1. Introduction

Aeromonas bacteria are ubiquitous, however, they are mainly found in aquatic environments. This type of bacteria causes various infections in humans. They have been found associated with clinical pictures of gastroenteritis and mild infections in various organs and tissues, or severe infections such as septicemia [

2,

3,

15,

22]. Over time, it has been thought that these bacteria were opportunistic, however, there is evidence of severe septicemia in immunocompromised patients caused by virulent strains of this genus [

15]. An important factor that favors this type of bacteria is its adaptation, diverse metabolic capacity, among others; allowing Aeromonas to persist in almost any environment and to be transmitted by various routes and vectors [

9,

10,

16,

25]. The Aeromonas species of clinical importance and most frequently associated with human diseases are A. hydrophila (14.5%), A. caviae (37.6%), A. veronii bv. sobria (27.2%) and A. dhakensis (16.5%), which represent around 96% of cases of gastroenteritis [

11,

29]. There is an increase in antibiotic resistance, which is why the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified bacteria such as Aeromonas on a priority list with the purpose of developing and researching new antibiotics or alternatives to control it, according to this classification Aeromonas are in priority 1 or critical, [

19,

20]. Therefore, it is important to study new alternatives for the control of the Aeromonas genus. An alternative for its control is the potential use of predatory bacteria, which has attracted attention due to its ability to prey on a wide range of prey, making them a viable alternative [

1,

4,

17,

18,

24]. It is important to continue isolating and characterizing predatory bacteria with the potential to control these highly virulent microorganisms. In this study, the phenotypic and molecular characterization of predatory bacteria (Bdellovibrio and similar organisms, BALOs) allowed us to understand the capabilities of the isolates with the greatest potential to attack Aeromonas species of clinical and environmental origin.

2. Materials and Methods

Sampling and isolation of Bdellovibrio: Bacteria of the Aeromonas genus of clinical and environmental importance from the collection of pathogenic bacteria of the Genomic Biotechnology Laboratory of the Genomic Biotechnology Center of the National Polytechnic Institute, located at Blvd. del Maestro S/N, Esq. Elías Piña, Col. Narciso Mendoza, CP 88710, Cd. Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, were used. Salmonella enterica was used as prey to isolate Bdellovibrio. Each prey was inoculated in Petri dishes containing Luria Bertani agar and incubated at 37 °C for 18-24 h, then a colony was inoculated in 20 ml of LB broth in 50 ml conical Falcon tubes, incubated at 37 °C for 18-24 h at 200 rpm (culture stand). Several isolates of Bdellovibrio were obtained from soil, water and feces samples from mammalian animals from different locations in Mexico, when confronted in co-culture with the prey, Salmonella enterica. 20 g of soil and feces samples were weighed, and 20 ml for water, each separately in 250 ml Elrenmeyer flasks, and placed in 50 ml of 25 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.4 in the case of solid samples, and for water samples 30 ml of 25 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.4 were added, they were left to incubate at 29 °C for 1 h at 200 rpm, subsequently, the samples with organic particles were filtered with coarse mesh filters, then starting from the culture feet (S. enterica) 100 µl were taken and inoculated in 20 ml of LB broth and incubated at 37 °C for 18-24 h at 200 rpm. After this time, they were centrifuged at 5 °C for 20 min at 3,500 rpm, the supernatant was discarded and 25 ml of 25 mM HEPES pH 7.4 were added to each pellet. Two pellets were placed for each sample. The prey pellets, S. enterica, were placed for different samples. Finally, each 250 ml Erlenmeyer flask was shaken vigorously to homogenize the prey pellets and the sample in the flask, leaving a final volume of approximately 100 ml. The flasks were incubated at 29 °C for 7-10 days with constant shaking at 200 rpm until cell lysis of the prey was observed (visualization of cellular debris at the bottom of the flask) following the protocol described by Jurkevitch [

13].

2.1. PCR Identification Using the 16S rRNA Gene Specific for Bdellovibrio and BALOs

For identification of Bdellovibrio in the samples, 1 ml of coculture was placed in a sterile 1.5 ml microtube. It was incubated in a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Germany) at 95 °C for 10 min (heat lysis), then placed on ice for 5 min and centrifuged at 5 °C for 5 min at 14,000 rpm; the supernatant was transferred to a new sterile microtube and the gDNA was used for PCR reactions. Next, a PCR mixture was prepared for amplification with Bdellovibrio-specific oligonucleotides of the 16S rRNA gene, which contains: 13.25 μl of milli-Q water, 5 μl of 5X MyTaq

® buffer (final 1X), 0.25 μl of 50 mM MgCl2 (final 1.5 mM), 0.25 μl of 10 mM dNTPs (final 0.2 mM), 0.5 μl of 5 µM Forward oligonucleotide (final 0.1 µM), 0.5 μl of 5 µM Reverse oligonucleotide (final 0.1 µM), 0.25 μl of 5 U/µl MyTaq

® Taq Polymerase (final 0.05 U/µl) and 5 μl of gDNA. The conditions for the thermocycler were as follows: initial 94 °C for 4 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, Tm °C (Tm of the Forward and Reverse oligonucleotide pair of the 16S rRNA gene specific for Bdellovibrio) [

13], for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min; 72 °C for 10 min and final 8 °C for 5 min. Once the PCR was performed, the products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel, run for 60 min at 80 V, using 0.5X TAE as buffer. The loading buffer mixture was placed in each well of the gel with 5 μl of the PCR product. The agarose gel was visualized in the Kodak

® photodocumenter with a Gel Logic 112 camera using the Kodak

® dS 1D v. 1 bioinformatics program. 3.0.2.

2.2. Sequencing Reaction Using the 16S rRNA Gene Specific for Bdellovibrio

The PCR product was purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions ExoSAP-IT (#78200, USB, USA). The sequencing reaction was carried out with the BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit. The sequencing reactions were performed on the ABI® 3130 Genetic Analyzer from Applied Biosystems. The files in .ab1 format were cleaned using MEGA11 v11.0.13. The search for homologous sequences was performed in BLAST of the NCBI database to determine the identity of each predatory bacterium that was used for predation efficiency. The phylogenetic tree was generated in MEGA11 v11.0.13 using the Maximum Likelihood method.

2.3. Determination of Predation Efficiency of Bdellovibrio Species

The determination of predation efficiency was measured by spectrophotometry by reading the optical density of the ten predators isolated in co-culture with each Aeromonas of clinical and environmental origin. The co-cultures were maintained at 29 oC, 1 ml of each co-culture was deposited in plastic cells (1.5 ml semi-micro PS cell, #KART1938, KARTELL, USA), the OD reading was measured in the visible light spectrum at 600 nm (Spectrometer, Cintra 10e, GBC). The first reading was taken at 0 h, and the following readings at 5, 8.5, 12.5, 16.5, 20.5, 24.5, 28.5, 32.5, 36.5, 41, 46, 48.5, 52.5, 57, 60.5, 64.5 and 68.5 h.

3. Results

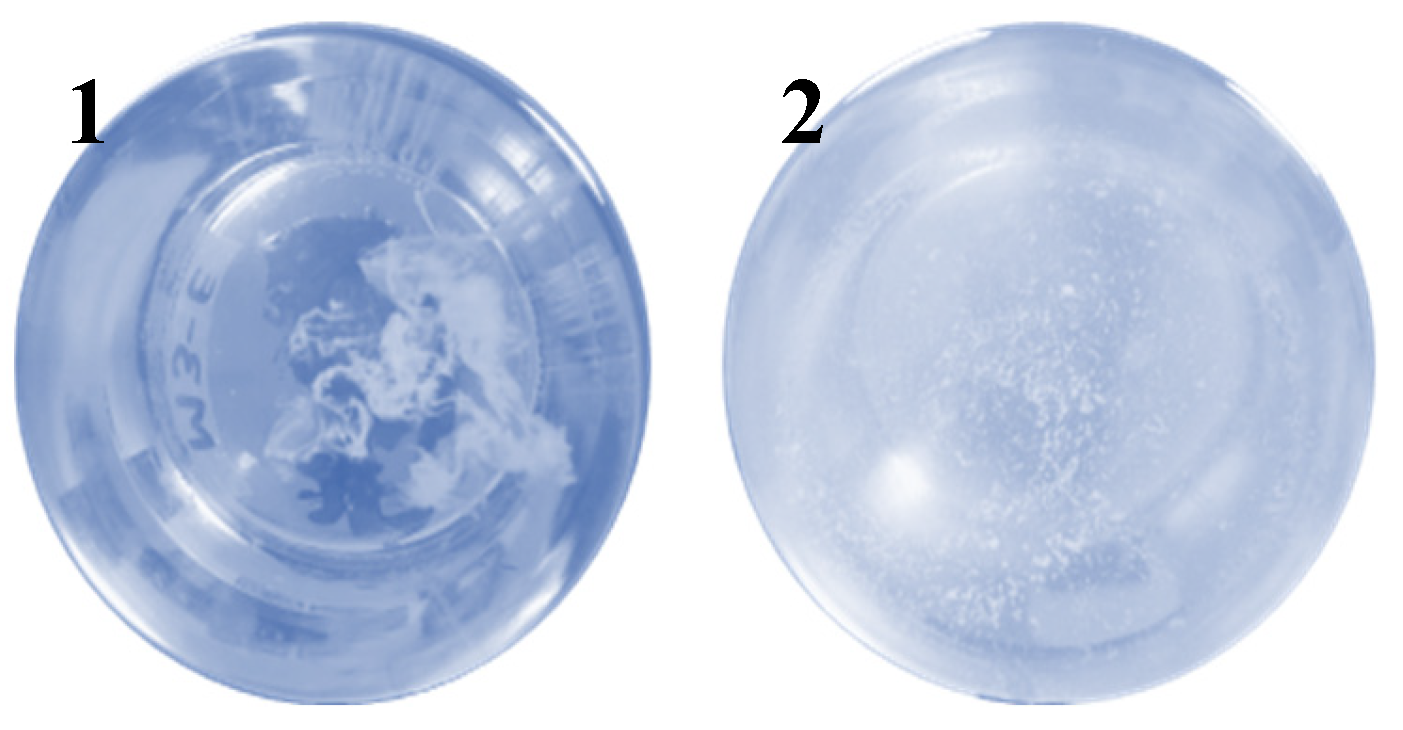

Forty-one Bdellovibrio isolates were obtained from water, soil and feces samples from mammals in the states of Tamaulipas, Durango, Puebla and Tlaxcala (Mexico), and the formation of cellular debris was observed (

Figure 1).

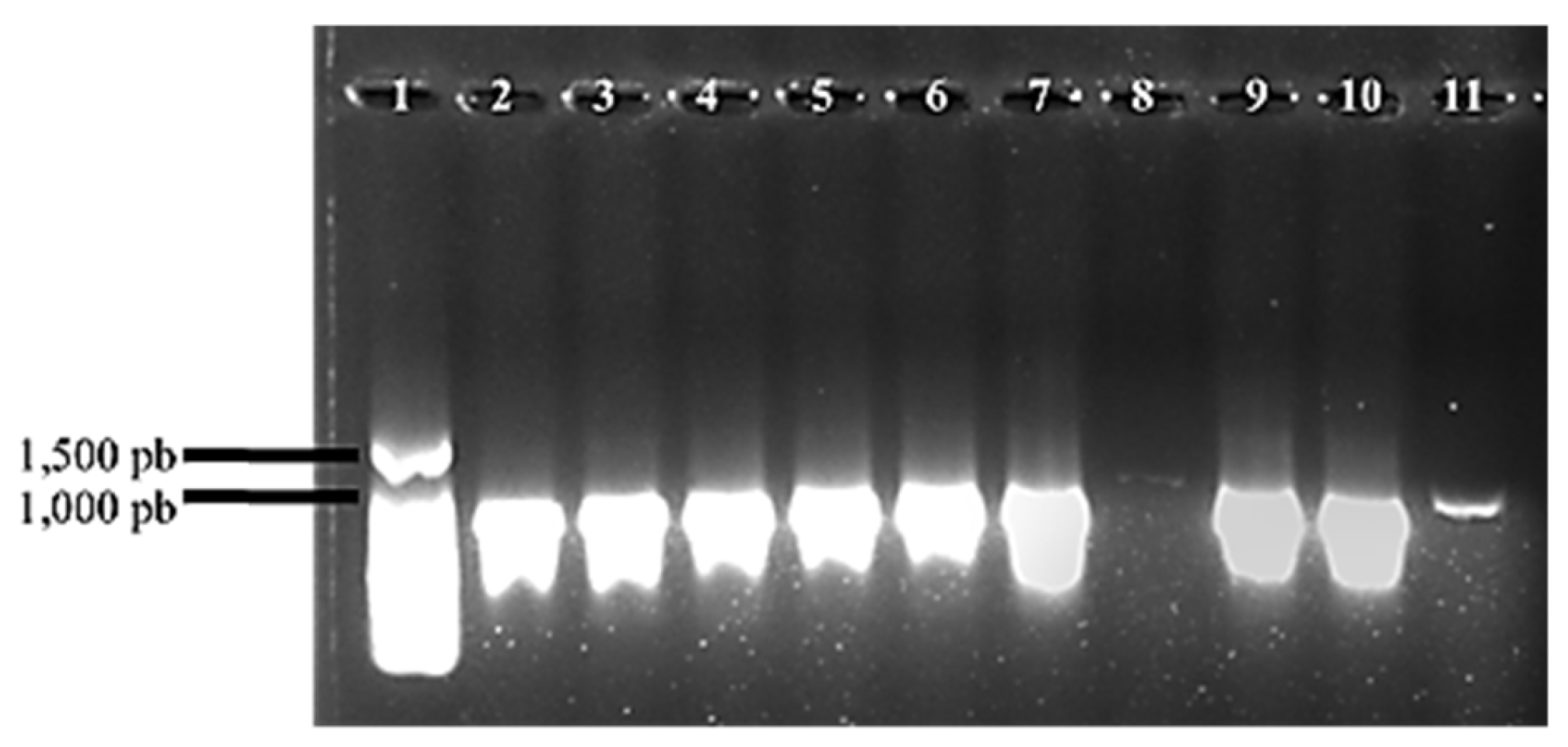

Some isolates were identified by PCR using Bdellovibrio-specific oligonucleotides (

Figure 2).

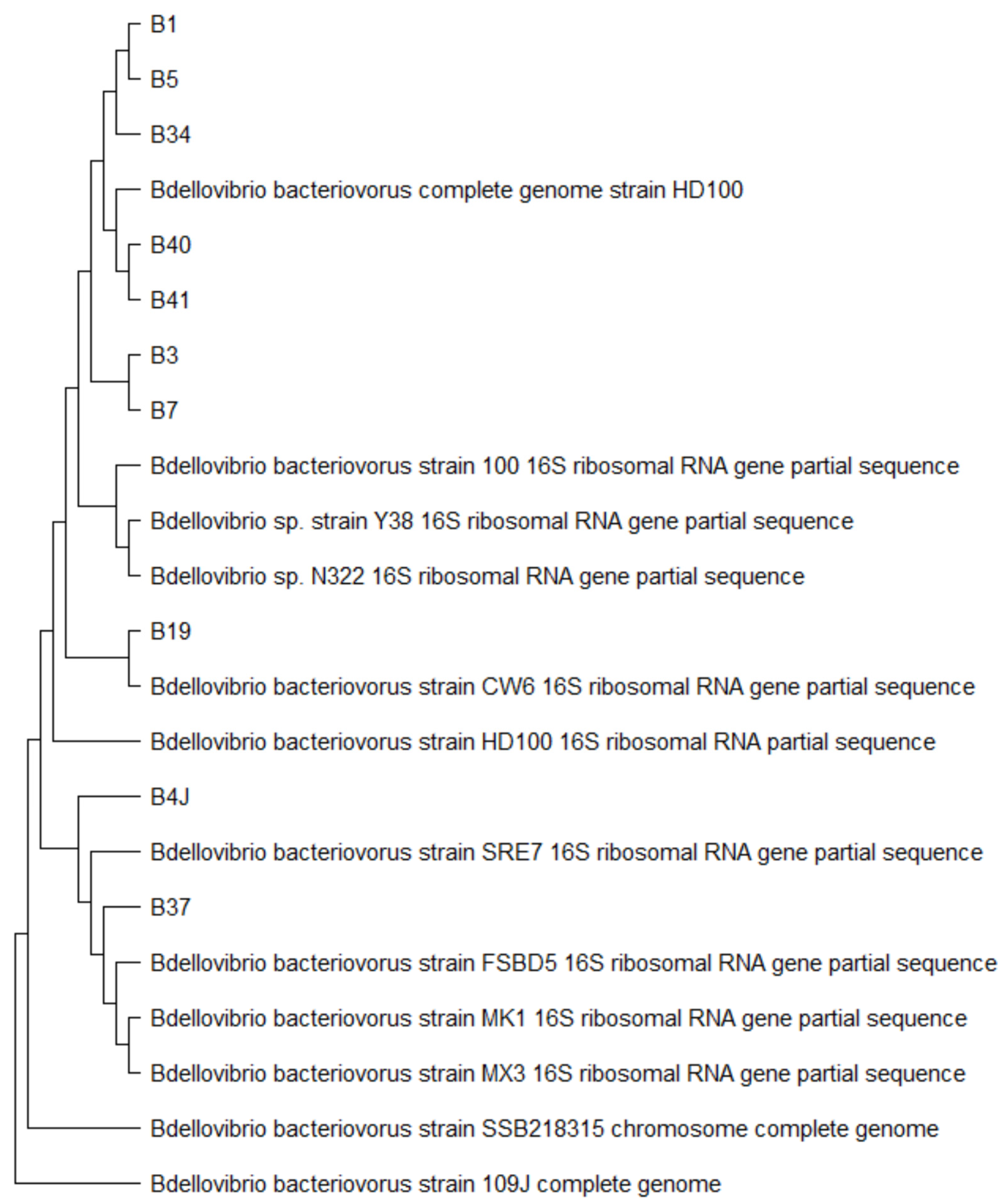

From the sequencing reactions run on the Applied Biosystems ABI

® 3130 Genetic Analyzer with BigDye

® XTerminatorTM Purification Kit (#4376486, Applied Biosystems, USA), files were obtained in .ab1 format and analyzed using the MEGA11 v11.0.13 program. A search for homologous sequences was performed with the files in FASTA format using BLAST in the NCBI database to determine the identity of each predatory bacterium. The evolutionary relationships between the different Bdellovibrio isolates are observed in the phylogenetic tree constructed with the sequences that showed the highest percentage of identity in the NCBI database (

Figure 3).

In predation efficiency, initial concentrations of prey and BALOs were 0.301 and 0.142 A, respectively. B1 initiated predation at 5 h on 16.66% of prey (A8, A12); B3 on 41.66% (A5, A9, A10, A11, A12); B5 (A2, A5, A6, A9, A10, A12), B37 (A2, A4, A5, A8, A11, A12), B41 (A1, A4, A6, A7, A9, A10), and B4J (A2, A4, A5, A7, A10, A12) on 50%; B34 on 58.33% (A2, A4, A5, A6, A8, A10, A11); B7 (A2, A3, A5, A6, A7, A9, A10, A11, A12) and B40 (A2, A3, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9, A11, A12) in 75%; and B19 in 83.33% (A1, A2, A3, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9, A10 and A11). BALO B19 showed the highest efficacy by initiating predation time at 5 h in 83.33% of the prey (A1, A2, A3, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9, A10 and A11), whereas, B1 had the lowest predation efficacy by initiating predation at 5 h in only 16.66% of Aeromonas (A8, A12) and initiating predation at 12.5 h in 41.66% of the prey (A1, A2, A5, A7, A9). These results reveal that predatory bacteria have very different predation characteristics depending on the specific prey strains (Aeromonas species), although the prey belong to the same genus.

4. Discussion

Predation was found in cocultures made from the three types of samples available for the study, which correspond to soil, water and feces of mammalian animals, confirming that predatory bacteria are ubiquitous and can be found in various ecological niches as described by other authors [

8,

21,

28].

In 2017, [

13], they evaluated the effect of predatory bacteria on the gastrointestinal tract in mice, infecting the mice with Klebsiella pneumoniae, no signs of damage were shown in the mice by intranasal inoculation of the predatory bacteria and after 48 hours, the predatory bacteria were viable in the mouse feces [

26,

27]. (Several studies have stated that Bdellovibrio species have a wide prey range for Gram-negative bacteria, and that they have the ability to prey on them in an average of 18 to 24 hours [

1,

5,

6,

7,

12,

23].

In this study, predatory bacteria were isolated that showed the ability to prey on bacteria of clinical interest used for their isolation and purification, Salmonella enterica and Klebsiella pneumoniae. In addition, when confronted with Aeromonas species, predation was observed after 5 h. The Peredibacter genus was found in soil sample M7 from the Tepetitla River, Tlaxcala, Mexico, but it was not purified, so it can be determined that, like several predatory bacteria, Peredibacter is a ubiquitous bacterium. However, only the phenotypic characteristics of the isolate have been determined with the prey used for its isolation and purification: S. enterica. Peredibacter starrii, which has only been isolated from soil samples at a temperature of 35 °C, is suggested to have a similar lifestyle to Bdellovibrio and a wide prey range [

12].

The genus Micavibrio was found in soil sample M34 from a garden in Cd. Victoria, Tamaulipas, Mexico, but it could not be purified. This isolate showed predation with the prey used for its isolation and purification: S. enterica. The ability of Micavibrio aeruginosavorus to prey on pathogens of clinical interest such as P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae has been shown in different studies. Likewise, an increase in the prey range of this predator has been seen, since Dashiff et al. In 2011, they showed that it was able to hunt and reduce 57 of the 89 bacteria examined [

6,

14].

5. Conclusions

Of a total of 41 samples, 36 were soil, 3 water and 2 mammalian animal feces, from which 9 BALOs were obtained: 6 soil (4 from the Tepetitla River, Tlaxcala, Mexico; 1 from the textile zone of Tlaxcala, Tlaxcala, Mexico and 1 garden soil in Cd. Victoria, Tamaulipas, Mexico), 1 water (beach in Cd. Madero, Tamaulipas, Mexico) and 2 mammalian animal feces (Gómez Palacio, Durango, Mexico), managing to isolate the genera Bdellovibrio, Peredibacter and Micavibrio identified by amplification with oligonucleotides of the 16S rRNA gene specific for BALOs, being BbsF216: BbsR707, BdsF:BbsR, 21BdsF:1260BdsR, PerF:PerR and McvF:McvR, respectively. The BALOs present in samples M3, M5, M19, M34, M37 (corresponding to BALOs, B3, B5, B19, B34 and B37, respectively) were purified with Salmonella enterica prey and, for samples M40 and M41 (corresponding to BALOs, B40 and B41, respectively) with Klebsiella pneumoniae prey, and correspond to the Bdellovibrio genus. Sample M7 amplified for the specific oligonucleotides of the Peredibacter and Bdellovibrio genera (corresponding to BALO B7) with S. enterica prey. Sample M34 amplified for the specific oligonucleotides of the Micavibrio and Bdellovibrio genera (corresponding to BALO B34) with S. enterica prey. The Peredibacter and Micavibrio BALOs could not be purified by double layer purification on a Petri dish. In M40 and M41 (corresponding to BALOs, B40 and B41, respectively) the presence of predatory bacteria was confirmed in fecal samples of mammalian animals, thus, it can be concluded that BALOs do not represent a danger for animals, and their resistance to stomach acids allows them to persist in the intestine. The isolated BALOs (B1, B3, B5, B7, B19, B34, B37, B40, B41, B4J) demonstrated to have a wide prey range on Aeromonas species (A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9, A10, A11, A12), since the presence of predation was observed from 5 h to 16.5 h of co-culture. The ten predatory bacteria isolates represent a viable alternative to attack Aeromonas species of clinical and environmental origin.

Acknowledgments

Al Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Beca de Estímulo Institucional de Formación de Investigadores (BEIFI), al Sistema de Becas por Exclusividad (SIBE), al Sistema de Estímulos al Desempeño de los Investigadores (EDI) del IPN. Al Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Atterbury, R. J., Hobley. Effects of orally administered Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus on the well-being and Salmonella colonization of young chicks. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2011, 77, 5794–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awan, F. Dong, Y. Wang, N. Liu, J. Ma, K. & Liu, Y. (2018)a. The fight for invincibility: environmental stress response mechanisms and Aeromonas hydrophila. Microbial Pathogenesis, 116, 135–145. [CrossRef]

- Awan, F., Dong, Y. & Liu, J. (2018)b. Comparative genome analysis provides deep in-sights into Aeromonas hydrophila taxonomy and virulence-related factors. BMC Genomics. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H., He, S., Wang, H., Hou, S., Lu, L. & Yang, X. (2012). Bdellovibrios, potential biocontrol bacteria against pathogenic Aeromonas hydrophila. Veterinary Microbiology, 154: 413–418. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, WH y Zhu, W. (2010). Aislamiento de Bdellovibrio como agentes terapéuticos biológicos utilizados para el tratamiento de la infección por Aeromonas hydrophila en peces. Zoonosis y Salud Pública. 57 (4), 258-264.

- Dashiff, A., Junka, R. A., Libera, M. & Kadouri, D. E. (2011). Predation of human pathogens by the predatory bacteria Micavibrio aeruginosavorus and Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 110, 431–444.

- Dwidar, M., Monnappa. La naturaleza dual probiótica y antibiótica de Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. Informes BMB 2012, 45, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shanshoury, A. E. R. R., Abo-Amer, A. E. & Alzahrani, O. M. (2016). Isolation of Bdellovibrio sp. from wastewater and their potential application in control of Salmonella paratyphi in water. Geomicrobiology Journal, 33, 886–893. [CrossRef]

- Figueras, M. J., Latif-Eugenín, F. & Ballester F. (2017). Aeromonas intestinalis and Aeromonas enterica isolated from human faeces, Aeromonas crassostreae from oyster and Aeromonas aquatilis isolated from lake water represent novel species. New Microbes and New Infections, 15. 74–76. [CrossRef]

- Hoel, S., Vadstein, O. & Jakobsen, A. N. (2017). Species distribution and prevalence of putative virulence factors in Mesophilic Aeromonas spp. isolated from fresh retail sushi, Frontiers in Microbiology, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Janda, J. M. & Abbott, S. L. (2010). The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 35–73. [CrossRef]

- Jurkevitch, É., & Jacquet, S. (2017). Bdellovibrio and like organisms: outstanding predators! Medecine Sciences. M/S, 33(5), 519-527.

- Jurkevitch, Edouard. (2012). Isolation and classification of Bdellovibrio and like organisms. Current Protocols in Microbiology, 1(SUPPL.26). [CrossRef]

- Kadouri, D., Venzon, NC y O’Toole, GA. (2007). Vulnerabilidad de biopelículas patogénicas a Micavibrio aeruginosavorus. Microbiología Aplicada y Ambiental, 73(2), 605-614.

- Ku, Y. H. & Yu W. L. (2015). Extensive community-acquired pneumonia with hemophago-cytic syndrome caused by Aeromonas veronii in an immunocompetent patient. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, 50(4). 555–556. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., Wang, W. & Zhu, Z. (2015). Distribution, virulence-associated genes, and antimicrobial resistance of Aeromonas isolates from diarrheal patients and water, China, Journal of Infection, 600–608. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Qiu, F., Yan, H., Wan, X., Wang, M. & Ren, K. (2018). Increasing the autotrophic growth of Chlorella USTB-01 via the control of bacterial contamination by Bdellovibrio USTB-06. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 124, 1131–1138. [CrossRef]

- Loozen, G., Boon, N., Pauwels, M., Slomka, V., Rodrigues-Herrero, E. & Quirynen, M. (2015). Effect of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus HD100 on multispecies oral communities. Anaerobe. 35: 45–53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. (2017). Organización Mundial de la Salud. https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed.

- WHO. (2020). Organización Mundial de la Salud. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance.

- Oyedara, O. O., De Luna-Santillana, E., de, J., Olguin-Rodriguez, O., Guo, X., Mendoza-Villa, M. A. (2016). Isolation of Bdellovibrio sp. from soil samples in Mexico and their potential applications in control of pathogens. Microbiology open. 5, 992–1002. [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. L. & Shaw, J. G. (2011). Aeromonas spp. clinical microbiology and disease. Journal of Infection, 62(2) 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J., Moraleda-Muñoz, A., Marcos-Torres, F. J. & Muñoz-Dorado, J. (2016). Bacterial predation: 75 years and counting! Environmental Microbiology, 18, 766–779.

- Raghunathan, D., Radford, P. M., Gell, C., Negus, D., Moore, C., Till, R., Tighe, P. J., Wheatley, S. P., Martinez-Pomares, L. & Sockett, R.E. (2019). Engulfment, persistence and fate of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus predators inside human phagocytic cells informs their future therapeutic potential. Nature Scientific Reports, 9, 1–16.

- Ruppé, E., Cherkaoui, A. & Wagner, N. (2018). In vivo selection of a multidrug-resistant Aeromonas salmonicida during medicinal leech therapy. New Microbes and New Infections, 23–27. [CrossRef]

- Shatzkes, K., Singleton, E., Tang, C., Zuena, M., Shukla, S., Gupta, S., Dharani, S., Rinaggio, J., Kadouri, D. E & Connell, N. D. (2017)a. Examining the efficacy of intravenous administration of predatory bacteria in rats. Nature Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1864.

- Shatzkes, K., Tang, C., Singleton, E., Shukla, S., Zuena, M., Gupta, S., Dharani, S., Rinaggio, J., Connell, N. D., & Kadouri, D. E. (2017)b. Effect of predatory bacteria on the gut bacterial microbiota in rats. Nature Scientific Reports. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V. I., Baumann, P., Reichelt, J. L. & Allen, R. D. (1974). Isolation, enumeration, and host range of marine Bdellovibrios. Archives of Microbiology, 98, 101–114.

- Teunis, P. & Figueras, M. J. (2016). Reassessment of the enteropathogenicity of mesophilic Aeromonas species. Frontiers in Microbiology, 1–12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).