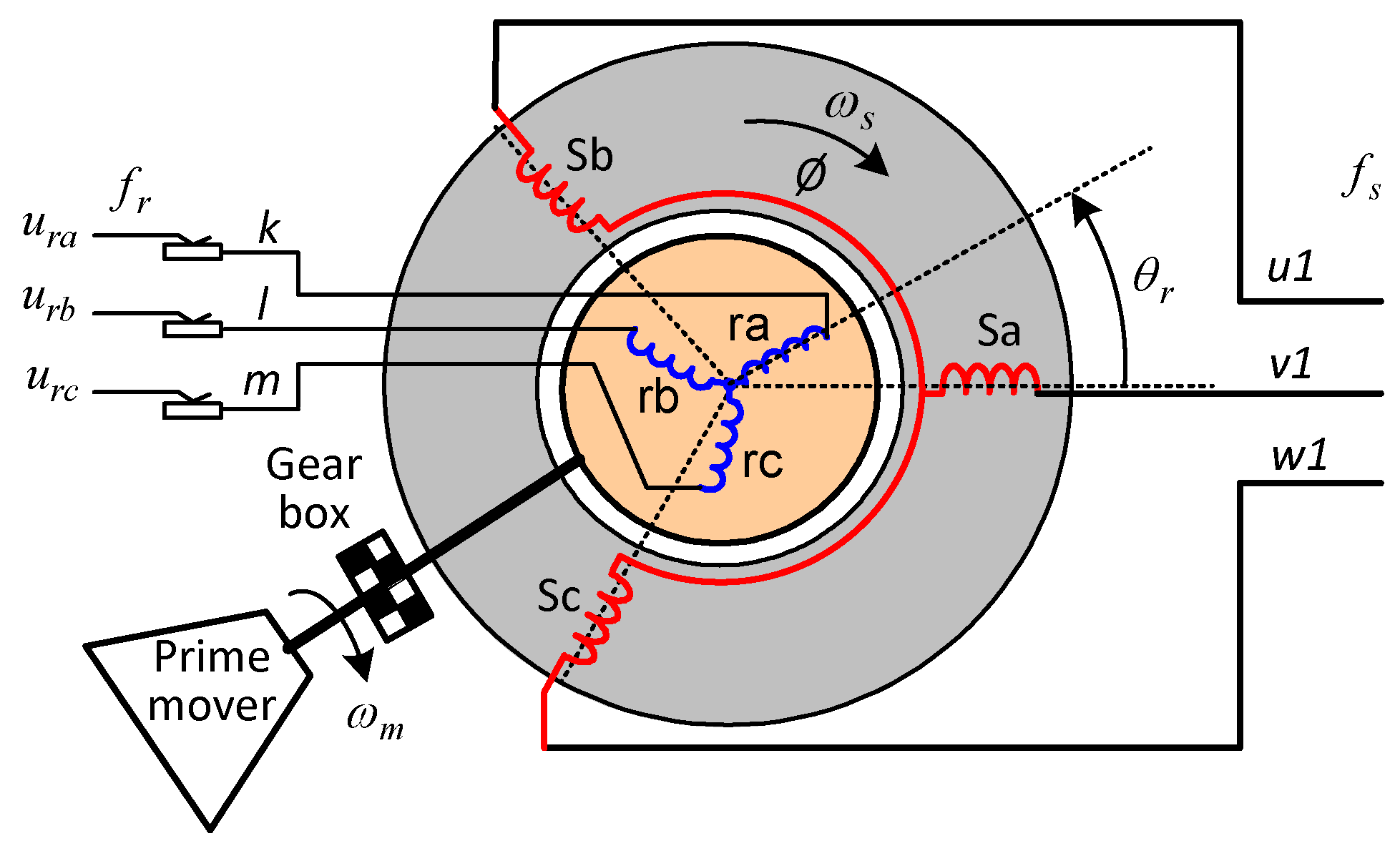

The DFIG is a wound (slip ring) rotor type induction machine, and its construction simply consists of a three-phase stationary winding fixed to the stator and a three-phase rotary winding fixed to the rotor as shown in

Figure 1. Since the stator and rotor windings are fed from an ac power source, it is often called a doubly fed induction machine (DFIM) and can therefore be operated in several modes; motor operation, transformer operation and generator operation [

9,

10,

11]. As seen in

Figure 1, a prime mover (e.g. diesel engine, wind turbine or other similar unit) is needed to rotate the DFIG rotor shaft for both transformer and generator operations, these are summarized below;

1. In motor operation, the prime mover must be disabled and the rotor windings are short-circuited while the stator winding must be supplied with nominal AC voltage. The adjustment of external resistors connected to the rotor terminals allows the machine to operate at maximum starting torque, as in the old uses of DFIM. In real applications, motor operation is also possible in an alternative way, by supplying nominal AC voltage to the rotor winding and short-circuiting the stator winding.

2. To operate the DFIM as a generator, the prime mover must be enabled to rotate the rotor. In this case, two different operations are possible; operating as a rotating transformer when the rotor (as field winding) is supplied from appropriate ac voltage source, at constant magnitude and frequency, then the stator winding generates an ac voltage at varying frequency and amplitude depending on variation of rotor mechanical angular speed, ωm. If the rotor speed ωm is kept constant, then the stator can generate an ac voltage at constant magnitude and frequency depending on constant slip and slip angle.

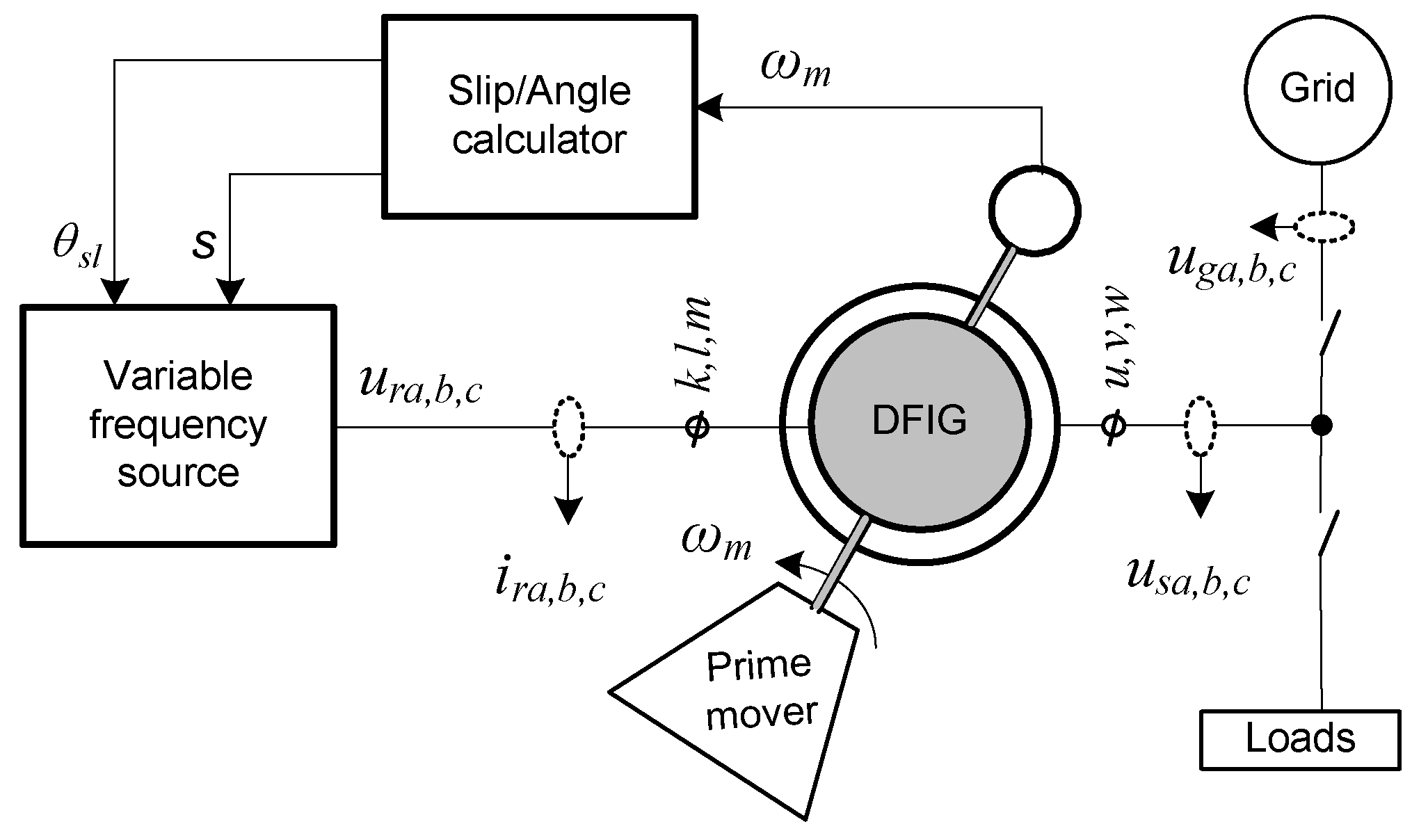

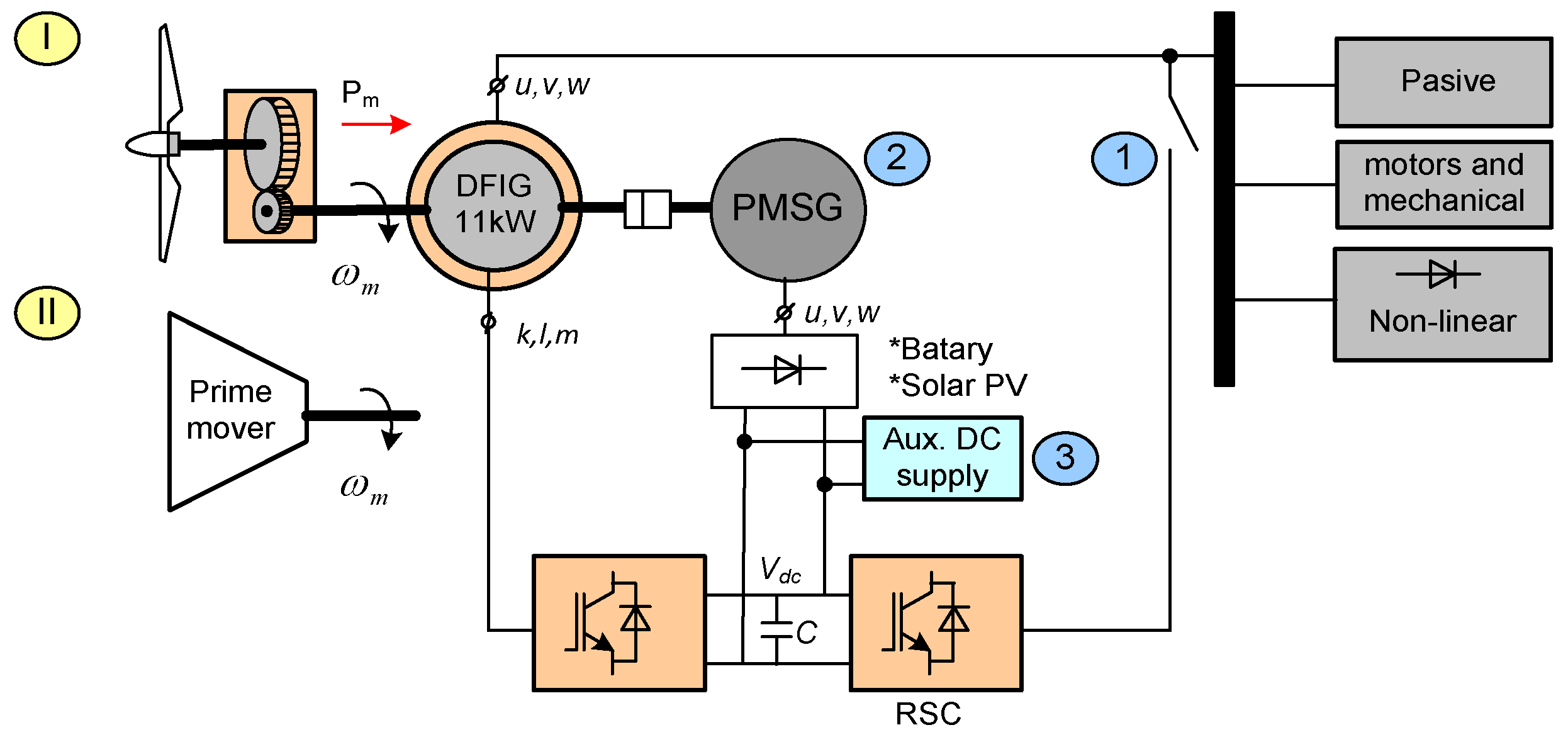

The basic structure of a DFIG based WPCS is illustrated in

Figure 2, which helps to more physical and intuitive understanding on the working principle of DFIG at variable speed, constant voltage and frequency. In most real applications, the prime mover is replaced by a wind turbine, which coupled to the DFIG's rotor shaft via a gearbox and converts wind power directly into rotary mechanical power via its blades. The turbine shaft speed naturally varies with the wind speed V (m/s) acting at blade slip aria of the turbine at the installation site. So, depending on the rotational speed change, a DFIG can operate in three different modes as listed below [

9,

10];

Sub-synchronous mode

Super-synchronous mode

Synchronous mode

where,

is the synchronous angular speed and

fs is the mains or stator voltage constant frequency. As shown in

Figure 2, the stator terminal can be directly connected to

the grid (for grid-connected operation) or to external loads (for stand-alone operation) as required.

In real applications, the stator voltage and frequency are adjusted by the rotor flux via controlling the rotor current as the rotor speed changes. This task is normally performed by two power electronic converters connected back to back, as shown in

Figure 3. One of these converters works as an active front-end rectifier and is responsible for keeping the DC bus voltage constant, while the other works as a variable frequency PWM voltage source inverter (VSI) responsible for controlling the active and reactive power to be injected from the stator into the grid or an external load by regulating the rotor current [

11,

12]. However, in order to simplify the structure of simulation system and to understand the working principle of DFIG in the easiest way, the power converters are ignored in this study. Then the variable magnitude and frequency requirement to feed the rotor winding is met with a virtual ac voltage source as shown in

Figure 2, which has been created from the stator-rotor voltage relationship given in (1).

where

s is normalized slip and

θsl is the slip angle, both given in (2), (3) respectively,

k is the winding turns ratio (or the rotor-to-stator voltage ratio) if the rotor is at rest, i.e.,

. In a wind power system, the typical slip range of the DFIG is ±0.3. This means that the slip value can change from +0.3 sub-sync. to -0.3 super-sync at most. The slip angle and its normalized value can be calculated by (2) and (3), respectively [

9,

10].

Here, it should be noted that if the DFIG’s rotor is stay at stand-still, i.e.,

,

, and slip

s=1, then both rotor and stator voltage frequency will be same, i.e.

fr = fs. In this case, the rotor voltage magnitude is determined only by the winding turn ratio,

k. Thus, the voltage relationship given in (1) becomes

at

, and in this particular case a DFIG works like a transformer, which is unsuitable operation for the power production purpose. But, if the rotor is rotating at any speed, the voltage equation given in (1) is always valid and the relationship between the rotor-stator frequency is

fr = s.fs, and the relationship between active powers is

Pr = s.Ps. Therefore, it can be clearly seen that a DFIG allows bi-directional power flow through the rotor as the direction of the rotor current is reversed depending on whether the rotor speed is higher or lower than the synchronous speed. It can be understood that both stator and rotor can supply power to the grid in super-synchronous operation. To achieve this, a set of back-to-back power converters are needed to regulate the DFIG rotor current. In this context, there are several considerations that should be taken into account for a DFIG based WECS [

13,

14];

1. Initial excitation; The rotor has to be fed with adjustable ac current to create a magnetic field in air gap of the machine and induce generator voltage on the stator. The supply voltage can be obtained from utility grid for the grid connected operation. But for the stand-alone operation at the ruler area, there are several methods to fix this problem without requiring an external power supply as described in

Figure 3. One way is to use an energy-storage (small battery or super-capacitor) element with isolating diode in the DC link and the second way is to use the residual magnet in the core of the machine and with additional AC capacitor at the stator terminal, another solution can be fitted with a pilot generator on the rotor shaft feeding the excitation winding [

11].

2. Power imbalance; The power imbalance: The power delivered to grid is determined by the MPPT mechanism depending on wind speed at the wind farm for the grid connected operation, its limited with the generator rated power. But the imbalance between the captured wind power and the demanded power of the external load is one of the main challenges for stand-alone wind turbine systems. If the mechanical power received from the wind is greater than the power consumed by the load, then pitch angle controller is activated to adjust the pitch angle to ensure that the rotor speed is inside the allowable operating range. In the opposite case that the captured wind power is not sufficient for the connected load. The wind turbine tries compensating the power shortage by the energy stored in its inertia and supplying the load during a certain period of time or preventing excessive decrease of rotor speed with an appropriate load shedding. This must be considered in order to guarantee the system against total collapse and to cater a secure power supply to high priority loads. More detailed information about the design criteria, and requirements to start up and run the system, as well as the economic advantages of the DFIG based stand-alone WEGS can be found in [

2,

3,

9,

10].

3. Various Model of DFIG

As mentioned above, if the rotor windings are short-circuited, a DFIM can be considered to have the same structure and the same dynamic model as a three-phase squirrel-cage induction machine (SGIM). For the simplicity, it should be noted that the dynamic model equations of IMs are derived under several assumptions [

16]; The three-phase windings are star-connected, symmetrically balanced, and have sinusoidal distribution, the magnetic core of the machine is linear, magnetic saturation, skin effects of wires, and the iron losses are neglected. Under these assumptions, a general model as a compact set of nonlinear differential equations derived from the electromagnetic relationship between the stator and rotor windings will be used to describe the dynamics of both IMs (SGIM/DFIM). However, the equations of the three-phase IM model are usually complex because the state variables and inductances of each phase winding of the stator and rotor varies sinusoidally and are cross-coupled with each other. Therefore, based on the space vector theory, an equivalent space vector model equation defined on two orthogonal axes is preferred to represent a three-phase IM. Because the space vector theory simplifies the mathematical model of the IM, since it allows the transformation of the three-phase instantaneous state equations into equivalent two-phase space vector equations and eliminates the complexity of time-varying inductances. The derivation of an equivalent two-phase model of IMs and the formulation of phase and coordinate transformations using the well-known Clark and Park transformations can be found in detail in [

16,

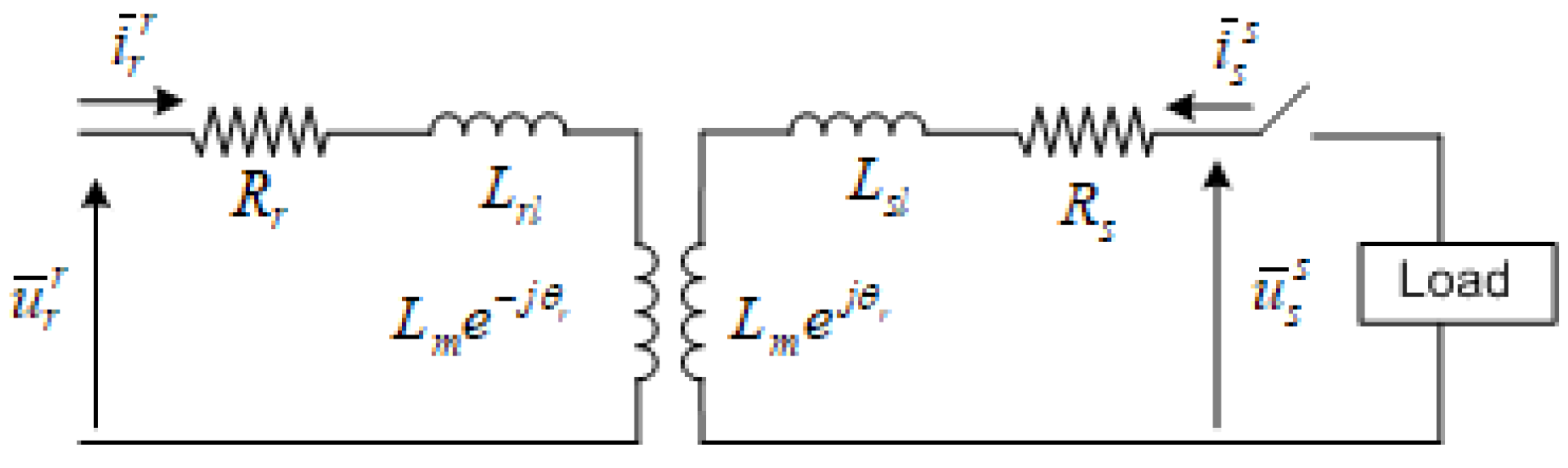

17]. Accordingly, each of the three-phase sinusoidal variables (i.e. voltages, currents and flux linkages) can be represented by a space vector and in this context, the space vector equivalent circuit of a DFIM can be introduced as shown in

Figure 4.

From

Figure 4, the basic dynamic model equations of a DFIG can be derived based on the space voltage vector of the stator and rotor given in (4) and (5), which are defined on the natural (separated) frame axis (

sr-axis) and valid for both SGIM/DFIM.

where it is assumed that the rotor parameters are reduced to the stator, and flux linkages are defined as follows:

where

: stator and rotor voltage space vectors (V)

: stator and rotor flux space vectors (Wb)

: stator and rotor current space vectors (A)

Ls, Lr : stator and rotor inductances (H)

Rs, Rr : stator and rotor winding resistances (Ω)

: rotating synchronous speed (rad/s)

: rotor electrical angular speed (rad/s)

: angle between stator and rotor winding axes

where superscripts “s” and “r” denote the variables are referred to respective reference frames with s is the stationary frame fixed to the stator axis and r is the rotating frame fixed the rotor, respectively. The indices s and r indicates the stator and rotor variables, respectively. The is called as rotary unit vector (i.e. shift operator) used for the coordinate transformation between the reference coordinate frames, and is angle between the stator and rotor winding axes. Each of the stator and rotor electrical variables, i.e. voltage, current and flux linkage, presented as complex space vector, can be decomposed into real and imaginary parts in the respective reference frame: i.e. for the stator variables and for the rotor variables .

Remark: Some authors oppose the complex representation of space vectors, i.e.

and insist that they should be represented by two orthogonal components such as

[

18]. However, it is well-known that if representation of

is used for the orthogonal space vector model and

is used for the complex space vector model, both symbolic notations yield the same dynamic model. Therefore, it does not matter which notation is used to represent the model.

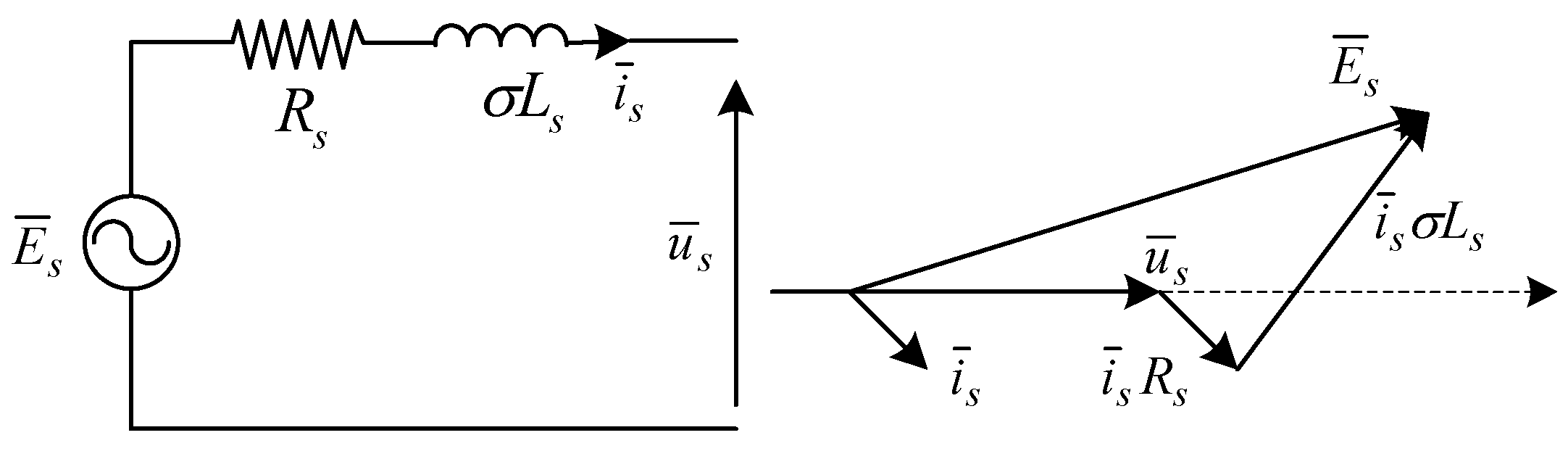

Considering above assumption, two version of the stator voltage space vector equation (4) can be rewritten with help of and (6);

Both equations above consist of two parts; the internal voltage drop,

and emf,

which is induced by the rotor flux [

1]. Using equation (8) a simplified equivalent circuit and phasor diagram of DFIG stator can be drawn similar to that of a synchronous generator as shown in

Figure 5. Under the no-load operation, the stator current and hence the internal voltage drop is zero and thus the stator terminal voltage becomes equal to the induced stator voltage, i.e.

, which is given as the function of rotor current and mutual inductance by

For the full-state model of a DFIG/M, its mechanical part must also be taken into account, which is given in (10)

where,

is the mechanical torque acting on the rotor shaft which can be an external mechanical load in case of motor mode operation, or it can be an input provided by a wind turbine in case of generation mode in WEGS,

ɷm is the rotor mechanical angular speed,

p is pole pair of the machine,

is the electromagnetic torque produced in the air gap of the machine that can be defined in several alternative ways; i.e. it can be defined as function of space vectors of the stator current and rotor flux i.e.

where (

*) denotes the complex conjugate), the other torque expressions with different state variables are explained well in [

15]. It should be noted here that the angular velocity or mechanical torque transmitted from the wind turbine to the DFIM rotor shaft can be considered as optional input to the system’s mechanical part when it is operating in generator mode.

The separated frame model equations in (4)-(6) can be redefined by considering different state variables and alternative reference frame axes. To achieve this, the stator and rotor voltage space vectors given in (4), (5) are multiplied by the phase shift operator depending on the selected reference frame angle. For example, if the voltage equation (4) is multiplied by

then it will be represented in the rotor frame (

DQ-axis), and if (5) is multiplied by

it will be presented in the stationary frame (

αβ-axis). Similarly, it is also possible to represent the same equations (4) and (5) on an arbitrarily chosen general rotating reference frame (

xy-axis). For this end, the stator voltage space vector is multiplied by

and the rotor voltage space vector is multiplied by

. Here

is angle between the stationary frame (

αβ-axis) and an arbitrary chosen common rotating reference frame (

xy-axis). The above multiplication results in the derivation of the general frame model equations defined on the

xy-axis.

where subscript “

g” briefly denotes

xy-axis and the relationship between the flux and current variables are given as

Depending on the specific analysis intended or targeted, the model equations (11) and (12) can be redefined with the aid of (13) and expressed for optional state variables; i.e. the stator and rotor currents

stator and rotor fluxes

stator current and rotor flux

or stator flux and rotor current

For example, a model with the flux state variables

can be called as “flux model” and obtained as:

This is the simplest model of IM/DFIM and can be defined for alternative state variables using equation (13) and i.e. if (14) and (15) are rearranged for the stator and rotor currents space vector

, it might be called as “current model” and is derived as:

Considering the orthogonal components of the state variables, both the flux model and current model can be expressed in state-space form. For example, from equations (16) and (17), the state-space current model defined on the

xy-axis can be obtained as given in (18), where both stator and rotor voltages, and the external mechanical torque

tL (or optionally the rotor mechanical angular speed,

are considered as the inputs of the DFIG system. Here it can be seen that rotor electrical speed

is one of the state variables of the system and it exits in the system matrix A. This is the main reason why DFIM is a non-linear system [

9].

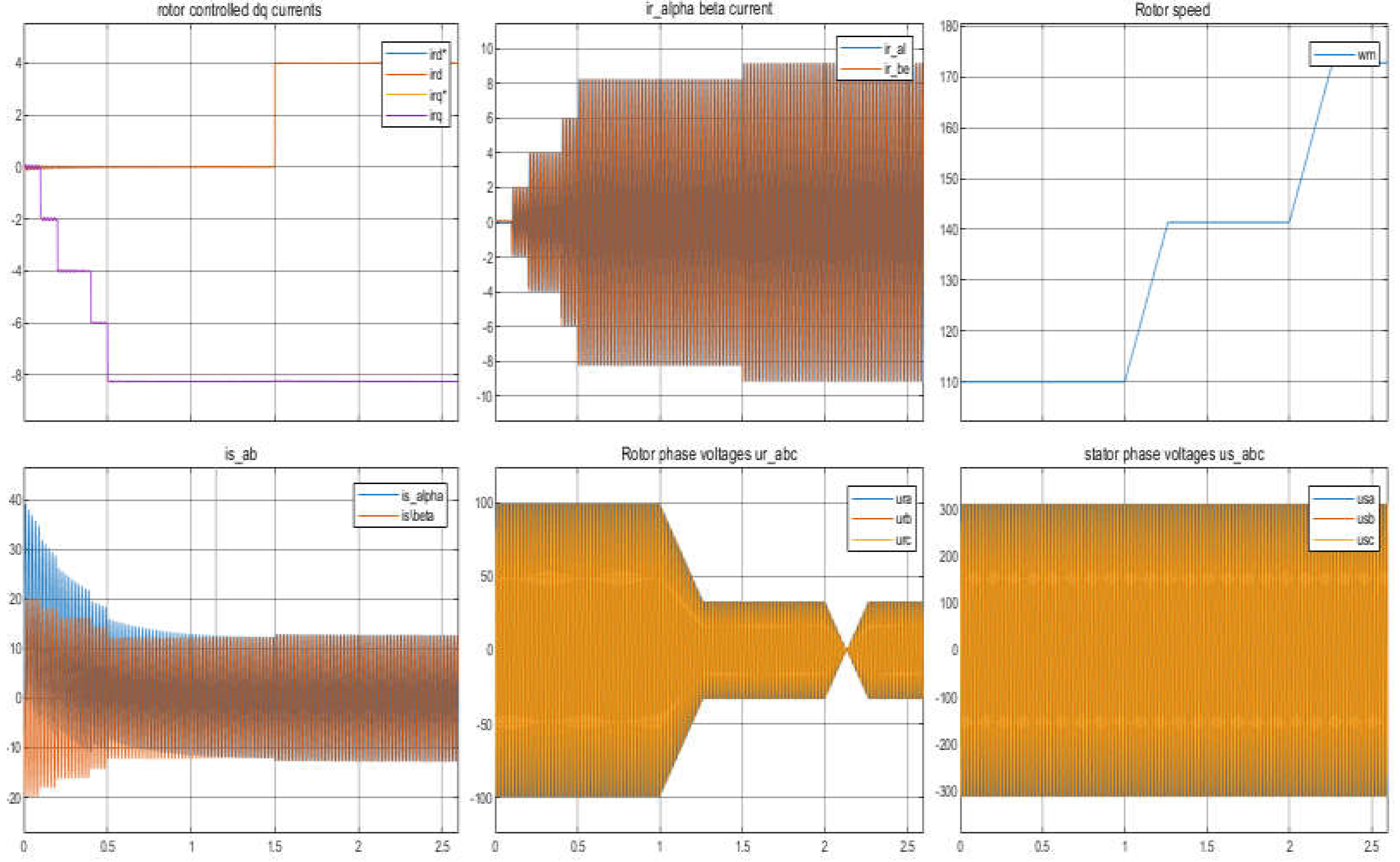

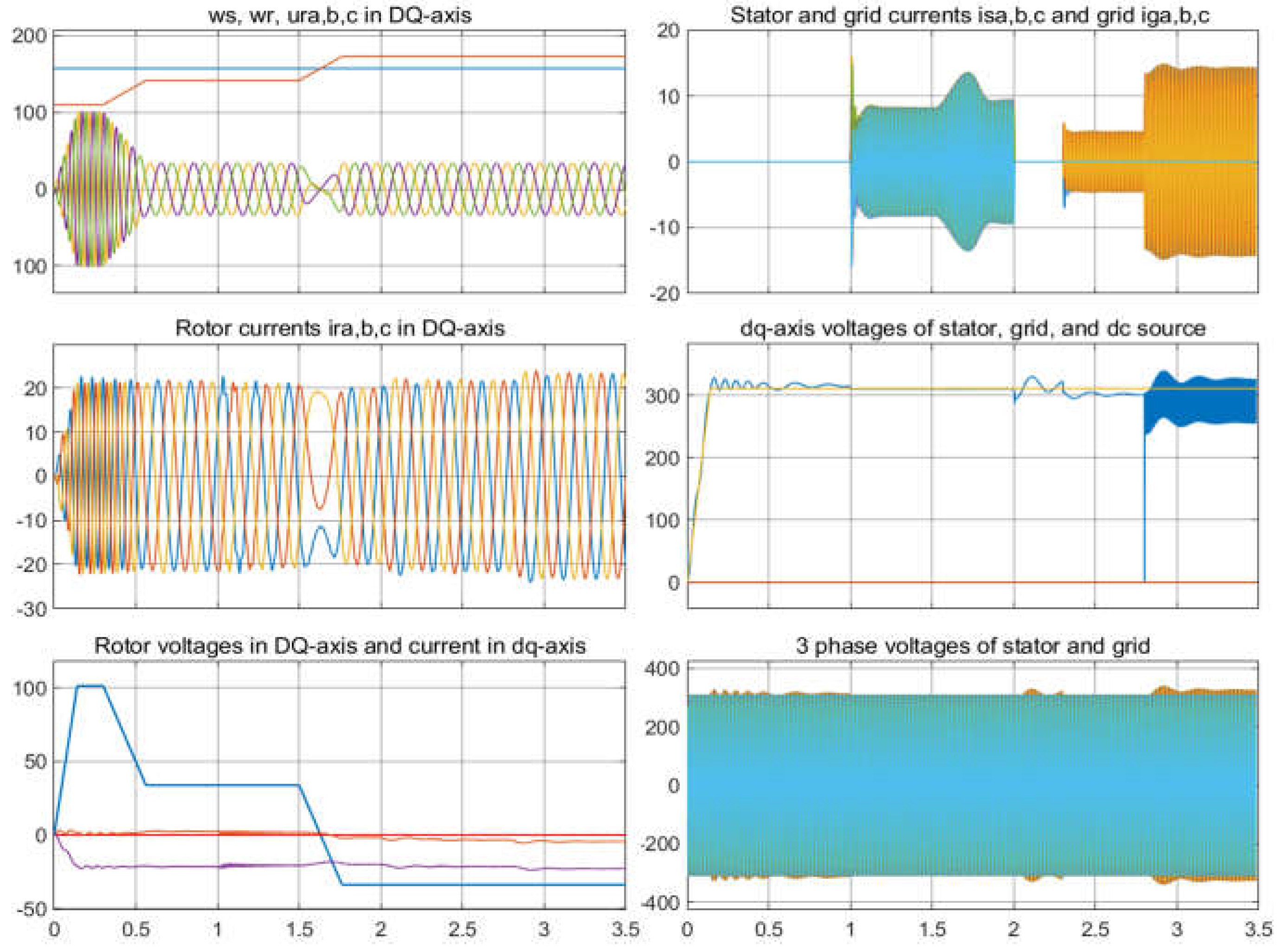

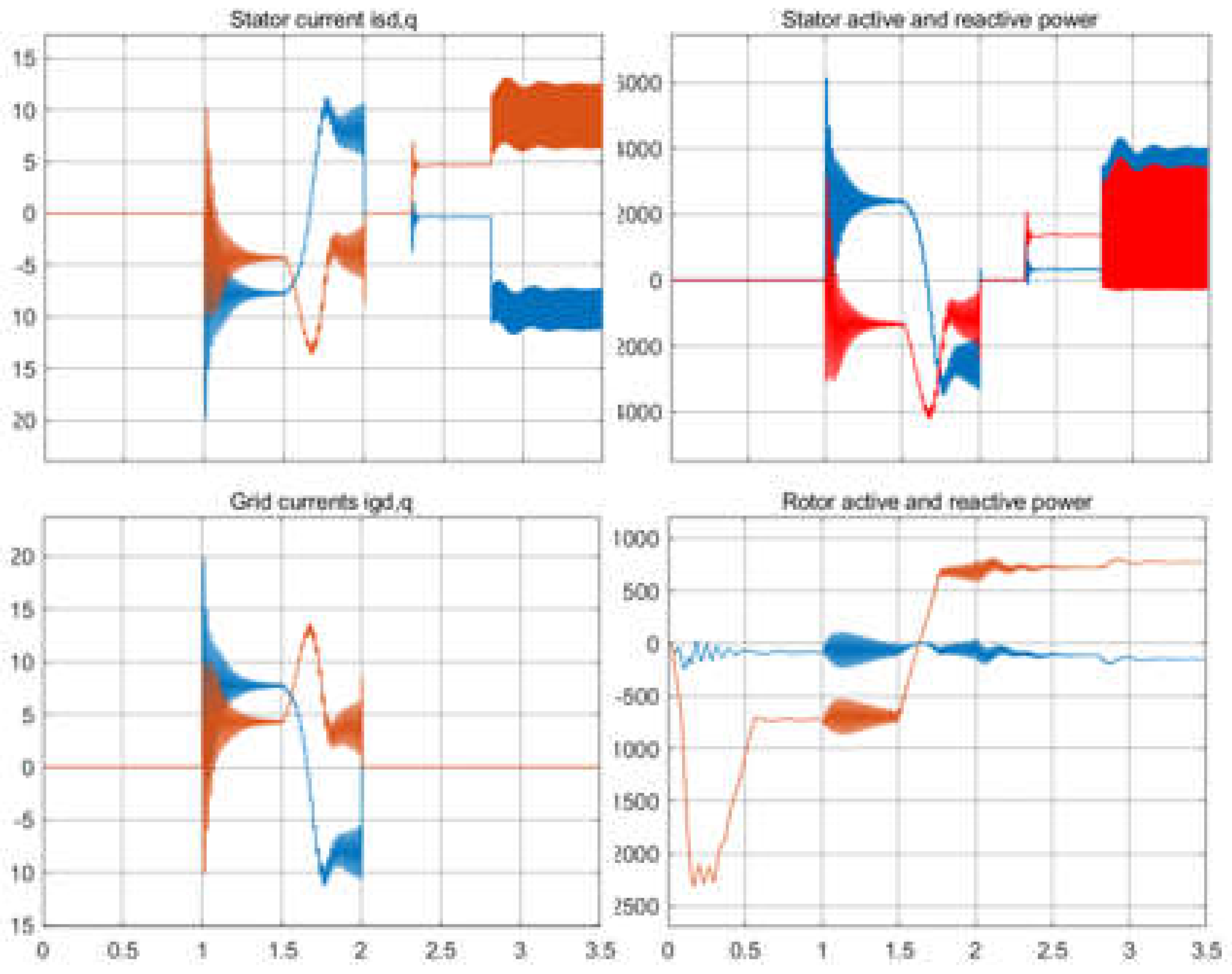

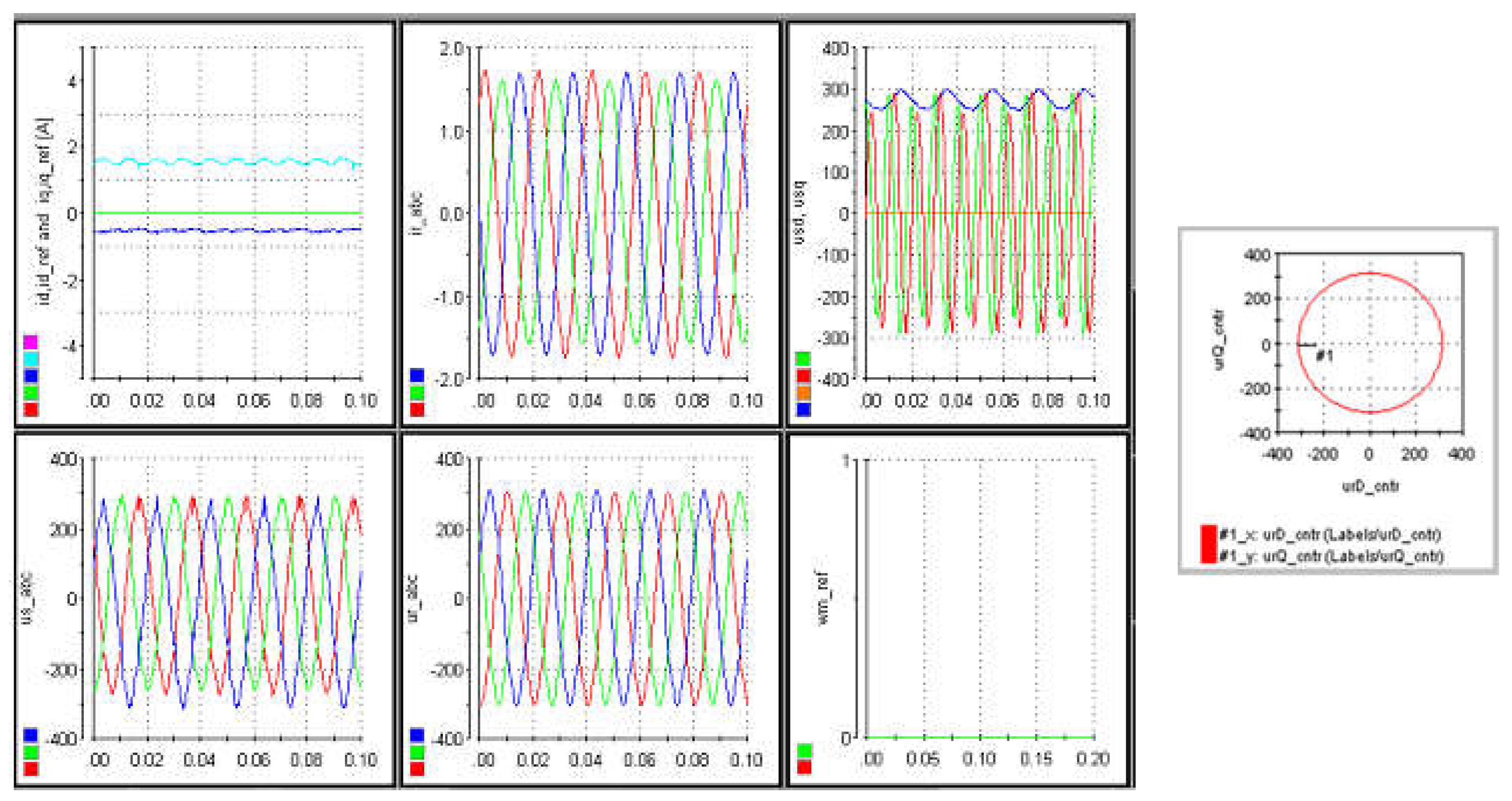

The flux model equations (14), (15) with (10) and the current model (16), (17) with (10) both can represent the well-known 5th-order nonlinear model equations of an induction machine. These models are valid for both the SGIM and DFIM/DFIG. A version of these models defined in dq-axis are generally used in many research studies to simulate the controlled operation of grid connected DFIG with back-to-back converters under different operation conditions. In these applications, active and reactive power are injected into the grid by regulating the rotor current through a pulse width modulated voltage source inverter (PWM-VSI) with power and current feedback control depending on the input references determined by external (active and reactive power) controllers. In this case, an MPPT controller generates an active power reference based on wind speed, while the reactive power reference is determined by the power quality demands. Regarding the grid connected operation of DFIG, there are many research studies to solve different operational problems and application of different control strategies such as direct torque and direct power control under normal and abnormal operating conditions, and even more, there are various research studies focusing on different existing problems, so these latter issues are ignored in this paper. However, a basic simulation test on the control of rotor current is presented in the following section.

On the other hand, it has been reported about 5

th order models (flux and current based models with the mechanical equation) that they lead to a complex system structure and are not suitable for analysis studies in operations under transient conditions for large-scale wind energy applications, so it is necessary to develop a simplified DFIG model to study on such systems, an example of simplified model presented in [

19]. Different approaches proposed for the simplified DFIG model, aimed at shortening the computation time and simulating large-scale wind power applications, and analyzing challenging problems occurring in transient, normal and abnormal operations can be found in [

20,

21,

22,

23].

3.1. Various Coordinate Frame Models

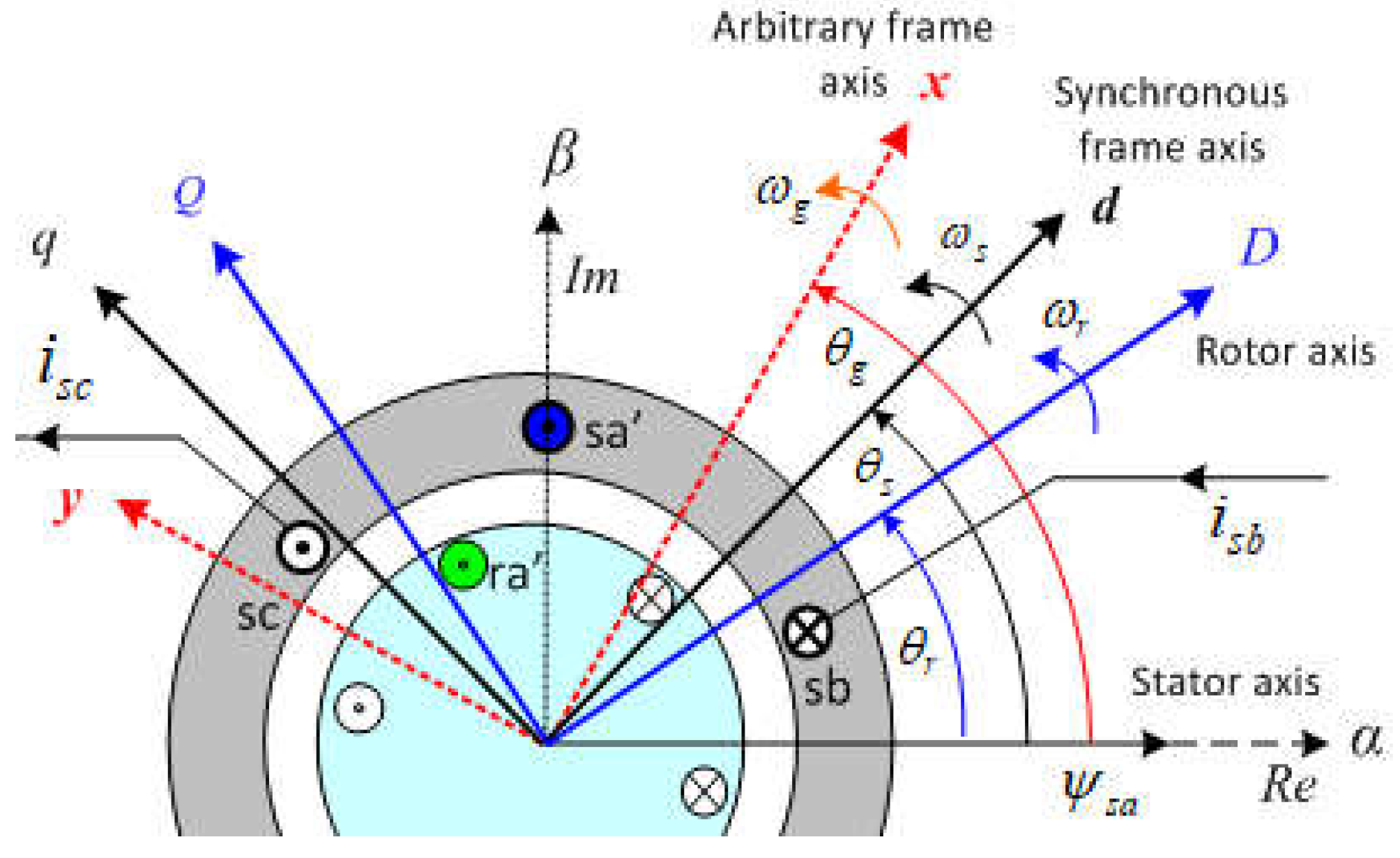

As mentioned earlier, there are several alternative model equations defined in various coordinate frames shown in

Figure 5. and can be obtained from (18) by appropriate coordinate transformations. An easy way to obtain these models defined in various reference frames is to replace the angular velocity

ɷg in the model equations [

16,

17] with any of the ones listed below.

ɷg = ɷg for the arbitrary selected rotating frame (xy-axis)

ɷg= ɷs for the synchronously rotating frame (dq-axis)

ɷg = ɷr for the rotating frame fixed to rotor (DQ-axis)

ɷg = 0 for the stationery frame fixed to stator (αβ-axis)

However, it is often common for new learners to be confused in understanding and distinguishing between these various models, so an easy and accurate explanation of the relationship between these models can clarify the contradiction. For example, if the arbitrary selected angular speed is taken as ɷg=0 in (11) and ɷg=ɷr in (12), this general frame model equations (11), (12) will return to the same with the separate frame model equations in (4) and (5). Another example, if we take ɷg=0 in (11) and (12) or alternatively in the rows of (18), the general frame model will be transformed into the stationery frame (αβ-axis) model. Similarly, it is possible to derive a model defined in any frame axis from equations of the general reference frame model in (11), (12).

Figure 6.

Coordinate frames of DFIG/DFIM.

Figure 6.

Coordinate frames of DFIG/DFIM.

For example, replacing ɷs with ɷg in (11) and (12) will transform the general frame model into another model defined in the synchronously rotating frame (dq-axis), or replacing ɷs with ɷr will transform the same model into another model defined in the rotating frame with rotor (DQ-axis). However, what is important here is that the voltages supplied to the stator and rotor are compatible with the reference frame in which the model is defined and that the appropriate coordinate transformation must be done for the other state variables.

3.1.1. Grid Connected Model

As mentioned above, the stator and rotor voltages are defined as (double voltage) inputs in the flux and current based models which are appropriate for the analysis of grid connected DFIG operation and hence these models can be called as “grid connected model” of DFIG. For the proposed grid-connected simulation model of DFIG, the flux model given in (13) and (14) is used, which can be rewritten with its orthogonal components as:

In the simulation, instead of the flux-based model given above, the current-based model in (18) can also be used as an alternative option.

3.1.2. Steady-State Model

Flux and current models can also be used for the analysis and simulation of the steady-state behavior of the DFIG when the derivative of the state variables is equal to zero. In this context, many comprehensive studies on steady-state analysis for DFIG-WEGS have been conducted in the literature [

9,

10,

20] so this topic is not the focus of this study.

3.1.3. Motor Model (DFIM)

As it is stated before a DFIG can be run as an IM. It should be noted here that both flux and current models can also be used to simulate motor operation of a DFIM by short-circuiting one of the winding ends of the stator or rotor and then applying an AC voltage to the other winding as is done in real applications. This can be easily accomplished in simulation, for example, by applying zero volts (or short-circuiting) to the rotor terminals and then applying nominal voltage or less to the stator.

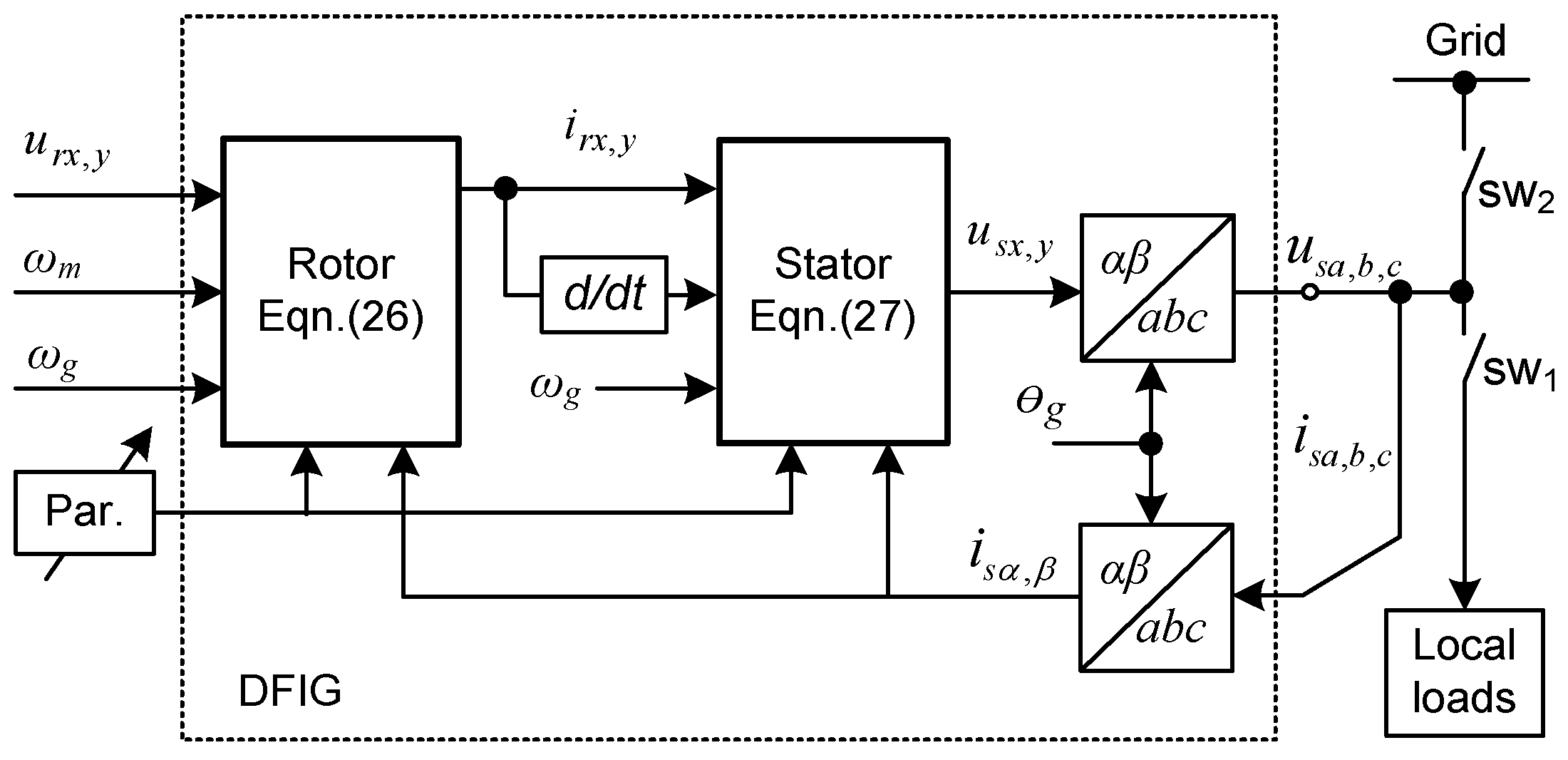

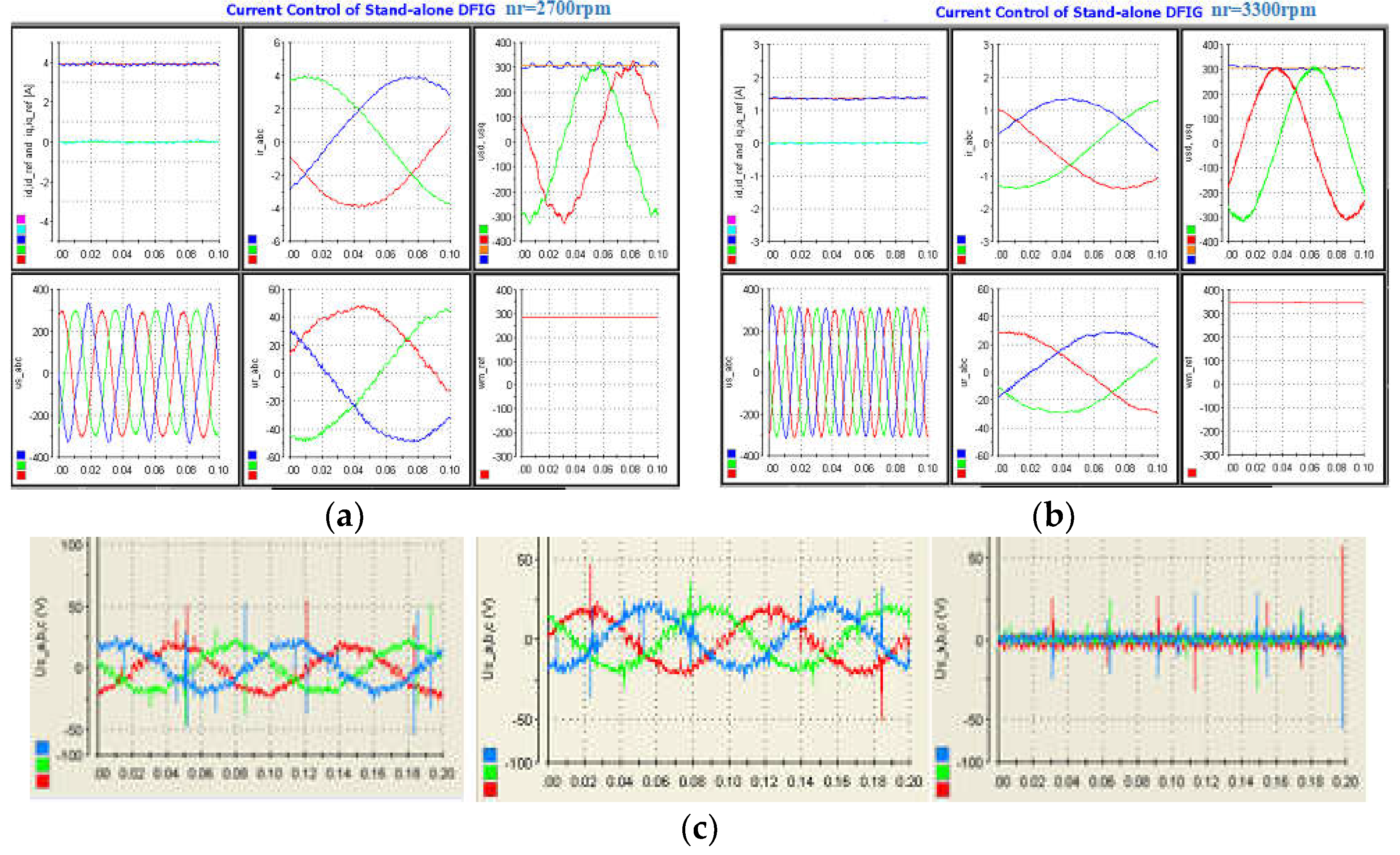

3.2. Stand-Alone Models

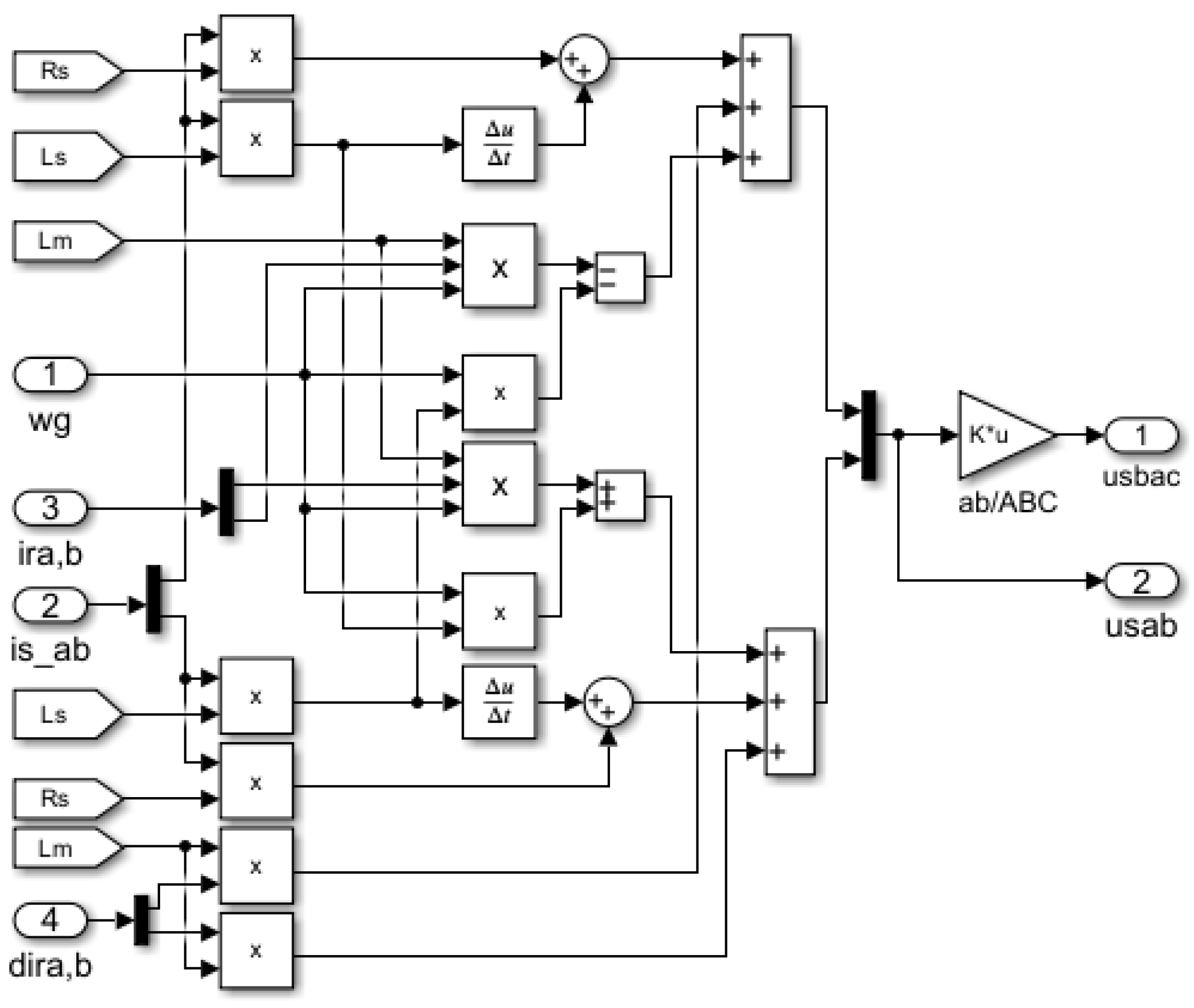

The current model in (18) and the flux model in (19) and (20) are not suitable for simulation a stand-alone operated DFIG since they both take the stator and rotor voltages as inputs to the system. Therefore, this paper particularly focuses on deriving a simple simulation model needed for stand-alone DFIG which provides us a better grasping of the fundamentals of DFIG and also facilitates the analysis of its dynamic behavior under different conditions. It should be noted here that the difference between a stand-alone and grid-connected model is that the stator voltage in a grid-connected DFIG is supplied from the grid, but a stand-alone DFIG generates voltage at the stator terminal as its output and supplies to external loads connected to the stator terminal.

Thus, the equation (18) can be extended and adapted for the stand-alone model based on some reasonable assumptions [Abad]. First, it is assumed that only a resistive load is connected to the stator, and secondly, in addition to resistive load, the stator terminal is also equipped with a filtering capacitor. However, with only the external resistive load

R0, the stator voltage will be the same as the voltage drop across the external load connected to the stator, resulting in

where the stator current is the same as the load current,

Replacing the stator voltage in (18) with the auxiliary equation in (21), a stand-alone DFIG model can be derived in the state space form [

9,

10,

11]:

where the stator and rotor current components are state variables, the stator voltage is eliminated and the rotor voltage become only the input of the system. The stator current also can be considered as the disturbance of the system. Considering here that the stator voltage and current are linearly dependent for resistive loads, equation (18) can be further expanded and a different model can be obtained having the stator voltage and rotor current as state variables.

Alternatively, with the second assumption given above, since the stator is connected to resistive load and also has a filtering capacitor

Cf, an additional equation for the stator voltage can be obtained as follows:

where

indicates resistive load current. With the help of (22) the stator voltage, which is identical with capacitor voltage (

) can be presented as one of the state variables in the system and an alternative state-space model of the stand-alone DFIG can be obtained as given in (25). More details about models of (22), (23) and (25) can be found in [

9,

11].

Discussion: It can be said that pure resistive load application is unrealistic and rarely realized in a stand-alone DFIG-WEGS, it is insufficient to analyze the behavior of DFIG in case of different load type and size, and also the resistive load and filtering capacitor complicate the system model.

Considering a stand-alone DFIG, the stator terminal voltage is the same as the load voltage and will vary depending on the load current. Therefore, including the dynamics of various sizes and types of loads makes the dynamic model of the system more complicated, thus making it difficult to obtain a generalized model. Based on this difficulty, a more realistic modeling approach is needed for the analysis of stand-alone DFIG under various operating conditions.