1. Introduction

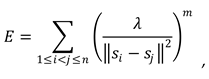

A wireless sensor network (WSN) is a group of devices that communicate wirelessly while being disseminated over an area of interest. Typically, it contains a number of sensor nodes along with at least one sink node usually referred as base station. The sensor nodes are micro electromechanical systems able to sense ambient conditions, collect and process the relative information and transmit the corresponding data to other nodes or/and the base station. The base station is a device which, thanks to its enhanced energy, computational, and communication resources, is able to process received from the network nodes, perform supervisory control of the WSN, and communicate with the end user and/or other networks [

1,

2]. The architecture of a typical WSN is illustrated in

Figure 1.

A WSN, taking advantage of the combined abilities of the nodes and the base station(s) that contains, is capable of both monitoring the ambient conditions at areas of interest of almost any kind and transmit related information to destinations no matter how much distant they are. For this reason, WSNs have been the basis of the Internet of Things (IoT) and support several sectors of human activities such as industry, flora and fauna, environment, healthcare, military and urban [

3]. Consequently, the already wide list of WSNs’ applications keeps on continuously growing [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

On the other hand, WSNs suffer due to not only inborn problems of wireless communications, but also severe restrictions of the sensor nodes regarding their resources for energy, storage and processing, not to mention various other application-related difficulties. Hence, plentiful scientific challenges and issues that need to be addressed are generated [

15]. This is why, the development of optimization and multiobjective optimization algorithms is necessitated [

16]. These algorithms aim to enhance the operation of WSNs regarding correspondingly individual and several performance metrics subject to a set of constraints such as coverage and connectivity optimization [

17,

18,

19], energy sustainability [

20], congestion avoidance [

21], quality of service attainment [

22], security provision [

23], data aggregation [

24], fault tolerance [

25], and node localization [

26].

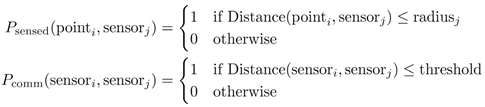

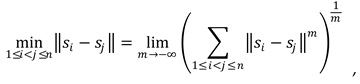

This research article focuses on coverage and connectivity optimization. Actually, the coverage optimization problem can be identified as the problem of locating a certain quantity of sensor nodes, which have a given sensing range, in the finest arrangement pursuing the maximization of the area covered by them and consequently minimize the coverage holes. Specifically in WSNs, three kinds of coverage may be recognized, which namely are area (or regional) coverage, target (or point) coverage, and barrier (or path) coverage. Area coverage refers to the monitoring of an area of interest in a pattern that guarantees that within this area all points are all the time observed. Target coverage denotes the unceasing monitoring of specific points of interest. Barrier coverage refers to the ability to always detect the movement across a barrier of sensor nodes [

27]. Actually, the mostly investigated coverage optimization problem in WSNs is that of area coverage. It can be stated either as 1-coverage or as k-coverage (where k is an integer greater than 1), depending on the minimum number of sensor nodes that always must monitor the specific area of interest simultaneously.

Apparently, area coverage maximization is pursued in every WSN containing a definite number of sensor nodes. Nevertheless, the area coverage problem in WSNs is recognized as a non-trivial research problem, because there are several issues that influence area coverage [

28]. For instance, the distribution of sensor nodes within the area of interest can be either arbitrary or deterministic. Similarly, the sensing area may be either probabilistic or deterministic. Also, the sensitivity of the sensor nodes may be either probabilistic or Boolean. Likewise, the communication range of the network nodes may be either variable or invariable. Moreover, the coverage pattern taken on may be either distributed or centralized. Furthermore, sensor nodes in a network may be either static or mobile. At the same time, the optimal distribution of sensor nodes in a network that maximizes coverage may cause connectivity losses to the sensor nodes of this network.

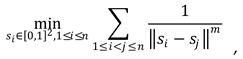

The goal of this research article is to find, under constraints, the optimal spatial deployment of a predetermined set of sensor nodes of varying sensing and communication capabilities as to maximize the sensed coverage of a specified area. One constrain might be that of the

k-coverage of the specific area points, meaning that for the deployment to be valid it is required that there are at least

k sensor nodes covering each one of the designated target points. The other constrain might be that of m-connectivity which indicates that all pairs of sensor nodes have at least m independent communication paths among them. Multiple connectivity amongst nodes is very desirable because it improves the resilience of the WSN in case of multiple sensor node failures. Unfortunately, maximal connectivity affects negatively the possible area coverage ratio as it requires denser deployments of sensor nodes. Usually, a tradeoff must be made that depends on the specific WSN application requirements. In this research work solely the

1-connectivity case is studied, i.e. the maximization of the covered area is pursued while ensuring that there exists at least one connecting communication path for every pair of sensor nodes [

29,

30].

In this context, the rest of this article is organized as follows. In

Section 2, the theoretical background of this research work is established. In

Section 3, the algorithm developed is described. The simulation procedure developed and the corresponding results produced for the algorithm evaluation are presented in

Section 4. Finally, in

Section 5, concluding remarks are drawn and future research work is proposed.

4. Simulation Tests and Performance Evaluation

Performance evaluation of the proposed algorithm was conducted via simulations in the MathWorks MATLAB environment and through comparative analysis with seven test cases outlined in [

37,

38].

Because the PSO methodology is a probabilistic (stochastic) method, in each case study the simulation test was conducted 30 times. The mean value and the standard deviation of area coverage percentage were calculated and are presented in the corresponding tables. Additionally, the highest area coverage achieved in each case is included as well as the ideal coverage which is the combined coverage that all the sensor nodes can provide in an unbounded environment.

In each of the case studies analyzed, a comparative assessment of the investigated PSO algorithms was performed using t-test methodology. This statistical technique allows for the evaluation of hypotheses related to a population by determining the p-value, which quantifies the degree of agreement between the data and the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis, in this scenario, assumes that there is no difference in the mean results produced by the two competing algorithms. The statistical tests compared the proposed algorithm against the PSO algorithms and not the Genetic Algorithms.

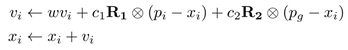

The PSO parameters used have fixed values during the whole simulation. Their values were calculated through meta-optimization around an initial parameter vector on the first test case and then manually rounded off and tuned around these calculated values for each case [

53]. The optimization method used was a direct search method based on a pattern search strategy which is an algorithm designed to solve nonlinear optimization problems without requiring gradient information [

54,

55]. The whole test case was entered as a function to the pattern search optimizer with the particle swarm parameters as the optimization variables. The particle swarm parameters used in the pattern search optimizer where the value of the inertia weight, the values of the two acceleration coefficients, the two parameter values of the objective function (see 3.2) and the values of the velocity bounds. All other parameters (particle number, maximum iterations, optimization termination tolerance) were chosen as close as possible to the respective values used in [

38] in order to better compare the performance of the algorithms.

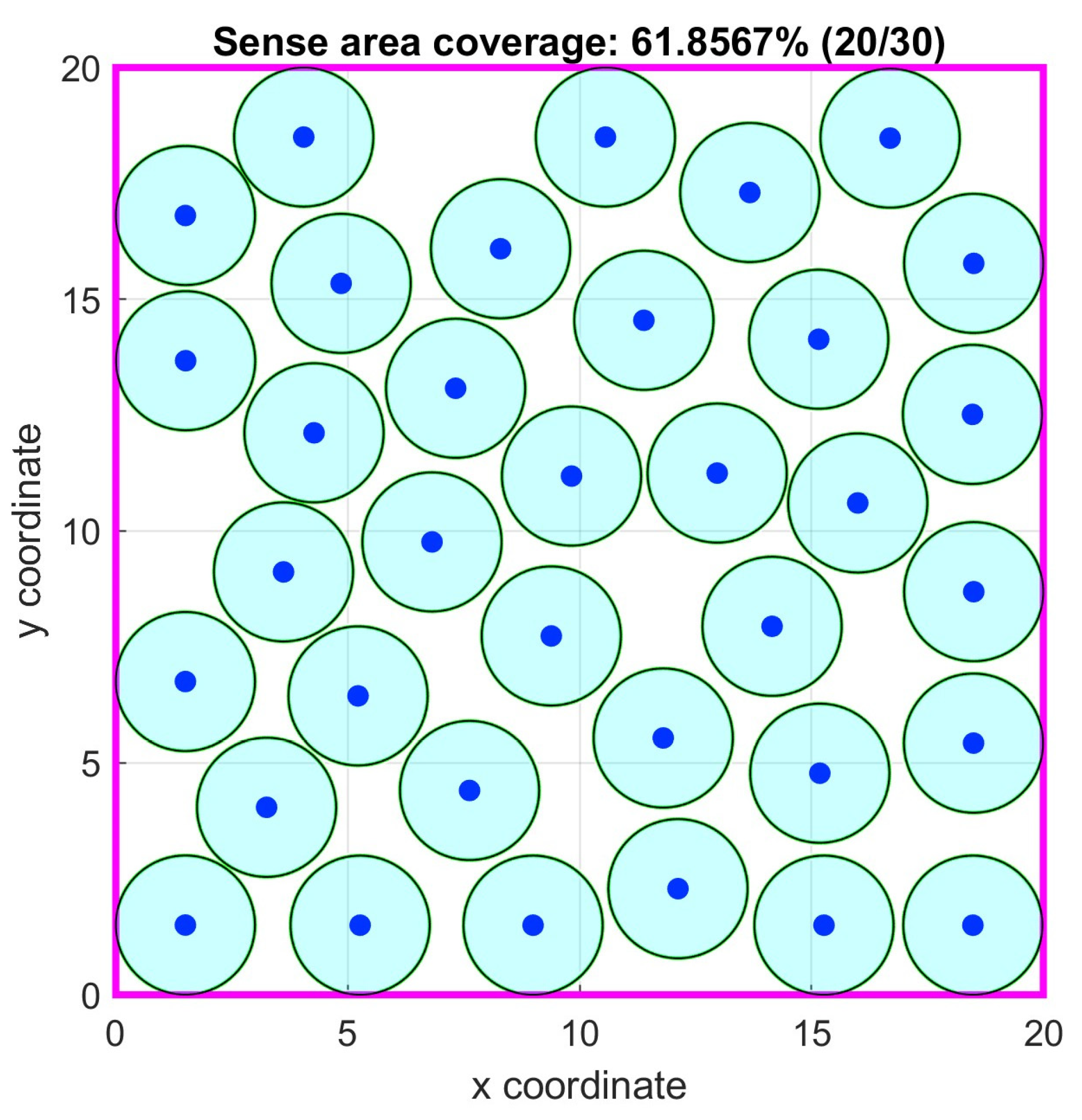

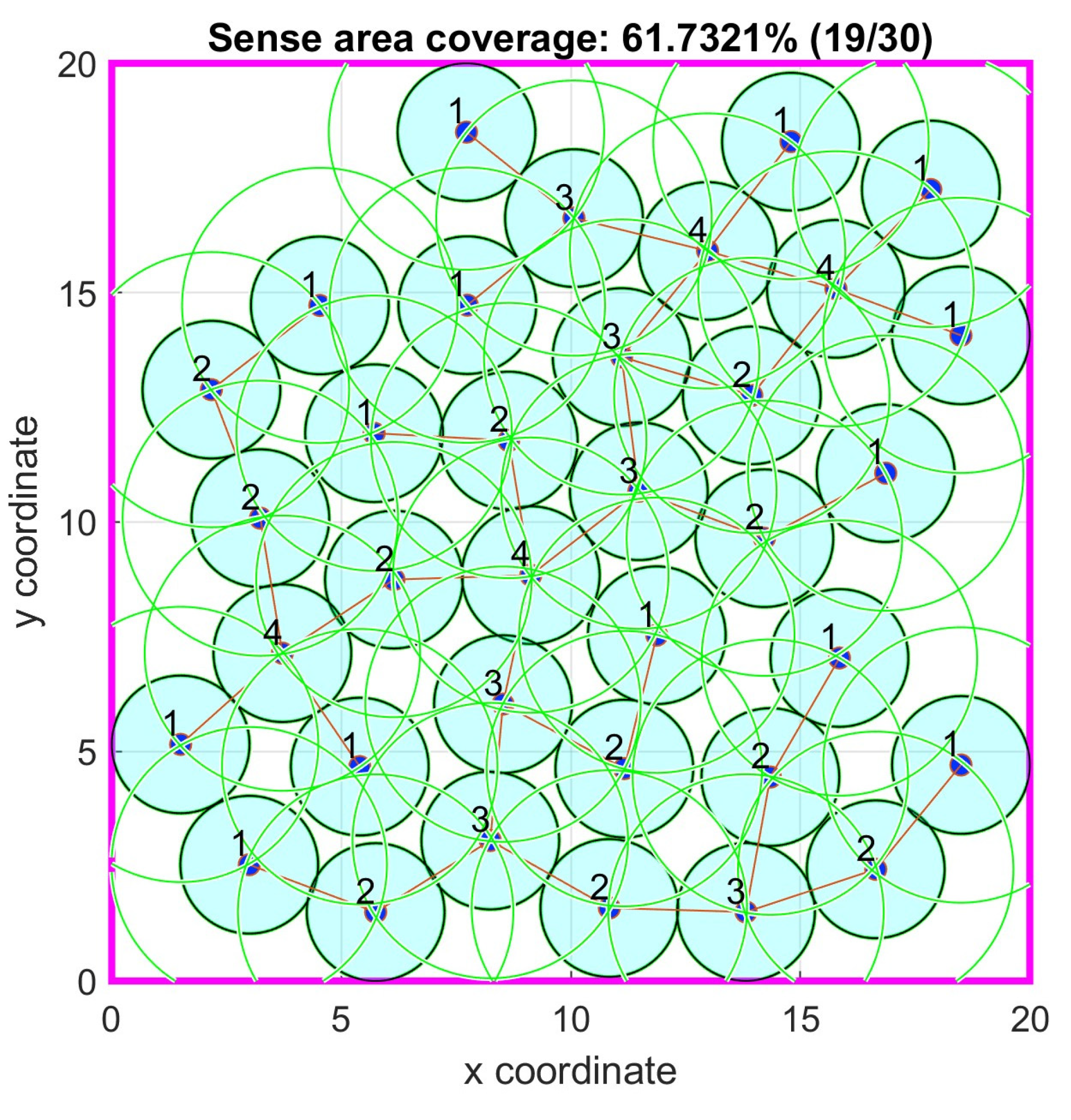

In all the case studies examined, the simulation results and the optimal node placement are depicted in the accompanying tables and figures. Specifically, in the figures depicting the optimal node locations with 1-connectivity, the cyan disks show the sense area of each node, the green circles the communication range of each node, the red lines show the established communication connections between the nodes and the numbers above the sensor node positions show with how many other nodes this sensor node is connected.

4.1. Case Study 1

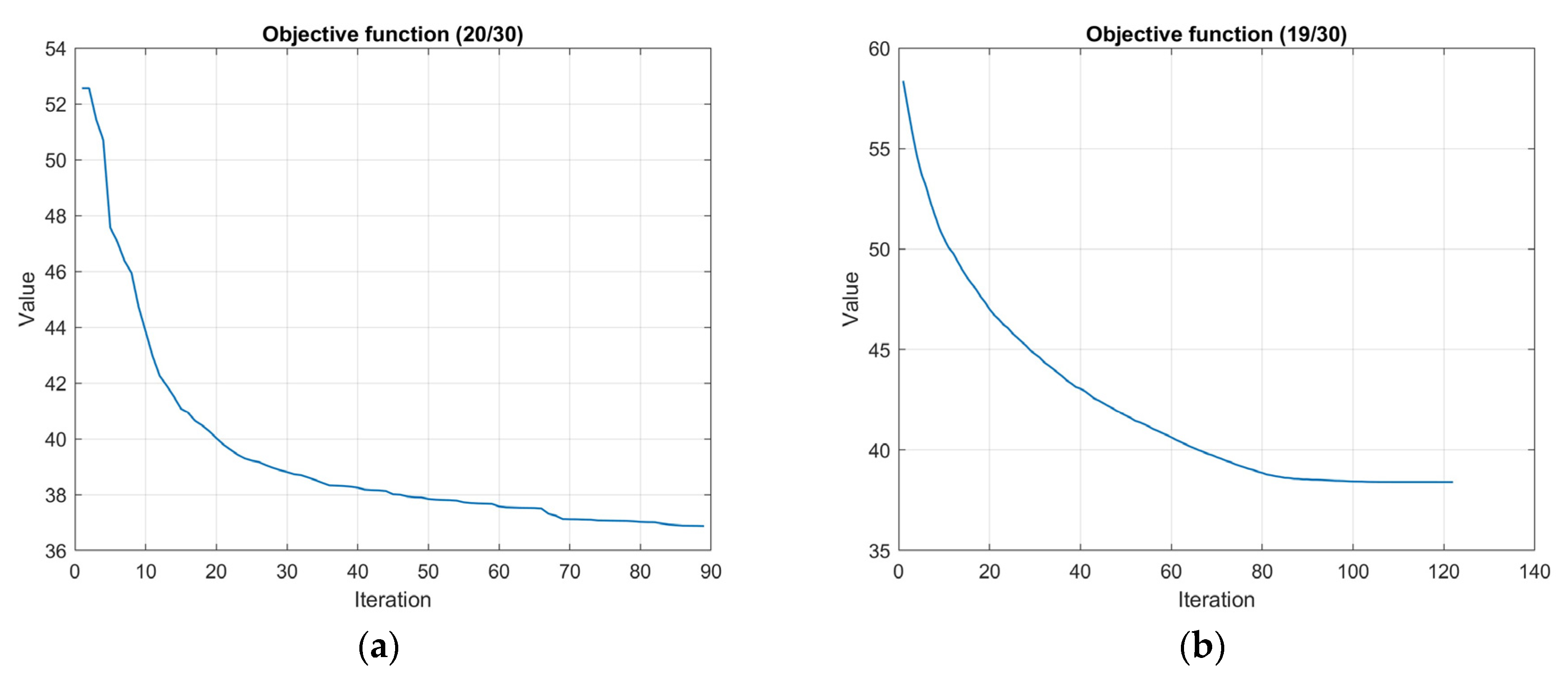

In this case study, the primary objective was to maximize the coverage of a two-dimensional square area measuring 20 × 20 units. A total of 35 sensor nodes were deployed, each equipped with a sensing range of 1.5 units and a communication range of 3.0 units. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm was configured with a particles size of 200 in the scenario with no connectivity required and 600 particles in the scenario requiring the 1-connectivity constrain.

The PSO parameters in the no connectivity requirement case were: =0.2, =1.5, =1.5, =0.7, =10, =0.05, =130, =20, =1%, =100%, while in the 1-connectivity requirement were: =0.2, =1.5, =1.5, =0.7, =10, =0.005, =130, =40, =1%, =100%.

In

Table 1, the results of the corresponding simulation tests are shown. Both algorithms with and without 1-connectivity requirements had better area coverage percentage mean values and standard deviations than the Genetic Algorithm (GA) based and PSO based ones in [

38] and were close to the ideal coverage. The p-value in the PSO with no connectivity requirement was negligible signifying that the proposed algorithm is better. In

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, the optimal node locations with and without 1-connectivity requirements are correspondingly shown. In

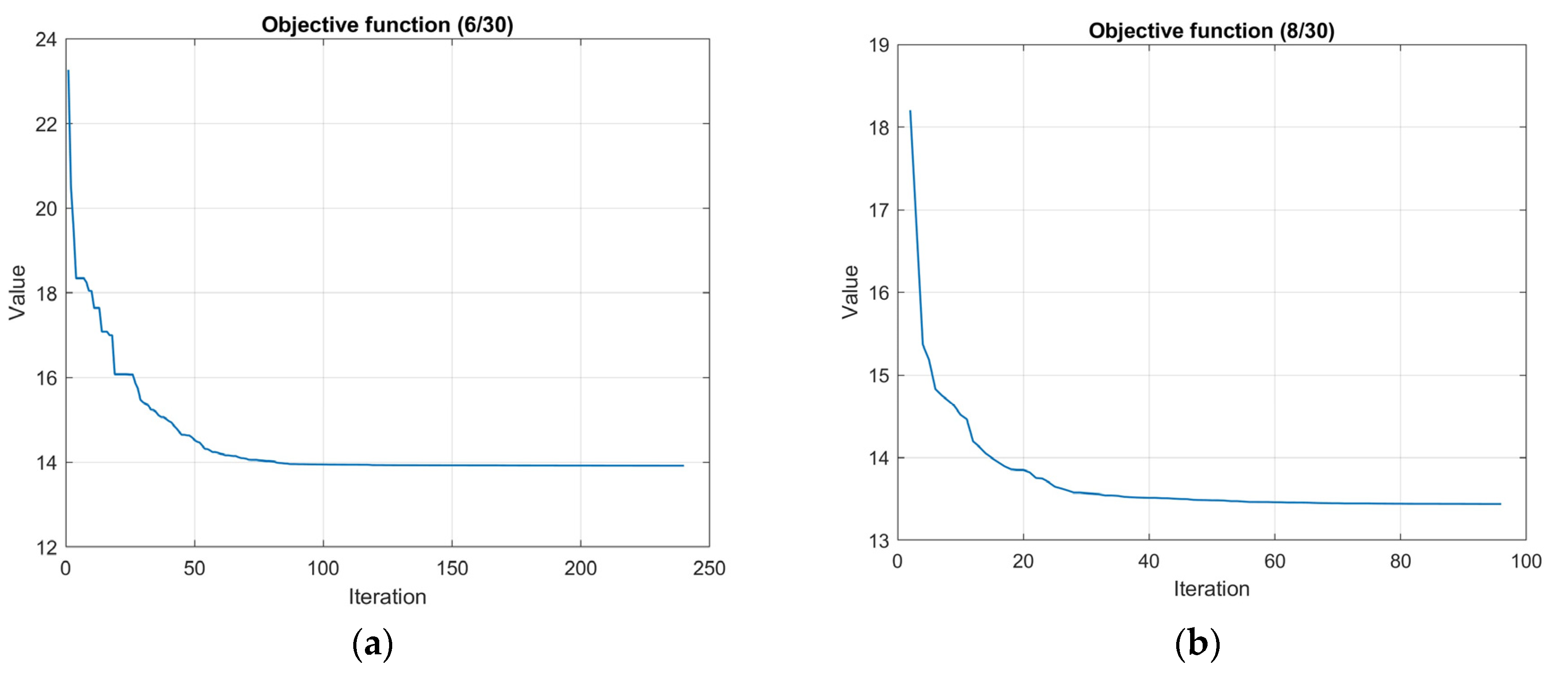

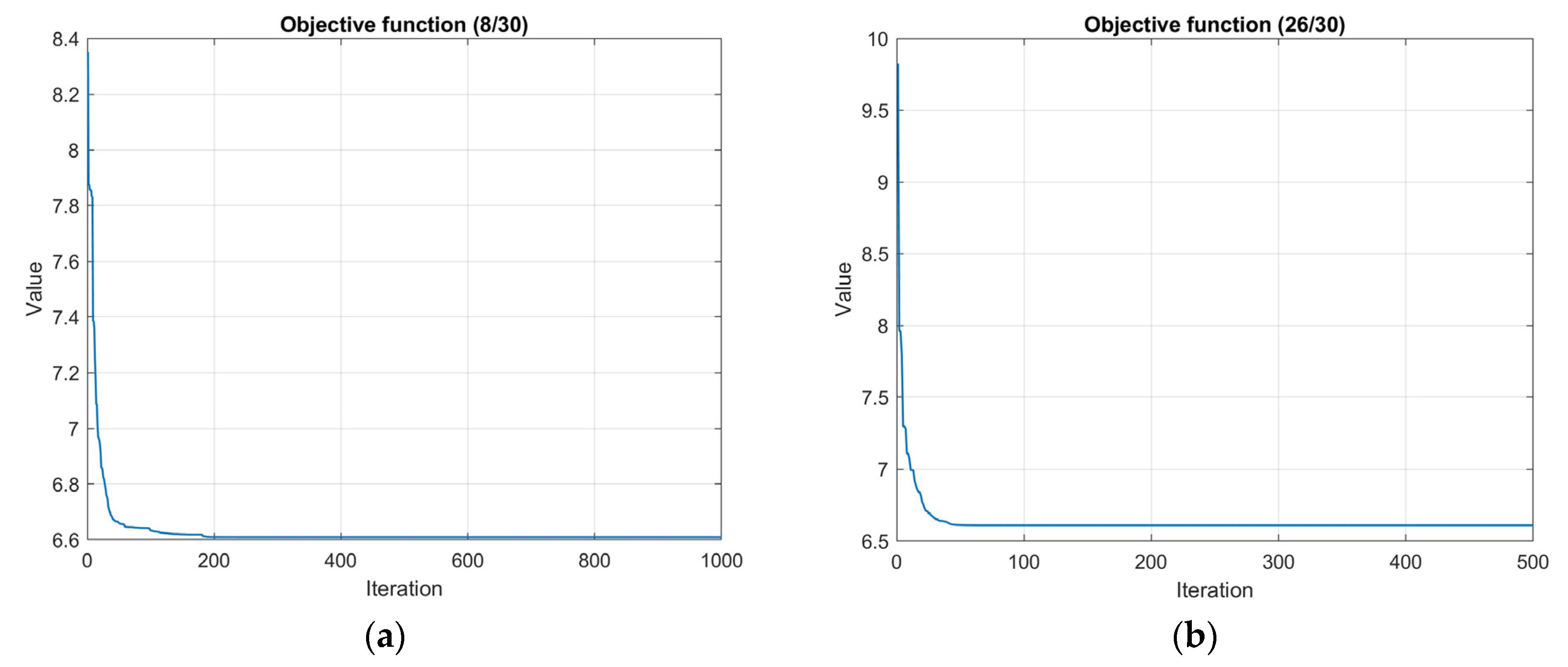

Figure 10 the objective function value iterations for both requirements are illustrated.

4.2. Case Study 2

In this case study, the primary objective was to maximize the coverage of a two-dimensional square area measuring 20 × 20 units. A total of 32 sensor nodes were deployed with varying sense ranges. Five sensor nodes had a sensing range of 0.8 units and of a communication range 2.8 units. Twenty sensor nodes had a sensing range of 1.5 units and a communication range of3.5 units. Seven sensor nodes had a sensing range of 2 units and a communication range of4 units. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm was configured with a particles size of 200 in the scenario with no connectivity required and 600 particles in the scenario requiring the 1-connectivity constrain.

The PSO parameters in the no connectivity requirement case were: =0.5, =1.5, =1.5, =0.7, =10, =0.01, =130, =20, =1%, =100%, while in the 1-connectivity requirement were: =0.2, =1.5, =1.5, =0.7, =10, =0.075, =130, =40, =1%, =100%.

In

Table 2, the results of the corresponding simulation tests are shown. The algorithm without the 1-connectivity requirement had better area coverage percentage mean values and standard deviations than the PSO based one in [

38] and was close to the ideal coverage. The p-value in the PSO with no connectivity requirement was negligible signifying that the proposed algorithm is better. In

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, the optimal node locations with and without 1-connectivity requirements are correspondingly shown. In

Figure 13 the objective function value iterations for both requirements are illustrated.

4.3. Case Study 3

In this case study, the primary objective was to maximize the coverage of a two-dimensional square area measuring 20 × 20 units. A total of 45 sensor nodes were deployed, each equipped with a sensing range of 1.5 units and a communication range of 3.0 units. Additionally, it was required to have a 3-coverage constrain for 6 area points at positions (5, 5), (10, 5), (15, 5), (5, 15), (10, 15) and (15, 15).

The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm was configured with a particles size of 600 in the scenario with no connectivity required and 1200 particles in the scenario requiring the 1-connectivity constrain.

The PSO parameters in the no connectivity requirement case were: =0.2, =1.5, =1.5, =0.7, =10, =1.0, =130, =20, =1%, =100%, while in the 1-connectivity requirement were: =0.2, =1.5, =1.5, =0.7, =10, =0.2, =130, =40, =1%, =100%.

In

Table 3, the results of the corresponding simulation tests are shown. Both algorithms with and without 1-connectivity requirements had better area coverage percentage mean values than the PSO based one in [

38] and the 3-coverage constrain was satisfied on all required points. The p-value in the PSO with no connectivity requirement was negligible signifying that the proposed algorithm is better. In

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, the optimal node locations with and without 1-connectivity requirements are correspondingly shown. In

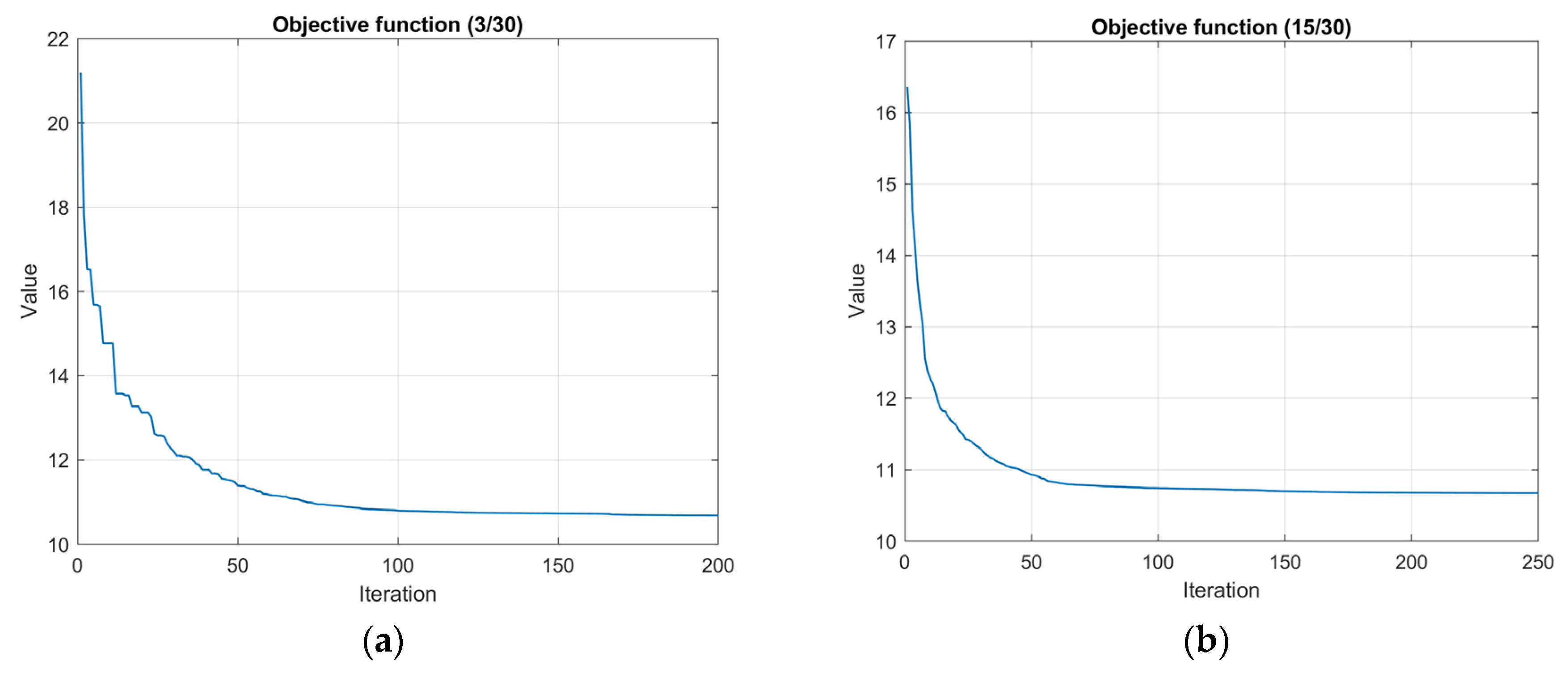

Figure 16 the objective function value iterations for both requirements are illustrated.

4.4. Case Study 4

In this case study, the primary objective was to maximize the coverage of a two-dimensional square area measuring 20 × 20 units. A total of 45 sensor nodes were deployed this time with varying sense ranges. Eighteen sensor nodes had a 1.0 unit sensing range and a communication range of 3.0 units. Twenty sensor nodes had a sensing range of 1.5 units and a communication range of 3.5 units. Seven sensor nodes had a sensing range of 2 units and a communication range of 4 units. Also, it was required to have a 3-coverage constrain for 6 area points at positions (5, 5), (10, 5), (15, 5), (5, 15), (10, 15) and (15, 15).

The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm was configured with a particles size of 600 in the scenario with no connectivity required and 1200 particles in the scenario requiring the 1-connectivity constrain.

The PSO parameters in the no connectivity requirement case were: =0.47, =1.59, =1.53, =0.24, =3.15, =1.75, =240, =100, =0.01%, =100%, while in the 1-connectivity requirement were: =0.5, =1.56, =1.56, =0.24, =3, =0.05, =240, =40, =1%, =100%.

In

Table 4, the results of the relevant simulation tests are shown. The PSO algorithm without the 1-connectivity requirement has slightly better area coverage percentage mean value than the GA based one in [

38] while the 3-coverage constrain is satisfied on all required points. The p-value between the proposed PSO with no connectivity requirement algorithm and the GA based one in [

38] is 0.066 signifying that there is some evidence that the proposed algorithm is better in this case. Although this test case is computationally expensive due to its complexity, further tuning of the PSO algorithm’s parameters is feasible and will further increase its performance. In

Figure 17 and

Figure 18, the optimal node locations with and without 1-connectivity requirements are respectively shown. In

Figure 19 the objective function value iterations for both requirements are shown.

4.5. Case Study 5

In this case study, the primary objective was to maximize the coverage of a two-dimensional square area measuring 50 × 50 units. A total of 40 sensor nodes were deployed, each equipped with a sensing range of 5.0 units and a communication range of 10.0 units. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm was configured with a particles size of 200 for both the scenarios with no connectivity required and the scenario requiring the 1-connectivity constrain.

The PSO parameters in the no connectivity requirement case were: =0.5, =1.5, =1.5, =0.2133, =3, =1.0, =200, =200, =1%, =100%, while in the 1-connectivity requirement were: =0.5, =1.5, =1.5, =0.2133, =3, =0.02, =250, =250, =1%, =100%. In this case there was no convergence limit and the border bound percentage was set in such a way as to allow the sensor nodes to move closer to the area boundary and leave no unmonitored parts at the border as the combined sense area of the sensor nodes exceeds the total target area.

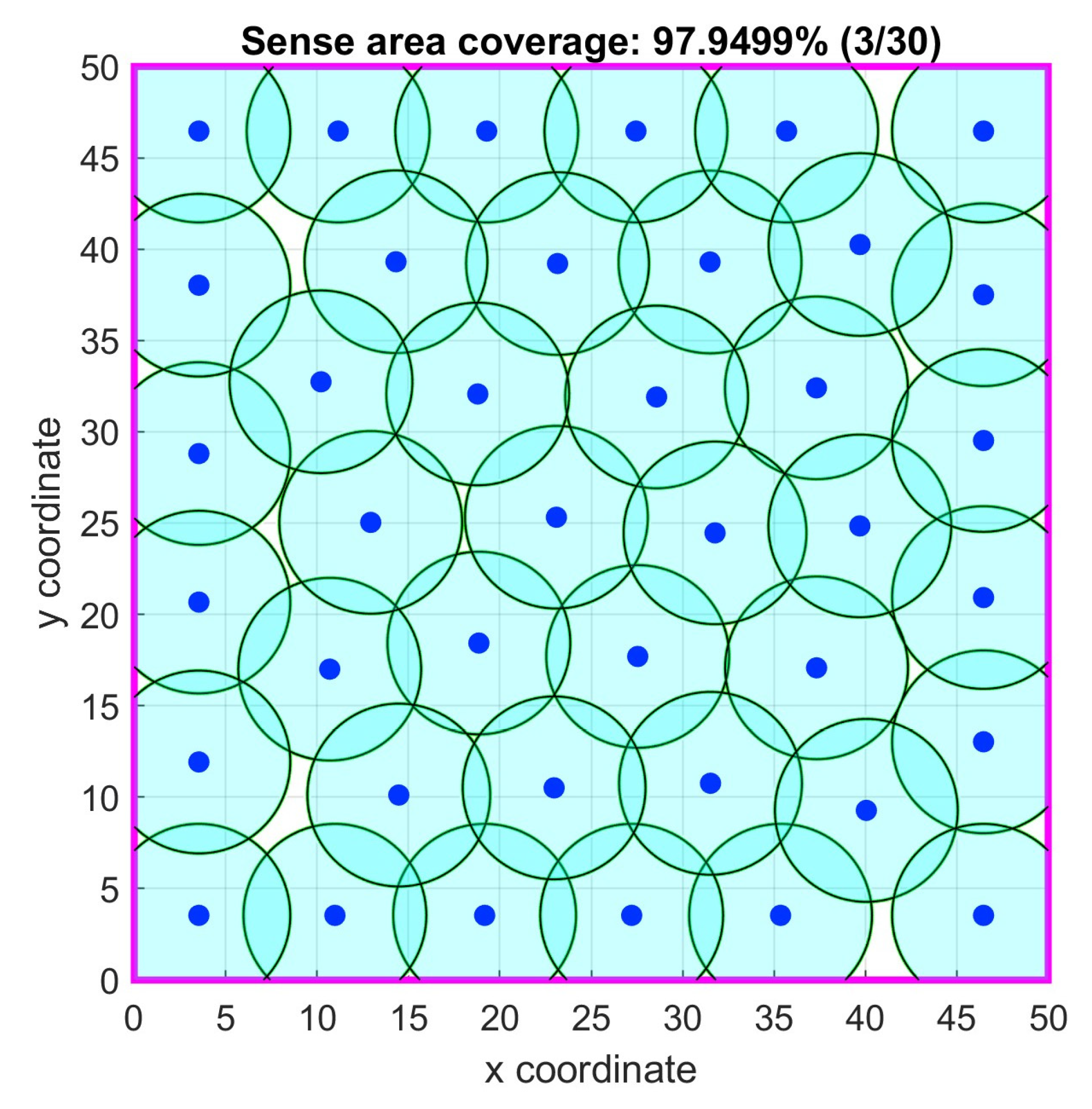

In

Table 5, the results of the corresponding simulation tests are shown. Both algorithms with and without 1-connectivity requirements had better area coverage percentage mean values and standard deviations than the Genetic Algorithm (GA) based and PSO based ones in [

38] and were quite close to the ideal coverage. The p-value in the PSO with no connectivity requirement was negligible signifying that the proposed algorithm is better. In

Figure 20 and

Figure 21, the optimal node locations with and without 1-connectivity requirements are correspondingly shown. In

Figure 22 the objective function value iterations for both requirements are illustrated.

4.6. Case Study 6

In this case study, the primary objective was to maximize the coverage of a two-dimensional square area measuring 50 × 50 units. A total of 20 sensor nodes were deployed, each equipped with a sensing range of 5.0 units and a communication range of 10.0 units. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm was configured with a particles size of 200 for both the scenario with no connectivity required and the scenario requiring the 1-connectivity constrain.

The PSO parameters in the no connectivity requirement case were: =0.5, =1.5, =1.5, =0.2133, =3, =0.16, =150, =150, =1%, =100%, while in the 1-connectivity requirement were: =0.5, =1.5, =1.5, =0.2133, =3, =0.016, =200, =200, =1%, =100%. In this case there was no convergence limit.

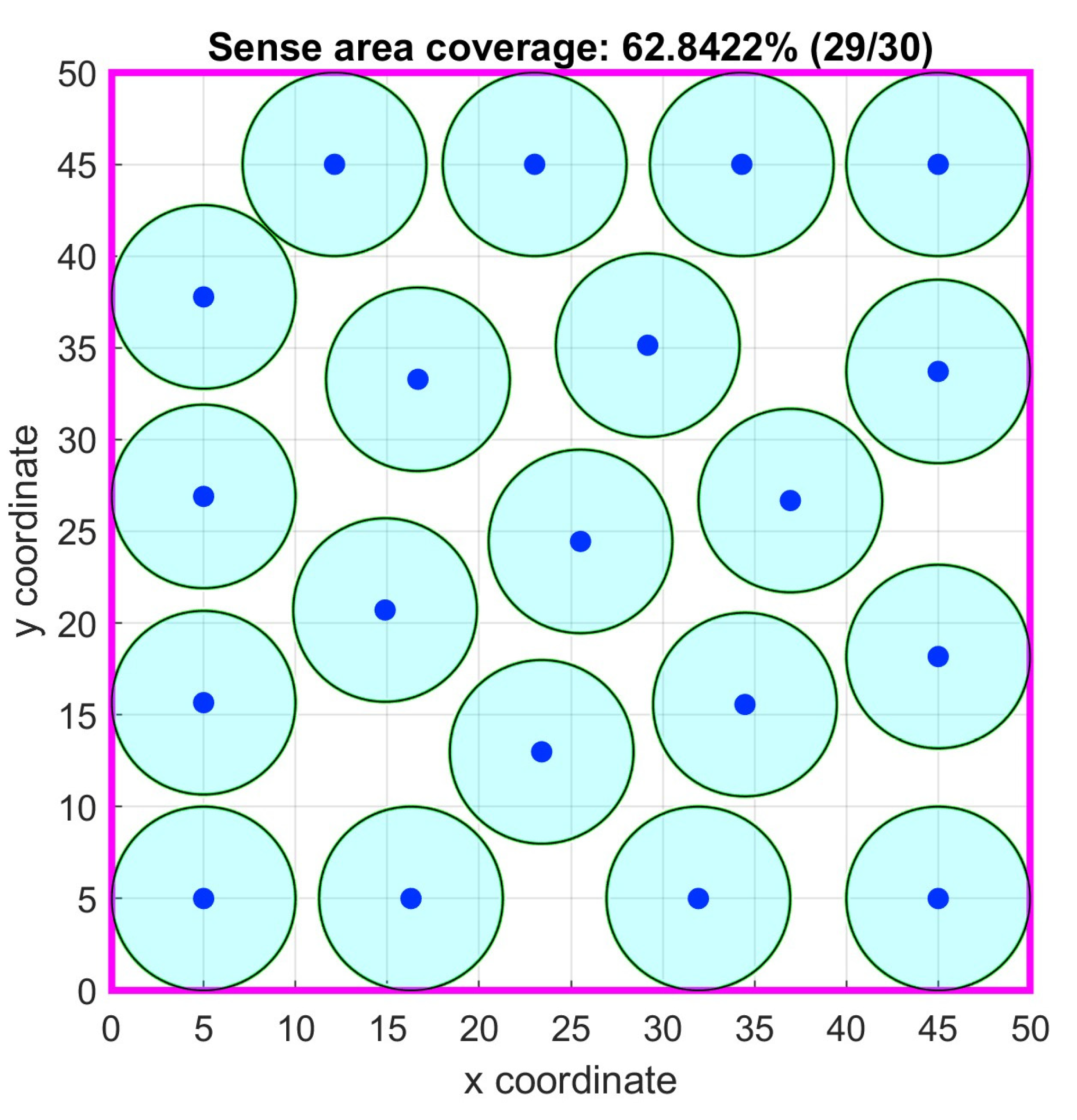

In

Table 6, the results of the corresponding simulation tests are shown. The algorithm without the 1-connectivity requirement had better area coverage percentage mean value and standard deviation than the Genetic Algorithm (GA) based and PSO based ones in [

38] and were close to the ideal coverage. The p-value in the PSO with no connectivity requirement was negligible signifying that the proposed algorithm is better. In

Figure 23 and

Figure 24, the optimal node locations with and without 1-connectivity requirements are correspondingly shown. In

Figure 25 the objective function value iterations for both requirements are illustrated.

4.7. Case Study 7

In this case study, the primary objective was to maximize the coverage of a two-dimensional square area measuring 30 × 30 units. A total of 20 sensor nodes were deployed, each equipped with a sensing range of 5.0 units and a communication range of 10.0 units. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm was configured with a particles size of 50 for both the scenario with no connectivity required and the scenario requiring the 1-connectivity constrain.

The PSO parameters in the no connectivity requirement case were: =0.4, =1.5, =1.575, =0.3, =1.5, =16.67, =1000, =1000, =1%, =100%, while in the 1-connectivity requirement were: =0.4, =1.5, =1.575, =0.3, =1.5, =16.67, =500, =500, =1%, =100%. In this case there was no convergence limit and the border bound percentage was set in such a way as to allow the sensor nodes to move closer to the area boundary and leave no unmonitored parts at the border as the combined sense area of the sensor nodes exceeds the total target area.

In

Table 7, the results of the corresponding simulation tests are shown. Both algorithms with and without 1-connectivity requirements had better area coverage percentage mean values and standard deviations than the Genetic Algorithm (GA) based and PSO based ones in [

38] and were quite close to the ideal coverage. The p-value in the PSO with no connectivity requirement was negligible signifying that the proposed algorithm is better. In

Figure 26 and

Figure 27, the optimal node locations with and without 1-connectivity requirements are correspondingly shown. In

Figure 28 the objective function value iterations for both requirements are illustrated.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, a novel Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) approach tackling the problem of the optimal placement of a predefined number of sensor nodes within a square target area, adhering to k-coverage and 1-connectivity constraints is proposed. Also, a new objective function derived from circle packing geometric problems is introduced. This function serves as an alternative to traditional area coverage minimization objectives and simplifies implementation. The objective function resembles the repulsion force-based methods but with a much cleaner definition and simpler implementation.

We tested our method against seven benchmark test cases presented in [

38]. Two of the test cases included 3-coverage constrain of 6 predefined points in the region and two test cases required different sensing and communication ranges of the sensor nodes. Each test case was executed 30 times and involved the computation of the mean and standard deviation of the area coverage percentage, thereby accounting for the stochastic nature of the PSO algorithm.

Our findings indicate that in six out of the seven test cases, our PSO method was better in terms of either or both the mean value and the standard deviation of the area coverage percentage. The statistical significance of this was confirmed using the t-test methodology. In one test case involving the 3-coverage of six points of interest, our methodology demonstrated better performance compared to the Genetic Algorithm-based approach used in [

38]. This test case is quite challenging and computationally intensive especially with the 1-connectivity constrain. It is anticipated that further tuning of the PSO parameters and/or change of the PSO implementation methodology—such as using a variable inertia weight

or adjusting other PSO parameters across algorithm iterations, or selecting a different static or dynamic population topology—could enhance its performance.

The presented methodology showed promising results and could be generalized and extended in various different aspects in the future like those presented in the following paragraphs.

Extension to arbitrary target areas, i.e. generalize and test our method on various geometric shapes beyond square regions, adapting the algorithm to handle irregular boundaries or even obstacles within the deployment area.

Generalization of sensor node sensing patterns, i.e. make changes to accommodate for diverse sensor node sensing patterns, not limited to circular ones. This could be achieved by incorporating directional parameters into the objective function thus making possible the modeling of anisotropic sensing fields which is common in practical WSN applications.

General communication radiation patterns, i.e. extending our method to handle realistic, non-circular communication range patterns. This could be achieved by employing Laplacian eigenvalue methodologies used extensively in robotics [

56,

57] instead of the direct search methods used in this work. This could also facilitate the incorporation of m-connectivity constraints thus improving network robustness and fault tolerance.

Application in other metaheuristics, i.e. to investigate the effectiveness of our proposed objective function within other metaheuristic optimization frameworks, except the PSO method.

Minimal Sensor Deployment, i.e. to adapt our method to not only maximize coverage but also to determine the minimal number of sensor nodes required for a given coverage and connectivity application. This could have significant implications in cost reduction and resource efficiency.

Energy consumption modeling, i.e. to try to integrate energy models into our optimization framework, as energy efficiency directly impacts network lifespan.

Robustness against failures, i.e. to assess the resilience of our deployment strategy under varying environmental conditions and node failures and incorporate dynamic adaptation mechanisms to enhance its performance.

Finally, the validation of our method through real-world deployments is crucial to assess the practical feasibility and performance of our approach in operational environments.

Figure 1.

Architecture of a typical WSN.

Figure 1.

Architecture of a typical WSN.

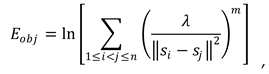

Figure 2.

General PSO algorithm outline.

Figure 2.

General PSO algorithm outline.

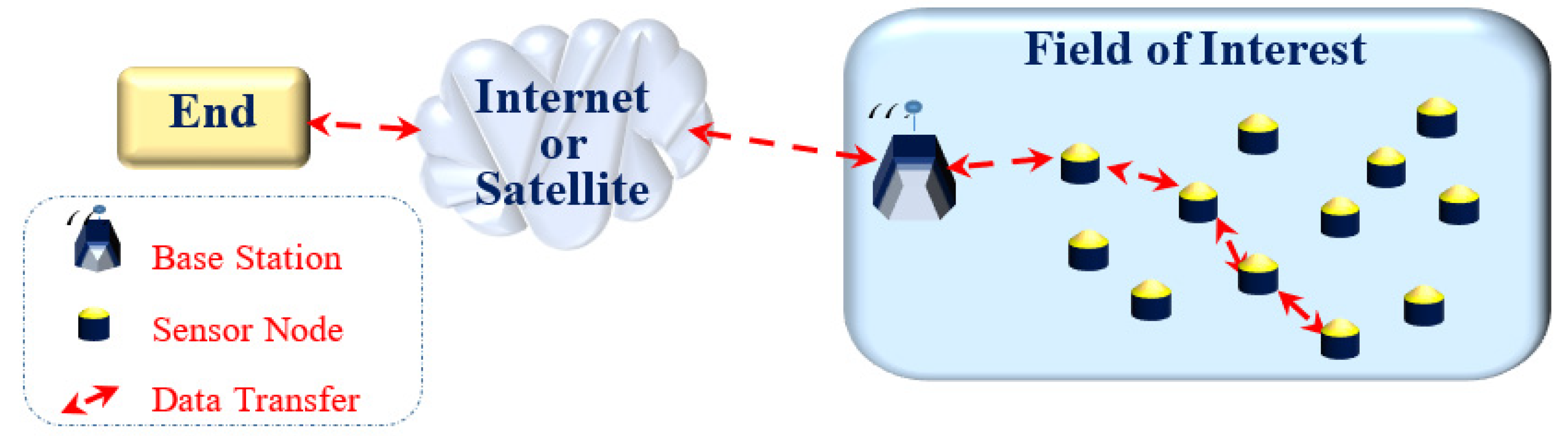

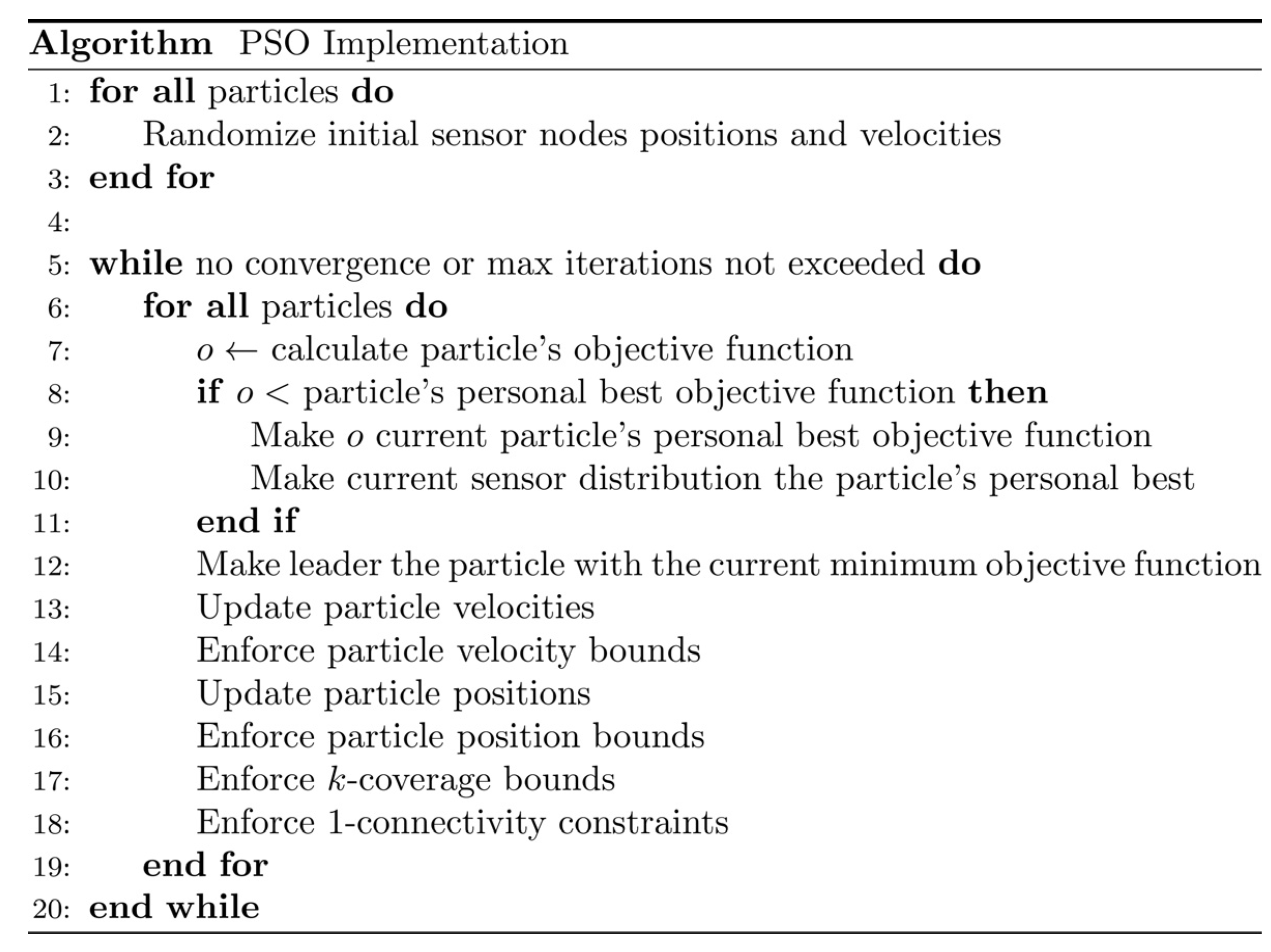

Figure 3.

PSO implementation algorithm.

Figure 3.

PSO implementation algorithm.

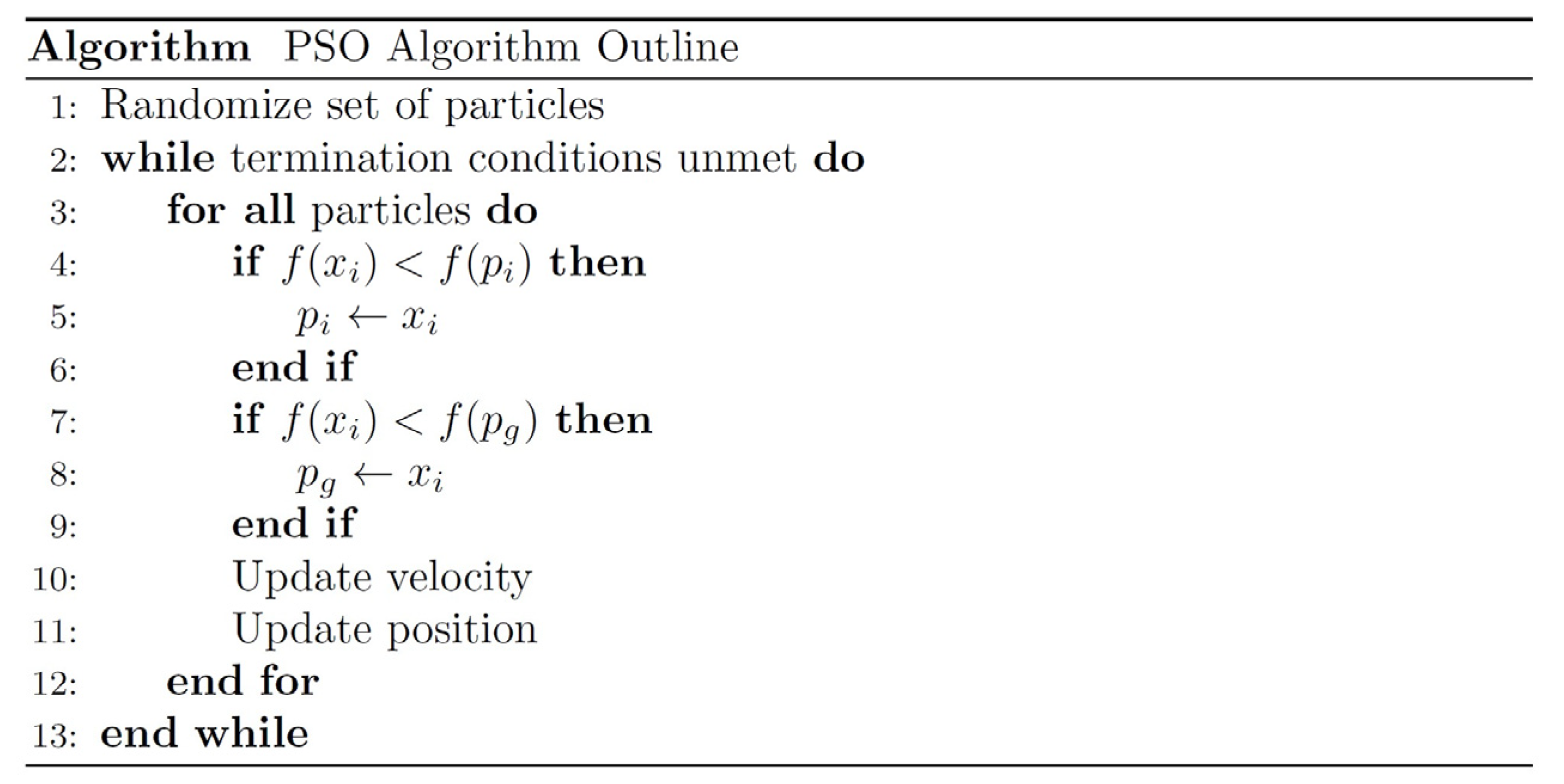

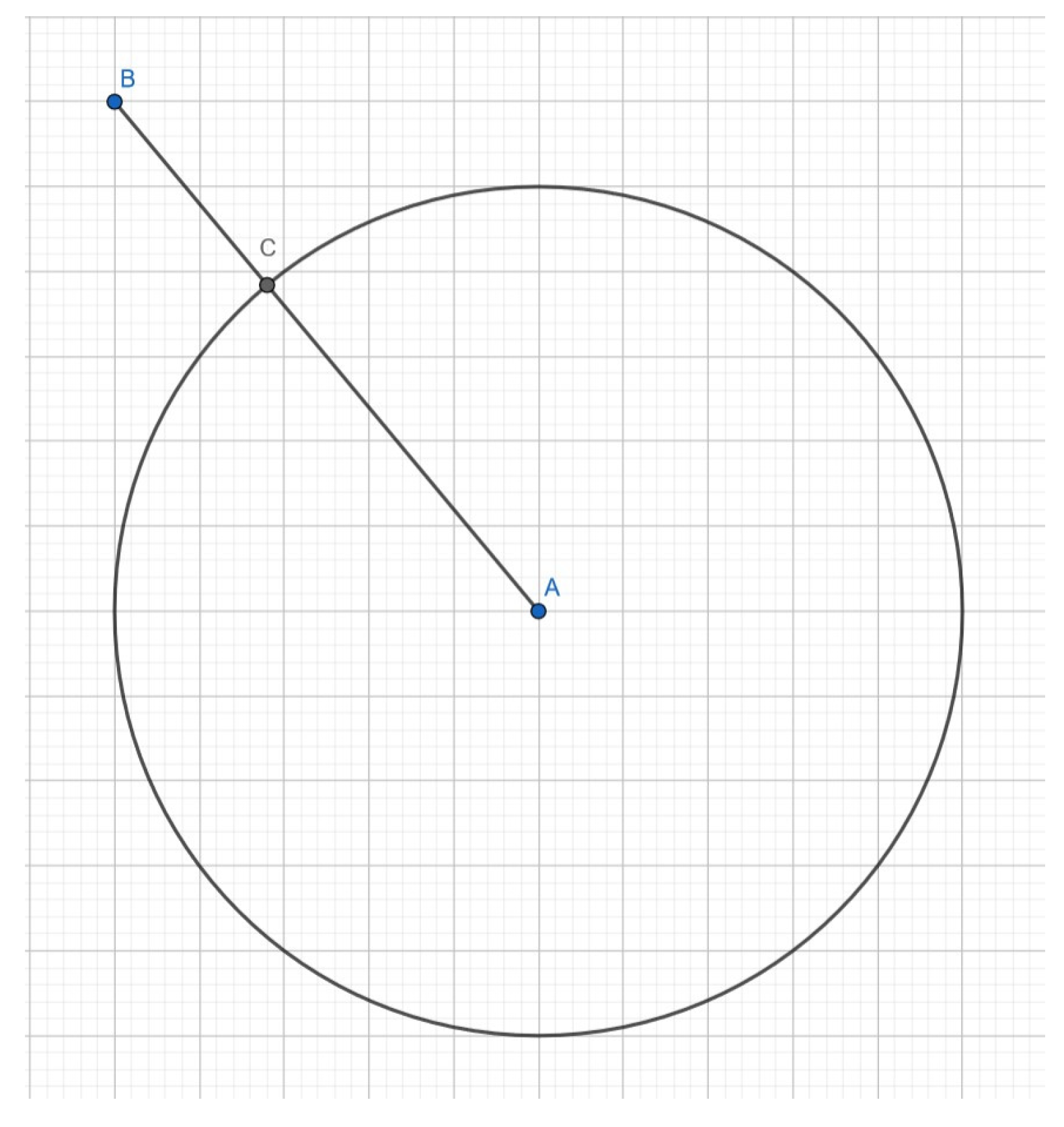

Figure 4.

k-Coverage sensor-point geometry.

Figure 4.

k-Coverage sensor-point geometry.

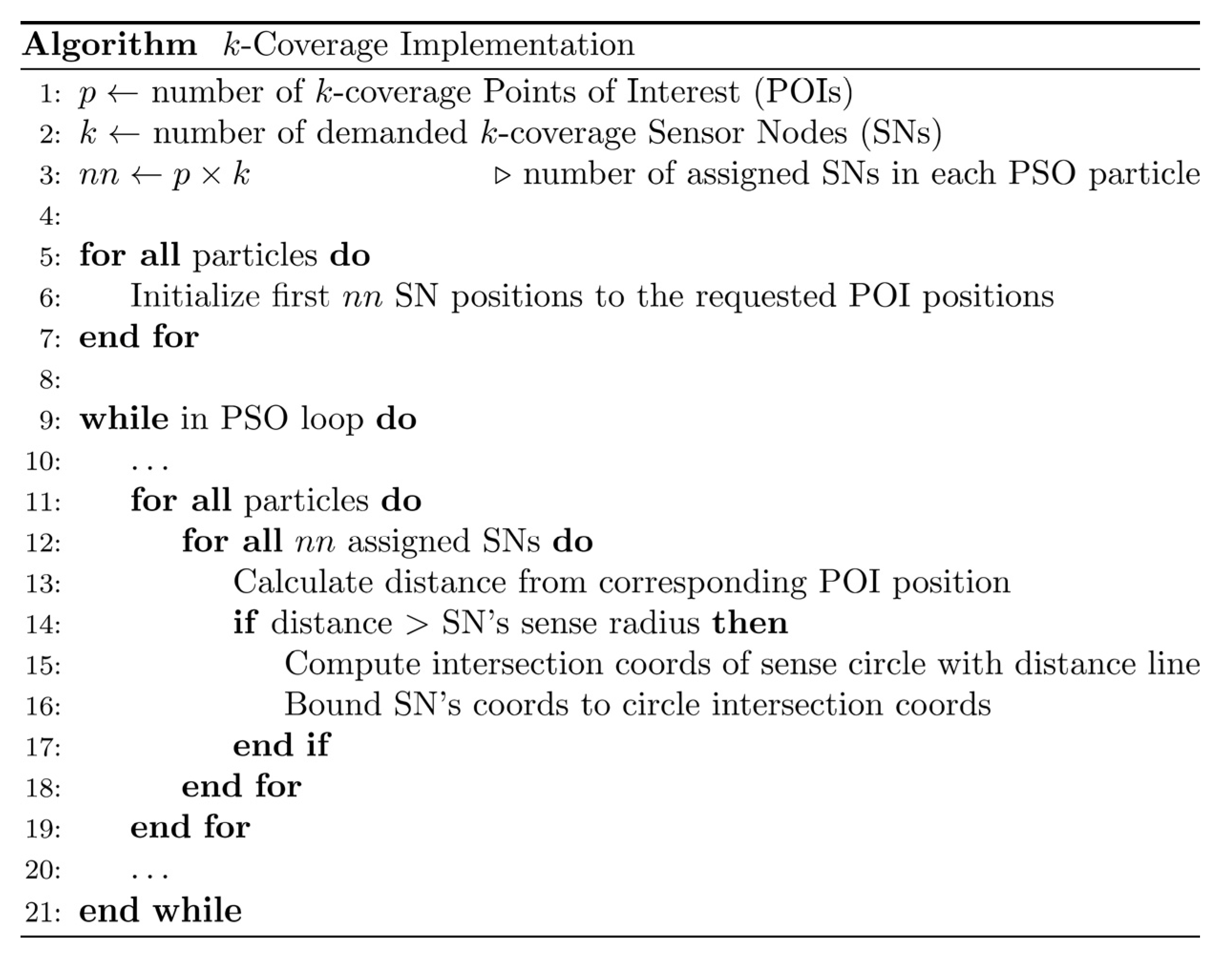

Figure 5.

k-Coverage implementation algorithm.

Figure 5.

k-Coverage implementation algorithm.

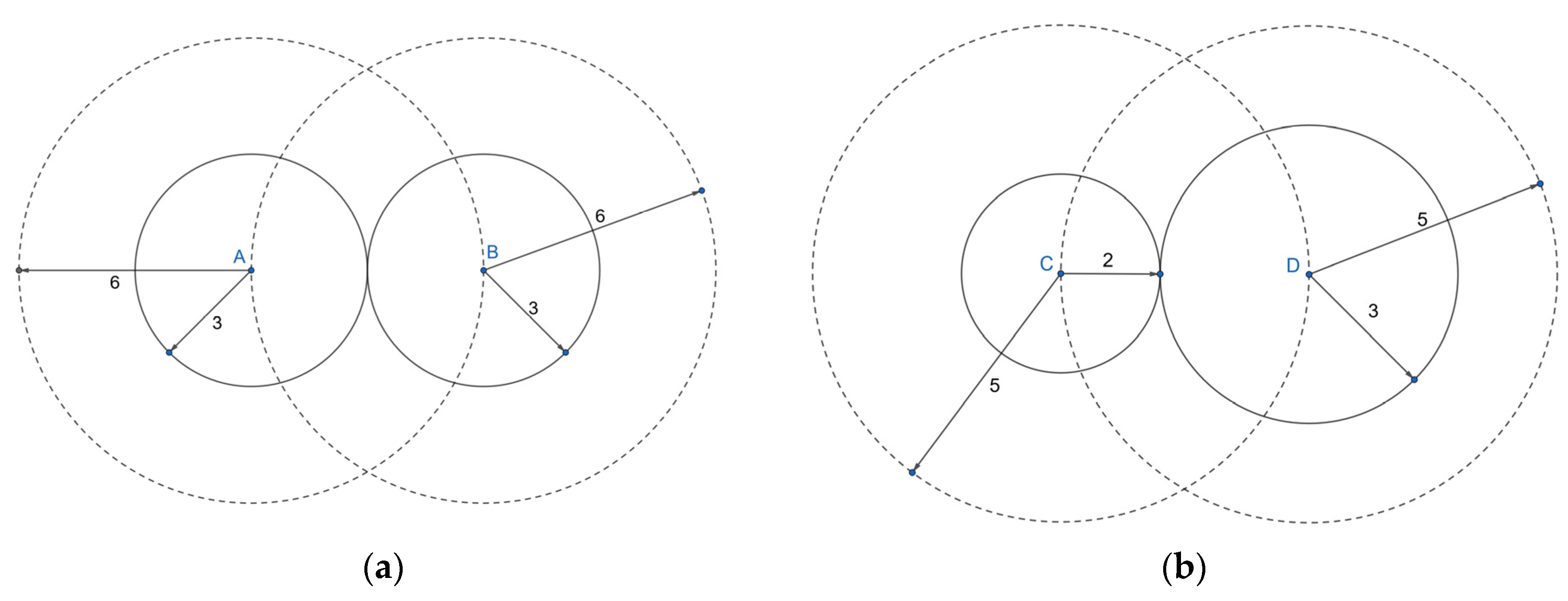

Figure 6.

Calculation example of two sensor nodes communication ranges (dashed lines) based on their sense ranges (solid lines) (a) both sense ranges = 3, communication ranges = 6; (b) sense ranges = 2 and 3, communication ranges = 5.

Figure 6.

Calculation example of two sensor nodes communication ranges (dashed lines) based on their sense ranges (solid lines) (a) both sense ranges = 3, communication ranges = 6; (b) sense ranges = 2 and 3, communication ranges = 5.

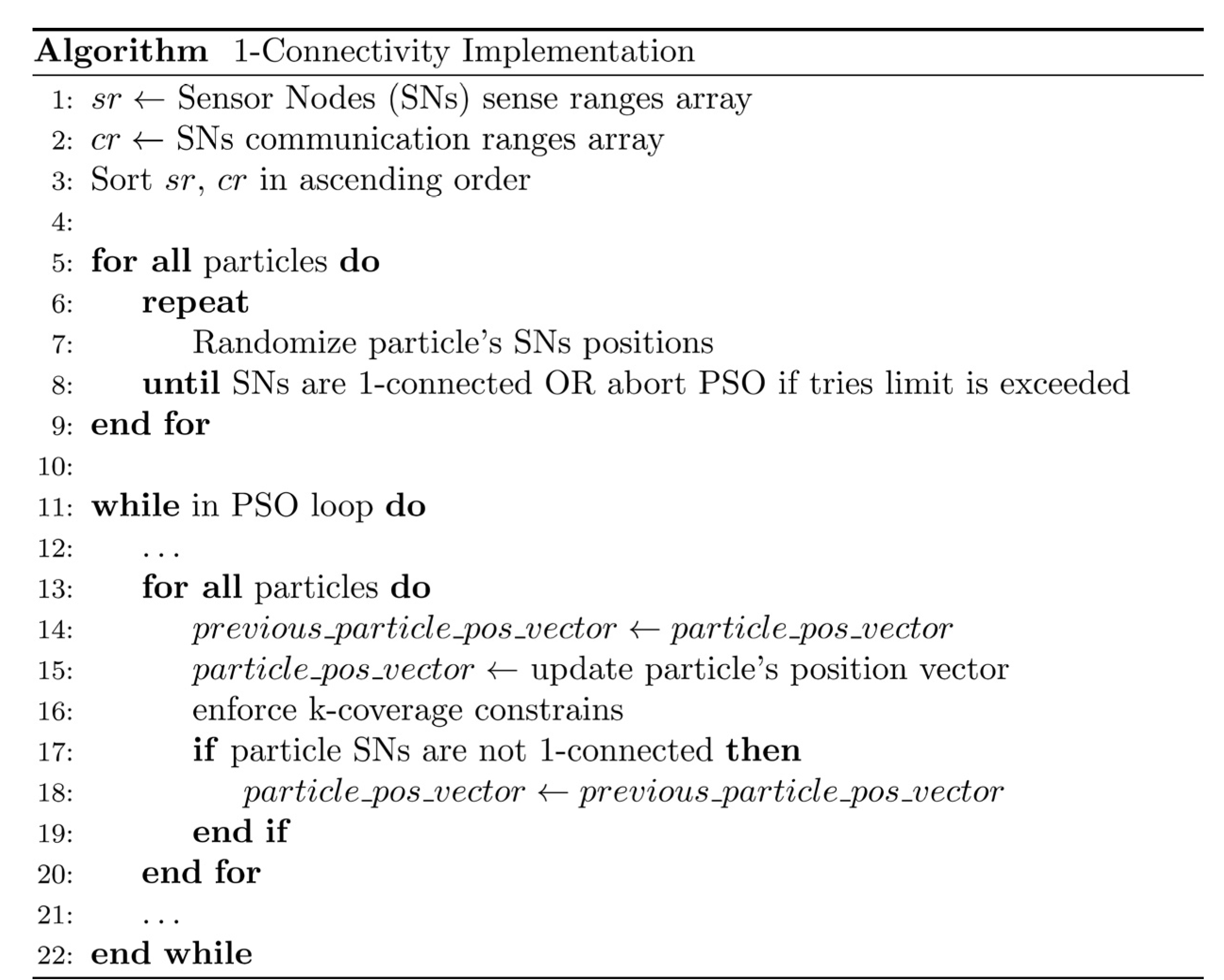

Figure 7.

1-Connectivity implementation algorithm.

Figure 7.

1-Connectivity implementation algorithm.

Figure 8.

Case study 1: Optimal node locations.

Figure 8.

Case study 1: Optimal node locations.

Figure 9.

Case study 1: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 9.

Case study 1: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 10.

Case study 1: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 10.

Case study 1: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 11.

Case study 2: Optimal node locations.

Figure 11.

Case study 2: Optimal node locations.

Figure 12.

Case study 2: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 12.

Case study 2: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 13.

Case study 2: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 13.

Case study 2: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 14.

Case study 3: Optimal node locations.

Figure 14.

Case study 3: Optimal node locations.

Figure 15.

Case study 3: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 15.

Case study 3: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 16.

Case study 3: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 16.

Case study 3: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 17.

Case study 4: Optimal node locations.

Figure 17.

Case study 4: Optimal node locations.

Figure 18.

Case study 4: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 18.

Case study 4: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 19.

Case study 4: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 19.

Case study 4: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 20.

Case study 5: Optimal node locations.

Figure 20.

Case study 5: Optimal node locations.

Figure 21.

Case study 5: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 21.

Case study 5: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 22.

Case study 5: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 22.

Case study 5: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 23.

Case study 6: Optimal node locations.

Figure 23.

Case study 6: Optimal node locations.

Figure 24.

Case study 6: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 24.

Case study 6: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 25.

Case study 6: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 25.

Case study 6: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 26.

Case study 7: Optimal node locations.

Figure 26.

Case study 7: Optimal node locations.

Figure 27.

Case study 7: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 27.

Case study 7: Optimal node locations with 1-connectivity.

Figure 28.

Case study 7: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Figure 28.

Case study 7: Objective function iterations (a) No connectivity; (b) 1-connectivity.

Table 1.

Case study 1: Simulation results.

Table 1.

Case study 1: Simulation results.

| Parameter |

GA[38] |

PSO[38] |

PSO No Conn |

PSO 1-Conn |

| Mean Value |

61.17 |

60.92 |

61.79 |

61.49 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.28 |

0.46 |

0.12 |

0.15 |

| Best Fitness |

61.56 |

61.49 |

61.86 |

61.73 |

| p-Value |

|

|

0.00 |

|

| Ideal Coverage |

61.86 |

Table 2.

Case study 2: Simulation results.

Table 2.

Case study 2: Simulation results.

| Parameter |

GA[38] |

PSO[38] |

PSO No Conn |

PSO 1-Conn |

| Mean Value |

59.37 |

58.83 |

59.44 |

57.77 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.18 |

0.38 |

0.27 |

0.62 |

| Best Fitness |

59.69 |

59.32 |

59.85 |

58.85 |

| p-Value |

|

|

0.00 |

|

| Ideal Coverage |

59.85 |

Table 3.

Case study 3: Simulation results.

Table 3.

Case study 3: Simulation results.

| Parameter |

GA[38] |

PSO[38] |

PSO No Conn |

PSO 1-Conn |

| Mean Value |

73.07 |

72.13 |

74.21 |

72.69 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.66 |

0.85 |

0.98 |

1.45 |

| Best Fitness |

74.28 |

73.77 |

75.76 |

75.05 |

| p-Value |

|

|

0.00 |

|

| Ideal Coverage |

79.52 |

Table 4.

Case study 4: Simulation results.

Table 4.

Case study 4: Simulation results.

| Parameter |

GA[38] |

PSO[38] |

PSO No Conn |

PSO 1-Conn |

| Mean Value |

67.39 |

69.89 |

67.69 |

65.72 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.45 |

1.15 |

0.97 |

1.64 |

| Best Fitness |

68.24 |

71.46 |

69.19 |

68.41 |

| p-Value |

|

|

0.066* |

|

| Ideal Coverage |

71.47 |

Table 5.

Case study 5: Simulation results.

Table 5.

Case study 5: Simulation results.

| Parameter |

GA[38] |

PSO[38] |

PSO No Conn |

PSO 1-Conn |

| Mean Value |

96.40 |

95.53 |

97.37 |

97.58 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.59 |

0.66 |

0.29 |

0.20 |

| Best Fitness |

- |

- |

97.95 |

98.02 |

| p-Value |

|

|

0.00 |

|

| Ideal Coverage |

100 |

Table 6.

Case study 6: Simulation results.

Table 6.

Case study 6: Simulation results.

| Parameter |

GA[38] |

PSO[38] |

PSO No Conn |

PSO 1-Conn |

| Mean Value |

62.50 |

62.38 |

62.83 |

61.95 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.23 |

0.18 |

0.006 |

0.30 |

| Best Fitness |

- |

- |

62.84 |

62.38 |

| p-Value |

|

|

0.00 |

|

| Ideal Coverage |

62.84 |

Table 7.

Case study 7: Simulation results.

Table 7.

Case study 7: Simulation results.

| Parameter |

GA[38] |

PSO[38] |

PSO No Conn |

PSO 1-Conn |

| Mean Value |

99.76 |

99.55 |

99.93 |

99.90 |

| Standard Deviation |

0.10 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

| Best Fitness |

- |

- |

99.96 |

99.96 |

| p-Value |

|

|

0.00 |

|

| Ideal Coverage |

100 |