1. Introduction

Sarcopenia is a progressive decline in skeletal muscle mass and strength and has been formally recognized as a muscle disease in the International Classification of Diseases. Although sarcopenia is more common in older populations, the decline in muscle mass begins after the age of 40 years, and the negative impact on quality of life, healthcare needs, morbidity, and mortality can affect middle-aged and older adults [

1].

Decreased muscle mass and strength strongly correlate with osteoarthritis (OA). In particular, low thigh muscle mass in middle-aged women is more strongly associated with the development and severity of knee OA than is obesity [

2]. Additionally, the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1, and IL-6 triggered by severe OA further accelerates sarcopenia [

3].

While conservative treatment may be recommended for mild OA, advanced or end-stage OA often necessitates surgical intervention, such as total knee replacement [

4]. However, in younger, more active patients, their limited lifespan and the potential need to revise artificial components can be problematic. Consequently, osteochondral regenerative procedures, such as mesenchymal stem cell (MSCs) implantation, can be used to treat OA in middle-aged patients, provided that damage to the articular cartilage is not extensive [

4].

Surgical treatment for OA can improve symptoms such as pain; however, it is important to consider that preoperative sarcopenia can negatively impact surgical outcomes. Several recent studies have reported that sarcopenia negatively affects orthopedic and cancer surgeries, and is an independent factor that increases the risk of postoperative complications [

5].

In addition, the use of a pneumatic tourniquet during surgery and non-weight-bearing after surgery to protect the surgical site increases catabolism, resulting in the loss of muscle mass [

6], and muscle strength is also weakened by postoperative pain, inflammation, edema, and structural damage caused by arthrogenic muscle inhibition [

7]. Therefore, intervention strategies are needed for middle-aged women with preoperative sarcopenia or those who have undergone surgical treatment, such as non-weight-bearing after surgery, and intervention strategies are needed to minimize the loss of muscle mass and strength and prevent complications from sarcopenia.

Resistance exercise (RE) improves sarcopenia by increasing protein synthesis and improving overall physical functions such as gait speed and balance [

8]. However, patients who undergo surgery are unlikely to regain strength to the extent of their contralateral leg, even if they begin rehabilitation within 24 hours of surgery [

9], and muscle mass is measured as a significantly smaller cross-sectional area (CSA) of the quadriceps muscle than in the non-surgical leg even 1 year after surgery [

10].

Recently, nitrate (NO3-) supplementation has been reported to benefit muscle regeneration and recovery [

11]. NO3- is converted into nitrite and nitric oxide (NO), affecting muscle contraction efficiency and functions related to muscle performance [

12]. NO in the body promotes vasodilation, which improves nutrient and hormone availability to the muscle and enhances calcium metabolism, which increases the contraction of type II muscle fibers and force production [

12], and increases the amount and efficiency of creatine phosphate, a key marker of sarcopenia, which helps with muscle recovery and reduces muscle fatigue [

13].

Based on these effects, we hypothesized that NO3- supplementation in combination with RE would be more effective than placebo supplementation in improving muscle function in middle-aged women with sarcopenia during postoperative rehabilitation. Additionally, we aimed to identify its effects on clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Blinding

This study was a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. All procedures were performed at the Sports Medical Center of an Orthopedic Hospital (JS Hospital, Seoul, Korea), where the patients underwent MSC implantation to treat OA, and all interventions were performed by therapists who were not included in the study.

The groups were randomly assigned by a statistician who was not involved in this study to the RE with NO3- supplementation group (NG) and the RE with placebo supplementation group (PG) using the Research Randomizer program (

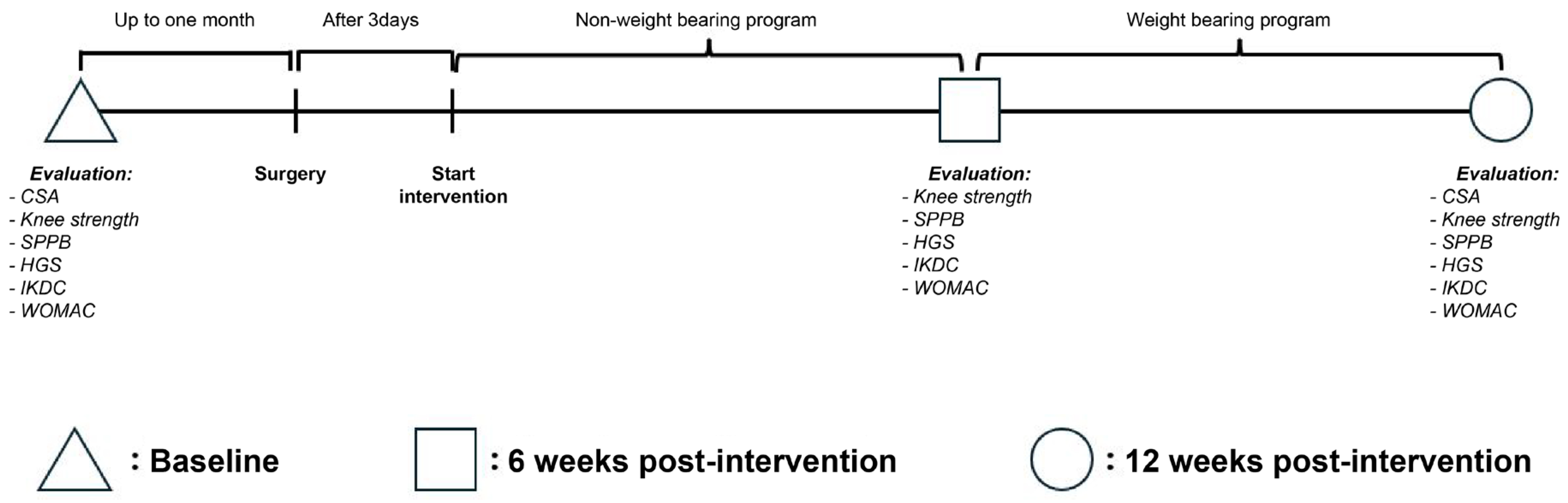

https://www.randomizer.org/). Neither the researcher nor the participants were aware of their group allocation, in accordance with the study’s blinding procedure. Assessments were conducted at baseline and at 6 and 12 weeks post-intervention (

Figure 1).

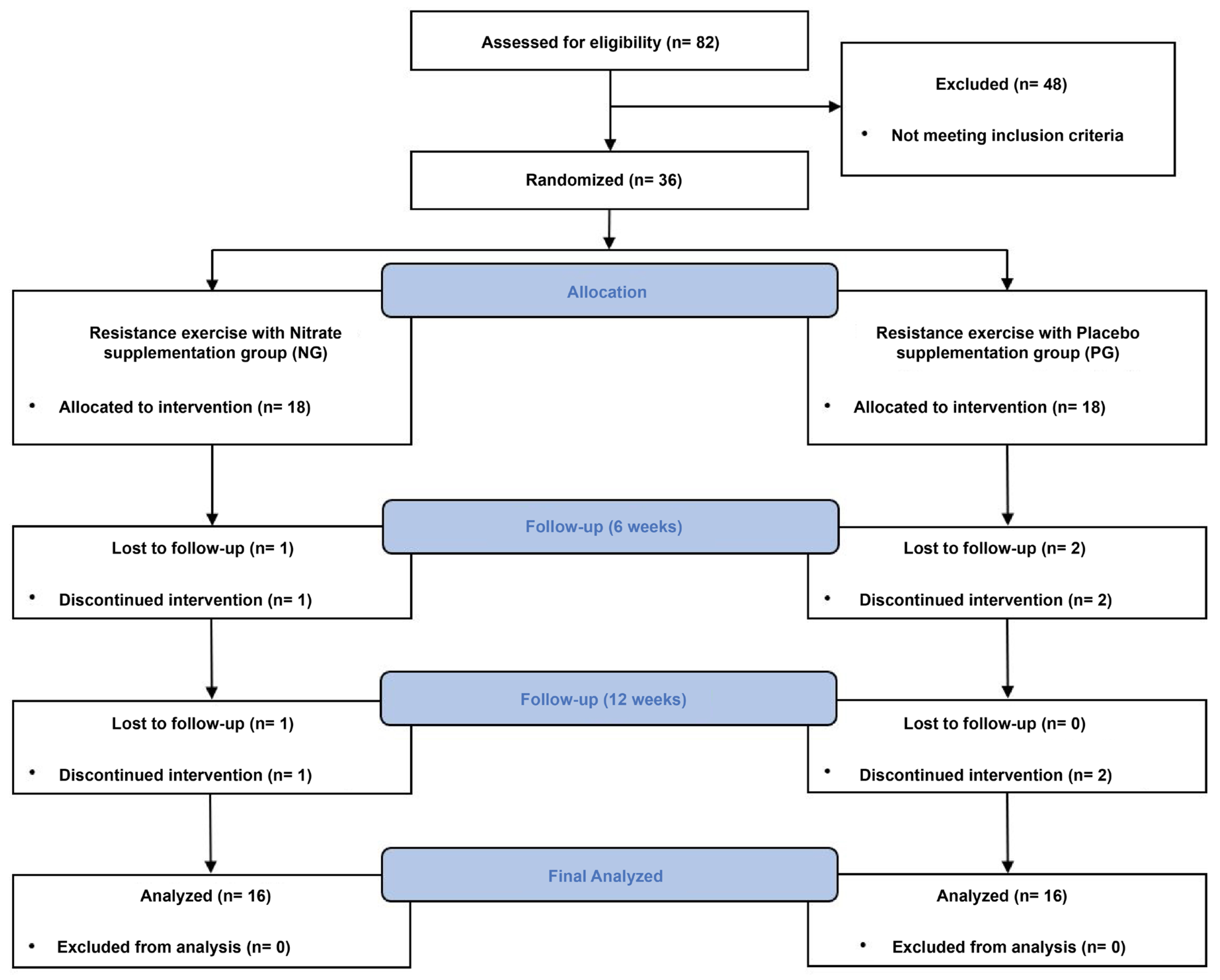

All procedures in this study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea National Sport University (20230621-072). The Clinical Research Information Service approved the clinical trial registration before the first participant was enrolled (KCT0008830). The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram for this study is shown in

Figure 2.

2.2. Participants

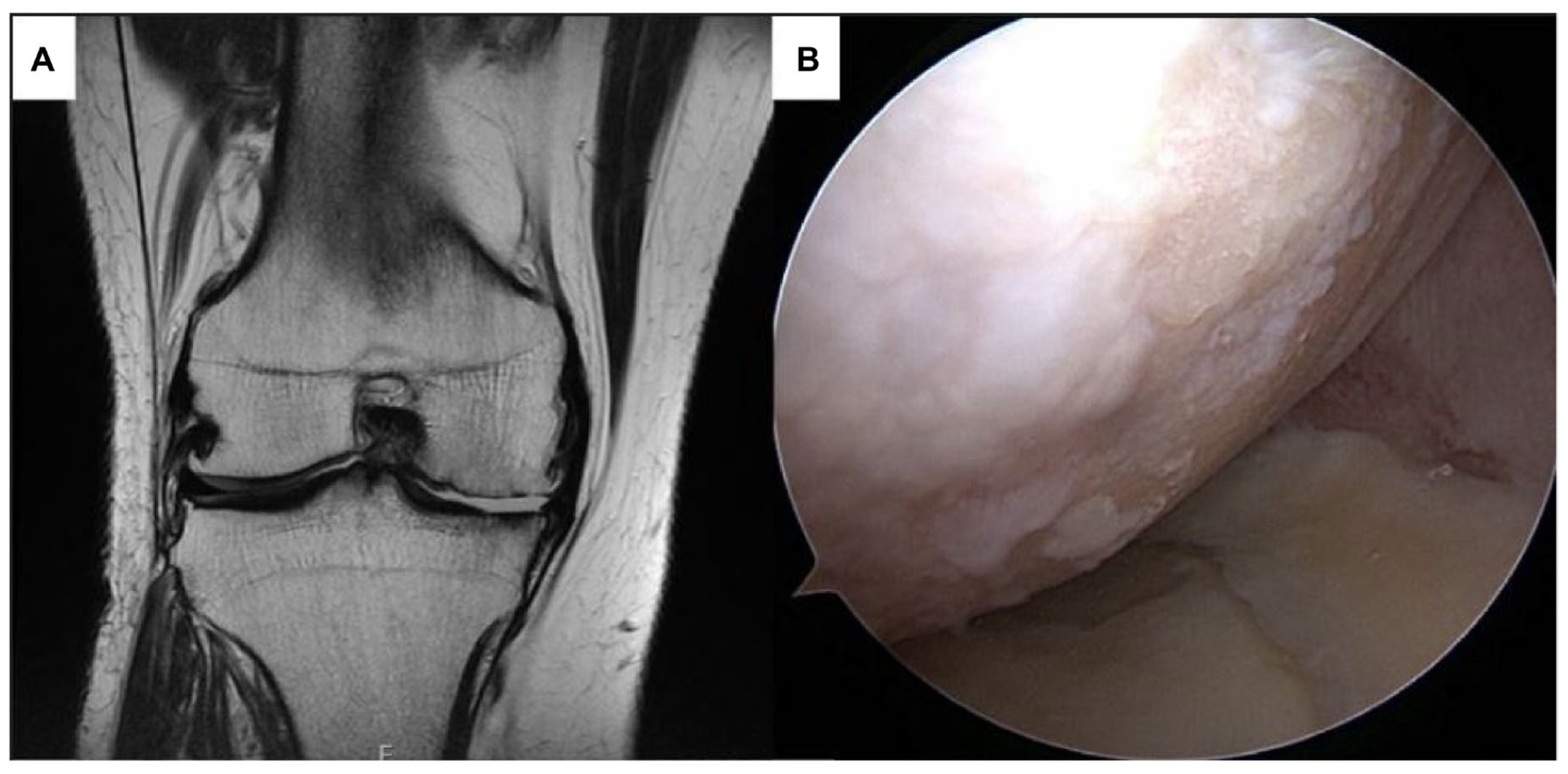

The study included women aged 45–65 years with sarcopenia diagnosed with an International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) grade IV cartilage defect in the medial or lateral femoral condyle and scheduled for MSC implantation within 1 month

Figure 3(A–B). Sarcopenia was defined as a skeletal muscle index (SMI) of less than 5.7 kg/m

2, hand grip strength (HGS) of less than 18 kg, or a Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score of less than 9 points.

The exclusion criteria were severe OA (Kellgren–Lawrence stage 4), a history of acute coronary syndrome or cardiovascular disease, a body mass index of 30 kg/m² or higher, systolic blood pressure outside the range of 115 to 160 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure outside the range of 75 to 100 mm Hg, use of antihypertensive medication, or intake of dietary supplements such as protein and creatine.

The required number of participants was calculated using the G*Power 3.1.9.2 (Kiel, Germany) program, targeting a statistical power of 0.80 and a significance level of 0.05. The effect size was set to 0.22, corresponding to a Cohen’s

d of 0.44, based on the findings of Seo et al. [

14] for midthigh muscle total muscle volume changes in older adult women with sarcopenia after 16 weeks of resistance training. Cohen’s

d was converted to an

F-effect size suitable for the analysis of variance. Considering a potential dropout rate of 20%, 36 participants were recruited to ensure sufficient statistical power and detect meaningful differences between groups.

All participants were informed of the study’s purpose, methods, and risks, and provided written informed consent.

2.3. Resistance Exercise Intervention

The RE intervention was initiated 3 days after surgery and consisted of a non-weight-bearing phase for the first 6 weeks, followed by a full weight-bearing phase for the next 6 weeks, with 24 sessions conducted twice a week for 12 weeks. The sessions were conducted on specific days of the week, such as Mondays and Thursdays, weekends and Fridays, and Wednesdays and Saturdays. The participants were instructed not to engage in any other physical exercise program during the 12 weeks and to maintain their usual levels of physical activity to minimize the influence of external factors.

All sessions were supervised by three physical therapists with at least 5 years of experience who were not involved in the research. Before the intervention, the physical therapists were trained in the intervention program, including the number of repetitions and exercise intensity, to ensure consistent supervision across all participants.

The RE program consisted of warm-up exercises, strengthening exercises with proprioception exercises, and cool-down activities. The OMNI Perceived Exertion Scale for Resistance Exercise set the intensity of the strength exercises at 50–70% of one-repetition maximum, with a scale range of 4 to 6. The intensity increased or decreased if the perceived exertion was lower than 4 or higher than 6 during the RE. In the strengthening phase, each exercise was performed with 12 repetitions for 5 sets at the beginning, with the intensity gradually increasing to 8 repetitions for 5 sets toward the end. The intervals between sets were standardized to ensure consistency across sessions. This protocol helped to control the workload and ensured that all participants performed a similar amount of training, maintaining consistency in the number of repetitions per set for each exercise. The RE interventions used in this study are listed in

Table 1.

2.4. Nitrate Supplementation

The NO3- and placebo groups were provided 70 mL beetroot juice containing a high concentration of NO3- (6.5 mmol NO3-, Beet It Sport; James White Drinks, Ipswich, United Kingdom) and 70 mL placebo with negligible NO3- (0.04 mmol NO3-, James White Drinks, Ipswich, United Kingdom) by a therapist who was not involved in the study. Both drinks contained 18 g carbohydrates, 17 g sugar, 3.7 g protein, and 0.48 g salt.

The provided placebo had the same packaging, color, smell, and taste, such that neither the participants nor the researchers were aware which drink they were consuming. Both drinks were consumed 2 hours before participation in each RE intervention session, with instructions to avoid eating foods rich in NO3-, such as beets, celery, and spinach, for 48 hours before consumption.

2.5. Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of this study was thigh muscle CSA, which was measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Sigma TwinSpeed, GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.). Measurements were performed in the supine position with the knee extended in the MRI machine using Velcro straps to restrict knee movement. T2-weighted axial images were obtained at 8 mm intervals, with an echo time of 119 ms, repetition time of 6120 ms, and field of view of 400 mm on a 512 × 512 matrix. The thigh muscle CSA was measured by first confirming the length from the greater trochanter to the lateral epicondyle using full-length femur radiography and then measuring a T2-enhanced cross-section at 50% of this length. The measurements were calculated using the accessible regions of interest (ROI) tool of the Picture Archiving and Communication System program (Viewrex, TECHHEIM, Guro, Republic of Korea), outlined along the fascia and calculated values, and performed twice by a radiologist with an interval of 72 hours between measurements [

15] (

Supplementary Figure S1). The reliability of the measured values was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and values above 0.8 were used in the analysis. Thigh muscle CSA was assessed at baseline and 12 weeks after the intervention.

Another primary study outcome, knee strength, was measured using isokinetic dynamometry (Isokinetic Dynamometer; HUMAC Norm; CSMi, Stoughton, MA, U.S.A.) to determine the maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) of the knee in extension and flexion. The participant was first seated on a chair with the hip and knee joints flexed at 90° and 60°, respectively, and the trunk and pelvis were secured to the chair using a seatbelt. The leg was secured with an ankle strap 3 cm above the lateral malleolus of the fibula, and the axis of rotation of the dynamometer was aligned with the lateral epicondyle of the femur. Submaximal contractions with a 5-second rest period between sets were performed twice in extension and flexion, with verbal feedback and encouragement to maximize contraction via a monitor displaying torque values during the test. After a 10-second rest period following the submaximal contraction, two 5-second MVIC of the knee extensor were measured, with a 5-second rest period between contractions. After measuring the knee extensors, the MVIC of the knee flexors was measured in the same manner. The highest of the two measurements was used in the analysis, which was expressed as a percentage (%) of peak torque/body weight [

16]. Knee strength was assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 weeks after the intervention.

2.6. Secondary Outcome

As secondary outcomes, the SPPB, SMI, and HGS were assessed relating to sarcopenia; the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scores were measured for further OA symptoms.

The SPPB is a useful tool for measuring lower extremity function and is an objective tool that can predict impairment in mobility during activities of daily living [

17]. The SPPB test tool consists of balance, gait speed, and repeated chair stand test items, with a score ranging from 0 (lowest performance) to 4 (highest performance), depending on the performance of each item, for a total of 12 points.

For the balance test, the measurements were performed in the following order: side-by-side, semi-tandem, and tandem. The normal and semi-tandem stances were worth 1 point each for 10 seconds, whereas the tandem stance was worth 1 point for 3 seconds or more and 2 points for 10 seconds or more. Failure to maintain the normal position for 10 seconds resulted in a score of 0 for failure to perform.

For the gait speed test, 0 points were allocated for not being able to walk, 1 point for >8.7 seconds, 2 points for 6.21–8.7 seconds, 3 points for 4.82–6.20 seconds, and 4 points for <4.82 seconds. The test was performed twice, and the participants were allowed to use crutches or walking aids to assist with walking.

Finally, the repeated chair stand test measured the time to sit down and stand up from a chair with the arms crossed over the chest five times, with a score of 0 for >60 seconds, 1 for 16.7–60 seconds, 2 for 13.7–16.7 seconds, 3 for 11.2–13.7 seconds, and 4 for <11.2 seconds. No verbal encouragement was provided during the test to ensure that the results reflected the participants’ natural performances. The test was stopped if the use of hands or arms or a fall was anticipated during the test and was scored as 0. The measured values were summed into composite scores and used for the analysis. Measurements were taken at baseline and 12 weeks after the intervention. The test–retest reliability of the SPPB instrument was reported to be 0.87, and convergent validity was reported to be

P = 0.015 [

17].

SMI was evaluated using a body water analyzer (BWA 2.0; InBody Co., Gangnam, Korea) based on the principle of bioelectrical impedance analysis. According to the manufacturer’s guidelines, measurements were performed in the morning after the participants fasted for at least 2 hours, and all objects that could conduct an electric current were removed from the body. The room temperature was maintained at 20–25 °C during the measurement, and the participant was kept in the supine position on the bed for at least 10 minutes to limit the movement of body fluids. Measurements were performed with clamp-like electrodes placed on both the wrists and ankles, with the participant’s arms and torso not touching, arms approximately 15° apart, thighs not touching, and legs approximately shoulder-width apart. SMI measurements were performed at baseline and at 6 and 12 weeks after the intervention.

HGS was measured using a digital grip dynamometer (Grip dynamometer; K-grip

®, KINVENT, Montpellier, France). For the measurement, the participants were asked to sit with the hip and knee joints flexed at 90°, shoulder adducted from a neutral position, and elbow flexed at 90° with the forearm in semi-pronation with no radial or ulnar deviation. The measurements were performed three times with the dominant hand for 5 seconds in each trial, and verbal feedback was provided during the measurement to determine the maximum force. A 1-minute break was provided between the trials to avoid fatigue during the test. The highest value obtained after three measurements was used for the analysis. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the HGS assessment was 0.94 [

18]. SMI and HGS were assessed before baseline and at 6 and 12 weeks after the intervention.

The IKDC questionnaire is used to assess symptoms of knee OA and other knee-related injuries. This tool evaluates the overall health of the knee joint, including symptoms, limitations in daily activities, and restrictions in sports due to damage caused by conditions such as ligament injury or OA. The questionnaire is divided into three categories: symptoms, sports activities, and knee function, comprising a total of 18 questions. Responses are converted to a normalized score ranging from 0 to 100, with 100 indicating no symptoms or limitations. In this study, the summed raw scores were divided by the maximum possible score (87) and multiplied by 100 to standardize the results. The internal consistency of this screening tool was reported to be 0.91, and construct validity was reported to be

P < 0.01 [

19].

The WOMAC is a standardized questionnaire that assesses the condition of patients with knee OA, including pain, stiffness, and joint function. Higher scores indicate greater pain, stiffness, and functional limitations. The WOMAC includes 5 items for pain (score range: 0–20), 2 items for stiffness (score range: 0–8), and 17 items for functional limitations (score range: 0–68), for a total of 96 points. The test–retest reliability for pain, stiffness, and function (activities of daily living) was reported to be 0.91, 0.89, and 0.90, respectively, and the construct validity was reported to be

P < 0.01 [

20].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical program SPSS/PC for Windows (Version 23.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, U.S.A) was used to analyze the data. Data distribution was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For the homogeneity test, the independent t-test was used for normally distributed dependent variables among continuous data, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for MVIC of the knee extensor and SPPB that were not normally distributed. Fisher’s exact test was used to test the homogeneity of the nominal data. Two-way repeated-measures measures analysis of variance was used to test for differences in normally distributed dependent variables. Mauchly’s test for sphericity was applied, with sphericity assumed to be P >.05, and Wilks lambda was used if P < 0.05. Post-hoc analyses were performed with a simple main analysis effect using the Bonferroni correction. Variables that were not normally distributed were tested for differences using generalized estimating equations, with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for within-group differences and the Mann–Whitney U test using Bonferroni correction. Differences between the groups were expressed using Cohen’s d effect sizes (ES). ES was defined as a small effect size of <0.2, a medium effect size of 0.5, or a large effect size of >0.8. All statistical significance levels were set at α <0.05.

3. Results

Thirty-six participants were included in the study; however, two participants, one each from the NG and PG, dropped out because of requests to discontinue the intervention, resulting in a final sample size of 16 participants in each group. Pre-intervention data collection occurred an average of 8.92 ± 2.71 days before participation in the intervention, and post-intervention data collection occurred an average of 3.91 ± 2.46 days after the end of the intervention.

Intervention compliance was recorded throughout the study to ensure equal participation in both groups. The NG showed an attendance rate of 94.79 ± 5.38%, while the PG had a similar attendance rate of 94.53 ± 5.43%. The difference between the groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.892, ∆: 0.26 [95% confidence interval {CI}: -3.64 to 4.16]). These results confirm that both groups participated in an equivalent number of training sessions, thereby supporting the study’s internal validity and ensuring that the observed effects were related to the intervention rather than to the differences in attendance.

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups before the intervention; details are shown in

Table 2.

3.1. Primary Outcomes

The thigh muscle CSA showed a significant interaction effect of time × group (P = 0.041, ES = 0.9) and a significant difference within the groups (P < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the NG did not exhibit a significant difference, whereas the PG showed a decrease 12 weeks after the intervention.

The knee extension MVIC demonstrated a significant interaction effect of time × group (P = 0.045, ES = 1.1) and a significant difference within (P < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis indicated that the NG had higher values than the PG did at 6 and 12 weeks after the intervention. In both groups, there was no significant difference at 6 weeks after the intervention; however, there was an increase at 12 weeks after the intervention.

Knee flexion MVIC showed a significant difference within the groups (

P <0.001), but no significant interaction effect of time × group (

P = 0.068, ES = 0.7). Post-hoc analysis demonstrated that the knee flexion MVIC in the NG increased at 6 and 12 weeks after the intervention compared to before the intervention, whereas in the PG, it increased only at 12 weeks after the intervention. Detailed information on the primary outcomes is presented in

Table 3.

3.2. Secondary Outcomes

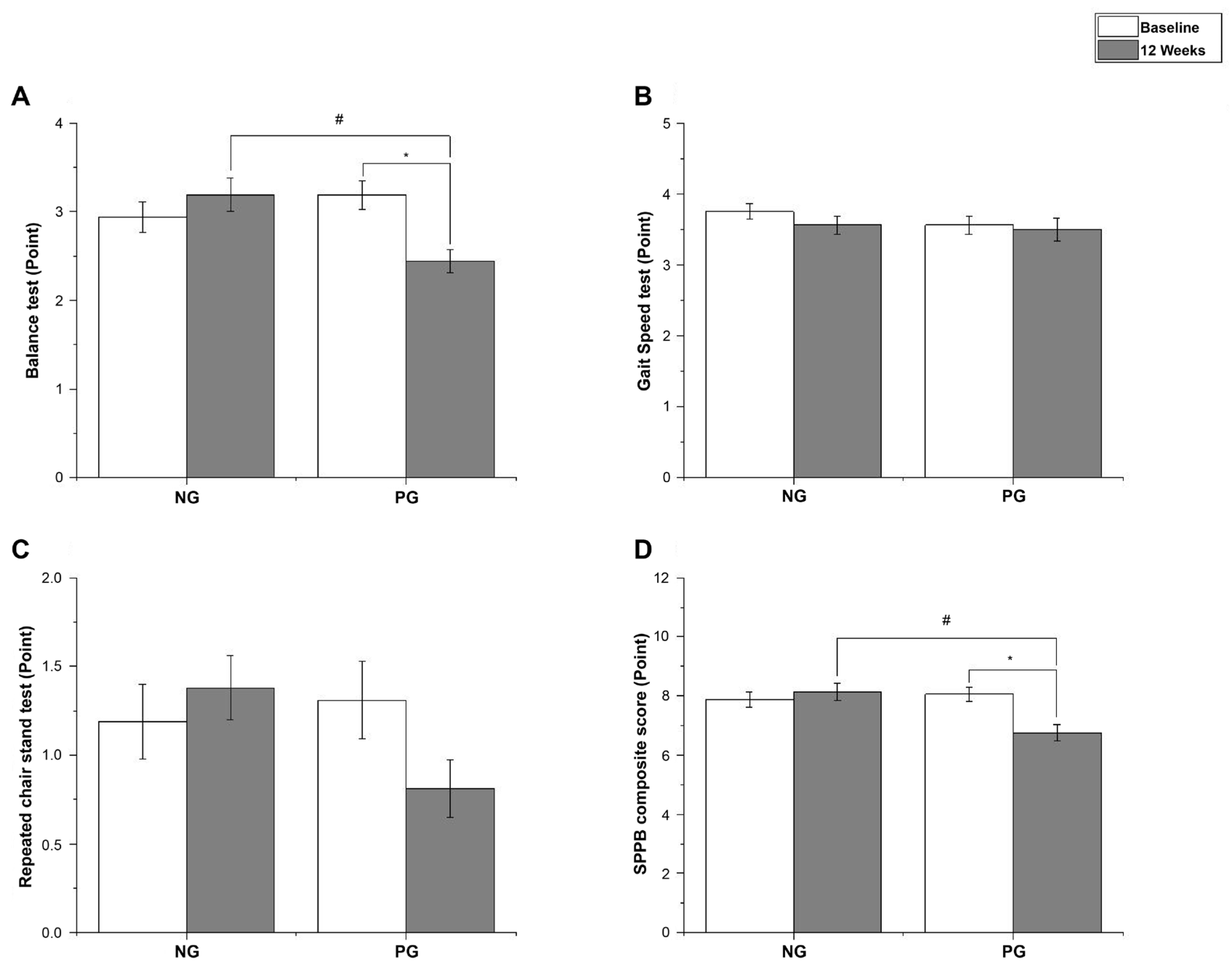

The balance test of the SPPB showed a significant interaction effect of time × group (

P =0.001, ES = 1.2), but no significant difference was observed within (

P = 0.070). Post-hoc analysis showed that the SPPB score in the NG did not significantly change (

P = 0.305, ∆: 0.25 [95% CI: -0.78 to 0.28]), but in the PG, it decreased at 12 weeks after the intervention (

P = 0.005, ∆: 0.75 [95% CI: 0.34 to 1.16]). Gait speed test did not show a significant interaction effect of time × group (

P = 0.678, ES = 0.1) and was not significantly different within (

P = 0.394). Repeated chair stand test did not show a significant interaction effect of time × group (

P = 0.245, ES = 0.8) and was not significantly different within (

P = 0.259). The SPPB composite score showed a significant interaction effect of time × group (

P = 0.001, ES = 1.2) and a significant difference within (

P = 0.025). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the NG showed no significant difference (

P = 0.467, ∆: 0.25 [95% CI: -0.99 to 0.49]), whereas the PG decreased at 12 weeks after the intervention (

P = 0.005, ∆: 1.31 [95% CI: -0.52 to 2.11]). The SPPB results are shown in

Figure 4(A–D).

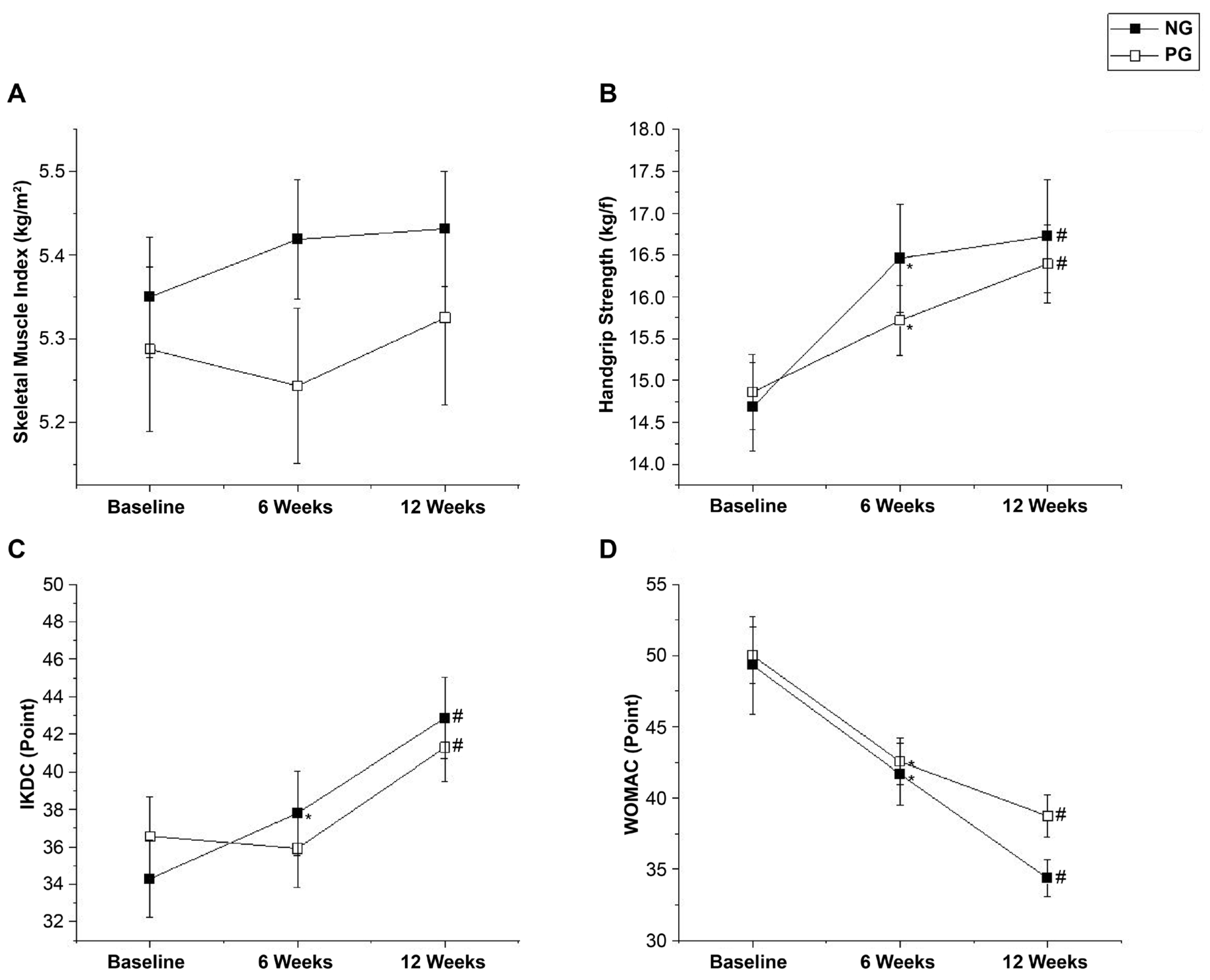

SMI did not show a significant interaction effect of time × group (P = 0.278, ES = 0.3) and was not significantly different within (P = 0.211).

HGS showed a significant difference within the groups (P < 0.001) but no significant interaction effect of time × group (P = 0.100, ES = 0.1). Post-hoc analysis showed that HGS in both the NG and PG increased at 6 (P < 0.001, ∆: 1.78 [95% CI: -2.56 to -0.99]; P = 0.009, ∆: 0.86 [95% CI: -1.35 to -0.37], respectively) and 12 weeks (P < 0.001, ∆: 2.04 [95% CI: -2.76 to -1.32]; P < 0.001, ∆:1.53 [95% CI: -2.13 to -0.93], respectively) after the intervention.

The IKDC score showed a significant interaction effect of time × group (P = 0.034, ES = 0.2) and a significant difference within the groups (P < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed that the IKDC score in the NG increased at both 6 and 12 weeks after the intervention (P = 0.004, ∆: 3.50 [95% CI: -6.27 to -0.72]; P < 0.001, ∆: 8.57 [95% CI: -11.03 to -6.12], respectively), but in the PG, it increased only at 12 weeks after the intervention (P < 0.001, ∆: 4.73 [95% CI: -6.54 to -2.91]).

The WOMAC score showed a significant difference within the groups (

P < 0.001) but no significant interaction effect of time × group (

P = 0.451, ES = 0.8). Post-hoc analysis showed that the WOMAC score in both the NG and PG decreased at 6 weeks (

P < 0.001, ∆: 7.63 [95% CI: 3.43 to 11.82];

P = 0.001, ∆: 7.44 [95% CI: 3.38 to 11.49], respectively) and 12 weeks (

P < 0.001, ∆: 14.94 [95% CI: 9.66 to 20.22];

P < 0.001, ∆: 11.25 [95% CI: 7.27 to 15.23], respectively) after the intervention. The SMI, HGS, IKDC, and WOMAC results are shown in

Figure 5(A–D).

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of RE combined with NO3- supplementation on middle-aged women with sarcopenia undergoing MSC implantation. Our findings show that NO3- supplementation effectively prevented muscle atrophy and enhanced knee extension strength, offering a novel approach to improving postoperative rehabilitation outcomes in this population. The ongoing advancement of therapeutic technologies, such as MSCs, has proven safe and effective in treating OA, a condition for which the only alternative is total knee replacement. These therapies have been shown to improve quality of life by reducing chronic pain and inflammation and enhancing mobility [

21]. Unresolved issues, such as atrophy of the thigh muscles, persist despite the development of these medical technologies, increasing the risk of developing serious complications, such as falls, along with functional impairments, such as poor balance [

22].In particular, sarcopenia may negatively affect rehabilitation outcomes because of the associated low SMI. Liao et al. [

5] have found that patients with sarcopenia showed less improvement in mobility and physical function after surgery than did patients without sarcopenia. Therefore, interventions to prevent rapid atrophy of the thigh muscle mass after surgery are important for patients with sarcopenia and should be considered to restore mobility and physical function.

In this study, patients diagnosed with sarcopenia, according to the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia criteria, undertook RE and were administered 400 mg NO3- supplementation to prevent rapid postoperative atrophy of the thigh muscles. The results indicated that the thigh CSA significantly decreased in the PG, whereas in the NG, there was no significant difference compared to preoperative values. This finding suggests that NO3- supplementation with RE is an effective strategy for preventing postoperative thigh muscle atrophy. Although this study did not include blood analysis to elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying this effect, preventing muscle atrophy in the NG was likely attributable to enhanced muscle stimulation and strength gains induced by the combined intervention.

Post-intervention thigh extension strength increased in both groups but was significantly higher in the NG at 6 and 12 weeks. The strength-enhancing effects of NO3- supplementation were further supported by the findings of Coggan et al. [

23] and Sim et al. [

24].

Although the exact mechanism behind the strength increases induced by NO3- is not fully understood, several previous studies have provided valuable insights. For instance, Ferguson et al. [

25] have reported that NO3- supplementation enhances oxygen delivery to type II muscle fibers, thereby improving metabolic control. Hernández et al. [

26] have reported that NO3- ingestion not only results in significant elevations in plasma NO3- and nitrite levels but also increases the expression of receptors such as calsequestrin-1 and dihydropyridine, which regulate Ca

2+ metabolism to enhance contractile function in type II muscle fibers. Because these increases were not observed in slow-twitch muscle fibers, this suggests that NO3- may act specifically on type II muscle fibers, contributing to greater velocity and strength development [

26]. In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Campos et al. [

27] has revealed that NO3- intake reduces the cost of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) utilization, improves mitochondrial efficiency, and increases blood flow to type II muscle fibers, thereby enhancing muscle contractility and delaying fatigue. Increased blood flow to type II muscle fibers may be attributed to the biological effects of reduced NO. Enhanced blood flow during RE facilitates the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the muscles and improves ATP replenishment between sets [

28]. These physiological benefits can delay fatigue and permit a greater workload, enhancing anabolic stimulation and promoting muscle protein synthesis [

28].

The enhancement of strength facilitated by NO3- intake can increase mechanical tension, which is a critical factor in muscle hypertrophy. Insufficient mechanical tension can lead to muscle atrophy, whereas elevated tension promotes muscle mass increase [

29]. Consequently, the prevention of muscle atrophy observed in the NG was likely attributable to heightened muscle stimulation and strength gains, surpassing those in the PG.

Several studies have reported that NO prevents muscle damage and positively influences regeneration and recovery [

11]. Córdova-Martínez et al. [

13] have demonstrated that NO3- intake combined with a physical activity program increased serum creatinine levels and decreased total protein levels. Low creatinine levels and high total protein levels have been associated with sarcopenia, including the loss of muscle mass and function. Therefore, increasing the expression of these biomarkers may serve as a protective strategy against sarcopenia [

30]. In this study, RE in combination with NO3- supplementation prevented muscle atrophy and improved muscle strength; however, there was no evidence of muscle hypertrophy related to the improvement in strength. These results suggest that the initial strength gains were attributable to increased muscle activation from NO3- ingestion rather than from increased muscle mass. Increased vastus lateralis muscle activation following NO3- ingestion, as reported by Esen et al. [

31] supports this assertion. Future research should investigate the mechanisms underlying the prevention of muscle atrophy and enhancement of muscle strength by conducting detailed analyses of blood parameters.

This study analyzed factors associated with sarcopenia as a secondary outcome. Indeed, patients with knee OA have lower skeletal muscle mass than do healthy subjects, which may serve as an independent risk factor for sarcopenia [

32]. Therefore, effective strategies for preventing sarcopenia in patients with OA are essential. In the SPPB results related to sarcopenia, the NG showed no difference in any items from before the intervention. In contrast, the PG exhibited a decrease in the SPPB composite score, including balance. This result can be attributed to knee extensor strength, which has been validated as an important factor related to balance by Brech et al. [

33] and Takacs et al. [

34].

However, the SMI was not reduced in either group. The lack of reduction is likely due to the positive effects of RE on muscle mass and function, as indicated in a systematic review and meta-analysis by Beaudart et al. [

35] Despite the positive effects of RE, NO3- intake did not contribute significantly to increasing SMI. Contrary to these results, a study by Liao et al. [

5] used RE with leucine-containing protein intake in patients with OA aged 60 years and older and found that their SMI improved. These results emphasize the importance of protein and essential amino acid intake for muscle mass gain and are consistent with the findings of McKendry et al. [

36].

Finally, for the sarcopenia variable, HGS increased in both groups. The improvement in HGS after NO3- ingestion has been validated in previous studies [

24], but we could not identify a difference between the two groups in this study. This lack of difference may be because RE is also effective in improving HGS, as shown by Lichtenberg et al. [

37], who compared RE plus protein intake with protein intake alone in patients with sarcopenia and found an increase in HGS in the RE group. Therefore, it can be concluded that RE has a positive effect on HGS.

Among the OA symptoms examined as secondary outcomes, improvements in the IKDC scores in the NG were found at 6 and 12 weeks after the intervention. In contrast, the PG showed improvements only at 12 weeks after the intervention. These findings indicate that NO3- intake enhances early knee extensor strength more effectively. Martien et al. [

38] have identified knee extensor strength as a predictor of performance in a modified physical performance test and the 6-minute walk test, while Casaña et al. [

39] have reported a correlation between stair climbing time and knee extensor strength. Therefore, knee extensor strength is a critical determinant of patient function, which may account for the rapid postoperative increase in IKDC scores observed in the NG.

In terms of the WOMAC score, improvements were observed in both groups, with no significant differences. These findings suggest that in the short term, OA symptoms such as pain are more likely alleviated by surgical intervention than by muscle mass and strength changes. In a study by Song et al. [

21], both the IKDC and WOMAC scores showed significant improvement 2 years after MSC implantation, with ICRS grade IV cartilage defects improving to grades Ⅰ–Ⅱ. Thus, it is plausible that the surgical method is crucial in alleviating symptoms such as postoperative pain.

The present study provides new insights into the role of NO3- supplementation combined with RE in improving postoperative outcomes among middle-aged women with sarcopenia undergoing MSC implantation for OA. Our findings suggest that this combined intervention effectively prevents muscle atrophy and enhances knee extensor strength, which is critical for rehabilitation. While previous research has highlighted the benefits of NO3- supplementation in muscle performance and recovery, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to examine its combined impact with RE in a postoperative setting. The results are particularly significant given the high prevalence of sarcopenia and its negative effect on post-surgical recovery, as described in earlier studies on orthopedic outcomes and muscle degeneration. Our study highlights the potential of NO3- supplementation to complement established rehabilitation strategies and suggests that targeting muscle strength early in the recovery process may accelerate functional improvements.

This study has certain limitations. First, because the groups were classified into NG and PG, the effect of NO3- alone could not be determined. Therefore, the results of this study cannot be attributed to the effect of NO3- alone but rather to the combined effect of RE and NO3-. Second, the intervention period was relatively short. This study evaluated the thigh muscle CSA as the primary outcome and found that RE in combination with NO3- supplementation prevented thigh muscle atrophy. However, we were unable to confirm muscle hypertrophy in the NG, and we believe that a study with a longer intervention period is needed to confirm muscle hypertrophy. Third, the study excluded patients with Kellgren–Lawrence grade IV OA. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all patients with OA. However, the MSC implantation procedure that the participants underwent in this study could not be performed because Kellgren–Lawrence grade IV OA is a contraindication in Korea, and future studies should include patients with Kellgren–Lawrence grade IV OA. Fourth, we did not control for or monitor the participants’ daily dietary habits, which could influence muscle function and recovery. Although the participants were instructed to avoid foods rich in NO3-, other aspects of their diet were not closely regulated, and future studies should consider dietary monitoring to minimize variability. Finally, while the training workload was standardized, we did not closely monitor individual variations in workload during the RE. This lack of monitoring could affect the consistency of the training stimuli across participants, and future studies should incorporate more detailed monitoring of the training load to ensure consistency.