Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

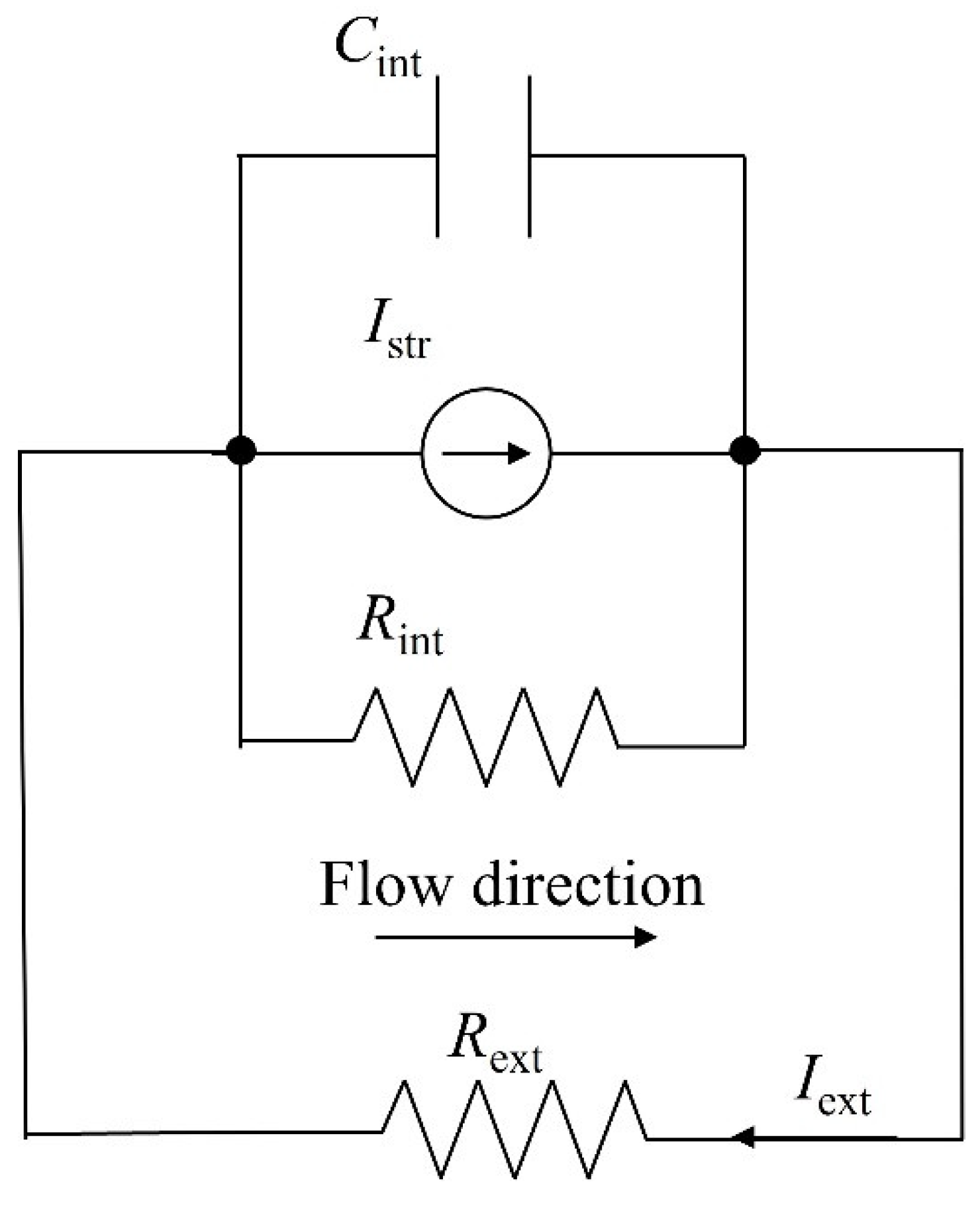

2. Development of the Simplified Capacitor-Current Circuit Model

2.1. Overview of the Mansouri Model

2.1.1. Introduction to the Electrical Analogy

2.1.2. Exploring Streaming Current: From Basics to Complex Models

2.2. Development of the Simplified Capacitor-Current Model

3. Materials and Methods

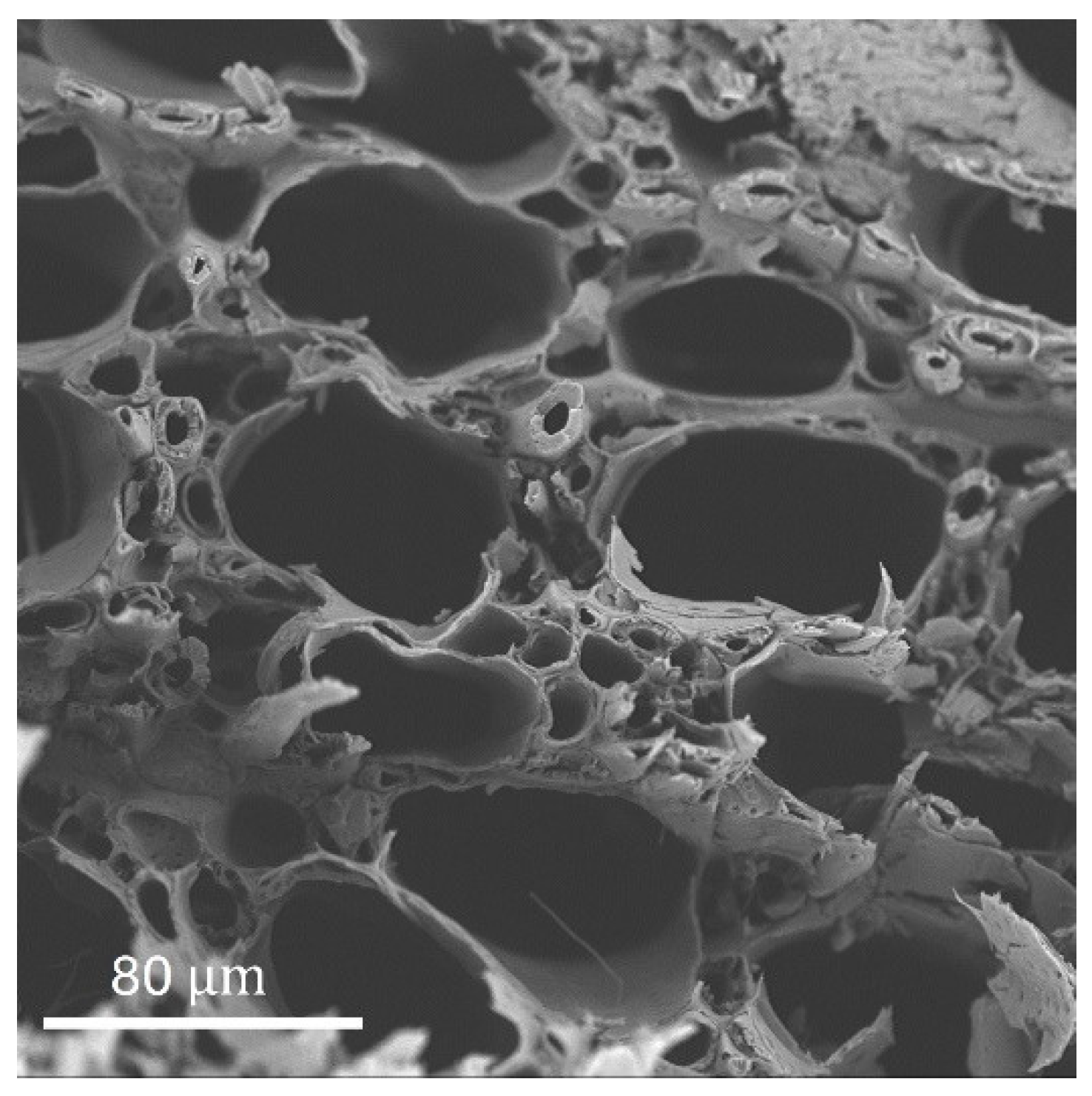

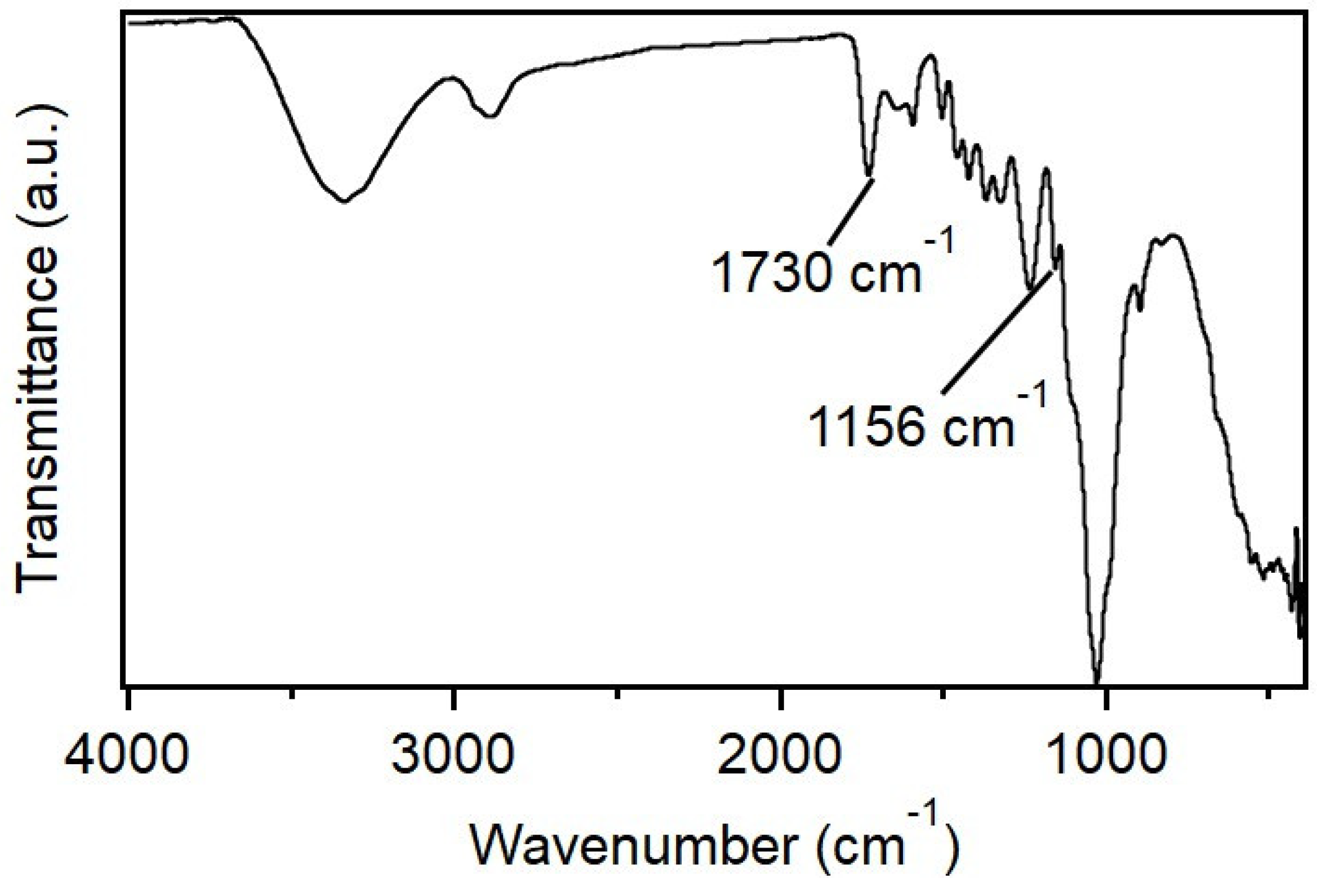

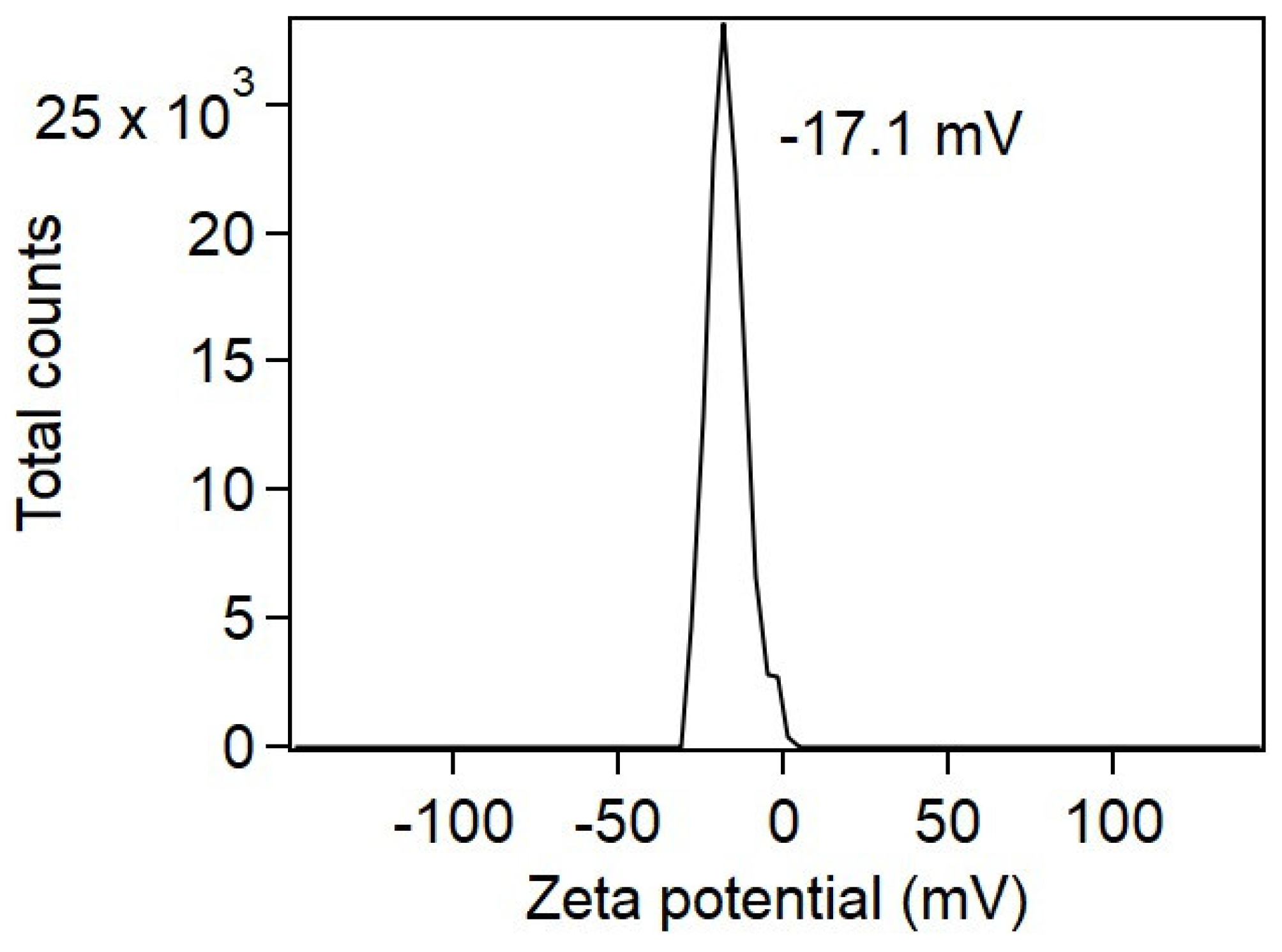

3.1. Materials and Characterizations

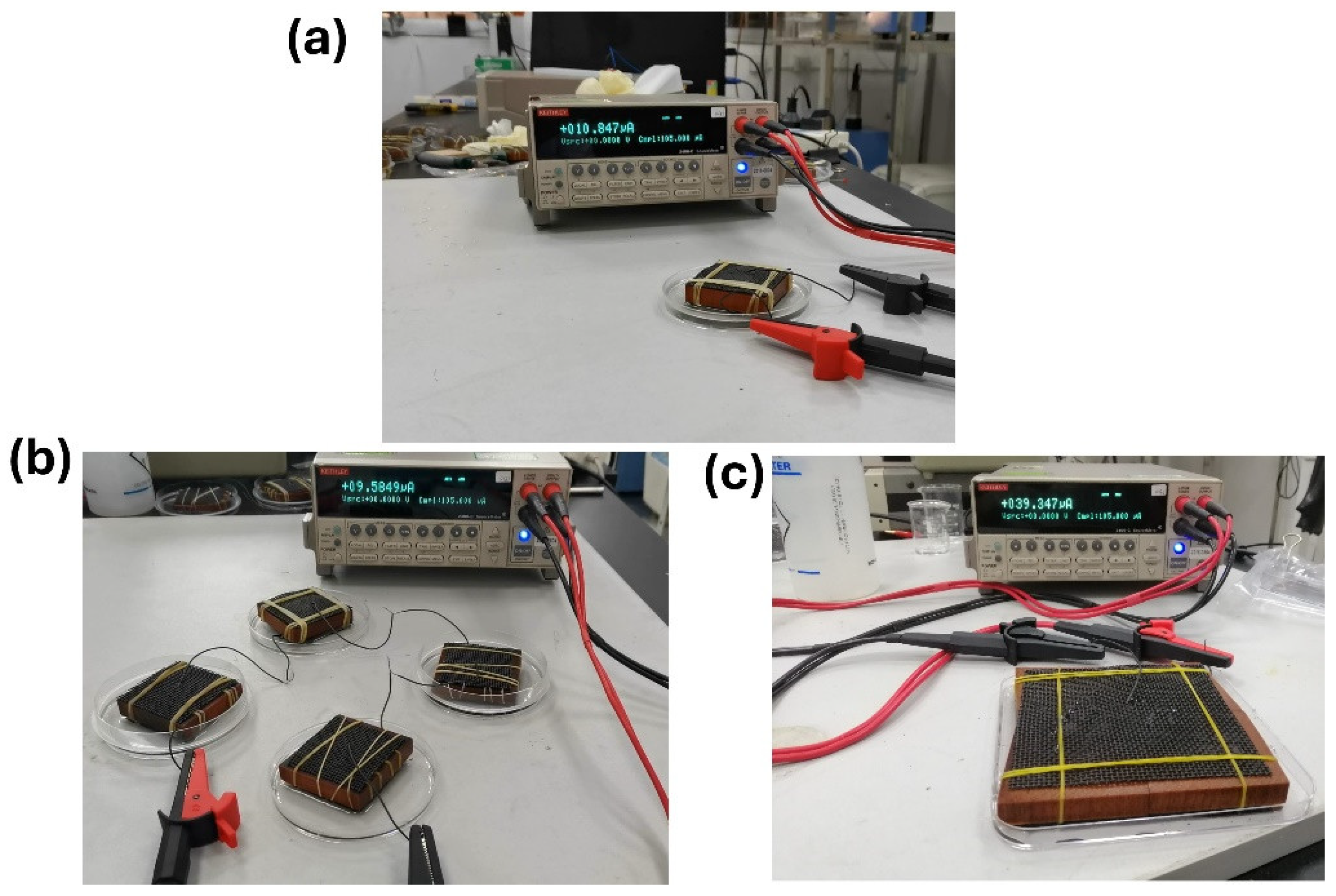

3.2. Device Fabrication, Data Collection and Fitting

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Materials Characterization and Device Fabrication

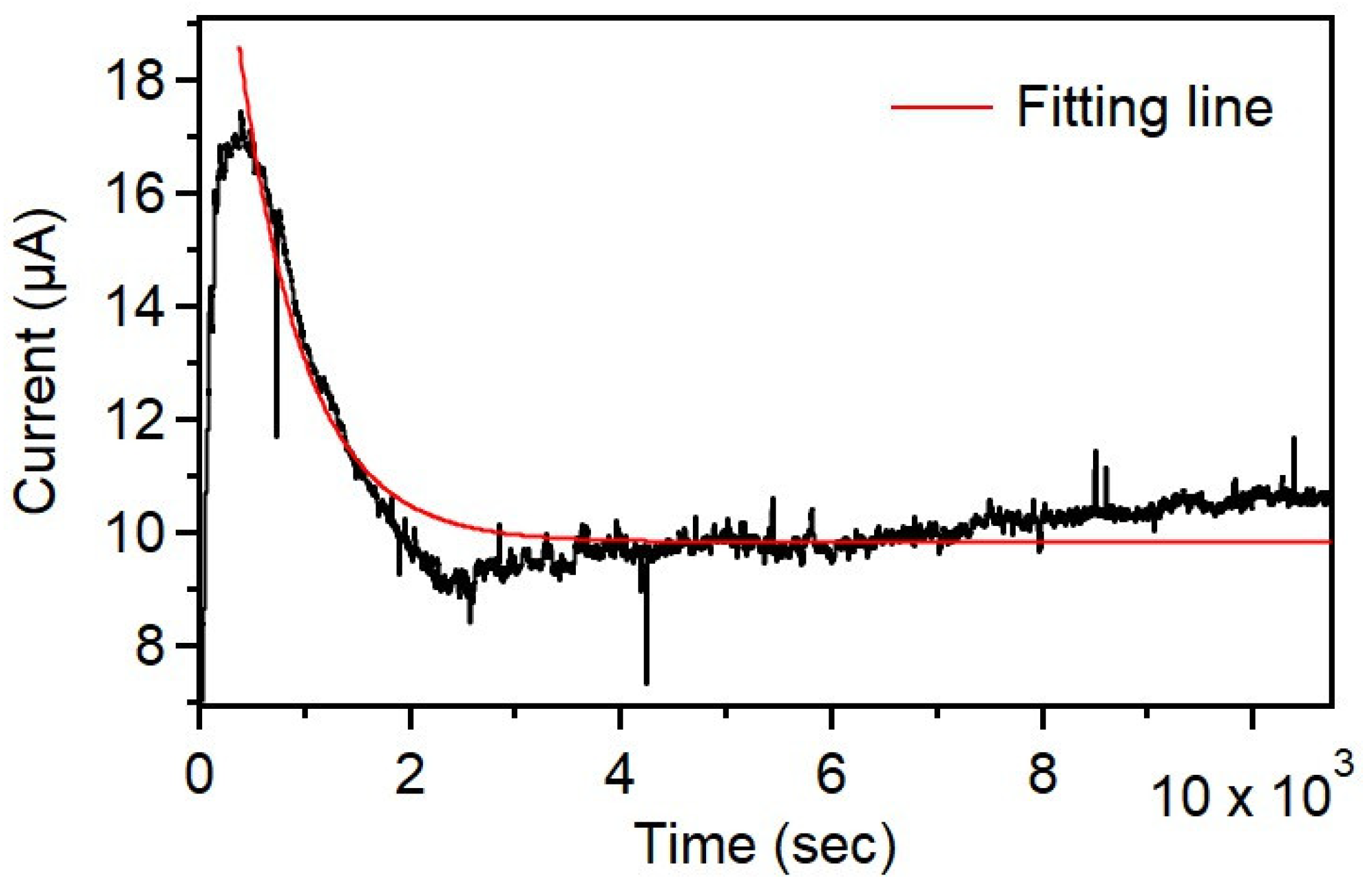

4.2. Model Fitting Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Sustainable Development Report 2023: Times of crisis, times of change: Science for accelerating transformations to sustainable development; United Nations: New York, 2023.

- Xue, G.; Xu, Y.; Ding, T.; Li, J.; Yin, J.; Fei, W.; Cao, Y.; Yu, J.; Yuan, L.; Gong, L.; et al. Water-evaporation-induced electricity with nanostructured carbon materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 317-321. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Yin, J.; Xu, Y.; Fei, W.; Xue, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Guo, W. Emerging hydrovoltaic technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 1109-1119. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, F.; Wang, X.; Fang, S.; Tan, J.; Chu, W.; Rong, R.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Hydrovoltaic technology: from mechanism to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 4902-4927. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, X.; Chu, W.; Fang, S.; Zheng, C.; Xue, M.; Wang, X.; Hu, T.; Guo, W. Harvesting Energy from Atmospheric Water: Grand Challenges in Continuous Electricity Generation. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2211165. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Qu, L. Direct Power Generation from a Graphene Oxide Film under Moisture. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 4351-4357. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Yang, C.; Yao, H.; Li, C.; Qu, L. All-region-applicable, continuous power supply of graphene oxide composite. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1848-1856. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Ward, J.E.; Liu, X.; Yin, B.; Fu, T.; Chen, J.; Lovley, D.R.; Yao, J. Power generation from ambient humidity using protein nanowires. Nature 2020, 578, 550-554. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Yoon, S.G.; Lee, W.H.; Cho, Y.H.; Han, J.; Park, J.; Kim, Y.S. Identification of water-infiltration-induced electrical energy generation by ionovoltaic effect in porous CuO nanowire films. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 3432-3438. [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Yun, T.G.; Suh, B.L.; Kim, J.; Kim, I.-D. Self-operating transpiration-driven electrokinetic power generator with an artificial hydrological cycle. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 527-534. [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kim, M.S.; Oh, T.; Suh, B.L.; Yun, T.G.; Lee, S.; Hur, K.; Gogotsi, Y.; Koo, C.M.; Kim, I.-D. Towards Watt-scale hydroelectric energy harvesting by Ti3C2Tx-based transpiration-driven electrokinetic power generators. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 123-135. [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Shen, C.; Guo, W. Evaporating potential. Joule 2022, 6, 690-701. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, R.T.; Huang, Y. Progress of Capillary Flow-Related Hydrovoltaic Technology: Mechanisms and Device Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9589. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Kostiuk, L.W. Electrokinetic Energy Conversion by Microchannel Array: Electrical Analogy, Experiments, and Electrode Polarization. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 24310-24324. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Kostiuk, L.W. Giant streaming currents measured in a gold sputtered glass microchannel array. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 646, 81-86. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Vali, A.; Kostiuk, L.W. Electrokinetic power generation of non-Newtonian fluids in a finite length microchannel. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2016, 20, 71. [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Kim, M.S.; Cho, Y.; Ahn, J.; Ahn, S.; Nam, J.S.; Bae, J.; Yun, T.G.; Kim, I.-D. Hydrovoltaic Electricity Generator with Hygroscopic Materials: A Review and New Perspective. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2301080. [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Duley, W.W.; Peng, P.; Xiao, M.; Feng, J.; Liu, L.; Zou, G.; Zhou, Y.N. Moisture-Enabled Electricity Generation: From Physics and Materials to Self-Powered Applications. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2003722. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.J. Foundations of Colloid Science, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2001.

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Tan, Y.; Guo, J.; Sun, Z.; Deng, X. Harvesting Electricity from Water Evaporation through Microchannels of Natural Wood. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 11232-11239. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, D.; Sun, Z.; Song, J.; Deng, X. Robust superhydrophobicity: mechanisms and strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4031-4061. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Standard Error | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.832 μA | ± 0.003 μA | Steady-state current | |

| 16.168 μA | ± 0.044 μA | Initial current peak amplitude | |

| 621.395 s | ± 1.620 s | Time constant | |

| Reduced Chi-Square | 0.293 | — | Goodness of fit measure |

| 0.934 | — | Coefficient of determination | |

| Adjusted | 0.934 | — | Adjusted coefficient of determination |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).