1. Introduction

Building a clean, low-carbon, safe, and efficient modern energy system is of great significance for promoting the transformation of energy structures and the energy revolution [

1,

2].To facilitate this transformation, the traditional energy system, which is primarily dominated by fossil fuels, must evolve into an integrated energy system centered around renewable energy sources. This new system will incorporate various forms of energy, including electricity, heat, cold, and gas [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The autonomous adjustment behavior of integrated energy users in response to energy demand is referred to as integrated demand response. Integrated demand response leverages the coupling and complementary characteristics of different energy sources to optimize the collaboration of load, energy storage devices, and energy coupling conversion equipment on the demand side, thereby enhancing the flexibility of the system's operational modes [

7]. In comparison to the demand response of a single energy source, integrated demand response further reduces demand-side energy costs and improves energy utilization efficiency [

8].

At present, there are many studies on integrated demand response. In [

9], a dynamic pricing mechanism for industrial parks considering demand response was proposed. Based on the price elasticity and floating coefficients, [

10] developed an optimal scheduling model for integrated energy systems that considers price-based demand response. [

11] comprehensively examined response characteristics and cost composition across three different time scales: day-before, day-of, and real-time, proposing an optimization strategy for integrated energy microgrid operations under multiple time scales. However, these studies on integrated demand response mechanisms primarily aimed to maximize profit or minimize operating costs for integrated energy microgrids, without addressing the impact of demand response behavior on the interests of microgrid users, making them less applicable in scenarios involving multiple stakeholders. The game theory approach effectively determines the optimal strategies for multiple stakeholders in a rational market, facilitating optimal resource allocation. Various game models, including cooperative games [

12], non-cooperative games [

13], master-slave games [

14] and evolutionary games [

15], have been increasingly applied to the optimal operation of energy systems. Among these, the master-slave game, as a type of non-cooperative game, is widely utilized to address energy pricing issues between buyers and sellers. In [

16], a master-slave game method for energy-sharing management of microgrids with photovoltaic producers and marketers was proposed. Additionally, [

17] established a distributed and coordinated optimization model for an integrated energy system featuring one master and multiple slaves, presenting a reasonable pricing strategy for electricity and heat for integrated energy operators. [

18] developed a day-master-slave game optimization scheduling model that incorporates stepped carbon trading and carbon tax. This model effectively guides the output of diverse energy supply equipment, aiming to reduce the total carbon emissions of the system while maintaining economic efficiency.

All the studies mentioned focused on a single integrated energy microgrid, without considering that multiple microgrids within the same regional distribution network can interact to form a multi-microgrid system with electrical energy exchange [

19,

20]. In [

21], aiming at multiple microgrids belonging to different stakeholders in the same region, an energy interaction framework for multi-microgrid systems was designed using multi-agent technology, and an economic optimal scheduling method for multi-microgrid systems based on a master-slave game was proposed. In [

22] a cooperative optimal scheduling strategy considering a integrated demand response and master-slave game for multi-microgrid integrated energy systems with electrical energy interactions was proposed. In [

23], an optimal scheduling strategy for multi-agent integrated energy systems based on integrated demand response and electrical energy interaction was proposed. [

24] proposed a microgrid group-master-slave game optimization method considering the pricing mechanism, which promoted energy interaction within the microgrids group, effectively improved the net load curve of the regional distribution network, and enhanced the utilization efficiency of distributed energy.

It should be noted that while most studies employing the master-slave game method to investigate the optimization of integrated energy systems in microgrids connect excess new energy to the grid to ensure complete absorption, challenges arise due to factors such as power quality and grid connection policies. These issues make it difficult for microgrids to reverse the power supply to the distribution network. The promotion of local consumption of new energy sources, such as photovoltaic energy, while balancing the interests of various stakeholders, presents a significant research challenge. Therefore, this study proposes a master-slave game operation optimization strategy for a multi-microgrid system, taking into account photovoltaic energy consumption and integrated demand response. In this framework, the multi-microgrid system acts as the leader, while each microgrid user serves as a follower, resulting in the establishment of a One-Master Multi-Slave game equilibrium model that considers the interests of both parties. It is demonstrated that the Stackelberg game yields a unique Nash equilibrium solution. Through example analysis, the optimal scheduling outcomes for each microgrid under this model are presented. Furthermore, the impact of electrical energy interaction behaviors among microgrids, electrical heating energy storage devices, the master-slave game mechanism, and integrated demand response on the economic performance and photovoltaic energy consumption of the multi-microgrid system and its users is examined, thereby validating the rationality and effectiveness of the proposed model.

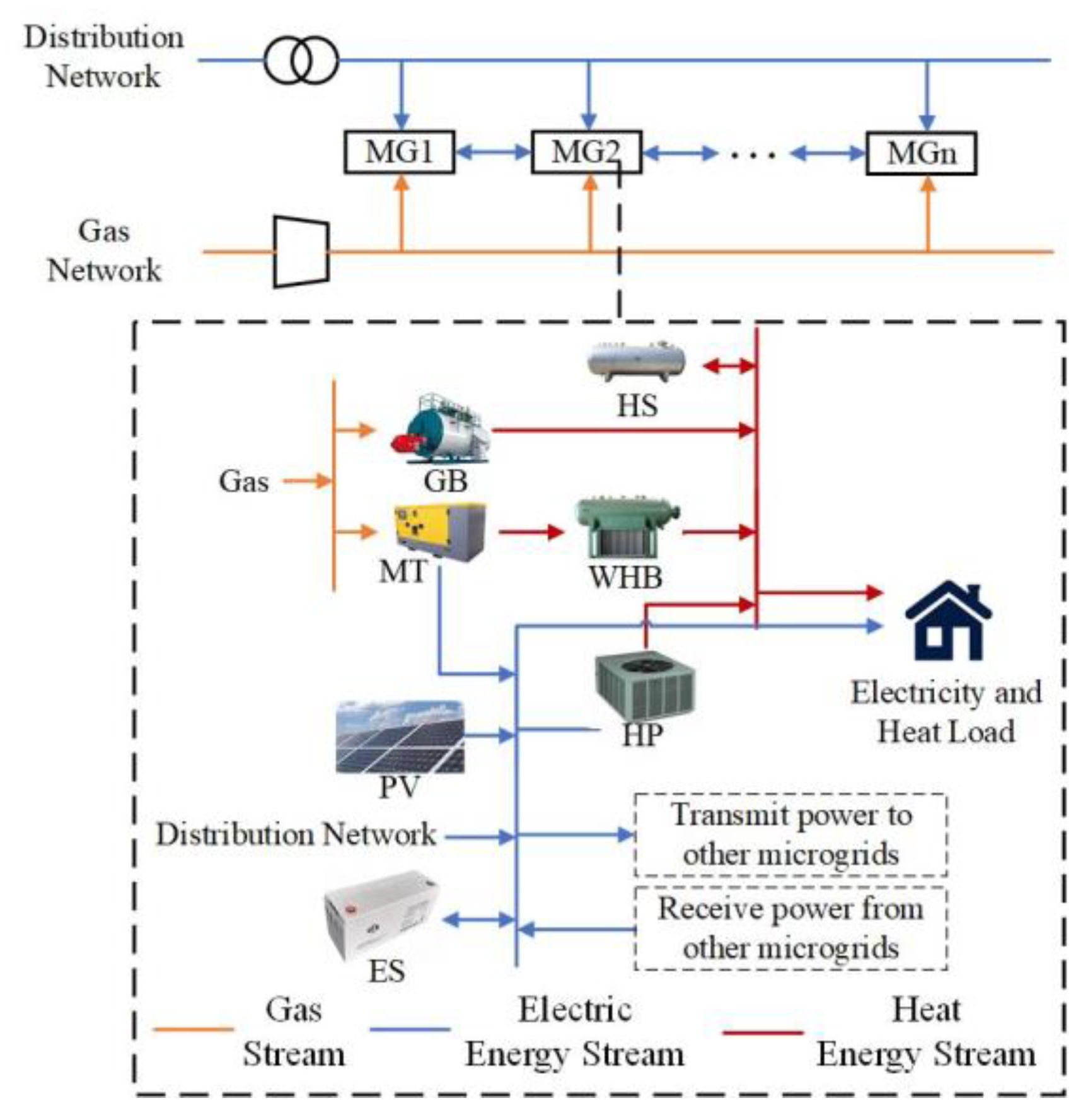

2. The Structure of the Multi-Microgrid System

This study focuses on a multi-microgrid system and a distribution network comprised of multiple integrated energy microgrids. The structural configuration of the multi-microgrid and the energy flow relationships within the microgrid are illustrated in

Figure 1. The multi-microgrid share a common interest and are coordinated uniformly by the dispatching center. The energy sources within the multi-microgrid system include photovoltaic power (PV), distribution networks, and natural gas networks. The energy coupling and conversion equipment in the microgrid consists of a micro-gas turbine (MT), gas boiler (GB), waste heat boiler (WHB), and heat pump (HP). Energy storage devices encompass both energy storage (ES) and heat storage (HS) systems. There exists a bidirectional electrical energy interaction among the microgrids. To encourage local consumption of the distributed PV, reverse power transmission from the microgrid to the distribution network is excluded from consideration.

N represents the number of microgrids under study, with a day divided into

T time periods.

2.1. Micro-Gas Turbine

As a controllable micro power supply, the MT can supply the power gap in time by burning natural gas when the photovoltaic power in the microgrid does not meet the load demand. The mathematical model is as follows:

where

is the generation power of the MT of the

microgrid at period

;

is the thermal power of the MT of the

microgrid at period

.

is the power generation efficiency coefficient of the MT and

is the thermal efficiency coefficient of the MT. The MT must satisfy the upper and lower limits of the power constraints:

where

and

are the maximum and minimum output power of the MT of the

microgrid, respectively.

The relationship between the MT output power and fuel cost is expressed as a quadratic function [

17]:

where

represents the fuel cost of the MT of the

microgrid at period

;

,

and

are the cost coefficients of the MT.

indicates the interval.

2.2. Waste Heat Boiler

The WHB collects the high-temperature flue gas discharged during the MT operation and supplies the heat load. The mathematical model is as follows:

where

is the output thermal power of the WHB of the

microgrid at period

;

is the heat recovery efficiency of the WHB;

and

are the upper and lower limits of the WHB output thermal power of the

microgrid, respectively.

2.3. Gas Boiler

When the heating of the microgrid system is insufficient, the GB can consume natural gas to supply the heat load, similar to the MT, whose fuel cost is expressed as

where

is the fuel cost of the GB of the

microgrid at period

;

is the output thermal power of the GB of the

microgrid at period

;

,

, and

are cost coefficients for the GB. The power constraint for the GB is

where

and

are the upper and lower limits of the GB output thermal power of the

microgrid, respectively.

2.4. Heat Pump

The HP can convert electrical energy into heat, and its mathematical model is as follows:

where

is the output thermal power of the HP of the

microgrid at period

;

is the input electrical power of the HP of the

microgrid at period

;

is the heating efficiency of HP;

,

are the upper and lower limits of the heating power of HP of the

microgrid, respectively.

2.5. Energy Storage

In this study, a storage battery was used for power storage and a heat storage tank was used for heat storage. The expression of electrical energy storage is

where

represents the remaining capacity of the electrical energy storage of the

microgrid at period

;

and

represent the charge and discharge power of the electrical energy storage of the

microgrid at period

, respectively; and

is the self-consumption rate of the electrical energy storage.

, and

are the charge and discharge efficiencies of the electrical energy storage, respectively.

The following constraints must be satisfied when electrical storage is running:

where

and

are the upper and lower limits of the capacity of the electrical energy storage of the

microgrid, respectively;

,

,

,

are the upper and lower limits of the charge and discharge power of the electrical energy storage of the

microgrid, respectively.

and

are the charge and discharge marks, respectively, with a value of 0 indicating outage and 1 indicating operation.

The mathematical model of thermal energy storage is similar to that of electrical energy storage, and the expressions and constraints are as follows:

where

represents the remaining capacity of thermal energy storage of the

microgrid at period

;

and

represent the charge and discharge power of thermal energy storage of the

microgrid at period

, respectively;

is the self-consumption rate of thermal energy storage.

and

are the charging and discharging efficiency of thermal energy storage, respectively.

and

are the upper and lower limits of thermal energy storage capacity of the

microgrid, respectively.

,

and

,

are the upper and lower limits of the charge and discharge power of the electrical energy storage of the

microgrid, respectively

and,

are respectively charge and discharge marks, with a value of 0 indicating outage and a value of 1 indicating operation.

The scheduling cost of energy storage is expressed as

where

,

,

and

are the charge and discharge cost coefficients of electrical and thermal energy storage, respectively.

2.6. Electricity Interaction Between Microgrids and Distribution Network

In this paper, the microgrid can purchase electricity from the distribution network at the time-of-use price when the power is insufficient, without considering the microgrid to sell electricity to the distribution network. The power purchase cost and constraint conditions of microgrid is expressed as

where

and,

are the power purchase cost and power purchased from the distribution network of the

microgrid at period

, respectively;

is the time-of-use price;

and

represent the upper and lower limits of the electricity purchased from distribution of the

microgrid at period

, respectively.

2.7. Electricity Interaction Between Microgrids

Bidirectional electrical energy interaction can be carried out between microgrids. Suppose the interaction power between the

microgrid and the

microgrid at period

is

, and the value of

is positive, indicating that the power flows from the

microgrid to the

microgrid, and the value is negative, indicating that the power flows from the

microgrid to the

microgrid. The power interaction constraint between microgrids is

where

is the upper limit of power interaction between the

microgrid and the

microgrid.

2.8. Load Model of Consumers

The electrical load and thermal load of microgrid users can be expressed as

Where

and,

are the fixed electrical load and fixed thermal load of the

microgrid at period

, respectively;

is transferable electrical load;

can reduce the heat load. Among these, fixed electrical load and fixed heat load refer to the minimum demand for electricity and heat required by microgrid users. In contrast, transferable electrical load and reducible heat load can be independently adjusted by users based on price information. The constraints are as follows:

where

and

are the maximum adjustable proportions of transferable electrical load and heat load that can be reduced in any period, respectively;

is the total transferable electrical load in

T periods, and the total transferable electrical load must remain unchanged before and after the demand response.

2.9. Constraint of Power Balance

Suppose the PV power of the

microgrid at period

is

and the unconsumed electrical power is

. Then the electrical power balance constraint is

The thermal power balance constraint is

3. Master-slave Game Optimization Scheduling Considering Integrated Demand Response

3.1. Pricing Model

The pricing strategy of the multi-microgrid system is based on the consideration of the users’ load demand. The heat sale price and electricity sale price formulated by the multi-microgrid system are

and

, respectively. The on-grid price and the time-share price are

and

, respectively. The upper and lower limits of the heat sale price are

and

, respectively. The average price ceiling of the power sale and heat sale price is

and

, respectively. The energy sale price must meet the following constraints:

3.2. Multi-Microgrid System Income Model

The objective function of the multi-microgrid system is expressed as

where,

,

and,

are calculated by the formula (3), (6), (22) and (23), respectively;

is the sales income of the

microgrid at period

, and the expression is

is the photovoltaic curtailment cost of the

microgrid at period

, and the expression is

where

is the unit cost of photovoltaic curtailment.

3.3. User Revenue Model

The user objective function of each microgrid is benefit maximization, expressed as

In the formula,

is the energy utility function of the

microgrid at period

, and the expression is

where

,

,

,

are the energy use preference coefficients of electrical energy and heat energy of the

microgrid, respectively.

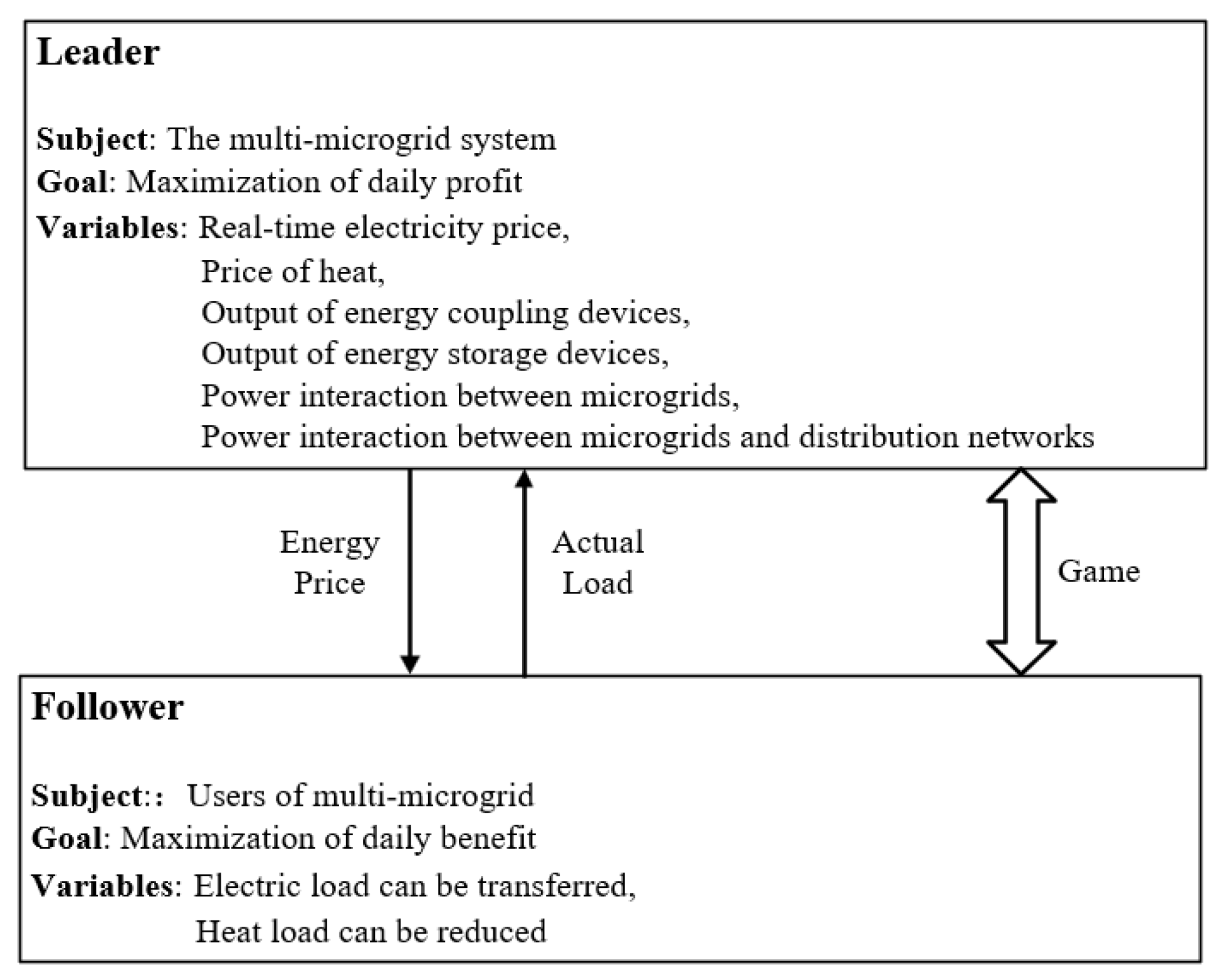

3.4. Master-Slave Game Operation Strategy

In this paper, a master-slave game model is established that feature a multi-microgrid system as the leader and individual microgrid users as followers. The game interaction mechanism is illustrated in

Figure 2. As the leader of the multi-microgrid system, its objective is to maximize total daily profit. The strategies employed by the leader include determining the selling price of energy, managing the output of energy coupling conversion equipment, and controlling energy storage devices within each microgrid, as well as the power interaction value. In contrast, each microgrid user, as a follower, aims to maximize their daily benefits, employing strategies that involve reducing and transferring various loads as part of a integrated demand response. Within this master-slave game framework, the leader enjoys a positional advantage, allowing it to seize the first opportunity in the game, while the followers must respond to the leader's actions. The multi-microgrid system is optimized to enhance profit, and the resulting optimized price signal is communicated to each microgrid user. Upon receiving this price signal, each microgrid user optimizes their response with the goal of maximizing their benefits and subsequently returns their load demand to the multi-microgrid system.

The model solving process can be divided into two interrelated stages.

Stage 1: The multi-microgrid system is optimized with the objective of maximizing profit, resulting in an energy price that is formulated based on the optimization outcomes and subsequently communicated to each load aggregator.

Stage 2: Each load aggregator conducts a integrated demand response in accordance with the energy price published by the integrated energy system operator. They aim to minimize energy usage costs, ascertain the actual load demand, and report this information back to the integrated energy system operator.

3.5. Master-Slave Game Equilibrium

When the Stackelberg game reaches Nash equilibrium, neither player can increase their benefits by unilaterally changing their strategy. Before addressing the problem, it is essential to demonstrate that the Stackelberg game possesses a unique Nash equilibrium solution. The necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of a unique Nash equilibrium solution in the Stackelberg game are outlined as follows. [

22]:

The objective function of the players in the game is a non-empty, continuous function defined over their strategy set.

The objective function of the follower is a continuous concave or convex function of its policy set.

The Stackelberg unique Nash equilibrium solution of the master-slave game model proposed in this paper is proved as follows:

- 3.

Multi-microgrid system is the leader. The policy set is {, , , ,, , , , , , , }, each microgrid user is the follower, and the policy set is {, }. The constraints on the above variables are linear equality constraints or linear inequality constraints, so the policy set of each participant is non-empty and continuous.

- 4.

Let the multi-microgrid user objective function

find the second-order partial derivative of

and

, and we can get:

Since

and

in the formula are always positive, therefore:

Take the cross partial of the function , and the result is 0. Therefore, the Hessian matrix of the follower is negative definite, and its objective function is a continuous convex function of its policy set. The master-slave game model proposed in this paper has a unique Nash equilibrium solution.

4. Case Analysis

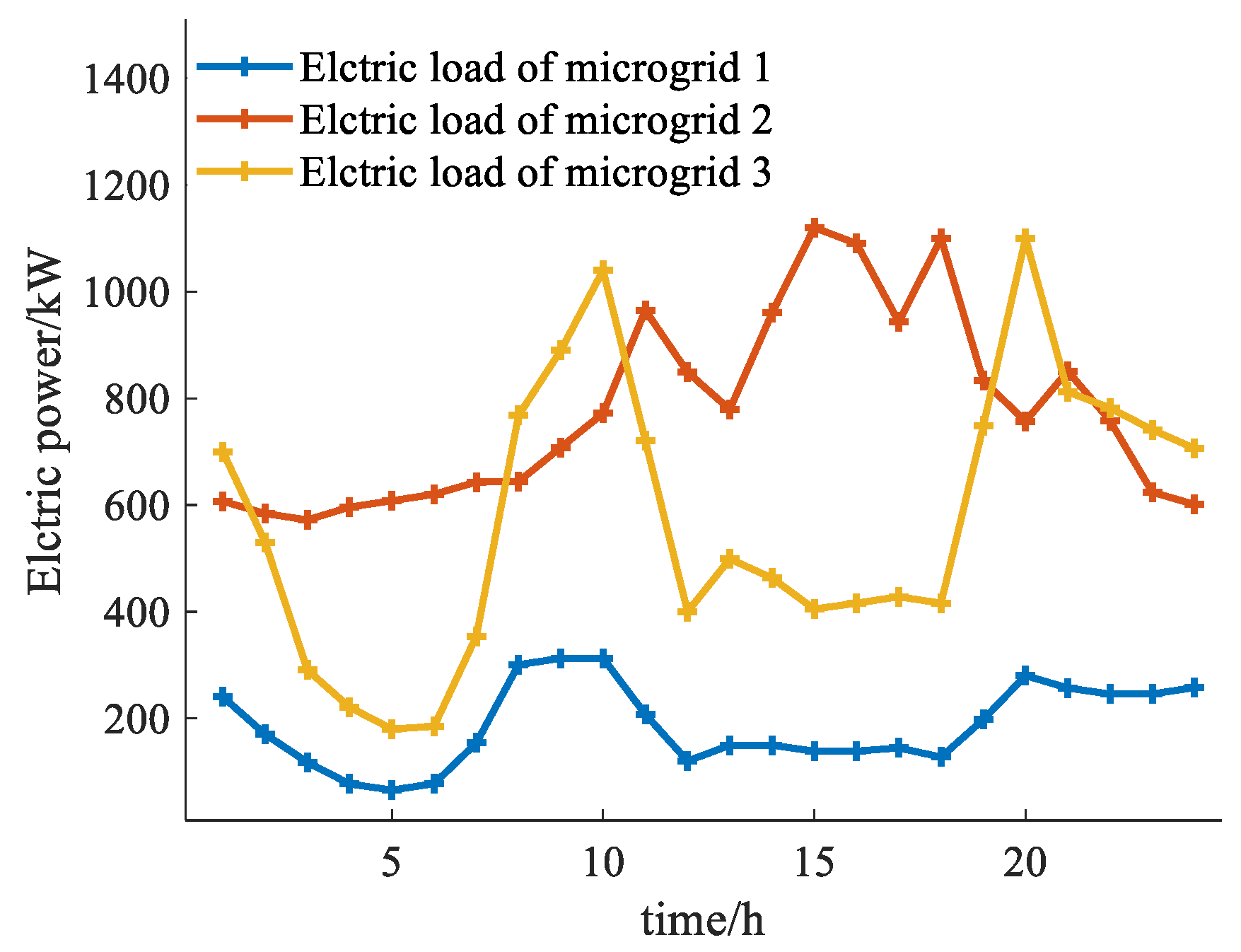

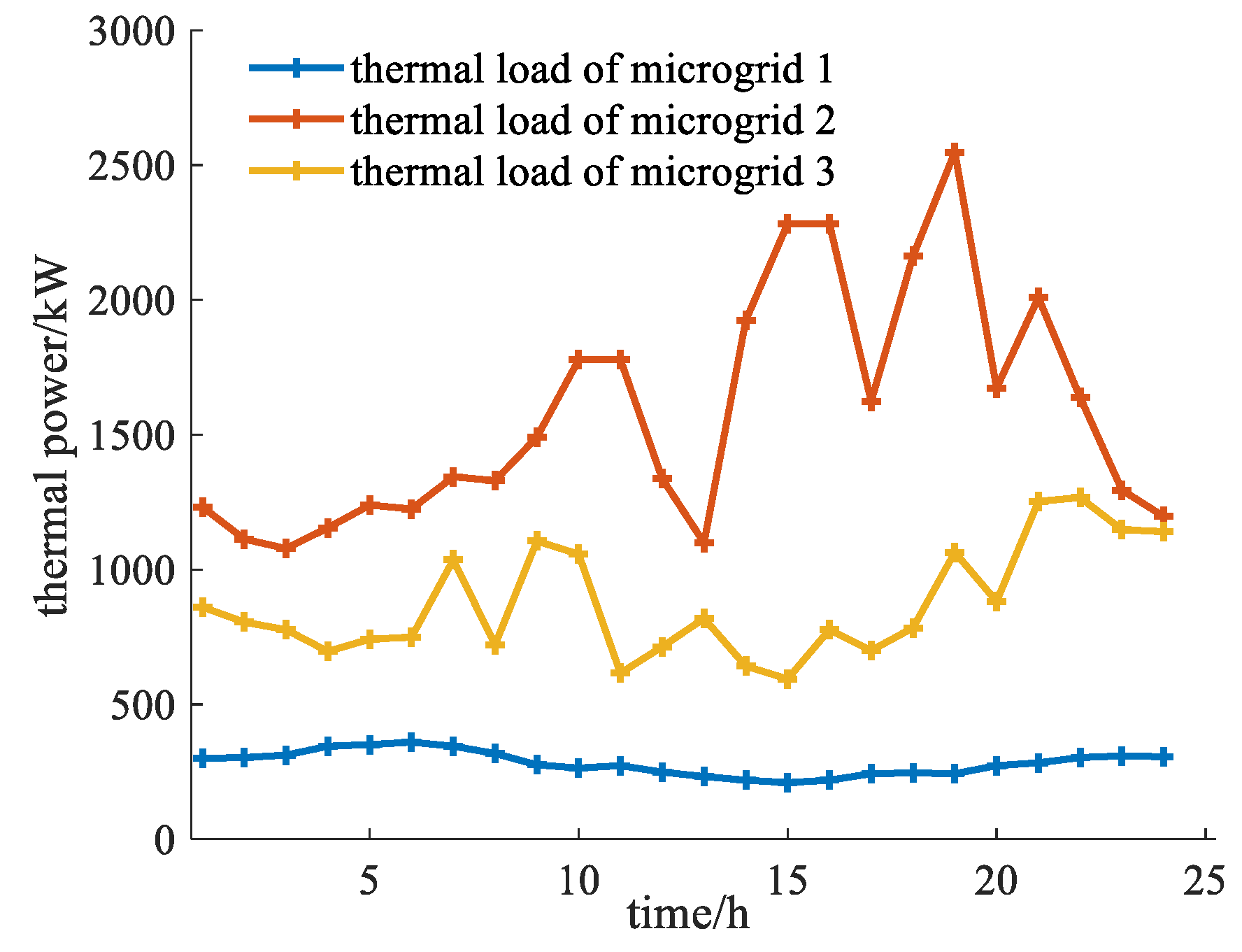

4.1. Base Data

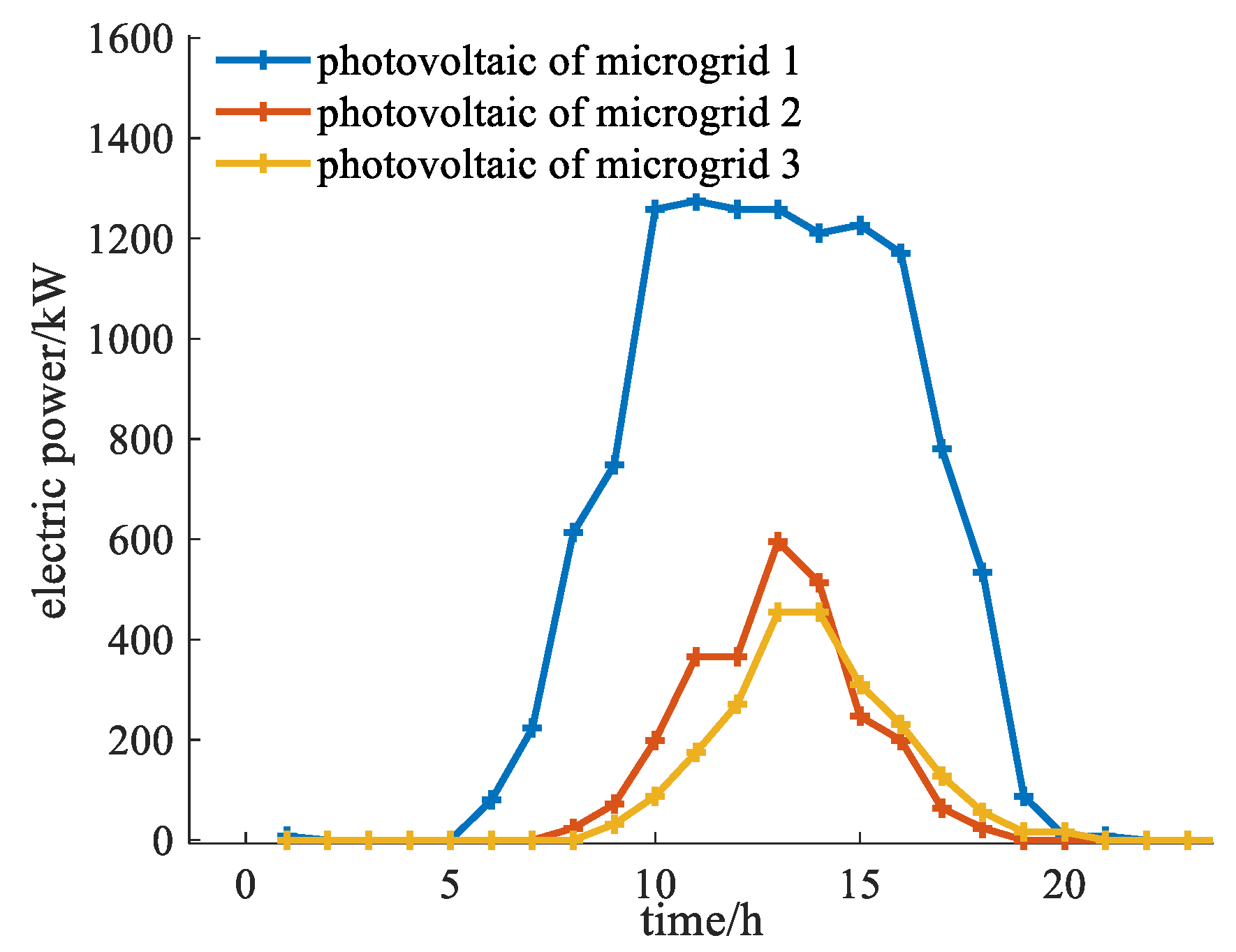

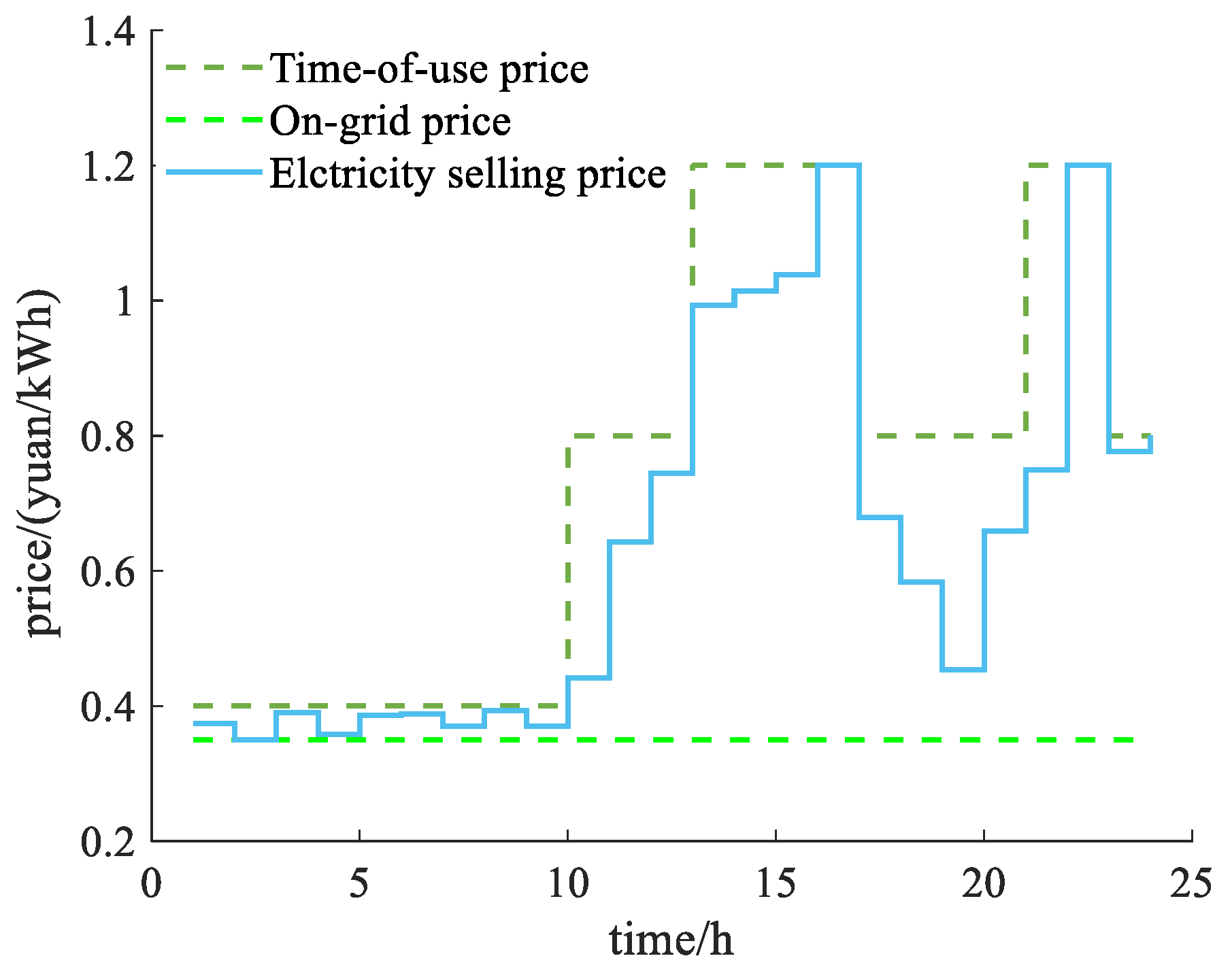

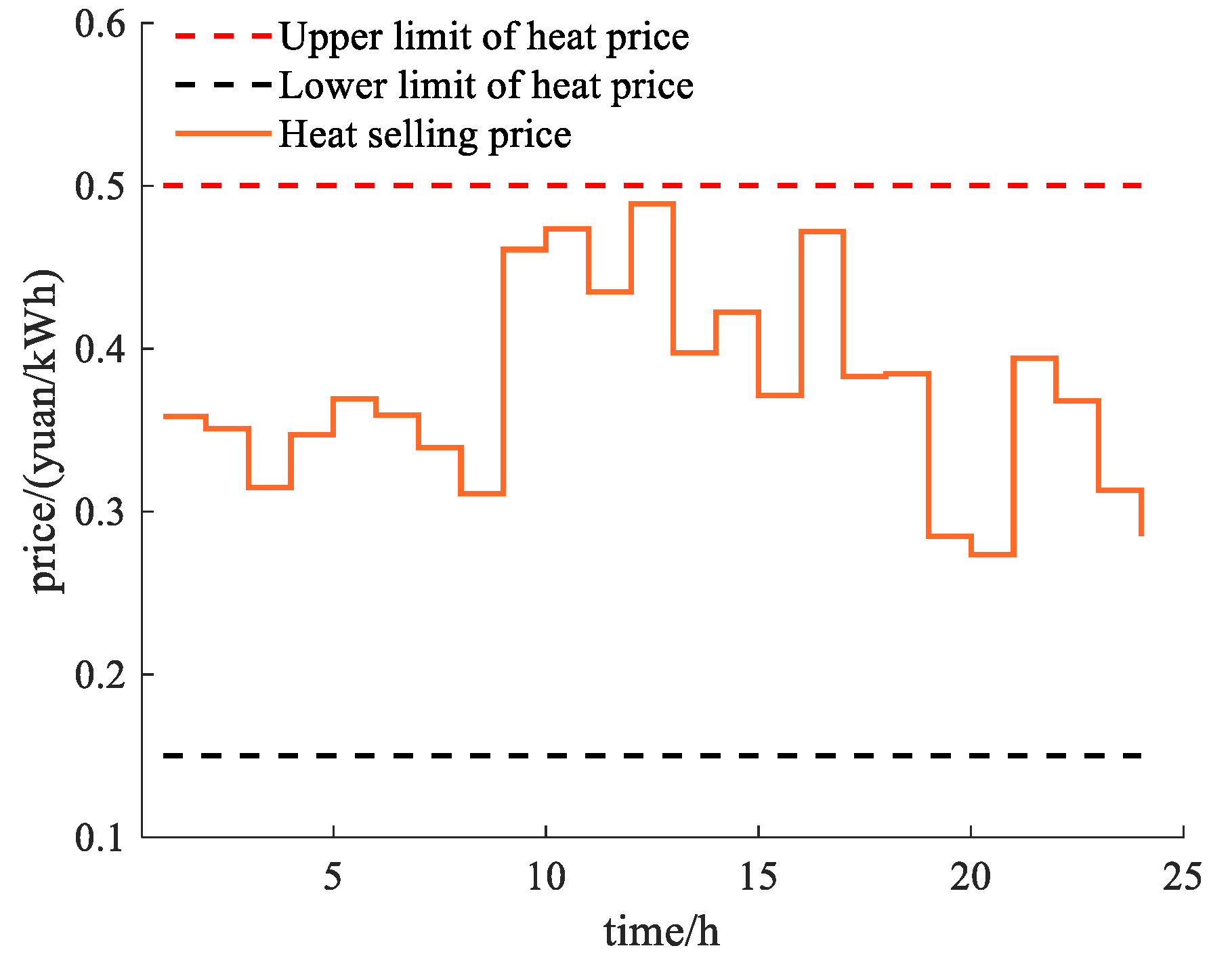

This study considers a multi-microgrid system comprising three distinct microgrids, which will be simulated and analyzed based on the proposed model. The analysis divides a day into 24 periods. The user can translate the electrical load, accounting for 20% of the total electrical load, while the maximum allowable translation of the electrical load in each period is capped at 30% of the current electrical load. Additionally, the heat load can be reduced by up to 20% of the total heat load. Each microgrid starts with an initial capacity of 500 kWh for the electrical energy storage device and 1000 kWh for the thermal energy storage device. The time-of-use electricity price and the feed-in price of the distribution network are referenced from [

17] and illustrated in

Figure 3. The heat price is bounded by an upper limit of 0.50 yuan/kWh and a lower limit of 0.15 yuan/kWh. Furthermore, the upper limit for the average selling price of power is set at 0.8 yuan/kWh, while the upper limit for the average selling price of heat is 0.45 yuan/kWh. The maximum power exchange between microgrids is restricted to 500 kW/h, and the maximum power purchase from microgrids to the distribution network is limited to 1000 kW/h. The user’s energy consumption preference coefficients are 1.8, 1.4, 0.0006, and 0.0005, respectively. The cost associated with unit photovoltaic curtailment is 0.5 yuan/kWh. For the purposes of this analysis, energy transmission losses are disregarded. The electrical heating load curve and photovoltaic output for each microgrid are presented in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, while the parameters for the MT, WHB, GB, and other devices in each microgrid are detailed in

Table 1.

4.2. Iterative Calculation Result

After iterative calculations, the optimization process converges by the 15th iteration. The optimization results for key nodes during the iterative process are presented in

Table 2. The direction and rate of iterative convergence are influenced by the selection of initial values. As the number of iterations increases, the profits of the multi-microgrid system gradually rise, while the benefits for the microgrid users gradually decline. This phenomenon illustrates the interactive dynamics between the two entities, highlighting the multi-microgrid system's dominant position as the game leader. Ultimately, the master-slave game reaches a Nash equilibrium point, beyond which no player can alter their strategy to achieve greater benefits. At this equilibrium, the profit of the multi-microgrid system stabilizes at 27,010 yuan, while the user benefits from the three microgrids stabilize at 10,670 yuan, 20,690 yuan, and 22,423 yuan, respectively.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 depict the final prices of electricity and heat sold to users by the multi-microgrid system. The multi-microgrid system develops a pricing strategy within a specified range to offer more favorable electricity prices and reasonable heat prices to the energy users compared to the traditional power grid.

Table 2.

Iterative solution procedure.

Table 2.

Iterative solution procedure.

| Iterations |

The multi-microgrid system profit/yuan |

Benefits of microgrid 1/yuan |

Benefits of microgrid 2/yuan |

Benefits of microgrid 3/yuan |

Total benefits/yuan |

| 7 |

23799 |

12038 |

23357 |

24789 |

60184 |

| 13 |

26500 |

10926 |

21032 |

22671 |

54629 |

| 15 |

27010 |

10670 |

20690 |

22423 |

53392 |

| 20 |

27010 |

10670 |

20690 |

22423 |

53392 |

4.3. Optimal Scheduling Result

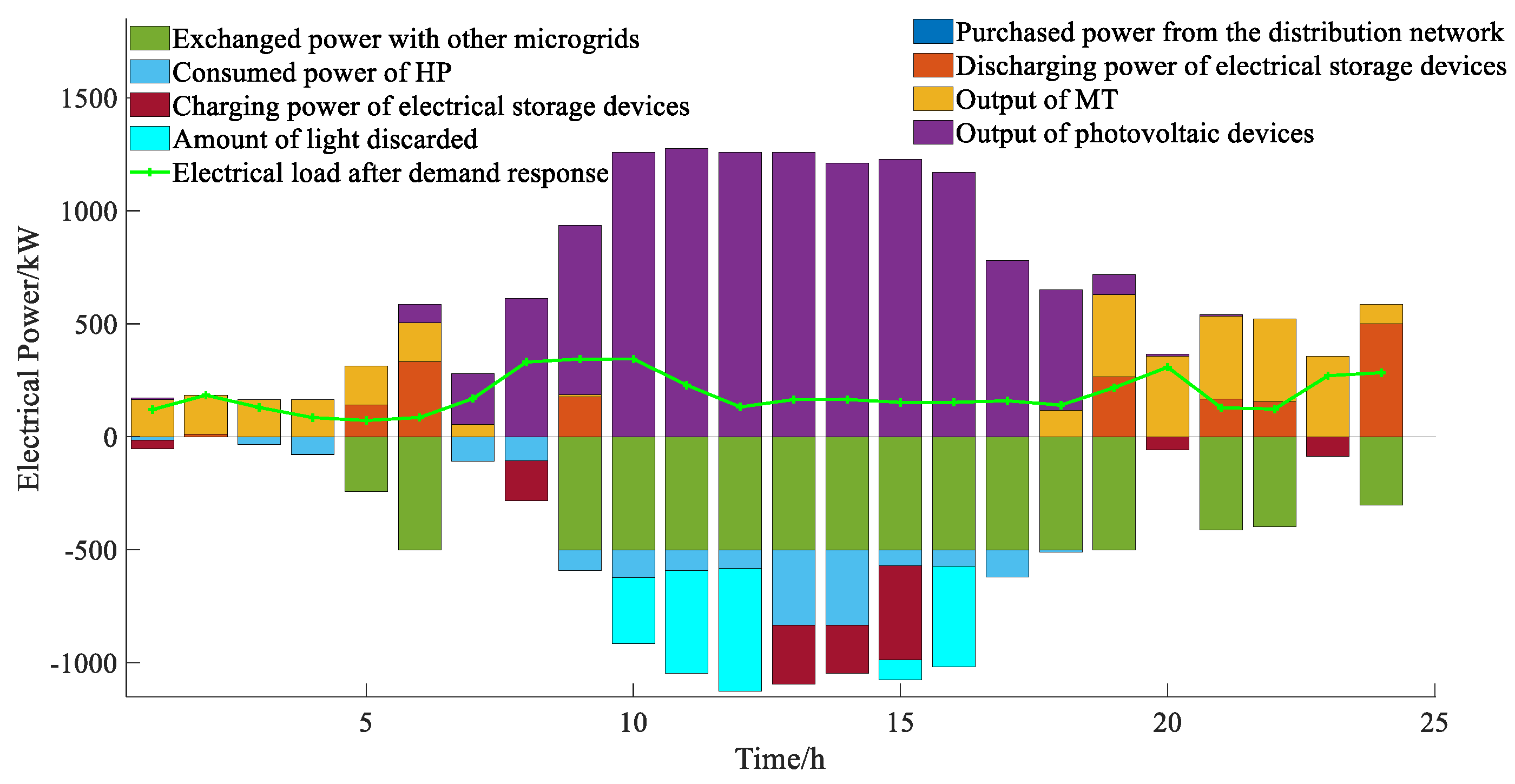

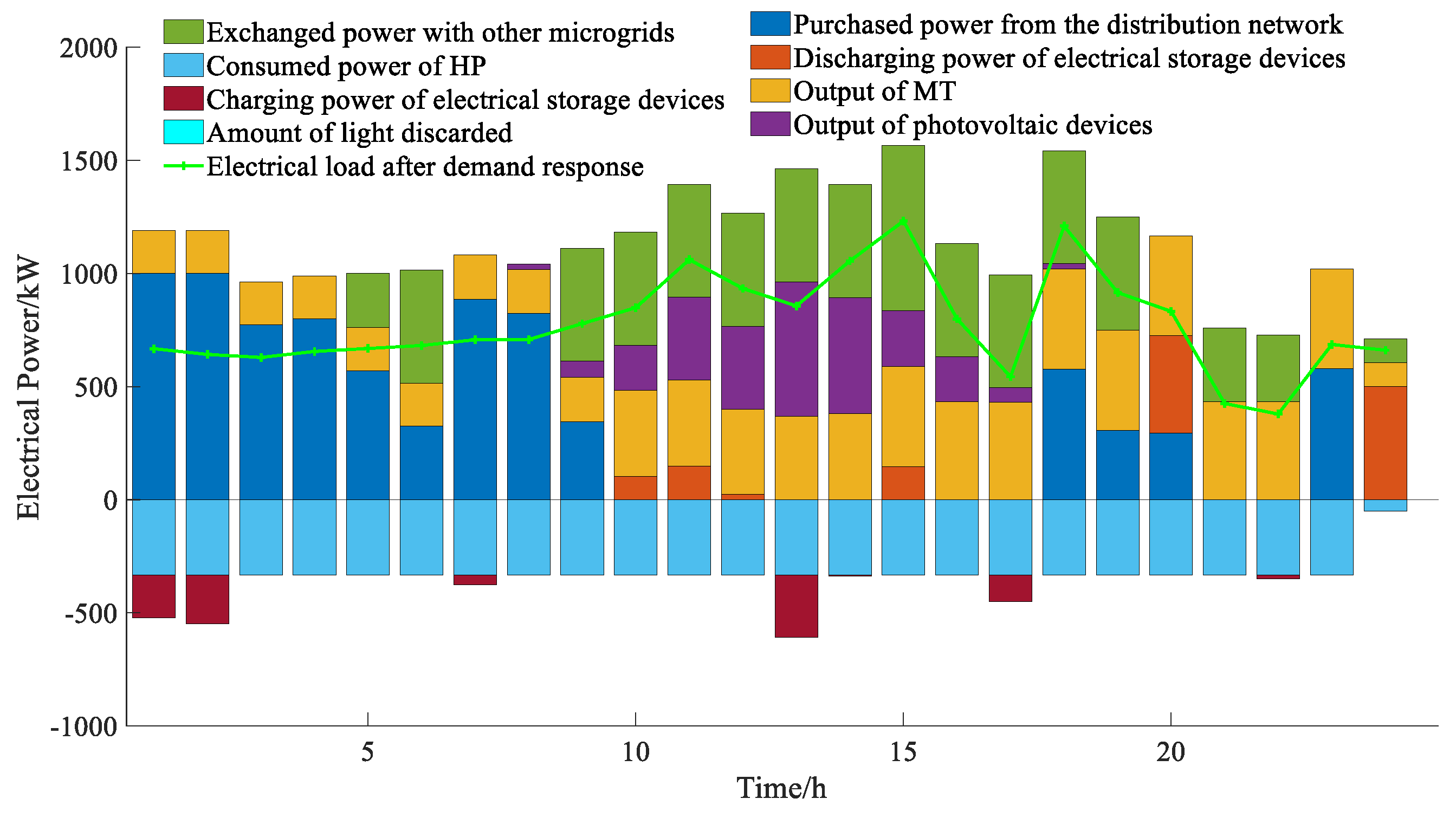

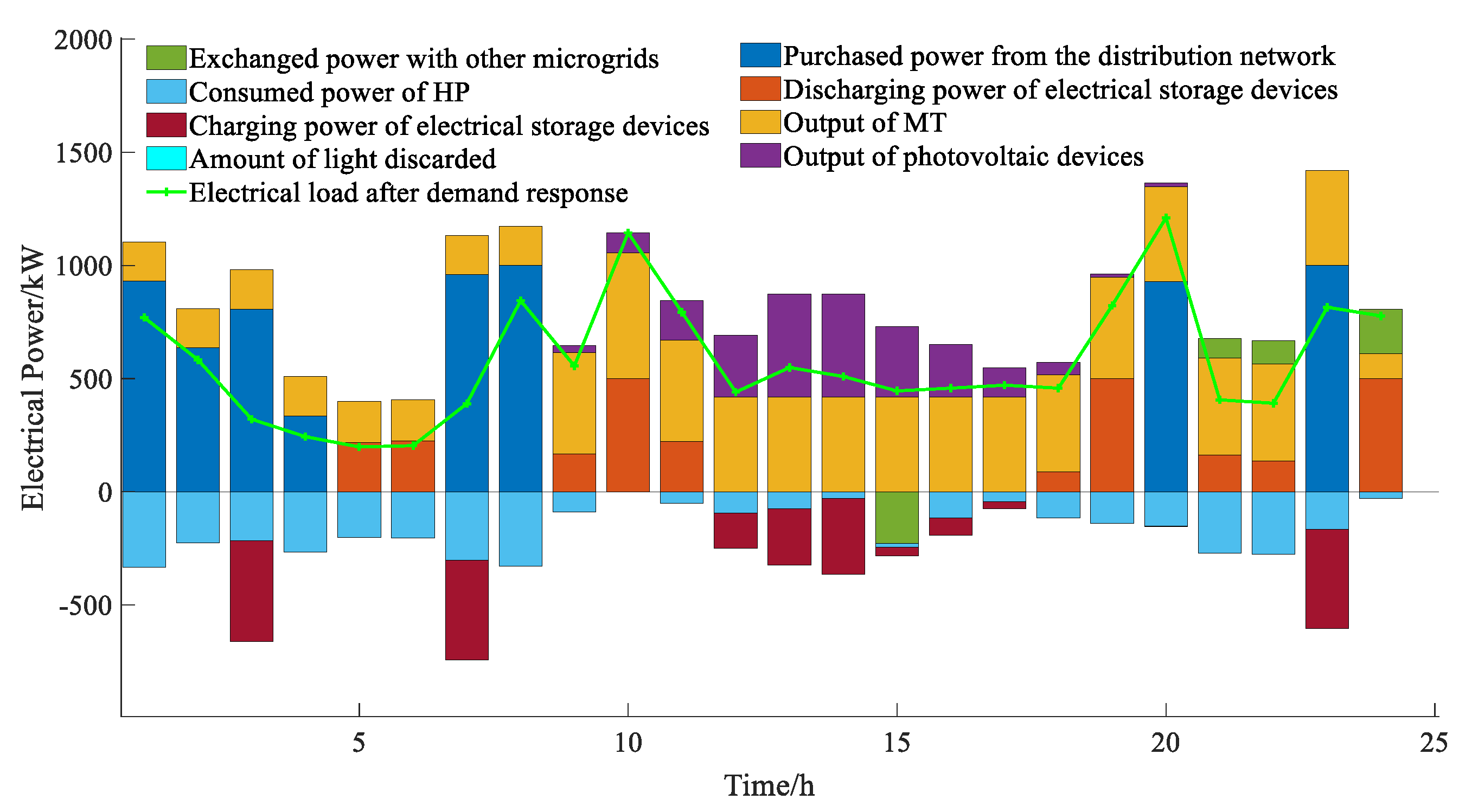

The optimization results of the electrical power balance for each microgrid within the multi-microgrid system are presented in

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

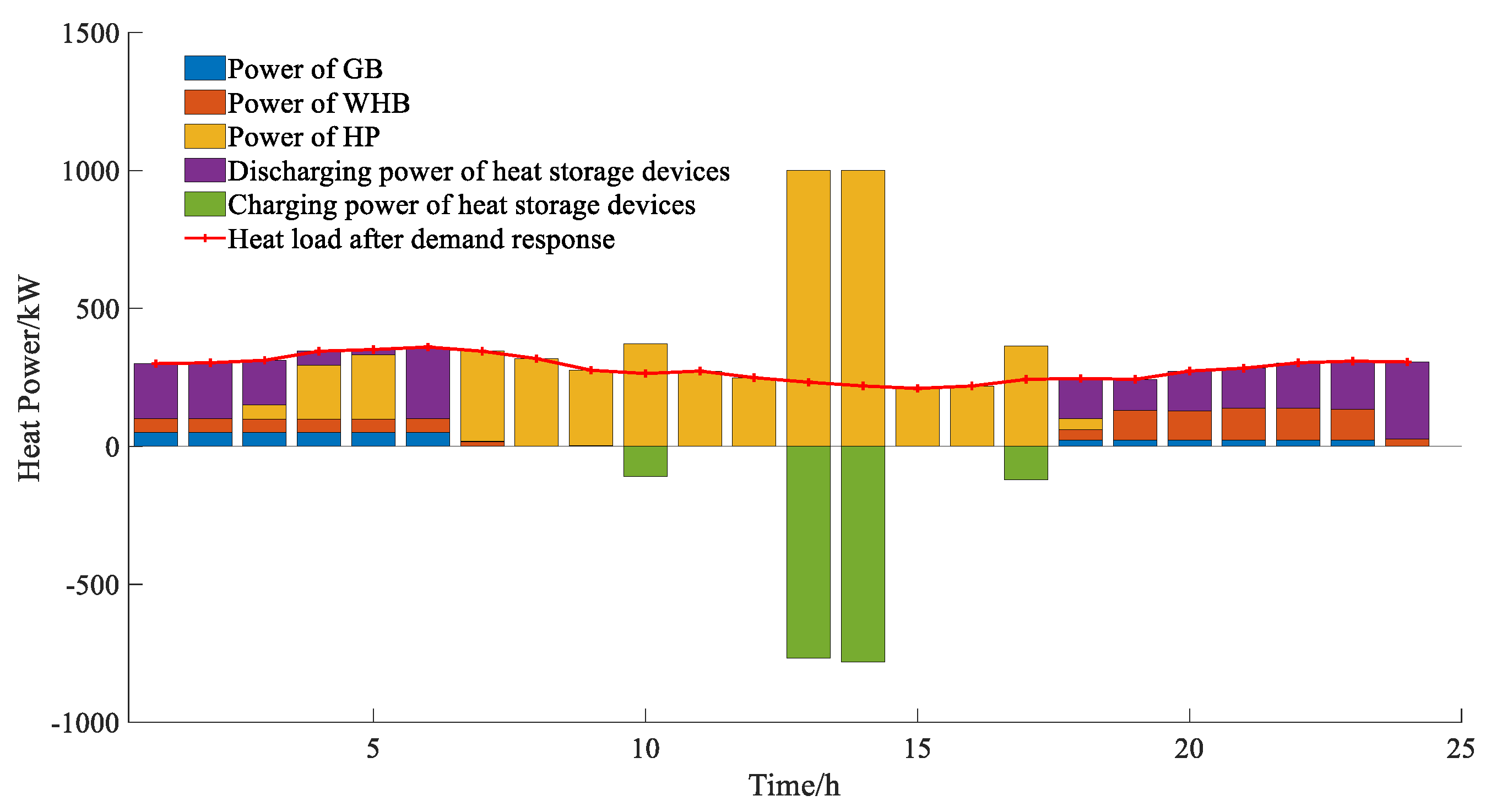

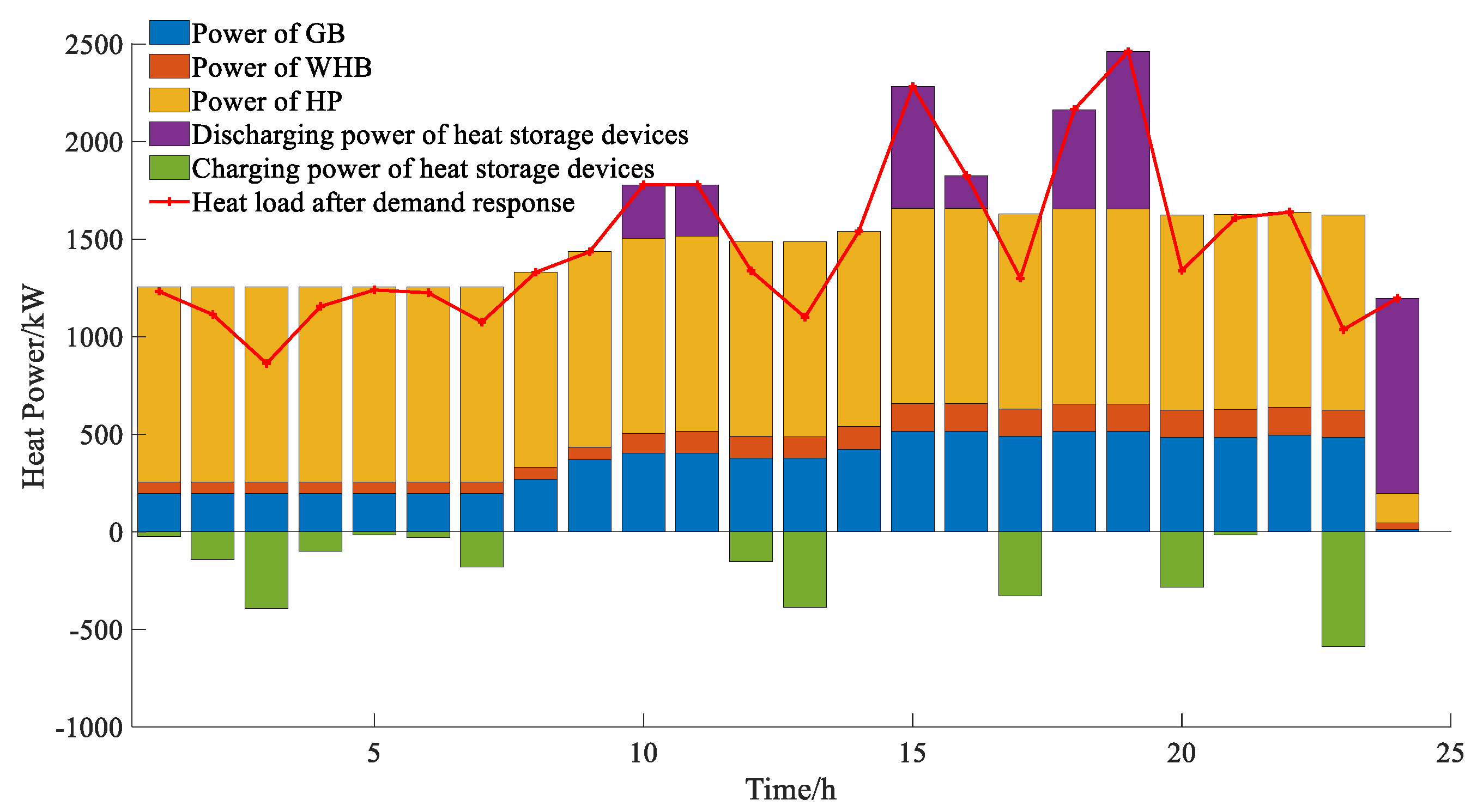

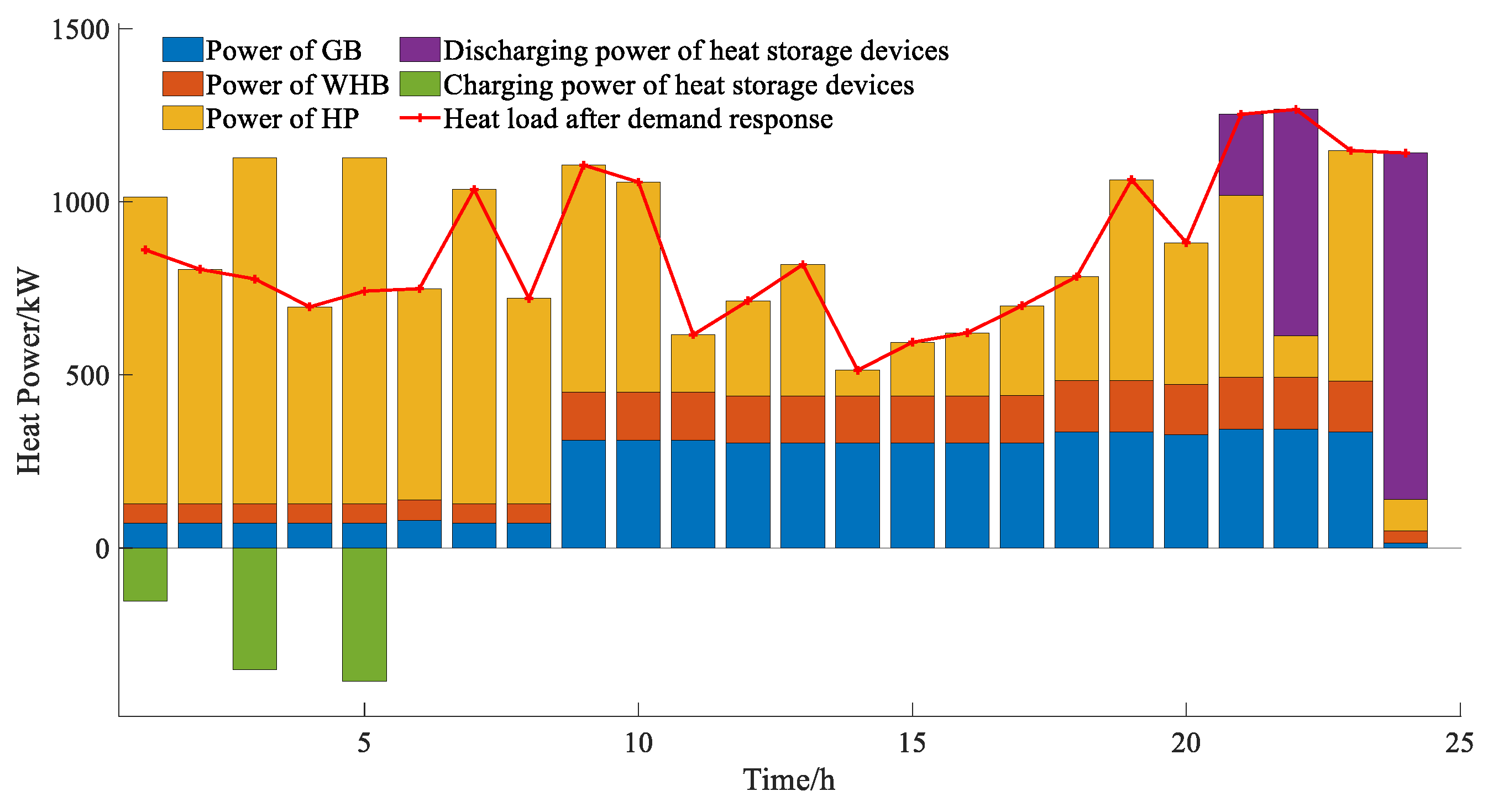

Figure 10 while the optimization results for the thermal power balance are presented in

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

As shown in

Figure 8, microgrid 1 operates as a residual microgrid characterized by a high photovoltaic output and a low load level. Between 8:00 and 18:00, the photovoltaic power output in microgrid 1 exceeds the electrical load, leading to the surplus photovoltaic power being utilized to supply other microgrids and charge electrical energy storage. However, due to the constraints on power transmission and the capacity of electrical energy storage between microgrids, some photovoltaic power remains unutilized, resulting in curtailment. During nighttime, when photovoltaic output is absent, microgrid 1 primarily satisfies electrical load demands through the discharge of electrical energy storage and the output from a micro gas turbine. The output power and fuel cost of the micro gas turbine are represented as a quadratic function; thus, at lower output power levels, the unit generation cost is minimized. Consequently, the power generation cost of the micro gas turbine in microgrid 1 is lower than that of the external distribution network, which explains why microgrid 1 does not supply electricity to the distribution network. It can be seen from

Figure 11 indicates that thermal energy storage peaks between 13:00 and 14:00, with energy being discharged during the remaining periods to meet thermal load demands. This observation, in conjunction with

Figure 8, illustrates that the photovoltaic output during this timeframe significantly surpasses electrical load, allowing for excess electrical energy to be utilized for heat pumps and stored in thermal energy storage. This reflects the coupling and complementary characteristics of electricity and heat.

As shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, the electrical load of microgrid 2 and microgrid 3 consistently exceeds the photovoltaic output, indicating that photovoltaic power can be fully utilized and highlighting their status as power-deficient microgrids. Notably, the power deficit in microgrid 2 is more pronounced than that in microgrid 3. Consequently, microgrid 2 acquires a substantial amount of electrical power and does not supply electricity to other microgrids, whereas the electrical energy exchange between microgrid 3 and other microgrids remains minimal. During the periods of 1:00-9:00, 18:00-20:00, and 23:00, microgrid 2 purchases electricity from the distribution network. An analysis of the time-of-use electricity price curve, as depicted in

Figure 6, reveals that the electricity prices during these intervals are low, coinciding with either negligible or very low photovoltaic power output. Thus, centralized power purchases during these times effectively reduce overall power acquisition costs and mitigate excessive output from micro-gas turbines, leading to fuel cost savings. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 12 , heat pumps constitute a significant portion of heat supply in microgrid 2, whereas gas boilers and waste heat boilers contribute a substantially smaller share. This disparity can be attributed to the superior energy conversion efficiency of heat pumps. When the unit power generation cost for the microgrid is relatively low, it becomes more economically viable to convert electrical energy into thermal energy using heat pumps. Additionally, Figures 10 and

Figure 13 reveal that microgrid 3 adopts a similar strategy, opting for centralized power purchases during periods characterized by low time-of-use prices, minimal photovoltaic output, and high load, while also transferring power to heat in significant quantities via heat pumps to enhance economic efficiency.

4.4. Option Comparison

To verify the rationality of the optimization strategy presented in this paper, the following four schemes are established:

Scheme 1: This scheme adopts the optimization strategy outlined in this paper, taking into account the electrical energy interactions within the multi-microgrid system, the electrical and heat energy storage devices, as well as the users' integrated demand response.

Scheme 2: An independent optimization calculation is conducted for each microgrid, without considering the electrical energy interaction among them.

Scheme 3: This scheme excludes the consideration of electrical and heat energy storage devices in each microgrid, resulting in no energy storage scheduling costs for the multi-microgrid system.

Scheme 4: The integrated demand response behavior of microgrid users is disregarded. In this case, there is no master-slave game relationship, no iterative solution is required, and the energy prices, along with the fixed electrical and heat loads established in Scheme 1, are utilized for a single optimization calculation.

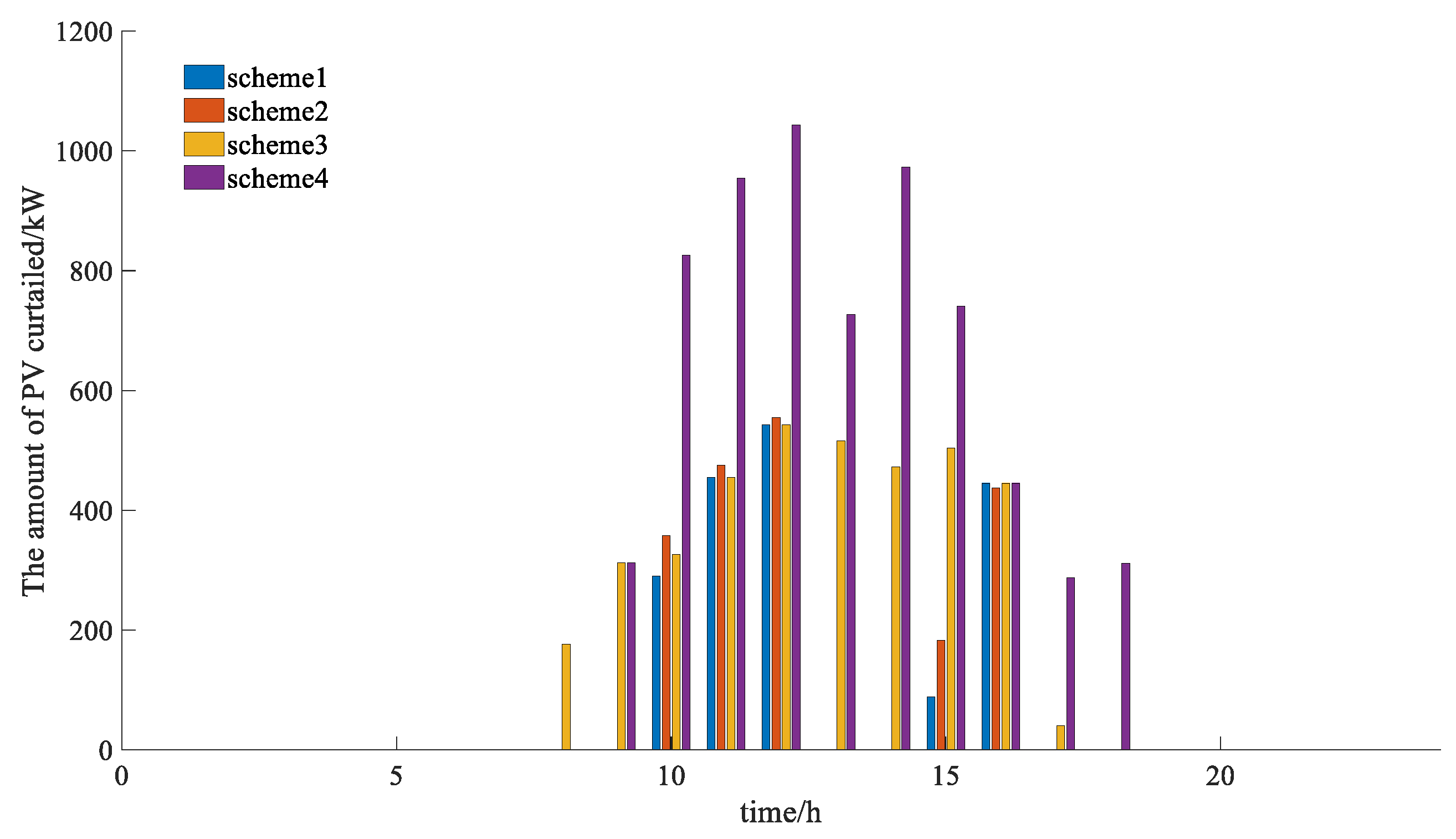

The optimization results for the four schemes are presented, including the multi-microgrid system's profit, sales income, energy supply cost, and total user benefits, as shown in

Table 3. Additionally,

Figure 14 illustrates the amount of photovoltaic discarded by the multi-microgrid system during each period across the four schemes, with a comparison made against Scheme 1.

In comparison to Scheme 2, Scheme 1 enhances the electrical energy interaction among multiple microgrids. As illustrated in

Figure 14, the increased power interaction significantly reduces the amount of photovoltaic wasted by the multi-microgrid system. This is primarily because Microgrid 1 in Scheme 1 can transmit excess power externally during the photovoltaic excess period from 08:00 to 18:00, thereby promoting photovoltaic absorption. In contrast, Scheme 2 relies solely on the energy storage system, resulting in only a modest absorption effect. As shown in

Table 3, following the enhancement of power interaction, the energy sales income of the multi-microgrid system increased by 73 yuan, while the energy supply cost decreased by 6,540 yuan, thus substantially boosting profitability. This improvement occurs because, under conditions where the load volume remains relatively stable, the power exchange between microgrids reduces the costs associated with optical curtailment, the MT generation capacity, and electricity purchased from the distribution network, thereby lowering the energy supply cost. Concurrently, the overall user benefit also increased by 610 yuan, achieving a multi-win scenario for both the multi-microgrid system and its individual users.

When compared to Scheme 3, Scheme 1 incorporates electric energy storage devices and heat energy storage devices within each microgrid. These energy storage devices contribute to an increase in the profit of the multi-microgrid system by 4,688 yuan through heightened sales income and reduced energy supply costs, while user benefits rise by 1,158 yuan. As evidenced by

Figure 8 and

Figure 14, the implementation of Scheme 1 from 13:00 to 15:00 significantly diminishes the amount of discarded photovoltaic, primarily because Microgrid 1 charges the energy storage during this timeframe to absorb excess photovoltaic output.

In comparison to Scheme 1 and Scheme 4, and taking into account users' integrated demand response and the master-slave game mechanism, the sales income of the multi-microgrid system decreases by 289 yuan. However, the energy supply cost is reduced by 2020 yuan, resulting in an overall profit increase of 1732 yuan. Additionally, total user benefits rise by 3765 yuan, indicating a significant enhancement. This improvement is attributed to users optimizing their self-load in response to price signals, thereby pursuing greater energy efficiency. As illustrated in

Figure 14, the integrated demand response mechanism also leads to a slight reduction in the amount of photovoltaic discarded.

In summary, the interactions between microgrids, the utilization of energy storage devices, the implementation of the master-slave game, and the integrated demand response mechanism collectively enhance the profits and total user benefits of the multi-microgrid system, while also promoting the consumption of photovoltaic energy.

5. Conclusions

This paper establishes an operational model for multi-microgrid systems and proposes a master-slave game optimization strategy that takes into account photovoltaic consumption and integrated demand response. A master-slave game interactive equilibrium model is formulated, wherein the multi-microgrid system acts as the leader and each microgrid user functions as a follower. The existence of a unique Nash equilibrium solution within the Stackelberg game framework is demonstrated. Finally, through example analysis, a reasonable selling price and scheduling strategy are developed, which show that the proposed strategy effectively balances the interests of both the multi-microgrid system and individual microgrid users, while promoting PV consumption. Future work should address energy transmission losses and the variability in new energy output. Additionally, the energy pricing strategy and benefit distribution methods warrant further investigation, particularly as the interaction modes among stakeholders become more complex.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and Y.X.; methodology, S.J. and X.Q.; investigation, J.L. and Y.L.; writing, J.L. and H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid JiangSu Electric Power Company Limited (J2023103).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ming, Z.; Yingxin, L.; Pengcheng, Z.; Yuqing, W.; Mengxi, H. Review and Prospects of Integrated Energy System Modeling and Benefit Evaluation. Power System Technology 2018, 42, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, L.; Dong, L.; Danyang, Y. Analysis and Reflection on the Development of Power System Towards the Goal of Carbon Emission Peak and Carbon Neutrality. Proceedings of the CSEE 2021, 41, 6245–6259. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Dewen, L.; Xin, S.; Gang, W.; Pinqin, L.; Zhao, L. Review of Research on Optimal Operation Technology of Integrated Energy System. Electric Power Construction 2022, 43, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoyun, Q.; Ming, W.; Qi, L.; Baodi, D.; Fengzhan, Z.; Lingfeng, K. Review on Comprehensive Evaluation of Multi-energy Complementary Integrated Energy systems. Electric Power 2021, 54, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaodan, Y.; Xiandong, X.; Shuoyi, C.; Jianzhong, W.; Hongjie, J. A Brief Review to Integrated Energy System and Energy Internet. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society 2016, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yiwei, M.; Ping, Y.; Yuewu, W.; Zhouli, Z. Typical Characteristics and Key Technologies of Microgrid. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2015, 39, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Hongbin, S.; Qinglai, G. Review and Prospect of Integrated Demand Response. Proceedings of the CSEE 2018, 38, 7194–7205. [Google Scholar]

- Shaofeng, F.; Renjun, Z.; Fulu, X.; Jian, F.; Yuanlin, C.; Bin, L. Optimal Operation of Integrated Energy System for Park Micro-grid Considering Comprehensive Demand Response of Power and Thermal Loads. Proceedings of the CSU-EPSA 2020, 32, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Longkun, W.; Zhanbo, X.; Xiaoyi, Q.; Xiaohong, G. Dynamic Pricing and Prices Spike Detection for Industrial Park with Coupled Electricity and Thermal Demand. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2022, 19, 1326–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Mingyuan, W.; Ruiqi, W.; Jiyan, L.; Wenjie, J.; Qi, Z.; Guiqing, Z.; Ming, W. Operation Optimization for Park with Integrated Energy System Based on Integrated Demand Response. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Fan, Z.; Xiyuan, M.; Senjing, Y.; Zhuolin, Z.; Ping, Y.; Zhuoli, Z.; Chun, L.S.; Loi, L.L. Multi-time Scale Economic Optimization Dispatch of the Park Integrated Energy System. Frontiers in Energy Research 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, H.; Qian, A.; Ziqing, J. Bi-level Game Strategy for Muti-agent with Incomplete Information in Regional Integrated Energy System. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2018, 42, 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kaijun, L.; Junyong, W.; Liangliang, H.; Di, L.; Dezhi, L.; Huaguang, Y. Optimization of Operation Strategy for Micro-energy Grid with CCHP Systems Based on Non-cooperative Game. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2018, 42, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Nian, L.; Jianhua, Z.; Cheng, W.; Hou, M. Distributed Energy Management of Community Energy Internet Based on Leader-fol- Lowers Game. Power System Technology 2016, 40, 3655–3662. [Google Scholar]

- Yigang, Z.; Xiaojun, W.; Qingkai, S.; Jiaming, D.; Ying, W.; Zhao, L. Simulation Analysis of Renewable Energy Technology Diffusion Based on Complex Network Evolutionary Game. Power System Technology 2024, 48, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Nian, L.; Xinghuo, Y.; Cheng, W.; Jinjian, W. Energy Sharing Management for Microgrids with PV Prosumers:a Stackelberg Game Approach. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2017, 13, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Haiyang, W.; Ke, L.; Chenghui, Z.; Xin, M. Distributed Coordinative Optimal Operation of Community Integrated Energy System. Proceedings of the CSEE 2020, 40, 5435–5445. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z.; Ruifang, Z.; Jiancheng, Z.; Fangliang, S.; Delong, J. Low-carbon Economic Dispatch of Integrated Energy System In campus Based on Stackelberg Game and Hybrid Carbon Policy. Acta Energiae Solaris Sinica 2023, 44, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yingshu, L.; Xi, C.; Bin, L.; Jiebei, Z. State of Art of the Key Technologies of Multiple Microgrids System. Power System Technology 2020, 44, 3804–3820. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, W.; Xiong, X.; Yu, J.; Baodi, D.; Ying, Z. Overview on Multi-microgrid Technologies. Energy Storage Science and Technology 2019, 8, 621–628. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, M.; Hong, L. Economic Optimization Scheduling of Multi-microgrids system Based on Master-slave Game Under Multi-agent Technology. Acta Energiae Solaris Sinica 2024, 45, 574–582. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Difan, W.; Yuwei, L.; Haitao, L.; Nan, W.; Xichao, Z. Optimal Dispatch of Multi-microgrids Integrated Energy System Based on Integrated Demand Response and Stackelberg Game. Proceedings of the CSEE 2021, 41, 1307–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Z.; Xiaoqing, H.; Tingjun, L.; Bin, W.; Yizhulin, L. Master-slave Game Optimal Scheduling Strategy for Multi-agent Integrated Energy System Based on Demand Response and Power Interaction. Power System Technology 2022, 46, 3333–3346. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, R.; Guoli, L.; Cungang, H.; Qunjing, W.; Bin, X.; Jin, Z. Master-slave Game Optimization Method for Microgrid Group Considering Electricity Price Mechanism. Chinese Journal of Electrical Engineering 2020, 40, 2535–2546. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).